Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) has been proposed to be an immune‐mediated disease in the central nervous system (CNS) that can be triggered by virus infections. In Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection, during the first week (acute stage), mice develop polioencephalomyelitis. After 3 weeks (chronic stage), mice develop immune‐mediated demyelination with virus persistence, which has been used as a viral model for MS. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) can suppress inflammation, and have been suggested to be protective in immune‐mediated diseases, including MS. However, in virus‐induced inflammatory demyelination, although Tregs can suppress inflammation, preventing immune‐mediated pathology, Tregs may also suppress antiviral immune responses, leading to more active viral replication and/or persistence. To determine the role and potential translational usage of Tregs in MS, we treated TMEV‐infected mice with ex vivo generated induced Tregs (iTregs) on day 0 (early) or during the chronic stage (therapeutic). Early treatment worsened clinical signs during acute disease. The exacerbation of acute disease was associated with increased virus titers and decreased immune cell recruitment in the CNS. Therapeutic iTreg treatment reduced inflammatory demyelination during chronic disease. Immunologically, iTreg treatment increased interleukin‐10 production from B cells, CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells, which may contribute to the decreased CNS inflammation.

Keywords: autoimmunity, CNS demyelinating disease, immunology, inflammation, Picornaviridae infections, regulatory T lymphocyte

Introduction

The precise etiology of multiple sclerosis (MS) and the trigger for the initial demyelinating attack remain elusive; it has been suggested that the immunopathogenesis of MS is triggered by an autoimmune response against central nervous system (CNS) antigens and/or a microbial infection, particularly virus infections 29. Autoreactive antibody (Ab) and T‐cell responses can be found in MS patients, which supports an autoimmune etiology 45. Experimentally, experimental autoimmune (or allergic) encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model that resembles MS histologically, can be induced by sensitization with CNS antigens. On the other hand, an infectious etiology for MS has been considered since its initial descriptions 32. Direct virus infection of oligodendrocytes can result in demyelination 9. In addition, a viral infection can result in development of autoimmunity either through molecular mimicry between a virus and myelin or through determinant (or epitope) spreading following the destruction of myelin and release of autoantigen 30, 65. Clinically, the viral etiology of MS has been supported by detection of virus itself or antiviral immune responses from MS patients 55. Experimentally, a demyelinating disease can be induced by infection with several viruses, including Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) 47.

TMEV initially infects neurons during the first 2 weeks postinfection (p.i.) (acute stage) and spreads via axonal transport, causing axonal degeneration. During the chronic stage, more than 3 weeks p.i., TMEV infects macrophages and glial cells, causing inflammatory demyelinating lesions similar to the neuropathology found in MS. TMEV‐induced demyelinating disease (TMEV‐IDD) in susceptible mouse strains, such as SJL/J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), has been used as a viral model for MS 28. Moreover, resistant mouse strains, such as C57BL/6 and BALB/c, develop only acute disease without viral persistence or demyelination. Although the precise pathomechanism in TMEV‐IDD is unclear, both direct viral infection and immune‐mediated pathology (immunopathology) can contribute to demyelination. Although TMEV can directly infect and lyse myelin‐forming oligodendrocytes, there is also evidence of the involvement of CD4+ T‐helper (Th1) and Th17 cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and antibodies in the pathogenesis of TMEV‐IDD 8, 15, 18, 35, 42, 43, 56.

Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are characterized by the expression of CD4, CD25 and the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) 2. These cells play a central role in protecting an individual from autoimmunity 46. Tregs can suppress proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 type immune responses, which have been suggested to play a pathogenic role in several immune‐mediated diseases and animal models, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), MS and EAE 24, 44. Adoptive transfer of Tregs isolated from naïve mice has been shown to ameliorate EAE induced with either active myelin antigen sensitization or passive transfer of myelin‐specific T cells 14, 24. These findings in EAE imply that Tregs could also be beneficial in MS.

On the other hand, the role of Tregs in viral infections, where tissue damage can be caused by uncontrolled immune responses (immunopathology) or viral replication and persistence, remains relatively unknown 28. Although Tregs may play a protective role by preventing immunopathology, Tregs can also play a detrimental role by suppressing antiviral immune responses, which leads to more active viral replication and/or viral persistence. For example, in West Nile virus infection, because the tissue damage is caused by immunopathology, suppression of antiviral immune responses reduced pathology 26. In contrast, in Friend virus infection, because the tissue damage is caused by viral replication, suppression of antiviral immune responses by Tregs was detrimental 12. Thus, we hypothesized that Tregs can be a double‐edged sword in TMEV‐IDD, as both immunopathology and direct virus infection can contribute to the pathogenesis.

In TMEV infection, a rapid expansion of Tregs was found in susceptible SJL/J mice but not in resistant C57BL/6 mice after TMEV infection 40. In TMEV‐infected SJL/J mice, administration of anti‐CD25 Ab during the acute stage of disease to inactivate Tregs enhanced antiviral immune responses and reduced disease severity. These results suggest that a differential induction of Tregs between mouse strains may be responsible for susceptibility to TMEV‐IDD, where Tregs play a detrimental role in susceptible SJL/J mice. On the other hand, in the mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) model of virus‐IDD using the neurotropic strain of MHV, adoptive transfer of Tregs was found to decrease immune‐mediated demyelination and mortality 1, 54. These results suggest that clinical application of Treg modulation in viral pathology requires consideration of viral replication kinetics, antiviral immune responses and immunopathology.

We have developed a novel method to ex vivo generate approximately 2 × 107 induced Tregs (iTregs) from the spleen of one SJL/J mouse 21. These iTregs were CD4+, FOXP3+ and CD25+, and can suppress the proliferation of CD4+ CD25− T cells in vitro. These iTregs have been shown to suppress inflammation in a mouse model of IBD 20. We tested the role and potential translational application of Tregs in TMEV‐IDD by administering iTregs to TMEV‐infected mice. Therapeutic iTreg treatment during the chronic stage of disease suppressed inflammation in the CNS of mice. In contrast, early iTreg treatment resulted in exacerbation of acute disease. These results suggest that an efficient Treg‐based treatment requires careful consideration of several factors, including viral replication, antiviral immune responses, immunopathology and the timing of the treatment.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female 4‐week‐old SJL/J and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and Harlan Laboratories, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN, USA), respectively. Animals were maintained on 12/12‐h light/dark cycles in standard animal cages with filter tops under specific pathogen‐free conditions in our animal care facility at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (LSUHSC)–Shreveport and given standard laboratory rodent chow and water ad libitum. All experimental procedures involving the use of animals were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of LSUHSC and performed according to the criteria outlined by the National Institutes of Health.

Ex vivo iTreg induction

iTregs were induced as previously described 21. Briefly, a 24‐well plate was coated with anti‐mouse CD3 Ab (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) by an overnight incubation with 500 mL of a 10 g/mL solution at 4°C. Spleens were aseptically removed from mice and mashed through a 74‐µm stainless steel mesh (CX‐200, Small Parts, Inc., Miami Lakes, FL, USA) and pipetted up and down vigorously to reach a single cell suspension. CD4+ cells were isolated from the suspension using an EasySep® Negative Selection Mouse CD4+ T‐Cell Enrichment Kit (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). These cells were resuspended at 5 × 105 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, USA), 1% L‐glutamine (Mediatech), 1% antibiotics (Mediatech), 50 M 2‐mercaptoethanol (Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 100 U/mL recombinant human interleukin (IL)‐2 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), 20 ng/mL transforming growth factor (TGF)‐β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and 1 nM all trans retinoic acid (Sigma‐Aldrich). The anti‐CD3 Ab coated plate was washed three times with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS), and then the cell solution was added at 1 mL per well to the plate and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 4 days. Cells were assessed for purity by flow cytometry. In the absence of TFG‐β and retinoic acid, the cell populations were only 20%–40% FOXP3+.

Flow cytometry

Fc receptors of cells were blocked with anti‐CD16/32 Ab (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Cells were stained with antibodies against CD3 (BioLegend), CD4 (BioLegend), CD8 (BioLegend), CD11c (BioLegend) a dendritic cell marker, B220/CD45R a B‐cell marker (BioLegend) 17, F4/80 a macrophage marker (BioLegend), FOXP3 (eBioscience), interferon (IFN)‐γ (BioLegend), IL‐10 (BioLegend), IL‐17A (BioLegend), CD25/IL‐2 receptor (IL‐2R) α (BioLegend) and CD49d/α4 integrin (BioLegend). Cells were permeabilized and fixed using the BD Cytofix/CytopermTM Plus Fixation/Permeabilization Kit. The flow cytometry data were acquired on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed using CellQuest Pro (BD Biosciences). For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were incubated with 500 ng/mL phorbol 12‐myristate 13‐acetate (PMA) (Sigma‐Aldrich), 25 ng/mL ionomycin (Sigma‐Aldrich) with or without TMEV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1, and 1 μL/mL of brefeldin A (GolgiPlugTM, BD Biosciences) for 6 h before staining.

In vitro suppression assay

Suppression of CD4+ T‐cell proliferation was assessed as previously described 10. iTregs were cultured with 5 × 104 responder CD4+CD25− T cells at 1:1, 1:2, 1:5, 1:10 and 1:50 of iTreg/responder ratios, 105 irradiated antigen presenting cells (APCs), and 2.5 μg concanavalin A (ConA), in a flat bottom 96‐well plate at a final volume of 300 μL per well. APCs were prepared by irradiating splenocytes with 2000 rads in a model 143 laboratory irradiator (JL Shepherd and Associates, San Fernando, CA, USA). CD4+CD25− (responder) T cells were isolated by first isolating CD4+ T cells using an EasySep® Negative Selection Mouse CD4+ T‐Cell Enrichment Kit (Stemcell Technologies), then incubating the CD4+ T cells with biotinylated CD25 Ab (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and streptavidin magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA, USA), and then running the labeled cells through a magnetic column to remove the CD25+ fraction. The iTregs, responder cells and APCs were cultured together with ConA for 72 h, with the addition of 1 μCi per well of tritiated [3H]thymidine (Perkin‐Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA, USA) for the final 24 h. Cells were harvested on Reeves Angel 934AH filters (Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) using PHDTM Harvester (Brandel). The incorporated radioactivity was measured by Wallac 1409 Liquid Scintillation Counter (Perkin‐Elmer). All cultures were performed in triplicate, and the data were expressed as stimulation indexes [experimental counts per minute (cpm)/control cpm].

Animal experiments

Induction of iTregs from a naïve mouse was verified with flow cytometry; the iTregs were washed in PBS and resuspended at 4 × 105 cells/mL in PBS. Mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected with 500 μL of iTregs (2 × 105 cells) either on day 0 (iTreg‐early) or 3–4 weeks p.i. (iTreg‐late). This was the optimal dose that was previously determined in an IBD model 20. We found that this cell number was also efficacious to all mice, as all iTreg‐treated mice showed similar changes clinically, pathologically and immunologically. Mice were infected intracerebrally (i.c.) with 2 × 105 plaque forming units (PFU) of the Daniels (DA) strain of TMEV in a volume of 20 μL in PBS 60. Mice were weighed and observed daily for up to 3 months. Clinical signs of neurological disease were evaluated by measuring impairment in the righting reflex, which is a standard scoring system for motor impairment during TMEV infection 38, 53. Additionally, using the righting reflex test daily does not condition the mice and improve their score 5. When the proximal end of the mouse's tail is grasped and twisted to the right and then to the left, a healthy mouse resists being turned over (score of 0) 60. If the mouse is flipped onto its back but immediately rights itself on one side or both sides, it is given a score of 1 or 1.5, respectively. If it rights itself in 1–5 s, the score is 2. If righting takes more than 5 s, the score is 3. iTreg‐early mice were killed on either day 7 or 8 p.i., and iTreg‐late mice were killed on days 48, 60 or 81 p.i.

Neuropathology

Mice were perfused with PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma‐Aldrich). The brains, coronally divided into five slabs, and the spinal cord, transversely divided into 12 segments, were embedded in paraffin. Four micrometer thick sections were stained with Luxol fast blue (Sigma‐Aldrich) for myelin visualization. Histological scoring was performed as described previously 61. Brain sections were scored for meningitis (0, no meningitis; 1, mild cellular infiltrates; 2, moderate cellular infiltrates; 3, severe cellular infiltrates), perivascular cuffing (0, no cuffing; 1, 1–10 lesions; 2, 11–20 lesions; 3, 21–30 lesions; 4, 31–40 lesions; 5, over 40 lesions) and demyelination (0, no demyelination; 1, mild demyelination; 2, moderate demyelination; 3, severe demyelination). Each score from the brain was combined for a maximum score of 11 per mouse. For scoring of spinal cord sections, each spinal cord segment was divided into four quadrants: the ventral funiculus, the dorsal funiculus and each lateral funiculus. Any quadrant containing meningitis, perivascular cuffing or demyelination was given a score of 1 in that pathological class. The total number of positive quadrants for each pathological class was determined and then divided by the total number of quadrants present on the slide and multiplied by 100 to give the percentage involvement for each pathological class. An overall pathological score was also determined by giving a positive score if any pathology was present in the quadrant. This was also presented as the percentage involvement. CD3+ T cells were visualized by antigen retrieval using citrate‐based Vector® Antigen Unmasking Solutions (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), followed by immunohistochemistry with anti‐CD3 Ab (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), using the avidin‐biotin‐peroxidase complex (ABC) technique (Vector Laboratories) 58. The numbers of CD3+ cells were counted under a light microscope using 10–12 transverse spinal cord segments per mouse as previously described 58.

Virus titration

Brains and spinal cords were aseptically isolated from infected mice, weighed and homogenized in 1 mL of Minimal Eagles Media (Gibco/BRL, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA) 33. Baby hamster kidney (BHK)‐21 cells were plated in 6‐well plates. When the monolayers had reached 80%–90% confluence, the media was aspirated and 0.3 mL of diluent, PBS containing 1% FBS, was added to each well. Serial dilutions (0.2 mL) of brain or spinal cord homogenate were added to each well, and the virus was allowed to adsorb for 1 h at 37°C. The diluent was aspirated, and 3 mL of a 50:50 mixture of sterile 1% agarose and 2X 199 media (Mediatech) containing 2% FBS and 3% antibiotic/antimycotic (Mediatech) was added to each well. The agarose overlay was solidified at room temperature for 20 minutes and the plates were returned to the 37°C incubator for 3 days. The plates were fixed with a 2.5% formalin solution in PBS overnight and stained the following day with a 0.1% solution of crystal violet (EMD Chemicals, Inc., Gibbstown, NJ, USA) in PBS.

Real‐time reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR)

Mice were killed and perfused with sterile PBS, and then the tissue was removed and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. The tissue was homogenized in TRI Reagent® (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA), and the total RNA was isolated from the homogenate using a RNAeasy® mini kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) 19. The reverse transcription reaction was performed with 1 μg of total RNA, using an ImProm‐II Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Sequential reaction conditions were annealing at 25 degree for 5 minutes and extension at 42 degree for 1 h. Real‐time RT‐PCR was performed in iCycler iQTM 96‐well PCR plates (Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) containing 12.5 μL RT2 Fast SYBR® Green qPCR Master Mix (SA Biosciences, Valencia, CA, USA), 10.5 μL double distilled (dd) H2O, 1.0 μL template cDNA (50 ng) and 1.0 μL gene‐specific 10 μM PCR primer pair stock in a MyiQ2 Two‐Color Real‐time PCR Detection System (Bio‐Rad). Sequential reaction conditions for RT‐PCR were activation of HotStart Taq DNA polymerase at 95 degree for 5 minutes, and then 40 cycles of 95 degree for 10 s and 60 degree for 30 s. The primers were purchased from RealTimePrimers.com (Elkins Park, PA, USA). The primer pair sequences for VP2, a virus capsid protein, were forward (5′‐TGGTCGACTCTGTGGTTACG‐3′) and reverse (5′‐GCCGGTCTTGCAAAGATAGT‐3′). Phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) 1 was used as an internal reference to normalize the results 49. The PGK1 primers were forward (5′‐GCAGATTGTTTGGAATGGTC‐3′) and reverse (5′‐TGCTCACATGGCTGACTTTA‐3′).

Anti‐TMEV Ab enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Serum anti‐TMEV antibodies were titrated by ELISA 25. Sera from mice were collected either at the acute or chronic stage. Plates were coated with 0.5 μg of TMEV antigen, and then blocked with 10% FBS in PBS. Serial dilutions of serum were plated. Horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated polyclonal goat anti‐mouse IgG (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was used to detect binding anti‐TMEV Abs. The reaction was developed by adding o‐phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma‐Aldrich), and stopped with 1N HCl. Absorbance was read at 492 nm on a Multiskan MCC/340 (Thermo Scientific, Rochester, NY, USA).

Lymphoproliferative assay

Spleens were removed from TMEV‐infected mice during the acute or chronic stage of disease; mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated using Histopaque® 1083 (Sigma‐Aldrich) 60. A volume of 100 μL of 2 × 105 MNCs in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% glutamine, 1% antibiotics, 50 μM 2‐mercaptoethanol and 10% FBS was added to each well of 96‐well plates. This was incubated with 100 μL of solution containing 2 × 105 TMEV‐infected APCs (TMEV‐APCs) or 2 × 105 sham‐infected APCs (nAPCs) 61. TMEV‐APCs were made from whole spleen cells infected in vitro with DA virus at a MOI of 5, 1, or 0.1 and irradiated with 2000 rads, whereas nAPCs were prepared from sham‐infected spleen cells. The cells were cultured for 4 days, after which time each well was pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine. Then, 18–24 h later, the cells were harvested and 3H incorporation was determined. A stimulation index was calculated using the following formula: (cpm of MNCs incubated with TMEV‐APCs)/(cpm of MNCs incubated with nAPCs). We have not included anti‐myelin immune responses in the lymphoproliferation assay, as epitope spreading to myelin epitopes has been shown to be detected 100 days or more p.i. in TMEV infection 63.

Cytokine ELISA

A volume of 2 mL of 4 × 106 spleen MNCs in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1% glutamine, 1% antibiotics, 50 μM 2‐mercaptoethanol and 10% FBS was added to each well of 6‐well plates. This was incubated with 2 mL of media or a solution containing 10 μg/mL ConA or 4 × 106 PFUs of TMEV (MOI of 1) for 2 days. After 2 days, the supernatants were collected and analyzed by ELISA 58. IFN‐γ, IL‐4 and IL‐10 concentrations were detected with BD OptEIA kits (BD Biosciences), and IL‐17 was detected with a Mouse IL‐17A ELISA MAXTM kit (BioLegend).

Results

Induction of iTregs in SJL/J mice

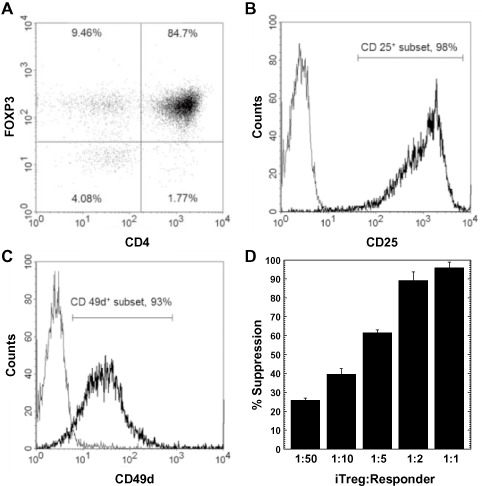

We first determined whether iTregs generated from SJL/J mice were similar in numbers and purity to what has been previously established in C57BL/6 mice 21. After the induction process, 84%–90% of the cells were FOXP3+CD4+ (Figure 1B). This population was 98% CD25+ and 93% CD49d+ {[α4 integrin of very late antigen (VLA)‐4]}, which are markers for Tregs and adhesion molecules related to homing to the CNS, respectively (Figure 1 A,C). We next examined whether iTregs have suppressive functions. iTregs were incubated with CD4+CD25− responder cells and irradiated APCs in the presence of ConA. At a 1 to 1 ratio of iTregs to responder cells, the amount of suppression was nearly 100%, and at a 1 to 50 ratio, the amount of suppression was approximately 25% (Figure 1D). The amount of suppression by iTregs from SJL/J mice depended on the ratio of iTregs vs. responder cells and was similar to the amount from iTregs from C57BL/6 mice that was described previously 21. Thus, we were able to induce iTregs from SJL/J mice, which were comparable with iTregs from C57BL/6 mice, phenotypically and functionally.

Figure 1.

Induced regulatory T cells (iTregs) generated from SJL/J mice. A. Representative dot plot of CD4 and forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) expression of iTregs by flow cytometry. B,C. Expression of CD25 and CD49d (very late antigen‐4), respectively, after gating on CD4+ FOXP3+ cells. iTregs were CD25+ and CD49d +. (Bold line, specific antibody; light line, isotype control.) D. iTregs efficiently suppressed proliferation of 5 × 104 responder CD4+ CD25− T cells at the indicated iTreg : Responder ratios, which were cultured with 105 irradiated antigen presenting cells and 2.5 μg concanavalin A for 3 days. Percentage suppression was determined by subtracting the proliferation (measured by a [3 H]thymidine incorporation assay) of responder cells stimulated in the presence of iTregs from the proliferation of responder cells stimulated in the absence of iTregs, divided by the proliferation of responder cells stimulated in the absence of iTregs. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

Therapeutic iTreg treatment suppresses TMEV‐IDD

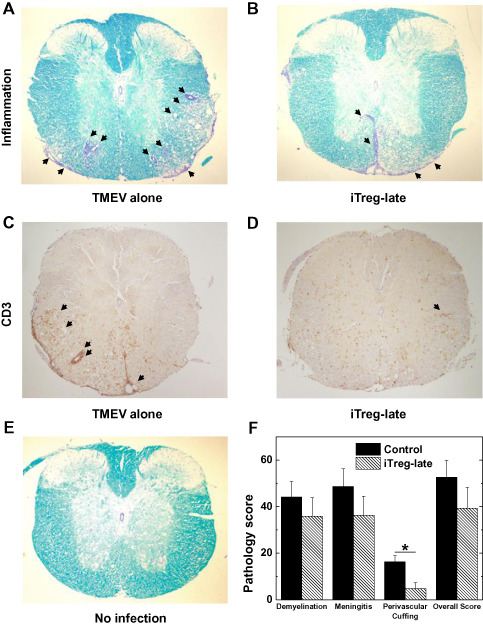

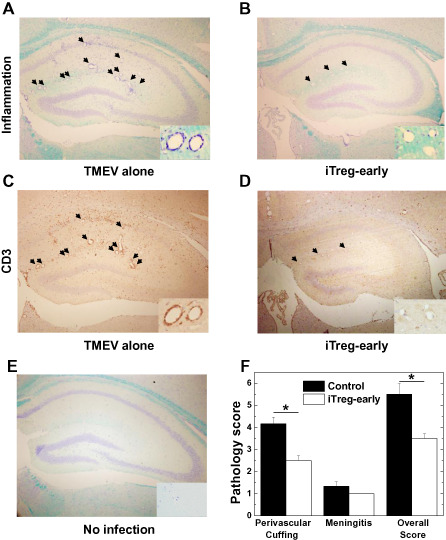

To test whether iTregs could be used to suppress ongoing TMEV‐IDD, we injected iTregs into TMEV‐infected mice after the onset of chronic demyelinating disease (iTreg‐late) and compared the development of demyelinating disease with TMEV‐infected mice without iTreg treatment (control). The control mice developed severe inflammatory demyelinating lesions in the spinal cord, particularly the lateral and ventral funiculus with meningitis and perivascular cuffing (Figure 2A). Although the iTreg‐late mice had a similar distribution of lesions in the spinal cord, they had reduced neuropathology in the spinal cord, particularly the level of MNC infiltration around vessels [mean perivascular cuffing score ± standard error of the mean (SEM): iTreg‐late, 4.8 ± 2.4; control, 16.3 ± 2.7; P < 0.05, t‐test] (Figure 2B,F; Supporting Information Table S1). Clinically, we monitored impairment of righting reflex as an indicator for neurological deficit, both groups of mice developed progressive impairment of their righting reflex (Supporting Information Figure S1) 60. iTreg‐late mice tended to have lower righting reflex scores than control mice (eg, righting reflex score on day 81 p.i. ± SEM: iTreg‐late, 1.7 ± 0.1; control, 2.0 ± 0.1; P = 0.051, t‐test; results are representative of three independent experiments).

Figure 2.

Spinal cord pathology during the chronic stage of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection. A,B,E. Luxol fast blue staining of thoracic spinal cord segments. TMEV‐infected mice receiving induced regulatory T cells (iTregs) during the early chronic stage (iTreg‐late) had less inflammation (arrows), compared with control mice. C,D. Immunostaining using CD3 antibody showed less CD3+ cells in the spinal cords of iTreg‐late mice (D), compared with control mice (C). F. Quantification of inflammation in the spinal cord of mice infected with TMEV; mice were killed on day 48. iTreg‐late mice (hatched bars) had lower pathology scores in all pathological classes, particularly perivascular cuffing (*P < 0.05), compared with control mice (closed bars). Spinal cord sections were divided into four quadrants consisting of the ventral funiculus, the dorsal funiculus and each lateral funiculus. The total number of positive quadrants for each pathologic class was determined, then divided by the total number of quadrants present on the slide and multiplied by 100 to give the percentage involvement for each pathologic class. The overall pathology was determined by counting the number of quadrants containing any lesions. Six mice per group were used. These results are representative of three independent experiments. Magnification ×20.

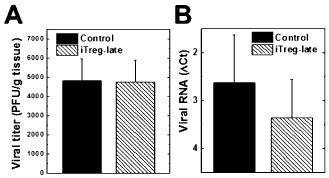

Immunohistochemistry against CD3 showed that the iTreg‐late mice had less CD3+ cells in their spinal cords compared with control mice (Figures 2C,D). Quantification of CD3 staining showed that the percentages of CD3+ cells in total cell infiltrates in the CNS were similar between iTreg‐late and control mice (Supporting Information Figure S2). We also examined whether iTreg‐late mice had altered viral replication in the CNS, since suppression of immune cell recruitment in the CNS by iTregs could decrease the CNS antiviral immune response, resulting in enhancement of viral replication 66. The amounts of infectious virus and viral RNA in the spinal cords, measured by RT‐PCR and plaque assay, were similar between the iTreg‐late and control mice (Figure 3). Thus, therapeutic iTreg treatment suppressed inflammation without increasing virus persistence.

Figure 3.

Viral titration in the spinal cord during the chronic stage of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection. Both induced regulatory T cell (iTreg)‐late (hatched bars) and control (closed bars) mice had similar amounts of infectious virus (P = 0.67) (A) and viral RNA (P = 0.58) (B). A. Infectious virus was quantified by plaque assays [plaque forming unit (PFU)]. B. ΔCt (cycle threshold) values of viral capsid protein 2 (VP2) compared with cellular levels of the house keeping gene, phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) 1, by reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction. ΔCt was calculated by subtracting the PGK1Ct from the TMEVCt.

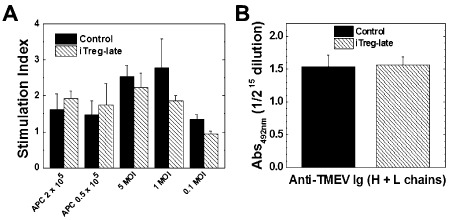

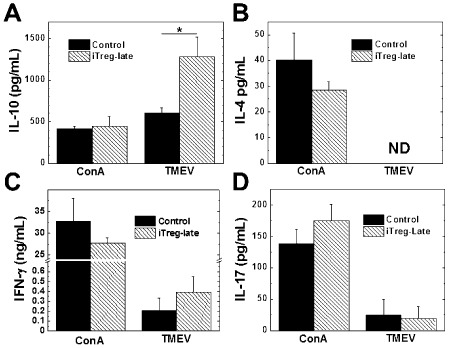

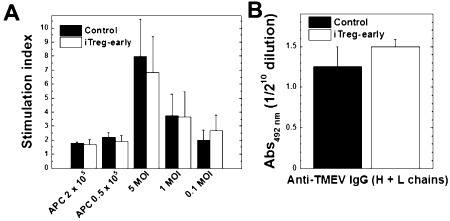

Because iTregs can suppress immune responses in vitro (Figure 1D), we speculated that iTregs could also suppress immune responses in vivo, which would explain the decreased CNS inflammation. Using spleen MNCs from iTreg‐late and control mice, we have compared virus‐specific lymphoproliferative and Ab responses as well as virus‐ and mitogen‐induced cytokine production between groups. Interestingly, however, there were no significant differences in the levels of lymphoproliferation in response to TMEV (cellular immunity) or serum anti‐TMEV titers (humoral immunity) between the iTreg‐late and control mice (Figure 4). On the other hand, MNCs from the iTreg‐late mice produced significantly more IL‐10 in response to stimulation with TMEV than the control group (Figure 5A; P< 0.05), whereas MNCs from both groups of mice produced similar amounts of IL‐10 when stimulated with ConA. The levels of IFN‐γ, IL‐4 and IL‐17 production after stimulation with ConA or TMEV were similar in both iTreg‐late and control mice (Figures 5B–D). Thus, therapeutic iTreg treatment altered the cytokine balance without suppressing the overall levels of anti‐TMEV immune responses.

Figure 4.

Immune responses to Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) during the chronic stage of infection. Induced regulatory T cell (iTreg)‐late (hatched bars) and control mice (closed bars) had similar anti‐TMEV lymphoproliferative (A) and antibody responses to TMEV (B). A. Mononuclear cells were isolated from spleens of iTreg‐late mice or control mice during the chronic stage and stimulated with TMEV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5, 1, 0.1 or by irradiated TMEV‐infected spleen cells that were incubated with TMEV overnight to act as antigen presenting cells (APCs). Lymphoproliferation was quantified by a [3 H]thymidine incorporation assay. The two groups of mice had similar levels of TMEV‐specific lymphoproliferation (at 1 MOI, P = 0.40). Stimulation index = [counts per minute (cpm) of treatment group]/(cpm of no treatment group). Results are mean + standard error of the mean (SEM) from three pools of spleens from two mice per pool. B. The levels of total immunoglobulin (Ig)G (heavy and light chains) against TMEV in sera were titrated by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays. The two groups of mice had similar anti‐TMEV antibody responses (P = 0.83). Values are mean absorbance (Abs) + SEM of six sera per group.

Figure 5.

Cytokine responses to Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) during the chronic stage of infection. The induced regulatory T cell (iTreg)‐late mice (hatched bars) produced significantly more interleukin (IL)‐10 (A) in response to TMEV than the control mice (closed bars) (*P < 0.05); production of IL‐4, interferon (IFN)‐γ and IL‐17 was similar (B, C and D). Mice were killed during the chronic stage, and the mononuclear cells were isolated from the spleens and stimulated with conconavalin A (ConA) or TMEV for 48 h. The levels of cytokine production in the culture supernatant were measured by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays. Results are mean + standard error of the mean from three pools of spleens from two mice; these results are representative of three independent experiments. Abbreviation: ND = not detectable.

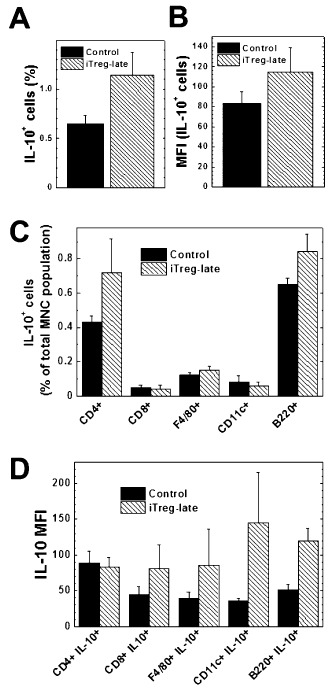

Modulation of antiviral IL‐10 responses by iTregs

Our findings showed IL‐10 as a potential mediator of the reduced amount of inflammation in the CNS of the mice given iTregs. To investigate which cell types were producing IL‐10, we stimulated cells with TMEV followed by PMA and ionomycin and then stained the cells for surface markers (B220, F4/80 and CD11c were used for B cells, macrophages and dendritic cells, respectively) and IL‐10 (Figure 6). The control and iTreg‐late mice had similar numbers of spleen cells and percentages of populations of CD3, CD4 and CD8 T cells; B cells; macrophages; and dendritic cells. Interestingly, there were no differences in the percentages of CD4+FOXP3+ Tregs in the total spleen MNC population between iTreg‐late and control mice (iTreg‐late, 0.07 ± 0.03; control, 0.06 ± 0.05). However, the iTreg‐late mice had higher percentages of IL‐10+ cells and a higher mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of IL‐10. The iTreg‐late mice had higher percentages of IL‐10+ cells, including CD4+ and B220+ cells. In addition, most cell types, particularly CD11c+ dendritic cells, had a higher MFI of IL‐10, indicating more IL‐10 per cell in the iTreg‐late compared with the control group (Figure 6D) 51.

Figure 6.

Flow cytometric analyses of intracellular interleukin (IL)‐10+ cells in response to Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) during the chronic stage of TMEV infection. Induced regulatory T cell (iTreg)‐late mice (hatched bars) had higher percentages (A) and mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) (B) of IL‐10+ cells compared with control mice (closed bars). Among IL‐10+ cells the iTreg‐late mice had a higher percentage of CD4+ and B220+ cells than controls (C). The MFI was higher in the iTreg‐late mice in all cell types except CD4+ cells (D). Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated from the spleens and stimulated with TMEV, phorbol myristate acetate, ionomycin and brefeldin A. The cells were stained for the cell surface markers CD4, CD8, CD11c, B220 and F4/80, and the cells were then fixed, permeabilized and stained for IL‐10 and FOXP3. The results are mean + standard error of the mean and are representative of two independent experiments.

Early iTreg treatment exacerbates acute disease in TMEV infection

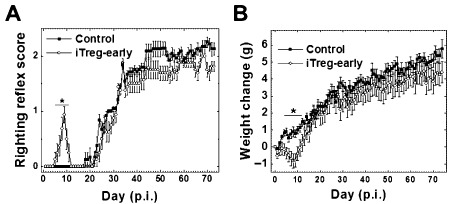

Previously, Karlsson et al showed that a single iTreg treatment suppressed IBD 21. Additionally, Tregs have been shown to be beneficial when used prophylactically in an autoimmune model for MS, EAE 24. We determined whether early treatment with iTregs could be beneficial in TMEV infection by injecting mice with iTregs on the same day of TMEV infection (iTreg‐early mice) (approximately 3–4 weeks before the onset of demyelinating disease) and by monitoring their weight and clinical signs (Figure 7). During the acute stage of TMEV infection, 1–2 weeks p.i., TMEV has been shown to induce only mild or no disease clinically, but induce inflammation mainly in the brain, histologically. Interestingly, iTreg‐early mice developed obvious clinical signs during the acute stage. Although no control TMEV‐infected mice developed an impaired righting reflex, the iTreg‐early mice had a significantly impaired righting reflex during the acute stage of disease (mean righting reflex scores ± SEM on day 8: iTreg‐early 0.9 ± 0.2; control 0, P < 0.05, t‐test). In addition, iTreg‐early mice had more weight loss compared with control mice, which had a weight increase during the acute stage [mean weight change (g) ± SEM on day 8: iTreg‐early, −0.8 g ± 0.3; control, 0.8 g ± 0.3, P < 0.05, t‐test]. By 2 weeks p.i., iTreg‐early mice recovered from acute disease, and both iTreg‐early and control mice showed no clinical signs between 2 and 3 weeks p.i. During the chronic stage, the iTreg‐early mice had slightly lower clinical scores than control mice, although this difference was not significant.

Figure 7.

Effects of early induced regulatory T cell (iTreg) treatment on clinical signs of SJL/J mice infected with Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV). Mice treated on day 0 with iTreg (iTreg‐early, open circles) had significantly higher impaired righting reflex scores (A) and lost more weight (B) than control‐infected mice (closed squares) during the acute stage (*P < 0.05). A. Righting reflex score: 1 and 1.5, the mouse is flipped onto its back but immediately rights itself on one side or both sides, respectively; 2, the mouse rights itself in 1–5 s; 3, righting takes more than 5 s. B. Weight change = weight dayn − weight day0. Six mice per group were used. The results are mean ± standard error of the mean. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

We next determined why iTreg‐early mice developed more severe acute clinical disease. Neuropathology (inflammation and cell death) was examined at the peak of the acute stage. In both groups of mice, neuropathology was predominantly observed in the gray matter of the brain, including the hippocampus, cerebral cortex, thalamus and hypothalamus, whereas spinal cord involvement was mild. Histologically, iTreg‐early mice displayed less CNS inflammation, despite showing worse clinical signs compared with control mice. In control TMEV‐infected mice, layers of cell infiltrates were observed around the perivascular area, whereas in iTreg‐early mice only dilation of venules with few or no infiltrating cells was observed (Figure 8). Immunohistochemistry against CD3 showed substantial CD3+ cell infiltration in the brains of control mice, whereas very little CD3+ T cells were observed in the brains of iTreg‐early mice (Figure 8C,D). Quantification of brain inflammation confirmed that the level of perivascular cuffing was significantly lower in the iTreg‐early mice compared with control mice (P < 0.05; Figure 8F).

Figure 8.

Central nervous system inflammation during the acute stage of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection. Control TMEV‐infected mice (A, TMEV alone) had more inflammation (arrows) than mice treated with induced regulatory T cell (iTreg) (B, iTreg‐early). iTreg‐early mice had only a few cell infiltrates around dilated vessels (B, inset). Note no dilatation of vessels in uninfected mice (E inset, no infection). A,B,E. Luxol fast blue staining of the hippocampus of representative mice killed during the acute stage. C,D. Consecutive sections immunostained using CD3 antibody showed that iTreg‐early mice had few T cells around vessels, whereas control‐infected mice had a substantial T‐cell infiltration around vessels as well as in the parenchyma. F. Quantification of inflammation in the brain of TMEV‐infected mice showed that iTreg‐early mice (open bars) had significantly lower perivascular and overall inflammatory scores than control mice (closed bars) (*P < 0.05). The results are representative of two independent experiments. Magnifications ×18; insets ×74.

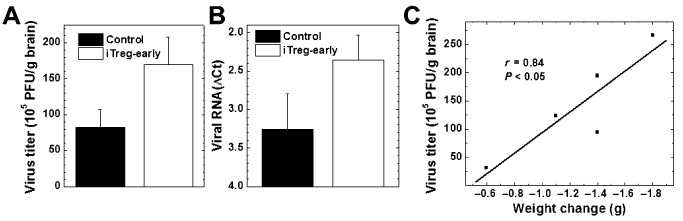

We next tested whether suppression of immune cell recruitment in the CNS in iTreg‐early mice resulted in enhancement of viral replication during the acute stage 6. We found more infectious virus and viral RNA present in the brain in iTreg‐early mice, compared with control mice during the acute stage (Figure 9). The level of infectious virus present in the brains of iTreg‐early mice correlated with the amount of weight loss of the mice (r = 0.85, P < 0.05) (Figure 9C). Thus, the higher amount of viral replication, but not the extent of inflammation, was associated with the increased severity of acute disease in iTreg‐early mice.

Figure 9.

Viral titration in the brain during the acute stage of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection. We detected higher levels of infectious virus (A) and viral RNA (B) from the brains of induced regulatory T cell (iTreg)‐early mice (open bars) compared with control mice (closed bars). The amount of infectious virus correlated with the amount of weight loss in iTreg‐early mice (r = 0.84, P < 0.05) (C). A. Infectious virus was quantified by plaque assays (P = 0.10). B. ΔCt values of viral capsid protein 2 compared with cellular levels of the house keeping gene, phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) 1, by reverse transcription‐polymerase chain reaction (P = 0.17). ΔCt was calculated by subtracting the PGK1Ct from the TMEVCt. C. Correlation of virus titers in the brain with weight loss in iTreg‐early mice. Five brains per group were harvested on the peak of the acute stage.

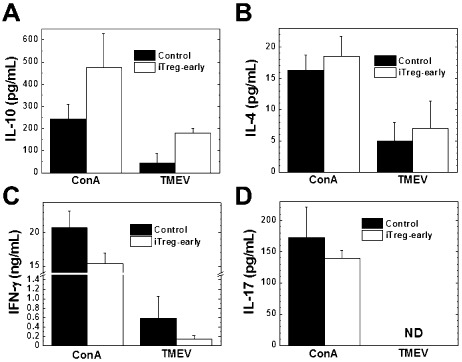

We tested whether increased viral levels in iTreg‐early mice could be caused by an alteration of the in vivo levels of anti‐TMEV immune responses compared with control mice. However, we detected similar levels of lymphoproliferative (cellular) and Ab (humoral) responses to TMEV in both iTreg‐early and control mice (Figure 10). MNCs from iTreg‐early mice produced more anti‐inflammatory IL‐10 and IL‐4 and less proinflammatory IFN‐γ and IL‐17 than control mice during the acute stage (Figure 11). Thus, similar to therapeutic treatment, early iTreg treatment altered the balance of cytokines without suppressing overall anti‐TMEV immune responses. In the iTreg‐early mice, exacerbation of acute viral disease with increased viral levels was associated with their anti‐inflammatory cytokine profile, which likely suppressed (antiviral) immune cell recruitment into the CNS.

Figure 10.

Immune responses to Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) during the acute stage of infection. A. Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated from spleens of induced regulatory T cell (iTreg)‐early mice (open bars) or control mice (closed bars) on the peak of the acute stage and stimulated with TMEV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5, 1, 0.1 or by irradiated TMEV‐infected spleen cells that were incubated with TMEV overnight to act as APCs. Lymphoproliferation was quantified by a [3 H]thymidine incorporation assay. The two groups of mice had similar levels of TMEV‐specific lymphoproliferation (at 1 MOI, P = 0.98). Stimulation index = [counts per minute (cpm) of treatment group]/(cpm of no treatment group). Results are mean + standard error of the mean (SEM) from three pools of spleens from two mice per pool. B. The levels of total IgG against TMEV in sera were titrated by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays. The two groups of mice had similar anti‐TMEV antibody responses (P = 0.37). Values are mean absorbance (Abs) + SEM of six sera per group.

Figure 11.

Cytokine responses to Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) during the acute stage of infection. Mononuclear cells (MNCs) from the induced Treg (iTreg)‐early mice (open bars) produced more anti‐inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)‐10 (A) and IL‐4 (B) and less inflammatory cytokine interferon (IFN)‐γ (C) and IL‐17 (D) in response to concanavalin A (ConA) or TMEV compared with control mice (closed bars). MNCs were isolated from the spleens of iTreg‐early or control mice and stimulated with ConA or TMEV for 48 h. The levels of cytokine production in the culture supernatants were measured by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays. Results are representative of mean + standard error of the mean from two to three pools of spleens with two spleens per pool from four experiments. Abbreviation: ND = not detectable.

iTreg treatment does not alter susceptibility to TMEV‐IDD in C57BL/6 mice

The susceptibility to TMEV‐IDD has been shown to differ among mouse strains; for example, SJL/J mice are known to be susceptible, whereas C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice are known to be resistant 34. The aforementioned results showed that early iTreg treatment could exacerbate acute viral disease by suppression of CNS immune cell recruitment, facilitating increased viral replication in SJL/J mice. This raised the question whether early iTreg treatment of TMEV‐resistant C57BL/6 mice could render them susceptible to TMEV‐IDD, where TMEV infection may result in more active virus replication and virus persistence in the CNS, leading to TMEV‐IDD in C57BL/6 mice. We treated TMEV‐infected C57BL/6 mice with iTregs (iTreg mice) on day 0, and compared clinical signs, immune responses and neuropathology with TMEV‐infected mice with no iTreg treatment (control) (Supporting Information Figures S3 and S4). We found that B6 mice remained resistant to TMEV‐IDD regardless of iTreg treatment; no iTreg mice developed TMEV‐IDD.

Discussion

Because 1–2 × 107 iTregs could be generated ex vivo from the spleen of one mouse, this method for iTreg induction allowed for a large amount of iTregs to be generated with minimal reagents, unlike when using freshly isolated Tregs where only about 1 × 106 Tregs can be harvested from one mouse 7. The iTregs were highly immunosuppressive in vitro and were able to modulate antiviral and autoimmune immune responses in vivo 21. The high percentage of CD25 expression in the iTregs is typical of Tregs. Expression of CD49d on iTregs suggests that they can migrate into to the CNS by binding to vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)‐1. The large number of functional Tregs that can be generated makes this system ideal not only for investigating the role of Tregs in general but also for translational applications. The high yield of iTregs makes this system promising for potential use in Treg‐based therapies, which have been suggested for many immune‐mediated diseases, including MS 41.

Sufficient antiviral immune responses need to be generated by a host to eradicate invading viruses. However, if this immune response goes uncontrolled, the resulting immunopathology can cause more damage than the pathology induced by viral replication (viral pathology). The TMEV‐IDD model of MS can serve as a model to demonstrate the deleterious effects of both viral pathology and immunopathology 4, 16, 36, 57. The pathomechanisms have been demonstrated to change during the course of TMEV infection: during the acute stage, neuronal and axonal degeneration is mainly induced by viral pathology, whereas during the chronic stage, demyelination is primarily induced by immunopathology. Tregs can play an important role in balancing immunopathology and pathogen‐specific immune responses. In the current study, we have used ex vivo generated iTregs to investigate the role and therapeutic potential of Tregs during the acute and chronic stages of TMEV infection.

During the chronic stage of disease, less immune cell infiltration was observed in the spinal cords of iTreg‐late mice compared with control mice (Figure 2). We initially speculated that this could lead to increased viral persistence; however, we found no difference in the amount of virus persistence between iTreg‐late and control mice. We also demonstrated that both the cellular and humoral anti‐TMEV immune responses were similar between the iTreg‐late and the control mice (Figure 3). Then, we compared the cytokine profiles between the two groups of mice. The iTreg‐late mice produced significantly more IL‐10 in response to TMEV than the control mice, but similar amounts of other cytokines (Figure 5). The amount of IL‐10 produced in response to TMEV was even higher than what was produced in response to a T‐cell mitogen, ConA 39. This was the only cytokine that was produced in higher levels in response to TMEV than ConA. IL‐10 has been shown to suppress neuroinflammation 3; therefore, the enhanced IL‐10 response to TMEV could be responsible for the reduction in inflammation in the iTreg‐late mice.

Because most types of immune cells can produce IL‐10, we attempted to identify the source of IL‐10 production to help determine the mechanism by which the iTregs modulated the immune response 11, 31. Although only a small percentage of the cells were IL‐10+, there were more IL‐10+ cells in the iTreg‐late mice after stimulating the cells with TMEV, compared with control mice (Figure 6). There were higher percentages of CD4+ and B220+ (a B‐cell marker) cells among the IL‐10+ cells, which was somewhat expected, as these cell types have been associated with IL‐10 production 13. Interestingly, the IL‐10 MFI was also higher in all the cell types investigated in the iTreg‐late mice compared with the control mice, except CD4+ cells (Figure 6D). The higher MFI was not caused by an increase in autofluorescence or nonspecific Ab binding, as the MFIs of samples incubated with isotype control Ab were similar between control and iTreg groups (data not shown). Overall, the higher MFI suggests that these cell types are producing more IL‐10 51. Because most cell types, except CD4+ cells, have a higher IL‐10 MFI, the iTregs may change the immune response systemically to a more regulatory phenotype. Although IL‐10 production was seen in very low percentages in all cell subsets, there was a higher percentage of IL‐10+ cells and a higher MFI in the iTreg‐late mice compared with the control mice, combined these increases could explain the significant increase in IL‐10 production in response to TMEV seen by ELISA. This systemic change to a more regulatory phenotype may explain how the iTreg‐late mice have similar anti‐TMEV immune responses and viral load, and less inflammation compared with control mice.

These results support the idea that immunopathology is a contributing factor to the overall pathology during the chronic stage of TMEV infection 34, 62. Here, it appears that iTregs are influencing the immune response to TMEV in other immune cell types, mostly in the lymphoid organs, and altering them to a more anti‐inflammatory response via IL‐10 production. Consistent with this theory, Karlsson et al, whose method for generating iTregs in C57BL/6 mice was applied to SJL/J mice, found substantial numbers of iTregs in the peripheral lymphoid organs after iTreg transfer. Anghelina et al also reported a systemic distribution of transferred Tregs in MHV‐infected mice. Although this does not deny the possibility that iTregs influence the immune system in the target organ (ie, CNS) in our current experiments, we were not able to precisely determine the localization of transferred iTregs by distinguishing between iTregs and nTregs in the recipient mice, because of a lack of GFP‐FOXP3 or DEREG mice on the SJL/J genetic background.

Although there was no difference between the numbers of CD4+FOXP3+ Tregs or IL‐10+ Tregs present in the iTreg‐late or control mice, the early production of IL‐10 or other immune mediators by iTregs in the iTreg‐late mice could result in a lasting effect. We are investigating how the iTregs affected the other cell types to enhance their IL‐10 production. Kearley et al observed a similar effect of Tregs in a mouse model of airway inflammation, where transferred Tregs were able to suppress inflammation by inducing IL‐10 expression in CD4+ T cells in recipient mice 22. In their model, the transfer of IL‐10‐deficient Tregs could induce IL‐10 production in CD4+ T cells. Anghelina et al also demonstrated that in MHV infection, another viral model for MS, transfer of IL‐10‐deficient Tregs was able to suppress disease, while transferring Tregs to IL‐10‐deficient recipient mice did not suppress virus‐induced demyelination 1. Although the authors were unable to determine the source of IL‐10, their data suggest that IL‐10 was essential for disease suppression and that its production was induced in recipient cells by transferred Tregs. These experiments demonstrated that Tregs can influence the amount of IL‐10 production without necessarily producing it by themselves. Interestingly, the iTreg‐early mice killed 1 week after iTreg injection (in contrast to the iTreg‐late mice that were killed over a month after iTreg injection) also had increased IL‐10 responses to TMEV, compared with control mice, although their IL‐10 response to ConA was greater than the response to TMEV (Figure 6). This suggests a change from a nonspecific to a virus‐specific IL‐10 response during the course of TMEV infection, which may need to be addressed to determine how IL‐10 contributes to the immunomodulatory effects of iTregs in TMEV and other virus infections, in general. The long‐term effects of the iTregs were similar to what was seen in a mouse model of IBD, where injection of iTregs suppressed disease 8 weeks after injection 21.

Although the enhanced IL‐10 production appears to be TMEV specific, we did not find an increase in virus‐specific iTregs. This is reasonable as the iTregs were generated without TMEV‐specific antigen stimuli and the number we injected was low (2 × 105). In theory, a small number of TMEV‐specific iTregs that were present in the inoculum could have expanded and altered the cytokine milieu to a more favorable environment for the expansion of resident TMEV‐specific Tregs 52. However, this is unlikely to be the case as there were similar amounts of CD4+FOXP3+ Tregs recovered from both iTreg‐late and control mice.

One of our concerns was that by suppressing or altering the immune response by giving the mice iTregs would make the mice more susceptible to cancer, as Tregs have been shown to play a role in the development of some cancers 48. SJL/J mice spontaneously develop reticulum cell sarcomas, typically around 5–6 months of age 37. Despite the changes in the immune response to TMEV, the iTreg‐late mice did not have a higher incidence of developing reticulum cell sarcomas or other tumors than the control mice, which were identified by macroscopic swelling of the lymph nodes and spleen and confirmed microscopically. However, these experiments typically lasted until the mice were less than 3 months old; thus, a longer experiment would be required to determine longer effects of iTreg injection on the development of reticulum cell sarcoma and other malignancies in these mice.

To our surprise, mice receiving early treatment with iTregs developed obvious clinical signs including significantly more weight loss and impaired righting reflex scores, during the acute stage of TMEV infection, whereas control‐infected mice without iTreg treatment were asymptomatic (Figure 7). In TMEV infection, SJL/J mice generally do not develop obvious clinical disease during the acute stage; infected mice sometimes show mild weight loss without impairment of righting reflex. Interestingly, control mice had a higher level of cell infiltration, including T cells, in the brain. On the other hand, we detected higher amounts of infectious virus and viral RNA in the brains of iTreg‐early mice, compared with control mice. Thus, viral pathology (replication), but not inflammation (immunopathology), seemed to contribute to exacerbation of acute disease in iTreg‐early mice. We first suspected that the iTregs inhibited the immune response to TMEV, which reduced the amount of CNS inflammation. However, both the cellular and humoral immune responses to TMEV were similar between iTreg‐early and control mice. Although the mice had similar overall antiviral immune responses, the iTreg‐early mice produced fourfold more IL‐10 and threefold less IFN‐γ in response to TMEV compared with the control mice (Figure 11). This suggests that modulation of the immune response to TMEV could prevent CNS recruitment of antiviral immune cells and allow for more viral replication. This is similar to what has been previously demonstrated in CNS infections with GDVII vs. DA strains of TMEV, where the neurovirulent GDVII strain caused mice to die because of more severe viral replication (viral pathology) with significantly reduced T‐cell recruitment in the CNS 59. In herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, Lund et al found that Tregs were essential for prolonging the life span of infected mice by coordinating the migration (recruitment) of effector T cells to the site of infection, where in the absence of Tregs the effector cells accumulated in the draining lymph nodes and were less prevalent at the site of infection 27. The authors concluded that Tregs were orchestrating timely immune cell recruitment to the site of infection to aid the immune response to HSV. In TMEV infection, Tregs may also affect the recruitment of effector cells to the CNS and preventing them from entering the site of infection in a deleterious manner, which is in contrast to what occurs in HSV infection.

Tregs have been proposed to be a key determinant to the susceptibility of SJL/J mice to a chronic TMEV infection 40. Using anti‐CD25 Ab, Richards et al inactivated Tregs in SJL/J mice during the acute stage of TMEV infection and found a reduced viral burden during the acute stage of disease and a delay in the onset of TMEV‐IDD and a reduction in the severity of disease 40. The results from our study are in agreement with their results, where depletion of Tregs reduced viral loads, whereas addition of iTregs increased viral loads in our study. Richards et al also found that depletion of Tregs enhanced CD4+ and CD8+ T cell as well as Ab responses to TMEV. In contrast, we demonstrated that the addition of iTregs did not reduce the anti‐TMEV immune response, either cellular or humoral, but altered the cytokine balance to a more anti‐inflammatory bias. These differences between the two studies could be due to the different mechanistic approaches and the characteristics of the in vivo inactivated Tregs and the ex vivo generated iTregs. Richards et al inactivated Tregs in vivo (“loss‐of‐function” approach), while we gave the mice ex vivo generated iTregs (“gain‐of‐function” approach). In addition, because CD25 is expressed on activated T cells and during T‐cell development, and on B cells and other cell types, inactivation or depletion of these cell populations could create additional effects other than Treg inactivation, which may account for the discrepancies 23, 64. Furthermore, Karlsson et al demonstrated that iTregs from C57BL/6 mice were more potent at suppressing colitis and had different expression patterns of homing molecules and cytokines compared with natural Tregs (nTregs) 20. Thus, the differences between ex vivo generated iTregs and in vivo generated nTregs may also explain the discrepancies between the experiments by Richards et al and ours.

Although this study and the one conducted by Richards et al demonstrate the impact that Tregs can have during the acute stage of TMEV infection, it is unlikely that iTregs alone can account for the difference in susceptibility to TMEV‐IDD between resistant C57BL/6 and susceptible SJL/J mice. We have conducted iTreg transfer experiments with TMEV‐infected C57BL/6 mice and found that they did not become susceptible to TMEV‐IDD or virus persistence (Supporting Information Figures S3 and S4). There was no difference in the immune response to TMEV during the acute stage of TMEV infection between the control C57BL/6 mice and the C57BL/6 mice given iTregs. This is consistent with the findings by Richards et al that there was no enhancement of anti‐TMEV immune responses when they depleted Tregs in C57BL/6 mice. These data suggest that SJL/J mice have different effector mechanisms that can be exacerbated by Tregs and contribute to their susceptibility compared with C57BL/6 mice.

In summary, we have demonstrated that Tregs can play distinct roles in viral infections, which depended on the disease stage. During the chronic stage of TMEV infection where immunopathology is the dominant pathomechanism, iTreg treatment reduced CNS inflammation without increasing the viral burden suppressing TMEV‐IDD. On the other hand, during the acute stage of TMEV infection where viral replication causes most of the pathology, iTreg treatment enhanced viral replication leading to more severe disease. These two contrasting effects of Tregs have been observed individually in several viral infections 1, 12, 26, 50, 66. To our knowledge, however, this is the first study to demonstrate that iTregs could have both detrimental and beneficial effects in the different stages of a single virus infection. Although Tregs have been proposed as a potential therapeutic target for many diseases that may have a viral component or occur in parallel with viral infections, the present data suggest that Tregs may be a double‐edged sword. The type and stage of virus infection must be carefully considered before using Tregs for a personalized medicine approach.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Clinical signs of TMEV‐infected mice given iTregs during the early chronic stage. iTreg‐late mice (open triangles) had lower impaired righting reflex scores than control mice (closed squares). A. Righting reflex score: 1 and 1.5, the mouse is flipped onto its back but immediately rights itself on one side or both sides, respectively; 2, if it rights itself in 1–5 s; 3, if righting takes more than 5 s. Results are mean + SEM from six mice; these results are representative of three independent experiments

Figure S2. Quantification of CD3+ infiltrates in iTreg‐late and control mice during the chronic stage of disease. The percentage of CD3+ cells among total infiltrating cells was similar between iTreg‐late (hatched bars) and control mice (closed bars). %CD3+ cells = CD3+ cells / total infiltrates ×100. Five mice per group were used. Abbreviation: NAWM = normal appearing white matter.

Figure S3. Effects of iTreg treatment early in TMEV‐infection of C57BL/6 mice. TMEV‐infected mice were treated with iTregs on day 0 (iTreg) or without (control) and killed on day 7 p.i. A. iTreg mice tended to show delayed weight gain, compared with control mice; however, there was no significant difference in weight change or righting reflex score between the two groups (P > 0.05). Weight change = weight dayn − weight day0. iTreg mice (open diamonds); control mice (closed squares). B. iTreg and control mice had similar TMEV‐specific lymphoproliferation. Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated from spleens of iTreg (crosshatched bars) or control mice (closed bars) during the acute stage of TMEV infection and stimulated with TMEV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5, 1 or 0.1, or with irradiated TMEV‐infected spleen cells to act as antigen presenting cells (APC). Lymphoproliferation was quantified by a [3H]thymidine incorporation assay. Results are mean + SEM from three pools of spleens from two mice per pool. There were no statistical differences in the pathology scores (C) between the groups, although control mice (D) had slightly more inflammation than iTreg mice (E). C. Brain pathology during the acute stage of TMEV infection. D,E. Luxol fast blue staining of the hippocampus of representative mice killed during the acute stage. Six mice per group were used. Magnification ×31.

Figure S4. Immunological and pathological profiles on day 60 p.i. in TMEV‐infected C57BL/6 mice with iTreg (iTreg) treatment or without (control). iTregs were given on day 0. A. In both iTreg (crosshatched bars) and control (closed bars) groups, splenic MNCs showed similar levels of lymphoproliferative responses against TMEV‐APC or TMEV (MOI of 1). B. IL‐10 production in response to ConA or TMEV by splenic MNCs from iTreg and control mice was also similar. Results are mean + SEM from three pools of spleens from two mice per pool. C,D. Luxol fast blue staining of spinal cords showed no neuropathology in control (C) or iTreg (D) mice. iTreg mice did not develop TMEV‐IDD. The spinal cord segments were representative of mice killed on day 60 p.i. (six mice per group). Magnification ×23.

Table S1. Acute stage weight change and righting reflex scores.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the fellowships (FS and SO) from the Malcolm Feist Cardiovascular Research Endowment, LSU Health Sciences Center, Shreveport, and grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences COBRE Grant (8P20 GM103433) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the NIH (R21NS059724; IT). We thank Sadie Faith Elliott for excellent technical assistance.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Anghelina D, Zhao J, Trandem K, Perlman S (2009) Role of regulatory T cells in coronavirus‐induced acute encephalitis. Virology 385:358–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belkaid Y, Tarbell K (2009) Regulatory T cells in the control of host–microorganism interactions. Annu Rev Immunol 27:551–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bettelli E, Das MP, Howard ED, Weiner HL, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK (1998) IL‐10 is critical in the regulation of autoimmune encephalomyelitis as demonstrated by studies of IL‐10‐ and IL‐4‐deficient and transgenic mice. J Immunol 161:3299–3306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carlson NG, Hill KE, Tsunoda I, Fujinami RS, Rose JW (2006) The pathologic role for COX‐2 in apoptotic oligodendrocytes in virus induced demyelinating disease: implications for multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 174:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carter RJ, Morton J, Dunnett SB (2001) Motor coordination and balance in rodents. Curr Protoc Neurosci 15:8.12.1–8.12.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cervantes‐Barragan L, Firner S, Bechmann I, Waisman A, Lahl K, Sparwasser T et al (2012) Regulatory T cells selectively preserve immune privilege of self‐antigens during viral central nervous system infection. J Immunol 188:3678–3685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chuck MI, Zhu M, Shen S, Zhang W (2010) The role of the LAT‐PLC‐gamma1 interaction in T regulatory cell function. J Immunol 184:2476–2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clatch RJ, Lipton HL, Miller SD (1986) Characterization of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)‐specific delayed‐type hypersensitivity responses in TMEV‐induced demyelinating disease: correlation with clinical signs. J Immunol 136:920–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clifford DB, Nath A, Cinque P, Brew BJ, Zivadinov R, Gorelik L et al (2013) A study of mefloquine treatment for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: results and exploration of predictors of PML outcomes. J Neurovirol 19:351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Collison LW, Vignali DA (2011) In vitro Treg suppression assays. Methods Mol Biol 707:21–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM (2008) IL‐10: the master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol 180:5771–5777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dietze KK, Zelinskyy G, Gibbert K, Schimmer S, Francois S, Myers L et al (2011) Transient depletion of regulatory T cells in transgenic mice reactivates virus‐specific CD8+ T cells and reduces chronic retroviral set points. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:2420–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DiLillo DJ, Matsushita T, Tedder TF (2010) B10 cells and regulatory B cells balance immune responses during inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1183:38–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fransson M, Piras E, Burman J, Nilsson B, Essand M, Lu B et al (2012) CAR/FoxP3‐engineered T regulatory cells target the CNS and suppress EAE upon intranasal delivery. J Neuroinflammation 9:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fujinami RS (1988) Virus‐induced autoimmunity through molecular mimicry. Ann N Y Acad Sci 540:210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fujinami RS, Zurbriggen A, Powell HC (1988) Monoclonal antibody defines determinant between Theiler's virus and lipid‐like structures. J Neuroimmunol 20:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fukuda T, Yoshida T, Okada S, Hatano M, Miki T, Ishibashi K et al (1997) Disruption of the Bcl6 gene results in an impaired germinal center formation. J Exp Med 186:439–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hou W, Kang HS, Kim BS (2009) Th17 cells enhance viral persistence and inhibit T cell cytotoxicity in a model of chronic virus infection. J Exp Med 206:313–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jin YH, Kaneyama T, Kang MH, Kang HS, Koh CS, Kim BS (2011) TLR3 signaling is either protective or pathogenic for the development of Theiler's virus‐induced demyelinating disease depending on the time of viral infection. J Neuroinflammation 8:178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karlsson F, Martinez NE, Gray L, Zhang S, Tsunoda I, Grisham MB (2013) Therapeutic evaluation of ex vivo‐generated versus natural regulatory T‐cells in a mouse model of chronic gut inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19:2282–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karlsson F, Robinson‐Jackson SA, Gray L, Zhang S, Grisham MB (2011) Ex vivo generation of regulatory T cells: characterization and therapeutic evaluation in a model of chronic colitis. Methods Mol Biol 677:47–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kearley J, Barker JE, Robinson DS, Lloyd CM (2005) Resolution of airway inflammation and hyperreactivity after in vivo transfer of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is interleukin 10 dependent. J Exp Med 202:1539–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kingma DW, Imus P, Xie XY, Jasper G, Sorbara L, Stewart C, Stetler‐Stevenson M (2002) CD2 is expressed by a subpopulation of normal B cells and is frequently present in mature B‐cell neoplasms. Cytometry 50:243–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kohm AP, Carpentier PA, Anger HA, Miller SD (2002) Cutting edge: CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress antigen‐specific autoreactive immune responses and central nervous system inflammation during active experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 169:4712–4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kurtz CI, Sun XM, Fujinami RS (1995) Protection of SJL/J mice from demyelinating disease mediated by Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus. Microb Pathog 18:11–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lanteri MC, O'Brien KM, Purtha WE, Cameron MJ, Lund JM, Owen RE et al (2009) Tregs control the development of symptomatic West Nile virus infection in humans and mice. J Clin Invest 119:3266–3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lund JM, Hsing L, Pham TT, Rudensky AY (2008) Coordination of early protective immunity to viral infection by regulatory T cells. Science 320:1220–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martinez NE, Sato F, Kawai E, Omura S, Chervenak RP, Tsunoda I (2012) Regulatory T cells and Th17 cells in viral infections: implications for multiple sclerosis and myocarditis. Future Virol 7:593–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McCarthy DP, Richards MH, Miller SD (2012) Mouse models of multiple sclerosis: experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and Theiler's virus‐induced demyelinating disease. Methods Mol Biol 900:381–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller SD, Vanderlugt CL, Begolka WS, Pao W, Yauch RL, Neville KL et al (1997) Persistent infection with Theiler's virus leads to CNS autoimmunity via epitope spreading. Nat Med 3:1133–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A (2001) Interleukin‐10 and the interleukin‐10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol 19:683–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Murray TJ (2009) The history of multiple sclerosis: the changing frame of the disease over the centuries. J Neurol Sci 277(Suppl. 1):S3–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Oleszak EL, Leibowitz JL, Rodriguez M (1988) Isolation and characterization of two plaque size variants of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (DA strain). J Gen Virol 69(Pt 9):2413–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olsberg C, Pelka A, Miller S, Waltenbaugh C, Creighton TM, Dal Canto MC et al (1993) Induction of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV)‐induced demyelinating disease in genetically resistant mice. Reg Immunol 5:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pirko I, Johnson AJ, Chen Y, Lindquist DM, Lohrey AK, Ying J, Dunn RS (2011) Brain atrophy correlates with functional outcome in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage 54:802–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pirko I, Suidan GL, Rodriguez M, Johnson AJ (2008) Acute hemorrhagic demyelination in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 5:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ponzio NM, David CS, Shreffler DC, Thorbecke GJ (1977) Properties of reticulum cell sarcomas in SJL/J mice. V. Nature of reticulum cell sarcoma surface antigen which induces proliferation of normal SJL/J T cells. J Exp Med 146:132–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rauch HC, Montgomery IN, Hinman CL, Harb W, Benjamins JA (1987) Chronic Theiler's virus infection in mice: appearance of myelin basic protein in the cerebrospinal fluid and serum antibody directed against MBP. J Neuroimmunol 14:35–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reeke GN Jr, Becker JW, Cunningham BA, Gunther GR, Wang JL, Edelman GM (1974) Relationships between the structure and activities of concanavalin A. Ann N Y Acad Sci 234:369–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Richards MH, Getts MT, Podojil JR, Jin YH, Kim BS, Miller SD (2011) Virus expanded regulatory T cells control disease severity in the Theiler's virus mouse model of MS. J Autoimmun 36:142–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Riley JL, June CH, Blazar BR (2009) Human T regulatory cell therapy: take a billion or so and call me in the morning. Immunity 30:656–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roos RP, Wollmann R (1984) DA strain of Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus induces demyelination in nude mice. Ann Neurol 15:494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rosenthal A, Fujinami RS, Lampert PW (1986) Mechanism of Theiler's virus‐induced demyelination in nude mice. Lab Invest 54:515–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Round JL, Mazmanian SK (2010) Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T‐cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:12204–12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rovaris M, Confavreux C, Furlan R, Kappos L, Comi G, Filippi M (2006) Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: current knowledge and future challenges. Lancet Neurol 5:343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M (2008) Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 133:775–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sato F, Omura S, Martinez NE, Tsunoda I (2010) Animal Models of Multiple Sclerosis. Chapter 4. In: Neuroinflammation. Minagar A (ed.), pp. 55–66. Elsevier: Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schreiber TH, Wolf D, Bodero M, Podack E (2012) Tumor antigen specific iTreg accumulate in the tumor microenvironment and suppress therapeutic vaccination. Oncoimmunology 1:642–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Seol D, Choe H, Zheng H, Jang K, Ramakrishnan PS, Lim TH, Martin JA (2011) Selection of reference genes for normalization of quantitative real‐time PCR in organ culture of the rat and rabbit intervertebral disc. BMC Research Notes 4:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shi Y, Fukuoka M, Li G, Liu Y, Chen M, Konviser M et al (2010) Regulatory T cells protect mice against coxsackievirus‐induced myocarditis through the transforming growth factor beta‐coxsackie‐adenovirus receptor pathway. Circulation 121:2624–2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shooshtari P, Fortuno ES 3rd, Blimkie D, Yu M, Gupta A, Kollmann TR, Brinkman RR (2010) Correlation analysis of intracellular and secreted cytokines via the generalized integrated mean fluorescence intensity. Cytometry A 77:873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Bi M, Finger EB, Szot G, Ye J et al (2004) In vitro‐expanded antigen‐specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med 199:1455–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tolley ND, Tsunoda I, Fujinami RS (1999) DNA vaccination against Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus leads to alterations in demyelinating disease. J Virol 73:993–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Trandem K, Anghelina D, Zhao J, Perlman S (2010) Regulatory T cells inhibit T cell proliferation and decrease demyelination in mice chronically infected with a coronavirus. J Immunol 184:4391–4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tselis A (2011) Evidence for viral etiology of multiple sclerosis. Semin Neurol 31:307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tsunoda I, Kuang L‐Q, Fujinami RS (2002) Induction of autoreactive CD8+ cytotoxic T cells during Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus infection: implications for autoimmunity. J Virol 76:12834–12844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tsunoda I, Kuang L‐Q, Libbey JE, Fujinami RS (2003) Axonal injury heralds virus‐induced demyelination. Am J Pathol 162:1259–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tsunoda I, Libbey JE, Fujinami RS (2007) TGF‐ß1 suppresses T cell infiltration and VP2 puff B mutation enhances apoptosis in acute polioencephalitis induced by Theiler's virus. J Neuroimmunol 190:80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tsunoda I, Libbey JE, Fujinami RS (2009) Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus attachment to the gastrointestinal tract is associated with sialic acid binding. J Neurovirol 15:81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tsunoda I, Tanaka T, Fujinami RS (2008) Regulatory role of CD1d in neurotropic virus infection. J Virol 82:10279–10289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tsunoda I, Tanaka T, Terry EJ, Fujinami RS (2007) Contrasting roles for axonal degeneration in an autoimmune versus viral model of multiple sclerosis: when can axonal injury be beneficial? Am J Pathol 170:214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vanderlugt CL, Begolka WS, Neville KL, Katz‐Levy Y, Howard LM, Eagar TN et al (1998) The functional significance of epitope spreading and its regulation by co‐stimulatory molecules. Immunol Rev 164:63–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vanderlugt CL, Miller SD (2002) Epitope spreading in immune‐mediated diseases: implications for immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yagita H, Asakawa J, Tansyo S, Nakamura T, Habu S, Okumura K (1989) Expression and function of CD2 during murine thymocyte ontogeny. Eur J Immunol 19:2211–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yamada M, Zurbriggen A, Fujinami RS (1990) Monoclonal antibody to Theiler's murine encephalomyelitis virus defines a determinant on myelin and oligodendrocytes, and augments demyelination in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med 171:1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zelinskyy G, Dietze K, Sparwasser T, Dittmer U (2009) Regulatory T cells suppress antiviral immune responses and increase viral loads during acute infection with a lymphotropic retrovirus. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Clinical signs of TMEV‐infected mice given iTregs during the early chronic stage. iTreg‐late mice (open triangles) had lower impaired righting reflex scores than control mice (closed squares). A. Righting reflex score: 1 and 1.5, the mouse is flipped onto its back but immediately rights itself on one side or both sides, respectively; 2, if it rights itself in 1–5 s; 3, if righting takes more than 5 s. Results are mean + SEM from six mice; these results are representative of three independent experiments

Figure S2. Quantification of CD3+ infiltrates in iTreg‐late and control mice during the chronic stage of disease. The percentage of CD3+ cells among total infiltrating cells was similar between iTreg‐late (hatched bars) and control mice (closed bars). %CD3+ cells = CD3+ cells / total infiltrates ×100. Five mice per group were used. Abbreviation: NAWM = normal appearing white matter.