Abstract

Objective

To review key aspects of family caregiving as it applies to older adults with cancer, discuss the implications of caregiving on the physical and emotional health of caregivers, and discuss future research needs to optimize the care of older adults with cancer and their caregivers.

Data Sources

Literature Review

Conclusions

The number of older adults with cancer is on the rise and these older adults have significant caregiving needs. There is a physical, emotional, and financial toll associated with caregiving.

Implications for Nursing Practice

As the US population ages, it will be even more important that we identify vulnerable older adults, understand their caregiving needs, and mobilize healthcare and community resources to support and assist their caregivers.

Keywords: Geriatric Oncology, Family Caregiver, Caregiver Strain, Older Adult with Cancer

In the year 2000, approximately 12% of the US population was 65 years old or older,1 and this number is projected to increase to 20% of Americans by 2030.2 Increasing age is accompanied with a decrease in physiologic reserve and an increase in comorbid medical illnesses that are associated with an increased utilization of healthcare resources. Although patients age 65 and older comprise 12% of the US population, they utilize 34% of prescription drugs, 35% of hospital stays, 38% of emergency response services, and 90% of nursing home beds.3 However, much of the day to day care of the aging population is not performed by the healthcare system, but instead is performed by family and friends, known as “informal caregivers.” In fact, 63% of home care of older adults with cancer is provided by “informal” caregivers.4 Caregiving, although essential, can be associated with a financial, physical, and emotional toll. Weighing into the burden of caregiving is not only the caregiver’s age, but also the amount of caregiving the patient requires. Furthermore, these services are often unpaid and can come with a financial toll for both the patient and family.

With the aging of the US population, the need for these family caregivers is on the rise. This is especially pertinent to the geriatric oncology population where the effects of either cancer or treatment can be associated with an increased need for physical assistance. In particular there is a projected 67% increase in the number of cancer cases in individuals age 65 and older by 2030.5 The healthcare system is ill-prepared for the growth in the aging population, with an anticipated shortage of both oncologists6 and geriatricians.3 The rise in the geriatric oncology population will be associated with an increased need for family caregivers. In this article we will review the physical, emotional, and financial aspects of family caregiving for the geriatric oncology patient and discuss the implications and future research directions.

Family Caregivers: The Physical Needs of the Oncology Patient

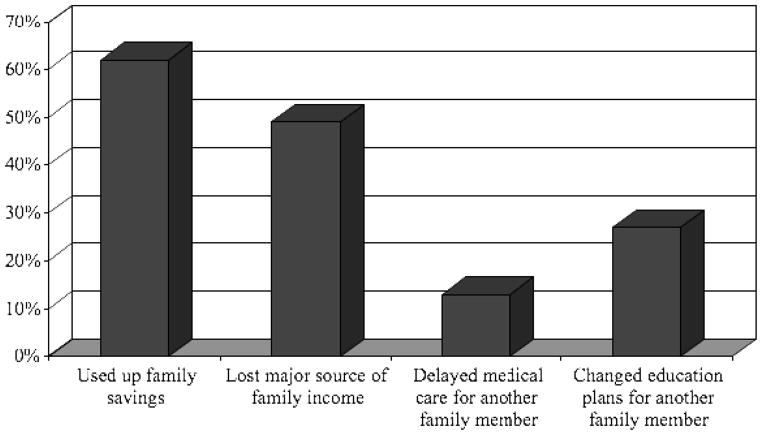

The physical needs of older adults with cancer were quantified in a multicenter study of 500 older adults who were scheduled to begin a new chemotherapy regimen. Eighteen percent of these patients reported to have fallen within 6 months of the study.7 Forty-three percent of the patients reported a need for assistance with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLS). These IADLs are basic activities which are required to maintain independence in the community, such as making telephone calls, taking transportation, or doing housework. These types of activities are typically provided by informal caregivers (family and friends). However, caregivers may have difficulty providing patients with the care they need because of limitations from their own health conditions.8 The average age of family caregivers is 63.9 In a study of over 1000 caregivers, 36% were found to be in fair to poor health or to have a serious health condition. These caregivers (also known as “vulnerable” caregivers) were more likely to be taking care of patients who required assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs; such as bathing, dressing, or toileting) and IADLs than non-vulnerable caregivers (Figure 1). For example, 52% of vulnerable caregivers provided assistance with dressing in comparison to 36% of non-vulnerable caregivers (p=0.001). 8

Figure 1. Assistance Provided by Caregivers*8.

*Graphed values were found to be significant

Caregiving may be associated with a physical toll. For example, in the study described above, 32% of vulnerable caregivers, in comparison to 15% of nonvulnerable caregivers (p=0.001) felt as though their health has suffered as a result of providing care for a patient.8 In another study of 392 spousal caregivers, 56% reported caregiving strain. Caregivers who reported caregiving strain were found to have a 63% increased risk of 4-yr mortality in comparison to controls, even when controlling for sociodemographics and caregiver physical health status.10

Family Caregiving: The Emotional Toll

The strain of caring for an elderly patient with cancer not only takes a physical toll on family caregivers, but also an emotional one. Multiple studies have shown that depression is common in family caregivers.11–15 In a cohort of 310 family caregivers, 67% were found to be depressed using the Beck Depression Inventory and 35% percent of family caregivers were found to have severe depression. 11 In another study of 51 family caregivers, 53% were depressed based on a Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale and 95% reported severe sleeping problems based on a Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Score.12

There are patient and caregiver characteristics which are associated with an increased the risk of depression in family caregivers (Table 1).11, 16–17 In a study of 618 family caregivers of older adults with newly diagnosed cancer, the following characteristics were associated with caregiver depression: the caregiver’s health status, the caregiver’s age, the patient’s symptoms, and the patient’s ability to complete ADLs and IADLs. 17 In another study of 310 family caregivers in Korea, caregiver depression was significantly associated with the following caregiver characteristics: being female, being the patient’s spouse, having a poor health status, feeling burdened, and having poor adaptation. The following patient characteristic was significantly associated with caregiver depression: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 3 or 4. 11

Table 1.

| Caregiver Characteristics | Patient Characteristics |

|---|---|

|

|

Abbreviations: ADLs – activities of daily living; IADLs – instrumental activities of daily living; ECOG PS – Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status

The spouse caregiver of the patient may be at even higher risk for depression than the patient themselves. In a study of 101 spouse caregivers of patients with advanced gastrointestinal or lung cancer, 39% of caregivers versus 23% of patients met threshold for depression based on the Beck Depression Inventory-2 scale. 13 Predictors of depression in spouse caregivers included caregiver burden, caregiver anxiety, marital satisfaction, and having an avoidant personality. 13

Children caregivers are also at risk for caregiver strain and psychological side effects. In a secondary data analysis of the National Hospice study, husband and daughter caregivers of 213 patients with metastatic breast cancer were compared. Daughter caregivers, in comparison to husband caregivers, were found to have increased caregiver strain, anxiety, and depression. 14 Among both husbands and daughters, older caregiver age was associated with better bereavement adjustment. In another study of 87 caregivers of adults with cancer, younger caregivers were found to have increased difficulty with caregiving, global strain, depression, fatigue, and mood disturbances.15 Young women, in particular, were at an increased risk of caregiving strain. This is speculated to be because of the added responsibility of caregiving on top of their daily responsibilities with their own families as well as work responsibilities. 14–15

Family Caregiving: The Financial Toll

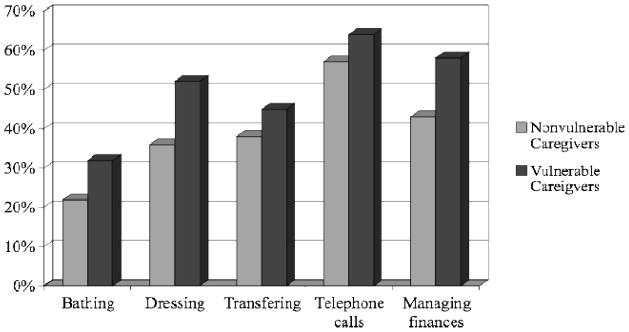

The yearly value of caregiving services provided by informal caregivers is approximately $450 billion. 18 This overwhelming value unfortunately does not come without financial repercussions for the family. In a study involving 310 family caregivers, 48% were found to have lost a major source of income and 62% used up their family savings. Some families were forced to delay medical care (13%) or change education plans (27%) for another family member (Figure 2).11

Figure 2.

Financial impact of Caregiving on Family11

More than half of family caregivers are employed but approximately a third lose time at work due to the caregiving services they provide. 19 Family caregivers are more likely to miss work if the patient they are providing care for requires assistance with IADLs. 19 Sixty-nine percent of caregivers who were employed reported having missed work due to careigiving responsibilities. 20 This negative impact on work is worse during the terminal period when compared to during the palliative period. A study of 89 caregivers who were followed from the beginning of the palliative period to the beginning of the terminal period revealed that 53% of caregivers missed work during the palliative period compared to 76% during the terminal period. During the terminal period, more caregivers were found to be depressed (30% in terminal period versus 9% in palliative period) and have increased anxiety (39% in terminal period versus 35% in palliative period). 20

Improving the Family Caregiver’s Quality of Life

There is much that healthcare professionals are able to do to help improve quality of life for family caregivers. In a study of 194 family caregivers of patients receiving chemotherapy for leukemia, the participants were asked to identify gaps in their knowledge regarding caregiving which the healthcare team could provide assistance with. They identified the following 3 areas: giving medications (72%), managing side effects of medications (84%), and managing symptoms (pain – 78%, nausea and vomiting – 80%, and fatigue – 82%). Family caregivers were also asked to identify other areas in which nurses could help improve their quality of life as a caregiver. The following topics were identified: improved communication; coordination of schedules (between the patient, the healthcare provider and the caregiver’s schedules); provide support; provide education; and provide a positive attitude.21

Identifying Geriatric Oncology Patients with Increased Needs: the Role of the Geriatric Assessment

A geriatric assessment is a tool utilized by geriatricians to identify the needs of older adults. 22 This assessment includes an evaluation of the patient’s functional status, comorbidities, nutritional status, psychosocial state, cognition, and review of medications.23 This geriatric assessment has now been integrated into oncology practice to identify the needs of older adults with cancer as well as to identify those older adults who are at risk of chemotherapy toxicity. A challenge in integrating the geriatric assessment into oncology care has been the time needed to perform this assessment. Investigators have been working towards developing an assessment which can be primarily self completed by the patient, thereby minimizing healthcare provider time.22 Subsequently the time required by the healthcare provider is spent reviewing the results of the assessment and developing the plan for care. For example, the assessment could identify patients who need assistant with ADLs and IADLs. These patients could be referred for a visiting nurse and social work evaluations. This could help mobilize resources in the community to provide assistance for the patient and their caregiver. If the patient is found to have depression or anxiety, they could be referred for a psychology and/or psychiatry consultation. If the patient is found to have unintentional weight loss, they could be referred for a nutritional consultation. In summary, the needs of these patients would be identified early in the treatment course and assistance would be provided, thereby increasing support for the patient and the caregiver.7

A geriatric assessment could also be utilized to identify older adults at risk of chemotherapy toxicity. For example, the following questions from the geriatric assessment specifically identified older adults at risk for chemotherapy toxicity (based on NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grade 3–5 toxicity): hearing impairment, limitations in walking one block, need for medication assistance, decrease in social activities because of either physical or emotional health, and falls (≥>1 within 6 months of the study). 7 The CRASH (Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients) identified risk factors for hemtalogic and non-hematologic toxicity from chemotherapy. The following factors were associated with an increased risk of hematologic chemotherapy toxicity: diastolic blood pressure >72; IADL score of 10–25 (using the Lawton 9-item IADL scale); lactate dehydrogenase >459 U/L; and a Chemotox score (toxicity of a given chemotherapy regimen) >0.44. The following factors were associated with an increase risk of non-hematologic chemotherapy toxicity: ECOG performance status >0; Folstein Mini-Mental Status score <30; Mini-Nutritional Assessment score <28; and a Chemotox score >0.44. 24

Future Research Implications

While the health care system typically focuses primarily on the patient, the current literature demonstrates that the family caregiver also needs specialized care. In an ideal healthcare system, the healthcare team would understand both the patient’s and the family caregiver’s perspectives which would result in better care for the patient. In effect, both parties’ needs are a part of caring for the patient. Currently, an office visit is comprised of the healthcare team focusing on the patient. These office visits may need to be expanded to incorporate the family caregiver and their needs.

Incorporating the family caregiver into the office visit and addressing their needs as related to caring for the patient may have financial implications for the healthcare system. Patient and caregiver needs can be evaluated early in the treatment course. By doing so, we may be able to decrease the number of hospitalizations and emergency room visits. By identifying patients early who have an increase need, we could also decrease caregiver strain and potentially prevent detrimental effects caregiving may have on family caregivers. Future research is needed to identify whether implementing this support for patients and caregivers early in the treatment plan can decrease the economical and psychosocial strain associated with caregiving.

Conclusion

The number of older adults with cancer is on the rise and these older adults have significant caregiving needs. There is a physical, emotional, and financial toll associated with caregiving. As the US population ages, it will be even more important that we identify vulnerable older adults and provide assistance for their caregivers. Integrating geriatric principles into oncology care through a geriatric assessment may be a way of identifying those older adults who have the greatest need and thereby making it possible to mobilize healthcare and community resources to assist their caregivers.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hurria’s salary is supported by 1R01AG037037-01 (PI: Arti Hurria, MD), U13AG038151-01 (PI: Arti Hurria, MD), and 1 P01 CA 136396 (PI: Betty Ferrell, PhD)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Werner Carrie. The Older Population: 2010. The United States Census Bureau; [Accessed December 18th, 2011]. http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-09.pdf Published November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Interim Projections by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 2000–2050. The United States Census Bureau; [Accessed October 17th, 2011]. http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/usinterimproj/natprojtab02a.pdf Published March 18, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington D.C: National Academies of Sciences; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caregiving in the US: A Focused Look at Those Caring for Someone Age 50 or Older. National Alliance for Caregiving; [Accessed March 2nd, 2012]. http://immn.org/nac/research/general Published November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, et al. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: Burdens upon an aging, changing nation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(17):2758–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hortobagyi G. A Shortage of Oncologists? The American Society of Clinical Oncology Workforce Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1468–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting Chemotherapy Toxicity in Older Adults with Cancer: a Prospective Multicenter Study. J ClinOnco. 2011;29(25):3457–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navaie-Waliser M, Feldman PH, Gould DA, et al. When the Caregiver Needs Care: The Plight of Vulnerable Caregivers. Am J Pub Health. 2002;92(3):409–13. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fact sheet: Selected Caregiver Statistics. Family Caregiver Alliance; [Accessed September 12, 2011]. www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp Published 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a Risk Factor for Mortality. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhee YS, Yun YH, Park S, et al. Depression in Family Caregivers of Cancer Patients: The Feeling of Burden as a Predictor of Depression. J ClinOncol. 2008;26(36):5890–5895. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter PA, Acton GJ. Personality and Coping: The Predictors of Depression and Sleep Problems among Caregivers of Individuals who Have Cancer. JGerontol Nurs. 2006;32(2):45–53. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20060201-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, et al. Hidden Morbidity in Cancer: Spouse Caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(30):4829–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernard LL, Guarnaccia CA. Two Models of Caregiver Strain and Bereavement Adjustment: A Comparison of Husband and Daughter Caregivers of Breast Cancer Hospice Patients. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):808–16. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.6.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schumacher KL, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG, et al. Effects of Caregiving Demand, Mutuality, and Preparedness on Family Caregiver Outcomes During Cancer Treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(1):49–56. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarna L, Cooley ME, Brown JK, et al. Quality of Life and Health Status of Dyads of Women with Lung Cancer and Family Members. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(6):1109–16. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.1109-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doorenbos AZ, Given B, Given CW, et al. The Influence of End-of-Life Cancer Care on Caregivers. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(3):270–81. doi: 10.1002/nur.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valuing the Invaluable: 2011 Update. AARP Public Policy Institute; [Accessed September 12, 2011]. The Economic Value of Family Caregiving in 2009. http://www.aarp.org/research/ppi Published June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherwood PR, Donovan HS, Given CW, et al. Predictors of Employment and Lost Hours from Work in Cancer Caregivers. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17(6):598–605. doi: 10.1002/pon.1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, et al. Family Caregiver Burden: Results of a Longitudinal Study of Breast Cancer Patients and their Principal Caregivers. Canadian Med Assoc J. 2004;170(12):1795–1801. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamayo GJ, Broxson A, Munsell M, et al. Caring for the Caregiver. OncolNurs Forum. 2010;37(1):E50–E57. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E50-E57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a Cancer-Specific Geriatric Assessment: a feasibility study. Cancer. 2005;104(9):1998–2005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurria A. Geriatric Assessment in Oncology Practice. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2009;57(Suppl 2):S246–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, et al. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: The Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. [Accessed November 30, 2011];Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26646. published online ahead of print November 9, 2011. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.26646/pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]