Abstract

In scientific teams as in life, conflicts arise. This paper aims to provide an introduction to tools and skills to help in managing conflicts in practice. Using a structured approach enables the concerns and interests of all involved to be identified and clarified. It also permits a better understand yourself and others and will help empower those in conflict to find acceptable and workable resolutions.

Introduction

This paper presents some fundamentals for conflict management in practice by focusing on how to assess and manage two-party and multi-party conflicts. While strong communication skills are very important, using a systematic approach is crucial to successful conflict management and provides a robust strategy for increasing the effectiveness of conflict conversations.

A research laboratory is a dynamic environment that is undergoing continual change. There is a diversity of backgrounds and opinions among the participants that can add both richness as well as challenges. In research, there are often high stakes, and significant pressures, particularly at times of diminishing resources. With increasing levels of internal and external regulation and ever more evident power dynamics, this mix can be a recipe for conflict.

So what can one do? How can we manage or resolve conflict? Our purpose in this paper is to provide an approach for productively managing conflict1. As with many other effective interventions, the first step is to recognize and diagnose the problem. There are different types of conflict, which may require different kinds of intervention and management skills

Table I describes a spectrum of responses to conflict. The control of process and decision-making by the parties changes with each type of response. In responding to conflict, many of us may initially want to take the watchful waiting approach and thereby avoiding conflict as we try to size up the situation. Yet in most cases some intervention is needed. At the initial (primary) level, the parties talk directly. At the next level, there may be a need for another party to help facilitate the discussion. This helper may be another colleague or peer, internal to your collaboration or sometimes external. Beyond these levels, the process and decision-making moves out of the parties’ hands to a higher authority. For this paper, we will focus on what you can do, as one of the involved parties or potentially, as a mediator for your colleagues, should they find themselves in conflict and ask for your help.

Table 1.

The Spectrum of Conflict Management Approaches

| Response to Conflict |

Process Type |

Process Control |

Decision-making Control |

Intervention Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ignore it | Inaction | None | None | Watchful waiting |

| Talk about it | Negotiation | Parties | Parties | Primary |

| Mediate it | Mediation | Mediator | Parties | Tertiary |

| Take it to a higher authority | Arbitration | Arbitrator | Arbitrator | Quaternary |

| Adjudication | Hearing Officer or Judge | Judge or Jury | Quaternary |

To begin this discussion it’s important to distinguish cognitive conflict from affective conflict. Cognitive conflict2 is a term used to describe disagreements that are issue-focused, not personal, and are characteristic of high performing groups. These disagreements are substantive in nature; they are about ideas and approaches. Cognitive conflicts are what we often seek in brainstorming where we encourage open problem-focused discussions to test ideas and assumptions, consider and reconcile differences, and undertake true collective decision-making. Affective conflict, in contrast, is what many of us prefer to avoid. These are conflicts with personal antagonism, often fueled by differences in values and beliefs. Affective conflict shifts the focus from ideas to the person and in doing so can be destructive to group performance and cohesion. In personalizing the issues, affective conflict undermines discussion by fostering defensiveness and can be a barrier that limits participation in the decision-making processes. Managing affective conflict can be challenging. To improve the chances of successfully managing conflict it is helpful to approach it cognitively -both in substance and in process.3

An Approach to Problem-Solving

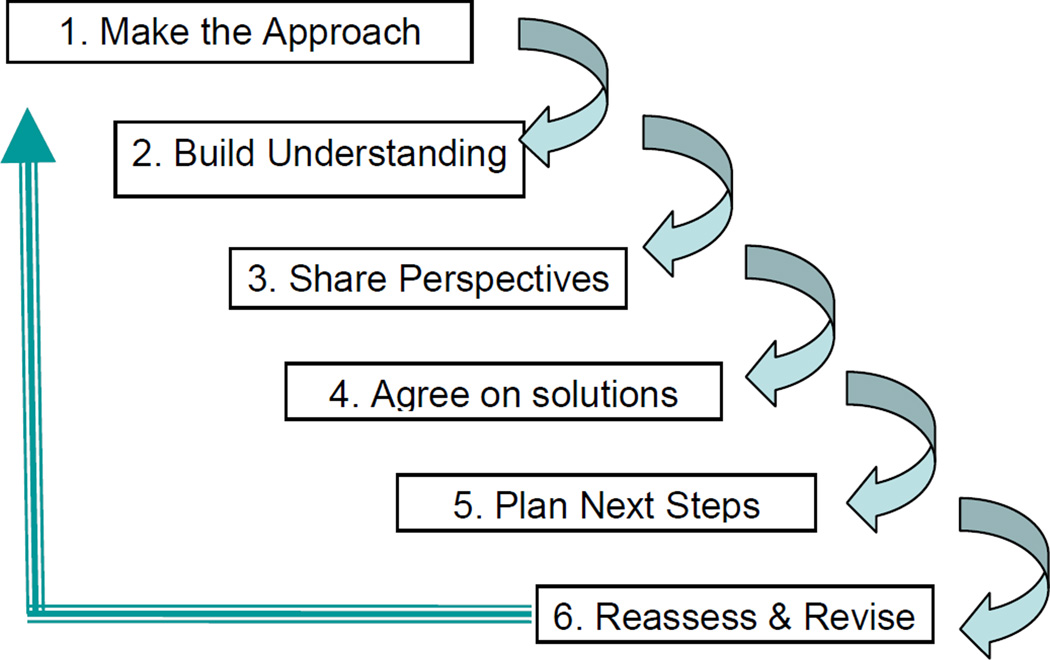

Figure 1 outlines one problem-solving approach you might use to do this.

Figure 1.

A Problem-Solving Approach to Conflict Management

Step 1: Make the Approach: Reflect – Invite - Set the Stage

Before starting, reflect

There is one chance to make a first impression, and the content and tone of the message (what is sent out) can impact the other party’s response (what is received and returned). In initiating this conflict-management strategy, not only are you raising the issue(s), you also are inviting the other(s) to participate and feel safe in discussing the matter(s) with you. Therefore, in setting the stage, it is critical to be clear about the intentions of the interaction, in particular highlighting the goal of reaching a positive resolution and engaging the other(s) as active participants in this process. Consider for example the potential collaboration between 2 faculty members (Drs Ally and Chase). Dr. Chase is a senior clinical researcher and he is hesitant about collaborating with Dr. Ally, in part due to Dr. Ally’s limited clinical research experience. Dr. Chase knows that trials involving human subjects can be complex and difficult. That said, Dr. Chase also recognizes great potential in the proposed joint project. If Dr. Chase decides to explore the possibility of working with Dr. Ally, he will need to resolve his human subjects research concerns. One option might be for Dr. Chase to initiate this discussion with Dr. Ally with a show of his enthusiasm for the project and for their potential collaborative effort. And with that, he could also inquire about the level of clinical research expertise that Dr. Ally believes will be needed and available to them in assuring the desired high quality research and human subject protections. By using this approach, Dr. Chase opens the door for a collaborative discussion on the topic in a way that enables both he and Dr. Ally to contribute.

Step 2. Share Perspectives: Similarities and Differences

Once you have initiated this “conversation,” it is time to share perspectives. You ask for the other person’s views, and it is often helpful if you then briefly paraphrase what you hear in response. This emphasizes that you are listening carefully to what is being said and can help to insure that all parties have the same understanding. Perspectives may differ, and therefore it is important that you acknowledge your contributions to the current situation (both positive and negative). And be clear about your perspectives – both similar and different from those expressed to you. Using the example above, Dr. Chase would invite Dr. Ally to a conversation and ask her to share her perspective first as he listens. While listening, he should not be planning what he will say in response, instead he should be listening in a way that enables Dr. Ally to feel that he is genuinely interested in her ideas and opinions. One way to demonstrate that he has heard her is by rephrasing what she has said and asking if he is understanding her correctly

Step 3: Build Understanding: Intent, Impact and the True Issues at Hand

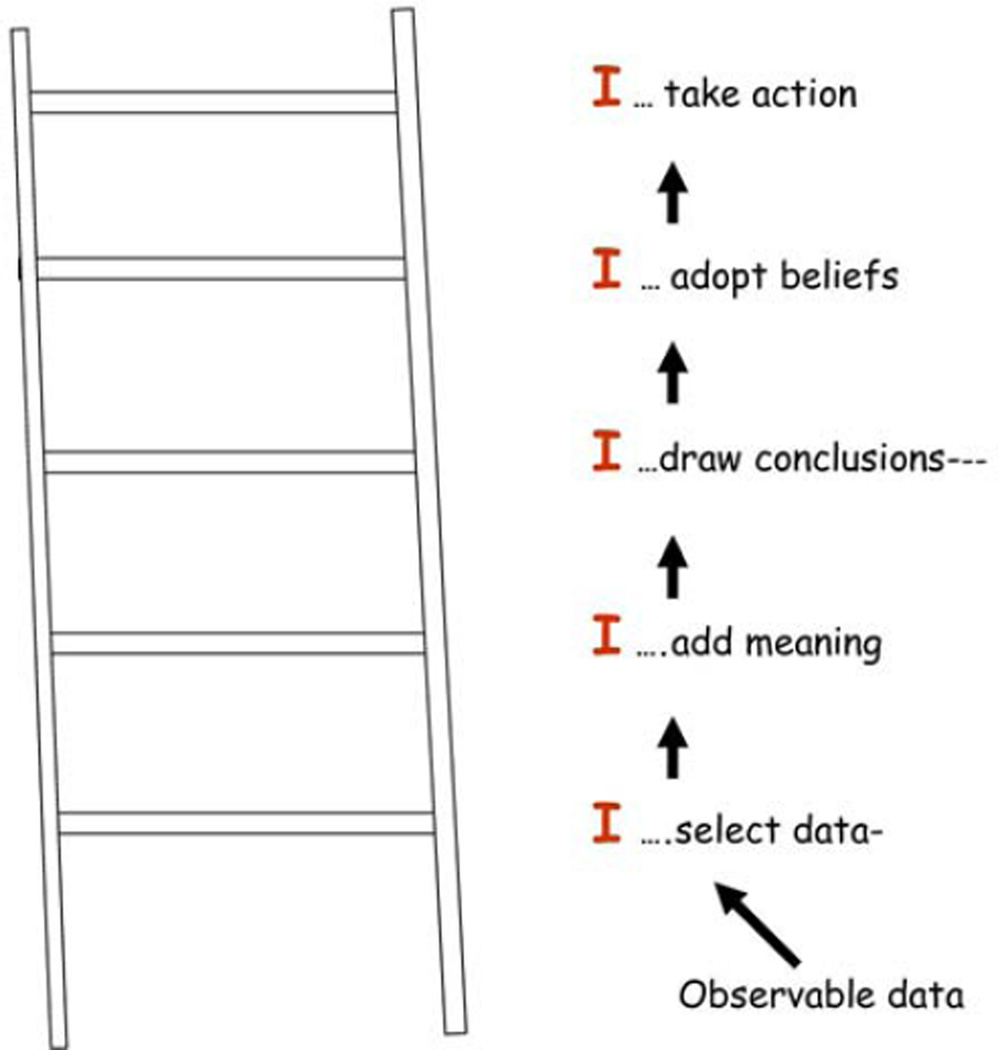

Working from a base of agreement is often helpful because it puts parties on the same page and emphasizes commonalities and alignments. From here the parties can work together to explore where and why their views differ. In doing this, it may be helpful to think about the factors that influence one’s beliefs and actions, as depicted in Figure 2 (based on the “ladder of Inference” of C. Argyris4 and D. Schon5).

Figure 2.

From Observation to Action: The Ladder of Inference* (from the bottom up)

* Based on the on the “ladder of Inference” of C. Argyris4 and D. Schon5

The filters, knowledge and approaches we each use in progressing up this “ladder of inference” may differ. Thus, the same observable data might result in differences at the various subsequent levels and ultimately in the actions that we each choose to take. While our actions are observed in the public sphere, what came before them (intent) and what comes after (impact) remain opaque within each person’s private spheres. You may know your own intent when acting but you may not know the intent in others’ actions. And while you may be aware of the impact of others’ actions on you, you may be unaware of how your actions impact others.

Therefore, separating intent from impact, and clarifying the true issues at hand are important next steps for building understanding. Identifying all the parties’ issues is key.6 And since issues may differ for each party, their initial descriptions need to be clear, using concise neutral language that avoids pronouns and judgments. These identified issues will form the conflict management agenda. By following this agenda, each issue is then separately discussed to be sure that assumptions are clear and that the interests and feelings of all parties, regarding each issue, are explored. With what is now hopefully a clearer picture for all of the issues and perspectives, what next? Here is where sensitivity and creativity intersect, as the involved parties agree on ground rules, summarize interests, and brainstorm to identify options. Recognizing the risks and benefits for each party, and the constraints and desires, how do you then succeed in moving towards agreement?

Step 4: Agree on Solutions: Doable and Durable

Successfully building understanding may help each party to put themselves into the other party’s shoes and to reach a negotiated agreement that is doable and durable for all. There is give and take in crafting solutions and successful resolution often depends on finding a solution that can maximize the interests of all parties. For example, if Drs Chase and Ally come to an agreement that Dr.Ally needs additional training in the conduct of clinical trials, they could probably uphold that and develop a strategy for her to obtain it as well as some mentoring. But if, instead, their agreement is that because of this gap they will work in separate labs and each focus on their own aspects of the project – while initially doable is that a durable solution? Not likely! In reaching an agreement, you need both doability and durability. The agreement needs to meet the interests of all the parties, because that’s where the durability comes from – by satisfying what people care most about.

Step 5: Plan Next Steps: Plans for Implementation

Often with managing conflict, we’re so happy to see some improvement in reaching a resolution that we just want to get it over with. To make it happen though, you have to think about its implementation. Once we are clear about what our (better) communication/collaboration looks like (our agreed upon solution), we also need to agree on the detailed steps to create it. For example, for increased communication, do we now need to have more lab meetings? Are we going to send more emails? Is there something about the research documentation that’s going to be different? What in fact is going to change in the current status quo? And who needs to do what in order to make that happen and by when? Part of the resolution is to set out the explicit plans and timelines, much the way that you would do in crafting the protocol for conducting research from your research grant proposal. Jointly outlining and reaching agreement on what needs to happen, who needs to do what (and by when), and any other specifics for implementation also helps to ensure that common intents are appropriately put into actions for attaining the desired impacts.

Step 6: Reassess and Revise: Communication…communication….communication

We mentioned at the start that laboratories, other types of research groups, and essentially all our relationships, are dynamic. So we return full circle, to reassess our collaborations, and communicate about what is working and what is not. Drawn into the excitement and challenges of our team’s science, we may tend not to focus on processes for reassessing and revising. As in many other areas, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Using this same problem solving approach, you can early and often address minor concerns before they become conflicts!

The more familiar and practiced you become with these conflict management steps, the more skillful and comfortable you will be putting them into practice. Many resources are available, such as the Collaboration & Team Science Field Guide7 and the team science toolkit8 from NIH, as well as others (see examples below). Importantly, we all face conflicts, so that seeking input and assistance from colleagues and collaborators can be a help to you and to them, as well.

We have presented a practical approach for managing conflicts through improved communication and structured problem solving that involves initiating, sharing, informing, agreeing, implementing and re-assessing. This approach can be used to align researchers’ differing perspectives, interests and expectations and to prevent and manage conflicts so that the diversity among research collaborators can foster new ideas and innovations for beneficial progress.

Acknowledgements

With her permission, this manuscript is a summary of the presentation by Catherine Morrison, JD, presented at the at the AFMR Career Development Workshop, Productive Translational Research: Tools for Connecting Research Cultures and Managing Conflict (2010 Experimental Biology Meeting, Anaheim, CA; April 24, 2010). The workshop was sponsored by the AFMR and supported by a grant from the NCRR/NIH #R13 RR023236. The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of the NCRR, AFMR, or any other institutions with which they are affiliated. My thanks to Catherine Morrison, JD, L. Michelle Bennett, PhD and Howard Gadlin, PhD for their reviews of the manuscript and helpful suggestions.

References

- 1.Garmston RJ. Group Wise: How to turn conflict into an effective learning process. [Accessed: 12/12/2011];JSD. 2005 26(3):65. Available At: http://www.learningforward.org/news/jsd/garmston263.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amason AC, Thompson K, Hochwarter W, Harrison A. Conflict: An Important Dimension in Successful Management Teams. Organizational Dynamics. 1995;24:22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mediation Services. Foundational concepts for understanding conflict. Winnipeg, MB, Canada.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Argyris C, Putnam R, McLain Smith D. Action Science: Concepts, Methods, and Skills for Research and Intervention. Jossey-Bass; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argyris Chris, Schön Donald. Theory in action: Increasing Professional Effectiveness. San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey Bass; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark W. People Whose Ideas Influence Organisational Work - Chris Argyris. [Accessed 11/12/2011]; Available at: http://www.onepine.info/pargy.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett LM, Gadlin H, Levine-Finley S. Collaboration & Team Science: A Field Guide. [Accessed 11/12/2011];[National Institutes of Health website] 2011 Available at: https://ccrod.cancer.gov/confluence/download/attachments/47284665/TeamScience_FieldGuide.pdf?version=1&modificationDate=1271730182423.

- 8.National Cancer Institute. Team Science Toolkit. [Accessed 11/12/2011];[National Institutes of Health] 2011 Available at: https://www.teamsciencetoolkit.cancer.gov/public/home.aspx?js=1.

Additional Suggested Readings

- 1.Eisenhardt K, Kahwajy L, Bourgeois LJ. How Management Teams Can Have a Good Fight. Harvard Business Review. 1997 Jul-Aug;:77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson RJ. Errors in Social Judgment: Implications for negotiation and Conflict Resolution. Harvard Business School Publishing; 1997. Feb 6, pp. 1–7. Case Note 897103. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sussman L. How to Frame a Message: The Art of Persuasion and Negotiation. Business Horizons. 1999 Jan 15;:2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tannen D. The Power of Talk: Who Gets Heard and Why. Harvard Business Review. 1995 Sep-Oct;:138–148. [Google Scholar]