Abstract

Fasciola hepatica NP-40 released antigens (FhTeg) exhibit potent Th1 immunosuppressive properties in vitro and in vivo. However, the protein composition of this active fraction, responsible for Th1 immune modulatory activity, has yet to be resolved. Therefore, FhTeg, a Nonidet P-40 extract, was subjected to a proteomic analysis in order to identify individual protein components. This was performed using an in house F. hepatica EST database following 2D electrophoresis combined with de novo sequencing based mass spectrometry. The identified proteins, a mixture of excretory/secretory and membrane-associated proteins, are associated with stress response and chaperoning, energy metabolism and cytoskeletal components. The immune modulatory properties of these identified protein(s) is discussed and HSP70 from F. hepatica is highlighted as a potential host immune modulator for future study.

Keywords: Anti-Inflammatory, Heat Shock Protein, Proteomics

1. Introduction

Fascioliasis, caused by the liver flukes Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica, results in annual losses of more than US$3 billion to livestock production worldwide through livestock mortality and by decreased productivity via reduction of milk, wool and meat yields (Boray, 1997). Within the host, Fasciola sp. have been shown to influence the host inflammatory responses to prolong its survival (Hamilton et al., 2009). For example, F. hepatica can suppress antigen-specific Th1 responses in concurrent bacterial infections (Brady et al., 1999; O’Neill et al., 2000), which suggests that proteins from the parasite may have novel immune-modulatory applications. More recently, we have shown that a F. hepatica Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) extracted fraction (FhTeg), potentially containing excretory/secretory (ES) and membrane-associated proteins, exhibits a Th1 suppressive effect in vivo in mouse models of septic shock. Given the central role of dendritic cells (DC) in developing these inflammatory responses we previously investigated the effect that FhTeg has on DC maturation processes and found FhTeg-activated DCs are hypo-responsive to Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation, characterised by significantly suppressed cytokine production and co-stimulatory molecule expression. FhTeg also impaired DC function by inhibiting their capacity to phagocytose and reducing their ability to prime T cells (Hamilton et al., 2009). In light of these recent findings, it remains paramount to resolve the protein complement of FhTeg preparations in order to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms of this novel immune modulation. Therefore, the focus of this paper is to resolve, via proteomics, the excreted and/or secreted mobile protein components from the novel immune modulating Nonidet P-40 extracted fraction designated FhTeg.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. FhTeg Preparation

FhTeg was prepared as previously described (Hamilton et al., 2009). Briefly, F. hepatica adult worms were washed in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated in 1% NP-40 (Sigma-Aldrich, U.K.) in PBS for 30 min, and supernatant was collected. NP-40 was removed using Extracti-Gel D detergent-removing gel (Pierce, U.K.), and the remaining supernatant was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C prior to being filtered/concentrated using compressed air, and then stored at −20°C. This was followed by an additional centrifugation at 21,000 × g and 4°C for 15 mins prior to protein precipitation. The supernatant post centrifugation was precipitated using 10 % w/v Trichloroacetic acid in ice cold acetone for 1 h at −20°C. Precipitated protein pellets were washed in ice cold acetone 3 times and air dried at −20°C for 15 mins. The resulting pellets were re-sloubilised in buffer containing 8 M urea, 2 % CHAPS w/v, 33 mM DTT, 0.5 % carrier ampholytes (pH 3 - 10) v/v and protease inhibitors (CompleteMini, Roche, U.K.).

2.2. 2DE and Image Analysis

A total of 300 μl of FhTeg (containing 150 μg of protein) was used to actively rehydrate and focus a 17 cm linear pH 3-10 IPG strip (Biorad, U.K.) at 20°C for separation in the first dimension. Immobilised Ph gradient (IPG) strips were focussed between 40,000 and 60,000 Vh using the Ettan IPGphor system (Amersham Biosciences, U.K.). IPG strips were equilibrated as previously described in Morphew et al. (2007). The IPG strips were separated in the second dimension on the Protean II system (Biorad, U.K.) using 14 % polyacrylamide gels as previously described in Morphew et al. (2011; 2007).

Gels were Coomassie blue stained (PhastGel Blue R, Amersham Biosciences, U.K.) and imaged with a GS-800 calibrated densitometer (Biorad, U.K.) set for coomassie stained gels at 400 dpi. Imaged 2-DE gels were analysed using Progenesis PG220 v.2006. Analysis was performed using the Progenesis ‘Mode of non-spot’ background subtraction method. Normalised spot volumes were calculated using the Progenesis ‘Total spot volume multiplied by total area’ method (Morphew et al., 2011; 2007) and were used to determine the most abundant protein spots in FhTeg. Protein spot percentage contributions were calculated using the normalised spot volumes of all proteins present on the 2DE arrays.

2.3. MSMS and Protein Identification

Protein spots of interest were excised and tryptically digested (Modified trypsin sequencing grade, Roche, U.K.) as previously described (Morphew et al., 2011; 2007). Samples were re-suspended in 10 μl of 1 % v/v formic acid and 0.5 % v/v acetonitrile for tandem mass spectrometry (MSMS).

Samples for MSMS were loaded into gold coated nanovials (Waters, U.K.) and sprayed at 800-900 V at atmospheric pressure using a QToF 1.5 ESI MS (Waters, U.K.). Selected peptides were isolated and fragmented by collision induced dissociation using Argon as the collision gas. Fragmentation spectra were interpreted directly using the Peptide Sequencing programme (MassLynx v 3.5, Waters. U.K.) following spectrum smoothing (2 × smooths, Savitzky Golay +/− 5 channels), background subtraction (polynomial order 15, 10 % below the curve) and processing with Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) 3 deconvolution software (All MassLynx v 3.5, Waters. U.K.). Sequence interpretation using the Peptide Sequencing programme was conducted automatically with an intensity threshold set at 1 and a fragment ion tolerance set at 0.1 Da. Carbamidomethylation of cysteines, acrylamide modified cysteines and oxidised methionines were taken into account and trypsin specified as the enzyme used to generate peptides. A minimum mass standard deviation was set at 0.025 and the sequence display threshold (% Prob) set at 1. Samples that did not show significant scores and probability when using automated sequence prediction were also interpreted manually to generate sequence tags rather than full peptide sequence information. In these circumstances, the MassLynx program Peptide sequencing was again used with the parameters described above.

Peptide sequences and sequence tags from MSMS were used separately to search the Genbank protein database (Version 182.0 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/132015054 reported sequences) using BLAST adjusted for short nearly exact matches. Consequently, all protein accession numbers reported here relate to Genbank. Only peptides with E values of less than 0.1 were used to assign an identity or a clade to a protein. In some cases peptides produce E values greater than 0.1 despite 100 % sequence matching. As stated, these peptides were not included for, but added confidence to, the identifications. All sequences that did not show 100 % sequence identity to Genbank entries were subjected to a local BLAST analysis using BioEdit Version 7.0.5.3 (10/28/05) searching an in house translated database of F. hepatica ESTs (available by anonymous FTP from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/pathogens/Fasciola/). Again, only matches with E values less than 0.1 were used to assign an identification.

Sequences identified from MSMS analysis (both from Genbank and EST database searches) were analysed for signal peptides, exportation to the mitochondria and trans-membrane domains. For signal peptides the SignalP 3.0 server was used and for predicting cleavage sequences determining export to the mitochondria MitoProt II version 1.0a4 was used. For trans-membrane (TM) domain prediction HMMTOP server version 2.0 was used. In addition, all sequences were subjected to BLAST through the Gene Ontology server AmiGO (Ashburner et al., 2000) with the top scoring hits used to assign GO terms corresponding to Biological processes, Cellular components and Molecular functions.

3. Results and Discussion

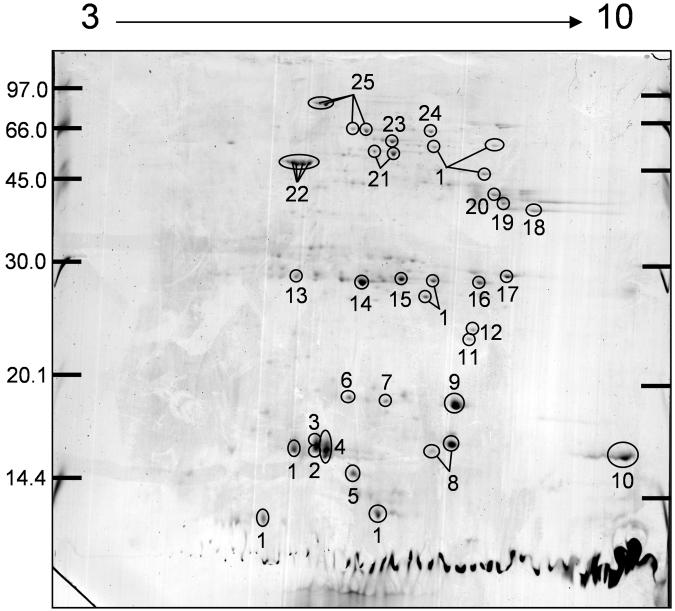

The 2DE proteomic analysis of the immune modulating FhTeg protein pool produced a detailed proteome consisting of 172 spots (Figure 1), with the majority of protein spots ranging in molecular weight from 14.4 – 97 kDa and from pH 5 – 9. The major 40 protein spots, representing over 50 % of the total FhTeg proteome, were then excised for MSMS sequence analysis, for protein identification and primary sequence analysis. This led to the identification of 32 protein spots representing 24 individual proteins from 19 protein families (Table 1). Fourteen of these protein identifications were made directly against the public databases with the remaining identifications assigned using a F. hepatica EST database followed by sequence similarity searching with the full EST sequence. In all cases, with one exception, each protein spot was identified as a single protein. The exception was spot 2 where heat responsive protein (HRP) was definitively identified and FABP type I was potentially identified as a co-migrating protein (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Whole FhTeg preparation 2DE proteomic array.

Proteins were separated across a linear pH 3-10 IPG strip and 14 % SDS-PAGE in the second dimension. The 2DE was Coomassie blue stained. All circled and numbered protein spots correspond to putative protein identifications seen in Table 1. Molecular weight markers are shown on the left.

Table 1. Identification of tegumental associated proteins from FhTeg preparations by MSMS.

Peptide sequences were used to search against Genbank or a translated EST library for the identification of each protein. Sequences derived from MSMS analysis were interpreted either, automated or manually (where manually interpreted using Masslynx version 3.5 sequences are denoted by a *). Sequenced amino acids that match exactly with those found in the Genbank database or translated EST database are underlined.

| Spot Number | Sequence | Accession Number | Identification | Species | MOTIFA) | % Contribution | ES ProductsB) | Tegument PreparationC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | - | Unidentified | Unidentified | - | - | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 2 | 1- TFWEFEEETPD* | Q7M4G0 | FABP Type I | Fasciola hepatica | - | 3.580 | W | |

| 1- NEIYGEYFSDPY* | XP_001149111 | Heat Responsive Protein 12 | Pan troglodytes | EM, TM(1) | ||||

| 2- FQVACLPK* | XP_001149111 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 3 | 1- TLTFTFGEYLEEETDPGK | Q9UAS2 | FABP Type I | F. hepatica | - | 2.570 | MRW | |

| 2- CTVGDVK* | Q9UAS2 | |||||||

| 3- TTFTFGEEFEEETPDG* | Q7M4G0 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4 | 1- TTTFTFGEEFKDETFDNR* | Q7M4G1 | FABP Type II | F. hepatica | - | 7.012 | MR | W1 |

| 2- KMVITITVGDVK* | ||||||||

| 3- WKLEHSENMDGVWK | ||||||||

| 4- DFVGSWKLEHSENMDGVWK* | ||||||||

| 5- PKPEFTFELEGNKMTIK* | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 5 | 1- PEVEFAKVDVDQNEEAAAK* | AAF14217 | Thioredoxin | F. hepatica | - | 1.407 | R | W1 |

| 2- YSVTAMPTFVFIK | ||||||||

| 3- MPTFVFIKDGK | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 6 | 1- FVQESETSPVQIK | AAD30361 | Cu/Zn Superoxide Dismutase | F. hepatica | - | 0.657 | W1 | |

| 2- AMVVHENEDDLGR | ||||||||

| 3- SMSGSSGVQGTVK* | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 7 | 1- NKLLSPLGEGSPVAK | NP_082902 | Methylmalonyl-CoA Epimerase, Mitochondrial Precursor | Mus Musculus | SP, EM | 0.599 | ||

| 2- DASGVLTELEAGASAPQ | ||||||||

| 3- SGVLTELEETHSK | ||||||||

| 4- EHGVTVAFVHFGNTK | ||||||||

| 5- DASGVLTELEETP* | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 8 | 1- DQFTGAAPIFIK | AAX11353 | Myoglobin 2 | Paragonimus westermani | - | 4.186 | W | |

| 2- LQGLTLFPVGQSEGIR | ||||||||

| 3- LLKKTNPSVLEER | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 9 | 1- IIFELYTTLPK | AAT73777 | TRIM5/Cyclophilin A Fusion Protein | Aotus trivirgatus | - | 6.171 | RW | W1-2 |

| 2- HVVFGEVTPGYDVVK | ||||||||

| 3- MEALGSASGQTSK | XP_721313 | Cyclophilin Type Peptidyl-Prolyl Cis-Trans Isomerase | Candida albicans | |||||

| 4- HVVFGEVTEGFDVVK | ATT91286 | Putative Cyclophilin | Paxillus involutus | |||||

| 5- IIPQMESQGGDFTGGATGTGGK | P0C1I2 | Cyclophilin E | Rhizopus oryzae | |||||

| 6- FFDITADGSALG* | XP_721313 | Cyclophilin Type Peptidyl-Prolyl Cis-Trans Isomerase | Candida albicaximus | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 10 | 1- IATVTVGDVKAV* | Q9U1G6 | FABP Type III | F. hepatica | - | 4.863 | MR | W1 |

|

| ||||||||

| 11 | 1- GPGTAMPFALK | AAW26651 | SJCHGC05973 Protein (GATase1_DJ-1) | Schistosoma japonicum | TM(1) | 0.305 | W1 | |

| 2- ITSYPGFEDK | ||||||||

| 3- KITSYPGFEDK | ||||||||

| 4- WTYCSGFGVVVDGNLVTSR | ||||||||

| 5- IVAAICAAPIGLQPLAAALGR | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 12 | 1- IEIGLFGATVPK* | XP_001174161 | Peptidylprolyl Isomerase B | P. Troglodytes | - | 0.324 | RW | W1-2 |

| 2- DFMLQGGDFTDGDGTL* | O93826 | Peptidyl-Prolyl Cis-Trans Isomerase B | Arthroderma benhamiae | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 13 | 1- AVPDKIDWR | AAR99518 | Cathepsin L1 Protease | F. hepatica | SP | 0.985 | MRW | W1 |

| 2- MCGIASLASLPMVAR* | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 14 | 1- ISMIEGAAMDLR* | ADP09370 | Mu Class GST (GST 7, 26, 27, 28 or 47) | F. hepatica | - | 3.681 | MRW | W1 |

|

| ||||||||

| 15 | 1- ISMIEGAAMDLR | ADP09370 | Mu Class GST (GST 51) | F. hepatica | - | 1.884 | MRW | W1 |

| 2- HGMLGSTPEER | ||||||||

| 3- YLAPQCLEDFPK | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 16 | 1- AYGVLDEEQGNTYR* | CAA06158 | Thiol-Specific Antioxidant Protein (TPX) | F. hepatica | TM(1) | 1.604 | RW | W1-3 |

|

| ||||||||

| 17 | 1- VVIAYEPVWAIGTGK* | AAZ57433 | Triose-Phosphate Isomerase | Orientobilharzia turkestanicum | - | 1.617 | RW | W1 |

| 2- VASGAFTGEISPAMIR | ||||||||

| 3- IFGESDELIGEK* | ||||||||

| 4- IIYGGSVTAANCK | BAF62292 | Triose Phosphate Isomerase | Schistosoma haematobium | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 18 | 1- VAVLGASGGIGQEGVLLLK | ABD77293 | Mitochondrial Malate Dehydrogenase 2 | Canis familiaris | EM, TM(1) | 1.038 | R | W1-2 |

| 2- AQGSATLSMAYSGVR | AAT35230 | Mitochondrial Malate Dehydrogenase | Clonorchis sinensis | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 19 | 1- ATEQVLAFTYK* | AAO85503 | Aldolase | Pecten maximus | - | 0.441 | RW | W1-3 |

| 2- PTFAQYLQPEQEAK | ABF55380 | Fructose-1, 6-Bisphosphate Aldolase | S. japonicum | |||||

| 3- LVDHLIQDGIIPGIK | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 20 | 1- VPTADVSVVDLTCR | AAG23287 | Glyceraldehyde Phosphate Dehydrogenase | F. hepatica | EM, TM(1) | 0.583 | MR | W1 W3 |

| 2- FPYDITIDQNK | AAA16243 | Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase | S. japonicum | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 21 | 1- AVANVNSQIAPNLIK | Q27655/A53665 | Enolase (2-Phosphoglycerate Dehydrogenase)/Phosphopyruvate Hydratase | F. hepatica | - | 1.345 | MRW | W1-2 |

|

| ||||||||

| 22 | 1- QEYDESGPGIVHR* | AAW25537 | SJCHGC06318 Protein Actin | S. japonicum | TM(2) | 4.769 | MRW | W1-3 |

| 2- SYELPDGQVITIGNER | ABQ65136 | Actin | Trichoderma atroviride | TM(1) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| 23 | 1- GTATLGGTCLNVGCIPSK* | YP_001202603 | Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase | Bradyrhizobium sp. | TM(1) | 0.814 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| 24 | 1- LIYSPTGALNTDTADIR | AAV59016 | Leucyl Aminopeptidase | F. hepatica | - | 0.448 | W | W1 |

| 2- NSVGADSYVADEILVAR | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 25 | 1- NQVAMNPNSKVFDAK | ABS52704 | Heat Shock Protein 70 | F. hepatica | - | 2.386 | W | W1-3 |

| 2- TAGDTHLGSLTFDNR* | ||||||||

| 3- TPSYVAFTDTER* | ||||||||

Results from sequence analysis looking for signal peptides (SP), exportation to mitochondria (EM) and trans-membrane domains (TM). If TM was denoted the number of domains is reported in parentheses.

If the identified proteins have been identified in a previous proteomics analysis of F. hepatica ES products they have been denoted with M, R or W for the studies of Morphew et al. (2007), Robinson et al. (2009) and Wilson et al. (2011) respectively.

If proteins have been identified by Wilson et al. (2011) in tegumental preparations they have been denoted with W1, W2 or W3. W1- Cytosolic fraction; W2- Membrane associated; W3- Final pellet.

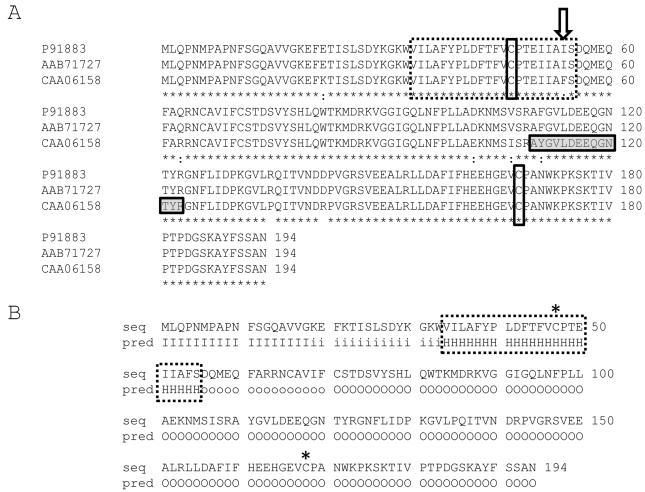

Functional analysis of the identified FhTeg proteins revealed sixteen cytosolic and cytoskeletal proteins; fifteen of which had previously been seen in vitro culture as ES products (Table 1; Morphew et al., 2007; Robinson et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2011). Only spot 6, Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase, had not been found in proteomic studies of ES products. Additional sequence analysis looking for sequence motifs identified two proteins containing a signal peptide (Cathepsin L and methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase), 4 proteins predicted to have a peptide to initiate export to the mitochondria (methylmalonyl-CoA epimerase, malate dehydrogenase, GAPDH and heat responsive protein, the later 3 also containing TM domains) and 4 proteins that were predicted to only contain TM domains (dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase [DlDH], thiroredoxin peroxidase [TPX; Figure 2; GenBank ID: CAA06158], SJCHGC05973 protein [DJ-1] and actin) and not signal peptides or mitochondrial exportation peptides. In the case of DJ-1, only the F. hepatica EST sequence has a predicted TM domain, not the Schistosoma japonicum sequence used for assigning identity. Interestingly, the identified TPx (GenBank ID: CAA06158) was predicted to have a TM domain (Figure 2) and is the only F. hepatica TPx to do so.

Figure 2. Transmembrane domain prediction in F. hepatica TPx.

HMMTop prediction of TM domains in the identified TPx and Genbank deposited sequences of TPx. A) Multiple alignment performed in ClustalW available at EBI. Boxed and shaded sequence indicates matched sequence from MSMS. Boxed with a dashed outline indicates the predicted TM helix (amino acids 34-55) using HMMTop version 2.0 for sequence CAA06158 only as a result of the amino acid switch I54F (indicated with an arrow). Conserved cysteine residues for 2-Cys peroxiredoxins are boxed. B) HMMTop output from an analysis of F. hepatica TPx (CAA06158). Conserved 2-Cys peroxiredoxins are marked with a *. I – Inside loop; i – inside tail; o – outside tail; O – Outside loop.

Of the identified proteins predicted to have TM domains, all bar two appear to be of mitochondrial origin. Three had combined prediction of a peptide for mitochondrial exportation and a TM domain and two (DJ-1 and Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase) are well recognised mitochondrial proteins despite the absence of an exportation peptide (Supplementary Table 2). Of the remaining two, TPx has previously been predicted, and indeed identified (Robinson et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2011), as secretory or cytosolic. Therefore, caution with the TM domain prediction must be taken as it overlaps the conserved cysteine residue at position 47. However, 1-cys peroxiredoxins are known to occur in helminths but it is normally cys107 that is lost (McGonigle et al., 1998). It remains to be tested, via site directed mutagenesis, whether this TPx isoform can function without cys47.

The present study has identified many ES proteins soluble in NP-40 with no integral membrane proteins, such as plasma membrane enzymes or transporters, identified. However, many of the identified NP-40 soluble proteins have previously been found surface expressed or in tegument preparations from other helminths (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2). This suggests that the FhTeg ‘anti-inflammatory’ preparation consists primarily of ES proteins and NP-40 soluble membrane-associated proteins. It is possible that the immune modulatory effects of FhTeg could stem from this pool of NP-40 soluble proteins. In addition, the possibility of the active immune modulation properties of FhTeg coming from glycoconjugates or glycolipids released during NP-40 extraction cannot be ruled out. As the tegument surface barrier is under immune assault within a chemical hostile host environment it is not surprising to identify proteins functioning in aspects such as detoxification, transport, glycolysis and structural integrity. Additionally, the tegument is energetically costly to maintain and, therefore, it is logical that many of the identified proteins are mitochondrial and function to provide the energy requirements needed and proteins functioning to protect mitochondrial integrity from oxidative stress.

Unlike other parasitic flatworm studies (Braschi et al., 2006; Pérez-Sánchez et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2011) there was a noted presence of excretory/secretory proteins in the F. hepatica immune-modulating preparation FhTeg. However, the only protein identified containing a signal peptide, and not for exportation to mitochondria, was a cathepsin L protease. These proteases are found abundantly in the ES products (Morphew et al., 2007) but have also been shown to be absorbed into the glycocalyx of Fasciola sp. (Meemon et al., 2010). However, no cathepsin L or B activity was observed in our preparation of FhTeg as measured by enzyme assay (unpublished data) suggesting there are negligible levels of cathepsin proteases too low to quantify or there are, potentially inactive, cathepsins bound to the tegument to act as an immunological smoke screen once the tegument is shed.

Our proteomics assay has revealed a pool of proteins potentially involved in immune modulation, albeit recognising the potential contribution of glycoconjugates and glycolipids. Individually cloning promising targets or returning to previously studied proteins will further delineate which proteins, if any, possess immune-modulatory effects on the host (Hamilton et al., 2009). To this end, many of the identified FhTeg proteins have previously been shown to interact with the host immune system in liver fluke or in other systems. Cathepsin L proteases have been shown to suppress IL-10, IL-6, and IFN-γ (O’Neill et al., 2001) via an IL-4 dependent mechanism and can suppress Th17 immune responses in vivo (Dowling et al., 2010) and enolase has previously shown immune modulating properties in other systems (Ferreira et al., 1997). Furthermore, TPx which constituted 1.6 % of the FhTeg NP-40 extracted protein has been reported to recruit alternatively activated macrophages in a murine model of F. hepatica infection in vitro, producing prostaglandin E2, IL-10 and TGF-β, with little IL-12 and IFN-γ (Donnelly et al., 2005) suggesting that TPx may be, in part, involved in the suppression seen using FhTeg.

An identified Mu class glutathione transferase (GST) is an anti-oxidant that belongs to a family of multi-functional enzymes involved in the detoxification of many physiological substances. This antigen constitutes a significant proportion (over 5 %) of FhTeg and was shown to significantly suppress nitric oxide (NO) production by rat peritoneal macrophages, and induce a decrease in proliferative response by spleen cells to Con A or LPS in a dose dependent manner (Cervi et al., 1999). Therefore, as with TPx, Mu class GSTs may be involved, at least in part, in the immune modulation by FhTeg.

Our previous work, has shown that FhTeg targeted the transcription factor NF-κBp65 subunit of the NF-κB complex (Hamilton et al., 2009). Similar immune modulation effects have also been documented in other parasitic organisms including Toxoplasma gondii (Butcher et al., 2001). Further study on T. gondii virulent and avirulent phenotypes demonstrated that the inhibition of NF-κB activity, along with the protection against NO induced cellular pathology is associated with HSP70 (Dobbin et al., 2002). Here it was observed that virulent phenotypes expressing increased HSP70 inhibited NF-κB activity and the transcription of inducible NO synthase. The authors suggested that HSP70 is part of a parasite survival strategy to down-regulate host parasiticidal mechanisms (Dobbin et al., 2002). In helminths, HSP70 proteins were previously indicated in the anti-inflammatory modulation response required to successfully establish infection within their host. In Echinostoma caproni and E. friedi increased HSP70 expression and secretion was correlated to chronic infections in hamsters and not in hosts (rats) supporting acute infections (Bernal et al., 2006; Higon et al., 2008). Furthermore, in Fasciola sp., HSP70 expression in F. gigantica was relatively higher than the expression in F. hepatica from a refractory sheep host than a sheep supporting acute infections. In addition, HSP70 was lower in F. hepatica from a sheep host supporting acute infections compared to F. hepatica from chronic infection in cattle (Smith et al., 2008) suggesting HSP70 expression increases to counteract more pronounced host inflammatory responses.

As HSP70 makes a significant contribution to FhTeg (2.4 %) it is possible that it could also be involved in the previously reported anti-inflammatory effects targeting NF-κBp65. In Fasciola sp., HSP70 has been found previously in the ES products (Wilson et al., 2011). However, looking at the ratios (EmPAI for Wilson et al. (2011) and % contributions for the current study) of FABP type I (Fh15) to HSP70 in the two preparations (EmPAI 1:0.40; % contributions 1:0.95) there is over a 2-fold greater level of HSP70 in FhTeg compared to ES products. This enrichment of HSP70 may account for the different effects seen between FhTeg and the ES products on the immune system (Hamilton et al., 2009; O’Neill et al., 2001).

4. Conclusions

This study has revealed the protein pool of a novel immune modulating preparation of adult F. hepatica, by 2DE and subsequently identified by mass spectrometry, to consist of ES and membrane associated proteins. The proteomics assay data increases understanding, at the protein level, of the novel anti-inflammatory mechanisms exploited by F. hepatica, and for example, highlighted HSP70 as a potential immune modulating molecule in this species. Native purification or recombinant production of the individual members of the FhTeg protein pool will provide the opportunity to confirm which individual proteins are responsible for the immunosuppressive activity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr Jim Heald and Dr Charly Potter for their MS skills. The authors acknowledge the support of the BBSRC UK (BBH0092561) and the Wellcome Trust (Grant WT094907MA).

Abbreviations

- FhTeg

Fasciola hepatica NP-40 released proteins

- NO

Nitric oxide

- ES

Excretory/Secretory

References

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, Harris MA, Hill DP, Issel-Tarver L, Kasarskis A, Lewis S, Matese JC, Richardson JE, Ringwald M, Rubin GM, Sherlock G. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal D, Carpena I, Espert AM, De la Rubia JE, Esteban JG, Toledo R, Marcilla A. Identification of proteins in excretory/secretory extracts of Echinostoma friedi (Trematoda) from chronic and acute infections. Proteomics. 2006;6:2835–2843. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boray JC. Chemotherapy of infections with fasciolidae. In: Boray JC, editor. Immunology, pathobiology and control of Fasciolosis. MSD AGVET; Rahway, New Jersey: 1997. pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Brady MT, O’Neill SM, Dalton JP, Mills KHG. Fasciola hepatica Suppresses a Protective Th1 Response Against Bordetella pertussis. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:5372–5378. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5372-5378.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braschi S, Curwen RS, Ashton PD, Verjovski-Almeida S, Wilson A. The tegument surface membranes of the human blood parasite Schistosoma mansoni: A proteomic analysis after differential extraction. Proteomics. 2006;6:1471–1482. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher BA, Kim L, Johnson PF, Denkers EY. Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites inhibit proinflammatory cytokine induction in infected macrophages by preventing nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-kappa B. J Immunol. 2001;167:2193–2201. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervi L, Rossi G, Masih DT. Potential role for excretory-secretory forms of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) in Fasciola hepatica. Parasitology. 1999;119:627–633. doi: 10.1017/s003118209900517x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbin CA, Smith NC, Johnson AM. Heat shock protein 70 is a potential virulence factor in murine Toxoplasma infection via immunomodulation of host NF-kappa B and nitric oxide. J Immunol. 2002;169:958–965. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly S, O’Neill SM, Sekiya M, Mulcahy G, Dalton JP. Thioredoxin peroxidase secreted by Fasciola hepatica induces the alternative activation of macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:166–173. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.166-173.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling DJ, Hamilton CM, Donnelly S, La Course J, Brophy PM, Dalton J, O’Neill SM. Major Secretory Antigens of the Helminth Fasciola hepatica Activate a Suppressive Dendritic Cell Phenotype That Attenuates Th17 Cells but Fails To Activate Th2 Immune Responses. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:793–801. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00573-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira P, Bras A, Tavares D, Vilanova M, Ribeiro A, Videira A, Arala-Chaves M. Purification, and biochemical and biological characterization of an immunosuppressive and lymphocyte mitogenic protein secreted by Streptococcus sobrinus. Int. Immunol. 1997;9:1735–1743. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.11.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CM, Dowling DJ, Loscher CE, Morphew RM, Brophy PM, O’Neill SM. The Fasciola hepatica Tegumental Antigen Suppresses Dendritic Cell Maturation and Function. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:2488–2498. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00919-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higon M, Monteagudo C, Fried B, Esteban JG, Toledo R, Marcilla A. Molecular cloning and characterization of Echinostoma caproni heat shock protein-70 and differential expression in the parasite derived from low- and high-compatible hosts. Parasitology. 2008;135:1469–1477. doi: 10.1017/S0031182008004927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigle S, Dalton JP, James ER. Peroxidoxins: A new antioxidant family. Parasitol. Today. 1998;14:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meemon K, Khawsuk W, Sriburee S, Meepool A, Sethadavit M, Sansri V, Wanichanon C, Sobhon P. Fasciola gigantica: Histology of the digestive tract and the expression of cathepsin L. Exp. Parasitol. 2010;125:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morphew RM, Wright HA, LaCourse EJ, Porter J, Barrett J, Woods DJ, Brophy PM. Towards Delineating Functions within the Fasciola Secreted Cathepsin L Protease Family by Integrating In Vivo Based Sub-Proteomics and Phylogenetics. Plos Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2011;5:e937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000937. doi:910.1371/journal.pntd.0000937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morphew RM, Wright HA, LaCourse EJ, Woods DJ, Brophy PM. Comparative Proteomics of Excretory-Secretory Proteins Released by the Liver Fluke Fasciola hepatica in Sheep Host Bile and During In Vitro Culture Ex-Host. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:963–972. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600375-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill SM, Brady MT, Callanan JJ, Mulcahy G, Joyce P, Mills KHG, Dalton JP. Fasciola hepatica Infection Down Regulates Th1 Responses in Mice. Parasite Immunol. 2000;22:147–155. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2000.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill SM, Mills KHG, Dalton JP. Fasciola hepatica cathepsin L cysteine proteinase suppresses Bordetella pertussis-specific interferon-gamma production in vivo. Parasite Immunol. 2001;23:541–547. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2001.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Sánchez R, Ramajo-Hernández A, Ramajo-Martín V, Oleaga A. Proteomic analysis of the tegument and excretory-secretory products of adult Schistosoma bovis worms. Proteomics. 2006;6:S226–S236. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MW, Menon R, Donnelly SM, Dalton JP, Ranganathan S. An Integrated Transcriptomics and Proteomics Analysis of the Secretome of the Helminth Pathogen Fasciola hepatica: Proteins Associated With Invasion and Infection of the Mammalian Host. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2009;8:1891–1907. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900045-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RE, Spithill TW, Pike RN, Meeusen ENT, Piedrafita D. Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica: Cloning and characterisation of 70 kDa heat-shock proteins reveals variation in HSP70 gene expression between parasite species recovered from sheep. Exp. Parasitol. 2008;118:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RA, Wright JM, de Castro-Borges W, Parker-Manuel SJ, Dowle AA, Ashton PD, Young ND, Gasser RB, Spithill TW. Exploring the Fasciola hepatica tegument proteome. Int. J. Parasitol. 2011;41:1347–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.