Abstract

The acrosomal matrix (AM) is an insoluble structure within the sperm acrosome that serves as a scaffold controlling the release of AM-associated proteins during the sperm acrosome reaction. The AM also interacts with the zona pellucida (ZP) that surrounds the oocyte, suggesting a remarkable stability that allows its survival despite being surrounded by proteolytic and hydrolytic enzymes released during the acrosome reaction. To date, the mechanism responsible for the stability of the AM is not known. Our studies demonstrate that amyloids are present within the sperm AM and contribute to the formation of an SDS- and formic-acid-resistant core. The AM core contained several known amyloidogenic proteins, as well as many proteins predicted to form amyloid, including several ZP binding proteins, suggesting a functional role for the amyloid core in sperm-ZP interactions. While stable at pH 3, at pH 7, the sperm AM rapidly destabilized. The pH-dependent dispersion of the AM correlated with a change in amyloid structure leading to a loss of mature forms and a gain of immature forms, suggesting that the reversal of amyloid is integral to AM dispersion.

INTRODUCTION

An essential step during fertilization is the sperm acrosome reaction (AR) in which the acrosome, an exocytotic vesicle overlying the sperm head, releases its contents, allowing the spermatozoon to penetrate the investments surrounding the oocyte. Point fusions between the outer acrosomal and plasma membranes result in membrane vesiculation, allowing the soluble contents to be released. The acrosome also includes an insoluble fraction called the acrosomal matrix (AM), which is defined as a membrane-free, electron-dense material that remains after spermatozoa are extracted with Triton X-100 (1). Functionally, the AM is thought to provide a stable scaffold that allows the controlled and sequential release of matrix-associated proteins during the AR, as well as to facilitate interactions between the sperm and oocyte (2, 3). While the mechanisms for the assembly and disassembly of the AM are not known, the self-assembly of proteins into a large complex has been proposed for its formation and disassembly is thought to be due to active proteases (1).

The site of the AR has been controversial and was previously thought not to occur in the mouse until spermatozoa encounter the zona pellucida, the thick coat surrounding the oocyte (4, 5). However, recent studies with video imaging microscopy to follow individual mouse spermatozoa with enhanced green fluorescent protein expressed in their acrosomes showed that, in fact, the fertilizing spermatozoa underwent the AR much earlier during transit through the cumulus cells prior to encountering the zona pellucida (6). Further studies indicated that these acrosome-reacted spermatozoa remained capable of binding and penetrating the zona pellucida (7). Together, these studies suggest that the AM, instead of the soluble components of the acrosome, is required for binding and penetration of the zona pellucida. The presence of several zona pellucida binding proteins, including zona pellucida 3 receptor (ZP3R) and zonadhesin (ZAN), in the sperm AM supports these findings (8–11). The AM therefore seems to have an unusual stability and is able to survive despite being exposed to the many proteases and hydrolases whose activities are likely necessary for sperm penetration of the cumulus cells. To date, the mechanism by which the AM has such profound stability has not been determined.

Amyloids are self-aggregated proteins in highly ordered cross beta sheet structures that typically are associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Accumulating evidence, however, indicates that amyloids can also be nonpathological and carry out functional roles. Pmel amyloid in melanosomes provides a stable scaffold for the synthesis of melanin, while in the pituitary gland, several hormones are stored as stable amyloid structures in secretory granules (12, 13). Recently, we showed that nonpathological/functional amyloid structures were present within the epididymal lumen, suggesting roles for amyloid in sperm maturation (14).

Because amyloids characteristically exhibit extreme stability, with some protease and SDS resistance (15), we hypothesized that amyloids within the sperm acrosome, in particular, the AM, contribute to the AM's inherent stability, which is integral for normal fertilization. We show here that amyloids are present within the mouse sperm AM and compose an SDS-resistant core structure with which other AM proteins associate. Proteomic analysis of this core structure revealed a distinctive group of proteins, including several known amyloidogenic proteins implicated in amyloidosis, as well as several well-characterized AM- and fertilization-related proteins predicted to have amyloid-forming domains. We also observed that incubation at pH 7 triggered a transformation in the AM amyloids that resulted in a loss of mature and a gain of immature forms of amyloid that correlated with the dispersion of the AM. These findings suggest that amyloid reversal is an integral part of AM dispersion. Together, these studies show that amyloids contribute to the formation of a stable scaffold within the AM that may play essential roles in fertilization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

CD1 retired breeder male mice from Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, were housed under a constant 12-h light-dark cycle and allowed free access to food and water. All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Isolation of testicular and epididymal spermatozoa.

Testicular spermatozoa were released from the testis by removing the tunica albuginea and dispersing the tubules by mincing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-protease inhibitor cocktail (PIC) (10 mM sodium phosphate, 137 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, containing a PIC [Complete Mini-EDTA-Free, catalog no. 11836170001; Roche, San Francisco, CA]). Caput and cauda epididymal tubules were punctured with a 30-gauge needle in PBS-PIC. Spermatozoa were allowed to disperse for 15 min at 37°C. The sperm suspensions were filtered through a 10-μm-pore-size nylon mesh (Medifab, catalog no. 07-10/2; Sefar Inc., Buffalo, NY), and the collected spermatozoa were washed two times in PBS-PIC by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min at room temperature (RT).

Mechanical disruption of sperm acrosomes and isolation of AM.

To mechanically detach acrosomes from spermatozoa, epididymal spermatozoa were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Pelleted cells were resuspended in PBS, vortexed for 2 min at RT, and centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Pelleted spermatozoa with disrupted acrosomes were resuspended in PBS. Isolation of AM from caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa was performed as described previously (16).

Isolation of AM core.

Total AM were incubated in 20 mM sodium acetate (SA), pH 3, containing 1% SDS for 15 min at 37°C. The sample was centrifuged at 42,000 × g for 5 min at 25°C to pellet the few nonextracted AM (P1). The supernatant containing the extracted AM and solubilized proteins (S1) was centrifuged at 250,000 × g for 30 min at 25°C. The resulting pellet (P2) was extracted in 20 mM SA (pH 3) containing 5% SDS for 15 min at 37°C. The sample was centrifuged at 250,000 × g for 30 min at 25°C, and the resulting pellet (P3) was the AM core. In some experiments, P2 was extracted with 70% formic acid for 15 min at 37°C and the sample was centrifuged as described above to generate P3.

Preparation of capacitated and acrosome-reacted spermatozoa.

Cauda epididymal spermatozoa were dispersed into Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate medium buffered with 25.1 mM NaHCO3 lacking CaCl2 (17). Next, 1.5 × 106 spermatozoa were aliquoted into 1.5-ml tubes (final concentration, 15 × 106 sperm/ml) and CaCl2 was added to a 1.7 mM final concentration. Capacitation was carried out with the tubes uncapped for 90 min at 37°C in a humidified, water-jacketed incubator under 5% CO2. Progesterone (catalog no. P8733; Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) was then added at a final concentration of 15 μM for 20 min of incubation to induce the AR.

Antibodies and fluorescent dyes.

Rabbit anti-fibrillar OC (catalog no. AB2286) and the rabbit anti-oligomer A11 (catalog no. AB9234) antiserum were from EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA. A protein A-purified A11 antibody (catalog no. AHB0052) was purchased from Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA (18, 19). The rabbit anti-human cystatin C antibody (CST3; catalog no. A0451) was from Dako, Carpinteria, CA (20). Rabbit anti-mouse CRES antibody (CST8) was generated in house (21). Rabbit anti-mouse ZAN antibody was kindly provided by Daniel Hardy, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (22). Rabbit anti-mouse lysozyme P (LYZ2) was a generous gift from Henry T. Akinbi, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated peanut agglutinin (PNA) lectin (catalog no. L7381) and thioflavin S (ThS; catalog no T1892) were purchased from Sigma, Saint Louis, MO.

Immunofluorescence analysis.

Different procedures based on samples and/or antibodies/dyes were used as described in Results. All samples were spread on microscope slides (Colorfrost Plus; Thermo Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) and allowed to dry overnight at RT. All samples were fixed with 100% methanol (Thermo Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) for 15 min at RT.

Spermatozoa and AM samples.

Slides were washed once in TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) for 2 min at RT and four times in TBST (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 300 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) and blocked in 100% goat serum (GS; catalog no. 16210; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for 1 h at 37°C. Slides were incubated with OC or A11 antiserum diluted 1:1,000 in TBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA; catalog no. A7511; Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) overnight at 4°C. Control slides were incubated with heat-inactivated normal rabbit serum (RS; 1:1,000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in place of OC or A11. Slides were washed with TBST five times for 2 min each time; this was followed by another blocking step as described above and incubation with 2 μg/ml goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody (Alexa-GAR, catalog no. A-11037; Invitrogen) in TBS containing 1% BSA for 30 min in the dark at RT. Slides were rinsed with TBST three times for 2 min each time and incubated with 10 μg/ml FITC-PNA in TBS for 20 min in the dark at RT. Slides were washed with TBST two times for 5 min each time, followed by TBS for 2 min in the dark at RT, and then rinsed once with MilliQ water, and coverslips were mounted with 15 μl Fluoromount G (catalog no. 0100-01; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL).

P3 core.

OC and A11 immunostaining was carried out as described above, except that Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS; containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 mM MgCl2; catalog no. 21-030; Cellgro, Manassas, VA) was used in place of TBS, blocking was carried out by incubating slides in 50% GS, and incubation with primary antibody was carried out at RT for 1 h. For ZAN immunostaining, slides were washed in DPBS for 5 min at RT and then blocked in DPBS containing 50% heat-inactivated GS (HIGS; catalog no. S-1000; Vector Laboratories) for 1 h at RT. Slides were then incubated with 3 μg/ml ZAN antibody diluted in DPBS containing 5% HIGS for 1 h at RT. Control slides were incubated with 3 μg/ml normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (catalog no. 3125; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) in place of ZAN antibody. For CST8, LYZ2, and CST3 immunostaining, slides were washed in DPBS for 5 min at RT and then incubated with 2 μg/ml CST8 or CST3 antibody or 1:1,000 LYZ2 in 10% GS–DPBS for 1 h at RT. Normal rabbit IgG (2 μg/ml; CST3, CST8) or normal RS (1:1,000; LYZ2) served as a control. Slides were washed with DPBS three times for 5 min each time and incubated with 2 μg/ml Alexa-GAR in DPBS containing 5% HIGS for 30 min in the dark at RT. Slides were rinsed with DPBS two times for 5 min each time and incubated with 10 μg/ml FITC-PNA in DPBS for 20 min in the dark at RT. Slides were washed with DPBS two times for 5 min each time, followed by TBS for 5 min in the dark at RT, and rinsed once with MilliQ water, and coverslips were mounted.

Different fractions obtained during P3 isolation were stained with FITC-PNA. After washing in DPBS for 5 min at RT, slides were incubated with 10 μg/ml FITC-PNA in DPBS for 20 min in the dark at RT. The samples were washed with DPBS two times for 5 min each time, followed by TBS for 5 min in the dark at RT, and rinsed once with MilliQ water, and coverslips were mounted.

For staining with ThS, slides were washed in TBS for 2 min at RT and incubated overnight at RT in the dark in 1% aqueous ThS solution filtered prior to use. Slides were washed in 80% ethanol two times for 1 min each time, followed by TBS for 1 min, and rinsed once with MilliQ water, and coverslips were mounted.

Fluorescence microscopy.

Images were captured with an epifluorescence microscope (BX60; Olympus, Center Valley, PA) attached to a digital camera (D100; Nikon, Melville, NY) with the following filter configurations: Alexa Fluor 594, excitation at 545 to 580 nm and emission at >610 nm; FITC-PNA, excitation at 480 nm and emission at 535 nm; ThS, excitation at 425 nm and emission at >475 nm).

X-ray diffraction.

AM were isolated from 40 × 106 cauda epididymal spermatozoa as described previously. An aliquot of total AM was spread on a slide and stained with FITC-PNA for counting of isolated AM and determination of whether any contamination with spermatozoa had occurred. A total of 13.9 × 106 AM (98% pure) were acetone precipitated overnight at −20°C. The precipitate was resuspended in 10 μl 5 mM ammonium acetate, pH 3. The solution was pulled up into a 0.7-mm quartz capillary tube and allowed to air dry for several days in the presence of desiccant. Sample diffraction was recorded with the Rigaku Screen Machine (Rigaku, The Woodlands, TX) X-ray generator with a focusing mirror (50 kV, 0.6 mA) and a mercury charge-coupled device detector. The distance from the sample to the detector was 75 mm, and CuKa radiation (1.5418 Å) was used.

Electron microscopy.

AM were adsorbed onto 200-mesh carbon-coated copper grids (catalog no. 01810; Ted Pella, Redding, CA), stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate (catalog no. 19481; Ted Pella), and visualized with a Hitachi H-8100 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Dallas, TX).

Dot blot and Western blot analysis.

Dot blotting was performed on 0.1-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membrane (catalog no. 10402062; Whatman, Dassel, Germany) with a Dot Blot 96 vacuum apparatus (catalog no. 053-401; Biometra, Goettingen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Membranes were equilibrated in TBS (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 200 mM NaCl) for 5 min at RT. With a low vacuum, membranes were rehydrated with TBS at 100 μl/well, samples were applied to the membranes (500 μl/well, three times) in 20 mM SA (pH 3)–0.05% SDS–3% methanol, and wells were rinsed with TBS at 200 μl/well (0.2% Tween 20). For analysis of ZAN, cystatin C, and lysozyme, P3 was resuspended in 13.2 mM SA (pH 3)–8 M urea–100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and incubated for 1 h at RT prior to the addition of 0.05% SDS and 3% methanol and spotting onto membrane. Analysis of CRES in P3 was done as described above but in the absence of DTT.

For Western blot analysis, proteins from AM samples were precipitated with 4 volumes of cold acetone and stored overnight at −20°C. The samples were then centrifuged at 17,200 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Precipitates and P3 samples were resuspended in 13.2 mM SA (pH 3)–8 M urea–100 mM DTT and incubated for 1 h at RT. Protein extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE according to the method of Laemmli (23) on a hand-cast gel (stacking, 4% polyacrylamide; resolving, 12% polyacrylamide). After electrophoresis, samples were electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (catalog no. IPVH00010; Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA) as described previously (24), with a Tris-glycine-methanol transfer buffer (25 mM Tris-base,192 mM glycine, 0.01% SDS, 10% methanol).

Dot blot and Western blot membranes were hybridized with antibodies as follows. Briefly, the membranes were blocked in 3% nonfat dry milk in TBST (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 200 mM NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20) for 1 h with gentle shaking at RT and then incubated with primary antibody (1:15,000 OC, 1 μg/ml affinity-purified A11, 0.4 μg/ml CST3, 56 ng/ml ZAN, 1:10,000 LYZ2, 185 ng/ml CST8) in 3% nonfat dry milk in TBST overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. After being washed three times for 10 min each time with TBST, the blots were incubated with a goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:10,000; catalog no. 65-6120; Invitrogen) in 3% nonfat dry milk in TBST for 2 h at RT. The blots were washed extensively in TBST, and the bound enzyme was detected by chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific catalog no. 34080 or Bio-Rad Laboratories catalog no. 170-5070) in accordance with the manufacturer's directions.

Gel electrophoresis and protein staining.

Proteins sequentially extracted from the AM during core purification were resolved by SDS-PAGE according to the method of Laemmli (23) and silver stained as described in reference 25. Briefly, AM, S1, S2, and S3 samples were precipitated with 4 volumes of cold acetone and stored overnight at −20°C. The samples were then centrifuged at 17,200 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Precipitates and P1, P2, and P3 samples were resuspended in 13.2 mM SA (pH 3)–8 M urea–100 mM DTT and incubated for 1 h at RT before the addition of reducing Laemmli buffer and electrophoresis on a 12% hand-cast Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gel. Lanes were equally loaded with proteins from 9 × 106 AM equivalents. The second P3 lane contained proteins from 4 × 107 AM equivalents separated on a 15% Tris-glycine Criterion gel (catalog no 345-0019; Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Preparation of samples for MS analysis.

Three different approaches were used to optimize the identification of peptides in the AM core. For in-gel digestion, P3 samples were resuspended in 13.2 mM SA (pH 3) containing 8 M urea and 100 mM DTT and incubated for 1 h at RT. Proteins were separated on a hand-cast 12% polyacrylamide Tris-glycine gel. After silver staining as described in reference 25, visible bands were cut from the gel, destained and washed with double-distilled H2O (two times for 5 min each time) and then with 50% ethanol (two times for 5 min each time) before being stored at −20°C. Gel pieces were tryptically digested as previously described (26) in 25 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer at 37°C overnight with 12 ng/μl trypsin (catalog no. V5111; Promega, Madison, WI).

For in-solution digestion, P3 samples were resuspended in 13.2 mM SA (pH 3)–8 M urea–100 mM DTT and incubated for 1 h at RT, followed by 15 min at 70°C. Iodoacetamide was added to 10 mM, and proteins were alkylated by incubation for 15 min at RT in the dark. Samples were added to a prerinsed spin filter (Amicon Ultra 30K or 10K device; catalog no. UFC503008/UFC501008; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and centrifuged at 14,000 × g (27). Samples were washed with 9 M urea and then with 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate. Samples were digested with 12 ng/μl trypsin in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate overnight. After digestion, samples were spun at 14,000 × g and washed two times with 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The retentate was transferred to a new tube and air dried.

For on-membrane digestion, the samples were dotted onto 0.1-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose membrane and digested by trypsin by a procedure adapted from reference 28. Briefly, P3 samples were resuspended and treated as for in-solution digestion. Samples were then dotted onto the membrane by gravity. Wells were rinsed with 20 mM SA (pH 3), followed by TBS. Dots were cut and air dried. After protein digestion with 12 ng/μl trypsin in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate, the membranes were dissolved with acetone and the precipitated peptides were air dried.

All digested peptides were reconstituted in 2% acetonitrile–0.1% formic acid for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis.

MS data acquisition.

Protein identification by liquid chromatography-tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) analysis of peptides was performed with an LTQ Orbitrap Velos MS (Thermo Scientific) interfaced with a 2D nanoLC system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA). Peptides were fractionated by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography on a PicoFrit column (75 μm by 10 cm) with a 15-μm emitter (catalog no. PF3360-75-15-N-5; New Objective, Woburn, MA) packed in house with Magic C18AQ (5 μm, 120 Å; Michrom Bioresources, Inc., Auburn, CA) with a 1 to 45% acetonitrile–0.1% formic acid gradient over 60 min at 300 nl/min. Eluting peptides were sprayed directly into an LTQ Orbitrap Velos at 2.0 kV. Survey scans (full MS) were acquired from 350 to 1,800 m/z with up to 10 peptide masses (precursor ions) individually isolated with a 1.2 Da window and fragmented (MS/MS) with a collision energy of HCD35, 30 s dynamic exclusion. Precursor and fragment ions were analyzed at 30,000 and 15,000 resolution, respectively.

Protein and peptide identification.

MS/MS spectra were extracted with the ProteoWizard Toolkit (29). The spectra were analyzed with the GPM Manager (version 2.2.1) and X!Tandem (30) to search against a homemade mouse database containing 213,054 nonredundant protein sequences created with mouse sequences from the Ensembl database (files Mus_musculus.GRCm38.73.pep.all and Mus_musculus.GRCm38.73.pep.abinitio) and from the NCBI database (file nr downloaded on 09/19/2013) as described in reference 16. Two searches were performed by using fully or semitryptic enzyme specificity (see deposited MS data for details). Peptides and proteins that have an expectation value of log10 (e) ≤ −2 were included in the results. Curated results were obtained by keeping only proteins with at least one mouse-specific matching peptide (a peptide match was defined as 100% identity with and 100% coverage of a unique mouse protein and <100% identity with and/or <100% coverage of a human protein). In addition, trypsin-like proteins were kept if at least one peptide did not match exogenous pig trypsins. Amyloid prediction was determined with Waltz (31) with parameters set as follows: threshold = best overall performance and pH = 2.6.

MS proteomic data accession number.

The MS proteomic data determined in this study have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository (32) with the data set identifier PXD000592.

RESULTS

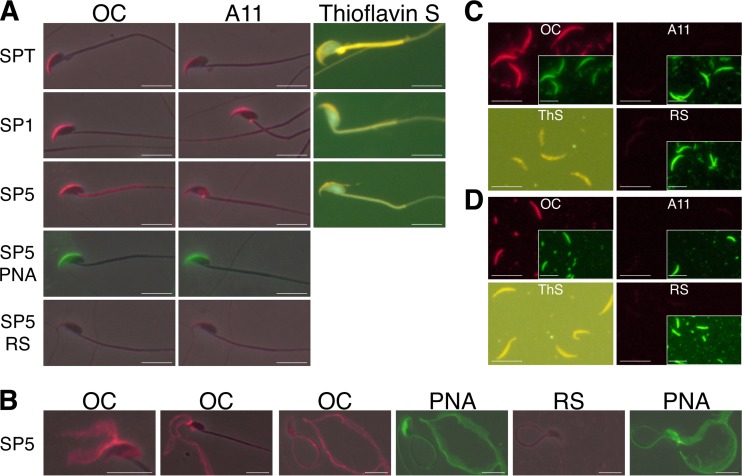

To determine if amyloids were present in the acrosome, mouse spermatozoa were isolated from the testis and caput and cauda epididymis and indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) analysis was carried out with conformation-dependent antibodies A11 and OC. The A11 antibody recognizes early, immature forms of amyloid, including oligomers, while OC recognizes more mature forms of amyloid, including fibrils (18, 33). FITC-PNA (Arachis hypogaea) lectin specifically binds terminal galactose residues and served as a marker for the sperm acrosome and AM (34). Staining with both A11 and OC was present in the PNA-positive acrosome from immature (testis, SPT; caput, SP1) and mature (cauda, SP5) spermatozoa, suggesting the presence of amyloid (Fig. 1A; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material for additional images and for merged data). A slight increase in OC staining paralleled a decrease in A11 staining between testicular and cauda epididymal spermatozoa, suggesting that the transition from immature to mature forms of amyloid may be associated with sperm maturation in the epididymis. A population of A11-positive material was also observed at an undefined spot in the sperm neck distinct from the acrosome. Sperm acrosomes were also stained with ThS, a fluorescent dye that binds to the beta sheet rich structures of amyloid but not to monomers (35), supporting the idea that amyloid was present (Fig. 1A). We next used mechanical disruption by centrifugation to partially detach the acrosome from the sperm head, allowing us to examine the isolated structure. Various degrees of dispersion were observed with some acrosomal shrouds showing an almost complete separation into two bilayers as they detached from the sperm head, which we believe represents the acrosomal membranes with associated AM material. The dispersed acrosomal material was strongly labeled with the OC antibody supporting the idea that this material contained amyloid (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Amyloids are present in mouse sperm acrosomes. Amyloids were detected by IIF analysis with OC and A11 antiserum (red fluorescence) and by ThS staining. Normal RS was used as a control. All slides were costained with FITC-PNA (green fluorescence) as a marker for acrosomal material. Phase-contrast and epifluorescence images were merged informatically. Scale bars, 10 μm. (A) Intact spermatozoa from the testis (SPT), caput (SP1), and cauda (SP5) epididymis. (B) Cauda epididymal spermatozoa (SP5) with mechanically disrupted acrosomal shrouds in various states of detachment and dispersion. (C and D) Isolated AM (total) from caput epididymal (C) and cauda epididymal (D) spermatozoa. Insets show FITC-PNA staining shown at a 40% reduction.

To specifically examine the AM without associated membranes, intact AM were isolated from caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa by a procedure previously developed in our laboratory and examined for amyloid with the OC and A11 antibodies and ThS staining. Briefly, following extraction with Triton X-100 to remove membranes, the spermatozoa were vortexed in buffer at pH 3 and released intact AM were separated from spermatozoa by low-speed centrifugation with the AM going into the supernatant (total AM) (16). In our previous studies, we used antibodies against known AM proteins, including proacrosin (ACR), ZAN, and ACR binding protein (ACRBP), in immunofluorescence and Western blot analyses to confirm the isolated material was indeed AM (16). Although PNA-positive structures were present in all of the samples, OC but not A11 immunostaining was detected in the AM from caput (Fig. 1C) and cauda (Fig. 1D) epididymal spermatozoa. These data suggested that while OC-positive mature forms of amyloid were present in the AM, the immature A11 forms of amyloid detected in the intact acrosome may have been associated with the sperm membranes removed by Triton X-100 or in the soluble fraction that was not retained on the slide during IIF analysis. ThS staining confirmed the presence of amyloid in AM isolated from both caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa (Fig. 1C and D). We observed that the cauda AM, despite being in pH 3 buffer, which helped to keep the AM stable, dispersed more readily than caput AM, as indicated by the loss of a well-defined crescent shape (Fig. 1D).

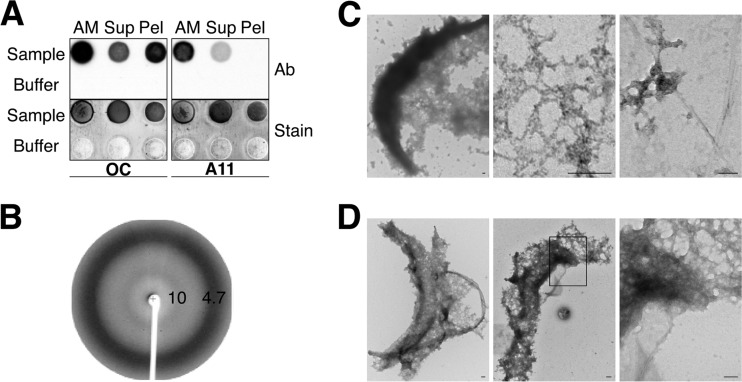

Several approaches were next used to confirm the presence of amyloid in AM isolated from cauda epididymal spermatozoa. Dot blot analysis with conformation-dependent antibodies allowed us to examine the total AM fraction, as well as AM that was then centrifuged at low speed to separate soluble from insoluble components. Both OC and A11 were detected in the total AM sample, as well as the soluble fraction (Sup), while only OC immunoreactivity was detected in the AM pellet (Pel) fraction (Fig. 2A). These results suggested that during the isolation procedure, some amyloids were dispersed from the intact AM such that they did not pellet following centrifugation. X-ray fiber diffraction was next carried out to examine the structure of the isolated AM. Two reflections, at 4.7 and 10 Å, were observed that are characteristic of cross beta sheet structure in amyloid (36) (Fig. 2B). AM isolated from the caput and cauda epididymal spermatozoa were also examined by negative stain electron microscopy. As shown in Fig. 2C and D, both samples showed the presence of crescent-shaped structures with which matrix material was associated, including some individual fibrils (Fig. 2C, third panel), which is consistent with amyloid. The crescent-shaped structures are similar to what has been previously observed by electron microscopy in AM isolated from other species, including the guinea pig (2, 37).

FIG 2.

Purified AM are composed of amyloids. (A) Dot blot analysis with OC and A11 antibodies (Ab) of total AM, soluble AM (Sup), and insoluble AM (Pel) fractions isolated from cauda epididymal spermatozoa. Buffer only served as a control. Colloidal gold staining (Stain) was performed after dot blot analysis to confirm the presence of protein in each spot. (B) X-ray fiber diffraction analysis of AM isolated from cauda epididymal spermatozoa. (C and D) Negative-staining electron microscopy of AM isolated from caput (C) and cauda (D) epididymal spermatozoa. The boxed area in the middle section of panel D is magnified in the right panel. Scale bars, 10 μm.

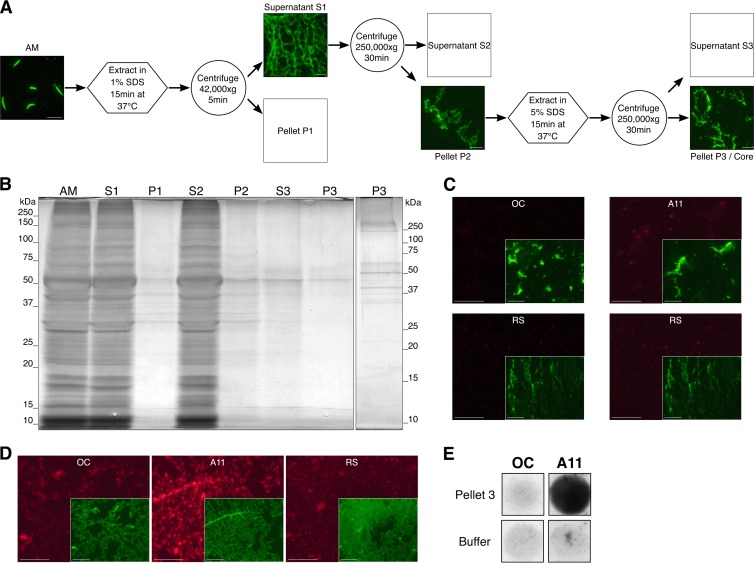

Although proteins are released from the AM during the AR, some AM remains associated with the sperm head to allow interactions with the zona pellucida, suggesting that a stable infrastructure is present that is not easily dispersed (38, 39). We wondered if we could extract proteins from the AM to a point that a stable, nonextractable structure remained and, if so, if this structure would contain amyloid. Following the procedure outlined in Fig. 3A, AM extraction with 1% SDS resulted in the solubilization and release of the majority of the AM proteins into the supernatant fraction (S2) as determined by silver staining of gel-purified proteins (Fig. 3B). The remaining insoluble pellet (P2) was then extracted with 5% SDS, which resulted in a further loss of proteins (S3) yet allowed an FITC-PNA-positive core structure (P3, Fig. 3A) that contained few proteins visible by silver staining (Fig. 3B) to remain. Examination of the AM core (P3) by IIF analysis detected A11-positive material, indicating the presence of amyloid (Fig. 3C). However, in contrast to the starting AM material rich in OC (Fig. 1D), the core structure had lost OC staining. These results were confirmed by dot blot analysis (Fig. 3E). Together, the data suggested that during the SDS extractions, the OC-positive material reflecting mature forms of amyloid were reversing to immature forms of amyloid that were now A11 positive. Alternatively, SDS extraction resulted in the exposure of existing A11-positive amyloids. Extraction of P2 with 70% formic acid instead of 5% SDS also resulted in the presence of a resistant core structure in P3 that was rich in A11 amyloid but lacked OC-reactive amyloid (Fig. 3D).

FIG 3.

The AM contains an amyloid-rich core structure. Purified AM were exposed to a two-step extraction to sequentially strip off soluble proteins (A and B). The presence of amyloid in the remaining insoluble material (core) was determined by IIF analysis (C and D) and dot blot analysis (E) with OC and A11 antibodies. (A) Isolated AM were incubated in 1% SDS in 20 mM SA (pH 3) for 15 min at 37°C and then centrifuged at 42,000 × g for 5 min to pellet nonextracted AM (P1). The supernatant (S1) containing the extracted AM and solubilized proteins was centrifuged at 250,000 × g for 30 min. The pellet (P2) was then extracted in either 5% SDS or 70% formic acid for 15 min at 37°C, and samples were centrifuged at 250,000 × g. The pellet (P3) represented the AM core. AM, S1, P2, and P3 were stained with FITC-PNA. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE of proteins sequentially extracted from the AM during purification of the core. Lanes were equally loaded with proteins from 9 × 106 AM equivalents. Proteins were solubilized in 8 M urea–100 mM DTT before the addition of reducing Laemmli buffer and electrophoresis. The second P3 lane contains proteins from 4 × 107 AM equivalents. (C and D) P3 obtained by extraction in 5% SDS (C) or 70% formic acid (D) was examined by IIF analysis with OC and A11 antibodies (red fluorescence). Normal RS served as a control antibody. Insets, P3 costained with FITC-PNA (green fluorescence) and shown at a 40% reduction. Scale bars, 10 μm. (E) P3 obtained by extraction in 5% SDS was dotted onto nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with OC and A11 antibodies in a dot blot analysis.

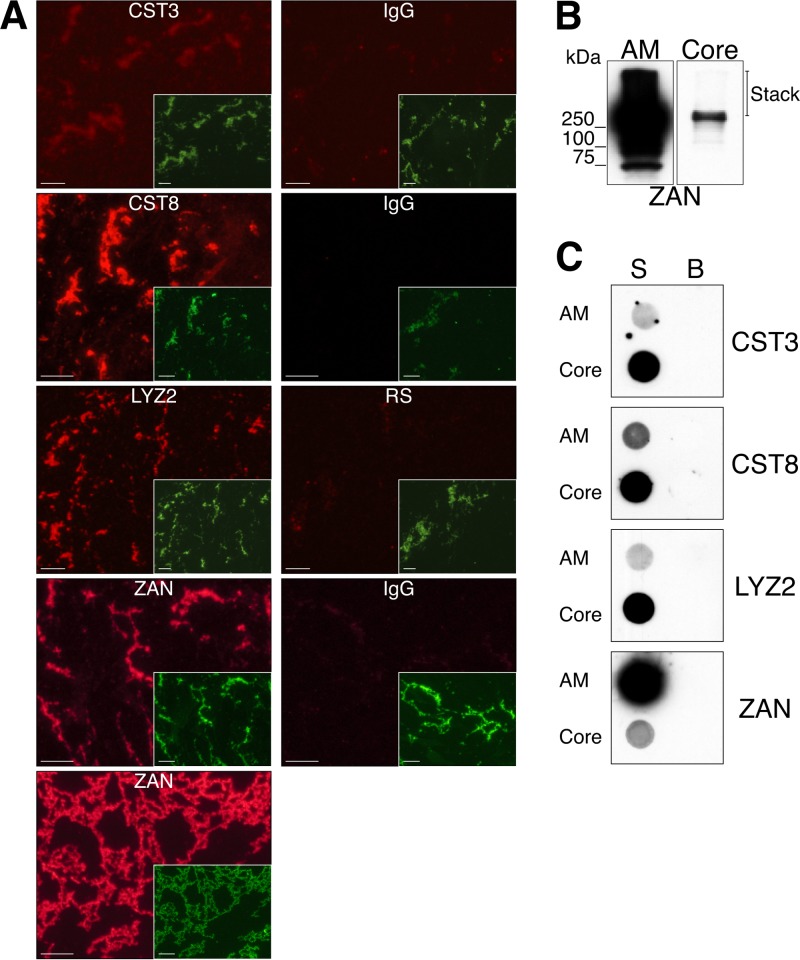

Two approaches were used to identify proteins that contributed to the formation of the AM core, including LC-MS/MS and the use of specific antibodies to examine candidate proteins in IIF, Western blot, and dot blot analyses. For LC-MS/MS, resuspension of P3 in 8 M urea–100 mM DTT, followed by heating and immediate pipetting of the sample onto filters, was required to solubilize the core. Analysis of the core revealed several distinct groups of proteins, the majority of which were either established amyloidogenic proteins or, based on our analysis using the Waltz program, contained one to multiple regions that were predicted to be amyloidogenic (Table 1; see Table S1 in the supplemental material for the full list). Known amyloidogenic proteins, of which several are implicated in amyloidosis, included lysozyme (Lyz2) (40), cystatin C (Cst3) (41), cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic protein (CRES or Cst8) (42), albumin (Alb) (43), and keratin (Krt1 or Krt5) (44). Proteins that were related to known amyloidogenic proteins included phosphoglycerate kinase 2 (Pgk2) (45) and transglutaminase 3 (Tgm3) (46). Several proteins in the core that had predicted amyloidogenic domains have associations with neurodegenerative diseases and include low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (Lrp1) (47, 48), nebulin-related anchoring protein (Nrap) (49, 50), and arginase (Arg1) (51) (see Table S1). The AM core also contained several established AM proteins, including ZP3R (8, 52), ZAN (53), ACRBP (54), sperm equatorial segment protein 1 (Spesp1) (55, 56), and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (Dld) (57), as well as other proteins implicated in fertilization, such as serine protease 2 (Prss2) (58) and GM128 (59) (Table 1; see Table S1). Finally, structural proteins such as desmoplakin (Dsp) were also present in the AM core (see Table S1). The presence of ZAN in the core was confirmed by using specific antibodies in Western blot, dot blot, and IIF analyses (Fig. 4A to C). The ZAN that remained in the AM core represented a small yet distinct population since most of the ZAN in the AM was solubilized by SDS (Fig. 4B). IIF and dot blot analyses also confirmed the presence of the known amyloidogenic proteins CST3, CST8, and LYZ2 in the AM core (Fig. 4A and C).

TABLE 1.

Selected mouse AM core proteins

| Method(s) and MGIa ID | Designation | Gene product | Previous identification(s)b (reference[s]) | Presence of amyloidogenic regions (reference) [no. of regions]c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS | ||||

| MGI:87991 | Alb | Albumin | SPZHa (78), AMM (16) | Yes (43) [8] |

| MGI:96698 | Krt1 | Keratin 1 | SPZM (79), AMM (16) | Yes (44) [8] |

| MGI:96702 | Krt5 | Keratin 5 | SPZR (80), AMM (16) | Yes (44) [8] |

| MGI:97563 | Pgk2 | Phosphoglycerate kinase 2 | SPZM (81), AMM (16) | Yes (45) [6] |

| MGI:98732 | Tgm3 | Transglutaminase 3 | TES (82)M | Yes (46) [14] |

| MGI:1859515 | Acrbp | Proacrosin binding protein | AM (2, 16)GP,M | NYD [2] |

| MGI:107450 | Dld | Dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase | AM (57)Ha | NYD [3] |

| MGI:1913962 | Spesp1 | Sperm equatorial segment protein 1 | AMH,M (16, 55) | NYD [9] |

| MGI:104965 | Zp3r | Zona pellucida 3 receptor | AMM (8) | NYD [7] |

| Both, MGI:106656 | Zan | Zonadhesin | AMP,M (16, 53) | NYD [44] |

| Candidate | ||||

| MGI:102519 | Cst3 | Cystatin C | ACRR (83), AMM (16) | Yes (41) [4] |

| MGI:107161 | Cst8 | Cystatin 8d | ACRM (84), AMM (16) | Yes (42) [3] |

| MGI:96897 | Lyz2 | Lysozyme 2 | None | Yes (40) [2] |

MGI, Mouse Genome Informatics database; Both, proteins identified by LC-MS/MS and by the candidate approach (specific antibodies were used to detect candidate proteins by IIF, Western or dot blot analysis).

Proteins were previously identified in testis (TES), spermatozoa (SPZ), acrosome (ACR), or AM. Superscripts: GP, guinea pig; Ha, hamster; H, human; M, mouse; P, pig; R, rat.

Yes, previously shown to be amyloidogenic; NYD, not yet determined. Each value in brackets is the number of predicted amyloidogenic regions based on our analysis using the Waltz program.

Cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic protein.

FIG 4.

Immunodetection of proteins in the AM core. (A) The AM core obtained by extraction with 5% SDS was spread on slides and immunostained with CST3, CST8, LYZ2, and ZAN antibodies (red fluorescence). Last panel, AM core obtained by extraction with 70% formic acid and immunostained with ZAN antibody. Control staining was carried out with normal rabbit IgG or serum (RS). Insets, costaining with FITC-PNA shown at a 50% reduction. Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) Western blot analysis of ZAN in total AM and AM core fractions. Proteins from 5 × 106 and 6 × 107 AM equivalents were loaded into the total AM and AM core lanes, respectively. (C) Dot blot analysis of CST3, CST8, LYZ2, and ZAN in total AM and AM core fractions. The AM and AM core proteins were dotted onto nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with the relevant antibodies. Proteins from 1 × 106 and 3 × 107 AM equivalents were dotted for AM and AM core, respectively. S, sample, B, buffer.

We next followed the fate of acrosomal amyloids during sperm capacitation, a process that involves membrane remodeling and which precedes the AR, and during the AR to examine the amyloid structures under biological conditions that mimic fertilization events in vivo. Spermatozoa were capacitated in a defined medium at pH 7.4, and the AR was induced by the addition of progesterone, which in vivo is secreted by cumulus cells and is thought to function as an inducer of the AR (60). Strong OC staining of the acrosome remained throughout the capacitation time course. Following the addition of progesterone, which caused the majority (>90%) of spermatozoa to undergo the AR, an OC-positive acrosomal shroud detached from the sperm head and quickly dispersed into a thin, film-like matrix (Fig. 5). As the shroud dispersed and became thinner, it became difficult to detect OC staining by IIF analysis. These studies suggested that, similar to our studies with mechanical disruption, an amyloid-containing acrosomal shroud is detached from the sperm head during the AR. Similar acrosomal shrouds have been observed in spermatozoa from other species induced to undergo the AR in vitro (39), as well as in acrosome-reacted spermatozoa in vivo (38). In contrast to the relative stability of the acrosomal shrouds kept at pH 3, the induction of the AR at pH 7.4 resulted in rapid dispersion of the shroud and disappearance of OC staining. At this time, we cannot rule out the possibility that A11-positive forms of amyloid were also present as a result of the dispersion of the acrosomal shroud during the AR but were lost during the IIF analysis procedure or rapidly transitioned into monomeric forms. However, following the loss of the acrosomal shroud with AR, strong A11 immunoreactivity was observed adjacent to the PNA-positive sperm equatorial segment, the posterior aspect of the acrosome which remains associated with the spermatozoa following the AR and which includes inner acrosomal membrane with associated AM (61) (Fig. 5). This region is the site of sperm-oocyte membrane fusion (62). Together, these studies suggested that induction of the AR triggered activities within the acrosome that were responsible for the changes in amyloid structure (loss of OC and gain of A11 immunoreactivity) and dispersion of the acrosomal shroud.

FIG 5.

Examination of sperm acrosomal amyloid during capacitation and AR. IIF analysis was carried out with OC and A11 antibodies (red fluorescence) to examine acrosomal amyloid after incubation of cauda epididymal spermatozoa under capacitating conditions at 0 and 90 min and following induction of the AR by the addition of progesterone. Normal RS served as a control antiserum. Acrosomal integrity was determined by costaining with FITC-PNA (green fluorescence). Phase-contrast and epifluorescence images were merged informatically. Scale bars, 10 μm.

To examine further the effect of pH on the dispersion of the acrosome, in particular, the AM, an in vitro assay was carried out in which isolated cauda sperm AM were incubated at pH 3 or 7 at 37°C for various times and a dot blot analysis was carried out that allowed us to retain all of the forms of amyloid, including those that might be solubilized during the time course. As expected, incubation at pH 3 kept the AM relatively stable, with strong OC and no A11 immunoreactivity detected throughout the 60-min time course (Fig. 6A). However, following incubation at pH 7, there was a loss of OC from the AM and a profound increase in the A11 immunoreactivity with progressively more A11 immunoreactivity detected after 5 and 60 min (Fig. 6A). Staining of the blots with colloidal gold showed that the change in OC and A11 immunoreactivity was not associated with a change in the total amount of AM protein. FITC-PNA staining of the same populations of AM used for dot blot analysis showed that the majority of the AMs remained intact after 60 min of incubation at pH 3, as evidenced by the appearance of a crescent shape (Fig. 6B, top left panel). However, a small population showed a broadening of the crescent shape and the appearance of a longitudinal fissure that ran midline through the AM, suggesting the beginning of dispersion and the site where the AM separated into two layers (Fig. 6B arrow, top right panel). This longitudinal fissure observed in isolated AM may represent the split that occurs in the acrosome during the AR in vivo with the top layer of AM and its associated outer acrosomal membrane lifting off as the acrosomal shroud and the bottom layer of AM remaining associated with the inner acrosomal membrane on the sperm head (63). In contrast to AM kept at pH 3, after 60 min at pH 7, the AM was in various states of dispersion. Some AM only partially retained their crescent shape, with the remainder unraveling into a loose matrix; while other AM were more completely dispersed into two separate layers of loose matrix (Fig. 6B, lower panels). Our observation that the loss of OC and gain of A11 immunoreactivity correlated with the dispersion of the AM structure suggested that the reversal of amyloids contributed to AM dispersion. We cannot rule out, however, the possibility that the appearance of the A11-positive immature forms of amyloid represents an existing population of amyloid that was exposed during AM dispersion.

FIG 6.

A pH-dependent dispersion of the AM is associated with amyloid reversal. (A) Total AM were incubated for 0, 5, or 60 min at 37°C in 20 mM SA at pH 3 or 7. At each time point, a sample was removed for FITC-PNA staining while the remaining material (5 × 106 AM) was spotted onto nitrocellulose membrane for dot blot analysis with OC and A11 antibodies (Ab). Buffer only served as a negative control. Colloidal gold staining of the dot blots was performed to confirm the presence of protein in each spot (Stain). (B) AM integrity after incubation at pH 3 or 7 was determined by staining with FITC-PNA. The arrow shows a longitudinal fissure that was observed in some AM that were beginning to disperse. Scale bars, 2.5 μm.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that the sperm acrosome, including the AM, plays an important role in fertilization (64). Over the past several years, the general concept of how the AR occurs has evolved to the current acrosomal exocytosis model (65). This model proposes that there are several transition states, with outer acrosomal and plasma membrane vesiculation allowing progressive exposure of the AM and its ultimately becoming an extracellular matrix on the sperm head that interacts with the oocyte. Throughout the AR, the AM provides an infrastructure for the progressive release of AM-associated proteins and participates in a series of transitory sperm-zona pellucida interactions (65). In support of this model, studies show that the AM seems to be intimately associated with both the outer and inner acrosomal membranes since AM material has been detected in the acrosomal shroud that detaches from the spermatozoa and associated with the inner acrosomal membrane remaining on the acrosome-reacted spermatozoa (63). The acrosomal shroud/AM is proposed to hold the sperm head to the zona pellucida surface until the spermatozoon begins zona penetration, while the inner acrosomal membrane/AM may participate in a second binding event (38, 66). While the molecular details still need to be elucidated, throughout this process, the AM, or at least a part of it, remains, suggesting an unusual stability that is functionally important.

The studies presented herein add another dimension to the AR model by showing that amyloids are present in the mouse sperm AM and contribute to the formation of an SDS- and formic-acid-resistant core. We propose that this highly ordered amyloid infrastructure is the mechanism responsible for the well-described stability of the sperm AM, as well as the sequential release of AM-associated proteins during the AR. Amyloids are fibrillar structures formed by the assembly of proteins into intermolecularly hydrogen-bonded β-sheets. Although amyloids are still primarily recognized in mammals as being pathological entities, growing evidence suggests that amyloids may perform biological functions in many different cell types (15). Indeed, because amyloidogenic proteins are diverse with no common sequence, it is thought that amyloid represents an ancient fold that likely can be adopted by many proteins (67). Of the functional amyloids identified to date in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes, there seems to be a common trend, with many of these amyloids functioning as scaffold structures similar to the AM amyloid described herein (15, 68). In the sperm acrosome, the unusual stability of the amyloid fold would allow the AM scaffold to persist despite being exposed to a microenvironment that is rich in proteases and hydrolases.

The progressive dispersion of proteins from the sperm AM during the AR has been proposed to be analogous to piecemeal degranulation in neuroendocrine cells, where the regulated secretory granules can modulate the release of their contents (65, 69). How this occurs is not known, but it is intriguing that several peptide hormones are packaged as amyloids in regulated secretory granules in the pituitary gland (13). An in vitro amyloid release assay showed that some of these hormone amyloids could release monomers upon dilution (13). While a role for amyloid in piecemeal degranulation has yet to be determined, it is possible that the regulated release of AM-associated proteins during the AR is due to the reversal of the highly ordered amyloid structure into less-ordered amyloids. The unraveling of the amyloid could sequentially expose different populations of associated proteins that function during fertilization. Thus, a mechanism common to the sperm AM, secretory granules, and perhaps other organelles that involves amyloid disassembly for a controlled release of proteins may exist. Indeed, a proteomic comparison of mouse sperm AM with lysosome-related organelles showed highest overlap with proteins present in the secretory granules and melanosomes (16).

While the precise stimulus for the initiation of the AR is unclear, changes in acrosomal pH are integral to the process. Within the sperm acrosome, the stability of the AM is pH dependent (1). In the current AR model, the acidic (pH 3 to 4) intra-acrosomal pH is thought to keep resident proteases in an inactive state until capacitation and the AR, when the acrosomal pH begins to alkalinize, activating proteases, which allows the release of proteins and dispersion of the AM (37). Our studies examining the effect of pH on isolated AM, as well as during the progesterone-induced sperm AR, show a role for an increase in pH in the dispersion of the AM amyloid. The isolated AM amyloid was stable at pH 3 but quickly became destabilized and began to disperse at pH 7. The pH-dependent dispersion of the AM, however, correlated with a change in the amyloid structure with intact AM rich in mature forms of amyloid transitioning into dispersed matrix material rich in immature forms of amyloid. Similarly, during the progesterone-induced AR at pH 7, the OC-positive acrosomal shroud rapidly dispersed. Although we were unable to detect A11 immunoreactivity in the dispersing shrouds, this may have been due to the presence of resident proteases and disaggregases that rapidly transitioned the amyloid to monomeric forms and that were less abundant or less active in the isolated AM amyloid. Therefore, the mechanism responsible for the organized disassembly or reversal of amyloids within the AM may be pH dependent and this disassembly of amyloid is part of the AM dispersion process. Although a mammalian homolog has not yet been identified, in yeast, the AAA+ ATPase Hsp104 functions as a disaggregase, disassembling amyloid fibrils first into oligomers and then into monomeric forms (70, 71). Alternatively, the AM amyloid disassembly could result from a change in the equilibrium of existing monomer and amyloid. Indeed, in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease, the disaggregation of Aβ deposits has been suggested to be driven by proteolysis of Aβ monomers where the depletion of monomers below critical concentrations causes existing amyloid fibrils to disassemble, therefore releasing monomer to repopulate the decreasing monomer population (72, 73).

In previous studies, we showed that isolated mouse sperm AM contained a diverse group of proteins, including proteases, chaperones, hydrolases, transporters, enzyme modulators, cytoskeletal proteins, and others, suggesting a complex functional structure (16). In the present study, extraction with 1% SDS solubilized the majority of the AM proteins. The composition of the remaining AM amyloid core revealed a unique group of proteins most of which are known to form amyloid or to contain regions that are predicted to form amyloid, including the zona pellucida binding proteins ZP3R and ZAN, suggesting a functional role for the core in zona interactions.

Whether the AM core is formed by one or several amyloidogenic proteins is not clear. However, several amyloidogenic proteins have been shown to cross seed and form heterologous amyloid structures (74, 75). Therefore, it is possible that the AM amyloid core is composed of several proteins that together create the amyloid infrastructure with which other AM proteins then associate. How these interactions occur is not known, but it may involve the amyloidogenic domains in the individual proteins conferring an ability to interact with the amyloid core. Alternatively, LC-MS/MS showed that cytoskeletal proteins are present in the core. These structural proteins may serve as linkers or intermediaries linking nonamyloidogenic proteins to the amyloid-containing core. Indeed, the hinge within the plakin domain of desmoplakin has been shown to have unrestricted mobility and thus may provide important flexibility for protein interactions during fertilization (76). Similarly, the TG repeat sequences in Phxr5 would confer flexibility.

From these studies, we propose that functional amyloids are present within the mouse sperm AM and contribute to the formation of a stable core infrastructure that plays roles in the sequential dispersion of proteins during the AR, as well as in downstream interactions with the zona pellucida. The disassembly of the amyloid may also facilitate transitory interactions between the sperm AM and the zona, as the reversal of amyloid could expose protein for proteolysis, resulting in detachment from that site and allowing forward progression of the sperm through the zona pellucida. Finally, it is possible that it is the sperm AM amyloid structure itself that functions as a nonenzymatic “lysin,” allowing zona penetration similar to that which occurs in sea urchins and ascidians (77).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH RO1HD056182, the CH Foundation (G.A.C.) and the Philippe Foundation (B.G.).

The content of this report is solely our responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Sandra Whelly for her helpful discussions, Daniel Hardy for the gift of ZAN antibody, and Henry Akinbi for the gift of LYZ2 antibody. We also thank Kerry L. Fuson and R. Bryan Sutton for assistance with the X-ray diffraction analysis and Mary Catherine Hastert, TTU, for her assistance with the TEM studies. We thank Lauren R. DeVine, Tatiana Boronina, and Robert N. Cole from the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine for the LC-MS/MS analyses.

B.G. and G.A.C. designed the research and analyzed the data, B.G. and N.E. performed the research, and B.G. and G.A.C. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 May 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00073-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buffone MG, Foster JA, Gerton GL. 2008. The role of the acrosomal matrix in fertilization. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 52:511–522. 10.1387/ijdb.072532mb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy DM, Oda MN, Friend DS, Huang TT. 1991. A mechanism for differential release of acrosomal enzymes during the acrosome reaction. Biochem. J. 275(Pt 3):759–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim K-S, Gerton GL. 2003. Differential release of soluble and matrix components: evidence for intermediate states of secretion during spontaneous acrosomal exocytosis in mouse sperm. Dev. Biol. 264:141–152. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Florman HM, Storey BT. 1982. Mouse gamete interactions: the zona pellucida is the site of the acrosome reaction leading to fertilization in vitro. Dev. Biol. 91:121–130. 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90015-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storey BT, Lee MA, Muller C, Ward CR, Wirtshafter DG. 1984. Binding of mouse spermatozoa to the zonae pellucidae of mouse eggs in cumulus: evidence that the acrosomes remain substantially intact. Biol. Reprod. 31:1119–1128. 10.1095/biolreprod31.5.1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin M, Fujiwara E, Kakiuchi Y, Okabe M, Satouh Y, Baba SA, Chiba K, Hirohashi N. 2011. Most fertilizing mouse spermatozoa begin their acrosome reaction before contact with the zona pellucida during in vitro fertilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:4892–4896. 10.1073/pnas.1018202108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirohashi N, Gerton GL, Buffone MG. 2011. Video imaging of the sperm acrosome reaction during in vitro fertilization. Commun. Integr. Biol. 4:471–476. 10.4161/cib.4.2.15636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KS, Cha MC, Gerton GL. 2001. Mouse sperm protein sp56 is a component of the acrosomal matrix. Biol. Reprod. 64:36–43. 10.1095/biolreprod64.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleil JD, Wassarman PM. 1990. Identification of a ZP3-binding protein on acrosome-intact mouse sperm by photoaffinity crosslinking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:5563–5567. 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hickox JR, Bi M, Hardy DM. 2001. Heterogeneous processing and zona pellucida binding activity of pig zonadhesin. J. Biol. Chem. 276:41502–41509. 10.1074/jbc.M106795200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson GE, Winfrey VP, Bi M, Hardy DM, NagDas SK. 2004. Zonadhesin assembly into the hamster sperm acrosomal matrix occurs by distinct targeting strategies during spermiogenesis and maturation in the epididymis. Biol. Reprod. 71:1128–1134. 10.1095/biolreprod.104.029975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler DM, Koulov AV, Alory-Jost C, Marks MS, Balch WE, Kelly JW. 2006. Functional amyloid formation within mammalian tissue. PLoS Biol. 4:e6. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maji SK, Perrin MH, Sawaya MR, Jessberger S, Vadodaria K, Rissman RA, Singru PS, Nilsson KPR, Simon R, Schubert D, Eisenberg D, Rivier J, Sawchenko P, Vale W, Riek R. 2009. Functional amyloids as natural storage of peptide hormones in pituitary secretory granules. Science 325:328–332. 10.1126/science.1173155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whelly S, Johnson S, Powell J, Borchardt C, Hastert MC, Cornwall GA. 2012. Nonpathological extracellular amyloid is present during normal epididymal sperm maturation. PLoS One 7:e36394. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fowler DM, Koulov AV, Balch WE, Kelly JW. 2007. Functional amyloid–from bacteria to humans. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32:217–224. 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyonnet B, Zabet-Moghaddam M, Sanfrancisco S, Cornwall GA. 2012. Isolation and proteomic characterization of the mouse sperm acrosomal matrix. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11:758–774. 10.1074/mcp.M112.020339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White D, Weerachatyanukul W, Gadella B, Kamolvarin N, Attar M, Tanphaichitr N. 2000. Role of sperm sulfogalactosylglycerolipid in mouse sperm-zona pellucida binding. Biol. Reprod. 63:147–155. 10.1095/biolreprod63.1.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kayed R, Head E, Sarsoza F, Saing T, Cotman CW, Necula M, Margol L, Wu J, Breydo L, Thompson JL, Rasool S, Gurlo T, Butler P, Glabe CG. 2007. Fibril specific, conformation dependent antibodies recognize a generic epitope common to amyloid fibrils and fibrillar oligomers that is absent in prefibrillar oligomers. Mol. Neurodegener. 2:18. 10.1186/1750-1326-2-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. 2003. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 300:486–489. 10.1126/science.1079469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pirttilä TJ, Lukasiuk K, Håkansson K, Grubb A, Abrahamson M, Pitkänen A. 2005. Cystatin C modulates neurodegeneration and neurogenesis following status epilepticus in mouse. Neurobiol. Dis. 20:241–253. 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cornwall GA, Hann SR. 1995. Transient appearance of CRES protein during spermatogenesis and caput epididymal sperm maturation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 41:37–46. 10.1002/mrd.1080410107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tardif S, Wilson MD, Wagner R, Hunt P, Gertsenstein M, Nagy A, Lobe C, Koop BF, Hardy DM. 2010. Zonadhesin is essential for species specificity of sperm adhesion to the egg zona pellucida. J. Biol. Chem. 285:24863–24870. 10.1074/jbc.M110.123125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685. 10.1038/227680a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsudaira P. 1987. Sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 262:10035–10038 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chevallet M, Luche S, Rabilloud T. 2006. Silver staining of proteins in polyacrylamide gels. Nat. Protoc. 1:1852–1858. 10.1038/nprot.2006.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. 1996. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68:850–858. 10.1021/ac950914h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiśniewski JR, Zougman A, Nagaraj N, Mann M. 2009. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 6:359–362. 10.1038/nmeth.1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luque-Garcia JL, Zhou G, Spellman DS, Sun T-T, Neubert TA. 2008. Analysis of electroblotted proteins by mass spectrometry: protein identification after Western blotting. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7:308–314. 10.1074/mcp.M700415-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chambers MC, Maclean B, Burke R, Amodei D, Ruderman DL, Neumann S, Gatto L, Fischer B, Pratt B, Egertson J, Hoff K, Kessner D, Tasman N, Shulman N, Frewen B, Baker TA, Brusniak M-Y, Paulse C, Creasy D, Flashner L, Kani K, Moulding C, Seymour SL, Nuwaysir LM, Lefebvre B, Kuhlmann F, Roark J, Rainer P, Detlev S, Hemenway T, Hühmer A, Langridge J, Connolly B, Chadick T, Holly K, Eckels J, Deutsch EW, Moritz RL, Katz JE, Agus DB, MacCoss M, Tabb DL, Mallick P. 2012. A cross-platform toolkit for mass spectrometry and proteomics. Nat. Biotechnol. 30:918–920. 10.1038/nbt.2377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craig R, Beavis RC. 2004. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics 20:1466–1467. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maurer-Stroh S, Debulpaep M, Kuemmerer N, Lopez de la Paz M, Martins IC, Reumers J, Morris KL, Copland A, Serpell L, Serrano L, Schymkowitz JWH, Rousseau F. 2010. Exploring the sequence determinants of amyloid structure using position-specific scoring matrices. Nat. Methods 7:237–242. 10.1038/nmeth.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vizcaíno JA, Côté RG, Csordas A, Dianes JA, Fabregat A, Foster JM, Griss J, Alpi E, Birim M, Contell J, O'Kelly G, Schoenegger A, Ovelleiro D, Perez-Riverol Y, Reisinger F, Ríos D, Wang R, Hermjakob H. 2013. The PRoteomics IDEntifications (PRIDE) database and associated tools: status in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:D1063–9. 10.1093/nar/gks1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glabe CG. 2004. Conformation-dependent antibodies target diseases of protein misfolding. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:542–547. 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cross NL, Meizel S. 1989. Methods for evaluating the acrosomal status of mammalian sperm. Biol. Reprod. 41:635–641. 10.1095/biolreprod41.4.635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westermark GT, Johnson KH, Westermark P. 1999. Staining methods for identification of amyloid in tissue. Methods Enzymol. 309:3–25. 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)09003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makin OS, Serpell LC. 2005. Structures for amyloid fibrils. FEBS J. 272:5950–5961. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang TT, Hardy D, Yanagimachi H, Teuscher C, Tung K, Wild G, Yanagimachi R. 1985. pH and protease control of acrosomal content stasis and release during the guinea pig sperm acrosome reaction. Biol. Reprod. 32:451–462. 10.1095/biolreprod32.2.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanagimachi R, Phillips DM. 1984. The status of acrosomal caps of hamster spermatozoa immediately before fertilization in vivo. Gamete Res. 9:1–19. 10.1002/mrd.1120090102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.VandeVoort CA, Yudin AI, Overstreet JW. 1997. Interaction of acrosome-reacted macaque sperm with the macaque zona pellucida. Biol. Reprod. 56:1307–1316. 10.1095/biolreprod56.5.1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morozova-Roche LA, Zurdo J, Spencer A, Noppe W, Receveur V, Archer DB, Joniau M, Dobson CM. 2000. Amyloid fibril formation and seeding by wild-type human lysozyme and its disease-related mutational variants. J. Struct. Biol. 130:339–351. 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ekiel I, Abrahamson M. 1996. Folding-related dimerization of human cystatin C. J. Biol. Chem. 271:1314–1321. 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Horsten HH, Johnson SS, SanFrancisco SK, Hastert MC, Whelly SM, Cornwall GA. 2007. Oligomerization and transglutaminase cross-linking of the cystatin CRES in the mouse epididymal lumen: potential mechanism of extracellular quality control. J. Biol. Chem. 282:32912–32923. 10.1074/jbc.M703956200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holm NK, Jespersen SK, Thomassen LV, Wolff TY, Sehgal P, Thomsen LA, Christiansen G, Andersen CB, Knudsen AD, Otzen DE. 2007. Aggregation and fibrillation of bovine serum albumin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1774:1128–1138. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang YT, Liu HN, Wang WJ, Lee DD, Tsai SF. 2004. A study of cytokeratin profiles in localized cutaneous amyloids. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 296:83–88. 10.1007/s00403-004-0474-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Damaschun G, Damaschun H, Fabian H, Gast K, Kröber R, Wieske M, Zirwer D. 2000. Conversion of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase into amyloid-like structure. Proteins 39:204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalhor HR, Shahin FV, Fouani MH, Hosseinkhani H. 2011. Self-assembly of tissue transglutaminase into amyloid-like fibrils using physiological concentration of Ca2+. Langmuir 27:10776–10784. 10.1021/la200740h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu Q, Trotter J, Zhang J, Peters MM, Cheng H, Bao J, Han X, Weeber EJ, Bu G. 2010. Neuronal LRP1 knockout in adult mice leads to impaired brain lipid metabolism and progressive, age-dependent synapse loss and neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 30:17068–17078. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4067-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilhelmus MMM, Bol JGJM, Van Haastert ES, Rozemuller AJM, Bu G, Drukarch B, Hoozemans JJM. 2011. Apolipoprotein E and LRP1 increase early in Parkinson's disease pathogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 179:2152–2156. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brettschneider J, Lehmensiek V, Mogel H, Pfeifle M, Dorst J, Hendrich C, Ludolph AC, Tumani H. 2010. Proteome analysis reveals candidate markers of disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Neurosci. Lett. 468:23–27. 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.10.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kley RA, Maerkens A, Leber Y, Theis V, Schreiner A, van der Ven PFM, Uszkoreit J, Stephan C, Eulitz S, Euler N, Kirschner J, Müller K, Meyer HE, Tegenthoff M, Fürst DO, Vorgerd M, Müller T, Marcus K. 2013. A combined laser microdissection and mass spectrometry approach reveals new disease relevant proteins accumulating in aggregates of filaminopathy patients. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12:215–227. 10.1074/mcp.M112.023176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vural H, Sirin B, Yilmaz N, Eren I, Delibas N. 2009. The role of arginine-nitric oxide pathway in patients with Alzheimer disease. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 129:58–64. 10.1007/s12011-008-8291-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng A, Le T, Palacios M, Bookbinder LH, Wassarman PM, Suzuki F, Bleil JD. 1994. Sperm-egg recognition in the mouse: characterization of sp56, a sperm protein having specific affinity for ZP3. J. Cell Biol. 125:867–878. 10.1083/jcb.125.4.867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bi M, Hickox JR, Winfrey VP, Olson GE, Hardy DM. 2003. Processing, localization and binding activity of zonadhesin suggest a function in sperm adhesion to the zona pellucida during exocytosis of the acrosome. Biochem. J. 375:477–488. 10.1042/BJ20030753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baba T, Niida Y, Michikawa Y, Kashiwabara S, Kodaira K, Takenaka M, Kohno N, Gerton GL, Arai Y. 1994. An acrosomal protein, sp32, in mammalian sperm is a binding protein specific for two proacrosins and an acrosin intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 269:10133–10140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolkowicz MJ, Shetty J, Westbrook A, Klotz K, Jayes F, Mandal A, Flickinger CJ, Herr JC. 2003. Equatorial segment protein defines a discrete acrosomal subcompartment persisting throughout acrosomal biogenesis. Biol. Reprod. 69:735–745. 10.1095/biolreprod.103.016675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujihara Y, Murakami M, Inoue N, Satouh Y, Kaseda K, Ikawa M, Okabe M. 2010. Sperm equatorial segment protein 1, SPESP1, is required for fully fertile sperm in mouse. J. Cell Sci. 123:1531–1536. 10.1242/jcs.067363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mitra K, Rangaraj N, Shivaji S. 2005. Novelty of the pyruvate metabolic enzyme dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase in spermatozoa: correlation of its localization, tyrosine phosphorylation, and activity during sperm capacitation. J. Biol. Chem. 280:25743–25753. 10.1074/jbc.M500310200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohmura K, Kohno N, Kobayashi Y, Yamagata K, Sato S, Kashiwabara S, Baba T. 1999. A homologue of pancreatic trypsin is localized in the acrosome of mammalian sperm and is released during acrosome reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 274:29426–29432. 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamaguchi R, Fujihara Y, Ikawa M, Okabe M. 2012. Mice expressing aberrant sperm-specific protein PMIS2 produce normal-looking but fertilization-incompetent spermatozoa. Mol. Biol. Cell 23:2671–2679. 10.1091/mbc.E11-12-1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roldan ER, Murase T, Shi QX. 1994. Exocytosis in spermatozoa in response to progesterone and zona pellucida. Science 266:1578–1581. 10.1126/science.7985030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toshimori K. 2009. Dynamics of the mammalian sperm head. Springer, New York, NY: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Okabe M. 2013. The cell biology of mammalian fertilization. Development 140:4471–4479. 10.1242/dev.090613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Toshimori K. 2011. Dynamics of the mammalian sperm membrane modification leading to fertilization: a cytological study. J. Electron Microsc. (Tokyo) 60(Suppl 1):S31–S42. 10.1093/jmicro/dfr036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yanagimachi R. 1994. Mammalian fertilization. Physiol. Reprod. 1:189–317 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim K-S, Foster JA, Kvasnicka KW, Gerton GL. 2011. Transitional states of acrosomal exocytosis and proteolytic processing of the acrosomal matrix in guinea pig sperm. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 78:930–941. 10.1002/mrd.21387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang TT, Yanagimachi R. 1985. Inner acrosomal membrane of mammalian spermatozoa: its properties and possible functions in fertilization. Am. J. Anat. 174:249–268. 10.1002/aja.1001740307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chernoff YO. 2004. Amyloidogenic domains, prions and structural inheritance: rudiments of early life or recent acquisition? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 8:665–671. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chapman MR, Robinson LS, Pinkner JS, Roth R, Heuser J, Hammar M, Normark S, Hultgren SJ. 2002. Role of Escherichia coli curli operons in directing amyloid fiber formation. Science 295:851–855. 10.1126/science.1067484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crivellato E, Nico B, Bertelli E, Nussdorfer GG, Ribatti D. 2006. Dense-core granules in neuroendocrine cells and neurons release their secretory constituents by piecemeal degranulation (review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 18:1037–1046. 10.3892/ijmm.18.6.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shorter J, Lindquist S. 2004. Hsp104 catalyzes formation and elimination of self-replicating Sup35 prion conformers. Science 304:1793–1797. 10.1126/science.1098007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shorter J, Lindquist S. 2006. Destruction or potentiation of different prions catalyzed by similar Hsp104 remodeling activities. Mol. Cell 23:425–438. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leissring MA, Farris W, Chang AY, Walsh DM, Wu X, Sun X, Frosch MP, Selkoe DJ. 2003. Enhanced proteolysis of beta-amyloid in APP transgenic mice prevents plaque formation, secondary pathology, and premature death. Neuron 40:1087–1093. 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00787-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Powers ET, Powers DL. 2006. The kinetics of nucleated polymerizations at high concentrations: amyloid fibril formation near and above the “supercritical concentration.” Biophys. J. 91:122–132. 10.1529/biophysj.105.073767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Giasson BI, Lee VM-Y, Trojanowski JQ. 2003. Interactions of amyloidogenic proteins. Neuromolecular Med. 4:49–58. 10.1385/NMM:4:1-2:49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hartman K, Brender JR, Monde K, Ono A, Evans ML, Popovych N, Chapman MR, Ramamoorthy A. 2013. Bacterial curli protein promotes the conversion of PAP248-286 into the amyloid SEVI: cross-seeding of dissimilar amyloid sequences. PeerJ 1:e5. 10.7717/peerj.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Al-Jassar C, Bernadó P, Chidgey M, Overduin M. 2013. Hinged plakin domains provide specialized degrees of articulation in envoplakin, periplakin and desmoplakin. PLoS One 8:e69767. 10.1371/journal.pone.0069767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lewis CA, Talbot CF, Vacquier VD. 1982. A protein from abalone sperm dissolves the egg vitelline layer by a nonenzymatic mechanism. Dev. Biol. 92:227–239. 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90167-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Krishna A, Spanel-Borowski K. 1990. Albumin localization in the testis of adult golden hamsters by use of immunohistochemistry. Andrologia 22:122–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sleight SB, Miranda PV, Plaskett N-W, Maier B, Lysiak J, Scrable H, Herr JC, Visconti PE. 2005. Isolation and proteomic analysis of mouse sperm detergent-resistant membrane fractions: evidence for dissociation of lipid rafts during capacitation. Biol. Reprod. 73:721–729. 10.1095/biolreprod.105.041533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kierszenbaum AL, Rivkin E, Tres LL. 2003. Acroplaxome, an F-actin-keratin-containing plate, anchors the acrosome to the nucleus during shaping of the spermatid head. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:4628–4640. 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Danshina PV, Geyer CB, Dai Q, Goulding EH, Willis WD, Kitto GB, McCarrey JR, Eddy EM, O'Brien DA. 2010. Phosphoglycerate kinase 2 (PGK2) is essential for sperm function and male fertility in mice. Biol. Reprod. 82:136–145. 10.1095/biolreprod.109.079699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hitomi K, Horio Y, Ikura K, Yamanishi K, Maki M. 2001. Analysis of epidermal-type transglutaminase (TGase 3) expression in mouse tissues and cell lines. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 33:491–498. 10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00033-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsuruta JK, O'Brien DA, Griswold MD. 1993. Sertoli cell and germ cell cystatin C: stage-dependent expression of two distinct messenger ribonucleic acid transcripts in rat testes. Biol. Reprod. 49:1045–1054. 10.1095/biolreprod49.5.1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Syntin P, Cornwall GA. 1999. Immunolocalization of CRES (cystatin-related epididymal spermatogenic) protein in the acrosomes of mouse spermatozoa. Biol. Reprod. 60:1542–1552. 10.1095/biolreprod60.6.1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.