Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with reduced hepatic endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activation status via S1177 phosphorylation (p-eNOS) and is prevented by daily voluntary wheel running (VWR). Hyperphagic Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats, an established model of obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D) and NAFLD, and normophagic controls [Long-Evans Tokushima Otsuka (LETO)] were studied at 8, 20, and 40 wk of age. Basal hepatic eNOS phosphorylation (p-eNOS/eNOS) was similar between LETO and OLETFs with early hepatic steatosis (8 wk of age) and advanced steatosis, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperglycemia (20 wk of age). In contrast, hepatic p-eNOS/eNOS was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in OLETF rats with T2D advancement and the transition to more advanced NAFLD with inflammation and fibrosis [increased tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), CD68, and CD163 mRNA expression; 40 wk of age]. Reduced hepatic eNOS activation status in 40-wk OLETF rats was significantly correlated with reduced p-Akt/Akt (r = 0.73, P < 0.05), reduced serum insulin (r = 0.59, P < 0.05), and elevated serum glucose (r = −0.78, P < 0.05), suggesting a link between impaired glycemic control and altered hepatic nitric oxide metabolism. VWR by OLETF rats, in conjunction with NAFLD and T2D prevention, normalized p-eNOS/eNOS and p-Akt/Akt to LETO levels. Basal activation of hepatic eNOS and Akt are maintained until advanced NAFLD and T2D development in obese OLETF rats. The prevention of this reduction by VWR may result from maintained insulin sensitivity and glycemic control.

Keywords: OLETF, type 2 diabetes, eNOS, hepatic, Akt, exercise

a combination of sedentary lifestyles and overnutrition has led to an epidemic of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in Western societies. Central to this epidemic is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is estimated to be present in 75–100% of obese and morbidly obese individuals (2). NAFLD comprises a spectrum of liver pathologies from simple steatosis [hepatic triglyceride (TAG) accumulation], to more severe nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and eventually cirrhosis (reviewed in Ref. 34). Importantly, NAFLD is an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease (6, 43, 48) and overall mortality (27, 28). Lifestyle modification, including exercise training, is the standard of care for NAFLD patients (31, 38). However, the mechanisms by which exercise improves NAFLD outcomes remain an active area of investigation.

Evidence indicates that impaired hepatic endothelial cell function is present in experimental models of NAFLD (29, 30, 44). Specifically, dysregulated hepatic endothelial cell nitric oxide (NO) production by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) exacerbates multiple features of progressing NAFLD severity, including steatosis, fibrosis, inflammation, hepatic insulin resistance, and portal hypertension (24, 29, 30, 37, 44, 47). Although the propensity for exercise training to improve systemic endothelial function is well appreciated (13), no investigation to date has examined this phenomenon in the context of the liver. Given the capability for exercise to improve hepatic insulin sensitivity (36), one possibility is that exercise enhances Akt activation, which directly phosphorylates and activates hepatic eNOS (25).

Our group has previously described the natural history of NAFLD in the spontaneously hyperphagic Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rat (33). This rat gradually develops obesity, T2D, and NAFLD throughout the lifespan in a pattern similar to human disease. Importantly, we have demonstrated that unrestricted voluntary wheel running (VWR) completely prevents the disease phenotype (36). Interestingly, VWR also prevents or reverses defects in endothelial function (1, 3, 21, 22). Thus the OLETF rat provides an excellent model with which to assess the effects of NAFLD and physical activity on the hepatic vasculature.

Herein we assessed the basal activation status of eNOS via S1177 phosphorylation (p-eNOS) and of Akt via S473 phosphorylation (p-Akt) in the livers from OLETF and normophagic control [Long-Evans Tokushima Otsuka (LETO)] rats at three pathologically significant ages: 8 wk (early steatosis), 20 wk [advanced steatosis and insulin resistance (hyperglycemic and hyperinsulinemic)], and 40 wk (overt T2D and NAFLD transitioning to NASH), as our laboratory has previously described (33). To our knowledge, this is the first account of hepatic eNOS content and activation status 1) throughout the progression of NAFLD and T2D in the OLETF rat; and 2) in the context of daily physical exercise. We hypothesized that both hepatic eNOS and Akt activation status would be reduced in sedentary, insulin-resistant, 20-wk old OLETF rats, and that this reduction would be prevented by VWR. Finally, to gain insight into the regulation of hepatic eNOS, we examined select molecular modulators of eNOS phosphorylation and NO production, as well as its association with various metabolic characteristics.

METHODS

Animal protocol.

Male OLETF and LETO rats were obtained from Tokushima Research Institute, Otsuka Pharmaceutical (Tokushima, Japan) at 4 wk of age. LETO rats were maintained in sedentary conditions (LETO-sed), and OLETF rats were randomly divided into either sedentary (OLETF-sed) or VWR groups (OLETF-ex). All rats received ad libitum access to tap water and standard rodent chow (Formulab 5008, Purina Mills, St. Louis, MO) throughout the study. OLETF-ex rats were given access to running wheels, which were monitored and recorded daily with Sigma Sport BC 606 bicycle computers (Cherry Creek Cyclery, Foster Falls, VA), beginning at 4 wk of age throughout the remainder of the protocol. Animals were individually caged in a temperature-controlled facility (21°C) with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Body weight and food consumption were recorded weekly. At 0800 on the day of death, animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (100 mg/kg) following a 5-h fast. Blood was collected from the left ventricle for analysis, after which the animal was exsanguinated and tissues were collected. The liver was rapidly excised and immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for later processing. OLETF-sed and LETO-sed rats were killed at 8, 20, and 40 wk of age, and OLETF-ex rats were killed at 40 wk of age following a 53-h running wheel lock. This length of wheel lock was chosen to prevent any acute exercise effect while still maintaining exercise adaptations (3, 7). All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri.

Fat pad collection, body composition, and serum assays.

Before euthanasia, whole body composition was assessed in 40-wk animals with a dual X-ray absorptiometry machine calibrated for use with rats. Retroperitoneal, omental, and epidydimal fat pads were removed and weighed. Serum glucose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), insulin (Linco Research, St. Charles, MO), TAG (Sigma), and free fatty acids (FFA) (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) were assessed using commercially available kits per the manufacturers' instructions. Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) was measured in 40-wk-old animals, as previously reported (17, 32). Hepatic TAG content was measured as previously described by our group (32).

Western blots.

Western blots and densometric analysis (Image Lab Beta 3, Bio-Rad Laboratories) were performed in whole liver homogenates for eNOS (610297, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), p-eNOS (612393, BD Biosciences), Akt (no. 9272, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), p-Akt (no. 9271, Cell Signaling), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; no. ab5694, AbCam, Cambridge, MA), α-adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK; no. 2603, Cell Signaling), α-AMPK T172 phosphorylation specific (no. 2531, Cell Signaling), caveolin-1 (Cav-1; no. D46G3, BD Biosciences), and guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase-1 (GTPCH-1; no. Ab61858, AbCam). Amido black stain (0.1%; Sigma) was used to quantify total protein to account for any variation in protein loading and transfer.

Hepatic nitrite + nitrate.

Total hepatic NO content (NOX) was assessed using a commercially available kit (no. 780001, Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) that measures total nitrite and nitrate, stable derivatives of NO.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

RNA was isolated from the frozen livers of 40-wk OLETF and LETO rats via a commercially available kit (RNeasy Mini Kit, no. 74104, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA purity was determined using a nanodrop spectophotomometer (Nanodrop 2000c, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), and cDNA was synthesized via reverse transcriptase. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed with the ABI 7500 Fast Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) using Fast Sybr Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Primer pairs were obtained from Sigma, and sequences are as follows: β-actin (forward: GCT CTC TTC CAG CCT TCC TT, reverse: CTT CTG CAT CCT GTC TAG CAA), inducible NOS (forward: GTT GCT GGA AAA GGA AGC AG, reverse: AAG TGA AAG CCA GCA GGA A), TNF-α (forward: ACT GAA CTT CGG GGT GAT CG, reverse: GCT TGG TGG TTT GCT ACG AC), CD68 (forward: TCA CAA AAA GGC TGC CCA CTC TT, reverse: TCG TAG GGC TTG CTG TGC TT), and CD163 (forward: TGT AGT TCA TCA TCT TCG TCC, reverse: CAC CTA CCA AGC GGA GTT GAC). Dissociation melt curves were analyzed to verify primer specificity. mRNA expression of endogenous β-actin was not different among groups and was used to calculate the expression levels of genes of interest using the 2−ΔΔCT method. All data are normalized to expression levels of LETO-sed.

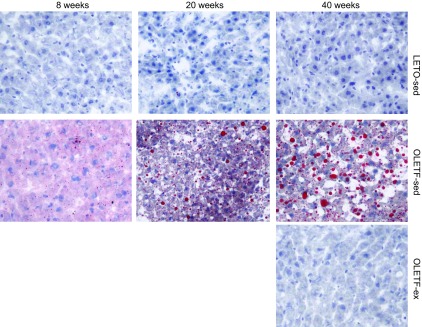

Liver histology.

Sections of liver were prepared and Oil-Red O staining for neutral lipid was performed, as previously described (32).

Statistics.

Four to eight animals per group were analyzed within each age, group, and treatment. Statistical analysis was performed via one-way ANOVA (R, version 2.15.1). OLETF-ex rats were only compared with 40-wk OLETF-sed and LETO-sed rats. When a significant main effect was observed (P < 0.05), a Fischer's least significant difference test was completed for post hoc comparisons. Pearson correlations were conducted to examine associations between measures of glycemic control and hepatic eNOS and Akt activation status. Data are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Animal characteristics.

Body composition, food consumption, serum, and liver characteristics of the animals are presented in Table 1. OLETF-sed rats had higher body weight, fat pad mass, serum glucose, and hepatic TAG accumulation than LETO-sed by 8 wk of age. At 20 wk, OLETF-sed rats were insulin resistant (hyperglycemic/hyperinsulinemic) with further hepatic TAG accumulation. This further progressed to overt T2D with pancreatic β-cell dysfunction by 40 wk as is apparent by the hyperglycemic/insulinopenic serum profile and the dramatically elevated HbA1c levels in the OLETF-sed animals. However, LETO-sed animals maintained serum glucose levels throughout the study, with elevations in serum insulin witnessed from 20 to 40 wk (Table 1). Serum insulin and glucose values were similar in the OLETF-ex rats compared with the lean, LETO-sed control animals at 40 wk of age. Consistent with the biochemical hepatic TAG data, Oil-Red O staining revealed early hepatic steatosis in 8-wk OLETF-sed rats and a progression to widespread macro- and micro-vesicular steatosis by 40 wk age (Fig. 1). No appreciable steatosis was apparent in livers from LETO-sed or OLETF-ex rats. Moreover, our laboratory had previously reported that 40-wk-old OLETF-sed rats display early evidence of a NASH phenotype, including perivenular fibrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, and elevated serum alanine aminotransferase levels (33). OLETF-ex animals ran an average daily distance that ranged from 12.3 ± 0.4 km/day at 9 wk of age to 3.5 ± 0.2 km/day at 40 wk. Importantly, this VWR regimen was sufficient to completely prevent obesity, T2D, and NAFLD in 40-wk OLETF rats.

Table 1.

Animal and metabolic characteristics

| LETO-sed |

OLETF-sed |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 wk old | 20 wk old | 40 wk old | 8 wk old | 20 wk old | 40 wk old | 40-wk-old OLETF-ex | |

| Body weight, g | 228.4 ± 6.3a | 500.4 ± 5.0b | 557.4 ± 17.3c | 288.5 ± 5.0a* | 644.3 ± 8.2b* | 693.7 ± 38.8b* | 555.8 ± 12.8‡ |

| Absolute food consumption, g/wk | 135.9 ± 1.9a | 159.5 ± 1.7b | 164.7 ± 5.6b | 183.0 ± 1.0a* | 221.3 ± 12.6b* | 320.8 ± 22.1c* | 230.8 ± 8.4†‡ |

| Relative food consumption, g·wk−1·g body wt−1 | 0.60 ± 0.02a | 0.36 ± 0.02b | 0.29 ± 0.01b | 0.63 ± 0.01a | 0.33 ± 0.01b | 0.44 ± 0.06b | 0.44 ± 0.01† |

| Body fat, % | No data | No data | 22.4 ± 1.3 | No data | No data | 30.0 ± 4.0* | 18.0 ± 1.4†‡ |

| Fat pad mass, g | 0.89 ± 0.1a | 12.2 ± 0.5b | 14.6 ± 1.2b | 3.5 ± 0.2a* | 52.0 ± 2.8b* | 55.7 ± 7.5b* | 14.18 ± 2.5‡ |

| Serum glucose, mg/dl | 204.4 ± 10.8a | 265.1 ± 6.9a | 261.3 ± 20.1a | 244.0 ± 14.4a | 391.7 ± 34.4b* | 665.9 ± 41.8c* | 312.8 ± 14.0‡ |

| Serum insulin, ng/ml | 6.1 ± 1.0a | 9.7 ± 0.5b | 10.7 ± 0.7b | 5.3 ± 1.2a | 14.0 ± 1.1b* | 5.0 ± 1.2a* | 11.6 ± 0.9‡ |

| HbA1C, % | No data | No data | 4.6 ± 0.04 | No data | No data | 9.4 ± 0.7* | 4.8 ± 0.3‡ |

| Serum TAG, mg/dl | 20.3 ± 2.6a | 42.2 ± 3.6a | 42.3 ± 3.1a | 36.2 ± 5.0a | 330.1 ± 29.7b* | 253.4 ± 32.8c* | 84.5 ± 10.5‡ |

| Serum FFA, μmol/l | 139.2 ± 30.7a | 242.9 ± 13.1b | 187.4 ± 22.0a,b | 176.6 ± 38.9a | 409.2 ± 24.0b* | 309.8 ± 56.6c* | 157.1 ± 20.3‡ |

| Liver TAG, nmol/g wet wt | 1.2 ± 0.2a | 2.8 ± 0.3a | 1.8 ± 0.4a | 2.4 ± 0.1a | 7.0 ± 1.3b* | 8.1 ± 1.5b* | 3.31 ± 0.4†‡ |

Values are means ± SE, n = 6–8 rats/group. HbA1C, glycosylated hemoglobin; TAG, triacylglycerol; FFA, free fatty acid; LETO-sed, sedentary Long-Evans Tokushima Otsuka rats; OLETF-sed, sedentary Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats; OLETF-ex, voluntary wheel running OLETF rats.

Significant changes between ages within an animal group (P < 0.05).

OLETF-sed different from LETO-sed at respective age (P < 0.05).

OLETF-ex different from 40-wk-old LETO-sed (P < 0.05).

OLETF-ex different from 40-wk-old OLETF-sed (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Representative Oil-Red O staining for neutral lipid staining in sedentary Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF-sed) and sedentary Long-Evans Tokushima Otsuka (LETO-sed) rats at 8, 20, and 40 wk of age and voluntary wheel running (VWR) OLETF (OLETF-ex) rats at 40 wk of age.

Basal hepatic p-eNOS and p-Akt are maintained until the development of advanced NAFLD and T2D.

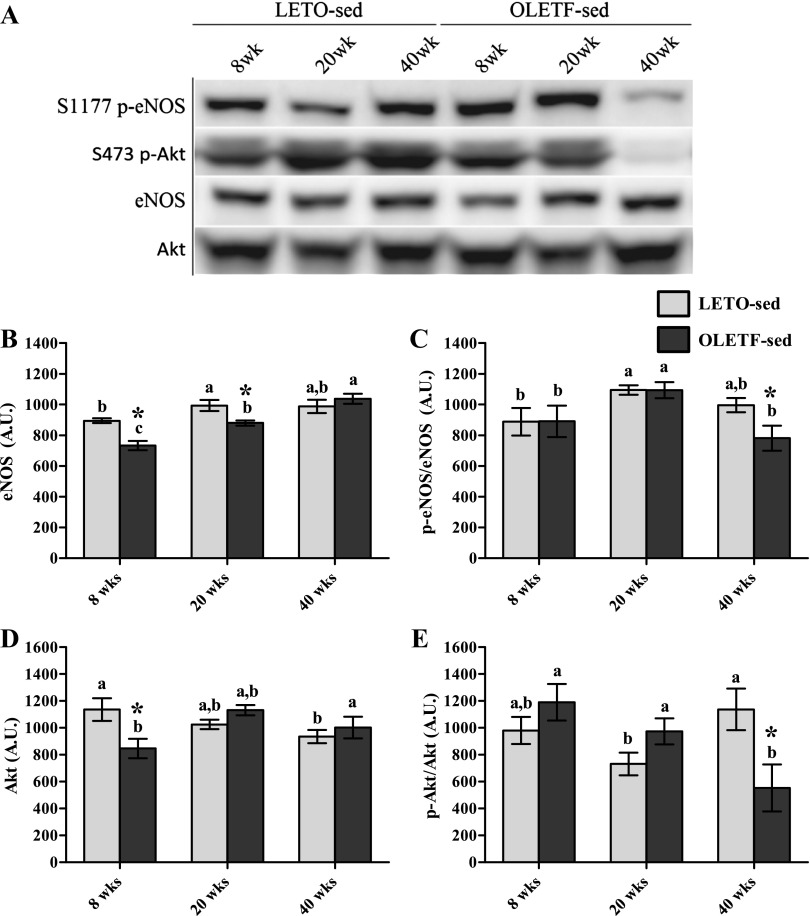

Our initial objective was to determine whether basal hepatic eNOS and its activation status via S1177 phosphorylation were affected by disease progression. We studied LETO-sed and OLETF-sed animals at three pathologically significant ages: 8, 20, and 40 wk. Total hepatic eNOS in OLETF-sed was significantly lower than LETO-sed at 8 wk and significantly increased at each successive age examined, with a 41% total increase between 8 and 40 wk (Fig. 2B). S1177 p-eNOS relative to total eNOS (p-eNOS/eNOS) revealed a significant (P < 0.05) reduction at 40 wk in OLETF-sed compared with both LETO-sed at 40 wk and OLETF-sed at 20 wk of age (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Basal activation status of hepatic endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and Akt. Representative Western blots are depicted in A, with means ± SE (n = 6–8/group) shown for total eNOS protein content (B), S1177 phosphorylated (p)-eNOS/eNOS (C), total Akt (D), and S473 p-Akt/Akt (E). a,b,c Significant difference (P < 0.05) within group across age. *Significant difference (P < 0.05) between groups within age. AU, arbitrary units.

We examined total and activated Akt (p-Akt), a kinase known to directly phosphorylate eNOS (25) and a key player in hepatic insulin signaling. S473 p-Akt/Akt was not different between LETO-sed and OLETF-sed at 8 or 20 wk (Fig. 2D); this was surprising given the dramatic elevation in serum insulin and glucose in OLETF-sed (Table 1). However, 40-wk OLETF-sed rats had significantly lower p-Akt/Akt (51%) than LETO controls (Fig. 2E), which occurred concurrently with reduced serum insulin in OLETF-sed (Table 1).

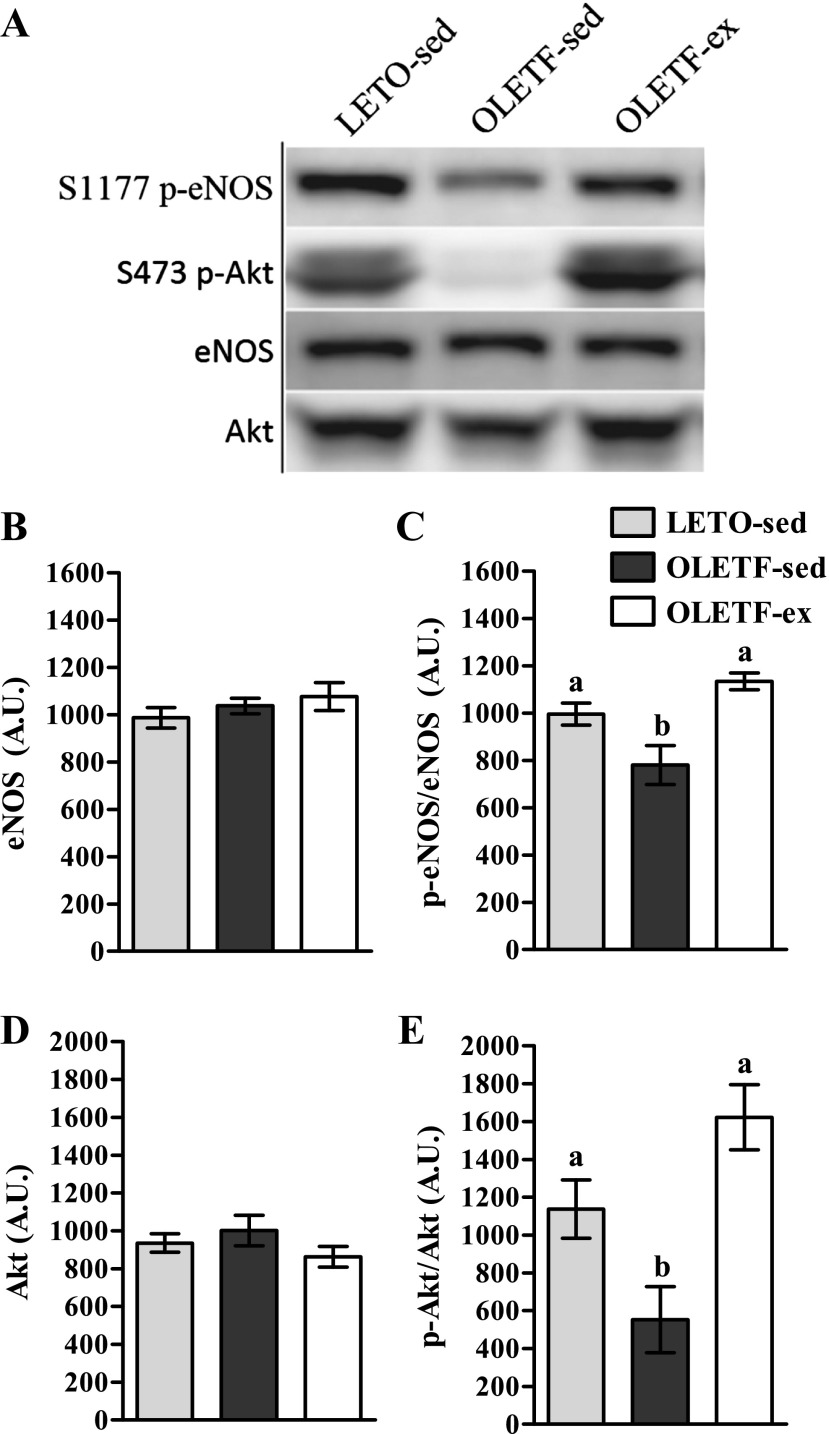

VWR by OLETF rats prevents reductions in basal hepatic p-eNOS and p-Akt.

Our laboratory has previously demonstrated that VWR by OLETF rats maintains glycemia and insulin-stimulated skeletal muscle glucose uptake and prevents obesity and NAFLD development and progression (35, 36). Herein, we investigated the possibility that this exercise-mediated outcome was associated with restoration of hepatic eNOS activation status at 40 wk of age. Total eNOS was comparable among groups at 40 wk (Fig. 3B); however, reductions in eNOS phosphorylation witnessed in OLETF-sed rats were completely prevented by VWR (Fig. 3C). Thus VWR by OLETF rats improves hepatic eNOS activation status independent of total eNOS content. Similarly, VWR prevented reductions in p-Akt at 40 wk (Fig. 3E) without influencing total Akt (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

Effects of VWR on hepatic eNOS and Akt phosphorylation in 40-wk OLETF rats. Representative Western blots are depicted in A, with means ± SE (n = 6–8/group) shown for total eNOS (B), p-eNOS/eNOS (C), total Akt (D), and p-Akt/Akt (E). a,b Significant difference (P < 0.05) within group across age.

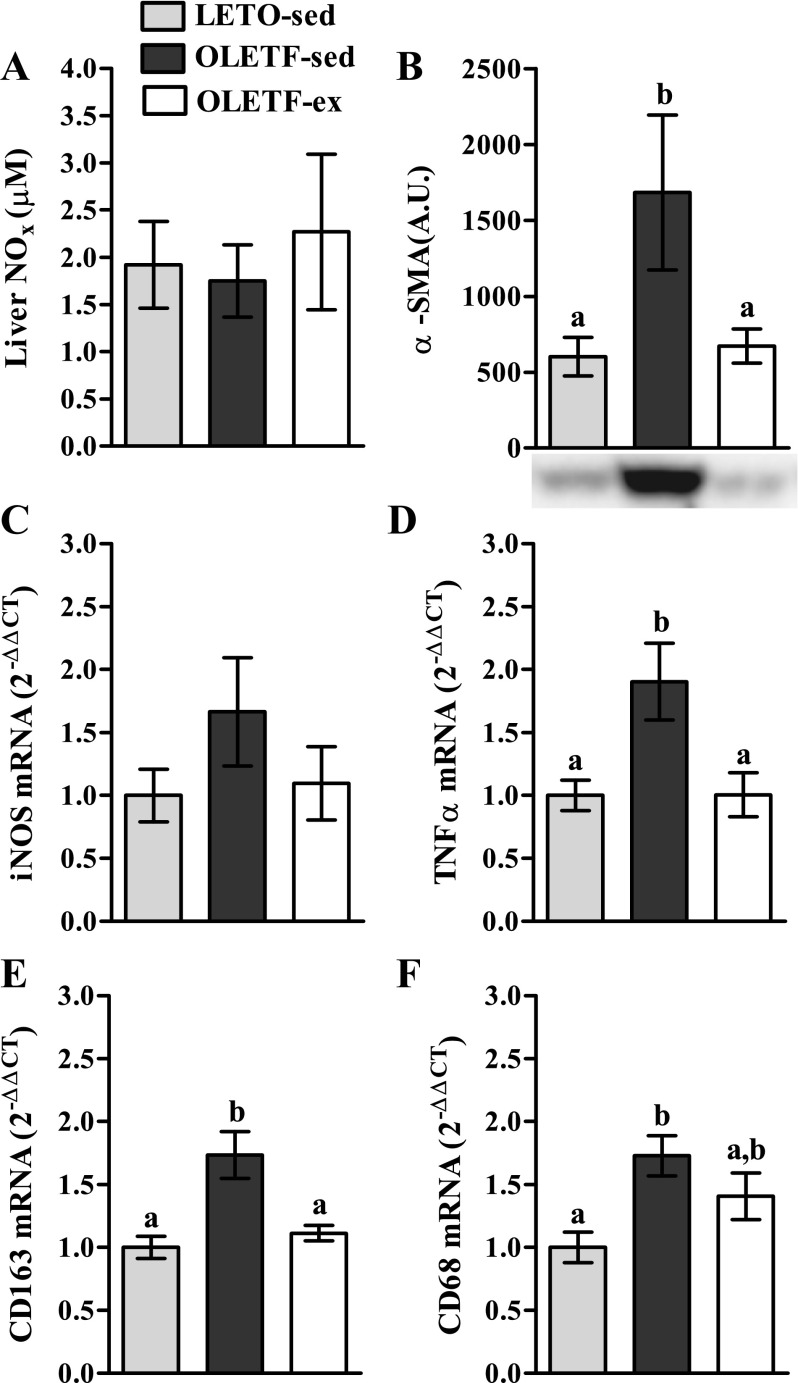

Reduced p-eNOS does not alter hepatic NOX but is associated with fibrotic and inflammatory processes.

We assessed whether reduced hepatic p-eNOS content in 40-wk OLETF-sed rats influenced global hepatic NO production. Surprisingly, NOX, an index of total NO production, was not different between groups at 40 wk of age (Fig. 4A), perhaps due to a nonsignificant increase in inducible NOS mRNA in OLETF-sed (Fig. 4C) contributing to hepatic NO production in these animals. However, because constitutively produced NO from eNOS is an important paracrine modulator of nonparenchymal cell quiescence, we further sought to determine whether this local effect was disturbed independent of total NO production by measuring markers of hepatic stellate cell and Kupffer cell activation. Indeed, we observed a significant increase in α-SMA protein content (P < 0.05, Fig. 4B), a marker of stellate cell activation and fibrogenesis, in OLETF-sed relative to LETO-sed and OLETF-ex. In addition, α-SMA protein content was significantly correlated with p-eNOS/eNOS (see Fig. 6D; r = −0.51, P < 0.05). Furthermore, markers of total macrophages (CD68 mRNA expression; Fig. 4F) and Kupffer cells (CD163 mRNA expression; Fig. 4E) were elevated in the livers of 40-wk OLETF-sed rats compared with LETO-sed and OLETF-ex animals. Additionally, elevated TNF-α mRNA (Fig. 4D) in OLETF-sed relative to the other groups provides evidence of macrophage activation and inflammation.

Fig. 4.

Total hepatic nitric oxide content (NOX; A), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) protein content (B), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA expression (C), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) mRNA expression (D), CD163 mRNA expression (E), and CD68 mRNA expression (F) in 40-wk OLETF and LETO rats. Values are means ± SE (n = 4–8/group). a,bSignificant difference (P < 0.05) within group across age.

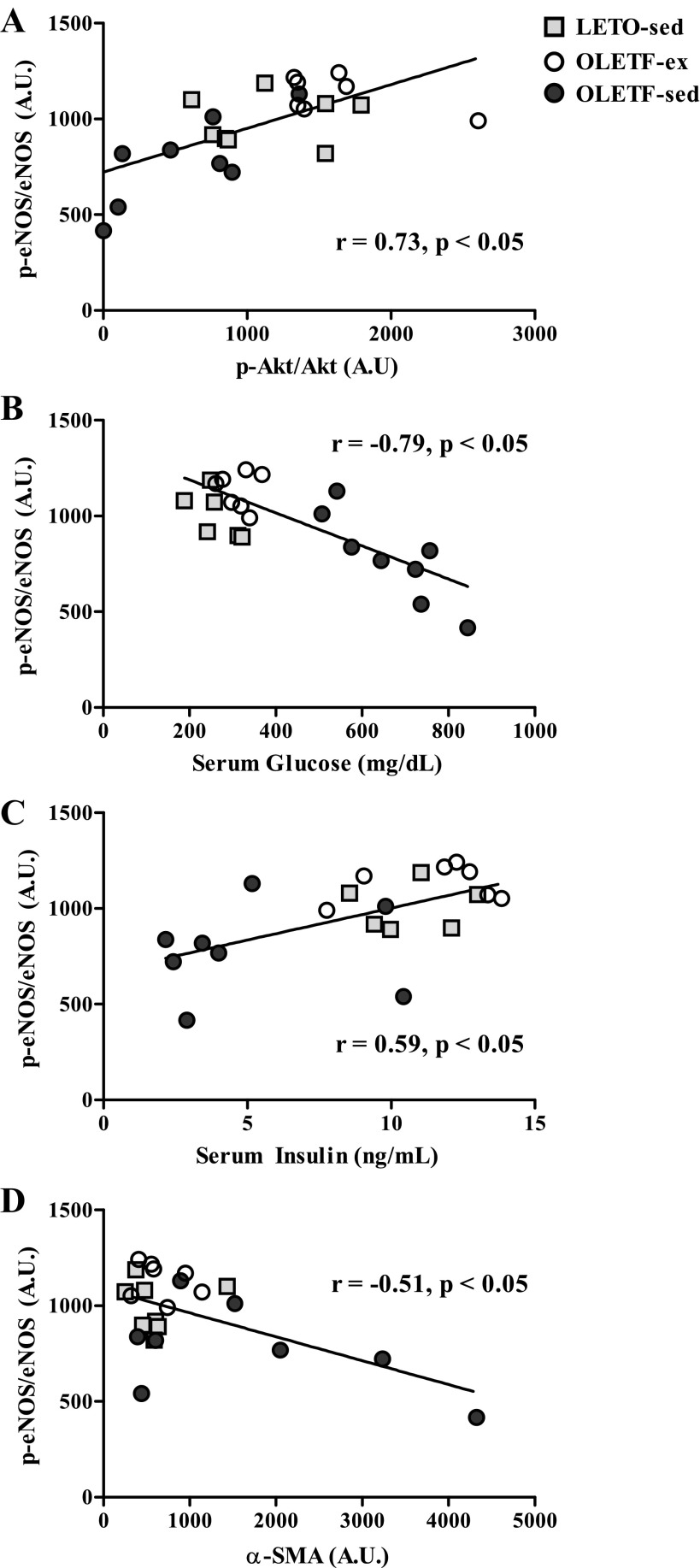

Fig. 6.

Significant (P < 0.05) correlations of p-eNOS/eNOS with p-Akt/Akt (r = 0.73; A), serum glucose (r = −0.78; B), serum insulin (r = 0.59; C), and α-SMA protein content (r = −0.51; D) in 40-wk-old LETO-sed, OLETF-sed, and OLETF-ex rats.

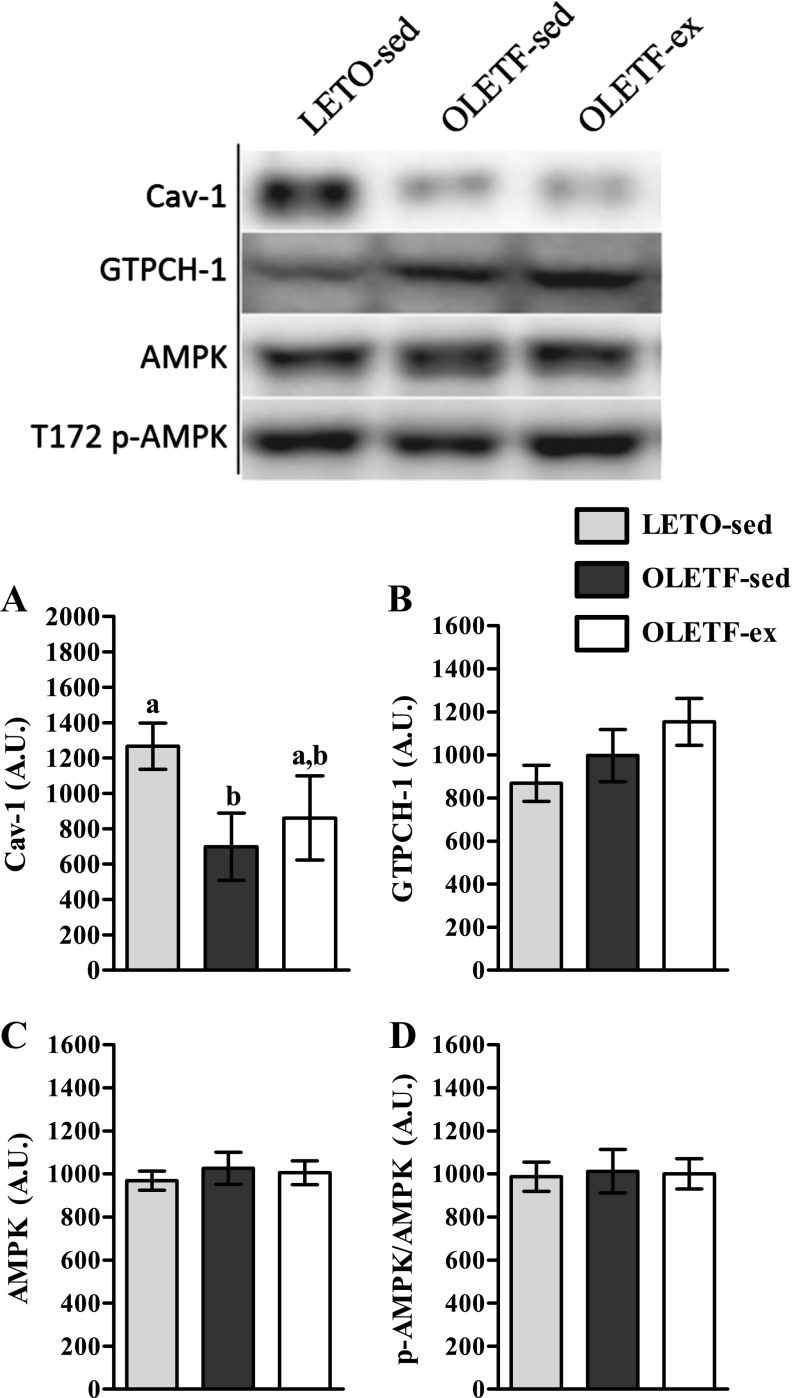

Other common molecular regulators of eNOS activation.

Finally, we investigated potential mechanisms that may influence hepatic eNOS activation and NO production. We observed no significant differences in AMPK or phosphorylated AMPK (T172) protein content among animals groups (Fig. 5, C and D, respectively). Additionally, Cav-1, a steric inhibitor of p-eNOS (5), was reduced in OLETF-sed relative to LETO-sed; whereas Cav-1 protein content in OLETF-ex was not statistically different from either group (Fig. 5A). Finally, GTPCH-1, the enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of the essential eNOS cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), also did not differ statistically among groups (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Hepatic protein abundance of caveolin-1 (Cav-1; A), guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase-1 (GTPCH-1; B), adenosine monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK; C), and p-AMPK (D) in 40-wk OLETF and LETO rats. Values are means ± SE (n = 7–8/group). a,bSignificant difference (P < 0.05) within group across age.

Hepatic eNOS activation is associated with glycemic control.

We assessed correlations between p-eNOS and p-Akt with several metabolic characteristics in 40-wk-old OLETF and LETO rats to determine any potential relationships with advancing disease. Basal p-eNOS/eNOS was significantly correlated with Akt activation status (r = 0.73; P < 0.05; Fig. 6A). In addition, p-eNOS/eNOS dropped with increasing levels of serum glucose (r = −0.78; P < 0.05; Fig. 6B) and with lower serum insulin (r = 0.59; P < 0.05; Fig. 6C) induced through T2D development in the OLETF-sed animals. Surprisingly, no significant associations were observed between eNOS phosphorylation and body weight, percent body fat, fat pad mass (omental, retroperitoneal, epididymal, and omental + retroperitoneal), liver TAGs, serum TAGs, or serum FFAs (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Exercise training is an effective treatment modality for many of the complications of obesity and insulin resistance, including improving endothelial cell function in various organ systems. However, whether exercise similarly improves hepatic endothelial function en route to prevention of NAFLD has not previously been determined. Interestingly, disrupted NO production from eNOS in the liver has been implicated in the activation of Kupffer cells (44) and stellate cells (47). Furthermore, eNOS gene knockout on a background of obese, diabetic db/db mice causes exacerbated hepatic steatosis (24). To this end, the present investigation sought to determine the activation status of hepatic eNOS via S1177 phosphorylation at pathologically significant ages in OLETF-sed rats and assess its modulation by VWR. Remarkably, hepatic eNOS activation was not reduced concurrently with insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, or mild to moderate hepatic steatosis. Rather, reduced hepatic p-eNOS emerged with the development of overt T2D and was correlated with serum insulin and glucose, as well as with the phosphorylation status of hepatic Akt. Additionally, there was an age-dependent increase in total hepatic eNOS protein in OLETF-sed rats, suggesting that eNOS upregulation may be a compensatory mechanism through which a constant pool of hepatic p-eNOS is maintained in early to moderate NAFLD. Furthermore, the reduction in p-eNOS in 40-wk OLETF-sed rats coincided with increases in markers of hepatic fibrosis, Kupffer cell presence, and hepatic inflammation, which may implicate eNOS as an important player in the transition to NASH. Finally, we report novel findings that daily exercise prevented the observed reductions in both eNOS and Akt phosphorylation witnessed in 40-wk OLETF-sed rats.

Basal levels of eNOS activation are of physiological importance in the liver.

In most tissues, endothelial NO production by eNOS is a central regulator of vascular smooth muscle tone and, consequently, governs local blood flow distribution. A different scenario predominates in the healthy liver, where the volume of hepatic blood flow is maintained at constant levels via the adenosine-mediated hepatic arterial buffer response (14–16). Rather than regulating hepatic vascular conductance, hepatic endothelial cell NO production appears to be an important paracrine signal to liver nonparenchymal cells. Reduced eNOS activity and NO production can activate Kupffer cells, which initiate inflammatory processes and potentiate hepatic insulin resistance (44). In addition, hepatic eNOS-mediated NO production is critical to maintaining the quiescent state of hepatic stellate cells, with disruption causing stellate cell transition to an activated myofibroblastic state (47). Furthermore, the fact that obese eNOS knockout mice develop greater hepatic steatosis indicates that disturbed hepatic eNOS function may accelerate NAFLD (24). In agreement with these studies, our data indicate that makers of both stellate cell (Fig. 4B and 5C) and Kupffer cell (Fig. 4, C–F) activation occur with reduced p-eNOS in 40-wk OLETF-sed rats without alteration of total hepatic NOX. The mechanism underlying the transition in NAFLD severity to NASH, which is characterized by inflammation and fibrosis, is an active area of investigation. Although causal relationships cannot be established at this time, the current data allow for generation of the novel hypothesis that reduced hepatic eNOS NO production is an important event in the pathogenesis of NASH. Given the substantial clinical utility and diversity of currently available NO-based therapies, future investigations designed to directly test this hypothesis are needed.

Other potential causes of reduced eNOS phosphorylation and NO production are not affected by advanced NAFLD and T2D.

Enzymatic activity of eNOS is controlled by a complicated, dynamic host of kinases/phosphatases, co-factors, and steric interactions. We identified potential molecular targets that may influence eNOS activity and/or NO bioavailability in our 40-wk-old cohort of rats. First, Cav-1 sterically prevents eNOS activation (5) and is elevated in rat models of experimental cirrhosis (39, 41), whereas here we report Cav-1 was significantly reduced in OLETF-sed animals. Second, GTPCH-1 catalyzes the production of BH4, an essential eNOS cofactor (46), and its expression is reduced in experimental models of diabetes (10, 23, 42). However, our results reveal no differences in GTPCH-1 expression. Finally, we detected no differences in hepatic AMPK, the activation of which both improves liver insulin sensitivity (9) and phosphorylates eNOS at S1177 (4, 12). Collectively, common mechanisms influencing endothelial NO homeostasis in other models of diabetes and chronic liver disease do not appear to be critical in hepatic NO production in the OLETF rat model at the observed disease stages.

Maintained insulin production, but not insulin resistance, may explain the current results.

A novel finding of the present investigation is that basal hepatic eNOS activation is preserved in insulin-resistant 20-wk-old OLETF-sed rats, despite evidence of endothelial dysfunction in multiple vascular beds at this age in this model (1, 3, 21, 22). However, this preservation is lost by 40 wk of age with the development of pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and overt T2D. One hypothesis is that the hepatic circulation is less sensitive to hyperinsulinemia than other tissues. The pancreas secretes insulin directly into the portal vein, resulting in ∼3- (fasted) to ∼30-fold (postprandial) greater portal insulin concentrations compared with peripheral levels (8). As such, the healthy liver is exposed to hyperinsulinemia in its physiological milieu, and the liver may either 1) depend on this environment, or 2) have mechanisms in place to reduce susceptibility to insulin resistance. That basal hepatic Akt activation, which is classically reduced in insulin-resistant states, was maintained in 20-wk, but not 40-wk, OLETF-sed rats further supports this concept. Thus diminished insulin production by β-cells, secondary to prolonged hyperinsulinemia necessary to support skeletal muscle glucose uptake (35), may pose a greater homeostatic insult to the hepatic vasculature than does hyperinsulinemia.

Similar reasoning may also explain the present finding that VWR prevented reductions in both hepatic eNOS and Akt activation in 40-wk OLETFs. Exercise is generally regarded to improve endothelial cell function via repeated, transient increases in hemodynamic shear stress during the exercise bout (13). However, shear-mediated effects are unlikely, as liver blood flow is maintained or even reduced during exercise. Instead, our present findings, coupled with a previous report (35), suggest that VWR maintains whole body glycemic control and insulin sensitivity, perhaps through proper skeletal muscle glucose disposal, which contributes to normal hepatic Akt activation and maintenance of hepatic eNOS phosphorylation and activation.

Discontinuities between the present findings and previous investigations.

The OLETF rat develops obesity, insulin resistance, T2D, and NAFLD gradually throughout the lifespan, which is similar to human disease. To date, the only reports of hepatic endothelial cell dysfunction in the context of NAFLD arise from high-fat feeding of often >60% kcal from saturated fat to rapidly (1–8 wk) induce obesity and insulin resistance. These studies rapidly elevate FFAs and TAGs, and findings suggest that reduced hepatic endothelial cell dysfunction is an early and potentially causative event in the development of NAFLD (11, 29, 30, 44). In contrast, hyperphagic OLETF rats fed a normal chow diet exhibit increases in serum FFAs and TAG over several weeks/months (33). Taken collectively, there may be multiple mechanisms at play, depending on the dietary insults, with our present data supporting a role for reduced hepatic eNOS activity in advanced NAFLD and T2D. Additional work in this area is warranted.

Experimental consideration.

A potential limitation to this investigation is that analyses were performed on whole liver homogenate rather than in isolated liver cell types. As such, we are unable to confirm which liver cell type(s) expresses eNOS. Considerable incongruity exists in the literature regarding whether eNOS expression is restricted to hepatic endothelial cells or is more ubiquitous. Evidence from isolated liver cells and immunohistochemistry in various species and disease phenotypes support each side of this discrepancy (18–20, 26, 40, 45). However, studies that utilize in vivo manipulations of eNOS and/or NO signaling that are not necessarily endothelial specific (e.g., eNOS knockout, NO donors, sGC activators) indicate that the physiological role of hepatic eNOS discussed herein is not contingent on one cell type. As such, we contend that the central finding of this investigation, i.e., reduced basal hepatic eNOS activation in diabetic conditions occurs in conjunction with the transition to NASH and is prevented by voluntary exercise, remains clear.

Summary and conclusions.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that reduced basal hepatic eNOS activation status occurs in relation to reduced insulin production, hyperglycemia, and blunted Akt activation in T2D OLETF rats with NAFLD. Interestingly, this reduction occurs as the liver phenotype is transitioning to NASH, potentially implicating reduced eNOS activation as a contributor to this pathology. Other affecters of eNOS activity and NO production, including excess adiposity, Cav-1, GTPCH-1, and AMPK, do not appear to explain the present findings. Moreover, we provide the first account that daily exercise prevents reductions in hepatic eNOS phosphorylation, perhaps via maintained insulin sensitivity and glycemic control in hyperphagic OLETF rats. The present results encourage further investigation into the pathophysiological significance of hepatic NO signaling and its mitigation by exercise.

GRANTS

This work was supported by an National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant (HL-36088; M. H. Laughlin), a Veterans Affairs VHA-CDA2 Grant (1299-02; R. S. Rector), and a University of Missouri Life Sciences Fellowship (R. D. Sheldon). This work was completed with resources and the use of facilities at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans Hospital in Columbia, MO.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.D.S., M.H.L., and R.S.R. conception and design of research; R.D.S., M.H.L., and R.S.R. performed experiments; R.D.S., M.H.L., and R.S.R. analyzed data; R.D.S., M.H.L., and R.S.R. interpreted results of experiments; R.D.S. and R.S.R. prepared figures; R.D.S. and R.S.R. drafted manuscript; R.D.S., M.H.L., and R.S.R. edited and revised manuscript; R.D.S., M.H.L., and R.S.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Grace Meers for technical assistance, and Melissa Linden for help with data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bender SB, Newcomer SC, Laughlin MH. Differential vulnerability of skeletal muscle feed arteries to dysfunction in insulin resistance: impact of fiber type and daily activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1434–H1441, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology 40: 1387–1395, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bunker AK, Arce-Esquivel AA, Rector RS, Booth FW, Ibdah JA, Laughlin MH. Physical activity maintains aortic endothelium-dependent relaxation in the obese type 2 diabetic OLETF rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H1889–H1901, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen ZP, Mitchelhill KI, Michell BJ, Stapleton D, Rodriguez-Crespo I, Witters LA, Power DA, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Kemp BE. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylation of endothelial NO synthase. FEBS Lett 443: 285–289, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Z, Bakhshi FR, Shajahan AN, Sharma T, Mao M, Trane A, Bernatchez P, van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Bonini MG, Skidgel RA, Malik AB, Minshall RD. Nitric oxide-dependent Src activation and resultant caveolin-1 phosphorylation promote eNOS/caveolin-1 binding and eNOS inhibition. Mol Biol Cell 23: 1388–1398, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Takeda N, Nagata C, Takeda J, Sarui H, Kawahito Y, Yoshida N, Suetsugu A, Kato T, Okuda J, Ida K, Yoshikawa T. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a novel predictor of cardiovascular disease. World J Gastroenterol 13: 1579–1584, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haram PM, Adams V, Kemi OJ, Brubakk AO, Hambrecht R, Ellingsen O, Wisloff U. Time-course of endothelial adaptation following acute and regular exercise. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 13: 585–591, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horwitz DL, Starr JI, Mako ME, Blackard WG, Rubenstein AH. Proinsulin, insulin, and C-peptide concentrations in human portal and peripheral blood. J Clin Invest 55: 1278–1283, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iglesias MA, Ye JM, Frangioudakis G, Saha AK, Tomas E, Ruderman NB, Cooney GJ, Kraegen EW. AICAR administration causes an apparent enhancement of muscle and liver insulin action in insulin-resistant high-fat-fed rats. Diabetes 51: 2886–2894, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johns DG, Dorrance AM, Tramontini NL, Webb RC. Glucocorticoids inhibit tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent endothelial function. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 226: 27–31, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim F, Pham M, Maloney E, Rizzo NO, Morton GJ, Wisse BE, Kirk EA, Chait A, Schwartz MW. Vascular inflammation, insulin resistance, and reduced nitric oxide production precede the onset of peripheral insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 1982–1988, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroller-Schon S, Jansen T, Hauptmann F, Schuler A, Heeren T, Hausding M, Oelze M, Viollet B, Keaney JF, Jr, Wenzel P, Daiber A, Munzel T, Schulz E. α1AMP-activated protein kinase mediates vascular protective effects of exercise. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32: 1632–1641, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laughlin MH, Newcomer SC, Bender SB. Importance of hemodynamic forces as signals for exercise-induced changes in endothelial cell phenotype. J Appl Physiol 104: 588–600, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lautt WW. Mechanism and role of intrinsic regulation of hepatic arterial blood flow: hepatic arterial buffer response. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 249: G549–G556, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lautt WW. Regulatory processes interacting to maintain hepatic blood flow constancy: vascular compliance, hepatic arterial buffer response, hepatorenal reflex, liver regeneration, escape from vasoconstriction. Hepatol Res 37: 891–903, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lautt WW, Legare DJ, d'Almeida MS. Adenosine as putative regulator of hepatic arterial flow (the buffer response). Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 248: H331–H338, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laye MJ, Rector RS, Borengasser SJ, Naples SP, Uptergrove GM, Ibdah JA, Booth FW, Thyfault JP. Cessation of daily wheel running differentially alters fat oxidation capacity in liver, muscle, and adipose tissue. J Appl Physiol 106: 161–168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leifeld L, Fielenbach M, Dumoulin FL, Speidel N, Sauerbruch T, Spengler U. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) expression in fulminant hepatic failure. J Hepatol 37: 613–619, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNaughton L, Puttagunta L, Martinez-Cuesta MA, Kneteman N, Mayers I, Moqbel R, Hamid Q, Radomski MW. Distribution of nitric oxide synthase in normal and cirrhotic human liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 17161–17166, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mei Y, Thevananther S. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is a key mediator of hepatocyte proliferation in response to partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology 54: 1777–1789, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikus CR, Rector RS, Arce-Esquivel AA, Libla JL, Booth FW, Ibdah JA, Laughlin MH, Thyfault JP. Daily physical activity enhances reactivity to insulin in skeletal muscle arterioles of hyperphagic Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats. J Appl Physiol 109: 1203–1210, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikus CR, Roseguini BT, Uptergrove GM, Morris EM, Rector RS, Libla JL, Oberlin DJ, Borengasser SJ, Taylor AM, Ibdah JA, Laughlin MH, Thyfault JP. Voluntary wheel running selectively augments insulin-stimulated vasodilation in arterioles from white skeletal muscle of insulin-resistant rats. Microcirculation 19: 729–738, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell BM, Dorrance AM, Mack EA, Webb RC. Glucocorticoids decrease GTP cyclohydrolase and tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent vasorelaxation through glucocorticoid receptors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 43: 8–13, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohan S, Reddick RL, Musi N, Horn DA, Yan B, Prihoda TJ, Natarajan M, Abboud-Werner SL. Diabetic eNOS knockout mice develop distinct macro- and microvascular complications. Lab Invest 88: 515–528, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montagnani M, Chen H, Barr VA, Quon MJ. Insulin-stimulated activation of eNOS is independent of Ca2+ but requires phosphorylation by Akt at Ser1179. J Biol Chem 276: 30392–30398, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morales-Ruiz M, Cejudo-Martin P, Fernandez-Varo G, Tugues S, Ros J, Angeli P, Rivera F, Arroyo V, Rodes J, Sessa WC, Jimenez W. Transduction of the liver with activated Akt normalizes portal pressure in cirrhotic rats. Gastroenterology 125: 522–531, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musso G, Gambino R, Cassader M, Pagano G. Meta-analysis: natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for liver disease severity. Ann Med 43: 617–649, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ong JP, Pitts A, Younossi ZM. Increased overall mortality and liver-related mortality in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 49: 608–612, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasarín M, Abraldes JG, Rodríguez-Vilarrupla A, La Mura V, García-Pagán JC, Bosch J. Insulin resistance and liver microcirculation in a rat model of early NAFLD. J Hepatol 55: 1095–1102, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasarín M, La Mura V, Gracia-Sancho J, García-Calderó H, Rodríguez-Vilarrupla A, García-Pagán JC, Bosch J, Abraldes JG. Sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction precedes inflammation and fibrosis in a model of NAFLD. PLoS One 7: e32785, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rector RS, Thyfault JP. Does physical inactivity cause nonalcoholic fatty liver disease? J Appl Physiol 111: 1828–1835, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Morris RT, Laye MJ, Borengasser SJ, Booth FW, Ibdah JA. Daily exercise increases hepatic fatty acid oxidation and prevents steatosis in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G619–G626, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Uptergrove GM, Morris EM, Naples SP, Borengasser SJ, Mikus CR, Laye MJ, Laughlin MH, Booth FW, Ibdah JA. Mitochondrial dysfunction precedes insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis and contributes to the natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in an obese rodent model. J Hepatol 52: 727–736, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rector RS, Thyfault JP, Wei Y, Ibdah JA. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome: an update. World J Gastroenterol 14: 185–192, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rector RS, Uptergrove GM, Borengasser SJ, Mikus CR, Morris EM, Naples SP, Laye MJ, Laughlin MH, Booth FW, Ibdah JA, Thyfault JP. Changes in skeletal muscle mitochondria in response to the development of type 2 diabetes or prevention by daily wheel running in hyperphagic OLETF rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 298: E1179–E1187, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rector RS, Uptergrove GM, Morris EM, Borengasser SJ, Laughlin MH, Booth FW, Thyfault JP, Ibdah JA. Daily exercise vs. caloric restriction for prevention of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the OLETF rat model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300: G874–G883, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rockey DC, Chung JJ. Reduced nitric oxide production by endothelial cells in cirrhotic rat liver: endothelial dysfunction in portal hypertension. Gastroenterology 114: 344–351, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez B, Torres DM, Harrison SA. Physical activity: an essential component of lifestyle modification in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9: 726–731, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah V, Cao S, Hendrickson H, Yao J, Katusic ZS. Regulation of hepatic eNOS by caveolin and calmodulin after bile duct ligation in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G1209–G1216, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah V, Haddad FG, Garcia-Cardena G, Frangos JA, Mennone A, Groszmann RJ, Sessa WC. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are responsible for nitric oxide modulation of resistance in the hepatic sinusoids. J Clin Invest 100: 2923–2930, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah V, Toruner M, Haddad F, Cadelina G, Papapetropoulos A, Choo K, Sessa WC, Groszmann RJ. Impaired endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity associated with enhanced caveolin binding in experimental cirrhosis in the rat. Gastroenterology 117: 1222–1228, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stranahan AM, Arumugam TV, Cutler RG, Lee K, Egan JM, Mattson MP. Diabetes impairs hippocampal function through glucocorticoid-mediated effects on new and mature neurons. Nat Neurosci 11: 309–317, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, Rodella S, Tessari R, Zenari L, Day C, Arcaro G. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and its association with cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 30: 1212–1218, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tateya S, Rizzo NO, Handa P, Cheng AM, Morgan-Stevenson V, Daum G, Clowes AW, Morton GJ, Schwartz MW, Kim F. Endothelial NO/cGMP/VASP signaling attenuates Kupffer cell activation and hepatic insulin resistance induced by high-fat feeding. Diabetes 60: 2792–2801, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuchiya K, Accili D. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells link hyperinsulinemia to hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes 62: 1478–1489, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia Y, Tsai AL, Berka V, Zweier JL. Superoxide generation from endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent and tetrahydrobiopterin regulatory process. J Biol Chem 273: 25804–25808, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xie G, Wang X, Wang L, Wang L, Atkinson RD, Kanel GC, Gaarde WA, Deleve LD. Role of differentiation of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in progression and regression of hepatic fibrosis in rats. Gastroenterology 142: 918–927 e916, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ying X, Jiang Y, Qian Y, Jiang Z, Song Z, Zhao C. Association between insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in Chinese adults. Iran J Public Health 41: 45–49, 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]