Abstract

Introduction

Protein production and secretion are essential to syncytiotrophoblast function and are associated with cytotrophoblast cell fusion and differentiation. Syncytiotrophoblast hormone secretion is a crucial determinant of maternal-fetal health, and can be misregulated in pathological pregnancies. Although, polarized secretion is a key component of placental function, the mechanisms underlying this process are poorly understood.

Objective

While the octameric exocyst complex is classically regarded as a master regulator of secretion in various mammalian systems, its expression in the placenta remained unexplored. We hypothesized that the syncytiotrophoblast would express all exocyst complex components and effector proteins requisite for vesicle-mediated secretion more abundantly than cytotrophoblasts in tissue specimens.

Methods

A two-tiered immunobiological approach was utilized to characterize exocyst and ancillary proteins in normal, term human placentas. Exocyst protein expression and localization was documented in tissue homogenates via immunoblotting and immunofluorescence labeling of placental sections.

Results

The eight exocyst proteins, EXOC1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, were found in the human placenta. In addition, RAB11, an important exocyst complex modulator, was also expressed. Exocyst and Rab protein expression appeared to be regulated during trophoblast differentiation, as the syncytiotrophoblast expressed these proteins with little, if any, expression in cytotrophoblast cells. Additionally, exocyst proteins were localized at or near the syncytiotrophoblast apical membrane, the major site of placental secretion

Discussion/Conclusion

Our findings highlight exocyst protein expression as novel indicators of trophoblast differentiation. The exocyst’s regulated localization within the syncytiotrophoblast in conjunction with its well known functions suggests a possible role in placental polarized secretion

Keywords: Trophoblast, Placenta, Exocyst complex, RAB11, Polarization1

1. INTRODUCTION

The exocyst complex is a principal regulator of polarized secretion through its role in vesicular trafficking, tethering, and fusion [1, 2]. A widely expressed, highly conserved octameric protein complex, the exocyst proteins were originally identified as Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants exhibiting similar defective secretory phenotypes whereby vesicles accumulated at the plasma membrane (PM), but failed to undergo exocytic fusion [3]. Several of these yeast secretory (Sec) mutants, Sec3, Sec5, Sec6, Sec8, Sec10 and Sec15, harbored aberrant alleles that were later identified as encoding six of the eight components of the exocyst complex. Since their discovery, mammalian counterparts to these Sec mutants as well as additional components have been identified. In mammals, the exocyst complex is comprised of: EXOC1, EXOC2, EXOC3, EXOC4, EXOC5, EXOC6, EXOC7, and EXOC8. For over two decades, the exocyst has been the source of extensive study, particularly with regard to vesicular trafficking and exocytosis.

The exocyst complex localizes to dynamic areas of the PM where it mediates the delivery of Golgi-derived secretory vesicles [4]. Additionally, exocyst proteins interact with numerous ancillary proteins, which integrate cell signaling and facilitate complex assembly and function. In particular, GTPases are definitive regulators of the exocyst complex [5–8]. It has been proposed that the assembly of the mammalian exocyst complex is a sequential process with EXOC1 and 7 localizing to targeted areas of the PM [9–12]. Studies also suggest that EXOC1 and 7 assist in the formation of PM associated target membrane Soluble NSF Attachment Receptor proteins (t-SNAREs) [13–15], and additionally interact with GTPases at the PM to organize the cytoskeleton in preparation for vesicle delivery [4, 16, 17].

Secretory vesicles accumulate vesicle membrane Soluble NSF Attachment Receptor proteins (v-SNAREs) and the peripherally associated GTPase RAB11 [18–20]. RAB11, a well documented regulator of vesicular trafficking, is required for exocyst formation and function, as it directs secretory vesicles to the PM [21–23]. Activated, GTP bound RAB11 engages EXOC6 [21, 22], which in turn recruits EXOC2, 3, 4, 5, and 8. It is thought these 6 components shuttle along microtubule motor proteins [24] to the PM, to couple with EXOC1 and 7, thus forming the holocomplex [18] and facilitating the v-SNARE and t-SNARE interactions required for vesicle fusion [14, 15, 25].

In addition to its role in secretion, the exocyst complex has recently been shown to be integral in a wide array of cellular processes, including cell growth, division, polarization, and motility, many with ties to human diseases [2]. Although the exocyst complex has been extensively characterized in yeast, flies, and mammalian cells, limited research has been conducted in human primary cells and tissues. Moreover, before our report, the expression, localization, and function of the exocyst complex within the human placenta, remained entirely unexplored. Using a proteomics approach to analyze the sub-proteome of the apical plasma membrane of the syncytiotrophoblast (STB) cell layer of the human placenta [26, 27], we identified five of the eight exocyst complex proteins, EXOC1, 2, 3, 5, and 8. Of these, EXOC2, 3, and 8 were identified with at least two unique peptides, while EXOC1 and 5 were only identified by a single peptide, and thus not included in the published data set. In this study, we have validated the previous proteomics data and investigated the expression of the full complement of exocyst proteins in the human placenta. Additionally, we have sought to ascertain where within the placenta these proteins reside. An immunobiological approach was used to address these questions.

Herein we report, for the first time, that all eight of the exocyst complex proteins are expressed in the human placenta, thus validating and extending our previous data. Additionally, we observed concomitant expression of the exocyst complex effector, RAB11. Our work illustrates the exocyst proteins to be concentrated within the differentiated STB, with little, if any, expression in precursor cytotrophoblast (CTB) cells.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Reagents

A murine monoclonal antibody to exocyst complex component 2 (Sec5/EXOC2) and rabbit polyclonal antibodies to exocyst complex components 1(EXOC1), 5(EXOC5/Sec10), 6(EXOC6), and 7(EXOC7) were obtained from Proteintech (Chicago, IL). A rabbit polyclonal to exocyst complex component 8 (EXOC8) was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). From BD Transduction Laboratories, we purchased murine monoclonal antibodies to RAB11 (47/RAB11) and exocyst complex component 4 (14/Sec8). We acquired a murine monoclonal antibody to GAPDH from Covance (Princeton, NJ), and a rabbit polyclonal antibody to exocyst complex component 3 (EXOC3) from NovaTeinBio (Woburn, MA). Murine and rabbit monoclonal antibodies against E-cadherin (CDH1) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies, goat anti-mouse/rabbit and chicken anti-goat, were obtained from Molecular Probes/Invitrogen (Eugene, OR), and HRP-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit/mouse from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). Control mouse IgG (sc-2025) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX); Control Chrome Pure goat (005-000-003) and rabbit (011-000-003) IgG were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch.

2.2 Placental Tissue

Our study was performed using tissues obtained with informed consent and following the protocols approved by the Biomedical Sciences Institutional Review Board at Ohio State University. De-identified samples were collected from uncomplicated, term deliveries free of evident pathologies and processed within 20 minutes of delivery. Biopsies (~2cm2) were dissected from the placenta between the basal and chorionic surfaces and rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature (RT), rinsed in PBS for 10 minutes 6 times and incubated in 20% sucrose/PBS overnight at 4°C. Specimens were embedded with Tissue-Tek Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound, frozen over liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. Fresh tissue was frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C.

2.3 Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Sections (15μm) of human placental tissue were cut from OCT blocks using a Shandon Cryotome and collected on Superfrost®Plus microscope slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Sections were rehydrated in PBS for 10 minutes and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin and 20% fetal bovine serum in PBS for 1 hour. Antigen retrieval was performed prior to blocking for 1) EXOC3, 7, and 8 using citrate buffer (10mM Citric Acid, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) at 100°C for 40 minutes followed by 20 minutes at RT and 2) RAB11 using 0.5% SDS in PBS for five minutes at RT. Sections were incubated with 1° antibody in blocking solution overnight at 4°C, washed 6 times for 10 minutes in PBS, incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated 2° antibodies (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen) for 1 hour, washed with PBS, and mounted using ProLong Gold containing DAPI (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen). Primary antibodies were used at the following concentrations: EXOC1 at 2.5μg/ml, EXOC2 at 12.0μg/ml, EXOC5 at 3.1μg/ml, EXOC6 at 2.1μg/ml, EXOC7 at 0.7μg/ml, CHD1 (rabbit) at 10μg/ml, CDH1 (mouse) 0.25μg/ml, and EXOC3, 4, 8, Rab11 at 1.25μg/ml. Secondary antibodies were used at a final concentration of 10μg/ml. Immunofluorescence controls were incubated with matched non-immune mouse, rabbit, or goat IgG.

Z-stack images were collected using Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope. Images were captured using a 0.5μm step size with a 50% overlap and using a 40X objective with a 1.5X digital zoom (Figures 2–4), a 40X objective and 3X digital zoom (Figures 2–4 Insets), or 40X objective without a digital zoom (Supplementary Figures 2–4). Figures were compiled using Photoshop. (n= At least 3 normal term placentas).

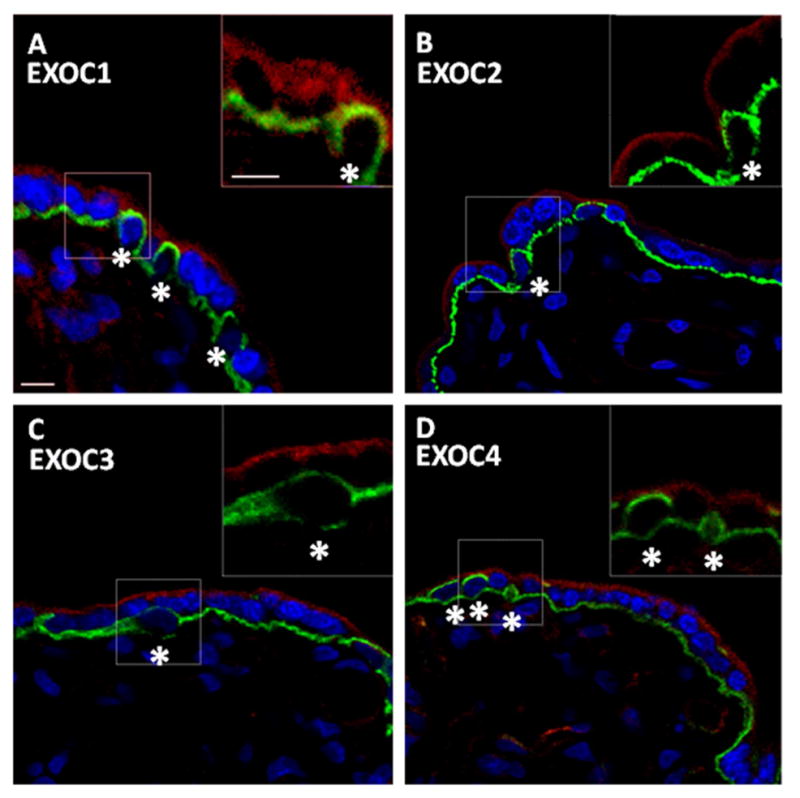

Figure 2. EXOC1, 2, 3, and 4 expression and localization in the human placenta.

A–D. Confocal images of EXOC1, 2, 3, and 4 in human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slices. Exocyst and E-cadherin (CDH1) protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. CDH1 labeling demarcates the boundary between cytotrophoblast cells (CTBs) and the syncytiotrophoblast (STB) cell layer. CTBs are largely encapsulated by CDH1, and are indicated by an asterisk. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. Dashed boxes distinguish regions of interest (ROI). Insets are a 3X digital zoom of associated ROI; the insets show only the red and green channels. A. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC1 and CDH1 localization; inset exhibits EXOC1 STB localization. B. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC2 and CDH1 localization; Inset exhibits EXOC2 STB localization. C. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC3 and CDH1 localization; Inset exhibits EXOC3 STB localization. D. Single optical slice representing placental Exoc4 and CDH1 localization; Inset exhibits EXOC4 STB localization. Exocyst protein expression was localized throughout the STB. Little, if any, expression of exocyst proteins was observed in CTBs. Scale bars=10μm.

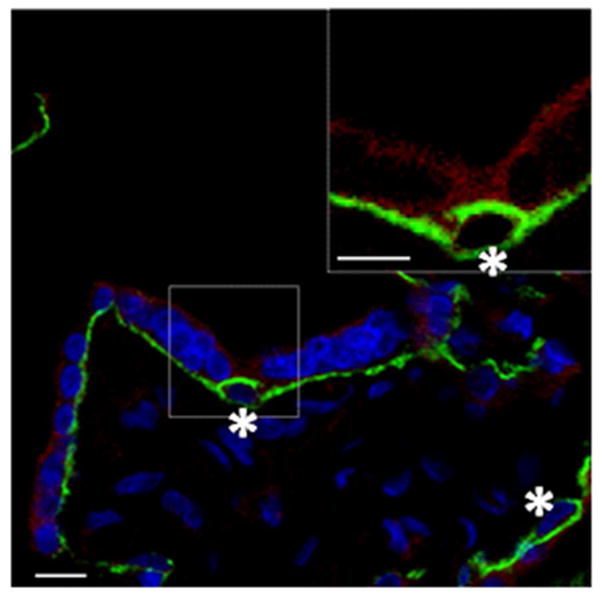

Figure 4. RAB11 expression and localization in the human placenta.

Confocal image of RAB11 in a human placental section showcased as single representative optical slices. RAB11 and CDH1 protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. CTBs are indicated by an asterisk. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. Dashed box distinguishes ROI; the inset shows only the red and green channels. Inset is a 3X digital zoom of the associated ROI. Single optical slice representing placental RAB11 and CDH1 localization; Inset exhibits RAB11 STB localization. RAB11 protein is localized within the STB cell layer cytosol, with little, if any, expression observed in CTBs. Scale bars=10μm

2.4 Immunoblotting

Placental tissue (60–120mg) was pulverized with a mortar and pestle under liquid N2 and incubated for 20 minutes in ice-cold octylglucoside lysis buffer (150 mM Na2PO4, 60 mM n-octyl β-D-glucopyranoside, 10 mM D-gluconic acid lactone, 1 mM EDTA) [28]. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 14,000xg at 4°C; supernatants were retained and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration was measured using the Pierce BCA Protein Determination Assay. Samples were added to Tris-buffered 1% SDS to yield a final concentration of 100μg protein and boiled for 5 minutes. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, blocked with 5% milk in TBST for 1 hour, and incubated with 1° antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed in TBST, probed with HRP-labeled 2° antibodies, developed with Thermo Scientific SuperSignal® Chemiluminescent Substrate, and recorded on Life Science BluBlot™ film. (n= 3 Normal term placentas). Primary antibodies were used at the following concentrations: EXOC1 and 4 at 0.25μg/ml, EXOC2 at 1.2μg/ml, EXOC3 at 0.5μg/ml, EXOC5 at 0.16μg/ml, EXOC6 at 0.20μg/ml, EXOC7 0.07μg/ml, EXOC8 at 0.12μg/ml, Rab11 at 0.05μg/ml, and GAPDH at 1μg/ml. Secondary antibodies were used at 1.6μg/ml.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Exocyst Complex Proteins are Expressed in the Human Placenta

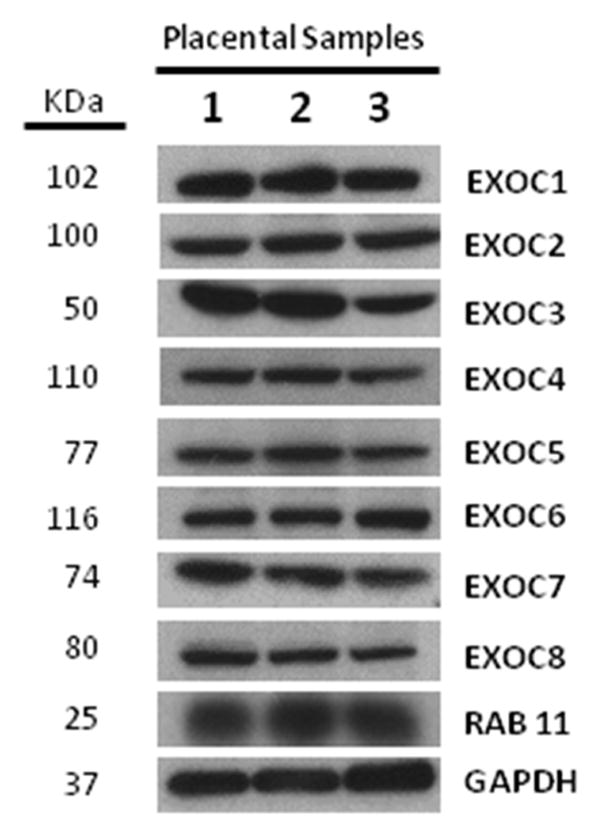

Using an immunoblot approach we set out to validate and expand our previously published data. Immunoblot analysis of equivalent amounts of tissue homogenate prepared from three distinct, normal, term placentas revealed robust expression of the entire repertoire of mammalian exocyst complex proteins, EXOC1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 (Figure 1) in the human placenta. Likewise, the EXOC6 effector, RAB11, was also detected (Figure 1). All exocyst complex proteins were similarly expressed in the discrete placenta preparations. Although the data illustrate placental exocyst protein expression, from these data alone we cannot extrapolate stoichiometry or localization. Uncropped images of EXOC1-8 and RAB11 immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Figure 1, and demonstrate antibody specificity.

Figure 1. Exocyst complex proteins are expressed in the human placenta.

Immunoblots (IB) showing expression of exocyst complex and associated proteins in the human placenta. Equivalent amounts of placenta samples (PS) from three different normal, term placentas (PS 1, 2, and 3) were separated and analyzed by SDS-Page and IB. The lanes labeled 1, 2, and 3 correspond with PS 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The IBs were probed with antibodies against EXOC 1 or, 2 or, 3 or, 4 or, 5 or, 6 or, 7 or, 8, or RAB11. All eight of the exocyst complex proteins as well as RAB11 were expressed in the three PS. To illustrate that a similar amount of protein was resolved and transferred, anti-GAPDH antibody was used as a loading control.

3.2 The Exocyst and associated proteins are robustly expressed in the syncytiotrophoblast cell layer

Having confirmed the expression of the mammalian exocyst proteins in placental samples, we next sought to ascertain the localization and expression pattern of the individual exocyst components. Progenitor, mononuclear CTBs fuse and differentiate into a multinucleated, continuous STB cell layer. As the STB is a major site of hormone secretion, of particular interest were differences in exocyst expression between CTBs and the STB. To that end, we conducted an immunobiological survey of numerous term placental samples utilizing immunofluorescent labeling and confocal microscopy. In the human placenta, E-cadherin (CDH1) demarcates the boundary between CTBs and STB [29]. CTBs are largely encapsulated by CDH1 while the STB cell layer lies above both the CTBs and the CDH1 boundary (Figure 2–4). Using the CDH1 boundary as a landmark, we documented differences in exocyst protein expression in CBTs and the STB.

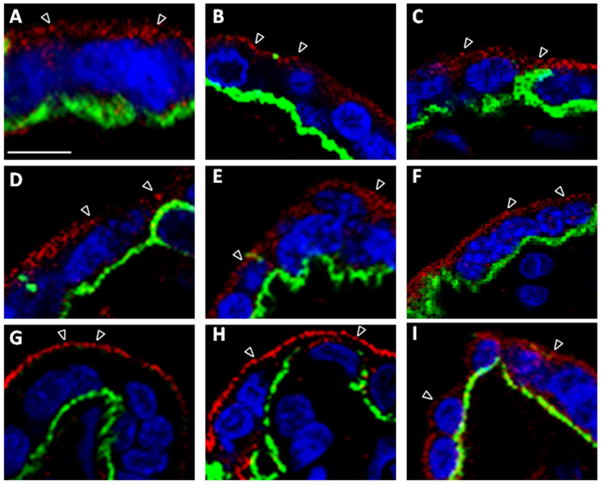

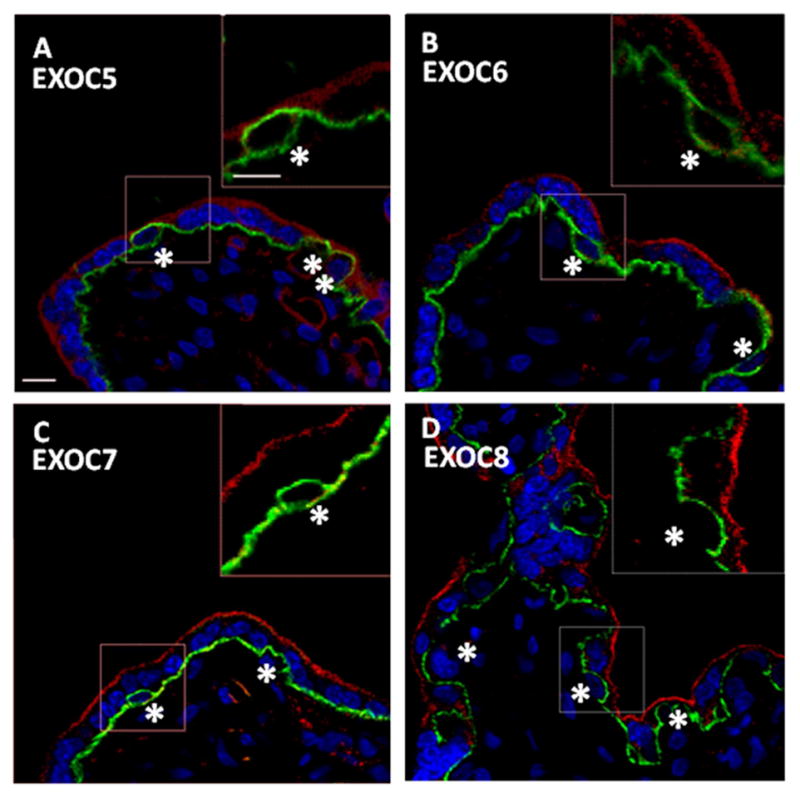

Notably, all eight of the exocyst proteins exhibited similar localization within the placenta, showing pronounced labeling in the STB while little, if any, was observed in progenitor CTBs (Figure 2 and 3). Higher magnification images revealed that EXOC1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and RAB11 were primarily associated with vesicle-like structures throughout the STB cytoplasm, while EXOC7 and 8 also exhibited a distinct enrichment at or near the apical PM (Figure 5). Additionally, the exocyst proteins were observed in the STB of stem, intermediate, and terminal villi alike (data not shown). Lower magnification survey micrographs showing the distribution of EXOC1, 2, 3, and 4 (Supplementary Figure 2) and EXOC5, 6, 7, and 8 (Supplementary Figure 3) are also presented. Likewise, RAB11 exhibited staining within the STB cell layer, with little, if any, expression in CTBs (Figure 4). Within the STB, RAB11 labeling was reminiscent of exocyst protein distribution, yielding a similar punctuate organization throughout the STB cytosol (Figure 5). RAB11 localized in the STB of the various types of villi as well, and its distribution in a lower magnification survey micrograph is presented as well (Supplementary Figure 4). The exocyst proteins and RAB11 were also detected in some interstitial cells of the placenta, though at an apparent lower level of expression than in the STB (Supplementary Figures 2–4).

Figure 3. EXOC5, 6, 7, and 8 expression and localization in the human placenta.

A–D. Confocal images of EXOC5, 6, 7, and 8 in human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slices. Exocyst and CDH1 protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. CTBs are indicated by an asterisk. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. Dashed boxes distinguish ROI. Insets are a 3X digital zoom of associated ROI; the insets show only the red and green channels. A. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC5 and CDH1 localization; Inset exhibits EXOC5 STB localization. B. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC6 and CDH1 localization; Inset exhibits EXOC6 STB localization. C. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC7 and CDH1 localization; Inset exhibits EXOC7 STB localization. D. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC8 and CDH1 localization; Inset exhibits EXOC8 STB localization. Exocyst protein expression was localized throughout the STB, with little, if any, expression observed in CTBs. Additionally, EXOC7 and 8 appear enriched at or near the apical plasma membrane. Little, if any, expression of exocyst proteins was observed in CTBs. Scale bars=10μm.

Figure 5. Syncytiotrophoblast exocyst complex protein localization.

A–I. Higher magnification confocal images of Exoc 1–8 and RAB11distribution within the STB cell layer, shown as single representative optical slices. Exocyst and CDH1 protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. Arrowheads denote exocyst protein puncta within the STB. Exocyst proteins are localized within the STB cytoplasm in vesicle-like structures (arrowheads). Exoc7 and 8 appear enriched at or near the apical PM. A. Exoc1 and CDH1 B. Exoc2 and CDH1, C. Exoc3 and CDH1, D. Exoc4 and CDH1, E. Exoc5 and CDH1, F. Exoc6 and CDH1, G. Exoc7 and CDH1, H. Exoc8 and CDH1, and I. RAB11 and CDH1. Scale bar=10μm

In addition to the labeling of EXOC2 and 4 in the STB and interstitial cells, we also observed additional fluorescence associated with the endothelium (Supplementary Figure 2). While the STB labeling of EXOC2 and 4 was specific as confirmed by preimmune and secondary antibody controls (Supplementary Figure 5), the signal from the endothelium may represent non-specific staining. It is known that, for reasons not presently understood, the endothelium in the human placenta non-specifically binds the mouse IgG subclass IgG2b [30]. We have likewise confirmed this to occur in our tissue samples, as incubation with preimmune mouse IgG, containing IgG2b, resulted in labeling of the endothelium but not other cell types in the human placenta (Supplementary Figure 5). This preimmune mouse IgG contains a mixture of IgG subclasses, including IgG2b.

4. DISCUSSION

The basis of placental function is developmentally regulated cellular differentiation. Mononuclear CTBs initiate human placental development and serve as STB progenitor cells. CTBs continuously fuse throughout gestation to form and maintain the multinucleated, terminally differentiated STB. As CTBs fuse and differentiate into STB, cellular metabolism and protein production is dramatically augmented. The STB not only serves as the interface of maternal/fetal nutrient and gas exchange but also is a major site of hormone production and secretion, such as human chorionic gonadotropin (CG). As part of normal physiology, STB differentiation results in increases in protein production, vesicular trafficking, and polarized secretion. In order to accommodate this rise in protein production and ensure the fidelity of hormone secretion, trophoblast cells must amplify mechanisms of vesicular trafficking.

Although polarized secretion is a fundamental element of placental biology, our understanding of this process remains incomplete. The exocyst complex is known to be a master regulator of secretion via its control of vesicular trafficking and fusion, and here we report, for the first time, the expression of the exocyst complex proteins, EXOC 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, in normal human placenta (Figure 1). We also find that the placenta expresses an important exocyst effector protein, RAB11 (Figure 1).

Immunofluorescence labeling revealed a remarkable pattern of exocyst protein localization within the placenta. Significantly, exocyst proteins were robustly detected throughout the STB but little, if any, was detected within CTBs, suggesting that in the placenta, exocyst complex expression is regulated during trophoblast differentiation. Considering the exocyst’s classical role in secretion, it seems hardly coincidental that its localization and expression is developmentally regulated within the placenta, and strongly suggests that exocyst protein expression correlates with dramatic changes in secretory function that accompanies STB differentiation (Figures 2 and 3). Although the exocyst complex is found in organisms ranging from yeast to mammals, our findings are noteworthy with regard to placental development and function based on 1) the regulation of exocyst protein expression with respect to trophoblast differentiation and 2) its localization within the STB.

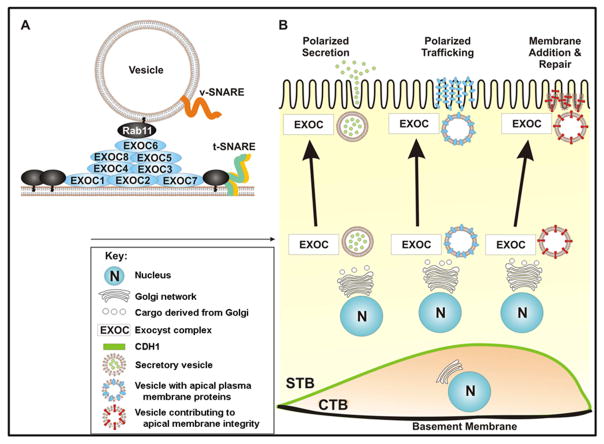

We hypothesize that the exocyst plays a pivotal role in placental function; a figure illustrating these hypothetical functions is presented (Figure 6). Exocyst protein expression is likely upregulated in fused trophoblast cells in part to accommodate increases in peptide hormone secretion [31]. Aberrant trophoblast cell processes are also implicated in placental diseases such as preeclampsia (PE) [32, 33], and elevated CG secretion has been reported in PE [33]. The mechanism of this misregulation remains unclear. In light of our current data, we propose that in addition to its role in normal placental physiology, the exocyst complex may also be affected in pathophysiological conditions, like PE. While exocyst function in healthy and diseased placentas remains to be compared, analysis of its role in placental secretion warrants future investigation.

Figure 6. Model of hypothetical exocyst functions in the syncytiotrophoblast cell layer of the human placenta.

A. Cartoon of exocyst complex assembly in the STB cell layer of the human placenta between a cargo vesicle and the plasma membrane. Black ovals represent small GTPase molecular switches associated with the plasma membrane and secretory vesicles. Vesicle (v) and target (t) SNARES are symbolized as orange, yellow and green lines. Exocyst complex assembly is thought to be a sequential process. EXOC1 and 7 interact with dynamic regions along the apical PM and facilitate t-SNARE formation. EXOC1 and 7 interact with PM GTPases which remodels the cortical actin cytoskeleton in preparation for vesicle delivery. Concomitantly, secretory vesicles accumulate v-SANREs and RAB11 as they mature. GTP bound RAB11 engages EXOC6, and together recruit EXOC2, 3, 4, 5, and 8. This pre-complex associates with microtubules and arrives at the PM to couple with EXOC1 and 7. Complex formation facilitates v/tSNARE interactions required for vesicle exocytosis. Cartoon adapted from He, B. and Guo W. [44]. B. Model of potential exocyst functions in the human placenta. Exocyst proteins are developmentally regulated, as they are robustly expressed in the STB cell layer, but not in CTBs. The exocyst facilitates vesicular trafficking, tethering, and fusion, while the nuances of its function are in the details of cargo destination and variety. The exocyst complex may serve a more classic role as exocytic regulator, comprising a new mechanism of placental peptide hormone secretion. Additionally, the exocyst complex may affect trophoblast function through its more recently described roles in cell polarity and membrane growth and repair.

The exocyst complex may also have additional STB specific functions. In recent years, the exocyst complex has been highlighted as indispensible in a wide array of cellular processes, many of which are of note to placental development and function. Of particular interest are the exocyst’s more recently described roles in 1) cell polarity and 2) membrane growth [17, 34–37]. Exocyst regulated polarity and growth rely on the same tenets as secretion: vesicular trafficking, tethering, and fusion (Figure 6). However, the nuances of various exocyst functions are in the components of differential cargos and targeted transport of these cargos to localized exocyst complexes. Exocyst escorted vesicles are sorted throughout the cell and can subsequently fuse with either the apical or basal PM for the establishment and maintenance of cell polarity and PM growth, as in the case of primary cilia formation and neurite branching (Figure 6) [34, 36, 38]. The placenta is an organ that undergoes extensive growth and continual repair. While fusion of the cytotrophoblasts with the basal STB membrane contributes directly to the expansion of this plasma membrane, a similar direct contribution to the expansion of the apical membrane is not likely since the basal and apical membranes are not linked by a lateral plasma membrane in the STB. Thus, as the polarized apical PM must increase in mass during the course of pregnancy, the material and machinery by which these events occur are likely STB derived and contained. It has been estimated that at term the apical PM of the STB occupies an area of 90m2 [39]. Given these non-classical functions and localization within the STB, in addition to its role in secretion, we hypothesize that the exocyst is also an essential element of STB polarization and PM addition (Figure 6).

Throughout gestation, the apical PM of the STB is a site of membrane turnover, and PM integrity is central to placental function. Continual membrane addition is required not only to support the expansion of the growing STB apical membrane, but also to offset the loss of apical plasma membrane due to the shedding of syncytial knots. The exocyst complex may play a role in these processes by directing the delivery of vesicle bound phospholipids or membrane repair machinery to dynamic sites along the apical PM, thereby facilitating membrane growth and mending (Figure 6). PE placentas exhibit increased syncytial knot shedding [40], in part due to disrupted apical PM integrity [41–43]. Exocyst complex misregulation may also contribute to this pathological condition as a result of impaired membrane maintenance.

The discovery of the exocyst proteins in the human STB provides new and exciting possibilities in placental biology. Importantly, the exocyst’s regulatory role in cellular processes that affect trophoblast function lends a fresh perspective to ongoing research. As the functional role of the exocyst in placental biology remains entirely unexplored, numerous possibilities for future study present themselves.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Immunoblot exocyst complex antibody specificity. Representative exocyst complex and accessory protein immunoblot data showing the entire uncropped image. Lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 correspond to anti-EXOC1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and RAB11 immunoblot data, respectively. Individual columns represent the entirety of separated proteins per lane, subsequently probed with the indicated primary and secondary HRP-antibodies. A single band was observed for seven of the nine proteins monitored in this study. In blots probed with anti-EXOC5 and 6 antibodies, a lower molecular weight band (marked with brackets), was observed in addition to the band corresponding to a protein of the expected molecular weight.

A-D. Lower magnification survey confocal images of EXOC1, 2, 3, and 4 in human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slices. Exocyst and CDH1 protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. CDH1 labeling demarcates the boundary between CTBs and the STB cell layer. CTBs are largely encapsulated by CDH1, and are indicated by an asterisk. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. A. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC1 and CDH1 localization. B. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC2 and CDH1 localization. C. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC3 and CDH1 localization. D. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC4 and CDH1 localization. Exocyst proteins were expressed throughout the human placenta. Interstitial cells exhibit some exocyst labeling, while the majority of the exocyst signal was found throughout the STB cell layer. Scale bar=20μm.

A-D. Lower magnification survey confocal images of EXOC5, 6, 7, and 8 in human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slices. Exocyst and CDH1 protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. CTBs are indicated by an asterisk. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. A. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC5 and CDH1 localization. B. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC6 and CDH1 localization. C. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC7 and CDH1 localization. D. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC8 and CDH1 localization. Exocyst proteins were expressed throughout the human placenta. Interstitial cells exhibit some exocyst labeling, while the majority of the exocyst signal was found throughout the STB cell layer. Scale bar=20μm.

Lower magnification survey confocal image of RAB11 in human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slice. RAB11 and CDH1 protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. CTBs are indicated by an asterisk. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. Single optical slice representing placental RAB11 and CDH1 localization. RAB11 was expressed throughout the human placenta. Interstitial cells exhibit moderate RAB11 labeling, with the majority of the signal found throughout the STB cell layer. RAB11 was expressed in the STB of the different types of villi which comprise the human placenta. Scale bar=20μm.

A-D. Confocal images of control human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slices. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. A. Preimmune Goat IgG B. Preimmune Rabbit IgG C. Preimmune Mouse IgG D. Secondary antibodies alone. Labeling of the endothelium was observed in tissues incubated with mouse IgG, likely due to IgG2b nonspecific binding as previously reported [30]. Scale bar=10μm.

HIGHLIGHTS.

The exocyst complex is a master regulator of mammalian secretion.

For the first time, we examine the expression and localization of the exocyst in the human placenta.

Exocyst proteins are expressed in the syncytiotrophoblast, but not by cytotrophoblast cells.

Exocyst protein expression appears to be regulated during trophoblast differentiation.

Exocyst expression, provides insight into new mechanism of placental secretion and development.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Departments of 1) Physiology and Cell Biology and 2) Obstetrics and Gynecology and the 3) Campus Microscopy and Imaging Facility at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. We also acknowledge the technical support provided by Jason Benedict.

Grant Support

This work was supported in part by NIH grant HD058084 (JMR). No additional external funding was received for this study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- STB

Syncytiotrophoblast

- CTB

Cytotrophoblast

- EXOC

Exocyst Complex Component

- CDH1

E-cadherin

- PM

Plasma Membrane

- CG

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin

- PE

Pre-eclampsia

Footnotes

Individual contributions

This work was carried out as a full collaboration among all the authors listed. JMR and DDV defined the research topic. IMG performed all the experiments. JMR, DDV, WEA, and IMG designed and analyzed all experiments and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial disclosure

None

Conflict of Interest

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

I.M. Gonzalez, Email: gonzalez.394@osu.edu.

W.E. Ackerman, IV, Email: ackerman.72@osu.edu.

D.D. Vandre, Email: Dale.Vandre@med.wmich.edu.

References

- 1.Liu J, Guo W. The exocyst complex in exocytosis and cell migration. Protoplasma. 2012;249(3):587–97. doi: 10.1007/s00709-011-0330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heider MR, Munson M. Exorcising the exocyst complex. Traffic. 2012;13(7):898–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novick P, Field C, Schekman R. Identification of 23 complementation groups required for post-translational events in the yeast secretory pathway. Cell. 1980;21(1):205–15. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inoue M, Chang L, Hwang J, Chiang SH, Saltiel AR. The exocyst complex is required for targeting of Glut4 to the plasma membrane by insulin. Nature. 2003;422(6932):629–33. doi: 10.1038/nature01533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamo JE, Moskow JJ, Gladfelter AS, Viterbo D, Lew DJ, Brennwald PJ. Yeast Cdc42 functions at a late step in exocytosis, specifically during polarized growth of the emerging bud. J Cell Biol. 2001;155(4):581–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adamo JE, Rossi G, Brennwald P. The Rho GTPase Rho3 has a direct role in exocytosis that is distinct from its role in actin polarity. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10(12):4121–33. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo W, Tamanoi F, Novick P. Spatial regulation of the exocyst complex by Rho1 GTPase. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(4):353–60. doi: 10.1038/35070029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(8):513–25. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Zuo X, Yue P, Guo W. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate mediates the targeting of the exocyst to the plasma membrane for exocytosis in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(11):4483–92. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-05-0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He B, Xi F, Zhang X, Zhang J, Guo W. Exo70 interacts with phospholipids and mediates the targeting of the exocyst to the plasma membrane. EMBO J. 2007;26(18):4053–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baek K, Knodler A, Lee SH, Zhang X, Orlando K, Zhang J, Foskett TJ, Guo W, Dominguez R. Structure-function study of the N-terminal domain of exocyst subunit Sec3. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(14):10424–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamashita M, Kurokawa K, Sato Y, Yamagata A, Mimura H, Yoshikawa A, Sato K, Nakano A, Fukai S. Structural basis for the Rho- and phosphoinositide-dependent localization of the exocyst subunit Sec3. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(2):180–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whyte JR, Munro S. Vesicle tethering complexes in membrane traffic. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 13):2627–37. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.13.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grote E, Carr CM, Novick PJ. Ordering the final events in yeast exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;151(2):439–52. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pfeffer SR. Transport vesicle docking: SNAREs and associates. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:441–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu H, Turner C, Gardner J, Temple B, Brennwald P. The Exo70 subunit of the exocyst is an effector for both Cdc42 and Rho3 function in polarized exocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(3):430–42. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupraz S, Grassi D, Bernis ME, Sosa L, Bisbal M, Gastaldi L, Jausoro I, Caceres A, Pfenninger KH, Quiroga S. The TC10-Exo70 complex is essential for membrane expansion and axonal specification in developing neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29(42):13292–301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3907-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cai H, Reinisch K, Ferro-Novick S. Coats, tethers, Rabs, and SNAREs work together to mediate the intracellular destination of a transport vesicle. Dev Cell. 2007;12(5):671–82. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi S, Kubo K, Waguri S, Yabashi A, Shin HW, Katoh Y, Nakayama K. Rab11 regulates exocytosis of recycling vesicles at the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 17):4049–57. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grosshans BL, Ortiz D, Novick P. Rabs and their effectors: achieving specificity in membrane traffic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(32):11821–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang XM, Ellis S, Sriratana A, Mitchell CA, Rowe T. Sec15 is an effector for the Rab11 GTPase in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(41):43027–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu S, Mehta SQ, Pichaud F, Bellen HJ, Quiocho FA. Sec15 interacts with Rab11 via a novel domain and affects Rab11 localization in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12(10):879–85. doi: 10.1038/nsmb987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jafar-Nejad H, Andrews HK, Acar M, Bayat V, Wirtz-Peitz F, Mehta SQ, Knoblich JA, Bellen HJ. Sec15, a component of the exocyst, promotes notch signaling during the asymmetric division of Drosophila sensory organ precursors. Dev Cell. 2005;9(3):351–63. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S, Hsu SC. The molecular mechanisms of the mammalian exocyst complex in exocytosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34(Pt 5):687–90. doi: 10.1042/BST0340687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carr CM, Grote E, Munson M, Hughson FM, Novick PJ. Sec1p binds to SNARE complexes and concentrates at sites of secretion. J Cell Biol. 1999;146(2):333–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vandre DD, Ackerman WEt, Tewari A, Kniss DA, Robinson JM. A placental sub-proteome: the apical plasma membrane of the syncytiotrophoblast. Placenta. 2012;33(3):207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson JM, Ackerman WEt, Tewari AK, Kniss DA, Vandre DD. Isolation of highly enriched apical plasma membranes of the placental syncytiotrophoblast. Anal Biochem. 2009;387(1):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lang CT, Markham KB, Behrendt NJ, Suarez AA, Samuels P, Vandre DD, Robinson JM, Ackerman WEt. Placental dysferlin expression is reduced in severe preeclampsia. Placenta. 2009;30(8):711–8. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longtine MS, Chen B, Odibo AO, Zhong Y, Nelson DM. Villous trophoblast apoptosis is elevated and restricted to cytotrophoblasts in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia, IUGR, or preeclampsia with IUGR. Placenta. 2012;33(5):352–9. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honig A, Rieger L, Kapp M, Dietl J, Kammerer U. Immunohistochemistry in human placental tissue--pitfalls of antigen detection. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53(11):1413–20. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6664.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boime ILT, McQueen S, McWilliams D. In: The biosynthesis of chorionic gonadotropin and placental lactogen in first- and third-trimester human placenta. McKerns KW, editor. New York: Springer US; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meekins JW, Pijnenborg R, Hanssens M, McFadyen IR, van Asshe A. A study of placental bed spiral arteries and trophoblast invasion in normal and severe pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101(8):669–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1994.tb13182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hutcheon JA, Lisonkova S, Joseph KS. Epidemiology of pre-eclampsia and the other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25(4):391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lalli G, Hall A. Ral GTPases regulate neurite branching through GAP-43 and the exocyst complex. J Cell Biol. 2005;171(5):857–69. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.TerBush DR, Novick P. Sec6, Sec8, and Sec15 are components of a multisubunit complex which localizes to small bud tips in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1995;130(2):299–312. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grindstaff KK, Yeaman C, Anandasabapathy N, Hsu SC, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Scheller RH, Nelson WJ. Sec6/8 complex is recruited to cell-cell contacts and specifies transport vesicle delivery to the basal-lateral membrane in epithelial cells. Cell. 1998;93(5):731–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeaman C, Grindstaff KK, Nelson WJ. Mechanism of recruiting Sec6/8 (exocyst) complex to the apical junctional complex during polarization of epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 4):559–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zuo X, Guo W, Lipschutz JH. The exocyst protein Sec10 is necessary for primary ciliogenesis and cystogenesis in vitro. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(10):2522–9. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teasdale F, Jean-Jacques G. Morphometric evaluation of the microvillous surface enlargement factor in the human placenta from mid-gestation to term. Placenta. 1985;6(5):375–81. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(85)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Redman CW, Sargent IL. Circulating microparticles in normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 2008;29(Suppl A):S73–7. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones CJ, Fox H. Syncytial knots and intervillous bridges in the human placenta: an ultrastructural study. J Anat. 1977;124(Pt 2):275–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson WR, McKay DG. Electron microscope study of the trophoblast in normal and toxemic placentas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1966;95(8):1134–48. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(66)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones CJ, Fox H. An ultrastructural and ultrahistochemical study of the human placenta in maternal pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 1980;1(1):61–76. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(80)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He B, Guo W. The exocyst complex in polarized exocytosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21(4):537–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Immunoblot exocyst complex antibody specificity. Representative exocyst complex and accessory protein immunoblot data showing the entire uncropped image. Lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 correspond to anti-EXOC1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and RAB11 immunoblot data, respectively. Individual columns represent the entirety of separated proteins per lane, subsequently probed with the indicated primary and secondary HRP-antibodies. A single band was observed for seven of the nine proteins monitored in this study. In blots probed with anti-EXOC5 and 6 antibodies, a lower molecular weight band (marked with brackets), was observed in addition to the band corresponding to a protein of the expected molecular weight.

A-D. Lower magnification survey confocal images of EXOC1, 2, 3, and 4 in human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slices. Exocyst and CDH1 protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. CDH1 labeling demarcates the boundary between CTBs and the STB cell layer. CTBs are largely encapsulated by CDH1, and are indicated by an asterisk. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. A. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC1 and CDH1 localization. B. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC2 and CDH1 localization. C. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC3 and CDH1 localization. D. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC4 and CDH1 localization. Exocyst proteins were expressed throughout the human placenta. Interstitial cells exhibit some exocyst labeling, while the majority of the exocyst signal was found throughout the STB cell layer. Scale bar=20μm.

A-D. Lower magnification survey confocal images of EXOC5, 6, 7, and 8 in human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slices. Exocyst and CDH1 protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. CTBs are indicated by an asterisk. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. A. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC5 and CDH1 localization. B. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC6 and CDH1 localization. C. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC7 and CDH1 localization. D. Single optical slice representing placental EXOC8 and CDH1 localization. Exocyst proteins were expressed throughout the human placenta. Interstitial cells exhibit some exocyst labeling, while the majority of the exocyst signal was found throughout the STB cell layer. Scale bar=20μm.

Lower magnification survey confocal image of RAB11 in human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slice. RAB11 and CDH1 protein labeling are shown in the red and green channel, respectively. CTBs are indicated by an asterisk. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. Single optical slice representing placental RAB11 and CDH1 localization. RAB11 was expressed throughout the human placenta. Interstitial cells exhibit moderate RAB11 labeling, with the majority of the signal found throughout the STB cell layer. RAB11 was expressed in the STB of the different types of villi which comprise the human placenta. Scale bar=20μm.

A-D. Confocal images of control human placental sections showcased as single representative optical slices. Nuclei have been labeled with DAPI and are represented in blue. A. Preimmune Goat IgG B. Preimmune Rabbit IgG C. Preimmune Mouse IgG D. Secondary antibodies alone. Labeling of the endothelium was observed in tissues incubated with mouse IgG, likely due to IgG2b nonspecific binding as previously reported [30]. Scale bar=10μm.