Abstract

Testotoxicosis, a form of gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty, results from an activating mutation of the luteinizing hormone receptor expressed in testicular Leydig cells. Affected males experience early testosterone secretion, virilization, advancing bone age, and resultant short stature. Recently, the use of combination therapy with a potent antiandrogen agent (bicalutamide) and a third-generation aromatase inhibitor (anastrozole or letrozole) was reported to yield encouraging short-term results. We present here the results of longer-term treatment (4.5 and 5 years) with this combination therapy in 2 boys who demonstrated that it is well tolerated, slows bone-age advancement in the face of continued linear growth, and prevents progression of virilization.

Keywords: precocious puberty, aromatase inhibitors, bicalutamide, age determination by skeleton, gonadal disorders

Testotoxicosis (familial male-limited gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty [FMPP]) results from a mutant luteinizing hormone (LH) receptor that is constitutively active.1,2 The mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner with phenotypic expression limited to males. Mutations in the LH receptor in boys result in gonadotropin-independent Leydig cell production of testosterone and subsequent precocious pubertal development, typically before the age of 4 years. Boys present with tall stature, genital enlargement (enlarged penis with small-to-moderate increase in testicular volume), sexual hair, and advanced bone age (BA) that leads to compromised adult height. Meanwhile, girls with LH-receptor mutations are phenotypically normal and have age-appropriate sexual development. 3–7 The mechanism by which female gender is protective against phenotypic expression remains undetermined but has been postulated to be a result of low LH-receptor expression in prepubertal girls or ovarian thecal cell inefficiency of steroid biosynthesis at the 17,20-lyase rate-limiting step of androgen formation.8,9 In addition, temperature-sensitive mutations in Gsα, the stimulatory G-coupled protein subunit associated with the LH receptor, have been described. At the cooler (33°C) temperature of the testes, the activating Gsα mutation persists, whereas at body temperature (37°C) in the ovary, the mutated Gsα is degraded, which would explain a gender variance in expression. 10 Despite oligospermia in some affected males, most men and women retain adequate fertility and, therefore, can pass along the mutation to subsequent generations.5,11

Treatment of testotoxicosis in the past has included using inhibitors of steroidogenesis (ketoconazole), weak antiandrogen agents (spironolactone), and, subsequently, first-generation aromatase inhibitors (AIs) (testolactone). Although these therapies are effective in slowing growth velocity and reducing virilization, the risk of hepatotoxicity and adrenal insufficiency with ketoconazole and the requirement of multiple daily dosing are obstacles to achieving a favorable therapeutic outcome. A report of short-term combination therapy with a potent antiandrogen agent, bicalutamide, and a third-generation AI, anastrozole, also suggested efficacy in reducing growth rate and virilization and improving predicted adult height with the ease of less frequent dosing.12 We present here longer-term treatment data of 2 boys treated with bicalutamide plus anastrozole or letrozole combination therapy.

CASE REPORTS

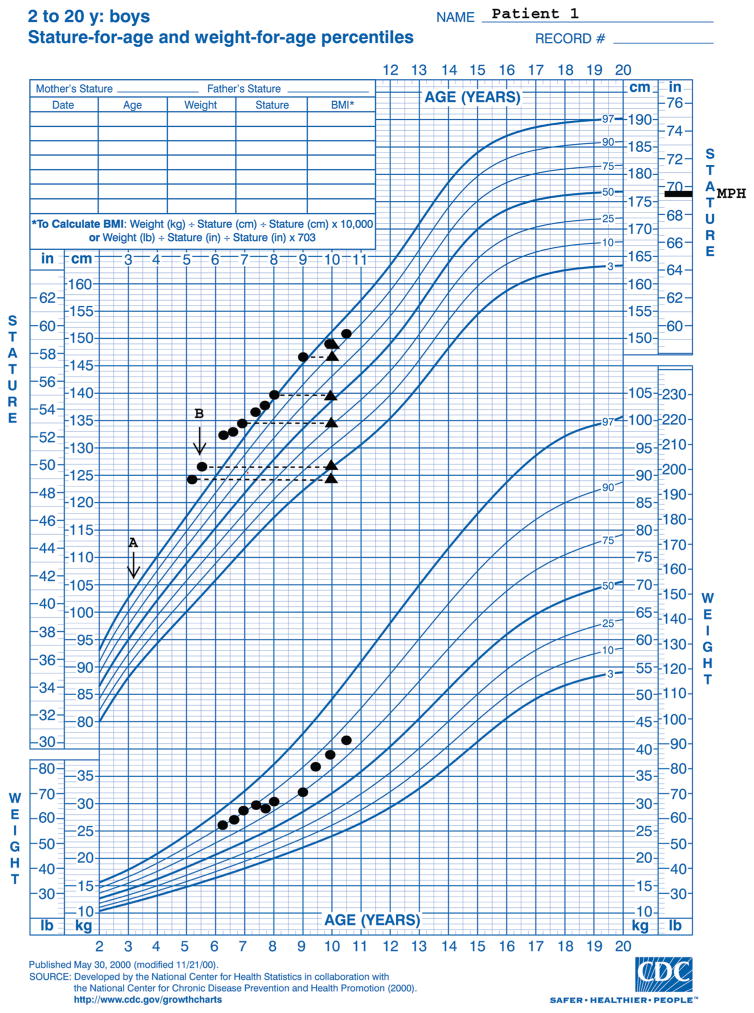

Patient 1 presented at a chronological age (CA) of 3.1 years with genital enlargement and tall stature (height age: 5 years, 4 months). Initial biochemical and radiologic evaluation revealed a BA of 4 years and a testosterone level of 2.3 nmol/L (normal prepubertal level: <0.3 nmol/L). A gonadotropin hormone–releasing hormone– stimulation test revealed a baseline LH level of 0.09 mIU/mL and follicle-stimulating hormone level of 0.84 mIU/mL and peak levels of LH at 2 mIU/mL and of follicle-stimulating hormone at 3.2 mIU/mL, which suggested a blunted (prepubertal) response. An LH-receptor mutation (Asp578Gly) was detected in the mother and child. He was initially treated with spironolactone and testolactone, but he experienced increased growth velocity and advancing BA associated with noncompliance. At 5 years 5 months of age, his BA had advanced to 10 years (BA/CA: 1.8) and testicular length measured 3.5 cm. Therapy was changed to bicalutamide (50 mg daily) and letrozole (2.5 mg daily). Depot leuprolide (11.5 mg intramuscularly every 4 weeks) was added at 5 years 6 months of age when his testicular length increased to 4 cm and gonadotropins increased to pubertal levels. Treatment has been well tolerated aside from minor hot flashes and has resulted in stabilization of BA advancement (BA: 10 years at a CA of 9 years 11 months) (Fig 1). Stabilization of BA in combination with continued normal growth velocity has increased his adult height prediction. He has had little virilization and has Tanner 2 pubic hair, a phallic length of 10 cm, stable testicular volume, and no axillary hair or odor.

FIGURE 1.

Growth chart for patient 1. A, Start of testolactone and spironolactone therapy; B, start of bicalutamide and letrozole (depot leuprolide was added 1 month later). ▲ indicates BA radiograph results at corresponding heights.

Patient 2 presented for evaluation of precocious puberty at 4.1 years of age when his testicular volume was 6 mL. His condition failed to respond to depot leuprolide treatment for presumed central precocious puberty. Findings 2 months after discontinuation of depot leuprolide included an ultrasensitive LH level of <0.02 mIU/mL and a testosterone level of 15 nmol/L. His BA was 9 years at a CA of 4.25 years (BA/CA: 2.1). An LH-receptor mutation was found in the father and child (Ile542Leu). Bicalutamide (50 mg daily) and anastrozole (1 mg daily) were begun for treatment of testotoxicosis. Depot leuprolide was restarted at 5.5 years of age in response to a stimulated LH level of 10.3 mIU/mL. Results from the first 17 months of therapy have already been reported.12 Over a total of 5.4 years of treatment, his BA/CA has declined to 1.4 (Fig 2), testicular volume has stabilized at 8 to 10 mL bilaterally, and pubic hair has stabilized at Tanner stage 2. His predicted adult height has increased from 168.9 cm to 178.2 cm.

FIGURE 2.

Growth chart for patient 2. A, Start of bicalutamide and anastrozole; B, depot leuprolide reinitiated. ▲ indicates BA radiograph results at corresponding heights. CASE REPORT

Laboratory study results throughout treatment of both patients have revealed no hepatotoxicity, undetectable estradiol levels, suppressed gonadotropins, and testosterone levels in the range of 4.3 to 13.1 nmol/L.

DISCUSSION

Historically, FMPP has been treated with ketoconazole, an inhibitor of the steroidogenic enzyme CYP17A1, or with spironolactone, a weak antiandrogen agent.13–15 Ketaconazole has been efficacious in the treatment of FMPP but has been limited by its potential for adverse effects (namely hepatoxicity and glucocorticoid deficiency) and required a high frequency of dosing (3 daily doses, 10 –20 mg/kg per day).16–19 Spironolactone has been a less efficacious therapy when used alone (twice daily, 2–5.7 mg/kg per day), but in combination with testolactone (4 times daily, 20–40 mg/kg per day), it has been shown to reduce growth velocity and skeletal maturation. 20–22 Because of its aldosterone-inhibiting effects, spironolactone may also result in mild diuresis, metabolic acidosis, and hyperkalemia. Bicalutamide is a potent nonsteroidal antiandrogen agent that was released for the treatment of prostate cancer in 1995.23 It directly binds to and inhibits the androgen receptor and increases androgen-receptor degradation. Bicalutamide’s prolonged half-life allows for convenient once-daily dosing. Doses of 2 mg/kg per day used for FMPP have been extrapolated from doses customarily used in adult men for the treatment of prostate cancer.12

Aromatase is a cytochrome p450 enzyme (CYP19) that catalyzes the conversion of C19 androgens to C18 estrogens. The first individuals described with an identifiable aromatase gene defect were male and female siblings. The mother virilized transiently during pregnancy. The male child demonstrated tall stature cause by unfused epiphyses (BA: 14 years at a CA of 24 years, 3 months), normal adult pubertal development, macro-orchidism, osteopenia, oligospermia, elevated gonadotropin levels, hyperinsulinemia, increased serum total low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides, and decreased high-density lipoprotein. 24 Inhibition of aromatase enzyme activity was first applied to the treatment of estrogen-responsive malignancies such as breast cancer but has since expanded to clinical trials in the treatment of endocrine disorders in childhood such as peripheral precocious puberty, gynecomastia, short stature, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia. 25–28 First- and second-generation AIs (aminoglutethimide, testolactone, formestane, fadrozole) have demonstrated <90% inhibition of CYP19, whereas third-generation AIs (letrozole, anastrozole) are more potent (97% inhibition), have a longer half-life (2 days), and demonstrate reversible inhibition of the enzyme.29

In a preliminary report, a third-generation AI (anastrozole, 1 mg daily) in combination with bicalutamide in FMPP was reported to be safe and effective in 2 boys.12 An additional report of 2 brothers treated with the combination of anastrozole and cyproterone acetate (a weak antiandrogen agent) also demonstrated effectiveness and tolerability.30 Short-term evaluation of 8 males taking anastrozole 1 mg daily for 10 weeks showed no change in body composition; metabolic rates of protein synthesis or degradation; carbohydrate, lipid, or protein oxidation; or kinetically measured bone calcium turnover.31 Although treatment with AIs in adolescent boys seems to cause no change in dual-energy radiograph absorptiometry-measured bone-mass accrual, a recent study revealed that treatment with letrozole (2.5 mg daily) for 2 years in peripubertal boys with idiopathic short stature led to increased cortical bone growth and inhibition of bone turnover compared with controls. Vertebral body deformities were observed in posttreatment spinal films but were also observed in control subjects.32 A phase II study of combination therapy with bicalutamide and anastrozole for the treatment of FMPP is currently underway, and the researchers plan to evaluate boys treated with this regimen until attainment of adult height (Bicalutamide Anastrozole Treatment for Testotoxicosis [BATT] Study, Astra Zeneca, www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT00094328).

Treatment of FMPP is often complicated by the early onset of central precocious puberty, evidenced by the elevation of gonadotropin levels and testicular enlargement while on therapy. Onset of central puberty may be hastened with AI therapy, because estrogen provides the primary feedback restraint on gonadotropin release at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary. 33,34 Addition of gonadotropinreleasing hormone agonist therapy reduces the testicular enlargement and supraphysiologic testosterone concentrations observed during AI therapy, which presumably allows the regimen to be more effective.

CONCLUSIONS

These data support the efficacy of third-generation AIs and the antiandrogen agent bicalutamide for the treatment of FMPP. This combination therapy provides a more convenient once-daily dosing regimen, although the cost of therapy is relatively more expensive than previous treatments (Table 1). Evaluation of the long-term effects of such therapy on adult height, fertility, metabolic parameters, and bone health are essential. Until longterm data are available from a larger sample of patients, this combination therapy should be used judiciously and cautiously.

TABLE 1.

Doses and Relative Cost of Various Treatments for FMPP

| Mechanism of Action | Dose for FMPP | Dosing Interval, h | Tablet Size, mg | Cost per Tablet, $a | Cost per Month $b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoconazole | Inhibits p450 enzymes | 10–20 mg/kg per d | 8 | 200 | 1.33 | 120 |

| Spironolactone | Weak antiandrogen agent | 2–5.7 mg/kg per d | 12 | 100 | 1.27 | 73 |

| Bicalutamide | Potent nonsteroidal antiandrogen agent | 2 mg/kg per d | 24 | 50 | 4.56 | 137 |

| Testolactone | First-generation AI | 20–40 mg/kg per d | 6 | 50 | 3.02 | 2174 |

| Anastrozole | Third-generation AI | 1 mg/d | 24 | 1 | 13.40 | 402 |

| Letrozole | Third-generation AI | 2.5 mg/d | 24 | 2.5 | 13.90 | 417 |

Cost information was obtained from Walgreens.com via personal communication on December 14, 2009.

Calculation based on maximum-dose therapy for a 30-kg, 135-cm, 1.06-m2 individual (average weight and stature of a 9-year-old boy).

ABBREVIATIONS

- FMPP

familial male-limited precocious puberty

- LH

luteinizing hormone

- BA

bone age

- AI

aromatase inhibitor

- CA

chronological

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Shenker A, Laue L, Kosugi S, Merendino JJ, Jr, Minegishi T, Cutler GB., Jr A constitutively activating mutation of the luteinizing hormone receptor in familial male precocious puberty. Nature. 1993;365(6447):652–654. doi: 10.1038/365652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawate N, Kletter GB, Wilson BE, Netzloff ML, Menon KMJ. Identification of constitutively activating mutation of the luteinising hormone receptor in a family with male limited gonadotropin independent precocious puberty (testotoxicosis) J Med Genet. 1995;32(7):553–554. doi: 10.1136/jmg.32.7.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schedewie HK, Reiter EO, Beitins IZ, et al. Testicular Leydig cell hyperplasia as a cause of familial sexual precocity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;52(2):271–278. doi: 10.1210/jcem-52-2-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal SM, Grumbach MM, Kaplan SL. Gonadotropin independent familial sexual precocity with premature Leydig and germinal cell maturation (familial testotoxicosis): effects of a potent luteinizing hormone-releasing factor agonist and medroxyprogesterone acetate therapy in four cases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57(3):571–579. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-3-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egli CA, Rosenthal SM, Grumbach MM, Montalvo JM, Gondos B. Pituitary gonadotropin-independent male-limited autosomal dominant sexual precocity in nine generations: familial testotoxicosis. J Pediatr. 1985;106(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80460-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiter EO, Brown RS, Longcope C, Beitins IZ. Male-limited familial precocious puberty in three generations: apparent Leydig-cell autonomy and elevated glycoprotein hormone alpha subunit. N Engl J Med. 1984;311(8):515–519. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408233110807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiter EO, Narjavaara E. Testotoxicosis: current viewpoint. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2005;3(2):77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piersma D, Verhoef-Post M, Berns EM, Themmen AP. LH receptor gene mutations and polymorphisms: an overview. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;260–262:282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latronico AC, Segaloff DL. Naturally occurring mutations of the luteinizing-hormone receptor: lessons learned about reproductive physiology and G protein-coupled receptors. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(4):949–958. doi: 10.1086/302602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clapham DE. Signal transduction: why testes are cool. Nature. 1994;371(6493):109–110. doi: 10.1038/371109a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertelloni S, Baroncelli GI, Lala R, et al. Long-term outcome of male-limited gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty. Horm Res. 1997;48(5):235–239. doi: 10.1159/000185521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreher NC, Pescovitz OH, Delameter P, Tiulpakov A, Hochberg Z. Treatment of familial male-limited precocious puberty with bicalutamide and anastrozole. J Pediatr. 2006;149(3):416–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajfer J, Sikka S, Rivera F, Handelsman DJ. Mechanism of inhibition of human testicular steroidogenesis by oral ketoconazole. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63(5):1193–1198. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-5-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland FJ, Fishman L, Bailey JD, Fazekas AT. Ketoconazole in the management of precocious puberty not responsive to LHR-Hanalogue therapy. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(16):1023–1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198504183121604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corvol P, Michaund A, Menard J, Freifeld M, Mahoudeau J. Antiandrogenic effect of spironolactones: mechanism of action. Endocrinology. 1975;97(1):52–58. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-1-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soriano-Guillén L, Lahlou N, Chauvet G, Roger M, Chaussain JL, Carel JC. Adult height after ketoconazole treatment in patients with familial male-limited precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(1):147–151. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Donaldson MD, Gibson NA, Wallace AM. Hazards of ketoconazole therapy in testotoxicosis. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83(9):994–997. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almeida MQ, Brito VN, Lins TS, et al. Longterm treatment of familial male-limited precocious puberty (testotoxicosis) with cyproterone acetate or ketoconazole. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69(1):93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Best TR, Jenkins JK, Murphy FY, Nicks SA, Bussell KL, Vesely DL. Persistent adrenal insufficiency secondary to low-dose ketoconazole therapy. Am J Med. 1987;82(3 Spec No):676–680. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(87)90123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laue L, Kenigsberg D, Pescovitz OH, et al. Treatment of familial male precocious puberty with spironolactone and testolactone. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(8):496–5022492636. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902233200805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laue L, Jones J, Barnes KM, Cutler GB., Jr Treatment of familial male precocious puberty with spironolactone, testolactone, and deslorelin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76(1):151–155. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.1.8421081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leschek EW, Jones J, Barnes KM, Hill SC, Cutler GB., Jr Six-year results of spironolactone and testolactone treatment of familial male-limited precocious puberty with addition of deslorelin after central puberty onset. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(1):175–178. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furr BJ. The development of Casodex (bicalutamide): preclinical studies. Eur Urol. 1996;29(suppl 2):83–95. doi: 10.1159/000473846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morishima A, Grumbach M, Simpson E, Fisher C, Qin K. Aromatase deficiency in male and female siblings caused by a novel mutation and the physiological role of estrogens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(12):3689–3698. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.12.8530621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunkel L. Use of aromatase inhibitors to increase final height. Mol Cell Endcrinol. 2006;254–255:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plourde PV, Reiter EO, Jou HC, et al. Members of the Astra-Zeneca Gynecomastia Study. Safety and efficacy of anastrozole for the treatment of pubertal gynecomastia: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(9):4428–4433. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hero M, Norjavaara E, Dunkel L. Inhibition of estrogen biosynthesis with a potent aromatase inhibitor increases predicted adult height in boys with idiopathic short stature: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(12):6396–6402. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merke DP, Keil MF, Jones JV, Fields J, Hill S, Cutler GB., Jr Flutamide, testolactone, and reduced hydrocortisone dose maintain normal growth velocity and bone maturation despite elevated androgen levels in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(3):1114–1120. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geisler J, Lonning PE. Aromatase inhibition: translation into a successful therapeutic approach. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(8):2809–2821. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eyssette-Guerreau S, Pinto G, Sultan A, Le Merrer M, Sultan C, Polak M. Effectiveness of anastrozole and cyproterone acetate in two brothers with familial male precocious puberty. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2008;21(10):995–1002. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2008.21.10.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mauras N, O’Brien KO, Klein KO, Hayes V. Estrogen suppression in males: metabolic effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(7):2370–2377. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.7.6676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hero M, Mäkitie O, Kröger H, Nousiainen, Toiviainen-Salo S, Dunkel L. Impact of aromatase inhibitor therapy on bone turnover, cortical bone growth and vertebral morphology in pre- and peripubertal boys with idiopathic short stature. Hormone Res. 2009;71(5):290–297. doi: 10.1159/000208803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayes FJ, Seminara SB, Decruz S, Boepple PA, Crowley WF., Jr Aromatase inhibition in the human male reveals a hypothalamic site of estrogen feedback. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(9):3027–3035. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw ND, Histed SN, Srouji SS, et al. Estrogen negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion: evidence for a direct pituitary effect in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(4):1955–1961. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]