Abstract

Mindfulness Training (MT) is an emerging therapeutic modality for addictive disorders. Non-judgment of inner experience, a component of mindfulness, may influence addiction treatment response. To test whether this component influences smoking cessation, tobacco smokers (n=85) in a randomized control trial of MT vs. Freedom from Smoking (FFS), a standard cognitive-behaviorally-oriented treatment, were divided into split-half subgroups based on baseline Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire non-judgment subscale. Smokers who rarely judge inner experience (non-judgment > 30.5) smoked less during follow-up when randomized to MT (3.9 cigs/d) vs. FFS (11.1 cigs/d), p <0.01. Measuring trait non-judgment may help personalize treatment assignments, improving outcomes.

Keywords: nicotine, mindfulness, cognitive-behavioral therapy, clinical trial, cigarette, non-judge, freedom from smoking

1. Introduction

Tobacco smoking is the most common cause of preventable death and disease in the US, accounting for approximately 438,000 premature deaths annually (Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004). Pharmacotherapy is effective and universally recommended (Wallace, 2011), and it is recommended to be used in conjunction with behavioral therapy (Fiore MC, May 2008). Several types of behavioral smoking cessation programs have demonstrated efficacy; however, relapse is an enormous problem that is poorly understood. Usually only about 5-20% of smokers remain abstinent 6 months after a cessation attempt (Mottillo et al., 2009). There is substantial evidence that Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) oriented smoking cessation groups are more effective for smoking cessation than self-help (Stead & Lancaster, 2005); however, even with this current gold standard approach, a majority do not attain abstinence on a given cessation attempt. Some may benefit from an alternative approach to smoking cessation.

Finding a way to successfully match people with different types of behavioral interventions and to appropriate levels of care has long been a goal in treatment of addictive disorders (Project MATCH Research Group, 1997), and has generally focused on matching based on motivation (Witkiewitz, Hartzler, & Donovan), stage of change (Dijkstra, Conijn, & De Vries, 2006) or level of care based on acuity and co-morbidity (Gastfriend & McLellan, 1997). However, these approaches do not necessarily address differences in psychological characteristics among those seeking smoking cessation treatment or entering into substance abuse treatment. If a simple psychometric instrument could identify which tobacco smokers in a population would do poorly with standard behavioral smoking cessation programs, yet would be more likely to be successful when engaged in alternative treatment approaches, then this form of treatment matching could improve overall treatment outcomes and save lives.

One potential alternative to standard behavioral smoking cessation treatment is Mindfulness Training (MT) (Brewer et al., 2011). MT is an increasingly popular behavioral intervention within healthcare settings (Ludwig & Kabat-Zinn, 2008) and is now emerging as a promising treatment in substance use disorders (SUD) (Bowen & Marlatt, 2009; Brewer, Bowen, Smith, Marlatt, & Potenza). Early studies of mindfulness-oriented therapies demonstrated promise for addiction treatment, with reported effects on attention networks (Brefczynski-Lewis, Lutz, Schaefer, Levinson, & Davidson, 2007), stress reactivity (Brewer et al., 2009), ability to discriminate between craving and negative affect (Witkiewitz & Bowen), and perceptions of improved impulse control (Margolin et al., 2007). Several mindfulness-oriented therapies have been tested in clinical trials for addictive disorders with mixed results when compared to active control groups (Bowen et al., 2009; Brewer et al., 2011; Margolin, Beitel, Schuman-Olivier, & Avants, 2006; Zgierska et al., 2009). Despite evidence for efficacy on underlying mechanisms of change thought to be important for addiction treatment, MT has not consistently demonstrated greater overall effectiveness as compared to active controls, such as CBT (Zgierska et al., 2009). Therefore, the challenge lies in identifying whether some might benefit preferentially from a mindfulness-oriented approach while others may benefit from CBT or other standard approaches (Hofmann, Sawyer, & Fang, 2010).

Mindfulness can be defined as purposeful, present-moment awareness with non-judgment of and non-reactivity to emergent internal and external stimuli (Kabat-Zinn, 1990). Encouraging non-judgment of inner experience is a major theme in standardized mindfulness courses given within general healthcare settings (Ludwig & Kabat-Zinn, 2008). Enhancing non-judgment of inner experience in people with depression, for example, may reduce the detrimental effects of ruminative negative thoughts and self-representations (Eisendrath, Chartier, & McLane, 2012). Similarly, a recent study of college students suggested non-judgment of inner experience is associated with fewer alcohol-related negative consequences (Fernandez, Wood, Stein, & Rossi, 2012), suggesting potential usefulness of Mindfulness Training in substance use disorders.Though the idea of measuring mindfulness by self-report has received some controversy (Grossman, 2008), one commonly used measure of trait mindfulness is the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006; Baer et al., 2008). The subscale measuring non-judgment of inner experience (FFMQ non-judgment) is made up of eight items, which assess the tendency to judge one's own thoughts, emotions, urges, and feelings. The FFMQ non-judgment subscale has been strongly associated with positive change on measures of psychological well-being among healthy controls exposed to mindfulness meditation training (Baer et al., 2008). While non-judging of inner experience (FFMQ non-judgment) has been associated with positive outcomes in healthy controls, people with depression, or even non-dependent alcohol misuse, it remains unknown whether it will also be associated with positive outcomes in addiction treatment.

Illustrating this point is a paradoxical finding from a small pilot observational study of opiate-dependent heroin users entering buprenorphine treatment in which high levels of trait FFMQ non-judgment were strongly correlated with positive toxicology screening for illicit drugs during 12 weeks of abstinence-focused, CBT-oriented group therapy (Schuman-Olivier, Albanese, Carlini, & Shaffer, 2011). The treatment model in this pilot study encouraged identification, categorization, and then confrontation of maladaptive internal experiences (e.g., triggers, craving, addict thinking, etc.) that could lead to substance use relapse. Contrary to a growing body of evidence reporting non-judgment of inner experience may be beneficial in non-addicted samples, this pilot study suggested people with high FFMQ non-judgment may not do well in standard substance dependence treatment. These people may require matching to alternative treatments that support their tendency towards non-judgment.

In this context, we hypothesized that we may observe an unfavorable effect of high FFMQ non-judgment on smoking cessation outcomes during CBT-oriented smoking cessation treatment. Further, we hypothesized that Mindfulness Training may enhance the therapeutic potential of trait non-judgment of inner experience. We sought out a controlled trial dataset specifically to test these pre-existing hypotheses. In this study, we aimed to assess the moderating effect of non-judgment of inner experience during smoking cessation treatment in the context of a randomized controlled trial comparing Mindfulness Training (MT) and CBT with the American Lung Association's CBT-oriented Freedom from Smoking (FFS) treatment.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study was a secondary analysis of a randomized, controlled, pilot clinical trial with a 4-week treatment phase with either MT or FFS (CBT) and post-treatment follow-up interviews at 6, 12 and 17 weeks after treatment initiation (Brewer et al., 2011). It was approved by the Yale University and Veteran's Administration institutional review boards. A computer-generated urn randomization program assigned participants to MT or FFS based on age (>40 years vs. ≤40 years old), sex, race (white vs. non-white), and cigarettes smoked/day (>20 vs. ≤20). Full details of the study method have been published (Brewer et al., 2011).

2.2. Participants

Participants were recruited through flyers and media advertisements offering behavioral treatment for smoking cessation. Those eligible were 18–60 years of age, smoked more than 10 cigarettes per day, had less than 3 months of abstinence in the past year, and reported interest in quitting smoking. Participants were excluded if they currently used psychoactive medications, had a serious or unstable medical condition in the past 6 months, or met DSM-IV criteria for other substance dependence in the past year. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Of the 103 eligible individuals, 88 were randomly assigned to receive MT or FFS; however, 3 did not complete baseline assessments necessary for inclusion in this analysis, resulting in a final sample of 85 subjects.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic characteristics

Data on race, gender, age, and meditation experience were collected at the baseline visit

2.3.2. Smoking status

Self-reported smoking was assessed at in-person weekly visits during treatment, and at study weeks 6, 12 and 17 representing the follow-up, via the timeline follow back (TLFB) method (Sobell, Brown, Leo, & Sobell, 1996). The primary smoking dependent variable was average number of cigarettes self-reported smoked per day during the past week recorded during the 12 week follow-up period (i.e., week 5-17). Additionally, self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence was biochemically verified by an exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) measurement of ≤10 parts per million at end of treatment (i.e., week 4) and at end of follow-up (i.e., week 17).

2.3.3. Nicotine Dependence

Baseline levels of nicotine dependence were measured using the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND), a well-validated measure for severity of nicotine dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991).

2.3.4. Non-judgment of inner experience

Smokers completed the entire Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), a 39-item measure of dispositional mindfulness using a Likert five-point scale, at baseline (Baer et al., 2008). This measure includes five subscales with 6-8 items each, including observe, describe, and non-react, as well as two fully reverse coded subscales, act-aware and non-judgment (Baer et al., 2006). Alpha coefficients for the FFMQ facets were acceptable to good (0.72 to 0.92), with inter-correlations suggesting related but distinct constructs (0.32-0.56) (Baer et al., 2008). Reverse-coded FFMQ non-judgment items, which represent non-judgment of inner experience, include the following: I criticize myself for having irrational or inappropriate emotions; I tell myself I shouldn't be feeling the way I'm feeling; I believe some of my thoughts are abnormal or bad and I shouldn't think that way; I make judgments about whether my thoughts are good or bad; I tell myself that I shouldn't be thinking the way I'm thinking; I think some of my emotions are bad or inappropriate and I shouldn't feel them; When I have distressing thoughts or images, I judge myself as good or bad, depending what the thought/image is about; I disapprove of myself when I have irrational ideas. Test-retest reliability of the non-judgment subscale is excellent (Interclass correlation, ICC =0.84) with good internal consistency (α = 0.89) (Veehof, Ten Klooster, Taal, Westerhof, & Bohlmeijer, 2011). The FFMQ non-judgment subscale ranges from 0 - 40 with means in community samples and clinical populations ranging from 23.85 (7.33) to 29.13 (5.79) compared with meditators, 32.4 (5.63) (Baer et al., 2008; Veehof et al., 2011). We split the sample of 85 subjects in half to discriminate subjects with high and low FFMQ non-judgment using the mean sample score of 30.5 as the cut off.

2.4. Treatment

All participants received twice weekly manualized group sessions (eight total) delivered by instructors experienced in either Mindfulness Training (a single, board-certified psychiatrist with greater than13 years of mindfulness practice) or certified in Freedom From Smoking (2 therapists with masters (+) level of training in drug counseling/health psychology with a FFS certification). FFS was chosen as an active ‘standard treatment’ comparison condition for several reasons: (1) it has demonstrated efficacy, (2) it is manualized and standards for training and certification of therapists are established, (3) it is widely available, and (4) it includes components well-matched with MT, such as relaxation training and home practice, but it does not include a mindfulness orientation (McGovern & Lando, 1992; Rosenbaum & O'Shea, 1992). For example, both MT and FFS had a quit date at the end of week 2 (session four), were matched for length (1.5 h/session) and delivered on the same days of the week (Monday and Thursday). In addition, home practice materials were matched in a number of ways, including the length (~30 min total) and number of tracks (five) on respective CDs. Participants were neither encouraged nor discouraged from using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) during active treatment or in the post-treatment follow-up phase, and few in either group chose to use NRT [5]. No medications were prescribed for smoking cessation. Detailed descriptions of the content of MT and FFS interventions are described elsewhere (Brewer et al., 2011).

Mindfulness Training introduced a body scan technique for the purpose of observing body sensations associated with the experience of craving without judgment. Smoking mindfully was encouraged to really experience the aversive body sensations associated with cigarette inhalation. Aspiration-setting modules encouraged the development of a gentle but firm intention to quit smoking. Craving cards were used to monitor triggers and the experience of craving in a non-judgmental way. In addition to teaching how to be mindful of mental contents, a mindful response to craving was emphasized, including use of a mnemonic RAIN (Recognize/ Accept/ Investigate/ Note). Home practice was suggested after each session typically as a combination of formal (e.g., practicing sitting mindfulness meditation of breath, body sensation, or thoughts) and informal (e.g., RAIN, mindful walking) techniques. Each participant received a practice CD of mindfulness techniques (Brewer et al., 2011).

The FFS treatment program included behavior modification, stress reduction, and relapse prevention, and was divided into three stages: preparation, action, and maintenance. In the preparation stage (sessions 1–3), participants examined smoking patterns through self-monitoring, (e.g. “Pack Tracks”) focused on triggers for smoking and moods related to urges to smoke, and developed a personalized quit day plan. On quit day (session 4), participants affirmed their decision to quit smoking and identified specific coping strategies they would utilize on that day, generally focusing on distraction, delay, and alternative reinforcers, as well as avoiding the experience. During the maintenance stage, participants identified ways to remain smoke-free and to maintain a healthy lifestyle (e.g., weight management, exercise, and relapse prevention), and continued to discuss the importance of social support, stress management and relaxation strategies. Home practice was suggested after each session, typically as a combination of formal (e.g., practicing guided relaxation techniques) and informal (e.g., “Pack Tracks” prior to the quit date) techniques. Each participant received a practice CD of relaxation techniques (American Lung Association, 1993; Daughton, Kass, Fix, Ahrens, & Rennard, 1986).

2.5. Data analysis

Our primary aim was to test the aprioiri hypotheses that baseline non-judgment of inner experience would hinder smoking cessation in CBT-oriented treatment, while potentially facilitating smoking cessation in Mindfulness Training. Therefore, we focused our primary analysis on the FFMQ non-judgment subscale, assessed at baseline, testing for a moderation effect of the two behavioral treatments on smoking outcomes during 12 weeks of follow-up. In preliminary analyses, we tested for predictors of study retention using logistic regression. We included significant predictors of retention in subsequent models as covariates to adjust for systematic differences between study completers and non-completers. Then we used longitudinal mixed models (SAS Proc Mixed) for the main analysis. Independent variables were treatment group (MT vs. FFS) and baseline FFMQ non-judgment groups (High vs. Low). An interaction between treatment group and FFMQ non-judgment was evaluated in order to assess for a moderating effect of FFMQ non-judgment on group assignment with respect to smoking outcomes. We included significant predictors of retention (race, race × gender) in our models as covariates. Additional covariates included history of meditation practice (because it may represent prior exposure to Mindfulness Training) and FTND (because it is strong predictor of smoking cessation outcomes). Post-hoc testing was conducted using Tukey tests.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Baseline and demographic characteristics were comparable in all 4 group permutations of treatment group (MT/FFS) × FFMQ non-judgment (high/low) (n=85) (Table 1). In this sample, the mean value for FFMQ non-judgment subscale was 30.5 (6.3) with scores ranging from 15-40, and a 10 point difference between the mean scores in the high and low FFMQ non-judgment groups.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| MT (n=39) | FFS (n=46) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low FFMQ (n=22) | High FFMQ (n=17) | Low FFMQ (n=21) | High FFMQ (n=25) | sig. | |

| FFMQ non-judge, mean (SD) | 25.2 (3.6) | 34.9 (2.5) | 25.1 (4.0) | 36.2 (3.2) | *** |

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.3 (8.9) | 47.7 (8.3) | 41.7 (12.1) | 48.3 (10.0) | |

| FTND, mean (SD) | 5.9 (1.9) | 6.1 (1.7) | 5.9 (1.9) | 4.5 (2.3) | * |

| Baseline cigarettes per day, mean (SD) | 19.0 (7.0) | 22.5 (12.5) | 20.6 (10.0) | 17.6 (6.5) | |

| Race, W%/B% | 59.1 /36.4 | 53.0 /41.2 | 33.3 /47.6 | 48.0 /36.0 | |

| Female, % | 45.5 | 23.5 | 38.1 | 44.0 | |

| Meditated before, % | 13.6 | 17.7 | 14.3 | 4.0 | |

| Psychiatric medication, % | 9.1 | 5.9 | 0.0 | 4.0 | |

p<0.05

p<0.0001

3.2. Treatment Exposure and Retention

Eighty-four percent of participants were exposed to treatment (n=71), 72% completed treatment (n=61). All participants who completed treatment also completed follow-up (n=61). Group assignment, gender, baseline FFMQ non-judgment, meditation experience, nicotine dependence & baseline cigarettes per day were not associated with treatment exposure or retention. However, exposure to treatment was associated with race (white: 94% v. black: 68%) and, in particular, black females had poorer treatment retention (white male = (23/30) 77%; white female = (17/22) 77%; black male = (18/23) 79%; black female = (3/11) 27%).

3.3. Smoking Outcomes

In analysis of smoking behavior at end of treatment (week 4), which adjusted for relevant covariates, those in the MT group, irrespective of baseline non-judgment group, smoked fewer cigarettes per day than those in the FFS group (F= 4.1, p < 0.05), and had a higher percentage of subjects maintaining biochemically-confirmed, 7-day point prevalence abstinence at end of treatment (i.e., week 4): FFS/Low Non-Judgment (1/21, 5%), MT/Low Non-judgment(5/22, 23%), FFS/High Non-judgment (4/25, 16%), MT/High Non-judgment (5/17, 29%). Importantly, the moderating effect of non-judgment of inner experience on treatment group assignment was not a significant predictor of cigarettes per day at end of treatment (i.e., week 4) (F= 0.99, p = 0.32), but emerged as a predictor during the first week of follow-up (i.e., week 5) (F= 4.7, p < 0.05).

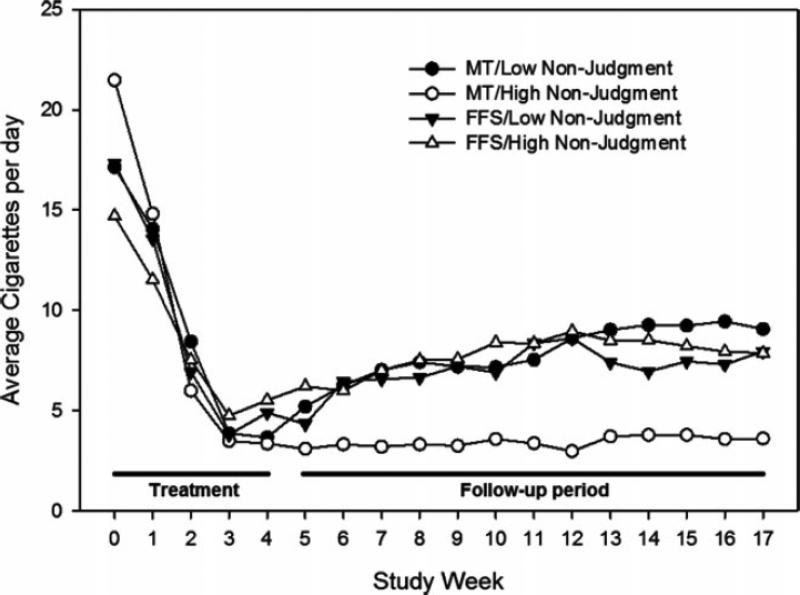

Level of nicotine dependence (FTND) (F (1, 684) =10.7, p <0.01), the interaction of gender and race (BLF >> WHM/WHF > BLM) (F (1, 684) =3.79, p <0.05), and time (F (1, 684) = 20.32, p <0.0001) were all associated with a greater average number of cigarettes smoked during 12 weeks of follow-up. All group combinations decreased cigarette use during treatment; however, those with high FFMQ non-judgment in the MT group were more likely to maintain that decrease while other groups increased their smoking during follow-up (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of interaction of FFMQ nonjudgment and group on cigarette use across time.

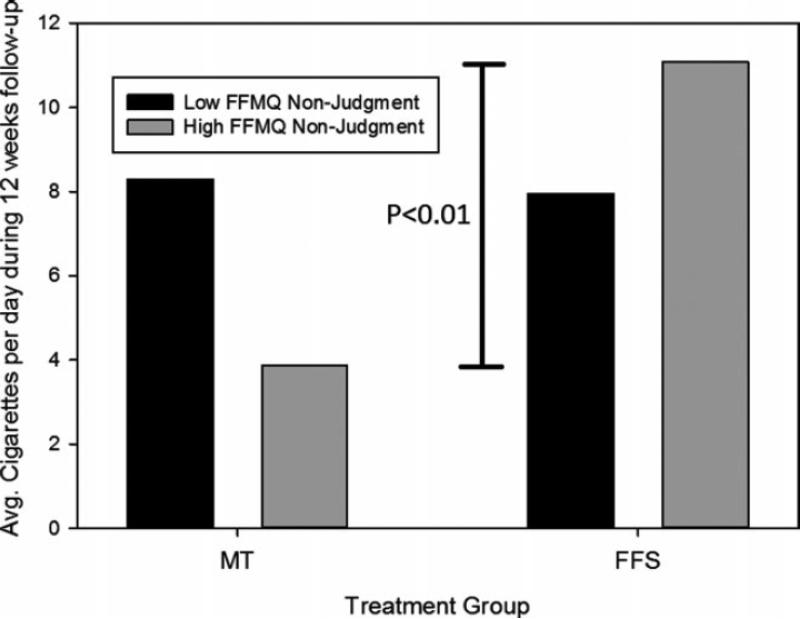

In the analysis of moderating effects of FFMQ non-judgment on smoking outcomes in the follow up period, adjusted for relevant covariates, we found a significant interaction effect between treatment group and FFMQ non-judgment (F (1, 684) = 6.6, p <0.05), and also a main effect of treatment group MT < CBT (F (1, 684) = 4.8, p <0.05) in predicting average cigarettes smoked per day. Among those with high FFMQ non-judgment, least squares mean estimates of average cigarettes per day during follow-up period were lower for MT (3.9 ± 2.2) than FFS (11.1 ± 1.9), (t=3.1, p <0.005, Tukey p <0.01) (Figure 2). Among those in MT group, smokers with high trait FFMQ non-judgment had fewer cigarettes per day during follow-up period (3.9 ± 2.2) than those with low non-judgment (8.3 ± 1.6), (t=2.1, p <0.05, Tukey p = 0.16). Despite the fact that smokers with high FFMQ non-judgment randomized to MT had higher FTND scores and a greater number of cigarettes smoked per day at baseline compared to other groups (Table 1), this group had the highest percentage of subjects with biochemically-confirmed, 7-day point prevalence abstinence at end of follow-up (i.e., week 17): FFS/Low Non-judgment (0/21, 0%), MT/Low Non-judgment (3/22, 14%), FFS/High Non-judgment (2/25, 8%), MT/High Non-judgment (5/17, 29%).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of interaction of FFMQ nonjudgment and group on least square means of cigarette smoking during 12 weeks of follow-up. Note: Figure represents longitudinal mixed model analysis of cigarette use during 12 weeks of follow-up with relevant covariates included in the model. p values represent Tukey post-hoc significance test between MT/High Nonjudgment and FFS/High Nonjudgment.

4. Discussion

This secondary analysis of a small randomized controlled trial found cigarette smokers who rarely judge their inner experiences (high levels of trait non-judgment as assessed with FFMQ) may be more likely to maintain reductions in cigarette smoking following Mindfulness Training than following Freedom from Smoking, a CBT-oriented smoking cessation program. This study did not support our hypothesis that smokers with high non-judgment would do worse in FFS than those with low non-judgment; however, we report that MT may potentiate the therapeutic effect of non-judgment of inner experience during smoking cessation, with an effect of trait non-judgment emerging after completion of group treatment when support is removed. Our findings cautiously suggest that treatment matching based on non-judgment of inner experiences might improve outcomes for some people. Given the limited size of our sample, and the finding of differences only during the follow-up but not the treatment phase, more research is necessary to replicate these findings before recommendation for treatment matching can be supported.

Since all treatment groups had large decreases in average daily smoking during treatment, it is difficult to ascertain the exact cause of the moderation effect of high non-judgment on MT. It is possible the effect is mainly due to either a greater reduction in smoking in the MT/High Non-judgment cell allowing more people to reach abstinence during treatment, or to an enhanced ability to maintain abstinence during the immediate follow-up period, or a combination of both. For this reason, we will examine a few potential mechanisms, underlying this moderation effect of high non-judgment on MT both during and immediately after treatment.

Studies suggest abstinence self-efficacy is the strongest mediator of smoking abstinence during behavioral treatments (Hendricks, Delucchi, & Hall, 2010). Therefore, treatments that nurture strong abstinence self-efficacy are more likely to be effective. The MT treatment model espouses that non-judgment is an essential skill whose acquisition will lead to successful abstinence. Therefore, when people who rarely judge inner experience enter the MT treatment model, they may have higher levels of abstinence self-efficacy. Additionally, their strong attribute of non-judgment may offer greater success with experiential aspects of MT; and therefore greater frequency of mindfulness practice, which has been shown to lead to increased benefit from treatment (Brewer et al., 2011; Carmody & Baer, 2008).

Everybody entering addiction treatment brings a particular worldview as well as certain psychological strengths. When treatment is congruent with a person's pre-existing worldview, then it may be easier to access and understand, allowing it to be more effective. Similarly, if treatment engages a person's area of strength, then that person may be more confident and willing to apply the tools they are learning. Those who lack confidence in their ability to be successful in a given treatment may view treatment as unhelpful or may be perceived as resisting treatment. People who rarely judge inner experience may have either a worldview that values non-judgment of inner experience or an innate ability to avoid categorizing inner experiences as positive or negative.

Within a Mindfulness Training framework, trait non-judgment is viewed as a useful strength. While in other approaches, it may actually be a liability. For instance, CBT-oriented addiction treatment focuses on problem identification, goal setting, cognitive restructuring, and problem solving, which is very helpful for many people (Beck, 1993; Hofmann et al., 2010; Marlatt & Donovan, 2005). However, those who rarely judge their inner experiences may have difficulty categorizing addiction-related thoughts, urges and behaviors as problems as well as perceiving the harmful consequences of their behaviors. If they have difficulty with problem identification or they don't generate feelings of shame or regret about their use, they may lack the motivation to maintain the goal of behavioral change. Notably, many trials of CBT for addictive disorders are preceded by a lead-in phase of motivational interviewing, a non-judgmental approach for clarifying motivation for change, which can enhance CBT skills acquisition (Ulaszek et al., 2012; Witkiewitz et al., 2010).

Mindfulness Training encourages development of a gentle, but firm, intention for non-judgmental awareness of present-moment experience. In Mindfulness Training, smokers are asked to engage in a process of overall perspective change, while simultaneously learning experiential skills useful for coping with triggers and negative affect. For the person with high non-judgment, this perspective change may be syntonic with their worldview or with their innate cognitive abilities, allowing a smoother integration of coping skills, eventually resulting in a more lasting change in the harmful behavior.

Interestingly, we found no effects of trait non-judgment in the MT group during treatment, but these emerged after treatment completion. Therefore, the integration of non-judgmental traits with mindfulness practice may have its most potent effect after a smoker achieves abstinence or a significantly reduces daily smoking, at which point the goal is to prevent a return to regular smoking. One possible explanation is that among individuals who already have this capacity (i.e. high trait non-judgment), MT supports what they already ‘inherently’ know. For those with low trait non-judgment, MT provides the day-to-day practice and support for non-judgment, but this may not be maintained after the end of treatment. A short, 4-week training course may not be sufficient to instill lasting effects in trait-like cognitive schema such as non-judgment (Baer, Carmody, & Hunsinger, 2012). Without further support, one might expect these gains to fall off after treatment completion for those who did not already possess them, but to remain in place for those already high in trait non-judgment. This has several ramifications for treatment delivery beyond treatment matching. First, individuals who at baseline are high in trait non-judgment may benefit from brief Mindfulness Training for addictions, as they may already have the cognitive tools for success, but just need training in how to use them effectively. In contrast, individuals who have low baseline trait non-judgment may require longer treatment, ensuring these new cognitive tools are firmly in place. It may even be possible to use cognitive assessments such as FFMQ non-judgment to serially follow an individual's progress through mindfulness-based treatment. For example, they are not expected to maintain abstinence on their own without group support until after reaching a certain benchmark.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

The main strengths of this study were the use of a randomized controlled trial of MT and FFS with well-matched treatments controlling for both therapeutic contact and mind-body practice dose. The limitations of the study include the moderate sample size, which resulted in small cell sizes for comparing the four groups of interest, thereby limiting both statistical power and the generalizability of these results. The primary outcome measure, average cigarettes per day during follow-up, was the variable with the most power; however, because we did not find significant differences in other outcome variables (e.g., point prevalence abstinence) during and after treatment, the possibility of a false positive result cannot be ruled out. Additionally, even though FFMQ is one of the most commonly used self-report measures of trait mindfulness, there is no universally accepted gold standard for representing the construct of mindfulness (Grossman, 2008). The FFMQ was never validated in this population; therefore, the validity of this measure of mindfulness within this population is uncertain. Additionally, we compared non-judgment groups based on a sample-based mean split, creating high and low FFMQ groups. In the future, it would be best to develop population norms for FFMQ subscale cutoffs using a larger population of smokers, so the positive predictive value of the subscale for identifying appropriate treatment matching could be assessed.

4.2. Future Directions

This study encourages further investigation into use of the FFMQ non-judgment 8-item subscale as a tool for identifying who should be recommended to participate in a mindfulness-oriented intervention instead of standard smoking cessation treatment. This study extends the findings that non-judgment of inner experience may be influential during treatment of substance use disorders. However, the processes required to cut down and stop substance use (i.e. outpatient heroin detoxification or smoking cessation) may be different than those required in early immediate abstinence, or maintenance of abstinence after detoxification (i.e. relapse prevention programs after detoxification for alcohol). The association between non-judgment of inner experience and clinical outcomes may differ between treatment types, forms of substance dependence, and cessation of ongoing substance use versus relapse prevention. Therefore, future studies should be conducted with larger populations of substance users, in different types of substance use disorders, and with attention to timing of mindfulness interventions over the course of addiction treatment and recovery.

5. Conclusion

Our findings suggest cigarette smokers who rarely judge their inner experiences may be more likely to maintain reductions in cigarette smoking after participating in Mindfulness Training rather than a standard CBT-oriented smoking cessation program. Measuring trait FFMQ non-judgment may help to identify those smokers who will benefit most from a mindfulness-oriented approach to treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Author 1: R03DA030899, Mind & Life Varela Award, HMS Dupont-Warren

Author 2: K01DA027097

Author 3: K24DA030443

Author 4: K12DA00167, R03DA029163

Date and Location:

2009-2011: Study conducted in Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

2011-2012: Analysis conducted at MGH Center for Addiction Medicine, Boston, MA

References

- American Lung Association . Freedom from smoking. American Lung Association; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Carmody J, Hunsinger M. Weekly Change in Mindfulness and Perceived Stress in a Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program. J Clin Psychol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jclp.21865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, Williams JM. Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment. 2008;15(3):329–342. doi: 10.1177/1073191107313003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy of substance abuse. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Chawla N, Collins SE, Witkiewitz K, Hsu S, Grow J, Marlatt A. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: a pilot efficacy trial. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):295–305. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Marlatt A. Surfing the urge: brief mindfulness-based intervention for college student smokers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(4):666–671. doi: 10.1037/a0017127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Lutz A, Schaefer HS, Levinson DB, Davidson RJ. Neural correlates of attentional expertise in long-term meditation practitioners. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(27):11483–11488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606552104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Bowen S, Smith JT, Marlatt GA, Potenza MN. Mindfulness-based treatments for co-occurring depression and substance use disorders: what can we learn from the brain? Addiction. 105(10):1698–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Mallik S, Babuscio TA, Nich C, Johnson HE, Deleone CM, Rounsaville BJ. Mindfulness Training for smoking cessation: results from a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119(1-2):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Sinha R, Chen JA, Michalsen RN, Babuscio TA, Nich C, Rounsaville BJ. Mindfulness Training and stress reactivity in substance abuse: results from a randomized, controlled stage I pilot study. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):306–317. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med. 2008;31(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughton DM, Kass I, Fix AJ, Ahrens K, Rennard SI. Smoking intervention: combination therapy using nicotine chewing gum and the American Lung Association's “Freedom from Smoking” manuals. Prev Med. 1986;15(4):432–435. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra A, Conijn B, De Vries H. A match-mismatch test of a stage model of behaviour change in tobacco smoking. Addiction. 2006;101(7):1035–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisendrath S, Chartier M, McLane M. Adapting Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.05.004. In Press, Corrected Proof. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez AC, Wood MD, Stein LA, Rossi JS. Measuring mindfulness and examining its relationship with alcohol use and negative consequences. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;24(4):608–616. doi: 10.1037/a0021742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC JC, Baker TB. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; Rockville, MD: 2008. p. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gastfriend DR, McLellan AT. Treatment matching. Theoretic basis and practical implications. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81(4):945–966. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70557-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P. On measuring mindfulness in psychosomatic and psychological research. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(4):405–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group PMR. Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 1997;58(1):7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks PS, Delucchi KL, Hall SM. Mechanisms of change in extended cognitive behavioral treatment for tobacco dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;109(1-3):114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The empirical status of the “new wave” of cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33(3):701–710. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living. Delta Publishing; New York, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lau MA, Bishop SR, Segal ZV, Buis T, Anderson ND, Carlson L, Devins G. The Toronto Mindfulness Scale: development and validation. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(12):1445–1467. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig DS, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1350–1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin A, Beitel M, Schuman-Olivier Z, Avants SK. A controlled study of a spirituality-focused intervention for increasing motivation for HIV prevention among drug users. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(4):311–322. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin A, Schuman-Olivier Z, Beitel M, Arnold RM, Fulwiler CE, Avants SK. A preliminary study of spiritual self-schema (3-S(+)) therapy for reducing impulsivity in HIV-positive drug users. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(10):979–999. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Donovan DM. Relapse prevention : maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McGovern PG, Lando HA. An assessment of nicotine gum as an adjunct to freedom from smoking cessation clinics. Addict Behav. 1992;17(2):137–147. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90018-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottillo S, Filion KB, Belisle P, Joseph L, Gervais A, O'Loughlin J, Eisenberg MJ. Behavioural interventions for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(6):718–730. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum P, O'Shea R. Large-scale study of freedom from smoking clinics--factors in quitting. Public Health Rep. 1992;107(2):150–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman-Olivier Z, Albanese M, Carlini S, Shaffer HJ. Effects of Trait Mindfulness During Buprenorphine Treatment for Heroin Dependence: A Pilot Study [Poster Abstract from AAAP 21st Annual Meeting]. The American Journal on Addictions. 2011;20:386. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;42(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead LF, Lancaster T. Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(2) 2005:CD001007. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001007.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulaszek WR, Lin HJ, Frisman LK, Sampl S, Godley SH, Steinberg-Gallucci KL, O'Hagan-Lynch M. Development and Initial Validation of a Client-Rated MET-CBT Adherence Measure. Subst Abuse. 2012;6:85–94. doi: 10.4137/SART.S9896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veehof MM, Ten Klooster PM, Taal E, Westerhof GJ, Bohlmeijer ET. Psychometric properties of the Dutch Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(8):1045–1054. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1690-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace HN. Guidelines for treating and controlling tobacco use and dependence. Nova Science Publishers; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Bowen S. Depression, craving, and substance use following a randomized trial of mindfulness-based relapse prevention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 78(3):362–374. doi: 10.1037/a0019172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Hartzler B, Donovan D. Matching motivation enhancement treatment to client motivation: re-examining the Project MATCH motivation matching hypothesis. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1403–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zgierska A, Rabago D, Chawla N, Kushner K, Koehler R, Marlatt A. Mindfulness meditation for substance use disorders: a systematic review. Subst Abus. 2009;30(4):266–294. doi: 10.1080/08897070903250019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]