Abstract

Background:

The Pulmonary Function Tests are important for measuring the fitness of an individual from a physiological point of view. Lung function parameters tend to have a relationship with lifestyle such as regular yoga, an ancient system of Indian Philosophy. Yoga is probably the best lifestyle ever devised in the history of mankind. Hence the present analytical study was undertaken to assess the effects of yoga on respiratory system when compared with sedentary subjects.

Objective:

To compare the pulmonary function test among the yogic and sedentary groups.

Materials and Methods:

The present study was conducted on 50 subjects practicing yoga and 50 sedentary subjects in the age group of 20-40 years. They were assessed for pulmonary function test in which sedentary group acted as controls. The tests which were recorded as per standard procedure using Medspiror as determinants of pulmonary function were FVC, FEV1, FEV3, PEFR and FVC/FEV1 ratio.

Results:

Pulmonary Functions were compared between the yoga practitioners and sedentary group. Yoga exercise significantly increased chest wall expansion as observed by higher values of pulmonary functions compared with sedentary controls. The study group were having higher mean of percentage value of FVC 109.1 ± 18.2%, FEV1 of 116.3 ± 15.9%, FEV3 of 105.7 ± 14.9 %, PEFR of 109.2 ± 21.3% and FEV1/FVC ratio of 111.3 ± 6.9% as compared to sedentary group.

Conclusions:

Regular Yoga practice increases the vital capacity, timed vital capacity, maximum voluntary ventilation, breath holding time and maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressures.

Keywords: Medspiror, pulmonary function test, sedentary, yoga

INTRODUCTION

Yoga is a mind and body practice with historical origins in ancient Indian philosophy. It is the science of simple living that balances all aspects of life – the physical, mental, emotional, psychic and spiritual. By the practice of asana, pranayama, mudra, bandha, shuddhi kriyas and meditation yoga, helps balance and harmonize the body, mind and emotions.[1] Classical literature on yoga indicates that it is of great value as a method of preservation of health and treatment of various diseases. Yoga practice consists of the five-principle including proper relaxation, proper exercise, proper breathing, proper diet and positive thinking and meditation. Yoga respiration consists of very slow, deep breaths with sustained breath hold after each inspiration. Practicing yoga contributes in the improvement of pulmonary ventilation and gas exchange. It also helps in the prevention, cure and rehabilitation of patients with respiratory illnesses by improving ventilatory functions.[2,3] It is a popular form of exercise in India since ancient times and yoga's effects on pulmonary function have been investigated previously.

Pulmonary function tests (PFT) serve as a tool of health assessment and also to some extent as a predictor of survival rate. PFT tend to have a relationship with life-style such as regular exercise and non-exercise.[4,5] Spirometry is pivotal to the screening, diagnosis and monitoring of respiratory diseases and is increasingly advocated in primary care practice. Due to regular yogic exercise, yoga practitioners tend to have an increase in pulmonary capacity when compared with no yoga practitioners. Pulmonary functions are generally determined by the strength of respiratory muscles, compliance of the thoracic cavity, airway resistance and elastic recoil of the lungs.[6] PFT provide qualitative and quantitative assessment of pulmonary function in patients with obstructive and restrictive lung diseases. The tests used to describe pulmonary function are the lung volumes and lung capacities. It is well-known that pulmonary functions may vary according to the physical characteristics including age, height, body weight and altitude. The practice of yoga is accompanied by a number of beneficial physiological effects in the body. Regular practice of yoga is known to improve overall performance and working capacity.[7] Current evidence suggests that following regular practice of yoga there is an improvement in cardiovascular and pulmonary functions.[8]

The pulmonary function capacities of normal sedentary individuals have been studied extensively in India[9,10,11] but less in the context of comparison with yogic population practicing yoga. Furthermore, such comparative studies have not been done in this part of the country. Some researchers have done a non-comparative study and others on a non-randomized sample.[12,13] Review of literature from India showed that only few comparative studies were done on a small sample of yoga practitioners with a control group as athletes or non-yoga practitioners. Other studies were either non-comparative or done only on females. Hence the present comparative study was undertaken on a large randomly selected sample of yoga practitioners and compared with matched control of sedentary group. This study tested the hypothesis that yoga training improved chest wall expansion and lung volumes in young healthy adults when compared to sedentary adults without yoga training.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study population comprised of yoga practitioners as the study group and sedentary subjects as the control group selected randomly from the urban area of Kurnool town. Present study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. Informed written consent was taken from the subjects that met the inclusion criteria of the study. The study group consisted of those practicing pranayama, yoga sana and other yogic techniques for at least 1 h/day for more than 6 months. Sedentary group comprised subjects not practicing yoga and a leisure-time physical activity or activities done for less than 20 min or fewer than 3 times/week. A list of 112 people practicing yoga at the Yoga Kendra was obtained. 50 subjects were randomly selected by simple random method from the list of Yogabhyasi at the Yoga Kendra in the city. For each subject in the study group, a similar subject matched for age and gender was identified from urban population aged between 20 and 40 years, non-obese and willing to participate in the study. All subjects in both groups were non-smokers and free from active respiratory diseases. The control group consisted age and gender matched sedentary subjects from the urban area. Smokers (cigarettes, beedies, chutta and tobacco chewing), subjects with active respiratory disorders, epileptic disorders and those not willing to participate in the study were excluded.

The PFT were carried on all these subjects as per the procedure and guidelines mentioned by Miller et al.[14] After explaining the procedure in local language to each subject, informed consent was obtained. The test was carried out in a well-ventilated spacious room with ambient temperature ranging from 28°C to 35°C respectively. Measurements of PFT were taken between 8 am and 12 noon to avoid diurnal variations in lung functions. The tests were carried by a well-trained doctor familiar with Medspiror (computerized spirometry) after reinforcing the method of a test to each subject. Further, study subjects undergoing the tests were well-informed about the instrument and the technique of test by demonstrating the procedure. The five tests of pulmonary function were taken into consideration and the values obtained were recorded. The best value from three measurements was considered after recording by a spirometer. Predicted values were calculated by the standard formulae originally programmed in the spirometer. The tests chosen were:

Percentage of forced vital capacity (%FVC)

Percentage of forced expiratory volume in 1st s (%FEV1)

Percentage of FEV in 3 s (%FEV3)

Percentage of peak of expiratory flow rate (%PEFR)

Percentage of FEV1/FVC ratio.

Percentage of predicted FVC (%FVC), FEV1 (%FEV1), FEV3 (%FEV3), PEFR (%PEFR) and FEV1/FVC ratio (%FEV1/FVC) were analyzed for both study (yoga practitioners) and control (sedentary) group.

Anthropometric measurements like height and weight of each subject was measured before the test procedure. Weight was recorded in kilograms (kg) and recorded to the nearest 0.5 kg. Height was measured in centimeters (cm) while standing and the reading was taken to the nearest 0.5 cm. Information was collected regarding the socio-demographic data, smoking history, recent respiratory illness, medications used and about the family history of any bronchial asthma. A detailed clinical examination was done to exclude any cases with respiratory and systemic disorders.

Data analysis

Data after collection was entered on Microsoft Excel spread sheet and analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software. The data was checked for normal distribution. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for quantitative data. All values are presented as mean ± SD. Comparison of mean values between the two groups was done using unpaired t-test for significance. All statistical tests were two-tailed and P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

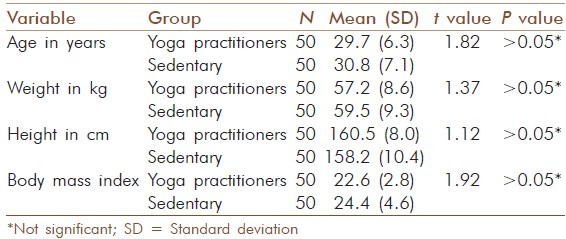

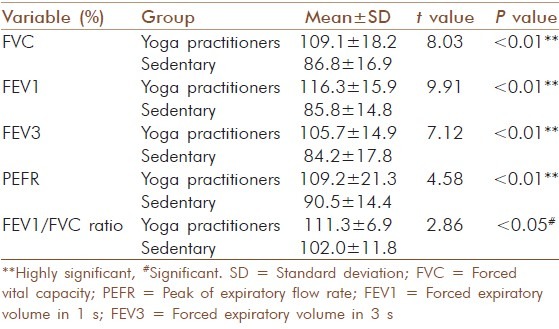

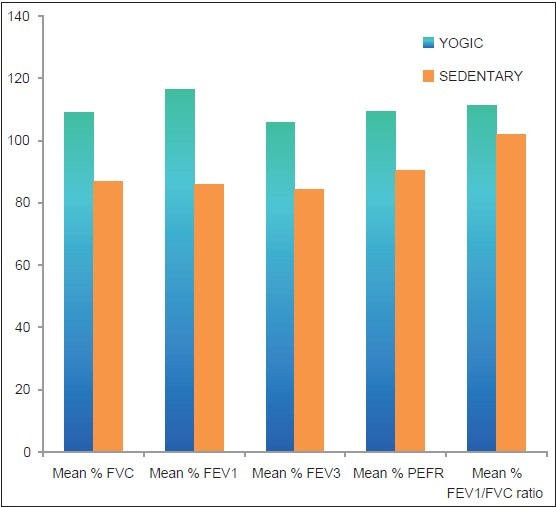

The present comparative study consisted of 100 subjects that formed two different groups namely study group consisting yoga practitioners (50 subjects) and control group comprising sedentary subjects (50 subjects). The mean age and mean anthropometric measurements of both groups have been depicted in Table 1. These findings suggest that both groups were statistically similar and hence were comparable. The gender wise distribution of subjects had equal representation of both sexes in each group. Values of percentage of predicted FVC (%FVC), FEV1 (%FEV1), FEV3 (%FEV3), PEFR (%PEFR) and FEV1/FVC ratio (%FEV1/FVC) are expressed as mean (%) ± SD and the results are shown in Table 2. Mean percentage of predicted FVC of the study group was higher compared with sedentary subjects and the difference was found to be statistically significant. Similarly, it was found that mean of %FEV1 of the study group (116.3 ± 15.9) was significantly higher than that of sedentary group (85.8 ± 14.8). Statistically significant difference was observed in the mean percentage of predicted FEV1 values of both groups. Mean %FEV3 was also higher in the study group when compared to sedentary group and this difference in the mean values between them was statistically significant. The mean percentage of predicted PEFR was 109.2 ± 21.3 in the study group and 90.5 ± 14.4 in the sedentary group. The higher mean of %PEFR observed among the study group when compared to sedentary group was statistically significant which is also shown graphically in Figure 1. The mean percentage of FEV1/FVC ratio also showed a significant difference with higher mean value in the study group than sedentary group. All these findings are shown by a bar diagram in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants

Table 2.

Pulmonary function test variables between the two groups

Figure 1.

Graph showing comparison of pulmonary function test variables in two groups

DISCUSSION

In the present study, significantly higher values of pulmonary functions were observed among subjects practicing yoga as compared to sedentary subjects who did not practice yoga. The group practicing yoga exhibited better pulmonary function status when compared with sedentary subjects. It was observed that the mean of %FVC for yoga practitioners was 109.1 and for sedentary subjects were 86.8. This clearly showed that the subjects who were practicing yoga since last 6 months had better FVC values than the sedentary subjects. Similarly Prakash et al.[15] have reported that the mean FVC value for yoga practitioners was 98 whereas in sedentary subjects the values were lower and they are in agreement with the present study. Joshi et al. in their study also observed a significant increase in FVC after pranayam practice.[16] Yadav and Das[2] in their study also observed that there was a significant increase in FVC among the subjects exposed to yogic exercises for 12 weeks. The changes in the FVC values depend upon the duration of yoga training.

With reference to %FEV1 the second test studied, the values in yoga practitioners were much better when compared with sedentary subjects. When study and sedentary groups are compared, results showed higher FEV1 in yoga practitioners as reported by other studies[15,17] while Khanam et al.[18] did not observe any significant change in FEV1. Yadav and Das[2] in their study observed that FEV1 was significantly higher at 6 weeks and 12 weeks of yoga training. The present study also showed highly significant values of FEV3 among yoga practitioners suggesting that the yoga practice does have an influence on FEV3. Yoga training increases strength of respiratory muscles contributing to improvement in pulmonary functions.[19]

Many authors emphasized the importance of PEFR as one of the important indicators of pulmonary function. In the present study, the mean %PEFR among yoga practitioners was 109.2 compared to sedentary group which was 90.5. The above observations revealed PEFR values in yoga practitioners were much higher than the sedentary subjects. In a study of yoga for asthmatics[20] found improvement in the peak flow rate after yoga training for 2 weeks. Yadav and Das[2] also observed a significantly higher PEFR value after 12 weeks of yoga training, but not statistically significant values after 6 weeks of training indicating that the duration of yoga training plays a role in PEFR. In contrast, Joshi et al.[16] observed a significant increase in PEFR even at 6 weeks of pranayam training with only pranayamic practice lasting for 20 min twice a day. Khanam et al.[18] did not observe any significant change in other lung function tests but for PEFR. The higher PEFR among yoga practitioners could be explained based on the fact that they have better strengthening of respiratory muscles. Repeated inspiration and expiration to improve total lung capacity and breathe holding as done during pranayam can lead to maximal shortening of the inspiratory muscles which have been shown to improve the lung functions and many authors were in agreement with this.

The FEV1/FVC ratio when coupled with other test could be used as a predictor of obstructive and restrictive patterns of lung disorders. In the present study, the mean %FEV1/FVC among yoga practitioners was higher (113.3) than sedentary (102.0). Vital capacity is determined by the lung dimensions, compliance and respiratory muscle power, whereas PEFR is determined mainly by airway caliber, alveolar elastic recoil and respiratory muscle effort. Pranayama is characterized by slow and deep inhalation and exhalations. It is said to be the main breathing exercise causing an increase in breath holding time. Udupa et al.[21] in their study stated that pranayama also trains the respiratory centers to suspend the breath for quite a long time. The stress is more on prolonged expiration and efficient use of abdominal and diaphragmatic muscles. This act trains respiratory apparatus to get emptied and filled more completely and efficiently which is recorded in terms of vital capacity. Soni et al.[22] found significant improvement in FVC, FEV1, maximum voluntary ventilation and PEFR after pranayama practice in asthmatic patients. Similarly Chibber et al.[23] found significant increase in FVC, FEV1% and PEFR at 6th and 12th week of pranayama practice in healthy females.

Improvement in vital capacity among yoga practitioners in the present study may be due to increase in the development of respiratory musculature incidental to regular practice of yoga. The findings of the present study can also be explained on the basis of better functions of respiratory muscle strength, improved thoracic mobility and the balance between lung and chest elasticity which the yoga practitioners may have gained from regular yoga. The other possible mechanism for improved PFT in yoga practitioners as mentioned by Yadav and Das[2] are:

Increased power of respiratory muscles that is due to the work hypertrophy of the muscles during yoga and other exercises

Yogic breathing exercises train practitioners to use the diaphragmatic and abdominal muscles more efficiently thereby emptying and filling the respiratory apparatus more efficiently and completely.

The present study also showed that the sedentary group had lowest values of pulmonary function compared to yoga practitioners. Sedentary life-style is associated with development of restrictive lung function. We recommend that sedentary people should adopt yogic exercises for improving their health. Hence regular practice of yoga should be promoted among the sedentary subjects that may bring desirable physiological, psychological and physical changes in the individual.

CONCLUSION

This study agrees with previous reports and supports the health benefits of yoga. The study revealed that the sedentary subject's performance on PFT was poorer when compared with yoga practitioners. This emphasizes the need to change their life-style and adopt measures like yoga regularly to be healthy. Regular practice of yoga produces a positive effect on the lung that is reflected in improvement of pulmonary capacities. The present study suggests that short-term yoga exercise improves respiratory breathing capacity by increasing chest wall expansion and forced expiratory lung volumes. The data from the study provide more scientific evidence to support the beneficial effect of yoga practice on respiration and muscle strength. This resultant effect of yoga on lung functions can be used as lung strengthening tool to treat many lung diseases such as asthma, allergic bronchitis, post-pneumonia recoveries, tuberculosis and many occupational diseases. The knowledge so gained of the respiratory functions through spirometry can be utilized for promoting yoga among the sedentary adults and the betterment of the population.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Saraswati SS. Introduction to yoga. In: Saraswati SS, editor. Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. 4th ed. Munger, Bihar, India: Yoga Publication Trust; 2008. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yadav RK, Das S. Effect of yogic practice on pulmonary functions in young females. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001;45:493–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adanmohan, Udupa K, Bhavanani AB, Vijayalakshmi P, Surendiran A. Effect of slow and fast pranayams on reaction time and cardiorespiratory variables. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;49:313–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wassermann K, Gitt A, Weyde J, Eckel HE. Lung function changes and exercise-induced ventilatory responses to external resistive loads in normal subjects. Respiration. 1995;62:177–84. doi: 10.1159/000196444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Twisk JW, Staal BJ, Brinkman MN, Kemper HC, an Mechelen W. Tracking of lung function parameters and the longitudinal relationship with lifestyle. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:627–34. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12030627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotes JE. Lung Function: Assessment and Applications in Medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madanmohan, Udupa K, Bhavanani AB, Shatapathy CC, Sahai A. Modulation of cardiovascular response to exercise by yoga training. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;48:461–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bera TK, Rajapurkar MV. Body composition, cardiovascular endurance and anaerobic power of yogic practitioner. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1993;37:225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain SK, Ramiah TJ. Normal standards of pulmonary function tests for healthy Indian men 15-40 years old: Comparison of different regression equations (prediction formulae) Indian J Med Res. 1969;57:1453–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Chaganti S, Jindal SK. Diurnal variation in peak expiratory flow in healthy young adults. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2000;42:15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta P, Gupta S, Ajmera RL. Lung function tests in Rajasthani subjects. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1979;23:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doijad VP, Surdi AD. Effect of short term yoga practice on pulmonary function tests. Indian J Basic Appl Med Res. 2012;3:226–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shankarappa V, Prashanth P, Nachal A, Malhotra V. The short term effect of pranayama on the lung parameters. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. ATS/ERS task force. Standardization of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prakash S, Meshram S, Ramtekkar U. Athletes, yogis and individuals with sedentary lifestyles; do their lung functions differ? Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;51:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi LN, Joshi VD, Gokhale LV. Effect of short term ‘Pranayam’ practice on breathing rate and ventilatory functions of lung. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;36:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makwana K, Khirwadkar N, Gupta HC. Effect of short term yoga practice on ventilatory function tests. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1988;32:202–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanam AA, Sachdeva U, Guleria R, Deepak KK. Study of pulmonary and autonomic functions of asthma patients after yoga training. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;40:318–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhavanani AB, Udupa K, Madanmohan, Ravindra P. A comparative study of slow and fast suryanamaskar on physiological function. Int J Yoga. 2011;4:71–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.85489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. Yoga for bronchial asthma: A controlled study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291:1077–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6502.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Udupa KN, Singh RH, Settiwar RM. Studies on the effect of some yogic breathing exercises (Pranayams) in normal persons. Indian J Med Res. 1975;63:1062–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soni R, Singh S, Singh KP, Gupta M. Effect of pranayama on pulmonary function test in asthamatic patients. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;52:150. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chibber R, Mondal S, Bajaj SK, Gandhi A. Comparative study on effect of pranayama and meditation on pulmonary function in healthy females. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;52:161. [Google Scholar]