Summary

Both electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) localize epileptiform activity but may yield different results. This discordance may arise from different detection capabilities or from different data collection and interpretation techniques. Comparisons of MEG and EEG have focused on detection of individual spikes. However, side-by-side comparisons of results as used in the clinical setting is lacking. In this report, we present our empirical comparison. We reviewed 58 simultaneous MEG-EEG recordings (35 paired-sensors, 23 whole-head) from a diverse epilepsy population, comparing previous clinical MEG interpretations with new blinded EEG interpretations, noting lobar concordance of readers’ judgments of regional abnormalities. A second-pass unblinded analysis, using all available clinical data, assessed the relative contribution and plausibility of the results of each technique. Concordance was high (85%) overall. Discordance was sometimes caused by constraints imposed by MEG dipole fitting techniques. Even when results of the techniques did not match, MEG often disambiguated the clinical scenario, especially when combined with imaging information. Thoughtful analysis of combined MEG-EEG datasets, beyond algorithm-based interictal spike detection, can help guide clinical decision-making even when concordance between techniques is imperfect. In some cases, EEG and MEG are synergistic and provide complementary information.

Keywords: Magnetoencephalography, Electroencephalography, Epilepsy, Concordance

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) and electroencephalography (EEG) are both neurophysiological techniques used in the evaluation of people with epilepsy to record interictal epileptiform discharges that give clues to location of onset of seizures (eg, Minassian et al., 1999). This can help clarify an individual’s seizure type and epilepsy syndrome (Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes; Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy, 1989) and may also indicate whether resective surgery is a treatment option. MEG is not limited by conductivity issues, as is EEG, and is thought to be more sensitive to tangential sulcal sources. As MEG has developed as a technology, source modeling techniques have grown in tandem, making it possible to perform single dipole analysis and then to superimpose results on anatomic MRI images (this is known as magnetic source imaging, or MSI). EEG, by contrast, is in routine clinical practice visually inspected; computer-aided source analysis is not part of standard practice in most EEG laboratories. For a review of technical and practical matters surrounding the use of EEG and MEG in epilepsy, see Barkley et al. (2003).

Because of these differences in measurement and analysis techniques, it is to be expected that the results of routine scalp EEG and MEG will not be identical. This discordance between results may in part be due to conductivity issues. Some investigators have attempted to minimize this variable by comparing MEG results with electrocochleography (ECoG) in the same patients (Nakasato et al., 1994; Oishi et al., 2002). Under these conditions, with issues of conductivity minimized, it has been suggested that spike-to-spike concordance depends on the location of spike origin, MEG being more sensitive for lateral convexity versus deep basal temporal sources (Oishi et al., 2002). Intracranial recordings are typically performed after MEG has already been performed, and, in fact, MEG may have value in planning intracranial electrode placement. Thus, it is of practical value to know the concordance between scalp EEG and MEG.

Most investigators have attempted to answer this question by looking at spike-to-spike concordance. Lin et al. (2003) found a 78.3% concordance rate in mesial and lateral temporal lobe epilepsy and suggested that MEG was better at detecting lateral temporal spikes not seen on EEG. Yoshinaga et al. (2002) studied seven patients with intractable focal epilepsy: Although three had clear spikes apparent on both EEG and on MEG, two had EEG spikes only and two had MEG spikes only, but this discordance could be resolved by using averaging techniques or estimated dipoles for nonspike MEG patterns. The use of a higher-density scalp array, improved EEG analytic tools, and back-averaging EEG on MEG spikes also improved EEG-MEG spike concordance in a case reported recently (Rodin et al., 2004). More recently, the special case of EEG-MEG spike concordance when polymicrogyria changes cortical sulcation was addressed, with concordance seeming to depend on orientation of sources: MEG was limited in its ability to detect spike onset for radial sources, though such spike onsets were clearly demonstrated on simultaneous EEG; MEG showed propagated spikes after a lag from EEG spike onset (Bast et al., 2005).

As Baumgartner pointed out in his 2004 review, “a ‘fair’ head-to-head comparison between the two techniques performed in a clinical setting with a comparable number of channels and comparable source localization techniques is … urgently needed (p. 1064)” (Baumgartner, 2004), and the recent study of Scheler et al. (2006) comparing MEG and EEG source localizations begins this important work. We would also point out that we are lacking head-to-head comparisons of the results of MEG and of a comprehensive visual analysis of a simultaneous scalp EEG, as they are performed in typical clinical situations. Past studies, as we review above, have focused on spike-by-spike concordance between the two techniques and/or between MEG and ECoG. However, EEG readers do more than detect and localize spikes when approaching a record, and the judgment that a record reveals a focal abnormality is made on a variety of grounds, including focal slowing or focal loss of normal background rhythms (though these focal abnormalities are of course nonspecific and do not in themselves mean that a region is epileptogenic). Therefore, in our study, rather than focusing exclusively on the ability of each technique to capture an individual spike, we took a broader view, assessing the frequency and nature of discordance and concordance between the global interpretation of scalp EEG and of simultaneous MEG as they are performed in the clinical setting. We proceeded without the use of special EEG source localization techniques or high-density EEG recording, as we were seeking to compare MEG with EEG as performed in most outpatient EEG settings.

Thus, our study is not intended to add to the growing literature comparing MEG and EEG spike-for-spike. Nor is it intended to be a fair comparison between the best scalp EEG source localization techniques (i.e., high density recording, realistic head modeling, and dipole analysis). Instead, it is meant to address the clinical question: “of what use is routine MEG compared to routine scalp EEG in the evaluation of patients with epilepsy?” We share this goal with Knake et al. (2006), who published a similar series recently, though they focused on patients undergoing presurgical workup. Our clinical impression has been that the two techniques—routine low-density EEG and routine MEG—are complementary, and we wanted to see if this impression was warranted. In addition, dipole modeling of EEG/MEG spikes alone misses valuable information contained in the record that can indicate a focal region of abnormal cortical function (e.g., focal slowing on EEG and MEG, or focal low voltage fast activity on MEG), and we wanted to understand how this information could be used to enhance the value of the modalities.

METHODS

We reviewed simultaneously recorded 21-channel scalp EEG and paired 37-channel MEG studies performed on 35 consecutive consenting patients with epilepsy referred from physicians both within and outside of UCSF between 2002 and 2003. We also reviewed simultaneous 21-channel scalp EEG and 275-channel whole cortex MEG studies from 23 consenting patients studied in 2004 and 2005. All studies included a minimum of 45 minutes of recording time. Though the recordings were intended to be interictal, if a seizure happened to be recorded, as it was in three cases, the ictal M/EEG was analyzed along with the rest of the record. The clinical MEG data had previously been analyzed by a single experienced technologist (M.M.) as follows: After the data were band-pass filtered between 1 to 70 or 3 to 70 Hz, spikes were chosen for analysis based on duration (<80 ms), morphology, and lack of associated artifact (e.g., ECG, EMG, EOG). Although the MEG readers had access to the simultaneous EEG to help distinguish spikes from artifact, they also selected spikes that met criteria but appeared only on MEG. Spike onsets were chosen, and corresponding dipoles were fit by using the commercial software supplied by the manufacturer (paired-sensor: 4-D Neuroimaging, San Diego, Calif; whole-head: CTF Systems, VSM, Port Coquitlam, BC); dipoles with >97% correlation and >95% goodness-of-fit were selected and superimposed on patients’ MRI scans. Results of this MSI were also reviewed by the director of the laboratory (S.N.) and by the staff neuroradiologist who would generate a clinical report. EEG data were separately analyzed retrospectively by a neurophysiologist (H.E.K.) blinded to MEG results, using visual inspection of data presented in longitudinal bipolar and transverse montages, and focal abnormalities and epileptiform discharges were noted. The identification of spikes was based on duration (<80 ms), morphology, field, and lack of associated artifact. Lobar localization of epileptiform discharges was made based on published descriptions of neurophysiologic-anatomic correlations (Homan et al., 1987; Jasper, 1958); that is, T3 spikes were judged to arise from the midportion of the left temporal lobe.

We then grouped these studies, on the basis of the EEG and MEG findings reported in the blinded analysis, into two groups, concordant and discordant. These groups were further subdivided as follows (based loosely on a similar schema used to rate spike concordance in MEG/EEG datasets (Lin et al., 2003) and modified by R. Knowlton [personal communication]):

-

IA

Concordant, E+/M+: EEG and MEG results both showed epileptiform discharges in the same location (lobar concordance).

-

IB

Concordant, E−/M−: There were epileptiform discharges found with either method.

-

IC

Concordant, E+/M+ overlap: EEG and MEG both showed epileptiform discharges, but the locations of these were not 100% in agreement (e.g., one method suggested frontal and temporal foci, and the other suggested frontal only).

-

IIA

Discordant, E+/M−: EEG showed epileptiform discharges but MEG did not.

-

IIB

Discordant, E−/M+: MEG showed epileptiform discharges but EEG did not.

-

IIC

Discordant, E+/M+ no overlap: EEG and MEG both showed epileptiform discharges but in different locations with no overlap (e.g., one method suggested a frontal focus and one suggested a temporal focus).

Note that we did not compare individual spikes across modalities; concordance ratings were based on the overall conclusion taking the entire study (either EEG or MEG) into account. In the case of MEG, this was the clinical report, and in the case of EEG, this was the blinded EEG interpretation.

After this primary grouping analysis, we made a second unblinded pass through the data, comparing directly the MEG and EEG signals and incorporating the MSI and clinical data (as noted in Table 2, a through f) to place the results of the MEG and EEG within their clinical context. This enabled us to judge whether the discordance noted in the first pass analysis was true discordance—that is, based on actual differences in recorded signal— or pseudodiscordance—that is, based on differences in criteria for reporting patterns or in restrictions of source modeling.

TABLE 2A.

Type IA cases (E+/M+ Concordant)

| Type of Study | Case No. | Age | Sex | Seizure Type/Risk Factors | Neuroimaging | Video-EEG (scalp) | EEG | MEG/MSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | 2 | 13 | m | CPS with head turn to right and right arm flexion; known cortical dysplasia s/p one resection without improvement | MRI: right frontoparietal resection cavity | Right centroparietal semirhythmic slowing; multifocal spikes right and left centroparietal | Multifocal spikes right and left centroparietal | |

| PS | 3 | 16 | f | Brief CPS with staring; longer SPS with limb shaking, stiffening, salivation | MRI: normal; PET: possible left mid temporal hypometabolism | Ictal onset: right frontal | Right frontal and central spike and slow and polyspike and slow waves | Right frontal-central spikes |

| PS | 4 | 36 | f | SPS with clonic movements and sensory changes right hand and face; known left frontoparietal grade 2 astrocytoma, s/p resection | MRI: left frontoparietal resection cavity with peripheral rim of T2 prolongation involving the parenchyma deep to the cavity | Left temporal spikes; irregular left temporal slowing | Left temporal spikes | |

| PS | 5 | 20 | m | CPS with flexion at waist, bilateral arm shaking, bilateral leg stiffening; history of head trauma | MRI: extensive bilateral white matter disease with multiple foci of chronic hemorrhage and mild hydrocephalus ex vacuo | Ictal onset: right temporal onset; interictal: bilateral independent temporal spikes | Right temporal spikes | Right temporal sharp waves |

| PS | 6 | 46 | m | SPS with fear; CPS | MRI normal | Left central and frontal spikes; bifrontal spikes; independent right frontal spikes; bilaterally synchronous frontal sharp waves | Multifocal spikes, left central and frontal; bifrontal | |

| PS | 8 | 32 | m | SPS with right arm clonic activity | MRI: mild cerebellar atrophy, otherwise normal; SPECT: hot spot in left frontal lobe in raw data but subtraction SPECT not confirmatory | Occasional left frontal/central sharp waves in sleep | Left frontal/central sharp waves; cluster of three spikes seen in left mid frontal lobe | |

| PS | 9 | 39 | m | SPS with left hand tingling; CPS with ‘zoning out’; drop attacks | MRI: focal area of cortical dysplasia in the right posterior perisylvan region | Right temporal and central polyspike and slow wave complexes; increased beta activity diffusely | Spikes and polyspikes in the right midtemporal region and the posterior perisylvian region (adjacent to malformation) | |

| PS | 12 | 40 | m | CPS with staring and sweating | MRI: small mesial frontoparietal cavernous malformation with associated developmental venous anomaly; some mild T2 hypointensity in left frontal-parietal white matter consistent with venous ischemia | Ictal onset: left temporal | Left frontocentral sharp and slow waves; left central-temporal slowing | Left parietal spikes |

| PS | 13 | 23 | f | SPS with fear, gripping sensation in chest; CPS with left hand posturing | MRI: possible cortical dysplasia in left superior frontal region | Ictal onset: poorly localized but on occasion preceded by right frontal sharp waves | F3 sharp waves | Sharp waves from left frontal perisylvian regions |

| PS | 14 | 32 | f | SPS with anxiety loneliness, CPS with mumbling and neck posturing; history of childhood meningitis with residual left hemiparesis | MRI: high T2 signal in right insular region, mild enlargement of the temporal horn of right lateral ventricle and mildly diminished size of right hippocampus | Ictal onset: Right anterior to mid temporal; interictal: right temporal spikes | F8 spikes and sharp transients | Spikes from right inferior frontal lobe |

| PS | 17 | 18 | m | Intractable seizures | MRI: abnormal thickening and coarsening of gyri on right with shallow right Sylvian fissure | Profuse runs spike and slow waves right hemisphere | Right hemisphere spikes | |

| PS | 19 | 40 | m | SPS with clonic activity of left face and neck; known right frontal glioma status post 2 resections | MRI: right frontal mass lesion extending from cortical surface to ventricular margin; adjacent cystic cavity | Ictal onset: right central | Right central slowing and breach rhythm; C4 sharp and slow waves | Spikes at posterior edge of frontocentral lesion |

| PS | 22 | 16 | m | CPS; history of head trauma | MRI: right mesial temporal sclerosis; right posterior frontal and parietal encephalomalacia | Ictal onset: right hemisphere | F4>T4 spikes and sharp waves; slowing on right; asymmetric spindles (seen better on left than on right) | Multifocal right hemisphere spikes plotted to right insula (not to hippocampus) |

| PS | 23 | 15 | f | CPS with left head turn then asymmetric tonic posturing and left sided clonic activity; choroid plexus papilloma resected in early childhood | MRI: large right posterior quadrant resection cavity | Ictal onset: right posterior temporal | Bursts and runs of polyspike and slow wave discharges broadly over F4-C4-P4 and also T6>T4; several brief seizures from same area | Spikes surrounding cavity |

| PS | 25 | 6 | m | Autism; possible Landau Kleffner variant | MRI: one study showed right parietal patchy subcortical lesion not seen on recent study | Profuse right frontocentral spike and slow wave discharges with frequent secondary bilateral synchrony; more recently EEG only mildly slow | C4 sharp wave | Right frontal sharp wave near posterior sylvian fissure |

| PS | 26 | 16 | m | CPS with right head turn and right arm extension | MRI: abnormally oriented right parietal sulcus with possible thickening of cortex and blurring of gray-white junction | Ictal onset: bursts of rhythmic activity in right parasagittal region (C4-P4); interictal: C4-P4 maximum sharp waves and bursts of low voltage fast activity | Profuse runs of right centroparietal spike and slow and polyspike and slow wave runs; right hemisphere slowing | Frequent spikes seen in right parietal region near lesion on MRI, seen individually or in 2- to 3-second trains |

| WH | 37 | 8 | f | Epilepsia partialis continua of right leg progressing to right arm | MRI: normal | Continuous left frontocentral epileptiform activity | Profuse spiking left frontocentral region | Continuous central spikes near left toe region on somatosensory mapping; excellent dipole cluster |

| WH | 38 | 12 | m | Intractable nocturnal tonic seizures | MRI and PET normal | Interictal spikes left centrotemporal; ictal poorly localizing but suggestive of left central onset | Bursts of left central spikes/polyspikes phase reversing at C3/P3 | Left parietal spikes |

| WH | 39 | 39 | f | Intractable complex partial seizures | MRI: normal; PET with left temporal hypometabolism | Left temporal ictal onset | In sleep, frequent spikes with a broad field but phase reversing at F7 | Left temporal spikes with broad field |

| WH | 40 | 38 | f | Intractable complex partial seizures | MRI: right mesial temporal sclerosis | Interictal: frequent left anterior temporal spikes; 2 seizures with left temporal onset and two with poorly lateralized onset | Irregular slowing over left temporal region; spikes maximal at F7 | Left temporal spikes |

| WH | 42 | m | Refractory absence and generalized tonic-clonic seizures thought consistent with inherited generalized epilepsy | MRI: left MTS; PET: left posterior mesial temporal hypometabolism, small area of hypometabolism left occipito-parietal | None; past EEGs have shown bursts of generalized spike and slow wave | Left anterior temporal sharp waves | Left anterior temporal spikes | |

| WH | 43 | 46 | m | Intractable CPS status post radiosurgery of right frontal AVM with no change in seizures | MRI: AVM inferior to head of right caudate | Ictal onset: diffuse right hemisphere changes maximal over right frontal and temporal regions | Occasional broad sharp waves seen over right hemisphere, maximal at F8; independent left hemisphere spikes maximal at F7; independent spikes seen at FP1 and less frequently FP2 | Bilateral independent and simultaneous right and left frontal and right and left temporal spikes |

| WH | 44 | 6 | f | Landau Kleffner syndrome | MRI: normal | Frequent independent bitemporal spikes, with broader field over the right, and phase reversal at C3-T3 over the left | Bilateral perisylvian spikes | |

| WH | 51 | 54 | m | Intractable CPS | MRI: left MTS | Ictal onset left temporal | Rare left hemisphere spikes with a broad field and phase reversal at F7 | Left anterior temporal spikes |

| WH | 52 | 33 | f | Intractable CPS | MRI: right MTS | Ictal onset: right temporal | Irregular slowing over right frontotemporal region; spikes isopotential at F8-T4 | Right temporal spikes |

| WH | 53 | 21 | m | Intractable CPS | MRI: normal except for Rathke’s cleft cyst | Two seizures nonlocalizing and one with left frontocentral onset; interictal frequent generalized polyspike and slow wave discharges and multifocal spikes with left central predominance (F3-C3) | Left frontal sharp waves and spikes; generalized spike and slow waves left maximal | Generalized spike and slow wave complexes maximal on left with poor dipole fits; left frontal spikes with good dipoles |

| WH | 56 | 5 | m | Congenital right middle cerebral artery stroke and intractable complex partial seizures | MRI: large area of encephalomalacia involving the right temporal, frontal, and parietal regions | Interictal: prominent irregular slowing and frequent, sleep activated, interictal spike discharges from the right occipital area; no seizures captured | Obliteration of normal posterior basic rhythm on the right, with a suppressed background over the right posterior quadrant with very frequent bursts of high-voltage polyfrequency activity and spikes from that region | Spikes medial and lateral to the occipital horn of the right lateral ventricle |

PS, Paired-sensor; WH, whole-head; SPS, simple partial seizures; CPS, complex partial seizures.

TABLE 2F.

Type IIC Cases (E+/M+ No Overlap)

| Type of Study | Case No. | Age | Sex | Seizure Type/Risk Factors | Neuroimaging | Video-EEG (scalp) | EEG | MEG/MSI | Type of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | 35 | 32 | f | CPS with head turn to left | MRI and PET normal | P3 sharp wave | Spikes localizing to posterior right parietal gray-white junction | Discordant E+/M+ no overlap |

CPS, Complex partial seizures.

RESULTS

First-pass concordance ratings are summarized in Table 1. Note that for three scans, there was artifact in the MEG recording, the EEG recording, or both such that concordance between the two methods could not be obtained. These cases are not included in the totals in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

First-Pass Concordance Ratings

| Rating | Number and Percent of Cases (paired-sensor) | Number and Percent of Cases (whole-head) | Number and Percent of Cases (both scanners) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IA. Concordant E+/M+ | 17 (52%) | 11 (50%) | 28 (51%) |

| IB. Concordant E−/M− | 3 (9%) | 5 (23%) | 8 (15%) |

| IC. Concordant E+/M+ overlap | 7 (21%) | 4 (18%) | 11 (20%) |

| Total concordant | 27 (82%) | 20 (91%) | 47 (85%) |

| IIA. Discordant E+/M− | 4 (12%) | 2 (9%) | 6 (11%) |

| IIB. Discordant E−/M+ | 1 (3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| IIC. Discordant E+/M+ no overlap | 1 (3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Total discordant | 6 (18%) | 2 (9%) | 8 (15%) |

| Total analyzed | 33 | 22 | 55 |

Note that columnar percentages may not add to 100% because of rounding.

-

I

Concordant studies: In 27 of the 33 analyzed paired-sensor cases (82%), and 20 of the 22 analyzed whole-head cases (91%), the EEG and MEG findings were concordant.

-

IA

E+/M+: Table 2a: for 28 cases, there was agreement as to the lobe(s) involved.

-

IB

E−/M−: Table 2b: for eight cases, no clearly epileptiform abnormalities were seen on either modality.

-

IC

E+/M+ overlap: Table 2c: for 11 cases, EEG and MEG identified the same lobe but one modality might indicate an additional focus. In two of these (cases 10 and 41), EEG showed a bilateral pattern that MEG suggested was secondary bilateral synchrony, and in three EEG had bilateral findings (bitemporal in case 49, bioccipital in cases 15 and 48) that on MEG appeared to arise from a unilateral focus. In four cases (cases 16, 21, 30, and 54) MEG findings overlapped EEG findings and MSI results were able to better define the epileptiform discharges relative to a structural lesion that in one case (case 16) was large and probably caused misleading EEG localization due to volume conduction. In one recording (case 32) made during multifocal status epilepticus, there was EEG evidence of ongoing multifocal seizures. MEG showed ongoing multifocal spikes corresponding to EEG, but when these spikes were selected, only those arising from the right frontocentral region could be modeled as arising a single equivalent current dipole with acceptably low error.

-

II

Discordant studies: In 6 of the 33 analyzed paired-sensor cases (18%) and 2 of the 22 analyzed whole-head cases (9%), the EEG and MEG findings were discordant.

-

IIA

E+/M−: Table 2d: In five cases, EEG showed focal epileptiform discharges not apparent using MEG alone; in a sixth case (case 31), a corresponding potential abnormality (regional low voltage fast activity versus. muscle artifact) was visible on MEG, but there were no MEG spikes that met criteria for source modeling.

-

IIB

E−/M+: Table 2e: In one case (case 33), MEG detected spikes that were apparent only as a sharp transient or a wicket spike rather than as a clear epileptiform discharge on EEG (in this case MEG agreed with ictal onset from scalp telemetry and with PET result).

-

IIC

E+/M+ no overlap: Table 2f: In one paired-sensor case (case 35), there was a weak EEG finding (single sharp wave), whereas MEG found clear spikes that localized on MSI to a lesion in the other hemisphere.

TABLE 2B.

Type IB cases (E−/M−)

| Type of Study | Case No. | Age | Sex | Seizure Type/Risk Factors | Neuroimaging | Video-EEG (scalp) | EEG | MEG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | 1 | 51 | m | SPS with left sided clonic activity; known right frontal oligodendroglioma | MRI: high to mid right frontal convexity mass without enhancement | Left central-parietal breech | No spikes | |

| PS | 11 | 44 | m | SPS with right leg weakness, involuntary right arm movement, blinking | MRI: cortical dysplasia extending to the left ventricular surface of the posterior left frontal lobe | Right temporal wicket | No spikes | |

| PS | 24 | 45 | f | CPS with altered awareness, staring, lip smacking, dysphasia | MRI: large area of remote hemorrhage and hemosiderin staining within left posterior temp lobe | Ictal onset: left temporal | Left temporal breach | No spikes |

| WH | 36 | 9 mo | m | Intractable seizures and mild delay | MRI: hypothalamic hamartoma | Ictal EEG normal | Normal | No spikes |

| WH | 45 | 28 | m | Intractable complex partial seizures | MRI: increased signal intensity in the posterior body and tail of the left hippocampus | Ictal onset left posterior temporal region | Normal | No spikes |

| WH | 46 | 31 | f | Intractable complex partial seizures | MRI: normal | Ictal onset left posterior temporal region | Normal | No spikes |

| WH | 55 | 19 | m | Intractable SPS with rocking | Normal | Ictal onset with diffuse slowing | Normal | No spikes |

| WH | 57 | 46 | f | Intractable CPS | MRI: normal except for mild cerebellar atrophy; PET: normal | Interictal: right frontal spikes and independent bitemporal spikes L = R; ictal pattern nonlateralizing | Normal | No spikes |

PS, Paired-sensor; WH, whole-head; SPS, simple partial seizures; CPS, complex partial seizures.

TABLE 2C.

Type IC Cases (E+/M+ Overlap)

| Type of Study | Case No. | Age | Sex | Seizure Type/Risk Factors | Neuroimaging | Video-EEG (scalp) | EEG | MEG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | 21 | 18 mo | m | SPS with left head and eye deviation, left arm tonic posturing; history of perinatal intraparenchymal hemorrhage of right temporal lobe | MRI: extensive post-hemorrhagic periventricular leukomalacia of the right hemisphere; PET: large defect in corresponding area | Ictal onset: right hemisphere (broad) | Right hemispheric slowing and loss of detail maximal in the posterior quadrant; right posterior quadrant spikes; bursts of more generalized polyspike-and-slow-wave discharges bilateral frontocentral | Frequent spikes seen anteriomedially, posterior and superior to area of T2 prolongation within right temporal lobe as well as in white matter adjacent to right lateral ventricular horn |

| PS | 7 | 7 | f | Landau Kleffner syndrome | MRI: left inferior temporal cortical dysplasia | Continuous spike and slow wave in sleep with a dipole oriented parasagittal negative/temporal positive; at times unilateral discharges seen more frequently on the right; no distinct seizures | Broad bilateral spike and slow waves without clear laterality; independent right and left midtemporal discharges | Generalized spike and slow wave but higher amplitude and lead on left |

| PS | 10 | 13 | f | SPS of ‘turning’ and clonic movements of left arm | MRI: slight asymmetrical enlargement of right choroidal fissure, likely a small arachnoid cyst | Occasional bursts of 3- to 4- Hertz spike-wave, broadly distributed but with a right frontal maximum | Occasional right frontal spikes | |

| PS | 15 | 2 | f | Linear sebaceous nevus syndrome and infantile spasms | MRI: giant perivascular spaces throughout right hemisphere; smaller right hemisphere; MR spectroscopy: right posterior parieto-occipital focus; PET: diffuse hypo-metabolism of right hemisphere with relative sparing of frontal lobe and basal ganglia | Ictal onset: generalized electro-decremental | Multifocal spikes arising independently from left and right posterior quadrants; generalized spike and slow wave discharges in sleep | Spikes in right posterior parietal and occipital region |

| PS | 16 | 32 | F | Intractable CPS | MRI: dysplasia of left hippocampus and amygdala; bilateral periventricular heterotopic gray matter; large schizencephalic cyst replacing posterior left frontal lobe, left parietal lobe, and posterior left temporal lobe | Bilateral occipital spikes, both synchronous and independent, left > right; bilateral independent anterior temporal spikes | Bilateral independent temporal spikes; left temporal spikes localize to middle cranial fossa on rim of large cyst | |

| PS | 30 | 25 | f | SPS/CPS with drooling, abdominal sensations, left hand weakness | MRI: cortical dysplasia in right perirolandic region | Ictal onset: generalized, nonlateralized; interictal: generalized spikes with right hemispheric emphasis but also rare independent hemispheric discharges | Polyspike and slow waves seen bilaterally and independently in right and left midtemporal regions, right slightly more frequently | Clear left hemisphere spikes seen on MEG did not meet criteria for analysis; independent right hemisphere spikes and generalized spikes mapped to right parietal cortical dysplasia, to the medial right temporal lobe (mid and posterior), to the right hippocampus, and to the right parahippocampal gyrus |

| PS | 32 | 10 | m | Prolonged status epilepticus following encephalitis of unknown etiology | MRI: progressive atrophy and increased T2 signal in both hippocampi | Ongoing multifocal seizures | Multifocal seizures arising independently and sequentially from the right frontal, left frontal, right posterior quadrant | Frequent multifocal spikes throughout recording, but only one group of right frontocentral spikes could be modeled with low error |

| PS | 34 | 11 | f | SPS/CPS with left sided clonic jerks; Rasmussen encephalitis | MRI: progressive atrophic changes and white matter loss in right frontal regions | V-waves skewed to left; single sharp wave left parasagittal | Multifocal independent spikes in bilateral central-parietal regions | |

| WH | 41 | 7 | f | Intractable symptomatic localization related epilepsy | MRI: focal cortical dysplasia of right frontal region; PET: normal | Outside VET: generalized and bifrontal spike and wave discharges, maximal on the right | Profuse bifrontal spikes and polyspikes occurring singly, in bursts, and in prolonged runs; higher amplitude on right than on left | Bursts of moderate to high voltage spike activity bifrontal with right frontal predominance; dipoles clustered in right superior middle frontal gyri as well as anterior aspect of Sylvian fissure |

| WH | 48 | 3 | m | Language regression | MRI: 5 mm heterotopic focus of gray matter next to the trigone of left lateral ventricle; possible tiny area of heterotopic gray matter next to posterior horn of right lateral ventricle | Frequent high voltage independent bilateral occipital spikes, higher in amplitude on the right | Right occipital spikes | |

| WH | 49 | 20 | m | Intractable CPS | MRI: left MTS | Ictal onset: bursts of high amplitude, sharply contoured activity over right and left temporal regions | Independent bitemporal sharp waves often followed by a burst of high voltage rhythmic theta | Left temporal spikes |

| WH | 54 | 39 | f | Intractable CPS status post resection of left temporal AVM | MRI: resection cavity | Ictal onset independently from left and right temporal regions | Frequent T3 spikes; left temporal breech | Independent spikes in the bilateral mesial and lateral temporal lobes, bilateral insula, and anterior to the resection cavity in the left frontotemporal region |

PS, Paired-sensor; WH, whole-head; SPS, simple partial seizures; CPS, complex partial seizures.

TABLE 2D.

Type IIA Cases (E+/M−)

| Type of Study | Case No. | Age | Sex | Seizure Type/Risk Factors | Neuroimaging | Video-EEG (scalp) | EEG | MEG/MSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | 20 | 17 | f | CPS | MRI normal | No clear EEG correlate | Single sharp and slow wave at F3 | No spikes |

| PS | 28 | 26 | f | SPS/CPS with “ticking” in left face followed by right eye deviation, loss of vision, emesis | MRI normal; SISCOM: left posterior quadrant focus | Ictal onset: left posterior quadrant | T5 sharp waves in sleep | No spikes |

| PS | 29 | 30 | m | CPS with prominent salivation | MRI: bilateral, symmetric, diffuse subtle T2 hyperintensity of the white matter consistent with toxic or metabolic disease; PET: left temporal hypometabolism | Ictal onset: left frontal; interictal: left temporal spikes | Single broad left hemisphere spike; single T3 sharp wave | No spikes |

| PS | 31 | 10 | f | SPS with inability to move | MRI: Left posterior temporal periventricular heterotopia | High frequency low voltage activity in left temporal region | No spikes | |

| WH | 50 | 21 | f | Intractable CPS | MRI: abnormal left hippocampal head and anterior body | Interictal generalized spike-wave discharges skewed towards the left; ictal onset nonlocalizing | Single T3 sharp wave | No spikes |

| WH | 58 | f | Meningoencephalitis and intractable complex partial seizures | MRI: Left frontal encephalomalacia and left MTS; PET: nonlocalizing | Interictal: bitemporal spikes; ictal pattern nonlateralizing | Rare right temporal sharp waves | No spikes |

SPS = simple partial seizures, CPS = complex partial seizures.

TABLE 2E.

Type IIB Cases (E−/M+)

| Type of Study | Case No. | Age | Sex | Seizure Type/Risk Factors | Neuroimaging | Video-EEG (scalp) | EEG | MEG/MSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | 33 | 25 | f | SPS with fear, garbled speech, clonic movement of right arm | MRI: normal (no surface coil); PET with reduced uptake left thalamus compared with right | Ictal onset: left temporal | Left frontocentral sharp transients; burst of left wicket rhythm | Left posterior temporal sharp and slow waves |

SPS, Simple partial seizures.

Unblinded second-pass analysis was then done using clinical data and side-to-side comparisons of the datasets.

Representative Cases

Here, we present cases from each category (except for the E−/M− category) along with illustrative figures for six of the cases.

IA. Concordant, E+/M+

Case 17

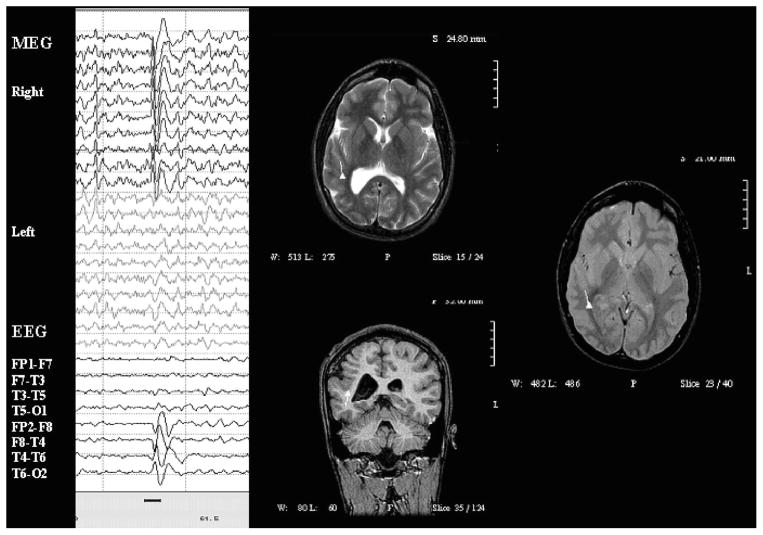

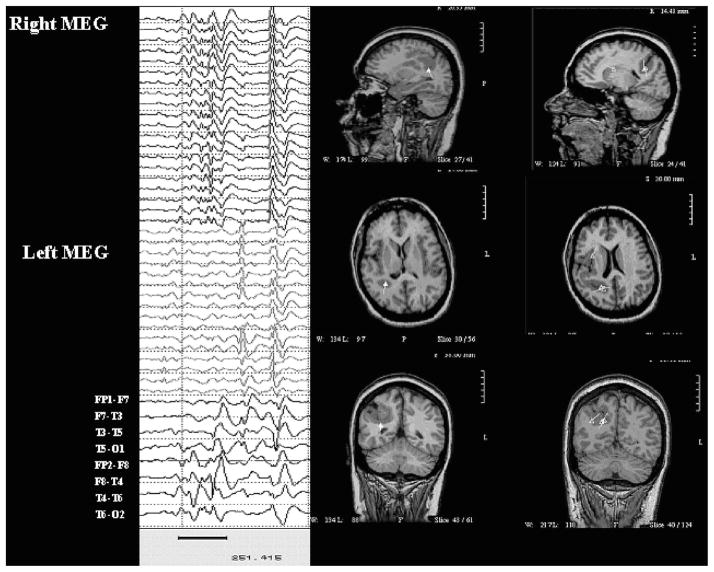

Case 17 was an 18-year-old man with cortical dysplasia and symptomatic intractable complex partial seizures. MRI shows abnormal thickening and coarsening of gyri of the right hemisphere with a shallow right Sylvian fissure. EEG showed profuse runs of spike and slow wave discharges maximal at T4 > C4. Paired-sensor MEG showed spikes in the right temporal and central region. On MSI, the MEG spikes localized, clearly and consistently, to the deep cortex in the inferior aspect of the dysplasia. See Fig. 1.

FIGURE 1.

Paired-sensor MEG, simultaneous scalp EEG, and MSI for case 17. Dipoles in this and following figures are shown as triangles with vector tails indicating orientation and strength (proportional to length).

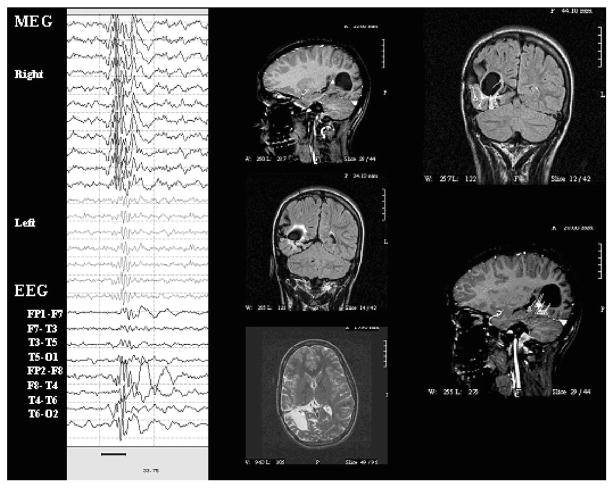

Case 23

Case 23 was a 15-year-old girl with choroid plexus papilloma resection in infancy, now with intractable complex partial seizures with left head turn followed by asymmetric tonic posturing and left sided clonic activity. MRI showed large area of cystic encephalomalacia in the right posterior quadrant. In the past, long-term video-EEG monitoring showed ictal onset from the posterior left temporal region.

EEG showed bursts and runs of polyspike and slow wave discharges from right central regions and from right posterior temporal regions, along with several brief subclinical seizures from the same area. Paired-sensor MEG showed spikes from the same region. On MSI, these mapped to the rim of the encephalomalacia, including the deep rim. Subsequent extraoperative ECoG with a grid of subdural electrodes placed over the posterior quadrant and across the mouth of the cyst showed onset around the mouth of the cyst but could not document seizure propagation, perhaps because the seizure spread to involve the deep rim of the cyst in a manner that could not be recorded by subdural electrodes. After extensive excision of these regions, including the deep sources only revealed by MSI, she was seizure-free. See Fig. 2.

FIGURE 2.

Paired-sensor MEG, simultaneous scalp EEG, and MSI for case 23.

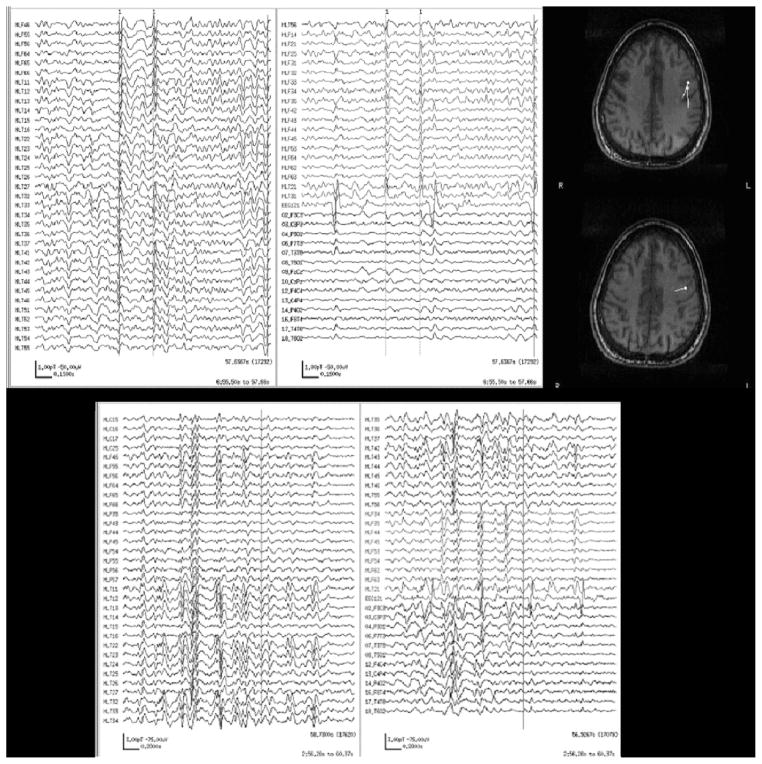

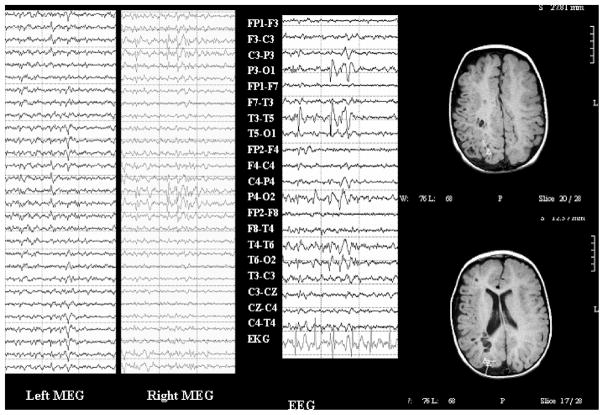

Case 53

Case was a 21-year-old man with intractable complex partial seizures. MRI was normal except for a Rathke’s cleft cyst. Interictal EEG in the past showed generalized spike and slow wave discharges. Ictal scalp recordings were either nonlocalizing or showed left frontal/frontocentral onset. EEG showed left frontal sharp waves on EEG that were better seen on whole-head MEG and had excellent dipole fits. He also had more generalized bursts on EEG and MEG that could not be reliably modeled for MSI. See Fig. 3.

FIGURE 3.

Whole-head MEG, EEG, and MSI for case 53. Top panel: Left frontal and temporal MEG channels (left column and top of right column), ECG, and EEG (bottom of right column) for left frontal spikes (marked with gray dashed vertical cursors) along with MSI showing left frontal dipoles. Bottom panel: Left frontal and temporal MEG channels, ECG, and EEG for generalized spike and slow wave bursts that could not be reliably modeled for MSI.

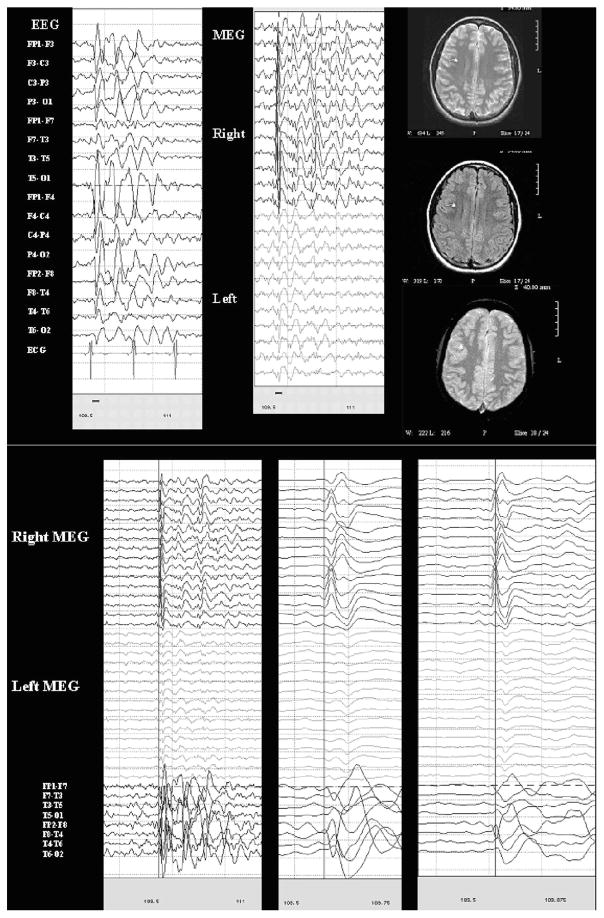

IC. Concordant E+/M+ Overlap

Case 10

Case 10 was a 13-year-old girl with simple partial seizures involving the sensation of “turning” followed by motor features involving the left arm. MRI was normal except for a slight enlargement of the right choroidal fissure consistent with a small arachnoid cyst. EEG demonstrated 3 to 4 Hz spike and slow wave complexes with a maximum/lead from the right frontal region (F4) and significant secondary bilateral synchrony as well as rare spike and slow wave complexes only seen at Fp2-F4. Paired-sensor MEG showed spikes in the same regions. On MSI, these were clearly shown to have a single right frontal source. The MSI thus strengthens the impression of secondary bilateral synchrony and helped to identify the source more precisely, aiding presurgical decision making. See Fig. 4.

FIGURE 4.

Paired-sensor MEG and simultaneous scalp EEG and MSI for case 10; the same epoch of MEG and EEG (limited to bilateral temporal longitudinal bipolar montage) is shown at normal (left) and increasingly expanded time scales (marked with blue cursor to show lead/lag).

Case 30

Case 30 was a 25-year-old woman with symptomatic partial seizures since age 8, consisting of drooling, abdominal sensations, and left hand weakness. MRI showed cortical dysplasia in the right perirolandic region. Prior long-term video-EEG monitoring showed ictal onset that appeared to be generalized and nonlateralizing, whereas interictal discharges were usually generalized with a right-hemispheric emphasis, but there were also rare bihemispheric independent discharges. EEG showed bilateral independent polyspike and slow wave complexes arising from temporal regions, right (T4/T6) more frequent than left (T3/T5). Paired-sensor MEG showed frequent bilateral independent discharges, but only the right hemispheric spikes met analysis criteria, so the results were rated as E+/M+ overlap rather than fully matched. However, on MSI, when the spikes meeting criteria were modeled, they localized to regions surrounding the area of cortical dysplasia. Thus, although EEG and MEG results were only overlapping, MSI was more consistent with the imaging abnormality and thus helped add weight to the dysplasia as the source of seizures. See Fig. 5.

FIGURE 5.

Paired-sensor MEG, simultaneous scalp EEG, and MSI for case 30.

Case 15

Case 15 was a 2.5-year-old girl with linear sebaceous nevus syndrome and infantile spasms. MRI showed a smaller right hemisphere with enlarged perivascular spaces. Prior MR spectroscopy and PET suggested metabolic abnormalities of the right posterior quadrant. EEG showed multifocal spikes arising independent from left and right posterior quadrants; generalized spike and slow wave discharges in sleep, whereas paired-sensor MEG suggested that these were from the right posterior regions. MSI showed dipoles localizing to the posterior parietal-occipital regions of the right hemisphere. Thus, although EEG and MEG results could be rated as concordant, E+/M+ overlap, we saw on second-pass analysis that MEG suggested a unilateral source in a region that was abnormal by multiple imaging methods. Thus, as for the previous case (case 30), although EEG and MEG results were only overlapping, MSI was more consistent with the imaging abnormality. See Fig. 6.

FIGURE 6.

Paired-sensor MEG, simultaneous scalp EEG, and MSI for case 15.

IIA. Discordant E+/M−

Case 30

Case 30 was a 10-year-old girl with simple partial seizures during which she felt unable to move. MRI showed a heterotopia lateral to the temporal horn of the left lateral ventricle. EEG showed focal low-voltage, high-frequency activity (versus focal muscle artifact) in the left posterior temporal derivations. Paired-sensor MEG showed low-voltage, high-frequency activity in the same area. Because the source of this activity could not be modeled as described above, this case was rated as M−. However, both datasets did show the regional abnormality that corresponded to the MRI lesion. The first pass rating of E+/M− did not capture the fact that the datasets agreed, although dipoles could not be modeled for MEG and would not have been able to be modeled for EEG had we attempted to do so.

IIB. Discordant E−/M+

Case 33

Case 33 was a 25-year-old woman with simple partial seizures consisting of fear, garbled speech, and clonic movements of the right arm. MRI (without surface coil) was normal; PET showed reduced uptake in the left thalamus compared with the right. Previous long-term video-EEG monitoring showed ictal onset from the right temporal lobe. EEG showed sharp transients (but not sharp waves or spikes) in the left frontocentral region and a single burst of left temporal wicket rhythm. Paired-sensor MEG showed sharp and slow waves that mapped to the left posterior temporal region on MSI.

IIC. Discordant E+/M+ No Overlap

Case 35

Case 35 was a 32-year-old woman with complex partial and secondarily generalized seizures. MRI and PET were normal. EEG showed a single sharp wave phase-reversing at P3. Paired-sensor MEG showed spikes maximal in the right parietal region that on MSI map to the right posterior parietal gray-white junction.

The cases in categories IA and IC (pictured in the figures) are examples of cases that on secondary unblinded analysis, using both datasets, yielded richer information when the EEG and MEG/MSI datasets were combined. They illustrate that the use of both datasets together can be complementary and that this characteristic of the data was not conveyed adequately by labeling the cases as “concordant” or “discordant.” For example, MEG/MSI could clarify the relation of a particular EEG pattern to a structural lesion, or, as mentioned above, might offer support for an apparently generalized EEG pattern being the result of secondary bilateral synchrony from a single focus.

DISCUSSION

In this series of heterogeneous patients with epilepsy, MEG and EEG results were most often concordant in a first-pass analysis. Concordance was higher for the whole-head system, in line with a previous report that concordance may be higher when more sensors are used (Stefan et al., 2003). In some of the cases in which concordance was not absolute but in which the results of the two methods overlapped, the different results may have been related to the presence of a large lesion that distorted cortical anatomy and made EEG localization difficult (using visual analysis only), whereas the relation between the lesion and MSI dipoles was often very useful. In one case, MEG revealed spikes that were not clearly epileptiform on routine low-density scalp EEG with visual analysis alone; this superiority may be due to the MEG’s theoretically superior spatial resolution.

Sometimes when EEG revealed focal epileptiform abnormalities and MEG did not, this discordance was attributable to the different criteria used for judging EEG and MEG: That is, abnormalities seen on EEG may have also been apparent on MEG, but not as spikes that could be used for convincing source models. This is supported by a pattern that we noticed: there were six times as many EEG+/MEG− cases as there were EEG−/MEG+ cases, and this discrepancy may be an artifact of the fact that only spikes meeting certain criteria could render a case “MEG+,” whereas the significance of other MEG patterns is not yet fully known. Choosing MEG spikes arbitrarily, based on criteria developed for EEG spikes, and failing to attend to other features of the MEG record is limiting. The neurophysiology community should pursue the development of a validated dictionary for visual analysis, presenting EEG patterns with corresponding MEG patterns found in the same patients. Techniques for modeling the sources of “patchy” or regional MEG features (such as focal slowing or focal low-voltage fast activity), though computationally intensive, should be pursued.

In addition, common analysis techniques only allow MEG spikes that can be modeled as single stationary dipoles, so that solutions are computationally tractable, but this limitation forces us to accept limited solutions that do not reflect the true source of epileptiform activity. As was pointed out in a recent editorial (Lesser, 2004), we lack an understanding of how EEG and MEG spikes are related in terms of morphology, specificity, usefulness, and relation to underlying pathophysiology. For now, performing simultaneous EEG with MEG should be considered routinely to gain this experience; as pointed out by several groups cited above, EEG spikes can also be used to find MEG spikes by, for example, averaging techniques (e.g., Rodin et al., 2004; Yoshinaga et al., 2002), thereby maximizing the sensitivity of a study.

Our second-pass unblinded analysis suggested that simple division of results of these two technologies into “concordant” and “discordant” fails to capture the richness of the data gathered. In some cases in which MEG spikes were concordant with EEG focality on first pass, it was able to go beyond EEG, though the use of source modeling and MSI, adding significant value to the clinical picture. In “discordant” cases, often examination of the discordance itself pointed to a factor that was important to understanding the case—in other words, the discordance was not random but made sense within the context of the entire dataset. Often, the two datasets were synergistic, providing information that enriched and disambiguated the clinical scenario beyond expectations of the terms “concordant” or “discordant.” For example, EEG might show bilaterally synchronous occipital spikes that are only seen unilaterally on MEG and whose dipoles localize to a unilateral posterior quadrant lesion on MSI. In such a case, although first-pass analysis indicated that the results of the two studies are not perfectly concordant, it was clear on unblinded review of the dataset that the results are consistent with the underlying pathology as viewed through the lenses of different techniques.

In fact, careful examination of both datasets, moving between them and integrating them with MRI images, allowed a deeper appreciation of the nature and source of epileptiform activity. In some cases, this appreciation meant that a patient could be considered for epilepsy surgery, or at least for invasive monitoring, because the MEG had been performed. In the cases in which MEG confirmed secondary bilateral synchrony (such cases have also been reported by Tanaka et al., 2005), this helped target ECoG; when MEG suggested that epileptiform activity localized to an edge of a large lesion, this could either guide the placement of chronic intracranial electrodes or allow for lesionectomy with intra-operative ECoG. In some cases, such as case 23 (Fig. 2), MEG-guided surgery directly by revealing epileptiform activity deep within a cavitary lesion that could not, therefore, be recorded using implanted electrodes. Combined computational approaches to data analysis are under development (e.g., Fuchs et al., 1998) and should help users combine datasets quantitatively and objectively in the future.

Acknowledgments

Part of this work was funded by NIH DC004855 to S.S.N. and by K23 NS047100 to H.E.K.

References

- Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia. 1989;30:389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley GL, Baumgartner C. MEG and EEG in epilepsy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;20:163–178. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bast T, Ramantani G, Boppel T, et al. Source analysis of interictal spikes in polymicrogyria: loss of relevant cortical fissures requires simultaneous EEG to avoid MEG misinterpretation. Neuroimage. 2005;25:1232–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner C. Controversies in clinical neurophysiology: MEG is superior to EEG in the localization of interictal epileptiform activity: con. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:1010–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs M, Wagner M, Wischmann HA, et al. Improving source reconstructions by combining bioelectric and biomagnetic data. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;107:93–111. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(98)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan RW, Herman J, Purdy P. Cerebral location of international 10 –20 system electrode placement. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1987;66:376–382. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(87)90206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper HH. The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1958;10:370–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knake S, Halgren E, Shiraishi H, et al. The value of multichannel MEG and EEG in the presurgical evaluation of 70 epilepsy patients. Epilepsy Res. 2006;69:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser RP. MEG: good enough. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:995–997. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YY, Shih YH, Hsieh JC, et al. Magnetoencephalographic yield of interictal spikes in temporal lobe epilepsy: comparison with scalp EEG recordings. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1115–1126. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minassian BA, Otsubo H, Weiss S, et al. Magnetoencephalographic localization in pediatric epilepsy surgery: comparison with invasive intracranial electroencephalography. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:627–633. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199910)46:4<627::aid-ana11>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakasato N, Levesque MF, Barth DS, et al. Comparisons of MEG, EEG, and ECoG source localization in neocortical partial epilepsy in humans. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;91:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi M, Otsubo H, Kameyama S, et al. Epileptic spikes: magnetoencephalography versus simultaneous electrocorticography. Epilepsia. 2002;43:1390–1395. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.10702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin E, Funke M, Berg P, et al. Magnetoencephalographic spikes not detected by conventional electroencephalography. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:2041–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheler G, Fischer MJ, Genow A, et al. Spatial relationship of source localizations in patients with focal epilepsy: comparison of MEG and EEG with a three spherical shells and a boundary element volume conductor model. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28:315–322. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan H, Hummel C, Scheler G, et al. Magnetic brain source imaging of focal epileptic activity: a synopsis of 455 cases. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 11):2396–2405. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka N, Kamada K, Takeuchi F, et al. Magnetoencephalographic analysis of secondary bilateral synchrony. J Neuroimaging. 2005;15:89–91. doi: 10.1177/1051228404271007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaga H, Nakahori T, Ohtsuka Y, et al. Benefit of simultaneous recording of EEG and MEG in dipole localization. Epilepsia. 2002;43:924–928. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.42901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]