Abstract

Metagenomics provides a powerful new tool set for investigating evolutionary interactions with the environment. However, an absence of model-based statistical methods means that researchers are often not able to make full use of this complex information. We present a Bayesian method for inferring the phylogenetic relationship among related organisms found within metagenomic samples. Our approach exploits variation in the frequency of taxa among samples to simultaneously infer each lineage haplotype, the phylogenetic tree connecting them, and their frequency within each sample. Applications of the algorithm to simulated data show that our method can recover a substantial fraction of the phylogenetic structure even in the presence of high rates of migration among sample sites. We provide examples of the method applied to data from green sulfur bacteria recovered from an Antarctic lake, plastids from mixed Plasmodium falciparum infections, and virulent Neisseria meningitidis samples.

Keywords: metagenomics, Bayesian phylogenetics, microevolution

METAGENOMICS—purifying and sequencing DNA from environmental samples without any culturing step—represents an important new tool for investigating how microbes interact with, mold, and adapt to their environments (Tyson et al. 2004; Allen and Banfield 2005; Gill et al. 2006; Preidis and Versalovic 2009). Metagenomics can also be applied to any situation where genetic variability exists within a sample, such as microbiomes, mixed infections, and cancer. Many metagenomic analyses relate the overall DNA content of samples to environmental phenotypes (Tringe et al. 2005; Kurokawa et al. 2007). We take up a different problem: the reconstruction of organismal composition for each sample. Overall DNA content provides useful information on overall community function, but many physiological and evolutionary processes may be understood only at the organismal level (Partida-Martinez and Hertweck 2005; Martinez et al. 2009).

Recent improvements in sequencing technology allow the collection of large numbers (>106) of short reads of DNA sequence (40–100 bp) from within a sample (Schmeisser et al. 2007; Bentley et al. 2008). For notational clarity we refer to each sample as a pool. The simplest approach to inferring composition is in terms of the frequency of known sequences within each sample (von Mering et al. 2007; Chaffron et al. 2010). This approach typically works well for assessing variation at broad scales when individual reads can be mapped onto the nearest reference genome within the tree of life (Matsen et al. 2010; Berger et al. 2011; Berger and Stamatakis 2011; Löytynoja et al. 2012). However, at finer scales, and in particular if one is interested in the evolution taking place within the samples themselves, the structure of relationships among organisms will generally not be known in advance and so must be inferred from data.

Figure 1, left, illustrates the evolutionary scenario that we assume underlies the data. The phylogeny’s tips correspond to individual cells, and color indicates the pool of origin. Since individual reads are typically short and will thus contain limited phylogenetic information, it is not feasible to reconstruct a resolved tree where each read corresponds to a single taxon. We therefore attempt to infer a simplified phylogeny in which the terminal nodes represent groups of related organisms or lineages (Figure 1, right). Each lineage defines a haplotype of allele states for the single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the data and makes up a proportion of the organisms within a pool shown by the colored bar. As indicated by the shaded cones, the SNP pattern of organisms within a lineage may vary, due to recent, low-frequency variation or sequencing errors.

Figure 1.

A diagram of the lineage model. On the left, a coalescent process leads to a complete genealogy, with the tips marked by pool as colors. The right diagrams the lineage model approximation, showing deep branching events together with cones shading the SNP variation indistinguishable from noise.

One similar—but easier—problem is phasing in diploid organisms. In this case, the goal is to reconstruct haplotypes (i.e., the sequences of the two copies of each chromosome) given the genotypes at each diploid locus. Statistical algorithms often estimate phase using the property that particular combinations of variants are present in the population at a higher frequency than expected if the variants segregated independently (Excoffier and Slatkin 1995; Stephens et al. 2001). In our case, we seek to estimate the underlying lineages and the phylogeny connecting them by using the differing frequencies of SNP allele proportions within each pool.

We focus on extracting the phylogenetic information provided by this SNP read count variation. We assume that recombination is not occurring. Our model neglects the spatial information about the co-occurrence of neighboring SNPs observed on a single read or paired-end reads. This means that we discard potentially valuable linkage data that provide strong information about haplotype structure. Other algorithms have been developed that specifically seek to utilize these data (Greenspan and Geiger 2004), and we briefly detail the prospects for improvements that exploit both variation between pools and the information from linked SNPs in the Discussion.

Data and Methods

Model

Our model is primarily a phylogenetic one and so borrows a lot of its structure from established methods (Mau et al. 1999; Felsenstein 2004; Drummond et al. 2005). However, our data are distinct from standard phylogenetic contexts since individual metagenomic reads cannot be identified with an observable taxon. To deal with this absence, we assume that the reads arise from unobserved haplotypes—the lineages—with variation appearing either from mutations along a phylogenetic tree or from errors in sequencing, informatics, or SNP calling. We take each pool to be a mixture of K lineages and employ a Bayesian approach to jointly estimate the lineages, mixture proportions, and phylogeny from the SNP read count data. Since the number of lineages is not known a priori, we employ an empirical Bayes factor analysis to infer K (Newton and Raftery 1994; Kass and Raftery 1995).

We assume that short-read sequence data are collected from N pools, indexed by i = 1, … , N. Pools may be the result of differing collection times, spatial locations, or other experimental distinctions. From the full set of sequence reads, we infer a set of M SNPs, indexed by j = 1, … , M. This may be done by using mapping reads to a reference genome (Li and Durbin 2009) or by employing de novo approaches (Zerbino and Birney 2008; Iqbal et al. 2012). We suppose that SNPs are biallelic and that counts, d, are made for each SNP in each allele state within each pool. The full data set comprises = [dijs], where i = 1, … , N, j = 1, … , M, and s ∈ {0,1}. Arbitrarily, we assign s = 0 to be the reference allele state. Finally, we assume that the pools constitute independent samples from each other and that the mutations are independent for each site conditional upon the tree. The independence assumptions are computationally expedient but may neglect some useful information. Types of nonindependence that can be expected from real data are described further in the Discussion.

Our model links two components to provide a likelihood for the SNP count data. The first component specifies the structure of SNP variation leading to a set of lineages. The second one details the proportions of lineages found in each pool, as in Figure 1. We now lay out both components and show how to combine them. We conclude by detailing the full posterior decomposition based on these components and corresponding priors. Our model has a large number of parameters, so we provide a listing of their definitions in Table 1.

Table 1. Symbols used in the model description.

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| = [dijs] | Data composed of counts for each SNP j within pool i of type s ∈ {0, 1} |

| i = 1, … , N | Index and no. pools |

| j = 1, … , M | Index and no. SNPs |

| k = 1, … , K | Index and no. lineages |

| ℒ = [lkj] | Lineages composed by state of SNP j in lineage k |

| Phylogeny | |

| τ, {tb} | Topology and branch lengths for |

| T | The total branch length of |

| λ | Probability of a phylogenetic SNP |

| Phylogenetic and null SNP sets defined by | |

| Partition of SNPs into phylogenetic and null components | |

| = [sik] | Pool composition specified by pool proportion for pool i and lineage k |

| pij | The uncorrected reference allele frequency for SNP j in pool i |

| η | SNP error rate |

| The corrected reference allele frequency for SNP j in pool i | |

| ξ | Mutation rate |

| ψ | Mixing rate in the island coalescent simulations |

SNP variation:

We fix the number of lineages to be K and number them k = 1, … , K. We assume that there is a rooted coalescent tree, , specified by a topology, τ, and set of branch lengths, {tb}. By assumption, has K external taxa, and each corresponds to a lineage, ℒk, that defines a haplotype for the SNPs at that tip. We write out lineages as ℒk = [lkj], where j = 1, … , M and lkj ∈ {0, 1} specifies the state of SNP j. The collection of lineages we write as ℒ.

As we assume sites are independent, we can specify the model for a single SNP without a loss of generality. We suppose that variation in SNP state arises in one of two ways: through mutation along the genealogy or through some form of observational error. Errors may arise from a variety of sources, including sequencing errors, a poor-quality reference genome, or alignment errors. The model consequently loses some power by treating real variation present at a low frequency in the population as an error.

The model categorizes SNP positions into two classes that we label as phylogenetic and null sites. Phylogenetic SNPs arise from mutations on the reduced phylogeny. Null SNPs usually occur toward the tips of the full phylogeny from recent, low-frequency variants. Null SNPs may also appear from informatic errors. These SNPs are not included in the phylogenetic likelihood. Of course, phylogenetic SNPs can also be subject to errors, but they are not the sole cause of their appearance in the data. We assume that the type of SNP variation at a site occurs as a Bernoulli trial with a parameter λ setting the probability of being a phylogenetic SNP. This naturally partitions the count data, , into a phylogenetic component, and a null component, We refer to this partition by . We assume the prior for λ does not depend on the other parameters, although this ignores some dependence on K and the error rate that is likely in practice.

For each phylogenetic SNP j the allele state for each of the K tips is given by ℒj = [lj1, … , ljK]. In a typical phylogenetic context, ℒj would correspond to the observed sequence pattern at a single site in an alignment. Given a mutation rate, ξ, we calculate ℙ(ℒj|, ξ), using a two-state analog of Jukes and Cantor’s mutational model together with Felsenstein’s tree-pruning algorithm (Jukes and Cantor 1969; Felsenstein 1981). Each null SNP exhibits an absent pattern across the lineages, with either ℒj = [0, … , 0] or ℒj = [1, … , 1]. We assume the probability of either null pattern is

Pool proportions:

We label the specification of proportions for each lineage in each pool by . As each pool is an exclusive mixture of different lineages, it is natural to capture this structure by an N × K matrix with each entry sik giving the proportion of lineage k that is found in pool i, enforcing that for all i = 1, … , N.

Likelihood:

Supposing that the data are error free, we can relate ℒ and to the data in the following way. Summing over the lineages at each position combines the pool proportions and the SNP state to give the expected reference allele frequency for pool i and SNP j:

| (1) |

We assume that sequencing errors afflict all read counts homogeneously with probability η. Consequently, we expect only (1 − η) of the reference counts to come from reference states while η of the nonreference counts reflect genuine reference states. To account for these errors, we correct the reference allele frequency in Equation 1 by

| (2) |

As SNPs and pools are assumed to be independent, the counts within each pool for each SNP follow a binomial distribution with proportion This gives the likelihood for the data as

| (3) |

Bayesian inference:

We can now examine the full posterior decomposition to complete our model specification. Bayes’ theorem provides

Noting that is independent of all of the other variables and that, conditional upon the partition, λ does not affect the lineages, we may then collapse the right-hand side above to be

| (4) |

We first consider the conditional probability for ℒ in Equation 4.

Since sites are independent, we can decompose via whether a SNP follows the phylogenetic model or the null model,

| (5) |

where denotes the number of SNPs contained in

We now examine the joint probability in the middle of the right-hand side of Equation 4. Except the partition and the parameter λ, we note that all of the components are independent, leading to the relatively simple expression

Since a series of Bernoulli trials with parameter λ creates the partition, its probability is given by

With these components specified, we have to detail only the prior distributions, ℙ(), ℙ(), ℙ(), ℙ(ξ), ℙ(η), and ℙ(λ).

Prior specifications:

- : We assume the genetic composition of each of the pools is sampled independently from the same prior distribution. As we have the constraint that a natural prior for each pool is a uniform Dirichlet distribution of length K, following Balding and Nichols (1995). The prior distribution for is then

where 1K is a vector of ones of length K (Pritchard et al. 2000).

- : We assume a coalescent prior for . If {ui: i = 2, … , K} are the time intervals between coalescent events ordered to reflect the number of individuals present at that time, then the tree has total branch length and

The distribution for the total branch length T can be found in Tavare (1984).

ξ: This is distributed as Exp(1).

η, λ: We assume these are uniform on the open unit interval, (0, 1).

Inference

We use a Metropolis–Hastings Markov chain (MCMC) approach to inference. To infer the parameters , , ℒ, and , we employ approaches previously applied to phylogenetics (Huelsenbeck et al. 2001). To infer K we use an empirical Bayes factor procedure that integrates information across a set of MCMC runs. Conditional upon a fixed K, we now describe the parameter updates.

The Metropolis–Hastings ratio gives the probability that a proposed parameter update will be accepted from a current state x with probability α such that

The first fraction is the ratio of the posterior probability of x and and we denote this α1. The second fraction is the ratio of the probability of choosing the current state from the proposed state over the reverse move. We label this α2. Since α1 constitutes assessment of the likelihood and the prior functions that can be calculated as shown above, we subsequently consider only α2.

:

For each iteration, we propose a subtree prune and regraft (SPR) move (Felsenstein 2004). As the tree is rooted, a node is chosen uniformly among all nodes within the tree not connecting above to the root. Removing this node divides the topology τ into τp, the pruned segment, and τr, the remaining segment. We reattach τp to τr along a uniformly chosen edge within τr, with the precise location taken uniformly across the chosen edge. This generates a new tree and corresponding branch lengths We then recalculate the branch lengths to ensure a coalescent tree. Since the starting and ending states are equally probable with respect to each other, α2 = 1. To ensure the chain does not get stuck in a mode of the posterior distribution, we also propose new branch lengths by successively proposing small changes in length to each tb on a uniform interval [tb − ε, tb + ε]. For both moves the probability of proposal is the same in both directions so α2 = 1.

ℒ and :

The inference of ℒ for a given SNP j involves a simple bit-flip operation. First, a SNP j and a lineage k are selected at random and the allele state for that lineage’s SNP is flipped: lkj →|1−lkj|. Since this a deterministic operation, and the SNP and lineage are chosen uniformly, α2 = 1. It is not necessary to infer directly , since SNPs with site patterns that are uniform—where all allele states are 0 or 1—are treated as null positions, while those that are not uniform are treated as phylogenetic.

:

We update by the composition of a randomly chosen pool i. We propose a new pool by drawing from a Dirichlet distribution with parameters (γ1, … , γK) informed by ℒ such that

where β is a tuning parameter. In practice, we find β = 5 to provide good rates of move acceptance. A brief calculation shows that

η, λ, and ξ:

All these are drawn directly from the prior and so have α2 = 1.

K:

We run the MCMC for K = 2, … , 2 ⋅ N and then compare the runs using Bayes factors to find K. To infer the Bayes factor between each pair of runs, we require the marginal likelihood ℙ( | K) and estimate it by taking the harmonic mean of an importance sample from the likelihood, using the posterior density as weights, as in Kass and Raftery (1995). This estimator of the marginal likelihood is known to have poor performance in certain circumstances, although we empirically observe it to work well in the simulations below, as it has as in other phylogenetic contexts (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck 2003; Drummond and Rambaut 2007).

Simulations

Simulations under a similar model

To examine the performance of the model, we simulate data under a very similar model to the lineage model, using a variety of parameters to compare against inferred values. We simulate coalescent trees with a specified number of tips and a fixed number of segregating sites, using the ms program with the appropriate options (Hudson 2002). This model differs from ours in using an infinite sites, rather than a finite sites, model. We then randomly choose a fraction of these SNPs to be null and set all their allele states to zero or one with probability We generate the mixture proportions within samples by drawing N times from a Dirichlet distribution with αK varying with a mixture parameter ρ. We construct αK as 1K + ρ⋅1u>0.1, where 1 is an indicator function and the vector u consists of K uniform draws from the unit interval. We combine the lineage states and pool proportions to yield the proportion of reference alleles, modified by the error rate as in Equation 2. We then draw the desired number of read counts for each SNP for each sample from a binomial distribution with parameter To understand the performance of the algorithm across different parameter regimes we simulated SNP count data with parameters found in Table 2. For all parameter values, we fix the number of pools to N = 7 and the number of lineages to K = 6 and ran 10 independent simulations.

Table 2. Parameter values used in model simulations.

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| No. SNPs (M) | 25, 100, 250, 1000 |

| No. reads | 2, 5, 10, 50 |

| SNP error rate (η) | 0, 0.001, 0.05, 0.15 |

| Mixture parameter (ρ) | 0, 1.5, 4, 10 |

| Fraction of null SNPs (1 − λ) | 0, 0.05, 0.15, 0.3 |

An example:

We begin with an in-depth example from the simulations, with 250 SNPs, a read depth of 10, λ = 0.95, η = 0.001, and ρ = 4. Like all of our simulations, there are seven pools and six lineages. We select an iteration where the model moderately underestimates the number of lineages to examine how the model copes with partially incorrect inference.

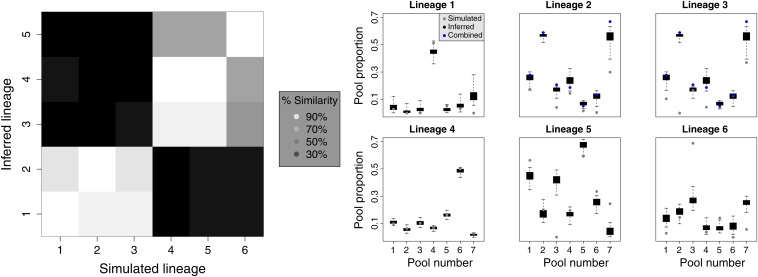

We present the simulated and inferred lineage models in Figure 2. The dark blue tree shows the maximum posterior probability tree while the remaining trees in light blue each show a sample from the MCMC. The model infers only five lineages, collapsing lineages 2 and 3 into one, although the trees appear otherwise congruent. The pie charts of pool proportions below the inferred trees show the 5%, mean, and 95% estimates with colors shaded from darkest for the 5% estimates through the lightest for the 95% estimates. The mean estimates appear close to the simulated values, although some fraction of the proportion for lineage 6 in pool 3 appears to have “migrated” to lineage 5. Figure 3, left, compares the SNP patterns of the six simulated lineages against those of the five inferred lineages, with the lowest fraction of concordance within any column as 83%. Figure 3, right, shows that inference of pool proportions generally performs well. Direct comparison of simulated pool proportions for lineages 2 and 3 appears to indicate poor performance, although we observe that combining the simulated values for these lineages (in blue) substantially improves the agreement.

Figure 2.

Comparison between simulated tree and pool proportions (left) and inferred trees and pool proportions (right). In the inferred model, the dark blue tree shows the maximum posterior probability tree with the light blue trees representing samples from the MCMC. Pie charts on the right show inferred pool proportions, with shades indicating the posterior percentile from dark (5%) to light (95%).

Figure 3.

(Left) Percentage of SNP similarity between simulated and inferred lineages. (Right) Comparison between pool proportions for simulated (light gray) and inferred (dark gray) values for each simulated lineage. Blue circles show combined proportions for simulated lineages 2 and 3.

Absent an explicit modeling framework, researchers might naturally seek to understand metagenomic SNP count data by using principal components analysis (PCA), a general approach to high-dimensional data exploration (Jolliffe 2005). We compare the results above to those from PCA, as shown in Supporting Information, Figure S1. The PCA analysis indicates that a large majority of the variation between samples can be explained by the first two components. Examination of these components shows a distinct separation of pools 1, 4, 5, and 6 from pools 2, 3, and 7, consistent with simulated data. Additional components give similar portraits but with additional separation for pool 6 from pools 1, 4, and 5. In this example PCA analysis appears to provide a general method of separating pools based on SNP count similarity but is difficult to further interpret.

Comparison across parameters:

We present the collected results for the model simulations in Figure 4 for varying numbers of SNPs, read count depths, and error rates. Figure 4, left, shows lineage performance in terms of the fraction of concordant SNPs between each simulated lineage and its closest inferred lineage. Figure 4, right, shows pool performance as the mean absolute deviation between simulated and inferred values. The lineage summaries indicate that the read count depth affects performance most strongly, with more moderate changes coming from the number of SNPs and the error rate. The number of SNPs and error rate more strongly influence pool proportion inference, where read count contributes little. We also find that increasing mixing correlates with increasingly poor lineage concordance. The fraction of null SNPs alters performances negligibly.

Figure 4.

Comparison of simulated and inferred values for lineages (left column) and pool proportions (right column) by number of SNPS (A and B), number of reads (C and D), and error rate (E and F). Insets give mixture value (“Mix”), number of read counts (“Reads”), number of SNPs (“SNPs”), and error rate (“Err”).

Topological performance and model selection:

Assessing the topological performance for the lineage model presents a significant challenge due to two related issues: that the number of taxa is not fixed and that the taxa themselves are not uniquely identifiable. In standard phylogenetic contexts, the fixed number of samples and their unique identification are implicitly used in standard algorithms to assess topological congruence (Planet 2006). We have not able to find an applicable approach in the literature nor have we been able to develop a straightforward extension ourselves. To provide some understanding of the quality of model performance, we visually examine the output of 10 iterations from three parameter regimes: low-quality data (M = 25, η = 0.15, d = 2, ρ = 1.5), moderate-quality data (M = 100, η = 0.05, d = 5, ρ = 4), and high-quality data (M = 250, η = 0.001, d = 10, ρ = 10). We find that empirical Bayes factor analysis underestimates the number of lineages in the low-quality regime, as might be expected, but infers values near the simulated number for the moderate- and high-quality sets, as in Figure S2. In these latter two cases, we visually compare the inferred tree against the simulated tree and find they are often consistent. Errors encountered most often took the form of merged lineages or “migrating” pool proportions (Figure S3) and nearest-neighbor interchanges between taxa.

Algorithmic performance:

We implement the lineage model in C++, using the GNU Scientific Library. Our implementation shows reasonable computational speed and convergence for an MCMC-based approach and is appropriate for thousands of SNPs and up to 100 pools. For a set of 1000 SNPs, seven pools, and six lineages, a complete analysis (2 × 106 MCMC iterations) required slightly >10 hr on a multicore Linux-based laptop with a 2.1-GHz processor. As a point of comparison, these data have substantially more SNPs than in our empirical examples and on the same order as publicly available microbiome data. The algorithm performs linearly in the number of SNPs and the number of pools and worse than linearly in the number of lineages. The code is available for download at http://code.google.com/p/lineagemodel/.

Using the CODA package in R, we apply several standard metrics to assess the convergence of the algorithm, including the Gelman–Brooks test, autocorrelation analysis, and Raftery estimation of burn-in length (Geweke 1991; Raftery and Lewis 1992; Cowles and Carlin 1996; Brooks and Gelman 1998; Plummer et al. 2006). All tests indicate that the MCMC converges rapidly and consistently. Examination of the Gelman–Brooks statistics and autocorrelation analysis reveals that thinning MCMC chain output to 1 iteration in 1000 is sufficient to provide effective sampling. The Raftery estimation suggests that 1e6 iterations are sufficient to achieve stationarity for a test data set with 1000 SNPs. For most data sets, we see 10–50% acceptance rates for all parameters. Observationally, we find the model applied repeatedly on a wide variety of data sets achieves nearly identical parameter estimates.

Simulations under the island coalescent

To understand the model’s performance under a more realistic—but still idealized—context, we also simulate polymorphism data under the island coalescent model (Wakeley 2001; Hudson 2002). This model structures a coalescent process by allowing individuals to migrate among segregated populations (islands) at asymmetric rates. We employ the ms package to simulate the phylogenetic tree, specifying five islands and assuming that the population size is constant at 120 individuals within each island. Ideally, we would be able to simulate such that each read comes only occasionally from the same individual, as could be expected in a microbial experiment. Unfortunately, this is not computationally feasible, so instead we use this finite approximation. To generate the migration rate matrix we first draw from a Dirichlet distribution with parameters drawn from a Beta distribution with α = 1, β = 4, and then we multiply all off-diagonal entries by a constant ψ that we call the mixing proportion. We can then scale the degree of migration among islands, with the limit ψ = 0 enforcing the island populations to be fully segregated. Having generated an appropriate tree, we use R scripts to generate polymorphism data in the following way. Following the infinite-sites model, we distribute SNPs along the branches of the tree with probability proportional to branch lengths. This specifies the full haplotypes for each of the individuals. We then sample randomly across all sites and individuals, adjusting the number of each to account for numbers of reads and SNPs (Kimura 1969). We aggregate the results within islands to generate pool-specific count data. We use 10 for read depth and 1000 SNPs.

An example:

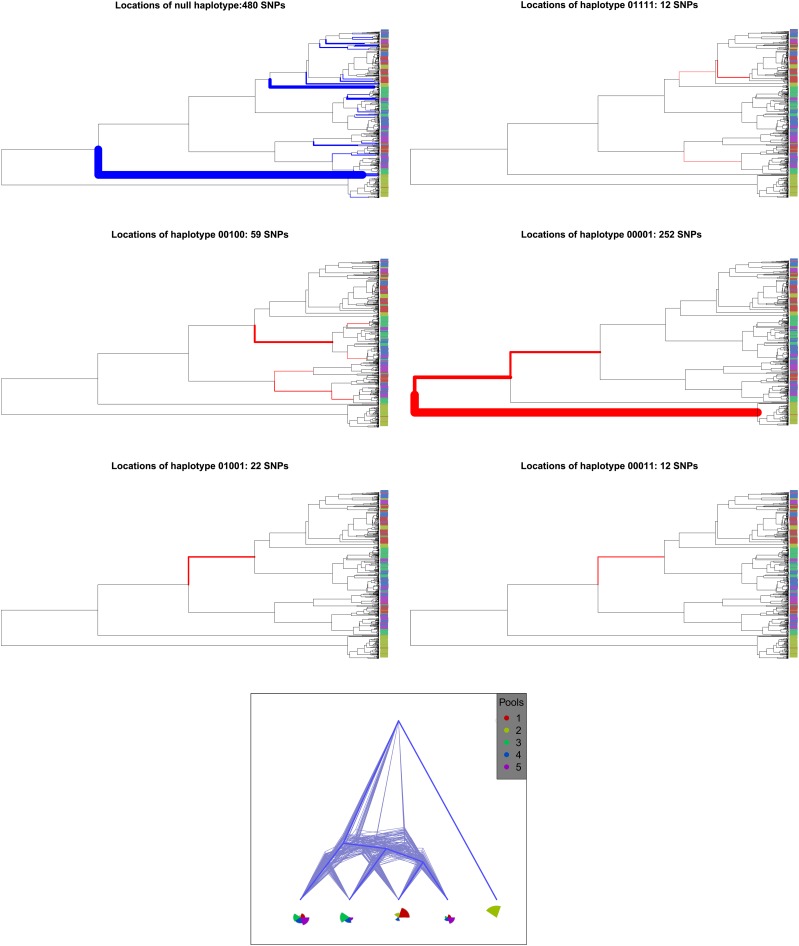

To provide a more in-depth understanding of the model’s performance, we show a typical example for data generated with a moderately high mixing proportion (ψ = 0.005). In Figure 5, bottom, we present the phylogenies and pool proportions inferred by the lineage model. The simulation provides the branch where the mutation generating each SNP occurred. For each of the 25 site patterns in the inferred model, we size the branches of the simulated tree by the number of SNPs with that inferred pattern. We color branches with phylogenetic SNPs in red and those with null SNPs in blue. The lineages are numbered from left to right so that, for example, site pattern (1, 0, 0, 0, 0) has SNP state 1 for lineage 1 and 0 otherwise.

Figure 5.

(Top) Location on simulated tree of SNPs for six sequence patterns. The branch width is proportional to number of SNPs. (Bottom) Inferred model presentation is the same as in Figure 2.

We observe that the SNPs associated with a particular sequence pattern tend to fall on a single branch or a small number of proximate branches, indicating the model’s preservation of topological structure. The inferred model appears to recapitulate much of the relative location of these branches on the phylogenetic tree and also reflect appropriate pool proportions. The null SNPs distribute relatively evenly over the tree’s tips, except for one deep branch not captured by any lineage. We note that the inferred topology is uncertain, with two trees having high posterior probability. This is driven by the model’s attempt to locate the incommensurate sequence patterns (0, 1, 0, 0, 1) and (0, 0, 0, 1, 1) as arising from mutations on the same branch within the tree. We think this is most likely due to the model lacking sufficient data to justify an additional lineage.

General performance:

Across the island coalescent simulations we find the performance of the model varies largely with the degree of mixing. To ensure a uniform scale across simulations, we examine the average pairwise distance between SNPs with a common sequence pattern divided by the average pairwise distance over the entire tree. We show the results in Figure S4. When mixing is close to zero (ψ = 0.0003), the model reduces to a single sequence pattern per sample, phylogenetic sequence patterns strongly cluster on a single branch, and the inferred phylogenies show little topological uncertainty. As ψ increases, the degree of localization decreases slightly for two orders of magnitude until rapidly increasing afterward, with the model’s topological uncertainty following a similar progression. For very high degrees of mixing, the localization for phylogenetic SNPs differs very little from that for null SNPs. For all simulations, we find the null SNPs spread evenly over external or nearly external branches. On theoretical grounds, we expect inference of phylogenetic structure to become impossible as the mixing rate tends to infinity, so the model appears to be performing in a reasonable way.

Empirical Examples

Green sulfur bacteria in an Antarctic lake

The Chlorobium genus comprises a class of green sulfur bacteria that are one of the most photosynthetically productive microbial populations in anoxic aquatic environments. We explore the composition of Chlorobium strains from a set of metagenomic samples taken at differing depths within Ace Lake, a pristine, anoxic, marine-derived, stratified lake in Antarctica formed ∼5000 years ago, as well as two nearby marine samples. Lauro et al. (2011) provide a full description of the collection regime and an integrated, functional metagenomic analysis.

We examine data from nine whole-genome sequence samples and their metadata (443679.3–443687.3) downloaded from the MG-RAST server on October 15, 2011 (Meyer et al. 2008). One freshwater sample contains no metadata on sample depth collection. For comparison against a Chlorobium sequence, we downloaded the genome for Chlorobium limicola from the NCBI Genome Project Web site on October 20, 2011 (Geer et al. 2010). We employ the de novo variation detection algorithm Cortex to ascertain SNPs and their counts per sample. We exclude four samples (4443679.3, 4443680.3, 4443681.3, and 4443685.3) due to low coverage for most SNPs, leaving three lake samples and two marine samples. We also remove indel variants and SNPs with <70 read counts across the remaining samples, leaving 345 SNPs for analysis.

Figure 6 shows the inferred lineage model for the five samples. Lineage 1 is found only in Ace Lake samples, while lineage 2 is found only in marine samples. We note that the deep divergence time of lineage 1, substantially present within all lake samples, is consistent with long-term isolation of Ace Lake. Lineage 5 shows the presence of a unique strain within the 23-m sample, consistent with previous analysis (Lauro et al. 2011). Lineage 4 appears to be present in all samples, although preferentially in those from the lake. Lineage 3 is similar, but has no contribution to the deep water sample. We note that pool proportions of the unknown sample (green in Figure 6) indicate that it likely has a similar collection location to that of the 12-m sample.

Figure 6.

Inferred lineage model for Chlorobium data from Ace Lake and open ocean samples.

Mixed infections of Plasmodium falciparum in northern Ghana

Plasmodium falciparum is the causative agent of most severe malaria worldwide and is endemic in a large section of sub-Saharan Africa (Snow et al. 2005). Examinations of infected blood samples frequently show multiple strains of parasites present within a single host, although the clinical import is debated (Genton et al. 2008). A recent examination of whole-genome-sequenced parasite samples taken from clinical isolates indicates that the degree of mixed infections varies strongly by geographic region, with western Africa exhibiting the highest values (Manske et al. 2012).

Each P. falciparum cell contains exactly two plastids: a mitochondrion and an apicoplast. The apicoplast is a chloroplast-derived plastid necessary for essential heme metabolism. Following methods in Manske et al. (2012), we ascertain 123 SNPs from the apicoplast within 20 clinical isolates from the Kassena-Nankana district (KND) region of northern Ghana. The model infers nine lineages shown in Figure 7. Lineages 2, 5, and 8 appear to be largely unmixed in their respective samples, while lineages 1, 3, 4, and 9 appear almost exclusively in mixed samples. Lineages 6 and 7 appear in both mixed and unmixed samples. We note that two lineages, 2 and 8, appear to dominate about half of the samples. The topological uncertainty suggests that the data may not be yet sufficiently high quality for precise inference. However, the output strongly indicates the presence of mixed infections, consistent with estimates from the nuclear genome, and suggests that the degree of mixture may vary with the underlying sequence.

Figure 7.

Inferred lineage model for Plasmodium falciparum apicoplast data from 20 clinical samples from northern Ghana.

Neisseria meningitidis in sub-Saharan Africa

We examine data from field samples of Neisseria meningitidis collected on sequential visits to the Kassena-Nankana region in northern Ghana (Leimkugel et al. 2007). N. meningitidis exists as nonpathogenic flora in the naval cavity of ∼10% of adults (Caugant et al. 1994). The same bacteria may exhibit hypervirulent forms, leading to severe meningococcal meningitis (Caugant 2008). In sub-Saharan Africa, these virulent bacterial forms appear as an epidemic each 8–12 years in the dry season, and researchers believe that these occurrences travel as “waves” across the continent from west to east (Leimkugel et al. 2007). Researchers collected field samples from different individuals in two villages within the Kassena-Nankana district from 1998 until 2008, although we examine only the subset of samples from 1998 to 2005.

For sequencing, individual samples were pooled by villages and by years, giving us 10 pools, with 2 pools per epidemic season (1998–1999, 1999–2000, etc.). Sequencing was performed on early Illumina technology and before the development of tags. Using the read data, we ascertained SNPs using a novel de novo assembly approach outlined in Ahiska (2011). After cleaning for quality, we find 1099 sites with a mean read count depth per site of 54.53 reads. Applying the lineage algorithm to these data yields the five lineages shown in Figure S5. Pools 7–10 correspond to years 2001 and 2002, when researchers previously noted the advent of a new sequence type in the KND. The lineage model clearly separates the two epidemiological waves, as well as possible “subwaves” distinct from the dominant strains.

Discussion

Biologists now produce enormous amounts of metagenomic data, investigating a range of systems from the microbiomes of beehives to the microflora of ocean vents. Analyses of these data usually assess the proportions of living domains that read data can be uniquely mapped into and compare across samples by contrasting their compositions. These investigations naturally focus on macroevolution across species, phyla, or families, where genomic change is so substantial among clades that each can be treated as fixed. Often these studies focus only on the signal from a single gene, such as 16S sRNA.

In this article, we consider metagenomics in the domain of microevolution, where genomic changes occur on the same timescale as environmental mixing, as in microbiomes, epidemics, or cancer cell lines. This regime corresponds to the island coalescent model when the migration and mutation parameters are roughly on the same timescale. We show that in this circumstance we can extract a meaningful phylogenetic signal. The mixing rate is the key: for a small rate, the situation effectively reduces to a standard phylogenetics problem; when it is very high, we cannot parse out pool mixtures from the tree information; in between, we can make reliable inference. However, we cannot yet provide precise guidelines about where this distinction occurs in biological systems, although we empirically observe that the model produces equal estimates of pool proportions across all lineages and high tree uncertainty when confronted with very highly mixed samples. The model’s current implementation works well for trees with K ≤ 20, although this is a practical constraint reflecting the rate of MCMC convergence. Our three empirical examples also give some guidance for appropriate applications of the model.

If reference trees are available, researchers may use phylogeny-aware alignment algorithms such as pplacer, EPA, PaPaRa, or PAGAN (Matsen et al. 2010; Berger et al. 2011; Berger and Stamatakis 2011; Löytynoja et al. 2012). Although the approach varies, each of these methods aligns read data to guide alignments using reference trees to determine the best homology. The read-placement counts on the tree could then be used to infer sample mixture. However, in the context of closely related species or novel subspecies, these reference trees will not generally be available.

In deciding whether to use the lineage model, two related questions must be addressed: How can it be determined when reads come largely from a set of closely related species? And why would one use the lineage approach rather than phylogenetic placement? We do not directly address the first question here but note that this has already been the subject of much previous research. In each of our empirical examples we consider previously analyzed data where researchers determined that this was likely the case with their data. However, in general, one might use phylogenetic placement to determine whether use of the lineage model was appropriate. If in mapping reads to reference genomes (or similar guide alignment approaches) one uncovers that nearly all reads map to a single species, or a small number of closely related species, but there still appears to be significant variation relative to the references, then the lineage model would be appropriate to resolve the underlying tree. This leads naturally to an answer to the second question: the lineage model is not an alternative to placement methods; it is operating in the regime where placement methods are limited by an absent or limited number of reference sequences. In both the Chlorobium and Plasmodium examples, the samples represented closely related subspecies, and so phylogenetic placement would not be possible based on currently available genomes.

To implement our model, we make a number of simplifying assumptions. We assume that the pools are independent of each other, that SNPs are unlinked, and that recombination is nonexistent. In almost any biological experiment these postulates will be violated in some fashion. However, all violations are not created equal. Obligate recombination that occurs in sexual organisms will undoubtedly confound the model, rendering tree inference very questionable (Schierup and Hein 2000). On the other hand, a moderate frequency of co-occurrence on reads for some SNPs will not prevent the model from functioning at all: we currently just neglect the additional information that would provide. Similarly, some nonindependence among pools will likely not harm the quality of inference under the model.

We believe a place of possible improvement in our current implementation to be in our error model, where we treat every read as possessing possible sequencing errors. While the model is helpful in separating phylogenetic SNP variation from noise, we hope in the future to implement more biologically sophisticated models where low-frequency variants can be included. We conjecture that the inclusion of SNP count data, the states of multiple SNPs from a single organism, such as paired-end data or longer read data, will help us fill this gap. These reads provide strong evidence about the state of the lineages in reality, and their inclusion into the model should permit better inference and more elaborate population models. Our experience suggests that this extension will present a methodological challenge in the MCMC framework in finding approaches that efficiently mix over the parameter space.

Another natural extension is to weaken the assumption that the pools are independent. In most studies we would expect a priori that pools’ composition will have strong correlations, induced by the sampling procedure in time or space or both. Including these structures will provide strong indications about the pool composition, since nearby pools are presumably composed more similarly than distant ones. We expect that a Gaussian Markov random field prior on the pool distribution determined by the graph representing the experimental sampling procedures (e.g., sampling times) will prove an efficient means of incorporating this information (Rue and Held 2005).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their careful readings and suggestions to improve the manuscript. We thank Sarah D'Adamo for copyediting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: M. A. Beaumont

Literature Cited

- Ahiska, B., 2011 Reference-free identification of variation in metagenomic sequence data using a statistical model. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Allen E. E., Banfield J. F., 2005. Community genomics in microbial ecology and evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3: 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balding D., Nichols R., 1995. A method for quantifying differentiation between populations at multi-allelic loci and its implications for investigating identity and paternity. Genetica 96: 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley D. R., Balasubramanian S., Swerdlow H. P., Smith G. P., Milton J., et al. , 2008. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 456: 53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S. A., Stamatakis A., 2011. Aligning short reads to reference alignments and trees. Bioinformatics 27: 2068–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger S. A., Krompass D., Stamatakis A., 2011. Performance, accuracy, and web server for evolutionary placement of short sequence reads under maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 60: 291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S. P., and A. Gelman, 1998. General methods for monitoring convergence of iterative simulations. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 7: 434–455. [Google Scholar]

- Caugant D. A., 2008. Genetics and evolution of Neisseria meningitidis: importance for the epidemiology of meningococcal disease. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8: 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caugant D. A., Hoiby E. A., Magnus P., Scheel O., Hoel T., et al. , 1994. Asymptomatic carriage of Neisseria meningitidis in a randomly sampled population. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32: 323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffron S., Rehrauer H., Pernthaler J., von Mering C., 2010. A global network of coexisting microbes from environmental and whole-genome sequence data. Genome Res. 20: 947–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowles M. K., Carlin B. P., 1996. Markov chain Monte Carlo convergence diagnostics: a comparative review. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 91: 883–892. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A., Rambaut A., 2007. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7: 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Rambaut A., Shapiro B., Pybus O. G., 2005. Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22: 1185–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L., Slatkin M., 1995. Maximum-likelihood estimation of molecular haplotype frequencies in a diploid population. Mol. Biol. Evol. 12: 921–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J., 1981. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 17: 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J., 2004 Inferring Phylogenies. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Geer L. Y., A. Marchler-Bauer, R. C. Geer, L. Han, J. He et al, 2010. The NCBI biosystems database. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genton B., D’Acremont V., Rare L., Baea K., J. C. Reeder et al, 2008. Plasmodium vivax and mixed infections are associated with severe malaria in children: a prospective cohort study from Papua New Guinea. PLoS Med. 5: e127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geweke J., 1991. Evaluating the accuracy of sampling-based approaches to the calculation of posterior moments. Vol. 196. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Gill S. R., Pop M., DeBoy R. T., Eckburg P. B., Turnbaugh P. J., et al. , 2006. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science 312: 1355–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenspan G., Geiger D., 2004. Model-based inference of haplotype block variation. J. Comput. Biol. 11: 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson R., 2002. Island models and the coalescent process. Mol. Ecol. 7: 413–418. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck J. P., Ronquist F., Nielsen R., Bollback J., 2001. Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology. Science 294: 2310–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal Z., Caccamo M., Turner I., Flicek P., McVean G., 2012. De novo assembly and genotyping of variants using colored de Bruijn graphs. Nat. Genet. 44: 226–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I., 2005 Principal Component Analysis. John Wiley & Sons, New York/Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Jukes, T. H., and C. R. Cantor, 1969 Evolution of protein molecules, pp. 21–132 in Mammalian Protein Metabolism, Vol. III, edited by M. N. Munro. Academic Press, New York/London/San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Kass R. E., Raftery A. E., 1995. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 90: 773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M., 1969. The number of heterozygous nucleotide sites maintained in a finite population due to steady flux of mutations. Genetics 61: 893–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa K., Itoh T., Kuwahara T., Oshima K., Toh H., et al. , 2007. Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Res. 14: 169–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauro F., DeMaere M., Yau S., Brown M. V., Ng C., et al. , 2011. An integrative study of a meromictic lake ecosystem in Antarctica. ISME J. 5: 879–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimkugel J., Hodgson A., Forgor A., Pfluger V., Dangy J.-P., et al. , 2007. Clonal waves of Neisseria colonisation and disease in the African meningitis belt: eight-year longitudinal study in northern Ghana. PLoS Med. 4: e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R., 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löytynoja A., Vilella A. J., Goldman N., 2012. Accurate extension of multiple sequence alignments using a phylogeny-aware graph algorithm. Bioinformatics 28: 1684–1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manske, M., O. Miotto, S. Campino, S. Auburn, J. Almagro-Garcia et al., 2012 Analysis of Plasmodium falciparum diversity in natural infections by deep sequencing. Nature 487: 375–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez I., Wallace G., Zhang C., Legge R., Benson K., et al. , 2009. Diet-induced metabolic improvements in a hamster model of hypercholesterolemia are strongly linked to alterations of the gut microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75: 4175–4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsen F., Kodner R., Armbrust E. V., 2010. pplacer: linear time maximum-likelihood and Bayesian phylogenetic placement of sequences onto a fixed reference tree. BMC Bioinformatics 11: 538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mau B., Newton M. A., Larget B., 1999. Bayesian phylogenetic inference via Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. Biometrics 55: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer F., Paarmann D., D’Souza M., Olson R., Glass E. M., et al. , 2008. The metagenomics rast server - a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics 9: 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton M. A., Raftery A. E., 1994. Approximate Bayesian inference with the weighted likelihood bootstrap. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 56: 3–48. [Google Scholar]

- Partida-Martinez L. P., Hertweck C., 2005. Pathogenic fungus harbours endosymbiotic bacteria for toxin production. Nature 437: 884–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard J. K., Stephens M., Donnelly P., 2000. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155: 945–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planet P. J., 2006. Tree disagreement: measuring and testing incongruence in phylogenies. J. Biomed. Inform. 39: 86–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M., Best N., Cowles K., Vines K., 2006. CODA: convergence diagnosis and output analysis for MCMC. R News 6: 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Preidis G. A., Versalovic J., 2009. Targeting the human microbiome with antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics: gastroenterology enters the metagenomics era. Gastroenterology 136: 2015–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery A. E., Lewis S. M., 1992. Practical Markov chain Monte Carlo: comment: one long run with diagnostics: implementation strategies for Markov chain Monte Carlo. Stat. Sci. 7: 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P., 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rue, H., and L. Held, 2005 Gaussian Markov Random Fields: Theory and Applications. Chapman & Hall, London/New York. [Google Scholar]

- Schierup M. H., Hein J., 2000. Consequences of recombination on traditional phylogenetic analysis. Genetics 156: 879–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeisser C., Steele H., Streit W., 2007. Metagenomics, biotechnology with non-culturable microbes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75: 955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow R., Guerra C., Noor A., Myine H., Hay S., 2005. The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 434: 214–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens M., Smith N., Donnelly P., 2001. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68: 978–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavare S., 1984. Line-of-descent and genealogical processes, and their applications in population genetics models. Theor. Popul. Biol. 26: 119–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringe S. G., von Mering C., Kobayashi A., Salamov A. A., Chen K., et al. , 2005. Comparative metagenomics of microbial communities. Science 308: 554–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson G. W., Chapman J., Hugenholtz P., Allen E., Ram R., et al. , 2004. Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature 428: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mering C., Hugenholtz P., Raes J., Tringe S. G., Doerks T., et al. , 2007. Quantitative phylogenetic assessment of microbial communities in diverse environments. Science 315: 1126–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeley J., 2001. The coalescent in an island model of population subdivision with variation among demes. Theor. Popul. Biol. 59: 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino D. R., Birney E., 2008. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18: 821–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.