Abstract

This study sought to investigate the efficacy of a noninvasive and long acting polymeric particle based formulation of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1), a potent pulmonary vasodilator, in alleviating the signs of pulmonary hypertension (PH) and reversing the biochemical changes that occur in the diseased lungs. PH rats, developed by a single subcutaneous injection of monocrotaline (MCT), were treated with two types of polymeric particles of PGE1, porous and nonporous, and intratracheal or intravenous plain PGE1. For chronic studies, rats received either intratracheal porous poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) particles, once- or thrice-a-day, or plain PGE1 thrice-a-day for 10 days administered intratracheally or intravenously. The influence of formulations on disease progression was studied by measuring the mean pulmonary arterial pressure (MPAP), evaluating right ventricular hypertrophy and assessing various molecular and cellular makers including the degree of muscularization, platelet aggregation, matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Both plain PGE1 and large porous particles of PGE1 reduced MPAP and right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) in rats that received the treatments for 10 days. Polymeric porous particles of PGE1 produced the same effects at a reduced dosing frequency compared to plain PGE1 and caused minimal off-target effects on systemic hemodynamics. Microscopic and immunohistochemical studies revealed that porous particles of PGE1 also reduced the degree of muscularization, von Willebrand factor (vWF) and PCNA expression in the lungs of PH rats. Overall, our study suggests that PGE1 loaded inhalable particulate formulations improve PH symptoms and arrest the progression of disease at a reduced dosing frequency compared to plain PGE1.

Keywords: Prostaglandin E1, Pulmonary hypertension, Monocrotaline, Controlled release, PLGA microparticles

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a progressive and devastating disorder of the pulmonary circulation, which is characterized by a mean pulmonary arterial pressure (MPAP) of >25 mm Hg at rest and an increased pulmonary vascular resistance1,2. PH results from an imbalance among various mediators responsible for maintaining the low tone of the pulmonary arteries. The mediators involved in this counter-regulatory mechanism include prostacyclin, nitric oxide, natriuretic peptides, thromboxane, endothelin-1, serotonin and cytokines. The first three agents act as vasodilators and the last four as vasoconstrictors in the pulmonary circulation3. Both genetic and external factors may perturb these opposing regulatory mechanisms for maintaining pulmonary vascular tone, leading to a series of abnormalities, including vasoconstriction, smooth muscle and endothelial cell proliferation, and in-situ thrombosis in pulmonary vasculature. These abnormalities cause narrowing and occlusion of the peripheral pulmonary arteries, resulting in hypertension and increased afterload on the right ventricle, which ultimately leads to right heart failure and death. The major signaling pathways involved in the development of PH are endothelin, nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and recently proposed Rho-kinase pathways. These pathways have been the basis for development of the currently used four categories of anti-PH drugs that include prostacyclin analogs, endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs), nitric oxide (NO) and phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors 4,5.

Of these four categories of drugs, the prostacyclin analogs–epoprostenol, treprostinil and iloprost–are the first-line therapeutic agents for severe PH 6. However, use of this class of drugs is plagued by problems of stability, inconvenient method of administration and overall safety7,8. Because of their short half-lives, prostacyclin analogs, with the exception of iloprost and treprostinil, have been administered using indwelling central catheters or subcutaneous infusions. In addition to invasive routes of administration, instability of drug formulations, lack of pulmonary selectivity, requirement of permanent dose escalation and multiple inhalations a day are considered as major limitations of current prostacyclin analog based treatment of PH9. Further, a recent meta-analysis of 23 randomized controlled trials of three categories of anti-PH drugs–prostacyclin analogs, ERAs and PDE-5 inhibitors–shows that while current treatment achieves moderate improvement in symptoms, hemodynamics and survival, the patient morbidity and mortality rate remain unacceptably high10. In fact, recent national registry data from France and the United States reiterates that PH related mortality continues to rise11,12. This disappointing outcome propelled the studies for development of new pulmonary selective vasodilators1,13 and drug-delivery systems7 that can provide sustained and localized delivery to the lungs14–16.

Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1), a series-1 endogenous prostacyclin, exhibits potent vasodilatory, anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and platelet aggregation inhibitory properties17–20. PGE1 is FDA approved for the treatment of erectile dysfunction (Caverject®, Muse®) and ductus arteriosus (Prostin® VR). Further, it has been studied for its potential use in the treatment of PH and other respiratory disorders21–24. However, similar to commercially available prostacyclins, PGE1 suffers from the disadvantage of short half-life of 3–5 minutes25,26. Although this drug is not commercially available for the treatment of PH, the biological and chemical properties of PGE1 closely resemble those of currently available prostacyclin analogs. Thus, in our previous studies, we have used PGE1 as an alternative to expensive commercially prostacyclin analogs. We have shown that the circulation half-life of PGE1 can be increased by formulating it in poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) based particles14–16. We have also demonstrated that PGE1 loaded PLGA particles produce a continuous release of the drug upon intratracheal administration to anesthetized rats. These observations are consistent with earlier findings demonstrating that polymeric large porous particles of >5µm in size and density of <0.4 g/cm3 escape lungs’ clearance mechanisms, facilitate deposition of the dosage form in distal regions of the lungs27. A metabolic stability study also revealed that PGE1 encapsulated in PLGA particles was protected from degradation by metabolizing enzymes present in the lungs15,16. While PLGA particles showed favorable pharmacokinetic and metabolic stability profiles upon intratracheal administration to healthy rats, we do not know whether these formulations will reduce MPAP and provide selective protection against pulmonary vascular remodeling and PH progression. With the above feasibility studies in hand, we have designed this study to investigate the pharmacological efficacy of our already established polymeric formulations in an animal model of PH. We tested these formulations in monocrotaline (MCT) induced PH rats and conducted both acute and chronic studies to evaluate the pharmacological efficacy of the formulations. Following intravenous and intratracheal administration of either plain drug or polymeric formulations, we measured MPAP, performed detailed morphometric studies and evaluated various biochemical and cellular markers in PH lungs. The results of our studies provide insight into controlled release particulate carriers encapsulating PGE1, an orphan drug, for developing an effective and patient compliant therapy for PH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of the Polymeric Particles of PGE1

PGE1 encapsulated particles were prepared by a double emulsion/solvent evaporation method as described in our recent studies15,16. PLGA 85:15 with an inherent viscosity of 0.55–0.75 dL/g (average molecular weight 85.2 kDa) was used to prepare porous and nonporous particles. For porous particles, polyethyleneimine (PEI) was used as a core-modifying agent14. Both formulations were evaluated for particle size and drug entrapment efficiency as reported in our published studies16 .

Hemodynamic Studies in MCT-induced PH Rats

All experiments were performed using adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (250–300 g, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). PH was induced by a single subcutaneous injection of MCT (50 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 0.1N HCl and adjusted to pH 7.4 with 0.1N NaOH, as described previously 28. All animals were housed at TTUHSC Vivarium in Amarillo for 28 days with free access to food and water for developing PH symptoms. All studies were performed in accordance with NIH Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under a protocol approved by Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) Animal Care and Use Committee (AM-10012).

Upon development of PH, 4 weeks after injection of MCT, animals were divided into two major groups for acute and chronic studies. For acute studies, 30 PH rats were divided into five sub groups containing 6 rats in each group to receive the following treatments: (i) normal saline (0.9% NaCl) intratracheal, (ii) plain intravenous PGE1, (iii) plain intratracheal PGE1, (iv) nonporous and (v) porous PLGA particles of PGE1 administered intratracheally. The dose administered was 120 μg/kg of plain PGE1 or PLGA particles equivalent to 120 μg/kg of PGE1.

Similar to acute studies, for chronic studies, five groups of PH rats (n =6) received following treatments for 10 days: (i) saline intratracheal (ii) plain intravenous PGE1 administered every 8 hours thrice-a-day (t.i.d.), (iii) plain intratracheal PGE1 administered t.i.d., (iv) porous PLGA particles of PGE1 administered t.i.d. intratracheally and (v) and porous PLGA particles of PGE1 administered once a day (s.i.d.) intratracheally. The sixth group was PH rats with no treatment. One more group, the seventh group, was used as sham group consisting of healthy rats with no treatments. Thus, all rats, except those in the first, sixth and seventh group, received 120 μg/kg of plain PGE1 or PLGA particles equivalent to 120 μg/kg. The total dose of PGE1 for t.i.d. and s.i.d was 360 and 120 µg/kg respectively. Further, in chronic studies we used only porous PLGA particles of PGE1 because these particles showed prolonged pulmonary vasodilation upon acute single dose studies in MCT induced PH rats.

Hemodynamic Measurements

For hemodynamic measurements, MPAP and mean systemic arterial pressure (MSAP) were determined by using PowerLab 16/30 with LabChart Pro 7.0 software (ADInstruments, Inc., Colorado Springs, CO). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of a cocktail of ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Before administration of the formulations, right carotid and pulmonary arteries were catheterized with PE-50 (BD Intramedic™, Sparks, MD) and PV-1 (Tygon®, Lima, OH) catheters, respectively. First, right jugular vein was exposed by a 2–3 cm incision over the thoroughly shaved and sterilized right ventral neck area and kept separated from the chest using a suture. Then the right carotid artery was surgically exposed and a PE-50 catheter was inserted 3–4 cm into the artery and secured with sutures for measurement of MSAP. For pulmonary artery catheterization, a PV-1 catheter with top end curved at 60–65° angle29 was inserted into the pulmonary artery via the right internal jugular vein and right ventricle and secured with a suture. Upon catheterization, MPAP and MSAP were measured using Memscap SP844 physiological pressure transducers (Memscap AS, Scoppum, Norway) and bridge amplifiers connected to the PowerLab system. Correct positioning of the PV-1 catheter was confirmed from characteristic peaks of the pulmonary arterial pressure tracings captured by PowerLab system as reported previously30.

For acute and chronic studies, intravenous administrations were performed via the penile and sublingual veins, respectively. Pulmonary administrations were performed via the intratracheal route using a microsprayer (Penn-Century® MicroSprayer, Philadelphia, PA) as described earlier14–16. All the procedures were performed under anesthesia including visualization of trachea by laryngoscope and administration of drug/formulation to the lungs. For both intravenous and intratracheal administrations, formulations were prepared freshly in sterile saline (pH 7.0). For acute studies, the hemodynamic measurements were performed soon after administration of the formulation but for chronic studies, measurements were performed on day 11. In acute studies, MSAP and MPAP were monitored until the pulmonary arterial pressure returned to the baseline value observed at time zero whereas for chronic studies, hemodynamic measurements were performed up to 30 minutes following catheter insertion. The hemodynamics of PH rats was first measured on day 28, whereas that for both saline and active treatment (plain PGE1 and particles) groups was measured at the end of 38 days (28+10 days). Since symptoms of MCT induced PH worsen with time, rats treated with saline, 38-day after MCT injection, were used as a control instead of rats 28-day post MCT exposure.

Preparation of Lungs and Heart Tissue Samples

Upon completion of hemodynamic measurements, the animals were sacrificed by exsanguination and the chest was opened to expose the heart and lungs. First, the right lung was removed, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for later use to measure the levels of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). The heart and left lung were then removed en bloc from the body following inflation fixation of the lungs with formalin under 30 cm H2O pressure30 and stored in paraformaldehyde for 1 day. The heart was then removed from the block and used for the measurement of right ventricular hypertrophy. The left lung was used in immunostaining and morphometric studies to determine the extent of muscularization of the arteries and measure the medial wall thickness as described below.

Right Ventricular Hypertrophy Measurements

For determination of right ventricular hypertrophy, weight ratio of right ventricle to left ventricle plus septum was determined (RV/LV+S). Briefly, as described above, the heart was removed from the animal following hemodynamic measurements, the atria and the great vessels were detached to isolate the ventricles. Right ventricle was carefully isolated from left ventricle keeping the septum attached to the left ventricle and weighed to calculate RV/LV+S. All measurements were performed by the same investigator without the knowledge of the sample being analyzed.

α-Smooth Muscle Actin (α-SMA)/von-Willebrand (vWF) Staining of Lung Sections for Determination of Degree of Muscularization and Medial Wall Thickness

Left lungs were inflation fixed with formalin, embedded in paraffin and then sectioned to a thickness of 5 µm by a using Microm HM325 rotary microtome (Thermo Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI). The lung sections thus prepared were immunostained with mouse monoclonal α-smooth muscle actin antibody (α-SMA; 1:100-, Clone 1A4) and rabbit polyclonal vWF antibody (1:500) as described previously31. Briefly, lung sections were deparaffinized with citrisolve and rehydrated in graded ethanol. Slides were boiled in antigen unmasking solution (Vector laboratories, H-3300, Burlingame, CA) for 10 minutes and blocked using 2.5% horse serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The primary antibody master mix was applied and left overnight. The following day, sections were treated with secondary antibodies Alexa 594 fluorescent anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:500; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Alexa 488 fluorescent anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200; Invitrogen). Nuclei were counterstained with 4'6-diamidino-2-pheylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and slides were analyzed at 200X using Zeiss Axiovert S100 microscope (Carl Zeiss microscopy LLC, Thornwood, NY, USA). Images were analyzed using AxioVision computer program for determination of degree of muscularization and measurement of medial wall thickness. We analyzed 8–10 images for each lung (n=4–6 animals) and one representative photomicrograph (out of more than 300 images) was presented in the manuscript.

To determine the degree of muscularization, vessels <100 µm with positive α-SMA cell staining surrounding endothelial cells were identified and classified as (i) fully muscularized (100–75%) and partially muscularized (<75%). Vessels with no positive α-SMA staining were classified as “non-muscularized”. The degree of muscularization was expressed as % ratio of number of fully muscularized to the number of total vessels.

For measurement of medial wall thickness (MWT), in each lung section, we analyzed 10 muscularized arteries that were <50 µm in size. Four perpendicular lumen radius and medial wall measurements were taken for each vessel by an investigator blinded to the experimental group. MWT was expressed as the ratio of the average medial wall thickness divided by the average vessel radius.

Evaluation of Collagen Deposition

To visualize collagen deposition in the MCT treated animal lungs, trichrome staining was performed according to our published method 31. Trichrome stains the collagen in blue color which can be easily visualized. For Masson Trichrome staining, slides were deparaffinized through 3 changes of xylene for 5 minutes each, 2 changes of 100% EtOH for 5 minutes each and 2 changes of 95% EtOH for 5 minutes each. Following deparaffinization, slides were rinsed in deionized water, placed in pre-warmed 60°C Bouins solution (picric acid saturated aqueous solution, 37–40% formaldehyde, glacial acetic acid) for 20 minutes; rinsed with tap water and then placed in Weigert’s Hematoxylin for 10 minutes. Following rinsing in tap water, the slides were placed in Acid Fuchsin-Ponceau solution for 2 minutes, rinsed lightly with deionized water, differentiated in 1% phosphotungstic acid for 2 minutes, placed directly into aniline blue solution for 2 minutes, rinsed quickly with tap water and then dehydrated with alcohol and cleared in xylene and coverslipped. Visual analysis of the stained sections was performed by a blinded investigator as described elsewhere 31.

Gelatin Zymography

Gelatin zymography studies were performed to determine the effects of microparticulate formulations on levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9, two important markers of PH. For zymography studies, portions of flash-frozen lungs were homogenized in PBS without protease inhibitors at a concentration of 50 mg/ml using a glass homogenizer. The homogenate thus obtained was centrifuged at 4,000 ×g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was measured by BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnologies, Rockford, IL). A total of 15 μg protein, mixed with an equal volume of SDS loading buffer (without reducing agent or heating), was loaded on a 10% polyacrylamide-gelatin Novex Zymogram minigel (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Briefly, after loading the samples, gels were run at constant 125 V for 90 minutes (30–40 mA current) using Mini-Protean II Cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Gels were developed using Novex® Zymogram Renaturing and Developing buffers and incubated at 37°C overnight. Following incubation, gels were stained with SimplyBlue® Safestain (Invitrogen, Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), which revealed areas of protease activity as clear bands against a dark background. MMP controls were used to determine the bands of MMP-2 and -9 (R&D Systems, Inc. Minneapolis, MN). The developed gel was scanned and the scanned image was quantified using Un-Scan-IT image processing software (Silk Scientific, Inc., Orem, UT).

Assay of Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen

The levels of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a proliferation marker found in the nuclei of highly proliferating cells, were determined by western blot analysis. The lung samples collected from MCT-induced rats from chronic treatment groups were homogenized and loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE gel (Pierce Protein Gels, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) at 30 µg protein/well under reduced conditions using Mini-Protean II Cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Mouse anti-PCNA IgG antibody (1:5000 dilution; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA; AB29) was used to detect PCNA followed by incubation with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) coupled secondary antibody (Rabbit anti-mouse IgG, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA; AB7075). The bands were visualized upon treating the membrane with a chemiluminescent reagent (Biorad Inc., Hercules, CA). β-actin was used as a loading control. The developed gel was scanned and the image was quantified as described above for the PCNA/ β-actin ratio.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SE and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis using Graphpad Prism 5.0 software. Significance was defined as p value < 0.05.

RESULTS

PLGA particles of Prostaglandin E1 (PGE1)

Similar to previously published studies14,15, freshly prepared particles were characterized for particle size and entrapment efficiency prior to use. The encapsulation efficiency of newly prepared nonporous particles was 60% (11.8±0.7 µg PGE1/mg particles) and that for porous particles was 85% (16.6±0.6 µg PGE1/mg particles), which is consistent with the particles used in earlier studies. Based on the characterization data of freshly prepared particles, we assume that these particles will release the drug in lungs for an extended period of time and produce prolonged pulmonary vasodilation.

Acute Hemodynamic Effects

Acute hemodynamic studies evaluated the efficacy of PLGA particles in reducing MPAP following administration of a single dose of plain PGE1 or PLGA particles of PGE1 to MCT induced PH rats. Plain PGE1 administered via the intravenous and intratracheal route produced a significant reduction in MPAP; intravenous PGE1 caused a ~35% reduction in MPAP that lasted for 35–40 minutes, while plain PGE1 resulted in a sustained pulmonary vasodilation with about 32% reduction in MPAP. However, similar to intravenous PGE1, vasodilatory effects of intratracheal plain PGE1 weaned off in 45–50 minutes (Fig.1A). Intratracheal plain PGE1 produced a ≈35% reduction in MSAP (Fig.1B), which was about 20% less than that produced by intravenous PGE1 (p<0.05). However, when optimized nonporous PLGA particles of PGE1 were administered to MCT induced PH rats via the intratracheal route, a significant reduction in MPAP was observed (~58%) and it returned to the baseline in ~2 h. Similarly, large porous particles also demonstrated ~49% reduction in mean MPAP when administered intratracheally and the duration of pulmonary vasodilator effect lasted for 3 h (Fig.1C). MSAP data presented in Fig.1D suggest that both nonporous and porous particles based formulations showed pulmonary preferential vasodilation compared to plain PGE1 administered as intravenous injection. However, no significant differences in MSAP reduction were observed between plain PGE1 and particulate formulations of PGE1, which can be attributed to initial burst release of surface associated drug as shown in our previously published articles 14,15. The duration of pulmonary vasodilatory effects, calculated at 15% reduction in MPAP as the baseline, suggest that both formulations cause reduction in MPAP for 120 to 200 minutes, which were three to four folds longer than the plain drug administered as intravenous injection or aerosols (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Acute pulmonary hemodynamic efficacy of plain PGE1 administered either intravenously (IV) or intratracheally (IT), and particulate formulations of PGE1 administered IT: (A) mean pulmonary arterial pressure (MPAP) after administration of plain PGE1, and (B) mean systemic arterial pressure (MSAP) after administration of plain PGE1. (C) MPAP after intratracheal administration PGE1 encapsulated in porous and nonporous particles, and (D) MSAP after intratracheal administration of PGE1 encapsulated in porous and nonporous particles. (E) Duration of pulmonary vasodilatory effects (minutes) of plain PGE1 and PGE1 loaded particles. Data represent mean±SD (n = 4–6). *Means are significantly different (p<0.05). In Fig.1A and B, plain PGE1 IV has been compared with plain PGE1 pulmonary. In Fig.1C and D, data for large porous particles have been compared with nonporous particles and in Fig.1E, vasodilatory effect of large porous particles has been compared with plain PGE1 pulmonary and nonporous particles.

Chronic Hemodynamic Effects

For long-term efficacy studies, we chose large porous particles that showed pulmonary vasodilatory effects for ~3 hours in acute hemodynamic studies discussed above. Compared to PH rats that received no treatment or saline, a two-fold reduction in MPAP was observed when PGE1 was administered intravenously to PH rats (Fig 3A). MPAP for saline treated rats was 46.82±4.19 mm Hg and that for intravenous plain PGE1 was 21.39±3.15 mm Hg. Similar reduction in MPAP was observed with intratracheal plain PGE1 26.92±4.75 mm Hg. More importantly, large porous particulate formulations administered intratracheally thrice-a-day produced a significant reduction in MPAP (31.31±2.33 mm Hg) compared to saline treated PH rats. Although there were no statistically significant differences between MPAPs observed in PH rats treated with thrice-a-day dose of plain PGE1 and porous particles containing PGE1, once-a-day dose of porous particles demonstrated a remarkable reduction in MPAP values (17.63±5.53 mm Hg) which was comparable with MPAP values of healthy animals (sham group). Once-a-day dosing of particles caused about 50% reduction in MPAP as compared to thrice-a-day dosing. However, the differences between the MSAP values obtained following administration of intravenous and intratracheal plain PGE1 or porous particles were not statistically significant when compared with sham, PH rats or saline treated PH rats (Fig.2B).

Figure 3.

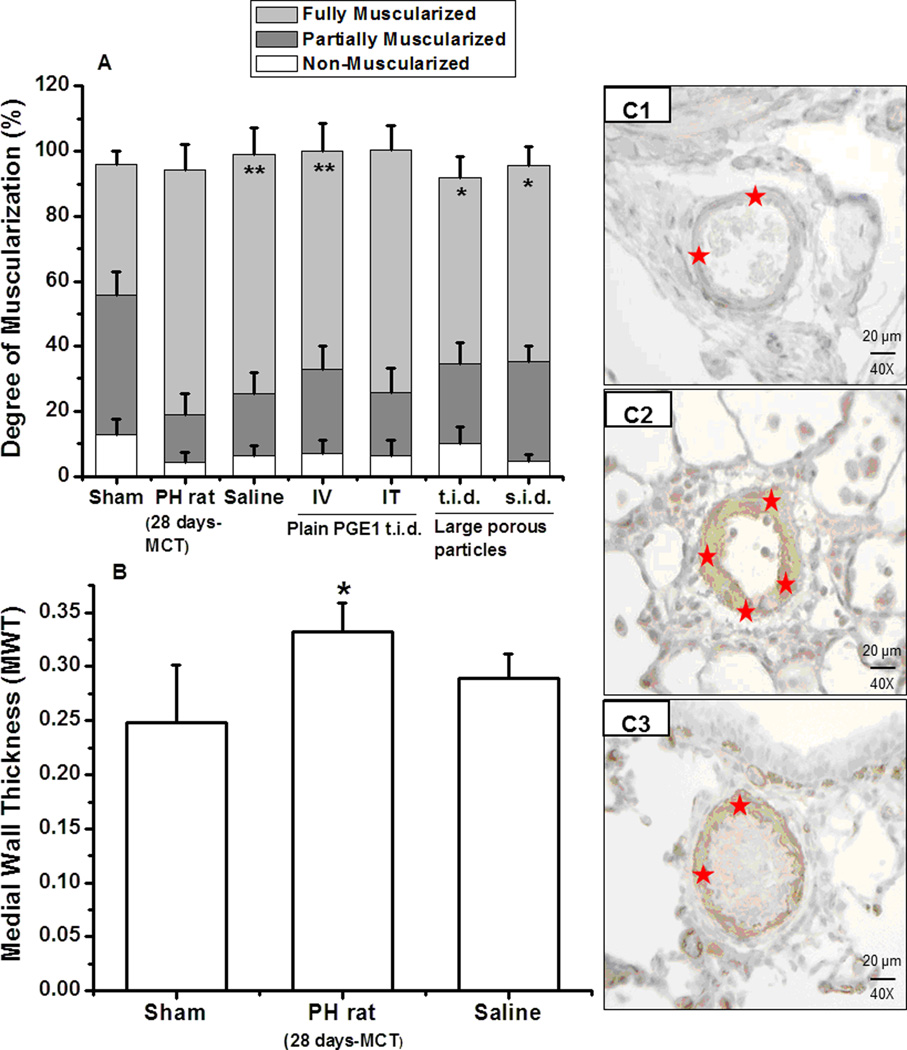

Effect of the once- and thrice-a-day dosing of the formulations on the degree of muscularization and medial wall thickness (MWT): (A) Degree of muscularization of peripheral pulmonary arteries (<100 µm). Percentages of non-muscularized, partially muscularized and fully muscularized arteries are presented. 10 intraacinar vessels were analyzed in each lung section. Data represent mean ± SEM (n = 4–6 animals). *p<0.05 vs saline, **p<0.05 vs sham control. (B) MWT of pulmonary arteries (<50 µm) in sham, and PH rat and saline treated PH rats. Data represent mean±SEM (n = 4–6). *p<0.05 vs sham rats. (C) Representative photomicrographs of lung sections used for determining MWT, (C1) sham, (C2) PH rat, and (C3) saline treated PH rats (* denotes muscularization sites on arteries).

Figure 2.

Chronic pulmonary hemodynamic efficacy of plain PGE1 administered thrice-a-day (t.i.d.) either intravenously (IV) or intratracheally (IT) and particulate formulation administered IT either t.i.d. or once-a-day (s.i.d): (A) Mean pulmonary arterial pressure (MPAP), (B) Mean systemic arterial pressure (MSAP), and (C) Right ventricular hypertrophy denoted by RV/LV+S ratio. Data represent mean±SD (n = 4–6). *Means are significantly different (p<0.05 vs PH rats and saline treated PH rats).

Right Ventricular Hypertrophy

To determine the protective effects of particulate formulations of PGE1 on PH vasculopathy, the extent of right ventricular hypertrophy was determined by calculating RV/LV+S ratio. Four weeks after injection of MCT, RV/LV+S ratio increased from 0.32±0.078 for sham animals to 0.649±0.069 in PH rats (Fig.2C), which clearly indicates that PH rats developed significant right ventricular hypertrophy. Rats receiving saline treatment for 10 more days, showed further progression of right ventricular hypertrophy as observed by an increase in RV/LV+S ratio from 0.649±0.06 to 0.752±0.14. In rats treated with intravenous and intratracheal plain PGE1, RV/LV+S ratio went down to 0.403±0.108, and 0.369±0.104 respectively. Compared to saline treated rats, intratracheally administered particulate formulation caused reduction in RV/LV+S ratio, which was 0.388±0.105 for once-a-day and 0.536±0.022 for thrice-a-day.

Histopathological Evaluation Following Chronic Treatment

Degree of Muscularization

Degree of muscularization was determined by visualizing α-SMA stained blood vessels <100 µm in diameter, in sections of lungs that had been both inflation and perfusion fixed with formalin. MCT treatment resulted in increase in the number of fully muscularized blood vessels; 40.31±4.22% of blood vessels was fully muscularized in control animals32, which increased to 73.75±7.91% in saline treated PH rats (Fig.3A). Chronic treatment with aerosolized PGE1 loaded particles, both t.i.d and s.i.d. dose group, resulted in reduction in the number of fully muscularized vessels (57.38±6.71% with t.i.d. particles and 60.36±5.77% with s.i.d.), whereas aerosolized plain PGE1 did not show any major improvement in muscularization (74.66±7.68%).

Medial Wall Thickening

Pulmonary artery medial wall thickness (MWT) was measured in blood vessels with <50 µm in diameter in lung sections. An increase in MWT was observed 28 days after MCT injection, which started to resolve after 10 days of treatment with saline (Fig.3B). Saline treated animals showed MWTs similar to that observed in sham animals (p = 0.06). These data suggest that MWT measurements of blood vessels <50 µm diameter may not be an appropriate endpoint to study the influence of the drug in pulmonary arterial remodeling. Thus MWT values observed in PH lungs treated with plain drug or formulations are not presented in this manuscript. Representative micrographs of the lung sections used for determining MWT are presented in Fig.3C.

Adventitial Collagen Deposition

Trichrome staining was performed to evaluate the extent of collagen deposition in muscularized pulmonary arteries followed by a qualitative evaluation of lung sections collected from PH rats that received various treatments. The deposition of collagen increased in the distal pulmonary arterioles 4 weeks after treatment with MCT (Fig. 4B) and the extent of deposition further intensified in saline treated PH rats (Fig. 4C). However, the amount of collagen in pulmonary arteries was reduced in rats treated with aerosolized plain PGE1 (Fig. 4E). Rats treated with once-a-day dose of porous particles demonstrated a dramatic decrease in collagen deposition in lung sections (Fig. 4G).

Figure 4.

Efficacy of PGE1 and inhaled porous particles in reducing adventitial collagen deposition in small pulmonary arteries was evaluated in MCT-induced PH rats. Representative photomicrographs of lung sections with trichrome staining demonstrating collagen deposition in arteries in blue color are shown here. (A) sham control, (B) PH rat, (C) saline, (D) I.V. PGE1 (120 µg/kg) t.i.d, (E) intratracheal PGE1 (120 µg/kg) t.i.d., (F) intratracheal large porous particles (120 µg/kg) t.i.d.; and (G) intratracheal large porous particles (120 µg/kg) s.i.d. Pulmonary arteries are indicated by arrows in photomicrographs and by intermittent residual blood deposits in arterial lumen. 8–10 images were analyzed for each lung (n = 4–6 animals).

Vascular Endothelium Damage and Increased Risk of Thrombosis/Platelet Aggregation

We evaluated the protective effects of the formulations by measuring the expression of vWF. As can be seen in Fig. 5B, exposure to MCT increased vWF expression compared to sham animals (Fig. 5A). Saline treatment for 10 days further aggravated vWF expression, and thus the possibility of in-situ thrombosis development. Aerosolized PGE1, when administered as a plain drug or in the form of formulation, significantly reduced vWF accumulation in small pulmonary arteries (red fluorescence in Figs. 5D–5G). Rats treated with once-daily dose of particles showed further reduction in accumulation of vWF in vascular endothelium of pulmonary arterioles (Fig. 5G).

Figure 5.

Influence of plain PGE1 and intratracheal (IT) large porous particles on reducing vascular endothelial damage and risk of platelet aggregation was assessed by fluorescent staining for α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; green) and von Willebrand factor (vWF; red). Representative fluorescent photomicrographs of lung sections demonstrating reduced vWF expression in pulmonary vascular walls: (A) sham control, (B) PH rat, (C) saline, (D) IV plain PGE1 (120 µg/kg) t.i.d, (E) IT plain PGE1 (120 µg/kg) t.i.d, (F) IT large porous particles (120 µg/kg) t.i.d., and (G), IT large porous particles (120 µg/kg) s.i.d. Pulmonary arteries are indicated by arrows in photomicrographs and by intermittent residual blood (red) deposits in arterial lumen. 8–10 images were analyzed for each lung (n = 4–6 animals).

Matrixmetalloproteinase (MMP-2 and -9) Activity

MMP-2 activity in lungs of MCT-treated rats was observed as a triplet of 66, 62, and 59 kDa, with 62 kDa being the predominant form (Fig. 6A). The activity of MMP-2 decreased with PGE1 treatment compared to saline treated groups. Particulate formulation showed comparable effects in reducing MMP 2 activity (Fig. 6B). Lungs from once-a-day porous particles were not analyzed for MMP-2 activity due to lack of frozen samples. However, we did not see a significant difference in MMP-9 expression with MCT treatment (Fig. 6A), and hence MMP-9 was not considered as a convincing end-point for our studies.

Figure 6.

Influence of plain PGE1 and large porous particles on matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity and expression proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): (A) representative zymographs for MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity, (B) densitometric quantification of MMP-2, (C) representative western blots for PCNA, and (D) densitometric quantitation of PCNA. All western blot data were normalized to β-actin. All assays are representative of 3 gels from each group. *p<0.05 against saline treatment to PH rats for 10 days.

Cell Proliferation

The extent of cell proliferation was evaluated by determining the amount of PCNA by western blot analysis. Representative blots (Fig. 6C) and bar graphs summarizing PCNA/β-actin ratio (Fig. 6D) suggest that the amount of PCNA significantly increased in PH rats (0.9±0.12 for no treatment and 1.05±0.2 for saline treatment) groups as compared to sham control (0.6±0.072). PGE1 treatment produced a significant reduction in PCNA levels: the values of PCNA/β-actin ratio for intravenous PGE1, aerosolized PGE1, particles thrice-a-day and particles once-a-day were 0.73±0.1, 0.85±0.21, 0.81±0.06 and 0.85±0.16, respectively (Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to establish the proof-of-principle that aerosolized polymeric particles of PGE1 can be used as an alternative to currently approved prostacyclin analogs based therapy for PH. Previously, we have shown that it is feasible to encapsulate PGE1 in nonporous and porous PLGA particles and the formulations were suitable for intratracheal administration. Of the various polymeric particles, large porous particles produced continuous release of the drug for 24 hours in vitro. When administered intratracheally, PLGA based formulations produced 100–150 fold extension in the half-life (582.4±70.3 min for nonporous and 362.3±50.6 min for porous particles respectively) of the drug compared to plain PGE1 administered via the intravenous (t1/2=1.5±0.2 min) or intratracheal route (t1/2=3.5±0.4 min). The bioavailability of the encapsulated drug was higher than the plain drug, which was 1.02±0.15 and 0.96±0.13 for nonporous and porous particles, respectively. Further, the formulations were stable in lung homogenates and safe for pulmonary administration14,16. Importantly, compared to nonporous particles, porous particles have been shown to deposit extensively in the deep lungs33 and thus these particles are considered to be appropriate carriers for delivery of drug for PH, a disease of the distant pulmonary arterioles. In contrast, nonporous particles, because of their small geometric diameter are quickly taken up by alveolar macrophages and cleared by lungs clearance mechanisms and thus these particles are not suitable controlled released carriers for inhalational delivery.

As a continuation to our earlier studies, this study investigates the influence of plain drug, PGE1, and PGE1 encapsulated in PLGA particles on improving the pulmonary hemodynamics and reversing biochemical changes that are associated with PH in an MCT-induced rat model of the disease. MCT model is a widely used disease model of PH although it lacks many hallmarks of human PH including plexiform and neointimal lesions34. Upon injection of MCT, rats develop PH characterized by increased muscularization and reduced luminal diameter of small pulmonary arteries, pulmonary hypertension and compensatory right heart hypertrophy over a period of 3–4 weeks35. In fact, many of these characteristics mimics important features of both primary and secondary forms of PH in humans which include endothelial hypertrophy, smooth muscle dysfunction and vascular remodeling36. Data presented above suggest that PH was developed 4 weeks after subcutaneous injection of MCT, as demonstrated by an increase in MPAP (Figs. 1 and 2), right ventricular hypertrophy (Fig.2), increase in muscularized blood vessels (Fig.3), adventitial collagen deposition (Fig. 4), endothelial damage (Fig. 5), and levels of MMPs and PCNA (Fig. 6).

The influence of the formulation on pulmonary hemodynamics was studied after acute and chronic administration into PH rats. Acute hemodynamic studies revealed that PGE1 is a preferential pulmonary vasodilator, which is because of the fact that lungs are the primary sites of metabolism of this drug: 70–90% PGE1 is cleared from the circulation during a single pass21. Thus, upon intratracheal administration a small amount of PGE1 reaches the systemic circulation and elicits minimal systemic effect37. Similar to the pharmacokinetic profiles of the polymeric particles of PGE1 reported in our earlier studies14,15, polymeric particles based formulations produce a slow and continuous influx of the drug into the diseased pulmonary arterioles that resulted in sustained pulmonary vasodilation (Fig.1). Like MPAP data, formulations showed a comparable reduction in MSAP and the extent of reduction was smaller than that produced by intravenous plain PGE1. Overall, the acute hemodynamic studies suggest that intratracheal administration of polymeric formulations keep the MPAP down for a longer period of time.

For chronic studies large porous particles were administered for 10 days and the data revealed that polymeric formulations of PGE1 provided long-term protection against PH symptoms at a reduced dosing frequency. While saline treatment for 10 days resulted in deterioration of the disease condition, porous particles administered once-a-day was as effective as intravenous and intratracheal plain PGE1 administered t.i.d. Interestingly, once-a-day dose of porous particles was more efficacious than thrice-a-day dose of porous particles (Fig. 2). The improved efficacy of once-a-day dosing may stem from the fact that polymeric formulations when given at a shorter dosing frequency form aggregates during nebulization in the lungs which may hamper their drug release and hence reduce local drug concentration. This phenomenon has been observed by some other groups, which is considered to be a reason for reduced or lack of efficacy38. Clumping/aggregation of particles may occur due to loss of water soluble polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) layer in the physiological environment of lungs. PVA acts as an emulsion stabilizer, protecting particles from coalescing to each other and thus affect size, shape, stability and release behavior of particles39. Alternatively, induction of phagocytic activity upon repeated dosing could also contribute to the reduced efficacy observed with thrice-a-day dosing as reported by others40. Based on these facts, we assume that although a reduced amount of drug was available, once-a-day dose was more efficacious than thrice-a-day dose particles. However, some may question the assumption of particle aggregation since no such phenomenon was observed when in vitro release studies were performed in simulated lung fluids. Concerns could also be raised regarding the safety and biological activity of PLGA upon long term administration to the lung. However, published studies suggest that chronic administration of PLGA particles elicits no significant toxicity and neither does it have any pharmacological properties41. We have also shown that PLGA particles undergo degradation at the end of 8 hrs14,16, suggesting that PLGA would be safe to use in inhaled formulations. However, similar to other inhaled formulations, dose inaccuracy, oropharyngeal deposition and inflammatory response due to repeated administration would remain to be the limitations of proposed polymer based formulations.

Upon studying the influence of the formulations on pulmonary hemodynamics, we evaluated the hearts and lungs of the PH rats to assess the effect of the formulations on various anatomical and biochemical markers of the disease including right ventricular hypertrophy, medial wall thickness, degree of muscularization and enzymatic activity. Of those markers, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) is the results of compensatory adaptations that the heart develops during the early stages of PH due to increased workload on right ventricle of the heart. RV/LV+S ratio has been used to evaluate RVH in diseased lungs35. In agreement with published reports42, plain PGE1 caused reversal of RVH in MCT rats (Fig.2C). Likewise, porous particles were effective in reducing RVH at a reduced dosing frequency. In reversing RVH, once-a-day dosing of particles containing PGE1 was nearly as efficacious as intravenous and intratracheal PGE1 administered thrice-a-day.

Similar to formulations’ efficacy in reversing RVH, histopathological evaluation of PH lung sections revealed that PGE1 achieved regression of PH. In humans, PH development is primarily characterized by structural changes in the pulmonary vasculature including progressive intimal hyperplasia and de novo muscularization of otherwise non-muscularized distal pulmonary arterioles. Intimal hyperplasia has also been observed to some extent in MCT-induced PH. The increased muscularization can be visualized by staining of α-SMA in lung sections. Several reports have established the efficacy of FDA approved prostacyclin analogs in attenuating PH symptoms by decreasing the number of muscularized intraacinar small pulmonary arterioles 8,43. Data in this study suggest that intratracheal plain PGE1, unlike its intravenous counterpart, did not result in a significant reduction in fully muscularized blood vessels (Fig. 3). However, large porous polymeric particles of PGE1 was as effective as intravenous PGE1 in reducing fully muscularized blood vessels, suggesting that polymer based formulations could be administered at a reduced dosing frequency.

A significant increase in medial wall thickness (MWT) in MCT induced rats was observed 4 weeks after MCT treatment, but this started to disappear by 38 days with saline treatment (Fig. 3B). Our data suggest that MCT may not be an appropriate model for assessing vascular remodeling in pulmonary arterioles as small as <50 µm and arteries with 100–150 µm diameter would have provided more convincing data, a limitation of this study. Several studies have suggested that this phenomenon could also be related to changes due to fixation in the lumen area 30,44,45. In addition to MWT, in PH, remodeling of pulmonary arteries stimulates deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins including collagen fibers, fibronectin and elastin46. PGE1 has been documented to reduce collagen deposition by TGF-β inhibition47,48. Trichrome staining photographs (Fig. 4) suggest that plain PGE1 and polymeric particles of PGE1 significantly suppressed collagen deposition in pulmonary vessels <100 µm diameter. However, in terms of inhibiting collagen expression in pulmonary vascular walls, the efficacy of once-a-day particles was comparable to that of thrice-a-day particles, intravenous or inhalable plain PGE1, suggesting that the controlled release PLGA microparticles can provide long-term benefits at a reduced dosing frequency. Nevertheless, these qualitative data provide very limited information; quantitation of collagen deposition upon treatment with the formulation could have given further credence to trichrome staining based data presented in this study.

MCT treatment induces endothelial cell injury35 and over-expression of endothelin promotes platelet aggregation49. Inhibition of platelet aggregation is one of the most important effects of PGE117 that may complement its anti-PH effects. vWF is a large multimeric glycoprotein found in blood plasma that has been documented as a marker for PH prognosis and endothelial cell dysfunctions50–52. vWF accumulation (Fig.5) in pulmonary vascular endothelium was significantly reduced with once-a-day dose of polymeric particles, which was comparable to that of plain PGE1 administered via the intravenous and pulmonary routes. Efficacy of PGE1 in reducing platelet aggregation via reduced vWF accumulation in PH lungs is a novel finding of this study. However, this data should be interpreted with caution because reduction in vWF may also result from some phenotypic changes in endothelial cells. Further, quantitative analysis of vWF staining in conjunction with visual inspection would have provided more meaningful data regarding the influence of formulation on vWF expression.

Hemodynamic data are in agreement with the data on the levels of MMPs observed in the lung homogenates of different treatment groups. MMP-2 and -9, zinc-dependent endopeptidases, degrade type IV collagen in extracellular matrix and their upregulation plays an important role in vascular remodeling during PH development via induction of tenascin-C53. Their levels increased up to 4–5 folds during PH progression. It is reported that prostacyclin analogs hinder the activity of membrane type I MMP, which is responsible for activation of MMP-2 via cAMP pathway54. MMP-2 has been used as a surrogate marker to determine vascular remodeling during PH development and is a major player in pathogenesis of inflammation, autoimmune diseases, and cancer including a variety of cardiovascular disorders and viral infections55. In the current study, both plain and controlled release PGE1 formulations showed a significant and comparable reduction in MMP-2 levels during chronic treatment, which indicates the efficacy of polymeric particles in hindering PH development. However, no significant increase in MMP-9 activity was observed during MCT treatment, which is in congruence with several published reports suggesting that MMP-9 upregulation may not have a significant role in PH pathogenesis30,56,57. Although the data presented here underline the efficacy of PGE1 in reducing MMP-2 expression in MCT induced PH rats, MMP-2 cannot be regarded as a good standard for PH pathogenesis unless supported by hemodynamic and morphometric measurements.

To understand the mechanisms by which the PGE1 alleviates PH symptoms, we tested the effect of both plain PGE1 and particles of PGE1 on cell proliferation in lung homogenates by determining the expression of PCNA. MCT treatment in rats is known to induce smooth muscle cell proliferation thus results in vascular remodeling and right ventricular hypertrophy, symptoms similar to human PH58. PGE1 has been reported to inhibit the expression of PCNA-positive smooth muscle cells in a rat model of glomerulonephritis59. However, no study has thus far delineated the efficacy of PGE1 in suppressing cell proliferation in the pulmonary vasculature. Our study suggest that once-a-day chronic administration of controlled release PGE1 particles decreased PCNA expression as much as 15–20%, which is comparable to thrice-a-day plain PGE1 administration via the pulmonary route. These data are consistent with the data regarding the influence of plain drug and formulation on other cellular markers discussed above.

CONCLUSIONS

On the whole, inhalable PLGA particles of PGE1 produce a sustained pulmonary vasodilation, which can be attributed to continuous release of the drug from polymeric particles. Polymeric particles showed comparable or improved efficacy in ameliorating PH symptoms such as MPAP, right ventricular hypertrophy, muscularization of pulmonary blood vessels and arterial cell proliferation at a reduced dosing frequency. The data presented in this manuscript suggest that inhaled PGE1 loaded PLGA particles are likely to circumvent limitations associated current anti-PH. Further, this study also laid the ground work for developing polymeric controlled release formulations of anti-PH drugs including various injectable prostacyclin analogues.

ACKNOWLEGMENTS

This work was supported in part by an American Recovery and Reinvestment Act Fund, NIH 1R15HL103431 to Dr. Fakhrul Ahsan. Histological evaluations of lung samples were done at IHCtech, Aurora, CO in collaboration with Drs. Eva Nozik-Grayck and Kurt Stenmark.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta V, Ahsan F. Inhalational therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: current status and future prospects. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2010;27(4):313–370. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v27.i4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rich S, Dantzker DR, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, Fishman AP, Goldring RM, Groves BM, Koerner SK, et al. Primary pulmonary hypertension. A national prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(2):216–223. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-2-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin KB, Klinger JR, Rounds SI. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: new insights and new hope. Respirology. 2006;11(1):6–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weissmann N, Akkayagil E, Quanz K, Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Fink L, Hanze J, Rose F, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Basic features of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in mice. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2004;139(2):191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corris PA. Alternatives to lung transplantation: treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32(2):399–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyal P, Weissmann N, Grimminger F, Hegel C, Bader L, Rose F, Fink L, Ghofrani HA, Schermuly RT, Schmidt HH, Seeger W, Hanze J. Upregulation of NAD(P)H oxidase 1 in hypoxia activates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 via increase in reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36(10):1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghofrani HA, Friese G, Discher T, Olschewski H, Schermuly RT, Weissmann N, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Lohmeyer J. Inhaled iloprost is a potent acute pulmonary vasodilator in HIV-related severe pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(2):321–326. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00057703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schermuly RT, Kreisselmeier KP, Ghofrani HA, Samidurai A, Pullamsetti S, Weissmann N, Schudt C, Ermert L, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Antiremodeling effects of iloprost and the dual-selective phosphodiesterase 3/4 inhibitor tolafentrine in chronic experimental pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2004;94(8):1101–1108. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126050.41296.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gomberg-Maitland M, Preston IR. Prostacyclin therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: new directions. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;26(4):394–401. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galie N, Manes A, Negro L, Palazzini M, Bacchi-Reggiani ML, Branzi A. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(4):394–403. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, Bertocchi M, Habib G, Gressin V, Yaici A, Weitzenblum E, Cordier JF, Chabot F, Dromer C, Pison C, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Haloun A, Laurent M, Hachulla E, Simonneau G. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: results from a national registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(9):1023–1030. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1668OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyduk A, Croft JB, Ayala C, Zheng K, Zheng ZJ, Mensah GA. Pulmonary hypertension surveillance--United States, 1980–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2005;54(5):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghofrani HA, Voswinckel R, Reichenberger F, Olschewski H, Haredza P, Karadas B, Schermuly RT, Weissmann N, Seeger W, Grimminger F. Differences in hemodynamic and oxygenation responses to three different phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a randomized prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(7):1488–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta V, Ahsan F. Influence of PEI as a core modifying agent on PLGA microspheres of PGE, a pulmonary selective vasodilator. Int J Pharm. 2011;413(1–2):51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta V, Davis M, Hope-Weeks LJ, Ahsan F. PLGA microparticles encapsulating prostaglandin E1-hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (PGE1-HPbetaCD) complex for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) Pharm Res. 2011;28(7):1733–1749. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta V, Rawat A, Ahsan F. Feasibility study of aerosolized prostaglandin E1 microspheres as a noninvasive therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99(4):1774–1789. doi: 10.1002/jps.21946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kloeze J. Relationship between chemical structure and platelet-aggregation activity of prostaglandins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1969;187(3):285–292. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(69)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin G, Duffin KL, Obukowicz MG, Hummert SL, Fujiwara H, Needleman P, Raz A. Differential metabolism of dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid and arachidonic acid by cyclo-oxygenase-1 and cyclo-oxygenase-2: implications for cellular synthesis of prostaglandin E1 and prostaglandin E2. Biochem J. 2002;365(Pt 2):489–496. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salvatori R, Guidon PT, Jr, Rapuano BE, Bockman RS. Prostaglandin E1 inhibits collagenase gene expression in rabbit synoviocytes and human fibroblasts. Endocrinology. 1992;131(1):21–28. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.1.1377121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zurier RB, Quagliata F. Effect of prostaglandin E 1 on adjuvant arthritis. Nature. 1971;234(5327):304–305. doi: 10.1038/234304a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer J, Theilmeier G, Van Aken H, Bone HG, Busse H, Waurick R, Hinder F, Booke M. Inhaled prostaglandin E1 for treatment of acute lung injury in severe multiple organ failure. Anesth Analg. 1998;86(4):753–758. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunimoto F, Arai K, Isa Y, Koyano T, Kadoi Y, Saito S, Goto F. A comparative study of the vasodilator effects of prostaglandin E1 in patients with pulmonary hypertension after mitral valve replacement and with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(3):507–513. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199709000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen J, He B, Wang B. Effects of lipo-prostaglandin E1 on pulmonary hemodynamics and clinical outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2005;128(2):714–719. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sood BG, Delaney-Black V, Aranda JV, Shankaran S. Aerosolized PGE1: a selective pulmonary vasodilator in neonatal hypoxemic respiratory failure results of a Phase I/II open label clinical trial. Pediatr Res. 2004;56(4):579–585. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000139927.86617.B6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox JW, Andreadis NA, Bone RC, Maunder RJ, Pullen RH, Ursprung JJ, Vassar MJ. Pulmonary extraction and pharmacokinetics of prostaglandin E1 during continuous intravenous infusion in patients with adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;137(1):5–12. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/137.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Heerden PV, Caterina P, Filion P, Spagnolo DV, Gibbs NM. Pulmonary toxicity of inhaled aerosolized prostacyclin therapy--an observational study. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28(2):161–166. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0002800206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwards DA, Hanes J, Caponetti G, Hrkach J, Ben-Jebria A, Eskew ML, Mintzes J, Deaver D, Lotan N, Langer R. Large porous particles for pulmonary drug delivery. Science. 1997;276(5320):1868–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowan KN, Heilbut A, Humpl T, Lam C, Ito S, Rabinovitch M. Complete reversal of fatal pulmonary hypertension in rats by a serine elastase inhibitor. Nat Med. 2000;6(6):698–702. doi: 10.1038/76282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stinger RB, Iacopino VJ, Alter I, Fitzpatrick TM, Rose JC, Kot PA. Catheterization of the pulmonary artery in the closed-chest rat. J Appl Physiol. 1981;51(4):1047–1050. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.51.4.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crossno JT, Jr, Garat CV, Reusch JE, Morris KG, Dempsey EC, McMurtry IF, Stenmark KR, Klemm DJ. Rosiglitazone attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292(4):L885–L897. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00258.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Rheen Z, Fattman C, Domarski S, Majka S, Klemm D, Stenmark KR, Nozik-Grayck E. Lung extracellular superoxide dismutase overexpression lessens bleomycin-induced pulmonary hypertension and vascular remodeling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44(4):500–508. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0065OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guignabert C, Raffestin B, Benferhat R, Raoul W, Zadigue P, Rideau D, Hamon M, Adnot S, Eddahibi S. Serotonin transporter inhibition prevents and reverses monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Circulation. 2005;111(21):2812–2819. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel B, Gupta V, Ahsan F. PEG-PLGA based large porous particles for pulmonary delivery of a highly soluble drug, low molecular weight heparin. J Control Release. 2012;162(2):310–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez-Arroyo JG, Farkas L, Alhussaini AA, Farkas D, Kraskauskas D, Voelkel NF, Bogaard HJ. The monocrotaline model of pulmonary hypertension in perspective. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302(4):L363–L369. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00212.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Todd L, Mullen M, Olley PM, Rabinovitch M. Pulmonary toxicity of monocrotaline differs at critical periods of lung development. Pediatr Res. 1985;19(7):731–737. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198507000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hilliker KS, Bell TG, Roth RA. Pneumotoxicity and thrombocytopenia after single injection of monocrotaline. Am J Physiol. 1982;242(4):H573–H579. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.242.4.H573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price LC, Wort SJ, Finney SJ, Marino PS, Brett SJ. Pulmonary vascular and right ventricular dysfunction in adult critical care: current and emerging options for management: a systematic literature review. Critical care. 2010;14(5):R169. doi: 10.1186/cc9264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcia-Contreras L, Sethuraman V, Kazantseva M, Godfrey V, Hickey AJ. Evaluation of dosing regimen of respirable rifampicin biodegradable microspheres in the treatment of tuberculosis in the guinea pig. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58(5):980–986. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeong YI, Song JG, Kang SS, Ryu HH, Lee YH, Choi C, Shin BA, Kim KK, Ahn KY, Jung S. Preparation of poly(DL-lactide-co-glycolide) microspheres encapsulating all-trans retinoic acid. Int J Pharm. 2003;259(1–2):79–91. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(03)00207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lombry C, Edwards DA, Preat V, Vanbever R. Alveolar macrophages are a primary barrier to pulmonary absorption of macromolecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286(5):L1002–L1008. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00260.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harush-Frenkel O, Bivas-Benita M, Nassar T, Springer C, Sherman Y, Avital A, Altschuler Y, Borlak J, Benita S. A safety and tolerability study of differently-charged nanoparticles for local pulmonary drug delivery. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;246(1–2):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kato S, Sugimura H, Kishiro I, Machida M, Suzuki H, Kaneko N. Suppressive effect of pulmonary hypertension and leukocyte activation by inhaled prostaglandin E1 in rats with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Exp Lung Res. 2002;28(4):265–273. doi: 10.1080/01902140252964357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schermuly RT, Yilmaz H, Ghofrani HA, Woyda K, Pullamsetti S, Schulz A, Gessler T, Dumitrascu R, Weissmann N, Grimminger F, Seeger W. Inhaled iloprost reverses vascular remodeling in chronic experimental pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(3):358–363. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-296OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Howell K, Preston RJ, McLoughlin P. Chronic hypoxia causes angiogenesis in addition to remodelling in the adult rat pulmonary circulation. J Physiol. 2003;547(Pt 1):133–145. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hyvelin JM, Howell K, Nichol A, Costello CM, Preston RJ, McLoughlin P. Inhibition of Rho-kinase attenuates hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in the pulmonary circulation. Circ Res. 2005;97(2):185–191. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000174287.17953.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stenmark KR, Mecham RP. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pulmonary vascular remodeling. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:89–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dell K, Bohler T, Gaedeke J, Budde K, Neumayer HH, Waiser J. Impact of PGE1 on cyclosporine A induced up-regulation of TGF-beta1, its receptors, and related matrix production in cultured mesangial cells. Cytokine. 2003;22(6):189–193. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(03)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schneider A, Thaiss F, Rau HP, Wolf G, Zahner G, Jocks T, Helmchen U, Stahl RA. Prostaglandin E1 inhibits collagen expression in anti-thymocyte antibody-induced glomerulonephritis: possible role of TGF beta. Kidney Int. 1996;50(1):190–199. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luscher TF, Barton M. Endothelins and endothelin receptor antagonists: therapeutic considerations for a novel class of cardiovascular drugs. Circulation. 2000;102(19):2434–2440. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.19.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lopes AA, Maeda NY, Aiello VD, Ebaid M, Bydlowski SP. Abnormal multimeric and oligomeric composition is associated with enhanced endothelial expression of von Willebrand factor in pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 1993;104(5):1455–1460. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.5.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sadler JE. Biochemistry and genetics of von Willebrand factor. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:395–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Veyradier A, Nishikubo T, Humbert M, Wolf M, Sitbon O, Simonneau G, Girma JP, Meyer D. Improvement of von Willebrand factor proteolysis after prostacyclin infusion in severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2000;102(20):2460–2462. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.20.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lepetit H, Eddahibi S, Fadel E, Frisdal E, Munaut C, Noel A, Humbert M, Adnot S, D'Ortho MP, Lafuma C. Smooth muscle cell matrix metalloproteinases in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2005;25(5):834–842. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00072504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shankavaram UT, Lai WC, Netzel-Arnett S, Mangan PR, Ardans JA, Caterina N, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Birkedal-Hansen H, Wahl LM. Monocyte membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase. Prostaglandin-dependent regulation and role in metalloproteinase-2 activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(22):19027–19032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009562200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gutierrez FR, Lalu MM, Mariano FS, Milanezi CM, Cena J, Gerlach RF, Santos JE, Torres-Duenas D, Cunha FQ, Schulz R, Silva JS. Increased activities of cardiac matrix metalloproteinases matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 are associated with mortality during the acute phase of experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(10):1468–1476. doi: 10.1086/587487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giannelli G, Iannone F, Marinosci F, Lapadula G, Antonaci S. The effect of bosentan on matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels in patients with systemic sclerosis-induced pulmonary hypertension. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21(3):327–332. doi: 10.1185/030079905X30680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palei AC, Zaneti RA, Fortuna GM, Gerlach RF, Tanus-Santos JE. Hemodynamic benefits of matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibition by doxycycline during experimental acute pulmonary embolism. Angiology. 2005;56(5):611–617. doi: 10.1177/000331970505600513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lai YL, Law TC. Chronic hypoxia- and monocrotaline-induced elevation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha levels and pulmonary hypertension. J Biomed Sci. 2004;11(3):315–321. doi: 10.1007/BF02254435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kunihara M, Tsuchida K, Kaneko K, Suga H, Hasegawa T, Mochizuki S, Kawai K, Shiga A, Yamaguchi T. Inhibitory effects of alprostadil (prostaglandin E1) incorporated in lipid microspheres of soybean oil on intimal hyperplasia following balloon injury in rabbits. Arzneimittelforschung. 2002;52(5):358–364. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]