Abstract

Objectives. We modeled triple trajectories of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood as predictors of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

Methods. We assessed urban African American and Puerto Rican participants (n = 816) in the Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, a psychosocial investigation, at 4 time waves (mean ages = 19, 24, 29, and 32 years). We used Mplus to obtain the 3 variable trajectories of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use from time 2 to time 5 and then conducted logistic regression analyses.

Results. A 5-trajectory group model, ranging from the use of all 3 substances (23%) to a nonuse group (9%), best fit the data. Membership in the trajectory group that used all 3 substances was associated with an increased likelihood of both ASPD (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 6.83; 95% CI = 1.14, 40.74; P < .05) and GAD (AOR = 4.35; 95% CI = 1.63, 11.63; P < .001) in adulthood, as compared with the nonuse group, with control for earlier proxies of these conditions.

Conclusions. Adults with comorbid tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use should be evaluated for use of other substances and for ASPD, GAD, and other psychiatric disorders. Treatment programs should address the use of all 3 substances to decrease the likelihood of comorbid psychopathology.

Tobacco use, alcohol use, and marijuana use often co-occur, such that some individuals who use 1 of these substances are at risk for use of the others.1–4 Schulenberg et al.,5 for instance, showed that membership in the chronic and abstainer marijuana use groups predicted the highest and lowest rates, respectively, of both binge drinking and tobacco use among emerging adults. In one of the few studies to assess concurrent trajectories of the use of 2 or more substances, Jackson et al.6 showed that separate patterns of tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana use from late adolescence to young adulthood were related to an increased likelihood of similar patterns of other substance use (e.g., chronic marijuana use was more frequent among chronic tobacco smokers).

The use of 1 or more substances, as well as substance use disorders (SUDs), have consistently been found to be comorbid with or predictive of psychopathology, including antisocial behaviors and disorders as well as anxiety.7–11 Relatively little research, however, has examined the comorbidity of SUDs and psychopathology across ethnic groups, and no study has focused on substance use as opposed to SUDs. Findings generally show that SUDs increase the likelihood of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), among African Americans.12,13 Similar associations have been found less consistently among Latino individuals. Smith et al.,14 for instance, showed that alcohol dependence, but not abuse, was related to GAD among Latino patients. Although a strong link has been established between substance use or SUDs and antisocial behaviors or disorders,15,16 we are unaware of any studies that assessed these associations among both African American and Latino persons.

Some investigations have specifically examined the relation between patterns of substance use, or patterns of comorbid substance use over time (i.e., trajectories), and externalizing or internalizing problems.17 Caldeira et al.,18 for instance, found that membership in the chronic heavy marijuana use trajectory group (from ages 18 to 24 years) was associated with greater use of alcohol and tobacco and predicted more anxiety during emerging adulthood than in any other trajectory group. In an analysis of separate trajectories of alcohol use and marijuana use from preadolescence to emerging adulthood, Flory et al.19 also found that membership in the trajectory group with the highest levels of both alcohol and marijuana use over time (early-onset users) was related to more symptoms of antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) among emerging adults than was membership in the nonusers group. Evidence also indicates that the concurrent use of 2 or more substances is associated with worse psychosocial outcomes than is the use of 1 substance alone.17,20–22 To date, however, no studies have examined triple trajectories of substance use (i.e., the comorbid use of 3 substances) or their consequences. Given the high prevalence of the comorbidity of substance use and that concurrent substance use over time may be related to more adverse psychosocial outcomes, understanding the longitudinal trajectories of comorbid substance use and their sequelae might aid the design of more effective prevention and treatment programs for long-term polysubstance use.

Building on the work of Jackson et al.,6 the current study was unique in several respects. First, we examined concurrent triple comorbid trajectories of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use. Second, the sample consisted of racial/ethnic minority adults from varied socioeconomic backgrounds. Third, we used a life-span approach and followed up the participants from adolescence into adulthood. Our outcome variables, ASPD and GAD, were selected to represent both externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Our specific hypotheses were as follows:

There will be approximately 5 to 7 trajectory groups, consisting of the high use of (1) tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana; (2) alcohol and marijuana; (3) alcohol and tobacco; (4) tobacco only; (5) alcohol only; and (6) marijuana only; or (7) nonuse.

Membership in the triple comorbid trajectory group (tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use) will be associated with a greater likelihood of having ASPD and GAD in adulthood than will membership in the alcohol and marijuana users group and the alcohol and tobacco users group.

Membership in the triple comorbid trajectory group of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use will be associated with a greater likelihood of having ASPD and GAD than will membership in the alcohol use only or tobacco use only trajectory group.

Membership in the triple comorbid trajectory group will be related to a greater likelihood of having ASPD or GAD in adulthood than will membership in the nonuse trajectory group.

METHODS

This study (n = 816; 52% African American, 48% Puerto Rican) was based on time waves 2 to 5 of the Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, a psychosocial investigation of urban African American and Puerto Rican individuals. Data were first collected in 1990 (time 1; T1, n = 1332; mean age = 14.1 years; SD = 1.3 years) when the participants were students attending schools in the East Harlem area of New York City. The data were collected by the National Opinion Research Center at time 2 (T2; 1994–1996; n = 1190; mean age = 19.2 years; SD = 1.5 years) in person or by telephone. At time 3 (T3), we randomly selected 662 participants from the T2 sample because of budget limitations. The Survey Research Center of the University of Michigan collected the data at T3 (2000–2001; n = 662; mean age = 24.4 years; SD = 1.3 years). The data were collected by our research group at time 4 (T4; 2004–2006; n = 838; mean age = 29.2 years; SD = 1.4 years) and at time 5 (T5; 2007–2010; n = 816; mean age = 32.3 years; SD = 1.3 years). Additional information about the study methodology is available from a previous report.23

We compared the T1 control variables for the 816 individuals who participated at both T1 and T5 with those for the 516 who participated at T1 but not at T5. Significantly fewer men participated at T5 (40%) compared with those who did not participate at T5 (57%; χ21 = 36.2; P < .001). The mean score of T1 self-deviance among T5 nonparticipants was significantly higher than among the T5 participants (t1 = 2.7; P < .01). No significant differences were seen in depressed mood at T1 or the percentages of African American and Puerto Rican adults who participated at T1 and T5 compared with those who participated at T1 but not T5.

Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) shows a comparison of the African American and Puerto Rican participants in our sample with respect to alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use; ASPD; and GAD. Table B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) contains the comparisons between the individuals who participated in all waves of the study (n = 523) and those who participated at T5 (the current study) but did not participate in 1 or more of the earlier waves (n = 293).

Measures

Tobacco use, alcohol use, and marijuana use in the past year were measured from T2 to T5 (mean age = 19–32 years). The 6 control variables for the analyses consisted of gender and race/ethnicity self-reported at T1, T1 self-deviance, T1 depressed mood, poverty at T5, and educational level at T5. Self-deviance and depressed mood at T1 were used as proxy measures for ASPD and GAD because we did not have these measures at T1. T1 self-deviance and T1 depressed mood were correlated with T5 ASPD and T5 GAD, respectively (P < .01). Table 1 lists the scales, time wave(s), references, response range, sample item, and Cronbach α (or interitem correlation) for the independent and control variables.

TABLE 1—

Independent and Control Variables: Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, 1990–2010

| Scale | No. of Items (Cronbach α or Interitem Correlation) | Sample Item | Response Range |

| Independent variables | |||

| Tobacco use24 (T2–T5) | 1 | “How many cigarettes a day did you smoke in the past year?” | (0) none at all |

| (4) ≥ about 1.5 packs/d | |||

| Alcohol use25 (T2–T5) | 1 | “How often did you drink beer, wine, or hard liquor in the past year?” | (0) none at all |

| (4) ≥ 3 or 4 drinks/d | |||

| Marijuana use26 (T2–T5) | 1 | “How often have you used marijuana in the past year?” | (0) never |

| (4) ≥ once a week | |||

| Control variables | |||

| Gender (T1) | 1 | Female = 1; male = 2 | |

| Race/ethnicity (T1) | 1 | African American = 1; Puerto Rican = 2 | |

| Self-deviance27 (T1) | 10 (α = .78) | “During the past 5 years, how often have you broken into a house or building which you’re not supposed to be in?” | (1) never |

| (5) ≥ 5 times | |||

| Depressed mood28 (T1) | 2 (interitem correlation = 0.47; P < .001) | “Do you sometimes feel unhappy, sad, or depressed?” | (1) not at all |

| (4) extremely | |||

| Poverty (T5) | 1 | “In the past year, what was your total household income, from all sources?” | Income ≤ $10 000 = 1; otherwise = 0 |

| Educational level (T5) | 1 | “What is the last year of school you completed?” | (0) ≤ 11th grade |

| (7) Postgraduate business, law, medical, master’s, or doctoral program |

Note. The percentages of missing data for alcohol use at T3, T4, and T5 were 33%, 11%, and 0.2%, respectively. For tobacco use, the percentages of missing values at T3 and T4 were 33% and 11%, respectively. The percentages of missing values for marijuana use at T3, T4, and T5 were 33%, 11%, and 1%, respectively. Missing values for depressive mood and self-deviance, both at T1, were 0.6% and 6%, respectively.

Antisocial personality disorder and generalized anxiety disorder (T5).

ASPD was assessed with an adaptation of the University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview ASPD measure.29 As shown in Box 1, the participants were asked a series of 13 questions and received a score of 1 on the measure of adult ASPD if they answered “yes” to 2 or more of the questions preceded by “Before you were 15 years old . . . ” and “yes” to 3 or more of the questions that began “Since you were 15 years old . . . ”. Otherwise, if these criteria were not met, the participant received a score of zero. The internal reliability of the ASPD measure was satisfactory (α = .82).

Diagnostic Criteria Adapted From the University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview for Antisocial Personality Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder

| Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD)a | |

| Before you were 15 y old, did you . . . | Since you were 15 y old, have you . . . |

| 1. Repeatedly skip school or run away from home overnight? | 7. Repeatedly behaved in a way that others would consider irresponsible, like failing to pay for things you owed or deliberately not working to support yourself? |

| 2. Repeatedly lie, cheat, “con” others, or steal? | 8. Done things that are illegal even if you didn’t get caught (e.g., destroying property, shoplifting, stealing, selling drugs, or committing a felony)? |

| 3. Start fights or bully, threaten, or intimidate others? | 9. Been in physical fights repeatedly (including physical fights with your spouse or children)? |

| 4. Deliberately destroy things or start fires? | 10. Often lied or “conned” other people to get money or pleasure, or lied just for fun? |

| 5. Deliberately hurt animals or people? | 11. Exposed others to danger without caring? |

| 6. Force someone to have sex with you? | 12. Felt no guilt after hurting, mistreating, lying to, or stealing from others, or after damaging property? |

| 13. Often acted impulsively, that is, done things without considering the consequences? | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)b | |

| 1. Within the last 5 y, have you had a period of at least 6 mo when you worried excessively or were anxious about several things? | 4. Did you feel restless, keyed up, or on edge? |

| During this period of 6 mo or more . . . | |

| 2. Were these worries present most days? | 5. Did you feel tense? |

| 3. Was it difficult to control the worries or did they interfere with your ability to focus on what you were doing? | 6. Did you feel tired or weak, or were you easily exhausted? |

| 7. Did you have difficulty concentrating or find your mind going blank? | |

| 8. Did you feel irritable? | |

| 9. Did you have sleep problems (difficulty falling asleep, waking up in the middle of the night, early-morning wakening, or sleeping excessively)? | |

Antisocial personality disorder = “Yes” to 2 or more of questions 1–6 (left-hand column) + “yes” to 3 or more of questions 7–13 (right-hand column).

Generalized anxiety disorder = “Yes” to questions 1–3 (left-hand column) + “yes” to 3 or more of questions 4–9 (right-hand column).

GAD was assessed with an adaptation of the University of Michigan Composite International Diagnostic Interview GAD measure.30 The participants were asked 9 questions about their affect and behaviors that had occurred in the past 5 years and lasted for at least 6 months (Box 1). If they answered “yes” to the first 3 questions and “yes” to 3 or more of the last 6 questions, then the participant received a score of 1 on the measure of GAD; otherwise, the participant received a score of zero. The internal reliability of this measure was satisfactory (α = .94). All variables in the current study were based on participant self-report.

Analytic Procedure

We used Mplus31 to obtain the 3 variable trajectories of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use from T2 to T5. Tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use at each time point were treated as censored normal variables. We used the Bayesian Information Criterion to determine the number of trajectory groups.32 The model chosen has the smallest absolute value of the Bayesian Information Criterion provided that no group has an estimated prevalence less than 5%. The observed trajectories for each of the groups consisted of the averages of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use, respectively, at each point in time when each participant was assigned to the group with the largest Bayesian posterior probability.

We applied the full information maximum likelihood approach for missing data.31 There were no missing values for ASPD, GAD, gender, race/ethnicity, alcohol use at T2, tobacco use at T2 and T5, and marijuana use at T2. The percentages of missing values for the other measurements (e.g., alcohol use at T3–T5) are reported as a footnote to Table 1.

We then conducted logistic regression analyses to examine whether the Bayesian posterior probability of the trajectory group of comorbid high use of all 3 substances, compared with the Bayesian posterior probabilities of each of the other substance use trajectory groups from T2 to T5, was associated with ASPD and GAD at T5, after we controlled for gender (T1), race/ethnicity (T1), educational level (T5), poverty (T5), self-deviance (T1), and depressed mood (T1).

RESULTS

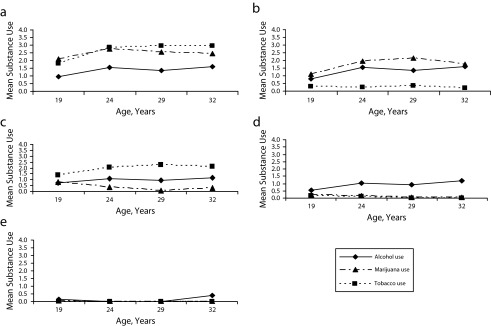

We selected a 5-group model based on the Bayesian Information Criterion and a group size of at least 5% in each group.33–35 The Bayesian Information Criteria were 21 272, 20 872, 20 607, 20 509, and 20 436 for the 2-, 3-, 4-, 5-, and 6-group model, respectively. Although the 6-group model had the smallest Bayesian Information Criterion score, one of the groups had a prevalence of only 4%. Hence we selected the 5-group model. Figure 1 presents the observed trajectories and the percentages of the sample who were members of each of the 5 trajectory groups. The mean Bayesian posterior probability of each trajectory group ranged from 86% to 95%, which indicated a good classification.

FIGURE 1—

Triple trajectories of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use among a community sample of 816 African American and Puerto Rican residents at mean ages of 19 to 32 years by (a) use of all 3 substances, (b) marijuana and alcohol use, (c) tobacco and alcohol use, (d) alcohol use only, and (e) nonuse: Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, 1990–2010.

Note. The vertical axes denote quantity of substance use with answer options as follows: for alcohol use: none at all (0), less than once a week (1), once a week to several times a week (2), 1 or 2 drinks a day (3), 3 or 4 drinks a day or more (4); for tobacco use: none at all (0), a few cigarettes or less a week (1), 1–5 cigarettes a day (2), about half a pack a day (3), about a pack a day (4), about one and half packs a day or more (5); for marijuana use: never (0), a few times a year or less (1), about once a month (2), several times a month (3), once a week or more (4). The sample sizes for each group were n = 186 (23%); for use of all three substances, n = 118 (14%) for marijuana and alcohol use, n = 128 (16%) for tobacco and alcohol use, n = 311 (38%) for alcohol use only, and n = 73 (9%) for nonuse.

The 5 trajectory groups were named as follows:

use of all 3 substances (triple trajectories of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use; prevalence = 23%; mean Bayesian posterior probability = 93%),

marijuana and alcohol use (prevalence = 14%; mean Bayesian posterior probability = 89%),

tobacco and alcohol use (prevalence = 16%; mean Bayesian posterior probability = 91%),

alcohol use only (prevalence = 38%; mean Bayesian posterior probability = 95%), and

nonuse (i.e., individuals who abstained from the use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana; prevalence = 9%; mean Bayesian posterior probability = 86%).

Our analysis did not support a tobacco use only or a marijuana use only trajectory group. Table C (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) presents summary statistics for each of the 5 trajectory groups.

Table 2 shows the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) for ASPD and GAD in the logistic regression analyses. The reference variable in the table is the Bayesian posterior probability of the use of all 3 substances (alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana). The Bayesian posterior probability of the use of all 3 substances group was associated with an increased likelihood of being classified as having ASPD at T5 compared with the respective Bayesian posterior probabilities of the other trajectory groups (i.e., the tobacco and alcohol use group: AOR = 3.39; 95% CI = 1.35, 8.51; P < .01; the alcohol use only group: AOR = 3.87; 95% CI = 1.86, 8.08; P < .001; and the nonuse group: AOR = 6.83; 95% CI = 1.14, 40.74; P < .05). There was also a trend of the Bayesian posterior probability of the use of all 3 substances group compared with the Bayesian posterior probability of the marijuana and alcohol use group with respect to having ASPD at T5, but this trend did not reach statistical significance (AOR = 2.16; 95% CI = 0.97, 4.79; P < .1). The Bayesian posterior probability of membership in the group that used all 3 substances also was associated with an increased likelihood of GAD at T5 compared with the Bayesian posterior probabilities of the alcohol use only (AOR = 2.22; 95% CI = 1.33, 3.70; P < .01) and the nonuse (AOR = 4.35; 95% CI = 1.63, 11.63; P < .001) groups. With regard to the control variables, men were more likely to be classified as having ASPD at T5 (AOR = 1.89; 95% CI = 1.06, 3.32; P < .05). Participants who reported more self-deviance at T1 also were more likely to have ASPD at T5 (AOR = 1.06; 95% CI = 1.02, 1.10; P < .01). Puerto Rican participants were more likely than African American participants to have GAD at T5 (AOR = 1.51; 95% CI = 1.04, 2.18; P < .05) after we controlled for the other variables.

TABLE 2—

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Triple Trajectories of Tobacco, Alcohol, and Marijuana Use as Predictors of Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): Harlem Longitudinal Development Study, 1990–2010

| Predictor(s) | ASPD, AOR (95% CI) | GAD, AOR (95% CI) |

| Gender | 1.89* (1.06, 3.32) | 0.71 (0.48, 1.05) |

| Race/ethnicity | 1.03 (0.61, 1.75) | 1.51* (1.04, 2.18) |

| Self-deviance (T1) | 1.06** (1.02, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) |

| Depressed mood (T1) | 1.13 (0.97, 1.31) | 1.11 (0.99, 1.23) |

| Poverty (T5) | 1.13 (0.58, 2.20) | 1.02 (0.61, 1.70) |

| Educational level (T5) | 0.94 (0.82, 1.08) | 1.08 (0.99, 1.17) |

| Use of all 3 substances (G1) vs marijuana and alcohol (G2) | 2.16 (0.97, 4.79) | 1.01 (0.56, 1.83) |

| Use of all 3 substances (G1) vs tobacco and alcohol (G3) | 3.39** (1.35, 8.51) | 1.53 (0.83, 2.80) |

| Use of all 3 substances (G1) vs alcohol only (G4) | 3.87*** (1.86, 8.08) | 2.22** (1.33, 3.70) |

| Use of all 3 substances (G1) vs nonuse (G5) | 6.83* (1.14, 40.74) | 4.35*** (1.63, 11.63) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; G1 = trajectory group 1; G2 = trajectory group 2; G3 = trajectory group 3; G4 = trajectory group 4; G5 = trajectory group 5; T1 = time 1; T5 = time 5. Gender, race/ethnicity, self-deviance (T1), depressed mood (T1), poverty (T5), and educational level (T5) were controlled for.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

DISCUSSION

We focused on the developmental course of the comorbid use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana, spanning the periods from adolescence to adulthood, among urban African American and Puerto Rican individuals. This was the first investigation of triple comorbid trajectories of substance use and of their longitudinal associations with 2 measures of psychopathology in adulthood: ASPD and GAD.

Consistent with results from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health,4 our findings showed that almost one quarter of the total sample (23%) used all 3 substances concurrently and that membership in this group was the second largest after the alcohol use only group (38%). Furthermore, 2 trajectory groups (the use of all 3 substances and the marijuana and alcohol use groups) significantly increased their substance use from T2 to T5, whereas the 2 groups that used legal substances (the tobacco and alcohol use and the alcohol use only groups) slightly increased their legal substance use from ages 19 to 32 years. These findings are partially consistent with the literature, which generally has shown that substance use prevalence peaks around the mid-20s and then decreases substantially as individuals transition into adult roles.36,37

It is currently unclear why our sample did not show this decrease. Urban African American and Puerto Rican residents may have been exposed to sociodemographic and social factors (e.g., drug availability, normative behaviors) that are predictive of substance use in adulthood. In addition, there may have been a historical shift in the pattern of long-term substance use among this age cohort (e.g., linked with changing social roles) that affected not only our sample but also other racial/ethnic groups that were not assessed in this study. For example, on the basis of the Monitoring the Future study, Jager et al.38 reported an increase in the level of heavy drinking among a multiethnic sample of young adult men after adjustment for college attendance, marriage, and parenthood. Future research might take into account social and contextual characteristics, such as access to substance use treatment, which could affect racial/ethnic differences in adult substance use.

Our findings also showed that membership in the use of all 3 substances group (comorbid triple trajectories) was more highly associated with the likelihood of having ASPD than was membership in any other trajectory group, as well as more predictive of the likelihood of GAD compared with the alcohol use only and nonuse groups. Thus, our results suggest that the use of all 3 substances trajectory group may be especially at risk for adverse mental health outcomes.

Use of All 3 Substances vs Nonuse as Predictive of ASPD

Persons engaged in long-term comorbid substance use may have fewer ties to conventional individuals and institutions (e.g., parental, school, or employment bonds), which increases their risk for antisocial behaviors.39,40 Long-term comorbid substance users are also more likely to affiliate with deviant peers and to be exposed to antisocial role models, such as drug abusers.8,41 Substance use also has been found to hamper the lessening of antisocial behaviors among young adults.42 In addition, evidence suggests that both substance use and externalizing psychopathology may share common vulnerabilities.43,44

Use of All 3 Substances vs Nonuse as Predictive of GAD

Membership in the comorbid triple trajectories group was more highly predictive of GAD than was membership in either the alcohol use only or the nonuse trajectory group. No significant difference was found between the triple comorbid trajectory group and the marijuana and alcohol use or the tobacco and alcohol use groups with respect to the likelihood of having GAD at T5. Thus, our findings suggest that long-term comorbid substance use involving the concurrent use of 2 or 3 substances is a risk factor for GAD in adulthood. Individuals who drink alcohol, smoke cigarettes, and use marijuana may be more likely to experience GAD because of greater interpersonal and functional impairment related to their substance use,45,46 such as more spousal or partner conflict, cognitive deficits, less academic achievement, poorer job performance, and more unemployment.22,45–48 In addition, the increased likelihood of membership in the use of all 3 substances group versus the alcohol use only group with respect to having GAD may be a result of the anxiety-inducing effects of tobacco, marijuana, and heavy alcohol use, whereas low levels of alcohol use have been found to mitigate anxiety, at least, in the short term.49,50

Gender and Racial/Ethnic Differences in ASPD and GAD

Consistent with most prior research on both community and clinical samples (including substance abusers), the men in our sample were more likely than the women to meet criteria for ASPD at T5,51–56 whereas the women had a higher prevalence of GAD at T5.53,54,57,58 Both biological and socialization factors may help explain why men tend to show more aggressive and externalizing behavior patterns and disorders (e.g., ASPD),59–62 whereas women, in general, experience internalizing problems (e.g., GAD).63 Although preliminary evidence suggests that hormonal differences between men and women may play a role in gender differences in anxiety,61,63–65 a detailed discussion of these effects is beyond the scope of this article. In addition, evidence indicates that women are socially reinforced to be less aggressive than men.66,67

Limitations and Strengths

This study had some limitations. First, our data were based on self-reports rather than official records. However, self-report data have been shown to yield reliable results.68,69 Another limitation was the use of proxies for earlier ASPD and GAD (i.e., self-deviance and depression, which were assessed at T1). In addition, the measure of depressed mood at T1 consisted of only 2 items. Furthermore, we did not assess factors that may underlie the relations of the trajectories of substance use and ASPD and GAD, such as the earlier family environment; a familial history of substance use, ASPD, or GAD; or the participant’s employment status, incarceration history, or exposure to traumatic events (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder). Although the relation between uncontrolled factors cannot be discounted, findings from other studies with different samples were consistent with the suggestion that substance use has an association with ASPD and GAD.7,37,42

The study also had several strengths. First, it was unique in its simultaneous examination of trajectories of the use of 3 substances (tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana) and their relation to ASPD and GAD. Second, unlike most research that focuses on only 1 or 2 points in time, we assessed substance use over a span of almost 15 years, covering important developmental stages from ages 19 to 32 years. Third, the prospective nature of the data enabled us to go beyond the limits of a cross-sectional approach and to take into consideration the temporal sequencing of variables.

Conclusions and Clinical Implications

The results have implications for public health and treatment. The stability or increase in substance use in several trajectory groups in our sample suggests that some urban African American and Puerto Rican individuals may not experience the decrease in substance use during the late 20s that has been documented among other groups. Timely prevention and treatment, therefore, are imperative among these individuals. From a clinical perspective, individuals presenting with comorbid tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use should be evaluated for other substance use as well as for ASPD, GAD, and other psychiatric disorders. Efforts made to reduce comorbid substance use may help decrease the prevalence of ASPD and GAD58 as well as other psychiatric disorders. Thus, appropriate prevention and treatments should be adapted to address the use of multiple substances that are comorbid with ASPD and GAD. Because members of the group that used all 3 substances experienced the most adverse consequences with respect to comorbid psychopathology, and because comorbid substance use and ASPD or GAD have been shown to predict more adverse outcomes (e.g., additional mental health problems, greater functional impairment, and higher levels of substance use70–73), it is particularly imperative for these individuals to receive timely prevention and appropriate treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Research Scientist award DA00244 and grant DA005702) and by the National Cancer Institute (grant CA084063), all awarded to J. S. Brook.

Human Participant Protection

The institutional review board of the New York University School of Medicine approved the study for time waves 4 and 5, and the institutional review boards of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the New York Medical College (our former affiliations) approved the study’s procedures for earlier waves of data collection. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health for each wave. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at each time wave. At time wave 2, passive consent was obtained from the parents of participants who were minors (< 18 years).

References

- 1.Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. The relationship between cannabis use and other substance use in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;64(3):319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duhig AM, Cavallo DA, McKee SA, George TP, Krishnan-Sarin S. Daily patterns of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in adolescent smokers and nonsmokers. Addict Behav. 2005;30(2):271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iglesias V, Cavada G, Silva C, Cáceres D. Consumo precoz de tabaco y alcohol como factores modificadores del riesgo de uso de marihuana [Early tobacco and alcohol consumption as modifying risk factors on marijuana use] Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41(4):517–522. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102007000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results From the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-41. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. HHS publication (SMA) 11-4658. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulenberg JE, Merline AC, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Laetz VB. Trajectories of marijuana use during the transition to adulthood: the big picture based on national panel data. J Drug Issues. 2005;35(2):255–279. doi: 10.1177/002204260503500203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Schulenberg JE. Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult substance use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(5):723–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in adolescence and young adulthood. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1123–1135. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication [published erratum appears in Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(7):709] Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milich R, Lynam D, Zimmerman R et al. Differences in young adult psychopathology among drug abstainers, experimenters, and frequent users. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11(1):69–88. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)00021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Windle M, Wiesner M. Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: predictors and outcomes. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(4):1007–1027. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404040118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang B, Grant BF, Dawson DA et al. Race-ethnicity and the prevalence and co-occurrence of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, alcohol and drug use disorders and Axis I and II disorders: United States, 2001 to 2002. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47(4):252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mericle AA, Ta Park VM, Holck P, Arria AM. Prevalence, patterns, and correlates of co-occurring substance use and mental disorders in the United States: variations by race/ethnicity. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(6):657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith SM, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein R, Huang B, Grant BF. Race/ethnic differences in the prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med. 2006;36(7):987–998. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Colliver JD, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of DSM-IV antisocial personality syndromes and alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(6):677–685. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein RB, Compton WM, Pulay AJ et al. Antisocial behavioral syndromes and DSM-IV drug use disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(2-3):145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orlando M, Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ. Concurrent use of alcohol and cigarettes from adolescence to young adulthood: an examination of developmental trajectories and outcomes. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(8):1051–1069. doi: 10.1081/JA-200030789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caldeira KM, O’Grady KE, Vincent KB, Arria AM. Marijuana use trajectories during the post-college transition: health outcomes in young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(3):267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(1):193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Barnes GM. Co-occurrence of alcohol and cigarette use among adolescents. Addict Behav. 2001;26(1):63–78. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmid B, Hohm E, Blomeyer D et al. Concurrent alcohol and tobacco use during early adolescence characterizes a group at risk. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42(3):219–225. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bray JW, Zarkin GA, Dennis ML, French MT. Symptoms of dependence, multiple substance use, and labor market outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26(1):77–95. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brook JS, Brook DW, Zhang C. Psychosocial predictors of nicotine dependence in Black and Puerto Rican young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(6):959–967. doi: 10.1080/14622200802092515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance-United States, 1999. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 2000;49(5):1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Room R. Measuring alcohol consumption in the United States: methods and rationales. In: Kozlowski LT, Annis HM, Cappell HD, editors. Research Advances in Alcohol and Drug Problem. Vol 10. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 39–80. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown SA, Meyer MG, Lippke L, Tapert SF, Stewart DG, Vik PW. Psychometric evaluation of the customary drinking and drug use record (CDDR): a measure of adolescent alcohol and drug involvement. J Stud Alcohol. 1998;59(4):427–438. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huizinga DH, Menard S, Elliot DS. Delinquency and drug use: temporal and developmental patterns. Justice Q. 1989;6(3):419–455. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1):1–15. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830190102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittchen HU, Zhao S, Kessler RC, Eaton WW. DSM-III-R generalized anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(5):355–364. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950050015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6(2):461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delucchi KL, Matzger H, Weisner C. Dependent and problem drinking over 5 years: a latent class growth analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74(3):235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dodge KA, Laird RD. A semiparametric group-based approach to analyzing developmental trajectories in child conduct problems. Paper presented at: biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; April 1999; Albuquerque, NM. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piquero AR, Monahan KC, Glasheen C, Schubert CA, Mulvey E. Does time matter? Comparing trajectory concordance and covariate association using time-based and age-based assessments. Crime Delinq. 2012;59(5):738–763. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: gender and racial/ethnic differences. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(2):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lansford JE, Erath S, Yu T, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Bates JE. The developmental course of illicit substance use from age 12 to 22: links with depressive, anxiety, and behavior disorders at age 18. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(8):877–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01915.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jager J, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Historical variation in drug use trajectories across the transition to adulthood: the trend toward lower intercepts and steeper, ascending slopes. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25(2):527–543. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henry KL. Low prosocial attachment, involvement with drug-using peers, and adolescent drug use: a longitudinal examination of mediational mechanisms. Psychol Addict Behav. 2008;22(2):302–308. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sampson RJ, Laub JH. A life-course view of the development of crime. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2005;602(1):12–45. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF, Deffenbacher JL. Primary socialization theory: the influence of the community on drug use and deviance, III. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33(8):1629–1665. doi: 10.3109/10826089809058948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hussong AM, Curran PJ, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Carrig MM. Substance abuse hinders desistance in young adults’ antisocial behavior. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(4):1029–1046. doi: 10.1017/s095457940404012x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hicks BM, Schalet BD, Malone SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Psychometric and genetic architecture of substance use disorder and behavioral disinhibition measures for gene association studies. Behav Genet. 2011;41(4):459–475. doi: 10.1007/s10519-010-9417-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiologic connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: modeling the externalizing spectrum. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(3):411–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(40):E2657–E2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaeth PA, Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Rodriguez LA. Hispanic Americans Baseline Alcohol Survey (HABLAS): alcohol-related problems across Hispanic national groups. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(6):991–999. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green KM, Ensminger ME. Adult social behavioral effects of heavy adolescent marijuana use among African Americans. Dev Psychol. 2006;42(6):1168–1178. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McFarlin SK, Fals-Stewart W. Workplace absenteeism and alcohol use: a sequential analysis. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16(1):17–21. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.16.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonn-Miller MO, Zvolensky MJ, Johnson KA. Uni-morbid and co-occurring marijuana and tobacco use: examination of concurrent associations with negative mood states. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(1):68–77. doi: 10.1080/10550880903435996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall W, Degenhardt L, Lynskey M. The Health and Psychological Effects of Cannabis Use. 2nd ed. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2001. Monograph Series No. 44. Available at: http://www.beckleyfoundation.org/pdf/hall_HealthAndPsychologicalEffects_2001.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barry KL, Fleming MF, Manwell LB, Copeland LA. Conduct disorder and antisocial personality in adult primary care patients. J Fam Pract. 1997;45(2):151–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF et al. An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: evidence from a national sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121(1):282–288. doi: 10.1037/a0024780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flynn PM, Craddock SG, Luckey JW, Hubbard RL, Dunteman GH. Comorbidity of antisocial personality and mood disorders among psychoactive substance-dependent treatment clients. J Pers Disord. 1996;10(1):56–67. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex Differences in Antisocial Behaviour: Conduct Disorder, Delinquency and Violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turner RJ, Gil AG. Psychiatric and substance use disorders in South Florida: racial/ethnic and gender contrasts in a young adult cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(1):43–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age of onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Comorbidity: Addiction and Other Mental Illnesses. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2010. NIH publication 10-5771. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/comorbidity-addiction-other-mental-illnesses. Accessed November 8, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bennett S, Farrington DP, Huesmann LR. Explaining gender differences in crime and violence: the importance of social cognitive skills. Aggress Violent Behav. 2005;10(3):263–288. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caspi A, Lynam D, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Unraveling girls’ delinquency: biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;29(1):19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ngun TC, Ghahramani N, Sánchez FJ, Bocklandt S, Vilain E. The genetics of sex differences in brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2011;32(2):227–246. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burnette ML. Gender and the development of oppositional defiant disorder: contributions of physical abuse and early family environment. Child Maltreat. 2013;18(3):195–204. doi: 10.1177/1077559513478144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Altemus M. Sex differences in depression and anxiety disorders: potential biological determinants. Horm Behav. 2006;50(4):534–538. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seeman MV. Psychopathology in women and men: focus on female hormones. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(12):1641–1647. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.12.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Solomon MB, Herman JP. Sex differences in psychopathology: of gonads, adrenals and mental illness. Physiol Behav. 2009;97(2):250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sylvester M, Hayes SC. Unpacking masculinity as a construct: ontology, pragmatism, and an analysis of language. Psychol Men Masc. 2010;11:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tieger T. On the biological basis of sex differences in aggression. Child Dev. 1980;51(4):943–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lynskey MT, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. The origins of the correlations between tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis use during adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998;39(7):995–1005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mennes CE, Abdallah AB, Cottler LB. The reliability of self-reported cannabis abuse, dependence and withdrawal symptoms: a multisite study of differences between general population and treatment groups. Addict Behav. 2009;34(2):223–226. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alegría AA, Hasin DS, Nunes EV. Comorbidity of generalized anxiety disorder and substance use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1187–1195. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05328gry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vida R, Brownlie EB, Beitchman JH et al. Emerging adult outcomes of adolescent psychiatric and substance use disorders. Addict Behav. 2009;34(10):800–805. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Magidson JF, Liu SM, Lejuez CW, Blanco C. Comparison of the course of substance use disorders among individuals with and without generalized anxiety disorder in a nationally representative sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(5):659–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Compton WM, 3rd, Cottler LB, Jacobs JL, Ben-Abdallah A, Spitznagel EL. The role of psychiatric disorders in predicting drug dependence treatment outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(5):890–895. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]