Abstract

Intra-neuronal metabolism of dopamine (DA) begins with production of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL), which is toxic. According to the ‘catecholaldehyde hypothesis,’ DOPAL destroys nigrostriatal DA terminals and contributes to the profound putamen DA deficiency that characterizes Parkinson’s disease (PD). We tested the feasibility of using post-mortem patterns of putamen tissue catechols to examine contributions of altered activities of the type 2 vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) to the increased DOPAL levels found in PD. Theoretically, the DA : DOPA concentration ratio indicates vesicular uptake, and the 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid : DOPAL ratio indicates ALDH activity. We validated these indices in transgenic mice with very low vesicular uptake (VMAT2-Lo) or with knockouts of the genes encoding ALDH1A1 and ALDH2 (ALDH1A1,2 KO), applied these indices in PD putamen, and estimated the percent decreases in vesicular uptake and ALDH activity in PD. VMAT2-Lo mice had markedly decreased DA:DOPA (50 vs. 1377, p < 0.0001), and ALDH1A1,2 KO mice had decreased 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid:DOPAL (1.0 vs. 11.2, p < 0.0001). In PD putamen, vesicular uptake was estimated to be decreased by 89% and ALDH activity by 70%. Elevated DOPAL levels in PD putamen reflect a combination of decreased vesicular uptake of cytosolic DA and decreased DOPAL detoxification by ALDH.

Keywords: DOPAC, DOPAL, dopamine, DOPET, monoamine oxidase, Parkinson’s disease

Severe depletion of the catecholamine, dopamine (DA), in the striatum (putamen and caudate) is the defining neurochemical characteristic of Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Ehringer and Hornykiewicz 1960; Hornykiewicz 1998). Understanding mechanisms of death of nigrostriatal catecholamine neurons should spur development of innovative diagnostic, treatment, and prevention strategies for this major neurodegenerative disease.

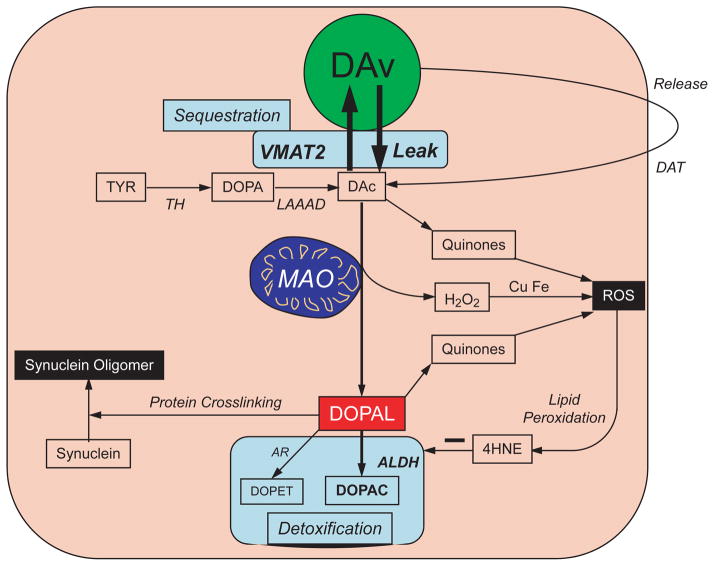

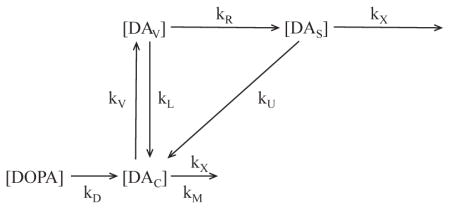

Intra-neuronal metabolism of DA begins with deamination catalyzed by monoamine oxidase-A in the outer mitochondrial membrane to form the catecholaldehyde, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) (Eisenhofer et al. 2004). Because of ongoing DA biosynthesis in the cytosol, leakage of vesicular DA stores into the same compartment, imperfect recycling from the cytosol back into the vesicles, and reuptake of DA released by exocytosis (Fig. 1), DOPAL is produced continuously in DA neurons.

Fig. 1.

Concept diagram about sources and metabolic fates of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) in dopaminergic neurons. Under resting conditions, most of the irreversible loss of dopamine (DA) from the neurons is because of passive leakage from vesicles (DAv) into the cytosol (DAc), followed by enzymatic deamination catalyzed by monoamine oxidase (MAO). Cytosolic DA is taken up into the vesicles via the type 2 vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2). Under resting conditions, release by exocytosis from the vesicles, with escape of reuptake via the cell membrane DA transporter (DAT), constitutes only a minor determinant of DA turnover. The loss of DA is balanced by ongoing catecholamine biosynthesis from the action of L-aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase on DOPA produced from tyrosine (TYR) by tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). The action of MAO on cytosolic DA produces the catecholaldehyde, DOPAL. DOPAL is detoxified mainly by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), to form the acid, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), with 3,4-dihydroxyph-enylethanol (DOPET) a minor metabolite formed via aldehyde/aldose reductase. Both DAc and DOPAL (and, at least theoretically, DOPAC and DOPET) spontaneously auto-oxidize to quinones, which augment generation of reactive oxygen species, resulting in lipid peroxidation. 4-Hydroxynonenal (4HNE), a major lipid peroxidation product, inhibits ALDH. DOPAL cross-links with proteins, augmenting oligomerization of alpha-synuclein. Tissue DOPAL : DA indicates DOPAL content adjusted for DA stores. As explained in the Appendix, DA : DOPA provides an index of vesicular uptake and DOPAC : DOPAL an index of ALDH activity.

DOPAL is toxic, both in vitro and in vivo (Panneton et al. 2010; Mattammal et al. 1995; Burke et al. 2004, 2003). The toxicity may occur by at least four mechanisms – protein cross-linking (Rees et al. 2009), oxidation to quinones (Anderson et al. 2011), production of hydroxyl radicals (Li et al. 2001), and augmentation of toxicity exerted by other agents (Marchitti et al. 2007). DOPAL also potently oligomerizes and precipitates alpha-synuclein (Burke et al. 2008), and alpha-synucleinopathy is implicated in PD pathogenesis (Singleton et al. 2003; Polymeropoulos et al. 1997; Satake et al. 2009). According to the ‘catecholaldehyde hypothesis’ (Goldstein et al. 2012b; Goldstein 2012), DOPAL causes or contributes to the loss of DA-containing terminals that characterizes PD.

We previously reported that post-mortem putamen tissue from PD patients contains an increased concentration of DOPAL relative to DA (Goldstein et al. 2011). Determinants of DOPAL buildup in PD remain unknown. Addressing this issue was the main purpose of this study.

As indicated in Fig. 1 and by the kinetic model in the Appendix, several processes potentially determine DOPAL levels in dopaminergic neurons. In this study we focused on vesicular uptake of cytosolic DA by the type 2 vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2) and metabolism of DOPAL by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). In PC12 cells, blockade of vesicular uptake and inhibition of ALDH both increase endogenous DOPAL levels (Goldstein et al. 2012b).

From the kinetic model in the Appendix we derived that the tissue DA : DOPA ratio provides an index of vesicular uptake and that 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) : DOPAL provides an index of ALDH activity. We validated these indices in striata of mice with very low VMAT2 activity (VMAT2-Lo) or double knockout of the genes encoding ALDH1A1 and 2 (ALDH1A1,2 KO). VMAT2-Lo mice are known to have decreased striatal DA : DOPAC (Taylor et al. 2009), but whether they have altered striatal DOPAL has not been reported. ALDH1A1,2 KO mice have decreased striatal DOPAC : DOPAL (Wey et al. 2012), but whether this reflects increased DOPAL, decreased DOPAC, or both has not been reported. We also predicted that ALDH1A1,2 KO mice have a buildup of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol (DO-PET), because of a shift from ALDH to aldehyde/aldose reductase (AR) in the metabolism of DOPAL.

We applied these indices of vesicular uptake and ALDH activity in post-mortem putamen tissue from PD patients and control subjects without neurological disorders and estimated the percentage changes in these processes in PD.

Methods

Sources of samples

Human brain tissue was from the posterior inferior putamen and mouse brain tissue from the striatum. All the animal research was done in compliance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Human brain tissue

Post-mortem brain neurochemical data were reviewed from 17 neuropathologically confirmed cases of end-stage idiopathic PD and 14 control subjects. The samples were provided by the University of Miami Brain Endowment Bank, which has IRB approval to obtain consents for brain donation and to acquire patient clinical records. For this study, de-identified specimens were used from an established biorepository of post-mortem brain tissues. The study was also conducted in accordance with guidance by the NCI/CCR/Laboratory of Pathology Tissue Resource Committee.

Post-mortem intervals (duration between death and brain freezing) were 24 h or less in all subjects. The control group was similar to the PD group in terms of age, gender makeup, ethnicity, and postmortem interval (Table 1). Among controls, the most frequent cause of death was cardiac (cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, coronary atherosclerosis or thrombosis, or congestive heart failure, n = 10). Other causes of death among controls were respiratory failure and pneumonia, lung cancer, gall bladder cancer, or blunt force trauma. Among PD patients, maximum levodopa daily doses at the time of death ranged from 0–1500 mg.

Table 1.

Mean (± SEM) putamen tissue concentrations and ratios of catechols in control subjects and patients with Parkinson’s disease

| Control (14) | PD (17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74 ± 2 | 77 ± 1 |

| Gender (% male) | 86% | 77% |

| PMI (hours) | 12.1 ± 1.5 | 8.9 ± 1.5 |

| DOPA | 1.76 ± 0.59 | 0.61 ± 0.12* |

| DA | 15.5 ± 2.09 | 1.00 ± 0.36**** |

| DOPAL | 0.496 ± 0.164 | 0.071 ± 0.036**** |

| DOPAC | 3.48 ± 0.66 | 0.164 ± 0.057**** |

| DOPET | 0.042 ± 0.013 | 0.007 ± 0.003*** |

| NE | 0.220 ± 0.034 | 0.054 ± 0.021**** |

| DHPG | 0.019 ± 0.003 | 0.004 ± 0.001**** |

| DOPAL : DA | 0.030 ± 0.006 | 0.144 ± 0.044** |

| DA : DOPA | 16.5 ± 2.86 | 1.90 ± 0.68**** |

| DOPAC : DOPAL | 11.3 ± 2.50 | 3.39 ± 0.60** |

| DOPAC : DA | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.10 |

| DOPET : DOPAC | 0.012 ± 0.002 | 0.122 ± 0.062* |

| NE : DHPG | 15.4 ± 3.45 | 10.8 ± 3.45 |

Different from control,

p < 0.05;

p < 0.001;

p < 0.001;

p < 0.0001.

Tissue concentrations are in pmol/mg wet weight.

Numbers of subjects are in parentheses.

VMAT2-Lo mice

Data were reviewed for seven mice with very low activity of the type 2 vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2-Lo) and from 21 control mice (Miller et al. 2001; Caudle et al. 2007). To create VMAT2-Lo mice, the VMAT2 locus (SLC18A2) was cloned from the 129/Sv genomic library and a 2.2 kb PvuII fragment from the third intron of the VMAT2 gene, and cloned into the blunt-ended NotI site of the construct (Caudle et al. 2007; Taylor et al. 2009). The targeting vector was introduced into 129/Ola CGR 8.8 embryonic stem cells and injected into blastocytes of C57BL/6 mice. Chimeric males (genotype confirmed by Southern blot analysis) were bred with C57BL/6 females. The procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University.

ALDH KO mice

Data were reviewed for a total of 34 mice with knockouts of the ALDH1A1 and ALDH2 genes and from 54 control mice that were heterozygotes or wild-type. ALDH1A1, ALDH2, and ALDH1,2 knockout mice were created and studied in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the South Texas Veterans Health Care System. Mice null for ALDH2 were generated by gene trap mutagenesis and backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for 10 generations. ALDH1A1 mutant mice were generated using a targeted deletion at exon 11 of the ALDH1A1 allele (Duester 2001) and backcrossed for eight generations to C57BL/6J. ALDH1A1 mutant mice were crossed with ALDH2 mutant mice to produce mice heterozygous for both genes (ALDH1A1,2 knockout). Cross-breeding of the mice heterozygous for ALDH1A1 and ALDH2 mutations generated the line homozygous for mutations in both genes and the wild-type line on an identical genetic background. The two lines were maintained by breeding male and female mice for each line. Male mice of three different age groups (young, 5–8 months; middle-aged, 12–14 months; and old, 18–27 months) were used. In this study the data for ALDH1A1,2 KO and control mice in these age groups were combined.

Catechol assay

The same personnel (P.S.) conducted the tissue catechol assays in the laboratory of the Clinical Neurocardiology Section in intramural NINDS, under the Catecholamine Resource Initiative.

Catechol assays were done according to methodology previously developed and published by our group (Holmes et al. 1994, 2010). Briefly, frozen tissue samples were homogenized in a mixture of 20 : 80 of 0.2 M phosphoric : 0.2 M acetic acid and the supernate transferred to plastic cryotubes and stored at −80 degrees centigrade until assayed by batch alumina extraction followed by liquid chromatography with series electrochemical detection.

DOPAL standard was synthesized in the laboratory and provided by Dr Kenneth L. Kirk (NIDDK). Identification of the DOPAL standard was confirmed by mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance, and liquid chromatography with time-of-flight mass spectrometry.

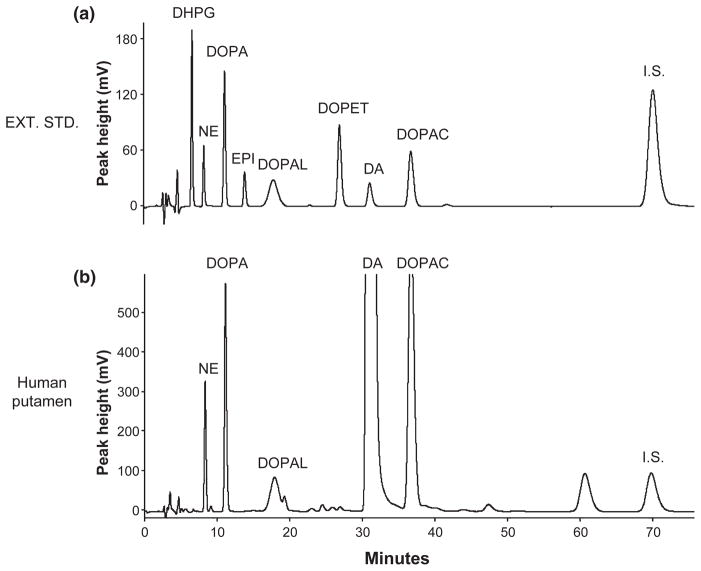

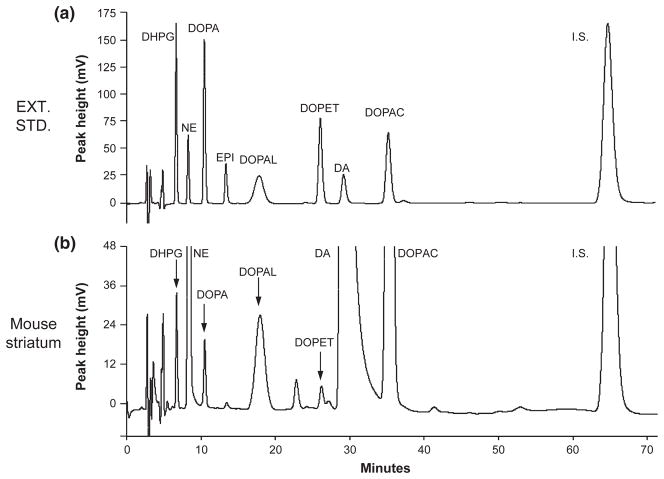

Until now, it has been thought that concentrations of DOPA in mouse striatum are below the limit of detection of HPLC-electrochemical methodology, without incubating the tissue in an inhibitor of L-aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase. Several factors are necessary to assay striatal tissue DOPA successfully (Figs 2 and 3) without decarboxylase inhibition. These include: (i) use of HPLC-electrochemical systems that are dedicated for catechols only, (ii) Type I water (18 meg-ohm resistance) and the purest HPLC grade reagents, (iii) carefully chosen and conditioned columns, (iv) filtering and degassing the mobile phase to ensure there are no particles or air bubbles, (v) alumina extraction to purify the catechols, (vi) post-column electrochemical detection with a series of flow-through electrodes (so that only reversibly oxidized species are detected), (vii) a policy of not assaying experimental samples until or unless chromatographs of standards and extracted standards are as clean as possible, and (viii) expert assay personnel.

Fig. 2.

Chromatographs of extracted catechol standards and catechols in putamen tissue from a control subject. (a) Chromatograph after injection of alumina eluate from 1000 pg of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol, 250 pg norepinephrine, 1000 pg DOPA, 250 pg epinephrine (EPI), 1000 pg 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol, 250 pg dopamine, 1000 pg 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, and internal standard (I.S.); (b) Chromatograph after injection of alumina eluate from a sample of putamen tissue homogenate of a control subject.

Fig. 3.

Chromatographs of extracted catechol standards and catechols in striatum tissue from a control mouse. (a) Chromatograph after injection of alumina eluate from 1000 pg of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol, 250 pg norepinephrine, 1000 pg DOPA, 250 pg epinephrine (EPI), 1000 pg 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol, 250 pg dopamine, 1000 pg 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, and internal standard (I.S.); (b) Chromatograph after injection of alumina eluate from a sample of striatum tissue homogenate of a control mouse.

Catechol concentrations in cell lysates were expressed in units of pmoles per mg wet weight.

Data analysis and statistics

Neurochemical data were graphed using KaleidaGraph 4.01 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA, USA). Differences between PD patients and their controls, VMAT2-Lo mice and their controls, and ALDH1A1,2 mice and their controls were assessed by two-tailed, independent-means t-tests conducted upon log-transformed data. As log-transformed data were used, all data with zero values were excluded. Mean values were expressed ± SEM. A p-value of less than 0.05 defined statistical significance.

Results

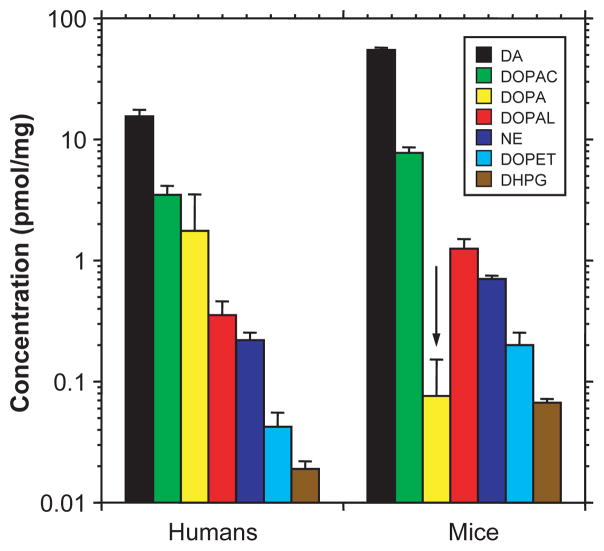

In both human putamen and murine striatum, tissue concentrations of catechols varied by about 1000-fold. Concentrations of catecholamines and deaminated metabolites were higher in mice than in humans (Fig. 4), whereas DOPA was starkly lower in mice.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of human putamen with mouse striatal tissue concentrations of catechols. Control mouse data were for the ALDH1A1,2 knockouts (n = 54). Note that mice have higher striatal mean concentrations of catecholamines and deaminated metabolites but a lower mean concentration of DOPA than found in human putamen.

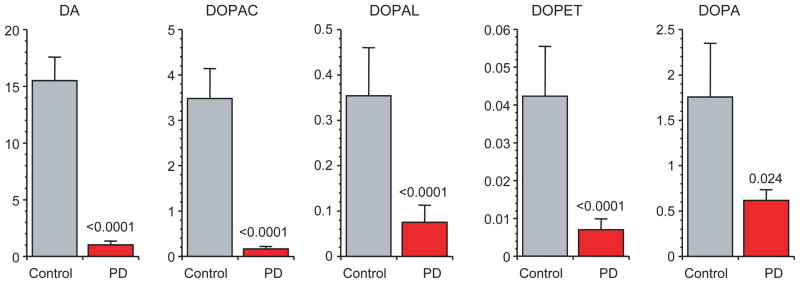

As expected, putamen tissue concentrations of DA and DOPAC were decreased drastically in PD patients compared to controls, by 94% each (p < 0.0001; Fig. 5a and b). From inspection of the histograms in Fig. 5, the red bars (PD patients) were very small with respect to the gray bars (controls). DOPAL and DOPET were also decreased (p < 0.0001 each) in PD, but to lesser proportionate extents (79 and 83%) than were DA and DOPAC (Table 1). DOPA was decreased in PD (p = 0.02) by 65%.

Fig. 5.

Putamen mean (± SEM) concentrations (pmol/mg wet weight) of catechols in post-mortem putamen from patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD, red) and controls (gray). Abbreviations: DA = dopamine; DOPAC = 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; DOPAL = 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde; DOPET = 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol; DOPA = 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine. Note severely decreased DA and DOPAC, less severely decreased DOPAL and DOPET, and even less severely decreased DOPA in PD relative to controls.

Although absolute concentrations of DOPAL were decreased in putamen from PD patients compared with controls, the PD group had about a 5-fold increase in DOPAL relative to DA (p = 0.007; Fig. 6a, Table 1).

Fig. 6.

Putamen mean (± SEM) ratios of (a) 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL): dopamine (DA), (b) DA : DOPA, and (c) 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC): DOPAL in post-mortem putamen from patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD, red) and controls (gray). PD features neurochemical evidence for decreased vesicular sequestration and decreased aldehyde dehydrogenase activity.

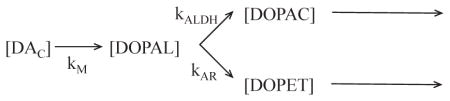

The mean DOPAC : DOPAL ratio in putamen tissue was decreased by 70% in PD compared with controls (p = 0.0006; Fig. 6c, Table 1).

Consistent with predominance of ALDH over AR in the metabolic fate of endogenous DOPAL, in control subjects the mean ratio of DOPAC : DOPAL (11.3 ± 2.5) exceeded by far the ratio of DOPET : DOPAL (0.12 ± 0.03; p < 0.0001 by dependent-means t-test). In PD putamen, the mean ratio of DOPET : DOPAC, reflecting the relative contributions of AR versus ALDH in the fate of cytosolic DOPAL, was increased to about 10 times control (0.122 ± 0.062 vs. 0.012 ± 0.002, p = 0.01).

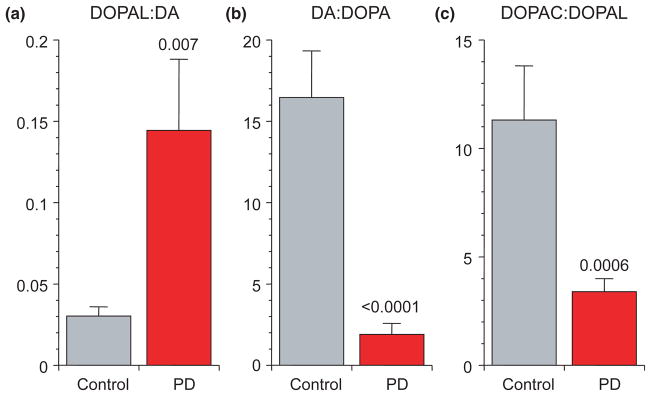

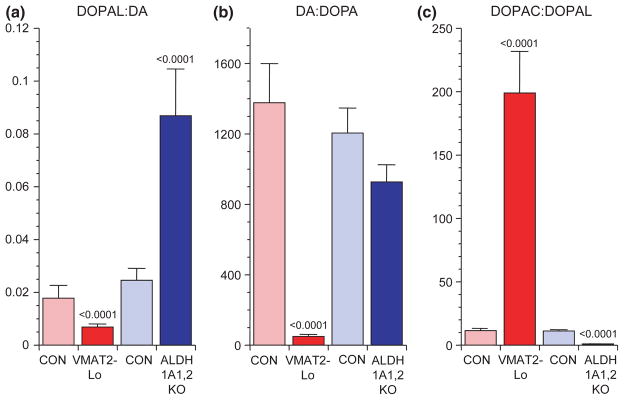

The mean ratio of DA : DOPA in striatum was markedly decreased in VMAT2-Lo mice compared with control mice (p < 0.0001; Table 2 and Fig. 7b). Meanwhile, the mean DOPAC : DOPAL ratio was markedly increased and DO-PET : DOPAC ratio decreased. VMAT2-Lo mice also had low striatal norepinephrine (NE) and dihydroxyphenylglycol (DHPG) and decreased NE : DHPG ratios (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean (± SEM) striatal tissue concentrations and ratios of catechols in mice with very low activity of the type 2 vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2-Lo) or knockouts of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 and 2 genes (ALDH1A1,2)

| Catechol | VMAT2 Control | VMAT2-Lo | ALDH1A1,2 Control | ALDH1A1,2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| (21) | (7) | (54) | (34) | |

| DOPA | 0.046 ± 0.012 | 0.078 ± 0.016 | 0.076 ± 0.008 | 0.081 ± 0.009 |

| DA | 37.6 ± 2.10 | 3.02 ± 0.41**** | 55.0 ± 2.41 | 54.0 ± 2.81 |

| DOPAL | 0.57 ± 0.13 | 0.02 ± 0.00**** | 1.25 ± 0.25 | 4.16 ± 0.55**** |

| DOPAC | 3.29 ± 0.22 | 3.30 ± 0.26 | 7.75 ± 0.88 | 3.16 ± 0.26**** |

| DOPET | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 1.21 ± 0.26**** |

| NE | 2.37 ± 0.20 | 0.63 ± 0.05**** | 0.70 ± 0.05 | 0.70 ± 0.06 |

| DHPG | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01*** | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| DOPAL : DA | 0.018 ± 0.005 | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 0.025 ± 0.005 | 0.087 ± 0.018*** |

| DA : DOPA | 1377 ± 223 | 49.7 ± 11.5**** | 1205 ± 143 | 926 ± 98 |

| DOPAC : DOPAL | 11.4 ± 1.91 | 199 ± 32.8**** | 11.2 ± 1.04 | 0.97 ± 0.10**** |

| DOPET : DOPAC | 0.012 ± 0.0007 | 0.005 ± 0.0004**** | 0.018 ± 0.002 | 0.306 ± 0.035**** |

| NE : DHPG | 29.3 ± 1.60 | 15.8 ± 1.87** | 11.5 ± 0.60 | 12.1 ± 0.82 |

Different from control,

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001;

p < 0.0001.

Tissue concentrations are in pmol/mg wet weight.

Numbers of animals are in parentheses.

Fig. 7.

Striatal mean (± SEM) ratios of (a) 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL): dopamine (DA), (b) DA : DOPA, and (c) 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) : DOPAL in mice with very low activity of the type 2 vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2-Lo, red) and mice with double knockout of the ALDH1A1 and ALDH2 genes (ALDH1A1,2 KO, blue). Light colors represent the corresponding control groups. The results show that low VMAT2 activity decreases DOPAL : DA and DA : DOPA and increases DOPAC : DOPAL, whereas low aldehyde dehydrogenase activity increases DOPAL : DA, does not affect DA : DOPA, and decreases DOPAC : DOPAL.

ALDH1A1,2 KO mice had increased DOPAL, DOPET, DOPAL : DA, and DOPET : DOPAC and decreased DOPAC and DOPAC : DOPAL compared to control mice (p < 0.0001 each; Fig. 7c, Table 2).

Inspection of the results in Tables 2 and 3 shows that with the exception of tissue DOPA, the two mouse strains differed completely in terms of the pattern of changes in the dependent neurochemical measures.

Table 3.

Overview of Results about Tissue Catechols in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease (PD), Mice with Very Low Activity of the Type 2 Vesicular Monoamine Transporter (VMAT2-Lo), and Mice with Knockouts of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1A1 and 2 Genes (ALDH1A1,2)

| Catechol | PD | VMAT2-Lo | ALDH1A1, 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOPAL : DA | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

| DA : DOPA | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↔ |

| DOPAC : DOPAL | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓↓ |

| DOPAC : DA | ↔ | ↑↑ | ↓ |

| DOPET : DOPAC | ↑↑ | ↓ | ↑↑ |

↑ Increased compared with controls.

↑↑↑ Markedly increased compared with controls (more than 5-fold).

↓ Decreased compared with controls.

↓↓ Markedly decreased compared with controls (less than 20%).

↔ Not significantly different from controls.

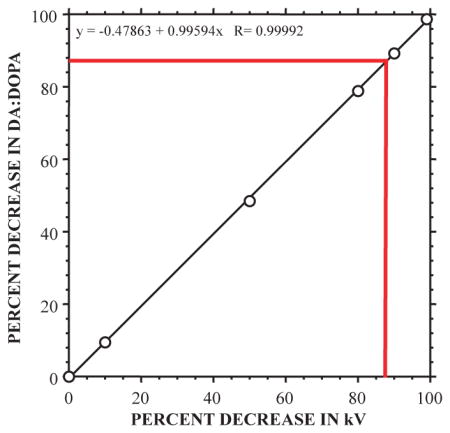

Applying the kinetic model and rate constants in the Appendix (Gjedde et al. 1991; Goldstein et al. 2002; Eisenhofer et al. 1996; Bonifacio et al. 2002), vesicular uptake was estimated to be decreased by 89% and ALDH activity decreased by 70% in PD putamen.

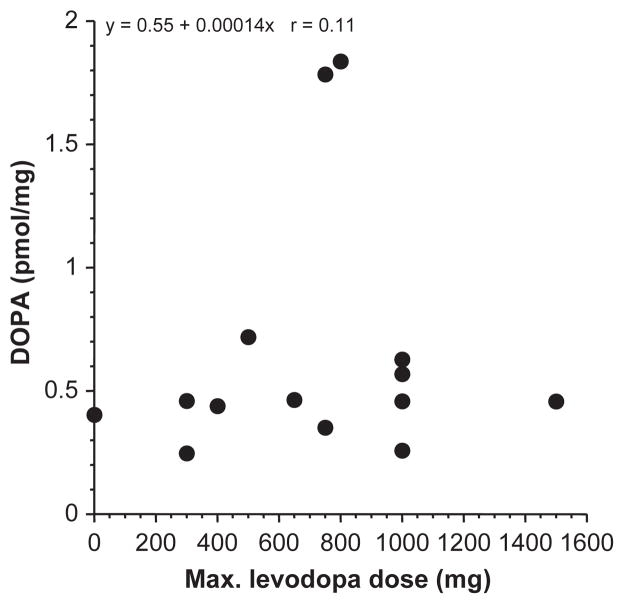

Among the PD patients, individual values for DOPAL : DA, DA : DOPA, and DOPAC : DOPAL ratios were unrelated to tissue DOPA content (r = 0.23, n = 14; r = 0.13, n = 17; r = 0.12, n = 14). DOPA content was also unrelated to the maximum levodopa dose prior to death (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Putamen tissue DOPA content expressed as a function of the maximum levodopa dose prior to death in Parkinson’s disease patients. Tissue DOPA content was unrelated to the maximum levodopa dose prior to death, with or without exclusion of two outliers who had relatively high tissue DOPA levels.

Discussion

The major advance of this study is the derivation, validation, and application of a conceptual approach that helps explain why DOPAL is built up in the putamen in PD. As noted previously (Goldstein et al. 2011), DOPAL was increased by about 5-fold relative to DA. From the kinetic model in the Appendix, tissue DA : DOPA was used to indicate vesicular uptake and DOPAC : DOPAL ALDH activity. Data from mouse genetic models validated these indices. Applying the rate constants listed in the Appendix, we estimated that vesicular uptake was decreased by 89% in PD putamen. PD patients have about a 90% decrease in VMAT2 protein in putamen (Miller et al. 1999; Tong et al. 2011), and results of neuroimaging studies using positron-emitting analogs of tetrabenazine, a VMAT2 ligand, also indicate severely decreased vesicular sequestration in PD (Raffel et al. 2006; Okamura et al. 2010; Bohnen et al. 2006). Based on previously published data (DelleDonne et al. 2008), in PD patients immunoreactive tyrosine hydroxylase in the striatum is decreased by 65% compared with controls, whereas immunoreactive VMAT2 is decreased by 96%. The difference reflects decreased vesicular uptake in the residual terminals. The previously reported data lead to the inference that vesicular uptake is decreased by 88% in PD. This value agrees remarkably with the value of 89% based on the DA : DOPA ratios in this study.

From DOPAC : DOPAL ratios we obtained evidence also for a 70% decrease in ALDH activity in PD putamen. Postmortem substantia nigra from PD patients contains decreased gene expression and protein levels of ALDH1A1 (Mandel et al. 2005; Galter et al. 2003; Werner et al. 2008), but this could be a result rather than cause of loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons. Recently, it has been reported that blood of PD patients contains decreased gene expression for ALDH1A1 (Molochnikov et al. 2012; Grunblatt et al. 2010), supporting a pathogenetic role of decreased ALDH activity in PD. Low cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of DOPAC for given concentrations of DA (Goldstein et al. 2012a) are also consistent with decreased ALDH activity; however, this is a quite indirect measure of conversion of DOPAL to DOPAC. DOPAL itself is not detected reliably in human cerebrospinal fluid (Goldstein et al. 2012a).

PD patients had an increased ratio of DOPET : DOPAC in putamen tissue, consistent with a shift from ALDH to AR as an alternative means to detoxify DOPAL. The increased DOPAL concentration relative to DA suggests that such compensation is inadequate to prevent DOPAL buildup. Analogously, ALDH knockout mice had increased striatal DOPET : DOPAC ratios but markedly increased striatal DOPAL levels. These findings indicate that AR is relatively inefficient in DOPAL detoxification.

VMAT2-Lo mice had low DA : DOPAC ratios, explicable by increased oxidative deamination of cytosolic DA because of virtual absence of vesicular uptake. This explanation predicts elevated DOPAL and normal DOPAC : DOPAL, whereas DOPAL was low and DOPAC : DOPAL high. DOPAC : DOPAL in the VMAT2-Lo mice averaged about 200 times that in ALDH1A1,2 KO mice. From the kinetic model, VMAT2-Lo mice seem to have markedly increased ALDH activity. Incomplete compensation for increased DOPAL generation in VMAT-Lo mice or for decreased DOPAL detoxification in ALDH knockout mice may help explain why both strains develop aging-related neuropathologic and neurobehavioral abnormalities reminiscent of those in PD (Wey et al. 2012; Caudle et al. 2007).

Both the VMAT2 and ALDH mouse strains have been reported to show evidence of nigrostriatal neuron loss (Caudle et al. 2007; Wey et al. 2012); however, the magnitudes of these decreases do not come close to the magnitude of loss of putamen DA depletion seen in PD patients. Table 3 highlights similarities and differences among the PD, VMAT2-Lo, and ALDH1A1,2 groups. One gains the impression that neither mouse model reproduces the pattern of neurochemical abnormalities found in PD. Decreased DA, NE, DA : DOPA, and NE : DHPG fit with catecholamine depletion and a shift from vesicular uptake to oxidative deamination of cytosolic catecholamines, as in VMAT2-Lo mice, and decreased DOPAC : DOPAL and increased DOPET : DOPAC fit with decreased ALDH activity, as in ALDH1A1,2 mice. We speculate that in the setting of low VMAT2 activity, compensatorily increased ALDH activity protects dopaminergic neurons, and in the setting of low ALDH activity, an ongoing high rate of vesicular uptake protects those neurons. If so, then VMAT2-Lo mice should be susceptible to DA neuron death if treated with a drug that inhibits ALDH, and ALDH knockout mice should be susceptible to a drug that inhibits vesicular uptake.

Any of a variety of factors interfering with vesicular sequestration of cytosolic DA or with detoxification of DOPAL could lead to DOPAL buildup and thereby to loss of dopaminergic terminals (Panneton et al. 2010; Burke et al. 2008). As decreased vesicular uptake increases neuronal vulnerability to exogenous factors such as rotenone (Sai et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2005), amphetamines (Wang et al. 1997; Guillot et al. 2008), MPTP (Gainetdinov et al. 1998; Staal and Sonsalla 2000), and alpha-synuclein (Ulusoy et al. 2012), vesicular sequestration seems to play a key role in detoxifying compounds taken up into monoaminergic neurons (Guillot and Miller 2009). Meanwhile, lipid peroxidation products such as 4-hydroxynonenal potently inhibit ALDH (Rees et al. 2007), and nigral neurons from PD patients contain increased levels of this aldehyde (Yoritaka et al. 1996). Moreover, the insecticide benomyl recently has been shown to decrease ALDH and exert toxicity at dopaminergic neurons (Fitzmaurice et al. 2012). Finally, DOPAL potently oligomerizes and promotes precipitation of alpha-synuclein (Burke et al. 2008), which could set the stage for multiple pathogenic positive feedback loops.

Catecholaminergic neurons are rare in the nervous system, and the basis for relatively selective loss of striatal DA terminals in PD has been mysterious. The catecholaldehyde hypothesis provides a straightforward explanation. DOPAL formation is related directly to the leakage rate of DA from vesicular stores and therefore to the size of the stored pool. As one would expect from the striatum having the highest DA concentrations in the brain, DOPAL levels are also highest in the striatum (unpublished observations). Therefore, factors decreasing vesicular sequestration of cytosolic DA and decreasing detoxification of cytosolic DOPAL would be expected to be manifested by striatal dopaminergic denervation.

The results about DOPA, catecholamines, and deaminated metabolites demonstrate large species differences between humans and mice. Much lower striatal DOPA in mice than humans might be explained by more efficient conversion of DOPA to dopamine via L-aromatic-amino-acid decarboxylase, a pool of DOPA outside catecholaminergic neurons in human striatum, or greater efficiency of vesicular sequestration of cytosolic catecholamines in mice than in humans.

One might propose that a shift from vesicular sequestration to enzymatic deamination reflects a secondary response to loss of DA neurons, because of compensatorily increased release of DA or increased turnover of DA in the surviving neurons. From the kinetic model, compensatorily increased DA release from residual terminals, with or without reuptake of the released DA, cannot explain the elevated DOPAL : DA ratios found in PD. For instance, neither a 5-fold increase in DA release nor a 5-fold increase in DA release combined with a concurrent 80% decrease in reuptake would affect DOPAL : DA appreciably. Also, neither alteration can explain the decreased DOPAC : DOPAL ratios found in PD putamen.

Whether increased putamen DOPAL levels in PD cause or contribute to loss of DA terminals cannot be determined from this study. First, association cannot prove causation, and buildup of DOPAL with respect to DA does not imply that the buildup exerts cytotoxic effects. Second, post-mortem neurochemistry cannot provide information about a putative pathogenetic sequence during life. Third, as oxidative deamination of DA to form DOPAL necessarily entails hydrogen peroxide generation, it is impossible to separate these two potential contributors to toxicity. Nevertheless, in this study, ALDH knockout mice had about the same proportionate increase in striatal DOPAL as observed in PD putamen, and ALDH knockout mice develop aging-related neuropathologic and neurobehavioral manifestations resembling those in PD (Wey et al. 2012). In PC12 cells, combined inhibition of vesicular uptake and of DOPAL metabolism increases endogenous DOPAL by about the same extent as observed in PD putamen, and interference with DOPAL metabolism contributes to DA-induced apoptosis (Goldstein et al. 2012b).

An important issue is whether levodopa treatment before death in PD patients might have influenced the obtained results. We think such an influence was unlikely. First, tissue DOPA was unrelated to the maximum levodopa dose prior to death. Second, if tissue DOPA had been increased artifactually because of treatment, then based on the known fate of DOPA in dopaminergic terminals, this theoretically would have exerted little or no effect on values for the key dependent measures of the study – ratios of DOPAL : DA, DA : DOPA, and DOPAC : DOPAL. In confirmation of this view, among PD patients individual values for all these dependent measures were unrelated to tissue DOPA content. Third, to estimate the magnitude of the effect of ongoing levodopa treatment on putamen DOPA levels, we reviewed putamen DOPA data from four patients with end-stage Parkinsonism or autopsy-proven PD in whom the patients had either never received levodopa treatment or in whom levodopa treatment had been discontinued at least 5 days prior to death. Among these patients, putamen tissue DOPA averaged 0.77 pmol/mg, a value similar to that for the PD group reported here. From this analysis we estimate that the impact of levodopa treatment on absolute levels of putamen DOPA, if any, was small.

The catecholaldehyde hypothesis yields readily testable predictions related to pathogenetic mechanisms and experimental therapeutics. In VMAT2-Lo mice exposure to drugs that inhibit ALDH and in ALDH1A1,2 knockout mice exposure to drugs that inhibit vesicular uptake would be expected to accelerate loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. Studies about effects of treatments that attenuate catecholaldehyde production, mitigate catecholaldehyde auto-oxidation, or interfere with catecholaldehyde-mediated protein cross-linking in these mouse models could provide further mechanistic and therapeutic insights.

In summary, in this study we obtained evidence that elevated DOPAL levels in PD putamen reflect markedly decreased vesicular uptake, as indicated by the ratio of DA : DOPA, and decreased DOPAL detoxification, as indicated the ratio of DOPAC : DOPAL. From the results we propose that strategies increasing the efficiency of vesicular sequestration or of catecholaldehyde detoxification, decreasing neuronal monoamine oxidase activity, or interfering with DOPAL-induced oligomerization of alpha-synuclein may prove useful in treatment or prevention.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was supported by the intramural research program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. We thank Margaret Basile and Margaret Wey for numerous tissue samples, neurochemical data from which were important for the present report.

Abbreviations used

- ALDH

aldehyde dehydrogenase

- DA

dopamine

- DHPG

3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol

- DOPAC

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid

- DOPAL

3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde

- DOPET

3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol

- NE

norepinephrine

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- VMAT

vesicular monoamine transporter

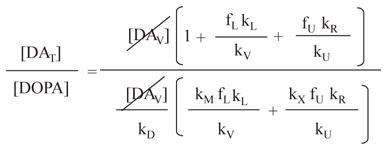

Appendix

A is an index of vesicular uptake

Where [DOPA] = Tissue DOPA concentration; [DAC] = Cytosolic DA concentration; [DAV] = Vesicular DA concentration; [DAS] = ECF DA concentration; [DOPAL] = Tissue DOPAL concentration; [DOPET] = Tissue DOPET concentration; [DOPAC] = Tissue DOPAC concentration

kD = Rate constant for cytosolic DA synthesis from DOPA

kV = Rate constant for uptake of cytosolic DA into vesicles

kM = Rate constant for monoamine oxidase

kL = Rate constant for leak of vesicular DA into the cytosol

kU = Rate constant for neuronal uptake of DA

kR = Rate constant for exocytotic release of DA into the ECF

kX = Rate constant for loss of DA from the ECF, e.g., by COMT

If

kD = 0.032 min−1 Gjedde et al. 1991

kV = 3.44 min−1 Goldstein et al. 2002 (2 X kV for 18F-DA)

kM = 0.82 min−1 Kopin & Sullivan test tube Vmax/kM

kL = 0.0063 min−1 To fit actual DA:DOPA

kU = 1.10 min−1 Goldstein et al. 2002 (2 X kU for 18F-DA)

kR = 0.0016 min−1 Eisenhofer et al. 1996 (2636/10330) kL)

kX = 0.08 min−1 Bonifacio et al. 2002 (Vmax/kM)

Then

The assigned values for rate constants are reasonable, since actual .

is sensitive to kV with y = −0.47863 + 0.99594x R= 0.99992.

For the observed decrease of 88.5% in , the estimated decrease in vesicular uptake is 89%.

B is an index of ALDH activity

Since kALDH ≫ kAR,

Where kX-DOPAC = rate constant for loss of [DOPAC].

Therefore, is directly related to kALDH.

Footnotes

The Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Anderson DG, Mariappan SV, Buettner GR, Doorn JA. Oxidation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopaminergic metabolite, to a semiquinone radical and an orthoquinone. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:26978–26986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.249532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnen NI, Albin RL, Koeppe RA, Wernette KA, Kilbourn MR, Minoshima S, Frey KA. Positron emission tomography of monoaminergic vesicular binding in aging and Parkinson disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1198–1212. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifacio MJ, Archer M, Rodrigues ML, Matias PM, Learmonth DA, Carrondo MA, Soares-Da-Silva P. Kinetics and crystal structure of catechol-o-methyltransferase complex with co-substrate and a novel inhibitor with potential therapeutic application. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:795–805. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, Li SW, Williams EA, Nonneman R, Zahm DS. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde is the toxic dopamine metabolite in vivo: implications for Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Brain Res. 2003;989:205–213. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, Li SW, Chung HD, et al. Neurotoxicity of MAO metabolites of catecholamine neurotransmitters: role in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurotoxicology. 2004;25:101–115. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ, Kumar VB, Pandey N, et al. Aggregation of alpha-synuclein by DOPAL, the monoamine oxidase metabolite of dopamine. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudle WM, Richardson JR, Wang MZ, et al. Reduced vesicular storage of dopamine causes progressive nigrostriatal neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8138–8148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0319-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelleDonne A, Klos KJ, Fujishiro H, et al. Incidental Lewy body disease and preclinical Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1074–1080. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duester G. Genetic dissection of retinoid dehydrogenases. Chem Biol Interact. 2001;130–132:469–480. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer H, Hornykiewicz O. Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1960;38:1236–1239. doi: 10.1007/BF01485901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer G, Friberg P, Rundqvist B, Quyyumi AA, Lambert G, Kaye DM, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS, Esler MD. Cardiac sympathetic nerve function in congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1996;93:1667–1676. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.9.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhofer G, Kopin IJ, Goldstein DS. Catecholamine metabolism: a contemporary view with implications for physiology and medicine. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:331–349. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice AG, Rhodes SL, Lulla A, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibition as a pathogenic mechanism in Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;110:636–641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220399110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov RR, Fumagalli F, Wang YM, Jones SR, Levey AI, Miller GW, Caron MG. Increased MPTP neurotoxicity in vesicular monoamine transporter 2 heterozygote knockout mice. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1973–1978. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70051973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galter D, Buervenich S, Carmine A, Anvret M, Olson L. ALDH1 mRNA: presence in human dopamine neurons and decreases in substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease and in the ventral tegmental area in schizophrenia. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A, Reith J, Dyve S, Leger G, Guttman M, Diksic M, Evans A, Kuwabara H. Dopa decarboxylase activity of the living human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2721–2725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DS. Stress, allostatic load, catecholamines, and other neurotransmitters in neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2012;32:661–666. doi: 10.1007/s10571-011-9780-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DS, Katzper M, Linares OA, Kopin IJ. Kinetic model for the fate of the sympathoneural imaging agent 6-[18F]-fluorodopamine in the human heart: a novel means to assess cardiac sympathetic neuronal function. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2002;365:38–49. doi: 10.1007/s002100100426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DS, Sullivan P, Holmes C, Kopin IJ, Basile MJ, Mash DC. Catechols in post-mortem brain of patients with Parkinson disease. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:703–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DS, Holmes C, Sharabi Y. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of central catecholamine deficiency in Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies. Brain. 2012a;135:1900–1913. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DS, Sullivan P, Cooney A, Jinsmaa Y, Sullivan R, Gross DJ, Holmes C, Kopin IJ, Sharabi Y. Vesicular uptake blockade generates the toxic dopamine metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde in PC12 Cells: relevance to the pathogenesis of Parkinson disease. J Neurochem. 2012b;123:932–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunblatt E, Zehetmayer S, Jacob CP, Muller T, Jost WH, Riederer P. Pilot study: peripheral biomarkers for diagnosing sporadic Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2010;117:1387–1393. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot TS, Miller GW. Protective actions of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) in monoaminergic neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 2009;39:149–170. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8059-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot TS, Shepherd KR, Richardson JR, Wang MZ, Li Y, Emson PC, Miller GW. Reduced vesicular storage of dopamine exacerbates methamphetamine-induced neurodegeneration and astrogliosis. J Neurochem. 2008;106:2205–2217. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05568.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS. Improved assay for plasma dihydroxyphenylacetic acid and other catechols using high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1994;653:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(93)e0430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Whittaker N, Heredia-Moya J, Goldstein DS. Contamination of the norepinephrine prodrug droxidopa by dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde. Clin Chem. 2010;56:832–838. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.139709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornykiewicz O. Biochemical aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51:S2–S9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2_suppl_2.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SW, Lin TS, Minteer S, Burke WJ. 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde and hydrogen peroxide generate a hydroxyl radical: possible role in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;93:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HQ, Zhu XZ, Weng EQ. Intracellular dopamine oxidation mediates rotenone-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel S, Grunblatt E, Riederer P, Amariglio N, Jacob-Hirsch J, Rechavi G, Youdim MB. Gene expression profiling of sporadic Parkinson’s disease substantia nigra pars compacta reveals impairment of ubiquitin-proteasome subunits, SKP1A, aldehyde dehydrogenase, and chaperone HSC-70. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1053:356–375. doi: 10.1196/annals.1344.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchitti SA, Deitrich RA, Vasiliou V. Neurotoxicity and metabolism of the catecholamine-derived 3,4-dihydroxyphenyla-cetaldehyde and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycolaldehyde: the role of aldehyde dehydrogenase. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:125–150. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattammal MB, Haring JH, Chung HD, Raghu G, Strong R. An endogenous dopaminergic neurotoxin: implication for Parkinson’s disease. Neurodegeneration. 1995;4:271–281. doi: 10.1016/1055-8330(95)90016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GW, Erickson JD, Perez JT, Penland SN, Mash DC, Rye DB, Levey AI. Immunochemical analysis of vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2) protein in Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1999;156:138–148. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.7008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GW, Wang YM, Gainetdinov RR, Caron MG. Dopamine transporter and vesicular monoamine transporter knockout mice: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Methods Mol Med. 2001;62:179–190. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-142-6:179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molochnikov L, Rabey JM, Dobronevsky E, et al. A molecular signature in blood identifies early Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:26. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N, Villemagne VL, Drago J, et al. In vivo measurement of vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 density in Parkinson disease with (18)F-AV-133. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:223–228. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panneton WM, Kumar VB, Gan Q, Burke WJ, Galvin JE. The neurotoxicity of DOPAL: behavioral and stereological evidence for its role in Parkinson disease pathogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, et al. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffel DM, Koeppe RA, Little R, Wang CN, Liu S, Junck L, Heumann M, Gilman S. PET measurement of cardiac and nigrostriatal denervation in parkinsonian syndromes. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1769–1777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees JN, Florang VR, Anderson DG, Doorn JA. Lipid peroxidation products inhibit dopamine catabolism yielding aberrant levels of a reactive intermediate. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:1536–1542. doi: 10.1021/tx700248y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees JN, Florang VR, Eckert LL, Doorn JA. Protein reactivity of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopamine metabolite, is dependent on both the aldehyde and the catechol. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22:1256–1263. doi: 10.1021/tx9000557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sai Y, Wu Q, Le W, Ye F, Li Y, Dong Z. Rotenone-induced PC12 cell toxicity is caused by oxidative stress resulting from altered dopamine metabolism. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008;22:1461–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satake W, Nakabayashi Y, Mizuta I, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants at four loci as genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/ng.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, et al. alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2003;302:841. doi: 10.1126/science.1090278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staal RG, Sonsalla PK. Inhibition of brain vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT2) enhances 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium neurotoxicity in vivo in rat striata. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:336–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor TN, Caudle WM, Shepherd KR, Noorian A, Jackson CR, Iuvone PM, Weinshenker D, Greene JG, Miller GW. Nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease revealed in an animal model with reduced monoamine storage capacity. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8103–8113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1495-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong J, Boileau I, Furukawa Y, Chang LJ, Wilson AA, Houle S, Kish SJ. Distribution of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 protein in human brain: implications for brain imaging studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:2065–2075. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulusoy A, Bjorklund T, Buck K, Kirik D. Dysregulated dopamine storage increases the vulnerability to alpha-synuclein in nigral neurons. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;47:367–377. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YM, Gainetdinov RR, Fumagalli F, Xu F, Jones SR, Bock CB, Miller GW, Wightman RM, Caron MG. Knockout of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 gene results in neonatal death and supersensitivity to cocaine and amphetamine. Neuron. 1997;19:1285–1296. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner CJ, Heyny-von Haussen R, Mall G, Wolf S. Proteome analysis of human substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Proteome Sci. 2008;6:8. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-6-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wey M, Fernandez E, Martinez PA, Sullivan P, Goldstein DS, Strong R. Neurodegeneration and motor dysfunction in mice lacking cytosolic and mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenases: implications for Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoritaka A, Hattori N, Uchida K, Tanaka M, Stadtman ER, Mizuno Y. Immunohistochemical detection of 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts in Parkinson disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2696–2701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]