Abstract

Background

Increasing tobacco taxes to increase price is a proven tobacco control measure. This paper investigates how smokers respond to tax and price increases in their choice of discount brand cigarettes vs. premium brands.

Objective

To estimate how increase in the tax rate can affect smokers’ choice of discount brands versus premium brands.

Methods

Using data from ITC Surveys in Canada and the United States, a logit model was constructed to estimate the probability of choosing discount brand cigarettes in response to its price changes relative to premium brands, controlling for individual-specific demographic and socio-economic characteristics and regional effects. The self-reported price of an individual smoker is used in a random-effects regression model to impute price and to construct the price ratio for discount and premium brands for each smoker, which is used in the logit model.

Findings

An increase in the ratio of price of discount brand cigarettes to the price of premium brands by 0.1 is associated with a decrease in the probability of choosing discount brands by 0.08 in Canada. No significant effect is observed in case of the United States.

Conclusion

The results of the model explain two phenomena: (1) the widened price differential between premium and discount brand cigarettes contributed to the increased share of discount brand cigarettes in Canada in contrast to a relatively steady share in the United States during 2002–2005, and (2) increasing the price ratio of discount brands to premium brands—which occurs with an increase in specific excise tax—may lead to upward shifting from discount to premium brands rather than to downward shifting. These results underscore the significance of studying the effectiveness of tax increases in reducing overall tobacco consumption, particularly for specific excise taxes.

Keywords: cigarette, brand choice, discount brands, tobacco tax

INTRODUCTION

There is widespread recognition of the importance of taxation as one of the most effective measures of tobacco control and its demonstrated value as a public health policy in preventing tobacco-related disease and death.[1–2] A tax increase is expected to raise the retail price of cigarettes and the increased price has proven to cause some smokers to quit, lower the likelihood that non-smokers will begin to smoke, and lower the average consumption of those who continue to smoke.[3]

The taxation of tobacco products, however, may not be as effective in curbing tobacco consumption as it is intended to be, owing to compensatory behavior among smokers to maintain the affordability of tobacco products in response to price increases. The study of compensatory behavior of smokers has appeared in different forms of altered smoking behavior in the literature, such as by smoking cigarettes that are longer and higher in tar and nicotine content,[4] substituting cheaper tobacco products,[5–13] purchasing from low-taxed and untaxed sources of cigarette,[14] or switching to roll-your own or discount brand cigarettes.[14–17] Such compensatory behavior would diminish the expected reduction in cigarette consumption and would, in turn, dampen the impact of any tax induced price increase on public health outcomes. As for example, a study on Chinese smokers confirmed that the intention to quit smoking is lower among smokers who use less expensive cigarettes, implying weaker price sensitivity of smokers.[18]

Using data from the first four waves of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Survey in Canada and the United States during 2002–2005, the present paper examines the brand choice behavior of smokers in these two countries by the classification of cigarettes into discount and premium brands. The objective is to understand how changes in the relative price of these two types of brands can affect smokers’ choice of the lower price option of discount brands. Typically, one would expect smokers to switch downward to discount brand cigarettes in order to compensate for tax and price increase. However, this may not necessarily be the case if the relative price of premium brands falls as a result of the tax and price increase, in which case smokers would be induced to switch upward. This is expected under specific tax system which implies a constant price increase across brands when tax is increased and reduction in the relative price of higher-price brands. The idea of this paper is to test the validity of this hypothesis using data from Canada and the United States.

METHODS

Description of Data

The data used for the analysis comes from the ITC Survey conducted in Canada and the United States, in four annual waves between 2002 and 2005. It is a longitudinal survey conducted by random-digit dialing telephone interviews of more than 2000 representative adult smokers (18 years or older) from each country. The survey questionnaire is uniform across the two countries, permitting use of comparable variables for cross-country analysis. Details of the methods used in the ITC Surveys are presented in Thompson et al.[19]

The data collected on individual smokers include average daily consumption of cigarettes, brand of cigarettes, source and volume of purchase, the prices they paid per unit of purchase (loose or in packs or cartons), use of discount coupons, household income, level of education, age, gender, and region of residence (state, province, etc.). The price per unit of purchase of packs or cartons is converted to price per stick of cigarette by dividing the unit price of purchase by the number of cigarettes contained in each unit. The prices reported in 2002, 2003, and 2004 are adjusted for inflation and converted to 2005 prices for each country using the Consumer Price Index from OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) statistics.

The brand of cigarettes reported by the smokers of factory-made cigarettes is categorized as ‘premium’ and ‘discount’ for the two countries on the basis of manufacturer-specific classification of the cigarettes they market. Much of this information was collected through the documents and advertisements of tobacco companies published on their respective websites. A complete list of these brands is provided in Table 1. The summary statistics of pooled data from four waves of all the variables used for analysis are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

List of premium and discount brands of factory-made cigarettes in Canada and the United States.

| Country | Premium | Discount |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | Accord, American, Avanti, Belmont, Belvedere, Benson & Hedges, Black Cat, Camel, Cameo, Captain Black, Craven A, Craven M, Drum, Du Maurier, Dunhill, Export A, Gauloise, Golden Leaf, Kool, Macdonald, Marlboro, More, Peter Stuyvesant, Player’s, Premium, Rothman’s, Salem, Sportsman, Supreme, Sweet Caporal, Vantage, Viscount, Vogue, Winston | Advantage, Baileys, Bronco, Canadian Classics, Celesta, Colts, Daily Mail, Daker, DK’s, Gipsy, John Players Special (JPS), Legend, Mark Ten, Matinee, Maximum, Medallion, Number 7, Peter Jackson, Podium, Putters, Rockport, Smoking, Smokin’ Joes, Sobranie, Studio, Tabec, Trad A, Tremblay, Unify |

| United States | Accord, American Spirit, Barclay, Belair, Benson & Hedges, Camel, Capri, Carlton, Century, Chesterfield, Commander, Djarum, Dunhill, Eve, Export A, Gitanes, Jade, Kamel, Kent, Kool, L & M, Lark, Lucky Strike, Marlboro, Max, Merit, More, Nat Sherman, Natural American Spirit, Newport, Now, Pall Mall, Parliament, Philip Morris, Players, Quest, Raleigh, Rothman, Salem, Sampoerna, Saratoga, Satin, State Express 555, Tareyton, Triumph, True, Vantage, Virginia Slims, Winston | 1st class, Alpine, Austin, Bailey, Basic, Best Buy, Best Value, Black & White, Bonus Value, Braves, Bridgeport, Bridgeton, Bristol, Bronco, Bronson, Bucks, Buffalo, Calon, Cambridge, Carnival, Century, Chancellor, Champion, Checkers, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Cimarron, Covington and Jasmine, CT, Decade, Desert Sun, Doral, Double Diamonds, Eagle, Epic, Exact, Export, Forsyth, Generic, Gold Coast, GPC, Grand Prix, Gsmoke, GT One, Gunsmoke, Harper, Homer, Kentucky’s Best, Kingsley, Kingsport, Kingston, Legend, Lewiston, Liggett, Mack, Magna, Main Street, Malibu, Marathon, Market, Maverick, Melbourne, Miss Diamond, Misty, Monarch, Mond International, Money, Montclair, Moves, Native, Natural, Natural Blend, New, Niagara’s, Old, Old Gold, Opal, Pall Mall Generic, Parker, Poker, Prime, Primo, Private Stock, Pyramid, Rainbow, Raleigh Extra, Richland, Riviera, Rodeo, Roger, Ropers, Sabre, Seneca, Shield, Silver, Sincerely Yours, Sixty Ones, Skydancer, Smokin Joes, Sonoma, Special, Sport, Sterling, Storm, Summit, Sundance, Tacoma, The Brave, Tracker, Tucson, Unify, US-1, USA, USA Gold, Value Buy, Value Pride, Viceroy, Wave, Westport, Yours |

Sources: Authors’ compilation from web-based sources of tobacco manufacturers.

Table 2.

Summary statistics of sample characteristics in Canada and the United States, 2002–2005.

| Canada | United States | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day | 16.03 | 17.78 |

| Percentage of smokers using discount brand | 26.35 | 27.20 |

| Reported price per cigarette stick of brand used (2005 dollars) | 0.34 | 0.17 |

| Ratio of discount brand price to premium brand price | 0.87 | 0.75 |

| Percentage of smokers who received tobacco industry promotions | 21.17 | 71.34 |

| Percentage of smokers by household income groups | ||

| Below $10,000 | 5.70 | 10.05 |

| $10,000–29,999 | 23.04 | 27.67 |

| $30,000–44,999 | 20.66 | 21.01 |

| $45,000–59,999 | 18.23 | 17.00 |

| $60,000–74,999 | 11.88 | 9.24 |

| $75,000–99,999 | 11.37 | 8.35 |

| $100,000–149,999 | 6.59 | 4.49 |

| $150,000 and over | 2.52 | 2.20 |

| Percentage by highest level of education | ||

| Grade school, some high school | 15.08 | 10.15 |

| Completed high school | 29.56 | 32.35 |

| Technical, trade school, community college | 32.01 | 32.65 |

| Some university -- no degree | 8.74 | 10.03 |

| Completed university degree | 11.43 | 10.66 |

| Post-graduate degree | 3.18 | 4.16 |

| Mean age of smokers (years) | 42.71 | 44.21 |

| Percentage of male smokers | 44.87 | 42.19 |

| Percentage of white smokers | 92.00 | 83.36 |

| Percentage of married/cohabitating smokers | 54.41 | 48.23 |

| Percentage of smokers by year of observation | ||

| 2002 | 31.84 | 32.41 |

| 2003 | 21.00 | 19.04 |

| 2004 | 25.28 | 26.18 |

| 2005 | 21.89 | 22.37 |

| Percentage of smokers by province/region of residence

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Canada | Region | United States |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1.67 | New York | 6.55 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.44 | Pennsylvania | 5.07 |

| Nova Scotia | 3.22 | North-east | 7.31 |

| New Brunswick | 1.88 | Illinois | 3.71 |

| Quebec | 21.05 | Michigan | 3.05 |

| Ontario | 40.95 | Ohio | 4.45 |

| Manitoba | 4.24 | Mid-west | 13.36 |

| Saskatchewan | 3.39 | Florida | 4.85 |

| Alberta | 10.08 | Texas | 5.66 |

| British Columbia | 13.08 | South | 23.57 |

| California | 9.77 | ||

| West | 12.66 | ||

Source: ITC Canada and United States Surveys, 2002–2005.

Cigarette Price and Brand

The average prices per cigarette of premium and discount brands reported by smokers in the ITC Survey over the years under observation are presented in Figures 1 and 2 for Canada and the United States respectively. It appears from Figure 1 that the price gap widened in Canada over time from 4 cents per stick in 2002 to 6 cents per stick in 2005, which resulted in lowering of the price ratio of discount to premium brand cigarettes. The Health Canada statistics of 2006 also show that discount brand cigarettes cost $10 to $20 less per carton or $1.25 to $2.50 per pack, that is, 5–10 cents per stick for 25 stick packs.[20] In contrast, as shown in Figure 2, the prices of discount and premium brand cigarettes in the United States converged over this period.

Figure 1. Average price per cigarette (2005 CAD) by brand of purchase and percentage share of premium and discount brand factory-made cigarette consumption in Canada, 2002–2005.

Source: ITC Canada Survey, 2002–2005.

Figure 2. Average price per cigarette (2005 USD) by brand of purchase and percentage share of premium and discount brand factory-made cigarette consumption in the US, 2002–2005.

Source: ITC USA Survey, 2002–2005.

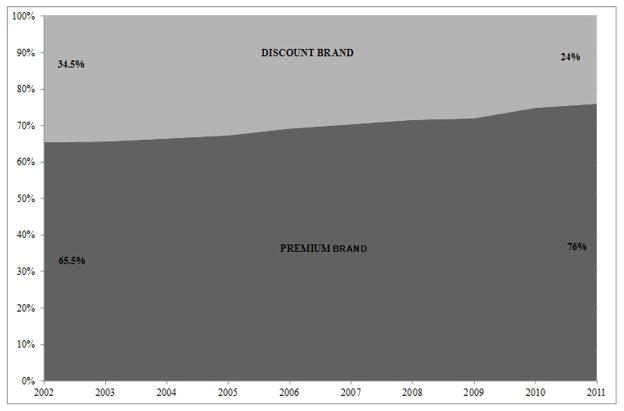

The ITC Survey shows that in Canada, the percentage of discount brand cigarette consumption among factory made cigarettes increased from 17.6% in 2002 to 42.2% in 2005. In contrast, the share of discount brand cigarette consumption in the United States fell from 30.7% in 2002 to 29.8% in 2005. The shares of premium and discount brand consumption by year of observation are presented in the secondary vertical axes in Figures 1 and 2 for Canada and the United States. The upward trend in the market share of discount brand cigarettes in Canada and the downward trend in the United States continued until 2011, as shown in Figures 3 and 4 respectively, based on Euromonitor International Ltd data.

Figure 3. The market share of premium and discount brand cigarettes in Canada, 2002–2011.

Source: Euromonitor International Ltd.

Figure 4. The market share of premium and discount brand cigarettes in the United States, 2002–2011.

Source: Euromonitor International Ltd.

Before 2003, the market for discount brand cigarettes in Canada was occupied by about two dozen small tobacco companies manufacturing at lower production costs and selling cigarettes at cheaper rates than the premium brands marketed by the leading producers. The total market share of discount factory-made cigarettes was 2% in 2001, which went up to 12% in 2002.[21] According to a different source, the share of discount brand cigarettes was somewhat smaller, around 8% by the end of 2002.[22] The growth of the smaller manufacturers of cigarettes was clearly visible in the number of cigarettes produced by the largest of the smaller manufacturers, Grand River Enterprises (GRE), over this period. The production of GRE was 4,500 cases in January 2001, 10,200 cases in January 2002, and 25,600 cases or 250 million cigarettes in January 2003.[21]

In response to the growing market share of the smaller cigarette companies, the major manufacturers in Canada began introducing discount brands. In February 2003, Rothmans, and Benson and Hedges reduced the price of their Number 7 brand cigarettes, which occupied 5.8% of the market share of manufactured cigarettes in that year, by about $1.[23] Imperial and JTI-Macdonald soon developed their own discount brands within 18 months. In total, discount factory-made cigarettes dramatically increased their market share in Canada from 10% in 2003 to 40% in 2005.[24] According to Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey (2005), the percentage of current smokers who purchased discount brands within the six months prior to the survey was 36%.[25]

The US cigarette market experienced this type of dramatic change in the composition of factory-made cigarette market much earlier, in the 1980s and 1990s, with the introduction and spread of discount and deep discount brand cigarettes and the increased use of price-related promotions.[15,26] The market share of discount cigarettes rose from almost none in early 1980s to about 40% in early 1993, and then went down to 27% in 1997.[27] As the ITC data shows, this share did not exceed 30% until 2005.

The period of observation in the present study from 2002 to 2005 coincided with the implementation of several statutes complementary to the provisions of the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) in the United States in response to growth in the market share of manufacturers not participating in the MSA (NPM). Despite provisions in the MSA keeping NPMs from having a significant cost advantage, loopholes in the MSA and non-compliance by NPMs gave them a cost advantage over participating firms, keeping their prices well below those of participating manufacturers. The better enforcement of the MSA regulations using complementary legislations prevented the non-compliance of NPMs to a great extent, a trend that helped the price gap between premium and discount brand cigarettes stabilize in the early 2000s.[27] However, the market share of cigarettes made a marked shift from discount to premium brands later in the decade, which is more likely an outcome of the largest federal cigarette tax increase that occurred in April 2009.

The rise in discount brand cigarettes market share in Canada was accompanied by a large-scale migration of smokers from premium brand to discount brand use. This is evident in the joint distribution of smokers by brand of last purchase of cigarettes in two successive waves of ITC Survey reported in Table 3. Among smokers who reported to have purchased premium brand cigarettes in 2002, 5.3% switched to discount brands in 2003, 21.7% by 2004 and 28.2% by 2005. Similarly, among smokers who bought premium brand cigarettes in 2003, we found that 20% switched to discount brands in 2004 and 26.6% by 2005. Between 2004 and 2005, 10.9% smokers switched from premium to discount brands. These results suggest that the spike in the rise of discount brand cigarette use occurred during 2003 to 2005. In the United States, the percentage of smokers switching from premium to discount brands was steady at 3–5% and was no more prevalent than the percentage switching from discount to premium brands.

Table 3.

Percentage of smokers by brands of cigarettes purchased in two consecutive waves in Canada and the United States, 2002–2005.

| Brand of cigarette purchased in | Canada | United States | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2003 | 2003 | ||||

| Premium | Discount | Total | Premium | Discount | Total | |

| Premium | 75.8 | 5.3 | 81.1 | 62.2 | 4.3 | 66.5 |

| Discount | 3.1 | 15.8 | 18.9 | 3.8 | 29.7 | 33.5 |

| Total | 78.9 | 21.1 | 100.0 | 66.0 | 34.0 | 100.0 |

| 2002 | 2004 | 2004 | ||||

| Premium | Discount | Total | Premium | Discount | Total | |

| Premium | 56.9 | 21.7 | 78.6 | 59.4 | 5.2 | 64.6 |

| Discount | 2.5 | 18.9 | 21.4 | 4.7 | 30.6 | 35.3 |

| Total | 59.5 | 40.5 | 100.0 | 64.1 | 35.9 | 100.0 |

| 2002 | 2005 | 2005 | ||||

| Premium | Discount | Total | Premium | Discount | Total | |

| Premium | 52.9 | 28.2 | 81.1 | 62.0 | 5.1 | 67.1 |

| Discount | 2.1 | 16.8 | 18.9 | 5.4 | 27.6 | 32.9 |

| Total | 55.0 | 45.0 | 100.0 | 67.4 | 32.6 | 100.0 |

| 2003 | 2004 | 2004 | ||||

| Premium | Discount | Total | Premium | Discount | Total | |

| Premium | 59.0 | 20.0 | 79.0 | 60.8 | 3.3 | 64.1 |

| Discount | 2.3 | 18.7 | 21.0 | 2.9 | 33.0 | 35.9 |

| Total | 61.3 | 38.7 | 100.0 | 63.7 | 36.3 | 100.0 |

| 2003 | 2005 | 2005 | ||||

| Premium | Discount | Total | Premium | Discount | Total | |

| Premium | 54.2 | 26.6 | 80.8 | 63.2 | 4.4 | 67.6 |

| Discount | 2.8 | 16.4 | 19.2 | 3.2 | 29.2 | 32.4 |

| Total | 57.0 | 43.0 | 100.0 | 66.4 | 33.6 | 100.0 |

| 2004 | 2005 | 2005 | ||||

| Premium | Discount | Total | Premium | Discount | Total | |

| Premium | 52.4 | 10.9 | 63.3 | 62.2 | 3.3 | 65.5 |

| Discount | 5.5 | 31.2 | 36.7 | 4.8 | 29.7 | 34.5 |

| Total | 57.9 | 42.1 | 100.0 | 67.0 | 33.0 | 100.0 |

Note: The percentages are weighted by the average daily cigarette consumption of individuals in the two waves under consideration and are adjusted for cluster survey design by province (Canada) or state (United States).

Source: ITC Canada and United States Surveys, 2002–2005

Model of Choice of Cigarette Brand

After an individual decides to smoke, s/he decides on the brand of cigarettes to use. This choice depends on the relative price of brands as well as the demographic and socio-economic characteristics of individual smokers that set individual preference for higher or lower price products and product quality. Individuals may also respond to sales promotions offered by tobacco manufacturers as incentive to purchase certain brands. Individual preference for a particular type of brand may shift over time for reasons such as fashion, the entry of a new brand in the market, increase in market concentration and the like. For a random draw of individual i observed in year t, we can write the following logit equation corresponding to the decision to choose cigarette brands:

| (1) |

Here B takes the value of 1 if a smoker smokes discount brand cigarette and 0 if s/he smokes premium brand; X is a vector of observable explanatory variables; β is the vector of parameters corresponding to the regressors X; and e represents the random unobservable influences on the choice of brands. We can rewrite equation (1) in regression form of the log of the odds ratio of choosing discount brands to choosing premium brands as follows:

| (2) |

In the estimation of equation (2), we do not control for individual-specific fixed effects because the real price variable individuals face within a short period of time does not vary much for a specific person. This makes the fixed effect estimate of the effect of price on the choice of brand statistically insignificant. However, we adjust the standard errors of estimates for individual-level correlation of error terms by using multiple observations on individuals as clusters.

In equation (2), we are particularly interested in the marginal effect of the change in the relative price of discount and premium brands on the choice of brands. It is expected that if the relative price of discount brand gets higher, the probability of smoking discount brand cigarettes will be lowered. Conditional on smoking participation, it implies greater probability of smoking premium brand cigarettes, that is, upward trading to premium brands.

In calculating the price ratio, the self-reported price of one’s own brand and the imputed price of the alternative brand that one does not smoke can be used. For example, in case of a discount brand user, the price of premium brand is imputed using information of premium brand smokers; and for a premium brand smoker, the price of discount brand is imputed using information of discount brand smokers. The prices of discount and premium brands are imputed using the following linear regression separately for the discount and premium brand smokers:

| (3) |

where P is the self-reported price per pack of cigarette purchased; X is the same set of explanatory variables as in equations (1–2), RES represents the categorical variables indicating the region of residence of smokers; a represents the individual specific random error component in self-reported price that is uncorrelated with other observable characteristics of individuals; u stands for the random unobserved disturbances in the determination of price.

In equation (3), the random effect a controls for the reporting error that may arise from various sources (e.g., from recall bias). It is assumed that the reporting bias remains constant over time, that is, individuals who understate (overstate) the price they paid systematically understate (overstate) price in repeated observations over time. In order to eliminate the reporting bias, the price ratio is constructed by using prices of used brand and alternative brand predicted from equation (3). Thus we estimate two versions of the choice of brand equation (2)—one with the price ratio constructed from self-reported price of used brand and the predicted price of the alternative brand; the other with the price ratio constructed from the predicted prices of both used and alternative brands. More formally, the first measure of price ratio is given by the following:

Price ratio (discount brand user) = Self-reported price of discount brand/Imputed price of premium brand;

Price ratio (premium brand user) = Imputed price of discount brand/Self-reported price of premium brand.

The second measure of price ratio is given by the following:

Price ratio (discount brand user) = Imputed price of discount brand/Imputed price of premium brand;

Price ratio (premium brand user) = Imputed price of discount brand/Imputed price of premium brand.

It should be pointed out here that both the choice of brand and the self-reported price may be driven by a third variable, which is the quality of cigarettes. Failing to control for this unobservable factor may introduce endogeneity in the relative price variable and bias the estimated coefficient. The second measure of the price ratio based on the predicted prices of both used and alternative brands addresses this possible endogeneity bias.

RESULTS

Cigarette Prices

The price equation (2) is estimated for premium and discount brand cigarettes using the random effects method. The results for Canada and the United States are compared in Table 4. The price ratio estimated by dividing the price of discount brands by the price of premium brands, both predicted from the estimated price equations presented in Table 4, ranges from 0.73 to 1.06 with a mean of 0.88 for Canada. For the United States, this ratio varies from 0.45 to 1.03 with a mean of 0.74.

Table 4.

Random effects estimation of price equation for premium and discount brand cigarettes in Canada and the United States, 2002–2005.

| Canada

|

United States

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premium | Discount | Premium | Discount | ||

| Household income | |||||

| • $10,000–29,999 | 0.00264 (0.70) | 0.0105 (1.51) | −0.00385 (−1.23) | 0.00378 (1.22) | |

| • $30,000–44,999 | 0.00351 (0.91) | 0.0131 (1.85) | −0.00257 (−0.79) | 0.00706* (1.98) | |

| • $45,000–59,999 | 0.00410 (1.02) | 0.00662 (0.80) | 0.000209 (0.06) | 0.00471 (1.19) | |

| • $60,000–74,999 | 0.00552 (1.32) | 0.0124 (1.61) | 0.00325 (0.88) | 0.0109* (2.08) | |

| • $75,000–99,999 | 0.00712 (1.76) | 0.00639 (0.77) | −0.00147 (−0.39) | 0.0108* (2.02) | |

| • $100,000–149,999 | 0.00407 (0.89) | 0.0172* (2.01) | −0.000613 (−0.14) | 0.0128 (1.55) | |

| • $150,000 and over | 0.00291 (0.41) | 0.0370** (2.60) | 0.00601 (0.97) | −0.0210 (−1.33) | |

| Highest level of education | |||||

| • Completed high school | 0.000208 (0.08) | 0.00811 (1.73) | 0.00487 (1.81) | −0.00337 (−0.80) | |

| • Technical, trade school, community college | 0.000273 (0.11) | 0.00798 (1.63) | 0.00544* (1.96) | −0.00273 (−0.66) | |

| • Some university -- no degree | 0.00555 (1.74) | 0.0128 (1.80) | 0.00379 (1.15) | −0.000587 (−0.11) | |

| • Completed university degree | 0.00551 (1.62) | 0.0152** (2.69) | 0.00576 (1.70) | −0.00568 (−0.93) | |

| • Post-graduate degree | 0.0109** (2.64) | 0.0179 (1.46) | 0.0166*** (3.58) | 0.000354 (0.04) | |

| Age | −0.000562*** (−9.38) | −0.000347** (−3.00) | −0.000464*** (−8.27) | −0.000360*** (−4.15) | |

| Male | 0.00279 (1.68) | −0.000860 (−0.28) | 0.000724 (0.46) | −0.00130 (−0.54) | |

| White, English only | 0.00808* (2.30) | 0.00898 (0.98) | −0.0185*** (−8.92) | −0.0160*** (−4.17) | |

| Married, cohabitating | −0.00408* (−2.36) | −0.00212 (−0.65) | −0.00631*** (−3.93) | −0.00119 (−0.48) | |

| Received tobacco industry promotions | −0.00469** (−2.64) | −0.00425 (−1.89) | −0.00668*** (−4.54) | 0.000586 (0.34) | |

| Year 2003 | 0.00776*** (6.02) | −0.0000475 (−0.02) | −0.0116*** (−8.22) | −0.00705*** (−4.60) | |

| Year 2004 | 0.0222*** (13.14) | −0.0109*** (−3.57) | −0.0142*** (−8.99) | −0.00630** (−3.20) | |

| Year 2005 | 0.0221*** (11.10) | −0.0142*** (−4.27) | −0.00937*** (−5.10) | 0.000726 (0.34) | |

| Fixed effects for province (Canada)/region (United States) of residence | |||||

| Prince Edward Island/Pennsylvania | −0.00745 (−0.79) | 0.00794 (0.63) | −0.0380*** (−6.40) | 0.00554 (0.47) | |

| Nova Scotia/North-East | −0.0275*** (−4.07) | −0.0243** (−2.63) | −0.00195 (−0.31) | 0.0236 (1.83) | |

| New Brunswick/Illinois | −0.0532*** (−6.35) | −0.0466*** (−4.80) | −0.0349*** (−5.17) | −0.00497 (−0.37) | |

| Quebec/Michigan | −0.0937*** (−17.32) | −0.110*** (−13.79) | −0.0182** (−2.73) | 0.0398** (3.01) | |

| Ontario/Ohio | −0.0876*** (−16.54) | −0.0936*** (−11.70) | −0.0580*** (−9.72) | −0.0220* (−1.97) | |

| Manitoba/Mid-west | 0.00381 (0.59) | 0.0188 (1.76) | −0.0650*** (−11.80) | −0.0243* (−2.30) | |

| Saskatchewan/Florida | 0.00780 (0.97) | −0.00578 (−0.51) | −0.0726*** (−12.53) | −0.0418*** (−3.84) | |

| Alberta/Texas | −0.00950 (−1.66) | −0.0247** (−2.79) | −0.0698*** (−11.73) | −0.0366*** (−3.41) | |

| British Columbia/South | −0.0143* (−2.49) | −0.00880 (−1.04) | −0.0805*** (−14.80) | −0.0405*** (−3.89) | |

| /California | −0.0345*** (−6.07) | −0.00171 (−0.16) | |||

| /West | −0.0451*** (−7.65) | −0.00425 (−0.39) | |||

|

| |||||

| Observations | 4387 | 1575 | 4575 | 1730 | |

Notes:

The omitted categories include single non-white, non-English female smokers with highest level of education below high school, household income under $10,000, who did not receive any tobacco industry promotion, in year 2002, who resided in Newfoundland and Labrador in case of Canada and in New York region in case of the United States.

The estimated coefficients represent marginal effects for small change in continuous variables and for discrete change of categorical variables from 0 to 1 with reference to the omitted categories.

t statistics are reported in parentheses below the coefficient estimates.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

Choice of Cigarette Brands

The probability of a smoker choosing a discount or a premium brand cigarette is significantly influenced by the price of discount brand cigarettes relative to premium brands as shown in Model 1 in Table 5 for Canada and the United States. When the self-reported price of used brand is replaced with the predicted price in constructing the price ratio (Model 2), the estimate shows negative effect of the ratio of discount to premium brand prices on the probability of choosing discount brands with a larger magnitude in Canada. The larger size of the estimate obtained from Model 2 compared to Model 1 is likely driven by the correction of the endogeneity bias from using self-reported variable of used brand as in Model 1. This coefficient, however, is not statistically significant in case of the United States.

Table 5.

Marginal effects from the logit model of probability of using discount brand cigarettes in Canada and the United States, 2002–2005.

| Dependent variable: Uses discount brand cigarettes =1 premium brand cigarettes=0 |

Canada | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Ratio of discount brand to premium brand price (self-reported price of used brand) | −0.180*** (−3.42) | −0.202*** (−5.48) | ||

| Ratio of discount brand to premium brand price (imputed price of used brand) | −0.782** (−3.08) | −0.308 (−1.83) | ||

| Household income | ||||

| $10,000–29,999 | 0.0105 (0.27) | 0.00802 (0.21) | −0.0625* (−2.51) | −0.0673** (−2.66) |

| $30,000–44,999 | −0.0482 (−1.37) | −0.0518 (−1.45) | −0.0831** (−3.24) | −0.0887*** (−3.38) |

| $45,000–59,999 | −0.0573 (−1.62) | −0.0751* (−2.19) | −0.140*** (−6.54) | −0.140*** (−6.43) |

| $60,000–74,999 | −0.0490 (−1.28) | −0.0521 (−1.35) | −0.134*** (−6.33) | −0.139*** (−6.40) |

| $75,000–99,999 | −0.101** (−3.14) | −0.113*** (−3.58) | −0.186*** (−11.24) | −0.190*** (−11.24) |

| $100,000–149,999 | −0.103** (−2.84) | −0.0999** (−2.64) | −0.185*** (−11.02) | −0.193*** (−11.40) |

| $150,000 and over | −0.0906 (−1.94) | −0.0785 (−1.47) | −0.192*** (−11.36) | −0.199*** (−11.41) |

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Completed high school | 0.0149 (0.57) | 0.0327 (1.20) | −0.00197 (−0.07) | −0.0157 (−0.57) |

| Technical, trade school, community college | −0.0173 (−0.72) | 0.0000735 (0.00) | 0.0320 (1.14) | 0.0163 (0.57) |

| Some university -- no degree | −0.0711* (−2.47) | −0.0530 (−1.68) | 0.0204 (0.56) | 0.0161 (0.46) |

| Completed university Degree | −0.0410 (−1.43) | −0.0252 (−0.81) | −0.0728** (−2.66) | −0.0888*** (−3.32) |

| Post-graduate degree | −0.0991** (−2.84) | −0.0702 (−1.75) | −0.0816* (−2.39) | −0.0857* (−2.45) |

| Age | 0.00277*** (4.72) | 0.00296*** (5.08) | 0.00608*** (11.19) | 0.00627*** (11.83) |

| Male | −0.0749*** (−4.43) | −0.0818*** (−4.91) | −0.0423* (−2.52) | −0.0457** (−2.79) |

| White, English only | 0.114*** (5.02) | 0.108*** (4.83) | 0.108*** (5.57) | 0.107*** (5.63) |

| Married, cohabitating | 0.0361* (2.06) | 0.0496** (2.86) | 0.0574*** (3.33) | 0.0599*** (3.39) |

| Received tobacco industry promotions | 0.164*** (8.58) | 0.163*** (8.82) | −0.0200 (−1.30) | −0.0250 (−1.58) |

| Year 2003 | 0.0166 (1.13) | 0.00589 (0.40) | 0.0183 (1.58) | 0.0191 (1.69) |

| Year 2004 | 0.185*** (9.99) | 0.121*** (3.94) | 0.0331* (2.17) | 0.0333* (2.18) |

| Year 2005 | 0.232*** (10.13) | 0.164*** (4.65) | −0.0263 (−1.47) | −0.0225 (−1.26) |

|

| ||||

| Observations | 5962 | 6497 | 6307 | 6898 |

Notes:

The omitted categories include single, non-white, non-English female smokers with highest level of education below high school, household income under $10,000, those who did not receive tobacco industry promotions, and observations in year 2002.

The estimated coefficients represent marginal effects for small change in continuous variables and for discrete change of categorical variables from 0 to 1 with reference to the omitted categories.

t statistics are reported in parentheses below the coefficient estimates.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

To understand what the magnitude of the estimated coefficient of the price ratio indicates, suppose the initial price per pack of premium brand cigarette is $7 and the initial price per pack of discount brand is $6, so that the ratio of the discount brand price to premium brand price is 0.857 (=6/7). If the specific tax per pack increases by $1 and the tax is fully shifted to consumer so that the new prices are $8 per pack for premium brands and $7 per pack for discount brands, the price ratio increases to 0.875 (=7/8). Given the coefficient of the price ratio for Canada at −0.782, the effect of the increase in the price ratio from 0.857 to 0.875 would be −0.782 × (0.875−0.857) = −0.014. It means that a $1 increase in specific excise can reduce the probability of using discount brand cigarettes by 1.4%, as discount brand smokers switch to premium brands.

The negative sign of the effect of changes in the price ratio of discount to premium brand cigarettes on the probability of choosing discount brand cigarettes implies that as excise tax increases uniformly across all brands, the percentage gap between premium and discount brand prices narrows. As a result, the relative gain from buying discount brand cigarettes shrinks creating incentive to choose premium brands over discount brands. This finding conforms to the evidence from a recent report published by UBS Investment Research that increasing state excise tax rates in the United States resulted in shift in the market share towards premium brands due to narrowing of the price gaps.[28] According to this report, the average cigarette price gap between premium and discount brands is highest and the market share of premium brand cigarettes is lowest in the states with the lowest excise tax per pack. The average price gap is 52% for tax rates below $0.50, 46% for $0.51–$1.00, 37% for $1.01–$1.50 and 27% for above $1.50, while the corresponding market shares of premium brands are 80%, 85%, 85% and 94%.

DISCUSSION

Using data from the first four waves of the ITC Surveys in Canada and the United States between 2002 and 2005, this paper examines the role of the price of discount brand cigarettes relative to the price of premium brand cigarettes in the choice of discount brand cigarettes by smokers. We find that a lower ratio of discount brand price to premium brand price tends to increase the likelihood of smoking discount brand cigarettes. This result confirms that the widened price differential between premium and discount brand cigarettes was a major cause of an increased share of discount brand cigarette consumption in Canada in contrast to a relatively steady share in the United States during the period under observation (2002–2005). As smokers who switch to discount brands are less likely to quit,[15] one can expect that a change in the relative price of cigarette brands in favor of the use of discount brand cigarettes would lead to lower quit rates and greater smoking prevalence. Supporting policy measures are needed to curb the expansion of the discount brand market by controlling the underlying price cutting strategy of cigarette manufacturers as has happened in Canada accompanying the tax and price increases in the 2000s.

This result also implies that increasing the price of discount brands relative to the price of premium brands induces smokers to trade up to premium brands, as standard economic theory would suggest that choices are made based on relative prices. This finding stands in contrast with the conventional wisdom about the compensatory behavior of smokers that higher tax and price would induce smokers to switch to discount brands as a price-minimizing strategy.[2–10] In countries, such as the United States and Canada, where taxes are specific and the same per unit tax applies to all brands, a given increase in the tax and a full pass through of the tax increase to price would raise the price of discount brands relative to premium brands. The estimated model of choice of brand predicts that this would reduce the smoking of discount brand cigarettes and create an incentive to switch from discount to premium brands. Indeed this has been the case in the United States where specific tax increases reduced the market share of generic (lower-priced) brands significantly in the 1980 and 1990s.[29] Upward switching has not previously been seen as a possible response to higher prices, but the present model shows that upward switching naturally follows from the consideration of the change in the price ratio rather than change in average price, and that this phenomenon would be expected to occur under specific tax regimes rather than under ad valorem tax regimes, where an increase in base price does not change the price ratio.

One data limitation of the analysis undertaken in this paper is that the smokers of premium brands do not report the market price they face for discount brands and vice versa. This has led us to estimate a price equation to impute the unobservable price and then use it for the estimation of the relative price of discount to premium brand cigarettes. The ability to control for the price of discount brands for premium brand smokers and the price of premium brands for discount brand smokers depends critically on a well-specified equation imputing price. Besides, the estimated coefficient of the relative price variable differs remarkably between the two approaches we take for estimating the price ratio. For Canada, the estimate is −0.18 when we use self-reported price of used brand in contrast to −0.782 when we use imputed price of used brand along with imputed price of the alternative brand. In case of the United States, the estimate is −0.202 when we use self-reported price of used brand, while it becomes −0.308 and statistically insignificant when imputed price of the used brand is used. Thus the results appear to be sensitive to the use of self-reported or imputed price of the used brand in the construction of the relative price.

The second limitation is that the data available for the brand used by a smoker refers to the one they smoke more than any other. The identification of a single brand used by a smoker may not reflect the true preference pattern of a smoker if the smoker frequently switches between premium and discount brands.

Finally, the choice of the period from 2002 to 2005 is critical for the finding of the study because this is the period when Canada experienced a remarkable shift in the discount brand market share, while the US market stabilized following better enforcement of the MSA. After 2005, the shifts are not going to be as dramatic. This created a perfect experimental situation for us to test our hypothesis.

CONCLUSION

The present paper underlines the significance of studying the effectiveness of tax increases in reducing overall tobacco consumption, keeping in view the effect of tax and price increase on the brand choice behavior of smokers. Under a tax system comprised entirely of uniform specific tax, a tax increase can result in upward switching from low-priced to higher-priced brands due to a rise in the relative price of lower-priced brands. Under a system comprised entirely of ad valorem tax, then an increase in the tax rate would maintain the same relative prices and would have no impact on brand choice, all else remaining the same. If the tax system is a mix of ad valorem and specific taxes, the price gap is larger in countries that rely more heavily on ad valorem tax.[30] Under this system, the price gap still narrows a bit as the tax goes up, due to the specific component, and creates incentive to switch upward. Evidence from European Union countries suggests that under a more complicated tiered system, there is a potential for the price gap to increase as taxes increase, for example when the rates at the top end rise by relatively more than on the bottom end. While focusing on the implications for the specific tax regime in force in the two countries included in the present study, this paper points to the need for similar research in countries with ad valorem, mixed, or more complicated tax structures.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS.

This paper investigates the choice by smokers of premium and discount brand cigarettes in response to tax and price increases, based on a model that focuses on the behavioural impact of the price ratio of discount to premium brands. We estimate the model using longitudinal data from representative samples of smokers in Canada and the United States. This model explains why an increase in the tax rate and price that raises the relative price of discount brands may result in upward switching from discount to premium brands as happened in the United States during the 1990s, or conversely, why the share of discount brand cigarettes increased in Canada in response to declining relative price of discount brands during 2002–2005. Upward switching has not previously been seen as a possible response to higher prices, but the present model shows that upward switching naturally follows from the consideration of the change in the price ratio rather than change in average price, and that this phenomenon would be expected to occur under specific tax regimes rather than under ad valorem tax regimes, where an increase in base price does not change the price ratio.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Anne C. Quah for the editing and formatting input.

FUNDING

Funding for the research presented in this paper was provided by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Operating Grants 57897, 79551, and 115016, and a CIHR Strategic Training Program in Tobacco Research: Post-Doctoral Fellowship to the first author), the U.S. National Cancer Institute (R01 CA100362, the Roswell Park Transdisciplinary Tobacco Use Research Center (TTURC; P50 CA111236), and P01 CA138389), Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (045734), and a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research to the second author.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS: None declared.

PATIENT CONSENT: Obtained.

ETHICS APPROVAL: The ITC Surveys were cleared for ethics by Research Ethics Boards or International Review Boards at the University of Waterloo (Canada), Roswell Park Cancer Institute (US), and University of Illinois at Chicago (US).

Contributor Information

Nigar Nargis, Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Geoffrey T. Fong, Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, and Senior Investigator, Ontario Institute of Cancer Research, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Frank J. Chaloupka, Professor, Department of Economics and Director, ImpacTeen: A Policy Research Partnership to Reduce Substance Use, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Qiang Li, Research Scientist, Department of Psychology, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, and Visiting Scholar, Office of Tobacco Control, China CDC, Beijing, China.

References

- 1.WHO. Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER Package. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erikson M, Mackay J, Ross H. The Tobacco Atlas. 4. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; New York, NY: World Lung Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Effectiveness of Tax and Price Policies for Tobacco Control. Vol. 14. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2011. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention in Tobacco Control. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans WN, Farrelly MC. The compensating behavior of smokers: Taxes, tar, and nicotine. RAND Journal of Economics. 1998;29:578–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laxminarayan R, Deolalikar A. Tobacco initiation, cessation, and change: evidence from Vietnam. Health Economics. 2004;13:1191–1201. doi: 10.1002/hec.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oshfeldt RL, Boyle RG. Tobacco excise taxes and rates of smokeless tobacco use in the US: an exploratory ecological analysis. Tobacco Control. 1994;3:316–23. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohsfeldt RL, Boyle RG, Capilouto EI. Effects of tobacco excise taxes on the use of smokeless tobacco products. Health Economics. 1997;6:525–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1050(199709)6:5<525::aid-hec300>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohsfeldt RL, Boyle RG, Capilouto EI. NBER Working Paper No. 6486. National Bureau of Economic Research; 1998. Tobacco taxes, smoking restrictions, and tobacco use. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson ME, McLeod I. The effects of economic variables upon the demand for cigarettes inCanada. Mathematical Scientist. 1976;1:121–32. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pekurinen M. The demand for tobacco products in Finland. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84:1183–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pekurinen MJ. National Agency for welfare and Health. Research reports. Vol. 16. Helsinki: Vapk-Publishing; 1991. Economic Aspects of Smoking: Is There a Case for Government Intervention in Finland? [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young D, Borland R, Hammond D, et al. Prevalence and attributes of roll-your-own smokers in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(Supplement III):iii, 76–82. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanewinkel R, Isensee B. Five in a row—reactions of smokers to tobacco tax increases: population-based cross-sectional studies in Germany 2001–2006. Tobacco Control. 2007;16:34–37. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.017236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyland A, Laux FL, Higbee C, et al. Cigarette purchase patterns in four countries and the relationship with cessation: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(Supplement III):iii, 59–64. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lewit E, et al. Use of discount cigarettes by smokers in 20 communities in the United States, 1988–1993. Tobacco Control. 1997;6:S25–30. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.suppl_2.s25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lewit E, et al. Discrepancies in cigarette brand sales and adult market share: are new teen smokers filling the gap? Tobacco Control. 1997;6:S38–43. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.suppl_2.s38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai YW, Yang CL, Chen CS, et al. The effect of Taiwan’s tax-induced increases in cigarette prices on brand-switching and the consumption of cigarettes. Health Economics. 2005;14:627–641. doi: 10.1002/hec.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Hyland A, Fong GT, et al. Use of less expensive cigarettes in six cities in China: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) China Survey. Tobacco Control. 2010;19(Supplement 2):i 63–68. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.035782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson ME, Fong GT, Hammond D, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tobacco Control. 2006;15(Supplement III):iii, 12–18. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Canada. [accessed 17 July 2010];The Federal Tobacco Control Strategy at the Mid-way Mark: Progress and Remaining Challenges. 2006 Summer; http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/alt_formats/hecs-sesc/pdf/consult/_2006/ftcs-tfsc/draft-ebauche-eng.pdf.

- 21.Kuitenbrouwer P. Natives put new face on tobacco industry. [accessed 17 July 2010];Financial Post. 2003 May 29; http://www.ocat.org/opposition/industry.html.

- 22.Thompson F. [accessed 17 July 2010];Discount cigarettes and other cheap tobacco products, Non-Smokers’ Rights Association. 2004 May 17; http://www.nsra-adnf.ca/cms/index.cfm?group_id=1342.

- 23.Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada. [accessed 17 July 2010];Cigarette price war erodes public health gains. 2004 http://www.smoke-free.ca/pdf_1/fall2004.pdf.

- 24.Non-Smokers’ Rights Association (NSRA) [accessed 17 July 2010];NSRA’s Backgrounder on the Canadian Tobacco Industry and its Market, Non-Smokers’ Rights Association. 2005/2006 Winter; http://www.nsra-adnf.ca/cms/file/pdf/Backgrounder%20complete%20winter%202005_06.pdf.

- 25.Health Canada. [accessed 17 July 2010];Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey, Summary. 2005 http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/_ctums-esutc_2005/ann_summary-sommaire-eng.php.

- 26.Hyland A, Bauer JE, Li Q, et al. Higher cigarette prices influence cigarette purchase patterns. Tobacco Control. 2005;14:86–92. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tauras JA, Peck RM, Chaloupka FJ. The role of retail prices and promotions in determining cigarette brand market shares. Review of Industrial Organization. 2006;28:253–284. [Google Scholar]

- 28.UBS. [accessed 18 April 2011];What’s Up with State Excise Taxes? UBS Investment Research. 2011 Apr 14; http://www.ubs.com/investmentresearch.

- 29.Sobel RS, Garrett TA. Taxation and product quality: New evidence from generic cigarettes. Journal of Political Economy. 1997;105(4):880–87. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaloupka FJ, Peck R, Tauras JA, et al. Cigarette Excise Taxation: The Impact of Tax Structure on Prices, Revenues and Cigarette Smoking. NBER Working Paper No.16287. 2010 Aug; [Google Scholar]