Abstract

Rationale: Corticosteroids are prescribed commonly for patients with septic shock, but their use remains controversial and concerns remain regarding side effects.

Objectives: To determine the effect of adjunctive corticosteroids on the genomic response of pediatric septic shock.

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed an existing transcriptomic database of pediatric septic shock. Subjects receiving any formulation of systemic corticosteroids at the time of blood draw for microarray analysis were classified in the septic shock corticosteroid group. We compared normal control subjects (n = 52), a septic shock no corticosteroid group (n = 110), and a septic shock corticosteroid group (n = 70) using analysis of variance. Genes differentially regulated between the no corticosteroid group and the corticosteroid group were analyzed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

Measurements and Main Results: The two study groups did not differ with respect to illness severity, organ failure burden, mortality, or mortality risk. There were 319 gene probes differentially regulated between the no corticosteroid group and the corticosteroid group. These genes corresponded predominately to adaptive immunity–related signaling pathways, and were down-regulated relative to control subjects. Notably, the degree of down-regulation was significantly greater in the corticosteroid group, compared with the no corticosteroid group. A similar pattern was observed for genes corresponding to the glucocorticoid receptor signaling pathway.

Conclusions: Administration of corticosteroids in pediatric septic shock is associated with additional repression of genes corresponding to adaptive immunity. These data should be taken into account when considering the benefit to risk ratio of adjunctive corticosteroids for septic shock.

Keywords: sepsis, corticosteroids, adaptive immunity, gene expression, microarray

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

There is variable equipoise surrounding the use of adjunctive corticosteroids in septic shock because of the potential side effects, including immune suppression. The effects of corticosteroids on global gene expression in septic shock are not well described.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Using a transcriptomics approach, we have demonstrated that the use of corticosteroids in children with septic shock is associated with repression of gene programs corresponding to the adaptive immune system. These data should be taken into consideration when administering corticosteroids to children with septic shock.

The most recent Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines recommend that adjunctive corticosteroids should be considered for patients with septic shock who are poorly responsive to fluid resuscitation and vasoactive-inotropic therapy (1). Despite this recommendation, there is tremendous practice variability surrounding the use of adjunctive corticosteroids for septic shock in both adult and pediatric critical care medicine (2, 3). This variation reflects variable physician equipoise surrounding the efficacy of adjunctive corticosteroids for septic shock, with recent metaanalyses concluding that corticosteroids seem to improve hemodynamics, but have no clear survival benefit (4, 5). Equipoise is further driven by the known side effects of corticosteroids, including hyperglycemia and myopathy associated with lean muscle catabolism, poor wound healing, and immune suppression (4, 6).

Over the last decade, we have generated an extensive genome-wide expression database of children with septic shock drawn from multiple centers in the United States (7). The database has leveraged the discovery potential of transcriptomics to identify novel therapeutic targets (8, 9), candidate diagnostic (10, 11) and stratification biomarkers (12–16), and gene expression–based subclasses of pediatric septic shock (17–19). Here we retrospectively analyze this database to determine if the use of adjunctive corticosteroids influences the early genomic response of children with septic shock.

Methods

Patients and Data Collection

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of each participating institution (n = 11). Children less than or equal to 10 years of age admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and meeting pediatric-specific criteria for septic shock were eligible for enrollment (20). Age-matched control subjects were recruited from the ambulatory departments of participating institutions using published inclusion and exclusion criteria (8). All patients and control subjects were previously reported in microarray-based studies addressing hypotheses entirely different from that of the current study (8, 17–19, 21–24). All microarray data have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (Accession numbers GSE26440 and GSE26378).

After informed consent from parents or legal guardians, blood samples were obtained within 24 hours of initial presentation to the PICU with septic shock. Clinical and laboratory data were collected daily while in the PICU and stored using a Web-based database. Organ failure was defined using pediatric-specific criteria and tracked up to the first 7 days of PICU admission (20). Mortality was tracked for 28 days after enrollment. Illness severity was measured using PRISM scores (25) and septic shock–related mortality probability at study entry was estimated using the Pediatric Sepsis Biomarker Risk Model (PERSEVERE) (12, 15).

We surveyed the medication fields of the clinical database to determine if the study subjects received systemic corticosteroids. Subjects that were receiving any formulation of systemic corticosteroids at the time when blood was drawn for microarray analysis were classified in the septic shock corticosteroid group. All other subjects were classified in the septic shock no corticosteroid group. We were unable to determine dosages or the clinical indications for corticosteroids in all subjects consistently.

RNA Extraction and Microarray Hybridization

Total RNA was isolated from whole blood using the PaxGene Blood RNA System (PreAnalytiX; Qiagen/Becton Dickson, Valencia, CA). Microarray hybridization was performed as previously described using the Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChip (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) (8, 17, 21–23).

Data Analysis

Analyses were performed using one patient sample per chip. Image files were captured using an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000. Raw data files (.CEL) were subsequently preprocessed using Robust Multiple-Array Average normalization and GeneSpring GX 7.3 software (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). All signal intensity–based data were used after Robust Multiple-Array Average normalization, which specifically suppresses all but significant variation among lower-intensity probe sets (26). All chips representing patient samples were then normalized to the respective median values of control subjects.

Differences in mRNA abundance between the study groups were determined using analysis of variance (ANOVA). For clarity, further details regarding microarray data analysis and gene list generation are provided in the Results section. Gene lists of differentially expressed genes were analyzed using the Ingenuity Pathways Analysis application (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA), which provides a tool for discovery of signaling pathways and gene networks within the uploaded gene lists as previously described (21, 24). Adjunct analyses of gene lists were conducted using the ToppGene application (27).

Gene expression mosaics representing the expression patterns of differentially regulated genes were generated using the Gene Expression Dynamics Inspector (GEDI) (18, 19, 28, 29). The signature graphical outputs of GEDI are expression mosaics that give microarray data a “face” that is intuitively recognizable by human pattern recognition. The algorithm for creating the mosaics is a self-organizing map. Additional technical details regarding GEDI can be found at http://www.childrenshospital.org/research/ingber/GEDI/gedihome.htm.

Ordinal and continuous clinical variables not normally distributed were analyzed by ANOVA on ranks. Dichotomous clinical variables were analyzed using a chi-square test (SigmaStat Software; Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA).

Results

Table 1 provides clinical and demographic data for the two study groups. A greater proportion of subjects receiving corticosteroids had a gram-negative organism isolated as the cause of septic shock, compared with subjects not receiving corticosteroids. No other differences were noted between the two groups.

Table 1:

Clinical and Demographic Data for the Study Subjects with Septic Shock*

| No Corticosteroid (n = 110) | Corticosteroid (n = 70) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 2.1 (0.8–6.5) | 2.8 (1.2–6.0) | 0.537 |

| Number of males (%) | 67 (61) | 42 (60) | 0.903 |

| Number of deaths (%) | 18 (16.4) | 11 (15.7) | 0.908 |

| PRISM score | 14 (9–21) | 16 (11–22) | 0.179 |

| PERSEVERE-based mortality probability (95% confidence interval) | 0.11 (0.08–0.14) | 0.14 (0.09–0.18) | 0.365 |

| Maximum number of organ failures | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.241 |

| Neutrophil count × 103/μl | 9.8 (3.2–13.1) | 7.7 (3.3–16.8) | 0.594 |

| Lymphocyte count × 103/μl | 1.8 (1.0–3.9) | 1.6 (0.6–3.0) | 0.173 |

| Monocyte count × 103/μl | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | 0.5 (0.2–1.3) | 0.953 |

| Number with gram-positive bacteria (%) | 34 (31) | 18 (26) | 0.453 |

| Number with gram-negative bacteria (%) | 16 (15) | 20 (29) | 0.022 |

| Number with other organism (%) | 10 (9) | 4 (6) | 0.410 |

| Number with negative cultures (%) | 50 (45) | 28 (40) | 0.472 |

| Number with comorbidity (%) | 44 (40) | 32 (46) | 0.449 |

All data are shown as medians with interquartile ranges unless otherwise noted.

To determine which genes were differentially regulated between the two study groups, we conducted a three-group ANOVA (normal control subjects [n = 52], septic shock no corticosteroid group [n = 110], and septic shock corticosteroid group [n = 70]) starting with all gene probes on the array (>80,000) and corrections for multiple comparisons (Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate, 5%). This initial statistical test yielded 21,913 gene probes differentially regulated among the three groups. We subsequently conducted a post hoc test (Student–Newman-Keuls) to identify the gene probes differentially regulated between the no corticosteroid group and corticosteroid group (319 gene probes; see Table E1 in the online supplement).

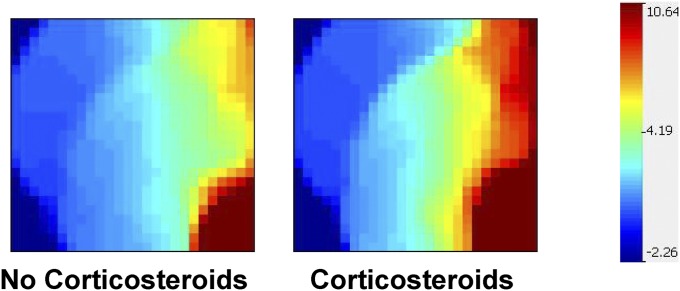

We next uploaded the expression values of these 319 gene probes to the GEDI platform and constructed gene expression mosaics for the two study groups. Figure 1 shows the respective gene expression mosaics for the no corticosteroid group and corticosteroid group. Each gene expression mosaic depicts the same 319 gene probes at the identical coordinates. The degree of red intensity correlates with increased gene expression, whereas the degree of blue intensity correlates with decreased gene expression. Figure 1 provides a global representation of how the 319 gene probes were differentially regulated between the two groups.

Figure 1.

Gene expression mosaics for 319 gene probes differentially regulated between the septic shock no corticosteroid group and the septic shock corticosteroid group. Each gene expression mosaic depicts that same 319 gene probes at the identical coordinates. The degree of red intensity correlates with increased gene expression, whereas the degree of blue intensity correlates with decreased gene expression.

To derive more specific biologic information from the 319 differentially regulated gene probes, we uploaded the gene list to the IPA platform and focused the data output on enrichment for genes corresponding to signaling pathways and gene networks. Table 2 provides the top 10 (based on P values) signaling pathways represented by the 319 gene probes. Eight of the top 10 signaling pathways corresponded to the adaptive immune system, whereas the remaining two signaling pathways corresponded to glucocorticoid receptor signaling and inducible nitric oxide synthase signaling, respectively.

Table 2:

Top 10 Signaling Pathways Represented by the 319 Differentially Regulated Gene Probes

| Signaling Pathway | Number of Genes | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| T-cell receptor signaling | 11 | 1.9 × 10−8 |

| iCOS-iCOSL signaling in T-helper cells | 10 | 2.9 × 10−7 |

| Role of NFAT in regulation of the immune response | 12 | 5.7 × 10−7 |

| CD28 signaling in T helper cells | 10 | 7.2 × 10−7 |

| PKCθ signaling in T lymphocytes | 9 | 6.3 × 10−6 |

| CCR5 signaling in macrophages | 7 | 1.0 × 10−5 |

| CTLA4 signaling in cytotoxic T lymphocytes | 7 | 6.3 × 10−5 |

| Glucocorticoid receptor signaling | 12 | 7.3 × 10−5 |

| iNOS signaling | 5 | 1.7 × 10−4 |

| Nur77 signaling in T lymphocytes | 5 | 2.1 × 10−4 |

Definition of abbreviations: CCR = chemokine receptor; CTLA = cytotoxic T- lymphocyte antigen; iCOS = inducible T-cell costimulator (CD278); iNOS = inducible nitric oxide synthetase; NFAT = nuclear factor of activated T cells; PKC = protein kinase C.

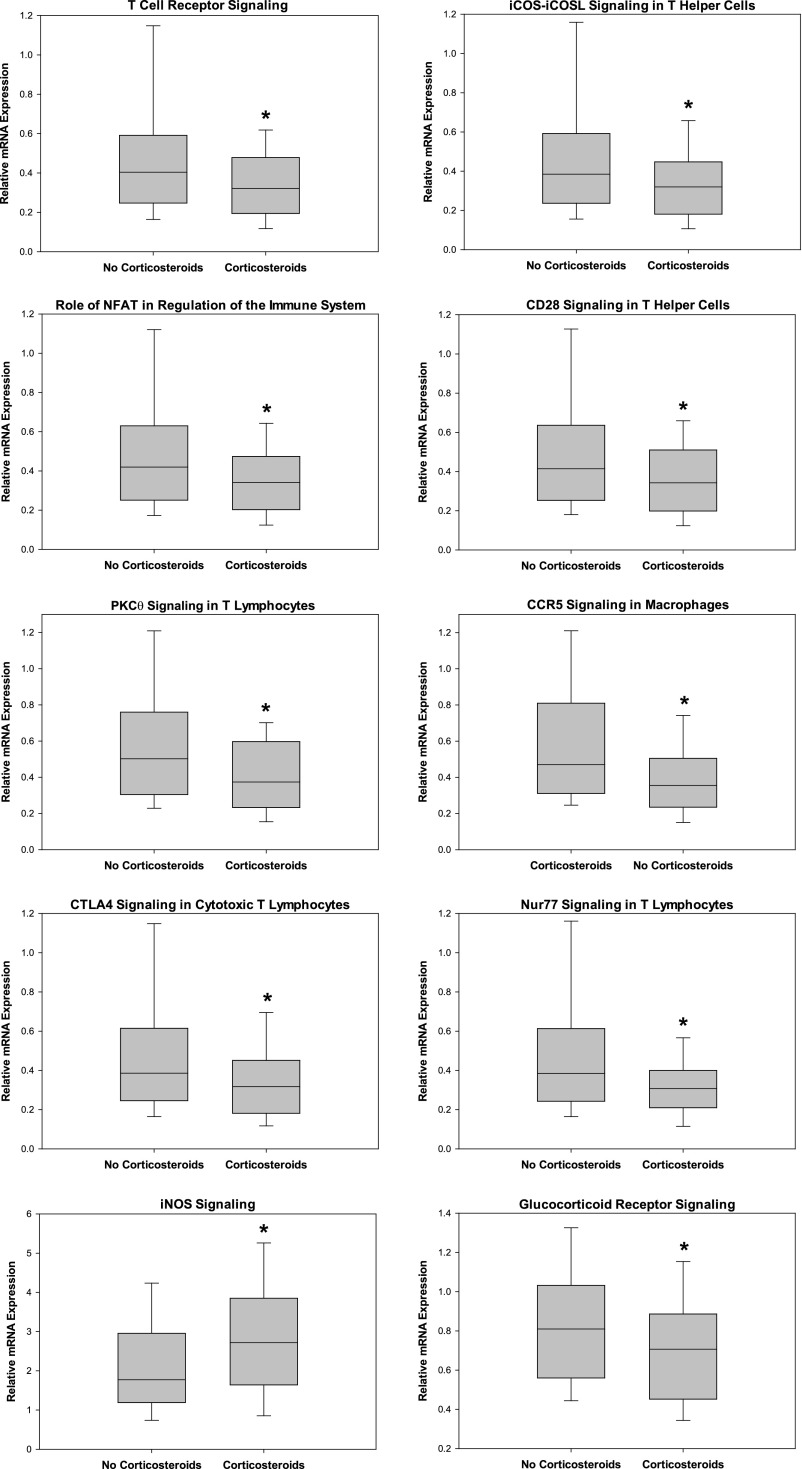

We next extracted the normalized expression values for each gene corresponding to the signaling pathways shown in Table 2, and calculated the respective median relative gene expression values for the two study groups. Accordingly, Figure 2 shows that among the eight signaling pathways corresponding to the adaptive immune system, the median expression values of the respective genes were less than one, meaning that the genes were down-regulated relative to normal control subjects. Notably, the degree of down-regulation was significantly greater in the corticosteroid group compared with the no corticosteroid group. The genes corresponding to glucocorticoid receptor signaling pathway demonstrated a similar pattern of down-regulation. In contrast, the genes corresponding to the inducible nitric oxide synthase signaling pathway were up-regulated relative to control subjects (median relative expression values >1), and the degree of up-regulation was greater in the corticosteroid group compared with the no corticosteroid group.

Figure 2.

Box-and-whisker plots depicting the relative mRNA expression values for genes corresponding to the respective signaling pathways shown in Table 2. *P < 0.05 versus the septic shock no corticosteroid group. CCR = chemokine receptor; CTLA = cytotoxic T- lymphocyte antigen; iCOS = inducible T-cell costimulator (CD278); iNOS = inducible nitric oxide synthetase; NFAT = nuclear factor of activated T cells; PKC = protein kinase C.

To corroborate the functional annotations derived from the IPA-based analysis, we uploaded the 319 gene list to the ToppGene application as an alternative discovery platform. According to the ToppGene application, the top biologic processes represented by the 319 gene probes included (P value) cell activation (1.3 × 10−18), leukocyte activation (2.0 × 10−18), lymphocyte activation (1.1 × 10−15), immune response (4.5 × 10−14), and T-cell activation (1.9 × 10−12).

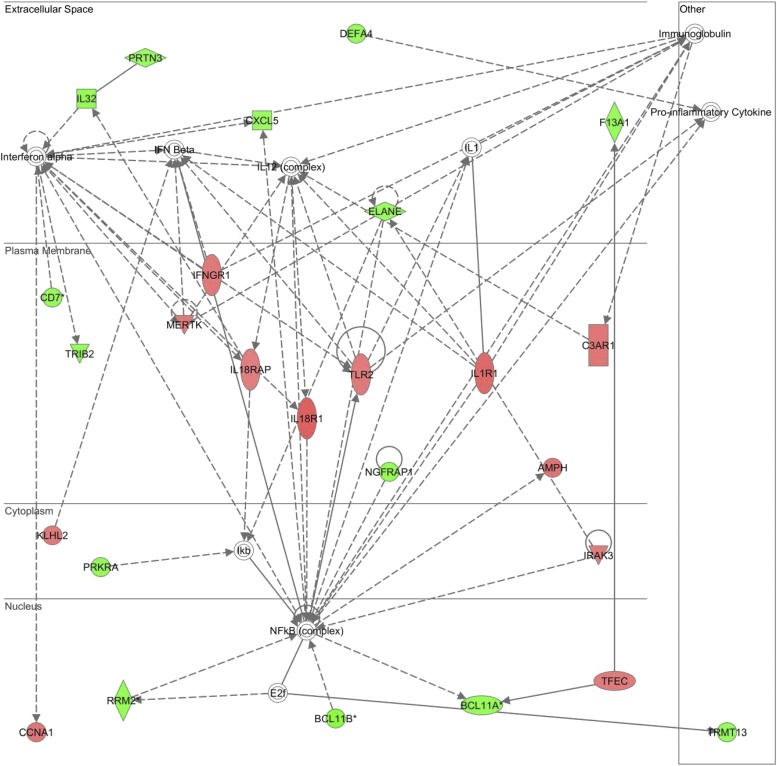

Figure 3 displays the top scoring IPA gene network represented by the 319 differentially gene probes. The gene network consists of genes up-regulated (red intensity) and down-regulated (green intensity) in the corticosteroid group, relative to the no corticosteroid group, and demonstrates the nuclear factor-κB and IL-1 receptor complexes as highly connected nodes in the nuclear and plasma membrane compartments, respectively. Cross-referencing the genes corresponding to the network nodes with the ToppGene database returned IL-1 receptor activity and cytokine receptor activity as the top molecular functions.

Figure 3.

Top scoring network represented by the 319 gene probes differentially regulated between the septic shock no corticosteroid group and the septic shock corticosteroid group. Red intensity indicates increased expression and green intensity indicates decreased expression in the corticosteroid group, relative to the no corticosteroid group. The genes corresponding to the respective nodes are provided in Table E2.

Because the corticosteroid group had a higher proportion of subjects with a gram-negative organism isolated, compared with the no corticosteroid group, we next tested the possibility that the causative organism confounded our results. We conducted an identical statistical analysis as that for the primary analysis, except that we compared normal control subjects (n = 52), subjects with a gram-positive organism (n = 52), and subjects with a gram-negative organism (n = 36). This analysis yielded 118 gene probes differentially regulated between the gram-positive group and the gram-negative group. Venn analysis demonstrated that only 19 gene probes were common between these 118 gene probes and the 319 gene probes differentially regulated between the no corticosteroid group and corticosteroid group. None of the 19 common gene probes contributed to the signaling pathways shown in Table 2.

Discussion

We have retrospectively analyzed a comprehensive genomic expression database of children with septic shock to compare gene expression between subjects who received corticosteroids as part of their therapeutic regimen with those who did not receive corticosteroids. Consistent with our previous studies (7) and current concepts regarding the pathobiology of septic shock (30), we found that pediatric septic shock is generally characterized by early repression of genes corresponding to the adaptive immune system. The primary new observation of the current study is that the use of corticosteroids is associated with an even greater degree of repression of these adaptive immunity–related genes, compared with subjects who do not receive corticosteroids.

The two study groups were well matched with respect to illness severity as measured by mortality, PRISM score, organ failure burden, and PERSEVERE-based mortality probability. Similarly, the two study groups were well matched with respect to leukocyte subset numbers. Thus, the observation that the use of corticosteroids was associated with greater repression of adaptive immunity–related genes is unlikely to reflect confounding by illness severity or differential white blood cell counts. Furthermore, the secondary analysis focused on subjects with gram-negative and gram-positive causes of septic shock indicates that our results are unlikely to reflect differences caused by the infecting organism.

The use of adjunctive corticosteroids for septic shock has a long history and remains a major controversy in critical care medicine (6). Initial strategies were based on an antiinflammatory paradigm and consequently used high doses of corticosteroids, but eventually fell out of favor because of no benefit and possible harm (31, 32). Contemporary strategies are based on addressing the concept of “critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency” with lower doses of corticosteroids, but this approach has yielded inconsistent results in randomized trials and the field has yet to reach consensus on the topic (33–36). Even with lower doses of corticosteroids, intended to replace a potential relative insufficiency of endogenous corticosteroids, concerns remain about the potential side effects of exogenous corticosteroids, including immune suppression (4, 6). Although our data cannot directly link the use of corticosteroids with immune suppression in pediatric septic shock, our data indirectly support these concerns in that the use of corticosteroids was associated with repression of adaptive immunity–related gene programs beyond what we have observed in our previous studies, and seemingly independent of illness severity, leukocyte subset numbers, and infecting pathogen class.

We also observed that the use of corticosteroids was associated with further repression of genes corresponding to the glucocorticoid receptor signaling pathway. This observation is consistent with the known biology of corticosteroids and thus provides an important level of credibility to the other observations. Finally, the use of corticosteroids was associated with a mixture of up- and down-regulated genes corresponding to a gene network involving IL-1 receptor activity and the nuclear factor-κB complex. The importance of these molecular functions to inflammation and immunity are well known, but the specific biologic implications of our observations, in the context of septic shock, are open to speculation.

We note the following limitations of our study. The study was retrospective and the use of steroids was not under protocol. Thus, it is likely that the doses and duration used across centers and the specific indications for their use varied widely among the contributing centers (2, 3). The gene expression data are limited to a single time point, early in the course of septic shock. Thus, it is unknown if the association between corticosteroids and repression of adaptive immunity–related genes persists beyond this early time point. Finally, the data are limited to mRNA expression data, and we have no functional data to corroborate a link between the use of corticosteroids and immune suppression in pediatric septic shock.

In conclusion, using a transcriptomics approach we have demonstrated that the use of corticosteroids in children with septic shock is associated with additional repression of gene programs corresponding to the adaptive immune system. This observation does not seem to be an artifact of illness severity, differential white blood cell counts, or the infecting pathogen class. These data should be taken into consideration when administering corticosteroids to children with septic shock and when designing future trials of adjunctive corticosteroids for pediatric septic shock.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants RC1HL100474, RO1GM064619, and RO1GM099773.

Author Contributions: H.R.W. conceived and developed the study, obtained funding for the study, conducted the analyses, and wrote the manuscript. N.Z.C., G.L.A., N.J.T., R.J.F., N.A., K.M., P.A.C., S.L.W., T.P.S., and M.T.B. enrolled subjects at the participating institutions, provided clinical data and biologic samples, and edited the manuscript. S.B. and E.B. maintained the clinical database and coordinated all interinstitutional research activity. K.H. maintained the biologic repository and processed all biologic samples. J.J.Z. conceived the study, took part in the analysis, and edited the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0171OC on March 20, 2014

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Douglas IS, Jaeschke R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menon K, McNally JD, Choong K, Ward RE, Lawson ML, Ramsay T, Wong HR. A survey of stated physician practices and beliefs on the use of steroids in pediatric fluid and/or vasoactive infusion-dependent shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:462–466. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31828a7287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntyre LA, Hébert PC, Fergusson D, Cook DJ, Aziz A Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. A survey of Canadian intensivists’ resuscitation practices in early septic shock. Crit Care. 2007;11:R74. doi: 10.1186/cc5962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel GP, Balk RA. Systemic steroids in severe sepsis and septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:133–139. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1897CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menon K, McNally D, Choong K, Sampson M. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of steroids in pediatric shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:474–480. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31828a8125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmerman JJ. A history of adjunctive glucocorticoid treatment for pediatric sepsis: moving beyond steroid pulp fiction toward evidence-based medicine. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:530–539. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000288710.11834.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong HR. Genome-wide expression profiling in pediatric septic shock. Pediatr Res. 2013;73:564–569. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong HR, Shanley TP, Sakthivel B, Cvijanovich N, Lin R, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Doctor A, Kalyanaraman M, Tofil NM, et al. Genomics of Pediatric SIRS/Septic Shock Investigators. Genome-level expression profiles in pediatric septic shock indicate a role for altered zinc homeostasis in poor outcome. Physiol Genomics. 2007;30:146–155. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00024.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solan PD, Dunsmore KE, Denenberg AG, Odoms K, Zingarelli B, Wong HR. A novel role for matrix metalloproteinase-8 in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:379–387. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232e404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Hall M, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Freishtat RJ, Anas N, Meyer K, Checchia PA, Lin R, et al. Interleukin-27 is a novel candidate diagnostic biomarker for bacterial infection in critically ill children. Crit Care. 2012;16:R213. doi: 10.1186/cc11847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong HR, Lindsell CJ, Lahni P, Hart KW, Gibot S. Interleukin 27 as a sepsis diagnostic biomarker in critically ill adults. Shock. 2013;40:382–386. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182a67632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong HR, Salisbury S, Xiao Q, Cvijanovich NZ, Hall M, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Freishtat RJ, Anas N, Meyer K, et al. The pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model. Crit Care. 2012;16:R174. doi: 10.1186/cc11652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong HR, Cvijanovich N, Wheeler DS, Bigham MT, Monaco M, Odoms K, Macias WL, Williams MD. Interleukin-8 as a stratification tool for interventional trials involving pediatric septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:276–282. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-131OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong HR, Lindsell CJ, Pettila V, Meyer NJ, Thair SA, Karlsson S, Russell JA, Fjell CD, Boyd JH, Ruokonen E, et al. A multibiomarker-based outcome risk stratification model for adult septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:781–789. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong HR, Weiss SL, Giuliano JS, Jr, Wainwright MS, Cvijanovich NZ, Thomas NJ, Allen GL, Anas N, Bigham MT, Hall M, et al. Testing the prognostic accuracy of the updated pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong HR, Weiss SL, Giuliano JS, Jr, Wainwright MS, Cvijanovich NZ, Thomas NJ, Allen GL, Anas N, Bigham MT, Hall M, et al. The temporal version of the pediatric sepsis biomarker risk model. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong HR, Cvijanovich N, Lin R, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Willson DF, Freishtat RJ, Anas N, Meyer K, Checchia PA, et al. Identification of pediatric septic shock subclasses based on genome-wide expression profiling. BMC Med. 2009;7:34. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong HR, Wheeler DS, Tegtmeyer K, Poynter SE, Kaplan JM, Chima RS, Stalets E, Basu RK, Doughty LA. Toward a clinically feasible gene expression-based subclassification strategy for septic shock: proof of concept. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1955–1961. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181eb924f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong HR, Cvijanovich NZ, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Freishtat RJ, Anas N, Meyer K, Checchia PA, Lin R, Shanley TP, et al. Validation of a gene expression-based subclassification strategy for pediatric septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2511–2517. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182257675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:2–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149131.72248.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shanley TP, Cvijanovich N, Lin R, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Doctor A, Kalyanaraman M, Tofil NM, Penfil S, Monaco M, et al. Genome-level longitudinal expression of signaling pathways and gene networks in pediatric septic shock. Mol Med. 2007;13:495–508. doi: 10.2119/2007-00065.Shanley. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cvijanovich N, Shanley TP, Lin R, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Checchia P, Anas N, Freishtat RJ, Monaco M, Odoms K, et al. Genomics of Pediatric SIRS/Septic Shock Investigators. Validating the genomic signature of pediatric septic shock. Physiol Genomics. 2008;34:127–134. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00025.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong HR, Cvijanovich N, Allen GL, Lin R, Anas N, Meyer K, Freishtat RJ, Monaco M, Odoms K, Sakthivel B, et al. Genomics of Pediatric SIRS/Septic Shock Investigators. Genomic expression profiling across the pediatric systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, and septic shock spectrum. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1558–1566. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819fcc08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wynn JL, Cvijanovich NZ, Allen GL, Thomas NJ, Freishtat RJ, Anas N, Meyer K, Checchia PA, Lin R, Shanley TP, et al. The influence of developmental age on the early transcriptomic response of children with septic shock. Mol Med. 2011;17:1146–1156. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollack MM, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE. The Pediatric Risk of Mortality III—Acute Physiology Score (PRISM III-APS): a method of assessing physiologic instability for pediatric intensive care unit patients. J Pediatr. 1997;131:575–581. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U, Speed TP. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Bardes EE, Aronow BJ, Jegga AG. ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W305–W311. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eichler GS, Huang S, Ingber DE. Gene Expression Dynamics Inspector (GEDI): for integrative analysis of expression profiles. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2321–2322. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Y, Eichler GS, Feng Y, Ingber DE, Huang S. Towards a holistic, yet gene-centered analysis of gene expression profiles: a case study of human lung cancers. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006. 2006:69141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:260–268. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70001-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Group TVASSCS; The Veterans Administration Systemic Sepsis Cooperative Study Group. Effect of high-dose glucocorticoid therapy on mortality in patients with clinical signs of systemic sepsis. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:659–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709103171102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cronin L, Cook DJ, Carlet J, Heyland DK, King D, Lansang MA, Fisher CJ., Jr Corticosteroid treatment for sepsis: a critical appraisal and meta-analysis of the literature. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1430–1439. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199508000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Annane D. Corticosteroids for severe sepsis: an evidence-based guide for physicians. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:7. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Annane D, Sébille V, Charpentier C, Bollaert PE, François B, Korach JM, Capellier G, Cohen Y, Azoulay E, Troché G, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288:862–871. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, Moreno R, Singer M, Freivogel K, Weiss YG, Benbenishty J, Kalenka A, Forst H, et al. CORTICUS Study Group. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:111–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanna W, Wong HR. Pediatric sepsis: challenges and adjunctive therapies. Crit Care Clin. 2013;29:203–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]