Abstract

Vibrio cholerae, an etiological agent of cholera, circulates between aquatic reservoirs and the human gastrointestinal tract. The type II secretion (T2S) system plays a pivotal role in both stages of the lifestyle by exporting multiple proteins, including cholera toxin. Here, we studied the kinetics of expression of genes encoding the T2S system and its cargo proteins. We have found that under laboratory growth conditions, the T2S complex was continuously expressed throughout V. cholerae growth, whereas there was growth phase-dependent transcriptional activity of genes encoding different cargo proteins. Moreover, exposure of V. cholerae to different environmental cues encountered by the bacterium in its life cycle induced transcriptional expression of T2S. Subsequent screening of a V. cholerae genomic library suggested that σE stress response, phosphate metabolism, and the second messenger 3′,5′-cyclic diguanylic acid (c-di-GMP) are involved in regulating transcriptional expression of T2S. Focusing on σE, we discovered that the upstream region of the T2S operon possesses both the consensus σE and σ70 signatures, and deletion of the σE binding sequence prevented transcriptional activation of T2S by RpoE. Ectopic overexpression of σE stimulated transcription of T2S in wild-type and isogenic ΔrpoE strains of V. cholerae, providing additional support for the idea that the T2S complex belongs to the σE regulon. Together, our results suggest that the T2S pathway is characterized by the growth phase-dependent expression of genes encoding cargo proteins and requires a multifactorial regulatory network to ensure appropriate kinetics of the secretory traffic and the fitness of V. cholerae in different ecological niches.

INTRODUCTION

The type II secretion (T2S) system is a sophisticated machine utilized by many Gram-negative bacteria to transport proteins that contribute to their virulence and/or survival in environmental habitats (1–4). Depending on the bacterial species, the T2S complex consists of 12 to 15 different proteins that, via multiple protein-protein interactions, assemble a secretion apparatus that bridges the cytoplasmic membrane with the outer membrane (5). This secretory pathway is responsible for the passage of folded and/or oligomeric cargo proteins (exoproteins and T2S substrates) from the periplasm across the outer membrane. After translocation, the T2S substrates are either released to the extracellular milieu or remain anchored to the bacterial cell surface (6). The array of T2S exoproteins is comprised of toxins, enzymes capable of breaking down a variety of biological materials, and lipoproteins participating in respiration and/or biofilm formation, as well as proteins facilitating bacterial attachment to biotic and abiotic surfaces (2–4, 6).

The organization and functions of the individual constituents of the T2S complex have been studied in several model organisms, including Vibrio cholerae, the etiological agent of the epidemic diarrheal disease cholera. In V. cholerae, the components of the T2S system are encoded by two divergent operons, epsCDEFGHIJKLMN and epsAB (where eps stands for extracellular protein secretion), as well as the vcpD (pilD) gene (7). The model of the T2S machine includes an outer membrane protein, the secretin EpsD; inner membrane platform proteins (EpsC, -F, -L, and -M); a major pseudopilin, EpsG; the minor pseudopilins EpsH through EpsK; a cytoplasmic T2S ATPase, EpsE; and a prepilin peptidase, PilD, which is shared with the type IV secretion system (5). The secretion of the V. cholerae principal virulence factor, cholera toxin, is dependent upon a functional T2S system (8). Cholera toxin is produced and secreted by toxigenic strains of V. cholerae after successful colonization of the human small intestine and is largely responsible for the voluminous diarrhea, the hallmark symptom of cholera (9). The genes encoding cholera toxin, ctxAB, are not an integral component of the V. cholerae genome but are carried by the lysogenic filamentous bacteriophage CTXphi, which specifically infects V. cholerae (10). Hence, the environmental nonpathogenic strains of V. cholerae can be converted into toxigenic strains (11). Intriguingly, the exit of CTXphi from its host depends upon functional EpsD, making the T2S system an important contributor to the horizontal transfer of the key virulence gene (12, 13). The importance of T2S in the life cycle of V. cholerae extends beyond the transport of cholera toxin and release of CTXphi, because at least 20 cargo proteins are translocated to the extracellular milieu via this secretory pathway (2, 14). The functions of only a small subset of these additional T2S exoproteins have been addressed, including sialidase (neuraminidase), hemagglutinin protease (HapA), chitinases, and a chitin-binding protein (GbpA). These proteins contribute to disease pathogenesis and/or to the persistence of V. cholerae in natural aquatic habitats during interepidemic periods (2).

Cholera remains one of the top global infectious disease threats (15), and therefore, understanding the basic mechanisms of V. cholerae virulence and environmental survival is a prerequisite for the development of new therapeutic treatments or preventive measures. Previous studies demonstrated that genetic manipulations leading to removal of either the entire epsC-epsN (epsC-N) operon or inactivation of the individual eps genes or pilD led to dramatic consequences for V. cholerae pathophysiology (16–18). In addition to loss of cargo protein secretion and virulence, the T2S mutants displayed growth defects, perturbed cell envelope integrity, altered iron homeostasis, and induction of the extracytoplasmic RpoE stress response. These pleiotropic effects further underscore the vital role of T2S in V. cholerae biology, suggesting the T2S pathway as a molecular target for therapeutic and preventive interventions against cholera. While many studies have focused on understanding the architecture and functions of the T2S components, significantly less is known about the regulation of biogenesis of the T2S complex, the recognition of exoproteins, and the secretory traffic. Until they have been defined, opportunities to target T2S therapeutically are likely to remain limited. Thus, in this study, we began to characterize the transcriptional regulation of T2S and the patterns of cargo gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. V. cholerae strains were derived from either El Tor (N16961 and C6706) or the classical O395 biotype. Bacteria were streaked from −80°C on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Antibiotics were used in the solid and liquid media in the following concentrations: chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml or 4 μg/ml for Escherichia coli or V. cholerae, respectively), carbenicillin (50 μg/ml), and kanamycin (50 μg/ml). All E. coli strains were cultured in LB medium at 37°C. V. cholerae was propagated in LB medium at 37°C or 25°C, as well as the conditions used for either maximal induction or repression of virulence gene expression (19) as specified in the text. All media utilized in this study were purchased from Difco.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Description/relevant genotypea | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae strains | ||

| O395 | Wild-type classical O1 biotype; Smr | Laboratory collection |

| O395ΔrpoE | O395 ΔrpoE Smr | 37 |

| N16961 | Wild-type El Tor O1 biotype; Smr | Laboratory collection |

| C6706 | Wild-type El Tor O1 biotype; Smr | Laboratory collection |

| C6706ΔhapR | C6706 ΔhapR Kanr | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| MC1061 | F− araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 Δ(lac)X74 rpsL hsdR2 mcrA mcrB1 | 49 |

| MM294(pRK2013) | Donor of transfer function for triparental conjugation | 50 |

| NEB5α | fhuA2 Δ(argF-lacZ)U169 phoA glnV44 Φ80 Δ(lacZ)M15 gyrA96 recA1 relA1 endA1 thi-1 hsdR17 | NEB |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMMB67-EH | Expression vector; Ptac promoter; Ampr | 51 |

| pBBRlux | ori pBBR1; promoterless luxCDABE; Cmr | 20 |

| pACYC177 | ori p15A Ampr Kanr | 52 |

| pAES106 | rpoEP2 cloned into pBBRlux; Cmr | 17 |

| pKD4 | ori R6Kγ; Ampr FRT Kanr FRT | 22 |

| pNEB193 | Cloning vector pUC19 derivative | NEB |

| pPCR-Script Amp SK(+) | Cloning vector; Ampr | Stratagene |

| pCVD442 | ori R6k mob RP4 sacB Ampr | 23 |

| peps-lux | epsP1-P2 cloned into pBBRlux; Cmr | This study |

| peps70-lux | epsP1 cloned into pBBRlux; Cmr | This study |

| pvesA-lux | vesAP cloned into pBBRlux; Cmr | This study |

| pvesB-lux | vesBP cloned into pBBRlux; Cmr | This study |

| pvesC-lux | vesCP cloned into pBBRlux; Cmr | This study |

| ptarp-lux | tarpP cloned into pBBRlux; Cmr | This study |

| pRpoE | pMMB67-EH carrying Ptac-rpoEN16961 | This study |

| pHapR | pMMB67-EH carrying Ptac-hapRC6706 | This study |

| pNEBΔhapR | pNEB193 carrying 2,636-bp DNA fragment containing Kanr cassette flanked by 553 bp upstream and downstream of hapR | This study |

| pCVDΔhapR | pCVD442 containing upstream region of hapR, Kanr, and downstream of hapR | This study |

Smr, streptomycin resistant; Ampr, ampicillin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant.

DNA manipulations.

To construct transcriptional fusion reporters, DNA fragments of 173, 440, 446, 440, and 499 bp containing promoter regions of the epsC-N operon, vesA, vesB, vesC, and VCA0148 encoding a TagA-related protein (Tarp), respectively, were amplified using the primers listed in Table 2. The truncated version of the eps promoter (eps70-lux), which lacked the σE signature sequence, was constructed by utilization of the primer pair eps70-F and eps70-R (Table 2). The V. cholerae N16961 genome sequence was used as a template to design primers, and a purified chromosomal DNA (Promega Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit) from either V. cholerae N16961 or C6706, as indicated in the text, was used in PCRs. All reactions were performed using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England BioLabs), with oligonucleotides synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. The PCR products obtained were first cloned into the pPCR-Script Amp SK(+) cloning vector (Stratagene). Subsequently, the individual DNA fragments containing promoters of the respective genes were inserted into SpeI-BamHI-digested pBBR-lux in front of a promoterless luxCDABE reporter (20).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers designed and used in this study

| Purpose | Name | Sequence (5′ to 3′)a |

|---|---|---|

| Promoter fusion construction | eps-F | GGATCCCATCGCAATATAACACAAGC |

| eps-R | ACTAGTCAGTCTCACCTCTTCTGCGC | |

| eps70-F | GATATCACTAGTAAGCTTATTACATTTGACTATTATTCA | |

| eps70-R | GATATCGGATCCGGCATCGCAATATAACACAAGC | |

| vesA-F | CTCGAGACTAGTATTCGCCAGAAAGAAGTGGG | |

| vesA-R | CTCGAGGGATCCGCGTCACCTCATTGGTTGA | |

| vesB-F | CTCGAGACTAGTTGTATCTCGGCTTACTGCT | |

| vesB-R | CTCGAGGGATCCAACTCAATCCTTTCATTAATCA | |

| vesC-F | CTCGAGACTAGTAGATACCTCTGATAACTCCC | |

| vesC-R | CTCGAGGGATCCGGCTGTAAATCTTGTATCTC | |

| tarp-F | CTCGAGACTAGTAATGCCGTACAAGGTTTT | |

| tarp-R | CTCGAGGGATCCCAGCAAATAGTTACACAATAATCA | |

| Cloning wild-type alleles | rpoE-F | ATGCATCCCGGGAGGGGAATAACAATAGGAGTGA |

| rpoE-R | ATGCATTCTAGATCATTACGGAATTTGCGTTA | |

| hapR-F | ATGCATGAATTCCAACTCAATTGGCAAGGATA | |

| hapR-R | ATGCATTCTAGAGCTGCCCAAGAAACTAGTTC | |

| Creating ΔhapR knockout | pNEB193-F | CTCTAGACTTAATTAAGGATCC |

| pNEB193-R | GACTCTAGACTTAATTAAGGATCC | |

| hapR-U-F | CCTTAATTAAGTCTAGAGTCTTCCACCAGCAATACATC | |

| hapR-U-R | CAGCCTACACTTTGCTCTAATGATTATTTTGTTATTTG | |

| kan-F | TTAGAGCAAAGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCT | |

| kan-R | GCCCAAGAAAATGGGAATTAGCCATGGTCC | |

| hapR-D-F | TAATTCCCATTTTCTTGGGCAGCACAAAG | |

| hapR-D-R | GCCTGCAGGTTTAAACAGTCGTCACTGCAAGATATGTTAGATG | |

| hapR-F-Sal | CGAAGTCGACTTCCACCAGCAATACATCTTTAC | |

| hapR-R-Sca | CGAAGAGCTCGTCACTGCAAGATATGTTAGATG | |

| Sequencing genomic library | pACYC-F | CCGAAGAACGTTTTCCAATG |

| pACYC-R | GAGTACTCAACCAAGTCATTCTGA |

F, forward; R, reverse; U, upstream; D, downstream. The underlined nucleotides refer to restriction enzyme sites.

Construction of plasmids carrying either the rpoE or hapR gene placed under the control of the PTAC promoter was accomplished as follows. First, rpoE and hapR coding sequences were amplified using chromosomal DNA isolated from V. cholerae N16961 and C6706, respectively, as templates, and oligonucleotides listed in Table 2. The resulting PCR products of rpoE and hapR were cloned into the corresponding XmaI-XbaI and EcoRI-XbaI sites within a broad-host-range expression vector, pMMB67-EH (Table 2). The expression of both rpoE and hapR was induced with 100 μM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

To create an in-frame deletion of the hapR gene in V. cholerae C6706, first, the pNEBΔhapR plasmid was generated using the assembly method of Gibson et al. (21). The 500-bp regions upstream and downstream of the hapR gene were amplified by PCR using the V. cholerae C6706 genome as a template and the oligonucleotide pairs hapR-U-F/hapR-U-R and hapR-D-F/hapR-D-R, respectively (Table 2). The kanamycin resistance gene was amplified from plasmid pKD4 (22) using primers kan-F and kan-R. Plasmid pNEB193 (NEB) was linearized in a PCR using primers pNEB193-F and pNEB193-R. Subsequently, 100 ng of linearized vector was mixed with a 3-fold excess of inserts and 10 μl of Gibson Assembly Master Mix (NEB), followed by incubation at 55°C for 1 h. Chemically competent E. coli NEB5α (Table 1) cells were transformed with 5 μl of the assembled product. The construct obtained was amplified using primers hapR-F-Sal and hapR-R-Sca, digested with restriction enzymes SalI and ScaI, and cloned into a similarly cleaved suicide vector, pCVD442 (23). The resulting plasmid, pCVDΔhapR, was introduced into V. cholerae C6706 by conjugation, and in-frame deletion of the hapR gene was achieved by allelic-exchange procedures according to the methods described by Sikora et al. (17).

All the constructs obtained were sequenced at the Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing at Oregon State University. Plasmids were introduced into V. cholerae by triparental conjugation using as a donor E. coli MC1061 carrying a particular plasmid and a helper strain, MM294, as previously described (17). After conjugation, V. cholerae strains were selected by plating bacterial mixtures on thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose agar supplemented with appropriate antibiotics.

Assessment of transcriptional expression using promoter-lux reporter fusions.

To examine the kinetics of the transcriptional activity of promoter-luxCDABE (lux) fusions, bacterial strains at the stationary phase of growth (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], about 4) were diluted 1:100 in appropriate fresh culture media, as specified in the text, and delivered in technical triplicates into 96-well, white, clear-bottom microtiter plates (Greiner-BioOne). Technical triplicates of the respective culture media (controls for both OD600 and contamination) and the culture of V. cholerae carrying the pBBR-lux vector (background luminescence control) were included. The total volume in each well on the microtiter plate was 200 μl. The individual microtiter plates were incubated in a Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate reader (BioTek) with moderate shaking for 16 h. The turbidity of bacterial cultures (OD600) and the relative luminescence units (RLU) were recorded every 20 min, and the data are presented as means with calculated standard errors of the mean (SEM) obtained from experiments performed in at least biological triplicates.

The relative fold change was used to compare the expression of individual promoter-lux fusions in classical V. cholerae during growth under conditions that result in either maximal induction (LB, pH 6.5; 30°C) or repression (LB, pH 8.5; 37°C) of virulence gene expression (19). The highest activity of a respective promoter-lux fusion (maximum RLU) detected during bacterial growth under each condition was normalized by the optical density of the culture (17). Subsequently, the relative fold change was calculated by dividing the normalized promoter-lux activity under virulence gene-inducing conditions by its corresponding activity under virulence gene-inhibiting conditions. All experiments were performed independently at least four times, and means with calculated SEM are reported.

To examine the effects of various exogenous factors on transcriptional expression of either eps-lux or rpoEP2-lux, assays were performed as previously described (17, 18). Briefly, V. cholerae strains carrying particular transcriptional fusions were cultured with aeration in LB medium at 37°C until the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (OD600 = 0.5). Then, equal amounts of the cultures were divided into individual test tubes containing the examined compound, including polymyxin B sulfate (100 or 50 U per ml for N16961 or O395, respectively), the iron chelator 2-(pyridin-2-yl)pyridine (2,2′-dipyridyl at 100 μM final concentration), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (vehicle), or bile salts (0.1% final concentration). The RLU and turbidities of untreated, treated, and mock-treated bacterial cultures were examined at 30 min postexposure. The reported values of promoter-lux activities are expressed as RLU normalized by the turbidity of the culture per 1.0 ml (17). Experiments were conducted on five independent occasions, and mean values with associated SEM are reported.

The effect of overproduction of RpoE on the transcriptional activity of eps was assessed in V. cholerae strains carrying either pRpoE and peps-lux or pRpoE and peps70-lux. The control strains harbored empty pMMB67-EH vector and either peps-lux or peps70-lux (Table 1). In all experiments, overnight cultures of V. cholerae carrying appropriate plasmids, as specified in the text, were inoculated in a 1:100 ratio into fresh medium supplemented with antibiotics. The expression of rpoE was induced with 100 μM IPTG when the cultures reached the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (OD600 = 0.5). To correct for any potential effect of IPTG on transcriptional activity, the inducer was also added to control strains of V. cholerae. Both bioluminescence and bacterial growth were assessed at 30 min from induction as described above. Likewise, the effect of overproduction of HapR on peps-lux activity was examined in both N16991 and O395. In addition, the function of HapR in regulation of eps expression was assessed in C6706 wild-type and isogenic ΔhapR knockout strains using the experimental design outlined above, as well as by monitoring the kinetics of eps-lux activity throughout 16 h of bacterial growth in LB medium at 37°C in a microtiter plate format, as explained previously. All data were collected during at least five independent experiments, and the reported values represent the means with accompanying SEM.

Design of a genetic screen and screening for eps regulators.

The V. cholerae O395 chromosomal DNA was purified using the Wizard DNA kit (Promega). Chromosomal DNA (25 μg) was partially digested with HincII and separated on a 1% agarose gel, and 2- to 7-kb DNA fragments were excised from the gel, purified, and cloned into HincII-digested pACYC177 (Table 1). The E. coli MC1061 transformants carrying the library plasmids and peps-lux were spread on LB agar supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol. Subsequently, all the colonies were screened for loss of resistance to a β-lactam antibiotic, carbenicillin, as successful cloning into the HincII site resulted in disruption of the bla gene carried within pACYC177. Individual bacterial colonies that failed to grow on LB agar plates containing carbenicillin were inoculated into each well on 96-well, white, clear-bottom plates (Greiner BioOne) containing 200 μl of LB medium supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol. The eps-lux activities (in RLU) and turbidities (OD600) of the cultures were measured after 16 h of static incubation at 37°C using a microplate reader as described above. The bioluminescence was normalized by bacterial growth (RLU/OD600). Clones showing significant changes in bioluminescence in comparison to the control strain, E. coli carrying both peps-lux and pACYC177, were reassayed. Plasmid DNA was isolated from bacterial cultures that displayed 6-fold or higher induction in the measured luminescence compared to the control strain. The inserted fragments of V. cholerae chromosomal DNA were sequenced using primers listed in Table 2. The sequences obtained were searched against the V. cholerae O395 genome in the KEGG database using BLASTn.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

The V. cholerae strains were grown as described in the text, and samples were withdrawn at the indicated time points of the experiments and centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 5 min to pellet bacterial cells. Subsequently, the cells were suspended in 1× LDS loading buffer (Invitrogen) supplemented with dithiothreitol (50 mM). Samples of whole-cell lysates were matched by equivalent OD600 units and resolved in 4 to 20% Tris-glycine gradient gels (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred onto 0.2 μM polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad) using Trans-blot Turbo (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked in 5% milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.0; Li-Core) supplemented with 0.1% Tween 20 and probed with polyclonal anti-EpsE antiserum (1:10,000 dilution) followed by incubation with Immun-Star goat anti-rabbit (GAR)-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Bio-Rad; 1:10,000 dilution). The immunoblots were developed using Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad) on a Chemi-Doc MP System (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analyses.

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software) and R version 3.0.2 base distribution. An unpaired Student's t test was used to analyze the data. Detrended (residual) correlations between the mean eps-lux activity levels for each of the experiments described above and shown in Fig. 1 were computed by first obtaining the overall mean eps-lux activity time series, averaging over all replicates across all experiments. Then, the detrended mean eps-lux time series were obtained by subtracting the overall mean time series from the mean time series for each experiment. Finally, Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient was used to assess the similarity in the residual time series between different experiments. A correlation coefficient near 1 indicates that the two residual time series exhibit almost exactly the same shape, whereas negative correlation coefficients result when one residual series tends to be high when the other is low, indicating different activity profiles.

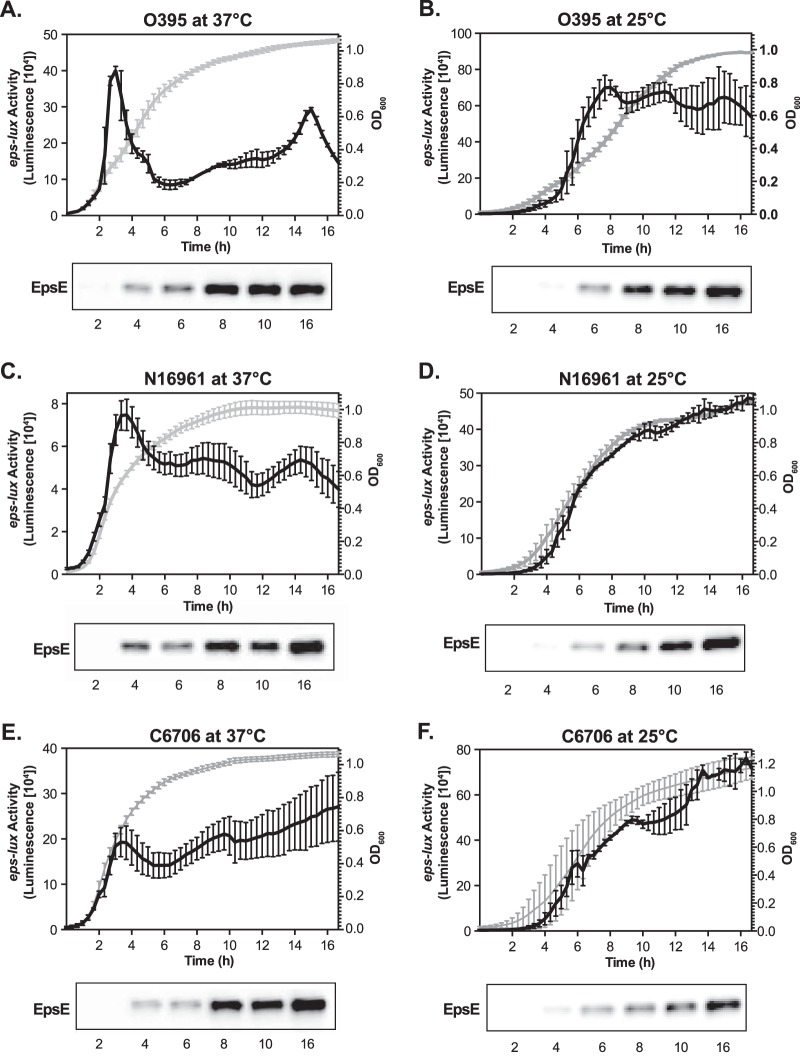

FIG 1.

Kinetics of eps expression in V. cholerae classical (O395) and El Tor (N16961 and C6706) strains. Expression of the eps-lux transcriptional fusion was monitored in V. cholerae O395 (A and B), N16961 (C and D), and C6706 (E and F). The bacterial strains were cultured in LB medium at either 37°C (A, C, and E) or 25°C (B, D, and F) in 96-well, white, clear-bottom microtiter plates. The turbidity of the cultures at OD600 (gray) and eps-lux activity (luminescence) (black) were assessed in technical triplicates and recorded every 20 min for 16 h. Each datum point represents the mean and SEM obtained from at least three independent experiments. The levels of the T2S component EpsE were detected in whole-cell extracts of V. cholerae strains by immunoblotting analyses with antisera against EpsE. Bacterial cells were withdrawn at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 16 h of growth, as indicated. Samples were matched by equivalent OD600 units.

RESULTS

Kinetics of expression of the T2S genes.

In V. cholerae, replacement of the 173 bp located upstream of the first gene in the epsC-N operon with the arabinose-inducible promoter PBAD allows the controlled biogenesis of the T2S complex, indicating that this chromosomal fragment contains the region driving expression of T2S (17, 24). To examine the expression of the T2S genes, we generated a transcriptional fusion, eps-lux, by placing this fragment of DNA in front of the promoterless luxCDABE operon located on a low-copy-number plasmid, pBBR322 (20). We chose this transcriptional reporter system because it permits uninterrupted monitoring of gene expression throughout bacterial growth if assays are executed in microtiter plates incubated in a plate reader. We reasoned that transcriptional expression of the T2S could be uniquely regulated in classical and El Tor biotypes of V. cholerae due to differences in the regulation of virulence factor production and transcriptome profiles (25, 26). Therefore, the plasmid carrying eps-lux was introduced by conjugation into classical (O395) and El Tor (N16961 and C6706) strains of V. cholerae. Subsequently, the kinetics of eps-lux expression (in RLU) and the turbidity of the cultures (OD600) were monitored continually every 20 min during 16 h of culture in LB medium at the temperatures encountered by the bacteria in the human host (37°C) and in the environment (25°C).

In all V. cholerae strains grown at 37°C, the eps-lux activity peaked in the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (at an OD600 of 0.5) and remained continuously expressed (Fig. 1A, C, and E). The constitutive transcriptional expression of T2S was also observed during growth under conditions either inducing or repressing virulence gene expression and in media triggering catabolite repression (LB broth supplemented with 0.4% glucose, maltose, or sucrose) (data not shown). Interestingly, during the cultivation of V. cholerae at the environmental temperature in either LB medium or marine broth, the transcriptional activity of eps-lux seemed to follow bacterial growth, which was particularly apparent in both El Tor strains (Fig. 1B, D, and F and data not shown). As expected, the proliferation rates of all bacterial strains were lower at 25°C than at 37°C, and mid-exponential growth stage was reached after about 6 and 8 h from back-dilution for the El Tor and classical isolates, respectively (Fig. 1). In addition, the lower temperature had a stimulatory effect on eps-lux expression, and the maximal values of detected transcriptional activity in O395, N16961, and C6706 were 1.75-, 6.88-, and 2.77-fold higher, respectively, than those measured at 37°C (Fig. 1). Immunoblotting analyses using antisera against the T2S ATPase EpsE showed that the overall transcriptional expression pattern corresponded to the expression of T2S at the protein level, although the detected amounts of EpsE were not increased at 25°C in comparison to those detected at 37°C. This discrepancy could be caused by the posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression or could be due to different protein stabilities.

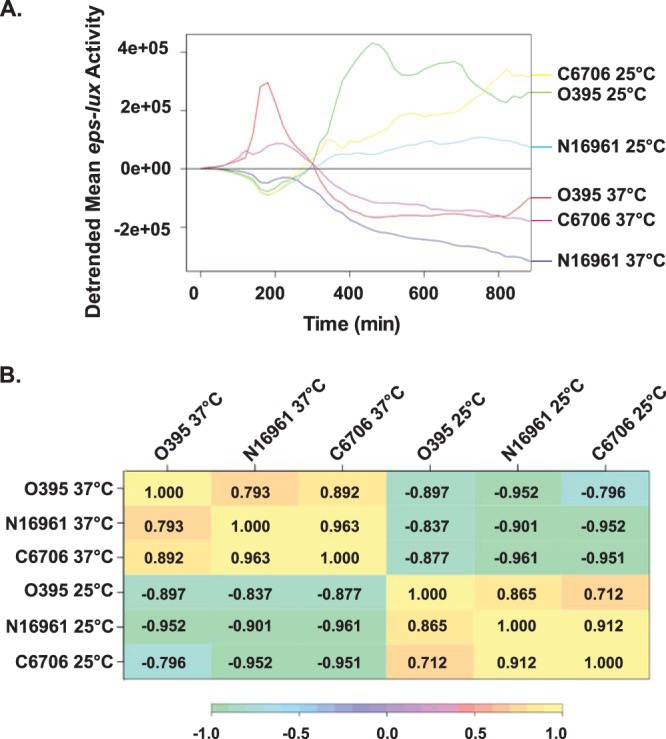

Next, we applied a series of statistical analyses to thoroughly compare the obtained eps-lux expression profiles shown in Fig. 1. The relationship between the eps-lux activity and bacterial growth was evaluated for each series using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Corroborating our earlier conclusions, the highest correlation was observed during the cultivation of V. cholerae at 25°C (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). This was especially clear in both El Tor strains, where the correlation values were 0.996 and 0.984 for N16961 and C6706, respectively. The lowest correlation between the eps-lux expression kinetics and bacterial growth (0.303) was observed in the classical strain at 37°C (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). To directly compare eps-lux expression from one V. cholerae strain-temperature combination to that from another, a correlation matrix for the six different mean eps-lux time series was computed, and a hierarchical-clustering dendrogram was constructed (see Fig. S1B and C, respectively, in the supplemental material). These analyses showed that in all V. cholerae isolates, eps-lux activities at 37°C grouped together, and the activities measured at 25°C clustered together (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material). Subsequently, the overall trend in eps-lux activity was computed as the overall mean time series and then detrended by subtracting the estimated trend series (Fig. 2 A). To assess the similarity in the residual time series of eps-lux expression in all V. cholerae strains and at all temperatures, Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficients were calculated. The detrended correlations between the time series in the different experiments provided strong evidence of similar patterns of eps-lux expression between classical and El Tor V. cholerae biotypes under common temperature conditions (Fig. 2B). Finally, we considered how the timing of the peak eps-lux luminescence differs between the strain-temperature experiments (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The time series of mean eps-lux luminescence was plotted in black, when there was a statistically significant difference (at an α level of 0.05) between the mean eps-lux luminescence at that time point and the peak mean, and it was plotted in red when there was no statistically significant difference between the mean eps-lux luminescence and the peak mean. This analysis showed that at 37°C, the peak eps-lux luminescence occurs around minute 200 in all V. cholerae strains (see Fig. S2A, C, and E in the supplemental material). There were, however, some differences among the three panels in that there was a sharp decline in the O395 strain at 37°C, whereas in the El Tor strains, the time series effectively plateau. In addition, the location of the peak was clearly influenced by the two different experimental temperatures (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

Detrended correlation of eps expression in V. cholerae. (A) The detrended mean time series of eps-lux activity in all examined V. cholerae strains cultured at 37°C and 25°C (as indicated) was computed by first estimating the overall mean time series and then subtracting the overall estimated mean trend series. (B) Correlation between the detrended mean time series and a heat map illustrating the correlation matrix. The correlation value legend is shown below.

In summary, these additional statistical explorations indicated common patterns between Fig. 1A, C, and E (eps-lux at 37°C) and similarly between panels B, D, and F (eps-lux activity at 25°C), which further supported the idea that in V. cholerae the transcriptional expression of T2S is temperature regulated. Despite the strong correlation in the detrended time series (Fig. 2B), a clear difference was still observed between the classical strain O395 and the El Tor strains in terms of the eps-lux activity profile, which seemed to peak more sharply in the classical strain than in the El Tor strains at a given temperature (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

HapR stimulates expression of T2S.

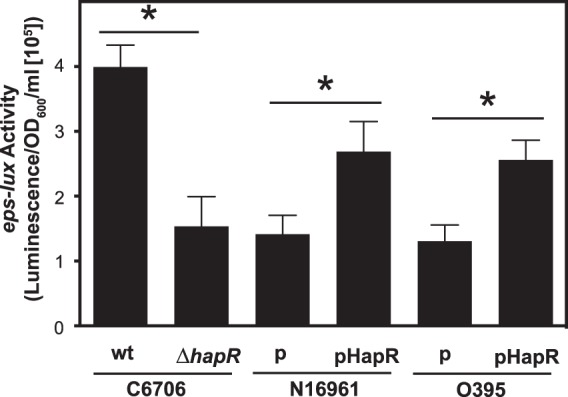

Quorum sensing has been shown to positively regulate the expression of T2S in several Gram-negative bacteria (27, 28). Among the V. cholerae strains utilized in our studies, only C6706 possesses a functional master regulator of quorum sensing, HapR (29, 30). We noted that although all the strains displayed similar eps-lux expression profiles at 37°C, there was a 2.8-fold difference in the peak of transcriptional activity (at 200 min) between the El Tor strains C6706 and N16961 (Fig. 1E and C; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Two lines of investigation were undertaken to determine whether HapR stimulates expression of T2S. The hapR knockout strain was constructed in V. cholerae C6706 using homologous recombination, and the hapR gene from strain C6706 was cloned under the control of the IPTG-inducible promoter PTAC, located on a broad-host-range plasmid, pMMB67-EH (Table 1). Subsequently, either p-HapR or the empty vector pMMB67-EH (p) was introduced by conjugation into N16961 and O395 carrying peps-lux. The bacterial strains were cultured in LB medium with aeration, and IPTG was added to all cultures in the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (OD600 = 0.5). The expression of eps-lux was determined 30 min posttreatment and normalized by bacterial growth (Fig. 3). The genetic inactivation of hapR resulted in a 2.6-fold decrease in the eps transcriptional activity. This difference was even more dramatic when the wild-type and isogenic hapR knockout strains of V. cholerae C6706 were cultured in a 96-well microtiter plate format (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Corroborating these findings, the ectopic overproduction of HapR resulted in statistically significant 1.9- and 1.96-fold increases in eps-lux expression in N16961 and O395, respectively, in comparison to the control strains carrying the empty plasmid (Fig. 3). Thus, we concluded, that HapR might positively regulate the expression of genes encoding the T2S system in El Tor and classical strains of V. cholerae.

FIG 3.

HapR stimulates expression of eps. The V. cholerae strains N16961 and O395 carrying either pMMB67-EH (p) or pHapR were grown with aeration in LB medium at 37°C until the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (OD600 = 0.5). Then, all the cultures were treated with IPTG at a final concentration of 100 μM. The activity of eps-lux was determined at 30 min postexposure and normalized by the density of the cultures. Means and SEM were obtained from five independent experiments (*, P < 0.05). wt, wild type.

Growth phase-dependent expression patterns of genes encoding T2S-dependent cargo proteins.

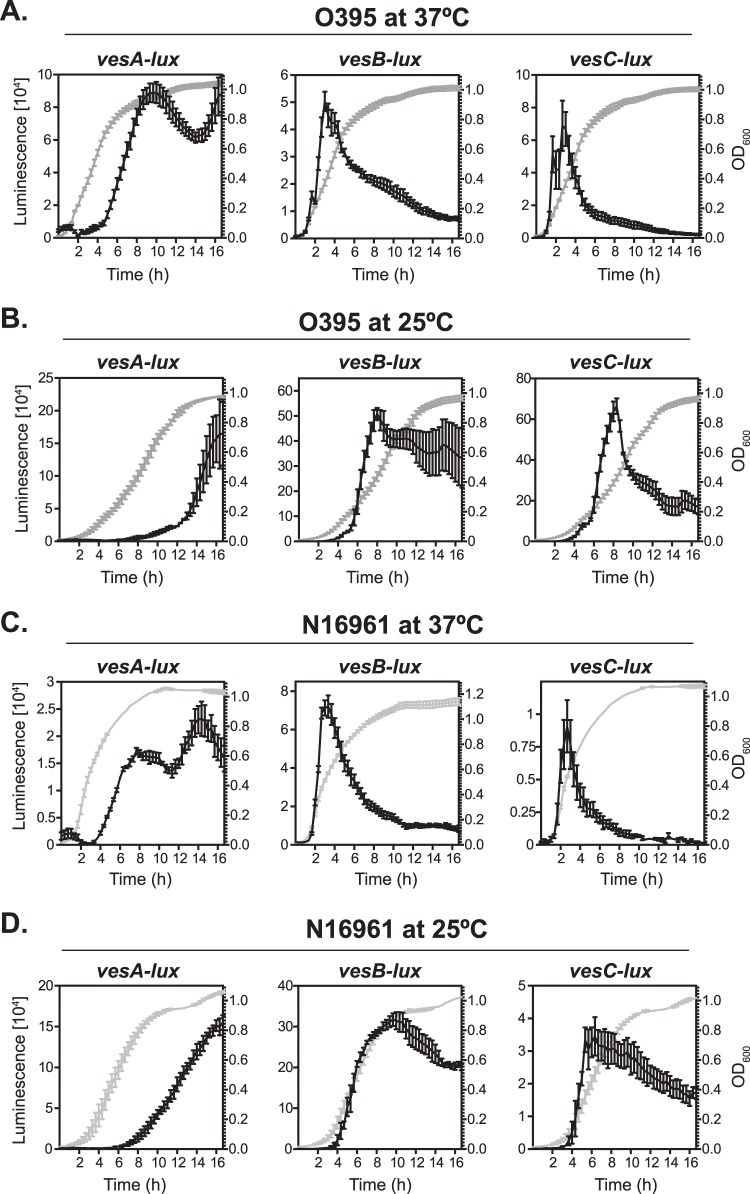

The pattern of expression of the T2S system could be dictated by the necessity to support the secretion of different cargo proteins at distinct phases of bacterial growth. It has been shown, for example, that GbpA is produced and secreted to the extracellular milieu in the early exponential phase, while secretion of HapA occurred in the stationary phase (31, 32). Given that T2S is responsible for the transport of at least 20 proteins (2, 14), we reasoned that other T2S-dependent proteins might display similar temporal expression patterns. To begin to address this hypothesis, transcriptional reporter fusions were constructed for four recently identified T2S-dependent exoproteins: the serine proteases VesA, VesB, and VesC, as well as a putative metalloprotease, TagA-related protein (Tarp) (14, 33). The individual plasmids pvesA-lux, pvesB-lux, pvesC-lux, and ptarp-lux were introduced into N16961 (as an El Tor representative) and the classical strain O395. Subsequently, the kinetics of expression of the respective cargo genes were assessed at both 37°C and 25°C in a 96-well microtiter plate format as described above. Although there were differences in the magnitudes of activities of individual transcriptional fusions between the analyzed strains, the overall patterns were strikingly similar during growth at 37°C. The transcription of vesA-lux reached maximum expression in the late stationary phase, while the activities of vesB-lux and vesC-lux peaked in the mid-exponential phase (Fig. 4A and C). At the environmental temperature, similarly to the eps-lux activity, the transcriptional expression of the examined T2S substrates was significantly increased in comparison to that at 37°C (Fig. 4). There were 2-, 10-, and 8-fold-higher bioluminescences measured for vesA-, vesB-, and vesC-lux fusions in O395, respectively, while in N16961, there were on average 7-, 4-, and 4-fold augmentations in expression of the respective cargo genes (Fig. 4B and D). Further, in the O395 strain, the expression curves of vesA- and vesC-lux at 25°C were similar to those observed at 37°C, while expression of vesB reached the maximum in the mid-logarithmic phase and was continuously expressed at similar levels through the end of the experiment (Fig. 4A and B). In the El Tor V. cholerae, expression of vesB followed bacterial growth, with a peak of activity shifted toward entry into the stationary phase (Fig. 4D). Further, expression of vesC did not show a distinct peak of activity, which was clearly noticeable in O395; instead, after reaching its maximum at the mid-exponential phase, it plateaued and gradually decreased after the bacterial cultures entered the stationary phase of growth (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, the activity of tarp-lux was diminished to the background level (RLU detected in bacteria carrying pBBRlux) in the examined strains under the tested growth conditions, with the exception of strain O395 cultured at 25°C, suggesting that expression of this T2S substrate is specifically regulated (Fig. 5; see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material).

FIG 4.

Growth phase-dependent expression of vesA, vesB, and vesC genes encoding T2S cargo proteins. Shown are the activities of the vesA-lux, vesB-lux, and vesC-lux transcriptional fusions in either O395 (A and B) or N16961 (C and D) cultured at either 37°C (A and C) or 25°C (B and D) in LB medium in 96-well microtiter plates. The turbidity of the cultures at OD600 (gray) and the RLU (black) were assessed in technical triplicates and recorded every 20 min for 16 h. Each datum point represents the mean and SEM (n = 4).

FIG 5.

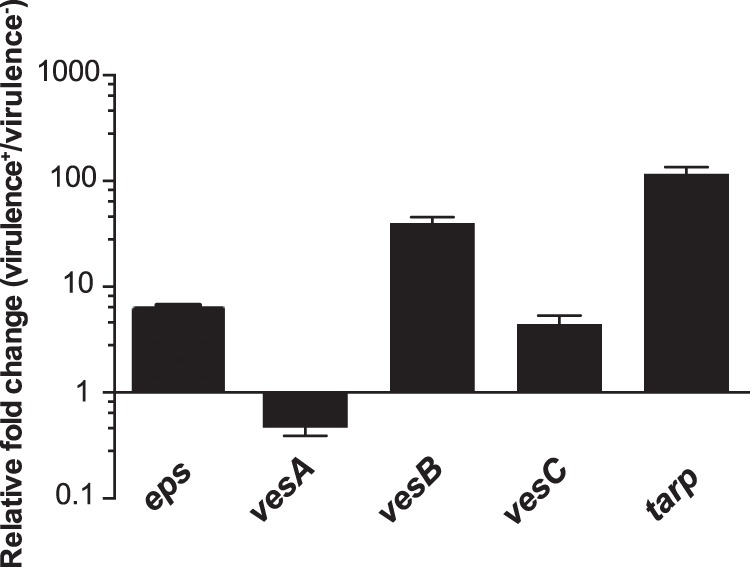

Transcriptional activities of T2S and its cargo proteins are differentially regulated under conditions inducing and repressing virulence gene expression. The expression of eps-lux, vesA-lux, vesB-lux, vesC-lux, and tarp-lux was assessed in classical V. cholerae O395 under conditions either inducing (LB, pH 6.5; 30°C) or inhibiting (LB, pH 8.5; 37°C) virulence gene expression. The highest promoter activity recorded for a particular growth condition was normalized by the OD600 of the bacterial culture. The relative fold change in gene expression was calculated by dividing the normalized promoter-lux activity under virulence gene-inducing conditions by its corresponding activity under virulence gene-inhibiting conditions. Each bar represents the mean and SEM obtained from at least four independent experiments.

Next, we asked whether the virulence-inducing and virulence-repressing conditions affect the transcriptional activities of eps and genes encoding selected exoproteins. In these experiments, we utilized a classical strain, O395, because it is well established that the production of cholera toxin and other crucial virulence factors in the classical biotype of V. cholerae can be maximized or minimized in the laboratory setting by culturing the bacteria in LB medium at initial pH 6.5 and 30°C or pH 8.5 and 37°C, respectively (19, 34). Under both conditions, the expression patterns for all tested promoter fusions were similar to those tested in LB at 37°C, with the exception of tarp-lux, which was active only under virulence-inducing conditions, with a peak of activity in the mid-logarithmic phase of V. cholerae growth (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material). The overall activities of eps, vesB, vesC, and tarp were 8-, 30-, 6-, and 100-fold upregulated, respectively, under virulence-inducing conditions, in comparison to those under virulence-inhibiting conditions (Fig. 5). In contrast, the expression of vesA was diminished by about 3-fold.

Together, these studies revealed the growth phase-dependent expression of four cargo genes and suggested a relationship between the pattern of transcriptional expression of T2S and its exoproteins. Future proteomic analysis will be required to address the secretion dynamics of the T2S-dependent secretory traffic.

Exogenous factors stimulating expression of eps.

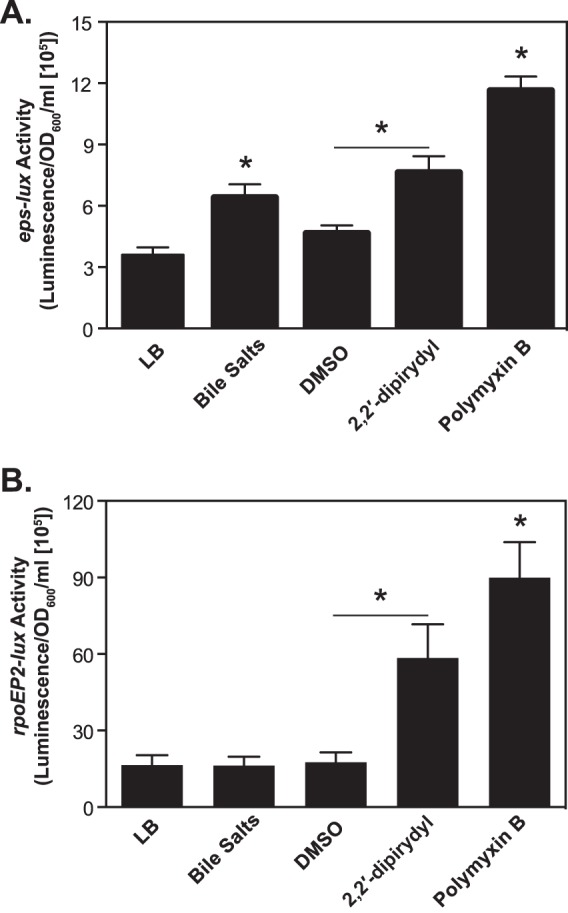

We subsequently examined whether other physiologically relevant stimuli besides temperature have an impact on eps transcriptional activity. During passage through the gastrointestinal tract, ingested V. cholerae faces several challenges, including nutrient competition (e.g., iron availability) and exposure to a number of different potentially toxic compounds, such as bile salts and antimicrobial peptides. In these experiments, V. cholerae carrying peps-lux was initially cultured under permissive conditions in LB medium at 37°C. Subsequently, when the turbidity reached an OD600 of about 0.5, equal volumes of cultures were split and either treated or not treated with bile salts (0.2%), iron chelator (2,2′-dipyridyl; 100 μM), and antimicrobial peptide (polymyxin B sulfate at 100 U or 50 U/ml for N16961 and O395, respectively). The eps-lux activity and bacterial growth were examined at 30 min postexposure (Fig. 6A and data not shown). All the tested compounds did not alter bacterial growth, while the eps-lux activity increased 1.5-, 2-, and 4-fold in comparison to the untreated or vehicle-treated (dimethyl sulfoxide) cultures of El Tor V. cholerae (Fig. 6A). The transcriptional activity of eps in the classical strain increased 1.4- and 2-fold after treatment with 2,2′-dipyridyl and polymyxin B sulfate, respectively, but was unaffected in the presence of bile salts (data not shown). Thus, our studies suggested that, in addition to temperature, other exogenous signals encountered by V. cholerae in the human host could also impact the expression of the genes encoding the T2S system. However, the secretion of cargo proteins, as examined by measurements of the extracellular serine- and metalloprotease activities, which are associated with a functional T2S pathway (2, 14), was not increased in the presence of these exogenous cues (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Expression of these cargo proteins likely remains under the control of different regulatory factors. At this point in the investigations, however, the possibility that the production and secretion of other exoproteins were not affected cannot be precluded.

FIG 6.

Expression of eps and rpoEP2 in V. cholerae N16961 in response to physiologically relevant environmental cues. V. cholerae N16961 harboring either peps-lux (A) or prpoEP2-lux (B) was cultured in LB medium at 37°C until the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (OD600, about 0.5). Subsequently, equal volumes of cultures were split into separate test tubes and either treated or not treated with bile salts (0.1% final concentration), iron chelator (2,2′-dipyridyl; 100 μM final concentration), DMSO (vehicle control), or antimicrobial peptide (polymyxin B sulfate; 100 U/ml). The expression of individual reporter fusions was determined at 30 min postexposure and normalized by the optical density of the cultures. Means and SEM were obtained from at least four independent experiments (*, P < 0.05).

Genetic screen to identify endogenous factors activating expression of eps.

We took a genetic-screening approach to gain insights into the endogenous factors of V. cholerae that regulate the transcriptional activity of the T2S complex. The chromosomal library of V. cholerae O395 was constructed by cloning 4- to 7-kb fragments within the bla gene located on a cloning vector, pACYC177. The library was introduced into the E. coli strain carrying peps-lux. After transformation, bacteria were spread onto LB agar plates supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol to select transformants carrying pACYC177 and peps-lux, respectively. All the bacterial colonies obtained were patched on LB agar with chloramphenicol and, additionally, with either kanamycin or carbenicillin. The E. coli cells that contained a cloned fragment of V. cholerae genomic DNA lost the ability to produce β-lactamase; therefore, only colonies that failed to grow on solid media containing carbenicillin were subjected to further analysis. A total of 3,000 isolates were individually inoculated into 96-well, white, clear-bottom microtiter plates and maintained without shaking in LB medium at 37°C for 16 h. Next, the eps-lux activity was assessed and normalized by the density of the cultures. Bacterial cultures showing 6-fold or more induction in eps-lux activity in comparison to the control (an E. coli strain carrying peps-lux and pACYC) were reassayed in triplicate. Subsequently, the inserted genomic DNA isolated from 50 colonies was sequenced. The cloned open reading frames (ORFs) clustered into several conserved regulatory pathways, including genes involved in activation of the RpoE (σE)-dependent cell envelope stress response (18 ORFs), phosphate metabolism (7 ORFs), and the production of the second-messenger molecule 3′,5′-cyclic diguanylic acid (c-di-GMP) (VC2697 and VC1372). In addition, we identified a homolog of a transcriptional activator, UhpA (VCA0682), and two LysR transcriptional regulators, AphB (VC1049) and VCA0830 (data not shown). These results suggested that expression of T2S might be regulated by multiple endogenous factors, which could act either directly or via interplay between different regulatory circuits.

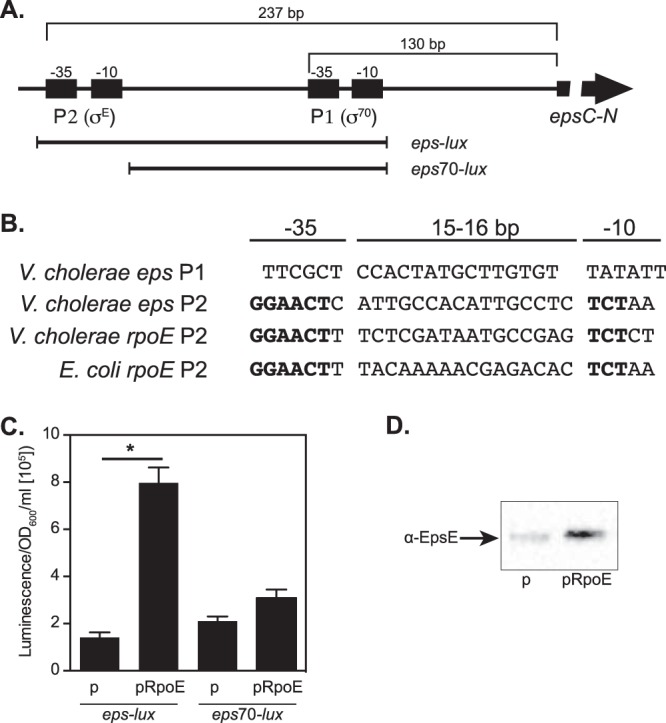

Organization of the eps regulatory region.

Supporting our genetic-screening experiments, a link between the T2S pathway and the extracytoplasmic stress response governed by σE was suggested previously (17, 18, 35). Inspection of the chromosomal fragment containing the entire regulatory region of the epsC-N genes (17) revealed the presence of two putative promoters, P1 and P2, located 74 and 193 nucleotides (nt) upstream of the ATG in the epsC gene, respectively (Fig. 7A). The P1 promoter, with the −35 sequence TTCGCT, had three mismatches with the consensus TTGACA, and the −10 sequence, TATATT, showed only one mismatch with the consensus TATAAT in the σ70 signature (Fig. 7B). The putative P2 promoter appeared to possess σE consensus. The −35 sequence, GAACTC, disclosed only a single mismatch with the V. cholerae and E. coli σE-dependent promoters, and the −10 sequence, TCTAA, perfectly matched the corresponding sequence in E. coli. In addition, the spacing between the two regions, 16 bp, was the same for these promoters (Fig. 7B). The rpoE genes in both V. cholerae and E. coli also possess similar regulatory arrangements. However, the σE-regulated promoter is localized 93 nt upstream of the ATG start codon, while the σ70-dependent promoter is located 309 to 310 nt upstream of rpoE (36). These findings further suggested that expression of the T2S complex is controlled by both a housekeeping σ70 and an alternative σE factor.

FIG 7.

Deletion studies of the V. cholerae eps regulatory region. (A) Diagram illustrating the distances between the epsP1 and epsP2 promoters from the epsC start codon, as well as constructs for deletion analysis of the eps regulatory region (not to scale). (B) Nucleotide sequences of the −35 and −10 regions of the promoters. Base pairs within the V. cholerae epsP2 promoter identical to those in rpoEP2 in V. cholerae and E. coli are indicated in boldface. (C) Effect of overproduction of RpoE on transcriptional activity of eps. The V. cholerae strains harboring plasmid pairs—empty pMMB67-EH (p) and peps-lux, pRpoE and peps-lux, pMMB67-EH and peps70-lux, or pRpoE and peps70-lux—were grown in LB medium at 37°C until the turbidity of the cultures reached an OD600 of about 0.5. Subsequently, IPTG (at 100 μM final concentration) was added to each culture. The expression of eps-lux and eps70-lux was measured 30 min posttreatment and normalized by the OD600. The bars represent means and SEM from five independent experiments (*, P < 0.05). (D) Overproduction of RpoE results in elevated levels of the T2S component EpsE. V. cholerae N16961 carrying either the empty vector pMMB67-EH (p) or pRpoE were grown in LB medium until the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (OD600 = 0.5). The expression of rpoE was induced by the addition of 100 μM IPTG, and the cultures were harvested after 30 min. Samples containing the whole-cell lysates were matched by equivalent OD600 units, resolved in 4 to 20% Tris-glycine gels, and transferred, and immunoblotting analysis was performed using rabbit antiserum against recombinant EpsE.

RpoE positively regulates expression of eps.

We decided to dissect the link between the RpoE and T2S pathways. First, to determine whether σE responds to the same environmental signals that induced expression of eps-lux, we utilized the rpoEP2-lux promoter fusion, containing the P2 promoter, whose expression is controlled by σE (17, 36). The presence of bile salts did not have any effect on rpoEP2-lux, whereas iron starvation and exposure to polymyxin B resulted in 4- and 6-fold increases, respectively, in transcriptional activity (Fig. 6B). Next, to directly assess the roles of P1 and P2 sequences in eps transcription and to test whether RpoE regulates expression of T2S genes, we constructed a truncated reporter fusion, eps70-lux, which lacked the σE-dependent P2 promoter (Fig. 7A). Subsequently, plasmids carrying individual promoter fusions, peps-lux and peps70-lux, were introduced into V. cholerae N16961 harboring either the empty vector pMMB67-EH or pMMB67-EH containing the rpoE gene cloned under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter, Ptac (pRpoE). The overproduction of RpoE resulted in over 4-fold induction of expression of eps-lux in comparison to V. cholerae harboring the empty plasmid. In contrast, overexpression of rpoE had no statistically significant effect on the transcriptional activity of eps70-lux (Fig. 7C). The immunoblotting analyses with anti-EpsE antisera additionally showed that RpoE positively regulated the expression of T2S at the protein level (Fig. 7D).

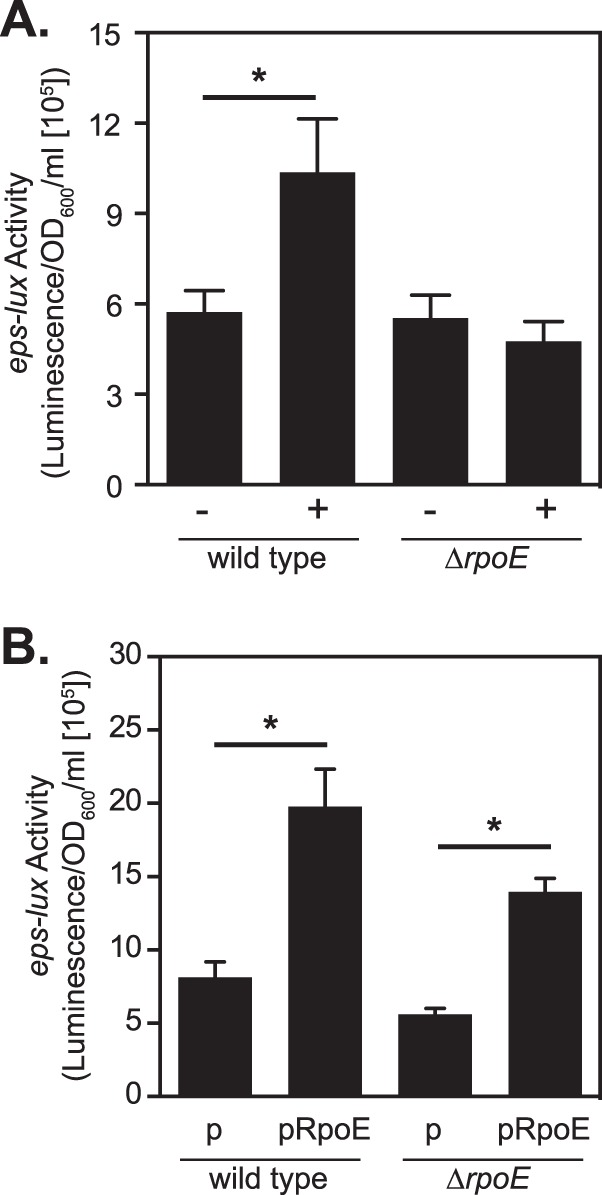

Finally, to confirm that σE plays a role in regulating expression of eps, in subsequent experiments, we utilized the ΔrpoE mutant and its parent strain, O395 (37). peps-lux was introduced into both strains, which were then subjected to treatment with polymyxin B as described above. There was a statistically significant 2-fold induction of eps-lux activity in the wild-type V. cholerae, while the activity remained unchanged in the ΔrpoE mutant in comparison to the untreated cultures (Fig. 8A). As expected, the ectopic overexpression of rpoE led to increased eps-lux transcriptional activity in both strains in comparison to the control cultures carrying an empty vector (Fig. 8B). In summary, these experiments demonstrated that the alternative sigma factor σE stimulates expression of genes encoding the T2S system in V. cholerae.

FIG 8.

Induction of transcriptional eps expression occurs in an rpoE-dependent manner. (A) The V. cholerae O395 wild-type and isogenic ΔrpoE knockout strains carrying a peps-lux reporter fusion were cultured in LB medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.5. Then, the cultures were divided into separate test tubes and either treated (+) or not treated (−) with polymyxin B (at 50 U/ml). The eps-lux activity was determined at 30 min postexposure and normalized by the turbidity of the cultures. (B) The V. cholerae ΔrpoE mutant and its parent O395 strain harboring the peps-lux reporter fusion and either pMMB67-EH (p) or pRpoE were cultured in LB medium at 37°C until the mid-logarithmic phase of growth (OD600 = 0.5). IPTG was added to all cultures at a 100 μM final concentration, and the eps-lux activity, as well as the OD600, was examined 30 min posttreatment. The means and SEM from five independent experiments are presented (*, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Significant research in the T2S field has been dedicated to elucidating the architecture and functions of individual constituents of the T2S system. In contrast, specific regulators of expression of the T2S complex and environmental conditions, as well as signaling required for its induction/inhibition, so far remain elusive in many bacterial species. During the nearly 20 years of research on the function of T2S in V. cholerae, regulation of the expression of this pivotal secretion pathway has not been addressed.

Here, we began to define the regulation of expression of T2S and several of its recently identified exoprotein genes. Our experiments, coupled with detailed statistical analyses, demonstrated common patterns of eps transcriptional activity between El Tor and classical V. cholerae isolates. T2S was constitutively expressed at 37°C in all the V. cholerae strains examined, while it followed bacterial growth during culture at the environmental temperature (Fig. 1 and 2). We concluded that quorum sensing did not directly contribute to the growth phase-dependent eps expression observed in V. cholerae at 25°C because, among the analyzed strains, only C6706 produces an active quorum-sensing master regulator, HapR (29, 30). On the other hand, genetic inactivation of hapR caused a 2.6-fold decrease in eps-lux activity in the C6706 strain, and consistently, the overproduction of HapR resulted in almost 2-fold induction of eps expression in strains N16961 and O395 (Fig. 2). Together, these results suggest that quorum sensing may influence the transcription of T2S genes in V. cholerae. A positive effect of quorum sensing on expression of the genes encoding the T2S pathway was also observed in Erwinia carotovora, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Burkholderia cenocepacia (27, 28).

Our experiments revealed that the lower temperature had a stimulatory effect on eps transcriptional activity (Fig. 1). Similarly, transcription of T2S genes was induced in Yersinia enterocolitica cultured at 26°C in comparison to those cultured at 37°C (38), whereas in enterotoxigenic E. coli, expression of the T2S gene cluster was repressed at lower temperature, which was mediated by the global regulatory proteins H-NS and StpA (39). Considering the recently revealed phylogenetic differences between the T2S secretins, it is possible that there is a broader bifurcation of T2S gene expression control across bacterial species (40). It is also tempting to speculate that the temperature-dependent T2S transcription patterns and the stimulatory effect of HapR in vibrios could contribute to their environmental fitness. In a nutrient-poor environment, it might be more cost-effective to delay energetically expensive secretion until a high density of the bacterial community is reached. In addition, the environmental temperature may also affect the pool of the intracellular signaling molecule c-di-GMP and thus activate expression of eps. V. cholerae has a plethora of proteins engaged in regulating expression of c-di-GMP levels, and in our genetic screen, we identified two of them, VC2697 and VC1372 (41). Global transcriptome analysis has shown that 4.5% of the genes of V. cholerae are differentially regulated upon exposure to elevated c-di-GMP concentrations. The genes encoding the T2S pathway were among the ones upregulated in both El Tor and classical biotypes of V. cholerae (42).

Proteomic profiling of the T2S secretomes in Dickeya dadantii, V. cholerae, and Legionella pneumophila revealed as many as 12, 21, and 25 exoproteins, respectively (14, 43, 44). A rigorous analysis of the T2S-dependent secretory traffic has not been undertaken, and it remains largely unknown when certain exoproteins are made, how long the cargo proteins reside in the periplasm, when they are secreted, and which of the exoproteins remain attached to the bacterial outer membrane, as well as for how long. The V. cholerae T2S secretome is large and diverse and could serve as a great model for studying the kinetics of this evolutionarily conserved secretion pathway. Among the recognized T2S-dependent exoproteins are cholera toxin, hemagglutinin protease (Hap), sialidase, lipase, several proteins participating in chitin utilization, aminopeptidases (LapA and LapX), Tarp, cytolysin, RbmC, serine proteases (VesA, VesB, and VesC), and three hypothetical proteins encoded by VCA0583, VCA0738, and VC2298 (14). To begin addressing the T2S-dependent secretory traffic, we investigated the expression of genes encoding the recently identified serine proteases and Tarp (14). Our studies demonstrated that the cargo genes examined displayed a growth-dependent expression pattern. Activation of expression of vesB, vesC, and tarp occurred in the mid-logarithmic phase of V. cholerae growth, while vesA peaked in the stationary phase (Fig. 4; see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). This phenomenon might have important consequences for V. cholerae pathophysiology, particularly when a functional interplay between cargo proteins is considered. This scenario is supported by studies conducted on a pair of T2S substrates, GbpA and HapA. A current model of this interaction proposes that GbpA is secreted during the initial phase of infection, where it aids the attachment of V. cholerae to human intestinal cells, while the secretion of HapA protease occurs later in infection, during “mucosal escape.” HapA is responsible for the degradation of GbpA, which may enhance the detachment of V. cholerae from the intestinal epithelium and facilitate its exit into the aquatic environment (31, 32, 45, 46). Another exciting possibility arising from our studies is that expression of the T2S complex is dictated by the secretory traffic in order to support the transport of different cargo proteins under various growth conditions and at distinct stages of bacterial growth. This line of research is currently being pursued in our laboratory.

Finally, our genetic-screening experiments suggested that the expression of the T2S pathway in V. cholerae might be regulated by several endogenous factors, including RpoE, the phosphate regulon, c-di-GMP, AphB, and the putative transcriptional regulators UhpA (VCA0682) and VCA0830. We focused our attention on dissecting whether σE plays a role in controlling the expression of T2S genes, because the link between the σE cell envelope stress response and T2S pathway in V. cholerae has been suggested previously. Specifically, the T2S knockout strains displayed compromised outer membrane integrity, altered levels of several outer membrane proteins, increased sensitivity to membrane-perturbing agents, and a dramatic induction of a σE-driven cell envelope stress response (17, 18). Here, we discovered that the regulatory region of T2S genes includes two promoters, P1 and P2, which resemble the σ70 and σE promoters, respectively (Fig. 7A and B) (36). Interestingly, a putative σE-dependent promoter near the start of gspC (ecfA), the first gene of the T2S operon, has also been identified in E. coli K-12 (47). Our studies showed that the removal of the σE consensus (P2 promoter) prevented activation of eps expression by RpoE (Fig. 7C). Additionally, ectopic overexpression of rpoE resulted in the elevated expression of genes encoding the T2S system at both the transcriptional and translational levels (Fig. 7 and 8). Corroborating these findings, genome-wide expression analysis revealed that the ΔrseA knockout strain, which overexpresses σE, displayed an approximately 3-fold increase in the mRNA levels of the epsC and epsE genes in comparison to those in wild-type V. cholerae (35). In addition, our studies presented in Fig. 6A and 8A showed that eps-lux expression increased significantly upon treatment with polymyxin B, an antimicrobial peptide, which is a known activator of the σE pathway (18, 48). Together, these data strongly suggest that σE may regulate expression of T2S in V. cholerae.

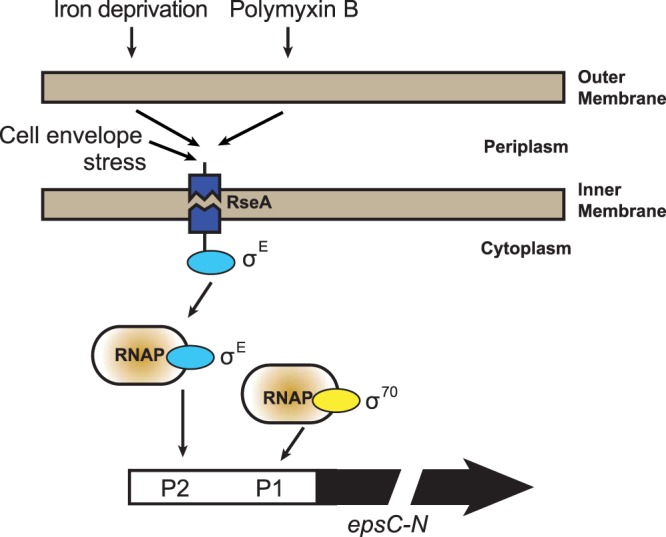

The use of alternative transcription start sites recognized by either σ70 or σE factors could provide the bacteria a fine-tuning mechanism for T2S that fits best with the conditions encountered in a particular ecological niche. As illustrated in Fig. 9, we propose that the expression of genes encoding the T2S pathway in V. cholerae remains under the control of a housekeeping σ70 and that σE takes over in response to specific exogenous stimuli (e.g., the presence of antimicrobial peptides or iron deprivation) or endogenous conditions (e.g., accumulation of misfolded proteins or a buildup of cargo proteins in the periplasm). This occurs by cascades of reactions, which lead to degradation of RseA and release of σE to allow it to bind to the core RNA polymerase (RNAP). T2S is a unique secretion pathway that, in addition to transporting soluble exoproteins, handles membrane-anchored proteins (6). In this respect, linking the T2S pathway with a sigma factor that deals with cell envelope stress may have important functional implications.

FIG 9.

Model showing a link between the T2S pathway and the alternative sigma factor σE.

Taken together, our results suggest that the T2S pathway is characterized by growth phase-dependent expression of genes encoding cargo proteins and requires a multifactorial regulatory network to ensure appropriate kinetics of the secretory traffic and fitness of V. cholerae during its dual life cycle.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by startup funds from OSU to A.E.S.

We thank Victor DiRita (University of Michigan) and Jyl S. Matson (University of Toledo) for providing wild-type and isogenic ΔrpoE mutant strains of V. cholerae O395. We are grateful to Maria Sandkvist (University of Michigan) for a generous gift of anti-EpsE antisera. We also thank Kim Gratz for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 14 April 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/IAI.01292-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sandkvist M. 2001. Type II secretion and pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 69:3523–3535. 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3523-3535.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sikora AE. 2013. Proteins secreted via the type II secretion system: smart strategies of Vibrio cholerae to maintain fitness in different ecological niches. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003126. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cianciotto NP. 2009. Many substrates and functions of type II secretion: lessons learned from Legionella pneumophila. Future Microbiol. 4:797–805. 10.2217/fmb.09.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans FF, Egan S, Kjelleberg S. 2008. Ecology of type II secretion in marine gammaproteobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 10:1101–1107. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korotkov KV, Sandkvist M, Hol WG. 2012. The type II secretion system: biogenesis, molecular architecture and mechanism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10:336–351. 10.1038/nrmicro2762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rondelet A, Condemine G. 2013. Type II secretion: the substrates that won't go away. Res. Microbiol. 164:556–561. 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandkvist M. 2001. Biology of type II secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 40:271–283. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02403.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overbye LJ, Sandkvist M, Bagdasarian M. 1993. Genes required for extracellular secretion of enterotoxin are clustered in Vibrio cholerae. Gene 132:101–106. 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90520-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaper JB, Morris JG, Jr, Levine MM. 1995. Cholera. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:48–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910–1914. 10.1126/science.272.5270.1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faruque SM, Asadulghani Saha MN, Alim AR, Albert MJ, Islam KM, Mekalanos JJ. 1998. Analysis of clinical and environmental strains of nontoxigenic Vibrio cholerae for susceptibility to CTXPhi: molecular basis for origination of new strains with epidemic potential. Infect. Immun. 66:5819–5825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis BM, Lawson EH, Sandkvist M, Ali A, Sozhamannan S, Waldor MK. 2000. Convergence of the secretory pathways for cholera toxin and the filamentous phage, CTXphi. Science 288:333–335. 10.1126/science.288.5464.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faruque SM, Mekalanos JJ. 2012. Phage-bacterial interactions in the evolution of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae. Virulence 3:556–565. 10.4161/viru.22351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sikora AE, Zielke RA, Lawrence DA, Andrews PC, Sandkvist M. 2011. Proteomic analysis of the Vibrio cholerae type II secretome reveals new proteins, including three related serine proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 286:16555–16566. 10.1074/jbc.M110.211078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. 2012. Cholera annual report 2011. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 87:289–30422905370 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandkvist M, Michel LO, Hough LP, Morales VM, Bagdasarian M, Koomey M, DiRita VJ, Bagdasarian M. 1997. General secretion pathway (eps) genes required for toxin secretion and outer membrane biogenesis in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 179:6994–7003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sikora AE, Lybarger SR, Sandkvist M. 2007. Compromised outer membrane integrity in Vibrio cholerae type II secretion mutants. J. Bacteriol. 189:8484–8495. 10.1128/JB.00583-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sikora AE, Beyhan S, Bagdasarian M, Yildiz FH, Sandkvist M. 2009. Cell envelope perturbation induces oxidative stress and changes in iron homeostasis in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 191:5398–5408. 10.1128/JB.00092-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller VL, Mekalanos JJ. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575–2583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenz DH, Mok KC, Lilley BN, Kulkarni RV, Wingreen NS, Bassler BL. 2004. The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell 118:69–82. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, III, Smith HO. 2009. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6:343–345. 10.1038/nmeth.1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645. 10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donnenberg MS, Kaper JB. 1991. Construction of an eae deletion mutant of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by using a positive-selection suicide vector. Infect. Immun. 59:4310–4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lybarger SR, Johnson TL, Gray MD, Sikora AE, Sandkvist M. 2009. Docking and assembly of the type II secretion complex of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 191:3149–3161. 10.1128/JB.01701-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiRita VJ, Neely M, Taylor RK, Bruss PM. 1996. Differential expression of the ToxR regulon in classical and E1 Tor biotypes of Vibrio cholerae is due to biotype-specific control over toxT expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:7991–7995. 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beyhan S, Tischler AD, Camilli A, Yildiz FH. 2006. Differences in gene expression between the classical and El Tor biotypes of Vibrio cholerae O1. Infect. Immun. 74:3633–3642. 10.1128/IAI.01750-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapon-Herve V, Akrim M, Latifi A, Williams P, Lazdunski A, Bally M. 1997. Regulation of the xcp secretion pathway by multiple quorum-sensing modulons in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1169–1178. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4271794.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Grady EP, Nguyen DT, Weisskopf L, Eberl L, Sokol PA. 2011. The Burkholderia cenocepacia LysR-type transcriptional regulator ShvR influences expression of quorum-sensing, protease, type II secretion, and afc genes. J. Bacteriol. 193:163–176. 10.1128/JB.00852-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu J, Miller MB, Vance RE, Dziejman M, Bassler BL, Mekalanos JJ. 2002. Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:3129–3134. 10.1073/pnas.052694299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joelsson A, Liu Z, Zhu J. 2006. Genetic and phenotypic diversity of quorum-sensing systems in clinical and environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 74:1141–1147. 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1141-1147.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jude BA, Martinez RM, Skorupski K, Taylor RK. 2009. Levels of the secreted Vibrio cholerae attachment factor GbpA are modulated by quorum-sensing-induced proteolysis. J. Bacteriol. 191:6911–6917. 10.1128/JB.00747-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benitez JA, Silva AJ, Finkelstein RA. 2001. Environmental signals controlling production of hemagglutinin/protease in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 69:6549–6553. 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6549-6553.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szabady RL, Yanta JH, Halladin DK, Schofield MJ, Welch RA. 2011. TagA is a secreted protease of Vibrio cholerae that specifically cleaves mucin glycoproteins. Microbiology 157:516–525. 10.1099/mic.0.044529-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skorupski K, Taylor RK. 1999. A new level in the Vibrio cholerae ToxR virulence cascade: AphA is required for transcriptional activation of the tcpPH operon. Mol. Microbiol. 31:763–771. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding Y, Davis BM, Waldor MK. 2004. Hfq is essential for Vibrio cholerae virulence and downregulates sigma expression. Mol. Microbiol. 53:345–354. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04142.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kovacikova G, Skorupski K. 2002. The alternative sigma factor sigma(E) plays an important role in intestinal survival and virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 70:5355–5362. 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5355-5362.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matson JS, DiRita VJ. 2005. Degradation of the membrane-localized virulence activator TcpP by the YaeL protease in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:16403–16408. 10.1073/pnas.0505818102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shutinoski B, Schmidt MA, Heusipp G. 2010. Transcriptional regulation of the Yts1 type II secretion system of Yersinia enterocolitica and identification of secretion substrates. Mol. Microbiol. 75:676–691. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06998.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Baldi DL, Tauschek M, Strugnell RA, Robins-Browne RM. 2007. Transcriptional regulation of the yghJ-pppA-yghG-gspCDEFGHIJKLM cluster, encoding the type II secretion pathway in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 189:142–150. 10.1128/JB.01115-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunstan RA, Heinz E, Wijeyewickrema LC, Pike RN, Purcell AW, Evans TJ, Praszkier J, Robins-Browne RM, Strugnell RA, Korotkov KV, Lithgow T. 2013. Assembly of the type II secretion system such as found in Vibrio cholerae depends on the novel pilotin AspS. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003117. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galperin MY, Nikolskaya AN, Koonin EV. 2001. Novel domains of the prokaryotic two-component signal transduction systems. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 203:11–21. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10814.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beyhan S, Tischler AD, Camilli A, Yildiz FH. 2006. Transcriptome and phenotypic responses of Vibrio cholerae to increased cyclic di-GMP level. J. Bacteriol. 188:3600–3613. 10.1128/JB.188.10.3600-3613.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coulthurst SJ, Lilley KS, Hedley PE, Liu H, Toth IK, Salmond GP. 2008. DsbA plays a critical and multifaceted role in the production of secreted virulence factors by the phytopathogen Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica. J. Biol. Chem. 283:23739–23753. 10.1074/jbc.M801829200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DebRoy S, Dao J, Soderberg M, Rossier O, Cianciotto NP. 2006. Legionella pneumophila type II secretome reveals unique exoproteins and a chitinase that promotes bacterial persistence in the lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:19146–19151. 10.1073/pnas.0608279103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirn TJ, Jude BA, Taylor RK. 2005. A colonization factor links Vibrio cholerae environmental survival and human infection. Nature 438:863–866. 10.1038/nature04249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong E, Vaaje-Kolstad G, Ghosh A, Hurtado-Guerrero R, Konarev PV, Ibrahim AF, Svergun DI, Eijsink VG, Chatterjee NS, van Aalten DM. 2012. The Vibrio cholerae colonization factor GbpA possesses a modular structure that governs binding to different host surfaces. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002373. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dartigalongue C, Missiakas D, Raina S. 2001. Characterization of the Escherichia coli sigma E regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20866–20875. 10.1074/jbc.M100464200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathur J, Davis BM, Waldor MK. 2007. Antimicrobial peptides activate the Vibrio cholerae sigmaE regulon through an OmpU-dependent signalling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 63:848–858. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05544.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casadaban MJ, Cohen SN. 1980. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 138:179–207. 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90283-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meselson M, Yuan R. 1968. DNA restriction enzyme from E. coli. Nature 217:1110–1114. 10.1038/2171110a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furste JP, Pansegrau W, Frank R, Blocker H, Scholz P, Bagdasarian M, Lanka E. 1986. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene 48:119–131. 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang AC, Cohen SN. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134:1141–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.