Abstract

To facilitate the development of an inverse targeting strategy, where anti-topotecan antibodies are administered to prevent systemic toxicity following intraperitoneal topotecan, a pharmacokinetic/toxicodynamic (PK/TD) model was developed and evaluated. The pharmacokinetics of 8C2, a monoclonal anti-topotecan antibody, were assessed following IV and SC administration, and the data were characterized using a two compartmental model with nonlinear absorption and elimination. A hybrid PK model was constructed by combining a PBPK model for topotecan with the two-compartment model for 8C2, and the model was employed to predict the disposition of topotecan, 8C2, and the topotecan-8C2 complex. The model was linked to a toxicodynamic model for topotecan-induced weight-loss, and simulations were conducted to predict the effects of 8C2 on the toxicity of topotecan in mice. Increasing the molar dose ratio of 8C2 to topotecan resulted in a dose-dependent decrease in the unbound (i.e., not bound to 8C2) topotecan exposure in plasma (AUCf) and a decrease in the extent of topotecan-induced weight-loss. Consistent with model predictions, toxicodynamic experiments showed substantial reduction in the percent nadir weight loss observed with 30 mg/kg IP topotecan after co-administration of 8C2 (20±8% vs. 10±8%). The investigation supports the use of anti-topotecan mAb to reduce the systemic toxicity of IP topotecan chemotherapy.

Keywords: Pharmacokinetic/Toxicodynamic model, Monoclonal antibody, Subcutaneous bioavailability, Topotecan, 8C2, Intraperitoneal chemotherapy, Inverse targeting, Surface Plasmon resonance, Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay, Immunotoxicotherapy

1. Introduction

Several high-affinity monoclonal antibodies have been developed and marketed for use in altering the disposition and toxicity of soluble ligands. This application of therapeutic antibodies, which is referred to as immunotoxicotherapy, includes several highly successful marketed drugs (bevacizumab, adalimumab, infliximab, omalizumab, anti-digoxin immune Fab, etc.)(Flanagan and Jones, 2004; Lobo et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008). High-affinity antibodies can drastically alter the time course of ligand exposure, and the rate and extent of these alterations depends on the pharmacokinetic properties of the antibody, the pharmacokinetics of the ligand, the binding kinetics between antibody and ligand, and the dosing protocols employed. In most cases, administration of high affinity antibodies leads to an increased binding of ligand in plasma, redistribution of ligand from tissues to the systemic circulation (Rosenblum et al., 1990), increased total plasma ligand concentrations, reduced ligand concentrations in tissues, and decreased unbound ligand concentrations in plasma (Balthasar and Fung, 1994; Pentel et al., 1991; Terrien et al., 1989; Valentine and Owens, 1996). However, antibodies often impart a “restrictive” effect on the clearance of the ligand, which often leads to increased total cumulative systemic exposure of the ligand (AUC) and increases in the half-life of ligand in plasma.

We are interested in utilizing anti-topotecan antibodies in an “inverse targeting” strategy to enhance the therapeutic selectivity of intraperitoneal topotecan chemotherapy (Chen and Balthasar, 2005; Chen et al., 2007). Specifically, we have proposed that systemic administration of anti-topotecan antibodies could be utilized to produce site-specific alterations in topotecan disposition, increasing the ratio of local (peritoneal) drug exposure relative to systemic drug exposure (Balthasar and Fung, 1994; Balthasar and Fung, 1995, 1996; Lobo and Balthasar, 2005; Lobo et al., 2003). The presence of anti-topotecan antibodies in the systemic circulation would be expected to lead to rapid binding of topotecan upon its absorption from the peritoneum, reducing systemic exposure to unbound drug, limiting the distribution of the drug to sites associated with topotecan toxicities, and, potentially, reducing the magnitude of topotecan-induced systemic toxicity.

Systemic toxicities of chemotherapeutic drugs may be correlated with peak plasma drug concentration (Fogli et al., 2001; Lyass et al., 2000; Nagai et al., 1998), steady-state plasma concentration, cumulative systemic exposure (Jodrell et al., 1992; Zhou et al., 2000), or time above a threshold concentration (Ohtsu et al., 1995). If chemotherapeutic toxicity is related to peak drug concentration, systemic administration of antibodies with high affinity for the chemotherapeutic drug may be expected to decrease peak free drug concentrations and produce favorable reductions in drug toxicities. Indeed, the co-administration of anti-drug antibodies for chemotherapeutic drugs has been generally shown to reduce drug toxicities. For example co-administration of polyclonal anti-doxorubicin antibody preparations increased the survival of mice treated with a toxic doses of doxorubicin (Balsari et al., 1991; Savaraj et al., 1980), and co-administration of a murine monoclonal anti-vinca antibody with toxic doses of vinca alkaloids produced no deaths compared to vinca administration alone, which caused 70% mortality in mice (Gutowski et al., 1995).

However, for many chemotherapeutics, toxicity vs. dose relationships are highly dependent on the time course of drug exposure, where apparent potency of the drug increases with increases in the duration of drug exposure. For example, in clinical studies with topotecan, the maximally tolerated dose of the drug was reduced from 22.5 mg/kg following 30 min infusion to 3.4 mg/kg following 120 h infusion (Rowinsky and Verweij, 1997). As such, binding of the anti-drug antibody with this type of chemotherapeutic drug could potentially increase the half-life of these drugs, leading to an increased duration of drug exposure and, in turn, increased drug toxicities. This risk may be particularly high for cell cycle phase-specific agents, as extending the duration of drug exposure may allow greater fraction of the cells to cycle into a sensitive stage of the cell cycle.

There have been several reports in the literature demonstrating increased cytokine toxicities following administration of neutralizing anti-cytokine antibody administration (Finkelman et al., 1993; May et al., 1993; Sato et al., 1993). There are also similar reports showing reoccurrence of drug toxicities after administration of anti-drug antibodies as a treatment for drug overdose or venom poisoning, which has been related to changes in the time course of drug exposure (Boyer et al., 2001; Seifert and Boyer, 2001). Anti-methotrexate antibodies have been shown to increase or decrease methotrexate toxicity, with results dependent on the nature of the dosing protocol (Lobo et al., 2003). Given the complexities associated with effects of antibodies on ligand disposition, and complexities associated with relationships between the time-course of ligand exposure and toxicity, it is often difficult to predict the effects of anti-drug antibodies.

The a priori prediction of antibody effects on ligand exposure and toxicodynamics is quite challenging; however, prior work has demonstrated that this effort may be facilitated through the use of mechanistic pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic models (Balthasar and Fung, 1994; Lobo et al., 2003). In this report, we have assessed the effect of systemic co-administration of a high affinity anti-topotecan antibody (8C2) on the toxicodynamics of IP topotecan in mice. 8C2 pharmacokinetics were investigated following a wide range of doses, and the data were characterized with a compartmental model. The simple model of 8C2 pharmacokinetics was merged to a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model of topotecan disposition (Shah and Balthasar, 2011) to predict the effects of antibody administration on the time-course of topotecan exposure. The pharmacokinetic model was then linked to a toxicodynamic model (Chen et al., 2007), which allowed prediction of the effects of anti-topotecan antibody administration on the systemic toxicity resulting from IP topotecan therapy. Additionally, two different toxicodynamic experiments were conducted to evaluate the effect of subcutaneous (SC) 8C2 administration on the systemic toxicity of IP topotecan chemotherapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production and purification of 8C2

8C2 hybridoma cells secreting high-affinity anti-topotecan monoclonal antibodies were grown in serum-free medium supplemented with 0.5% gentamicin (Hybridoma SFM, Invitrogen), as described previously (Chen and Balthasar, 2007). Large quantities of antibody-containing medium were produced in 1L spinner flasks kept in a CO2 incubator (Model 2100, VWR, West Chester, PA), which was maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Medium was harvested and centrifuged for 20 minutes at 7,000 rpm, and then filtered with a sterile 0.22 μm cellulose acetate bottle-top filter (Corning) before purification. The 8C2 antibody was purified from culture medium via protein-G affinity chromatography (HiTrap Protein-G, Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) using an automated BioLogic medium pressure chromatography system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) kept into 4°C refrigerator. For purification, the culture medium was loaded onto the column, which was then washed with 20 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.0). Antibody was then eluted using 100 mM glycine buffer (pH 2.8), and collected in tubes prefilled with few drops of Tris buffer (pH 9.0). The purified antibody was pooled, concentrated, and dialyzed against phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Antibody concentrations were assessed by UV absorbance at 280 nm, with the consideration that 1 mg/ml antibody protein corresponds to 1.35 absorption units (AU).

2.2. Synthesis of topotecan-bovine serum albumin conjugate

Topotecan hydrochloride was purchased from Beta Pharma Inc. (New Haven, CT), cationized bovine serum albumin (cBSA) was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL), and 37% formaldehyde solution was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Topotecan was conjugated to cBSA via the Mannich reaction. Briefly, the cBSA powder was dissolved in 200 μl of double distilled water to make a solution of cBSA, 10 mg/mL, in 0.05 M MES (2-[N-morpholino]-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 4.7. Topotecan (~1 mg) was dissolved in 100 μl of 0.05M MES. The topotecan and cBSA solutions were combined, and 50 μl of 37% formaldehyde solution was added to the mixture. The reaction mixture was vortexed, centrifuged, and incubated in a 50 °C water bath for 24h. The reaction mixture was then mixed with an equal volume of phosphate buffer (0.02 M Na2HPO4 with no pH adjustment) and the conjugate was precipitated. The precipitate was collected after centrifugation, and the supernatant was discarded. The bright yellow precipitate was then redissolved in 0.05 M MES, and evaluated by UV analysis at 280 nm (for determination of cBSA concentration) and at 380 nm (for determination of topotecan concentration).

2.3. Development of ELISA for quantification of 8C2 in mouse plasma

An antigen-specific ELISA assay was developed to determine 8C2 concentrations in mouse plasma. 8C2 working standards were prepared by spiking blank mouse plasma with a standard stock solution. Working standards were then diluted 100-fold with PBS to achieve appropriate standard concentrations (0, 50, 250, 750, 1000 and 1500 ng/ml) with 1% mouse plasma (v/v) in the final solution. The precision and accuracy of the ELISA were evaluated by determining the recovery of quality control samples (QCs) of 8C2, prepared in a similar manner to the standard samples. Quality control samples were prepared at low, mid, and high concentrations (100, 500 and 1250 ng/ml) with respect to the standard curve. Standards were prepared immediately prior to use in the assay, and QCs were prepared in bulk, aliquoted, and stored at −20°C. Standards and QCs were run on each microplate, with samples, and a unique standard curve was generated for each assay run.

Briefly, the topotecan-cBSA conjugate solution was diluted 1:333 in 0.05 M MES to obtain the concentration of 4.14 μg/ml. Nunc Maxisorp 96 well plates (Nunc model # 62409-002, VWR, Bridgeport, NJ) were then incubated with the conjugate solution (250 μl/well) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the plates were washed thrice with PB-Tween (0.05% Tween in 0.02 M Na2HPO4, no pH adjustment), followed by one wash with PBS. Plates were then incubated with standards and samples in triplicate (250 μl/well) for 2 h at room temperature. At the end of the incubation, the plates were washed as described above. Next, the plates were incubated with 250 μl of anti-mouse IgG (whole molecule Specific- alkaline phosphatase conjugated) (Sigma, Cat #A5153, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at room temperature (1:500 dilution of the conjugate with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS). The plates were then washed and rinsed, and p-nitro phenyl phosphate solution (Pierce, Rockford, IL, 4 mg/ml in diethanolamine buffer, pH 9.8) was added to each well (250 μl/well). The change in absorbance at 405 nm with time (dA/dt) was monitored with a plate reader (Spectra Max 250, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) for 6 minutes, and standard curves were obtained by fitting the dA/dt vs. 8C2 concentration data to a 4 parameter equation.

2.4. 8C2 pharmacokinetics in mice

Pharmacokinetic investigations of 8C2 after intravenous (IV) or SC administration were carried out with Swiss Webster male mice (20–30 g, 4–5 weeks old, Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN). Protocols for animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University at Buffalo. Mice were housed in a sterile room on a standard light–dark cycle, with continuous access to food and water.

For the study, twenty animals were divided in to four groups of five animals each. Group 1, 2, 3 and 4 were administered with 8C2 at doses of 10 mg/kg IV, 10 mg/kg SC, 164 mg/kg SC and 3.77 g/kg SC. At 1, 2, 6, and 12 hours, and at 1, 2, 5, 9, 14 and 35 days after dosing, 25 μL blood samples were collected from three mice within each dosing group, using a staggered design (i.e., where 3 of the 5 mice per group were sampled at each time-point). Samples were collected from the retro-orbital sinus, using heparinized capillary tubes. In order to separate the plasma, blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 2 min and the plasma fraction was collected and stored at −20°C pending analysis. Plasma samples were analyzed for the concentrations of 8C2 via ELISA. Noncompartmental analysis of data was carried out using WinNonlin (V 5.0), and the SC bioavailability of 8C2 for each dose was calculated using AUClast.

2.5. Mathematical model of 8C2 disposition in mice

Since the range of 8C2 doses studied under the pharmacokinetic study is very wide and includes very high dose levels, it was anticipated that the data would show dose-dependent bioavailability and clearance due to local and systemic saturation of neonatal Fc Receptor (FcRn). As such, a simple pharmacokinetic model capable incorporating nonlinearity in absorption and elimination of 8C2 was developed and evaluated. The schematic diagram of the model is presented in Figure 1. The model consists of a SC compartment and two distribution compartments to characterize the systemic disposition of 8C2. After SC administration of 8C2, the antibody enters the central compartment via a first order rate constant (Ka), with dose dependent bioavailability . Where, SCBA represents the SC bioavailability of 8C2 at low antibody doses, Dose is the SC antibody dose and KF is a bioavailability constant. Once in the central compartment, the antibody is assumed to distribute between the central and peripheral compartments as dictated by the distribution clearance, CLDA. From the central compartment, the antibody is eliminated via a parallel linear clearance pathway and a concentration-dependent clearance pathway. The total antibody clearance is described as: . CL is the clearance of 8C2 at low concentrations (not saturating the salvage FcRn receptors), ECL is the maximum value of antibody clearance in the absence of FcRn, CA1 is the 8C2 concentration in central compartment and KCL is a clearance constant. Equations used to describe the pharmacokinetic model of 8C2 are:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

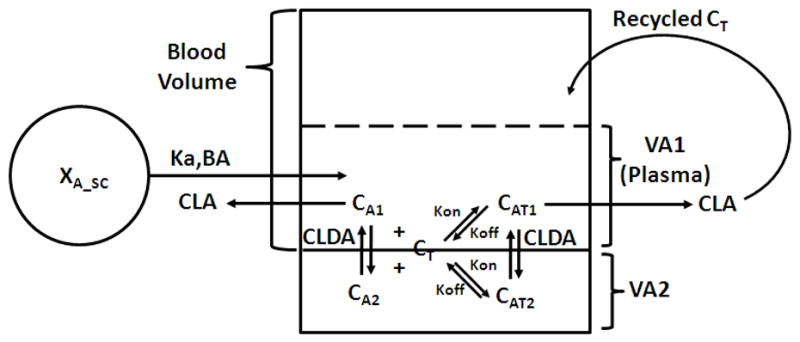

Figure 1. Pharmacokinetic model used to characterize 8C2 disposition in mice.

The model consists of subcutaneous, systemic, and peripheral compartments to characterize the absorption and systemic disposition of 8C2. Concentrations of 8C2 in the central and peripheral compartments are displayed as CA1 and CA2. Volumes of the central and peripheral compartments are VA1 and VA2. XA_SC represents the amount of antibody available at the SC administration site. After SC dosing, 8C2 is assumed to enter the central compartment via a first order process (Ka) with dose dependent bioavailability: . SCBA is the SC bioavailability of 8C2 at low antibody doses, Dose is the SC antibody dose and KF is a bioavailability constant. Once in the central compartment, the antibody is assumed to distribute between the central and peripheral compartment via distribution clearance, CLDA. Antibody is assumed to be eliminated from the central compartment with clearance defined as: . Where CL represents a concentration-independent clearance pathway for 8C2, and ECL represents clearance that is modulated as a function of FcRn saturation, as dictated by CA1/(KCL+CA1). KCL is a clearance constant.

The amount of antibody present in SC compartment is described as XA_SC. The concentration of 8C2 in central and peripheral compartments is displayed as CA1 and CA2. The volume of central and peripheral compartments for 8C2 is displayed as VA1 and VA2.

In order to fit the above described model to the observed 8C2 pharmacokinetic data, the volume of central compartment (VA1) was fixed to the physical volume of plasma in mice, 9.90E-04 L. The parameter SCBA was fixed to the value of 1, and the parameter value of ECL was fixed to the value obtained by subtracting antibody clearance in FcRn knockout mice with antibody clearance in control mice, 6.96E-05 L/h (Garg and Balthasar, 2007). All other parameters (VA2, CL, CLD, Ka, KF and KCL) were estimated by fitting all equations simultaneously to plasma data obtained from all 4 different dose groups. Parameters were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation method of the ADAPT-V program with the variance model:

| (4) |

Y(t) is the model output at a given time t and Var(t) is the variance associated with the output. The variance parameters σIntercept and σSlope represent a linear relationship between the standard deviation of the model output and Y(t).

2.6. Determination of topotecan and 8C2 binding constants using SPR analysis

The SPR studies were conducted using Biacore® T100 system (Biacore Inc., Piscataway, NJ). CM5 Series S Sensor Chips with free carboxyl groups on the sensor surface were used for the immobilization. First the chip surface was activated using 0.4M of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylpropyl)-carboiimide (EDC) and 0.1M N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS). Then the solution containing 8C2 was passed on the activated surface for immobilization using amine coupling chemistry. After immobilization, 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) was passed on the surface to inactivate remaining free binding sites. Topotecan solutions, at a range of concentrations, were passed over the sensor surface for a fixed time to allow for binding between topotecan and 8C2. The data obtained from the experiment, collected as resonance units (RU) vs. time, was then analyzed using the Biacore T100 Evaluation software. Kinetic data were fit using the homogenous ligand model to obtain the association rate constant (Kon) and dissociation rate constant (Koff) values.

2.7. Development of a pharmacokinetic/toxicodynamics (PK/TD) model to predict the dynamic effect of 8C2

In order to investigate the effect of 8C2 on the pharmacokinetics and toxicity of topotecan, a combined PK/TD model was developed. The pharmacokinetic of topotecan was described using a previously published PBPK model of topotecan (Shah and Balthasar, 2011) (Figure 2). 8C2 pharmacokinetics was described with the two compartment model introduced above (Figure 1). The binding interaction between topotecan and 8C2 was assumed to occur throughout the central and peripheral compartments of 8C2, which overlap with the plasma space of the topotecan PBPK model (Figure 3). Unbound topotecan concentrations in plasma were then used as a driving force to predict tissue topotecan concentrations. Antibodies in central and peripheral compartments are assumed to interact with topotecan using the association rate constant Kon and dissociation rate constant Koff. The topotecan-8C2 complex concentrations in the central and peripheral compartment are described as CAT1 and CAT2. The volumes of the central and peripheral compartments for topotecan-8C2 complex are VA1 and VA2. The antibody-topotecan complex is assumed to distribute between the central and peripheral compartment via the distribution clearance, CLDA, and the elimination of the topotecan-8C2 complex from central compartment is described by CLA. Once eliminated as a complex with 8C2, topotecan is assumed to return to the systemic circulation. Equations describing the merged component of the pharmacokinetic model are:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

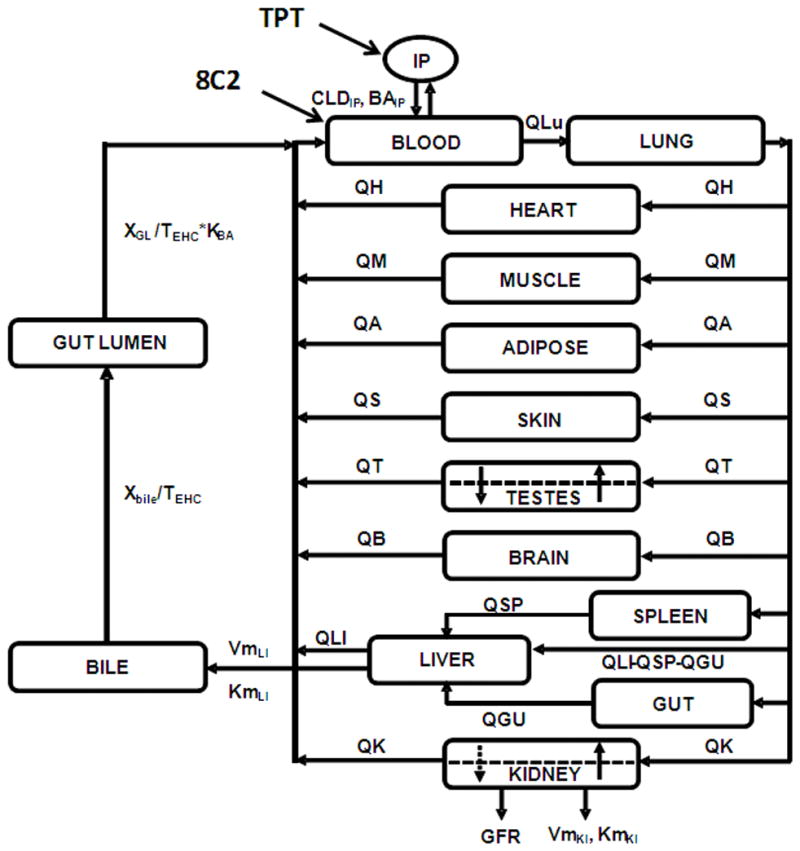

Figure 2. PBPK model for topotecan.

Each tissue is represented by a rectangular compartment, connected in an anatomical manner, with blood flow represented by solid lines. The arrows represent the direction of blood flow. Dashed lines in the testes and kidney compartments represent separation between vascular and extra vascular sub-compartments. For a detailed description of symbols, model structure and equations please refer to reference (Shah and Balthasar, 2011).

Figure 3. Merged component of the hybrid PBPK model used to characterize the pharmacokinetics of topotecan, 8C2, and topotecan-8C2 complexes.

The scheme depicts the interaction between the blood compartment from the topotecan PBPK model and the two disposition compartments from the 8C2 mammillary model. Subcutaneous bioavailability, BA, is dependent on dose: and 8C2 clearance, CLA, is concentration dependent: . For a detailed description of model symbols and equations, please refer to the materials and methods (model development) section of this report.

Equation 9 links the topotecan-8C2 interaction submodel to the topotecan PBPK model. VBlood refers to the volume of blood used for the topotecan PBPK model. QHe, QKi, QLi, QTe, QMu, QSk, QAd and QBr represents blood flow to the heart, kidney, liver, testes, muscle, skin, adipose and brain. Cu_He, Cu_Ki, Cu_Li, Cu_Te, Cu_Mu, Cu_Sk, Cu_Ad and Cu_Br represents unbound concentration in effluent blood from the heart, kidney, liver, testes, muscle, skin, adipose and brain. CLDIP is the distribution clearance of topotecan between blood and peritoneal compartment and CIP is the topotecan concentration in peritoneal compartment. XGL is the amount of drug in gut lumen compartment and TEHC is the transit time for the topotecan in gall bladder and gut lumen compartments. KBA is a bioavailability constant that characterizes the nonlinear bioavailability of topotecan from gut lumen compartment.

The toxicodynamic effect of topotecan is driven by the unbound topotecan concentration in the blood compartment. Topotecan induced toxicity, measured as body weight loss in mice, was characterized using a modified previously published toxicodynamic model, which used indirect response model and a transduction model incorporating 4 transit compartments (Chen et al., 2007). The schematic representation of the model is described in Figure 4. It is assumed that the body weight in mice is governed by three factors: (1) a zero-order rate constant describing the rate of body weight gain (Kin), (2) a first-order rate constant describing the rate of body weight loss (Kout) and (3) a time dependent input function to characterize the baseline body weight in control mice K(t), which is defined as a product of time and a slope constant (m). It is assumed that topotecan inhibits the zero-order rate constant for body weight gain (Kin) through a cascade of biological events. This cascade of events is described through the use of a transduction model with four transit compartments (I1 to I4), and the mean transit time for each compartment is described as Tau. IC50 is the concentration of topotecan that inhibits Kin by 50%. Equations describing the toxicodynamic model are:

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

Figure 4. Toxicodynamic model.

The toxicodynamic effect of topotecan, measured as body weight loss in mice, was driven by the free topotecan concentration in the blood compartment of the topotecan PBPK model. The toxicodynamic model consists of a modified indirect response model and a transduction model incorporating 4 transit compartments. Kin is the zero-order rate constant describing the rate of body weight gain, Kout is the first-order rate constant describing the rate of body weight loss, and K(t) is the time dependent input function to characterize the baseline body weight in control mice. It is assumed that topotecan inhibits the zero-order rate constant for body weight gain (Kin) through a cascade of biological events that are described through the use of a transduction model with four transit compartments (I1 to I4), in each of which the mean transit time of signal is described as Tau. IC50 is the concentration of topotecan that inhibits Kin by 50%.

In above equation BW refers to the mouse body weight.

2.8. Mathematical Simulations

To understand the effect of 8C2 on free topotecan concentrations and on the toxicodynamics of topotecan a series of simulations were performed. The parameter values for the topotecan PBPK model have been reported elsewhere (Shah and Balthasar, 2011), and the parameters for 8C2 pharmacokinetics were obtained from the model fittings described above. The parameters for toxicodynamic portion of the model were obtained by fitting the mean % body weight vs. time data (obtained from literature (Chen et al., 2007)) after control and IP bolus topotecan (doses 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg) administration to the newly developed PK/TD model. Estimated toxicodynamic parameters are listed in Table 1. The resultant PK/TD model and parameters were then used to predict the effect of simultaneous SC administration of 8C2 on the toxicodynamics of IP topotecan. Two different doses of IP topotecan (30 and 40 mg/kg) were used, and for each dose 8C2 was co-administered SC at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 3 and 10 times the molar equivalent dose of topotecan.

Table 1.

Parameter values for the toxicodynamic component of the PK/TD model used for simulating the effect of inverse targeting on toxicity of IP topotecan.

| Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Kin | %/h | 3.63 |

| Kout | 1/h | 0.365E-01 |

| IC50 | nM | 76.6 |

| Tau | H | 26.8 |

| m | 1.01E-03 |

2.9. Toxicity studies

Two separate studies were conducted to assess the effect of co-administration of 8C2 on the toxicity of IP topotecan. Body weight loss was used as the toxicodynamic biomarker. In each investigation, 8C2 was administered by subcutaneous injection, as it was not feasible to administer 8C2 via IV bolus dosing (due to the large doses of topotecan [30 or 40 mg/kg], the intent to administer up to 3 times the mole equivalent dose of antitopoecan antibody [up to 127 mg/animal/injection], and due to the limited solubility of 8C2 [~50 mg/ml]). For the first study, a group of 15 animals was divided into three groups of five mice. On day −2, −1 and 0 the control group, the topotecan group, and the topotecan+8C2 group were injected SC with saline, saline, and 8C2 (65 mg/mouse). On day 0, immediately after the SC injection, the control group, topotecan group and topotecan+8C2 group were injected IP with saline, 40 mg/kg topotecan, and 40 mg/kg topotecan, respectively. For the topotecan+8C2 group, the molar ratio of the 8C2 dose and the topotecan dose was ~1. The body weights of the mice were measured daily up to 13 days. Observations of high mortality in the first experiment led us to conduct the second experiment. In the second experiment, a group of 15 animals was divided in to three groups. On day −2, −1 and 0 the control group, topotecan group, and topotecan+8C2 group were subcutaneously administered with saline, saline, and 8C2 (127 mg/animal). On day 0, immediately after the SC injection, the control group, topotecan group and topotecan+8C2 group were IP administered with saline, 30 mg/kg topotecan, and 30 mg/kg topotecan, respectively. In this study, the treatment group received a mole ratio of 8C2 to topotecan of ~3. The body weights of the mice were measured daily up to 16 days. Mean % body weight vs. time plots were generated for each group, where the % body weight for each animal was calculated based on their body weight on day 0.

3. Results

3.1. Conjugation of topotecan with cBSA

The final concentration of the conjugate in MES buffer was 1.38 mg/ml. UV spectroscopy measurements indicated that, on average, each molecule of cBSA carried 4.1 molecules of topotecan.

3.2. ELISA for quantification of 8C2 in mouse plasma

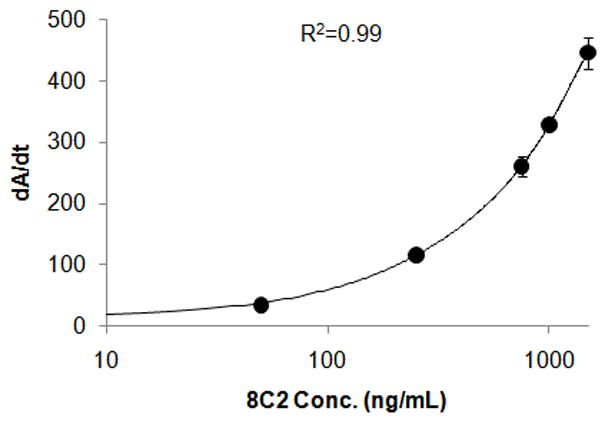

A representative standard curve, obtained by fitting dA/dt vs. 8C2 concentration data with a 4 parameter curve fitting equation, is shown in Figure 5. Correlation coefficients of at least 0.99 were obtained during all assay runs. Inter-assay recovery for quality control samples was 104% (CV% 14.8), 87.9% (CV% 3.6) and 96.5% (CV% 4.3) for 100, 500 and 1250 ng/ml samples. Recovery and CV% were within ±15%. The working range of the assay was 100–1250 ng/ml.

Figure 5. Standard curve for the antigen specific ELISA for 8C2 in mouse plasma.

The standard curve was obtained by fitting the dA/dt vs. 8C2 concentration data with a 4 parameter curve fitting equation. Correlation coefficients of at least 0.99 were obtained during the measurement or validation assays.

3.3. 8C2 pharmacokinetics in Swiss Webster mouse

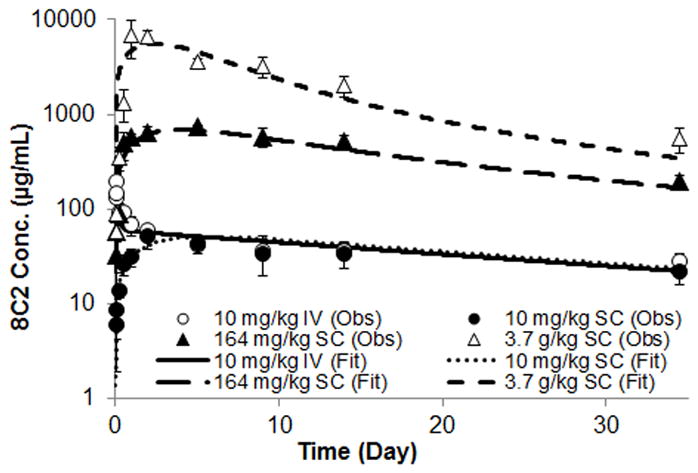

The plasma concentration (μg/ml) vs. time (days) data generated after administration of 8C2 at the dose of 10 mg/kg IV, 10 mg/kg SC, 164 mg/kg SC and 3.77 g/kg SC are described in Figure 6. Plasma concentrations of 8C2 did not increase in a dose-proportional manner. AUClast calculated for 10 mg/kg IV, 10 mg/kg SC, 164 mg/kg SC and 3.77 g/kg SC groups were 1.33E+03, 1.10E+03, 1.56E+04 and 7.67E+04 μg/ml•day, respectively. The bioavailability values for 10 mg/kg SC, 164 mg/kg SC and 3.77 g/kg SC groups, calculated by the dose normalized AUC ratio, were 82, 71 and 15%.

Figure 6. 8C2 pharmacokinetics in Swiss Webster mice.

The figure displays 8C2 concentrations vs. time data observed following the administration of 8C2 at doses of 10 mg/kg IV, 10 mg/kg SC, 164 mg/kg SC and 3.77 g/kg SC. Concentrations were measured by an antigen specific ELSIA method. Symbols represent the mean of 3–5 samples and the error bars represent standard deviations. The figure also displays fitting of the 8C2 data using a compartmental pharmacokinetic model with nonlinear bioavailability and nonlinear clearance. Fittings were performed with the maximum likelihood estimation method in ADAPT V software. The line represents model fits.

3.4. Model fitting of the 8C2 pharmacokinetic data

The pharmacokinetic data were simultaneously fit by the model shown in Figure 1. Model fittings are displayed in Figure 6. Overall, the model was able to capture the profiles very well. Parameters generated by the model fitting are listed in Table 2. Based on the model generated value of KF, the bioavailability calculated for 10 mg/kg SC, 164 mg/kg SC and 3.77 g/kg SC groups were 99.7, 95.6 and 48.6%.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates generated by fitting the 2 compartment mammillary pharmacokinetic model to the experimental 8C2 pharmacokinetics data.

| Parameter | Unit | Estimate | (CV%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VA2 | mL | 3.07 | 10.1 |

| CL | mL/day | 0.107 | 18.2 |

| CLD | mL/day | 5.79 | 21.4 |

| Ka | 1/day | 0.496 | 10.7 |

| KF | mg/kg | 3562 | 49.6 |

| KCL | μg/mL | 5208 | 41.9 |

| VA1 | mL | 0.990 | Fixed |

| SCBA | 1.00 | Fixed | |

| ECL | mL/day | 1.67 | Fixed |

3.5. SPR analysis to determine topotecan-8C2 binding constants

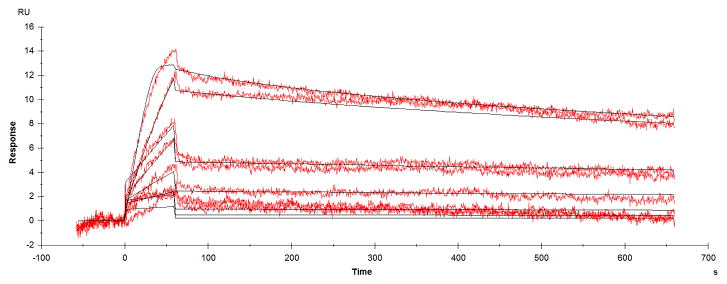

Figure 7 displays the sensogram obtained by passing different concentrations of topotecan over the sensogram chip immobilized with 8C2. The data was fit using the homogenous ligand model in the Biacore T100 Evaluation software to obtain the binding rate constants. SPR analyses indicated that 8C2 bound topotecan with an equilibrium affinity constant (Ka) of 1.98E+09 1/M. The association rate constant (Kon) and the dissociation rate constant (Koff) were found to be 9.27 1/nM/h and 4.68 1/h. The calculated dissociation constant (Kd) is 0.5 nM and the predicted half-time of dissociation is ~10 min.

Figure 7. Topotecan and 8C2 binding sensorgrams.

Binding kinetics for topotecan- 8C2 interaction were determined by surface plasmon resonance. The data obtained from the experiment, as resonance units (RU) vs. time, were analyzed using Biacore T100 Evaluation software. Kinetic data were fit using the homogenous ligand model to obtain the association rate constant (Kon) and dissociation rate constant (Koff) values.

3.6. Simulations using the PK/TD model

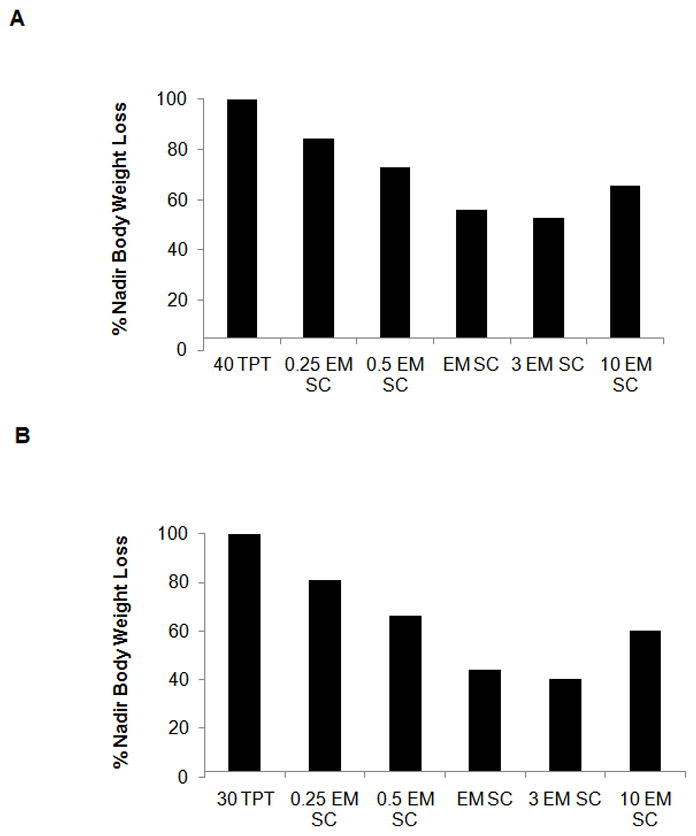

The influence of concomitant systemic administration of 8C2 on unbound topotecan concentrations and topotecan-induced weight-loss were simulated using the PK/TD model. For simulations, topotecan was given either at the dose of 40 mg/kg or at the dose of 30 mg/kg, on day 0. With each topotecan dose, 8C2 was administered SC at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 3 or 10 mole equivalent doses (relative to topotecan). The total antibody dose was administered in three equal, divided doses on day −2, −1 and 0. For each dose combination, unbound topotecan concentrations, the AUC for the unbound topotecan concentrations (AUCf), the ratio of the AUCf with vs. without co-administration of 8C2 (FAUCf), and the % nadir body weight loss was simulated/calculated. With each dose of topotecan, SC 8C2 administration was predicted to decrease AUCf and FAUCf, in a monotonic, dose-dependent manner (data not shown).

Figure 8A and 8B show the %nadir body weight loss data obtained for the 40 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg IP topotecan groups. As shown in the figures, the model predicts a “U-shaped” dose response curve for 8C2, where the antibody effect is optimal at an 8C2:topotecan dose ratio of 3, with lower efficacy predicted at lower and at higher dose ratios. The U-shaped nature of the relationship between 8C2 dose and efficacy relates to the two differing effects of 8C2 on topotecan disposition – the antibody decreases peak unbound topotecan plasma concentrations while also increasing the duration of topotecan exposure. Topotecan toxicity is reduced when unbound drug concentrations are reduced, but increased when the duration of topotecan exposure increases. Of note, at the doses selected for the toxicity studies, the model predicts that 40 mg/kg topotecan will lead to a nadir weight-loss of 14.7%, which is predicted to reduce by 44% to 8.25% with treatment with a mole-equivalent SC dose of 8C2. Following 30 mg/kg topotecan, the model predicts that a mean nadir weight loss of 10.8%, which is predicted to reduce by 59.8% with 8C2 administration.

Figure 8. Simulation results generated by using the PK/TD model.

(A) 40 mg/kg simulations. Bars represent model predictions for % nadir body weight loss for simulated administration of 40 mg/kg topotecan IP (40 TPT), 40 mg/kg topotecan IP + 0.25 molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (0.25 EM SC), 40 mg/kg topotecan IP + 0.5 molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (0.5 EM SC), 40 mg/kg topotecan IP + molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (EM SC), 40 mg/kg topotecan IP + triple the molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (3 EM SC), and 40 mg/kg topotecan IP + 10 times molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (10 EM SC). (B) 30 mg/kg simulations. Bars represent model predictions for % nadir body weight loss for simulated administration of 30 mg/kg topotecan IP (30 TPT), 30 mg/kg topotecan IP + 0.25 molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (0.25 EM SC), 30 mg/kg topotecan IP + 0.5 molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (0.5 EM SC), 30 mg/kg topotecan IP + molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (EM SC), 30 mg/kg topotecan IP + triple the molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (3 EM SC), and 30 mg/kg topotecan IP + 10 times molar equivalent 8C2 given SC in 3 divided doses (10 EM SC).

3.7. Toxicodynamic studies

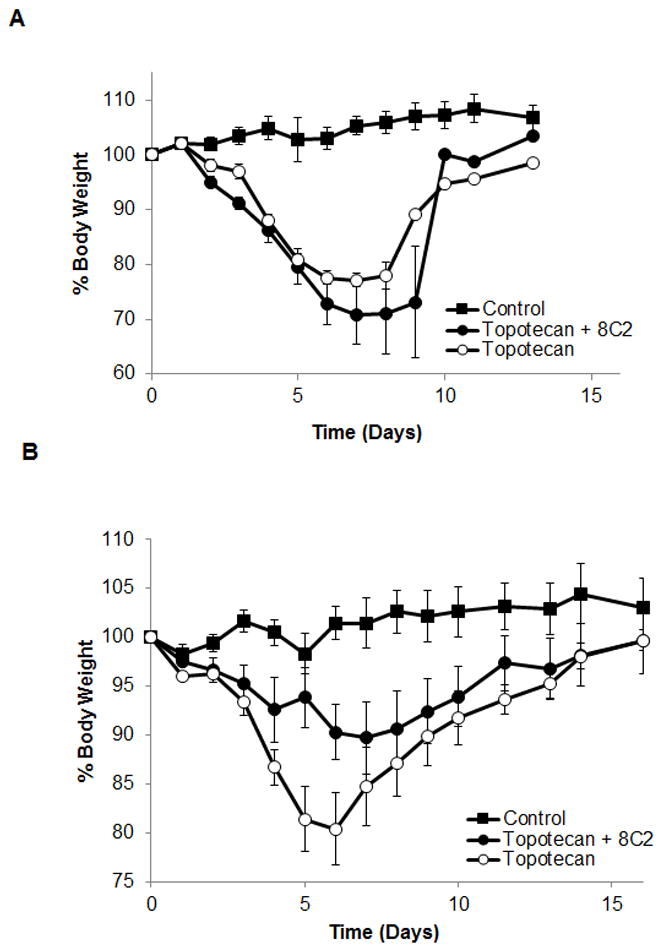

Weight-loss data are presented in Figure 9. Figure 9A shows the %body weight vs. time profiles generated for control, topotecan and topotecan+8C2 groups, where the topotecan dose was 40 mg/kg IP and where 8C2 was administered SC, at dose that was approximately equal to the mole equivalent dose of topotecan. As shown in the figure, the profiles for the topotecan and topotecan+8C2 groups were not much different. Both groups showed severe toxicity that was more than anticipated based on previous studies (Chen et al., 2007). After 216h, only one animal from each treatment group survived. The %nadir weight loss observed for the topotecan and topotecan+8C2 groups were 29±3 and 23±13%. Figure 9B shows the % body weight vs. time profiles generated for control, topotecan, and topotecan+8C2 groups, with an IP topotecan dose of 30 mg/kg, and where the 8C2 dose was ~3 times the mole-equivalent dose (relative to topotecan). No animals died in this study. 8C2 reduced topotecan induced weight loss by 50%, from 20±8 and 10±8% (P=0.1), which is in line with the prediction provided by the PK/TD model (59.8%).

Figure 9. Toxicodynamics.

(A) Average % body weight vs. time data for study 1. On day −2, −1 and 0 the control group (n=5), topotecan group (n=5) and topotecan+8C2 group (n=5) were subcutaneously administered with saline, saline and 65 mg/animal 8C2, respectively. On day 0, the control group, topotecan group and topotecan+8C2 group were IP administered with saline, 40 mg/kg topotecan and 40 mg/kg topotecan, respectively. As such, for topotecan+8C2 group the molar ratio of total SC administered 8C2 dose and IP administered topotecan dose was ~1. The symbols in the graph show average % body weight and the error bar represents standard error. (B) Average % body weight vs. time data for study 2. The study design is similar to that of study 1, except the doses of topotecan and 8C2 were 30 mg/kg and 127 mg/animal, respectively.

4. Discussion

Based on the pharmacokinetic theory developed by Dedrick et al. that suggests that IP drug administration would allow much greater peritoneal drug exposure relative to systemic drug exposure (Dedrick et al., 1978), IP chemotherapy has been widely investigated to improve the selectivity of chemotherapy for the treatment of peritoneal malignancies (e.g. ovarian cancer) (Cintron and Pearl, 1996; Markman et al., 1993; Patel and Benjamin, 2000; Shah et al., 2009; Shah et al., 2011). Although clinical studies support the pharmacokinetic predictions of Dedrick et al., IP chemotherapy has not substantially improved the site-specificity of chemotherapeutic drug cytotoxicity (Gyves et al., 1984; Howell et al., 1984; Kirmani et al., 1994; Pfeiffer et al., 1990; Plaxe et al., 1998; Speyer et al., 1990). Systemic toxicity of IP chemotherapy remains dose-limiting, and only modest improvements in therapeutic benefits have been observed following IP chemotherapy (Alberts et al., 1996).

It has been proposed that the selectivity of IP chemotherapy may be enhanced by the systemic administration of antidotal agents, capable of antagonizing the drug once it diffuses out of the peritoneal cavity (Dedrick et al., 1978). The combination of IP chemotherapy with systemic administration of an antagonist has been investigated with a few drugs. For example: sodium thiosulfate has been applied to reduce the systemic toxicity of IP cisplatin, cysteine has been investigated for utility in reducing the IP mafosfamide toxicity, and tiopronin has been evaluated to minimize toxicity from IP neocarzinostatin (Hasuda et al., 1989; Howell and Taetle, 1980; Wagner et al., 1986). However, either due to slow rates of drug inactivation in vivo (Howell, 1988; Howell et al., 1982), or due to decreased drug efficacy (Wagner et al., 1986), these combinations have found little clinical application in the treatment of peritoneal malignancies. We are interested in an inverse targeting strategy that uses passive immunization with anti-topotecan antibodies as an IV antidote to reduce the toxicity of IP topotecan chemotherapy. It is hypothesized that anti-topotecan antibodies will increase topotecan binding in blood, decrease the cumulative systemic exposure to unbound drug, and minimize the development of systemic toxicity following IP topotecan chemotherapy.

In this report, we have investigated the use of a high affinity anti-topotecan antibody (8C2) in an inverse targeting strategy to decrease the dose limiting systemic toxicity of IP topotecan chemotherapy. The doses of topotecan required to achieve toxicity in mice are relatively high (i.e., up to 40 mg/kg) and, consequently, we anticipated the use of very high doses of 8C2 for systemic neutralization of the chemotherapeutic. High-dose antibody therapy is known to saturate FcRn, which protects IgG antibodies from catabolism (Ghetie and Ward, 1997, 2002; Junghans, 1997; Tabrizi et al., 2006). FcRn is a prime determinant of IgG SC bioavailability and clearance, and saturation of this receptor may be expected to lead to poor bioavailability and relatively rapid systemic clearance of 8C2. To evaluate dose-dependencies in 8C2 pharmacokinetics, 8C2 disposition was evaluated following a wide range of doses (10 mg/kg IV, 10 mg/kg SC, 164 mg/kg SC and 3.77 g/kg SC). As anticipated, 8C2 systemic exposure (AUC) failed to increase in proportion with the 8C2 dose.

In order to decipher the changes in SC bioavailability and clearance of 8C2 at high doses, the pharmacokinetics data were analyzed using a non-linear compartmental pharmacokinetic model, with non-linear absorption and elimination, consistent with concentration-dependent saturation of FcRn (Figure 1). Briefly, the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) is a transport protein that is well-known to protect IgG from intracellular catabolism and pre-systemic catabolism, contributing to the high bioavailability observed following SC administration of monoclonal antibodies. Following the administration of very high doses of 8C2, it is possible that FcRn will become saturated, leading to increased intracellular catabolism and presystemic elimination of the antibody. This phenomenon was incorporated using the following equation: . After fixing the parameter SCBA (SC bioavailability of 8C2 at non-saturating doses) to 1, the equations predict that, at low doses (KF≫Dose), the SC bioavailability of 8C2 would be 1 and at very high doses (Dose≫KF) the SC bioavailability of 8C2 would be 0.

FcRn is also a main determinant of the systemic elimination of IgG from the body. It is believed that high serum IgG concentrations will lead to saturation of FcRn, reducing the fraction of IgG that will is protected from cellular catabolism. This phenomenon was incorporated using the following equation: . Here CL is an estimated parameter that represents the systemic clearance of 8C2 at non-saturating doses. ECL represents the clearance of IgG when all the FcRn receptors are saturated. The value for ECL was fixed to a value obtained by subtracting the value of IgG clearance in FcRn knockout mice with the value of IgG clearance in control mice (Garg and Balthasar, 2007). At low 8C2 concentrations (KCL≫CA1), the total clearance of 8C2 is to be equal to CL, and at very high 8C2 concentrations (CA1≫KCL) the total clearance of 8C2 is equal to CL+ECL. The above mentioned model was able to capture the concentration vs. time profiles for all 4 dose groups of 8C2 quite well (Figure 6) with good precision (Table 2).

After accounting for increase in clearance with increase in 8C2 concentrations via mathematical modeling, the bioavailability values for 10 mg/kg SC, 164 mg/kg SC and 3.77 g/kg SC groups was estimated to be 99.7, 95.6 and 48.6% (calculated based on estimated value of KF and administered doses). This suggests that at the dose of 10 mg/kg the SC bioavailability of 8C2 is close to 100% but increasing the dose to 3.77 g/kg decreases the bioavailability by more than 50%.

Prediction of the interaction of 8C2 and topotecan required structuring the model to allow antibody-drug association and dissociation. Binding kinetics may be incorporated through the use of the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd), with the assumption of rapid (i.e., instantaneous) binding, or through the use of microconstants of association (Kon) and dissociation (Koff). Surface plasmon resonance (SPR), a technology whose kinetic nature enables the detailed study of biomolecular interaction in real time, was used to determine the binding rate constants. In this sensor chip-based analytical system, interactions between two molecules are measured by immobilizing one type of molecule on the surface of a sensor chip and passing a solution containing the other molecule over the surface under controlled conditions. The SPR analysis showed that the 8C2 demonstrates high affinity for topotecan, with a Kd value of 0.5 nM, and a predicted dissociation half-time of ~10 min. Given the slow, non-instantaneous nature of 8C2-topotecan binding, the model was structured to incorporate binding microconstants. Of note, the interaction between topotecan and 8C2 was assumed only in plasma and in the peripheral compartment of the 8C2 model; tissue concentrations of topotecan, as predicted by the PBPK model, were driven (exclusively) by unbound plasma concentrations of the drug. This model structure was assigned based on the expectation that topotecan would be able to rapidly distribute to all sites associated with 8C2 distribution (plasma, interstitial fluids), but that 8C2 would not have access to the primary distribution sites of topotecan in tissue (presumably within intracellular compartments). The topotecan-8C2 complex was cleared from the central compartment, assuming the same rate of clearance as found for unbound 8C2. The model also assumes that topotecan that is eliminated in complex with 8C2 is “recycled” back to the central compartment; this is assumption is based on the expectation that topotecan will be released from 8C2 during the process of 8C2 clearance and catabolism.

The hybrid PBPK model was then linked to a toxicodynamic model to create an integrated PK/TD model to predict the effects of 8C2 on the systemic exposure of topotecan, and on systemic toxicity, following IP topotecan therapy. The toxicodynamic component of the model is illustrated in Figure 4. The model uses the free topotecan concentration in the blood compartment of the PBPK model to drive the toxic effect of topotecan, which is measured as change in body weight. The parameters for the model were derived by fitting a previously published toxicodynamic data for 0, 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg IP topotecan (Chen et al., 2007) to the newly developed PK/TD model.

Simulations with the PK/TD model were performed to investigate the effects of the mole ratio of 8C2 to topotecan on unbound topotecan concentrations, AUC for the unbound topotecan concentrations (AUCf), the ratio of AUCf with vs. without co-administration of 8C2 (FAUCf), and on the extent and time-course of topotecan-induced weight loss. In general there was no difference in the trend of all the simulated/calculated values between the 30 mg/kg and 40 mg/kg doses. Increasing the dose ratio of 8C2 to topotecan (hence the relative concentration of 8C2 in the systemic circulation) resulted in a decrease in topotecan AUCf and, in turn, FAUCf. The predicted decrease in AUCf is due to the nonlinear processes involved in the elimination and reabsorption of topotecan. Antibody administration decreases the unbound topotecan concentrations to levels associated with less saturation in elimination pathways, which then leads to an effective increase in the efficiency of topotecan clearance.

Although the PK/TD model predicts a monotonic relationship between 8C2 dose and AUCf, the model predicts a more complex, “U-shaped” relationship between 8C2 dose and topotecan-induced weight loss. As discussed in the Results Section, the U-shaped nature of the relationship is related to the effect of the antibody on the overall time course of unbound topotecan concentrations. The simulated unbound topotecan concentrations display an initial decline (due to presence of 8C2 in the system); however, redistribution of topotecan from tissue to plasma leads to the appearance of a rebound in unbound drug concentrations. Due to the slow elimination of antibody, and due to the restrictive effect of antibody binding on topotecan clearance, the duration of topotecan exposure is predicted to increase substantially following administration of 8C2. The simulated behavior of topotecan in the presence of 8C2 is quite similar to the observed profile of digoxin disposition following treatment of patients with anti-digoxin Fab (for treatment of digoxin intoxication). Patients often demonstrate a rebound increase in unbound digoxin concentrations, after an initial decrease in unbound digoxin concentrations, which results in the recurrence of digoxin toxicities (Ujhelyi and Robert, 1995; Ujhelyi et al., 1993). Although the model predicts a complex relationship between antibody dosing and effects, the simulations support the use of 8C2 in the proposed inverse targeting strategy to decrease the systemic toxicity of IP topotecan.

Toxicodynamic studies were then conducted to evaluate the effects of 8C2 on topotecan-induced weight loss in mice. In initial work performed with the topotecan dose of 40 mg/kg, we found severe toxicity in all animals (i.e., those treated with or without 8C2), and 4 of 5 animals died in each treatment group. However, following administration of topotecan at 30 mg/kg, animal toxicity was tolerable, and the observed results were much more in line with model predictions. The model predicted that the 8C2 dosing protocol would reduce weight loss by 59.8%, and a 50% reduction in mean percent nadir weight loss was observed (i.e., 20±8% for topotecan alone vs.10±8% for topotecan + 8C2, p = 0.1).

In summary, the present work has evaluated the use of a high-affinity anti-topotecan monoclonal antibody for utility in reducing the systemic toxicity of IP topotecan chemotherapy. To facilitate this effort, an antigen-specific ELISA has been developed and verified, and 8C2 pharmacokinetics were evaluated following a wide range of doses. The antibody demonstrates dose-dependent pharmacokinetics, consistent with decreased bioavailability and increased systemic clearance with increasing doses. Each nonlinearity is conceptually consistent with saturable interactions with FcRn. A new hybrid pharmacokinetic model has been developed to predict and characterize the interaction of topotecan and 8C2, and the predicted unbound topotecan concentrations have been linked to a toxicodynamic model. The model predicts that 8C2 will decrease topotecan AUCf in a monotonic, dose-dependent manner, but the model predicts a complex, “U-shaped” relationship between antibody dosage and effects on topotecan-induced toxicity. Toxicity study results and simulation results suggest that 8C2 may have promise for reducing topotecan toxicity in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Center for Protein Therapeutics at the State University of New York University at Buffalo, and by NIH grant CA118213.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alberts DS, Liu PY, Hannigan EV, O’Toole R, Williams SD, Young JA, Franklin EW, Clarke-Pearson DL, Malviya VK, DuBeshter B. Intraperitoneal cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide versus intravenous cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide for stage III ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1950–1955. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsari A, Menard S, Colnaghi MI, Ghione M. Anti-drug monoclonal antibodies antagonize toxic effect more than anti-tumor activity of doxorubicin. Int J Cancer. 1991;47:889–892. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar J, Fung HL. Utilization of antidrug antibody fragments for the optimization of intraperitoneal drug therapy: studies using digoxin as a model drug. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268:734–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar JP, Fung HL. High-affinity rabbit antibodies directed against methotrexate: production, purification, characterization, and pharmacokinetics in the rat. J Pharm Sci. 1995;84:2–6. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600840103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar JP, Fung HL. Inverse targeting of peritoneal tumors: selective alteration of the disposition of methotrexate through the use of anti-methotrexate antibodies and antibody fragments. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85:1035–1043. doi: 10.1021/js960135w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LV, Seifert SA, Cain JS. Recurrence phenomena after immunoglobulin therapy for snake envenomations: Part 2. Guidelines for clinical management with crotaline Fab antivenom. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:196–201. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.113134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Balthasar JP. High-performance liquid chromatographic assay for the determination of total and free topotecan in the presence and absence of anti-topotecan antibodies in mouse plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2005;816:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Balthasar JP. Development and characterization of high-affinity anti-topotecan IgG and Fab fragments. In: Gad SC, editor. Handbook of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2007. pp. 835–850. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Lu Q, Balthasar JP. Mathematical modeling of topotecan pharmacokinetics and toxicodynamics in mice. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007;34:829–847. doi: 10.1007/s10928-007-9072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintron JR, Pearl RK. Colorectal cancer and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Semin Surg Oncol. 1996;12:267–278. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2388(199607/08)12:4<267::AID-SSU6>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedrick RL, Myers CE, Bungay PM, DeVita VT., Jr Pharmacokinetic rationale for peritoneal drug administration in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Cancer Treat Rep. 1978;62:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelman FD, Madden KB, Morris SC, Holmes JM, Boiani N, Katona IM, Maliszewski CR. Anti-cytokine antibodies as carrier proteins. Prolongation of in vivo effects of exogenous cytokines by injection of cytokine-anti-cytokine antibody complexes. J Immunol. 1993;151:1235–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan RJ, Jones AL. Fab antibody fragments: some applications in clinical toxicology. Drug Saf. 2004;27:1115–1133. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200427140-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogli S, Danesi R, De Braud F, De Pas T, Curigliano G, Giovannetti G, Del Tacca M. Drug distribution and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship of paclitaxel and gemcitabine in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1553–1559. doi: 10.1023/a:1013133415945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg A, Balthasar JP. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model to predict IgG tissue kinetics in wild-type and FcRn-knockout mice. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007;34:687–709. doi: 10.1007/s10928-007-9065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghetie V, Ward ES. FcRn: the MHC class I-related receptor that is more than an IgG transporter. Immunol Today. 1997;18:592–598. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghetie V, Ward ES. Transcytosis and catabolism of antibody. Immunol Res. 2002;25:97–113. doi: 10.1385/IR:25:2:097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutowski MC, Fix DV, Corvalan JR, Johnson DA. Reduction of toxicity of a vinca alkaloid by an anti-vinca alkaloid antibody. Cancer Invest. 1995;13:370–374. doi: 10.3109/07357909509031917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyves JW, Ensminger WD, Stetson P, Niederhuber JE, Meyer M, Walker S, Janis MA, Gilbertson S. Constant intraperitoneal 5-fluorouracil infusion through a totally implanted system. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;35:83–89. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1984.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasuda K, Kobayashi H, Kuroiwa T, Aoki K, Taniguchi S, Baba T. Efficacy of two-route chemotherapy using intraperitoneal neocarzinostatin and its antidote, intravenous tiopronin, for peritoneally disseminated tumors in mice. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1989;80:283–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1989.tb02306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SB. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:1673–1675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.11.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SB, Pfeifle CE, Olshen RA. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy with melphalan. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:14–18. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SB, Pfeifle CL, Wung WE, Olshen RA, Lucas WE, Yon JL, Green M. Intraperitoneal cisplatin with systemic thiosulfate protection. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:845–851. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-6-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell SB, Taetle R. Effect of sodium thiosulfate on cis-dichlorodiammineplatinum(II) toxicity and antitumor activity in L1210 leukemia. Cancer Treat Rep. 1980;64:611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jodrell DI, Egorin MJ, Canetta RM, Langenberg P, Goldbloom EP, Burroughs JN, Goodlow JL, Tan S, Wiltshaw E. Relationships between carboplatin exposure and tumor response and toxicity in patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:520–528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junghans RP. Finally! The Brambell receptor (FcRB). Mediator of transmission of immunity and protection from catabolism for IgG. Immunol Res. 1997;16:29–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02786322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmani S, Braly PS, McClay EF, Saltzstein SL, Plaxe SC, Kim S, Cates C, Howell SB. A comparison of intravenous versus intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the initial treatment of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;54:338–344. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo ED, Balthasar JP. Application of anti-methotrexate Fab fragments for the optimization of intraperitoneal methotrexate therapy in a murine model of peritoneal cancer. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94:1957–1964. doi: 10.1002/jps.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo ED, Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:2645–2668. doi: 10.1002/jps.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo ED, Soda DM, Balthasar JP. Application of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling to predict the kinetic and dynamic effects of anti-methotrexate antibodies in mice. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:1665–1676. doi: 10.1002/jps.10432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyass O, Uziely B, Ben-Yosef R, Tzemach D, Heshing NI, Lotem M, Brufman G, Gabizon A. Correlation of toxicity with pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) in metastatic breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1037–1047. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000901)89:5<1037::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman M, Reichman B, Hakes T, Curtin J, Jones W, Lewis JL, Jr, Barakat R, Rubin S, Mychalczak B, Saigo P, et al. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the management of ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:1565–1570. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820710423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May LT, Neta R, Moldawer LL, Kenney JS, Patel K, Sehgal PB. Antibodies chaperone circulating IL-6. Paradoxical effects of anti-IL-6 “neutralizing” antibodies in vivo. J Immunol. 1993;151:3225–3236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai N, Ogata H, Wada Y, Tsujino D, Someya K, Ohno T, Masuhara K, Tanaka Y, Takahashi H, Nagai H, Kato K, Koshiba Y, Igarashi T, Yokoyama A, Kinameri K, Kato T, Kurita Y. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cisplatin in patients with cancer: analysis with the NONMEM program. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;38:1025–1034. doi: 10.1177/009127009803801107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsu T, Sasaki Y, Tamura T, Miyata Y, Nakanomyo H, Nishiwaki Y, Saijo N. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of paclitaxel: a 3-hour infusion versus a 24-hour infusion. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:599–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR, Benjamin RS. Management of peritoneal and hepatic metastases from gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Surg Oncol. 2000;9:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0960-7404(00)00027-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentel PR, Keyler DE, Brunn GJ, Milavetz JM, Gilbertson DG, Matta SG, Pond SM. Redistribution of tricyclic antidepressants in rats using a drug-specific monoclonal antibody: dose-response relationship. Drug Metab Dispos. 1991;19:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer P, Bennedbaek O, Bertelsen K. Intraperitoneal carboplatin in the treatment of minimal residual ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;36:306–311. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaxe SC, Christen RD, O’Quigley J, Braly PS, Freddo JL, McClay E, Heath D, Howell SB. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of intraperitoneal topotecan. Invest New Drugs. 1998;16:147–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1006045125018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum MG, Murray JL, Stuckey S, Newman RA, Chaney S, Khokhar AR. Modification of methyliminodiacetato-trans-R,R-1,2-diamminocyclohexane platinum(II) pharmacology using a platinum-specific monoclonal antibody. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1990;25:405–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00686050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowinsky EK, Verweij J. Review of phase I clinical studies with topotecan. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:S20-23–S20-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato TA, Widmer MB, Finkelman FD, Madani H, Jacobs CA, Grabstein KH, Maliszewski CR. Recombinant soluble murine IL-4 receptor can inhibit or enhance IgE responses in vivo. J Immunol. 1993;150:2717–2723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaraj N, Allen LM, Sutton C, Troner M. Immunological modification of adriamycin cardiotoxicity. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1980;29:549–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert SA, Boyer LV. Recurrence phenomena after immunoglobulin therapy for snake envenomations: Part 1. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of immunoglobulin antivenoms and related antibodies. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:189–195. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.113135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah DK, Balthasar JP. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for topotecan in mice. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2011;38:121–142. doi: 10.1007/s10928-010-9181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah DK, Shin BS, Veith J, Toth K, Bernacki RJ, Balthasar JP. Use of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody in a pharmacokinetic strategy to increase the efficacy of intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:580–591. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.149443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah DK, Veith J, Bernacki RJ, Balthasar JP. Evaluation of combined bevacizumab and intraperitoneal carboplatin or paclitaxel therapy in a mouse model of ovarian cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speyer JL, Beller U, Colombo N, Sorich J, Wernz JC, Hochster H, Green M, Porges R, Muggia FM, Canetta R, et al. Intraperitoneal carboplatin: favorable results in women with minimal residual ovarian cancer after cisplatin therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1335–1341. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.8.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabrizi MA, Tseng CM, Roskos LK. Elimination mechanisms of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Drug Discov Today. 2006;11:81–88. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03638-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrien N, Urtizberea M, Scherrmann JM. Influence of goat colchicine specific antibodies on murine colchicine disposition. Toxicology. 1989;59:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(89)90153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujhelyi MR, Robert S. Pharmacokinetic aspects of digoxin-specific Fab therapy in the management of digitalis toxicity. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;28:483–493. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199528060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujhelyi MR, Robert S, Cummings DM, Colucci RD, Green PJ, Sailstad J, Vlasses PH, Zarowitz BJ. Influence of digoxin immune Fab therapy and renal dysfunction on the disposition of total and free digoxin. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:273–277. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-4-199308150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JL, Owens SM. Antiphencyclidine monoclonal antibody therapy significantly changes phencyclidine concentrations in brain and other tissues in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:717–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner T, Mittendorff F, Walter E. Intracavitary chemotherapy with activated cyclophosphamides and simultaneous systemic detoxification with protector thiols in Sarcoma 180 ascites tumor. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2214–2219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Wang EQ, Balthasar JP. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:548–558. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Choi L, Lau H, Bruntsch U, Vries EE, Eckhardt G, Oosterom AT, Verweij J, Schran H, Barbet N, Linnartz R, Capdeville R. Population pharmacokinetics/toxicodynamics (PK/TD) relationship of SAM486A in phase I studies in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40:275–283. doi: 10.1177/00912700022008946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]