Abstract

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is critical for tissue regeneration. However, it is unclear how β-catenin controls stem cell behaviors to coordinate organized growth. Using live imaging, we show that activation of β-catenin specifically within mouse hair follicle stem cells generates new hair growth through oriented cell divisions and cellular displacement. β-catenin activation is sufficient to induce hair growth independently of mesenchymal dermal papilla-niche signals normally required for hair regeneration. Remarkably, wild-type cells are co-opted into new hair growths by β-catenin mutant cells, which non-cell autonomously activate Wnt signaling within the wild-type cells via Wnt ligands. This study demonstrates a mechanism by which Wnt/β-catenin signaling controls stem cell-dependent tissue growth non–cell autonomously and advances our understanding of the mechanisms that drive coordinated regeneration.

Adult tissue regeneration relies upon the coordinated activation of resident stem cells within their niches to generate a functional organ (1). The Wnt/β-catenin signaling functions in the maintenance of stem cells (SCs) of various lineages. However, it is unclear how this pathway controls specific subpopulations of cells to organize growth during tissue regeneration.

The hair follicle (HF) serves as a versatile model to address this fundamental question, because it is highly accessible and its SCs and progeny, located in the bulge and hair germ respectively, are anatomically and molecularly well-defined (Fig S1) (2–6). HF stem cell (HF-SC) progeny lie in direct contact with a specialized group of mesenchymal cells, the dermal papilla (DP), that function as a key signaling center required for epithelial-mesenchymal interactions that govern HF growth (4, 7, 8).

Wnt signaling is required for HF development and regeneration (9–17) and is mediated by the stabilization and translocation of the key signal transducer, β-catenin, to the nucleus where it binds TCF/Lef transcription factors to activate Wnt target gene transcription (18). Expression of activated β-catenin throughout the basal epidermis has been shown to induce de novo HFs within the epidermis, establishing that Wnt signaling is required and sufficient for new hair growth (13, 15–17). Although these studies illustrate the importance of Wnt/β-catenin signaling during HF regeneration, several outstanding questions remain, including 1) which dynamic SC behaviors does Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulate, 2) is Wnt/β-catenin activation sufficient to promote growth within the SC pool and independently of the mesenchymal dermal papilla and 3) what are the molecular mechanisms by which Wnt/β-catenin coordinates collective tissue growth?

To investigate HF-SC behaviors regulated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling, we genetically activated β-catenin specifically within the HF-SC/progeny using K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ mice (fig. 1A; S1). Tamoxifen induction during the HF resting phase results in β-catenin stabilization and constitutive activation of Wnt signaling with subsequent formation of new ectopic axes of hair growth that show HF differentiation (figs. 1A, S1, S2A–F). These data show that β-catenin activation specifically in HF-SC/progeny can induce new hair growths, despite previous studies that suggested that HF-SC/progeny cells might be refractory to activated β-catenin signaling relative to other epidermal keratinocytes (16, 19). In contrast to ectopic HFs that form when β-catenin is activated throughout the basal epidermis (14, 16), new hair growths in K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ mice did not harbor morphologically apparent DP structures but instead were surrounded by a layer of mesenchymal cells that expressed DP/dermal sheath markers (fig. S2G–J), consistent with previous findings (20).

Fig. 1. Activated β-catenin-induced cellular mechanisms that promote new hair growths.

(A) Hair growths in Tamoxifen-treated K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+. New hair growths are P-cadherin+ (green) and proliferative (Ki67, red). Nuclei (DAPI, blue). (B) Optical sections of z-stacks of a K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;K14-H2BGFP HF depict upward nuclear movement (Movie S2). Epithelial nuclei (K14-H2BGFP, white). Arrowheads indicate points of reference of original nuclei positions. Colored circles represent moving nuclei, black circles represent stationary nuclei. (C) Formation (c’ inset) and expansion (cc’) of nuclear clusters in two separate K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;K14-H2BGFP mice. Nuclei are pseudo-colored (Movie S3–S4). (D) K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;K14-H2BGFP HFs just after DP ablations (Day 0, yellow arrows). DPs marked by Lef1-RFP (red), epithelial nuclei by K14-H2BGFP (green). (E) Same HFs after 6 days of Tamoxifen treatment (Day 7). (F–G) Revisit of the same HFs (Day 12–19). Asterisk denotes HF out of plane of view. Scale bars=25µm.

Next, we coupled our genetic gain of function system with in vivo imaging of live mice. Time-lapse imaging of new hair growth in K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;K14-H2BGFP mice captured cell divisions that were oriented along the new axis of growth (fig. S3A–D) and displayed divergent upward displacement of epithelial nuclei toward newly forming hair growths (fig. 1B; Movie S1–2). These bud-like clusters of epithelial cells organized themselves into a compact arrangement (fig. S3E; Movie S2). To capture early changes induced by β-catenin stabilization, we began recording when mutant follicles had not yet developed new hair growths and observed epithelial nuclei clustering into ring-like structures (figs. 1C (top view) and S3E (side view); Movies S3–4), reminiscent of early stage embryonic HF formation (fig. S4)(21). These findings show that activated β-catenin orients cell divisions and organizes cell movements within SC/progeny cells to drive new axes of hair growth.

The mesenchymal dermal papilla (DP) constitutes one of the best-characterized niches for HF-SCs and their progeny and is required for their activation to initiate hair growth (8, 22, 23). Therefore, we hypothesized that native DP signals may be required parallel or downstream of activated β-catenin HF-SC/progeny cells to initiate new hair growths. To test this hypothesis, we first laser-ablated DP cells and then induced β-catenin activation in HF-SC/progeny using K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;K14-H2BGFP;Lef1-RFP mice (7). We then revisited the same ablated follicles over several days (figs. 1D–G and S5). Remarkably, the majority of β-catenin mutant HFs regrew (62%) in contrast to wild-type HFs (0%) following DP ablation (fig. S5F). Although we cannot exclude a potential requirement of a native DP for subsequent HF differentiation or that other mesenchymal cells may functionally promote hair growth in the absence of a native DP, these data demonstrate that β-catenin activation in the SC/progeny compartment is sufficient to initiate HF growth independent of mesenchymal DP niche signals.

To address the mechanism by which mutant β-catenin activated cells contribute to hair growth expansion, we labeled mutant cells using a tdTomato Cre reporter (24). Using in vivo imaging, we examined the contribution of tdTomato-positive cells (tdTom+) to the new hair growths in Tamoxifen-induced K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;K14-H2BGFP;tdTom mice. Although the initial small hair growths largely consisted of tdTom+ cells, later expanded growths were mosaic for tdTom expression, suggesting that mutant cells recruit wild-type cells to promote growth and expansion (fig. 2A–B; S6A) and are reminiscent of the mosaic contribution observed in tooth formation following β-catenin activation (25). To confirm this heterogeneity, we FACS-purified cells from growths using tdTom and P-cadherin expression, a marker enriched in these growths. FACS-purified mutant (tdTom+;P-cadhi) cells showed the expected deleted β-catenin-ΔExon3 allele by PCR (700-bp band), whereas wild-type (tdTom−;P-cadhi) cells showed only the non-recombined band (900-bp) (fig. 2C, upper gel). Similarly, FACS purification using the TcfLef-H2BGFP Wnt reporter (fig. S6B) in the K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;tdTom mice showed similar results (fig. 2C, lower gel).

Fig. 2. β-catenin activation triggers new axes composed of both mutant and wild-type cells.

(A–B) Optical sections of z-stacks of K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;K14-H2BGFP;tdTom mutant HFs show early and late hair growths (K14-H2BGFP, green; tdTom Cre-reporter, red). (C) Genotype of FACS-isolated populations from the new growths based on Pcadherin- enrichment (top gel) (n=2 mice) or TcfLef-H2BGFP Wnt reporter (bottom gel) (n=2 mice). (D) Both tdTom+ and tdTom− cells dividing within a new growth. Schematic depicts representative divisions within both tdTom+ and tdTom− populations over a time-lapse recording (see Movie S5). Scale bars=50µm.

To determine if wild-type cells functionally contribute to the expansion of mutant hair growths, we performed time-lapse recordings and immunofluorescent analysis and demonstrated that wild-type cells within the growths proliferate like co-resident β-catenin mutant cells (figs. 2D and S6C; Movie S5). These results show that β-catenin activation in a subset of HF-SC/progeny cells leads to the recruitment of wild-type epithelial cells that collectively promote coordinated hair growth expansion.

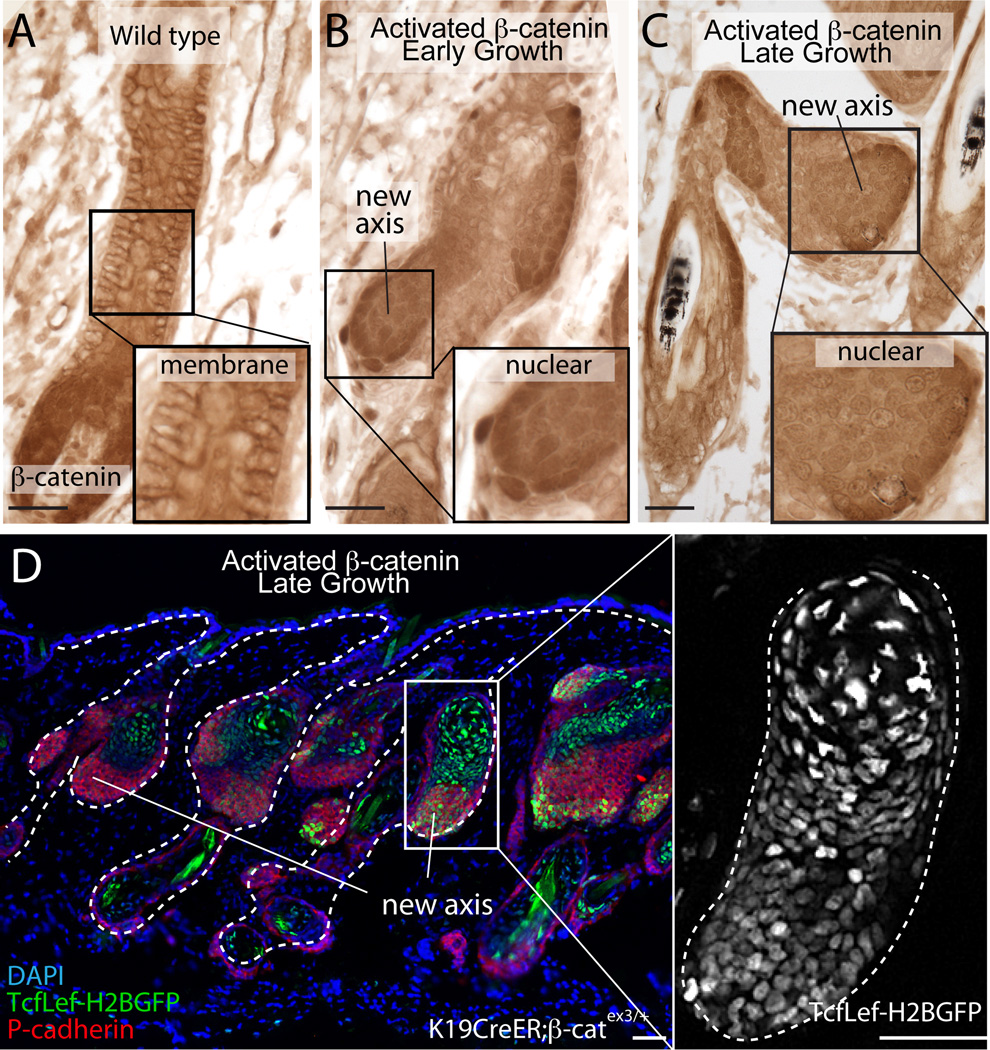

Based on the observed cellular heterogeneity, we predicted heterogeneous activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway throughout the new growths. At early stages, nuclear β-catenin was observed within the induced hair growths (fig. 3A–B). As growths expanded, nuclear β-catenin was still present globally in the new growth axes. However, clusters of cells with stronger nuclear β-catenin staining neighbored cells that exhibited weaker nuclear β-catenin staining (fig. 3C). Additionally, Tcflef-H2BGFP and Lef1 immunohistochemistry showed that Wnt active cells were observed throughout the new hair axes (figs. 3D and S6), suggesting that both activated β-catenin mutant cells and wild-type cells activate Wnt signaling.

Fig. 3. β-catenin-mutant cells activate Wnt signaling in neighboring wild-type cells.

(A) Immunohistochemistry of β-catenin in growing wild-type HF. Inset highlights membrane bound staining. (B-C) Nuclear β-catenin in new hair growths in Tamoxifen-induced K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ mice at early and late growth stages. Insets highlight nuclear staining. (D) Wnt reporter expression (TcfLef-H2BGFP, green) in late growths (P-cadherin, red). Scale bars=50µm.

To address how a mosaic population of cells can co-activate Wnt signaling, we first assessed global transcriptional changes in Wnt pathway genes by qRT-PCR from mutant and control littermate whole skin of K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ mice. Wnt target genes (Axin2, CyclinD and Lef1) and several Wnt ligands were up-regulated in β-catenin mutant skin compared to control littermates (fig. S7A), consistent with previous studies that show upregulation of Wnt ligands following β-catenin activation (26–29). To determine if β-catenin activated mutant cells specifically up-regulate Wnt ligand expression, we FACS-purified mutant cells (tdTom+;P-cadhi) and found that several Wnt ligands (Wnt3, 5a, 10b, 16), as well as a gene required for Wnt ligand secretion (Wntless), were all up-regulated compared to wild-type (tdTom−;P-cadhi) cells (fig. 4A–C). Furthermore, wild-type cells within the growths (tdTom−/P-cadHi/K14-H2BGFP+) showed higher expression of the direct down-stream Wnt target gene, Axin2, when compared to wild-type cells outside the growths (tdTom−/P-cad−/K14-H2BGFP+) (fig S7B). This shows that Wnt signaling is active in the wild-type cells inside the new hair growths when compared to remaining follicular epithelial cells. Furthermore, in situ hybridization analysis of Wnt10b and Wnt16 showed expression localized to foci within the new growths (fig. S8).

Fig. 4. β-catenin acts non cell-autonomously via Wnt ligands.

(A) Representative qRT-PCR analysis of Wnt ligands and target genes comparing sorted PcadHi;tdTom+ versus PcadHi;tdTom− populations from K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;tdTom mice (n=2; p<0.005). (B) Model of non-cell autonomous β-catenin signaling. (C) Wntless staining (red) in K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ mice. (D) Following Tamoxifen induction, H&E of K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;Wlsfl/fl mice show anagen-like stage HFs with growths of varying sizes versus (G) K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;Wlsfl/+ mutant controls which show growths with a higher frequency and larger size (n=3 experimental litters, n=7 K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;Wlsfl/fl mice). (E) Nuclear β-catenin within growths of K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;Wlsfl/fl and controls (H). (F) Wntless (red) is absent in most of the growths of K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;Wlsfl/fl compared to mutant controls (I). Nuclei (DAPI, blue). Scale bars=50µm.

Altogether, these experiments suggest a model in which mutant β-catenin cells influence wild-type cells to proliferate and contribute to the formation of new growths via Wnt ligand secretion (fig. 4B). To test whether Wnt ligand secretion by β-catenin-activated cells influences the growth of wild-type cells in a paracrine manner, we employed an in vitro culture assay. Wild-type keratinocytes showed increased proliferation when cultured in the presence of conditioned media collected from mutant β-catenin-activated cell cultures. This effect was abrogated when using conditioned media obtained from mutant β-catenin-activated cells cultured in the presence of a specific inhibitor of Wnt ligand secretion, IWP2 (fig. S9A–C). To test in vivo whether Wnt secretion contributes to the development or expansion of growths, we conditionally deleted Wntless (Wls) using K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;Wlsfl/fl mice (30). Activated β-catenin-induced hair growths were largely delayed and overall reduced in size in the absence of Wls compared to β-catenin mutant control mice (K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;Wlsfl/+) (fig. 4D–I). When larger growths were observed in the K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;Wlsfl/fl mice, they were associated with expression of Wls, suggesting that the efficiency of Wls elimination was inversely related to aberrant growth (fig. S9D–F). These data show that Wnt/β-catenin signaling acts through a non-cell autonomous mechanism to support collective cellular growth, a model that may explain previous findings of mosaic contribution to other epithelial organs. Furthermore, these results demonstrate that Wnt ligand secretion is an important down-stream mediator of β-catenin-induced non cell-autonomous tissue growth.

This study brings a more detailed understanding of how a conserved regenerative signal, Wnt/β-catenin, temporally and spatially regulates SC/progeny behaviors during tissue growth. These data highlight how a mutation in a down-stream target gene can modify the behavior of a genetic clone of cells while also co-opting surrounding wild-type cells to acquire similar behaviors. These findings hold important implications for understanding the cellular mechanisms that promote coordinated tissue growth and regeneration.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Keratin19CreER mice (31) were provided by G. Gu. β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ mice (32) were bred to K19CreER mice to generate K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ mice. K14-H2BGFP (33) and Lef1-RFP (7) transgenic mice were used for visualization of epithelial and mesenchymal cells with the 2-photon microscope. Wntlessfl/fl mice (34), TcfLef-H2BGFP (35), Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato) (tdTomato reporter line) (24) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. All procedures involving animal subjects were performed under the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Yale School of Medicine.

Experimental Treatment of Mice

For all experiments, mutant mice heterozygous for the K19CreER and β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ alleles or littermate controls were administered 1 mg tamoxifen dissolved in corn oil (TAM; Sigma) by intraperitoneal injections daily for 6 consecutive days starting at the rest phase (~ postnatal day 20, P20).

In vivo imaging

Imaging procedures followed those previously published (22). LaVision TriM Scope II (LaVision Biotec) microscope equipped with a Chameleon Vision II (Coherent) two-photon laser (940 nm for GFP and 1040 nm for RFP and tdTomato, respectively) was used to acquire z-stacks of ~90 µm (2 µm serial optical sections) at 5 minute intervals using a 20× water immersion lens (N.A. 1.0; Olympus), scanned with a field of view of 0.25 to 0.5 mm2 at 600 Hz. Mice were imaged at time points after TAM treatment as indicated. For revisits of same HFs, landmarks such as vasculature patterns and cluster organization of HFs were utilized.

Two-photon laser ablation

Laser ablation was carried out as described previously (22). Briefly, Dermal Papillae (DPs) were visualized by Lef1-RFP fluorescence. Ablations were accomplished using a 900-nm laser beam, pulsed at 30% laser power for 1s in a 10-µm2 area. Ablation parameters were adjusted according to DP depth.

Image analysis

Raw image stacks were imported into ImageJ (NIH Image) or IMARIS (BitPlane Scientific Software) for analysis. Optical planes from sequential time points were manually realigned in ImageJ or automatically aligned in IMARIS to compensate for minor tissue z-shift during the acquisition. Selected optical planes or z-projections of sequential optical sections were used to assemble time-lapse movies.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. An unpaired Student's t-test was used to analyze data sets with two groups and *p < 0.005 to **** p<0.0001 indicated a significant difference. Statistical calculations were performed using Prism (GraphPad).

Histology, immunohistochemistry and in situ

Skin was either frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound (Sakura Finetek) or 10% formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded and used for histological analysis. 10µm OCT skin sections were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature (RT) and treated as described previously (4). Paraffin embedded skin tissues were cut at 5µm. To show skin morphology, sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard protocols. Immunohistochemistry was performed by incubating sections at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies against the following: mouse anti-β-catenin (BD, 1:100), rat-anti-CD34 (eBioscience, 1:50), goat-anti-P-cadherin (R&D, 1:100), rat-anti-NCAM (Chemicon, 1:100), rabbit-anti-Vimentin (Cell Technology, 1:50), rabbit-anti-RFP (Rockland, 1:50), rabbit-anti-Wntless (Seven Hills, 1:500), rabbit-anti-Ki67 (NovoCastra, 1:300) rabbit-anti-Lef-1 (Cell Signaling, 1:100), and rat-anti-BrdU (Abcam, 1:200). To detect alkaline phosphatase activity, frozen sections were processed with the NBT-BCIP method (Roche). For brightfield immunohistochemistry, biotinylated species-specific secondary antibodies followed by detection using the ABC kit (Vector Labs) and DAB kit (Vector Labs) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In situ hybridization was performed according to standard protocols (4) using DIG-labeled antisense riboprobes. Wnt10b riboprobe construct was provided by Mayumi Ito (New York University) (36); the Wnt16 riboprobe was made by PCR (Fwd: 5’-GGGAGGATGCTCGGATGATG-3’, Rev: 5’- ACACTCTTACAGGCAGCGAC-3’). 10 µm skin sections were fixed in 4% PFA and counterstained with DAPI.

Whole mount tail staining

Tail skin was 0.05% EDTA treated overnight at room temperature followed by 2 hours at 37°C. Epidermis/HFs and dermis were separated using forceps and prepared for staining as described previously (37). The epidermis/HF layer was fixed overnight with 4% PFA, washed the morning after and processed for staining as indicated for OCT sections above.

FACS isolation

Back skins of K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;tdTomato; or K19CreER;β-catnflox(Ex3)/+;TcfLef-H2BGFP mice were harvested 6–10 days after TAM treatment and treated with 0.25% trypsin at 37°C for 2 hours to obtain epithelial cells as previously described (30). Cells were stained for 10 minutes with biotinylated rabbit-anti-P-cadherin (R&D, 1:250), washed for 5 minutes and then incubated with streptavidin-APC (1:100). Epidermal cells containing activated β-catenin were isolated based on DAPI exclusion, tdTomato, GFP and P-cadherin levels using a FACSAria II Cell Sorter (BioScience). Cells were sorted into either RNA lysis buffer for RNA (RNease Plus Micro Kit, Qiagen) or PBS for DNA extraction, respectively.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA from FACS-isolated cells was isolated from sorted cells using the RNeasy Plus Micro Kit (Qiagen) and quantified. After quantification RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). cDNA levels were equalized across samples. Using the ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR system (Invitrogen – Life Technologies), qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate with SYBER Green I reagents (Invitrogen) using 4.5–5.0ng cDNA per 10µl reaction. Data were analyzed by ViiA™ software and Microsoft Excel and PRISM. Gene-specific primers were designed and are listed in Table S1.

Genotyping for β-catenin mutant allele

DNA was extracted from FACS-sorted cells using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR using primers specific for β-catenin sequences flanking the exon 3 region were used to detect either the wild-type/unrecombined allele (900 bp; Fwd: 5’-GGTAGTGGTCCCTGCCCTTGACAC-3’, Rev: 5’-CTAAGCTTGGACGTAAACTC-3’) or the recombined allele (~700 bp: Fwd: 5’-GGTAGGTGAAGCTCAGCGCAGAGC-3’, Rev: 5’-ACGTGTGGCAACTTCCGCGTCATCC-3’) from equivalent amounts of DNA per sorted population.

In vitro conditioned media assay

IWP-2 (Stemgent) was reconstituted in DMSO following manufacturer’s protocol. DMSO was used as a vehicle control in matching concentrations. Wild-type keratinocytes (2×105cells/6-well) were transfected with K14ΔNβ-catenin (16) and mCherry constructs using FuGENE Transfection Reagents (Promega) following standard protocols. To inhibit Wnt ligand secretion by K14ΔNβ-catenin-transfected cells, media was removed from transfectants, which were then cultured with IWP2 (2.0–5.0mM) or vehicle. Conditioned media was collected 48hrs after the addition of IWP2, sterile-filtered (0.22µm) and added to wild-type keratinocytes (plated 24 hrs prior) in 12-well dishes (6×104 cells/well). All wild-type media was removed prior to the addition of IWP2 or vehicle-treated conditioned media. Proliferation was assayed 24 after addition of conditioned media via manual counting with a hemocytometer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Ito, J. Lim, K. Politi, A. Habermann and D. Gonzalez for insights and equipment, E. Fuchs for the K14ΔNβ-catenin construct and K14-H2BGFP;Lef1-RFP mice, G. Gu for K19CreER and M. Taketo for β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ mice. Supported by grants to V.G. by the American Cancer Society, Yale Spore, and NIH/NCI 1RO1AR063663-01. E.D. was supported by the YSCC Lo Fellowship and CMB Training Grant. P.R. and G.Z. are NYSCF–Druckenmiller Fellows. MTA: K14ΔNβ-catenin construct, K14-H2BGFP;Lef1-RFP mice, and β-catnflox(Ex3)/+ mice.

Footnotes

We declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material:

Material and Methods

Figures S1–S9

Movies S1–S5

Table S1

Author Contributions

References (31–37)

Author Contribution: E.D. and P.M. contributed equally to this work. E.D., P.M. and V.G. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. P.R. assisted in two-photon ablation experiments. G.Z. designed primers for qRT-PCR and experimental troubleshooting. I.S. set up the mouse colonies and staining protocols. T.Y.S. performed the in situ. M.T. provided β-cateninflox(Ex3)/+ mice.

References

- 1.Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Cell. 2008;132:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rompolas P, Greco V. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotsarelis G, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Cell. 1990;61:1329–1337. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90696-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greco V, et al. Cell stem cell. 2009;4:155–169. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, Polak L, Fuchs E. Cell. 2004;118:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oshima H, et al. Cell. 2001;104:233–245. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rendl M, Lewis L, Fuchs E. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahoda CA, Horne KA, Oliver RF. Nature. 1984;311:560–562. doi: 10.1038/311560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millar SE, et al. Dev Biol. 1999;207:133–149. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andl T, Reddy ST, Gaddapara T, Millar SE. Dev Cell. 2002;2:643–653. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DasGupta R, Rhee H, Fuchs E. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:331–344. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huelsken J, et al. Cell. 2001;105:533–545. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowry WE, et al. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1596–1611. doi: 10.1101/gad.1324905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva-Vargas V, et al. Dev Cell. 2005;9:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo Celso C, Prowse DM, Watt FM. Development. 2004;131:1787–1799. doi: 10.1242/dev.01052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gat U, DasGupta R, Degenstein L, Fuchs E. Cell. 1998;95:605–614. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Mater D, Kolligs FT, Dlugosz AA, Fearon ER. Genes & Dev. 2003;17:1219–1224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1076103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Amerongen R, Nusse R. Development. 2009;136:3205–3214. doi: 10.1242/dev.033910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker CM, Verstuyf A, Jensen KB, Watt FM. Dev Biol. 2010;343:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins CA, Kretzschmar K, Watt FM. Development. 2011;138:5189–5199. doi: 10.1242/dev.064592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devenport D, Fuchs E. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1257–1268. doi: 10.1038/ncb1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rompolas P, et al. Nature. 2012;487:496–499. doi: 10.1038/nature11218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chi WY, Enshell-Seijffers D, Morgan BA. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2010;130:2664–2666. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Madisen L, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang XP, et al. Development. 2009;136:1939–1949. doi: 10.1242/dev.033803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, et al. Development. 2008;135:2161–2172. doi: 10.1242/dev.017459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu F, et al. Dev Biol. 2008;313:210–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narhi K, et al. Development. 2008;135:1019–1028. doi: 10.1242/dev.016550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tortelote GG, et al. Dev Biol. 2013;374:164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myung PS, Takeo M, Ito M, Atit RP. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Means AL, Xu Y, Zhao A, Ray KC, Gu G. Genesis. 2008;46:318–323. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harada N, Tamai Y, Ishikawa T, Sauer B, Takaku K, Oshima M, Taketo MM. The EMBO Journal. 1999;18:5931–5942. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tumbar T, et al. Science. 2004;303:359–363. doi: 10.1126/science.1092436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carpenter AC, Rao S, Wells JM, Campbell K, Lang RA. Genesis. 2010;48:554–558. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrer-Vaquer A, Piliszek A, Tian G, Aho RJ, Dufort D, Hadjantonakis AK. BMC Dev Biol. 2010;10:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabbani P, et al. Cell. 2011;145:941–955. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun KM, et al. Development. 2003;130:5241–5255. doi: 10.1242/dev.00703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.