Abstract

To explore the possibility of using a mini-array of multiple tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) as an approach to the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), 14 TAAs were selected to examine autoantibodies in sera from patients with chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and HCC by immunoassays. Antibody frequency to any individual TAA in HCC varied from 6.6% to 21.1%. With the successive addition of TAAs to the panel of TAAs, there was a stepwise increase of positive antibody reactions. The sensitivity and specificity of 14 TAAs for immunodiagnosis of HCC was 69.7% and 83.0%, respectively. This TAAs mini-array also identified 43.8% of HCC patients who had normal alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in serum. In summary, this study further supports the hypothesis that a customized TAA array used for detecting anti-TAA autoantibodies can constitute a promising and powerful tool for immunodiagnosis of HCC and may be especially useful in patients with normal AFP levels.

Keywords: Autoantibodies, Tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), Cancer immunodiagnosis, Hepatocellular carcinoma

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. The majority of people with HCC will die within one year of diagnosis. The high fatality rate of HCC can partly be attributed to a lack of sensitive detection methods for early diagnosis. Up to now, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is the most widely used serological marker used in HCC diagnosis. However, it is well-documented that its specificity is not high enough, especially in the context of chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis, and its sensitivity is related very much to the size of the tumor [1]. Therefore, the efficacy of AFP in the screening for HCC is not optimal and additional biomarkers are urgently needed.

There are many studies demonstrating that the immune system can recognize antigenic changes in cancer cells, leading to development of autoantibodies against these antigens which have been called tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) [2–4]. Therefore, these autoantibodies have been called “reporters” from the immune system which identify antigenic changes in cellular proteins involved in the malignant transformation process [4,5]. Autoantibodies from patients with HCC have been used to screen cDNA expression libraries and several novel TAAs such as CAPERα/HCC1.4 [6], IMP2/p62 [7] and CIP2A/p90 [8] have been isolated and characterized. The observations that patients’ immune system have the capability of recognizing TAAs raises the possibility that characterization of humoral immune responses could provide both diagnostic and prognostic information. Determining the molecular identity of targets of such autoantibodies (autoantibody signatures) would be relevant for serological screening tests for malignancies, an approach which has been called “cancer immunomics” [9–12]. In our previous study, we screened sera from 142 patients with HCC for autoantibodies using a target panel of eight selected TAAs comprising IMP1, IMP2/p62, IMP3/Koc, p53, c-Myc, cyclin B1, survivin and p16/INK4a, and demonstrated that no individual TAA was sensitive or specific enough for HCC detection. Autoantibody to any individual TAA in this panel ranged from 9.9% to 21.8%, but reached 59.8% to the panel of eight TAAs. This study demonstrated the importance of developing multiple or a mini-array of TAAs as an approach in immunodetection of cancer [13]. It also addressed an important issue that highlights a promising way for the development of biomarkers in cancer, dealing with the concept of “cancer immunomics” and promoting a global analysis of the autoantibodies in cancer. Importantly, implementation of such an approach requires the careful selection of target TAAs since it appears likely that there might be selective TAA panels for different cancers. In the present study, we explored this hypothesis using a panel of 14 TAAs for detection of autoantibodies in HCC to determine the possibility and usefulness of such a panel of TAAs in HCC immunodiagnosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Serum samples

Sera from 76 patients with HCC, 30 patients with chronic hepatitis (CH), 30 patients with liver cirrhosis (LC) were obtained from the serum bank of the Cancer Autoimmunity Research Laboratory at University of Texas (El Paso, Texas, USA). Eighty-nine normal human sera (NHS) were originally obtained from the serum bank in the Autoimmune Disease Center at the Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, CA, USA). Of 76 HCC patients, 71 (93.4%) were histologically confirmed, 50 (65.8%) were male, and 26 (34.2%) were female. Mean age was 57.0±11.2 years (range, 23–77 years). Fifty-two (68.4%) patients were positive for HBV, 6 (7.9%) patients for HCV, and 4 (5.3%) for both HBV and HCV. Forty-eight (63.2%) had previous history for chronic hepatitis, 13 (17.1%) patients had liver cirrhosis, and 9 (11.8%) patients had no previous history of either chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis. Based on the Chinese general diagnostic guidelines for liver cancer, 23 (30.3%) patients were in clinical stage I, 14 (18.4%) in stage II, 24(31.6%) in stage III, 8(10.3%) in stage IV, respectively, and 5 (6.7%) patients had no available data as to clinical stages.

In the present study, 43 sera were available for AFP testing. The AFP test kit was provided by GenWay Biotech (San Diego, CA). The results showed that 62.8% (27/43) sera had abnormal AFP levels (>100ng/ml) whereas 16 (37.2%) had normal levels (<100ng/ml). All cancer patients were diagnosed according to established criteria; their serum samples were collected at the time of initial cancer diagnosis, when the patients had not received treatment with any chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Seventy-nine serial serum samples from 16 HCC patients were from Shinshu University School of Medicine Affiliated Hospitals in Matsumoto, Japan. The serum samples included at least two to four samples obtained several months prior to clinical detection of liver malignancy. All of the patients had previous history for chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis.

Normal human sera were collected from adults during annual health examinations in people who had no obvious evidence of malignancy. Due to regulations concerning studies of human subjects, the patient’s name and identification number were blinded to investigators, and some clinical information for sera used in this study were not currently available. In addition, as representative of patients with known immune reactivity to other autologous cellular antigens, sera from 51 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and 94 patients with progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS) were available from serum bank of the Autoimmune Disease Center (Scripps) and were evaluated with the same immunoassays for their response to the 14 TAA panel. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas at El Paso and Collaborating Institutions, and informed consents from all human subjects were obtained for experimentation.

2.2. Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

Fourteen antigens, IMP1, p62, Koc, p53, survivin, p16, CAPERα, p90, RalA, NPM1, MDM2, 14-3-3 ζ, c-Myc and cyclin B1, were selected for expression of recombinant proteins. Recombinant p62 has been expressed from a clone isolated from cDNA expression library by immunoscreening with antibody from a patient with HCC [7]. p62 cDNA was subcloned into vector producing a fusion protein with NH-terminal 6× histidine and T7 epitope tags. The recombinant protein expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) was purified using nickel column chromatography. Koc cDNA cloned into the pcDNA3 vector was similarly subcloned to pET28a vector and recombinant protein expressed as above. IMP1 construct pCMV5-IMP1 was kindly provided by F.C. Nielsen and p53 clone (p53SN3) by Yuxin Yin of Columbia University, New York, NY, and subcloned into pET28a for protein expression. cDNA from c-Myc was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from human fetal liver tissue and survivin cDNA was amplified from human survivin EST clone (BG258433) before subcloning in pET28a vector. Plasmid pET-CAPERα carrying CAPERα cDNA was derived from our previous study [6]. cDNA encoding RalA amplified by PCR from a human expressed sequence tag (EST) clone (#BM560822) was subcloned into pET28a vector. NPM1 construct GFP-NPM WT (plasmid ID: 17578), MDM2 construct pGEX-4T MDM2 WT (plasmid ID: 16237), and 14-3-3 ζ construct GST-14-3-3 WT (plasmid ID: 1944) purchased from Addgene were subcloned into pET28a vector. p16 cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR from human HeLa cells, and was subcloned into the pGEX vector expressing p16 with glutathione S transferase (GST) fusion partner. The GST gene fusion system was used for the expression and purification of p16 recombinant protein. P90 has been cloned from a cDNA expression library by immunoscreening with antibody from a patient with gastric cancer and then subcloned into pGEX [8]. Recombinant cyclin B1 had been prepared and used previously [14] and was isolated from pGEX construct expressing cyclin B1 with GST fusion partner.

Expression of adequate amounts of recombinant protein was examined in SDS–PAGE and Coomassie blue staining was used to determine that expression products of expected molecular sizes were produced. In addition, Western blot analysis was used to confirm that the bands seen in SDS–PAGE were reactive with reference antibodies.

2.3. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Purified recombinant proteins were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a final concentration of 0.5 ug/mL for coating 96 well Immunolon2 microtiter plates (Fisher Scientific, Huston, TX, USA) overnight at 4°C. The human serum samples diluted 1:200 were incubated in the antigen-coated wells for 90 min. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA,USA) was used as a secondary antibody diluted 1:4,000 for coating (90 min) followed by washing with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST). The substrate 2,2’-azino-bis (3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as the detecting agent. The optical density (OD) value of each well was read at 405nm, and the cut-off value for determining a positive reaction was designated as the mean absorbance of the 89 normal sera plus 3 standard deviations (mean+3SD). Each sample was tested in duplicate. Each run of ELISA included 8 NHS representing a range of absorbance above and below the mean of 89 normal human sera, and the average OD value of 8 NHS was used to normalize all absorbance values to the standard mean of the entire 89 normal samples. In addition, lupus and PSS sera were included as representative examples of patients with robust autoantibody responses, but the identified cellular antigens so far known have been reported to be associated with autoimmune rheumatic [15] and it was of interest to know whether these autoimmune patient sera were reactive with any of the cellular antigens in the 14-TAA mini-array.

2.4. Western blotting

Serum samples that were found to contain autoantibodies by ELISA were further tested by immunoblotting to confirm the immunoreactivity of the sera. The purified recombinant proteins of 14 TAAs were electrophoresed by SDS-PAGE and subsequently transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were cut into strips and the individual strips were pre-blocked in PBST with 3% non-fat milk for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated with patient sera diluted 1:200, and finally incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG diluted 1:10000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for 1 h followed by washing with PBST solution. Positive signals were captured by autoradiography using chemiluminescence (Piece Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacture’s instructions.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Chi-square (χ2) test was used to determine whether the frequency of autoantibodies to 14 TAAs in each cohort of patient sera was significantly higher than that in sera from normal individuals. Two significant levels (0.05 and 0.01) were used. Methods for calculating the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio were based on the methodology provided in Epidemiology (6th edition, edited by Dr. Ray M. Merrill, Jones & Bartlett Learning Company, Burlington,2012).

3. Results

3.1. Frequency and titers of autoantibodies in HCC against a mini-array of 14 TAAs

As shown in Table 1, a panel of 14 TAAs was carefully selected and included in the present study, including ten oncoproteins such as three IMP proteins (IMP1, IMP2/p62, IMP3/Koc) [16–20], CIP2A/p90 [7,21,22], RalA [23–25], c-Myc [26,27], survivin [28–30], cyclin B1 [31,32], 14-3-3 ζ [33–36], MDM2 [37–39], and four tumor suppressors such as p53 [40–42], CAPERα/HCC1.4 [6,43,44], p16 [45–47], NPM1 [48–50]. Of these 14 TAAs, 10 TAAs were used in the previous studies [13,32,51–53] except CAPERα/HCC1.4, MDM2, NPM1 and 14-3-3 ζ. Table 2 shows the frequency of autoantibodies to the panel of 14 TAAs. The sera examined in this study include sera from 76 patients with HCC, 30 patients with CH, 30 patients with LC and 89 normal human sera as well as controls representing non-cancer autoimmune diseases including 51 patients with SLE, and 94 with PSS. A positive result for antibody in ELISA was taken as an absorbance reading above the mean + 3SD of the 89 normal human sera. Higher frequency of antibodies against individual TAA in HCC was found with TAAs such as survivin, CAPERα, RalA, p62, Koc, MDM2, cyclin B1, p53 and 14-3-3 ζ, compared to normal human sera (p<0.01). In chronic hepatitis, antibody frequency to any individual TAA ranged from 0 to 6.7%, and in liver cirrhosis, it ranged from 0 to 13.3%. The reactivity of anti-TAAs antibodies in normal human sera was very low, ranging from 0 to 3.4% to any individual TAA. Sera from patients with autoimmune disorders also showed very low frequency of 14 anti-TAAs with no more than 5.9% and established that antibody reactivities observed were cancer specific and not attributable to nonspecific immunoreactivity.

Table 1.

The properties of 14 TAAs.

| properties/functions | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|

| Oncoproteins | ||

| IMP1 | insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 1 | [16–18] |

| IMP2/p62 | insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 2 | [16,18,19] |

| IMP3/Koc | insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 3/K homology protein overexpressed in cancer | [7,16,18,20] |

| CIP2A/p90 | cancerous inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) | [7,21,22] |

| RalA | ras-like GTP-binding protein | [23–25] |

| c-Myc | transcription factor oncoprotein | [26,27] |

| survivin | inhibitor of apoptosis | [28–30] |

| cyclin B1 | cell-cycle nuclear protein | [31,32] |

| 14-3-3 ζ | mediate signal transduction by binding to phosphoserine-containing proteins | [33–36] |

| MDM2 | nuclear phosphoprotein that binds and inhibits transactivation by tumor protein p53 | [37–39] |

| suppressor proteins | ||

| p53 | tumor suppressor protein containing transcriptional activation, DNA binding, and oligomerization domains. | [40–42] |

| Ink4a/p16 | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor | [45–47] |

| NPM1/B23 | nucleolar phosphoprotein involved in several processes including regulation of the ARF/p53 pathway | [48–50] |

| CAPERα/HCC1.4 | mRNA binding protein, steroid hormone receptor-mediated transcription and alternative splicing | [6,43,44] |

Table 2.

Frequency of 14 anti-TAAs in the different conditions.

| Conditions | N | survivin | CAPERα | RalA | p62 | Koc | MDM2 | cyclin B1 | p53 | 14-3-3ζ | p90 | IMP1 | c-Myc | NPM1 | p16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS | 89 | 1(1.1) | 0(0.0) | 2(2.2) | 2(2.2) | 2(2.2) | 1(1.1) | 2(2.2) | 1(1.1) | 0(0.0) | 3(3.4) | 3(3.4) | 1(1.1) | 2(2.2) | 2(2.2) |

| HCC | 76 | 16(21.1)Δ | 16(21.1)Δ | 14(18.4)Δ | 13(17.1)Δ | 12(15.8)Δ | 12(15.8)Δ | 11(14.5)Δ | 10(13.2)Δ | 10(13.2)Δ | 9(11.8)* | 9(11.8)* | 9(11.8)* | 8(10.5)* | 5(6.6) |

| CH | 30 | 0(0.0) | 1(3.3) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 2(6.7) | 2(6.7) | 0(0.0) | 1(3.3) | 0(0.0) | 1(3.3) | 3(10.0) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 2(6.7) |

| LC | 30 | 0(0.0) | 2(6.7) | 1(3.3) | 1(3.3) | 4(13.3)* | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 2(6.7) | 0(0.0) | 1(3.3) | 0(0.0) | 1(3.3) | 1(3.3) | 4(13.3)* |

| SLE | 51 | 2(3.9) | 2(3.9) | 2(3.9) | 2(3.9) | 2(3.9) | 2(3.9) | 3(5.9) | 0(0.0) | 1(2.0) | 3(5.9) | 2(3.9) | 2(3.9) | 3(5.9) | 2(3.9) |

| PSS | 94 | 4(4.3) | 0(0.0) | 2(2.1) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | 3(3.2) | 3(3.2) | 3(3.2) | 3(3.2) | 2(2.1) | 1(1.1) | 0(0.0) | 2(2.1) | 2(2.1) |

: p<0.01;

: p<0.05

NHS: normal human sera; CH: chronic hepatitis; LC: liver cirrhosis; SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus; PSS: progressive systemic sclerosis

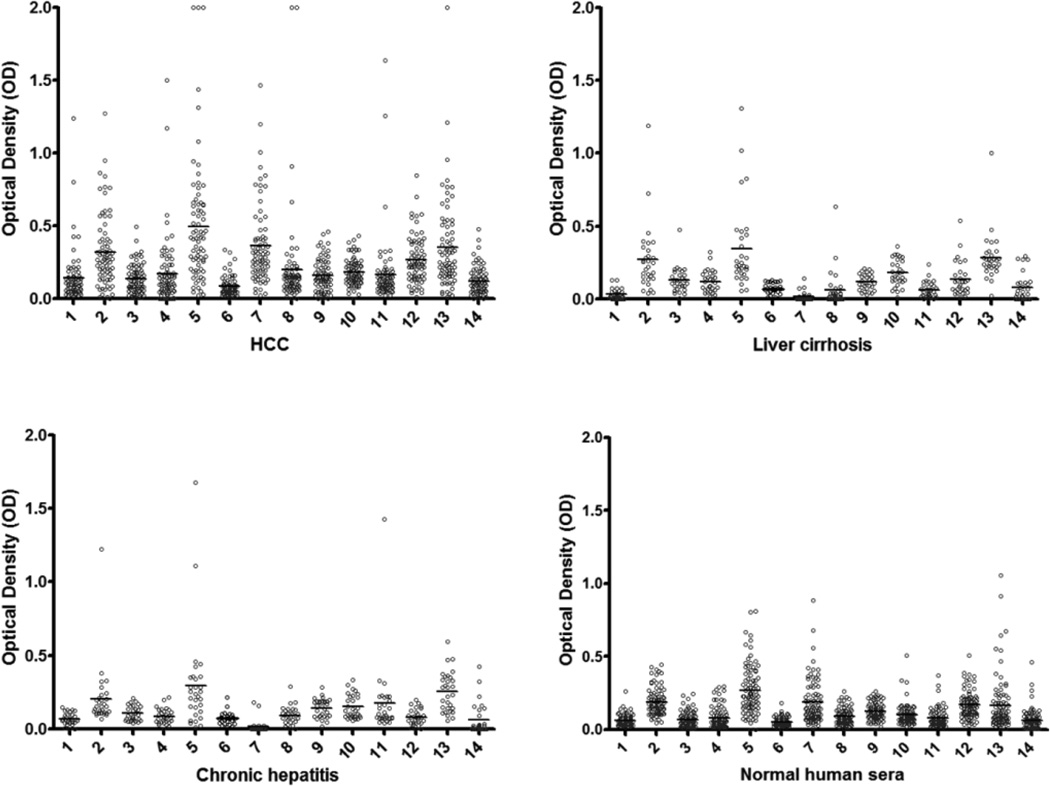

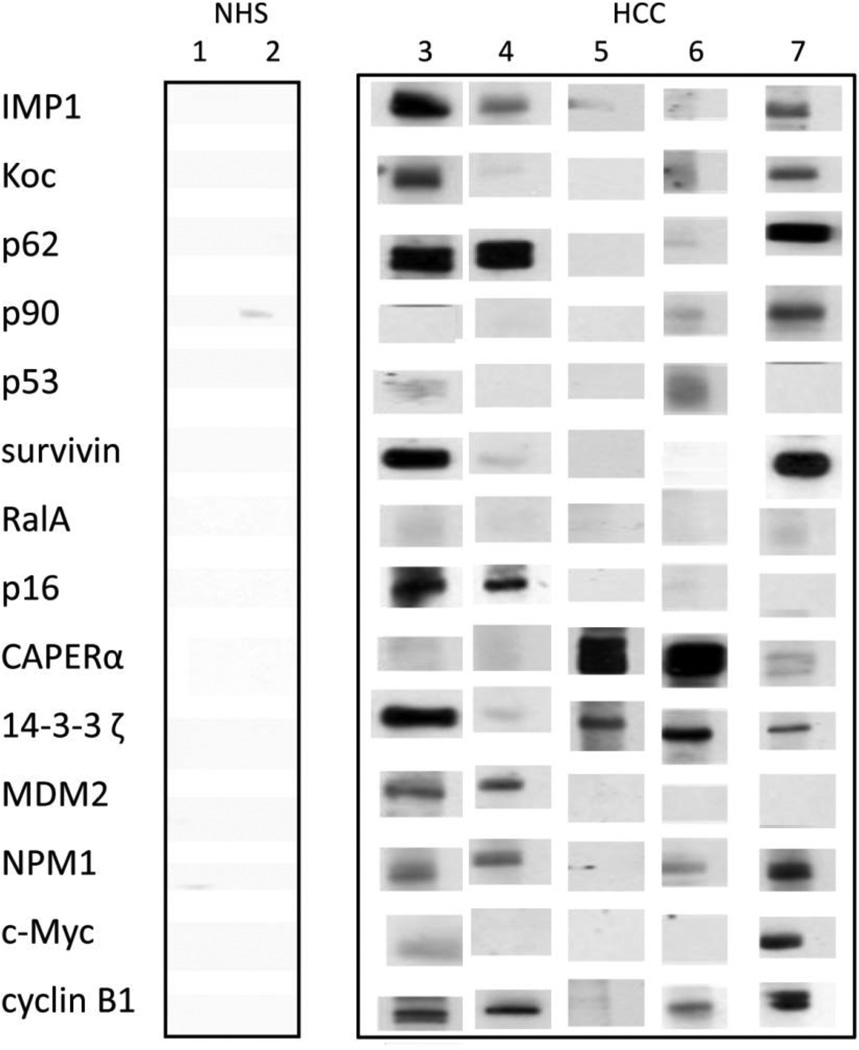

The titers of 14 anti-TAAs antibodies in different conditions are shown in Figure. 1. The high titer in many HCC sera and distinct difference between HCC and other conditions such as chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and normal individuals were also demonstrated in this figure. Many HCC sera showed absorbance readings several-fold above the cutoff (mean of 89 NHS +3SD), indicating that antibody responses in some HCC patients were quite robust and not just mildly elevated. All of the sera with positive results in ELISA were verified by Western blotting with purified recombinant proteins. Figure 2 shows that some representative patients with HCC produced multiple autoantibodies, whereas normal individuals rarely showed multiple autoantibodies to the 14-TAA panel.

Figure 1.

The range of antibody titers to different tumor associated antigens is expressed as absorbance units obtained from enzyme immunoassays. The mean of optical density (OD) was shown for very kind of condition. The high titer reactivity of HCC sera and the distinct difference between cancer and normal and autoimmune sera are demonstrated in this figure.

The X-axis represents the panel of 14 TAAs. 1, survivin; 2, CAPERα; 3, RalA; 4, P62; 5, Koc; 6, MDM2; 7, cyclin B1; 8, p53; 9, 14-3-3 ζ; 10, p90; 11, IMP1; 12, c-Myc; 13, NPM1; 14, p16.

Figure 2.

Some representative sera show immunoreactivity to 14 TAAs, which were verified by Western blotting. Lanes 1, 2: NHS; lanes 3–7: HCC sera. Some HCC sera show reaction with multiple antibodies against 14 TAAs, while in contrast, normal human sera show very weak or no reactions and rarely multiple reactions with 14 TAAs.

3.2. Stepwise increase in rate of anti-TAAs positivity with successive addition of antigens

As shown in Table 3, antibody frequency to any individual TAA in HCC was variable from 5.3% to 21.1%. When we added the antigens to the panel starting with CAPERα-TAA which had the highest occurrence of autoantibody in HCC to successive TAAs with lower occurrence, there was a stepwise increase of positive antibody reactions up to 69.7%, which was significantly higher than the frequency of antibodies in chronic hepatitis (30.0%), liver cirrhosis (36.7%) and normal individuals (17.0%).

Table 3.

Sequential addition of antigens to the panel of 14TAAs.

| Antigens | NHS | HCC | CH | LC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 TAA | CAPERα | 0(0.0) | 16(21.2) | 1(3.3) | 2(6.7) |

| 2 TAA | CAPERα or survivin | 1(1.1) | 28(36.8) | 1(3.3) | 2(6.7) |

| 3 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA | 3(3.4) | 30(39.5) | 1(3.3) | 2(6.7) |

| 4 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 | 5(5.6) | 34(44.7) | 1(3.3) | 3(10.0) |

| 5 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc | 5(5.6) | 40(52.6) | 3(10.0) | 5(16.7) |

| 6 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 | 6(6.7) | 42(55.3) | 5(16.7) | 5(16.7) |

| 7 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 | 9(10.1) | 47(61.8) | 5(16.7) | 5(16.7) |

| 8 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 | 9(10.1) | 47(61.8) | 5(16.7) | 7(23.3) |

| 9 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3ζ | 9(10.1) | 48(63.2) | 5(16.7) | 7(23.3) |

| 10 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 | 12(13.6) | 48(63.2) | 5(16.7) | 7(23.3) |

| 11 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 IMP1 | 12(13.6) | 50(65.8) | 7(23.3) | 7(23.3) |

| 12 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 IMP1 or c-Myc | 12(13.6) | 52(68.4) | 7(23.3) | 7(23.3) |

| 13 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 IMP1 or c-Myc or NPM1 | 14(15.9) | 53(69.7) | 7(23.3) | 8(26.7) |

| 14 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 IMP1 or c-Myc or NPM1 or p16 | 15(17.0) | 53(69.7) | 9(30.0) | 11(36.7) |

NHS: normal human sera; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; CH: chronic hepatitis; LC: liver cirrhosis

Subsequently, we evaluated the accuracy of these 14 TAA panel as the diagnostic biomarker platform for HCC (Table 4). The sensitivity in diagnosing HCC compared to normal individuals was from 21.1% for one TAA (CAPERα) to 69.7% when we added the TAAs stepwise to 14 TAAs, while the specificity decreased from 100% to 83%. The positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) for this 14 TAAs array was 77.9% and 76.3%, respectively.

Table 4.

Evaluation of the panel of 14 TAAs in the diagnosis of HCC (%).

| Antigens | HCC | NHS | Se | Sp | FP | FN | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 TAA | CAPERα | 21.2 | 0.0 | 21.1 | 100 | 0 | 78.9 | 100 | 59.7 | +∞ | 0.79 |

| 2 TAA | CAPERα or survivin | 36.8 | 1.1 | 36.8 | 98.9 | 1.1 | 63.2 | 96.6 | 64.7 | 33.45 | 0.64 |

| 3 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA | 39.5 | 3.4 | 39.5 | 96.6 | 3.4 | 60.5 | 90.9 | 65.2 | 11.62 | 0.63 |

| 4 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA orp62 | 44.7 | 5.6 | 44.7 | 94.4 | 5.6 | 55.3 | 87.2 | 66.7 | 7.98 | 0.59 |

| 5 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA orp62 or Koc | 52.6 | 5.6 | 52.6 | 94.4 | 5.6 | 47.4 | 88.9 | 70 | 9.39 | 0.50 |

| 6 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 | 55.3 | 6.7 | 55.3 | 93.3 | 6.7 | 44.7 | 87.5 | 70.9 | 8.25 | 0.48 |

| 7 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 | 61.8 | 10.1 | 61.8 | 89.9 | 10.1 | 38.2 | 83.9 | 73.4 | 6.12 | 0.42 |

| 8 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 | 61.8 | 10.1 | 61.8 | 89.9 | 10.1 | 38.2 | 83.9 | 73.4 | 6.12 | 0.42 |

| 9 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ | 63.2 | 10.1 | 63.2 | 89.9 | 10.1 | 36.8 | 84.2 | 74.1 | 6.26 | 0.41 |

| 10 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 | 63.2 | 13.6 | 63.2 | 86.4 | 13.6 | 36.8 | 80 | 73.3 | 4.65 | 0.43 |

| 11 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 IMP1 | 65.8 | 13.6 | 65.8 | 86.4 | 13.6 | 34.2 | 80.6 | 74.8 | 4.84 | 0.40 |

| 12 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 IMP1 or c-Myc | 68.4 | 13.6 | 68.4 | 86.4 | 13.6 | 31.6 | 81.3 | 76.2 | 5.03 | 0.37 |

| 13 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 IMP1 or c-Myc or NPM1 | 69.7 | 15.9 | 69.7 | 84.1 | 15.9 | 30.3 | 79.1 | 76.5 | 4.38 | 0.36 |

| 14 TAA | CAPERα or survivin or RalA or p62 or Koc or MDM2 or cyclin B1 or p53 or 14-3-3 ζ or p90 IMP1 or c-Myc or NPM1 or p16 | 69.7 | 17.0 | 69.7 | 83.0 | 17.0 | 30.3 | 77.9 | 76.3 | 4.10 | 0.37 |

NHS: normal human sera; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma;

Se: sensitivity=positive/Number of HCC cancer

Sp: specificity=positive/Number of NHS

FP: false positive=1-Sp

FN: false negative=1-Se

PPV: positive predictive value=Se/(Se+FP)

NPV: negative predictive value=Sp/(FN+Sp)

LR+: positive likelihood ratio=Se/(1-Sp)

LR−: negative likelihood ratio=(1-Se)/Sp

Likelihood ratios (LR) are the preferred diagnostic measures when the prevalence of disease is higher or lower than 50%. The range of LR+ is 1 (neutral) to infinity (very positive). The higher the LR+ for a diagnostic test, the greater the confidence we estimate a person as a true patient. The range of LR− is 0 (extremely negative) to 1 (neutral). The lower the LR−, the greater the confidence we judge a person who does not truly have the health problem [54]. The LR+ and LR− of 14 TAAs panel was 4.10 and 0.37, respectively, and the interpretation is that it is likely that a positive test comes from a person with HCC, and that a negative test is insufficient to rule out HCC.

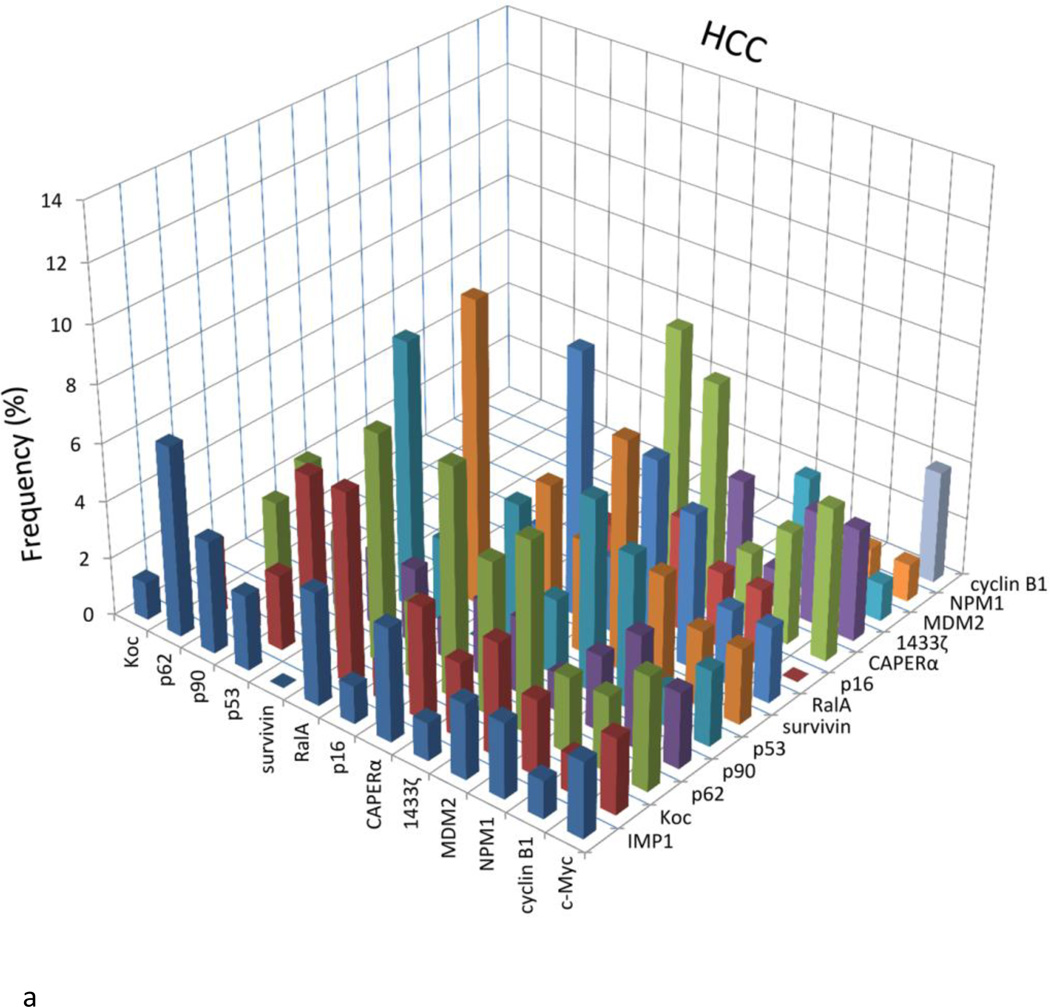

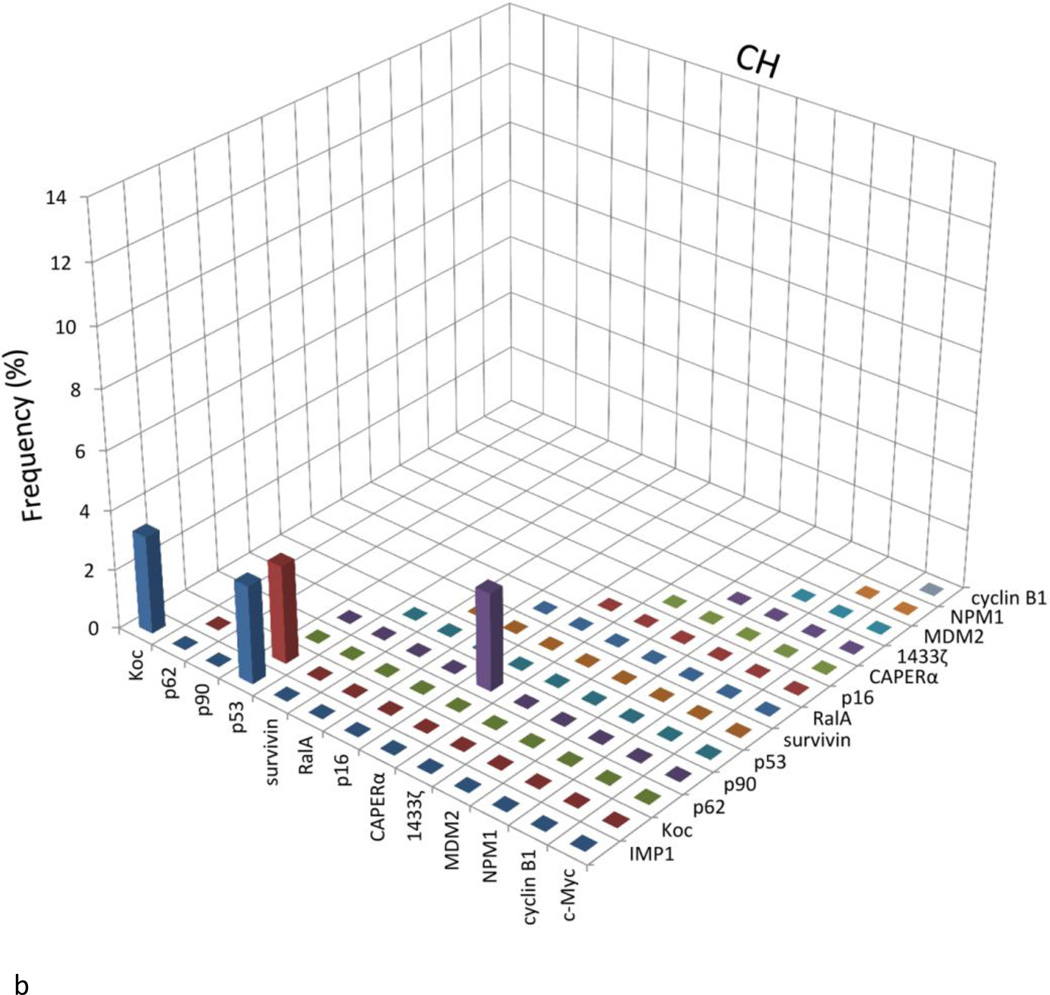

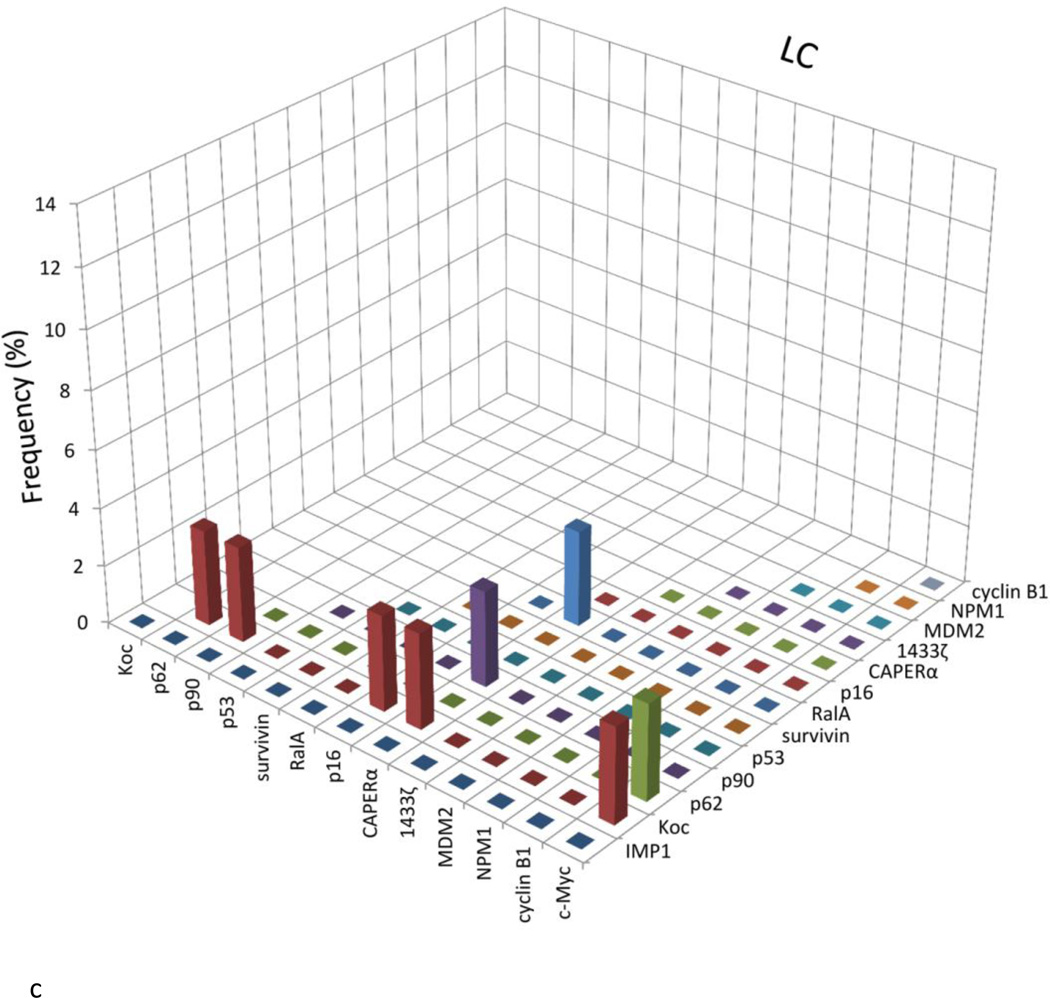

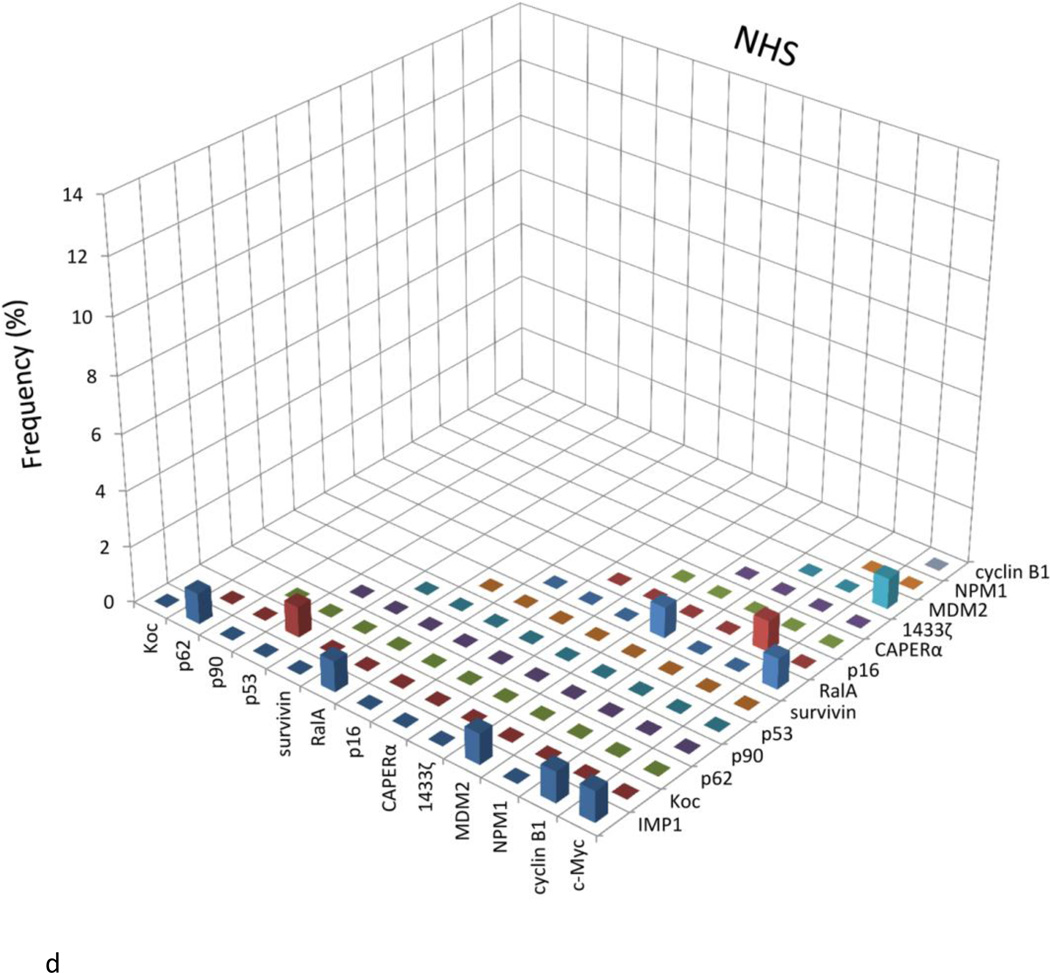

3.3. Preferential reactivity of HCC sera with certain antigens

Figure 3 presents an analysis of the data to determine whether there was coordinate or coupled expression of any two antibodies in the same serum. Because antibodies to CAPERα and survivin showed the highest frequency in HCC among 14 antibodies to TAAs, there was a possibility that these findings were related to coupled expression of some pairs of antibodies in the same serum. If there was significantly increased frequency of coordinate expression of two antibodies, this would be represented as higher frequency (percentage) in the bar graphs shown in Figure 3. Most of the normal human sera showed the absence of coexpression of antibodies to any combination of two of the 14 TAAs. Similar results were observed in chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis sera. There appeared to be increase in frequency of coexpressed antibodies survivin and CAPERα in HCC (5.3%), however, which did not reach statistical significance. Nevertheless, the frequency of HCC sera coexpressing antibodies to survivin and RalA was highest (10.5%) among all the combinations and statistically significant higher than NHS. Some other combinations of any two antibodies in HCC, such as anti-survivin with anti-Koc, anti-p53, anti-MDM2 or anti-RalA; anti-CAPERα with anti-RalA, anti-p62, anti-MDM2 or anti-1433 ζ, anti-RalA with anti-Koc or anti-p62, also showed the statistically significant increases compared to normal sera.

Figure 3.

Analysis to determine the presence or absence of co-expression of antibodies to any combination of two of the 14 TAAs. The height of the bar represents the percentage of sera with co-expression of two antibodies as, e.g., the presence of c-Myc antibody together with IMP1 antibody, c-Myc antibody with Koc antibody, and so on. NHS: Normal human sera; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; CH: Chronic hepatitis; LC: Liver cirrhosis

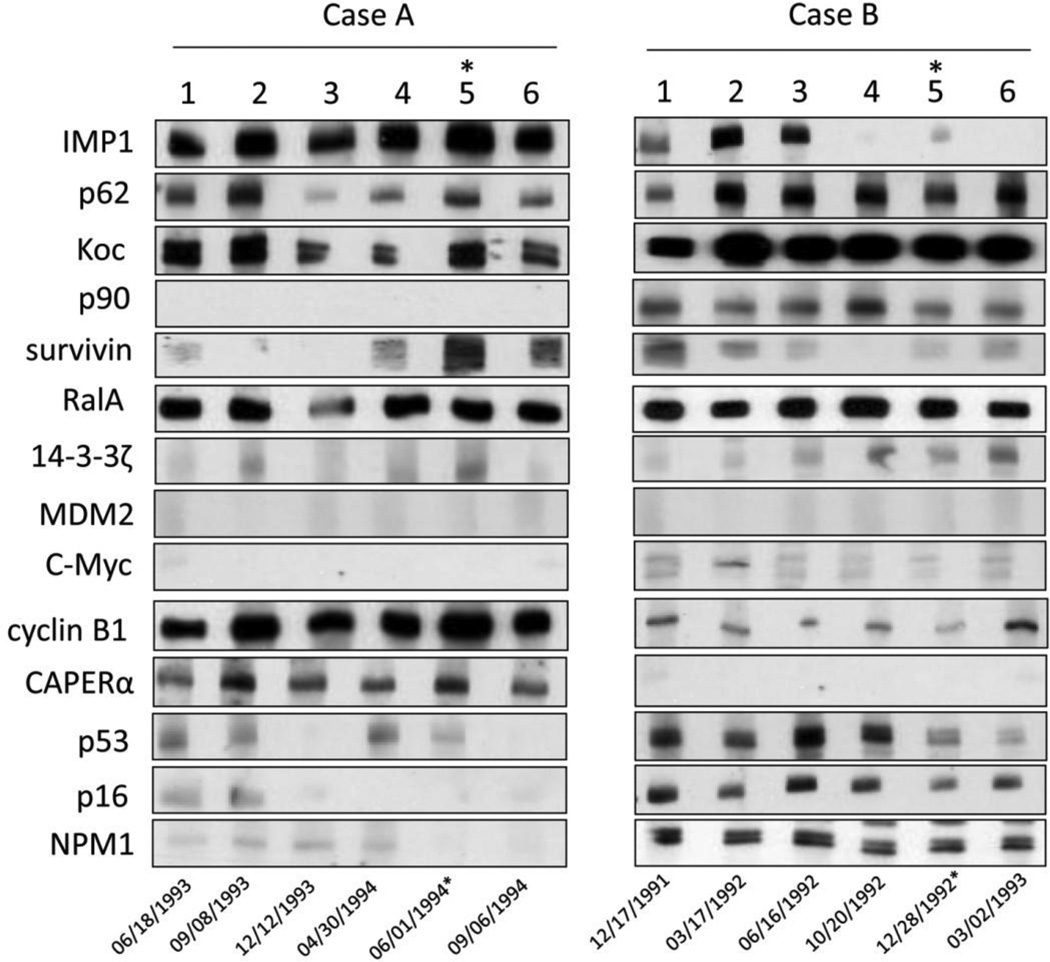

3.4. Autoantibodies against 14 TAAs can be detected at the early stage of HCC

Seventy-nine serial serum samples from 16 HCC patients were also available in the current study for the detection of autoantibodies against 14 TAAs. All these patients had been previously diagnosed as liver cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis and serum samples had been collected every three months before they were diagnosed as HCC. At least two to four samples before diagnosis were available for each patient. These are very valuable serial serum samples which are likely to represent early stage of HCC patients and the presence of autoantibodies in these samples might be biomarkers for early stage of HCC. The frequency of 14 anti-TAAs antibodies at the diagnostic time point ranged from 12.5% (Koc) to 50% (survivin and CAPERα), and most of these antibodies could be detected in 3 to 12 months before the diagnosis of HCC (Table 5). The interesting result was that the positive rate of autoantibodies was as high as 87.5% at the time point of one year before diagnosis when the panel of 14 TAAs was taken as the marker for detecting HCC.

Table 5.

Antibodies to 14 TAAs of serial sera from 16 HCC patients in different point time.

| Time point | survivin | CAPERα | RalA | p62 | Koc | MDM2 | cyclin B1 | p53 | 14-3-3ζ | p90 | IMP1 | c-Myc | NPM1 | p16 | Any(+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12m before diagnosis (n=8) | 1(12.5) | 1(12.5) | 1(12.5) | 2(25.0) | 2(25.0) | 0(0.0) | 1(12.5) | 1(12.5) | 0(0.0) | 1(13.0) | 2(25.0) | 1(12.5) | 1(12.5) | 1(9.1) | 7(87.5) |

| 9m before diagnosis (n=11) | 3(27.3) | 1(9.1) | 1(9.1) | 1(9.1) | 2(18.2) | 0(0.0) | 2(18.2) | 0(0.0) | 1(9.1) | 1(9.1) | 2(18.2) | 2(18.2) | 2(18.2) | 1(9.1) | 9(81.8) |

| 6m before diagnosis (n=15) | 1(6.7) | 2(13.3) | 1(6.7) | 1(6.7) | 2(13.3) | 1(6.7) | 2(13.3) | 1(6.7) | 2(13.3) | 1(6.7) | 2(13.3) | 5(33.3) | 3(20.0) | 4(26.7) | 12(80.0) |

| 3m before diagnosis (n=13) | 3(23.1) | 7(53.8) | 2(15.4) | 0(0.0) | 2(15.4) | 3(23.1) | 3(23.1) | 2(15.4) | 3(23.1) | 1(7.7) | 2(15.4) | 5(38.5) | 1(7.7) | 2(15.4) | 12(92.3) |

| diagnosis time point (n=16) | 8(50.0) | 8(50.0) | 4(25.0) | 5(31.3) | 2(12.5) | 4(25.0) | 6(37.5) | 4(25.0) | 5(31.3) | 4(25.0) | 3(18.8) | 5(31.3) | 3(18.8) | 6(37.5) | 13(81.3) |

Figure 4 shows the variation of autoantibodies titers and profiles in two representative patients. Patient A (Figure 4-Case A) and patient B (Figure 4-Case B) presented different autoantibody profiles by Western blotting assay. Patient A had autoantibodies to IMP1, Koc, CAPERα, RalA, cyclin B1 and p62, whereas patient B had autoantibodies to IMP1, p62, Koc, p90, survivin, RalA, cyclin B1, p53, p16 and NPM1. All of these anti-TAAs occurred one year before diagnosis of HCC, however the titers of different antibodies were variable during the year before diagnosis. Immunofluorescence staining of Hep2 cancer cells with sera at the different time points showed changing patterns of nuclear and cytoplasmic confirming the Western blotting data demonstrating variability in the anti-TAA response during this period. These observations show that anti-TAAs can vary in antibody specificity and titer during the one-year period prior to clinical diagnosis and also suggests that this immunodiagnostic approach may be exploited for early diagnosis of HCC.

Figure 4.

The expression of autoantibodies for the representative HCC patients with serial bleeding serum samples.

Case A and case B are two representative patients with serial serum samples. Number 1–6 stand for six time point of sample collection.

For case A, 1: 6/18/1993; 2: 9/8/1993; 3: 12/17/1993; 4: 3/30/1994; 5: 6/1/1994; 6: 9/6/1994. For case B, 1: 12/17/1991; 2: 3/17/1992; 3: 6/16/1992; 4: 10/20/1992; 5: 11/24/1992; 6: 3/2/1993.

*: time point of HCC diagnosis

3.5. Simultaneous use of both AFP and mini-array of 14 TAAs as markers in HCC detection

Serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) is a fetal glycoprotein produced by yolk sac and fetal liver and has been widely used as a serum marker for diagnosis of HCC. The sensitivity of AFP has been reported to be about 60% in HCC [55]. In the present study, 43 o 76 HCC sera were available for studies to determine the relationship of AFP to anti-TAA responses (Table 6). Twenty-seven of 43 (62.8%) HCC sera had abnormal serum AFP level (>100ng/ml). The sensitivity of AFP alone as marker in HCC detection was consistent with the previous report [55]. Of interest was that 7 of 16 (43.8%) HCC sera with normal AFP level (<100 ng/ml) were autoantibody positive to the 14 TAA array. If both 14 anti-TAAs and AFP were simultaneously used as diagnostic markers, 34 (13+14+7) of 43 (79.1%) HCC patients could be correctly identified. Elevated AFP and anti-TAA appear to be independent but supplementary serological markers for the diagnosis of HCC.

Table 6.

Sensitivity of combined use of both AFP and 14 anti-TAAs in HCC detection.

| 14 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| anti-TAAs | |||

| AFP levels | Positive | Negative | Total |

| >100 ng/ml | 14(A) | 13(B) | 27 |

| <100 ng/ml | 7(C) | 9(D) | 16 |

| Total | 21 | 22 | 43 |

Sensitivity (%) of AFP=A+B/(A+B+C+D)=27/43=62.8%

Sensitivity (%) of 14 TAAs=(A+C)/(A+B+C+D)=21/43=48.8%

Sensitivity (%) of combined both AFP and 14 TAAs=(A+B+C)/(A+B+C+D)=34/43=79.1%

4. Discussion

There is clear evidence that the immune system, in addition to defending us against pathogens, is also on guard against other threats, including tumors [56,57]. The generation of circulating antibodies that bind self-protein can be regarded as the systemic amplification by the immune system of a signal that indicates the presence of the tumor [58,59]. A major issue in the field of cancer immunodiagnosis is the definition of what constitutes a TAA. It is erroneous to include all cellular antigens identified by autoantibodies in cancer sera as TAAs, since some autoantibodies may exist in conditions that pre-date malignancy. Many antibodies to autologous cellular proteins can be detected in the sera of patients with cancer, and these reactive antigens have been called TAAs without considering the possibility that the autoantibodies might have existed in the patient before cancer. It indicates that autoantibodies from a cancer patient obtained at only one time point would not necessarily represent immune responses to a TAA. Failing to recognize the likelihood of pre-malignant circulating antibodies would result in the inclusion of many antigens erroneously as TAAs. Further research should be needed to establish true tumor-related antigens and to exclude those that might have been present prior to malignancy. In the further analysis, anti-TAA autoantibodies may become useful diagnostic biomarkers only after it has undergone extensive trials with many cancer sera and also with many non-cancer control sera [5].

Many investigators have been interested in the use of autoantibodies as serological markers for cancer immunodiagnosis, especially because of the general absence or a significantly lower frequency of these autoantibodies in normal individuals and in non-cancer conditions [11,51,60–62]. The drawback for this approach is the low sensitivity when a single or individual TAA is used to determine the presence or absence of an autoimmune response in cancer. This drawback can be overcome by using a panel of carefully selected TAAs to increase the sensitivity and specificity, which deals with the concept of “cancer immunomics” [13,51,63]. In terms of “immunomics”, there are two strategies based on the aims: either to discover new putative biomarkers (autoantigens and autoantibodies) called as “discovery-driven immunomics”, or the aim is to assess the relevance of putative markers already described as “hypothesis-driven immunomics”. The latter one can potentially use two main approaches: immunotests (from classical ELISA to protein biochips) and research of autoantigens using a peptide signature [64]. Wang et al. developed a phage-display library derived from prostate cancer tissue, and a phage protein microarray, to analyze autoantibodies in serum samples from patients with prostate cancer and controls [11]. In this study, a 22-phage-peptide detector was constructed for prostate cancer screening, with 81.6% sensitivity and 88.2% specificity. Similar to our study, a decision tree was constructed to classify prostate cancer by a five-TAAs-panel using ELISA, with 79% sensitivity and 86% specificity [65]. The findings of Wang et al. as well as our panel of TAAs are not fully optimal with respect to sensitivity for adoption in a screening program, and could be improved by the inclusion of additional tumor antigens.

It is crucial for potential biomarkers to be validated by using independent techniques such as immunochemical measurement or protein arrays [64]. Several distinct research areas are needed to identify and define relevant autoantigens, including discovery of candidate autoantigens and characterization of the sensitivity and specificity of reactivity against individuals or combinations of candidate autoantigens in cohorts of patients and controls.

The judicious selection of antigens to be included in panels or arrays of TAAs is extremely important because not all cellular proteins recognized as antigens by cancer sera are cancer specific. This was especially apparent in studies in HCC, where it was possible to analyze sera from the same HCC patients many months or years preceding malignancy when the patients have liver cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis, and autoimmune liver disease. In the present study, a total of 14 TAAs were selected to comprise a mini-array approach to detect anti-TAAs autoantibodies in 76 patients with HCC. Six of these 14 TAAs, including RalA, CIP2A/p90, CAPERα, MDM2, NPM1, 14-3-3 ζ were newly added to this TAA array, and the other eight TAAs were same ones as used in our previous study [13]. RalA, CIP2A/p90 and CAPERα were identified and evaluated as TAAs in the previous studies [6–8,24]. Mouse double minute 2 homolog protein (MDM2), also known as E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, is an important negative regulator of p53 tumor suppressor [38,66]. Nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1), known as nucleolar phosphoprotein B23 or numatrin, a multifunctional nucleolar protein, has emerged as a p14ARF binding protein and regulator of p53 [67]. 14-3-3 ζ belongs to the 14-3-3 family of proteins which mediate signal transduction by binding to phosphoserine-containing proteins and acts as a suppressor of apoptosis and has a central role in tumor genesis and progression [68]. The results have shown that all these six TAAs can induce relatively higher antibody responses ranging from 10.5% to 21.1% in HCC than that in normal individuals. The frequency of autoantibodies against 14 TAAs in autoimmune diseases such as SLE and PSS were as low as that in NHS, and it was significantly lower than that in HCC sera. The frequency of autoantibodies to 14 TAAs in HCC sera ranged from 5.6% to 21.1%, and the cumulative frequency was 69.7% while using a combination of the 14 TAAs. Of interest is that some of these anti-TAAs autoantibodies can be detected at least one year before the diagnosis of HCC. This indicates that the panel of 14 TAAs as targets for detection of autoantibodies might be used as valuable biomarkers for the early diagnosis of HCC. In our previous study [69], we have investigated another group of HCC patients, and found that 7 of 8 HCC patients with autoantibodies against multiple TAAs had normal range of serum AFP levels. Six of these 8 HCC patients with anti-TAAs antibodies were also confirmed to have well- to moderately differentiated HCC with comparatively small nodules of HCC (<30mm). In the present study, 43.8 percent of HCC sera with normal AFP level had anti-TAAs autoantibodies. The results have further supported our previous hypothesis that anti-TAAs antibodies may be used as supplementary serological markers for the diagnosis of HCC, especially for the AFP-negative cases.

Recent studies on genetic abnormalities in cancer have elucidated many of the observed immunological reactions described above. In breast and colorectal cancers, a typical tumor contains two to eight ‘driver gene’ mutations which modulate or alter signaling pathways [70,71] so that even at the gene level alone without considering epigenetic factors, a multiple number of mutations is required to establish tumorigenecity. These observations have been widely confirmed in many other tumor types and might be the reason for the immune system of the patient responding accordingly by making multiple immune responses manifested as multiple autoantibodies to TAAs. Other observations on the de-novo appearance of anti-TAA antibodies coincident with clinical detection of cancer may be relevant to the concept of synthetic lethality in cancer [72,73]. This concept is based on studies in yeast and Drosophila which showed that when two genes are synthetic lethal, mutation in one gene alone is non-lethal, but simultaneous mutation in both genes is lethal. This concept has been expanded to include the condition called synthetic sickness/lethality. An example is where mutation of the breast tumor suppressor genes BRCA1/2 is synthetically lethal with simultaneous inhibition of the DNA repair enzyme Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 [73]. Other examples include the observation that KRAS-mutant but not wild type colon cancer cells were synthetic lethal when coupled with inhibition of proteasome chymotrypsin-like activity [74]. In studies of serial serum samples from HCC patients, autoantibodies could be detected during preceding chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis but coincident with transition to HCC, new autoantibodies appeared, a sequence which was observed in the patient whose serum was used to isolate CAPERα [6] and in several other patients [75]. This event could represent immune system sensing a ‘second hit’ in the synthetic lethality paradigm.

In summary, this study further demonstrates that malignant transition in HCC can be associated with autoantibody responses to certain cellular proteins which might have some role in tumorigenesis, and suggests that a mini-array of multiple carefully selected TAAs can enhance antibody detection for immunodiagnosis of HCC. As noted in this study, our efforts were aimed at increasing both the sensitivity and specificity of antibodies as markers in HCC detection to include antigens which might be more selectively associated with HCC and not with others. According to the data in the present study, we thought that our TAAs array might be used as a novel non-invasive approach to identify HCC at early stages in individuals who have high risk of HCC, such as patients with chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis. We conclude that multiple anti-TAAs antibody detections improve predictive accuracy even if further work would be necessary to validate the detection of anti-TAAs autoantibodies as a clinically reliable approach. A comprehensive analysis and evaluation of various combinations of selected antibody-antigen systems will be useful for the development of autoantibody profiles involving different panels or arrays of TAAs in the future, and the results could be useful for diagnosis of specific types of cancers.

Highlights.

Autoantibody frequency to any individual TAA in HCC varied from 6.6% to 21.1%.

The sensitivity of 14 TAAs for HCC was 69.7% and useful for detection of HCC.

TAA mini-array is a powerful tool in detection of patients with AFP negative.

This study deals with the concept of “cancer immunomics”.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant (SC1CA166016) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We also thank the Border Biological Research Center (BBRC) Core Facilities at The University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) for their support, which were funded by RCMI-NIMHD-NIH grant (8G12MD007592).

Abbreviations

- ABTS

2,2’-azino-bis (3-ethyl-benzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt

- AFP

alpha-fetoprotein

- CH

chronic hepatitis

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FN

false negative

- FP

false positive

- GST

glutathione S transferase

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- LC

liver cirrhosis

- LR

likelihood ratio

- LR+

positive likelihood ratio

- LR−

negative likelihood ratio

- NHS

normal human sera

- NPV

negative predictive value

- OD

optical density

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PBST

PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PPV

positive predictive value

- PSS

progressive systemic sclerosis

- Se

sensitivity

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- Sp

specificity

- TAAs

tumor-associated antigens

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42(5):1208–1236. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houghton AN. Cancer antigens: immune recognition of self and altered self. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180(1):1–4. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Old LJ, Chen YT. New paths in human cancer serology. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187(8):1163–1167. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan EM, Zhang J. Autoantibodies to tumor-associated antigens: reporters from the immune system. Immunol. Rev. 2008;222:328–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang JY, Tan EM. Autoantibodies to tumor-associated antigens as diagnostic biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma and other solid tumors. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2010;10(3):321–328. doi: 10.1586/erm.10.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai H, et al. Novel nuclear autoantigen with splicing factor motifs identified with antibody from hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92(5):2419–2426. doi: 10.1172/JCI116848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang JY, et al. A novel cytoplasmic protein with RNA-binding motifs is an autoantigen in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189(7):1101–1110. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soo Hoo L, et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel 90 kDa 'companion' auto-antigen of p62 overexpressed in cancer. Oncogene. 2002;21(32):5006–5015. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brichory FM, et al. An immune response manifested by the common occurrence of annexins I and II autoantibodies and high circulating levels of IL-6 in lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98(17):9824–9829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171320598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stockert E, et al. A survey of the humoral immune response of cancer patients to a panel of human tumor antigens. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187(8):1349–1354. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, et al. Autoantibody signatures in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353(12):1224–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canelle L, et al. An efficient proteomics-based approach for the screening of autoantibodies. J Immunol Methods. 2005;299(1–2):77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang JY, et al. Antibody detection using tumor-associated antigen mini-array in immunodiagnosing human hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2007;46(1):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Covini G, et al. Immune response to cyclin B1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1997;25(1):75–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan EM. Antinuclear antibodies: diagnostic markers for autoimmune diseases and probes for cell biology. Adv. Immunol. 1989;44:93–151. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen J, et al. A family of insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding proteins represses translation in late development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19(2):1262–1270. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammerle M, et al. Posttranscriptional destabilization of the liver-specific long noncoding RNA HULC by the IGF2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) Hepatology. 2013;58(5):1703–1712. doi: 10.1002/hep.26537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell JL, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BPs): post-transcriptional drivers of cancer progression? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70(15):2657–2675. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1186-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai N, et al. mTOR phosphorylates IMP2 to promote IGF2 mRNA translation by internal ribosomal entry. Genes Dev. 2011;25(11):1159–1172. doi: 10.1101/gad.2042311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lochhead P, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 2 messenger RNA binding protein 3 (IGF2BP3) is a marker of unfavourable prognosis in colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2012;48(18):3405–3413. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Junttila MR, et al. CIP2A inhibits PP2A in human malignancies. Cell. 2007;130(1):51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JS, et al. CIP2A modulates cell-cycle progression in human cancer cells by regulating the stability and activity of Plk1. Cancer Res. 2013;73(22):6667–6678. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sablina AA, et al. The tumor suppressor PP2A Abeta regulates the RalA GTPase. Cell. 2007;129(5):969–982. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang K, et al. Immunogenicity of Ra1A and its tissue-specific expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22(3):735–743. doi: 10.1177/039463200902200319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bodemann BO, White MA. Ral GTPases and cancer: linchpin support of the tumorigenic platform. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(2):133–140. doi: 10.1038/nrc2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westermarck J. Regulation of transcription factor function by targeted protein degradation: an overview focusing on p53, c-Myc, and c-Jun. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;647:31–36. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-738-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dang CV. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell. 2012;149(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson ME, Howerth EW. Survivin: a bifunctional inhibitor of apoptosis protein. Vet. Pathol. 2004;41(6):599–607. doi: 10.1354/vp.41-6-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan BM, et al. Survivin: a new target for anti-cancer therapy. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2009;35(7):553–562. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coumar MS, et al. Treat cancers by targeting survivin: just a dream or future reality? Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013;39(7):802–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pines J, Hunter T. Human cyclins A and B1 are differentially located in the cell and undergo cell cycle-dependent nuclear transport. J. Cell Biol. 1991;115(1):1–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ersvaer E, et al. Cyclin B1 is commonly expressed in the cytoplasm of primary human acute myelogenous leukemia cells and serves as a leukemia-associated antigen associated with autoantibody response in a subset of patients. Eur. J. Haematol. 2007;79(3):210–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aitken A. 14-3-3 proteins: a historic overview. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2006;16(3):162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murata T, et al. 14-3-3zeta, a novel androgen-responsive gene, is upregulated in prostate cancer and promotes prostate cancer cell proliferation and survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5617–5627. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neal CL, et al. Overexpression of 14-3-3zeta in cancer cells activates PI3K via binding the p85 regulatory subunit. Oncogene. 2012;31(7):897–906. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu J et al. 14-3-3zeta Cooperates with ErbB2 to promote ductal carcinoma in situ progression to invasive breast cancer by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(3):195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rayburn E, et al. MDM2 and human malignancies: expression, clinical pathology, prognostic markers, and implications for chemotherapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5(1):27–41. doi: 10.2174/1568009053332636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wade M, et al. MDM2, MDMX and p53 in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(2):83–96. doi: 10.1038/nrc3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin JJ, et al. Natural product MDM2 inhibitors: anticancer activity and mechanisms of action. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;19(33):5705–5725. doi: 10.2174/092986712803988910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kruse JP, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell. 2009;137(4):609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown CJ, et al. Awakening guardian angels: drugging the p53 pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(12):862–873. doi: 10.1038/nrc2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheok CF, et al. Translating p53 into the clinic. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(1):25–37. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dowhan DH, et al. Steroid hormone receptor coactivation and alternative RNA splicing by U2AF65-related proteins CAPERalpha and CAPERbeta. Mol. Cell. 2005;17(3):429–439. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang G, et al. CAPER-alpha alternative splicing regulates the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor(1)(6)(5) in Ewing sarcoma cells. Cancer. 2012;118(8):2106–2116. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sherr CJ. The INK4a/ARF network in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(10):731–737. doi: 10.1038/35096061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rayess H, et al. Cellular senescence and tumor suppressor gene p16. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;130(8):1715–1725. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romagosa C, et al. p16(Ink4a) overexpression in cancer: a tumor suppressor gene associated with senescence and high-grade tumors. Oncogene. 2011;30(18):2087–2097. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Z, Hann SR. The Myc-nucleophosmin-ARF network: a complex web unveiled. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(17):2703–2707. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.17.9418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grisendi S, et al. Nucleophosmin and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(7):493–505. doi: 10.1038/nrc1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Falini B, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with mutated nucleophosmin (NPM1): is it a distinct entity? Blood. 2011;117(4):1109–1120. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-299990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang JY, et al. Enhancement of antibody detection in cancer using panel of recombinant tumor-associated antigens. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(2):136–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y, et al. Autoantibodies to tumor-associated antigens combined with abnormal alpha-fetoprotein enhance immunodiagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2010;289(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Himoto T, et al. Significance of autoantibodies against insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding proteins in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2005;26(2):311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Merrill RM. Introduction to epidemiology. 6th ed. Burlington, Mass: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daniele B, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein and ultrasonography screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl 1):S108–S112. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tan EM. Autoantibodies as reporters identifying aberrant cellular mechanisms in tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108(10):1411–1415. doi: 10.1172/JCI14451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finn OJ. Immune response as a biomarker for cancer detection and a lot more. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353(12):1288–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe058157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canevari S, et al. 1975–1995 revised anti-cancer serological response: biological significance and clinical implications. Ann. Oncol. 1996;7(3):227–232. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a010564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Purcell AW, Gorman JJ. Immunoproteomics: Mass spectrometry-based methods to study the targets of the immune response. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3(3):193–208. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R300013-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shan Q, et al. A cancer/testis antigen microarray to screen autoantibody biomarkers of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;328(1):160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sun Y, et al. SOX2 autoantibodies as noninvasive serum biomarker for breast carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(11):2043–2047. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zayakin P, et al. Tumor-associated autoantibody signature for the early detection of gastric cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;132(1):137–147. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paradis V, Bedossa P. In the new area of noninvasive markers of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2007;46(1):9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caron M, et al. Cancer immunomics using autoantibody signatures for biomarker discovery. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(7):1115–1122. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R600016-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koziol JA, et al. Recursive partitioning as an approach to selection of immune markers for tumor diagnosis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9(14):5120–5126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oliner JD, et al. Amplification of a gene encoding a p53-associated protein in human sarcomas. Nature. 1992;358(6381):80–83. doi: 10.1038/358080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gjerset RA. DNA damage, p14ARF, nucleophosmin (NPM/B23), and cancer. J Mol Histol. 2006;37(5–7):239–251. doi: 10.1007/s10735-006-9040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niemantsverdriet M, et al. Cellular functions of 14-3-3 zeta in apoptosis and cell adhesion emphasize its oncogenic character. Oncogene. 2008;27(9):1315–1319. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Himoto T, et al. Analyses of autoantibodies against tumor-associated antigens in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2005;27(4):1079–1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wood LD, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318(5853):1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vogelstein B, et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaelin WG., Jr The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(9):689–698. doi: 10.1038/nrc1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brough R, et al. Searching for synthetic lethality in cancer. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011;21(1):34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steckel M, et al. Determination of synthetic lethal interactions in KRAS oncogene-dependent cancer cells reveals novel therapeutic targeting strategies. Cell Res. 2012;22(8):1227–1245. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Imai H, et al. Increasing titers and changing specificities of antinuclear antibodies in patients with chronic liver disease who develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930101)71:1<26::aid-cncr2820710106>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]