Abstract

Background: Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses is a rare, high grade malignant soft tissue tumor resembling melanoma and soft tissue sarcomas.

Clinical and Imaging Presentation: The median age at presentation is 27 years and the most common location are the foot and the ankle. MR imaging typically shows a benign looking, well defined, homogenous mass; on T1-weighted MR images, it is usually homogeneous and isointense or slight hyperintense to muscle, whereas on T2-weighted MR images, it is usually more heterogeneous with variable signal intensity.

Pathology: Microscopically, the clear cell appearance is due to the accumulation of glycogen. The cells show no or minimal pleomorphism, and paucity of mitotic figures that is in concordance with the slow-growing behavior of the tumor. Scattered multinucleated giant cells are commonly present; areas of necrosis and melanin pigment may be identified. The reciprocal translocation t(12;22)(q13;q12) is observed in more than 90% of clear cell sarcoma cases. In addition, polysomy of chromosome 8 has been observed as a secondary abnormality in many cases of clear cell sarcoma. The differential diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma should include melanoma, epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, melanotic schwannoma, paraganglioma-like dermal melanocytic tumor, perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms (PEComas), cellular blue naevus, synovial sarcoma (monophasic type), alveolar soft part sarcoma, paraganglioma, epithelioid sarcoma and carcinomas. Treatment and Prognosis: The treatment of choice for clear cell sarcoma is wide surgical resection. If complete excision is achieved, adjuvant treatments are not unnecessary. Chemotherapy is predominantly employed in patients with metastatic disease. The 5 to 20 year survival of the patients with clear cell sarcoma range from 67% to 10%. The rates of local recurrence ranges up to 84%, late metastases up to 63%, and metastases at presentation up to 30%.

Keywords: Clear cell sarcoma, Melanoma of soft parts, Soft tissue sarcoma

Introduction

Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses was first described in 1965, as a rare malignant tumor originating from tendons and aponeurosis, with histological clear cell appearance due to the accumulation of glycogen1. In 1973, melanocytic differentiation was recognized by the presence of cytoplasmic melanosomes2. In 1983, the name “malignant melanoma of soft parts” was proposed due to its histological similarities to malignant melanoma3-10.

Currently, clear cell sarcoma is a well documented, distinct clinicopathological entity, resembling melanoma and soft tissue sarcomas. Like melanoma, clear cell sarcoma shows melanocytic differentiation in almost all instances as a result of the translocation t(12;22)(q13;q12), a genetic event not seen in melanoma. Like soft tissue sarcomas, it shows deep soft tissue primary location, lacks cutaneous invasion, and has preference for lymph node and pulmonary metastasis11-15.

Clinical and Imaging Presentation

Clear cell sarcoma accounts for less than 1% of all soft tissue tumors1-4,16-25. The tumor is typically a relatively small (<5 cm), deep soft tissue lesion, often juxtaposed to tendons, fascia, or aponeuroses1,3,17,18,26. It is more prevalent in Caucasians than in African Americans or Asians, without any gender predilection17,21,26. Patients’ age at its presentation ranges from 7 to 83 years (median 27 years), with 2% occurring in children younger than 10 years3,14. The most common location are the foot and the ankle; other sites in the skeleton as well as location at the penis, retroperitoneum, kidney and gastrointestinal tract have also been reported14,24,27-33. Clear cell sarcoma of bone can be primary and metastatic (Figure 1)34-37. The distinction between clear cell sarcoma and melanoma, especially in metastatic presentation of an unknown primary tumor, often creates diagnostic challenge25.

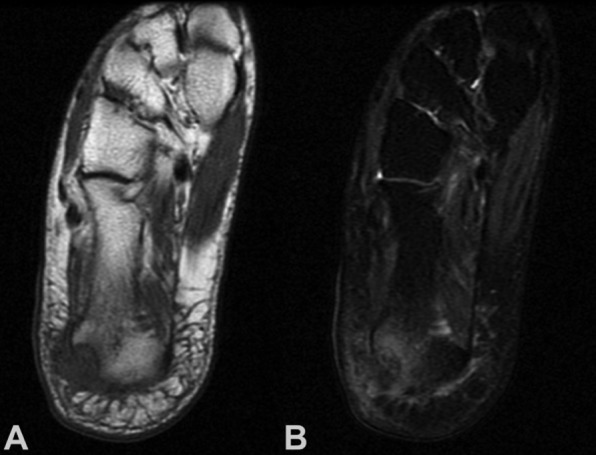

Figure 1. A 40-year-old woman with pain at the right calcaneus. Coronal (A) T1-weighted MR image showing a isointense to muscle lesion. involving the calcaneus with soft tissue mass; (B) T2-weighted MR imaging showing heterogeneity of the lesion with foci of hypointensity. Biopsy showed clear cell sarcoma. Wide resection with partial calcanectomy and local flap wound coverage was done, without evidence of local recurrence or distant metastases 3 years after diagnosis and treatment.

Radiographs are usually reported as normal as intratumoral calcifications are rare26,38,39. Computed tomography (CT) (Figure 2) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging typically show a benign looking, well defined, homogenous mass38-40. On T1-weighted MR images, it is usually homogeneous and isointense or slight hyperintense to muscle, whereas on T2-weighted MR images, it is usually more heterogeneous with variable signal intensity41. Foci of hypointensity may be present, corresponding to melanin and iron38,41.

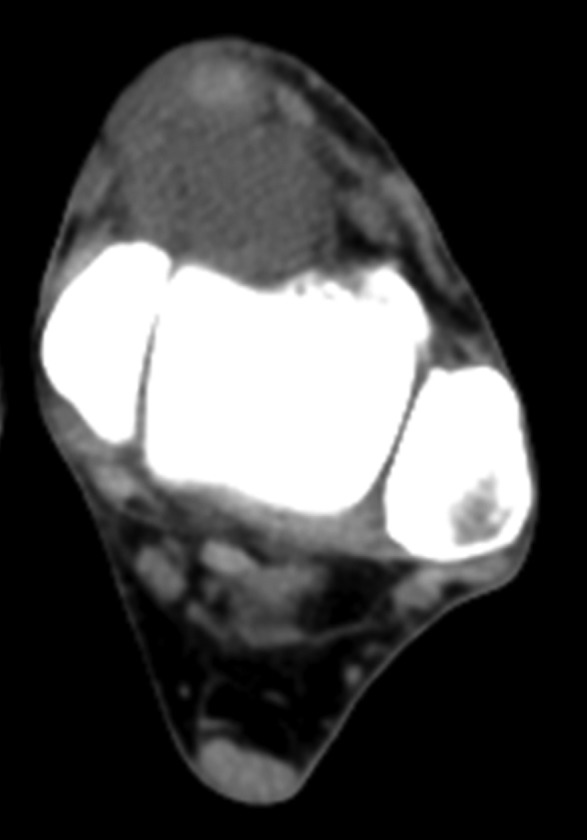

Figure 2. A 73-year-old man with pain and a palpable mass at the left distal tibia. Axial CT scan shows a homogenous, isointense to muscle lesion. Biopsy showed clear cell sarcoma. Marginal resection, brachytherapy (20 Gy) and external beam radiation therapy (34 Gy) was performed without evidence of local recurrence or distant metastases 2 years after diagnosis and treatment.

Pathology

Macroscopically, clear cell sarcoma is a tan-grey, firm, circumscribed mass10. Microscopically, the tumor is highly infiltrative and haphazardly organized into small compact nests and fascicles of neoplastic cells dissecting along the dense fibrous connective tissue of tendons, fascia, and aponeuroses. Biphasic differentiation is absent1,4,42. The cellular nests are divided into lobules by a fine fibrocollagenous framework of variable thickness that is contiguous with the fibrous connective tissue of the adjacent tendons and aponeurosis1,3,15. The neoplastic cells are polygonal to fusiform, with clear or pale, eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm and have centrally located uniform, round to ovoid vesicular nuclei with prominent basophilic nucleoli, similar to melanoma. The clear cell appearance is due to the accumulation of glycogen. The cells show no or minimal pleomorphism, and paucity of mitotic figures that is in concordance with the slow-growing behavior of the tumor. Scattered multinucleated giant cells are commonly present; areas of necrosis and melanin pigment may be identified1,3,10,15,18,25,42-45

Immunohistochemically, clear cell sarcoma shows a phenotype identical to that of conventional melanoma characterized by strong S100 protein expression in 100% of cases, and expression of HMB-45, Melan-A and MiTF in 97% to 81% of cases25. It may also expresses neuroendocrine and/or nerve sheath-related markers, including synaptophysin, CD56 and CD57 in 21% to 75% of cases; CD34 is generally negative25. Rarely, clear cell sarcoma may show anomalous expression of epithelial markers, including cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen.

Cytogenetics

The reciprocal translocation t(12;22)(q13;q12) is observed in more than 90% of clear cell sarcoma cases, with chromosome analysis, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)11. This translocation results in fusion of a portion of the Activating Transcription Factor gene (ATF-1) on the long arm of chromosome 12 (12q13) and the Ewing’s sarcoma oncogene R1 (EWSR1) on chromosome 22 (22q12)11,13,22,25,30,33,46-49. Four types of EWSR1/ATF1 fusion have been identified49, and one type of EWSR1/CREB1 fusion, presumably representing the translocation t(2;22)(q32.3;q12)8,25,49. Recently, it has been shown that the EWSR1/ATF1 fusion protein is capable of binding to and activating the melanocyte-specific microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MiTF), which in the presence of the sox10 transcription factor, results in expression of the melanocytic phenotype and regulates the growth/survival of clear cell sarcoma cells50.

In addition to the diagnostic t(12;22)(q13;q12) translocation, polysomy of chromosome 8 has been observed as a secondary abnormality, in many cases of clear cell sarcoma46,51,52.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma should include melanoma, epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, melanotic schwannoma, paraganglioma-like dermal melanocytic tumor, perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms (PEComas), cellular blue naevus, synovial sarcoma (monophasic type), alveolar soft part sarcoma, paraganglioma, epithelioid sarcoma and carcinomas15.

Compared to melanoma, clear cell sarcoma occurs in much younger patients, is deeply located, associated with tendons or aponeuroses, lacks epidermal involvement, tends to display less cellular pleomorphism, and may contain Touton-type neoplastic giant cells; these features are unusual for melanoma. In contrast, a primary cutaneous nodular melanoma is usually a dermal-based tumor that tends to be more pleomorphic and mitotically active, than clear cell sarcoma. Molecular genetic studies, for the EWS/ATF1 or EWS/CREB1 fusions, are required for definitive diagnosis8,11-13.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor is usually associated with a large peripheral nerve or neurofibromatosis, and is characterized by significant myxoid stroma, hyperchromatic nuclei, brisk mitotic activity, and negativity for HMB-45, melanocytic markers and cytogenetic abnormalities10. Melanotic schwannoma most often occurs in patients with Carney syndrome, in paraspinal or nerve plexus-related location, and frequently contains psammomatous calcifications and very abundant melanin pigment15. In contrast to clear cell sarcoma, paraganglioma-like dermal melanocytic tumor is primarily a tumor of the extremities of females, presents as a dermal nodule, and it has distinct histological appearance and absence of EWSgene cytogenetic abnormalities53.

Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms commonly arise within the abdomen of young patients with predilection for the falciform ligament and ligamentum teres of the liver, and are characterized by fascicular and nested proliferation of uniform spindle cells, less prominent nucleoli and lack of multinucleation, and expression of smooth muscle actins and melanocytic markers in immunohistochemical studies10,54. Cellular blue naevi lack cytological atypia, frequently grow in a dumbbell-shaped configuration and are negative for the EWS-ATF1 gene fusion15. Synovial and epithelioid sarcomas, and carcinomas lack the distinctive nested growth pattern of clear cell sarcoma, and express cytokeratins, but not S100 protein10,15.

Treatment

The treatment of choice for clear cell sarcoma is wide surgical resection14,21,24,55-57. If complete excision is achieved, adjuvant treatments are not necessary57.Amputation is not justified, unless there is vascular or neural impairment ofthe limb, as the survival is similar to that of wide resection19,56.Intralesional or marginal excision is associated with high local recurrencerates (Figure 3)21. In case of close resection margins, postoperative radiation therapy is indicated to improve local tumor control26,55,56.

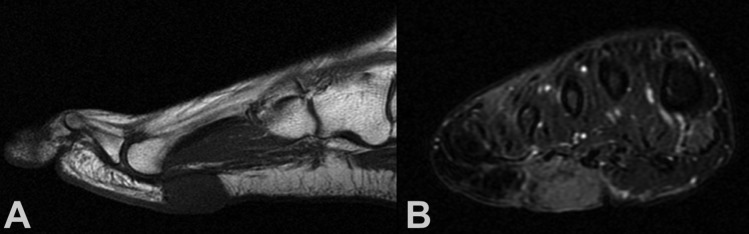

Figure 3. A 47-year-old woman with pain and a palpable mass at the plantar aspect of the right forefoot. She had marginal resection for clear cell sarcoma at this location 9 years before. (A) Sagittal T1-weighted MR image showing a isointense to muscle lesion. (B) Coronal T2-weighted MR image showing a relative hyperintense to muscle lesion. Biopsy showed recurrent clear cell sarcoma. Wide resection and local flap wound coverage was performed without evidence of local re-recurrence 2 years after diagnosis and treatment of the recurrent tumor.

Chemotherapy is predominantly employed in patients with metastatic disease14,17,21,24,55,57,58. Doxorubicin-based chemotherapy has not been effective21,26,57. In contrast, cisplatin-based chemotherapy and caffeine-assisted chemotherapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin, may elicit a tumor response, especially in patients with metastatic disease, or tumors more than 5 cm in maximum diameter24,59. Complete local response after isolated limb perfusion60, and intralesional injection of interferon alpha 2B has also been reported58.

Ten to 14% of patients with clear cell sarcoma will develop regional lymph node metastasis; the majority of these patients will develop distant metastasis, most often to lung and bone1,3,14,18-21,24-26. Although lung metastasectomy is not recommended due to the aggressive clinical course of the metastatic disease, the role of therapeutic lymphadenectomy for locoregional disease control is unclear3,14,55,57,61. Most authors suggest regional lymphadenectomy, only in case of clinically and fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytologically confirmed regional lymph node involvement55,57,61. Early detection of occult regional lymphatic metastases by lymphatic mapping using lymphoscintigraphy and blue dye, and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) may improve staging of the regional disease, and guide the extent of surgery and decision for adjuvant treatments62.

Prognosis

The rates of 5-year, 10-year and 20-year-survival of the patients with clear cell sarcoma, range from 67% to 10%1,3,14,18-21,24-26. The rates of local recurrence range up to 84%, late metastases up to 63%, and metastases at presentation up to 30% of patients1,3,4,18-21,24,25. Metastases may occur early, or as late as 29 years after diagnosis and surgical treatment3,14,21,26.

Prognostic factors in patients with clear cell sarcoma are tumor size, site, necrosis, mitoses, DNA content, and resection margins18,19,21,26,57. Tumors <5 cm are much less likely to recur or metastasize, whereas those >5 cm are more commonly associated with metastatic disease18-22,24-26. Probably, patients with tumors >5 cm have micrometastases at diagnosis24. Focal or diffuse tumor necrosis also correlates with a worse prognosis, independent of tumor size19. Lymph node metastasis is also associated with a poor prognosis, since patients with regional metastasis eventually will develop distant metastasis1,18,19,26.

Conclusion

Clear cell sarcoma is a rare highly malignant soft tissue tumor, which resembles melanoma and soft tissue sarcomas. Wide resection is the treatment of choice. Adjuvant radiation is required if resection is close to resection margins; the role of chemotherapy is unclear. Long-term follow-up is necessary because of late local recurrences and regional lymph node or distant metastases.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Enzinger FM. Clear-cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. An analysis of 21 cases. Cancer. 1965;18:1163–1174. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196509)18:9<1163::aid-cncr2820180916>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman GJ, Carter D. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses with melanin. Arch Pathol. 1973;95:22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung EB, Enzinger FM. Malignant melanoma of soft parts. A reassessment of clear cell sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:405–413. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kindblom LG, Lodding P, Angervall L. Clear-cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. An immunohistochemical and electron microscopic analysis indicating neural crest origin. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1983;401:109–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00644794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson PE, Wick MR. Clear cell sarcoma. An immunohistochemical analysis of six cases and comparison with other epithelioid neoplasms of soft tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1989;113:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang KL, Folpe AL. Diagnostic utility of microphthalmia transcription factor in malignant melanoma and other tumors. Adv Anat Pathol. 2001;8:273–275. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granter SR, Weilbaecher KN, Quigley C, Fletcher CD, Fisher DE. Clear cell sarcoma shows immunoreactivity for microphthalmia transcription factor: further evidence for melanocytic differentiation. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:6–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonescu CR, Tschernyavsky SJ, Woodruff JM, Jungbluth AA, Brennan MF, Ladanyi M. Molecular diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma: detection of EWS-ATF1 and MITF-M transcripts and histopathological and ultrastructural analysis of 12 cases. J Mol Diagn. 2002;4:44–52. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60679-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moritake H, Sugimoto T, Asada Y, Yoshida MA, Maehara Y, Epstein AL, et al. Newly established clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma of soft parts) cell line expressing melanoma-associated Melan-A antigen and overexpressing C-MYC oncogene. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2002;135:48–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(01)00641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dim DC, Cooley LD, Miranda RN. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:152–156. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-152-CCSOTA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langezaal SM, Graadt van Roggen JF, Cleton-Jansen AM, Baelde JJ, Hogendoorn PC. Malignant melanoma is genetically distinct from clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeurosis (malignant melanoma of soft parts) Br J Cancer. 2001;84:535–538. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segal NH, Pavlidis P, Noble WS, Antonescu CR, Viale A, Wesley UV, et al. Classification of clear-cell sarcoma as a subtype of melanoma by genomic profiling. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1775–1781. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panagopoulos I, Mertens F, Isaksson M, Mandahl N. Absence of mutations of the BRAF gene in malignant melanoma of soft parts (clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses) Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;156:74–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark MA, Johnson MB, Thway K, Fisher C, Thomas JM, Hayes AJ. Clear cell sarcoma (melanoma of soft parts): The Royal Marsden Hospital experience. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:800–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kosemehmetoglu K, Folpe AL. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses, and osteoclast-rich tumour of the gastrointestinal tract with features resembling clear cell sarcoma of soft parts: a review and update. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:416–423. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.057471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss SW. Enzinger and Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. 5th edn. Mosby/Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malchau SS, Hayden J, Hornicek F, Mankin HJ. Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:519–522. doi: 10.1002/jso.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sara AS, Evans HL, Benjamin RS. Malignant melanoma of soft parts (clear cell sarcoma). A study of 17 cases, with emphasis on prognostic factors. Cancer. 1990;65:367–374. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900115)65:2<367::aid-cncr2820650232>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucas DR, Nascimento AG, Sim FH. Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissues. Mayo Clinic experience with 35 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:1197–1204. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marquès B, Terrier P, Voigt JJ, Mihura J, Coindre JM. [Clear cell soft tissue sarcoma. Clinical, histopathological and prognostic study of 36 cases] Ann Pathol. 2000;20:298–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finley JW, Hanypsiak B, McGrath B, Kraybill W, Gibbs JF. Clear cell sarcoma: the Roswell Park experience. J Surg Oncol. 2001;77:16–20. doi: 10.1002/jso.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coindre JM, Hostein I, Terrier P, Bouvier-Labit C, Collin F, Michels JJ, et al. Diagnosis of clear cell sarcoma by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis of paraffin embedded tissues: clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 44 patients from the French sarcoma group. Cancer. 2006;107:1055–1064. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meis-Kindblom JM. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: a historical perspective and tribute to the man behind the entity. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:286–292. doi: 10.1097/01.pap.0000213052.92435.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawai A, Hosono A, Nakayama R, Matsumine A, Matsumoto S, Ueda T, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: a study of 75 patients. Cancer. 2007;109:109–116. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hisaoka M, Ishida T, Kuo TT, Matsuyama A, Imamura T, Nishida K, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 33 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:452–460. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31814b18fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deenik W, Mooi WJ, Rutgers EJ, Peterse JL, Hart AA, Kroon BB. Clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma) of soft parts: A clinicopathologic study of 30 cases. Cancer. 1999;86:969–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saw D, Tse CH, Chan J, Watt CY, Ng CS, Poon YF. Clear cell sarcoma of the penis. Hum Pathol. 1986;17:423–425. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(86)80468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poignonec S, Lamas G, Homsi T, Auriol M, De Saint Maur PP, Castro DJ, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of the pre-parotid region: an initial case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 1994;48:369–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gelczer RK, Wenger DE, Wold LE. Primary clear cell sarcoma of bone: a unique site of origin. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:240–243. doi: 10.1007/s002560050509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin BP, Fletcher JA, Renshaw AA. Clear cell sarcoma of soft parts: report of a case primary in the kidney with cytogenetic confirmation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:589–594. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199905000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katabuchi H, Honda R, Tajima T, Ohtake H, Kageshita T, Ono T, et al. Clear cell sarcoma arising in the retroperitoneum. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:124–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suehara Y, Yazawa Y, Hitachi K, Terakado A. Clear cell sarcoma arising from the chest wall: a case report. J Orthop Sci. 2004;9:171–174. doi: 10.1007/s00776-003-0751-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Covinsky M, Gong S, Rajaram V, Perry A, Pfeifer J. EWS-ATF1 fusion transcripts in gastrointestinal tumors previously diagnosed as malignant melanoma. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reichert B, Hoch J, Plötz W, Mailänder P, Moubayed P. Metastatic clear-cell sarcoma of the capitate. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1713–1717. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200111000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi JH, Gu MJ, Kim MJ, Bae YK, Choi WH, Shin DS, et al. Primary clear cell sarcoma of bone. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:598–602. doi: 10.1007/s00256-003-0683-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hersekli MA, Ozkoc G, Bircan S, Akpinar S, Ozalay M, Tuncer I, et al. Primary clear cell sarcoma of rib. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:167–170. doi: 10.1007/s00256-004-0801-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W, Shen Y, Wan R, Zhu Y. Primary clear cell sarcoma of the sacrum: a case report. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40:633–639. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-1077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isoda H, Kuroda M, Saitoh M, Asakura T, Akai M, Ikeda K, et al. MR findings of clear cell sarcoma: two case reports. Clin Imaging. 2003;27:229–232. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(02)00493-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Nakshabandi NA, Munk PL. Radiology for the surgeon. Musculoskeletal case 38. Diagnosis: clear cell sarcoma of the foot. Can J Surg. 2007;50:58–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Beuckeleer LH, De Schepper AM, Vandevenne JE, Bloem JL, Davies AM, Oudkerk M, et al. MR imaging of clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma of the soft parts): a multicenter correlative MRI-pathology study of 21 cases and literature review. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29:187–195. doi: 10.1007/s002560050592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wetzel LH, Levine E. Soft-tissue tumors of the foot: value of MR imaging for specific diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:1025–1030. doi: 10.2214/ajr.155.5.2120930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pavlidis NA, Fisher C, Wiltshaw E. Clear-cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: a clinicopathologic study. Presentation of six additional cases with review of the literature. Cancer. 1984;54:1412–1417. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841001)54:7<1412::aid-cncr2820540730>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim YC, Vandersteen DP, Jung HG. Myxoid clear cell sarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:51–55. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000141547.31306.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rau AR, Kini H, Verghese R. Tigroid background in fine-needle aspiration cytology of clear cell sarcoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:355–357. doi: 10.1002/dc.20368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eluri S, Ali SZ. Clear cell sarcoma: cytopathologic finding of a “tigroid” background. Diagn Cytopathol. 2010;38:581–582. doi: 10.1002/dc.21239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bridge JA, Sreekantaiah C, Neff JR, Sandberg AA. Cytogenetic findings in clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. Malignant melanoma of soft parts. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1991;52:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(91)90059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zucman J, Delattre O, Desmaze C, Epstein AL, Stenman G, Speleman F, et al. EWS and ATF-1 gene fusion induced by t(12;22) translocation in malignant melanoma of soft parts. Nat Genet. 1993;4:341–345. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hallor KH, Mertens F, Jin Y, Meis-Kindblom JM, Kindblom LG, Behrendtz M, et al. Fusion of the EWSR1 and ATF1 genes without expression of the MITF-M transcript in angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;44:97–102. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang WL, Mayordomo E, Zhang W, Hernandez VS, Tuvin D, Garcia L, et al. Detection and characterization of EWSR1/ATF1 and EWSR1/CREB1 chimeric transcripts in clear cell sarcoma (melanoma of soft parts) Mod Pathol. 2009;22:1201–1209. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis IJ, Kim JJ, Ozsolak F, Widlund HR, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Granter SR, et al. Oncogenic MITF dysregulation in clear cell sarcoma: defining the MiT family of human cancers. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hicks MJ, Saldivar VA, Chintagumpala MM, Horowitz ME, Cooley LD, Barrish JP, et al. Malignant melanoma of soft parts involving the head and neck region: review of literature and case report. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1995;19:395–400. doi: 10.3109/01913129509021912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henkle CT, Hawkins AL, McCarthy EF, Griffin CA. Clear cell sarcoma case report: complex karyotype including t(12;22) in primary and metastatic tumor. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;149:63–67. doi: 10.1016/S0165-4608(03)00295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deyrup AT, Althof P, Zhou M, Morgan M, Solomon AR, Bridge JA, et al. Paraganglioma-like dermal melanocytic tumor: a unique entity distinct from cellular blue nevus, clear cell sarcoma, and cutaneous melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1579–1586. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200412000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Folpe AL, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, Paulino AF, Taboada EM, Meehan SA, et al. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres: a novel member of the perivascular epithelioid clear cell family of tumors with a predilection for children and young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1239–1246. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuiper DR, Hoekstra HJ, Veth RP, Wobbes T. The management of clear cell sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:568–570. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(03)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mankin HJ, Hornicek FJ. Diagnosis, classification, and management of soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Control. 2005;12:5–21. doi: 10.1177/107327480501200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferrari A, Casanova M, Bisogno G, Mattke A, Meazza C, Gandola L, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses in pediatric patients: a report from the Italian and German Soft Tissue Sarcoma Cooperative Group. Cancer. 2002;94:3269–3276. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steger GG, Wrba F, Mader R, Schlappack O, Dittrich C, Rainer H. Complete remission of metastasised clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:254–256. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90509-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsuchiya H, Tomita K, Yamamoto N, Mori Y, Asada N. Caffeine-potentiated chemotherapy and conservative surgery for high-grade soft-tissue sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:3651–3656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olieman AF, Pras E, van Ginkel RJ, Molenaar WM, Schraffordt Koops H, Hoekstra HJ. Feasibility and efficacy of external beam radiotherapy after hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion with TNF-alpha and melphalan for limb-saving treatment in locally advanced extremity soft-tissue sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;40:807–814. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00923-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tong TR, Chow TC, Chan OW, Lee KC, Yeung SH, Lam A, et al. Clear-cell sarcoma diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration: cytologic, histologic, and ultrastructural features; potential pitfalls; and literature review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:174–180. doi: 10.1002/dc.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Akkooi AC, Verhoef C, van Geel AN, Kliffen M, Eggermont AM, de Wilt JH. Sentinel node biopsy for clear cell sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:996–999. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]