Abstract

TCR-dependent signaling events have been observed to occur in TCR microclusters. We found that some TCR microclusters are present in unstimulated murine T cells, indicating that the mechanisms leading to microcluster formation do not require ligand binding. These preexisting microclusters increase in absolute number following engagement by low-potency ligands. This increase is accompanied by an increase in cell spreading, with the result that the density of TCR microclusters on the surface of the T cell is not a strong function of ligand potency. In characterizing their composition, we observed a constant number of TCRs in a microcluster, constitutive exclusion of the phosphatase CD45, and preassociation with the signaling adapters LAT and Grb2. The existence of TCR microclusters prior to ligand binding in a state that is conducive for the initiation of downstream signaling could in part explain the rapid kinetics with which TCR signal transduction occurs.

Introduction

T cells are continuously tasked with discerning rare antigenic peptide-bound major histocompatibility complexes (pMHCs2) originating from exogenous pathogens from abundant pMHCs loaded with self peptides derived from proteins originating from host tissue, a process known as ligand discrimination. A classical immunological synapse (IS3) (1, 2) is formed between a T cell and an agonist-presenting APC upon successful T TCR signaling, leading to ligand discrimination. Within the synapse, TCR signaling occurs in TCR microclusters that exclude CD45 (3, 4), are enriched in tyrosinephosphorylated signaling molecules (3, 5), costimulatory molecules (6), and other signaling adaptors (3, 7). Sustained T cell signaling has been correlated with the continuous generation of TCR microclusters at the periphery of the contact with APCs, which translocate in an actin-dependent manner to the center of the contact area, where they coalesce to form the central supramolecular activation cluster (cSMAC4) (4, 5). Ligand discrimination by TCR most likely occurs in TCR microclusters; however, it is not clear if the formation of TCR microclusters is part of the discrimination process.

TCR organization in the plasma membrane plays a role in T cell responsiveness to pMHC, as the oligomeric state of the TCR at least partially controls the ability of TCRζ to be phosphorylated. Using electron microscopy and two-dimensional gel electrophoresis techniques, Schamel and colleagues reported that the TCR exists as oligomers in the plasma membrane containing 2-20 TCRs, with the larger oligomers responsible for sensing low densities of antigen (8). In activated and memory-phenotype cells, several groups have correlated increases in TCR clustering with increased avidity (9-11). Similar TCR aggregation phenomena have also been observed using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy techniques. One study found nanoclusters of TCRζ in unstimulated Jurkat cells (12), while another reported similar structures that grow in size upon agonist pMHC binding (13). It is therefore possible that the microclusters visualized by diffraction-limited microscopy may be a collection of nanoclusters that have coalesced in response to stimulation by agonist pMHC.

It is unknown if these changes in the aggregation state of the TCR are directly linked to the initiation of downstream signaling. Observations made using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy have shown that the adaptor molecule the linker for activation of T cells (LAT5) and the TCR exist in separate protein islands that concatenate upon agonist stimulation (13). Additionally, endosomal pools of LAT that traffic to the TCR only after antigen engagement have also been described (14-16). Others have reported, however, that LAT and TCRζ□ exist in the same nanostructures at the basal state (12) and that this pool of LAT, not the LAT in the endosomal compartment, is phosphorylated upon antigen stimulation (17). In this scenario, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (Grb26) is recruited to phosphorylated LAT after TCR activation. The literature suggests, therefore, a process of TCR triggering that relies on at least two distinct phenomena, the formation of higher-order TCR oligomers and the subsequent recruitment of effector molecules to the microclusters to allow for the initiation of downstream signaling. Upon ligand engagement, TCR signaling occurs with rapid kinetics. It has been shown that it takes approximately 6 seconds for calcium influx to occur after ligand binding and 4 seconds for recruitment of Grb2 to TCR microclusters (7). TCR signaling also exhibits a digital characteristic, as presentation of a single agonist peptide by an APC leads to T cell activation and cytokine production (18, 19). The distribution of signaling molecules relative to the TCR that contributes to the speed and sensitivity of TCR signaling is not fully understood.

The relationship between ligand binding and TCR microcluster formation is not clear. If ligand binding drives microcluster formation, then reducing ligand affinity as well as density could modulate this process. Altered peptide ligands (APLs7) contain mutations in key TCR contact residues, and the result of the mutations is ligands with altered binding characteristics to the TCR that correlate with their signaling potential (20). Here, we use APL stimulation and reduced agonist density as tools to perform a systematic analysis of the dependence of TCR microcluster formation on ligand binding. We find that some TCR microclusters exist in agonist naïve cells, and their density on the cell surface does not increase in proportion to ligand density or affinity. In addition, their composition prior to ligand binding may explain the rapid kinetics with which TCR signaling is observed.

Materials and Methods

Statistical Methods

Prism was used for computation of all statistical parameters. For grouped analyses, a oneway ANOVA test was performed using the Bonferonni correction with the 95% confidence interval used for assigning significance differences. Throughout the manuscript, *, **, and *** refer to p<0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively.

Peptides

All peptides used in the study were synthesized commercially (American Peptide Company) and purified to greater than 95% by reverse phase HPLC. The sequences of the peptides used in the study are: moth cytochrome c [MCC8 (88-103)]: ANERADLIAYLKQATK, K99A: ANERADLIAYLAQATK, T102L: ANERADLIAYLKQALK, β-2m: HPPHIEIQMLKNGKKIP, K5: ANDERADLIAYFKAATKF, ER60: GFPTIYFSPANKKL, cCYT: VNKEIQNAVQGVK, MSA: TPTLVEAARNLGRVG, HSP70: DNRMVNHFIAEFKRK, and α-trp: YDRNTKSPLFVGKV.

Mice and T Cell Activation

All mice were obtained from Taconic Farms, Inc. Additionally, all animals used in this study were maintained in a specific pathogen-free environment, and the National Institutes of Allergy and Infection Diseases Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experiments. AND TCR transgenic RAG2 −/− mice on the C57BL/6 background and RAG2 −/− mice on the B10.A background were crossed to produce AND mice on the mixed H-2b/H-2k background. We refer to these as AND mice. For activation, naïve AND T cells from mice aged no older than 3 months were mixed with splenocytes from a CD3ε −/− mouse on the B10.A background in Advanced DMEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 2.5% defined FBS (Hyclone), Penicillin/Streptomycin, glutamine, and 10 μM MCC (88-103) peptide. The cells were plated in 12 well plates (2 mL/well) at a density of 10 million cells/mL and allowed to activate for 48 hours. At this point, cells were counted and reseeded in flasks with 50 U/mL of murine IL-2 (PeproTech) at a density of 2 million viable cells/mL. Every 48 hours thereafter, cells were reseeded in fresh medium containing IL-2 and the density readjusted to 2 million cells/mL. We refer to these rested cells as preactivated AND T cells and used them between days 7 and 10 after activation.

Nucleofection and Enhanced GFP (EGFP 9) Fusion Constructs

For the expression of EGFP-tagged fusion proteins, activated AND T cells were transfected using the Amaxa® Mouse T Cell Nucleofector® Kit (Lonza), as describe in detail elsewhere (21). Briefly, 5 million AND T cells were harvested by pelleting at 75 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was removed by aspiration, and the cells were resuspended in nucleofector solution containing 5 μg of plasmid DNA. Cells were then transferred to an electroporation cuvette and transfected using program X-001. Following this, cells were transferred using the provided plastic transfer pipette to preequilibrated (in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for one hour) culture medium. Cells were rested for 4 hours to allow for EGFP-tagged protein expression and used directly for imaging. Naïve AND T cell transfection was carried out with the following differences: 5 μg of DNA was used to transfect 10 million cells, and the cells were incubated at 30 °C for three hours following transfection. All EGFP fusion proteins used in this study were cloned between the XhoI and HindIII sites in the pEGFP-N1 expression vector (Clonetech), and all cDNA used was of murine origin (OpenBiosystems).

Supported Lipid Bilayers

Fluid lipid bilayers comprised of 6.25% Ni-NTA and 93.75% DOPC lipids were formed either on piranha solution cleaned coverglass (Bioptechs) or on silica beads (4.3 μm MicroSil Microspheres, 10% solids, Bangs Laboratories). Unless otherwise specified, the purified extracellular domains of the following proteins were incorporated at the indicated density: Histidine6-tagged (on both α and β chain), peptide-loaded I-Ek at 5 molecules/μm2, His12-tagged ICAM-1 at 100 molecules/μm2, and GPI-anchored CD80 or his-tagged CD80 at 100 molecules/μm2. The process for preparing bilayers on both coverglass and silica beads and quantifying the adsorbed amount of histidine-tagged molecules has been previously described (22). For pMHC complex trapping experiments, variants of all peptides that contained an N-terminal cysteine were synthesized (CPC Scientific) and site-specifically labeled (NIAID Peptide Synthesis Facility) with AlexaFluor 568 maleimide (Life Technologies). ICAM-1 was labeled with AlexaFluor 647.

Microscopy

Simultaneous, two-color total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM10) was used to study the localization of EGFP-tagged signaling proteins in TCR microclusters. Custom-designed TIRF optics that minimize chromatic effects were built around an Olympus IX71 fluorescence microscope. This method was published elsewhere in great detail (21), but we briefly describe the crucial features of the system. TIRF was accomplished using a through-the-objective approach using an infinity-corrected 150X magnification, 1.45 numerical aperture (NA) TIRFM objective (Olympus), which provides a final optical resolution of 0.1 μm per pixel. Beams from an argon-ion and 561 nm diode pumped solid state (DPSS) laser (providing illumination of 488, 514 and 561 nm) are routed through an acousto-optical tunable filter for intensity control and subsequently through a single-mode fiber for delivery to the TIRF launch. Light emitted from the sample is reflected out of the right side port of the microscope where it is split into two distinct beams (EGFP emission and AlexaFluor 546 emission) by a dichroic mirror (Chroma) and focused by tube lenses. Finally, emission filters are placed just before each of two identical QuantEM electron multiplying EM-CCD cameras (Photometrics) that capture and record the fluorescence signal. EM-CCD cameras were chosen for their sensitivity, which allows for the observation of low levels of EGFP-tagged proteins, obviating the need for gross overexpression of signaling molecules.

For imaging, T cells (5 × 106 for agonist ligands, 10 × 106 for APL ligands) are resuspended in HEPES-buffered saline containing BSA (HBS/BSA) and 10 μg/mL of H57 or I3/2.3 Fab. T cells are then injected into a thermostated flow chamber (Bioptechs) maintained at 37°C where they are imaged for up to 1 hr. To prevent photodamage, the combined laser power at the sample interface for all laser lines used is limited to 50 μW.

T Cell Labeling with DiO

T cells were labeled with DiO (Life Technologies) by suspending the cells in serum-free Advanced DMEM containing 2.0 μL of DiO/mL at a density of 1.0 × 106 cells/mL. The cells were then incubated for 10 min., washed three times, and used directly for imaging.

Quantifying Punctate Structures

Quantifying punctate distributions of fluorophores in fluorescence microscopy images representing endosomes or clusters of cell surface proteins is always challenging. The punctate structures may have an average intensity as low as 1.2 fold over neighboring pixels that may be real cellular fluorescence signal and not background. Additionally, this basal signal may vary from cell to cell and may also be non-uniform across a single cell. As a result of this complexity, threshold- based methods are insufficient to quantify such punctate distributions.

An algorithm to identify punctate structures in wide field images of internalized LDL was developed several years ago (23). This method required that images be first median filtered to remove some non-uniform signal surrounding the puncta, thereby increasing the signal to noise ratio. The algorithm in its original form needed the following input values from the user,

a threshold, T

Low fraction, l

High fraction, h

Step size, s

Min area of a spot

Max area of a spot

The threshold T is applied to the median filtered image, and all pixels less than the threshold are set to zero. After this operation, the software identifies how many spots exist. Each spot is defined as a contiguous set of pixels. This could be a single spot or many spots based on the threshold value entered. The maximum intensity pixel in each spot is identified. The software then identifies all pixels that are less than the “low fraction” times the highest intensity pixel for each spot identified in the image and sets them to zero. A search is executed again to identify the number of spots. This operation may generate more spots or get rid of low intensity pixels within the single spot. The software updates this information and now the fraction value is incremented by the step size and the same process is repeated. This iterative trimming process is depicted graphically (Fig. S1A) for an example image along with the output image, in which only the punctate structures survive (Fig. S1B). While this process is very robust, to identify all the punctate structures within a single cell, the user must spend a lot of time adjusting the parameters as the optimal parameter set varies from cell to cell, making the analysis very tedious.

We modified the algorithm to reduce the subjective input from users and reduce the time required for analysis. Instead of asking the user to input a low fraction, a high fraction, and a step size, we asked the user to input a step size and based on that step size executed the above algorithm for all combinations of low and high values. When the spots routine is executed using each of the low and high fraction ranges, it will generate spots that have different extents of trimming. The next task was to come up with an objective criterion of choosing, at a single spot level, which was the best-trimmed spot. An optimally trimmed spot in one part of the image may arise from a different set of trimming parameters than in another area.

Unique spots generated by different trimming parameters were identified based on the maximum intensity pixel. We reasoned that an optimally trimmed spot is one whose average intensity does not change after a certain extent of trimming. We arranged each unique spot in ascending average intensity and normalized it to the highest average intensity. We then asked the user to input a cutoff parameter. The first spot above this cutoff parameter was chosen. Empirically, this parameter was chosen to be 0.83. If the cutoff parameter would be 0.9, then one would be choosing a more trimmed spot, and if it were less than 0.83, one would be choosing a less trimmed spot.

Other input parameters are minimum spot area, maximum spot area and threshold.

Colocalization Analysis

After image segmentation and graphical identification of microclusters of both TCR and EGFP microclusters, an algorithm that calculated the percentage of overlap in microcluster areas was applied to corresponding images. Spots of which overlapped in area by at least 40% were considered to be colocalized.

Measurement of Calcium Fluxes

For the measurement of calcium fluxes, preactivated AND T cells were loaded with the calcium sensitive dye fura-2 AM (Life Technologies). AND T cells were pelleted at 700 rpm, washed once with 10 mL of serum-free Advanced DMEM (Life Technologies), and resuspended in 1 mL of room temperature serum-free Advanced DMEM containing 2 μM Fura-2. Cells were then incubated at room temperature for 25 min in the dark. After this, 5 mL of pre-warmed ADMEM containing 2.5% serum was added to the cells, and the cells were incubated for an additional 1 h. at 37 °C. The cells were then pelleted at 700 rpm and used directly for imaging. The cells were imaged with a 40X, 1.35 NA objective and the fluorescence emission recorded for 340 and 380 nm excitation. IRM and ICAM-1 images were also collected so that cells adhering to the bilayer could be identified. As a control to determine the maximum calcium flux, the cells were subjected at the end of the experiment to treatment with 2 μg/mL ionomycin in HBS/BSA containing 2 mM MgCl2 and 20 mM CaCl2. Finally, as a control to measure the baseline Fura-2 fluorescence emission, the cells were subjected to treatment with 2 mM EGTA in calcium-free HBS/BSA containing 3 mM MgCl2.

Cell Segmentation and Tracking for calcium flux analysis

Single-cell calcium flux analysis was accomplished by first segmenting the cells in the 340 nm emission channel (Ch-340) and then tracking these binary masks corresponding to the cells. In the segmentation phase, individual Ch-340 frames of the 2D-t series data are pre-processed to enhance circular structures (cells) using a band-pass filter. The foreground objects from the pre-processed Ch-340 frame are identified using Kittler and Illingworth's Minimum-Error algorithm. This, however, leads to over-segmentation, especially when cells are closely packed. Hence, watershed, a morphology-based segmentation, is used to break down large foreground objects into individual cells. Post segmentation, a size (<150 pixels and > 2500 pixels) and shape (circularity [0.6, 1.0]) filtering removes small islands and large foreground objects (if any). All segmented objects at the edges of the frame are also ignored. These image-processing operations were implemented as an ImageJ macro with batch-processing capability.

Once the binary masks for the cells in the Ch-340 are identified, a first-order autoregression algorithm (24) implemented as MATLAB script (Mathworks, Inc.) is used for automatic object tracking in the 2D-t data. Next, the MATLAB script imports background-corrected (rolling-ball algorithm with radius of 20 pixels) 340 and 380 nm emission channels, raw IRM and ICAM-1, and binary masks of the cells from the segmentation step as a multi-channel 2D-t dataset into Imaris (Andor/Bitplane) using XTension programming interface. The tracking information from the auto-regression algorithm is also imported into Imaris as a “Surface-Surpass” object. The Surpass user interface of Imaris is used for manual/visual selection of cell tracks that make contact with the bilayer (visible in the IRM and ICAM-1 channel). The user-selected tracks are subsequently exported to a Microsoft Excel workbook. For each selected track, Imaris is configured to export mean of intensity in Ch-340 and Ch-380.

Western Blotting

For cell stimulation experiments, 1 μL of silica bead suspension was used for 0.2 × 105 T cells. This corresponds to 10 silica beads/cell. For LAT blotting, 5 million cells per condition were stimulated, followed by lysis in a buffer containing 0.5% Brij-96v, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM NaVO3, 1X PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitors, and 1X cOmplete Mini protease inhibitors (Roche) for 30 min. on ice. Following this, cellular debris was pelleted at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C, and the cleared supernatants were transferred to new tubes. Finally, SDS loading dye was added to the lysates followed by boiling for 6 minutes with intermittent vortexing. For ERK blotting, the process was the same except that 1% NP-40 was used as the detergent and only 2 million cells were stimulated per condition. Lysates were run on 4-20% SDS/PAGE gradient gels (BioRad) using a current of 25 mA/gel, and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the iBlot semi-dry transfer system (Life Technologies). Membranes were blocked with 5% blotting-grade milk (BioRad) in PBST for 1 h. at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies in PBST overnight at 4 °C with gentle mixing. After washing with PBST, membranes were probed with HRP-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling, #7074) for 1 h. at room temperature. pLAT (Y191) (Abcam, #ab-59197) and LAT (Cell Signaling, #9166) were detected by photographic film (BIOMAX XAR, KODAK). ERK and pERK (Cell Signaling, #4692 and #9102, respectively) were detected using a CCD-based chemiluminescence detection system (FluorChemQ, AlphaInnotech).

Generation of Fab Antibody Fragments

Fab fragments of the H57, against murine TCRβ chain, and I3/2.3, against murine CD45, antibodies were generated as follows. Affinity purified antibodies were concentrated to 2 mg/mL in PBS. PBS buffer was then exchanged by dialysis against 50 mM citrate buffer at pH 5.5 containing 50 mM NaCl and 25 mM cysteine (added just prior to digestion). For digestion of the antibodies, a mixture of 2 mg/mL papain (Sigma), 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 40 mM cysteine was prepared in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0. Following activation of the papain-containing solution at 37 °C for 10 min, 5 μL of activated papain solution was added per milligram of antibody to the antibody-containing solution and allowed to digest for 3 h. at 37 °C. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 5 mM iodoacetamide.

For H57, the Fab, Fc, and undigested whole antibodies were separated by ion-exchange chromatography using DEAE sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). After dialysis against 10 mM Tris buffer at pH 8.0, the digestion mixture was bound to the ion-exchange media. Separation of the fragments was accomplished by washing the column with 10 mM Tris buffer at pH 8.0 containing 50, 100, 200, 400, and 1000 mM NaCl. The Fab fragment elutes in the 50 mM NaCl wash, whole antibody at 100 mM NaCl, and Fc fragment at 200 mM NaCl. Separation was verified using SDS/PAGE. For I3/2.3, attempts to separate Fab, Fc, and undigested whole antibodies by ion-exchange chromatography were unsuccessful. In lieu of this, Fab and Fc fragments were separated from whole antibody by size-exclusion chromatography and used directly for cell labeling. Fab fragments for both antibodies were labeled with fluorescent dyes (H57: AlexaFluor 546, I3/2.3: AlexaFluor 488) using standard methods and were finally stored at 4 °C in PBS at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. After separation, the digestion products were run on an SDS-PAGE gel to ensure that no Fab2 fragments were present.

Results

APL Potency Hierarchy for the AND TCR

To study the relationship between ligand binding and TCR microclusters, we first wished to establish a range of pMHC-TCR potencies (as defined by their ability to cause calcium fluxes and ERK activation at a fixed antigen dose). We chose to compare the agonist peptide moth cytochrome c [MCC (88-103)] presented by the MHC class II molecule IEk and two APLs of the AND TCR, K99A and T102L. Additionally, we included an IEk-binding self-peptide derived from β□ 2 microglobulin (β-2m11) (25, 26) as a negative control, which does not act as a coagonist for the AND receptor (Fig. S2). Our experimental approach involved exposure of T cells to coverslips coated with fluid lipid bilayers in which agonist or APL-loaded pMHCs, the costimulatory molecule CD80, and ICAM-1 are linked via histidine tags to Ni-NTA head-group bearing lipids. T cells interacting with the bilayer are then imaged using TIRFM.

The functional characteristics of these APLs have been previously well studied (27-29) and establish a hierarchy of potencies: MCC > K99A in the presence of CD80 > K99A > T102L > β□ 2m. K99A is a costimulation-dependent agonist capable of causing proliferation (27) and inducing calcium fluxes only in the presence of CD80 costimulation, and T102L is an APL that elicits neither proliferation nor calcium fluxes but causes in vivo tolerance (29).

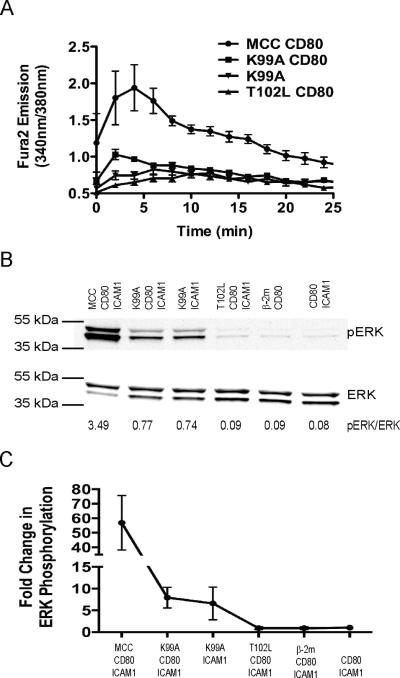

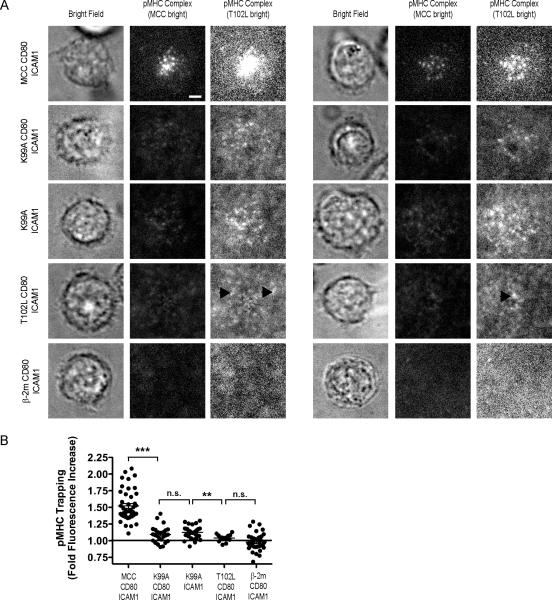

We ensured that this hierarchy of potencies was reproducible under our experimental conditions by measuring calcium fluxes and ERK activation in preactivated AND T cells in response to agonist and APL stimulation at a dose of 5 pMHC molecules/μm2 (Fig. 1 A and B). To ensure that the stimulation conditions used for assaying ERK activation were identical to those used for calcium flux measurements, we prepared silica beads coated with fluid lipid bilayers presenting either agonist or APL-loaded pMHC, CD80, and ICAM-1 to use as “artificial APCs” for T cell stimulation and performed Western blot analysis to detect phosphorylation of ERK. Stimulation with both MCC and K99A in the presence of CD80 produced calcium fluxes, while stimulation with K99A in the absence of CD80 and T102L did not. Similarly, T102L stimulation was not sufficient to activate ERK over background levels. The average fold increase in ERK activation for two experiments is presented in Fig. 1C. The hierarchy of APL potency mirrored the ability of a particular ligand to stably interact with the AND TCR within the immunological synapse, as AND T cells trapped each of the APL-loaded pMHCs except for the negative control peptide β□ 2m (Fig. 2A and B).

Fig. 1. Only Agonist Ligands Cause Robust Calcium Influx and ERK Activation.

(A) Agonist or APL-loaded I-Ek (5 molecules/μm2), CD80 (100 molecules/μm2) and ICAM-1 (100 molecules/μm2) on fluid lipid bilayers were presented to preactivated AND T cells loaded with the calcium-sensitive dye fura-2. The fluorescence emission at 340 and 380 nm was monitored for single cells for 25 minutes. The ratio of the fluorescence emissions is plotted as a function of time with error bars representing ± SEM. The number of cells tracked for MCC CD80, K99A CD80, K99A, and T102L CD80 are 44, 40, 21, and 35, respectively. (B) Fluid lipid bilayers containing agonist or APL-loaded I-Ek (5 molecules/μm2), CD80, and ICAM-1 were prepared on silica beads and used to stimulate preactivated AND T cells for 15 min. The resulting blots were probed with an antibody against phosphorylated ERK. The resulting blots were cropped to show the bands of interest. (C) Average fold change in ERK activation with respect to cells exposed to bilayers containing only ICAM-1 and CD80 for two separate experiments, with error bars representing the mean ± SD. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Fig. 2. APL-loaded pMHC Trapping by TCR Microclusters.

(A) Agonist or APL-loaded I-Ek (5 molecules/μm2) loaded with AlexaFluor 568-labeled peptides were presented to preactivated AND T cells along with CD80 (100 molecules/μm2) and ICAM-1 (100 molecules/μm2) on fluid lipid bilayers. For each pMHC, two representative cells are depicted. For each set of representative images, two fluorescence intensity scalings are depicted. “MCC and T102L bright” refer to a fluorescence intensity scale at which clusters of the respective pMHC are readily apparent, allowing for comparison of relative intensity differences between the various pMHC clusters. Black arrows serve as guides to identify especially bright clusters of T102L-I-Ek. (B) The efficiency of trapping for each pMHC complex was calculated as the ratio of pMHC fluorescence intensity beneath the bright-field image of the cell to the fluorescence intensity in regions in the same image where no cell was present. The solid line at a pMHC trapping of 1.0 serves as guide to indicate the condition when the pMHC intensities below and outside the confines of the cell are equivalent. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA test with a Bonferonni correction. Error bars represent the mean ± SEM. A minimum of 20 individual cells was quantified for each condition. Data are representative of two independent experiments. For trapping measurements, the fold fluorescence increases are reported for individual cells that had been in contact with the bilayer for up to one hour. Scale bar = 2.5 μm.

The TCR Content of a Microcluster is Invariant and TCR Microcluster Density is not a Strong Function of pMHC Potency

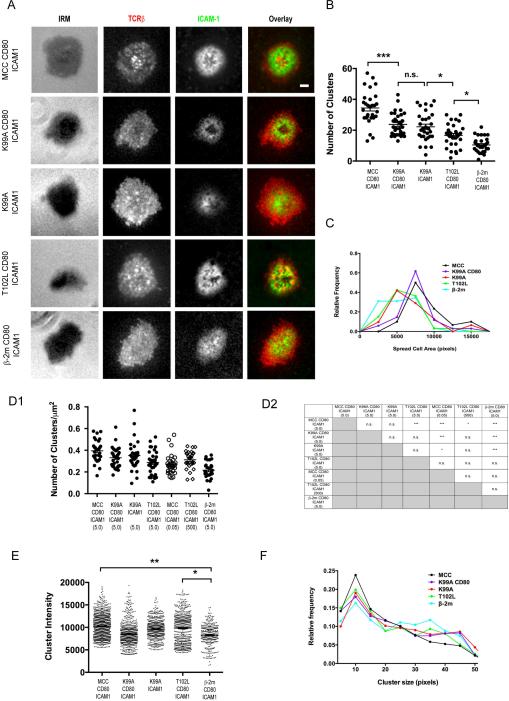

Having established the relative potencies of APL-loaded I-Ek, we next wished to examine the characteristics of the IS and TCR microclusters generated in response to each APL. Representative images of synapses formed by preactivated AND T cells in response to each pMHC ligand, at a density of 5 pMHC molecules/μm2, in the presence of 100 molecules/μm2 of both CD80 and ICAM-1, are shown in Figure 3A. Only exposure to the agonist peptide MCC led to the formation of a cSMAC, as reported previously (27, 30).

Fig. 3. Immune Synapse and Microcluster Formation in Response to APLs.

(A) Agonist or APL-loaded I-Ek (5 molecules/μm2) were presented to preactivated AND T cells stained with AlexaFluor 546-labeled H57 Fab fragments along with CD80 and AlexaFluor 647-labeled ICAM-1 on fluid lipid bilayers. (B) Total TCR microcluster counts resulting from stimulation of AND T cells with the pMHC ligands indicated in (A). For MCC- I-Ek, the cSMAC was excluded from the analysis so that only the number of peripheral microclusters were quantified. (C) Histograms of the total membrane area visible for the cells in (B) in the TIRF plane for each pMHC ligand. Relative frequency indicates the percentage of the total number of cells presenting with the indicated area. Each point represents the center of a bin of 2500 pixels. Lines serve as guides for the eye to aid in distinguishing the distributions. Cell contact areas were determined by H57 Fab staining. (D1) TCR microcluster counts from (B) normalized to the interfacial area of the T cell. (D2) Statistical significance of pair-wise comparisons from (D1). (E) Intensities of individual microclusters from (B). (F) Histograms of individual microcluster sizes for the microclusters presented in (E). Relative frequency indicates the percentage of the total number of TCR microclusters presenting with indicated size. Each point represents the center of a bin of 5 pixels. Lines serve as guides for the eye to aid in distinguishing the distributions. For (B), (D), and (E), significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA test. For all panels, error bars represent the mean ± SEM. For (B)-(F), data are pooled from cells that had been in contact with the bilayer substrate for up to 15 min. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Scale bar = 2.5 μm.

We wished to determine if ligand binding modulated the characteristics of TCR microclusters. TCR microclusters were readily detectable in all conditions tested, including on the membrane of T cells interacting with bilayers containing β-2m-I-Ek even though AND T cells do not trap this ligand. To ensure that the bright accumulations of TCR observed in the case of β-2m-I-Ek stimulation actually represented TCR microclusters and not regions of the membrane simply coming into close proximity of the lipid bilayer, we costained AND T cells with Fab fragments against TCRβ and the membrane dye, DiO. Consistent with previous findings (4), DiO is not enriched in TCR microclusters present on the membranes of AND T cells being stimulated with MCC-I-Ek but does accumulate within the cSMAC after the formation of a mature IS. In the case of β-2m stimulation, there is no observable enrichment of DiO within areas of TCR accumulation, confirming that these structures are indeed TCR microclusters (Fig. S3).

To determine the differences between TCR microclusters present in preactivated T cells being stimulated by the panel of APLs, we graphically identified TCR microclusters for all stimulation conditions using an automated segmentation algorithm (Materials and Methods and Fig. S1A and B) and quantified their absolute numbers and characteristics. T cells stimulated with T102L accumulated more TCR microclusters on average (17) than cells stimulated with the control self peptide β-2m (10) (Fig. 3B). This trend continued as the potency of the peptide increased, with K99A, irrespective of the presence of CD80, and MCC accumulating an average of 22 and 35 TCR microclusters, respectively. Since cell spreading became more robust as the potency of the pMHC being presented increased (Fig. 3C), it was important to normalize the absolute number of TCR microclusters to the spread area of the cell to determine if the observed increase in absolute microcluster number was simply due to our ability to observe more total membrane area. After normalization, we found that the average number of TCR microclusters per unit of contact area, the TCR microcluster density, increased only slightly, from 0.2 to 0.35 microclusters/μm2, when comparing cells stimulated with β-2m to those stimulated with the APLs (Fig. 3D1). A significant difference in microcluster density was also observed between cells stimulated with MCC and T102L; however, no other pair-wise differences in average microcluster densities were detected at this antigen dose (Fig. 3D2). We also wished to know if the TCR microcluster density for each ligand varied in time or was a true constant. To determine this, we plotted the observed TCR microcluster density from the cells of Fig. 3D1 as a function of the time since they were injected into the flow cell (Fig. S4), and we observed that the microcluster density fluctuated around the mean of the distribution. This indicated that the microcluster density was a constant and did not vary over the period of time during which we monitored the cells.

In order to further probe the effects of antigen dose on TCR microcluster density, we next presented AND T cells with both a limiting dose of agonist ligand (0.05 molecules/μm2), corresponding to approximately 5 pMHC ligands per cell, and a supraphysiological dose of the low potency ligand T102L (500 molecules/μm2) (Fig. 3D1). In response to the limiting dose of agonist ligand, the TCR microcluster density falls to the same level as cells stimulated with β-2m. Stimulation with the very high dose of T102L, however, fails to increase the microcluster density above levels achieved with a 100 fold lower dose of the ligand.

Additionally, we quantified the fluorescence intensities of individual TCR microclusters for each stimulation condition (Fig. 3E). Apart from a statistically significant 30% increase in microcluster intensity between β-2m and both MCC and T102L, we found that the fluorescence intensities of the microclusters present on the membranes of cells stimulated with any of the other ligands were statistically indistinguishable. To ensure that microcluster intensity differences were reflective of TCR content rather than changes in microcluster size that were a function of ligand potency, we plotted frequency distributions of microcluster sizes for each of the ligands and found them to be identical (Fig. 3F). Apart from the small difference in TCR content between microclusters observed under stimulatory versus the nonstimulatory control, these results suggest that engaging ligands of different affinities does not change the number of TCRs within a microcluster.

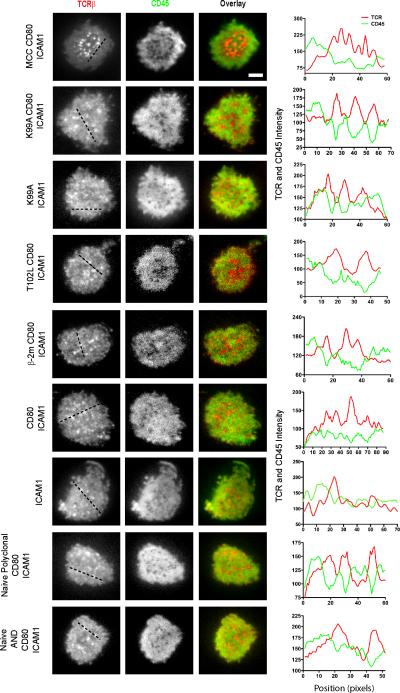

To rule out the possibility that the presence of microclusters in cells stimulated with the negative control self peptide were the result of prior in vitro activation, we next imaged naïve AND and polyclonal T cells interacting with bilayers containing only CD80 and ICAM-1 (Fig. 4) and again observed the presence of TCR microclusters. These results further confirm that TCR microclusters preexist in the absence of prior agonist pMHC engagement. CD28-CD80 interactions have also been shown to localize to TCR microclusters (6). To rule out that these interactions may have contributed to formation of microclusters, we imaged cells on substrates containing only ICAM-1 and found that microclusters could still be observed on such a substrate.

Fig. 4. CD45 is Excluded from TCR Microclusters in an Antigen-Independent Manner.

Agonist or APL-loaded I-Ek (5 molecules/μm2) were presented to preactivated AND T cells stained with AlexaFluor 546-labeled H57 and AlexaFluor 488-labeled I3/2.3 Fab fragments along with CD80 and ICAM-1 on fluid lipid bilayers. Naïve AND and polyclonal T cells from a B10.BR mouse stimulated with CD80 and ICAM-1 were also included as controls. For each image, fluorescence intensity scans across the indicated line show the intensities for TCRβ and CD45 staining. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Scale bar = 2.5 μm.

Molecular Composition of Preexisting TCR Microclusters

We have established that TCR microclusters were able to trap APL-loaded pMHC ligands and that the quantitative receptor representation is not a function of APL potency. Agonist-induced TCR microclusters have been shown to exclude the phosphatase CD45 and be enriched in signaling molecules implicated downstream of TCR engagement, such as ZAP70(3, 5), LAT(3), Grb2(3, 7), phospholipase Cγ1(31), the SH2 domain-containing leukocyte protein of 76 kD (SLP-76)(3, 5), and so on. We next wished to examine the composition of the ligand independent, preexisting TCR microclusters. We first examined if such TCR microclusters excluded the phosphatase CD45, as it has been hypothesized to be excluded from sites of TCR-pMHC interaction according to the kinetic segregation model. To determine whether CD45 was being excluded from TCR microclusters upon stimulation with APLs, we co-stained AND T cells with Fab antibody fragments against both TCRβ and CD45 and imaged them interacting with fluid lipid bilayers containing agonist or APL pMHC along with CD80 and ICAM-1, CD80 and ICAM-1, or ICAM-1 alone (Fig. 4). We found that CD45 was excluded from TCR microclusters under all stimulation conditions, including in the absence of TCR ligation. This finding extended to both naïve AND and naïve polyclonal T cells stimulated with CD80 and ICAM-1, indicating that TCR-agonist pMHC engagement is not required for the exclusion of CD45 from TCR microclusters.

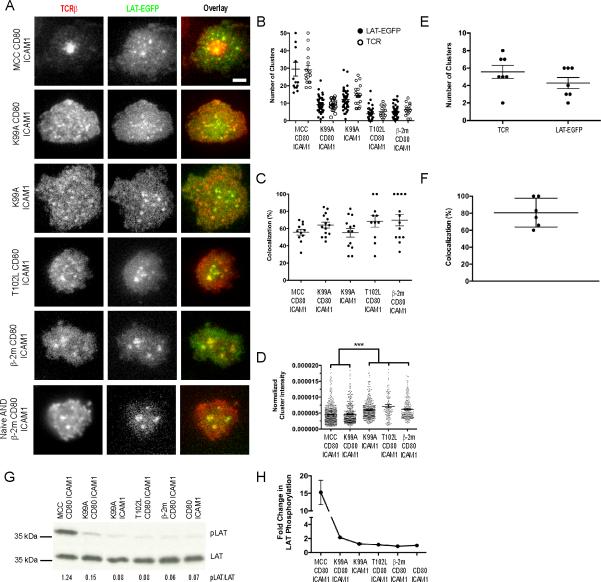

We next examined the distribution of the adapter molecule LAT with respect to TCR microclusters, as this adapter been shown to interact with TCR microclusters only after recognition of an activating ligand (13). We imaged preactivated, LAT-EGFP expressing AND T cells interacting with agonist and APL-presenting fluid lipid bilayers containing CD80 and ICAM-1 (Fig. 5A). We observed that LAT was present in TCR microclusters in all stimulation conditions that we examined. Further, we quantified the number of both TCR and LAT-EGFP microclusters using the segmentation algorithm described earlier (Fig. 5B). We found that the average numbers of TCR and LAT-EGFP microclusters were roughly equivalent for each respective stimulation condition, and both the number of TCR and LAT-EGFP microclusters otherwise increased as the potency of the ligand increased. In each case, the signal from TCRβ and LAT-EGFP strongly colocalized, and the degree of colocalization did not vary among pMHC ligands (Fig. 5C and Movies S1-S5). We additionally quantified the relative intensity of the LAT-EGFP microclusters for each stimulation condition (Fig. 5D). As the amount of EGFP-signal recorded using TIRFM at the T cell-bilayer interface is directly proportional to the expression level of the EGFP-tagged protein (Fig. S1C), we normalized the raw intensity of each LAT-EGFP cluster to the expression level of LAT-EGFP in the T cell. In this analysis, we found that when compared with ligands that do not cause detectable calcium flux, the intensity of LAT-EGFP clusters significantly decreased on T cells stimulated with ligands that do cause a calcium flux. This result is consistent with the c-Cbl-mediated endocytosis of LAT upon T cell activation reported by Balagopalan and colleagues (32).

Fig. 5. LAT Recruitment to TCR Microclusters and Activation in Response to APL Stimulation.

(A) Agonist or APL-loaded I-Ek (5 molecules/μm2) was presented to preactivated or naïve LAT-EGFP transfected AND T cells stained with AlexaFluor 546-labeled H57 Fab fragments along with CD80 and ICAM-1 on fluid lipid bilayers. (B) Total TCR microcluster and LAT-EGFP cluster counts resulting from stimulation of AND T cells as described in (A). For MCC- I-Ek, the cSMAC was excluded from the analysis so that only the number of peripheral microclusters were quantified. (C) Colocalization of TCR and LAT-EGFP microclusters from (B). Colocalization was calculated as the percentage of TCR microclusters overlapping in area with a LATEGFP cluster by at least 40%. (D) Fluorescence intensity of individual clusters of LAT-EGFP normalized to the total expression level of LAT-EGFP in each cell resulting from stimulation of AND T cells as described in (A). Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA test. (E) Total TCR microcluster and LATEGFP cluster counts resulting from stimulation of LAT-EGFP-transfected naïve AND T cells with β-2m- I-Ek. (F) Colocalization of TCR and LAT-EGFP microclusters from (E). For (B)-(F), error bars represent the mean ± SEM, and data are pooled from cells that had been in contact with the bilayer substrate for up to one hour. (G) Fluid lipid bilayers containing agonist or APL-loaded I-Ek (5 molecules/μm2), CD80 and ICAM-1 were prepared on silica beads and used to stimulate preactivated AND T cells for 3 min. The resulting blots were probed with an antibody against LAT phosphorylated at Y191. Ratios of the intensity of phosphorylated to total LAT are listed below each lane. The blot was cropped to show the band of interest. (H) Average fold change in LAT activation with respect to cells exposed to bilayers containing only ICAM-1 and CD80 for two separate experiments, with error bars representing the mean ± SD. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Scale bar = 2.5 μm. (See also Movies S1-S5)

We next expressed LAT-EGFP in naïve AND T cells and incubated them with lipid bilayers containing β□ 2m-I-Ek, CD80 and ICAM-1. We observed TCR microclusters with which LAT colocalized (Fig. 5A). Additionally, we quantified the number of TCR and LAT-EGFP microclusters in these naïve cells (Fig. 5E) and their colocalization with one another (Fig. 5F) and found that the results were highly similar to activated cells stimulated with β□ 2m-I-Ek. Taken together, these results indicate that the partitioning of LAT into preexisting TCR microclusters is a constitutive property of agonist-naïve T cells and not the result of in vitro activation.

Because LAT was present in TCR microclusters irrespective of pMHC potency, we sought to determine in response to which ligands LAT was being activated. To accomplish this, we prepared artificial APCs presenting agonist or APL-loaded pMHC, CD80, and ICAM-1 and performed Western blots to detect phosphorylation of LAT at position 191 (Y191) (Fig. 5G). As expected, LAT was robustly phosphorylated in response to MCC stimulation. K99A stimulation in the presence of CD80 caused a small amount of LAT phosphorylation, approximately one order of magnitude less than that caused by stimulation with MCC, consistent with its ability to elicit a small calcium flux. We were unable to detect LAT phosphorylation at position 191 in response to all other ligands. The average fold increase in LAT activation for two experiments is presented in Fig. 5H. These results demonstrate that LAT constitutively partitions into TCR microclusters independently of its activation status.

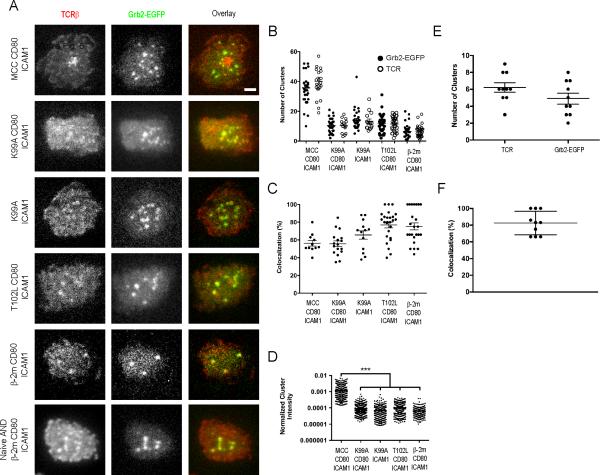

Grb2, an adapter protein containing SH2 and SH3 domains, binds phosphorylated residues on LAT via its SH2 domain. Grb2 bound to phosphorylated LAT can facilitate ERK activation through its interaction with Son of Sevenless (SOS12). In addition to functioning as a RasGEF, SOS1 has been shown to function as a scaffold protein and cause oligomerization of LAT (33). This scaffold function of SOS1 requires its interaction with Grb2. Since we observed reduced TCR-induced ERK activation in response to APL stimulation (Fig. 1B), we questioned if this was a result of reduced Grb2 binding to LAT within TCR microclusters. To address this, we determined the distribution of Grb2 relative to TCR microclusters in response to APLs that did not induce LAT phosphorylation. We transfected preactivated AND T cells with a Grb2-EGFP construct and imaged them as described (Fig. 6A). Like LAT, Grb2 was present in TCR microclusters in response to stimulation by all ligands. As before, we counted the total number of microclusters of TCR and Grb2-EGFP and again found that, for each stimulation condition, the average numbers of TCR and Grb2-EGFP microclusters were roughly equivalent (Fig. 6B) and increased as the potency of the ligand increased. In each case, the signal from TCRβ and Grb2-EGFP strongly colocalized with one another (Fig. 6C and Movies S6-S10). Further, we quantified the fluorescence intensity of the Grb2-EGFP microclusters and found that, with the exception of an order of magnitude increase in response to MCC stimulation, the amount of Grb2 present within a microcluster was not a function of ligand potency (Fig. 6D). Again, similar to CD45 exclusion and LAT partitioning, a basal level of association of Grb2-EGFP with TCR microclusters was independent of T cell activation. In such situations when LAT is not phosphorylated at residues necessary for Grb2 recruitment, Grb2 could be bound via its SH2 domain to several proteins within a TCR microcluster, as it has been shown to interact with proteins such as CD28 (34) and TCRζ□ (35) via its SH2 domain. Alternatively, Grb2 could bind to proline rich regions in other proteins within the microcluster via SH3 domain interactions. To allay concerns relating to artifacts of prior activation of the T cell, we expressed Grb2-EGFP in naïve AND T cells and found a constitutive localization of Grb2-EGFP with preexisting TCR microclusters on these agonist-naïve cells (Fig. 6A). Additionally, we quantified the number of TCR and Grb2-EGFP microclusters in these naïve cells (Fig. 6E) and their colocalization with one another (Fig. 6F) and found that the results were highly similar to activated cells stimulated with β□ 2m-I-Ek. Thus, Grb2 is contained within ligand independent, preexisting TCR microclusters, albeit at levels 10 fold lower than found in TCR microclusters engaging agonist TCR ligands.

Fig. 6. Grb2 Recruitment to TCR Microclusters in Response to APL Stimulation.

(A) Agonist or APL-loaded I-Ek (5 molecules/μm2) were presented to preactivated or naive Grb2-EGFP transfected AND T cells stained with AlexaFluor 546-labeled H57 Fab fragments along with CD80 and ICAM-1 on fluid lipid bilayers. (B) Total TCR microcluster and Grb2-EGFP cluster counts resulting from stimulation of AND T cells as described in (A). For MCC- I-Ek, the cSMAC was excluded from the analysis so that only the number of peripheral microclusters were quantified. (C) Colocalization of TCR and Grb2-EGFP microclusters from (B). Colocalization was calculated as the percentage of TCR microclusters overlapping in area with a Grb2-EGFP cluster by at least 40%. (D) Fluorescence intensity of individual clusters of Grb2-EGFP normalized to the total expression level of Grb2-EGFP in each cell resulting from stimulation of AND T cells as described in (A). Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA test. Unmarked comparisons were not found to be statistically significant. (E) Total TCR microcluster and Grb2-EGFP cluster counts resulting from stimulation of Grb2-EGFP-transfected naïve AND T cells with β-2m-I-Ek. (F) Colocalization of TCR and Grb2-EGFP microclusters from (E). For all panels, error bars represent the mean ± SEM. For (B)-(F), data are pooled from cells that had been in contact with the bilayer substrate for up to one hour. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Scale bar = 2.5 μm. (See also Movies S6-S10)

In conclusion, we found that some TCR microclusters pre-exist in unstimulated T cells. Such microclusters excluded the phosphatase CD45 and were enriched in the signaling adapters LAT and Grb2. The pre-existence of some TCR microclusters at the basal state enriched with signaling molecules may explain the rapid kinetics with which TCR signaling occurs.

Discussion

It is well appreciated that TCR microclusters are sites for active TCR signaling, but a controversy still exists as to how and when they are formed (36). Several lines of evidence now exist that indicate that TCR aggregates of some sort preexist (8, 11-13). We have previously shown that some TCR microclusters could be detected in unstimulated cells, but a full characterization was not carried out (4). In live cells, our data show that TCR microclusters are present on T cells never exposed to agonist ligand. These preexisting microclusters increase in absolute number as the potency of pMHC ligands increases at a fixed antigen dose; however, this increase in absolute number with increasing ligand potency seems to be a consequence of increased cell spreading which exposes more total membrane area. As a consequence, the density of TCR microclusters present on the membrane is not a strong function of antigen potency, either achieved through change in the antigen dose or affinity. Interestingly, the size of a microcluster and the number of TCRs contained within it are also not a function of the pMHC potency. Although we detect a slightly lower intensity for microclusters observed upon stimulation with β-2m, we attribute this result to this ligand's inability to stably engage the microclusters and the probable dynamic nature of the preexisting clusters before they are stabilized through interactions with more potent ligands. This well-defined composition explains our observation that pMHC ligands of very low potency are trapped by TCR microclusters, as binding and rebinding of individual pMHCs within the same microcluster is possible due to the high local concentration of TCR.

Similar to the invariant nature of TCR content within a microcluster, we observed that TCR microclusters present on T cells in the absence of antigen stimulation constitutively excluded the phosphatase CD45. This finding is not consistent with the kinetic segregation model of T cell signaling which holds that the large and heavily glycosylated extracellular domain of CD45 causes its exclusion from TCR microclusters, where long-lived binding of the TCR with pMHC complexes causes the formation of tight junctions between the T cell membrane and APC. T cells expressing chimeric CD45 molecules in which the ectodomain was replaced with the shorter ectodomain of either CD2 or Thy 1 showed dramatic defects in the activation of NFAT (37), and, further, recent imaging studies have shown that CD45 mutants with truncated ectodomains fail to be excluded from TCR microclusters (38). We also considered that the formation of CD28-CD80 interactions in our system could be driving the exclusion of CD45 from TCR microclusters, since CD28 colocalizes with TCR microclusters (6) and the interacting pair could create a tight membrane contact capable of sterically excluding CD45. We ruled out this possibility by demonstrating that CD45 is still excluded from microclusters on cells interacting with bilayers containing only ICAM-1.

We also found that preexisting TCR microclusters contained both LAT and Grb2. Sherman et. al. reported the existence of protein nanostructures at the basal state in which LAT and Grb2 do not colocalize (12). While we find Grb2 and LAT together in the microcluster at the basal state, the optical resolution of our technique does not allow us to make conclusions about their physical association. Given that our data indicate that LAT is not phosphorylated at the residues necessary for Grb2 association, it is likely that Grb2 is interacting with some other proteins that are present in the microcluster at the basal state, as mentioned previously. Importantly, we found that the presence of LAT and Grb2 in preexisting TCR microclusters was not an artifact of previous T cell activation because we observed both in microclusters on naïve AND T cells.

The signaling behavior of T cells in response to K99A, interestingly, stands out from the other ligands studied with respect to its dependence on costimulation by CD80. While there is virtually no variation in the amount pMHC trapping, the total number of microclusters generated, or the amount of ERK activated, the amount of cell spreading, calcium flux and LAT activation are clearly affected when CD80 is not present. When CD80 is present in the bilayer, we believe that CD28 may act to bring the lymphocyte specific protein tyrosine kinase (Lck13) into the microcluster to initiate downstream signaling, as it has been shown to act as a scaffold for Lck (39). When this happens, Lck-dependent phosphorylation events lead to more LAT phosphorylation and additional signals that lead to generation of calcium fluxes.

The mechanisms that drive the formation of the preexisting microclusters that we observe remain elusive, but it is clear that recognition of agonist ligands is not required for their formation since we have shown that TCR microclusters preexist on the surface of naïve T cells that have never seen an agonist ligand. It has been demonstrated that depolymerizing the actin cytoskeleton prevents the formation of TCR microclusters (4, 42), but others have argued that actin is necessary for microcluster maintenance but not formation (13). It is likely, then, that a TCR microcluster is a collection of steady state nanoclusters preassociated with signaling molecules corralled by actin structures. Another possibility is that TCR microclusters are some form of surface-associated endocytic structures. We think that a combination of different cell biological phenomena leads to the formation of these preexisting microclusters and that a single perturbation is unlikely to reveal the precise mechanism of their formation. It is to be noted that there are differences in the composition and physical properties of TCR microclusters observed in response to agonist ligands and those that exist in the unstimulated state. The amount of Grb2 (this report) and ZAP70 (manuscript in preparation) are much higher in TCR microclusters engaging agonist ligands. Microclusters observed in response to APLs exhibit sensitivity to actin depolymerization that is not seen in response to agonist stimulation (30).

Taken together, our results indicate that preexisting TCR microclusters are specialized structures with a well-defined composition. Biochemical reactions occurring in the plasma membrane are often diffusion limited. This preorganized state, in which positive regulators of TCR signal transduction are preassociated but negative regulators are excluded, could compensate for the slow diffusion of interacting components and could facilitate the ability of the TCR to rapidly signal when a high potency pMHC is encountered (7).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Lukszo for peptide synthesis and labeling. We thank J. Kabat for help in processing the supplementary movies. We also thank R. Schwartz, L. Samelson, R. Germain, M. Dustin, J. Yewdell and M. Meier-Schellersheim for critical reading of the manuscript and comments.

Footnotes

This project has been funded by the Intramural Research Program of NIAID, NIH and in part with federal funds from the NCI, NIH, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

pMHC, peptide-loaded major histocompatibility complex

IS, immunological synapse

cSMAC, central supramolecular activation cluster

LAT, linker for activation of T cells

Grb2, growth factor receptor-bound protein 2

APL, altered peptide ligand

MCC, moth cytochrome c

EGFP, enhanced GFP

TIRFM, total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy

β□ 2m,β□ 2microglobulin

SOS, son of sevenless

Lck, lymphocyte specific protein tyrosine kinase

References

- 1.Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM, Dustin ML. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 1999;285:221–227. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monks CR, Freiberg BA, Kupfer H, Sciaky N, Kupfer A. Nature. 1998;Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells.395:82–86. doi: 10.1038/25764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunnell SC, Hong DI, Kardon JR, Yamazaki T, McGlade CJ, Barr VA, Samelson LE. T cell receptor ligation induces the formation of dynamically regulated signaling assemblies. The Journal of cell biology. 2002;158:1263–1275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varma R, Campi G, Yokosuka T, Saito T, Dustin ML. T cell receptor-proximal signals are sustained in peripheral microclusters and terminated in the central supramolecular activation cluster. Immunity. 2006;25:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokosuka T, Sakata-Sogawa K, Kobayashi W, Hiroshima M, Hashimoto-Tane A, Tokunaga M, Dustin ML, Saito T. Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nature immunology. 2005;6:1253–1262. doi: 10.1038/ni1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokosuka T, Kobayashi W, Sakata-Sogawa K, Takamatsu M, Hashimoto-Tane A, Dustin ML, Tokunaga M, Saito T. Spatiotemporal regulation of T cell costimulation by TCR-CD28 microclusters and protein kinase C theta translocation. Immunity. 2008;29:589–601. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huse M, Klein LO, Girvin AT, Faraj JM, Li QJ, Kuhns MS, Davis MM. Spatial and temporal dynamics of T cell receptor signaling with a photoactivatable agonist. Immunity. 2007;27:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schamel WW, Arechaga I, Risueno RM, van Santen HM, Cabezas P, Risco C, Valpuesta JM, Alarcon B. Coexistence of multivalent and monovalent TCRs explains high sensitivity and wide range of response. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:493–503. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle S, Kolin DL, Bieler JG, Schneck JP, Wiseman PW, Edidin M. Quantum Dot Fluorescence Characterizes the Nanoscale Organization of T Cell Receptors for Antigen. Biophys J. 2011;101:L57–L59. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fahmy TM, Bieler JG, Edidin M, Schneck JP. Increased TCR avidity after T cell activation: A mechanism for sensing low-density antigen. Immunity. 2001;14:135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar R, Ferez M, Swamy M, Arechaga I, Rejas MT, Valpuesta JM, Schamel WWA, Alarcon B, van Santen HM. Increased Sensitivity of Antigen-Experienced T Cells through the Enrichment of Oligomeric T Cell Receptor Complexes. Immunity. 2011;35:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman E, Barr V, Manley S, Patterson G, Balagopalan L, Akpan I, Regan CK, Merrill RK, Sommers CL, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Samelson LE. Functional nanoscale organization of signaling molecules downstream of the T cell antigen receptor. Immunity. 2011;35:705–720. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lillemeier BF, Mortelmaier MA, Forstner MB, Huppa JB, Groves JT, Davis MM. TCR and Lat are expressed on separate protein islands on T cell membranes and concatenate during activation. Nature immunology. 2010;11:90–96. doi: 10.1038/ni.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larghi P, Williamson DJ, Carpier JM, Dogniaux S, Chemin K, Bohineust A, Danglot L, Gaus K, Galli T, Hivroz C. VAMP7 controls T cell activation by regulating the recruitment and phosphorylation of vesicular Lat at TCR-activation sites. Nature immunology. 2013;14:723–731. doi: 10.1038/ni.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson DJ, Owen DM, Rossy J, Magenau A, Wehrmann M, Gooding JJ, Gaus K. Pre-existing clusters of the adaptor Lat do not participate in early T cell signaling events. Nature immunology. 2011;12:655–662. doi: 10.1038/ni.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purbhoo MA, Liu H, Oddos S, Owen DM, Neil MA, Pageon SV, French PM, Rudd CE, Davis DM. Dynamics of subsynaptic vesicles and surface microclusters at the immunological synapse. Science signaling. 2010;3:ra36. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balagopalan L, Barr VA, Kortum RL, Park AK, Samelson LE. Cutting edge: cell surface linker for activation of T cells is recruited to microclusters and is active in signaling. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:3849–3853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang J, Brameshuber M, Zeng X, Xie J, Li QJ, Chien YH, Valitutti S, Davis MM. A single peptide-major histocompatibility complex ligand triggers digital cytokine secretion in CD4(+) T cells. Immunity. 2013;39:846–857. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irvine DJ, Purbhoo MA, Krogsgaard M, Davis MM. Direct observation of ligand recognition by T cells. Nature. 2002;419:845–849. doi: 10.1038/nature01076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sloan-Lancaster J, Allen PM. Altered peptide ligand-induced partial T cell activation: molecular mechanisms and role in T cell biology. Annual review of immunology. 1996;14:1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crites TJ, Chen L, Varma R. A TIRF microscopy technique for real-time, simultaneous imaging of the TCR and its associated signaling proteins. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2012 doi: 10.3791/3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dustin ML, Starr T, Varma R, Thomas VK. Coligan John E., editor. Supported planar bilayers for study of the immunological synapse. Current protocols in immunology. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1813s76. [et al.] Chapter 18: Unit 18 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn KW, McGraw TE, Maxfield FR. Iterative fractionation of recycling receptors from lysosomally destined ligands in an early sorting endosome. The Journal of cell biology. 1989;109:3303–3314. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veenman CJ, Reinders MJT, Backer E. Resolving motion correspondence for densely moving points. Ieee T Pattern Anal. 2001;23:54–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marrack P, Ignatowicz L, Kappler JW, Boymel J, Freed JH. Comparison of peptides bound to spleen and thymus class II. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1993;178:2173–2183. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krogsgaard M, Li QJ, Sumen C, Huppa JB, Huse M, Davis MM. Agonist/endogenous peptide-MHC heterodimers drive T cell activation and sensitivity. Nature. 2005;434:238–243. doi: 10.1038/nature03391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cemerski S, Das J, Locasale J, Arnold P, Giurisato E, Markiewicz MA, Fremont D, Allen PM, Chakraborty AK, Shaw AS. The stimulatory potency of T cell antigens is influenced by the formation of the immunological synapse. Immunity. 2007;26:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers PR, Grey HM, Croft M. Modulation of naive CD4 T cell activation with altered peptide ligands: the nature of the peptide and presentation in the context of costimulation are critical for a sustained response. Journal of immunology. 1998;160:3698–3704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skokos D, Shakhar G, Varma R, Waite JC, Cameron TO, Lindquist RL, Schwickert T, Nussenzweig MC, Dustin ML. Peptide-MHC potency governs dynamic interactions between T cells and dendritic cells in lymph nodes. Nature immunology. 2007;8:835–844. doi: 10.1038/ni1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vardhana S, Choudhuri K, Varma R, Dustin ML. Essential role of ubiquitin and TSG101 protein in formation and function of the central supramolecular activation cluster. Immunity. 2010;32:531–540. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babich A, Li S, O'Connor RS, Milone MC, Freedman BD, Burkhardt JK. F-actin polymerization and retrograde flow drive sustained PLCgamma1 signaling during T cell activation. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;197:775–787. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201201018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balagopalan L, Barr VA, Sommers CL, Barda-Saad M, Goyal A, Isakowitz MS, Samelson LE. c-Cbl-mediated regulation of LAT-nucleated signaling complexes. Molecular and cellular biology. 2007;27:8622–8636. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00467-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kortum RL, Balagopalan L, Alexander CP, Garcia J, Pinski JM, Merrill RK, Nguyen PH, Li W, Agarwal I, Akpan IO, Sommers CL, Samelson LE. The Ability of Sos1 to Oligomerize the Adaptor Protein LAT Is Separable from Its Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Activity in Vivo. Science signaling. 2013;6:ra99. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider H, Cai YC, Prasad KV, Shoelson SE, Rudd CE. T cell antigen CD28 binds to the GRB-2/SOS complex, regulators of p21ras. European journal of immunology. 1995;25:1044–1050. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Methi T, Ngai J, Vang T, Torgersen KM, Tasken K. Hypophosphorylated TCR/CD3zeta signals through a Grb2-SOS1-Ras pathway in Lck knockdown cells. European journal of immunology. 2007;37:2539–2548. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie J, Tato CM, Davis MM. How the immune system talks to itself: the varied role of synapses. Immunological reviews. 2013;251:65–79. doi: 10.1111/imr.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irles C, Symons A, Michel F, Bakker TR, van der Merwe PA, Acuto O. CD45 ectodomain controls interaction with GEMs and Lck activity for optimal TCR signaling. Nature immunology. 2003;4:189–197. doi: 10.1038/ni877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cordoba SP, Choudhuri K, Zhang H, Bridge M, Basat AB, Dustin ML, van der Merwe PA. The large ectodomains of CD45 and CD148 regulate their segregation from and Inhibition of ligated T-cell receptor. Blood. 2013 doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-442251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong KF, Yokosuka T, Canonigo-Balancio AJ, Isakov N, Saito T, Altman A. A motif in the V3 domain of the kinase PKC-theta determines its localization in the immunological synapse and functions in T cells via association with CD28. Nature immunology. 2011;12:1105–1112. doi: 10.1038/ni.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang Y, Cheng H. Evidence of LAT as a dual substrate for Lck and Syk in T lymphocytes. Leukemia research. 2007;31:541–545. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rouquette-Jazdanian AK, Sommers CL, Kortum RL, Morrison DK, Samelson LE. LAT-independent Erk activation via Bam32-PLC-gamma1-Pak1 complexes: GTPase-independent Pak1 activation. Molecular cell. 2012;48:298–312. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campi G, Varma R, Dustin ML. Actin and agonist MHC-peptide complex-dependent T cell receptor microclusters as scaffolds for signaling. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2005;202:1031–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.