Abstract

Purpose

We investigated racial disparities in healthy behaviors and cancer screening in a large sample from the US population.

Methods

This analysis used the data from 2005 National Health Interview Survey and included women at age ≥40 years who completed the cancer questionnaires (2,427,075 breast cancer survivors and 57,978,043 women without cancer). Self-reported information on cancer history, healthy behaviors (body mass index, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, fruit/vegetable consumption, sunscreen use). We compared distributions of each factor among Caucasian, African American and Hispanic women with and without breast cancer history.

Results

Caucasian breast cancer survivors as compared to their cancer-free counterparts were less likely to be current smokers (8.3 vs.16.9%, p<0.001) and to have regular mammograms (51.5 vs.36.9%, p<0.05). Differences in associations between cancer survivors and respondents without cancer among African American and Hispanic women did not reach statistical significance.

Conclusions

Certain breast cancer survivor groups can benefit from tailored preventive services that would address concerns related to selected healthy behaviors and screening practices. However, most of the differences are suggestive and do not differ by race.

Keywords: healthy behaviors, cancer screening, breast cancer survivors, population-based survey, multistage sampling

Introduction

According to the American Cancer Society, over 230,000 new breast cancer cases are expected in 2013 [1]. Recent advances in breast cancer detection and treatment have resulted in improved survival, which increased the prevalence of cancer survivors [2]. Based on the statistics from Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results, more than 2.8 million women in the United States were breast cancer survivors in 2010, the largest survivor group among women with cancer [3]. Breast cancer survivors are at a greater risk of developing a second primary cancer of breast, ovaries, colon, and rectum, as well as physical and psychological complications of treatment, and other comorbidities including obesity, cardiovascular disease and hypertension, osteoporosis, and diabetes [4-9]. Healthy lifestyle choices help to manage long-term health consequences of cancer by controlling and preventing the incidence of many of these conditions [10-12]. Recommended healthy behaviors, such as increased physical activity, proper nutrition, refraining from tobacco and alcohol use, maintaining healthy weight, and adherence to recommended cancer screening guidelines, have shown to reduce incidence of adverse health outcomes and to improve overall quality of life among cancer survivors [13-22]. However, despite potential benefits of healthy lifestyle choices, cancer survivors often do not meet all behavioral and medical guidelines recommendations [14, 23, 24].

The data on differences in healthy behaviors and screening practices between breast cancer survivors and women without a cancer history from population-based studies is limited. A few studies in the US breast cancer survivors compared healthy behaviors by breast cancer survivorship status, but did not examine these differences by race/ethnicity. This analysis aimed to compare healthy behaviors and cancer screening practices among breast cancer survivors and respondents without cancer separately in Caucasian, African American, and Hispanic women. Understanding these differences may help to develop tailored and culturally adapted clinical preventive services to ensure long-term health benefits among breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Survey population and design

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a cross-sectional household survey administered to the non-institutionalized US population by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to monitor the health of the US population and to collect data for epidemiologic studies and policy analyses to address ongoing public health issues [25].

The survey utilizes a multistage probability sample design that has been previously described in detail [25]. The NHIS questionnaire collects information on basic health and demographics (core questionnaire), healthcare access and utilization, health insurance, and income and assets, and on current health topics. The data are collected separately from adults and children in each family. The 2005 NHIS survey includes a supplement that covers a variety of cancer-related topics such as diet, physical activity, tobacco and alcohol use, and cancer screening.

Study population

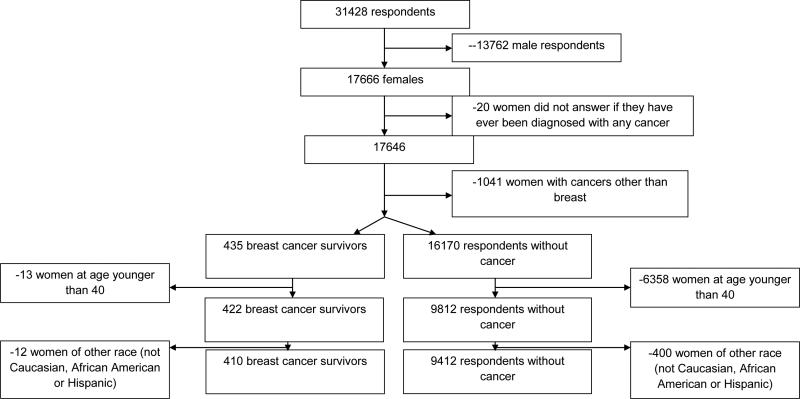

This analysis used 2005 NHIS data and was limited to adult female participants (age 18 and older) who completed the cancer questionnaires (Figure 1). From 17,666 women who completed the survey, we excluded 20 participants (0.1%) with missing data on cancer history and 1,041 women (5.9%) diagnosed with cancers other than breast (including non-melanoma skin). Women who reported a history of breast cancer were referred to as breast cancer survivors (n=435). Participants reporting that they never had a cancer diagnosis were referred to as respondents without cancer (n=16,170). We further restricted this analysis to women at age 40 and older (97.0% of survivors and 60.7% of cancer-free respondents) due to a very small number of younger breast cancer survivors (n=13). Furthermore, 12 cancer survivors and 400 respondents without cancer that reported race other than Caucasian, African American or Hispanic were also excluded. Final sample for this analysis included 410 breast cancer survivors and 9,412 respondents without cancer. Among these women, 6,973 were Caucasian (71.0%), 1,496 were African American (15.2%) and 1,353 were Hispanic (13.8%).

Fig. 1.

Women in the analysis: inclusion/exclusion flowchart

Healthy behaviors and cancer screening

We selected the following indicators of healthy behaviors to compare cancer survivors and respondents without cancer: body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol use, physical activity, fruit/vegetable consumption, sunscreen use, and screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer. Self-reported height and weight were used to calculate BMI (kg/m2). BMI categories were defined as ≤24.9 (underweight or normal weight), 25-29.9 (overweight), 30-34.9 (obese), and >35 kg/m2 (morbidly obese). Smoking status of the participants was categorized as never, former smoker, current smoker, and unknown. Dietary Guidelines for Americans for 2005 were used to define the woman's alcohol use status as never use, former use, current use below the recommended limit of >7 drinks per week, and current use above the recommended limit [26]. Use of sunscreen was categorized as always, sometimes, never, and unknown (including participants who reported not going into the sun). Participants answered questions about weekly frequency and average duration of moderate and vigorous physical activities. From these, we calculated total minutes per week of vigorous or moderate activity and categorized physical activity as inactive (total minutes=0), insufficiently active (total minutes more than 0 and less than 150), and sufficiently active (total minutes equal to 150 or more) [27].

To estimate the intake of 18 food categories, the 5-Factor Screening was administered as part of the 2005 NHIS questionnaire [28]. For this study, adjusted cup equivalents of vegetables (excluding French fries) per day and adjusted cup equivalents of fruit were used to determine if participants met the US Department of Agriculture 2005 guidelines for adequate fruit/vegetable consumption (4.5 cups daily) [26].

Participants were asked about their participation in cancer screening (colonoscopy for colorectal cancer, Pap smear for cervical cancer, and mammogram for breast cancer) and to specify when they had their last screening. Based on the provided information, compliance with the screening for breast and cervical cancer was categorized as screening within the last 2 years (compliant or regular), screening within the last 2-5 years, and screening more than 5 years ago. For colorectal cancer screening, the categories were defined as screening within the last 5 years (compliant or regular), screening within the last 5-10 years, and screening more than 10 years ago.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, USA) and SAS callable SUDAAN10 (Research Triangle Institute, NC, USA). We accounted for the complex survey structure (multistage probability sample design) throughout the analyses by specifying NHIS household- and person-level weights in analytical statements [29]. Because of this complex sampling design, all the results are presented in the form of weighted estimates, which in this case, are more appropriate than the sample statistics. After weighting, our analyses included 2,427,075 breast cancer survivors and 57,978,043 respondents without cancer, which correspond to 410 and 9,412 participants in the sample, respectively.

We used χ2 test to compare distributions of the following socio-demographic characteristics among cancer survivors and respondents without cancer within each racial group separately: age (40-49, 50-59, and ≥60 years), marital status (married or partner, other), education (less than high school level, high school graduate or equivalent, some college or associate degree, bachelor's degree or above), employment (employed, unemployed) and insurance (uninsured, private insurance, Medicare, and other plans). χ2 test was also used to compare distributions of the following healthy behaviors and screening practices among cancer survivors and respondents without cancer and was carried out separately for each racial group: BMI (≤24.9, 25-29.9, 30-34.9, ≥35 kg/m2), smoking status (never smoked, former smoker, current smoker), alcohol use (never used, former user, current user below recommended limit [26], current user above recommended limit), physical activity (none, insufficiently active, sufficiently active), sunscreen use (always/most of the time, sometimes or rarely, never), adequate fruit/vegetable intake (no or <4.5 cups/day, yes or ≥4.5 cups/day), colorectal cancer screening (within past 5, 6-10, and >10 years), breast cancer screening (mammogram within past 2, 3-5, and >5 years), and cervical cancer screening (Pap-smear within past 2, 3-5, and >5 years).

We used multivariate logistic regression to analyze the association of healthy behaviors with cancer status by race while controlling for age, marital status, employment, education, and insurance. Cancer survivors were compared to respondents without cancer (reference group) separately within each racial/ethnic group. For each of the healthy behavior risk factors, the category representing the healthy behavior was used as the reference. To retain observations with missing data on covariates in the logistic regression analysis, we created an “Unknown” category for each of these variables with missing data. Differences in associations of healthy behaviors with survivorship status across racial groups were tested by including an interaction term in the full model. Statistical significance was assessed at 0.05 level in all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of breast cancer survivors (weighted N=2,427,075) and respondents without cancer (weighted N=57,978,043) by their race and cancer survivorship status are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Estimated (weighted) demographic characteristics of cancer survivors and respondents without cancer, National Health Interview Survey 2005 (estimates percentage and 95% Confidence Intervals)

| Healthy Behavior/Screening practice | Caucasian Women | African American Women | Hispanic Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer survivors (weighted N 2,148,453) | Respondents with no cancer (weighted N=45,120,664) | Breast cancer survivors (weighted N=150,762) | Respondents with no cancer (weighted N=7,104,744) | Breast cancer survivors (weighted N=127,860) | Respondents with no cancer (weighted N=5,752,635) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 40-49 | 10.1 (6.7-14.9)a | 33.1 (31.7-34.5) | 11.8 (4.6-27.2)a | 39.8 (36.9-42.8) | 28.5 (12.3-52.0) | 43.6 (40.0-47.1) |

| 50-59 | 19.5 (15.5-24.3) | 27.9 (26.6-29.3) | 23.0 (11.0-42.0) | 29.0 (26.5-31.7) | 17.2 (6.3-38.9) | 29.6 (26.6-32.8) |

| ≥60 | 70.4 (64.7-75.6) | 39.0 (37.6-40.4) | 65.2 (47.1-79.8) | 31.2 (28.5-34.1) | 54.3 (28.7-77.9) | 26.8 (23.8-30.0) |

| Education | ||||||

| < High School | 7.2 (5.1-9.9) | 7.2 (6.5-7.9) | 15.9 (8.1-28.9) | 18.0 (15.9-20.4) | 23.5 (10.0-45.8) | 27.7 (24.1-31.7) |

| High School Graduate or Equivalent | 24.3 (20.0-29.3) | 25.8 (24.6-27.1) | 34.2 (19.5-52.7) | 27.3 (24.5-30.1) | 18.7 (7.1-40.6) | 23.7 (20.7-27.0) |

| >Some College or Associate Degree | 27.8 (23.0-33.2) | 30.4 (29.1-31.6) | 33.2 (17.6-53.8) | 33.5 (30.7-36.4) | 18.7 (7.7-38.9) | 30.4 (27.1-33.8) |

| >Bachelor's Degree | 40.8 (35.4-46.3) | 36.7 (35.1-38.2) | 16.7 (5.4-41.0) | 21.3 (18.7-24.1) | 39.2 (15.2-69.9) | 18.2 (15.5-21.3) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married or Partner | 28.7 (52.3-64.3)b | 65.8 (64.5-67.1) | 2.0 (0.3-12.9)a | 40.3 (37.3-43.5) | 55.7 (30.4-78.3) | 62.5 (59.5-65.3) |

| Other | 41.3 (35.7-47.2) | 34.2 (33.0-35.5) | 98.0 (87.1-99.7) | 59.7 (56.6-62.7) | 44.3 (21.7-69.6) | 37.5 (34.7-40.5) |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Uninsured | 2.1 (0.9-4.6)a | 6.9 (6.2-7.7) | 6.2 (2.0-17.3)b | 16.1 (13.7-18.8) | 14.5 (5.1-34.9) | 28.0 (24.8-31.3) |

| Private insurancec | 37.9 (32.1-44.1) | 58.6 (57.1-60.1) | 30.0 (15.9-49.3) | 50.2 (46.9-53.5) | 21.7 (8.5-45.1) | 42.7 (39.1-46.3) |

| Medicare | 48.8 (43.2-54.5) | 25.2 (24.0-26.4) | 31.4 (17.2-50.2) | 17.9 (15.5-20.6) | 37.3 (14.5-67.6) | 13.0 (11.1-15.1) |

| Other plansd | 11.2 (8.0-15.6) | 9.4 (8.5-10.2) | 32.4 (18.6-50.2) | 15.8 (13.8-18.1) | 26.5 (9.6-55.0) | 16.4 (14.0-19.2) |

| Employed | ||||||

| Employed | 36.0 (30.4-42.0)a | 58.7 (57.2 -60.1) | 28.6 (14.8-48.0)a | 60.2 (56.8-63.4) | 24.1 (11.1-44.6)b | 56.4 (52.9-59.9) |

| Unemployed | 64.0 (58.0-69.6) | 41.3 (39.9-42.8) | 71.4 (52.0-85.2) | 39.8 (36.6-43.2) | 75.9 (55.4-88.9) | 43.6 (40.1-47.1) |

Note: estimated percentages are calculated from non-missing data

difference between cancer survivors and respondents without cancer within the race is significant at 0.01 level

difference between cancer survivors and respondents without cancer within the race is significant at 0.05 level

also includes military health insurance

also includes Medicaid and Medi-gap

Among Caucasian women, cancer survivors were more likely to have regular breast cancer screening, and were less likely to be current smokers (Table 2). We did not find any statistically significant differences in healthy behaviors between African American breast cancer survivors and African American women without cancer. However, African American breast cancer survivors appeared to be more obese, less likely to be physically active and to have regular mammograms or Pap smear, though these differences were not statistically significant. Hispanic breast cancer survivors were more likely to have healthier weight, to consume alcohol above the recommended limit, and to have regular mammograms and screening for colorectal cancer and were less likely to use sunscreen regularly, but these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Estimated (weighted) prevalence of healthy behaviors among breast cancer survivors and respondents without cancer, by Race, National Health Interview Survey 2005 (estimates percentage and 95% Confidence Intervals)

| Healthy Behavior/Screening practice | Caucasian Women | African American Women | Hispanic Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer survivors (weighted N 2,148,453) | Respondents with no cancer (weighted N=45,120,664) | Breast cancer survivors (weighted N=150,762) | Respondents with no cancer (weighted N=7,104,744) | Breast cancer survivors (weighted N=127,860) | Respondents with no cancer (weighted N=5,752,635) | |

| BMI | ||||||

| 0-24.9 | 43.9 (37.7-50.2) | 44.6 (43.1-46.1) | 22.7 (11.0-41.2) | 25.1 (22.5-28.0) | 48.8 (24.5-73.8) | 29.8 (26.5-33.3) |

| 25-29.9 | 35.7 (30.2-41.5) | 30.4 (29.1-31.7) | 15.2 (6.7-30.7) | 35.1 (32.1-38.3) | 31.8 (13.5-58.1) | 33.6 (30.5-36.9) |

| 30-34.9 | 13.0 (9.3-18.0) | 15.3 (14.3-16.4) | 21.6 (9.2-42.9) | 21.1 (18.7-23.8) | 16.2 (6.5-35.1) | 21.5 (18.4-25.1) |

| >35 | 7.4 (4.8-11.2) | 9.7 (8.9-10.6) | 40.5 (24.2-59.2) | 18.7 (16.4-21.2) | 3.2 (0.4-20.1) | 15.1 (12.8-17.7) |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoked | 60.1 (54.2-65.6)a | 58.0 (56.7-59.2) | 57.4 (38.7-74.3) | 63.8 (60.6-66.9) | 77.2 (54.7-90.5) | 77.3 (74.2-80.1) |

| Former smoker | 31.6 (26.4-37.3) | 25.2 (24.1-26.3) | 27.8 (14.1-47.6) | 17.4 (15.2-19.8) | 15.1 (5.2-36.4) | 11.2 (9.4-13.4) |

| Current smoker | 8.3 (5.8-11.8) | 16.9 (15.9-17.9) | 14.8 (6.3-30.9) | 18.8 (16.7-21.1) | 7.7 (2.2-23.9) | 11.5 (9.5-13.9) |

| Alcohol | ||||||

| Never used | 25.6 (20.9-30.9) | 25.0 (23.7-26.4) | 41.0 (25.4-58.7) | 43.4 (40.0-46.9) | 48.9 (24.0-74.4) | 47.3 (43.6-50.9) |

| Former user | 21.9 (17.9-26.5) | 17.0 (15.9-18.1) | 28.7 (16.0-46.0) | 21.8 (19.3-24.6) | 7.0 (1.7-24.3) | 14.2 (11.9-16.9) |

| Current user <7 drinks/week | 48.2 (43.0-53.5) | 53.0 (51.6-54.5) | 29.5 (16.4-47.2) | 32.5 (29.6-35.6) | 39.6 (15.5-70.0) | 37.8 (34.1-41.4) |

| Current user >7 drinks/week | 4.4 (2.4-7.8) | 5.0 (4.4-5.6) | 0.8 (0.1-5.7) | 2.3 (1.5-3.5) | 4.5 (1.0-18.5) | 0.8 (0.4-1.7) |

| Physical Activity | ||||||

| None | 46.1 (40.0-52.2) | 40.2 (38.6-41.9) | 66.6 (46.9-81.8) | 60.3 (57.1-63.5) | 69.0 (43.3-88.1) | 61.8 (58.1-65.3) |

| Moderate | 20.8 (16.5-25.9) | 21.5 (20.3-22.8) | 23.8 (11.2-43.6) | 18.6 (16.3-21.1) | 5.1 (1.2-18.9) | 16.9 (14.7-19.4) |

| Active | 33.1 (27.9-38.8) | 28.3 (36.8-39.8) | 9.6 (3.4-24.4) | 21.1 (18.7-23.8) | 25.8 (5.6-56.3) | 21.4 (18.7-24.2) |

| Sunscreen use | ||||||

| Always/most of the time | 50.5 (44.0-57.0) | 45.7 (44.1-47.2) | 9.9 (2.5-31.8) | 12.9 (10.7-15.5) | 18.4 (6.5-42.5) | 31.0 (27.9-34.2) |

| Sometimes/ rarely | 25.7 (20.3-31.9) | 28.9 (27.5-30.3) | 17.3 (6.5-38.8) | 18.0 (15.1-21.4) | 15.6 (6.3-33.9) | 19.8 (16.8-23.3) |

| Never | 23.8 (18.6-30.1) | 25.4 (24.2-26.8) | 72.8 (50.6-87.4) | 69.0 (65.1-72.7) | 66.0 (40.5-84.7) | 49.2 (45.6-52.8) |

| Adequate fruit/vegetable intakec | ||||||

| Yes (≥4.5 cups/day) | 5.0 (3.0-8.1) | 5.9 (5.3-6.6) | 5.9 (0.8-31.8) | 4.8 (3.4-6.6) | 5.2 (1.1-20.5) | 5.2 (3.9-6.9) |

| No (<4.5 cups/day) | 95.0 (91.9-97.0) | 94.1 (93.4-94.7) | 94.1 (68.2-99.2) | 95.3 (93.5-96.6) | 94.8 (79.5-98.9) | 94.8 (93.1-96.1) |

| Colorectal cancer screening | ||||||

| within past 5 years | 61.4 (48.5-72.8) | 61.3 (58.0-64.1) | 76.8 (47.8-92.3) | 73.6 (64.7-80.9) | 100 | 73.0 (64.4-80.1) |

| within past 6-10 | 27.8 (18.6-39.5) | 24.5 (21.9-27.2) | 20.3 (6.1-49.9) | 17.5 (11.2-26.2) | 0 | 11.5 (6.5-19.4) |

| within >10 years | 10.8 (5.3-20.8) | 14.4 (12.4-16.7) | 3.0 (0.4-19.4) | 9.0 (4.7-16.4) | 0 | 15.5 (10.2-22.9) |

| Breast cancer screening (mammogram) | ||||||

| within past 2 years | 51.5 (38.6-64.1)b | 36.9 (34.3-39.5) | 37.2 (16.9-63.4) | 49.0 (43.1-54.9) | 62.9 (25.5-89.3) | 45.3 (38.3-52.6) |

| within past 3-5 | 17.7 (10.1-29.1) | 36.1 (33.4-38.9) | 16.3 (4.0-48.1) | 32.4 (27.2-38.2) | 23.1 (3.5-71.3) | 34.3 (28.4-40.6) |

| within >5 years | 30.9 (20.4-43.8) | 27.0 (24.6-29.5) | 46.5 (18.9-76.3) | 18.6 (14.7-23.4) | 14.0 (3.1-45.3) | 20.4 (16.0-25.8) |

| Cervical cancer screening (pap-smear) | ||||||

| within past 2 years | 27.6 (19.9-36.9)b | 27.1 (25.0-29.2) | 17.3 (2.5-62.3) | 37.4 (32.1-42.9) | 30.5 (6.9-72.4) | 27.5 (32.7-42.6) |

| within past 3-5 | 18.1 (12.1-26.3) | 31.2 (29.2-33.3) | 28.2 (9.3-60.1) | 30.2 (25.9-34.9) | 61.2 (18.6-91.6) | 33.9 (28.3-39.9) |

| within >5 years | 54.3 (44.8-63.5) | 41.7 (39.5-44.0) | 54.6 (24.7-81.6) | 32.5 (27.4-37.9) | 8.3 (1.3-37.8) | 28.6 (23.9-33.9) |

Note: estimated percentages are calculated from non-missing data

difference between cancer survivors and respondents without cancer within the race is significant at 0.0001 level

difference between cancer survivors and respondents without cancer within the race is significant at 0.05 level

According to 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

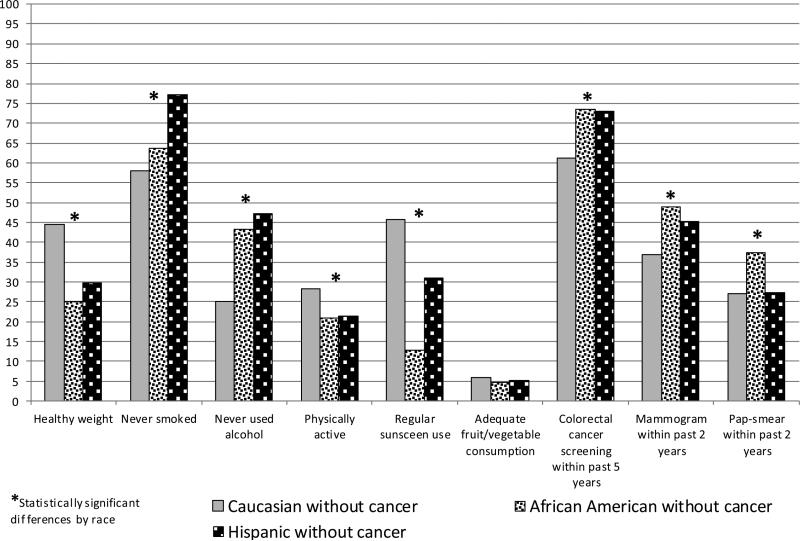

When comparing only cancer survivors across their race/ethnicity, significant differences in healthy behaviors were found in alcohol use, physical activity, and sunscreen use (Figure 2). African American and Hispanic breast cancer survivors were less likely to adhere to healthy behaviors as compared to their Caucasian counterparts. When comparison by race/ethnicity was limited to respondents without cancer, statistically significant differences were found for all healthy behaviors except adequate fruit/vegetable consumption (Figure 3).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of Healthy Behaviors in Breast Cancer Survivors, by Race

Fig. 3.

Distribution of Healthy Behaviors in Women without Cancer, by Race

In multivariate logistic regression analysis, associations of healthy behaviors with breast cancer survivorship status were similar in Caucasian, African American and Hispanic women for all behaviors except healthy weight (p for interaction 0.01) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate odds ratios for health behaviors and screening practices comparing breast cancer survivors to respondents without cancer, by Race, National Health Interview Survey 2005 (Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence intervals)a

| Healthy Behavior/Screening practice | Caucasian | African American | Hispanic | p-values for interaction of race with healthy behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | ||||

| 0-24.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.01 |

| 25-29.9 | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | 0.4 (0.1-1.4) | 0.6 (0.2-2.2) | |

| 30-34.9 | 1.0 (0.7-1.6) | 1.3 (0.4-4.3) | 0.5 (0.1-1.6) | |

| >35 | 1.1 (0.7-1.8) | 2.0 (1.0-8.4) | 0.1 (0.0-1.3) | |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoked | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.89 |

| Former smoker | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) | 1.4 (0.6-3.5) | 1.3 (0.3-4.6) | |

| Current smoker | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) | 1.0 (0.4-2.7) | 0.8 (0.2-3.4) | |

| Alcohol | ||||

| Never used | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.12 |

| Former user | 1.3 (0.9-1.9) | 1.2 (0.5-2.7) | 0.5 (0.1-2.2) | |

| Current user <7 drinks/week | 1.3 (1.0-1.7) | 1.4 (0.6-3.3) | 1.2 (0.4-4.1) | |

| Current user >7 drinks/week | 1.2 (0.6-2.4) | 0.6 (0.1-5.9) | 8.3 (1.3-51.7) | |

| Physical Activity | ||||

| None | 1.0 (0.8-1.4) | 1.5 (0.4-5.4) | 1.0 (0.2-5.1) | 0.37 |

| Moderate | 1.0 (0.8-1.5) | 2.5 (0.7-9.1) | 0.2 (0.0-1.7) | |

| Active | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Sunscreen use | ||||

| Always/most of the time | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.40 |

| Sometimes or rarely | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 1.3 (0.3-6.5) | 1.7 (0.4-7.1) | |

| Never | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 1.0 (0.2-4.2) | 2.0 (0.4-9.2) | |

| Multivitamin use | ||||

| None | 0.6 (0.5-0.9) | 0.4 (0.2-0.8) | 2.0 (0.6-7.2) | 0.02 |

| 1-6 times per week | 1.6 (0.9-3.0) | 0.5 (0.1-2.3) | 0.3 (0.0-2.7) | |

| Daily | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Adequate fruit/vegetable intake | ||||

| No (<4.5 cups/day) | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | 0.6 (0.1-4.0) | 0.8 (0.2-3.6) | 0.70 |

| Yes (≥4.5 cups/day) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Colorectal cancer screening | ||||

| within past 5 years | 1.0 | 1.0 | Non estimable | 0.95 |

| within past 6-10 | 1.1 (0.6-1.9) | 1.4 (0.3-7.5) | ||

| within >10 years | 0.9 (0.4-2.0) | 0.4 (0.0-4.2) | ||

| Breast cancer screening (mammogram) | ||||

| within past 2 years | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.47 |

| within past 3-5 | 0.4 (0.2-0.8) | 0.6 (0.1-3.1) | 0.4 (0.0-5.5) | |

| within >5 years | 0.7 (0.4-1.2) | 6.8 (1.4-33.4) | 0.4 (0.1-3.1) | |

| Cervical cancer screening (pap-smear) | ||||

| within past 2 years | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.19 |

| within past 3-5 | 0.5 (0.6-0.9) | 1.8 (0.2-20.4) | 2.2 (0.5-10.5) | |

| within >5 years | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) | 2.6 (0.3-24.9) | 0.3 (0.0-1.8) |

Adjusted for age, employment status, marital status, education, and insurance

Discussion

This study examined racial disparities in healthy behaviors among 2,427,075 breast cancer survivors and 57,978,043 respondents without cancer using data from 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Our findings suggest that associations of BMI with survivorship status differ by race. The distribution patterns for the examined healthy behaviors among cancer survivors and women without cancer in Caucasian, African American and Hispanic women suggest potential areas for tailored health education to address the needs of specific populations. However, most of the differences are suggestive and do not differ by race.

Our findings for healthy weight and physical activity are consistent with previous reports [30, 31]. Irwin et al. have found that African American women were less likely to have normal weight and to meet recommended levels of physical activity than either Caucasian or Hispanic women [30]. According to the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, more African American women reported being obese as compared to other races, regardless of their breast cancer status [31]. Our findings suggest that while current heavy alcohol use appears to be a concern among Hispanic breast cancer survivors as compared to their cancer-free counterparts, Caucasian women seem to be more likely to have ever used alcohol in their lifetime, regardless of their cancer survivorship status. Caucasian women also appear to be more likely to use sunscreen as compared to African American or Hispanic women, regardless of breast cancer history. However, inadequate fruit/vegetable intake remains a concern regardless of breast cancer status or race.

We find that a greater proportion of Hispanic women with a history of breast cancer adhere to recommended screening practices as compared to either Hispanic women without cancer or Caucasian and African American women. These findings are inconsistent with previously reported lower rates of screening among Hispanic women [32] and could be the result of the small number of breast cancer survivors included in this survey.

Compared to the prevalence of current smoking in all breast cancer survivors in an earlier NHIS analysis (14.1%) [33], the proportion of current smokers in our study was lower in Caucasian and Hispanic women, but was similar among African American survivors (14.8%). Proportion of breast cancer survivors engaging in moderate or vigorous physical activity in all three groups was higher than in the previous report (19.8%). The proportion of survivors with risky alcohol consumption levels in Caucasian and Hispanic survivors was similar to the overall prevalence in 2000 (4.7%); African American survivors had lower prevalence of heavy drinking. On the other hand, the adequate intake of fruits and vegetables was much lower in our study across all races as compared to previous reports (42.2%) and the proportion of survivors who never used sunscreen increased substantially since 2000 (3.6%) [33].

Comparison of our findings with earlier reports suggests that while some of the healthy behaviors have been improving among breast cancer survivors (such as smoking and physical acivity), others remained unchanged (alcohol consumption) or became less prevalent over time (sunscreen use, fruit/vegetable consumption). Alcohol consumption among Caucasian women and physical activity among African women remain a concern regardless of women's survivorship status, while sustaining healthy weight appears to be a problem in African American and Hispanic breast cancer survivors. These patterns indicate potential areas for preventive services that could be taiolored to address specific needs within each of the racial/ethnic groups.

This analysis uses the data from a large representative sample of the US population with oversampling of minority groups. Nonetheless, our study has a few limitations. The cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow us to establish any temporal relationships and to determine if the behaviors were influenced by the cancer diagnosis, which is likely. Both cancer diagnosis and healthy behaviors are self-reported. Previous studies demonstrated high accuracy of self-reported cancer diangnosis [34-36]. However, some reports suggest that self-reported data can underestimate the number of people with risky behaviors [37, 38]. It was also found that respondents tend to overestimate their screening practices [38-42] and that this overestimation can be more pronounced among African American and Hispanic respondents [40, 43]. This could, in part, explain higher rates of breast and colorectal cancer screening that we found in Hispanic breast cancer survivors and could explain the inconsistency of these results with those from previous studies that did not rely on self-reports. In addition, we did not look separately at the type of colorectal screening (fecal occult blood test [FOBT], sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, or barium enema). FOBT may be more common among non-whites and is a guideline recommended screening modality [44]. Finally, lower screening rates for cervical cancer among breast cancer survivors could be the result of higher total hysterectomy rates among the survivors as part of their cancer treatment. However, this cannot be determined with the current data since the type of hysterectomy is not reported.

Racial disparities in healthy behaviors among breast cancer survivors exist but remain poorly understood. Our findings suggest that certain population groups might benefit from tailored preventive service delivery that would address concerns related to selected healthy behaviors and screening practices among minorities, such as lack of physical activity and breast and cervical cancer screening among African American women and high prevalence of heavy alcohol consumption among Hispanic women.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Chang is supported by grant K01 HS022330 through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Drs. Chang and Colditz are supported by grant U54 CA 155496 through the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health and the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozols RF, Herbst RS, Colson YL, Gralow J, Bonner J, Curran WJ, Jr., Eisenberg BL, Ganz PA, Kramer BS, Kris MG, Markman M, Mayer RJ, Raghavan D, Reaman GH, Sawaya R, Schilsky RL, Schuchter LM, Sweetenham JW, Vahdat LT, Winn RJ, American Society of Clinical O Clinical cancer advances 2006: major research advances in cancer treatment, prevention, and screening--a report from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:146–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website, April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5814–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, Davis WW, Brown ML. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322–30. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:82–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keating NL, Norredam M, Landrum MB, Huskamp HA, Meara E. Physical and mental health status of older long-term cancer survivors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2145–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eakin EG, Youlden DR, Baade PD, Lawler SP, Reeves MM, Heyworth JS, Fritschi L. Health Status of Long-term Cancer Survivors: Results from an Australian Population-Based Sample. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15:1969–1976. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burstein HJ, Winer EP. Primary care for survivors of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1086–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010123431506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carver JR, Shapiro CL, Ng A, Jacobs L, Schwartz C, Virgo KS, Hagerty KL, Somerfield MR, Vaughn DJ. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical evidence review on the ongoing care of adult cancer survivors: cardiac and pulmonary late effects. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25:3991–4008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoff AO, Gagel RF. Osteoporosis in breast and prostate cancer survivors. Oncology. 2005;19:651–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivorship: the interface of aging, comorbidity, and quality care. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98:504–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown JK, Byers T, Doyle C, Coumeya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Kushi LH, McTieman A, Rock CL, Aziz N, Bloch AS, Eldridge B, Hamilton K, Katzin C, Koonce A, Main J, Mobley C, Morra ME, Pierce MS, Sawyer KA. Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: an American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2003;53:268–91. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.5.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:8884–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2003;58:82–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald PA, Williams R, Dawkins F, Adams-Campbell LL. Breast cancer survival in African American women: is alcohol consumption a prognostic indicator? Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2002;13:543–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1016337102256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hudson SV, Hahn KA, Ohman-Strickland P, Cunningham RS, Miller SM, Crabtree BF. Breast, colorectal and prostate cancer screening for cancer survivors and non-cancer patients in community practices. Journal of general internal medicine. 2009;24(Suppl 2):S487–90. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1036-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan NF, Carpenter L, Watson E, Rose PW. Cancer screening and preventative care among long-term cancer survivors in the United Kingdom. British journal of cancer. 2010;102:1085–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morey Mc SDCSR, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: Renew: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1883–1891. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demark-Wahnefried W, Pinto BM, Gritz ER. Promoting Health and Physical Function Among Cancer Survivors: Potential for Prevention and Questions That Remain. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:5125–5131. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolin KY, Colditz GA. Cancer and beyond: healthy lifestyle choices for cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:593–4. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colditz GA, Wolin KY, Gehlert S. Applying What We Know to Accelerate Cancer Prevention. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:127rv4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fairley TL, Hawk H, Pierre S. Health behaviors and quality of life of cancer survivors in Massachusetts, 2006: data use for comprehensive cancer control. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7:A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White A, Pollack L, Smith J, Thompson T, Underwood JM, Fairley T. Racial and ethnic differences in health status and health behavior among breast cancer survivors—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2009. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2013;7:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0248-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Center for Health Statistics . Data File Documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2005 (machine readable data file and documentation) National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville, Maryland: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans . 6th Edition U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: Jan, 2005. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2008. US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Cancer Institute . Five-Factor Screener in the 2005 NHIS Cancer Control Supplement, Applied Research Program. National Cancer Institute; 2007. Available from: http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/surveys/nhis/5factor/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Center for Health Statistics . Data File Documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2005 (machine readable data file and documentation) National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville, Maryland: 2006. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, Gilliland FD, Baumgartner R, Baumgartner K, Ballard-Barbash R. Physical activity levels among breast cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1484–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White A, Pollack LA, Smith JL, Thompson T, Underwood JM, Fairley T. Racial and ethnic differences in health status and health behavior among breast cancer survivors--Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2009. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0248-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Cancer screening—United States, 2010. MMWR. 2012;61(3):41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coups EJ, Ostroff JS. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michaud D, Midthune D, Hermansen S, Leitzmann M, Harlan L, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A. Comparison of Cancer Registry Case Ascertainment with SEER Estimates and Self-reporting in a Subset pf the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Journal of Registry Management. 2005;32:70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colditz G, Martin P, Stampfer M, Willett W, Sampson L, Rosner B, Hennekens C, Speizer F. Validation of questionnaite information on risk factors and disease outcomes in a prospective cohort study of women. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1986;123:894–900. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergmann MM, Calle EE, Mervis CA, Miracle-McMahill HL, Thun MJ, Health CW. Validity of self-reported Cancers in a Propsective Cohort Study in Comparison with Data from State Cancer Registries. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;147:556–562. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newell SA, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ. The accuracy of self-reported health behaviors and risk factors relating to cancer and cardiovascular disease in the general population: A critical review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1999;17:211–229. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, Pestone M, Dowling H, Offenbacher E, Weisel H, Heshka S, Matthews DE, Heymsfield SB. Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1893–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212313272701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiatt RA, Perezstable EJ, Quesenberry C, Sabogal F, Oterosabogal R, McPhee SJ. Agreement Between Self-Reported Early Cancer Detection Practices and Medical Audits Among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Health Plan Members in Northern California. Preventive Medicine. 1995;24:278–285. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Walk JA. Accuracy of Self-Reported Cancer-Screening Histories: A Meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17:748–757. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hall HI, Van Den Eeden SK, Tolsma DD, Rardin K, Thompson T, Hughes Sinclair A, Madlon-Kay DJ, Nadel M. Testing for prostate and colorectal cancer: comparison of self-report and medical record audit. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madlensky L, McLaughlin J, Goel V. A Comparison of Self-reported Colorectal Cancer Screening with Medical Records. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2003;12:656–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Champion VL, Menon U, McQuillen DH, Scott C. Validity of self-reported mammography in low-income African-American women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Debarros M, Steele SR. Colorectal cancer screening in an equal access healthcare system. J Cancer. 2013;4:270–80. doi: 10.7150/jca.5833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]