Abstract

Introduction: Free radicals are implicated in several metabolic diseases and the medicinal properties of plants have been explored for their potent antioxidant activities to counteract metabolic disorders. This research highlights the chemical composition and antioxidant potential of leaf gall extracts (aqueous and methanol) of Syzygium cumini (S. cumini), which have been extensively used in traditional medications to treat various metabolic diseases.

Methods: The antioxidant activities of leaf gall extracts were examined using diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH), nitric oxide scavenging, hydroxyl scavenging and ferric reducing power (FRAP) methods.

Results: In all the methods, the methanolic extract showed higher antioxidant potential than the standard ascorbic acid. The presence of phenolics, flavonoids, phytosterols, terpenoids, and reducing sugars was identified in both the extracts. When compared, the methanol extract had the highest total phenolic and flavonoid contents at 474±2.2 mg of GAE/g d.w and 668±1.4 mg of QUE/g d.w, respectively. The significant high antioxidant activity can be positively correlated to the high content of total polyphenols/flavonoids of the methanol extract.

Conclusion: The present study confirms the folklore use of S. cumini leaves gall extracts as a natural antioxidant and justifies its ethnobotanical use. Further, the result of antioxidant properties encourages the use of S. cumini leaf gall extracts for medicinal health, functional food and nutraceuticals applications.

Keywords: Polyphenols, Plants, DPPH, Gallic acid, Metabolic diseases, Drug

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) including singlet oxygen (1O2), superoxide ion (O-2), hydroxyl ion (OH-), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are highly reactive and toxic molecules generated in cells under normal metabolic activities. High levels of ROS can cause oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, enzymes, and DNA molecules.1 Living cells possess powerful scavenging mechanisms to avoid excess ROS-induced cellular injury, but with aging and under influence of external stress, these mechanisms become inefficient leading to metabolic distress. Hence, free radicals are implicated in several metabolic diseases that include heart diseases, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, diabetes mellitus, arthritis, cancer, aging, liver disorder etc.1 The antioxidant therapy has gained an utmost importance in the treatment of these metabolic diseases. The World Health Organization in 2006 estimated that 4 billion people (i.e., 80% of the World’s population) use herbal medicines in some aspects of primary healthcare and there is a growing tendency to “Go Natural”.2 In these aspects, all around the world, the medicinal properties of plants have been investigated and explored for their potential antioxidant activities to counteract metabolic disorders, which are of high economically viable, with no side effects.3-5

Syzygium cumini Linn (family Myrtaceae), commonly known as ‘‘Jamun” is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions. S. cumini has been valued in ayurveda and unani system of medication for possessing variety of therapeutic properties, which is widely used in folk medicine for the treatment of various diseases. It consists of gall-like excrescences formed by insects on the leaves, petioles and branches of the plant by megatrioza vitensis (Kirkaldy) (Homoptera). These galls are epiphyllous, hemispherical and greenish yellow in nature. S. cummin leaf galls, commonly known as “Karkatshringi” in Sanskrit, are extensively used in ayurveda and Indian traditional medicine. Karkatshringi is used in indigenous system of medicine (ayurveda, unani and siddha) as a remedy for cough, asthma, fever, respiratory and liver disorders.4,6-8 , Karkatshringi also finds usage in the treatment of children’s ear infections, as a suppressor of haemorrhage from gums and used to suppress nosebleeding.5,9,10 Hakims consider galls useful in pulmonary infections, diarrhea and vomiting.11 The vast number of literature found in the database revealed that the various part of the S. cumini has been found to posses antimicrobial, hypoglycemic, anti-HIV, anti-inflammatory, and anti-diarrhea activity.12-17 The galls are used in some of the ayurvedic formulations like ‘Chvyanprash avaleha’, ‘KumariAsava’, ‘KumariKalp’, which are prescribed for weakness as rejuvenating agent and tonic.18 The use of leaf galls as a rejuvenator may be attributed to the antioxidant property. The ethanomedical use of galls of S. cumini as rejuvenating agent suggests that it might poses antioxidant activities. Therefore, in the present study, the antioxidant potential and phytochemical analysis of leaf galls of S. cumini were determined to exemplify its further potential development and use as drug.

Materials and methods

Materials

Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and quercetin were obtained from Qualigens, Mumbai, India. Ascorbic acid, gallic acid, quercetin, L-ascorbic acid, potassium thiocyanate, ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2-deoxyribose, thiobarbituric acid (TBA), sodium nitroprusside, N-(1-Naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, potassium hexacyanoferrate (K3Fe (CN)6), trichloroacetic acid (TCA), ferric chloride were procured from SRL Chemicals, India. All the other reagents and solvents were of analytical grade.

Plant material

Gall induced leaves of S. cumini were collected and authenticated By Dr. S. Sundararajan at center for advanced studies in biology, Jain University, Bangalore-India, and the voucher specimen (JU-RUV-73) was conserved in the herbarium. The galls were cleaned with distilled water, dried and crushed into fine powder by using electric grinder.

Preparation of extracts

The coarsely powdered gall materials were sequentially extracted with methanol (Me-OH) and aqueous solvents in soxhlet apparatus for 24 h. The extracts were evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure using a Rotavapor (Buchi Flawil, Switzerland) and a portion of the residue was used for the antioxidant assays.

Phytochemical analysis

The preliminary qualitative phytochemical analyses of carbohydrates, saponins, alkaloids, flavonoids, tixed oils and fats, phenolic and tannins, glycosides, phytosterols and triterpenoids in the extracts were carried out using the standard methods as described before. For alkaloids (Dragendroff’s reagent test), terpenoids (Noller’s test), tannins(1% lead acetate test), saponins (Foam test), flavanoids (Shinoda test), phenols (Ferric chloride test), steroids (Libermann Burchard test) etc. were conducted and the absorbance of the reaction mixtures was measured using spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan).4, 19-22

Qualitative analysis

Determination of total phenolic content

The total phenolics were determined in the S. cumini leaf gall extracts (methanol and aqueous) using Folin-Ciocalteau reagent method, employing gallic acid as standard.23 Briefly, 200 µl of both methanol and aqueous extracts (2 mg/ml) were made up to 3 ml with distilled water, then mixed thoroughly with 0.5 ml of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. After mixing for 3 min, 2 ml of 20% (w/v) sodium carbonate was added and allowed to stand for a further 60 min in the dark. The absorbance of the reaction mixtures was measured at 650 nm, and the results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/g of dry weight.

Determination of total flavonoid content

Total flavonoid content of both crude extracts and essential oils was determined using the aluminium chloride colorimetric method as described by Chang et al.24 In brief, 50 µl of methanol and aqueous extracts (2 mg/ml) were made up to 1 ml with methanol, then mixed with 4 ml of distilled water and subsequently with 0.3 ml of 5% NaNO2 solution. After 5 min of incubation, 0.3 ml of 10% AlCl3 solution was added and then allowed to stand for 6 min, followed by adding 2 ml of 1 M NaOH solution to the mixture. Then water was added to the mixture to bring the final volume to 10 ml and the mixture was allowed to stand for 15 min. The absorbance was measured at 510 nm. Total flavonoid content was calculated as quercetin from a calibration curve. The calibration curve was prepared by preparing quercetin solutions at concentrations 12.5 to 100 mg ml-1 in methanol. The result was expressed as mg quercetin equivalent (QUE)/g of dry weight.

Evaluation of in vitro antioxidant and free radical scavenging potential of S. cumini leaf gall extract

Antioxidant and free radical scavenging potential of S. cumini leaf gall extracts (methanol and aqueous) was evaluated by using DPPH, FRAP, nitric oxide and hydroxyl radical assays.

Free radical scavenging activity [DPPH]

Quantitative measurement of radical scavenging properties of S. cumini leaf gall extracts was carried out according to the method of Blois.25 Briefly, a 0.1 mM solution of 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH.) in methanol was prepared and 1 ml of this solution was added to 3 ml of both methanol and aqueous extracts at different concentrations (1-15 µg/ml). Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control. After incubation for 30 min in the dark, the discoloration was measured at 517 nm. Measurements were taken in triplicate. The capacity to scavenge the DPPH* radical was calculated and expressed as inhibition percentage using the following equation:

I%= (Absorbance of control – Absorbance of test/Absorbance of control) ×100

The IC50 values (concentration of sample required to scavenge 50% of free radicals) were calculated by the regression equation prepared from different concentrations of both methanol and aqueous extracts.

Ferric reducing/antioxidant power activity (FRAP)

Ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP) was determined following the method reported by Zhao et al.26 S. cumini leaf gall extracts (methanol and aqueous) at various concentrations (1-15 µg/ml) were mixed with 2.5 ml of 200 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 2.5 ml of 1% potassium ferricyanide. Mixtures were incubated at 50 ºC for 20 min, then 2.5 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid was added and the tubes were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Five milliliters of the upper layer of the solution was mixed with 5.0 ml distilled water and 1 ml of 0.1% ferric chloride. The absorbance of the reaction mixtures was measured at 700 nm. Ascorbic acid was taken as standard and the final results were expressed as mg ascorbic acid equivalent/g of dry weight.

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

Quantitative measurement of hydroxyl radical scavenging properties of S. cumini leaf gall extracts was carried out by measuring the competition between deoxyribose and the extract for hydroxyl radicals generated from the Fe3+/Ascorbate/EDTA/H2O2 system.27 S. cumini leaf gall extracts (methanol and aqueous) at various concentrations (1-15µg/ml) were mixed with the reaction mixture containing 0.1 ml of 3.0 mM deoxyribose, 0.5 ml of FeCl3(0.1 mM), 0.5 ml of EDTA (0.l mM), 0.5ml of ascorbic acid (0.1mM), 0.5ml of H2O2 (1m M) and 0.8ml of phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) and made up to final volume of 3.0 ml. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 ºC for 1h. A 1 ml portion of the incubated mixture was mixed with 1 ml of 10% trichloroacetic acid and 1.0 ml of 0.5% thiobarbituric acid to develop pink chromogen that is measured at 532 nm. The hydroxyl radical scavenging capacity was calculated and expressed as inhibition percentage of deoxyribose degradation using following equation:

I%= (Absorbance of control – Absorbance of test/Absorbance of control) ×100

The IC50 values (concentration of sample required to scavenge 50% of free radicals) were calculated by the regression equation prepared from different concentrations of both methanol and aqueous extracts.

Nitric oxide radical assay

Quantitative measurement of nitric oxide radical scavenging properties of S. cumini leaf gall extracts was carried out whereas at physiological pH, the nitric oxide generated from aqueous sodium nitroprusside solution, which interacts with oxygen to produce nitrite ions solution, is quantified by the Griess Illosvoy reaction.28 S. cumini leaf gall extracts (methanol and aqueous) at various concentrations (1-15µg/ml) were mixed with 2 ml of sodium Nitroprusside (10 mM) in standard phosphate buffer saline (50 mM, pH 7.4) and incubated at room temperature for 3 h. After the incubation period, samples were diluted with 0.5 ml of Griess reagents. The absorbance of the color developed during diazotization of nitrite with sulphanilamide and its subsequent coupling with N-(1-Naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride was measured at 550 nm on spectrophotometer. Ascorbic acid was used as a standard. Nitric oxide radical scavenging capacity was calculated and expressed as inhibition percentage using the following equation:

I %= (Absorbance of control –Absorbance of test/Absorbance of control) ×100

The IC50 values (concentration of sample required to scavenge 50% of free radicals) were calculated by the regression equation prepared from different concentrations of both methanol and aqueous extracts.

Statistical analysis

The experiments were carried out in triplicate and results were given as the mean±standard deviation. The data in all the experiments were analyzed (Microsoft Excel 2007) for statistical significance using Students t-test and differences were considered significant at p< 0.05.

Results and discussion

All over the world, as antioxidant therapy is gaining importance in the treatment of several metabolic diseases (diabetes mellitus, arthritis, cancer, aging, liver disorder, etc.), several scientific developmental programs have started with an aim at investigating medicinal properties of plants for their potential antioxidant properties.3,4 In these lines, the antioxidant potential of aqueous and methanol extracts of leaf galls of S. cumini is evaluated and its phytochemical constituents are determined. In the phytochemical screening, the qualitative presence of phenolics, flavonoids, phytosterols, terpenoids, and reducing sugars was identified in both the aqueous and methanol extracts of leaf galls of S. cumini. However, the alkaloids were found only in methanol and the saponins in aqueous extracts (Table 1). The antioxidant activities of plant/herb extracts are often explained by their total phenolic and flavonoid contents. The total amount of phenolic and flavonoid content of aqueous and methanol extracts of leaf galls of S. cumini is presented in Table 2 . The result indicates that in comparison with the aqueous extract, the methanol extract had the highest total phenolic and flavonoid contents at 474±2.2 mg of GAE/g d.w and 668±1.4 mg of QUE/g d.w, respectively. These results indicate that the methanol possessed significant activity in releasing most of the secondary metabolites from leave galls of S. cumini. This may be due to the fact that phenolic and flavonoid compounds are often extracted in higher amounts by using polar solvents such as aqueous methanol/ethanol.29 It is known that differences in the polarity of the extracting solvents could result in a wide variation in the polyphenolic and flavonoid contents of the extract.4,30 Phenolic antioxidants are products of secondary metabolism in plants, and their antioxidant activity is mainly due to their redox properties, which can play an important role in chelating transitional metals and scavenging free radicals.31 Similarly, the mechanisms of action of flavonoids are also through scavenging or chelating processes.32 Further, it is demonstrated that compounds such as flavonoids, which contain hydroxyl functional groups, are responsible for the antioxidant effects of plants.33 Therefore, higher amount of total phenolic and flavonoid contents of leaf galls extracts of S. cumini suggested that it possesses high antioxidant activity.

Table 1. Phytochemical evaluation of S. cumini leaf gall extracts .

| Phytochemical analysis |

Methanolic extract

of S. cumini |

Aqueous extract of S. cumini |

| Phenolics and Tannins | + | + |

| Flavonoids | + | + |

| Phytosterols and Triterpenoids | + | + |

| Alkaloids | + | - |

| Saponins | - | + |

| Carbohydrates | + | + |

| Glycosides | - | - |

|

Fixed oils and fats |

- | - |

(+) indicates presence; (-) indicate Absence

Table 2. Total phenolic and total flavonoid content of S. cumini leaf gall extracts .

| Gall Extracts |

Total phenolic

(mg of GAE/g d.w) |

Total flavonoids

(mg of QUE/g d.w) |

| Aqueous extract | 447±1.5 | 431±1.2 |

| Methanolic extract | 474±2.2 | 668±1.4 |

Each value is expressed as mean ± SD.

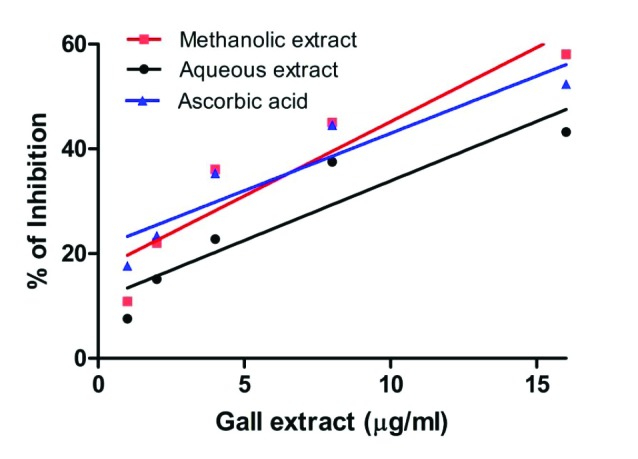

DPPH is a stable free radical, which has been widely accepted as a tool for estimating free radical-scavenging activities of antioxidants.34 The inhibition percentage of DPPH in the presence of aqueous and methanol extracts of S. cumini is as shown in Fig. 1. The aqueous extract exhibited an inhibition of 43.23%, whereas methanol extract showed 58.07% inhibition at the concentration of 15 µg/ml. Therefore, the methanol extract exhibited higher DPPH scavenging activity, when compared to the aqueous leaf gall extract of s. cumini. The IC50 values of aqueous and methanol extract were found to be 24.77±08 µg/ml and 9.97±02 µg/ml, respectively (Table 3). The IC50 value of standard ascorbic acid was found to be 12.93±03 µg/ml, indicating that the methanol extract (9.97 µg/ml) processes potent DPPH scavenging activities. The reduction in the color of DPPH radical due to the scavenging ability of the methanol extracts and antioxidant standard (ascorbic acid) was found to be significant (p≤0.05).

Fig. 1 .

Free radical scavenging activity of aqueous and methanol extracts of leaf galls of S. cumini. Ascorbic acid is included as positive control. Activity was measured by the scavenging of DPPH radicals and expressed as % inhibition. Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Table 3. IC50 Values of S. cumini gall extracts extracts with standard ascorbic Acid .

|

S. cumini

Gall

Extract |

IC 50 Values (µg/ml) | ||

| DPPH Assay | Nitric oxide scavenging Assay | Hydroxyl radical scavenging assay | |

| Aqueous extract | 24.77±08 | 121.1±04 | 19.68±02 |

| Methanolic extract | 9.97±02 | 40.20±02 | 9.97±04 |

| Ascorbic Acid | 12.93±03 | 40.17±06 | 24.28±06 |

Each value is expressed as mean ± SD.

These results indicate that the methanol extracts have a noticeable effect on scavenging free radicals and can be related to the high phenolic constituents present (Table 2). Phenolic antioxidants are products of secondary metabolism in plants, and the antioxidant activity is mainly due to their redox properties, which can play an important role in chelating transitional metals, inhibiting lipoxygenase and scavenging free radicals.35 Phenolic compounds are also effective hydrogen donors, which makes them good antioxidants.36

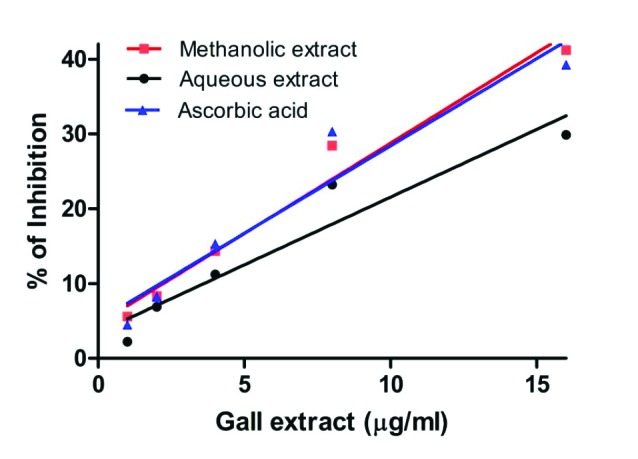

Nitric oxide is a reactive molecule and causes severe cytotoxicity in living cells, thus removing nitric oxide is of prime importance in antioxidant therapy. The inhibition percentage of nitric oxide scavenging potential of aqueous and methanol extracts of S. cumini are as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 .

Nitric oxide scavenging activity of aqueous and methanol extracts of leaf galls of S. cumini. Ascorbic acid is included as positive control. Activity was measured and expressed as % inhibition. Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

The methanol extract of S. cumini is found to be much more effective in scavenging nitric oxide radicals than the aqueous extract. The scavenging activity in terms of IC50 values of aqueous and methanol extracts of S. cumini gall are calculated as 121.1±04 µg/ml and 40.20±02 µg/ml, respectively (Table 3). It was observed that the IC50 value of methanol extract was equivalent to that of standard ascorbic acid (IC50 = 40.17±06 µg/ml) (Table 3). Therefore, in the present study the methanol extract exhibited higher nitric oxide scavenging activity, when compared to the aqueous leaf gall extract of S. cumini, which can be related to the high phenolic constituents present (Table 2).

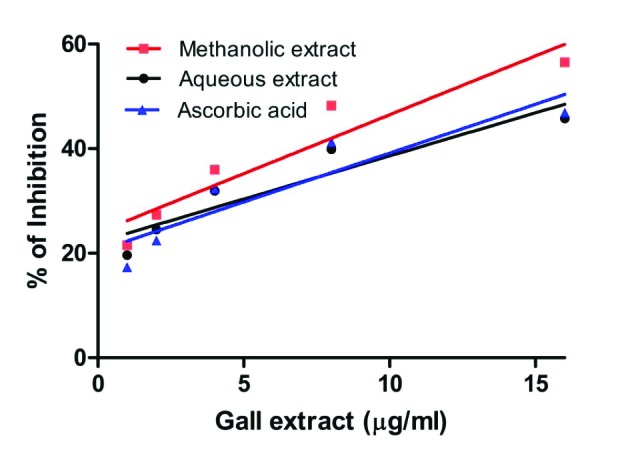

The highly reactive hydroxyl radicals can cause oxidative damage to DNA, lipids and proteins. The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of leaf galls of S. cumini is as shown in Fig. 3. The inhibition percentage of aqueous and methanol extracts of S. cumini gall was found to be 45.77% and 56.55%, respectively at a concentration of 15µg/ml. The methanol extract exhibited higher DPPH scavenging activity, when compared to the standard and the aqueous leaf gall extracts of S. cumini. The IC50 values of aqueous and methanol extracts were found to be 19.68±02 µg/ml and 9.97±04 µg/ml, respectively (Table 3 ). The IC50 value of standard ascorbic acid was found to be 24.28 µg/ml, indicating that the methanol extract (9.97±04 µg/ml) processes potent hydroxyl radical scavenging activities which can be related to the high phenolic constituents present (Table 2 ).

Fig. 3 .

Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of aqueous and methanol extracts of leaf galls of S. cumini.Ascorbic acid is included as positive control. Activity was measured and expressed as % inhibition. Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

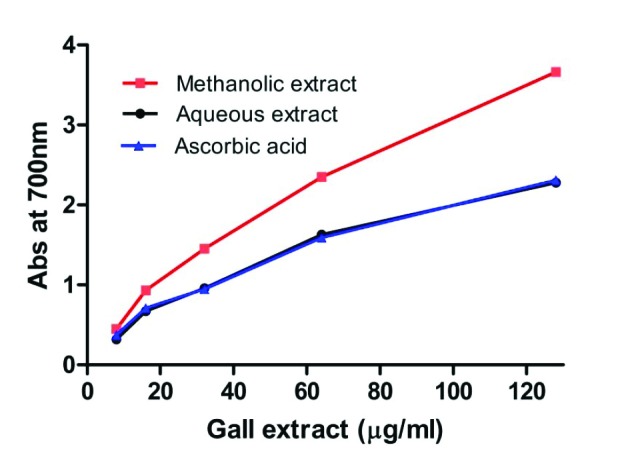

The reducing capacity of compounds or extracts may serve as a significant indicator of its potential antioxidant activity. The presence of a reductant such as antioxidant substances in plant extracts causes the reduction of Fe+3 ferricyanide complex to the ferrous form, Fe+2. The reduction capabilities of aqueous and methanol extracts of leaf galls of S. cumini in comparison with standard ascorbic acid is as indicated in Fig. 4. In comparison with the aqueous extract, the methanol extract had better reducing power at a concentration of 125 µg/ml and possessed equal potential with the standard ascorbic acid used (Fig. 4). The ferric reducing power of leaf galls of S. cumini may be attributed to the high phenolic and flavonoid contents of the extracts (Table 2). The ability to reduce Fe+3 may be attributed to the hydrogen donation from phenolic compound, which is related to the presence of a reducing agent.37,38 In addition, the number and position of hydroxyl group of phenolic compounds also govern their antioxidant activity.36

Fig. 4 .

Ferric reducing power of aqueous and methanol extracts of leaf galls of S. cumini .Ascorbic acid is included as positive control. Activity is expressed as absorbance at 700 nm. Each value is expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

As exemplified earlier, the antioxidant activities of plant/herb extracts are often explained by their total phenolic and flavonoid contents. In this study, it was observed that there was a strong correlation between antioxidant activities with total phenolic and flavonoid contents in the leaf gall extracts of S. cumini. Syzygium species are reported to be very rich in tannins, flavonoids, essential oils, anthocyanins and other phenolic constituents.39,40 The results given in this investigation showed that the phenolic and flavonoid contents were higher in polar extracts (methanol) and subsequently the extract possessed higher antioxidant potential. Therefore, it seems clear that the presence of polar phenolics is fundamental for free radical-scavenging activity.41 The activity of antioxidant has been assigned to various mechanisms such as prevention of chain initiation, binding of transition-metal ion catalysts, decomposition of peroxides, prevention of continued hydrogen abstraction, reductive capacity and radical scavenging.42 It is possible that the compounds present in the S. cumini gall extract bring about the antioxidant effect through various mechanisms. The observations confirm the folklore use of S. cumini leaves gall extracts as a natural antioxidant and justify the ethnobotanical approach in the search for novel bioactive compounds.

Conclusion

The results of this study confirm the folklore use of S. cumini leaves gall extracts as natural antioxidant and justify the ethnobotanical approach in the search for novel bioactive compounds. Further, it was observed that there was a strong correlation between higher antioxidant activities and high total phenolic and flavonoid contents in the methanol leaf gall extracts of S. cumini. Therefore, these findings support the view that the extracts obtained using a high polarity solvent (methanol) are considerably more effective radical scavengers. The results support the use of gall extracts as promising sources of potential antioxidants that may be effective as preventive agents in the pathogenesis of some metabolic diseases. Therefore, this study encourages the use of S. cumini leaves gall extracts for medicinal health, functional food and nutraceutical applications, due to their antioxidant properties. Future work would be interesting to know the chemical composition and better understand the mechanism of action of the antioxidants present in the extract for development as drug for therapeutic application.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Dr. R. Chenraj Jain, President, Jain University Trust., Dr. N Sundararajan, Vice Chancellor, Jain University and Prof. K.S. Shantamani, Chief Mentor, Jain University, Bangalore for their kind support and encouragement and for providing facilities for carrying out this work. DBL thanks Jain University for the constant encouragement provided to proceed research activities.

Ethical issues

There is none to be applied.

Conflict of interests

There is none to be declared.

References

- 1.Halliwell B. Antioxidants and human disease: a general introduction. Nut Rev. 1997;55:44–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb06100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gossell-Williams M, Simon OR, West ME. The past and present use of plants for medicines. West Indian Med J. 2006;55:217–218. doi: 10.1590/s0043-31442006000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auddy B, Ferreira F, Blasina L, Lafon F, Arredondo F, Dajas R. et al. Screening of antioxidant activity of three Indian medicinal plants, traditionally used for the management of neurodegenerative diseases. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84:131–138. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrestha S, Subaramaihha SR, Subbaiah SG, Eshwarappa RS, Lakkappa DB. Evaluating the antimicrobial activity of methanolic extract of rhus succedanea leaf gall. BioImpacts. 2013;3:195–198. doi: 10.5681/bi.2013.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shrestha S, Kaushik VS, Eshwarappa RS, Subaramaihha SR, Ramanna LM, Lakkappa DB. Pharmacognostic studies of insect gall of Quercus infectoria Olivier (Fagaceae) Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:35–39. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(14)60205-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Publication and Information Directorate. The Wealth of India, A Dictionary of Indian Raw materials and Industrial products. New Delhi: CSIR; 1976; p.120-121.

- 7.Shantha TR, Shetty JKP, Yoganarasinhan SN, Sudha R. Farmocognostical studies on South Indian market sample of Karkatasringi-Terminalia chebulla (Gaertnleaf gall) Anc Sci Life. 1991;11:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kottakkal AVS. Indian Medicinal Plants Vol. 4. Kottakkal: Orient Longman Ltd; 1995.

- 9. Kirthikar KR, Basu BD. Indian Medicinal Plants Vol. 2. Allahabad: Lalit Mohan Basu; 1935; p.1479.

- 10.Sukh D. Ethanotherapeutics and modern drug developmentThe potential of Ayurveda. Curr Sci. 1997;73:909–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nadkarni KM. Indian Materia Medica. 3rd edition. Mumbai:Popular Prakashan Ltd; 1976 ; P. 1062-3.

- 12.Chandhuri AKN, Pal S, Games A, Bhattacharya S. Anti-inflammatory and related actions of Syzigium cumini seed extract. Phytotherapy Res. 1990;4:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Indira G, Mohan R. Jamun Fruits. Hyderabad: National Institute of nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research.1992; p.34–37.

- 14. Rastogi RM, Mehrotra BN. Compendium Indian Medicinal Plants. Vol.4. New Delhi: Loknow and Publication and Information Directorate, CDRI; 1995; p.96.

- 15. Warrier PK, Nambiar VPK, Ramankutty C. Indian Medicinal Plants. 5th ed. Hyderabad:Orient Longman Ltd; 1996; p.225–228.

- 16.Sharma AK, Bharti S, Kumar R, Krishnamurthy B, Bhatia J, Kumari S. et al. Syzygium cumini ameliorates insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction via modulation of PPAR, dyslipidemia, oxidative stress, and TNF-α in type 2 diabetic rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2012;119:205–213. doi: 10.1254/jphs.11184fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srivastava S, Chandra D. Pharmacological potentials of Syzygium cumini: A review. J Sci Food Agric. 2013;93:2084–93. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gunakari Ayurvediy Aushadhe. Ayurveda Rasashala, Pune; 1968; p. 765-768.

- 19. Harborne JJ. Phytochemical Methods: A Guide to Modern Techniques of Plant Analysis. 2nd edition. New York: Chapman and Hall;1984; p. 85.

- 20. Trease GE, Evans WC. Pharmacognosy. 13th edition. Delhi: ELBS Publication;1989; p.171.

- 21. Kokate CK, Purohit AP, Gokhale SB. Pharmacognosy. 23rd edition. Pune:Nirali Prakashan;1998; p.106-114.

- 22. Khandelwal KR. Practical Pharmacognosy: Techniques and Experiments. 13th edition. Pune: Nirali Prakashan;2005; p.149-156.

- 23.Kaur C, Kapoor HC. Anti-oxidant activity and total phenolic content of some Asian vegetables. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2002;37:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang C, Yang M, Wen H, Chern J. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J Food Drug Anal. 2002;10:178–182. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blois MS. Antioxidants determination by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181:1199–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao H, Fan W, Dong J, Lu J, Chen J, Shan L. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant activities and total phenolic contents of typical malting barley varieties. Food Chem. 2008;107:296–304. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halliwell B, Grootveld M, Gutteridge JMC. Methods for the Measurement of Hydroxyl Radicals in Biochemical Systems: Deoxyribose Degradation and Aromatic Hydroxylation. Methods Biochem Anal. 1988;33:59–90. doi: 10.1002/9780470110546.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar S, Kumar D, Jusha M, Saroha K, Singh N, Vashishta B. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging potential of Citrullus colocynthis (L) Schradmethanolic fruit extract. Acta Pharm. 2008;58:215–220. doi: 10.2478/v10007-008-0008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sultana B, Anwar F, Przybylski R. Antioxidant activity of phenolic components present in barks of barks of Azadirachta indica, Terminalia arjuna, Acacia nilotica, and Eugenia jambolana Lam trees. Food Chem. 2007;104:1106–14. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi Y, Jeong HS, Lee J. Antioxidant activity of methanolic extracts from some grains consumed in Korea. Food Chem. 2007;103:130–138. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohamed AA, Khalil AA, El-Beltagi HES. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of kaff maryam (Anastatica hierochuntica) and doum palm (Hyphaene thebaica) Grasas Y Aceites. 2010;61:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler M, Ubeaud G, Jung L. Anti- and pro-oxidant activity of rutin and quercetin derivatives. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2003;55:131–142. doi: 10.1211/002235702559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das NP, Pereira TA. Effects of flavanoids on thermal autooxidation of palm oil: structure activity relationship. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1990;67:255–258. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naik GH, Priyadarsini KI, Satav JG, Banavalikar MM, Sohani DP, Biyani MK. et al. Comparative antioxidant activity of individual herbal components used in ayurvedic medicine. Phytochem. 2003;63:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Decker EA. Phenolics: prooxidants or antioxidants? Nutr Rev. 1997;55:396–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Bolwell PG, Bramley PM, Pridham JB. The relative antioxidant activities of plant-derived polyphenolic flavonoids. Free Radical Res. 1995;23:375–383. doi: 10.3109/10715769509145649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimada K, Fujikawa K, Yahara K, Nakamura T. Antioxidative properties of xanthan on the autoxidation of soyabean oil in cyclodextrin emulsion. J Agric Food Chem. 1992;40:945–948. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duh PD. Antioxidant activity of Budrock (Arctium laooa Linn) its scavenging effect on free radical and active oxygen. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1998;75:455–461. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma SB, Nasir A, Prabhu KM, Murthy PS, Dev G. Hypoglycaemic and hypolipidemic effect of ethanolic extract of seeds of Eugenia jambolana in alloxan-induced diabetic rabbits. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;85:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reynertson KA, Yang H, Jiang B, Basile MJ, Kennelly MEJ. Quantitative analysis of antiradical phenolic constituents from fourteen edible Myrtaceae fruits. Food Chem. 2008;109:883–890. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Reza SM, Rahman A, Kang SC. Chemical composition and inhibitory effect of essential oil and organic extracts of Cestrum nocturnum Lon food-borne pathogens. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2009;44:1176–1182. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yildirim A, Mavi A, Oktay M, Kara AA, Algur OF, Bilaloglu V. Comparison of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Tilia (Tilia argentea Desf ex DC), Sage (Salvia triloba L), and Black Tea (Camellia sinensis) extracts. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:5030–5034. doi: 10.1021/jf000590k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]