Abstract

Cognitive impairment is a major cause of morbidity in people with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and is associated with lower quality of life, more difficulty adhering to medications, and worse survival. Prior data suggest a relationship between vascular disease and cognitive impairment in individuals with CKD, although overall risk factors remain poorly understood. Critically, clinicians should be aware of the high rates of cognitive impairment that occur in all stages of CKD, which, although sometimes subtle, may impact comprehension and decision making in these individuals and may herald future, more debilitating impairment.

Cognitive impairment is a major cause of morbidity in chronic kidney disease (CKD). Individuals with cognitive impairment often have lower quality of life, have more difficult adhering to medications, and have worse survival1. Importantly, cognitive deficits become both more prevalent and more severe at lower levels of kidney function2. For patients with kidney failure treated with dialysis, this translates to a prevalence of cognitive impairment anywhere from 30–70%3,4.

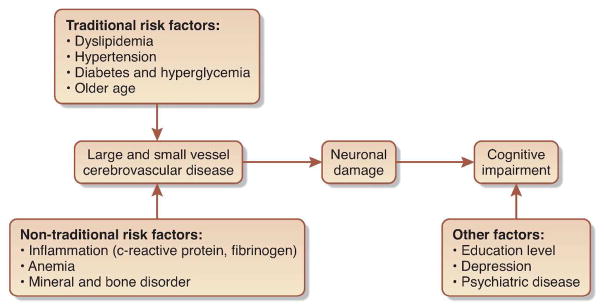

Reflecting the complex medical issues present in people with CKD, the cause of cognitive impairment likely is multifactorial in this population. Similar to the general population, aging patients with kidney disease can be at risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease, which initially affects memory most prominently; however, rates of Alzheimer’s in CKD patients appear similar to age- and sex-matched controls, therefore not explaining an observed excess of cognitive impairment5. In contrast, cerebrovascular disease is common in all stages of CKD, with the highest rates occurring in those treated with dialysis. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging in dialysis patients confirms a high burden of white matter disease, atrophy and cerebral infarcts, even in those without a known history of stroke6. Supporting the hypothesis that cerebrovascular disease is most responsible for cognitive impairment in people with CKD are several factors:

Neurocognitive manifestations of cerebrovascular disease predominantly affect executive function domains rather than memory and most prior studies of individuals with CKD reveal that executive function is more severely affected than other cognitive domains3,4,7,8;

Systemic cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular disease risk factors are associated with significantly worse executive function7;

In earlier stages of CKD, higher levels of albuminuria, likely representative of systemic vascular burden, are associated with both worse executive functioning and brain MRI findings5,9,10; and

More intensive dialysis with more effective clearance of uremic solutes does not improve cognitive function11.

In addition to a high burden of traditional cardiovascular vascular disease risk factors among individuals with CKD, non-traditional risk factors such as inflammation may be more prominent in individuals with CKD and may also predispose to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. Few data exist on how inflammation in individuals with CKD may contribute to abnormal brain function.

Attempting to address these questions, Sedeil et al performed a cross-sectional study evaluating cognitive performance in 119 patients with CKD stage 3–5D as well as 54 control subjects, all of whom had an eGFR > 60 ml/min/1.73m2 but an otherwise similar burden of vascular disease risk factors12. A battery of ten neurocognitive tests was used, the results of which were converted into a global cognitive score as well as three subscores comprising memory, executive function, and language domains.

Although overall similar with respect to many characteristics including age, education and several vascular disease risk factors, there were several key differences between the CKD group and controls in this study, including the rate of TIA or stroke (6% in CKD vs 0% in control) and levels of brain natriuretic peptide and fibrinogen (both higher in CKD). As would be expected, the CKD group performed modestly worse on multiple measures of cognition when compared to the control group. Thirty percent of the CKD group had poor global cognitive performance (defined as one standard deviation worse than the control group), while 18% had memory deficits and 38% executive deficits. In unadjusted comparisons, performance did not vary significantly by CKD stage, a finding that could be explained by the younger age of stage 5D patients compared to CKD stages 3–5 (55 vs 65 years), possibly suggesting that the effects of kidney failure on cognitive function are similar to 10 years of aging. Following adjustment for age, sex, and education, CKD stage was a strong predictor of global cognitive performance (with more advanced CKD associated with worse performance) but not for individual component domains.

Interestingly, the authors found a relationship between higher self-reported depression scores (using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) and lower global cognitive performance, a finding consistent with previous reports in dialysis that have demonstrated an association between depression symptoms and both poorer self-perceived and measured cognitive performance13,14. The association was attenuated when adjusting for markers of disease severity such as blood pressure, HbA1c, CKD stage and dyslipidemia, suggesting that comorbid conditions are involved in both depression and cognitive performance. Notably, one recent randomized clinical trial conducted in 72 hemodialysis patients with sleep disturbances evaluated the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy, a non-pharmacologic intervention for depression, and noted a significant improvement in depression scores as well as inflammatory markers in the group treated with cognitive behavioral therapy, potentially suggesting a mechanistic link among inflammation, sleep disturbances, depression and cognition15. In sum, the relationship between depression and cognitive performance is intriguing and deserving of further attention for future study, as unlike many other risk factors, depression is potentially modifiable, although few studies have assessed treatments for depression in hemodialysis patients.

Next, the investigators examined vascular disease risk factors and their association with cognitive performance. A key finding was that higher hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was associated with poorer global cognitive performance; this finding persisted even in models that adjusted for a previous history of CVD events as well as other traditional risk factors such as dyslipidemia, smoking, BMI, and systolic blood pressure. HbA1c has been linked with cognitive performance in people with type 2 diabetes, but this has not previously been extended to patients with advanced CKD. Unfortunately, it is difficult to interpret what this finding means for patients with CKD as HbA1c measurement in kidney disease remains poorly validated, with recent studies demonstrating that HbA1c measurement does not accurately reflect long term blood sugar levels and thus may substantially underestimate the degree of hyperglycemia in this population16. Future studies of cognition could be well served to consider alternative measures of glycemic control to investigate this potentially important risk factor.

An additional finding was an association between higher fibrinogen level and worse memory and executive function, a finding which was attenuated in the main multivariable model. Fibrinogen, a marker of inflammation, is associated with cognitive performance in the general population, specifically with poorer performance on tests that identify vascular dementia17, and, in individuals with stage 3–4 CKD, higher levels of fibrinogen are associated with cardiovascular disease outcomes18. Therefore, it was unexpected that the association between fibrinogen and memory was the more robust association in this study, raising the question of residual confounding. C-reactive protein (CRP), another well studied marker of inflammation, was not assessed in this study. Although both higher CRP and rising CRP over time are associated with the development of cognitive impairment in elderly populations19, few studies have looked at CRP and cognitive performance in kidney disease despite the association of high CRP with a multitude of cardiovascular outcomes. Well designed longitudinal studies that include multiple measures of inflammation will likely be required to better explore the impact of inflammation and its modifiers on cognitive performance.

In sum, even when compared to a population enriched for CVD and CVD risk factors, individuals with CKD performed modestly worse on a cognitive battery testing multiple domains. Despite the many caveats that are associated with a cross-sectional study as well as this study’s modest sample size, these findings, when viewed in context of existing data, suggest that risk factors for cerebrovascular disease may be particularly important in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in people with CKD. Critically, clinicians should be aware of the high rates of cognitive impairment that occur even in earlier stages of CKD. Although initial cognitive deficits may be subtle, these deficits may herald future, more debilitating impairment. Future studies should evaluate whether treatments targeting vascular disease risk factors, possibly including inflammation, can prevent or slow the development of cognitive impairment in individuals with CKD.

Figure 1.

Figure Proposed mechanisms of Cognitive Impairment in CKD

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Drew is funded by the American Society of Nephrology Research Fellowship Program. Dr. Weiner’s work on cognition in kidney disease is funded via NIH NIDDK R01 DK090401.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Neither Dr. Weiner nor Dr. Drew have financial interests in this subject matter.

References

- 1.Griva K, Stygall J, Hankins M, et al. Cognitive impairment and 7-year mortality in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(4):693–703. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurella M, Chertow GM, Luan J, et al. Cognitive Impairment in Chronic Kidney Disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(11):1863–1869. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Scott TM, et al. Frequency of and risk factors for poor cognitive performance in hemodialysis patients. Neurology. 2013;80(5):471–480. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f0f7f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, et al. Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology. 2006;67(2):216–223. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000225182.15532.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seliger SL, Siscovick DS, Stehman-Breen CO, et al. Moderate renal impairment and risk of dementia among older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. J Am So Nephrol. 2004;15(7):1904–1911. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000131529.60019.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drew DA, Bhadelia R, Tighiouart H, et al. Anatomic brain disease in hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(2):271–278. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner DE, Scott TM, Giang LM, et al. Cardiovascular Disease and Cognitive Function in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(5):773–781. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalirao P, Pederson S, Foley RN, et al. Cognitive impairment in peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(4):612–620. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiner DE, Bartolomei K, Scott T, et al. Albuminuria, Cognitive Functioning, and White Matter Hyperintensities in Homebound Elders. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(3):438–447. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barzilay JI, Fitzpatrick AL, Luchsinger J, et al. Albuminuria and dementia in the elderly: a community study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(2):216–226. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurella Tamura M, Unruh ML, et al. Effect of More Frequent Hemodialysis on Cognitive Function in the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(2):228–237. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seidel UK, Gronewald J, Volsek M, et al. Cognitive impairment in chronic kidney disease: Prevalence, severity and association with HbA1c and fibrinogen. Kidney Int. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.366. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorensen EP, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, et al. The kidney disease quality of life cognitive function subscale and cognitive performance in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(3):417–426. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agganis BT, Weiner DE, Giang LM, Scott T, Tighiouart H, Griffith JL, et al. Depression and cognitive function in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(4):704–712. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen H-Y, Cheng I-C, Pan Y-J, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for sleep disturbance decreases inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2011;80(4):415–422. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peacock T, Shihabi Z, Bleyer A, et al. Comparison of glycated albumin and hemoglobin A1c levels in diabetic subjects on hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2008;73(9):1062–1068. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Oijen M, Witteman JC, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MM. Fibrinogen is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Stroke. 2005;36(12):2637–2641. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000189721.31432.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF, et al. The relationship between nontraditional risk factors and outcomes in individuals with stage 3 to 4 CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(2):212–223. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenny NS, French B, Arnold AM, et al. Long-term assessment of inflammation and healthy aging in late life: the Cardiovascular Health Study All Stars. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(9):970–976. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]