Abstract

Objective

Although physical activity is beneficial for breast cancer survivors, the majority do not meet physical activity public health recommendations. The purpose of this study was to test a social cognitive theory (SCT) model of physical activity behavior in a sample of long-term breast cancer survivors using both self-report and objective measures of physical activity.

Methods

Participants (N= 1527) completed measures of physical activity, self-efficacy, goals, outcome expectations, fatigue, and social support at baseline and 6-month follow-up. A subsample (n= 370) was randomly selected to wear an accelerometer. It was hypothesized that self-efficacy directly and indirectly influences physical activity through goals, social support, fatigue, and outcome expectations. Relationships were examined using panel analysis within a covariance modeling framework.

Results

The hypothesized model provided a good model-data fit (χ2 = 1168.73, df= 271, p= <.001; CFI=.96; SRMR = 0.04) in the full sample when controlling for covariates. At baseline, self-efficacy directly and indirectly, via goals, outcome expectations and social support, influenced physical activity. These relationships were also supported across time. Additionally, the hypothesized model was supported in the subsample with accelerometer data (χ2 = 656.88, df = 330, p = 0.00, CFI = 0.95,SRMR = 0.05).

Conclusions

This study validates a social cognitive model for understanding physical activity behavior in long-term breast cancer survivors. Future studies should be designed to replicate this model in other breast cancer survivor populations and the findings should be applied to the development of future physical activity programs and studies for this population.

Keywords: Cancer, Oncology, Physical Activity, Breast Cancer Survivors, Social Cognitive Theory

INTRODUCTION

A substantial body of literature exists that provides evidence for the beneficial effects of regular physical activity for breast cancer survivors. Moreover, it is recognized that physical activity holds significant promise as a potential therapy for reducing the negative effects of breast cancer treatment [1,2]. In general, physical activity has been associated with declines in negative physical, psychological, and emotional side effects of treatment and increased quality of life in cross-sectional [3], longitudinal [4], and randomized controlled [1,2] studies in breast cancer survivors. Physical activity is also associated with reductions in the risk of all-cause mortality, breast cancer mortality and cancer recurrence [5-7]. Collectively, the existing research implies that breast cancer survivors who participate in any type of physical activity experience some positive effects in comparison to sedentary survivors [8]. Unfortunately, only about one-third of breast cancer survivors meet the current public health recommendations [8,9]. The majority of breast cancer survivors experience a decline in physical activity in the 12 months following a breast cancer diagnosis with activity levels rarely returning to pre-diagnosis levels [10,11], and those individuals who are most active pre-diagnosis experiencing the greatest declines in physical activity post-diagnosis [11,12].

One of the more commonly applied theoretical models for understanding physical activity behavior has been Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [15-17]). However, unlike other models such as the theory of planned behavior [18-19], the components that comprise SCT have rarely been applied in the manner proposed by Bandura (2004). SCT [15-17] is unique compared to other theories of health behavior in that it specifies a core set of determinants, the mechanisms through which they work and the optimal ways of translating this knowledge into effective practice rather than simply focusing on predicting health habits [16]. Thus, SCT provides a comprehensive framework by which to understand not only what factors influence physical activity behavior, but provides insight to how these factors can be manipulated in order to change physical activity behavior which is an area in which other health behavior theories may fall short.

The primary components of the SCT model are self-efficacy, outcome expectations, goals, and sociocultural factors (facilitators and impediments). Self-efficacy is defined as an individual's beliefs in one's capabilities to successfully execute a task, and has been consistently identified as a correlate of physical activity adoption and maintenance in the general population [20,21] and in breast cancer survivors [22,23]. Outcome expectations reflect beliefs that a given behavior will produce a specific outcome, and lie along three related, but conceptually independent, subdomains representing physical, social, and self-evaluative outcome expectations [17]. Stronger outcome expectations have been associated with greater physical activity participation in breast cancer survivors and the general population [23-25]. Goals are powerful motivators and are important for focusing and directing activity and effort and have been associated with increased use of behavioral strategies for engaging in physical activity [26]. Additionally, setting higher goals has been associated with greater increases in physical activity participation [27]. There are a host of individual barriers to physical activity participation in breast cancer survivors including disease characteristics, fatigue, lack of interest or time, and lack of social support. Potential individual facilitators of physical activity participation include higher levels of social support, having completed all treatment, higher functional status, and lower levels of fatigue [23, 28, 29]. These relationships are all postulated to be reciprocal in nature. For example higher levels of self-efficacy have been associated with higher levels of social support and vice versa.

Bandura [16] has explicitly outlined structural paths of influence which hypothesize that self-efficacy has both direct and indirect influences on behavior. Individuals with higher levels of self-efficacy have more positive expectations about what the behavior will bring about, set higher goals for themselves, and are more likely to believe they are capable of overcoming difficulties and barriers. Unfortunately, most applications of SCT in the physical activity literature, in general, and the breast cancer-specific literature have focused predominantly on self-efficacy as a determinant of physical activity and failed to consider all of the pathways proposed by Bandura [16]. Thus, it is important to determine comprehensively how the SCT constructs operate together in the context of changing physical activity behavior in breast cancer survivors as all of the constructs are potentially modifiable and could be targeted and manipulated to enhance physical activity in this population.

A prospective study design was utilized to test the full social cognitive model for physical activity participation using the structural pathways proposed by Bandura [16]. Specifically, it was hypothesized that at baseline, self-efficacy would have a direct effect on physical activity behavior and an indirect effect through outcome expectations, goals, facilitators and impediments. These latter constructs were also expected to have direct effects on physical activity. The same series of hypotheses were proposed among changes in these constructs across the 6-month period. Additionally, we conducted the same analyses in a subsample using an objective measure of physical activity.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Participants

Women over the age of 18 who had been diagnosed with breast cancer were eligible to participate in this study. Participants were also required to be English speaking and have access to a computer.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic information was collected including marital status, number of children, age, date of birth, occupation, income, and education.

Health and cancer history

Participants’ were asked to indicate (yes or no) whether or not they have been diagnosed with a list of 18 different comorbidites (i.e. diabetes, obesity, hypertension) and to report information regarding their breast cancer and other cancer history. Current height and weight were also collected to calculate body mass index (BMI).

Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire (GLTEQ) [30]

Participants were asked to self-report the frequency of their current participation in strenuous (e.g., jogging), moderate (e.g., fast walking), and mild (e.g., easy walking) exercise over the past seven days, and these frequencies were multiplied by 9, 5, and 3 metabolic equivalents, respectively, and summed to form a measure of total leisure time activity. The GLTEQ is a simple, self-administered instrument that has been widely used in epidemiological, clinical, and behavioral change studies and has been shown to be both a valid and reliable measure of physical activity participation [30].

Actigraph accelerometer (model GT1M version, Health One Technology, Fort Walton Beach, FL)

The Actigraph was used to measure physical activity in a subsample of the study population. It has been shown to have acceptable reliability and validity among young, middle-aged and older adults [31,32, 33] as well as other cancer survivor populations and individuals suffering from chronic disease [34,35]. Participants were instructed to wear the monitor for seven consecutive days on the non-dominant hip during all waking hours, except for when bathing or swimming. Activity data was collected in one-minute intervals (epochs). For the purposes of this study, a valid day of data consisted of an individual wearing the monitor for at least 10 valid hours with a valid hour being defined as having no more than 30 minutes of consecutive zeros. The total number of counts for each valid day was summed and divided by the number of days of monitoring to arrive at an average number of activity counts. Only data for individuals with a minimum of 3 valid days of wear time were included in analyses [36]. Of those individuals meeting that criteria, on average 95.6% and 94% of the days on which the monitor was worn and properly functioning were considered valid at baseline and follow-up, respectively, for the purposes of this study.

Self-efficacy

The 6-item Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale (EXSE) [37] was used to assess participants’ beliefs in their ability to exercise five times per week, at a moderate intensity, for 30 or more minutes per session at two week increments over the next 12 weeks. The 15-item Barriers Self-Efficacy Scale (BARSE) [37] assessed participants’ perceived capabilities to exercise three times per week for 40 minutes over the next two months in the face of barriers to participation. Items from each scale are scored on a 100-point percentage scale with 10-point increments, ranging from 0% (not at all confident) to 100% (highly confident). For each measure, total scores are calculated using the average confidence rating.

Multidimensional Outcome Expectation for Exercise Scale (MOEES) [38]

The MOEES was used to assess participants’ social (4 items), self-evaluative (5 items), and physical (6 items) outcome expectations on a 5 point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Subscale score are obtained by summing each of the individual items.

Exercise Goal Setting Scale (EGS) [39]

This 10-item scale assessed participants exercise-related goal-setting, self-monitoring and problem solving and instructs participants to indicate the extent to which each of the statements describes them on a scale from 1 (does not describe) to 6 (describes completely). An average of the items is used to obtain the total score.

Fatigue Symptom Inventory (FSI [40])

The FSI was used to assess the partcipants’ severity, frequency, and diurnal variation of fatigue, and its perceived interference with quality of life.

Social Support for Exercise Scale (SSE) [41]

This scale assesses the degree to which friends and family have demonstrated support for exercise behaviors in the previous 3 months. The frequency for each item was rated once for both family and friends on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Subscale score were calculated by summing the 10 items from each of the components.

Study Recruitment and Randomization

All study procedures were approved by the university institutional review board. Participants were recruited utilizing the Army of Women©, University e-mail, fliers, print media, and community groups and postings. Initially, participants were sent a link to a website providing a full description of the study. Participants meeting eligibility criteria were extended an offer to participate and an electronic version of the informed consent. Qualified participants were randomized into the (a) survey only or (b) survey and accelerometer group and informed of group assignment via e-mail.

Initially, 2,546 women expressed an interest in participating in the present study. Of those individuals, 1,631 (64%) responded to study investigators and qualified to participate with 99.8% of these women citing Army of Women as their primary source of recruitment. From the larger sample, 500 women were randomly selected to wear the accelerometer. Women who completed at least half of the study survey at baseline were re-sent study materials at 6 months. Thus, a total of 1,527 women were included in the present analyses.

Data Collection

Individuals randomized to the survey only group were sent an individualized secure link to the study questionnaires. For individuals randomized to wear the accelerometer, a study packet was prepared that contained an accelerometer, record of use form, instructions, mailing checklist and a self-addressed stamped envelope. When the study packet was placed in the mail, participants were sent an e-mail containing notification that their accelerometer was en route as well as the link to the study questionnaires. Participants in each group were asked to return study materials within two weeks of receipt. For individuals assigned to the accelerometer group, reminder e-mails were continued until the accelerometer was returned to study investigators. The same procedures were followed at 6 months.

Data Analysis

To examine the hypothesized relationships, two panel analyses within a covariance framework were conducted in Mplus V6.0 [42], first, utilizing the entire sample and, then, using only the subsample assigned to the accelerometer group. Full-information maximum likelihood (FIML), an excellent approach to the analysis of missing data in structural equation modeling, was used in the present study as a result of preliminary analyses indicating missing data were missing at random (MAR) [43-45]. Output regarding these data is available from the author upon request.

At baseline, the extent of missing data ranged from 8.8% (BARSE) to 15.0% (GLTEQ). Missing data at 6-months ranged from 25.2% (MOEES) to 27.6% (GLTEQ) and were largely the result of loss to follow-up.

The model tested hypothesized the following relationships: (a) a direct path from self-efficacy to outcome expectations, goals, impediments and facilitators (social support, fatigue), and physical activity; (b) direct paths from outcome expectations, goals, and impediments and facilitators to physical activity; and (c) a direct path from self-efficacy to physical activity and indirect paths through outcome expectations, goals, and impediments and facilitators. Latent constructs included: self-efficacy with BARSE and EXSE as indicators, fatigue with the three subscales from the FSI as indicators, and social support with the two SSE subscales as indicators. In the accelerometer subsample, physical activity was modeled as a latent construct with the total GLTEQ score and average accelerometer counts as indicators. The models were tested controlling for covariates including age, education, income, body mass index, number of comorbidities, time since diagnosis and stage of disease. In addition to the hypothesized paths, stability coefficients were calculated [46] to reflect correlations between the same variables measured in each model separately across time while controlling for the influence of other variables in the model.

Several indices of model fit were used. The chi-square statistic assessed absolute fit of the model to the data [47]. Values for the standardized root mean residual (SRMR) approximating 0.08 and zero signify close and exact fit of the model, respectively [48,49]. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) suggests that a minimally acceptable fit value is 0.90 [50] and that values approximating 0.95 or greater indicate good fit [49].

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Participants were a nationwide sample of middle-aged (M age= 56.2, SD = 9.4) breast cancer survivors. The majority of the sample was white (97.0%) and non-Hispanic/Latino (98.5%). About two-thirds of the sample (67.0%) had at least a college degree, and 86.0% of the sample had an annual household income greater than or equal to $40,000. Data regarding self-reported comorbidities can be found in Table 1. Disease specific sample characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Sample Baseline Demographics

| Characteristic | Total Sample (N= 1527) M (SD) | Accel Group (n= 370) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | 56.18 (9.41) | 56.50 (9.33) |

| Body Mass Index | 26.57 (5.74) | 25.90 (5.14) |

| Race | ||

| White | 97.0% | 96.7% |

| Asian | 0.6% | 1.1% |

| African American | 1.6% | 0.8% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.7% | 1.1% |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.3% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.5% | 1.9% |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 98.5% | 98.1% |

| Education | ||

| < College Education | 33.0% | 33.9% |

| ≥ College Education | 67.0% | 66.1% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 72.6% | 75.1% |

| Divorced/Separated | 10.5% | 10.4% |

| Partnered/Significant Other | 5.1% | 5.2% |

| Single | 6.7% | 5.2% |

| Widowed | 5.1% | 4.1% |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 37.5% | 36.7% |

| Retired, not working at all | 26.3% | 28.8% |

| Part-time | 14.6% | 14.9% |

| Retired, working part-time | 7.4% | 7.3% |

| Full-time homemaker | 6.4% | 4.6% |

| Laid off/unemployed | 4.0% | 3.8% |

| Disabled | 1.6% | 1.6% |

| Self-employed | 1.0% | 1.1% |

| Student | 0.7% | 0.8% |

| Other | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| Income | ||

| < $40,000 | 14.0% | 12.6% |

| ≥ $40,000 | 86.0% | 87.4% |

| Health Conditions | ||

| Arthritis | 33.4% | 33.5% |

| Osteoporosis | 18.9% | 16.6% |

| Asthma | 10.3% | 9.7% |

| COPD, ARDS or Emphysema | 2.3% | 2.5% |

| Angina | 0.6% | 0.8% |

| Congestive Heart Failure/Heart Disease | 1.9% | 3.0% |

| Heart Attack | 0.4% | 0.6% |

| Stroke/TIA | 1.7% | 1.4% |

| Neurological Disease | 1.0% | 0.0% |

| PVD | 1.2% | 1.4% |

| Diabetes | 6.3% | 5.2% |

| Depression | 20.7% | 22.8% |

| Anxiety or Panic Disorder | 14.4% | 14.4% |

| Degenerative Disc Disease | 13.4% | 13.9% |

| Obesity | 17.6% | 14.6% |

| Upper GI Disease | 17.7% | 13.8% |

Table 2.

Sample Breast Cancer Specific Health History/Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total Sample (n = 1527) M (SD) | Accel Group (n= 370) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 49.42 (8.99) | 49.74 (8.96) |

| Time Since Diagnosis (months) | 86.48 (71.59) | 85.82 (65.46) |

| Breast Cancer Stage | ||

| 0/DCIS | 19.9% | 17.9% |

| 1 | 31.1% | 30.4% |

| 2 | 32.6% | 33.6% |

| 3 | 10.0% | 11.1% |

| 4 | 2.1% | 2.2% |

| Don't Know | 4.3% | 4.9% |

| Estrogen Receptor Positive | 70.3% | 70.8% |

| Current Treatment Status | ||

| Chemotherapy | 2.6% | 2.2% |

| Radiation | 0.6% | 0.0% |

| Breast Cancer-Related Drug Therapy | 43.0% | 43.2% |

| Post-menopausal at diagnosis | 49.2% | 44.3% |

| Post-menopausal | 83.6% | 86.8% |

| Treatment History | ||

| Surgery | 99.3% | 99.7% |

| Chemotherapy | 59.0% | 60.5% |

| Radiation Therapy | 67.7% | 68.8% |

| Breast Cancer Recurrence | 10.7% | 11.1% |

| Any Other Cancer Diagnosis | 15.2% | 14.9% |

| Family History of Breast Cancer | 51.0% | 53.7% |

Model Results

Table 3 contains the means, standard deviations, and t-values for each of the factors in the social cognitive model of physical activity. Briefly, over the six month study period, women experienced a significant (p < 0.05) decline in exercise self-efficacy, fatigue severity, fatigue interference, physical, social and self-evaluative outcome expectations, family and friend social support and physical activity. Fatigue duration significantly increased while barriers self-efficacy and goals did not change over the 6-month study period.

Table 3.

Descriptives of SCT Model Constructs at Baseline and 6 months

| FSI-Duration | 2.79 | 2.05 | 2.93 | 2.14 | 4.35* |

| MOEES-PO | 28.07 | 2.81 | 27.74 | 3.07 | −3.51* |

| MOEES-SEO | 22.37 | 2.99 | 22.04 | 3.18 | −3.99* |

| MOEES- SO | 12.44 | 3.28 | 11.92 | 3.46 | −5.14* |

| SSE-Family | 25.21 | 10.28 | 23.43 | 10.10 | −8.41* |

| SSE-Friends | 22.42 | 10.10 | 22.42 | 9.64 | −5.40* |

| EGS | 2.50 | 1.30 | 2.50 | 1.35 | −0.30 |

| GLTEQ | 30.47 | 21.87 | 29.64 | 21.86 | −2.15* |

| Accel | 25,2219.97 | 16,9805.00 | 21,2765.22 | 9,7755.46 | −4.96* |

Note. All values listed are for the full sample (N= 1,527) except for the accelerometer data which is only for the 370 individuals with valid data. BARSE= Barriers Self-efficacy Scale; EXSE= Exercise Self-efficacy Scale; FSI= Fatigue Symptom Inventory; MOEES= Multidimensional Outcome Expectations for Exercise Scale; PO= Physical Outcome Expectations; SEO= Self- evaluative outcome expectations; SO= Social Outcome Expectations; SSE= Social Support for Exercise; EGS= Exercise Goals Survey; GLTEQ= Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire; Accel= Average Accelerometer Activity Counts

significant at p=<.05

Full sample

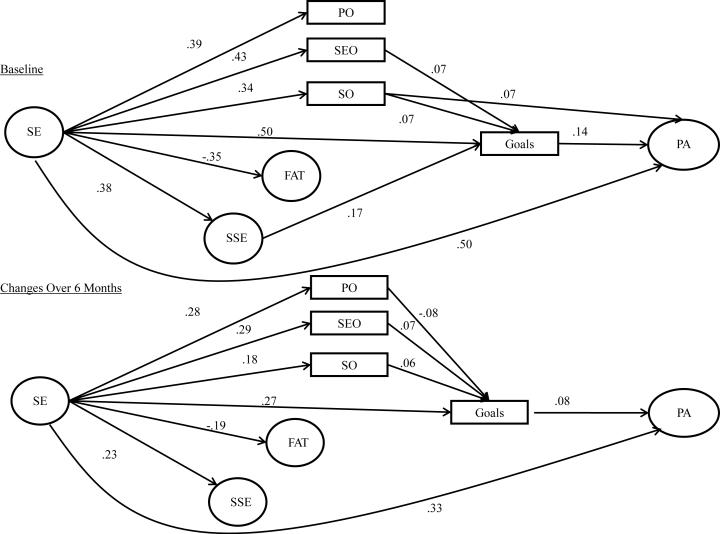

This model provided an acceptable overall fit to the data (Х2 = 1974.48, df = 273, p = < 0.001; CFI= 0.92; SRMR= 0.05). However, a specification search indicated correlating baseline SSE family subscale and BARSE values with their respective 6 month follow-up values would substantially improve the fit of the model and was in-line with SCT. Adding these relationships resulted in a good fitting model (χ2 = 1168.73, df= 271, p= <.001; CFI=.96; SRMR = 0.04). This model is shown in Figure 1. Overall, the stability coefficients were acceptable and ranged from 0.36 (physical outcome expectations) to 0.90 (social support). The stability coefficients and bi-directional correlations have been omitted from the figure for clarity.

Figure 1.

Social Cognitive Model of Physical Activity Behavior in the Entire Study Sample. Significant paths are represented by solid lines. Non-significant paths and stability coefficients were not included for clarity purposes. SE= Self-efficacy; FAT= Fatigue; SSE= Social Support for Exercise; PO= Physical Outcome Expectations; SEO= Self-evaluative Outcome Expectations; SO= Social Outcome Expectations; PA= Physical Activity

At baseline, more efficacious breast cancer survivors had significantly (p < 0.05) higher physical (β = 0.39), self-evaluative (β = 0.43) and social (β = 0.34) outcome expectations, social support (β = 0.38), goal-setting (β = 0.51), and physical activity (β = 0.50) and lower fatigue (β = -0.35). Women with higher social outcome expectations participated in more physical activity (β = 0.07), and those with higher social (β = 0.07) and self-evaluative (β = 0.07) outcome expectations and social support (β = 0.17) engaged in more goal setting. In turn, women who engaged in more goal-setting had higher physical activity levels (β = 0.14). Self-efficacy had a significant indirect influence physical activity via goals and social outcome expectations. Additionally, the indirect paths via self-evaluative and social outcome expectations and goals, independently, and social support and goals were also significant.

At 6-month follow-up, breast cancer survivors whose self-efficacy increased also had significant increases in physical (β = 0.28), self-evaluative (β = 0.29), and social (β = 0.18) outcome expectations, social support for exercise (β = 0.23), goal-setting behavior (β = 0.27) and physical activity (β = 0.33) while experiencing declines in fatigue (β = -0.19). Increases in goal setting behavior were associated with increases in physical activity (β = 0.08), and women who had increased social (β = 0.06) and self-evaluative (β = 0.08) outcome expectations engaged in more goal setting while the opposite was true for those whose physical outcome expectations (β = - 0.08). There were statistically significant indirect paths between residual changes in self-efficacy and residual changes in physical activity via goals, alone, and via the paths between self-efficacy and physical activity involving social and physical outcome expectations. In addition, the indirect paths from self-efficacy to physical activity via social and physical outcome expectations, independently, were also significant. Table 4 shows the relationship among model constructs and the covariates included in the model. Overall, the model accounted for 41.1% and 49.0% of the variance in physical activity at baseline and follow-up, respectively.

Table 4.

Relationship of Model Variables to Covariates

| Age | Income | Education | BMI | # of Comorbid Conditions | Disease Stage | Time Since Diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||||||

| SE | 0.09* | 0.08* | 0.07* | −0.25* | −0.20* | −0.09* | −0.02 |

| EGS | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.08* | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| FAT | −0.19* | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.06* | −0.12* |

| SOC SUPP | −0.11* | 0,04 | 0.06* | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| MOEES-PO | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| MOEES-SEO | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.08* | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.01 |

| MOEES-SO | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| GLTEQ | −0.12* | −0.05 | 0.07* | −0.05* | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.07* |

| Changes over6 months | |||||||

| SE | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| EGS | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 |

| FAT | −0.07* | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| SOC SUPP | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| MOEES-PO | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06* | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 |

| MOEES-SEO | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.04 | −0.06 |

| MOEES-SO | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.05* |

| GLTEQ | −0.07* | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05* | 0.00 | −0.04* | 0.00 |

Note: Above values are P-values for the full sample;

indicates a significant relationship at p<.05; SE= latent self-efficacy variable; EGS= Exercise Goals Scale; FAT = latent fatigue variable; SOC SUPP= lattent support variable, MOEES= multidimentional Outcome Expectation for Exercise Scale; PO= physical Outcome Expectation; SEO= self-evaluative outcome expectation; SO=Social Outcome Expectation; GLTEQ= Godin leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire

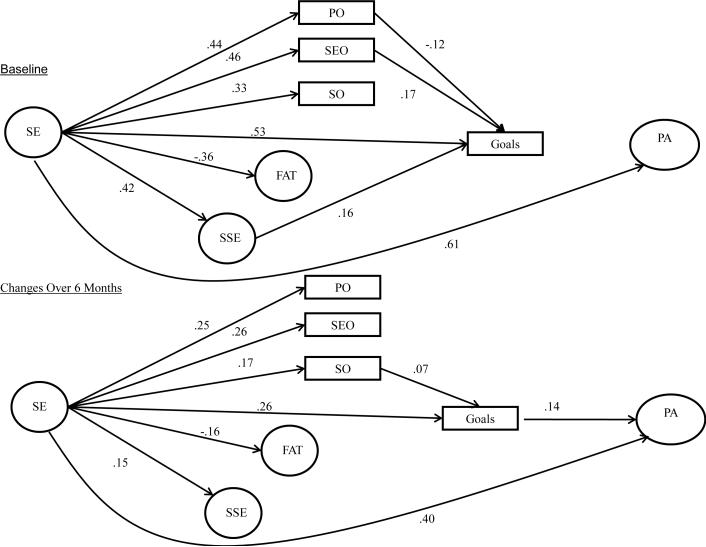

Accelerometer Subgroup

The final model tested the hypothesized relationships in the accelerometer subsample when controlling for covariates. This model provided an adequate fit to the data (χ2 = 656.88, df = 330, p = 0.00, CFI = 0.95, SRMR= 0.05). Results from this model are shown in Figure 2 and are very similar to those in the whole sample. However, at baseline, the relationships between goals and physical activity and social outcome expectations and physical activity were not significant. At follow-up, the direct relationships between social outcome expectations and goals and social support and goals were no longer significant. Additionally, the only statistically significant indirect path in the model was via goals at both baseline and follow-up. Overall, this model account for 43.4% of the variance in physical activity at baseline and 89.4% of the variance for changes in physical activity across the 6-month period.

Figure 2.

Social Cognitive Model of Physical Activity Behavior in the Subsample with Accelerometer Data. Significant paths are represented by solid lines. Non-significant paths and stability coefficients were not included for clarity purposes. SE= Self-efficacy; FAT= Fatigue; SSE= Social Support for Exercise; PO= Physical Outcome Expectations; SEO= Self-evaluative Outcome Expectations; SO= Social Outcome Expectations; PA= Physical Activity

DISCUSSION

This study provides at least initial support for a SCT model of physical activity behavior in longer term breast cancer survivors using the structural pathways proposed by Bandura [16]. Self-efficacy was the strongest predictor of physical activity behavior, a finding consistent with other studies in breast cancer survivors [23] and the general adult population [21]. Furthermore, this study provides support for the often ignored indirect relationship between self-efficacy and physical activity as self-efficacy also exhibited a significant indirect relationship with physical activity via goals and outcome expectations. These findings support the position that more efficacious breast cancer survivors have higher outcome expectations and are better able to self-regulate their behavior resulting in greater physical activity participation.

Overall, goals were the most consistent, indirect predictor of physical activity participation in this study in both the full sample and the accelerometer subsample such that more efficacious breast cancer survivors set higher goals for themselves which resulted in greater physical activity participation. However, the direct relationship between goals and physical activity did not hold at baseline in the accelerometer subsample. This could be a function of the measures used, as the goals measure was assessing exercise-related goals while accelerometer activity captures all of the activity in which an individual engages. For example, some women could have low exercise-related goal setting but still participate in considerable lifestyle physical activity. This inconsistency may not be as prevalent with the self-reported GLTEQ as those individuals who score low on the EGS would also most likely score low on the GLTEQ. Alternatively, since the relationship between goals and latent physical activity did hold at follow-up, these findings could be the result of a novelty effect that resulted in increased physical activity participation at baseline when the monitor was worn for the first time but did not occur at follow-up when the novelty of wearing the monitor had worn off.

The role of outcome expectations as a direct mediator between self-efficacy and physical activity was only supported for social outcome expectations at baseline in the full sample. Additionally, the role of outcome expectations as a mediator between self-efficacy via goals was only supported in the full sample. Bandura [17] has previously noted that the influence of outcome expectations on behavior may be reduced to a redundant predictor as a result of the strength of the relationship between self-efficacy and the behavior in question. Thus, regardless of whether breast cancer survivors have high outcome expectations, more efficacious women may be more likely to be active. Social outcome expectations had the most consistent relationship with goal setting indicating that individuals who expected social benefits from physical activity were more likely to regulate their behavior. Breast cancer survivors with higher social outcome expectations may have more social support for exercise or be more likely to engage in group activities, both of which could require more self-regulation as a result of regularly scheduled pre-arranged meeting times.

Although fatigue is a commonly identified barrier to physical activity in breast cancer survivors [51-53], we found no support for a direct relationship between fatigue and goals or for its role as a mediator between self-efficacy and physical activity participation. This is likely due to the low levels of fatigue reported, relatively high average length of time since diagnosis and the fact that most women were not actively receiving treatment for breast cancer. Fatigue is likely to be more problematic for individuals who are close to diagnosis and actively receiving treatment.

Finally, both models tested provided some evidence to suggest social support, a facilitator of physical activity behavior, may influence goal-setting at baseline. However, this relationship did not hold across time, and support for the role of social support as a mediator between self-efficacy and physical activity participation via goals was only present when using a self-reported measure of physical activity. Thus, although social support may help to motivate individuals to self-regulate their physical activity behavior initially, social outcome expectations appear to be more important in motivating individuals to self-regulate their behavior across time, especially if social support is already in place.

The results from this study have important implications for advancing the understanding of physical activity behavior in breast cancer survivors, as well as for designing effective physical activity behavior change interventions for this population. Although some of the significant effects observed between the model constructs (self-efficacy, goal-setting, social support and outcome expectations) and physical activity were modest in magnitude, they could still have a large public health impact [54] as they are all modifiable. Targeting these constructs in program design could be relatively low cost, but have substantial pay-offs in terms of physical activity participation and the health and disease-related outcomes associated with this behavior. Self-efficacy could be targeted by: (a) designing progressive interventions that allow for success before advancing (mastery experiences); (b) using active breast cancer survivors as exercise leaders (vicarious experiences); (c) conducting programs in a group setting (social persuasion); and (d) educating breast cancer survivors on how their body should respond to exercise (interpretation of physiological and psychological states). Goal-setting could be targeted by educating women on ways to self-regulate their behavior (e.g., scheduling physical activity, writing down goals), as well as incorporating these strategies into intervention design (e.g., regularly scheduled meeting times, physical activity logs, individualized feedback). Additionally, educating breast cancer survivors’ about realistic outcome expectations for physical activity as well as incorporating social support through group activities or exercise “buddies” may also have beneficial outcomes on physical activity participation.

Although we believe the results of this study are promising, we must acknowledge several limitations. First, this study adopted a longitudinal observational design and our timeframe of 6 months was somewhat arbitrary. Longer-term longitudinal studies and randomized controlled exercise trials will be needed to determine how the proposed relationship among changes in model constructs hold across longer periods of time and as a result of an intervention. Second, although no restrictions were placed on disease characteristics or time since diagnosis, the sample was relatively homogenous and may not be entirely representative of this population at large. Thus, it is important to examine whether these models can be replicated in other, more diverse samples of breast cancer survivors or within subgroups of this population. (e.g., survivors within 5 years of diagnosis compared to longer term survivors, older and younger survivors, obese and non-obese survivors). Additionally, there was no relationship between fatigue and any model variables except for self-efficacy. Thus, testing whether other, potentially more salient, barriers (e.g., functional status, depression) are related to physical activity participation in this population may be warranted. Finally, results were not entirely consistent across the two models using different methods to assess physical activity. This is not unique to this particular study and suggests that physical activity measurement issues may play a role in our understanding of the relationships examined in this study and other relationships in the literature. Future studies should explore these issues and develop well-defined standards of practice for physical activity measurement in order to enhance the quality of data available to inform the implementation of effective programs and interventions.

In conclusion, this study remains one of the largest, nationally representative longitudinal studies of physical activity in longer term breast cancer survivors to date. It is one of the few studies that has been conducted in this population incorporating an objective measure of physical activity. Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, this is the only study that has examined the influence of several social cognitive constructs on physical activity participation in breast cancer survivors simultaneously. These data provide an important step forward in understanding physical activity participation in breast cancer survivors and can inform future research and programming to enhance survivorship.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by award #F31AG034025 from the National Institute on Aging awarded to Siobhan M. (White) Phillips and a Shahid and Ann Carlson Khan endowed professorship awarded to Edward McAuley who is also supported by grant #AG020118 from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Neither of the authors have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERNCES

- 1.Kirshbaum M. A review of the benefits of whole body exercise during and after treatment for breast cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2006;16:104–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01638.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, et al. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2006;175:34–41. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051073. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.051073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milne HM, Gordon S, Guilfoyle A, et al. Association between physical activity and quality of life among Western Australian breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2007;16:1059–1068. doi: 10.1002/pon.1211. DOI: 10.1002/pon.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfano CM, Smith AW, Irwin ML, et al. Physical activity, long-term symptoms, and physical health-related quality of life among breast cancer survivors: A prospective analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:116–128. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0014-1. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedenreich CM, Gregory J, Kopciuk KA, Mackey JR, Courneya KS. Prospective cohort study of lifetime physical activity and breast cancer survival. Int J Cance. 2009;124:1954–1962. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24155. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.24155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holick CN, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Physical activity and survival after diagnosis of invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:379–386. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0771. DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, et al. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293:2479–2486. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. DOI:10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinto BM, Trunzo JJ, Reiss P, et al. Exercise participation after diagnosis of breast cancer: Trends and effects on mood and quality of life. Psychooncology. 2002;11:389–400. doi: 10.1002/pon.594. DOI: 10.1002/pon.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irwin ML, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, et al. Physical activity levels among breast cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1484–1491. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devoogdt N, Van Kampen M, Geraerts I, et al. Physical activity levels after treatment for breast cancer: One-year follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:417–125. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0997-6. DOI: 10.1007/s10549-010-0997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Littman AJ, Tang M-T, Rossing MA. Longitudinal study of recreational physical activity in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:119–127. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0113-2. DOI: 10.1007/s11764-009-0113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Irwin ML, Crumley D, McTiernan A, et al. Physical activity levels before and after a diagnosis of breast carcinoma: The Health, Eating, Activity, and Lifestyle (HEAL) study. Cancer. 2003;97:1746–1757. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11227. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.11227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Physical activity and cancer control. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23:242–252. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2007.08.002. DOI:10.1016/j.soncn.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dzewaltowski DA, Noble JM, Shaw JM. Physical activity participation: Social cognitive theory versus the theories of reasoned action and planned behavior. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 1990;12(4):388–405. doi: 10.1123/jsep.12.4.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandura A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1986;4:359–4373. DOI: 10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. DOI: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W.H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajzen I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior. Dorsey Press; Chicago: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Beha Hum Decis Process 5. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAuley E, Blissmer B. Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2000;28:85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, et al. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: Review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1996–2001. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020. DOI:10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rogers LQ, Shah P, Dunnington G, et al. Social cognitive theory and physical activity during breast cancer treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:807–815. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.807-815. DOI:10.1188/05.ONF.807-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers LQ, McAuley E, Courneya KS, et al. Correlates of physical activity self-efficacy among breast cancer survivors. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32:594–603. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.6.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart AL, King AC. Evaluating the efficacy of physical activity for influencing quality-of-life outcomes in older adults. Ann Behav Med. 1991;13:108–116. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams DM, Anderson ES, Winett RA. A review of the outcome expectancy construct in physical activity research. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29:70–79. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2901_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nothwehr F, Yang J. Goal setting frequency and the use of behavioral strategies related to diet and physical activity. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:532–538. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl117. DOI:10.1093/her/cyl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dishman RK, Vandenberg RJ, Motl RW, et al. Dose relations between goal setting, theory-based correlates of goal setting and increases in physical activity during a workplace trial. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:620–631. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp042. DOI:10.1093/her/cyp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Relationship between exercise during treatment and current quality of life among survivors of breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1997;15:35–57. DOI:10.1300/J077v15n03_02. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Gelmon K, et al. Predictors of supervised exercise adherence during breast cancer chemotherapy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(6):1180–1187. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318168da45. DOI:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318168da45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bassett DR, Ainsworth BE, Swartz AM, et al. Validity of four motion sensors in measuring moderate intensity physical activity. Med Sci Sport Exer. 2007;32:S471–S480. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00006. DOI:10.1097/00005768-200009001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tudor-Locke C, Ainsworth BE, Thompson RW, et al. Comparison of pedometer and accelerometer measures of free-living physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:2045–2051. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00027. DOI:10.1097/00005768-200212000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Focht BC, Sanders WM, Brubaker PH, Rejeski WJ. Initial validation of the CSA activity monitor during rehabilitation exercise among older adults with chronic disease. J Aging Phys Act. 2003;11:293–304. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes DC, Baum GP, Carmack C, Greisinger AJ, Basen-Engquist K. Accelerometry and self-report in sedentary populations. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35:71–80. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.35.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motl RW, McAuley E, Snook EM, Scott JA. Validity of physical activity measures in ambulatory individuals with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:1151–1156. doi: 10.1080/09638280600551476. DOI:10.1080/09638280600551476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trost SG, McIver KL, Pate RR. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:S531–S543. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98. DOI:10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McAuley E. Self-efficacy and the maintenance of exercise participation in older adults. J Behav Med. 1993;16:103–113. doi: 10.1007/BF00844757. DOI:10.1007/BF00844757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wójcicki TR, White SM, McAuley E. Assessing outcome expectations in older adults: The multidimensional outcome expectations for exercise scale. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:33–40. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbn032. DOI: 10.1093/geronb/gbn032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rovniak LS, Anderson ES, Winett RA, et al. Social cognitive determinants of physical activity in young adults: A prospective structural equation analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:149–156. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_12. DOI:10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Azzarello LM, et al. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: Development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:301–310. doi: 10.1023/a:1024929829627. DOI: 10.1023/A:1024929829627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, et al. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med. 1987;16:825–836. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. DOI:10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus (Version 5.0) Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arbukle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulide GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Techniques. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah: 1996. pp. 243–278. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enders C, Bandalos D. The relative performance of Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. DOI:10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychol Methods. 2001;6:352–370. DOI:10.1037//1082-989X.6.4.352-370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kessler RC, Greenberg DF. Linear Panel Analysis: Models of Quantitative Change. Academic Press; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8: User's Reference Guide. Scientific Software International; Chicago: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Sage; Newbury Park: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. Doi:10.1080/10705519909540118. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. DOI:10.1037//0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: Occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:743–753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Reid RD, et al. Predictors of follow-up exercise behavior 6 months after a randomized trial of exercise training during breast cancer chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9987-3. DOI:10.1007/s10549-008-9987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Shah P, et al. Exercise stage of change, barriers, expectations, values and preferences among breast cancer patients during treatment: A pilot study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16:55–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00705.x. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeffery RW. Risk behaviors and health. Contrasting individual and population perspectives. Amer Psychol. 1989;44:1194–1202. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.9.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]