Abstract

High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) is a late mediator of the systemic inflammation associated with sepsis. Recently, HMGB1 has been shown in animals to be a mediator of hemorrhage-induced organ dysfunction. However, the time course of plasma HMGB1 elevations after trauma in humans remains to be elucidated. Consequently, we hypothesized that mechanical trauma in humans would result in early significant elevations of plasma HMGB1. Trauma patients at risk for multiple organ failure (ISS ≥15) were identified for inclusion (n = 23), and postinjury plasma samples were assayed for HMGB1 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Comparison of postinjury HMGB1 levels with markers for patient outcome (age, injury severity score, units of red blood cell (RBC) transfused per first 24 h, and base deficit) was performed. To investigate whether postinjury transfusion contributes to elevations of circulating HMGB1, levels were determined in both leuko-reduced and non–leuko-reduced packed RBCs. Plasma HMGB1 was elevated more than 30-fold above healthy controls within 1 h of injury (median, 57.76 vs. 1.77 ng/mL; P < 0.003), peaked from 2 to 6 h postinjury (median, 526.18 ng/mL; P < 0.01 vs. control), and remained elevated above control through 136 h. No clear relationship was evident between postinjury HMGB1 levels and markers for patient outcome. High-mobility group box 1 levels increase with duration of RBC storage, although concentrations did not account for postinjury plasma levels. Leuko-reduced attenuated HMGB1 levels in packed RBCs by approximately 55% (P < 0.01). Plasma HMGB1 is significantly increased within 1 h of trauma in humans with marked elevations occurring from 2 to 6 h postinjury. These results suggest that, in contrast to sepsis, HMGB1 release is an early event after traumatic injury in humans. Thus, HMGB1 may be integral to the early inflammatory response to trauma and is a potential target for future therapeutics.

Keywords: Critical care, shock, inflammation, resuscitation, multiple organ failure, injury severity, transfusion, leukoreduction

INTRODUCTION/BACKGROUND

High-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) was first described more than 30 years ago as a nuclear DNA binding protein that supports nucleosome structure and facilitates DNA transcription (1). The protein is also selectively released from activated macrophages and other cell populations (2). In the extracellular compartment, HMGB1 acts as a potent proinflammatory mediator, particularly after binding to LPS, DNA, or proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β (3–5). The role of HMGB1 as a participant in proinflammatory responses was first described in sepsis (2) but has subsequently been extended to hemorrhage, ventilator-induced lung injury, and arthritis (6–11).

The interaction of HMGB1 with Toll-like receptor 2, Toll-like receptor 4, or the receptor for advanced glycation end-products induces nuclear translocation of nuclear factor–κB in neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages, resulting in increased production and release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) 1α, and macrophage inflammatory protein 1β (2, 12–14). Increased cellular secretion of HMGB1 seems to be a relatively late event in models of endotoxemia, occurring several hours after engagement of LPS stimulation. Circulating levels of HMGB1 are elevated for prolonged periods in sepsis and severe infection. In murine models, HMGB1 is detectable in serum 8 h after administration of LPS or TNF-α, with peak levels occurring from 16 to 32 h (2). In humans with sepsis, plasma HMGB1 levels correlate with degree of organ dysfunction and begin to diverge between survivors and nonsurvivors predicting mortality by day 3 after admission levels. High-mobility group box 1 remains elevated for up to 7 days after admission in septic patients, well after other cytokine levels have normalized, supporting its role as a late mediator of systemic inflammation with sepsis (2, 15, 16).

High-mobility group box 1 is also associated with systemic inflammation and remote organ dysfunction resulting from sterile trauma, including bilateral femur fracture, hepatic I/R injury, and hemorrhagic shock. In each of these experimental models, the severity of organ injury is attenuated by administration of anti-HMGB1 antibodies (7, 9, 17, 18). Circulating HMGB1 was found to be elevated in a case report of a patient with life-threatening hemorrhage (8), and elevated serum levels have been reported after hemorrhagic shock in humans (9).

Although HMGB1 can contribute to systemic inflammation after sterile injury, and levels correlate with organ failure in humans with sepsis, the time course and magnitude of elevation after severe accidental trauma in humans remain to be elucidated. Consequently, we explored the relationship between mechanical trauma in humans and the pattern of changes in plasma HMGB1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection

Blood samples were collected from adult trauma patients admitted to the surgical intensive care unit at Denver Health Medical Center and entered into a National Institutes of Health–sponsored Human Subjects Core Tissue Bank in accordance with a Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board–approved protocol. Denver Health Medical Center is one of the core teaching hospitals for the University of Colorado Denver. Patients identified for inclusion were 18 years of age or older with an injury severity score (ISS) greater than or equal to 15. Patients with isolated head injury were excluded from this study. Previously drawn blood samples (in EDTA-coated tubes) ordered for clinical indications, which were either duplicate or subsequently unused, were obtained from the central laboratory and processed within 24 h. Patient blood samples were anonymized and assigned a tissue bank number for identification. All data were stored on a secure server managed by the hospital.

Plasma samples collected from 12 healthy volunteers served as controls.

Processing of blood samples

Blood samples were centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min to separate cellular components from the plasma, after which the acellular supernatants were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min to purify the plasma of platelet contamination. Aliquots of the supernatant were stored at −80°C in low-retention, polypropylene, microcentrifuge tubes (Fisher Scientific).

Determination of plasma HMGB1 levels

Plasma samples were assayed for HMGB1 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Immunoreactive HMGB1 was quantified using a commercially available HMGB1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit II according to the manufacturer’s instructions (SHINO-TEST CORPORATION, Sagamihara, Japan) (19, 20).

Packed red blood cell collection

Whole blood (450 mL) was collected from five healthy volunteer donors after obtaining informed consent under a Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board–approved protocol at the University of Colorado Denver. Each unit was then divided by equal weight, with one half being leuko-reduced via filtration (Pall BPF4 leukoreduction filter; Pall Corp, Westbury, NY) and stored at 4°C according to American Association of Blood Banks standards (21). Sterile couplers were used to obtain serial samples throughout the storage interval on days 1 and 42 (the last day a unit can be transfused). The plasma fraction was isolated via standard techniques and stored at −80°C (21).

Statistical analysis

Temporal changes in plasma HMGB1 levels were analyzed, and least square means (also known as “adjusted” mean) were calculated using mixed linear models for repeated measures (SAS, Proc Mixed). This method allows for testing of different covariance structures and permits the use of all the data in unbalanced designs. We developed two models, including 1) HMGB1 values at less than 1, 2 to 6, 7 to 12, 13 to 24, 25 to 48, 49 to 72, and 73 to 136 h; 2) peak HMGB1 values adjusted for age, indicators of injury severity, and shock. Correlation between peak HMGB1 levels and patient age, number of units of packed red blood cells (RBCs) transfused per first 24 h, ISS, and admission base deficit (BD) were evaluated using the nonparametric Spearman method.

A linear mixed model for repeated measures was used to analyze the effects of storage time and leukoreduction on HMGB1 levels in donor packed RBCs. Correction for multiple comparisons was done using a Tukey post hoc test.

For all statistical comparisons, a P value of less than 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Trauma population characteristics

Patient characteristics are given in the Table 1. Plasma samples stored in the Human Subjects Core Tissue Bank from 23 adult trauma patients (16 men and 7 women) admitted to the surgical intensive care unit from May 2006 to October 2007 were assayed for HMGB1. The mechanism of injury was penetrating trauma in 6 patients (26%) and blunt trauma in 17 patients. The median age of patients was 33 years (range, 18–88 years). Patient median ISS was 29 (range, 17–57). Base deficit at the time of admission was recorded for 21 of 23 patients (median, 8.0; range, 2.0–23.0). Transfusion of packed RBCs within the first 24 h after injury occurred in 11 patients (48%) and ranged in volume from 1 to 13 U. Only previously drawn, and subsequently unused blood samples, were collected from the laboratory for analysis. Thus, individual patient data sets were not necessarily available for all of the seven time periods after trauma. The median number of time periods sampled per patient was 4 (range, 1–6). All patients survived through 136 h; two patients were discharged from the hospital on postinjury day 5, and one patient died on postinjury day six. This patient had samples drawn through the 73- to 136-h time period. No patients in this study population were transferred to other facilities within the study period.

Table 1.

Trauma population characteristics

| No. Trauma Patients | 23 | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 16 (70%) | |||

| Female | 7 (30%) | |||

| Blunt trauma | 17 (74%) | |||

| Penetrating trauma | 6 (26%) | |||

| Age, yr | 18–88 | 35.0 | 33.0 | 17.0 |

| ISS | 17–57 | 30.9 | 29.0 | 9.6 |

| BD | 2–23 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 5.3 |

| Units RBC in first 24 h | 0–13* | 3.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

RBC transfusion within 24 h after injury occurred in 11 (48%) of 23 patients.

Plasma HMGB1 levels after trauma

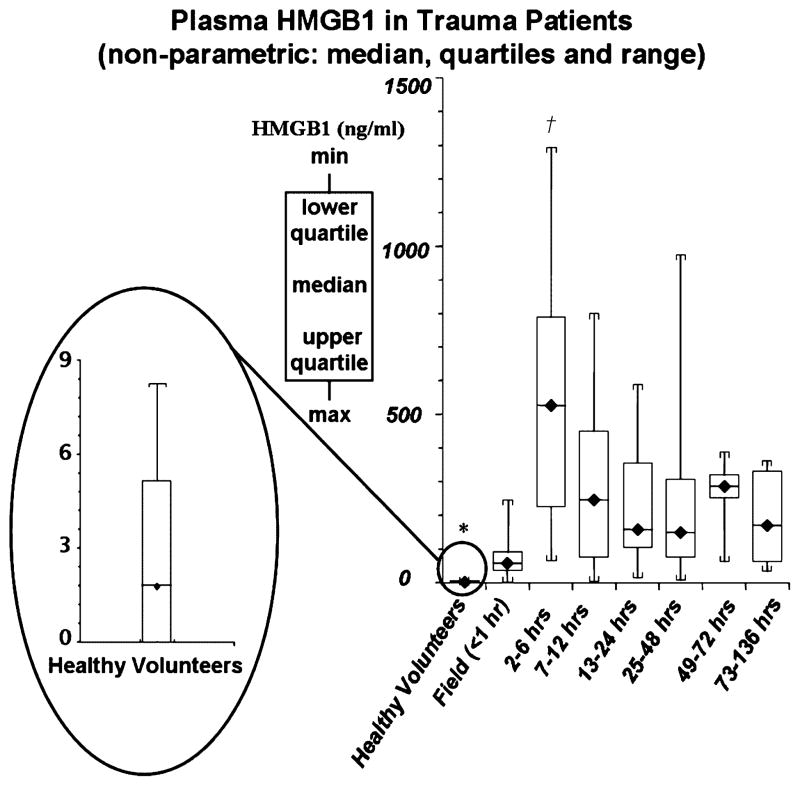

The postinjury time course of plasma HMGB1 compared with levels in healthy volunteers is given in Figure 1. Low levels of circulating HMGB1 were found in plasma from healthy volunteers (median, 1.77 ng/mL; range, 0–8.24 ng/mL). Within 1 h of traumatic injury, plasma HMGB1 was markedly elevated above baseline (median, 57.76 ng/mL; range, 2.51–246.23 ng/mL). This represents a greater than 30-fold increase in circulating HMGB1 levels immediately after trauma (P < 0.003 vs. healthy volunteers). Plasma HMGB1 peaked from 2 to 6 h after injury (median, 526.18 ng/mL; range, 64.17–1179.98 ng/mL; P < 0.01 vs. time periods <1 to 136 h) and remained elevated above levels present in healthy volunteers through 136 h postinjury (P < 0.003). We evaluated HMGB1 levels at each time point through 136 h using a mixed linear model with least square means adjusted for injury mechanism (penetrating vs. blunt trauma). In this study population, with 6 patients (16%) having penetrating trauma and 17 patients admitted with blunt trauma, no statistical difference was observed when HMGB1 levels were adjusted for injury mechanism.

Fig. 1. Plasma HMGB1 concentrations in trauma patients from less than 1 to 136 h postinjury.

Compared with healthy volunteers, plasma HMGB1 was markedly elevated in trauma patients within 1 h of injury (median, 57.76 vs. 1.77 ng/mL; healthy volunteers vs. all time periods; *P < 0.003). Peak plasma HMGB1 levels, approximately 300-fold above levels in healthy volunteers, occurred from 2 to 6 h postinjury (median, 526.18 ng/mL; †P < 0.01 vs. time periods <1 to 136 h). After peak levels, from 2 to 6 h, plasma HMGB1 remained elevated above healthy volunteers through 136 h postinjury (*P < 0.003).

Relationship between plasma HMGB1 and indicators of shock, ISS, and patient age

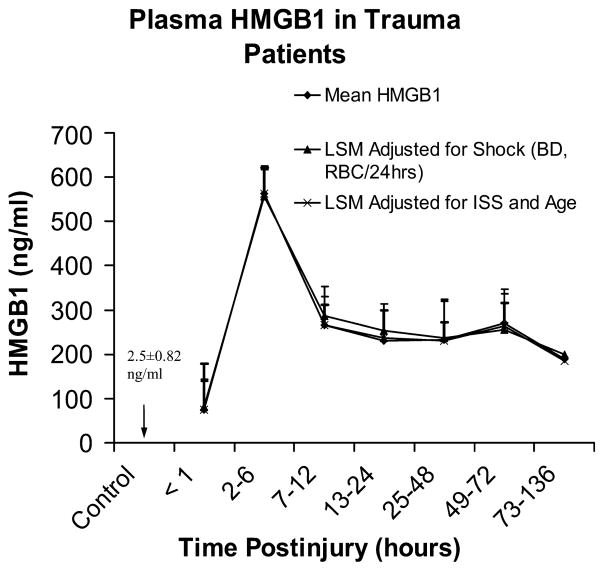

Base deficit at the time of admission and the number of units of RBC transfused in the first 24 h after injury are indicators of shock severity and predict risk of multiple organ failure and mortality after trauma (22–24). Additionally, ISS and patient age are independent risk factors for mortality after trauma (22, 25). We therefore evaluated postinjury HMGB1 levels adjusted for indicators of shock (BD, number of units of RBC per first 24 h), and ISS as well as patient age to determine if a relationship exists between HMGB1 concentration and these markers for outcome after trauma. Interestingly, no significant difference was observed when plasma HMGB1 levels were adjusted for indicators of shock, injury severity, or patient age through 136 h after injury (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Relationship between plasma HMGB1 and indicators of shock, ISS, and patient age.

Comparison of mean HMGB1 levels with least square means (LSM) adjusted for indicators of shock (admission BD and units RBC transfused per first 24 h), or LSM adjusted for ISS and patient age was performed. No significant difference was observed when plasma HMGB1 levels were adjusted for indicators of shock or injury severity and patient age to 136 h after injury (values represent mean or LSM ± SEM).

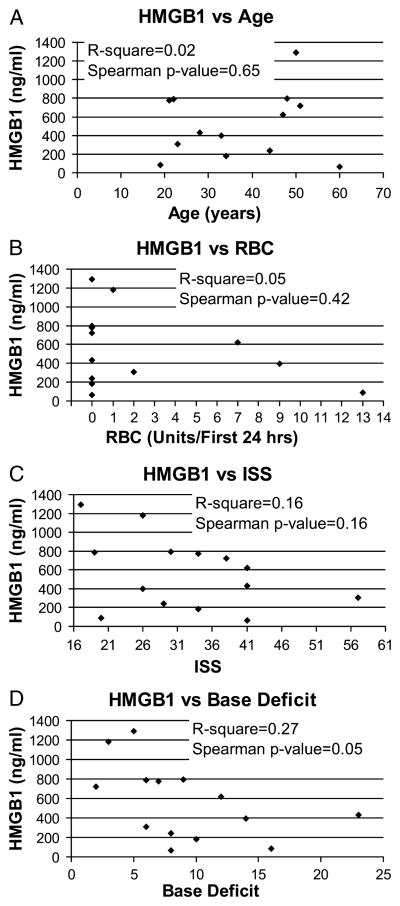

Maximal postinjury plasma HMGB1 versus patient age, indicators of shock, and injury severity

To further evaluate whether postinjury HMGB1 levels correlate with prognostic markers for patient outcome, we evaluated peak plasma concentrations of HMGB1 (from 2 to 6 h postinjury) independently against patient age, number of units of RBCs transfused per first 24 h, ISS, and admission BD (Fig. 3, A–D). No clear relationship was found between peak postinjury HMGB1 levels and patient age, ISS, transfusion requirement in the first 24 h, or BD at admission. A possible inverse correlation between peak HMGB1 levels and BD at admission may exist; however, this trend borders on statistical significance and would require further investigation in a larger number of patients (Spearman P value = 0.05).

Fig. 3. Maximal postinjury plasma HMGB1 versus patient age, indicators of shock, and injury severity.

Peak HMGB1 levels, from 2 to 6 hours postinjury, were evaluated independently against patient age (A), number of units of RBCs transfused per first 24 h (B), ISS (C), or admission BD (D). No clear relationship was found between peak postinjury HMGB1 levels and patient age (P = 0.65), ISS (P = 0.16), or transfusion requirement in the first 24 h (P = 0.42). A possible inverse correlation may exist between peak HMGB1 levels and BD at the time of admission. However, this trend borders on statistical significance (Spearman P value = 0.05) and requires further investigation.

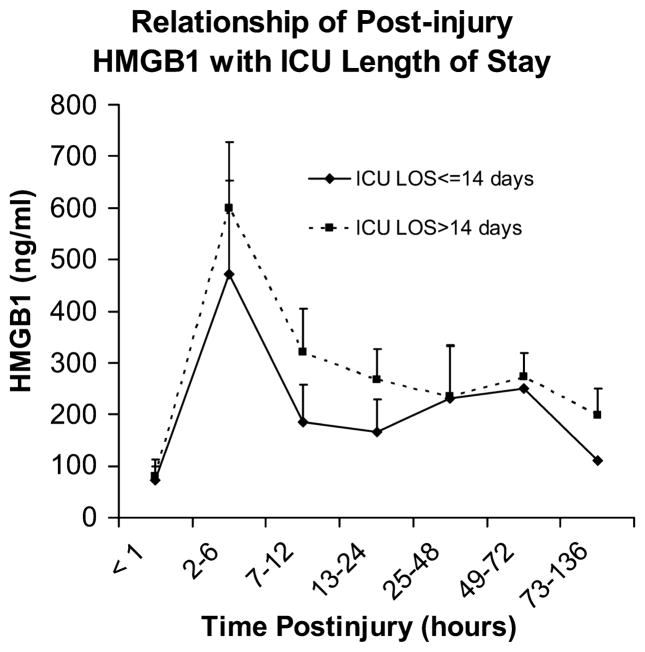

Plasma HMGB1 levels trend higher in patients requiring longer intensive care unit stays

Plasma HMGB1 levels after trauma were consistently higher for patients requiring intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS) greater than 14 days when compared with levels observed in patients who had shorter ICU stays (Fig. 4). Although not statistically significant (mixed model, P = 0.499) this difference was most apparent during the first 24 h after injury.

Fig. 4. Plasma HMGB1 levels trend higher in patients requiring longer ICU stays.

Patients requiring ICU LOS greater than 14 days had consistently higher plasma HMGB1 levels than did patients requiring ICU LOS less than or equal to 14 days. This trend was most apparent during the first 24 h after injury; however, in this small study population, it did not reach statistical significance (mixed model, 0.499) and requires further investigation.

HMGB1 in transfused packed RBCs does not account for plasma levels seen after injury

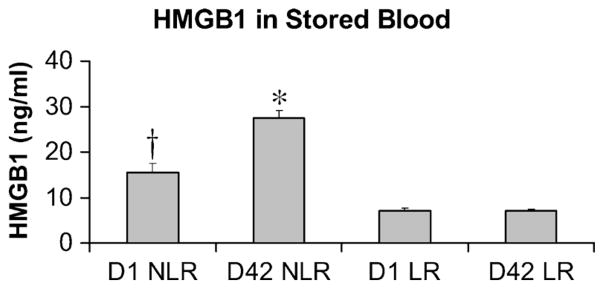

Eleven patients (48%) in this study population received RBC transfusion within the first 24 h after injury. To determine whether HMGB1 was present in stored RBCs and contributed to postinjury elevations of plasma HMGB1, we assayed packed RBCs from five healthy donors for HMGB1. Donor packed RBCs were assayed for HMGB1 in both leuko-reduced (LR) and non–leuko-reduced (NLR) samples at days 1 (D1) and 42 (D42) after collection (Fig. 5). We found that HMGB1 concentrations in stored packed RBCs are dependent on the duration of storage and whether the blood products underwent leukoreduction. Day 42–NLR RBCs contained 1.7-fold higher concentrations of HMGB1 than did D1-NLR RBCs (27.3 ± 1.6 vs. 15.4 ± 2.3 ng/mL; mean ± SEM; P < 0.001). No difference was detected in HMGB1 levels between D1 and D42 LR blood. Leukoreduction attenuated HMGB1 levels in stored blood by approximately 55% versus D1-NLR RBCs (7 ± 0.7 vs. ± 15.4 2.3 ng/mL; P < 0.01) and by approximately 75% versus D42-NLR RBCs (7 ± 0.5 vs. 27.3 ± 1.6 ng/mL; P < 0.001). Stored packed RBCs transfused during this study period (May 2006–October 2007) were NLR. Given the marginal concentration of HMGB1 in D42-NLR RBCs, peak plasma levels of HMGB1, observed from 2 to 6 h postinjury, are not directly attributable to the administration of HMGB1 contained in a transfusion of up to 13 U of stored RBCs (most units received by a single patient during the first 24 h after trauma).

Fig. 5. Concentrations of HMGB1 in stored packed RBCs are dependent on the duration of storage and whether the blood products underwent leukoreduction.

Plasma HMGB1 was assayed for in both LR and NLR blood samples, from five healthy donors, at D1 and D42 after storage. High-mobility group box 1 concentration increased in NLR samples approximately 1.7-fold with 42 days of storage (15.4 ± 2.3 ng/mL D1 NLR vs. 27.3 ± 1.6 ng/mL D42 NLR; mean ± SEM, *P < 0.001 vs. D1 NLR). Leukoreduction attenuated HMGB1 levels by approximately 55% versus D1 NLR blood (†P < 0.01 vs. D1 and D42 LR RBCs), and by approximately 75% versus D42 NLR blood (*P < 0.001 vs. D1 and D42 LR RBCs). Attenuation of HMGB1 levels was durable for 42 days of storage, with no difference observed in levels between D1 LR and D42 LR RBCs.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study demonstrate that circulating HMGB1 is markedly increased within 1 h of traumatic injury in humans. Peak elevations of plasma HMGB1 (~300-fold above control) were observed from 2 to 6 h postinjury, with levels remaining elevated above baseline through 136 h after trauma. No clear relationship was evident between postinjury HMGB1 levels and patient age, ISS, units of RBC transfusion during the first 24 h, or admission BD. Additionally, we found that HMGB1 levels at early time points after injury were consistently higher in patients requiring ICU LOS greater than 14 days as compared with levels observed in patients with shorter ICU stays.

Processing and length of storage affect the concentration of HMGB1 in donor packed RBCs. Specifically, leukoreduction attenuates the level of HMGB1 in packed RBCs, an effect that persists with blood product storage for 42 days. High-mobility group box 1 levels increase with duration of storage in NLR packed RBCs. However, the magnitude of this increase does not account for the plasma levels observed in patients after trauma.

This study is limited by a small study population of severely injured trauma patients. All patients included had an ISS greater than or equal to 15, which may obscure differences in HMGB1 concentrations from a less injured population. The small sample size may also lead to an underestimation of relationships between HMGB1 and prognostic markers for patient outcome. Only one patient in this series developed adult respiratory distress syndrome, and only one patient died within 30 days of injury, preventing any direct examination of the relationship between HMGB1 with those outcomes. Future research, with a more focused target population and larger number of patients (i.e., ventilated patients with posttrauma adult respiratory distress syndrome), might further elucidate these potential relationships with HMGB1 levels.

The Human Subjects Core Tissue Bank used for sample analysis in this study provides a valuable resource for observational investigations related to trauma. However, retrospective analysis of plasma samples necessitates analysis of “time periods” after trauma as opposed to collection at designated time points in a prospective fashion. To expand on our results, a larger, prospectively designed study would be necessary.

High-mobility group box 1 is a well-recognized late mediator of inflammation, organ system dysfunction, and mortality associated with sepsis (2, 26–29). Sentinel work by Wang et al. (2) demonstrated that HMGB1 is actively released from inflammatory cells in response to LPS and cytokine stimulation, and that circulating levels of HMGB1 are elevated in both mice after LPS exposure and humans with septic shock. These initial observations expanded the understanding of HMGB1’s function to include a role as a proinflammatory mediator after selective cellular release in response to noxious stimuli. The time course of HMGB1 elevation in patients with sepsis was initially described by Sunden-Cullberg et al. (16), and work by Gibot et al. (15) showed that circulating levels of HMGB1 on day 3 after admission diverge between survivors and nonsurvivors, with higher levels predicting mortality. In animal models of sepsis, treatment with anti-HMGB1 antibodies reduces mortality associated with sepsis. This therapeutic benefit is realized even when treatment is delayed as long as 24 h after the inciting infectious event (27, 30). Such findings highlight HMGB1’s potential use not only as a prognostic marker for outcome in critical illness but also as a therapeutic target for intervention in the setting of inflammatory disease.

Trauma remains a leading cause of death in the United States, and for patients who survive the initial injury, many will suffer or die from postinjury multiple organ failure (31, 32). Identification of mediators in this pathology may provide targets for therapeutic intervention. Building on knowledge from research in sepsis, HMGB1 has been identified as a key mediator of systemic inflammation and remote organ injury associated with sterile trauma in experimental models (7, 9, 17, 18). The use of anti-HMGB1 antibodies in animal models of trauma attenuates proinflammatory cytokine levels and diminishes the degree of postinjury organ dysfunction, including acute lung injury associated with hemorrhagic shock (7, 9, 17, 18). Elevated circulating HMGB1 has been described in a case report of a patient with hemorrhagic shock secondary to ruptured AAA (8), and work by Yang et al. (9) noted that elevated serum HMGB1 is detectable within 6 h of hemorrhagic shock in humans. The role of HMGB1 in post-trauma inflammation and organ dysfunction makes it a potential target for therapy directed at reducing postinjury morbidity and mortality.

Our findings confirm the results of Yang et al. that, in contrast to observations made in patients with sepsis, HMGB1 release into circulation occurs early after trauma. Surprisingly, plasma HMGB1 levels from patients in this study were elevated up to 30-fold above baseline within the first hour after injury (median, 57.76 ng/mL; range, 2.51–246.23 ng/mL). This magnitude of elevation compares with that observed by Yang et al. within the first 6 h after hemorrhagic shock (median, 54 ng/mL; range, 25.1–162.9 ng/mL). However, a distinct difference between the present study and that of Yang et al. is that plasma HMGB1 levels continued to rise, reaching peak levels from 2 to 6 h postinjury (median, 526.18 ng/mL; range, 64.17–1,179.98 ng/mL;). Thus, plasma HMGB1 is elevated greater than 30-fold immediately after trauma; peak levels from 2 to 6 h postinjury are elevated approximately 300-fold above control. These peak levels are nearly 10-fold greater than previously reported in humans with hemorrhagic shock. The early postinjury changes, and the magnitude of elevation, in circulating HMGB1 levels are distinctly different from what has been reported in humans with sepsis, where peak circulating HMGB1 concentrations occur days after admission with median levels less than 100 ng/mL (2, 15, 16).

Recognizing the limitations of a small study population and heterogeneous group of severely injured patients, no clear relationship was evident between postinjury HMGB1 levels and patient age, ISS, number of units of RBC transfused per first 24 h, or admission BD. Interestingly, patients with higher plasma HMGB1 levels consistently had longer ICU LOS. This trend is most apparent during the first 24 h after injury, and although it did not reach statistical significance, a potential relationship may have been limited by the small study population.

Many severely injured trauma patients require transfusion of packed RBCs during initial stabilization and support. Low levels of HMGB1 are present in NLR RBCs. These levels increase with duration of storage for 42 days, which is the longest storage time for blood that can be used for transfusion (21). However, our findings indicate that plasma HMGB1 levels after trauma are not directly attributable to the administration of HMGB1 contained within transfused packed RBCs. Nevertheless, other components of transfused blood may have immunomodulatory effects in the recipient with the potential to enhance or suppress production of HMGB1. The effect packed RBC transfusion has on immunomodulation of HMGB1 production and release is an area for future research. Although levels of HMGB1 in packed RBCs are not of a magnitude to explain the plasma levels observed after trauma, they do suggest that HMGB1 may be a potential mediator of posttransfusion pathophysiology. Leukoreduction attenuates baseline levels of HMGB1 in donor RBCs by approximately 55% on day 1, an effect that is durable through 42 days of storage. This finding suggests a potential benefit for the use of leukoreduction before packed RBC storage for use in post-injury resuscitation.

In summary, the results of the present study indicate that, in contrast to sepsis, HMGB1 release into circulation is an early event after trauma, with peak levels markedly higher than those previously reported occurring from 2 to 6 h postinjury. Thus, postinjury, systemic release of HMGB1 in humans may be integral to the early inflammatory response to trauma and is a potential target for future therapeutics. Recent studies have shown that HMGB1 itself has little proinflammatory activity and only becomes highly active after association with other mediators of inflammation such as LPS, cytokines, or DNA. Therefore, an important issue in any patient-based study of HMGB1 is to determine what cofactors are bound to HMGB1 at the time points examined. Prospective studies with larger patient populations are required to examine this issue and to further characterize the relationship of postinjury HMGB1 with patient outcome and other markers of injury severity. The source of HMGB1 and the precise mechanism for its early release after trauma remain unknown. Several hypotheses regarding the source of posttraumatic HMGB1 exist, including passive release from local tissue injury or necrotic cells, selective release from activated inflammatory cells, and selective release from tissues distant to the site of injury. These mechanistic questions remain areas for further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant nos. T32-GM008315 and P50-GM049222). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the US National Institute of General Medical Sciences or National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Goodwin GH, Sanders C, Johns EW. A new group of chromatin-associated proteins with a high content of acidic and basic amino acids. Eur J Biochem. 1973;38(1):14–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb03026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, et al. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285(5425):248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouhiainen A, Tumova S, Valmu L, Kalkkinen N, Rauvala H. Pivotal advance: analysis of proinflammatory activity of highly purified eukaryotic recombinant HMGB1 (amphoterin) J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(1):49–58. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sha Y, Zmijewski J, Xu Z, Abraham E. HMGB1 develops enhanced proinflammatory activity by binding to cytokines. J Immunol. 2008;180(4):2531–2537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao SY, Chen B, Senthil K, Wu H, Parroche P, Drabic S, Golenbock D, Sirois C, et al. Toll-like receptor 9–dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(5):487–496. doi: 10.1038/ni1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Zoelen MA, Ishizaka A, Wolthuls EK, Choi G, van der Poll T, Schultz MJ. Pulmonary levels of high-mobility group box 1 during mechanical ventilation and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Shock. 2008;29(4):441–445. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318157eddd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim JY, Park JS, Strassheim D, Douglas I, Diaz del Valle F, Asehnoune K, Mitra S, Kwak SH, Yamada S, Maruyama I, et al. HMGB1 contributes to the development of acute lung injury after hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288(5):L958–L965. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00359.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ombrellino M, Wang H, Ajemian MS, Talhouk A, Scher LA, Friedman SG, Tracey KJ. Increased serum concentrations of high-mobility-group protein 1 in haemorrhagic shock. Lancet. 1999;354(9188):1446–1447. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02658-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang R, Harada T, Mollen KP, Prince JM, Levy RM, Englert JA, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Yang L, Yang H, Tracey KJ, et al. Anti-HMGB1 neutralizing antibody ameliorates gut barrier dysfunction and improves survival after hemorrhagic shock. Mol Med. 2006;12(4–6):105–114. doi: 10.2119/2006-00010.Yang. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kokkola R, Sundberg E, Ulfgren AK, Palmblad K, Li J, Wang H, Ulloa L, Yang H, Yan XJ, Furie R, et al. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1: a novel proinflammatory mediator in synovitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(10):2598–2603. doi: 10.1002/art.10540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taniguchi N, Kawahara K, Yone K, Hashiguchi T, Yamakuchi M, Goto M, Inoue K, Yamada S, Ijiri K, Matsunaga S, et al. High mobility group box chromosomal protein 1 plays a role in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis as a novel cytokine. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(4):971–981. doi: 10.1002/art.10859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersson U, Wang H, Palmblad K, Aveberger AC, Bloom O, Erlandsson-Harris H, Janson A, Kokkola R, Zhang M, Yang H, et al. High mobility group 1 protein (HMG-1) stimulates proinflammatory cytokine synthesis in human monocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;192(4):565–570. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park JS, Arcaroli J, Yum HK, Yang H, Wang H, Yang KY, Choe KH, Strassheim D, Pitts TM, Tracey KJ, Abraham E. Activation of gene expression in human neutrophils by high mobility group box 1 protein. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284(4):C870–C879. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00322.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park JS, Svetkauskaite D, He Q, Kim JY, Strassheim D, Ishizaka A, Abraham E. Involvement of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in cellular activation by high mobility group box 1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(9):7370–7377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gibot S, Massin F, Cravoisy A, Barraud D, Nace L, Levy B, Bollaert PE. High-mobility group box 1 protein plasma concentrations during septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(8):1347–1353. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sunden-Cullberg J, Norrby-Teglund A, Rouhiainen A, Rauvala H, Herman G, Tracey KJ, Lee ML, Andersson J, Tokics L, Treutiger CJ. Persistent elevation of high mobility group box–1 protein (HMGB1) in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(3):564–573. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000155991.88802.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy RM, Mollen KP, Prince JM, Kaczorowski DJ, Vallabhaneni R, Liu S, Tracey KJ, Lotze MT, Hackam DJ, Fink MP, et al. Systemic inflammation and remote organ injury following trauma require HMGB1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293(4):R1538–R1544. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00272.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsung A, Sahai R, Tanaka H, Nakao A, Fink MP, Lotze MT, Yang H, Li J, Tracey KJ, Geller DA, et al. The nuclear factor HMGB1 mediates hepatic injury after murine liver ischemia-reperfusion. J Exp Med. 2005;201(7):1135–1143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada S, Inoue K, Yakabe K, Imaizumi H, Maruyama I. High mobility group protein 1 (HMGB1) quantified by ELISA with a monoclonal antibody that does not cross-react with HMGB2. Clin Chem. 2003;49(9):1535–1537. doi: 10.1373/49.9.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamada S, Yakabe K, Ishii J, Imaizumi H, Maruyama I. New high mobility group box 1 assay system. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;372(1–2):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Association of Blood Banks. Technical Manual. 14. Bethesda, MD: American Association of Blood Banks; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malone DL, Dunne J, Tracy JK, Putnam AT, Scalea TM, Napolitano LM. Blood transfusion, independent of shock severity, is associated with worse outcome in trauma. J Trauma. 2003;54(5):898–905. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000060261.10597.5C. discussion 905–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore FA, Moore EE, Sauaia A. Blood transfusion. An independent risk factor for postinjury multiple organ failure. Arch Surg. 1997;132(6):620–624. discussion 624–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE, Haenel JB, Read RA, Lezotte DC. Early predictors of postinjury multiple organ failure. Arch Surg. 1994;129(1):39–45. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420250051006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mostafa G, Gunter OL, Norton HJ, McElhiney BM, Bailey DF, Jacobs DG. Age, blood transfusion, and survival after trauma. Am Surg. 2004;70(4):357–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abraham E, Arcaroli J, Carmody A, Wang H, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a mediator of acute lung inflammation. J Immunol. 2000;165(6):2950–2954. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersson U, Erlandsson-Harris H, Yang H, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 as a DNA-binding cytokine. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72(6):1084–1091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. Targeting high mobility group box 1 as a late-acting mediator of inflammation. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(1 suppl):S46–S50. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200301001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang H, Wang H, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. HMGB1 as a cytokine and therapeutic target. J Endotoxin Res. 2002;8(6):469–472. doi: 10.1179/096805102125001091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang H, Ochani M, Li J, Qiang X, Tanovic M, Harris HE, Susarla SM, Ulloa L, Wang H, DiRaimo R, et al. Reversing established sepsis with antagonists of endogenous high-mobility group box 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(1):296–301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434651100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE, Moser KS, Brennan R, Read RA, Pons PT. Epidemiology of trauma deaths: a reassessment. J Trauma. 1995;38(2):185–193. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199502000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2004. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;56(5):1–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]