Abstract

Prenatal administration of dexamethasone causes hypertension in rats when they are studied as adults. Although an increase in tubular sodium reabsorption has been postulated to be a factor programming hypertension, this has never been directly demonstrated. The purpose of this study was to examine whether prenatal programming by dexamethasone affected postnatal proximal tubular transport. Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were injected with intraperitoneal dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg) daily for 4 days between the 15th and 18th days of gestation. Prenatal dexamethasone resulted in an elevation in systolic blood pressure when the rats were studied at 7–8 wk of age compared with vehicle-treated controls: 131 ± 3 vs. 115 ± 3 mmHg (P < 0.001). The rate of proximal convoluted tubule volume absorption, measured using in vitro microperfusion, was 0.61 + 0.07 nl·mm−1·min−1 in control rats and 0.93 + 0.07 nl·mm−1·min−1 in rats that received prenatal dexamethasone (P < 0.05). Na+/H+ exchanger activity measured in perfused tubules in vitro using the pH-sensitive dye BCECF showed a similar 50% increase in activity in proximal convoluted tubules from rats treated with prenatal dexamethasone. Although there was no change in abundance of NHE3 mRNA, the predominant luminal proximal tubule Na+/H+ exchanger, there was an increase in NHE3 protein abundance on brush-border membrane vesicles in 7- to 8-wk-old rats receiving prenatal dexamethasone. In conclusion, prenatal administration of dexamethasone in rats increases proximal tubule transport when rats are studied at 7–8 wk old, in part by stimulating Na+/H+ exchanger activity. The increase in proximal tubule transport may be a factor mediating the hypertension by prenatal programming with dexamethasone.

Keywords: NHE3, in vitro microperfusion, volume absorption, acidification

PRENATAL INSULTS leading to small-for-gestational age infants has been shown to result in hypertension in adults as first described by Barker et al. (10). A number of prenatal manipulations in a variety of animal species have resulted in hypertension in animals when studied as adults. (52). In previous studies, our laboratory has shown that prenatal dexamethasone programmed hypertension in rats when administered during a window of vulnerability between 15 and 18 days of gestation (35). In these rats, there was no difference in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) between the vehicle- and dexamethasone-treated animals to explain the hypertension.

The cause for the increase in blood pressure by prenatal programming is unknown. There is indirect evidence that there may be altered tubular sodium transport to mediate the hypertension. Maternal low-protein diet has been demonstrated to increase the renal α1- and β1-subunit mRNA abundance of the Na+/K+-ATPase in the offspring compared with controls (17). Maternal dietary protein deprivation also increases renal bumetanide-sensitive Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl− cotransporter mRNA and protein abundance in the offspring (31). In addition, the hypertension in rats that are the product of dietary protein deprivation responds to dietary sodium deprivation (33). However, altered sodium transport by prenatal programming has never been directly demonstrated.

The purpose of the present study was to examine directly whether prenatal programming alters sodium transport. To this end, we examined prenatal programming in rats by administering prenatal dexamethasone on proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) transport and Na+/H+ exchanger activity in postnatal rat tubules perfused in vitro. Our studies provide evidence that prenatal dexamethasone can have lasting effects on proximal tubular transport, which may be a factor mediating altered sodium handling and hypertension.

METHODS

Animals

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats received either vehicle or dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg body wt) by intraperitoneal injection daily between the 15th and 18th days of gestation. Our group has previously shown that this is the window during gestation when administration of dexamethasone resulted in hypertension in offspring (35, 36). Rats from multiple litters were studied in each protocol. Rats were 7–8 wk of age for these studies except for the in vitro microperfusion studies, for which they were at least 24 days of age and were weaned. Our laboratory has previously shown that NHE3 mRNA and protein abundance are at the adult level at this age (44). Rats older than 6 wk are unsuitable for in vitro microperfusion, because they develop interstitial fibrosis and a significant length of tubule cannot be dissected. These studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Measurement of blood pressure

Blood pressure was measured in rats at ~2 mo of age with an IITC model 179 blood pressure analyzer (Woodland Hills, CA). We trained rats by placing them in a Lucite tube and inflating the tail blood pressure cuff several times a day for 4 days before the actual measurement of blood pressure. Blood pressure was measured six times in each rat, and the means of these values were used as the blood pressure for that rat.

In vitro microperfusion flux studies

Isolated segments of rat PCT were perfused as previously described (15). Briefly, rat PCT were dissected in Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing (in mM) 137 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.8 MgSO4, 0.33 Na2HPO4, 0.44 KH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 10 Tris·HCl, 0.25 CaCl2, 2 glutamine, and 2 L-lactate at 4°C. Dissected rat PCTs were transferred to a temperature-controlled bath. All tubules were studied from different rats.

PCTs were perfused with an ultrafiltrate-like solution containing (in mM) 115 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 4.0 Na2HPO4, 10 Na-acetate, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 5 KCl, 8.3 glucose, 5 alanine, 2 lactate, and 2 glutamine at ~10 nl/min. The bathing solution contained 6 g/dl bovine serum albumin. The osmolality of all solutions was adjusted to 300 mosmol/kgH2O. The bathing solution was heated to 38°C and exchanged at 0.5 ml/min to maintain a constant pH and osmolality.

Net volume absorption (JV, in nl·mm-1·min-1), an index of total sodium absorption in this segment, was measured as the difference between perfusion (VO) and collection (VL) rates (nl/min) normalized per millimeter of tubular length (L). The perfusion solution contained dialyzed [methoxy-3H]inulin at a concentration of 50–100 μCi/ml to determine the perfusion rate. The collection rate was measured with a 50-nl constant-volume pipette. The lengths were measured with an eyepiece micrometer. Tubules were incubated for ~15 min before initiation of the measurements for volume absorption. There were four measurements per tubule, and the mean was used to represent the volume absorption for that tubule.

Measurement of Na+/H+ exchange

The fluorescent dye 2′,7′-bis(2-carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein (BCECF) was used to measure intracellular pH (pHi) as described previously (4, 11, 25, 39, 44). pHi was measured with a Nikon inverted epifluorescent microscope attached to a PTI Ratiomaster at a rate of 30 measurements of pHi per second. A nigericin calibration curve was used to calculate pHi from the ratio of fluorescence (F500/F450) as previously described (11, 25, 44). There were at least four different rats studied in these experiments.

PCTs from rats that received prenatal vehicle and dexamethasone were perfused with a sodium-containing luminal solution (solution B) shown in Table 1. The perfusion solution did not contain organic solutes, because sodium-coupled glucose and amino acid transport depolarizes the basolateral membrane, which affects electrogenic bicarbonate transport across the basolateral membrane (4). The bath solution (solution A) contained 1 mM 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (SITS), which was present to inhibit the sodium bicarbonate cotransporter, a major regulator of pHi in PCTs, and 5 mM bicarbonate (pH 6.6) to compensate for the cell alkalinization caused by the addition of bath SITS (4, 11, 39). Although NHE1 is on the basolateral membrane, it plays a relatively small role in pH regulation of the proximal tubule compared with the basolateral sodium bicarbonate cotransporter (2, 4).

Table 1.

Solutions

| Luminal Na+ | Luminal 0-Na+ | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bath Solution A | Solution B | Solution C | |

| NaCl | 140 | 115 | |

| NaHCO3 | 5 | 25 | |

| NMDG-Cl | 115 | ||

| Choline HCO3 | 25 | ||

| KCl | 5 | ||

| K2HPO4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |

| MgCl2 | 1 | 1 | |

| MgSO4 | 1 | ||

| Na2HPO4 | 1 | ||

| Glucose | 5 | ||

| L-Alanine | 5 | ||

| Urea | 5 | ||

| CaCl2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Heptanoic acid | 2 | ||

| pH | 6.6 | 7.4 | 7.4 |

Concentrations of all constituents are in mM. All solutions were adjusted to an osmolality of 295 mosmol/kgH2O.

Cell pHi was measured by incubating tubules with 5 × 10−6 M BCECF-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 2 min to load tubules with the pH-sensitive dye BCECF. Tubules had a constant pHi for several minutes before the measurement of Na+/H+ exchanger activity. dpHi/dt was measured as rate of change in pHi immediately after sodium removal (solution C). Steady-state pHi values were reached within 1 min after a luminal fluid exchange. Under these conditions, the rate of change in pHi in response to a change in luminal sodium concentration is a measure of Na+/H+ exchanger activity (4, 11, 25, 39).

cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR

RNA was isolated from the rat renal cortex with the use of a GenEllute mammalian total RNA kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). RNA (2 μg) was used to make cDNA. RNA was first treated with DNase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and then random primers and dNTP were added along with StrataScript reverse transcriptase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to synthesize cDNA. cDNA was synthesized using an annealing temperature of 25°C for 10 min, extension at 42°C for 50 min, and termination at 70° for 15 min. Success of reverse transcription was validated using primers to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).

Real-time PCR was performed using an iCycler PCR thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) to quantify relative mRNA expression. Primers at 10 nM concentration were mixed with cDNA (1:50 dilution) and SYBR green master mix (Bio-Rad) per the manufacturer’s instructions. The PCR cycle was as followed: denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 61°C for 20 s, and extension at 72°C for 20 s, for 40 cycles. Water was used as a negative control instead of cDNA. The relative expression of NHE3 was determined by comparing abundance to the housekeeping gene 28S. Relative quantitation was assessed using the method described by Vandesompele et al. (49). Primers were as follows: GAPDH (forward), 5′-CAC CAT GGA GAA GGC-3′ and (reverse) 5′-TGC CAG TGA GCT TCC-3′; NHE3, (forward) 5′-ACT GCT TAA TGA CGC GGT GAC TGT-3′ and (reverse) 5′-AAA GAC GAA GCC AGG CTC GAT GAT-3′; and 28S (forward), 5′-TTG AAA ATC CGG GGG AGA G-3′ and (reverse) 5′-ACA TTG TTC CAA CAT GCC AG-3′.

Brush-border membrane vesicle isolation

Intraperitoneal Inactin (100 mg/kg) was administered before death of the rats. Kidneys were quickly removed and placed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The dissected cortex was placed in 10 ml of isolation buffer containing 300 mM mannitol, 16 mM HEPES, and 5 mM EDTA, titrated to pH 7.4 with Tris. The isolation buffer contained a protease inhibitor cocktail (1 μl/ml; Sigma) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (100 μg/ml). The cortex was homogenized using 15 strokes with a polytetrafluoroethylene-glass homogenizer at 4°C. Brush-border membrane vesicles (BBMV) were isolated by differential centrifugation and magnesium precipitation as previously described by our laboratory (44). The BBMV fraction was resuspended in isolation buffer. All protein fractions were assayed using the Bradford method with bovine serum albumin as the standard (20).

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting

BBMV (100 μg/lane) were denatured and then separated on a 7.5% polyacrylamide gel using SDS-PAGE as previously described (14, 44). Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane at 100 mV at 4°C for 1 h. The blots were blocked with Blotto (5% nonfat milk and 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS, pH 7.4) for 1 h before incubation with primary antibody to NHE3. The NHE3 antibody was polyclonal antibody generated in rabbits against a fusion protein of maltose-binding protein and amino acids 405–831 to rat NHE3 (6), which was added at a 1:750 dilution overnight at 4°C. The blots were washed in Blotto, followed by addition of the secondary antibody, a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody at 1:10,000 dilution. Enhanced chemiluminescence was used to detect bound antibody (Amersham Life Science). Equal loading of the samples was verified using an antibody to β-actin at 1:10,000 dilution (Sigma Biochemicals and Reagents, St. Louis, MO). Relative NHE3 and β-actin protein abundance were quantitated using densitometry.

Statistics

Student’s t-test for unpaired data was used to determine statistical significance. Data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Litter size, weight, and blood pressure

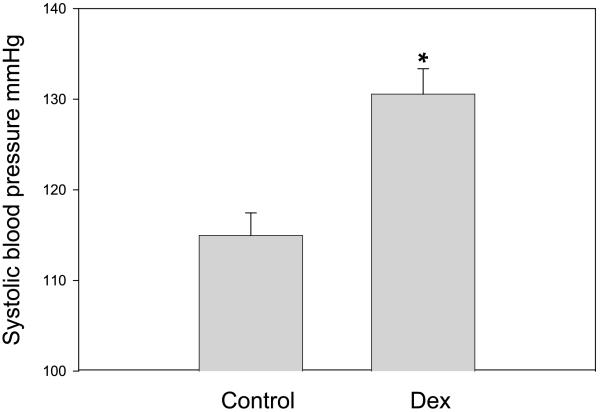

The litter size was 12.3 ± 0.8 in the control group and 10.1 ± 0.8 in the dexamethasone group (P = 0.06). Although the gestation for the control group was 21.6 ± 0.2 and 21.5 ± 0.2 days in the group that received prenatal dexamethasone, (n = 9 for both), the birth weight was significantly lower in the group whose mothers received prenatal dexamethasone compared with the rats that received vehicle (Table 2). The weights on day 1 were 6.3 ± 0.1 g in the control group and 4.3 ± 0.1 g in the dexamethasone group (P < 0.001). At 3 wk of age, the vehicle group weighed 56.5 ± 1.5 g and the dexamethasone group weighed 48.7 ± 1.1 g (P < 0.001). By 8 wk of age, there was no longer a difference in the weights (201 ± 8 g in the control group and 187 ± 8 g in the prenatal dexamethasone group). At 7–8 wk of age, the rats that were exposed to prenatal dexamethasone were hypertensive, as shown in Fig. 1. Both males and females were hypertensive, and the results were combined.

Table 2.

Effects of prenatal dexamethasone on litter size and weight

| Vehicle | Dexamethasone | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Litter size | 12.3±0.8 (9) | 10.1±0.8 (9) | 0.06 |

| Birth weight, g | 6.3±0.13 (40) | 4.3±0.09 (33) | <0.001 |

| 3-Wk weight, g | 56.5±1.5 (18) | 48.7±1.1 (18) | <0.001 |

| 8-Wk weight, g | 201±8 (22) | 187±6 (22) | 0.179 |

Values are means ± SE; values in parentheses represent the number of observations.

Fig. 1.

Effect of prenatal dexamethasone (Dex) on systolic blood pressure. Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats received either vehicle or Dex (0.2 mg/kg body wt) intraperitoneally daily between the 15th and 18th days of gestation. Blood pressure was measured in trained rats at 8 wk of age. There were 17 measurements in each group. *P < 0.001.

In vitro microperfusion studies

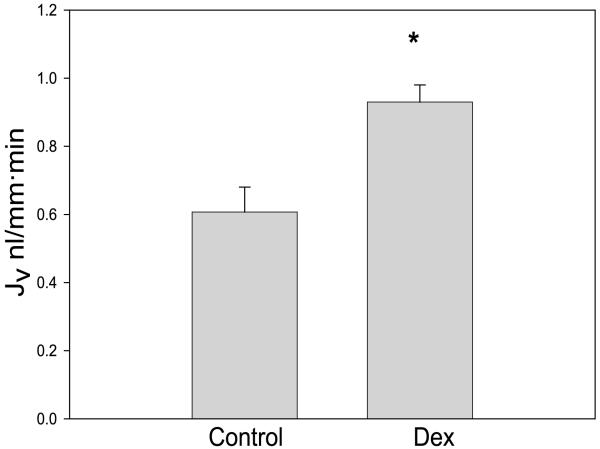

To determine whether prenatal dexamethasone affected PCT transport, we perfused tubules in vitro. The mean tubular length was 0.72 ± 0.18 mm in the vehicle group and 0.59 ± 0.08 mm in the group that received prenatal dexamethasone [P = not significant (NS)]. There were six tubules in each group. The rate of volume absorption in the two groups is shown in Fig. 2. Since the proximal tubule reabsorbs fluid in an isosmotic fashion, the rate of volume absorption reflects total sodium reabsorption in this segment. The rate of volume absorption from PCTs from rats that received prenatal dexamethasone was 50% higher compared with the group that received prenatal vehicle.

Fig. 2.

Effect of prenatal Dex on proximal tubular volume absorption (JV). Volume absorption, an index of sodium transport, was measured using the isolated perfused tubule technique in control rats and those that received prenatal Dex. There were 6 experiments in each group. The rate of volume absorption was significantly higher in rats that received prenatal Dex (*P < 0.05).

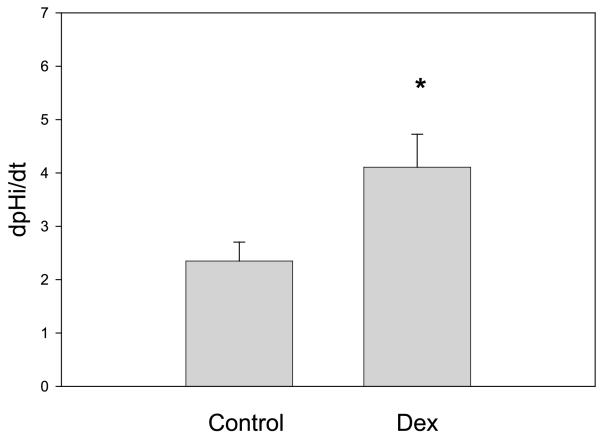

The Na+/H+ exchanger on the apical membrane of the proximal tubule is responsible for most of the sodium reabsorption in that segment (12, 39, 40). It is responsible for mediating most of proton secretion for bicarbonate reclamation as well as sodium reabsorption for transcellular NaCl transport, which is mediated by the parallel operation of the Na+/H+ and Cl−/base exchangers (7, 8, 45, 48); it also mediates the driving force for passive paracellular NaCl transport (42). We next examined whether there was a difference in Na+/H+ exchanger activity by measuring the rate of change in cell pHi with luminal sodium removal (4, 11, 25). There were eight tubules studied in the control group and nine in the group that received prenatal dexamethasone. As shown in Table 3, there was no change in basal cell pHi in control and prenatal dexamethasone. Removal of luminal sodium resulted in a cell acidification in both groups. The rate of change of cell pHi upon luminal sodium removal is an index of the rate of Na+/H+ exchanger activity in this segment, which was significantly greater in the group receiving prenatal dexamethasone (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Changes in cell pHi upon luminal Na+ removal

| Luminal Na+ | 0 Na+ | Luminal Na+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control pHi | 7.14±0.12 | 6.76±0.14* | 7.12±0.12 |

| Prenatal Dex pHi | 7.25±0.13 | 6.69±0.13* | 7.29±0.15 |

Dex, dexamethasone.

P < 0.05 vs. luminal Na +

Fig. 3.

Effect of prenatal Dex on Na+/H+ exchanger activity. Na+/H+ exchanger activity was measured in perfused tubules using the pH-sensitive dye BCECF. The rate was measured as the rate of change in intracellular pH with luminal sodium removal (dpHi/dt). There were 8 measurements in the control group and 9 in the prenatal dexamethasone group. The rate of change in pHi in tubules from rats that received prenatal Dex was higher than in tubules from control rats (*P < 0.05).

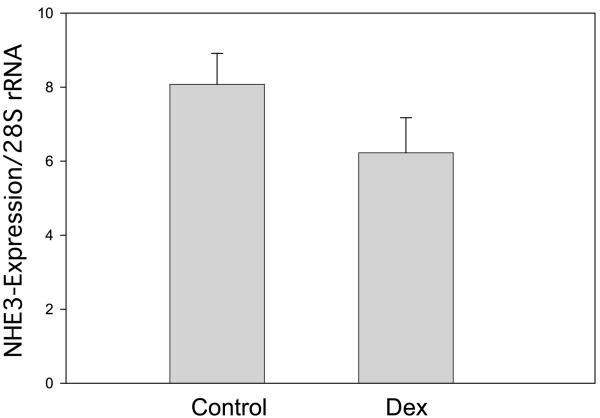

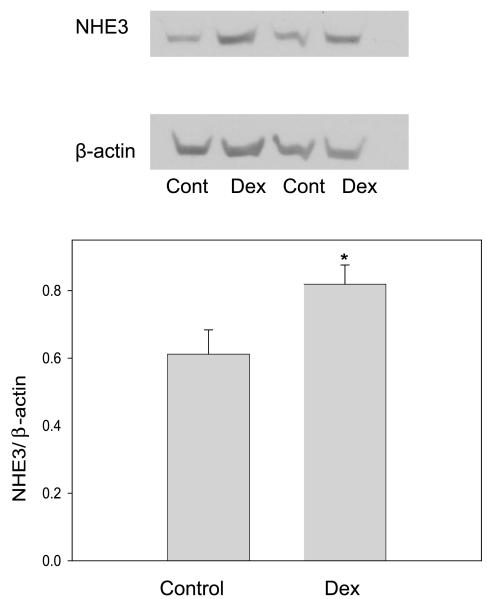

Renal NHE3 mRNA and protein abundance

Most of the Na+/H+ exchanger activity in the proximal tubule is mediated by the NHE3 isoform (55). There was no difference in the mRNA expression of NHE3 in antenatal vehicle-treated compared with the dexamethasone-treated animals (P = 0.152) (Fig. 4). However, NHE3/β-actin expression on BBMV was significantly higher in the prenatally dexamethasone-treated group, consistent with our studies examining Na+/H+ exchanger activity (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Effect of prenatal Dex on renal cortical NHE3 mRNA abundance. NHE3 mRNA was compared with 28S using real-time PCR. There were 19 experiments in each group. There was no effect of prenatal Dex on NHE3 mRNA abundance (P = 0.15).

Fig. 5.

Effect of prenatal Dex on brush-border membrane vesicle (BBMV) NHE3 protein abundance. There were 10 experiments in each group. NHE3 protein abundance was higher in BBMV from rats that were administered prenatal Dex (*P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The present study examined whether prenatal administration of dexamethasone administered to rats during the time in gestation previously shown to cause hypertension affected proximal tubular transport in the offspring. The present study demonstrated that prenatal programming by prenatal administration of dexamethasone could affect proximal tubule volume absorption, a reflection of sodium transport in this segment, and increase Na+/H+ exchanger activity. Although NHE3 mRNA abundance was not affected, there was an increase in NHE3 protein abundance.

The proximal tubule receives the glomerular ultrafiltrate and reabsorbs approximately two-thirds of the filtered sodium, including 60% of the filtered NaCl (34). Our study shows that prenatal administration of dexamethasone results in a 50% increase in the rate of proximal convoluted transport. Approximately one-half of the NaCl transport is active and transcellular and one-half of NaCl transport is reabsorbed passively across the paracellular pathway (5, 9, 13). Both transcellular and paracellular NaCl transport directly or indirectly are secondary to Na+/H+ exchange. Transcellular NaCl transport is mediated by the parallel operation of the Na+/H+ exchanger with a Cl−/base exchanger (3, 9, 45, 46). Passive NaCl transport is mediated by the preferential reabsorption of bicarbonate, mediated predominantly by the Na+/H+ exchanger (12, 39), over chloride ions in the early proximal tubule, resulting in a chloride gradient for passive paracellular NaCl transport. Most of proximal tubule Na+/H+ exchanger activity is mediated by NHE3 (55). This study demonstrates that Na+/H+ exchanger activity in proximal tubules as well as NHE3 protein abundance is increased by prenatal dexamethasone. Interestingly, there was no difference in NHE3 mRNA abundance despite the difference in protein abundance and Na+/H+ exchanger activity. Similar findings previously have been found in comparing spontaneously hypertensive rats to Wistar-Kyoto control rats (29). The mechanism for the increase in NHE3 protein abundance in the absence of an increase in mRNA is consistent with a posttranscriptional mechanism being involved. Indeed, we have recently demonstrated in opossum kidney cells that acute administration of dexamethasone can in NHE3 exocytosis (18).

In a previous study examining the effect of prenatal programming by maternal dietary protein deprivation on renal transporter mRNA and protein abundance, there was an increase in bumetanide-sensitive Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter and the thiazide-sensitive Na+-Cl− cotransporter protein abundance (31). However, there was no difference in NHE3 protein abundance (31). The different models of prenatal programming may affect transport in different nephron segments. One methodological difference is that the previous study examined whole kidney cortex (31), whereas our study examined BBMV.

It remains unclear whether enhanced expression of NHE3 can cause hypertension, because no transgenic overexpressing NHE3 mouse has yet been generated. However, NHE3 null mice have renal salt wasting and develop hypotension when placed on a low-salt diet (30). In addition, the increase in proximal tubule volume absorption and Na+/H+ exchanger activity could be secondary to an increase in single nephron GFR, because we have shown that GFR does not change and yet there is a reduction in nephron number in adult rats that are administered prenatal dexamethasone (35, 36), and not a primary event potentially causing hypertension. Previous studies showing an increase in proximal tubule transport or Na+/H+ exchanger have used uninephrectomy with or without protein loading, which likely resulted in a greater increase in single nephron GFR than in the current study (37, 38). In addition, hypertension has been noted by prenatal administration of dexamethasone in the absence of a reduction in nephron number (36).

Several possible theories have been proposed to explain the hypertension with prenatal programming and have recently been reviewed (1). Prenatal administration of dexamethasone and dietary protein deprivation are associated with a reduction of nephron number (24, 35, 36, 50, 53, 54). A reduction of nephron number has been postulated to be an important factor in mediating hypertension (21–23). However, in most studies there is only a 20–30% reduction in nephron number by the prenatal insult (35, 36, 50) with no change in GFR (35, 36). Thus, although a reduction in nephron number may be a contributing factor for mediating the hypertension in adults subjected to a prenatal insult, it is unlikely the only variable.

A dysregulation in the renin-angiotensin system also may contribute to the programming of hypertension in the offspring exposed to maternal dietary protein deprivation. Maternal dietary protein deprivation generates offspring with elevated plasma angiotensin converting enzyme activity (28) and an increase in renal type 1 angiotensin II receptors in prehypertensive offspring (51). Furthermore, the hypertension is responsive to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers (28, 32, 33, 47). The proximal tubule has all the components of the renin-angiotensin system, and the secreted luminal angiotensin II levels are 100-fold higher than in blood (19, 43). Both the systemic and intrarenal renin-angiotensin systems are known to play an important role in regulating proximal tubular transport (16, 26, 27, 41). Whether the augmented proximal tubule transport found in this study is due to the endogenous renin angiotensin system needs to be determined.

Acknowledgments

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-41612 (to M. Baum).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander BT. Fetal programming of hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1–R10. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00417.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alpern RJ. Mechanism of basolateral membrane H+/OH−/HCO−3 transport in the rat proximal convoluted tubule. A sodium-coupled electrogenic process. J Gen Physiol. 1985;86:613–636. doi: 10.1085/jgp.86.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alpern RJ. Apical membrane chloride/base exchange in the rat proximal convoluted tubule. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1026–1030. doi: 10.1172/JCI112914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alpern RJ, Chambers M. Cell pH in the rat proximal convoluted tubule. Regulation by luminal and peritubular pH and sodium concentration. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:502–510. doi: 10.1172/JCI112602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alpern RJ, Howlin KJ, Preisig PA. Active and passive components of chloride transport in the rat proximal convoluted tubule. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1360–1366. doi: 10.1172/JCI112111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amemiya M, Loffing J, Lotscher M, Kaissling B, Alpern RJ, Moe OW. Expression of NHE-3 in the apical membrane of rat renal proximal tubule and thick ascending limb. Kidney Int. 1995;48:1206–1215. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aronson PS. Role of ion exchangers in mediating NaCl transport in the proximal tubule. Kidney Int. 1996;49:1665–1670. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronson PS. Ion exchangers mediating NaCl transport in the proximal tubule. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1997;109:435–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aronson PS, Giebisch G. Mechanisms of chloride transport in the proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1997;273:F179–F192. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.2.F179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barker DJ, Winter PD, Osmond C, Margetts B, Simmonds SJ. Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1989;2:577–580. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baum M. Neonatal rabbit juxtamedullary proximal convoluted tubule acidification. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:499–506. doi: 10.1172/JCI114465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baum M. Developmental changes in rabbit juxtamedullary proximal convoluted tubule acidification. Pediatr Res. 1992;31:411–414. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199204000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baum M, Berry CA. Evidence for neutral transcellular NaCl transport and neutral basolateral chloride exit in the rabbit convoluted tubule. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:205–211. doi: 10.1172/JCI111403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum M, Dwarakanath V, Alpern RJ, Moe OW. Effects of thyroid hormone on the neonatal renal cortical Na+/H+ antiporter. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1254–1258. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baum M, Quigley R. Maturation of rat proximal tubule chloride permeability. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1659–R1664. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00257.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baum M, Quigley R, Quan A. Effect of luminal angiotensin II on rabbit proximal convoluted tubule bicarbonate absorption. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1997;273:F595–F600. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.4.F595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertram C, Trowern AR, Copin N, Jackson AA, Whorwood CB. The maternal diet during pregnancy programs altered expression of the glucocorticoid receptor and type 2 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: potential molecular mechanisms underlying the programming of hypertension in utero. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2841–2853. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bobulescu IA, Dwarakanath V, Zou L, Zhang J, Baum M, Moe OW. Glucocorticoids acutely increase cell surface Na+/H+ exchanger-3 (NHE3) by activation of NHE3 exocytosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F685–F691. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00447.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braam B, Mitchell KD, Fox J, Navar LG. Proximal tubular secretion of angiotensin II in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1993;264:F891–F898. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.5.F891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenner BM, Chertow GM. Congenital oligonephropathy: an inborn cause of adult hypertension and progressive renal injury? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1993;2:691–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chertow GM. Congenital oligonephropathy and the etiology of adult hypertension and progressive renal injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenner BM, Garcia DL, Anderson S. Glomeruli and blood pressure. Less of one, more the other? Am J Hypertens. 1988;1:335–347. doi: 10.1093/ajh/1.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celsi G, Kistner A, Aizman R, Eklof AC, Ceccatelli S, de Santiago A, Jacobson SH. Prenatal dexamethasone causes oligonephronia, sodium retention, and higher blood pressure in the offspring. Pediatr Res. 1998;44:317–322. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi JY, Shah M, Lee MG, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE, Muallem S, Baum M. Novel amiloride-sensitive sodium-dependent proton secretion in the mouse proximal convoluted tubule. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1141–1146. doi: 10.1172/JCI9260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cogan MG. Angiotensin II: a powerful controller of sodium transport in the early proximal tubule. Hypertension. 1990;15:451–458. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cogan MG, Xie MH, Liu FY, Wong PC, Timmermans PB. Effects of DuP 753 on proximal nephron and renal transport. Am J Hypertens. 1991;4:315S–320S. doi: 10.1093/ajh/4.4.315s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langley-Evans SC, Jackson AA. Captopril normalises systolic blood pressure in rats with hypertension induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol. 1995;110:223–228. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(94)00177-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaPointe MS, Sodhi C, Sahai A, Batlle D. Na+/H+ exchange activity and NHE-3 expression in renal tubules from the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Kidney Int. 2002;62:157–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ledoussal C, Lorenz JN, Nieman ML, Soleimani M, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE. Renal salt wasting in mice lacking NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger but not in mice lacking NHE2. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F718–F727. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.4.F718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manning J, Beutler K, Knepper MA, Vehaskari VM. Upregulation of renal BSC1 and TSC in prenatally programmed hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;283:F202–F206. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00358.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manning J, Vehaskari VM. Low birth weight-associated adult hypertension in the rat. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s004670000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manning J, Vehaskari VM. Postnatal modulation of prenatally programmed hypertension by dietary Na and ACE inhibition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R80–R84. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00309.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moe OW, Baum M, Berry CA, Rector FC. Renal transport of glucose, amino acids, sodium, chloride and water. In: Brenner BM, editor. The Kidney. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 2004. pp. 413–452. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ortiz LA, Quan A, Weinberg A, Baum M. Effect of prenatal dexamethasone on rat renal development. Kidney Int. 2001;59:1663–1669. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590051663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ortiz LA, Quan A, Zarzar F, Weinberg A, Baum M. Prenatal dexamethasone programs hypertension and renal injury in the rat. Hypertension. 2003;41:328–334. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000049763.51269.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pollock CA, Bostrom TE, Dyne M, Gyory AZ, Field MJ. Tubular sodium handling and tubuloglomerular feedback in compensatory renal hypertrophy. Pflügers Arch. 1992;420:159–166. doi: 10.1007/BF00374985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Preisig PA, Alpern RJ. Increased Na/H antiporter and Na/3HCO3 symporter activities in chronic hyperfiltration. A model of cell hypertrophy. J Gen Physiol. 1991;97:195–217. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preisig PA, Ives HE, Cragoe EJ, Jr, Alpern RJ, Rector FC., Jr Role of the Na+/H+ antiporter in rat proximal tubule bicarbonate absorption. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:970–978. doi: 10.1172/JCI113190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preisig PA, Rector FC., Jr Role of Na+-H+ antiport in rat proximal tubule NaC1 absorption. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1988;255:F461–F465. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.3.F461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quan A, Baum M. Endogenous production of angiotensin II modulates rat proximal tubule transport. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2878–2882. doi: 10.1172/JCI118745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rector FC., Jr Sodium, bicarbonate, and chloride absorption by the proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1983;244:F461–F471. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1983.244.5.F461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seikaly MG, Arant BS, Jr, Seney FD., Jr Endogenous angiotensin concentrations in specific intrarenal fluid compartments of the rat. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1352–1357. doi: 10.1172/JCI114846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shah M, Gupta N, Dwarakanath V, Moe OW, Baum M. Ontogeny of Na+/H+ antiporter activity in rat proximal convoluted tubules. Pediatr Res. 2000;48:206–210. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200008000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah M, Quigley R, Baum M. Maturation of rabbit proximal straight tubule chloride/base exchange. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1998;274:F883–F888. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.5.F883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah M, Quigley R, Baum M. Neonatal rabbit proximal tubule basolateral membrane Na+/Htubule NaC1 absorption+ antiporter and C1−/base exchange. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;276:R1792–R1797. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.6.R1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sherman RC, Langley-Evans SC. Antihypertensive treatment in early postnatal life modulates prenatal dietary influences upon blood pressure in the rat. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;98:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheu JN, Quigley R, Baum M. Heterogeneity of chloride/base exchange in rabbit superficial and juxtamedullary proximal convoluted tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1995;268:F847–F853. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.5.F847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. RESEARCH-0034.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vehaskari VM, Aviles DH, Manning J. Prenatal programming of adult hypertension in the rat. Kidney Int. 2001;59:238–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vehaskari VM, Stewart T, Lafont D, Soyez C, Seth D, Manning J. Kidney angiotensin and angiotensin receptor expression in prenatally programmed hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F262–F267. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00055.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vehaskari VM, Woods LL. Prenatal programming of hypertension: lessons from experimental models. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2545–2556. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005030300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wintour EM, Moritz KM, Johnson K, Ricardo S, Samuel CS, Dodic M. Reduced nephron number in adult sheep, hypertensive as a result of prenatal glucocorticoid treatment. J Physiol. 2003;549:929–935. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.042408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Woods LL, Weeks DA, Rasch R. Programming of adult blood pressure by maternal protein restriction: role of nephrogenesis. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1339–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu MS, Biemesderfer D, Giebisch G, Aronson PS. Role of NHE3 in mediating renal brush border Na+-H+ exchange. Adaptation to metabolic acidosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32749–32752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]