Abstract

Objective

Obesity and Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) are associated, but evidence about how they relate over time is conflicting. The goal of this study was to examine prospective associations between depression and obesity from early adolescence through early adulthood.

Methods

Participants were drawn from a statewide, community-based, Minnesota sample. MDD and obesity with onsets by early adolescence (by age 14), late adolescence (between 14 and 20), and early adulthood (ages 20 to 24) were assessed via structured interview (depression) and study-measured height and weight.

Results

Cross-sectional results indicated that depression and obesity with onsets by early adolescence were concurrently associated, but the same was not true later in development. Prospective results indicated that depression by early adolescence predicted the onset of obesity (odds ratio=3.76, confidence interval= 1.33–10.59) during late adolescence among females. Obesity that developed during late adolescence predicted the onset of depression (odds ratio=5.89, confidence interval= 2.31–15.01) during early adulthood among females.

Conclusions

For girls, adolescence is a high risk period for the development of this comorbidity, with the nature of the risk varying over the course of adolescence. Early adolescent-onset depression is associated with elevated risk of later onset obesity, and obesity, particularly in late adolescence, is associated with increased odds of later depression. Further investigation into the mechanisms of these effects and the reasons for the observed gender and developmental differences is needed. Prevention programs focused on early-onset cases of depression and adolescent-onset cases of obesity, particularly among females, may help in reducing risk for this form of comorbidity.

Keywords: obesity, depression, comorbidity, prospective, adolescence

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and obesity are associated;1,2 however, the nature and directionality of this association remains unclear. Estimates of risk indicate that people with one of these disorders at some point during their lifetimes are at approximately 1.5 to 2 times increased risk of having the other disorder, with some subgroups (e.g., women) with one of these disorders experiencing more than double the risk for the other disorder compared to non-affected people.3–6 Due to possible developmental differences in these associations and limitations of the present literature, the goal of this study was to describe the cross-sectional and prospective, across-time associations between these disorders from early adolescence through early adulthood.

There are three possible pathways that could account for the comorbidity of these disorders: obesity may predispose people to depression, depression may predispose people to obesity, or a third factor may predispose people to both. Obesity could lead to depression through weight stigma,7 poor self-esteem,8 and/or functional impairment (reduced mobility and ability to engage in activities9). Depression could lead to obesity directly through the occurrence of depressive symptoms (e.g., increased appetite, poor sleep,10 lethargy resulting in decreased calorie expenditure and/or reduced energy to obtain and cook healthy foods), antidepressant medication side effects,11 or attempts to self-medicate depressive feelings with unhealthy foods. Common physiological factors involved in regulating mood and weight could result in this pattern of co-occurrence as well,12 as could environmental common factors (e.g., poverty, leading to hopelessness and reduced access to healthy food and safe recreational activities).

Age may moderate this association, such that childhood and adolescence may be a particularly vulnerable period for the development of this form of comorbidity. There are three broad reasons for this. First, early-onset cases are likely to be reflective of more severe liabilities to these disorders, which may be shared biologically12 or environmentally. Second, either disorder occurring early in development may be more likely to affect long-term psychological and behavioral characteristics than would disorders that have onsets later in development. Considering obesity-to-depression pathways, a child who is obese may be particularly susceptible to negative societal messages about obesity, teasing, or bad feelings stemming from poor performance in sports; these could increase risk for MDD. In contrast, an adult woman who developed obesity after menopause may be less susceptible to MDD because she already would have a sense of herself as a worthwhile person, her peers would be less likely to tease her, and she would not experience mandatory engagement in activities like gym class. Considering MDD-to-obesity pathways, eating and activity habits are still being formed in childhood and adolescence. Therefore, an MDD episode during this period, which could result in reduced activity (due to anhedonia, low energy, etc.) and/or unhealthy eating (to cope with negative affect or due to low self-esteem and not caring for oneself), could predispose the person to long-term unhealthy habits. In contrast, the onset of MDD in middle adulthood may result in temporary changes but would be less likely to result in the long-term changes that would be necessary to make that person transition from a healthy weight to an obese weight. Third, there are particular reasons that early-onset MDD may directly relate to the development of obesity: for example, sleep disturbance is found in nearly three-quarters of depressed children,13 and inadequate sleep is a risk factor for obesity.10 In addition, children and adolescents with MDD differ from adults with MDD on biological measures that may be relevant to the co-occurrence of obesity and MDD, such as basal cortisol secretion and immune responses.14

Both obesity-to-depression and depression-to-obesity pathways have found empirical support: among community-based longitudinal studies, a recent review found that 80% of those examining obesity-to-depression pathways found evidence for their statistical significance, while 53% of those examining depression-to-obesity pathways found evidence for their statistical significance.1 Unfortunately, this literature is characterized by methodological limitations.1 At a basic level, of community-based longitudinal studies, only one has used study-measured (as opposed to self-reported) height and weight (and resulting obesity diagnoses) and clinical interview assessments of MDD (as opposed to questionnaire measures of depression15). Most studies do not examine potential developmental change in the association between obesity and depression, and not all examine potential differences by sex.1

The goal of this study was to examine cross-sectional and prospective associations between MDD and obesity in a community-based sample of youth followed prospectively from age 11 through age 24. Our focus was on obesity and MDD with onsets during adolescence, with specific examinations of onsets during early (by age 14) and late (between ages 14 and 20) adolescence. We focused specifically on disorder onsets—not recurrence or persistence—because the earlier occurrence of each disorder strongly predicts its later occurrence. Therefore, we believed that understanding factors related specifically to the initial development of each disorder was crucial. We expected that disorders with onsets during the adolescent period would be particularly problematic for the reasons outlined above. Strengths of this study included: (1) the use of study-assessed height and weight measurements and resulting obesity diagnoses, (2) the use of clinical interview-based diagnoses of MDD; (3) participant assessments at five uniform ages (11, 14, 17, 20, and 24), thereby allowing for the consideration of potential developmental differences; and (4) the examination of potential gender differences in these associations.

Based on previous research on MDD-obesity comorbidity and theory regarding the effects of development, we expected cross-sectional associations between these disorders to be significant, particularly earlier in development. Earlier MDD was expected to predict the later onset of obesity and earlier obesity was expected to predict the later onset of MDD. Although we expected that disorders developing during adolescence would be particularly predictive of the later development of the other disorder, based on a lack of previous literature, we did not make specific predictions regarding whether early or late adolescence would be more influential.

Methods

Participants

Participants were drawn from the Minnesota Twin Family Study, a community-based sample of adolescents and their families. This sample was utilized because the participants were representative of Minnesota families with children living at home (based on the 2000 US Census)31 and because it included rigorous, developmentally-timed assessments of key study variables (see above). Of eligible families, 83% participated. Youth were born between 1977 and 1982 (males) or 1981 and 1985 (females). Participants (752 males, 760 females) were first recruited and assessed when the youth were 11 (mean=11.7, SD=.4) and were invited back to return to the study at ages 14 (mean=14.8, SD=.5), 17 (mean=18.2, SD=.7), 20 (mean=21.5, SD=.8), and 24 (mean=25.3, SD=.7). Retention was strong (participation rates averaged over 90% at each wave). Although twin zygosity was not considered in this report, both monozygotic (N=487) and dizygotic (N=269) pairs comprised the sample. This study was approved by the University of Minnesota IRB, and participants gave informed consent (if 18 or over or parent on behalf of a minor child) or assent (for minors).

Consistent with the population of the state of Minnesota at the time these youth were born, approximately 95% of the sample was White. Additional information about the study design and participants is provided elsewhere.16

Measures

MDD

MDD was assessed in youth younger than age 17 using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children and Adolescents17 and in youth ages 17 and older using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R18. Diagnostic interviews were conducted in person by trained interviewers with bachelor’s or master’s degree in Psychology, reviewed by teams of advanced clinical psychology doctoral students who achieved consensus agreement for each assessed symptom of MDD, and diagnosed using computer algorithms following DSM rules (kappas = .78 or better). For youth 17 and younger, diagnoses reported by either the mother or the child were counted as present (the best-estimate method19–21). Definite and probable (exhibiting all symptoms necessary for the diagnosis except one22) diagnoses were used. At the initial assessment, lifetime diagnoses were assessed; after that, MDD was assessed since the last visit to the study. Diagnoses reported at either age 11 or age 14 were combined into an assessment of MDD during early adolescence. If MDD was first reported at 17 or 20, this was considered to represent late adolescent-onset MDD. If MDD was first reported at 24, this was considered to represent an onset of MDD during early adulthood.

Obesity

Height and weight were assessed using a Detecto mechanical physician scale with height rod. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the standard formula (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). For youth at age 20 and 24, the standard BMI cutoff of 30 was used to define obesity. For youth younger than age 20, growth curves from the Center for Disease Control23 were used to determine obesity cutoffs (95th percentile) for each age and sex based on the average participant ages at each assessment23,24 (age 11: 23.90 for males, 24.89 for females; age 14: 26.71 for males, 27.99 for females; age 17: 28.90 for males, 30 for females). Analogous to MDD, obesity first occurring at age 11 or age 14 was combined into an assessment of obesity during early adolescence. If obesity was first present at 17 or 20, this was considered to represent late adolescent-onset obesity. If obesity was first present at 24, this was considered to represent an onset of obesity during early adulthood.

Statistical Analyses

SAS version 9.2 was employed to compute generalized estimating equations (GEEs; PROC GENMOD) to account for the correlated observations in this sample (twins nested within families25). This procedure fits generalized linear models using maximum-likelihood methods. Specifically, logistic regression models for binomial data were used. The default correlation structure (independent) was used. There was little missing data because if a participant missed an early assessment, the relevant data for the missed assessment were obtained in a subsequent assessment. In cases where a data point was missing, PROC GENMOD excludes that individual from that analysis.

First, prevalences of the onset of each disorder during each developmental period, as well as anytime prior to the final assessment, were computed and compared across sex using GEEs. Next, in order to examine cross-sectional associations between these disorders, tetrachoric correlations were conducted (reported with asymptotic standard errors) to describe the associations between MDD and obesity with onsets occurring within each developmental stage (early adolescence, late adolescence, and early adulthood), as well as onsets anytime prior to the final assessment.

For the prospective (i.e., across time) analyses that were the focus of our study, because of our interest in disorder onsets (rather than the recurrence or persistence of disorders), some participants were eliminated from certain analyses due to their having earlier onset of the disorder. For example, if a participant experienced MDD prior to age 14, he/she was not included in analyses predicting obesity onsets in early adulthood from MDD onsets between 14 and 20 (because the MDD onset had been experienced prior to that).

For the prospective analyses, GEEs were used. For each analysis described below, two models were examined. The first examined the overall effect of one disorder on the other, adjusting for the effect of gender. The second included a disorder-by-gender interaction term in order to assess the significance of gender differences in the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

First, we examined whether the occurrence of obesity by age 14 predicted the development of MDD (1) during late adolescence, and (2) during early adulthood. Second, we examined the association between obesity first developing during late adolescence and the onset of MDD in early adulthood. Next, we examined the opposite directions of effect: MDD by age 14 predicting the development of obesity (1) during late adolescence and (2) during early adulthood; and MDD first developing during late adolescence and the onset of obesity in early adulthood.

For inclusion in the analysis, participants were required to have data at the oldest assessment point within each developmental period (age 14 for early adolescence, age 20 for late adolescence, and age 24 for early adulthood). Data were occasionally missing at the younger assessment point (age 11 for early adolescence and age 17 for late adolescence). If a participant missed one of these assessments, when he or she returned, MDD was assessed since the previous visit to the study; therefore, these entire developmental periods were covered. For obesity, the only way a case would have been missed would be if the participant first became obese and then became non-obese all within a 6-year period.

Results

Gender differences in the prevalences of MDD, obesity, and their co-occurrence

Prevalences of the onset of each disorder during early adolescence, late adolescence, and early adulthood, as well as at any time prior to age 24, are presented in Table 1 separately by gender. Turning to the bottom 3 rows, by age 24, lifetime rates of MDD (26.5% males, 36.4% females) and co-occurring MDD and obesity (7.8% males, 11.9% females), but not obesity considered alone (25.7% males, 27.5% females), differed by gender, with women having higher rates than men.

Table 1.

Gender similarities and differences in the prevalence of obesity, major depressive disorder (MDD), and their co-occurrence during different developmental stages

| Prevalence by gender (%) |

Gender difference (Odds ratio, 95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | ||

| MDD by early adolescence (14) | 7.2 | 7.0 | .98 (.62–1.53) |

| Obesity by early adolescence (14) | 10.7 | 14.7 | 1.45§ (.95–2.20) |

| Both MDD and obesity by early adolescence (14)1 | 1.3 | 1.8 | |

| MDD first occurring in late adolescence (14–20) | 12.0 | 18.9 | 1.72** (1.21–2.43) |

| Obesity first occurring in late adolescence (14–20) | 8.5 | 6.0 | .68 (.40–1.18) |

| Both MDD and obesity first occurring in late adolescence (14–20)1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | |

| MDD first occurring in early adulthood (20–24) | 7.6 | 12.3 | 1.72** (1.12–2.62) |

| Obesity first occurring in early adulthood (20–24) | 7.4 | 7.7 | 1.05 (.61–1.83) |

| Both MDD and obesity first occurring in early adulthood1 | 1.4 | 0.6 | - |

| MDD with an onset anytime by age 242 | 26.5 | 36.4 | 1.59*** (1.22–2.07) |

| Obesity with an onset anytime by age 242 | 25.7 | 27.5 | 1.09 (.79–1.51) |

| Both MDD and obesity first occurring anytime by age 243 | 7.8 | 11.9 | 1.68* (1.05–2.67) |

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

CI=confidence interval. Odds ratios presented in the rightmost column represent the risk for the indicated disorder associated with being female (compared with being male). Significance levels are derived from Z-scores computed based on the GEE parameter estimates, with the empirical standard error estimates used.

Odds ratio not computed due to small cell size.

Tabled values are not exact sums of the onsets during each developmental period due to missing data at different assessment points.

Tabled values are not sums of the co-occurrences during each developmental stage due to many co-occurring cases experiencing onsets during different developmental periods (e.g., MDD during early adolescence and obesity during late adolescence), as well as missing data.

Turning to specific developmental stages, gender differences were evident for MDD in late adolescence (12.0% males, 18.9% females) and early adulthood (7.6% males, 12.3% females), with females showing higher rates than males. As can be seen from Table 1, the co-occurrence of the onsets of the two disorders at each developmental stage was uncommon, never attaining a rate higher than 1.8% for either gender, and thus did not occur with sufficient frequency to justify computing odds ratios.

Cross-sectional associations between MDD and obesity

By age 24, the lifetime occurrence of obesity and MDD was significantly correlated (r=.14, SE=.05, p<.05). However, of particular interest was how the correlation between these conditions varied with development; we expected that there would be stronger correlations at younger, compared to older, ages. MDD and obesity were significantly correlated if both occurred by early adolescence (r=.20, SE=.08, p<.05), but the correlation was not significant when MDD and obesity first occurred in late adolescence (r=.03, SE=.09) or in early adulthood (r=.09, SE=.11).

Prospective associations between earlier obesity and later MDD

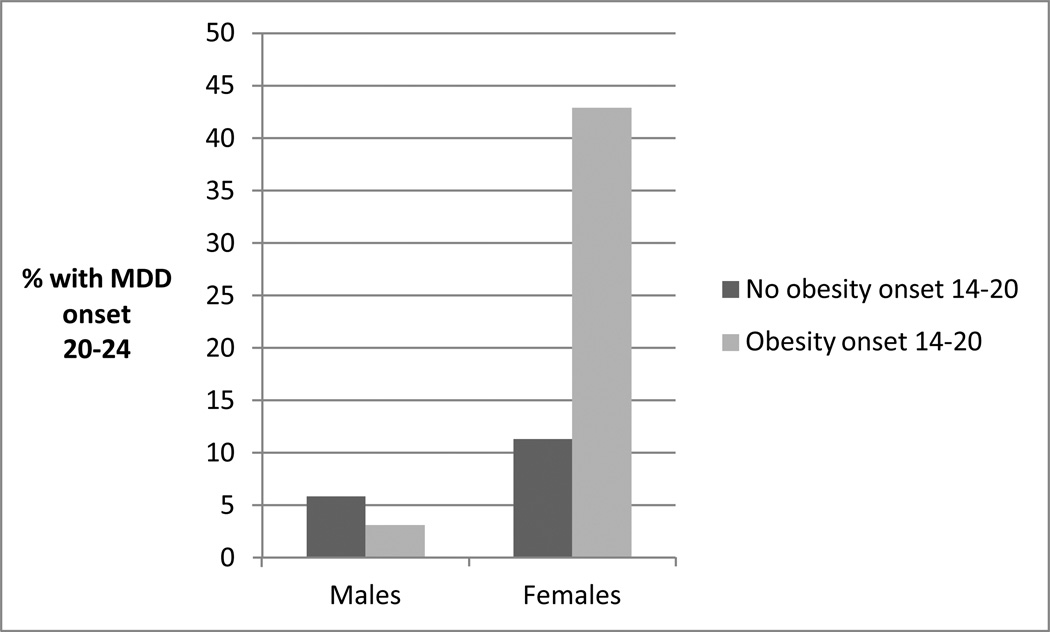

As can be seen from Table 2, obesity that developed by early adolescence did not significantly predict the onset of MDD anytime during the follow-up period (during late adolescence or early adulthood), though there was a trend for early adolescent obesity to predict the onset of MDD during the late adolescent period. Obesity that developed in late adolescence did predict the onset of MDD in early adulthood among females (a gender-by-obesity interaction effect; Figure 1).

Table 2.

Prospective associations between obesity and major depressive disorder (MDD).

| Risk for new onset of the other disorder in late adolescence (14–20) |

Risk for new onset of the other disorder in early adulthood (20–24) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main effect | Interaction effect with gender | Main effect | Interaction effect with gender | |

| MDD by early adolescence (14) | 1.42 (.58–3.46) N=932 |

2.44* (1.14) |

1.02 (.37–2.85) N=821 |

.03 (1.05) |

| Males: .33 (.05–2.36) | ||||

| Females: 3.76 (1.33–10.59) | ||||

| Obesity by early adolescence (14) | 1.53§ (.96–2.44) N=1072 |

.40 (.51) |

.70 (.33–1.49) N=908 |

−.27 (.79) |

| MDD first occurring in late adolescence (14–20) | 1.31 (.61–2.81) N=762 |

−1.13 (.75) |

||

| Obesity first occurring in late | 2.83** | 2.43* | ||

| adolescence (14–20) | (1.32–6.09) N=731 |

(1.15) | ||

| Males: .52 (.07–4.03) | ||||

| Females: 5.89 (2.31–15.01) | ||||

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01. Significance levels are derived from Z-scores computed based on the GEE parameter estimates, with the empirical standard error estimates used.. Predictor variables are in the leftmost column, with outcome variables in the center and rightmost columns. For example, considering the leftmost column of the top row of results, 1.42 represents the increased odds (odds ratio) for the onset of obesity by late adolescence among participants with MDD by early adolescence. Figures in the “main effect” columns represent odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals); figures in the “interaction effect with gender” columns represent parameter estimates and associated standard errors and are followed by odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) for each gender separately. The sample size for each analysis is presented beneath each odds ratio in the “main effect” columns (identical sample sizes apply to the corresponding interaction effect analyses).

Figure 1.

Late adolescent-onset obesity and MDD onset in early adulthood: Associations by gender (n=731).

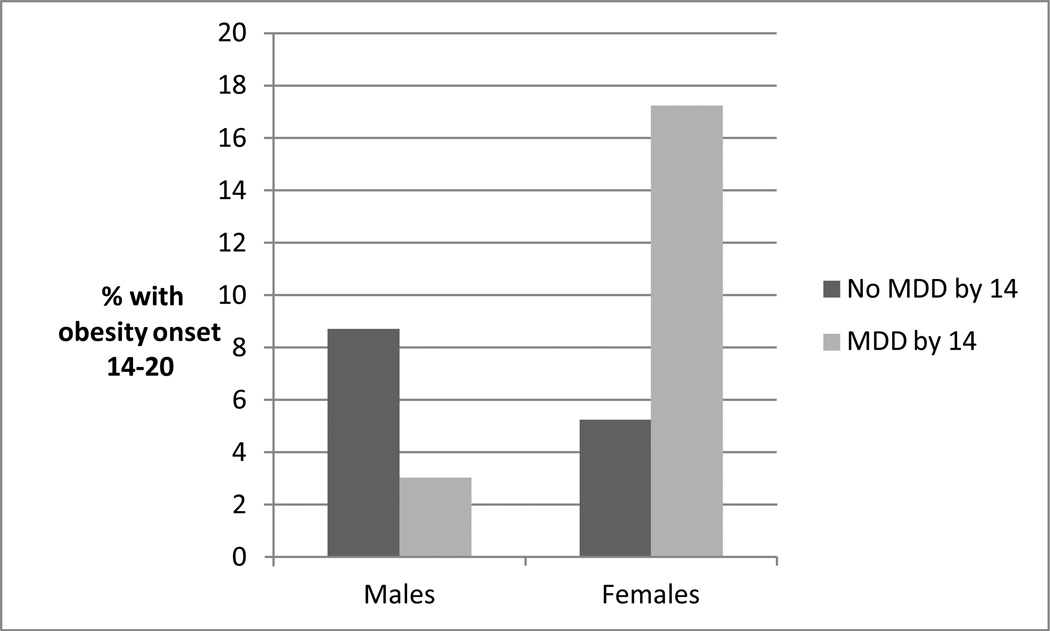

Prospective associations between earlier MDD and later obesity

As can be seen in Table 2, MDD that developed by early adolescence predicted the onset of obesity in late adolescence among females (a gender-by-MDD interaction effect; Figure 2). MDD that developed in late adolescence did not predict the onset of obesity in early adulthood.

Figure 2.

Early adolescent-onset MDD and obesity onset in late adolescence: Associations by gender (n=932).

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that there appear to be developmental as well as gender differences in the association between MDD and obesity. MDD occurring by early adolescence predicted the development of obesity in late adolescence among females. Conversely, obesity with an onset during late adolescence predicted the onset of MDD in early adulthood among females. We did not find evidence for significant prospective associations between these disorders among males. In addition, MDD and obesity developing by early adolescence were cross-sectionally associated with each other; this effect was not present at later ages.

The results of this study were consistent with our expectations and highlight the importance of the adolescent period in the development of comorbidity between these disorders. Regarding cross-sectional associations, we anticipated that these disorders would be more strongly related at younger, compared to older, ages, and MDD and obesity with onsets during childhood and early adolescence were cross-sectionally related while disorders with later onsets were not. It is important to note that within this key developmental period (i.e., by age 14), we do not know which disorder developed first, or whether they developed simultaneously.

The prospective results were also consistent with expectations, with each disorder during adolescence predicting the later onset of the other disorder among females. However, the specific period of risk differed by disorder. The earliest-onset cases of MDD appear to be most predictive of later obesity for girls; this could be for any of the reasons discussed earlier, including the still-developing eating and activity habits of young people or the symptom differences between childhood MDD and MDD in adults.10,13,14 Interestingly, the earliest-onset cases of obesity were not the most predictive of later-onset MDD, though they were concurrently associated with MDD. Although obesity by early adolescence (age 14) did not significantly predict the later onset of MDD (though this effect was significant at a trend level, with obese early adolescents being at 1.5 times the risk of non-obese adolescents for developing MDD in late adolescence, and no significant gender difference in this trend), obesity developing during late adolescence (14–20) was particularly predictive of the later onset of MDD among females. Perhaps body-related insecurities and/or peer pressure relating to body shape and weight are at a height during this late adolescent period (when the pressure to conform to peer norms is high and dating relationships are forming) and therefore young women who experience the onset of obesity during this time are particularly vulnerable to the subsequent onset of MDD.

Considering lifetime diagnoses by age 24, both MDD and co-occurring MDD and obesity were more prevalent among women. Significant gender interaction effects were found for prospective associations in both directions, with the increased risk for the other disorder being found among young women specifically. These gender differences could be due to any number of factors. For example, obesity may be a more stigmatized condition among females26,27 and/or women may be more likely to eat to cope with negative feelings than men.28 Interestingly, inspection of prevalences (Figures 1 and 2) indicates that males with either earlier disorder were at slightly decreased risk for the development of the other disorder; this may indicate the presence of significantly different pathways for the development of these disorders among males and females.29

The results of this study are broadly consistent with prior prospective research that used study-assessed MDD and obesity diagnoses. Specifically, Richardson and colleagues15 found that MDD between 11 and 15 was not associated with obesity at 26, though later MDD (between 18 and 21) was for females. We also found that effects were strongest on the adjacent developmental period (early to late adolescence for the MDD to obesity pathway). However, we did not replicate their effect of MDD between 18 and 21 (similar to the latter half of our late-adolescent period) on later obesity in females; the reasons for this difference are unclear but may relate to Richardson et al.’s examination of the occurrence of MDD and obesity, not specifically the first onsets of these disorders.

The results of this study imply that prevention efforts aimed at both of these disorders in childhood and adolescence may be fruitful in decreasing the prevalence of this form of comorbidity. In particular, preventing MDD by early adolescence has the potential to decrease the later onset of obesity, and preventing the development of obesity during later adolescence (and perhaps early adolescence as well, given the trend-level effect found for that period) has the potential to decrease the prevalence of early adult-onset MDD, particularly among women. Future research examining the mechanisms for these findings would be useful for prevention efforts. For example, if decreased activity among depressed youth moderates this association, then encouraging young girls with depression to exercise and/or participate in sports as they are being treated for depression may prevent the later onset of obesity.

Although we found differences in the associations between these disorders depending on whether we examined the period from early adolescence to late adolescence or late adolescence to early adulthood, our methodology did not allow us to directly test for the presence of developmental differences (e.g., by examining age interaction effects, as we did to test for gender differences). Therefore, it is possible that the differences in significance that we found by developmental stage are not indicative of true developmental differences. For instance, although obesity first occurring in late adolescence was strongly associated with increased odds of MDD (OR=2.83), obesity occurring by early adolescence showed a weak association with MDD (OR=1.53) that just missed significance (see Table 2). As we have noted above, from this we would not conclude that risk is only elevated in late adolescence. However, a somewhat different picture emerged for MDD as a risk factor for obesity, especially in girls. The interaction effect for MDD by early adolescence leading to obesity was significant, indicating that the risk was especially elevated for girls (OR=3.76). For MDD first occurring in late adolescence, the interaction effect was not only not significant, but in the opposite direction, indicating that for girls, MDD was associated with non-significant but slightly reduced risk of obesity. Although this pattern of results cannot rule out that MDD first occurring in late adolescence is associated with elevated risk for obesity, it nonetheless offers plausible support backing the hypothesis that the key risk period in the MDD to obesity association is in early adolescence for girls In sum, until other research directly examines interaction effects by age, it is important to consider the developmental differences we found to be tentative.

This study had limitations. For example, the sample was overwhelmingly White. It is not clear how these results would generalize to other samples; however, other research has not found different associations between these disorders among African-American and White adolescents30 and our sample was representative of the state of Minnesota at the time these participants were born.31

In sum, the results of this study indicate that among women, MDD occurring by early adolescence predicts the later onset of obesity. Conversely, adolescent-onset obesity among women (perhaps particularly obesity with an onset in late adolescence) predicts the later onset of MDD. In addition, the onsets of these disorders are cross-sectionally associated in childhood and early adolescence, but not later. Research investigating possible mechanisms accounting for these differing associations in different developmental periods would be useful.32 In addition, studies examining prevention and treatment efforts focusing on early-onset cases of MDD and adolescent-onset cases of obesity are warranted, as these may be most likely to reduce risk for the later development of the other disorder.

Acknowledgements

Sources of support: This research was supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: DA022456, DA05147, AA09367.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Faith MS, Butryn M, Wadden TA, Fabricatore A, Nguyen AM, Heymsfield SB. Evidence for prospective associations among depression and obesity in population-based studies. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e438–e453. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon GE, von Korff M, Saunders K, Miglioretti DL, Crane PK, van Belle G, et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:824–830. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atlantis E, Baker M. Obesity effects on depression: Systematic review of epidemiological studies. Int J Obes. 2008;32:881–191. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniel J, Honey W, Landen M, Marshall-Williams S, Chapman D, Lando J. Mental health in the united states: Health risk behaviors and conditions among persons with depression--New Mexico. CDC: MMWR Weekly. 2003;54:989–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma J, Xiao L. Obesity and depression in US women: Results from the 2005–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Obes. 2010;18:347–353. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of depression and its treatment in the general population. J Psychiatric Res. 2007;41:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obesity Res. 2001;9:788–805. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss RS. Childhood obesity and self-esteem. Pediatrics. 2000;105:e15. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontaine KR, Barofsky I. Obesity and health-related quality of life. Obes Reviews. 2001;2:173–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gangwisch JE, Malaspina D, Boden-Albala B, Heymsfield SB. Inadequate sleep as a risk factor for obesity: Analyses of the NHANES I. Sleep. 2005;28:1289–1296. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.10.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fava M, Judge R, Hoog SL, Nilsson ME, Koke SC. Fluoxetine versus sertraline and paroxetine in major depressive disorder: Changes in weight with long-term treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:863–867. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v61n1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bornstein SR, Schuppenies A, Wong ML, Licinio J. Approaching the shared biology of obesity and depression: The stress axis as the locus of gene-environment interations. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:892–902. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Buysse DJ, Gentzler AL, Kiss E, Mayer L, Kapornai K, et al. Insomnia and hypersomnia associated with depressive phenomenology and comorbidity in childhood depression. Sleep. 2007;30:83–90. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaufman J, Martin A, King RA, Charney D. Are child-, adolescent-, and adult-onset depression one and the same disorder? Bio Psychiatry. 2001;49:980–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson LP, Davis R, Poulton R, McCauley E, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, et al. A longitudinal evaluation of adolescent depression and adult obesity. Arch Ped Adoles Med. 2003;157:739–745. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: Findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Psychol Med. 31:411–423. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reich W, Welner Z. The Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents-Revised-Child/Parent Forms. St. Louis, MO: Washington University; 1988. Unpublished documents. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baillargeon RH, Boulerice B, Tremblay RE, Zoccolillo M, Vitaro F, Kohen DE. Modeling interinformant agreement in the absence of a “gold standard. ”. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:463–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burt SA, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono WG. Sources of covariation among attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: The importance of shared environment. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;101:516–525. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:610–619. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E. Research diagnostic criteria: Rationale and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35:772–782. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770300115013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Center for Disease Control. 2000 http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/2000growthchart-us.pdf.

- 24.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. CDC growth charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Vital Health Stat, National Center for Health Statistics. 2002;11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;79:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falkner NH, French SA, Jeffrey RW, Neumark-Sztainer D, Sherwood NE, Morton N. Mistreatment due to weight: Prevalence and sources of perceived mistreatment in women and men. Obes Res. 1999;7:572–576. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiggemann M, Rothblum ED. Gender differences in social consequences of perceived overweight in the United States and Australia. Sex Roles. 1988;18:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingledew DK, Hardy L, Cooper CL, Jemal H. Health behaviours reported as coping strategies: A factor analysitcal study. Br J Health Psychol. 1996;1:263–281. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palinkas LA, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E. Depressive symptoms in overweight and obese older adults: A test of the ‘jolly fat’ hypothesis. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franko DL, Striegel-Moore RH, Thompson D, Schreiber GB, Daniels SR. Does adolescent depression predict obesity in black and white young adult women? Psychol Med. 2005;35:1505–1513. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holdcraft LC, Iacono WG. Cross-generational effects on gender differences in psychoactive drug abuse and dependence. Drug Alc Depend. 2004;74:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atlantis E, Goldney RD, Wittert GA. Obesity and depression or anxiety: Clinicians should be aware that the association can occur in both directions. BMJ. 2009;339:b3868. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]