Abstract

Background

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an insulin resistance disease that can progress to cirrhosis or liver failure.

Hypothesis

In NAFLD, insulin resistance dysregulates lipid metabolism, increasing production of cytotoxic lipids including ceramides, which exacerbate hepatic insulin resistance and injury.

Methods

Long Evans rats were pair-fed low (LFD) or high (HFD) fat diets for 8 weeks. Livers were used to measure lipids, gene expression, insulin receptor binding, integrity of insulin signaling, and pro-inflammatory cytokines. In vitro experiments characterized effects of ceramides on Huh7 cell viability, mitochondrial function, and insulin signaling.

Results

HFD feeding caused NAFLD with peripheral and hepatic insulin resistance, increased hepatic expression of pro-ceramide genes, sphingomyelinase activity, and lipid peroxidation, and increased serum ceramide. Ceramide treatment impaired Huh7 cell viability, mitochondrial function, and insulin signaling.

Conclusions

Increased hepatic ceramide generation and release may mediate both hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance in NAFLD.

Key Terms: Insulin resistance, NASH, obesity, diabetes, ceramide, high fat diet

INTRODUCTION

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), metabolic syndrome, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are major insulin resistance diseases whose world-wide prevalence rates are currently on the rise. T2DM is a systemic disease characterized by hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and peripheral insulin resistance, and frequently associated with obesity. Metabolic syndrome develops in the context of visceral obesity, and is associated with T2DM, dyslipidemia and hypertension 1, 2. NAFLD is a spectrum of diseases, ranging from simple hepatic steatosis to NASH, and is not associated with liver infection or a history of excessive alcohol consumption 1. NAFLD is characterized by hepatocellular lipid accumulation, mainly in the form of triglycerides, resulting in greater than 5–10% increases in liver weight 2. NAFLD afflicts between 10 and 30 percent of the general population, and 50 to 70 percent of obese individuals 1, 3. Although hepatic steatosis is considered a benign and reversible condition, nearly one-third of NAFLD cases eventually progress to steatohepatitis or NASH.

NASH is a more serious disease state relative to simple hepatic steatosis due to superimposed inflammation, on-going cell death, increased pro-inflammatory cytokine activation, oxidative stress, organelle dysfunction, particularly mitochondria, and fibrogenesis 3–5. A diagnosis of NASH sounds alarm because of the increased risk of progressing to hepatic fibrosis, cirrhosis, and finally end-stage liver disease 6–8. Moreover, NASH is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma 6, 7. The combined outcomes of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma have contributed to the increased rates of liver-related morbidity and mortality in Europe and North America 9, 10. Factors governing progression of NAFLD to NASH are not well understood, but roles have been suggested for lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, cytokine activation, and other pro-inflammatory mediators 11, 12.

Lipotoxicity is a state of cellular dysfunction caused by intracellular lipid overload that activates stress signaling pathways and pro-inflammatory cytokines, increases production of reactive oxygen species and toxic lipid intermediates, and inhibits mitochondrial β-oxidation 2, 13. Although fatty acids are widely recognized as mediators of lipotoxicity 14, more recently, roles for sphingolipids and ceramides have been suggested 15–21. Ceramides comprise a family of lipids generated from fatty acid and sphingosine 22. Ceramides are distributed in cell membranes, and in addition to their structural functions, they regulate intracellular signaling pathways that mediate growth, proliferation, motility, adhesion, differentiation, senescence, and apoptosis 21, 23–25. Ceramides can be generated biochemically by: 1) de novo synthesis through ceramide synthase and serine palmitoyltransferase mediated condensation of serine and palmitic acids 22; 2) hydrolysis of sphingomyelin through activation of neutral or acidic sphingomyelinases 26; or 3) degradation of complex sphingolipids and glycosphingolipids localized in late endosomes and lysosomes 27. Inhibition of ceramide synthesis or its accumulation prevents obesity-mediated insulin resistance 16, 28. Ceramides adversely alter cellular function and cause apoptosis by modulating phosphorylation states of proteins, including those that regulate insulin signaling 24, activating enzymes such as interleukin-1β converting enzyme (ICE)-like proteases, which promote apoptosis 27, or inhibiting Akt phosphorylation and kinase activity through activation of protein phosphatase 2A 29.

In obesity, adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and liver exhibit major abnormalities in sphingolipid metabolism that result in increased ceramide production, inflammation, and activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and impairments in glucose homeostasis and insulin responsiveness 21, 30, 31. In humans with NASH 32, and the C57BL/6 mouse model of diet-induced obesity with T2DM and NASH 31, ceramide levels in adipose tissue are elevated due to increased activation of serine palmitoyltransferase, and acidic and neutral sphingomyelinases 27. In both genetic and diet-induced obesity, ceramide accumulation in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue may be responsible for the associated insulin resistance 19, 31, 32. However, NAFLD and NASH are not always associated with obesity or T2DM. Whether ceramides generated and accumulated in liver mediate hepatic insulin resistance and govern progression of NAFLD to NASH is not known. We explored this question using an experimental model of chronic high fat diet feeding.

METHODS

Animal model

Adult Long Evans male rats (n = 8 per group) were pair-fed for 8 weeks with high fat (HFD) or low fat (LFD) chow diets. The HFD supplied 60% of the kcal in fat (54% from lard, 6% from soybean oil), 20% in carbohydrates, and 20% in protein, whereas the LFD supplied 10% of the kcal in fat (4.4% from lard, 5.6% from soybean oil), 70% in carbohydrates, and 20% in protein. The HFD had 300.8 mg/kg of cholesterol, while the LFD contained 18 mg/kg of dietary cholesterol. Rats were weighed weekly, and food consumption was monitored daily. After an overnight fast, rats were sacrificed, and blood or serum was harvested to measure glucose, ALT, insulin, and lipids. Livers were removed and portions were snap-frozen and stored at −80°C, or fixed in Histochoice and embedded in paraffin. Histological sections (5 μM thick) were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). Our experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Lifespan-Rhode Island hospital, and conforms to the guidelines set by the National Institute of Health.

Assessments of peripheral insulin resistance

Insulin sensitivity was evaluated at the end of the feeding period in rats anesthetized with 60 mg/kg i.p. pentobarbital. For glucose tolerance test (GTT), rats were fasted overnight fast, then administered a single i.p. injection of 2 g/kg D-glucose. For the insulin tolerance test (ITT) rats were fasted for 4 hours, then administered 0.5 U/kg i.p. human regular insulin. In both studies, glucose was measured in tail vein blood obtained at baseline, and 15, 30, 60, 120, and 180 minutes after glucose or insulin administration using a glucose meter (OneTouch Ultra, Lifescan Inc., Milpitas, CA). Responses were analyzed using the area-under-curve method, and inter-group comparisons were made using the Student T-test.

Lipid and protein adduct assays

To assess the role of adducts as mediators of oxidative stress and insulin resistance, we measured malondialdehyde (MDA) using the MDA-586 kit, and protein carbonylation using the OxyBlot assay. Carbonyl dot blot assay results were normalized to total protein spotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Proteins were detected with SYPRO Ruby and quantified by digital imaging (Kodak Digital Science Image Station, Rochester, NY).

Lipid studies

Lipids were chloroform-methanol (2:1) extracted from fresh frozen tissue 33. Total lipid content was measured using the Nile Red microplate assay 34, and fluorescence (Ex 485/Em 572) was measured in a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA). Serum triglycerides, cholesterol, and free fatty acid levels were measured using commercially available kits, and results were normalized to liver sample weight or by protein content in the homogenate used for the extraction. Liver ceramide immunoreactivity was measured by dot blot analysis 35. Serum ceramide immunoreactivity was measured by direct-binding ELISA.

Gene and Protein Studies

Total RNA isolated from liver tissue using Qiazol, was reverse transcribed using random oligodeoxynucleotide primers and the AMV 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis kit. The cDNA templates were used to measure gene expression by quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis using gene-specific primer pairs (Supplementary Table 1) as previously described 33,36.

Direct Binding Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA): Tissue homogenates were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors 33. Protein homogenates (50 ng/100 μl) were adsorbed to bottom well surfaces (MaxiSorp 96-well plates), then blocked with 1% BSA in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Samples were incubated with primary antibody (0.1–0.4 μg/ml) for 1 hour at 37°C, and immunoreactivity was detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and Amplex UltraRed soluble fluorophore.

Capture ELISAs measured pro-inflammatory cytokines. Capture antibodies (1 μg/ml) were adsorbed to the well bottoms as described above. 50 ng of liver homogenate were added in 100 μl, and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was detected with biotinylated antibodies (0.2 μg/ml for IL-1β and TNFα, and 0.5 μg/ml for IL-6), HRP-conjugated Streptavidin, and Amplex UltraRed. Fluorescence was measured (Ex 568/Em 581) in a SpectraMax M5. Binding specificity was determined from parallel control reactions with primary or secondary antibodies omitted. Immunoreactivity was normalized to protein content in parallel wells as determined with the NanoOrange Protein Quantification Kit.

Multiplex ELISAs were employed to examine the integrity of signaling through the insulin and IGF-1 receptors and downstream through IRS-1 and Akt. We used bead-based assays to measure total insulin receptor (IR), IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R), IRS-1, Akt, proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa (PRAS40), ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K), and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β), and phosphorylated proteins, i.e. pYpY1162/1163-IR, pYpY1135/1136-IGF-1R, pS312-IRS-1, pS473-Akt, pT246-PRAS40, pTpS421/424-p70S6K, and pS9-GSK3β, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and as previously reported 37.

Receptor binding assays

Competitive equilibrium binding assays were used to examine effects of HFD feeding on insulin and IGF-I receptor binding as indices of insulin and IGF-1 resistance. To measure total binding, NP-40 lysis buffer homogenates were incubated with 50 nCi/ml (2000 Ci/mmol; 50 pM) of [125I]-labeled insulin or IGF-I in binding buffer 36. Non-specific binding was measured in identical reactions containing 0.1 mM of unlabeled ligand. After 16-hours incubation at 4°C, reactions were vacuum harvested (FilterMate Harvester, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) onto 96-well GF/C filters pre-soaked in 0.33% polyethyleneimine. [125I]-bound insulin or IGF-I was measured in a TopCount (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Specific binding was calculated by subtracting non-specifically bound from the total bound isotope.

Cell culture experiments

Human Huh7 hepatoma cells were maintained as previously described 38. 96-well cultures were treated with 0–100 μM ceramide analogs C2Cer or C6Cer, or the inactive C2DCer. After 48 hours, mitochondrial activity was measured by the MTT assay, and viability, mitochondrial mass, and ATP content were measured using the CyQuant, MitoTracker Green, and ATPLite assays, respectively 39, 40. Sub-confluent 6-well cultures were treated with C2Cer, C6Cer, C2DCer, or vehicle for 5 hours (less than the time needed to cause cell death), and stimulated with insulin (10 nM) or vehicle for 10 minutes. Cell homogenates were used in direct binding ELISAs (see above) to measure immunoreactivity to GSK-3β, pSer9-GSK-3β, Akt, and pThr308-Akt.

Statistical analysis

Data depicted in the graphs and tables represent the means ± S.E.M’s for each group. Inter-group comparisons between the HFD and LFD groups were made using Student t-tests. Comparisons in cell culture assays were made using one- or two-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnet’s multiple comparison tests. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Computer software generated P-values are shown over the graphs.

RESULTS

HFD feeding causes peripheral insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis

Chronic HFD feeding increased mean body weight (P=0.008), and elevated fasting blood glucose (P=0.01) and serum insulin (P=0.006) (Table 1). Area-under-curve analyses for changes in blood glucose or insulin over time demonstrated higher blood glucose levels in HFD relative to LFD controls. Therefore, the chronic HFD feeding caused peripheral insulin resistance and a pre-diabetic state. Although body mass was only 11.3% higher in the HFD compared to control rats, chronic HFD feeding caused striking increases in visceral fat such that all abdominal organs were encased in adipose tissue. HFD feedings did not cause hyperlipidemia; instead, the mean serum level of total lipid was reduced (Nile Red assay; P=0.02), while mean serum triglyceride and free fatty acid (data not shown) levels were similar to control (Table 1). Livers of HFD fed rats had increased mean total lipid (P=0.0006) and triglyceride (P=0.001) levels, but similar cholesterol content relative to control (Table 1). In contrast to the intact liver histology with regular chord architecture, minimal hepatocellular steatosis, and absent inflammation observed in LFD-fed controls, livers of HFD fed rats had conspicuously increased macro-vesicular and micro-vesicular steatosis with mild disorganization of hepatic cord architecture, and scattered foci of lymphomononuclear cell inflammation, but no evidence of necrosis, apoptosis, or fibrosis (Supplementary Figure 1). Therefore, in this model, chronic HFD feeding caused modest but statistically significant body weight gain, peripheral insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis without hyperlipedemia or hepatitis.

Table 1.

High Fat Diet Feeding Causes Type 2 Diabetes and Hepatic Steatosis

| Low Fat Diet | High Fat Diet | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Weight (g) | 391.8 ± 11.4 | 441.9 ± 13.2 | 0.008 |

| Blood Glucose (mg/dl) | 108.2 ± 3.2 | 121.2 ± 3.5 | 0.01 |

| Serum Insulin (ng/ml) | 0.41 ± 0.10 | 1.23 ± 0.26 | 0.006 |

| GTT (mg/dl-AUC) | 33474 ±3212 | 44421 ± 2684 | 0.0129 |

| ITT (ng/ml-AUC) | 20953 ± 882 | 27745 ± 1125 | 0.0004 |

| Serum Lipids and ALT | |||

| Nile Red (FLU/μl) | 246.0 ± 31.3 | 174.4 ± 7.03 | 0.02 |

| Triglycerides (mg/ml) | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.30 ± 0.06 | |

| ALT (U/l) | 19.27 ± 1.06 | 29.43 ± 1.6 | 0.0001 |

| Hepatic Lipids | |||

| Nile Red (FLU/mg) | 103.2 ± 10.5 | 205.0 ± 21.1 | 0.0006 |

| Triglycerides (μM/g) | 28.8 ± 3.8 | 54.4 ± 4.8 | 0.001 |

| Cholesterol (μg/mg) | 125.3 ± 9.7 | 115.6 ± 0.5 | |

Adult male Long Evans rats were maintained on a high fat (60% of calories) or low fat (10% of calories) diet for 8 weeks (N=8 per group). After an overnight fast, rats were sacrificed and liver and blood were harvested immediately. Blood or serum was used to measure glucose, insulin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total lipid (Nile Red assay), triglycerides, cholesterol, and free fatty acid levels. In addition, peripheral insulin resistance was assessed with glucose (GTT) and insulin (ITT) tolerance tests (see Methods), and Area-under-curve analysis was used for inter-group comparisons, and performed with blood glucose levels measured from 0–180 minutes after bolus injection of glucose (GTT) or insulin (ITT). Liver lipid extracts were used to measure lipid content, triglycerides, and cholesterol and normalized by protein content in the homogenate used for the extraction. Data depict the mean ± S.E.M. results for each group. Inter-group comparisons were made using Student T-tests, and significant P-values are listed.

HFD feeding and pro-inflammatory cytokines

We assessed the potential role of pro-inflammatory cytokine activation in HFD-induced NAFLD by measuring IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 mRNA by qRT-PCR analysis, and their immunoreactivities by capture ELISA (Table 2). We detected paradoxically lower levels of IL-1β (P=0.04) and TNF-α (P=0001) mRNA, and TNF-α (P<0.0001) and IL-6 (P<0.0001) immunoreactivity in HFD relative to LFD livers, and similar levels of IL-6 mRNA and IL-1β immunoreactivity in the two groups. Therefore, pro-inflammatory cytokine responses in HFD rat livers were either suppressed or unchanged relative to control.

Table 2.

Effect of High Fat Diet on Hepatic Cytokine Expression

| Hepatic Cytokines | Low Fat Diet | High Fat DIet | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA/18S rRNA* | |||

| IL-1β | 0.048 ± 0.004 | 0.034 ± 0.005 | 0.04 |

| TNF-α | 0.020 ± 0.002 | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 0.001 |

| IL-6 | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.0005 | |

| ELISA (RFU) | |||

| IL-1β | 756.6 ± 12.8 | 774.2 ± 13.8 | |

| TNF-α | 974.7 ± 27.7 | 780.7 ± 19.1 | <0.0001 |

| IL-6 | 1076.0 ± 19.9 | 881.2 ± 12.4 | <0.0001 |

Adult male Long Evans rats were maintained on a high fat (60% of calories) or low fat (10% of calories) diet for 8 weeks (N=8 per group). Livers were harvested immediately after sacrifice. The mRNA levels of Il-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 were measured by qRT-PCR analysis, and corresponding immunoreactivity was assessed by capture ELISA with Amplex UltraRed fluorescence detection. Values represent relative fluorescence light units (RFU, Ex 568/Em 581). The mRNA results are normalized to 18S rRNA measured in the same samples (see Methods). Data depict the mean ± S.E.M. results for each group. Inter-group comparisons were made using Student T-tests, and significant P-values are listed.

HFD causes hepatic insulin and IGF-1 resistance

We used competitive equilibrium binding assays to assess insulin resistance in liver. Since IGF-1 utilizes similar and parallel signaling pathways 41 that could compensate for deficiencies in insulin signaling, we also measured IGF-1 receptor binding. Those studies revealed that chronic HFD feeding significantly reduced insulin (P=0.0009) and IGF-1 (P=0.0003) receptor binding (Figures 1A–1B). Furthermore, expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), a downstream target of insulin/IGF signaling, was reduced by HFD feeding (P<0.0001; Figure 1C), whereas β-actin was not (Figure 1D). Livers from HFD fed rats also had reduced expression of insulin (P=0.026) and IGF-1 (P=0.009) receptors, and Akt (P=0.014) relative to control (Table 3), and increased levels of p70S6K (P=0.038) and pSer 307-IRS-1 (P=0.022). The latter has an inhibitory effect on insulin signal transduction 42. On the other hand, immunoreactivity corresponding to most of the other phosphorylated molecules in the insulin/IGF-1 signaling cascade were not altered by chronic HFD feeding.

Figure 1.

Chronic HFD feeding impairs insulin and IGF-1 receptor binding in liver. Competitive equilibrium binding studies were performed with 8 liver protein homogenate samples per group from LFD or HFD fed rats. Reactions were incubated with 50 nCi/ml of [125I]-labeled insulin or IGF-1 (2000 Ci/mmol; 50 pM) in the presence or absence of 0.1 μM unlabeled ligand. Bound ligand was harvested onto 96-wells GF/C plates and measured in a TopCount machine. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting non-specifically bound from the total bound isotope. Box plots depict median (horizontal bar) ± 95% C.I.L. (upper and lower borders of boxes), and range (whiskers) of specific binding for (A) insulin and (B) IGF-1. (C) Insulin resistance was further assessed by measuring GAPDH immunoreactivity (ELISA). (D) β-actin was measured as a negative control (ELISA). Inter-group statistical comparisons were made using Student T-tests. Significant P-values are shown within the panels. RFU=relative fluorescence units.

Table 3.

Insulin/IGF-1 Pathway Analysis Through IRS-1, Akt and GSK-3β

| Total Protein* (RFU) | Low Fat Diet | High Fat Diet | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin Receptor | 343.3 + 11.49 | 297 + 16.81 | P=0.026 |

| IGF-1 Receptor | 282.4 + 11.74 | 221.3 + 14.90 | P=0.009 |

| IRS-1 | 501.3 + 11.58 | 473.3 + 26.52 | |

| Akt | 5092 + 213.2 | 4041 + 264.40 | P=0.014 |

| PRAS40 | 439.3 +14.56 | 437.6 + 17.66 | |

| p70S6K | 427.6 +28.01 | 398.5 +24.53 | |

| GSK-3β | 1189 + 179.3 | 949.5 + 143.9 |

| Phospho-Protein* (RFU) | Low Fat Diet | High Fat Diet | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| pYpY1162/1163-IR | 299.6 + 34.07 | 297.1 + 33.04 | |

| pYpY1135/1136-IGF-1 R | 130.9 + 12.08 | 122.3 + 6.15 | |

| pS312-IRS-1 | 219.8 + 10.51 | 202.5 + 6.33 | |

| pS473-Akt | 1104 + 110.9 | 1285 + 166.60 | |

| pT246-PRAS40 | 228.4 + 19.32 | 250.2 + 14.27 | |

| pTpS421/424-p70S6K | 138.2 + 28.84 | 275.9 + 51.18 | P=0.038 |

| pS9-GSK3β | 273.8 + 7.71 | 296.8 + 20.46 | |

| pS307-IRS1 | 8.204 + 0.26 | 8.781 + 0.09 | P=0.022 |

Adult male Long Evans rats were maintained on a high fat (60% of calories) or low fat (10% of calories) diet for 8 weeks (N=8 per group). The total and phosphorylated levels of key components of the insulin signaling pathway were measured in liver tissue homogenates via bead-based multiplex ELISA. Values represent relative fluorescence light units (RFU) after normalization for the amount of protein used for the assay. Data depict the mean ± S.E.M. results for each group. Inter-group comparisons were made using Student T-tests, and significant P-values are listed.

IR=insulin receptor, IGF-1R=IGF-1 receptor; IRS-1=insulin receptor substrate, type 1; PRAS40=Proline-rich Akt substrate of 40 kDa; p70S6K= 70 kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase; GSK-3β=glycogen synthase kinase-3β

Hepatic steatosis and pro-ceramide gene expression

We next examined the potential role of ceramides as mediators of hepatic insulin/IGF-1 resistance because: 1) ceramides are bioactive sphingolipids that regulate intracellular signaling and have a demonstrated role in promoting insulin resistance 21, 22, 43; 2) previous studies of obesity or HFD feeding revealed increased ceramide levels in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, both of which are highly insulin-responsive 24, 31, 44; and 3) de novo synthesis of ceramides is triggered by increased availability of fatty acids 23 (See Table 4). Our studies included qRT-PCR to measure expression of genes that regulate ceramide biosynthesis and degradation, enzymatic assays of neutral and acid sphingomyelinase activities, and ELISAs or dot blots to assay ceramide immunoreactivity in serum and liver.

Table 4.

Ceramide-Related Genes and Their Functions

| Abbreviation | Full name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| CER1 | ceramide synthase 1 (Lass1) | N-acylation of sphingoid long chain base with fatty acyl-CoAs (mainly C18) to form ceramide # |

| CER2 | ceramide synthase 2 (Lass2) | N-acylation of sphingoid long chain base with fatty acyl-CoAs (mainly C20-26) to form ceramide # |

| CER4 | ceramide synthase 4 (Lass4) | N-acylation of sphingoid long chain base with fatty acyl-CoAs (mainly C24) to form ceramide # |

| SMPD1 | sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1, acid lysosomal | Synthesis of ceramide from sphingomyelin (lysosomal) |

| SMPD3 | sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 3, neutral | Synthesis of ceramide from sphingomyelin (plasma membrane) |

| UGCG | UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase | Synthesis of glucosyl ceramide |

| CERD1 | N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase (acid ceramidase) | Hydrolysis of ceramide to sphingosine (lysosomal) $ |

| CERD2 | N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase 2 (neutral ceramidase) | Hydrolysis of ceramide to sphingosine (plasma membrane) $ |

| CERD3 | N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase 3-like (alkaline ceramidase 2) | Hydrolysis of ceramide to sphingosine (Golgi apparatus) $ |

| SPTLC | serine palmitoyltransferase, | Catalyses the first step of de novo ceramide synthesis |

| N-SMase | sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 3, neutral | Synthesis of ceramide from sphingomyelin |

| A-SMase | sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1, acid lysosomal | Synthesis of ceramide from sphingomyelin |

Ref: Mao C.Ceramidases: regulators of cellular responses mediated by ceramide, sphingosine and sphingosine 1-phosphate. Biochimica and biosphysica Acta (2008) 424–434

Laviad EL. Characterization of ceramide synthase 2. JBC (2008) 283,9:5677–5684

Hannun YA. Principles of bioactive lipid signaling:lessons from sphingolipids. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2008) February

Exploratory qRT-PCR analyses demonstrated that Ceramide Synthase (Cer) 1, 2 and 4, acidic and neutral isoforms of sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase (sphingo-myelinase; SMPD1 and SMPD3), UDP glucose ceramide glycosyltransferase (UGCG), serine palmitoyl transferase (SPTLC) 1 and 2, and ceramidase (CERD) 2 and 3 were abundantly expressed in liver. CER 1, 2, and 4, and SPTLC2 mRNAs were all significantly increased in HFD relative to LFD livers (Figure 2). In contrast, UGCG and SPTLC1 were expressed at similar levels in the two groups. Among genes involved in lipid degradation, CERD2, CERD3, SMPD1, and SMPD3 genes were all expressed at higher in HFD compared with LFD livers (Figures 3A–3D). Enzymatic assays demonstrated higher levels of acidic sphingomyelinase (P=0.01), but not neutral sphingomyelinase activity in the HFD group (Figures 3E–3F). Therefore, chronic HFD feeding significantly increased hepatic expression of genes that generate ceramides by N-acylation of sphingosine through the actions of ceramide synthases 23, hydrolysis of sphingomyelin via sphingomyelinases 27, and condensation of palmitic acid and serine through the catalytic action of SPTLC2. However, HFD feeding did not increase the non-regulated SPTLC1 subunit, or UGCG, the rate-limiting enzyme glucosylceramide, which is needed for de novo ceramide synthesis, and is dysregulated in humans with NAFLD 45. Finally, we measured significantly higher ceramide levels in HFD serum, and although ceramide levels were also higher in HFD livers, the difference from control did not reach statistical significance (Figures 3G–3H).

Figure 2.

Effects of chronic HFD feeding on expression of pro-ceramide genes-biosynthetic pathways. RNA extracted from HFD and LFD rat livers (N=8/group) was used to measure gene expression by qRT-PCR analysis with gene-specific primer pairs (See Methods and Supplementary Table 1). Gene expression was normalized to 18S rRNA. Box plots depict relative levels of gene expression for (A–C) Ceramide synthases (CER) 1, 2, 4, (D, E) serine palmitoyl transferases (SPTLC), and (F) UDP glucose ceramide glycosyltransferase (UGCG). Inter-group comparisons were made using Student t-tests. Significant P-values are shown over the graphs.

Figure 3.

Effects of chronic HFD on expression of (A–D) ceramide-related genes and (E, F) enzymatic activity-degradation pathways from sphingomyelin, and (G, H) ceramide levels in liver and serum. HFD and LFD liver RNA was used in qRT-PCR analyses (N=8/group) (See Methods and Supplementary Table 1). (A–D) Ceramidase (CERD) and (C, D) sphingomyelinase mRNA transcript levels were normalized to 18S rRNA. (E) Acidic and (F) neutral sphingomyelinase activities were measured using a commercial assay. Ceramide immunoreactivity was measured in (G) liver by dot-blot analysis, and (H) serum by ELISA. Box plots show data corresponding to (A–D) relative levels of gene expression, (E, F) sphingomyelinase activity, and (G, H) immunoreactivity. Inter-group comparisons were made using Student t-tests. Significant P-values are shown above the bars. RLU=relative luminescence units; D.U.= densitometry units.

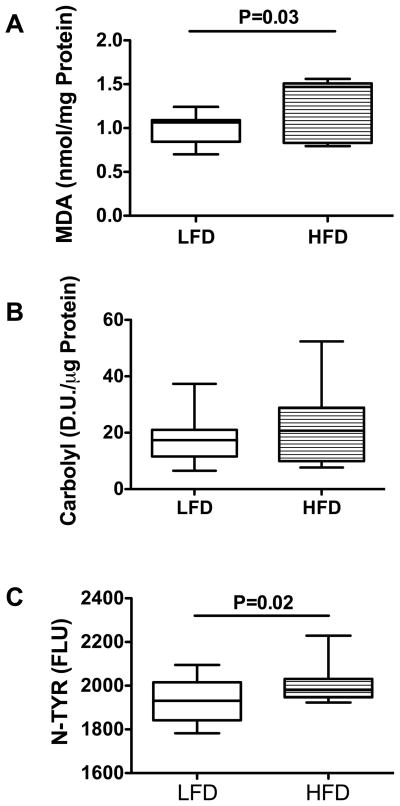

Chronic HFD feeding increases oxidative stress and lipid adducts

Ceramides promote insulin resistance and oxidative stress 16–21, 46, 47. Persistent oxidative stress increases formation and accumulation of lipid, protein, and DNA adducts, which impair cellular functions and promote cellular degeneration and death. To determine the degree to which HFD-mediated hepatic insulin resistance, pro-ceramide gene up-regulation, and increased ceramide production were associated with increased oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, we examined: 1) malondialdehyde (MDA); 2) protein carbonyls; and 3) 3-nitrotyrosine (N-Tyr) in liver. The mean MDA level, reflecting toxic aldehyde generated by reactive oxygen species attacks on lipids 48, was significantly higher in HFD compared with the LFD-fed controls (P=0.03; Figure 4A). Despite significantly higher mean hepatic triglyceride and MDA levels in the HFD-fed group, the calculated mean MDA/Triglyceride ratio was significantly lower in the HFD (0.128 ± 0.01) compared with the LFD (0.261 ± 0.02) (P=0.003) group, indicating that other factors in addition to hepatic triglyceride accumulation, govern formation of lipid adducts. The mean protein carbonyl levels were similar in livers of HFD- and LFD-fed rats (Figure 4B). NTyR, which marks protein nitrotyrosilation caused by peroxynitrite attack, and could interfere with protein phosphorylation/dephosporylation signaling and protein functions 49, 50, was significantly increased in livers of HFD- relative to LFD-fed control rats (P=0.02; Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Chronic HFD causes hepatic oxidative stress. (A) Malondialdehyde (MDA), (B) total carbonylated proteins, and (C) 3-nitrotyrosine (N-TYR) immunoreactivity were assayed in fresh frozen liver tissue as described (see Methods) and inter-group comparisons are shown with box plots. Inter-group comparisons were made with Student t-tests. Significant P-values are indicated within each panel. (D.U.=densitometry units; FLU= Fluorescence light units)

Ceramide-mediated hepatotoxicity and insulin resistance

Dose-response studies of mitochondrial function using the MTT assay demonstrated relative resistance of Huh7 cells to low concentrations (<10 μM) of C2, C6, or C2D (x48 h), but marked sensitivity to higher concentrations of C2 ceramide (Figure 5A). Further analyses of viability, mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial function were performed on cells treated with 50 μM ceramide for 48 h. Those studies demonstrated significantly reduced viability in C2Cer ≫ C6Cer treated relative to vehicle or C2DCer treated cultures (Figure 5B). Analysis of mitochondrial mass using the Mitotracker green (MTG) fluorescence assay revealed significantly increased MTG fluorescence, reflecting mitochondrial proliferation in C2Cer-treated relative to C6C, C2DCer, and vehicle-treated cultures (Figure 5C). Finally, assessments of viability with the CyQuant assay, and mitochondrial function using the ATPlite assay, revealed that C2Cer and C6Cer exposures significantly reduced viability and ATP production (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

In vitro ceramide exposure impairs mitochondrial function and causes cytotoxicity. Huh7 hepatic cells were exposed to different concentrations of C2Cer, C6Cer, C2DCer (inactive), or vehicle (0 point) for 48 hours. (A) Ceramide dose-effects on cell density and mitochondrial function using the MTT assay with absorbances measured at 540 nm. (B–D) Cells were exposed to 50 μM ceramide for 48 hours, and then used to measure (B) viability with the Cyquant (CYQ) assay, (C) mitochondrial mass by the Mitotracker Green (MTG) fluorescence, and (D) ATP using the ATPlite assay (RLU=relative light units). Box plots depict results from 8 replicate 96-well cultures. Absorbances, fluorescence intensity, and luminescence were measured in a Spectramax M5 microplate reader. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnet tests. Significant P-values are indicated within each panel.

Ceramides antagonize insulin signaling by activating protein phosphatase PP2A, resulting in dephosphorylation of PKB/AKT 20. To confirm that ceramides cause insulin resistance, we exposed Huh7 cells to C2Cer, C6Cer, C2DCer, or vehicle for 5 hours (much shorter than the 24–48 hours required to cause cytotoxicity or mitochondrial dysfunction), after which the cells were stimulated with insulin or vehicle for 10 minutes. GSK-3β, phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9) AKT and phospho-AKT (Thr308) levels were measured by direct binding ELISA. The mean levels and percentage increases in GSK-3β were significantly higher in insulin-stimulated C2Cer and C6Cer treated relative to their corresponding un-stimulated cultures (Figures 6A, 6B). Although the mean levels of phospho-GSK-3β were not significantly altered by insulin stimulation, C6Cer-treated cells had significant reductions in the relative levels of phospho-GSK-3β in paired assays (Figures 6C, 6D). Total Akt was significantly higher in insulin-stimulated C2Cer-treated relative to unstimulated cultures, and the mean percentage increases in insulin-stimulated total Akt were significantly higher in both C2Cer and C6Cer treated relative to vehicle-treated cells (Figures 6E, 6F). Finally, insulin stimulation significantly increased the mean levels of phospho-Akt in vehicle, C2DCer, and C2Cer, but not in C6Cer treated cells (Figure 6G); instead, insulin-stimulated C6Cer-treated cells had significant mean percentage reductions in phospho-Akt relative to vehicle-treated cells (Figure 6H).

Figure 6.

Short-term ceramide exposure impairs insulin signaling. Huh7 cells were treated with Vehicle, C2D (inactive), C2 or C6 (50 μM) ceramide for 5 hours, then stimulated with vehicle (−) or 10 nM insulin (+) for 10 minutes. Immunoreactivity to (A) total GSK-3β, (C) pSer9-GSK-3β (E) total AKT, or (G) pThr308-AKT was measured by ELISA using HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and the Amplex UltraRed soluble fluorophore. Fluorescence light units (FLU) were measured (Ex 568 nm/Em 581 nm) in a Spectramax M5. (B, D, F, H) Percentage increases in insulin-stimulated over basal immunoreactivity were calculated, and results are depicted using box plots. Inter-group comparisons were made using (A, C, E, G) two-way or (B, D, F, H) one-way ANOVAs with the post hoc Dunnet tests. Significant P-values are shown within each panel.

DISCUSSION

NAFLD and NASH, like T2DM and metabolic syndrome, are insulin resistance diseases, and they frequently overlap with T2DM or metabolic syndrome due to high co-morbidity rates with obesity. When associated with T2DM or metabolic syndrome, hepatic insulin resistance could be mediated by pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. However, in the absence of obesity, T2DM, or metabolic syndrome, which factors promote hepatic insulin resistance in NAFLD? One consideration is that steatosis-induced modifications of cell membrane lipid composition may impair insulin sensitivity 51–54. Herein, we investigated the potential role of toxic lipids, particularly ceramides, because, in both genetic and DIO models, ceramides accumulate in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, and they inhibit insulin signaling 24, 31, 55–57.

In our model of chronic HFD feeding, modest (11.3%) but significantly increased mean body weight was associated with visceral obesity, peripheral insulin resistance, and pre-T2DM. In contrast to related studies 58, the HFD-fed rats did not have hyperlipidemia or metabolic syndrome. Histopathologic, biochemical, and molecular studies confirmed the presence of significant hepatic steatosis with minimal inflammation, apoptosis, necrosis, and pro-inflammatory cytokine activation. Transition from simple hepatic steatosis to NASH has been linked to pro-inflammatory cytokine activation 11, 12, 59. Correspondingly, in our model, HFD produced NAFLD instead of NASH, perhaps due to the absence of inflammatory mediators in the steatotic livers. Although hyperlipidemia is considered to be risk factor for NAFLD 1, we found that NAFLD can occur despite a favorable serum lipid profile. While elevated ALT levels and peripheral insulin resistance may suffice to suspect a diagnosis of NAFLD, additional serum biomarkers are needed to detect and monitor NAFLD, and prevent its progression to NASH.

Hepatic insulin resistance in our model of NAFLD was associated with reduced insulin receptor binding, insulin receptor and Akt immunoreactivity, and GAPDH expression, and increased pS307-IRS-1. GAPDH is an important insulin-responsive gene 60, and phosphorylation of IRS-1 on S307 inhibits downstream signaling through IRS-1 42. In addition, we detected NAFLD-associated impairments in IGF-1 signaling manifested by reduced binding to the IGF-1 receptor and reduced IGF-1 receptor expression. In addition, we detected significantly increased levels of pTpS421/424-p70S6K in HFD-exposed livers, consistent with previous studies of diet-induced obesity 61, 62. The finding of similar mean levels of pYpY1162/1163-IR, pYpY1135/1136-IGF-1R, pS312-IRS-1, pS473-Akt, pT246-PRAS40, and pS9-GSK3β in livers of HFD and LFD fed rats indicates that, despite impairments in upstream signaling at the receptor level, compensatory measures may have minimized the net impairments in insulin/IGF-1 signaling. In this regard, the increased levels of pTpS421/424-p70S6K in HFD-exposed livers could reflect enhanced insulin/IGF-1 stimulated growth and metabolic functions mediated by increased signaling through PI3 kinase-Akt 63. Alternatively, the finding could represent activation of negative feedback on insulin signaling 61, 62, and thereby account for the increased serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 observed herein.

Although hepatic steatosis generally reflects storage of triglycerides in hepatocytes 64, there is growing evidence that other lipid species also accumulate 65 in relation to NAFLD/NASH. We interrogated whether the insulin resistance in experimental NAFLD was mediated by dysregulated sphingolipid metabolism, focusing on the role of ceramides. Ceramides are of interest because they: 1) have anti-growth properties and promote apoptosis and senescence; 2) activate protein phosphatases such as PP2A and PP1, which negatively regulate insulin signaling mechanisms 25; 3) induce insulin resistance by antagonizing PI3K/AKT 17, 18, 24; and 4) accumulate in insulin responsive tissues such as adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in diet-induced and genetic models of obesity/T2DM 24, 31, 66, and in obese humans 32, 44.

We found that NAFLD is associated with increased expression of multiple pro-ceramide genes, including those mediating de novo biosynthesis, hydrolysis of sphingomyelin, and the activity of ceramide synthases, consistent with recent findings67. These changes were associated with increased sphingomyelinase activity in liver, and ceramide levels in sera of HFD-fed rats, which could lead to worsening of hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance. Although there was a trend toward higher hepatic ceramide levels in the HFD group, the failure to detect significantly increased levels of ceramide in liver could have been due to rapid transport of ceramide into serum and subsequent trafficking to other tissues (see supplementary Figure 2) where they could exert toxic and degenerative effects, including insulin resistance 37, 68. Alternatively, the increased activation of ceramidases may have reduced net ceramide levels in liver. However, ceramidases convert ceramide to sphingosine, and sphingosine is cytotoxic and causes apoptosis 23. Sphingosine also antagonizes insulin signaling, glucose transport, and lipogenesis at the post receptor level 69, 70. On the other hand, over-expression of acid ceramidase, which degrades ceramide to sphingosine and fatty acids, protects cells from the inhibitory effects of palmitate and other long chain saturated FFAs on insulin signaling 28. In palmitate treated cells, acid ceramidase over-expression decreases ceramide, and increases its breakdown product sphingosine. These responses can restore insulin responsiveness in FA expose cells, and suggest that ceramides rather than sphingosine mediate insulin resistance.

In vitro experiments tested the hypothesis that bioactive toxic ceramides can mediate many of the adverse effects of chronic HFD feeding, including cytotoxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, ATP deficiency, and impaired insulin signaling through Akt and GSK-3β. The additional findings that ceramide exposure and insulin stimulation can modulate levels of total Akt or GSK-3β are consistent with emerging evidence that, besides phosphorylation, signaling through these molecules can be regulated by changes in their intracellular sequestration and accumulation 71, 72. The discrepancy with respect to ceramide inhibition of Akt phosphorylation in vitro but not in vivo could have been due to the absence of adaptive responses in acute compared with chronic ceramide exposure.

Roles for ceramide metabolites, e.g. glycosphingolipids, as mediators of insulin resistance and cytotoxicity have been demonstrated in experimental obesity and chronic HFD feeding 55, 57, 73. Chemical inhibition of glucosylceramide synthase in ob/ob mice, Zucker diabetic fatty rats, and 3T3-L1 adipocyte cultures reduces or reverses insulin signaling abnormalities, insulin resistance, and pro-inflammatory cytokine activation 55, 57. Herein, we measured UDP-glucose ceramide glucosyltransferase (UGCG) by qRT-PCR and found no significant elevation of its mRNA in the HFD group. Although UGCG expression is increased in NASH, our finding of non-elevated levels of UGCG suggests that glycosphingolipids may mediate transition from NAFLD to NASH. In addition, there is growing evidence that various sphingolipids incorporated into cell membrane lipid rafts which contain receptor tyrosine kinases, mediate insulin resistance and therefore represent potential pharmacotherapeutic targets 13. For example, sphingoid base 1-phosphate promotes oxidative stress, pro-apoptotic signaling, and cytotoxicity 74. Finally, ceramides themselves can cause insulin resistance, as demonstrated here and elsewhere 30, 32, 68, 75–77. Conceivably, a better understanding of the role of ceramides as mediators of insulin resistance will require characterization of the profiles associated with insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and cytotoxicity, and therefore mediating transition from NAFLD to NASH.

Ceramides cause cell death by activating pro-inflammatory cytokines and promoting oxidative stress. In our model of NAFLD, although we found no evidence of pro-inflammatory cytokine activation, several indices of oxidative stress including lipid peroxidation and peroxynitrite were elevated in the livers. Oxidative stress impairs insulin signaling, exacerbates insulin resistance 49, and promotes formation of DNA, protein and lipid adducts, which interfere with vital functions. Since stress induced adducts can bolster the transition from simple steatosis to NASH 78, in our model, the failure to progress from NAFLD to NASH may have been due to the modest accumulations of protein and lipid adducts.

In conclusion, chronic HFD feeding caused NAFLD with peripheral as well as hepatic insulin resistance, but with minimal evidence of inflammation. In vitro experiments support our hypothesis that increased activation of pro-ceramide mechanisms with attendant elevated levels of ceramides and other toxic lipids, e.g. sphingosine and glycosphingolipids in liver are key factors mediating hepatic insulin resistance in NAFLD. The data suggest that inflammation, cytokine activation, and increased stress may be required to promote transition from NAFLD to NASH. Given the elevated serum ceramide but not triglyceride levels in this model of chronic HFD with viscera-restricted obesity, we propose that serum ceramide levels may serve as peripheral non-invasive biomarkers of NAFLD. Therapeutic measures to inhibit hepatic production of ceramides and other toxic lipids may reduce the severity and progression of NAFLD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by AA-11431, AA-12908, and AA16126 from the National Institutes of Health

References

- 1.Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002 Apr 18;346:1221–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marra F, Gastaldelli A, Svegliati Baroni G, Tell G, Tiribelli C. Molecular basis and mechanisms of progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Trends Mol Med. 2008 Feb;14:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark JM. The epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006 Mar;40(Suppl 1):S5–10. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000168638.84840.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begriche K, Igoudjil A, Pessayre D, Fromenty B. Mitochondrial dysfunction in NASH: causes, consequences and possible means to prevent it. Mitochondrion. 2006 Feb;6:1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browning JD, Horton JD. Molecular mediators of hepatic steatosis and liver injury. J Clin Invest. 2004 Jul;114:147–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI22422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2005 Jul;129:113–21. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bugianesi E. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and cancer. Clin Liver Dis. 2007 Feb;11:191–207. x–xi. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jou J, Choi SS, Diehl AM. Mechanisms of disease progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2008 Nov;28:370–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim YS, Kim WR. The global impact of hepatic fibrosis and end-stage liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2008 Nov;12:733–46. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams R. Global challenges in liver disease. Hepatology. 2006 Sep;44:521–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter-Kent C, Zein NN, Feldstein AE. Cytokines in the pathogenesis of fatty liver and disease progression to steatohepatitis: implications for treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Apr;103:1036–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrell GC, Larter CZ. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from steatosis to cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2006 Feb;43:S99–S112. doi: 10.1002/hep.20973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson N, Borlak J. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets in steatosis and steatohepatitis. Pharmacol Rev. 2008 Sep;60:311–57. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malhi H, Gores GJ. Molecular mechanisms of lipotoxicity in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2008 Nov;28:360–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1091980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chavez JA, Knotts TA, Wang LP, et al. A role for ceramide, but not diacylglycerol, in the antagonism of insulin signal transduction by saturated fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2003 Mar 21;278:10297–303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holland WL, Brozinick JT, Wang LP, et al. Inhibition of ceramide synthesis ameliorates glucocorticoid-, saturated-fat-, and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2007 Mar;5:167–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland WL, Knotts TA, Chavez JA, Wang LP, Hoehn KL, Summers SA. Lipid mediators of insulin resistance. Nutr Rev. 2007 Jun;65:S39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pickersgill L, Litherland GJ, Greenberg AS, Walker M, Yeaman SJ. Key role for ceramides in mediating insulin resistance in human muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2007 Apr 27;282:12583–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straczkowski M, Kowalska I. The role of skeletal muscle sphingolipids in the development of insulin resistance. Rev Diabet Stud. 2008 Spring;5:13–24. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2008.5.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stratford S, Hoehn KL, Liu F, Summers SA. Regulation of insulin action by ceramide: dual mechanisms linking ceramide accumulation to the inhibition of Akt/protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 2004 Aug 27;279:36608–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406499200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Summers SA. Ceramides in insulin resistance and lipotoxicity. Prog Lipid Res. 2006 Jan;45:42–72. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cowart LA. Sphingolipids: players in the pathology of metabolic disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Jan;20:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008 Feb;9:139–50. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland WL, Summers SA. Sphingolipids, insulin resistance, and metabolic disease: new insights from in vivo manipulation of sphingolipid metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2008 Jun;29:381–402. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruvolo PP. Intracellular signal transduction pathways activated by ceramide and its metabolites. Pharmacol Res. 2003 May;47:383–92. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds CP, Maurer BJ, Kolesnick RN. Ceramide synthesis and metabolism as a target for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2004 Apr 8;206:169–80. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu B, Obeid LM, Hannun YA. Sphingomyelinases in cell regulation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1997 Jun;8:311–22. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chavez JA, Holland WL, Bar J, Sandhoff K, Summers SA. Acid ceramidase overexpression prevents the inhibitory effects of saturated fatty acids on insulin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005 May 20;280:20148–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalfant CE, Kishikawa K, Mumby MC, Kamibayashi C, Bielawska A, Hannun YA. Long chain ceramides activate protein phosphatase-1 and protein phosphatase-2A. Activation is stereospecific and regulated by phosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem. 1999 Jul 16;274:20313–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delarue J, Magnan C. Free fatty acids and insulin resistance. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007 Mar;10:142–8. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328042ba90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah C, Yang G, Lee I, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, Samad F. Protection from high fat diet-induced increase in ceramide in mice lacking plasminogen activator inhibitor 1. J Biol Chem. 2008 May 16;283:13538–48. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709950200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kolak M, Westerbacka J, Velagapudi VR, et al. Adipose tissue inflammation and increased ceramide content characterize subjects with high liver fat content independent of obesity. Diabetes. 2007 Aug;56:1960–8. doi: 10.2337/db07-0111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyn-Cook LE, Jr, Lawton M, Tong M, et al. Hepatic Ceramide May Mediate Brain Insulin Resistance and Neurodegeneration in Type 2 Diabetes and Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009 Apr;16:715–29. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMillian MK, Grant ER, Zhong Z, et al. Nile Red binding to HepG2 cells: an improved assay for in vitro studies of hepatosteatosis. In Vitr Mol Toxicol. 2001 Fall;14:177–90. doi: 10.1089/109793301753407948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brade L, Vielhaber G, Heinz E, Brade H. In vitro characterization of anti-glucosylceramide rabbit antisera. Glycobiology. 2000 Jun;10:629–36. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moroz N, Tong M, Longato L, Xu H, de la Monte SM. Limited Alzheimer-type neurodegeneration in experimental obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008 Sep;15:29–44. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Nguyen V, Setshedi M, Longato L, Wands JR. Ceramide-mediated insulin resistance and impairment of cognitive-motor functions. J Alzheimers Dis. 21:967–84. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cantarini MC, de la Monte SM, Pang M, et al. Aspartyl-asparagyl beta hydroxylase over-expression in human hepatoma is linked to activation of insulin-like growth factor and notch signaling mechanisms. Hepatology. 2006 Aug;44:446–57. doi: 10.1002/hep.21272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Chronic gestational exposure to ethanol impairs insulin-stimulated survival and mitochondrial function in cerebellar neurons. CMLS, Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:882–93. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8475-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soscia SJ, Tong M, Xu XJ, et al. Chronic gestational exposure to ethanol causes insulin and IGF resistance and impairs acetylcholine homeostasis in the brain. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006 Sep;63:2039–56. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6208-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baserga R. The contradictions of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Oncogene. 2000 Nov 20;19:5574–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Draznin B. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance: serine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 and increased expression of p85alpha: the two sides of a coin. Diabetes. 2006 Aug;55:2392–7. doi: 10.2337/db06-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraegen EW, Cooney GJ, Ye JM, Thompson AL, Furler SM. The role of lipids in the pathogenesis of muscle insulin resistance and beta cell failure in type II diabetes and obesity. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2001;109(Suppl 2):S189–201. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams JM, 2nd, Pratipanawatr T, Berria R, et al. Ceramide content is increased in skeletal muscle from obese insulin-resistant humans. Diabetes. 2004 Jan;53:25–31. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greco D, Kotronen A, Westerbacka J, et al. Gene expression in human NAFLD. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008 May;294:G1281–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00074.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andrieu-Abadie N, Gouaze V, Salvayre R, Levade T. Ceramide in apoptosis signaling: relationship with oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001 Sep 15;31:717–28. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teruel T, Hernandez R, Lorenzo M. Ceramide mediates insulin resistance by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in brown adipocytes by maintaining Akt in an inactive dephosphorylated state. Diabetes. 2001 Nov;50:2563–71. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.11.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grimsrud PA, Xie H, Griffin TJ, Bernlohr DA. Oxidative stress and covalent modification of protein with bioactive aldehydes. J Biol Chem. 2008 Aug 8;283:21837–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bashan N, Kovsan J, Kachko I, Ovadia H, Rudich A. Positive and negative regulation of insulin signaling by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Physiol Rev. 2009 Jan;89:27–71. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radi R. Nitric oxide, oxidants, and protein tyrosine nitration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Mar 23;101:4003–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Betschart JM, Virji MA, Perera MI, Shinozuka H. Alterations in hepatocyte insulin receptors in rats fed a choline-deficient diet. Cancer Res. 1986 Sep;46:4425–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruneau C, Hubert P, Waksman A, Beck JP, Staedel-Flaig C. Modifications of cellular lipids induce insulin resistance in cultured hepatoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987 May 18;928:297–304. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(87)90189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ikonen E, Vainio S. Lipid microdomains and insulin resistance: is there a connection? Sci STKE. 2005 Jan;25:2005, pe3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2682005pe3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nadiv O, Shinitzky M, Manu H, et al. Elevated protein tyrosine phosphatase activity and increased membrane viscosity are associated with impaired activation of the insulin receptor kinase in old rats. Biochem J. 1994 Mar 1;298( Pt 2):443–50. doi: 10.1042/bj2980443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aerts JM, Ottenhoff R, Powlson AS, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of glucosylceramide synthase enhances insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2007 May;56:1341–9. doi: 10.2337/db06-1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turinsky J, O’Sullivan DM, Bayly BP. 1,2-Diacylglycerol and ceramide levels in insulin-resistant tissues of the rat in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1990 Oct 5;265:16880–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao H, Przybylska M, Wu IH, et al. Inhibiting glycosphingolipid synthesis improves glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in animal models of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2007 May;56:1210–8. doi: 10.2337/db06-0719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Svegliati-Baroni G, Candelaresi C, Saccomanno S, et al. A model of insulin resistance and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in rats: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid treatment on liver injury. Am J Pathol. 2006 Sep;169:846–60. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Copaci I, Micu L, Voiculescu M. The role of cytokines in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. A review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006 Dec;15:363–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alexander MC, Lomanto M, Nasrin N, Ramaika C. Insulin stimulates glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene expression through cis-acting DNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jul;85:5092–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tremblay F, Marette A. Amino acid and insulin signaling via the mTOR/p70 S6 kinase pathway. A negative feedback mechanism leading to insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2001 Oct 12;276:38052–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Um SH, Frigerio F, Watanabe M, et al. Absence of S6K1 protects against age- and diet-induced obesity while enhancing insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2004 Sep 9;431:200–5. doi: 10.1038/nature02866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khamzina L, Veilleux A, Bergeron S, Marette A. Increased activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in liver and skeletal muscle of obese rats: possible involvement in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2005 Mar;146:1473–81. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagle CA, Klett EL, Coleman RA. Hepatic triacylglycerol accumulation and insulin resistance. J Lipid Res. 2008 Nov 6; doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800053-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Puri P, Baillie RA, Wiest MM, et al. A lipidomic analysis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2007 Oct;46:1081–90. doi: 10.1002/hep.21763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turinsky J, Bayly BP, O’Sullivan DM. 1,2-Diacylglycerol and ceramide levels in rat skeletal muscle and liver in vivo. Studies with insulin, exercise, muscle denervation, and vasopressin. J Biol Chem. 1990 May 15;265:7933–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chocian G, Chabowski A, Zendzian-Piotrowska M, Harasim E, Lukaszuk B, Gorski J. High fat diet induces ceramide and sphingomyelin formation in rat’s liver nuclei. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010 Feb 20; doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tong M, de la Monte SM. Mechanisms of ceramide-mediated neurodegeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009 Apr;16:705–14. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robertson DG, DiGirolamo M, Merrill AH, Jr, Lambeth JD. Insulin-stimulated hexose transport and glucose oxidation in rat adipocytes is inhibited by sphingosine at a step after insulin binding. J Biol Chem. 1989 Apr 25;264:6773–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smal J, De Meyts P. Sphingosine, an inhibitor of protein kinase C, suppresses the insulin-like effects of growth hormone in rat adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 Jun;86:4705–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gonzalez E, McGraw TE. Insulin-modulated Akt subcellular localization determines Akt isoform-specific signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Apr 28;106:7004–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901933106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Taylor AJ, Ye JM, Schmitz-Peiffer C. Inhibition of glycogen synthesis by increased lipid availability is associated with subcellular redistribution of glycogen synthase. J Endocrinol. 2006 Jan;188:11–23. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Langeveld M, Aerts JM. Glycosphingolipids and insulin resistance. Prog Lipid Res. 2009 May-Jul;48:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim DH, Lee YS, Lee YM, Oh S, Yun YP, Yoo HS. Elevation of sphingoid base 1-phosphate as a potential contributor to hepatotoxicity in fumonisin B1-exposed mice. Arch Pharm Res. 2007 Aug;30:962–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02993964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Deevska GM, Rozenova KA, Giltiay NV, et al. Acid Sphingomyelinase Deficiency Prevents Diet-induced Hepatic Triacylglycerol Accumulation and Hyperglycemia in Mice. J Biol Chem. 2009 Mar 27;284:8359–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807800200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kraegen EW, Cooney GJ. Free fatty acids and skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008 Jun;19:235–41. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000319118.44995.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Park MJ, Jung SR, Jung HL, Craig BW, Lee CD, Kang HY. Effects of 4 weeks recombinant human growth hormone administration on insulin resistance of skeletal muscle in rats. Yonsei Med J. 2008 Dec 31;49:1008–16. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2008.49.6.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Seki S, Kitada T, Sakaguchi H. Clinicopathological significance of oxidative cellular damage in non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Hepatol Res. 2005 Oct;33:132–4. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.