Abstract

Estrogen has potent immunomodulatory effects on proinflammatory responses, which can be mediated by serine proteases. We now demonstrate that estrogen increased the extracellular expression and IL-12-induced activity of a critical member of serine protease family Granzyme A, which has been shown to possess a novel inflammatory persona. The inhibition of serine protease activity with inhibitor 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride significantly diminished enhanced production of proinflammatory interferon-γ, IL-1β, IL-1α, and Granzyme A activity even in the presence of a Th1-inducing cytokine, IL-12 from splenocytes from in vivo estrogen-treated mice. Inhibition of serine protease activity selectively promoted secretion of Th2-specific IL-4, nuclear phosphorylated STAT6A, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)6A translocation, and STAT6A DNA binding in IL-12-stimulated splenocytes from estrogen-treated mice. Inhibition with 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride reversed the down-regulation of Th2 transcription factors, GATA3 and c-Maf in splenocytes from estrogen-exposed mice. Although serine protease inactivation enhanced the expression of Th2-polarizing factors, it did not reverse estrogen-modulated decrease of phosphorylated STAT5, a key factor in Th2 development. Collectively, data suggest that serine protease inactivity augments the skew toward a Th2-like profile while down-regulating IL-12-induced proinflammatory Th1 biomolecules upon in vivo estrogen exposure, which implies serine proteases as potential regulators of inflammation. Thus, these studies may provide a potential mechanism underlying the immunomodulatory effect of estrogen and insight into new therapeutic strategies for proinflammatory and female-predominant autoimmune diseases.

Inflammation, modulated by a complex series of immune events and proinflammatory biomolecules (ie, Th1 cytokines, transcription factors), is an essential physiological response to protect the host from harmful stimuli. However, if sustained, this essential system can lead to a wide variety of immune-mediated diseases such as female-predominant proinflammatory autoimmune diseases (ie, systemic lupus erythematosus) (1, 2).

Estrogen could enhance proinflammatory immunity (2–5) by regulating Th1-inducing and Th1 cytokines (4, 6, 7), which are also key autoimmune mediators. The induction and magnitude of Th1 responses (ie, interferon-γ [IFN-γ]) are modulated by IL-12, which activates STAT4 signaling and downstream pathways (8, 9). Estrogen can up-regulate these Th1-inducing biomolecules (ie, selective activation of nuclear STAT4β, STAT1, T-bet, STAT4 DNA binding, IL-12 (10–12), translocation of nuclear factor-κB members (7, 11, 13–16)), IFN-γ, and downstream Th1 molecules (17–20) from stimulated murine splenocytes (10, 12, 21) and women (22).

One of the key regulators of proinflammatory events is serine proteases (23–28). A key family of serine proteases, Granzymes (GZMs) are expressed in humans (5 GZMs: A, B, H, K, and M) and mice (11 GZMs: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, K, L, M, and N) (29). Of these serine proteases, GZMA and GZMB are the most abundant ones. The Th1-inducing cytokine, IL-12 has been shown to induce GZMA and GZMB expression (30, 31). The GZMs are traditionally defined as death inducers in target cells (32). However, some extracellular GZMs could modulate inflammation and cytokine production, which in turn could regulate proinflammatory responses (ie, GZMA (25, 32–34); GZMB (34–39), GZMK (40), GZMM (34, 37–39)). The extracellular GZMA could enhance the production of inflammatory cytokines, yet the precise mechanism is unknown (41, 42). GZMA activity enhances pro-IL-1β conversion to mature active IL-1β (34, 43) and induces IL-6 and TNFα production from murine macrophages (25), human peripheral blood monocytes, purified monocytes, and from Bacille Calmette-Guérin-infected macrophages (27, 44). However, GZMB did not generate this effect with these cytokines. Collectively, serine protease GZMA (ie, extracellular/secreted) predominantly may function as a regulator of proinflammatory responses (41, 42).

A number of studies demonstrated that proinflammatory biomolecules (ie, IL6, IL8, CXC chemokines (45), IFN-γ (46), inducible nitric oxide synthase [iNOS] (47)) could be diminished by neutralizing serine protease activity with inhibitors such as 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride (AEBSF) (45, 46, 48). We recently reported that neutralization of serine protease activity with AESBF, an inhibitor that predominantly inactivates chymotrypsin and trypsin-like serine proteases (49), diminished estrogen-mediated enhanced expression of key Th1 proinflammatory molecules (IFN-γ, IL-12, recombinant IL-12 [rIL-12]-induced STAT4β, STAT1, T-bet and IL-12Rβ2 mRNA expression, iNOS, and nitric oxide) from rIL-12 or Concanavalin A-stimulated splenocytes without altering cell viability (11, 21).

A shift in the Th1 (ie, IFN-γ)/Th2 (ie, IL-4) balance can decrease the prominent expression of one phenotype while enhancing the other (50), thus defining the nature of inflammatory and immune profile. In the present study, we show that in vivo estrogen specifically promotes extracellular GZMA protein expression. Inhibition of serine protease activity with AEBSF decreased estrogen-modulated extracellular GZMA activity, IFN-γ, IL-1β, and IL-1α secretion. Furthermore, this is the first study to show that even in the presence of Th1-inducing IL-12 and in vivo estrogen, serine protease inactivation up-regulated key players of Th2 profile (ie, IL-4, GATA3, c-Maf). Serine protease activity inhibition selectively altered the translocation, nuclear expression, and DNA binding of STAT6A as well as a shorter sized STAT6 (denoted as pSTAT6B), key molecules that can selectively regulate IL-4 signal transduction and Th2 profile. Interestingly, inhibition of serine protease activity did not enhance STAT5 phosphorylation, which is necessary for sustainable Th2 profile.

Although the immunomodulatory role of the estrogen-mediated proinflammatory biomolecules has been implicated in several female-predominant autoimmune diseases (1, 2), whether these proinflammatory processes could be therapeutically modulated is as yet unclear. Thus, this study provides a novel understanding of serine protease activity in estrogen-mediated immune processes, which may provide therapeutic interventions of estrogen-modulated proinflammatory and autoimmune pathogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Animals and estrogen treatment

Wild-type C57BL/6 3- to 4-week-old male mice (Harlan Laboratories) were fed a diet devoid of phytoestrogens (7013 NIH-31 Modified 6%Mouse/Rat Diet; Harlan-Teklad) (6). Mice were orchidectomized and surgically implanted with 17β-estradiol (estrogen; Sigma; 3–5 mg) or empty (placebo control) implants, a well-established model that has been used to explore the role of estrogen in various animal models (10, 20, 21, 51–57). Mice were terminated after 7–8 weeks of estrogen treatment at approximately 12 weeks of age because: 1) mice at this age are considered to be sexually mature adults; and 2) to provide sustained estrogen treatment similar to physiological estrogen levels observed in female mice. Implants were designed to slowly release sustained levels of estrogen (156–200 pg/mL) in serum (21), which is in the range of normal physiological levels (10, 58–60). The Institutional Animal Care Committee at University of Georgia approved all animal related procedures.

Isolation and culture of splenocytes

Splenocytes from estrogen or placebo-treated mice were cultured under sterile conditions (3, 20, 21, 61). Our previous work showed the importance of cell-to-cell interactions via costimulatory molecules and cytokine milieu in estrogen-mediated Th1 proinflammatory profile (7, 61). Therefore, we investigated the effect of inhibition of serine protease activity on an estrogen-mediated immune response of the whole splenocyte population rather than purified cell populations. An equal volume of cells (1.5 mL; 5 × 106 cells/mL) were cultured with equal volumes of media (unstimulated) or recombinant IL-12p70 (rIL-12, 20 ng/mL; R&D Systems) for 3 or 24 hours in complete phenol-red free RPMI 1640 (3, 20, 21, 61). Select cultures were treated with serine protease inhibitor, 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF; 425 μM/well; Sigma) with or without rIL-12 (10, 21, 62).

Detection of extracellular GZMA and GZMB

Presently, no commercially available murine ELISAs to detect GZMA, GZMM, or GZMK levels in sera or supernatant exist. Thus, to determine expression of extracellular secreted GZMs, an aliquot of supernatants from cultured splenocytes was concentrated 30-fold using Amicon Ultra-10 device (Millipore Corp) (63). Concentrated supernatants boiled with sample buffer were electrophoresed (150 μg/well) on 10% Tris-HCl gel (21, 63). Western blotting was used with GZMA (3GA.5), GZMB (C19), GZMM (I14, M45, P15), GZMK (GM6C3), and secondary antibodies (Abs) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Blots were treated with ECL Plus Substrate (Pierce Chemical Co). Bands were determined as mean relative densitometry values with Kodak Image Station 4000R (Carestream).

Na-benzyloxycarbonyl-l-lysine thiobenzyl ester (BLT) esterase activity assay for GZMA

GZMA activity was assessed in supernatants using the BLT esterase activity assay, which cleaves BLT (z-lysSBzl; Sigma) (64). Briefly, 75 μL of sample per well were diluted with 75 μL of 100 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.5. Reaction was initiated by the addition of 25 μL of 20 mM BLT (Sigma) following the 25 μL of 20 mM 5,5′-dithio-bis (2-nitnobenzoic acid) addition (Sigma) and incubated for 1.5 hours for optimal color development at 37°C. Results were read at OD405/490 (BioTek Plate Reader). Plate background (490 nm) was subtracted from BLT-esterase OD readings (405 nm). Values for BLT esterase activity are represented as percent expression of GZMA activity following AEBSF treatment to as normalized to the corresponding unstimulated cells (media), which was considered 100%.

Detection of cytokines and Western blot analysis

Levels of IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-1α, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-33 in cell culture supernatants were measured with ELISA per the manufacturer's instructions (eBiosciences) using BioTek plate reader (7, 10, 21). Protein expressions in nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were determined with Western blotting (7, 10, 21) using Abs: c-Maf (M153) (Santa Cruz), GATA3 (Abcam), phosphorylated STAT6 (pSTAT6; Tyr641), total STAT6 (antibody binds to surrounding residues around 620 amino acids; Cell Signaling Technology), pSTAT5, STAT5, and secondary Abs (Cell Signaling Technology, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Abcam). Purity of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts was confirmed by evaluating LaminB1 expression. Lamin B1 was expressed in nuclear but not in cytoplasmic extracts of the samples, which demonstrated the efficacy of our extraction procedure (data not shown). β-Actin was used as a protein loading control for both nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts because 1) it is expressed in nucleus, cytosol, and whole-cell extracts (7, 10, 11, 17, 65–70); 2) all nuclear and cytoplasmic samples have been processed under the same conditions and normalized with quantitative Bradford assay (data not shown) before loading to the gel, which reflects equivalent β-actin levels in Western blots; and 3) β-actin was used as a standard protein loading control to efficiently observe and compare the differences of target protein expressions between cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments (ie, pSTAT6). Blots were visualized with Kodak Image Station 4000R using ECL Plus Substrate.

EMSA

Nuclear extracts from 3 hours cultures were used for EMSA (Panomics) (6). Briefly, 5 μg of nuclear extracts were incubated with biotin-labeled STAT6 probes and in a thermal cycler at 15°C for 30 minutes. For control, excess unlabeled STAT6 probe DNA was added to confirm binding specificity. No probe added sample was run as an additive control. DNA-protein complexes were blotted on a nylon membrane (Biodyne B; Pall) after separation on 5% nondenaturing Tris-boric acid-EDTA polyacrylamide gel in 0.5% Tris-boric acid-EDTA (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at 4°C. Blots were developed using chemiluminescence (Panomics) and visualized with Kodak Image Station 4000R.

Statistics

Statistical significance between experimental groups was determined with one-way ANOVA using InStat software (GraphPad Software, Inc). Post hoc comparisons between treatment group means were performed with Bonferroni for multiple comparisons.

Results

Estrogen up-regulates extracellular GZMA expression and rIL-12 modulated GZMA activity that is inhibited with AEBSF

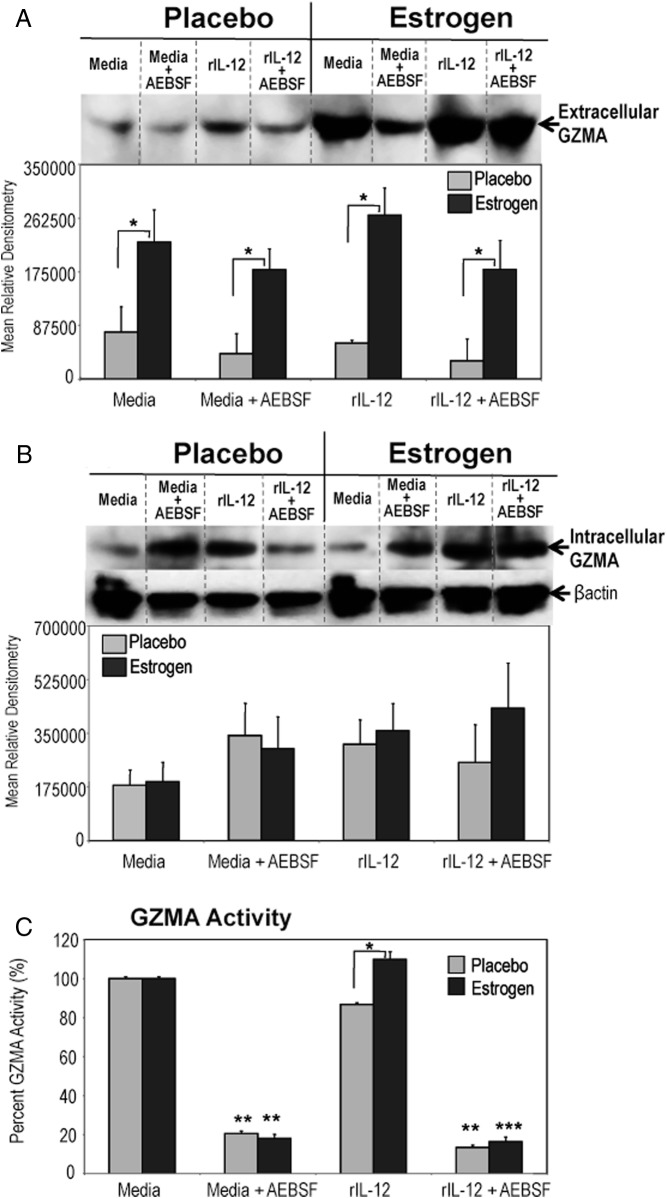

Previously, we demonstrated that inhibition of serine protease activity selectively down-regulated estrogen-mediated rIL-12-inducible STAT4, STAT1, and nuclear factor-κB activation as well as downstream IFN-γ-inducible biomolecules (ie, iNOS) (11, 21). In this study, we investigated whether in vivo estrogen would alter the expression and activity of extracellular serine protease GZMA, which has been shown to possess proinflammatory characteristics (25, 35). We found that estrogen markedly up-regulated the expression of extracellular GZMA protein in supernatants from unstimulated (media) and rIL-12-stimulated splenic lymphocytes compared with decreased levels observed from placebo (control) mice (Figure 1A). Intracellular GZMA expression was similar in splenocytes of estrogen and placebo mice (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of serine protease activity altered estrogen-induced extracellular GZMA activity but not extracellular and intracellular GZMA expression. Splenocytes from estrogen or placebo-treated mice were stimulated with rIL-12 (20 ng/mL) or left unstimulated in media with or without AEBSF (425 μM) for 3 hours. Extracellular GZMA (A) was determined in concentrated supernatants and analyzed with Western blot. Intracellular GZMA (B) and β-actin (protein loading control) expression in cytoplasmic extracts of cultured splenocytes were determined with Western blotting. Top portion of panels depict representative blots (mean ± SEM; panel A, n ≥ 8 mice per treatment; panel B, n ≥ 5 mice per treatment; *, P < .05). Dashed dividing lines delineate groups of specific bands from different sections of the same gel. Panel C demonstrates BLT esterase activity, a specific marker of GZMA activity, which was measured in supernatants of unstimulated (media) or rIL-12-stimulated lymphocytes treated with or without AEBSF from placebo or estrogen-treated mice at 3 hours. Values for BLT esterase activity are represented as percent expression of GZMA activity (±SEM) as paired to unstimulated cells (media), which was considered 100% (means of 9 or 7 experiments ± SEM; *, P < .05).

Next, supernatants were assayed for extracellular GZMA activity with BLT esterase assay, a well-established functional marker for detection of GZMA tryptase activity (71–74). Extracellular GZMA activity was significantly increased in supernatants from rIL-12-stimulated lymphocytes of estrogen-treated mice compared with placebo-treated mice (Figure 1C). Estrogen-mediated rIL-12-induced GZMA activity was higher than basal GZMA activity detected in unstimulated (media) supernatants (Figure 1C). The AEBSF treatment was associated with substantial reduction in extracellular GZMA activity in supernatants from unstimulated and rIL-12-stimulated splenocytes (Figure 1C). Extracellular or intracellular GZMB levels in relation to stimulant, AEBSF treatment, or placebo vs estrogen exposure were not markedly altered (data not shown). We also investigated whether in vivo estrogen would enhance the expression of other proinflammatory GZMs, GZMK (40) or GZMM (37). There were no detectable GZMM or GZMK protein expressions either in the supernatants or cytoplasmic extracts. Together, these results suggest that estrogen selectively up-regulates extracellular GZMA expression and activity, which was modulated by inactivation of serine protease activity.

Inhibition of serine protease activity diminishes estrogen-inducible proinflammatory IFN-γ, IL-1α, and IL-1β production

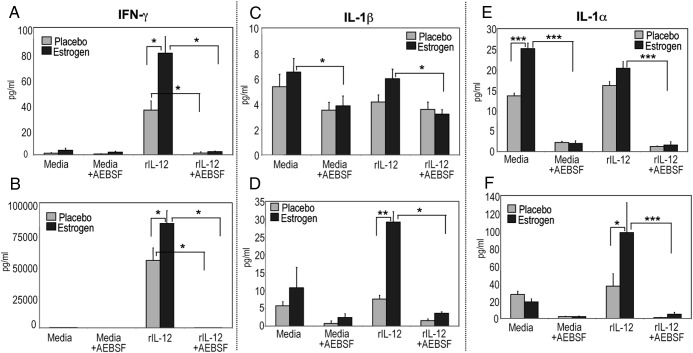

We showed that IFN-γ secretion by splenocytes upon in vivo estrogen exposure was markedly higher than that of rIL-12-stimulated splenocytes from placebo-treated mice at 3 hours (Figure 2A) as well as at 24 hours of culture (Figure 2B), demonstrating a strong Th1 bias (6, 10, 21). In this study, inactivation of serine protease activity with AEBSF significantly reduced estrogen-mediated levels of rIL-12-induced IFN-γ production after 3 hours (Figure 2A) and 24 hours (Figure 2B). Inhibition of serine protease activity with AEBSF resulted in approximately 93% and 81% marked reduction of IFN-γ production after 3 hours of culture from splenocytes from placebo and estrogen-treated mice, respectively. The IFN-γ secretion was drastically reduced (∼99%) upon inactivation of serine protease activity with AEBSF after 24 hours of culture from rIL-12-stimulated splenocytes from both mice.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of serine protease activity down-regulates estrogen-modulated IFN-γ, IL-1β, and IL-1α production. IFN-γ levels in supernatants from unstimulated (media) or rIL-12-stimulated splenocytes from estrogen and placebo-treated mice cultured for 3 (A) and 24 hours (B) were measured with ELISA (means ± SEM; panel A, n ≥ 11 mice per treatment; panel C, n ≥ 5 mice per treatment). Supernatants from estrogen and placebo-treated rIL-12-induced splenocytes cultured with or without AEBSF were evaluated for IL-1 production via ELISA (A–D). Panels C and D show IL-1β production in picograms per mL (±SEM) at 3 and 24 hours, respectively. Level of IL-1α secretion at 3 (E) and 24 hours (F) culture was depicted as picograms per mL (±SEM). Panels C and D, n ≥ 6 mice per treatment; panels E and F, n ≥ 5 mice per treatment; *, **, and *** denote P < .05, P < .01, and P < .001, respectively).

Recent studies demonstrated the role of GZMA in the induction of mature IL-1β secretion, a proinflammatory cytokine produced during inflammation and autoimmunity (25, 34, 35, 75). Therefore, we next determined whether estrogen as well as inhibition of serine protease activity alters IL-1β production from unstimulated or rIL-12-stimulated splenocytes. Estrogen increased IL-1β production from unstimulated and rIL-12-treated cells at 3 hours (Figure 2C) and even more with rIL-12 stimulation at 24 hours than that observed from placebo controls (Figure 2D). Following AEBSF treatment, IL-1β secretion was decreased in supernatants of unstimulated and rIL-12-treated cells cultured for 3 or 24 hours (Figure 2, C and D). Next, we investigated IL-1α production, another GZM-mediated cytokine (25, 34, 35). Although GZMB expression was not drastically altered upon estrogen or AEBSF treatment, IL-1α production was up-regulated from rIL-12-stimulated cells of estrogen-treated mice at 3 hours and 24 hours, but not placebo-treated mice. Inhibition of serine protease activity with AEBSF decreased IL-1α levels at 3 and 24 hours (Figure 2, E and F).

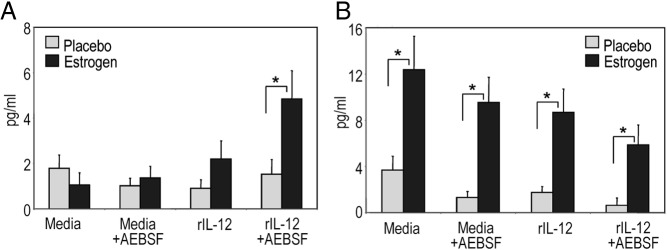

IL-4 secretion is up-regulated at 3 hours but not at 24 hours with AEBSF from rIL-12-stimulated lymphocytes of estrogen-treated mice

Inhibition of serine protease activity down-regulated estrogen-mediated and rIL-12-induced proinflammatory profile (11, 21)(GZMA activity, Figure 1; IFN-γ and IL-1 family, Figure 2). Therefore, we next assessed whether decreased proinflammatory Th1 profile with AEBSF promoted a shift toward Th2 profile as characterized with IL-4, IL-5, and IL-33 production (76, 77). We found that inactivation of serine protease activity with AEBSF enhanced IL-4 production even in the presence of rIL-12 stimulation of lymphocytes at 3 hours from estrogen, but not placebo-treated mice (Figure 3A). Although IL-4 levels were higher in supernatants from estrogen-treated mice compared with placebo controls at 24 hours of culture, the IL-4 production was not noticeably altered upon stimulation with rIL-12 and AEBSF (Figure 3B). The IL-5 and IL-33 levels were not detectable in the supernatants at 3 and 24 hours of culture (data not shown). The suppressive effect of noncytotoxic serine protease inhibitor AEBSF was not due to cell death. AEBSF did not induce apoptosis at 3 or 24 hours (data not shown) (21, 78, 79).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of serine protease activity via AEBSF transiently induced IL-4 production at 3 hours from rIL-12-cultured cells from estrogen-treated mice. Supernatants after 3 (panel A, n = 8) or 24 hours (panel B, n = 3) of cell cultures with rIL-12 or media with or without AEBSF were analyzed for IL-4 production with ELISA (means pg/mL ± SEM; *, P < .05).

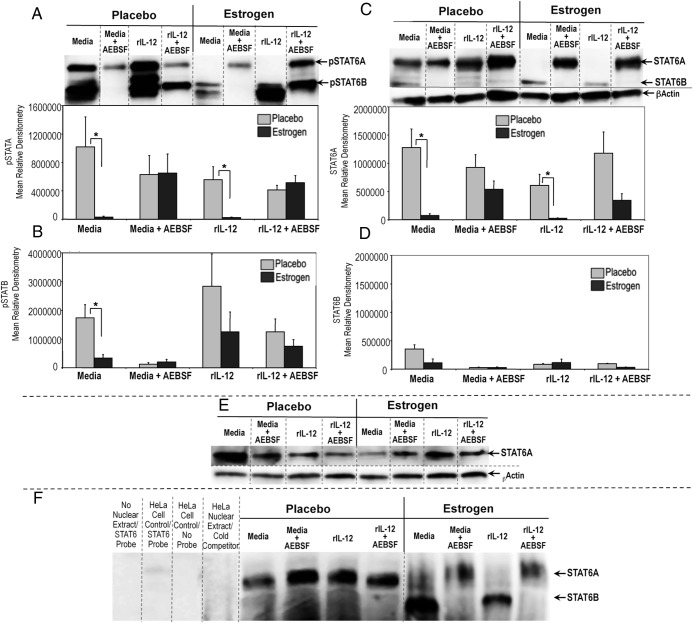

Inhibition of serine protease activity selectively alters nuclear pSTAT6A expression, translocation, and DNA binding

STAT6 has a critical role in Th2 development, IL-4-modulated responses, and regulation of GATA3 and c-Maf expression, key transcription factors in Th2 differentiation (80). STAT isoforms α and β (ie, STAT1, STAT3, STAT4, STAT6) have been reported to have different molecular functions and could be differentially modulated in response to stimulus or cytokines (81–83). Given the key role of activated STAT6 nuclear translocation (phosphorylated STAT6, pSTAT6) and STAT6 isoforms binding to target DNA elements in mediating Th2 differentiation (84, 85), we next investigated whether inhibition of serine protease activity up-regulates nuclear accumulation and activation of STAT6 isomers, STAT6A (110–95 kDa) and STAT6B (85–75 kDa) (85). Unlike the robust nuclear pSTAT6A (Figure 4A) and total STAT6A (Figure 4C) expression in lymphocytes from placebo controls, there was no detectable nuclear pSTAT6A (Figure 4A) or total STAT6A (Figure 4C) in unstimulated or rIL-12-cultured lymphocytes of estrogen-treated mice. Inhibiting serine protease activity selectively increased nuclear pSTAT6A and total STAT6A compared with non-AEBSF-treated lymphocytes from estrogen-treated mice (Figure 4, A and C). Nuclear activation of shorter STAT6 isoform, pSTAT6B was decreased in lymphocytes from estrogen-treated mice compared with placebo controls as shown by densitometric analysis (Figure 4B). The pSTAT6B level was diminished in media and decreased in rIL-12-treated as well as AEBSF treated cells from both placebo and estrogen-exposed mice. Truncated STAT6 isoforms were frequently observed around pSTAT6B, which was decreased with AEBSF (Figure 4B). However, we did not observe a marked change in nuclear total STAT6B expression, although the STAT6 antibody binds around the same region of pSTAT6 Ab (Tyr641) binding (Figure 4, C and D). We conducted alignment analysis of mouse STAT6A (Swiss-Prot accession no. P52633) with human STAT6A (Swiss-Prot accession no. P42226) and STAT6B (Swiss-Prot accession no. Q56TK0) (86) protein sequences to evaluate whether polyclonal STAT6 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 9362) has a differential affinity for these isoforms. The STAT6 antibody used (Figure 4; Cell Signaling Technology, catalog no. 9362) to evaluate total unphosphorylated STAT6 protein detects STAT6 protein by recognizing the peptide sequence around amino acid 620 of human STAT6. Our alignment analysis has demonstrated that mouse STAT6A and human STAT6A protein sequences have corresponding homologous residues surrounding amino acid 620, which would allow successful detection of STAT6 with the polyclonal antibody (data not shown). On the other hand, there was weak homology between human STAT6A and STAT6B residues surrounding amino acid 620, where STAT6 antibody could bind. Currently, murine STAT6B (∼85–75 kDa) protein sequence is not available for alignment analysis. Overall, weak STAT6B bands in Figure 4, C and D, could be due to alteration in peptide residues and decreased binding of STAT6 antibody to target sequence. On the other hand, 641 tyrosine unit (641Y) was strongly conserved in all STAT6 forms (human STAT6A, STAT6B, mouse STAT6); thus the phosphorylated STAT6 antibody could specifically detect both bands of pSTAT6.

Figure 4.

Selective enhancement of nuclear pSTAT6A, total STAT6A, and STAT6A DNA binding activity in splenocytes from estrogen-treated mice was dependent on serine protease inactivation. Nuclear extracts (25μg) from splenocytes cultured in media or rIL-12 with or without AEBSF for 3 hours were subjected to Western blot and depicted as mean relative densitometry for pSTAT6A (A), pSTAT6B (B), STAT6A (C), and STAT6B (D). Top portions of panels A and B show representative blots for pSTAT6A/B and STAT6A/B, respectively. Panel E shows representative blot for cytoplasmic STAT6/B expression as detected using 25 μg cytoplasmic extracts of splenocytes from estrogen or placebo-treated mice. β-Actin was used as a protein loading control (n = 6; mean ± SEM; *, P < .05). Dashed dividing lines delineate groups of specific bands from different sections of the same gel. Panel F, EMSAs were performed using 5 μg of nuclear extracts from splenocytes from estrogen- or placebo-exposed mice cultured with media or rIL-12 in the presence or absence of AEBSF for 3 hours. For the controls, samples without nuclear extract with only STAT6-labeled probe, HeLa control nuclear extract with STAT6-labeled probe, with no probe and unlabeled cold STAT6 probe (cold competition) instead of labeled STAT6 probe were used. Dashed dividing lines indicate the grouping of sections of gel run at the same time under the same conditions. Data shown represent at least 4 independent experiments.

We next examined whether estrogen modulates the specific nuclear translocation of STAT6A. Western blot analysis revealed that cytoplasmic total STAT6A expression (Figure 4E) was increased in samples from estrogen-treated mice compared with nuclear extracts (Figure 4C). Cytoplasmic STAT6A expression was not different in samples from placebo or estrogen-treated mice. We next determined whether estrogen and AEBSF-mediated differential expression of STAT6 isoforms would possess DNA binding activity. As shown in Figure 4F, STAT6A had decreased DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts of unstimulated (media) and rIL-12-cultured lymphocytes of estrogen-treated mice compared with placebos. The DNA-binding activity of the shorter isoform of STAT6A (denoted as STAT6B) was detected only in splenocytes from estrogen-exposed mice. AEBSF treatment of splenocytes from estrogen-exposed mice enhanced STAT6A, yet diminished STAT6B DNA-binding activity. However, AEBSF did not alter the nuclear STAT6A DNA-binding activity from media or rIL-12-cultured lymphocytes of placebo mice. These data suggest that inhibition of serine proteases regulates estrogen-modulated selective nuclear translocation, activation, proteolytic generation, and DNA binding of STAT6 isoforms.

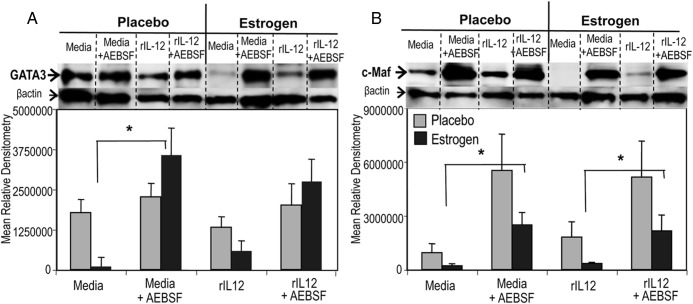

Nuclear GATA3 and c-Maf were markedly up-regulated in AEBSF-treated lymphocytes of in vivo estrogen-exposed mice

To determine whether neutralization of serine protease activity alters other key Th2 transcription biomolecules in addition to IL-4 and STAT6, we extended the analysis to determine nuclear GATA3 and c-Maf expression in unstimulated or rIL-12-cultured lymphocytes treated with or without AESBF (87, 88). Although in vivo estrogen exposure diminished nuclear GATA3 and c-Maf in unstimulated and Th1-polarizing rIL-12-cultured splenocytes compared with placebo controls (Figure 5, A and B), the AEBSF markedly enhanced nuclear GATA3 as well as c-Maf protein expression in splenocytes from estrogen-treated mice (Figure 5, A and B). Although AEBSF treatment enhanced expression of Th2 biomolecules above, AEBSF did not alter the expression of phosphorylated p38 MAPK (p-p38; Tyr182) and p38 MAPK, which have been shown to modulate Th2 cytokines (ie, IL-4) and GATA3 expression (data not shown) (89).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of serine proteases reverses estrogen-mediated nuclear accumulation of GATA3 and c-Maf. Nuclear extracts (25 μg/sample) from media or rIL-12-treated splenocytes cultured with or without AEBSF for 3 hours were analyzed for GATA3 (A) and c-Maf (B) with Western blot analysis. Representative blots and mean relative densitometry data of GATA3 (A) and c-Maf (B) are presented. Results in panel A (GATA3) are a representative of least 7 independent experiments, and data from panel B (c-Maf) are representative of at least 5 independent experiments (mean± SEM; * and ** denote P < .05 and P < .01). Dashed dividing lines delineate groups of bands from different sections of the same gel.

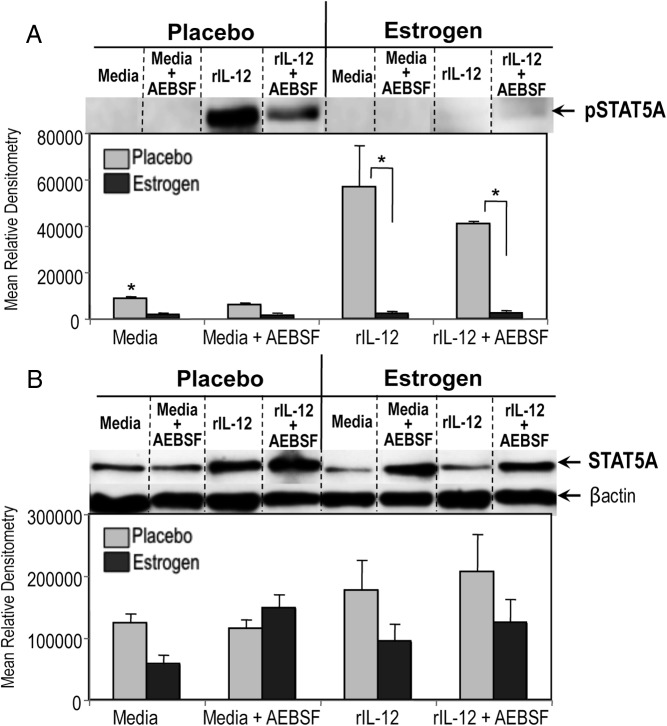

In vivo estrogen abrogates activation of nuclear STAT5

The STAT5 can maintain GATA3 expression and cooperate with GATA3 to promote sustained Th2 cytokine production (87). Thus, we analyzed whether neutralization of serine protease activity can influence the Th2 differentiation via tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5 in unstimulated and rIL-12-cultured splenocytes from estrogen and placebo-treated mice. Nuclear pSTAT5A was not detectable from media or rIL-12-cultured splenocytes from estrogen-treated mice, and interestingly inhibition of serine protease activity with AEBSF did not enhance pSTAT5A expression (Figure 6A). The AEBSF did not alter nuclear pSTAT5 from rIL-12-cultured cells from placebo controls (Figure 6A). The STAT5A expression was lower in splenocytes from estrogen-treated mice compared with placebos (Figure 6B). As such, despite the effect of serine protease inhibition on up-regulation of Th2 biomolecules at 3 hours, the marked reduction of nuclear pSTAT5A via in vivo estrogen exposure was not reversed by AEBSF.

Figure 6.

AEBSF treatment does not alter estrogen-mediated hindrance of nuclear pSTAT5. Nuclear expression phosphorylated STAT5A (pSTAT5A) and total STAT5 from media or rIL-12-activated splenocytes with or without AEBSF for 3 hours were detected with Western blot analysis. β-Actin served as protein loading control. Dashed dividing lines indicate the grouping of sections of the different gel run at the same time under the same conditions from cell cultures. Representative blot pictures and mean relative densitometry data (± SEM) from at least 3 experiments are shown (*, P < .05).

Discussion

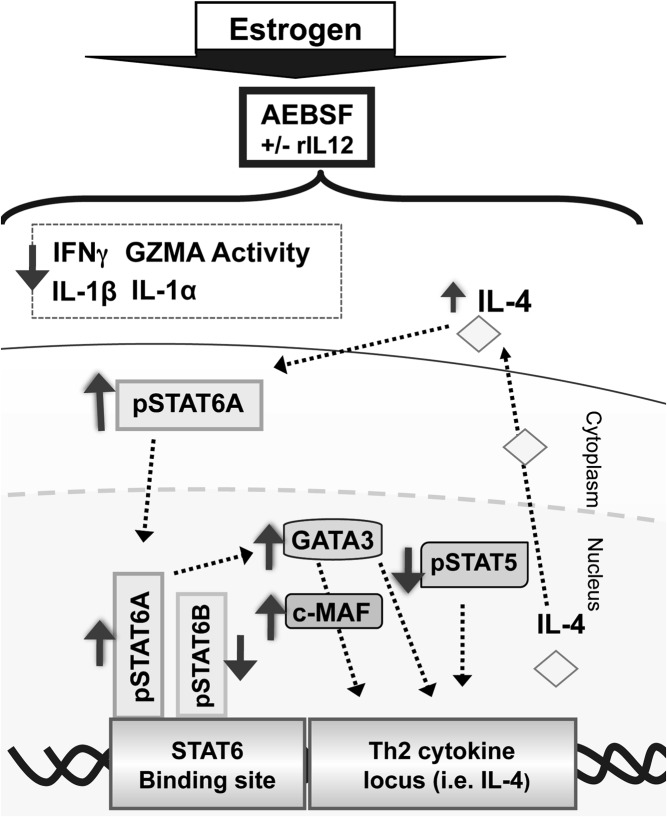

As we have previously reported, an enhanced estrogen-mediated IL-12-induced Th1 profile and associated proinflammatory biomolecules are selectively down-regulated in the presence of an inhibitor of serine protease activity (ie, AEBSF) (11, 21). However, the immunomodulatory role of estrogen on GZMs, related proinflammatory cytokines, as well as the influence of serine protease activity on Th1/Th2 responses is not known. Still, the potential of extracellular serine proteases (ie, GZMA) to influence several immune mechanisms and proinflammatory cytokines has been supported in the literature (24–28, 37, 39, 40). We propose that inhibition of serine protease activity plays a pivotal role in mediating an estrogen-modulated proinflammatory Th1-like signature by: 1) down-regulating IL-12-induced IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-1α production, and GZMA activity; and 2) enhancing the nuclear expression of key Th2 transcription factors GATA3, c-Maf, pSTAT6A, total STAT6, and IL-4 production. AEBSF did not alter p38 MAPK activity or reverse the nuclear absence of pSTAT5A in splenocytes from estrogen-treated mice, which may further promote a Th2-type profile (Figure 7) (87, 88). Although estrogen-mediated Th1-related biomolecules were diminished, this was not due to decreased cell viability (data not shown) (11, 21). To our knowledge, our work is the first to show that neutralization of serine protease activity mediated a shift toward a Th2-like profile from a predominant estrogen-mediated proinflammatory Th1 signature even in the presence of Th1-inducing IL-12.

Figure 7.

A proposed schematic representation showing how inhibition of serine protease activity in the presence of estrogen and/or IL-12 can still shift a Th1 signature toward Th2. Estrogen-enhanced Th1 profile (ie, IFN-γ, extracellular GZMA activity, IL-1β, and IL-1α) was diminished following AEBSF treatment. Serine protease inactivation selectively enhanced pSTAT6A and STAT6A DNA binding whereas nuclear pSTAT6B was down-regulated. Up-regulation of pSTAT6A activation could lead to increased GATA3 and c-Maf. Interestingly, estrogen diminished nuclear pSTAT5A expression, which was not reversed by AEBSF. Although enhanced pSTAT6, c-Maf, and GATA3 levels could increase IL-4, which could in turn further activate STAT6, the absence of pSTAT5A could fail to further up-regulate a dominant and stable Th2 profile.

IL-12 has been shown to increase GZMA mRNA expression (90, 91). Further, IL-12 administration in chimpanzees in vivo increased extracellular GZMA in their sera (92). Deliberate GZMA deletion in mice infected with helminth (Litomosoides sigmodontis) decreased STAT4 gene expression and inflammation compared with wild-type infected B6 mice (93). Interestingly, GZMA expression was not altered in natural killer (NK) or non-NK cells in STAT1-deficient mice (94). These collective reports suggest that the IL-12/STAT4 pathway and GZMA play a vital role in modulation of Th1 signature.

Although data are limited, hormonal modulation of GZMA has been suggested (22, 95, 96). For instance, stimulated T cells from women at reproductive age had higher gzmA gene and mRNA expression than men (22). We found that in vivo estrogen up-regulates extracellular GZMA expression. Extracellular GZMA can be found as inactive zymogen, free mature active proteinase, mature GZMA complexed to proteoglycans, or active GZMA-inactivated through the binding of plasma protease inhibitors to the enzyme (97). Proteolytic activity of serine proteases (ie, GZMs) released from cells depends on the balance between proinflammatory and antiinflammatory stimuli such as IL-12. Healthy individuals could express low levels of extracellular GZMA protein, whereas high levels of extracellular GZMA and activity were determined in response to inflammatory stimuli from Dengue fever or cytomegalovirus infection in transplant patients (97). Our studies showed increased relative amounts of extracellular GZMA protein from estrogen-treated samples when compared with controls. However, rIL-12 stimulation up-regulated free GZMA activity only in the supernatants of cells from estrogen-treated mice. Therefore, it is possible that estrogen could increase the overall extracellular mature GZMA protein, whereas cell stimulation with a Th1-inducing rIL-12 could lead to enhanced extracellular GZMA enzymatic activity. Interestingly, intracellular GZMA expression was comparable between samples from placebo and estrogen-treated mice. Although intracellular GZMA levels were not statistically different between placebo vs estrogen exposure, there was a trend for a numerical increase in intracellular GZMA with AESBF in unstimulated cells (media) compared with media only from placebo or estrogen-treated mice. AEBSF did not produce a similar trend with rIL-12 stimulation. Thus, it is plausible that the suppressive effect of AEBSF on unstimulated cells could decrease the secretion of GZMA in the extracellular environment in the absence of rIL-12 stimulation. In addition, these findings suggest that estrogen has a modulatory role on GZMA release. One additional point, AEBSF has been reported to inhibit serine proteases by causing a conformational change in catalytic residues as well as reacting with the active serine site of the enzyme (98). In the present study, we observed that AEBSF specifically down-regulated the enzymatic activity of the GZMA without altering the extracellular GZMA protein levels.

The precise mechanism of immune trafficking of proinflammatory molecules (ie, GZMs) is yet unclear and warrants further investigation. Because estrogen receptors have been identified in the plasma membrane of various cell types including lymphocytes (99), it is possible that estrogen receptor signaling could modulate granule exocytosis and GZM secretion as in the case of T cell receptor-driven degranulation. For example, estrogen receptor activation increases intracellular calcium (100) and protein kinase Cα activity (101), both of which have been previously found to be able to trigger granule exocytosis in CD8+T cells (102).

In this study, IL-12 stimulation of estrogen-treated murine splenocytes enhanced extracellular GZMA activity. Due to its homodimeric structure, GZMA is unique compared with other GZMs in substrate selection and enzymatic activity (103). Treatment with AEBSF, a predominant inhibitor of tryptase activity (ie, GZMA) (49), diminished IL-12-induced GZMA activity without altering GZMA protein levels in estrogen-treated mice. This is possibly due to an inactivation of the active protease site on the enzyme GZMA (104, 105). Further, previous studies reported basal level GZMA activity in unstimulated murine splenic NK cells or T cells (71, 106). Glucocorticoids (ie, dexamethasone) or 3,4-dichloroisocoumarin (a serine protease inhibitor) can reduce basal GZMA activity in unstimulated PC30 or 697 leukemia cell line (73, 107). In accordance with these studies, we observed that AEBSF decreased basal (media) GZMA activity in the supernatants of murine splenic lymphocytes.

GZMA with tryptase specificity cleaves after arginine or lysine residues, which is measured with the BLT esterase assay (25, 64, 108). Of all GZMs, GZMA and K are the only tryptases. Shrestra et al (109) have demonstrated GZMA obtained from cytotoxic lymphocytes of wild-type mice had BLT esterase activity. The BLT activity was reduced more than 80% in cell lysates from GZMA-knockout mice Although a low residual BLT activity was detected in cells from GZMA-knockout mice, the authors suggested that the minimal level of BLT activity detected could be due to other GZMs, such as GZMK (109). Although GZMK has tryptase activity, GZMK is approximately 10 times less abundant than GZMA in cells (110–112). In our studies, secreted extracellular GZMA activity was increased in the supernatants of rIL-12-cultured cells measured with the BLT assay. There was no detectable extracellular or intracellular GZMK from cells of placebo- or estrogen-treated mice. Thus, these data infer that the increased BLT esterase activity could be predominantly due to extracellular GZMA activity.

Proteolysis of inactive IL-1β and IL-1α by GZMA and GZMB to active proinflammatory cytokines has been recently demonstrated (25, 34, 35). The IL-12 has been shown to increase IL-1β production (113), which can further up-regulate IL-12 secretion (114) and thus induce IFN-γ and the Th1 profile (115). This feedback mechanism can also enhance GZMA expression and activity. The mechanisms by which GZMs promote the release of inflammatory mediators are not fully understood, although it seems that cysteine protease Caspase 1 activity may participate to some extent in that process (25). Because it was suggested that possible endotoxin contamination of recombinant GZMA might have caused the altered GZMA-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production, even though the authors clarified that was not the issue (26, 116), charcoal-stripped FCS with endotoxin level lower than 1.3 EU/μg/lot was used in phenol-red free media in all the present studies to avoid FCS-derived hormonal or endotoxin effect on the cells. We found that estrogen-modulated IL-1β and IL-1α and the lower levels of IL-1 from placebo samples were significantly reduced with AEBSF at early (3 hours) or late (24 hours) culture. These data therefore suggest that the inhibition of serine protease activity noticeably modulates estrogen-mediated IL-1β and IL-1α production possibly through inactivation of GZMA activity. Because estrogen did not increase extracellular GZMB levels, the altered IL-1α production could instead be due to changes in GZMA activity. Indeed, it has been shown that serum from GZMA-deficient mice undergoing bacterial sepsis contains reduced levels of both IL-1β and IL-1α compared with wild-type control animals (J. Pardo; manuscript in preparation). Whether estrogen and serine protease inhibition alters GZMA expression, activity, and associated inflammatory biomolecules within select cell subsets from wild-type or related knockout mice are currently not known, and we will investigate the direct role of estrogen and GZMA using GZMA-knockout mice in our future studies. In conclusion, our data show that estrogen, a mediator of proinflammatory IFN-γ, also increases extracellular GZMA expression and activity, which together have the propensity to modulate the IL-1 family.

The paradigm of Th1/Th2 balance coordinating the immune homeostasis has been the cornerstone for understanding key immune responses and autoimmunity (50). IL-4, a major Th2-type cytokine, combined with Th2 transcription factors, can down-regulate IL-12/STAT4 signaling shifting a Th1 profile toward Th2 (9, 50). Present data show that neutralization of serine protease activity enhanced immediate early IL-4 secretion at 3 hours even in the presence of Th1-inducing rIL-12 and in vivo estrogen exposure. However, further elevation in IL-4 level was not sustained at 24 hours.

The shorter STAT6 isoform truncated by a nuclear serine protease has been shown to posses a negative effect on STAT6 signaling, which could alter Th2 differentiation (83). Interestingly, in vivo estrogen exposure and rIL-12 treatment up-regulated nuclear pSTAT6B, which might hinder Th2 signaling biomolecules (ie, GATA3) in the presence of a strong Th1 bias. Inhibition of serine protease activity enhanced nuclear expression of pSTAT6A and STAT6A as well as selective cytoplasmic-to-nuclear translocation of STAT6A in samples following in vivo estrogen exposure. Previous studies have shown that STAT6A isoform has more enhanced transcriptional induction than STAT6B, which could provide differential responsiveness to IL-4 and regulation of Th2 differentiation (117, 118). Therefore, it is possible that AEBSF-enhanced pSTAT4A expression and STAT6A-DNA binding in samples from estrogen-treated mice could exert a positive regulatory activity by modulating IL-4 production in concert with a diminished Th1 profile.

GATA3 and GATA3-inducible c-Maf promote Th2 differentiation by inhibiting Th1-type transcription factors (ie, STAT4, T-bet) and inducing Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5). The immediate expression of these transcription factors could lead to an initial burst in low IL-4 levels. However, for sustained and stabilized IL-4 production and Th2 commitment, sustained activation of STAT5 is crucial in combination with the initial burst of GATA3 (87, 88). In the absence of STAT5 activation, the cells are unable to enhance IL-4 production ability and thus, generate a stable Th2 profile (119). In this study, in vivo estrogen markedly diminished GATA3, GATA3-inducible c-Maf, and activated STAT5A (pSTAT5A) expression. Treatment with AEBSF enhanced GATA3 and c-Maf expression, but not pSTAT5A, in samples from estrogen-exposed mice. However, pSTAT5A expression was detected in IL-12-cultured placebo-treated splenocytes. IL-12 can activate STAT5 phosphorylation (120, 121). Conversely, STAT5A can down-regulate IL-12-induced Th1 differentiation by up-regulating suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 expression, which can inhibit IL-12/STAT4 signaling (122). Thus, it would appear that serine protease inhibition could promote an immediate early skew from a predominant estrogen-modulated Th1-type toward a Th2-type phenotype at 3 hours yet not apparent at 24 hours, which will be explored in future studies (4, 21). Overall, it is plausible that the inhibition of estrogen-modulated Th1 (ie, IFN-γ, T-bet, STAT4) signature and GZMA activity by neutralization of serine protease activity could provide the initial signal for STAT6A, GATA3, and c-Maf to induce Th2 signaling and contribute to the rapid and transient expression of IL-4 at 3 hours observed from rIL-12 stimulated estrogen-treated cells. However, the lack of STAT5 activation could diminish the full accessibility of the IL-4 gene and the complete promotion of Th2 profile of the AEBSF-treated cells (87, 88). Collectively, these data emphasize the complexity of Th1/Th2 regulation with serine protease inactivation in an estrogen-mediated environment.

Although the precise pathways remain to be fully elucidated, our results suggest that serine protease inactivation is an important component in regulating the Th2 profile, even in the presence of estrogen and IL-12. Thus, controlling the inhibition of the serine protease-modulated pathways may offer novel therapeutic approaches for management of estrogen-related inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank the animal care staff of University of Georgia and Ms. Mandana Nisanian for the assistance in animal work.

This work was supported by start-up funding by the University of Georgia Research Foundation and in part by National Institutes of Health grant NIH R21-PAR-03–12 (to R.M.G, Jr.). J.P. was supported by grant SAF2011–25390 from Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, Aragón I+D (ARAID), and Fondo Social Europeo (FSE).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- Abs

- antibodies

- AEBSF

- BLT, Na-benzyloxycarbonyl-l-lysine thiobenzyl ester

- GZM

- Granzyme

- IFN

- interferon

- iNOS

- inducible nitric oxide synthase

- NK

- natural killer

- pSTAT

- phosphorylated STAT

- rIL

- recombinant IL

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription.

References

- 1. 1.Rider V, Abdou NI. Gender differences in autoimmunity: molecular basis for estrogen effects in systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1009–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cutolo M, Sulli A, Capellino S, et al. Sex hormones influence on the immune system: basic and clinical aspects in autoimmunity. Lupus. 2004;13:635–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karpuzoglu-Sahin E, Zhi-Jun Y, Lengi A, Sriranganathan N, Ansar Ahmed S. Effects of long-term estrogen treatment on IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-4 gene expression and protein synthesis in spleen and thymus of normal C57BL/6 mice. Cytokine. 2001;14:208–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maret A, Coudert JD, Garidou L, et al. Estradiol enhances primary antigen-specific CD4 T cell responses and Th1 development in vivo. Essential role of estrogen receptor α expression in hematopoietic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:512–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karpuzoglu E, Zouali M. The multi-faceted influences of estrogen on lymphocytes: toward novel immuno-interventions strategies for autoimmunity management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2011;40:16–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karpuzoglu E, Fenaux JB, Phillips RA, et al. Estrogen up-regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase, nitric oxide, and cyclooxygenase-2 in splenocytes activated with T cell stimulants: role of interferon-γ. Endocrinology. 2006;147:662–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karpuzoglu E, Phillips RA, Gogal RM, Jr., Ansar Ahmed S. IFN-γ-inducing transcription factor, T-bet is upregulated by estrogen in murine splenocytes: role of IL-27 but not IL-12. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:1808–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lawless VA, Zhang S, Ozes ON, et al. Stat4 regulates multiple components of IFN-γ-inducing signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2000;165:6803–6808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Szabo SJ, Dighe AS, Gubler U, Murphy KM. Regulation of the interleukin (IL)-12R β 2 subunit expression in developing T helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:817–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karpuzoglu E, Phillips RA, Dai R, Graniello C, Gogal RM, Jr., Ahmed SA. Signal transducer and activation of transcription (STAT) 4β, a shorter isoform of interleukin-12-induced STAT4, is preferentially activated by estrogen. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1310–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dai R, Phillips RA, Karpuzoglu E, Khan D, Ahmed SA. Estrogen regulates transcription factors STAT-1 and NF-κB to promote inducible nitric oxide synthase and inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2009;183:6998–7005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilcoxen SC, Kirkman E, Dowdell KC, Stohlman SA. Gender-dependent IL-12 secretion by APC is regulated by IL-10. J Immunol. 2000;164:6237–6243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Szabo SJ, Sullivan BM, Stemmann C, Satoskar AR, Sleckman BP, Glimcher LH. Distinct effects of T-bet in TH1 lineage commitment and IFN-γ production in CD4 and CD8 T cells. Science. 2002;295:338–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Afkarian M, Sedy JR, Yang J, et al. T-bet is a STAT1-induced regulator of IL-12R expression in naïve CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:549–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawana K, Kawana Y, Schust DJ. Female steroid hormones use signal transducers and activators of transcription protein-mediated pathways to modulate the expression of T-bet in epithelial cells: a mechanism for local immune regulation in the human reproductive tract. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2047–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lengi AJ, Phillips RA, Karpuzoglu E, Ahmed SA. 17β-Estradiol downregulates interferon regulatory factor-1 in murine splenocytes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;37:421–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grasso G, Muscettola M. The influence of β-estradiol and progesterone on interferon γ production in vitro. Int J Neurosci. 1990;51:315–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bao M, Yang Y, Jun HS, Yoon JW. Molecular mechanisms for gender differences in susceptibility to T cell-mediated autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:5369–5375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karpuzoglu-Sahin E, Hissong BD, Ansar Ahmed S. Interferon-γ levels are upregulated by 17-β-estradiol and diethylstilbestrol. J Reprod Immunol. 2001;52:113–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Karpuzoglu E, Gogal RM, Jr., Ansar Ahmed S. Serine protease inhibitor, 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzene sulfonyl fluoride, impairs IL-12-induced activation of pSTAT4β, NFκB, and select pro-inflammatory mediators from estrogen-treated mice. Immunobiology. 2011;216:1264–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hewagama A, Patel D, Yarlagadda S, Strickland FM, Richardson BC. Stronger inflammatory/cytotoxic T-cell response in women identified by microarray analysis. Genes Immun. 2009;10:509–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Granville DJ. Granzymes in disease: bench to bedside. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:565–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Froelich CJ, Pardo J, Simon MM. Granule-associated serine proteases: granzymes might not just be killer proteases. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Metkar SS, Menaa C, Pardo J, et al. Human and mouse granzyme A induce a proinflammatory cytokine response. Immunity. 2008;29:720–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pardo J, Simon MM, Froelich CJ. Granzyme A is a proinflammatory protease. Blood 2009;114:3968; author reply 3969–3970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sower LE, Froelich CJ, Allegretto N, Rose PM, Hanna WD, Klimpel GR. Extracellular activities of human granzyme A. Monocyte activation by granzyme A versus α-thrombin. J Immunol. 1996;156:2585–2590 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Puente XS, Sánchez LM, Overall CM, López-Otin C. Human and mouse proteases: a comparative genomic approach. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:544–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bots M, Medema JP. Granzymes at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:5011–5014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salcedo TW, Azzoni L, Wolf SF, Perussia B. Modulation of perforin and granzyme messenger RNA expression in human natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:2511–2520 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chowdhury FZ, Ramos HJ, Davis LS, Forman J, Farrar JD. IL-12 selectively programs effector pathways that are stably expressed in human CD8+ effector memory T cells in vivo. Blood. 2011;118:3890–3900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pardo J, Aguilo JI, Anel A, et al. The biology of cytotoxic cell granule exocytosis pathway: granzymes have evolved to induce cell death and inflammation. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:452–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lieberman J. Granzyme A activates another way to die. Immunol Rev. 2010;235:93–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Irmler M, Hertig S, MacDonald HR, et al. Granzyme A is an interleukin 1 β-converting enzyme. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1917–1922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Afonina IS, Tynan GA, Logue SE, et al. Granzyme B-dependent proteolysis acts as a switch to enhance the proinflammatory activity of IL-1α. Mol Cell. 2011;44:265–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andrade F. Non-cytotoxic antiviral activities of granzymes in the context of the immune antiviral state. Immunol Rev. 2010;235:128–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anthony DA, Andrews DM, Chow M, et al. A role for granzyme M in TLR4-driven inflammation and endotoxicosis. J Immunol. 2010;185:1794–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Koning PJ, Tesselaar K, Bovenschen N, et al. The cytotoxic protease granzyme M is expressed by lymphocytes of both the innate and adaptive immune system. Mol Immunol. 2010;47:903–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hiebert PR, Granville DJ. Granzyme B in injury, inflammation, and repair. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18:732–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Joeckel LT, Wallich R, Martin P, et al. Mouse granzyme K has pro-inflammatory potential. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:1112–1119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Spaeny-Dekking EH, Hanna WL, Wolbink AM, et al. Extracellular granzymes A and B in humans: detection of native species during CTL responses in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1998;160:3610–3616 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lauw FN, Simpson AJ, Hack CE, et al. Soluble granzymes are released during human endotoxemia and in patients with severe infection due to gram-negative bacteria. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:206–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Darmon AJ, Ehrman N, Caputo A, Fujinaga J, Bleackley RC. The cytotoxic T cell proteinase granzyme B does not activate interleukin-1 β-converting enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32043–32046 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Spencer CT, Abate G, Sakala IG, et al. Granzyme A produced by γ(9)δ(2) T cells induces human macrophages to inhibit growth of an intracellular pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rudack C, Steinhoff M, Mooren F, et al. PAR-2 activation regulates IL-8 and GRO-α synthesis by NF-κB, but not RANTES, IL-6, eotaxin or TARC expression in nasal epithelium. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:1009–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Megyeri P, Pabst KM, Pabst MJ. Serine protease inhibitors block priming of monocytes for enhanced release of superoxide. Immunology. 1995;86:629–635 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim H, Lee HS, Chang KT, Ko TH, Baek KJ, Kwon NS. Chloromethyl ketones block induction of nitric oxide synthase in murine macrophages by preventing activation of nuclear factor-κ B. J Immunol. 1995;154:4741–4748 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Polytarchou C, Papadimitriou E. Antioxidants inhibit human endothelial cell functions through down-regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;510:31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Powers JC, Asgian JL, Ekici OD, James KE. Irreversible inhibitors of serine, cysteine, and threonine proteases. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4639–4750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Angele MK, Schwacha MG, Ayala A, Chaudry IH. Effect of gender and sex hormones on immune responses following shock. Shock. 2000;14:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ansar Ahmed S, Penhale WJ, Talal N. Sex hormones, immune responses, and autoimmune diseases. Mechanisms of sex hormone action. Am J Pathol. 1985;121:531–551 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carlsten H, Holmdahl R, Tarkowski A, Nilsson LA. Oestradiol suppression of delayed-type hypersensitivity in autoimmune (NZB/NZW)F1 mice is a trait inherited from the healthy NZW parental strain. Immunology. 1989;67:205–209 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Frink M, Thobe BM, Hsieh YC, et al. 17β-Estradiol inhibits keratinocyte-derived chemokine production following trauma-hemorrhage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L585–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Klein PW, Easterbrook JD, Lalime EN, Klein SL. Estrogen and progesterone affect responses to malaria infection in female C57BL/6 mice. Gend Med. 2008;5:423–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Offner H, Adlard K, Zamora A, Vandenbark AA. Estrogen potentiates treatment with T-cell receptor protein of female mice with experimental encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1465–1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Seaman WE, Blackman MA, Gindhart TD, Roubinian JR, Loeb JM, Talal N. β-Estradiol reduces natural killer cells in mice. J Immunol. 1978;121:2193–2198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rissman EF, Heck AL, Leonard JE, Shupnik MA, Gustafsson JA. Disruption of estrogen receptor β gene impairs spatial learning in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3996–4001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Karas RH, Schulten H, Pare G, et al. Effects of estrogen on the vascular injury response in estrogen receptor α, β (double) knockout mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:534–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ng KY, Yong J, Chakraborty TR. Estrous cycle in ob/ob and ovariectomized female mice and its relation with estrogen and leptin. Physiol Behav. 2010;99:125–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Karpuzoglu E, Ahmed SA. Estrogen regulation of nitric oxide and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in immune cells: implications for immunity, autoimmune diseases, and apoptosis. Nitric Oxide. 2006;15:177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Rose NL, Palcic MM, Helms LM, Lakey JR. Evaluation of Pefabloc as a serine protease inhibitor during human-islet isolation. Transplantation. 2003;75:462–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Köck A, Schwarz T, Kirnbauer R, et al. Human keratinocytes are a source for tumor necrosis factor α: evidence for synthesis and release upon stimulation with endotoxin or ultraviolet light. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1609–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pasternack MS, Eisen HN. A novel serine esterase expressed by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature. 1985;314:743–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McDonald D, Carrero G, Andrin C, de Vries G, Hendzel MJ. Nucleoplasmic β-actin exists in a dynamic equilibrium between low-mobility polymeric species and rapidly diffusing populations. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:541–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Philimonenko VV, Zhao J, Iben S, et al. Nuclear actin and myosin I are required for RNA polymerase I transcription. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1165–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Shumaker DK, Kuczmarski ER, Goldman RD. The nucleoskeleton: lamins and actin are major players in essential nuclear functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:358–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Khan D, Dai R, Karpuzoglu E, Ahmed SA. Estrogen increases, whereas IL-27 and IFN-γ decrease, splenocyte IL-17 production in WT mice. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2549–2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lengi AJ, Phillips RA, Karpuzoglu E, Ahmed SA. Estrogen selectively regulates chemokines in murine splenocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1065–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Grigera F, Bellacosa A, Kenter AL. Complex relationship between mismatch repair proteins and MBD4 during immunoglobulin class switch recombination. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hoffman-Goetz I. Serine esterase (BLT-esterase) activity in murine splenocytes is increased with exercise but not training. Int J Sports Med. 1995;16:94–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sayers TJ, Mason LH, Pilaro A, et al. Substrate-specific proteases (BLT-esterase) are localized predominantly in the natural killer cells of unprimed mice. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;53:454–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Aebischer F, Schlegel-Haueter SE. Glucocorticoids modulate the induction of BLTE/granzyme A activity in the murine T cell hybridoma PC60. Immunopharmacology. 1992;23:181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rak GD, Mace EM, Banerjee PP, Svitkina T, Orange JS. Natural killer cell lytic granule secretion occurs through a pervasive actin network at the immune synapse. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dinarello CA. A clinical perspective of IL-1β as the gatekeeper of inflammation. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1203–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Liew FY, Pitman NI, McInnes IB. Disease-associated functions of IL-33: the new kid in the IL-1 family. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:103–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Fallon PG, Jolin HE, Smith P, et al. IL-4 induces characteristic Th2 responses even in the combined absence of IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. Immunity. 2002;17:7–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Stefanis L, Troy CM, Qi H, Greene LA. Inhibitors of trypsin-like serine proteases inhibit processing of the caspase Nedd-2 and protect PC12 cells and sympathetic neurons from death evoked by withdrawal of trophic support. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1425–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Dentan C, Tselepis AD, Chapman MJ, Ninio E. Pefabloc, 4-[2-aminoethyl]benzenesulfonyl fluoride, is a new, potent nontoxic and irreversible inhibitor of PAF-degrading acetylhydrolase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1299:353–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ansel KM, Djuretic I, Tanasa B, Rao A. Regulation of Th2 differentiation and Il4 locus accessibility. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:607–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mo C, Chearwae W, O'Malley JT, et al. Stat4 isoforms differentially regulate inflammation and demyelination in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;181:5681–5690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Ning Q, Berger L, Luo X, et al. STAT1 and STAT3 α/β splice form activation predicts host responses in mouse hepatitis virus type 3 infection. J Med Virol. 2003;69:306–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Suzuki K, Nakajima H, Kagami S, et al. Proteolytic processing of Stat6 signaling in mast cells as a negative regulatory mechanism. J Exp Med. 2002;196:27–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kotanides H, Reich NC. Interleukin-4-induced STAT6 recognizes and activates a target site in the promoter of the interleukin-4 receptor gene. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25555–25561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hebenstreit D, Wirnsberger G, Horejs-Hoeck J, Duschl A. Signaling mechanisms, interaction partners, and target genes of STAT6. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:173–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tang X, Marciano DL, Leeman SE, Amar S. LPS induces the interaction of a transcription factor, LPS-induced TNF-α factor, and STAT6(B) with effects on multiple cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5132–5137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zhu J. Transcriptional regulation of Th2 cell differentiation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:244–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zhu J, Yamane H, Cote-Sierra J, Guo L, Paul WE. GATA-3 promotes Th2 responses through three different mechanisms: induction of Th2 cytokine production, selective growth of Th2 cells and inhibition of Th1 cell-specific factors. Cell Res. 2006;16:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Maneechotesuwan K, Xin Y, Ito K, et al. Regulation of Th2 cytokine genes by p38 MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of GATA-3. J Immunol. 2007;178:2491–2498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Webb BJ, Bochan MR, Montel A, Padilla LM, Brahmi Z. The lack of NK cytotoxicity associated with fresh HUCB may be due to the presence of soluble HLA in the serum. Cell Immunol. 1994;159:246–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. DeBlaker-Hohe DF, Yamauchi A, Yu CR, Horvath-Arcidiacono JA, Bloom ET. IL-12 synergizes with IL-2 to induce lymphokine-activated cytotoxicity and perforin and granzyme gene expression in fresh human NK cells. Cell Immunol. 1995;165:33–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lauw FN, te Velde AA, Dekkers PE, et al. Activation of mononuclear cells by interleukin-12: an in vivo study in chimpanzees. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hartmann W, Marsland BJ, Otto B, Urny J, Fleischer B, Korten S. A novel and divergent role of granzyme A and B in resistance to helminth infection. J Immunol. 2011;186:2472–2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lee CK, Rao DT, Gertner R, Gimeno R, Frey AB, Levy DE. Distinct requirements for IFNs and STAT1 in NK cell function. J Immunol. 2000;165:3571–3577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Joffroy CM, Buck MB, Stope MB, Popp SL, Pfizenmaier K, Knabbe C. Antiestrogens induce transforming growth factor β-mediated immunosuppression in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1314–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hao S, Zhao J, Zhou J, Zhao S, Hu Y, Hou Y. Modulation of 17β-estradiol on the number and cytotoxicity of NK cells in vivo related to MCM and activating receptors. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:1765–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Spaeny-Dekking EH, Kamp AM, Froelich CJ, Hack CE. Extracellular granzyme A, complexed to proteoglycans, is protected against inactivation by protease inhibitors. Blood. 2000;95:1465–1472 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zeitler CE, Estes MK, Venkataram Prasad BV. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus protease at 1.5-A resolution. J Virol. 2006;80:5050–5058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Pierdominici M, Maselli A, Colasanti T, et al. Estrogen receptor profiles in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Immunol Lett. 2010;132:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Morley P, Whitfield JF, Vanderhyden BC, Tsang BK, Schwartz JL. A new, nongenomic estrogen action: the rapid release of intracellular calcium. Endocrinology. 1992;131:1305–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Marino M, Pallottini V, Trentalance A. Estrogens cause rapid activation of IP3-PKC-α signal transduction pathway in HEPG2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;245:254–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Pardo J, Buferne M, Martínez-Lorenzo MJ, et al. Differential implication of protein kinase C isoforms in cytotoxic T lymphocyte degranulation and TCR-induced Fas ligand expression. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1441–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Bell JK, Goetz DH, Mahrus S, Harris JL, Fletterick RJ, Craik CS. The oligomeric structure of human granzyme A is a determinant of its extended substrate specificity. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Kam CM, Hudig D, Powers JC. Granzymes (lymphocyte serine proteases): characterization with natural and synthetic substrates and inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:307–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Walsmann P, Richter M, Markwardt F. Inactivation of trypsin and thrombin by 4-amidinobenzolsulfofluoride and 4-(2-aminoethyl)-benzolsulfofluoride [in German]. Acta Biol Med Ger. 1972;28:577–585 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Brown GR, McGuire MJ, Thiele DL. Dipeptidyl peptidase I is enriched in granules of in vitro- and in vivo-activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1993;150:4733–4742 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Yamada M, Hirasawa A, Shiojima S, Tsujimoto G. Granzyme A mediates glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells. FASEB J. 2003;17:1712–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Tremblay GM, Wolbink AM, Cormier Y, Hack CE. Granzyme activity in the inflamed lung is not controlled by endogenous serine proteinase inhibitors. J Immunol. 2000;165:3966–3969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Shresta S, Goda P, Wesselschmidt R, Ley TJ. Residual cytotoxicity and granzyme K expression in granzyme A-deficient cytotoxic lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20236–20244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Hameed A, Lowrey DM, Lichtenheld M, Podack ER. Characterization of three serine esterases isolated from human IL-2 activated killer cells. J Immunol. 1988;141:3142–3147 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Hanna WL, Zhang X, Turbov J, Winkler U, Hudig D, Froelich CJ. Rapid purification of cationic granule proteases: application to human granzymes. Protein Expr Purif. 1993;4:398–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Bade B, Lohrmann J, ten Brinke A, et al. Detection of soluble human granzyme K in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2940–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Kim HS, Chung DH. TLR4-mediated IL-12 production enhances IFN-γ and IL-1β production, which inhibits TGF-β production and promotes antibody-induced joint inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Wesa AK, Galy A. IL-1 β induces dendritic cells to produce IL-12. Int Immunol. 2001;13:1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. van de Wetering D, de Paus RA, van Dissel JT, van de Vosse E. Salmonella induced IL-23 and IL-1β allow for IL-12 production by monocytes and Mphi1 through induction of IFN-γ in CD56 NK/NK-like T cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Martinvalet D, Walch M, Jensen DK, Thiery J, Lieberman J. Response: Granzyme A: cell death–inducing protease, proinflammatory agent, or both? Blood. 2009;114:3969–3970 [Google Scholar]

- 117. Patel BK, Pierce JH, LaRochelle WJ. Regulation of interleukin 4-mediated signaling by naturally occurring dominant negative and attenuated forms of human Stat6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:172–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Tang X, Yang Y, Amar S. Novel regulation of CCL2 gene expression by murine LITAF and STAT6B. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Zhu J, Cote-Sierra J, Guo L, Paul WE. Stat5 activation plays a critical role in Th2 differentiation. Immunity. 2003;19:739–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ahn HJ, Tomura M, Yu WG, et al. Requirement for distinct Janus kinases and STAT proteins in T cell proliferation versus IFN-γ production following IL-12 stimulation. J Immunol. 1998;161:5893–5900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Gollob JA, Murphy EA, Mahajan S, Schnipper CP, Ritz J, Frank DA. Altered interleukin-12 responsiveness in Th1 and Th2 cells is associated with the differential activation of STAT5 and STAT1. Blood. 1998;91:1341–1354 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Takatori H, Nakajima H, Kagami S, et al. Stat5a inhibits IL-12-induced Th1 cell differentiation through the induction of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 expression. J Immunol. 2005;174:4105–4112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]