Abstract

The uterotropic response of the uterus to 17β-estradiol (E2) is genetically controlled, with marked variation observed depending on the mouse strain studied. Previous genetic studies from our laboratory using inbred mice that are high (C57BL6/J; B6) or low (C3H/HeJ; C3H) responders to E2 led to the identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL) associated with phenotypic variation in uterine growth and leukocyte infiltration. Like the uterus, phenotypic variation in the responsiveness of the mammary gland to E2 during both normal and pathologic conditions has been reported. In the current experiment, we utilized an E2-specific model of mammary ductal growth combined with a microarray approach to determine the degree to which genotype influences the responsiveness of the mammary gland to E2, including the associated transcriptional programs, in B6 and C3H mice. Our results reveal that E2-induced mammary ductal growth and ductal morphology are genetically controlled. In addition, we observed a paradoxical effect of mammary ductal growth in response to E2 compared with what has been reported for the uterus; B6 is a high responder for the uterus and was a low responder for mammary ductal growth, whereas the reverse was observed for C3H. In contrast, B6 was a high responder for mammary ductal side branching. The B6 phenotype was associated with increased mammary epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis, and a distinct E2-induced transcriptional program. These findings lay the groundwork for future experiments designed to investigate the genes and mechanisms underlying phenotypic variation in tissue-specific sensitivity to systemic and environmental estrogens during various physiological and disease states.

Estrogens are female sex hormones that are involved in a variety of physiological processes including reproductive development and function, wound healing, and bone growth (1, 2). Estrogens are mainly known for their role in reproductive tissues, specifically the ability of 17β-estradiol (E2), the primary estrogen secreted by the ovary, to induce cellular proliferation and growth of the uterus and mammary gland. In the uterus, E2 elicits a marked increase in epithelial cell proliferation, vascular permeability and water imbibition, followed by an influx of leukocytes into the uterine stroma, that together comprise the classical uterotropic response (3). In the mammary gland, E2 promotes the proliferation of epithelial cells and elongation of mammary ducts (4–6). In addition to the role of estrogens in promoting uterine and mammary development during normal physiological states, they have a well-established role in determining susceptibility to disease, particularly cancer, in reproductive tissues (7–10). Early studies demonstrated that responsiveness of the uterus and mammary gland to E2 is genetically controlled, with marked variation in tissue growth and (or) regression observed depending on the strain of mouse studied (11–14). Like the uterus (11), phenotypic variation in the responsiveness of the adult mammary gland to E2 during both normal and pathologic conditions, including tumor formation, has been reported (12–14).

Previously, research from our laboratory showed that the infiltration of leukocytes, particularly eosinophils, into the uterine stroma is genetically determined (15). Our subsequent work using inbred strains of mice that are high responders (C57BL6/J; B6) or low responders (C3H/HeJ; C3H) to E2 led to the identification of the quantitative trait loci (QTL) controlling quantitative variation in uterine growth and eosinophil infiltration (15, 16). Recently, we used a microarray approach to compare the E2-regulated transcriptional responses of the uteri from B6, C3H, and (B6 × C3H) F1 hybrid mice (B6C3) and discovered that the genetically-controlled high and low responses to E2 are associated with distinct transcriptional signatures, inheritance patterns, and functional pathways, including an increase in uterine epithelial cell apoptosis in C3H versus B6 after treatment with E2 (17). In addition, when microarray results were combined with data from our previous genetic mapping experiments, positional candidate genes controlling the E2-regulated uterotropic response were identified (17).

Although there have been efforts made to identify QTL associated with the susceptibility to E2-induced mammary cancer in rodent models (18), no genome-wide mapping experiments have been conducted to identify the genes controlling the phenotypic variation in the mammary response to E2 under normal physiological conditions. In addition, many of the reports investigating the genetic control of the mammary response to E2 were prior to 1999 (12, 14, 19), when mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) was eradicated from inbred mice (The Jackson Laboratory, personal communication). MMTV is a virus that induces spontaneous mammary tumors in certain strains of mice; therefore, many of the studies investigating the strain differences in the response of the mammary gland to E2 that were published prior to 1999 were either confounded by the presence of MMTV or were designed to investigate the mammary response to E2 in the context of MMTV (13, 14, 19–24). More recent reports have confirmed that even in the absence of MMTV, the response of the mammary gland to E2 and progesterone (25), and also to environmental estrogens (26, 27), is genetically controlled. A clearer understanding of the genetic factors controlling the response of the mammary gland to E2 under normal, nonpathological conditions could provide critical insight into understanding the factors regulating susceptibility to and treatment of breast cancer, both of which also exhibit marked variation depending on the genotype of the individual (28–30).

In the current experiment, we utilized an E2-specific model of mammary ductal growth combined with a microarray approach to determine the degree to which genotype influences the responsiveness of the mammary gland to E2 in B6 and C3H mice, as well as the transcriptional programs associated with each response. Our results reveal that E2-induced mammary ductal growth, as well as ductal morphology, is genetically controlled. In addition, we observed a paradoxical effect of mammary ductal growth in response to E2 compared with what has been reported for the uterus; B6 is a high responder for the uterus and was a low responder for mammary ductal growth, whereas the reverse was observed for C3H. In contrast, B6 was a high responder for mammary ductal side branching. Relative to C3H, the B6 phenotype was associated with increased mammary epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis, as well as a distinct E2-induced transcriptional program. These findings lay the groundwork for future experiments designed to investigate the genes and mechanisms underlying phenotypic variation in tissue-specific sensitivity to systemic and environmental estrogens during various physiological and disease states.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Ovariectomized (OVX) female B6 and C3H mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All experimental procedures performed in this study were under the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Vermont. The animals were treated humanely and with regard for alleviation of suffering.

E2-induced mammary ductal growth

Four-week-old female B6 and C3H mice OVX prior to puberty (approximately 3–4 weeks of age; average BW = 18.8 g for B6 mice and 18.9 g for C3H mice) were rested 1 to 2 weeks after arrival and then subjected to treatment with either E2 (40.0 μg/kg BW injected ip) in 0.1 ml saline containing 0.25% ethanol, or ethanol/saline vehicle (n = 15 E2 mice per strain and 10 vehicle mice per strain; 50 mice total). Animals were given two injections 24 hours apart, and were euthanized and tissues collected at 72 hours after the first injection on day 4 of the experiment. Mammary tissue was collected and whole mounts were prepared as described elsewhere (31, 32). The stained mammary whole mounts were examined with an Olympus BX50 upright light microscope (Olympus America) with a PLAN 2X objective lens. Images were acquired in 12-bit monochrome mode with an attached QImaging Retiga 2000R digital ccd camera.

Images of ducts that were too large to fit in one 2× field were taken into Photoshop (version CS6) for image stitching. Images were aligned using a combination of the transform tools to rotate, precisely fit, and stitch images together. After stitching, the composite image was saved as a Tiff for morphometric anaylsis. Transmitted light images were analyzed using MetaMorph Imaging series 7.0 (version 7.8.2) image analysis software (Molecular Devices). After manual tracing of the ductal tree on each image, the following measurements were obtained using the ROI and line tools:

Ductal length (mm) = distance measurement from the base of the ductal tree to the furthest branching point from the base (furthest terminal end bud beyond the lymph node)

Ductal area (mm2) = area of the smallest polygon that incases the entire ductal tree

Primary ducts (#) = any ducts that originate from the main ductal trunk

Secondary ducts (#) = any ducts that branch directly from a primary duct

Tertiary ducts (#) = any ducts that branch directly from a secondary duct

Total branches = sum of branches of the ductal tree using the ductal base as a starting point.

Transcriptional and cellular responses of mouse mammary gland to E2

Four-week-old female B6 and C3H mice OVX prior to puberty (approximately 3–4 weeks of age) were rested 1 to 2 weeks after arrival and then subjected to treatment with either E2 (40.0 μg/kg BW injected i.p.) in 0.1 ml saline containing 0.25% ethanol, or ethanol/saline vehicle (n = 10 mice/strain/treatment; 40 mice total). Animals were given two injections 24 hours apart, and were euthanized and tissues collected at 72 hours after the first injection, on day 4 of the experiment. Uteri and first inguinal mammary glands were collected, blotted, and weighed. For uteri, one horn was fixed in 10% formalin and the other was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent RNA isolation. For mammary glands, one was fixed in 10% formalin and the contralateral gland was dissected to remove the mammary lymph node and then was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent RNA isolation.

Microarray analysis

Frozen uterine and mammary tissue from 3 animals per group was pulverized, then homogenized in Trizol (Invitrogen), and RNA was prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol. Isolated RNA was then further purified using the QIAGEN RNeasy mini prep kit clean-up protocol.

Gene expression analysis on each individual sample (n = 1 mouse per array; 3 arrays per group) was conducted using Illumina MouseWG-6 version 2.0 Expression BeadChip array (BD-201-0202; Illumina, Inc). RNA quantity and quality were assessed using NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies), respectively. RNA (250 ng) was amplified and converted to cRNA using Illumina TotalPrep-96 RNA Amplification kit (Ambion). cRNA (750 ng) was used for hybridization onto the Illumina Whole-Genome Gene Expression Direct Hybridization microarray (Illumina). The R software running the lumi package was used for normalization.

Microarray data were analyzed using Partek Genomics Suite® 6.6 software. Data were subjected to ANOVA to determine the effect of strain, treatment, tissue type, and interactions on probe intensity, and mouse was included in the model as a random effect. Probes were considered differentially expressed if the signed fold change was ≥2 and P < .05.

Histological analyses

For histological analyses, fixed mammary tissue was embedded in paraffin, sectioned at approximately 4 μm thickness and mounted onto silanized slides.

Immunofluorescence

An anti-runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1)/AML1 rabbit monoclonal antibody (Abcam) was used to determine the expression pattern of RUNX1 in the mammary gland. For cleaved caspase-3 (CC3), an anti-CC3 (D175) rabbit polyclonal antibody (Cell Signaling) was used. For estrogen receptor-α (ESR1), an anti-ESR1 mouse monoclonal antibody (PN IM1545, Beckman Coulter) was used. For Ki-67, an anti-Ki-67 rabbit polyclonal antibody (ab15580, Abcam) was used. Immune staining and imaging was performed as previously described (17).

MetaMorph image analysis

Quantification of CC3, Ki-67, ESR1, or RUNX1 expression was performed using MetaMorph offline software version 7.7.3 64 bit (Molecular Devices). At least two fields per sample were imaged and quantified, and all samples were coded to prevent observer bias. For all samples, an inclusive threshold was used with a lower limit of 1500 and an upper limit of 4095 (default maximum). The regional measurements tool was used to quantify the integrated intensity of ESR1 or RUNX1 staining in the mammary epithelium; all epithelial structures in all fields were included. For quantification of staining in the stroma, the integrated intensity of the entire image was calculated, and the integrated intensity from the epithelium for that field was subtracted from the total to give the integrated intensity in the stromal compartment. For CC3 and Ki-67, the number of positive epithelial cells was manually counted.

Statistical analyses

Data were subjected to 2-way ANOVA using the Mixed Procedure of SAS (SAS Inst Inc; version 9.1) to determine the effect of strain, E2 treatment, and the strain by treatment interaction on mammary ductal length, ductal tree area, number of primary, secondary, and tertiary ducts, total branches, and mammary epithelial ESR1 expression. The model included treatment as a fixed variable and mouse as a random variable. The comparison of means between strains was performed using Fisher's protected Least Significant Difference test, and significance was declared at P < .05. To determine the effect of strain on expression of CC3 or Ki-67 after E2 treatment, or RUNX1 expression in vehicle-treated control animals, data from B6 and C3H mice were log10-transformed to achieve a normal distribution and were then subjected to a two-tailed t test within SAS. Significance was declared at P < .05. GraphPad Prism was used to determine the correlation between E2-induced mammary ductal growth versus E2-induced uterine growth, E2-induced mammary ductal side branching versus E2-induced uterine growth, and also between E2-induced tissue growth and RUNX1 expression at baseline.

Results

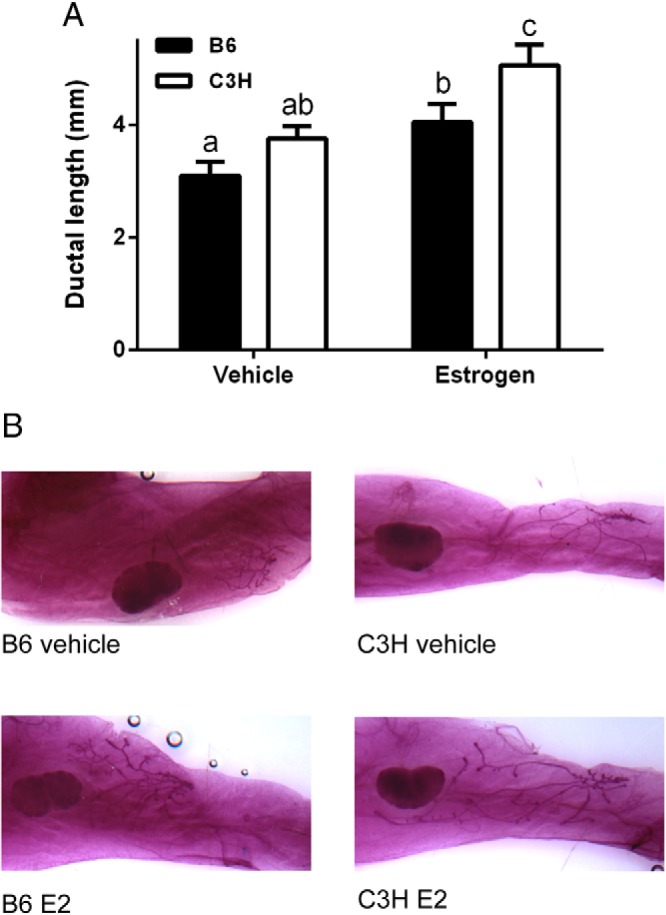

Genetic control of mammary ductal length and morphology

In order to determine the degree to which genotype influences mammary responsiveness to E2, we utilized an E2-specific mammary ductal growth model. After treatment with E2, an increase in mammary ductal length was readily visible for both strains (main effect of E2, P < .001; Figure 1A), and the degree of mammary ductal growth was consistent with previous reports (33). Interestingly, there were striking differences in mammary ductal morphology in both E2- and vehicle-treated control mice (Figure 1B). In vehicle-treated control B6 mice, the mammary ducts were consistently short and highly branched, with many end buds visible. In contrast, mammary ducts of C3H mice were very long and thin, with much less branching. Although the difference in ductal length between the strains was not significant in vehicle-treated control animals (P = .08; Figure 1A), the images illustrate what was consistently observed. The differences in ductal morphology, specifically ductal length, seemed to be increased after treatment because ductal length was significantly different between strains in E2-treated animals (P < .01; Figure 1A). The percent increase in ductal length relative to control animals, however, was not different between the strains (131 ± 14% for B6 vs 147 ± 15% for C3H; P = .40). To further characterize strain differences in ductal morphology, we determined the area of the ductal tree and quantified the number of primary, secondary, and tertiary ducts, and total ductal branches (Table 1). Consistent with our visual observations, the ductal tree of C3H was larger in area than B6 mice (P < .04), likely a result of the longer ducts, whereas the ductal tree of B6 mice was much more extensively branched than that of C3H mice (P < .001). This was observed in both vehicle and E2-treated mice, with no significant treatment by strain interactions; however, the difference between strains in total branches was only significant in E2-treated mice (P < .001; Table 1). Our observations reveal that E2-induced changes in mammary ductal length and morphology, like the uterotropic response (17), are genetically controlled.

Figure 1.

Genetic control of mammary ductal length. A, Ductal length in the mammary gland of B6 and C3H mice 72 hours after vehicle or E2 treatment. The distance from the outermost edge of the lymph node (side nearest the nipple) to the furthest terminal end bud beyond the node was measured (a, b, c = P < .05). B, Whole-mounts of mammary glands from vehicle or E2-treated mice 72 hours after treatment.

Table 1.

Characterization of Mammary Ductal Growth in Response to E2

| Vehicle |

Estrogen |

sem |

P-Value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 | C3H | B6 | C3H | Strain | Treatment | Strain * Treatment | ||

| Ductal Tree Area (mm2) | 0.93a | 1.54a | 1.71b | 2.08b | 0.18 | .04 | .01 | .50 |

| Primary ducts (#) | 3.25 a | 4.00a | 2.26b | 2.42b | 0.24 | .17 | <.001 | .30 |

| Secondary ducts (#) | 10.33 | 12.60 | 14.20 | 11.90 | 1.38 | .99 | .40 | .20 |

| Tertiary ducts (#) | 22.25A | 8.66B | 29.13A | 13.15B | 2.45 | <.001 | .13 | .74 |

| Total branches (#) | 35.00 | 23.66 | 44.90A | 27.46B | 3.36 | <.001 | .16 | .50 |

Means in the same row with different superscripts indicate that differences between vehicle and E2-treatment mice within the same strain are significant (P < .05).

Means in the same row with different superscripts indicate that differences between strains within the same treatment group are significant (P < .05).

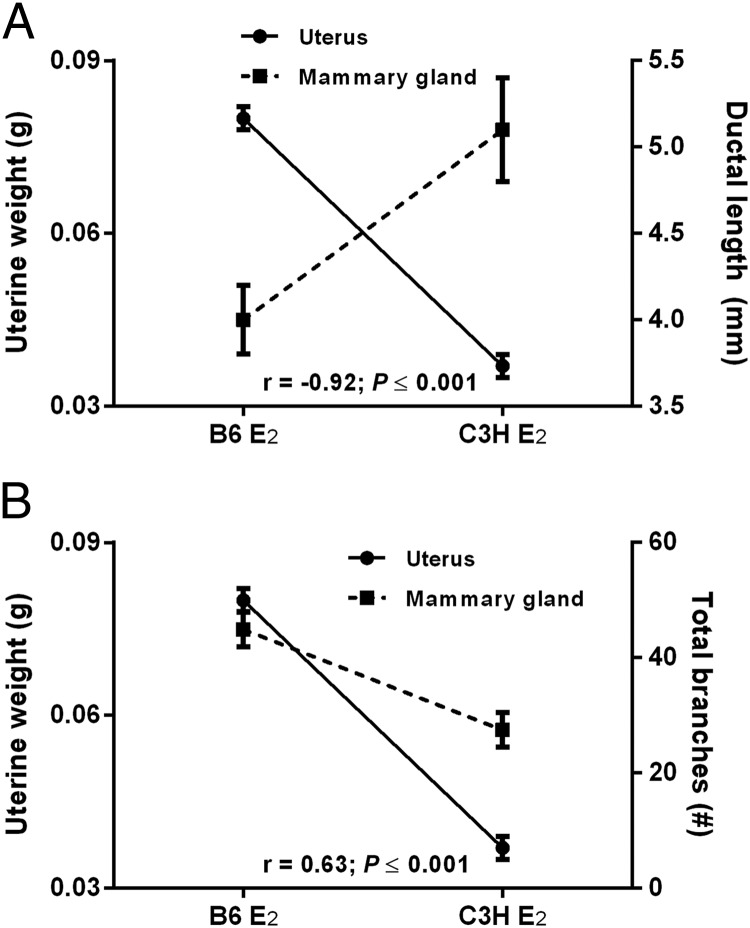

Relationship between the genetically-controlled response of uterus versus mammary gland to E2

Paradoxically, strains observed to be high uterine responders to E2 are often low mammary gland responders (12, 14). To determine if this yin-yang relationship also exists in B6 and C3H mice, we compared the uterine versus mammary responses to E2 and observed that the uterine response to E2 was negatively correlated with the E2-induced increase in mammary ductal length (r = −0.92; P ≤ .001; Figure 2A) but positively correlated with the E2-induced increase in ductal side branching (r = +0.63; P < .001; Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Relationship between the response of uterus and mammary gland to E2. A, Uterine weight is negatively correlated with the increase in mammary ductal length 72 hours after treatment with E2. B, Uterine weight is positively correlated with ductal side branching 72 hours after treatment with E2.

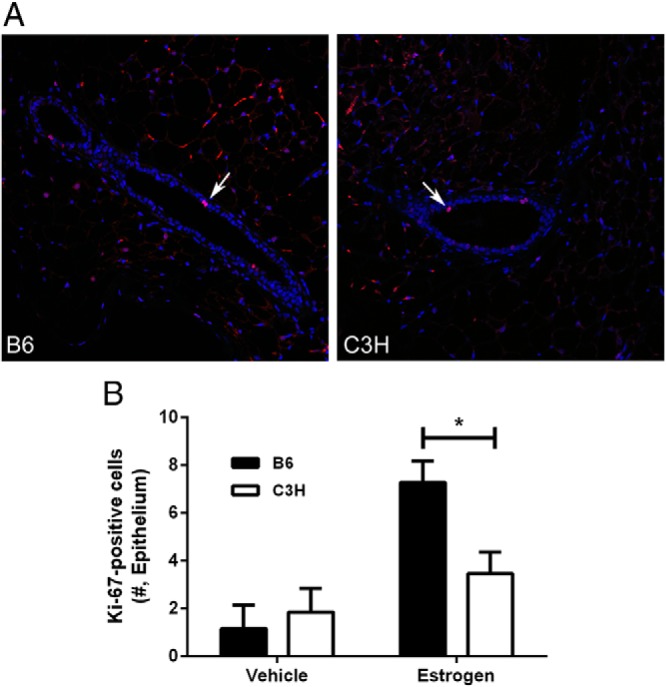

Mammary epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis after treatment with E2 is genetically controlled

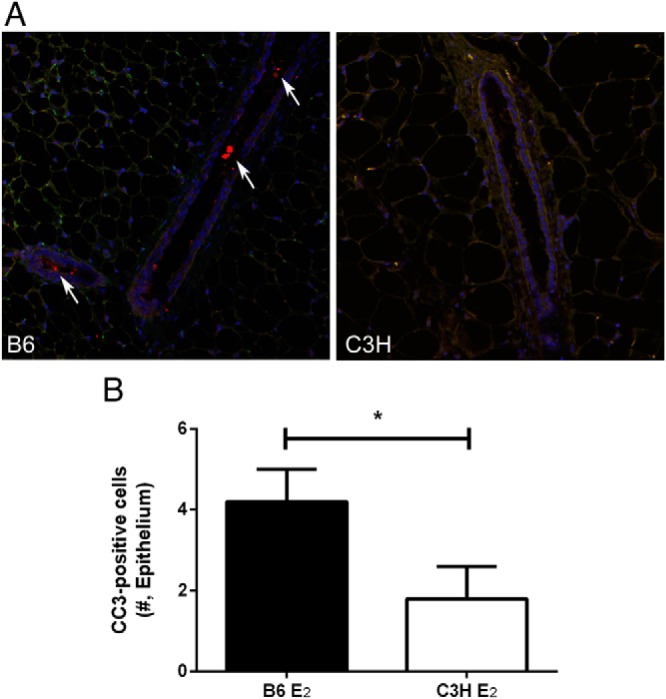

Because our previous observations revealed that cellular apoptosis was associated with decreased uterine growth after treatment with E2 (17), and that there is a relationship between E2-induced uterine and mammary growth (Figure 2A and B), we measured expression of the proliferation marker Ki-67 (Figure 3A) and the apoptosis marker cleaved CC3(Figure 4A) in mammary sections 72 hours after E2 treatment. In both strains, the number of Ki-67 positive mammary epithelial cells was very low but increased after E2 treatment (P < .001; Figure 3B). In addition, there was a strain by treatment interaction (P < .05) such that the E2-induced increase in Ki-67 expression was greater in B6 mice relative to C3H (P < .05; Figure 3B). Mammary epithelial cell apoptosis, as measured by CC3 expression, was also very low (Figure 4A). In contrast to our observations in uterus (17), but consistent with the negative relationship between uterine growth and mammary ductal length (Figure 2A), cells expressing CC3 were nearly undetectable in C3H mice whereas they were detectable in the mammary epithelium and sometimes within the ductal lumen of B6 mice (Figure 4A). Quantification of cellular staining confirmed these visual observations, with CC3 expression higher in B6 relative to C3H (P < .05; Figure 4B). These results indicate that the proliferative and apoptotic response of mammary epithelial cells to E2 is genetically controlled.

Figure 3.

Proliferation in mammary epithelium in 72 hours after treatment with E2. A, localization of Ki-67 (red = Ki-67, blue = DAPI, green = autofluorescence; 20x magnification). White arrows indicate positively labeled epithelial cells. B, Quantity of Ki67 expression in mammary epithelium of vehicle- or E2-treated B6 and C3H mice (*, P < .05).

Figure 4.

Apoptosis in mammary epithelium 72 hours after treatment with E2. A, localization of CC3 (red = CC3, blue = DAPI, green = autofluorescence; 20x magnification). White arrows indicate positively labeled cells in the ductal lumen of a B6 mouse (cells expressing CC3 were nearly undetectable in C3H mice). B, Quantity of CC3 expression in mammary epithelium of B6 and C3H mice (*, P < .05).

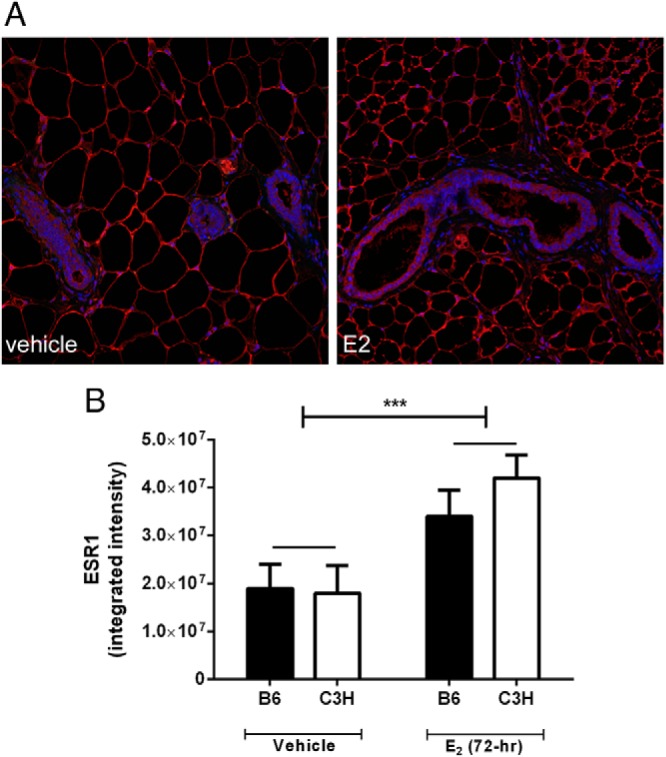

Consistent with our previous observations in the uterus (17), mammary epithelial expression of ESR1 was not different between the strains (P > .80; Figure 5, A and B), but was increased after treatment with E2 (P < .001). Interestingly, the increase in expression of ESR1 after E2 treatment appeared to be due to an increase in the intensity per cell and not due to an increase in the number of positive cells (See Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

ESR1 expression in mouse mammary gland. A, localization of ESR1 in mouse mammary gland (red = ESR1, blue = DAPI; 20x magnification). B, Quantity of ESR1 in the mammary epithelium of B6 and C3H mice (***, P < .001).

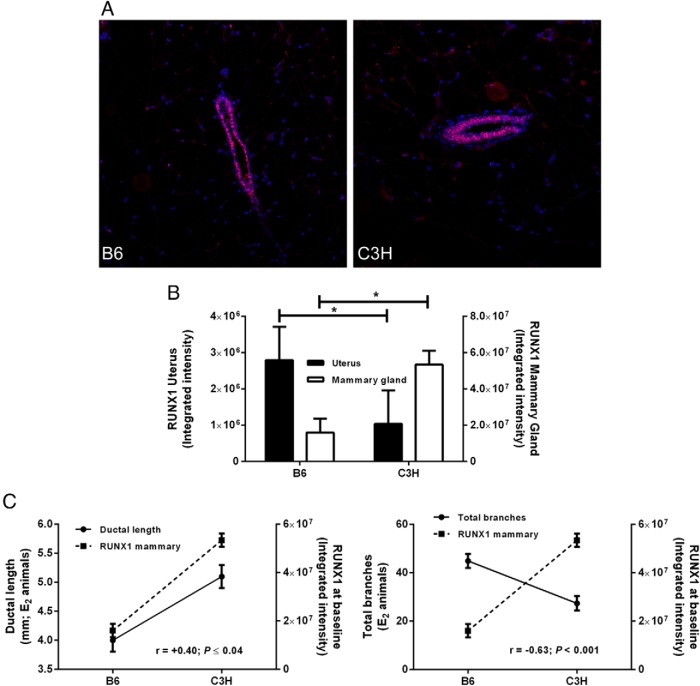

Expression of RUNX1 is genetically controlled and is associated with E2-induced changes in mammary ductal growth and side branching

To further explore the relationship between the response of the uterus and mammary gland to E2, we selected Runx1, a positional candidate gene for a cis-eQTL on chromosome 16 that epistatically interacts with other QTL controlling uterine responsiveness to E2 (15–17), and quantified protein expression in the uterus and mammary gland. Our observations revealed that, as for the uterus (17), expression of RUNX1 is restricted mainly to the mammary epithelium (Figure 6A). We also found that, in agreement with our observations in the uterus (17), RUNX1 expression in the mammary gland is genetically controlled (Figure 6B). Additionally, the genetic control of RUNX1 expression was reciprocal across the two tissues; we observed higher expression of RUNX1 in uteri of B6 versus C3H mice, whereas in the mammary gland RUNX1 expression was higher in C3H mice (Figure 6B). This reciprocal relationship has clear functional relevance; expression of RUNX1 was positively correlated with both the E2-induced increase in uterine weight (r = +0.97; P < .0001; data not shown) and the increase in mammary ductal length (r = +0.40; P < .04; Figure 6C, left panel), whereas it was negatively correlated with E2-inuced ductal side branching (r = −0.63; P < .001; Figure 6C, right panel).

Figure 6.

RUNX1 expression in mouse uterus and mammary gland. A, localization of RUNX1 in mouse mammary gland (red = RUNX1, blue = DAPI; 20x magnification). B, Quantity of RUNX1 in the uterine and mammary epithelium of B6 and C3H mice (*, P < .05). C, Basal expression of RUNX1 is positively correlated with ductal length 72 hours after treatment with E2 (left panel) and is negatively correlated with ductal branching 72 hours after treatment with E2 (right panel).

Strain-specific transcriptional responses to E2

In order to determine the role of genotype in controlling the transcriptional response of the mammary gland to E2, and to identify genes associated with the strain-specific response to E2, we conducted a microarray experiment on mammary tissue from B6 and C3H mice at 72 hours after E2 treatment. The results of the microarray experiment revealed 313 genes that were E2-regulated in at least one strain (P < .05 and signed fold change ≥2; (Supplemental Table 1). Despite some common E2-regulated genes between the strains (18 genes; Supplemental Table 1; common genes in bold), most the transcriptional response of the mammary gland in each strain was associated with distinct genes. Venn diagrams were generated to summarize the common and distinct E2-regulated genes across both tissues in the two strains (Supplemental Figure 1A), as well as tissue-specific E2-regulated genes (Supplemental Figure 1B). We also conducted correlation analyses to determine the relationship between E2-induced differential gene expression in B6 versus C3H mouse uterus (Supplemental Figure 2A) and mammary gland (Supplemental Figure 2B), as well as uterus versus mammary gland (Supplemental Figure 2C). Consistent with our previous observations (17), we found a strong positive correlation in the differential expression of E2-regulated genes in the uterus of B6 and C3H mice (Supplemental Figure 2A). In contrast, there was no correlation in the differential expression of E2-responsive genes in the mammary gland (Supplemental Figure 2C). Therefore, treatment with E2, despite eliciting ductal growth in both strains, is associated with distinct transcriptional signatures in B6 versus C3H mice.

Tissue-specific transcriptional responses to E2

Although it was not the primary objective of our experiment, our approach allowed for the identification of tissue-specific transcriptional responses to E2. Perhaps not surprisingly, the response of the uterus at 72 hours post treatment was more robust than the mammary gland, with 1,568 E2-regulated genes (Supplemental Figure 1B). In addition, despite the existence of common E2-responsive genes across the two tissues, there was no correlation in the direction of differential expression induced by E2 (Supplemental Figure 2C).

Discussion

The results of this experiment reveal that the E2-induced increase in ductal growth and side branching in female mice is genetically controlled and is associated with differences in mammary epithelial cell proliferation and apoptosis. Strain differences in the response of mammary tissue to E2 were reported long ago (12, 14, 19). In addition, genetic control of mammary development (34), response to hormones (25) and ductal morphology (35, 36) has been previously observed. Blair (14) observed marked variation in mammary alveolar development induced by treatment with E2 and progesterone in several strains of male mice including B6 and C3H. In agreement with our observation that there are distinctions in the response of mammary tissue to E2 in C3H versus B6 mice, Singh et al (19) reported that relative to C3H mice, B6 mice required longer hormonal priming in vivo in order for mammary tissue to respond to hormones in vitro. To our knowledge, ours is the first report to describe genetic control of ductal morphology and E2-induced ductal growth in B6 versus C3H mice. The factors underlying strain-specific mammary responsiveness to E2 are unclear; however, it has been suggested that interactions between the tissue and the host environment dictate hormone responsiveness (35, 36).

It is possible that the timing of tissue sampling in the current experiment was a factor and that the two strains were simply at different stages of development at the time of OVX. According to the Mouse Phenome Database (http://phenome.jax.org), the onset of puberty is 5 days earlier in C3H versus B6 mice (30 vs 35 days of age). Although the mice were OVX by 28 days of age, it is possible that the C3H mice were simply developmentally ahead of B6 mice and poised for a greater increase in mammary ductal growth in response to E2. In this scenario, however, we would have expected the uterine response of C3H mice to be greater than that of B6, and we observed the opposite (15). We would also expect that at later time points, mammary ductal length of B6 mice would reach that of C3H mice; however, our preliminary observations at later time points (6 and 15 days after E2 treatment) show that the differences in uterine weight and mammary ductal length are sustained (data not shown).

In agreement with previous reports on other strains of mice (12, 14), we observed that the uterine response to E2 was negatively correlated with the E2-induced increase in mammary ductal length. Similar inverse relationships in E2 sensitivity have been observed in other species. For example, the ACI rat is susceptible to E2-induced mammary and pituitary tumors, but it is resistant to E2-induced uterine infection (18, 37). Similarly, tissue-specific responses to the selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen have been observed in humans. Although tamoxifen inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation, it can also increase the risk of uterine cancer by promoting endometrial cell proliferation (38). Interestingly, we observed a positive relationship between the uterotropic response and mammary ductal side branching. Although the functional implications of this relationship are unclear, it is something that warrants further investigation because genetically-controlled differences in the effect of E2 on mammary morphology could potentially influence both the function of the mammary gland and susceptibility to disease. It is plausible that the E2-induced signaling cascades responsible for the uterotropic response are the same ones responsible for E2-induced mammary ductal side branching, but are distinct from those associated with E2-induced mammary ductal growth. The existence of such shared or distinct signaling mechanisms, however, remains to be established.

We previously observed that coincident with an increase in uterine epithelial cell apoptosis, E2 failed to induce expression of the apoptosis inhibitor Naip1 (Birc1a) in C3H mice (17). In the current experiment, mammary expression of Naip1 was not different between the strains (P > .95; microarray data); however, expression of mRNA for caspase-9 was much higher in B6 than C3H after treatment with E2 (Fold change = 14.4; P < .0001). Because caspase-9 is known to be associated with remodeling of the mammary gland during late pregnancy and early lactation in ruminants (39) and is involved in the antiapoptotic effects of E2 in breast cancer cell lines (40), it is possible that it is also involved in the genetic control of E2-induced mammary ductal growth and the decreased ductal length in B6 relative to C3H mice. In addition to an increase in mammary epithelial cell apoptosis, we also observed that mammary epithelial cell proliferation was increased in E2-treated B6 mice compared with C3H. Therefore, E2-treated B6 mice appear to be undergoing more extensive mammary remodeling or mammary epithelial cell turnover, and this may be the reason for the differences in mammary ductal morphology because mammary gland morphogenesis involves both cell proliferation and apoptosis (4). Interestingly, our microarray results revealed that mammary expression Sox5 mRNA was also increased in E2-treated B6 mice compared with C3H (Fold change = 2.5; P < .001). Previously, researchers have reported that expression of Sox5 is induced by E2 and that Sox5 is involved in a signaling cascade that may regulate mammary ductal branching morphogenesis and breast cancer cell growth (41). Therefore, it is possible that the differential expression of Sox5 in E2-treated B6 versus C3H mice is associated with the differences in mammary ductal side branching and morphology.

The Runx-related family of transcription factors includes at least three transcriptional regulators known to be involved in several cellular processes including cell proliferation and differentiation (42), and a role for Runx1 has been suggested in the development of endometrial cancer (43, 44). As mentioned previously, we identified Runx1 as a positional candidate on chromosome 16 that epistatically interacts with other QTL controlling uterine responsiveness to E2 (15, 16). In addition, we previously reported that uterine expression of Runx1 mRNA was increased 2 hours after E2 treatment, and uterine expression of RUNX1 was greater in B6 mice compared with C3H (17). It has been proposed that RUNX1 is a potentiator of E2-induced nonclassical ESR1 signaling (independent of estrogen-response elements) in the uterus by acting as a tethering factor (45). Interestingly, however, the reverse has been observed for E2-induced cellular proliferation in the mammary gland, where Runx1 has been proposed to be an antagonist of E2 and a tumor suppressor gene (46). Because our observations support a positive relationship between RUNX1 expression and E2-induced mammary ductal growth, and a negative relationship between RUNX1 expression and E2-induced ductal side branching, the role of Runx1 during mammary ductal growth remains unclear. Confirmation or exclusion of Runx1 as the gene controlling this response, or a shared gene controlling uterine and mammary gland responsiveness to E2, will require a physical mapping based forward genetic approach using congenic strains of mice.

Microarray analysis of mammary tissue 72 hours after treatment with E2 revealed the existence of some common, and many distinct, E2 responsive genes in each strain. Many of these genes were previously associated with mammary ductal growth at 48 hours after treatment with E2 (33). Previously, an E2-specific model of mammary ductal growth was associated with changes in the expression of genes known to be regulated by transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (33), which is known to play a critical role in mammary development and ductal morphology (4). To further understand the genes underlying the differences in E2-induced ductal morphology between strains, we determined the number of E2-regulated TGF-β superfamily member genes (33) that exhibited strain-specific E2-responsiveness in the current experiment. In B6 mice, 61 (30%) TGF-β superfamily member genes were responsive to E2 whereas 45 (50%) were responsive to E2 in C3H mice. Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis was used to predict the activation state of regulatory molecules based on these two distinct sets of responsive genes (Supplemental Table 2). Interestingly, there was no overlap in the regulatory molecules predicted to be activated or inhibited by E2 in each of the strains, however, several could potentially be involved in differences in mammary ductal growth and side branching. For example, signal transducer and activation of transcription-3, which is known to be associated with mammary involution and remodeling (47), was activated in B6 mice (P < .001; Supplemental Table 2). This is consistent with our observation that mammary epithelial cell apoptosis was greater in B6 mice. In contrast, epidermal growth factor, which is known to be a promoter of mammary ductal growth (48), was selectively activated in C3H mice (P < .001; Supplemental Table 2), consistent with increased E2-induced ductal length relative to B6. Consistent with our observation of increased mammary epithelial cell proliferation and ductal side branching in B6 relative to C3H mice, TGFβ-3 was selectively activated in B6 mice (P < .001; Supplemental Table 2), and this growth factor has a known role in mammary ductal branching morphogenesis (49). Based on these results, it appears that the differences in the response of the mammary gland to E2 in each strain are not the result of differences in the activation or inhibition of a common set of regulatory molecules. Rather, our findings suggest that E2 elicited the activation or inhibition of strain-specific regulatory molecules that might contribute to the observed differences in mammary ductal length and side branching between the strains. Importantly, our microarray analysis was performed using RNA extracted from mammary tissue, composed of various cell types. Therefore, it was impossible to distinguish between stromal versus epithelial-derived changes in mammary gene expression. Naylor et al (36) suggested that stromal factors underlie strain differences in mammary ductal morphology. Future work is needed to distinguish between stromal- and epithelial-specific genes that are differentially responsive to E2 across different strains of mice.

To our knowledge, there is only one other report comparing E2-regulated gene expression in uterus versus mammary gland (50). Suzuki et al (50) conducted microarray experiments at 6 and 24 hours after treatment with E2 and reported that no genes were differentially expressed in the mammary gland, despite clear and marked transcriptional responses in uterus and vagina. The lack of effect of E2 on mammary gene expression in their experiment might have been due to the early timing of tissue collection and (or) to the lower dose of E2 used (5 μg/kg BW). Our observations are consistent with theirs, such that at 72 hours after treatment with E2, the transcriptional response of the uterus was much more striking than that of the mammary gland. Others have observed robust transcriptional responses as early as 2 days after treatment (33, 51), however, in those studies, E2 was administered at twice the dose of that used in the current study (51), or as a slow-release pellet (33). In another study (52), a transcriptional response of the mammary gland was observed in as little as 3 hours, despite a lower dose than the one used in the current study (0.05 μg/mouse). Differences in E2 dose, strain of mouse studied, and array platform could all contribute to differences observed in the timing and magnitude of the transcriptional response, and the genes identified.

The results of this experiment have shown genetic control of both the transcriptional and cellular response of the mouse mammary gland to E2. Although we investigated only two genetic backgrounds, previous reports have indicated genetic regulation in the response of uterus (11, 12), vagina (12, 13), mammary gland (12), and bone (53, 54) to E2 across several strains of mice. Therefore, genetics clearly plays a role in phenotypic variation observed in response to natural, synthetic, and environmental estrogens (27, 55, 56). In addition, our findings lay the groundwork for important experiments that could provide insight into mechanisms underlying phenotypic variation in other highly relevant E2-regulated responses in humans including bone loss in postmenopausal women (57, 58), premature ovarian failure (59), fertility (55, 60), and libido (55), success rate of fertility treatments (56, 61) and sensitivity to environmental endocrine disrupters (27). Future work will be aimed at positionally cloning the genes underlying the QTL controlling mammary responsiveness to E2 and determining their functional role in modulating tissue sensitivity to E2 across various physiological states and genetic backgrounds. Such analyses are central to understanding inheritance patterns of disease susceptibility and providing insight into how individual genetic variation influences responses to treatment of E2-dependent diseases and sensitivity to hormonal agents and therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Russell Hovey for his helpful discussion of the data, Erin Osmanski for her assistance with animal husbandry and tissue collection, Jean Lin for her assistance with the microarray analysis of mammary tissue samples at the Methodist Hospital Research Institute core facility, and the UVM Histology lab for embedding uterine samples. The staff at the Microscopy Imaging Center at the University of Vermont, funded in part by the National Center for Research Resources (1S10RR019246), performed staining and imaging of CC3, ESR1, Ki-67, and RUNX1.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences project number Z01ES70065 to S.C.H and National Institutes of Health Research project numbers R01NS36526, R01NS061014, R01NS060901, R01NS069628, and R01AI41747 to C.T.. C.Y.L. is a member of the Center for Nuclear Receptors and Cell Signaling at the University of Houston supported by the State of Texas Emerging Technologies Fund (grant number 300-9-1958).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- CC3

- cleaved caspase-3

- ESR1

- estrogen receptor-α

- MMTV

- mouse mammary tumor virus

- OVX

- ovariectomized

- QTL

- quantitative trait loci

- RUNX1

- runt-related transcription factor 1

- TGF

- transforming growth factor.

References

- 1. Prossnitz ER, Maggiolini M. Mechanisms of estrogen signaling and gene expression via GPR30. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;308:32–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dutertre M, Smith CL. Molecular mechanisms of selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) action. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:431–437 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark JH, Mani SK. 1994. Actions of ovarian steroid hormones. In: Knobil E, Neill J, eds. The Physiology of Reproduction. New York: Raven Press; 1011–1059 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hovey RC, Trott JF. Morphogenesis of mammary gland development. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;554:219–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Silberstein GB. Postnatal mammary gland morphogenesis. Microsc Res Tech. 20011;52:155–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Korach KS, Couse JF, Curtis SW, et al. Estrogen receptor gene disruption: molecular characterization and experimental and clinical phenotypes. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1996;51:159–186; discussion 186–158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pike MC, Spicer DV, Dahmoush L, Press MF. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:17–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bernstein L, Ross RK. Endogenous hormones and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:48–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hellberg D. Sex steroids and cervical cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:3045–3054 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Y, van der Zee M, Fodde R, Blok LJ. Wnt/Beta-catenin and sex hormone signaling in endometrial homeostasis and cancer. Oncotarget. 2010;1:674–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Drasher ML. Strain differences in the response of the mouse uterus to estrogens. J Hered. 1952;46:190–192 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Silberberg M, Silberberg R. Susceptibility to estrogen of breast, vagina, and endometrium of various strains of mice. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1951;76:161–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trentin JJ. Vaginal sensitivity to estrogen as related to mammary tumor incidence in mice. Cancer Res. 1950;10:580–583 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blair SM, Blair PB, Daane TA. Differences in the mammary response to estrone and progesterone in castrate male mice of several strains and hybrids. Endocrinology. 1951;61:643–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Griffith JS, Jensen SM, Lunceford JK, et al. Evidence for the genetic control of estradiol-regulated responses. Implications for variation in normal and pathological hormone-dependent phenotypes. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:2223–2230 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roper RJ, Griffith JS, Lyttle CR, et al. Interacting quantitative trait loci control phenotypic variation in murine estradiol-regulated responses. Endocrinology. 1999;140:556–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wall EH, Hewitt SC, Liu L, et al. Genetic control of estrogen-regulated transcriptional and cellular responses in mouse uterus. FASEB J. 2013;27:1874–1886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schaffer BS, Lachel CM, Pennington KL, et al. Genetic bases of estrogen-induced tumorigenesis in the rat: mapping of loci controlling susceptibility to mammary cancer in a Brown Norway x ACI intercross. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7793–7800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh DV, DeOme KB, Bern HA. Strain differences in response of the mouse mammary gland to hormones in vitro. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1970;45:657–675 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shimkin MB, Wyman RS. Mammary tumors in male mice implanted with estrogen-cholesterol pellets. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1946;7:71–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shimkin MB, Wyman RS. Effect of adrenalectomy and ovariectomy on mammary carcinogenesis in strain C3H mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1945;6:187–189 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shimkin MB, Andervont HB. The effect of foster nursing on the response of mice to estrogens. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1941;1:599–605 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee AE. Proliferative responses of mouse mammary glands to 17 beta-estradiol and progesterone and modification by mouse mammary tumor virus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983;71:1265–1269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mixner JP, Turner CW. Strain differences in response of mice to mammary gland stimulating hormones. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1957;95:87–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aupperlee MD, Drolet AA, Durairaj S, Wang W, Schwartz RC, Haslam SZ. Strain-specific differences in the mechanisms of progesterone regulation of murine mammary gland development. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1485–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Montero Girard G, Vanzulli SI, Cerliani JP, et al. Association of estrogen receptor-alpha and progesterone receptor A expression with hormonal mammary carcinogenesis: role of the host microenvironment. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Spearow JL, Doemeny P, Sera R, Leffler R, Barkley M. Genetic variation in susceptibility to endocrine disruption by estrogen in mice. Science. 1999;285:1259–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pashayan N, Duffy SW, Chowdhury S, et al. Polygenic susceptibility to prostate and breast cancer: implications for personalised screening. Br J Cancer. 2011;104:1656–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pharoah PD, Antoniou A, Bobrow M, Zimmern RL, Easton DF, Ponder BA. Polygenic susceptibility to breast cancer and implications for prevention. Nat Genet. 2002;31:33–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ghoussaini M, Pharoah PD. Polygenic susceptibility to breast cancer: current state-of-the-art. Future Oncol. 2009;5:689–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hewitt SC, Bocchinfuso WP, Zhai J, et al. Lack of ductal development in the absence of functional estrogen receptor alpha delays mammary tumor formation induced by transgenic expression of ErbB2/neu. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2798–2805 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. National Institute of Health. 1999. Biology of the Mammary Gland. http://mammary.nih.gov/tools/histological/Histology/index.html#a1

- 33. Deroo BJ, Hewitt SC, Collins JB, Grissom SF, Hamilton KJ, Korach KS. Profile of estrogen-responsive genes in an estrogen-specific mammary gland outgrowth model. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:733–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gardner WU, Strong LC. The normal development of the mammary glands of virgin female mice of ten strains varying in susceptibility to spontaneous neoplasms. Am J Cancer. 1935;25:282–290 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yant J, Gusterson B, Kamalati T. Induction of strain-specific mouse mammary gland ductal architecture. The Breast. 1998;7:269–272 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naylor MJ, Ormandy CJ. Mouse strain-specific patterns of mammary epithelial ductal side branching are elicited by stromal factors. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:100–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gould KA, Pandey J, Lachel CM, et al. Genetic mapping of Eutr1, a locus controlling E2-induced pyometritis in the Brown Norway rat, to RNO5. Mamm Genome. 2005;16:854–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jordan VC, Gottardis MM, Satyaswaroop PG. Tamoxifen-stimulated growth of human endometrial carcinoma. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;622:439–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Norgaard JV, Theil PK, Sorensen MT, Sejrsen K. Cellular mechanisms in regulating mammary cell turnover during lactation and dry period in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci. 2008;91:2319–2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gregoraszczuk E, Ptak A. Involvement of caspase-9 but not caspase-8 in the anti-apoptotic effects of estradiol and 4-OH-Estradiol in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Endocr Regul. 2011;45:3–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stevens TA, Meech R. BARX2 and estrogen receptor-alpha (ESR1) coordinately regulate the production of alternatively spliced ESR1 isoforms and control breast cancer cell growth and invasion. Oncogene. 2006;25:5426–5435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ito Y. RUNX genes in development and cancer: regulation of viral gene expression and the discovery of RUNX family genes. Adv Cancer Res. 2008;99:33–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Doll A, Gonzalez M, Abal M, et al. An orthotopic endometrial cancer mouse model demonstrates a role for RUNX1 in distant metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:257–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Planaguma J, Abal M, Gil-Moreno A, et al. Up-regulation of ERM/ETV5 correlates with the degree of myometrial infiltration in endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. J Pathol. 2005;207:422–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stender JD, Kim K, Charn TH, et al. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor alpha DNA binding and tethering mechanisms identifies Runx1 as a novel tethering factor in receptor-mediated transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3943–3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chimge NO, Frenkel B. The RUNX family in breast cancer: relationships with estrogen signaling. Oncogene. 2013;32:2121–2130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Watson CJ, Neoh K. The Stat family of transcription factors have diverse roles in mammary gland development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McBryan J, Howlin J, Napoletano S, Martin F. Amphiregulin: role in mammary gland development and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 2008;13:159–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pollard JW. Tumour-stromal interactions. Transforming growth factor-beta isoforms and hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor in mammary gland ductal morphogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2001;3:230–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Suzuki A, Urushitani H, Watanabe H, et al. Comparison of estrogen responsive genes in the mouse uterus, vagina and mammary gland. J Vet Med Sci. 2007;69:725–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lu S, Becker KA, Hagen MJ, et al. Transcriptional responses to estrogen and progesterone in mammary gland identify networks regulating p53 activity. Endocrinology. 2008;49:4809–4820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Calvo E, Luu-The V, Belleau P, Martel C, Labrie F. Specific transcriptional response of four blockers of estrogen receptors on estradiol-modulated genes in the mouse mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134:625–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bouxsein ML, Myers KS, Shultz KL, Donahue LR, Rosen CJ, Beamer WG. Ovariectomy-induced bone loss varies among inbred strains of mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1085–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li CY, Schaffler MB, Wolde-Semait HT, Hernandez CJ, Jepsen KJ. Genetic background influences cortical bone response to ovariectomy. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:2150–2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Simpson ER, Jones ME. Of mice and men: the many guises of estrogens. Ernst Schering Found Symp Proc. 2006;1:45–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Altmae S, Hovatta O, Stavreus-Evers A, Salumets A. Genetic predictors of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation: where do we stand today? Hum Reprod. Update. 2011;17:813–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ., 3rd A unitary model for involutional osteoporosis: estrogen deficiency causes both type I and type II osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and contributes to bone loss in aging men. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:763–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Richards JB, Zheng HF, Spector TD. Genetics of osteoporosis from genome-wide association studies: advances and challenges. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:576–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Beck-Peccoz P, Persani L. Premature ovarian failure. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Krausz C, Giachini C. Genetic risk factors in male infertility. Arch Androl. 2007;53:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Loutradis D, Theofanakis C, Anagnostou E, Mavrogianni D, Partsinevelos GA. Genetic profile of SNP(s) and ovulation induction. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13:417–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]