Abstract

Objectives

Women report greater sleep disturbance during the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle and during menses. However, the putative hormonal basis of perceived menstrual cycle related sleep disturbance has not been investigated directly. We examined associations of objective measures of sleep fragmentation with reproductive hormone levels in healthy, premenopausal women.

Methods

27 women with monthly menses had hormone levels measured at two time points during a single menstrual cycle: the follicular phase and the periovulatory to mid-luteal phase. A single night of home polysomnography (PSG) was recorded on the day of the periovulatory/mid-luteal phase blood draw. Serum progesterone, estradiol, and estrone levels concurrent with PSG and rate of change in progesterone (PROGslope) from the follicular blood draw to PSG were correlated with log-transformed wake after sleep onset (lnWASO%) and number of wakes/hour of sleep (lnWake-Index) using linear regression.

Results

Sleep was more fragmented in association with a steeper PROGslope (lnWASO% p=0.016; lnWake-Index p=0.08) and higher concurrent estrone level (lnWASO% p=0.03; lnWake-Index p=0.01), but the effect of estrone on WASO was lost after accounting for PROGslope. WASO% and Wake-Index were not associated with concomitant progesterone or estradiol levels.

Conclusions

A steeper rate of rise in progesterone levels from the follicular phase through the mid-luteal phase was associated with significantly greater WASO, establishing a link between reproductive hormone dynamics and sleep fragmentation in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.

Keywords: menstrual cycle, progesterone, estradiol, estrone, sleep, premenopausal, polysomnography

Introduction

Studies in premenopausal women have documented more subjective sleep disruption during the week preceding menses [1, 2] and during menses [2], coinciding with fluctuating levels of progesterone and estrogens. Sleep complaints include longer sleep-onset latency, lower sleep efficiency, and worse sleep quality during the mid- through late-luteal phase compared with the mid-follicular phase [1] and lower subjective sleep quality [1, 2] during the late-luteal phase and menses compared with the mid-follicular, ovulatory, and early/mid luteal phases. In general, the few polysomnographic studies that have examined sleep at different phases of the menstrual cycle in young, healthy women with no sleep complaints have found that sleep efficiency remains high and relatively stable across the menstrual cycle [3–6], although at least one small study detected higher arousal indices and more wake after sleep onset in a sample of 12 healthy young women studied during the mid- through late-luteal phase [7].

While these studies have linked sleep disturbance and changes in sleep architecture to the mid- through late-luteal phase, fluctuations in reproductive hormones, including declining levels of estradiol and progesterone prior to menses, were assumed but not measured. Sleep quality has not been examined specifically in relation to reproductive hormone levels or their trajectories. The subjective and objective observations of reduced sleep quality during the mid- through late-luteal phase suggest that progesterone plays a critical role, but levels of estrogens also rise and fall in the luteal phase, raising the possibility that both of these reproductive hormones may adversely affect luteal-phase sleep quality. As a result, it is not clear how mid- through late luteal-phase worsening of sleep quality relates to specific hormone levels or the rate of change in reproductive hormone levels across the menstrual cycle.

During an ovulatory menstrual cycle, progesterone is monotonic, produced only by the corpus luteum after ovulation and rising during the luteal phase until levels peak mid-luteally, then decline during the late luteal phase [8]. Progesterone is responsible for the luteal-phase increase in core body temperature of 0.3–0.6°C [9], a level of elevation in core body temperature that has been shown to fragment sleep [10]. Therefore, the effect of progesterone on body temperature is a putative mechanism by which progesterone could disturb sleep. Progesterone is also a GABAA receptor agonist [11] that has been shown to increase NREM sleep [12, 13]. Indeed, observations of increased sleep disturbance in the mid- through late-luteal phase have been attributed to changing levels of progesterone [14], although the relationship has not been studied empirically.

In contrast to progesterone, estradiol rises and falls twice during the menstrual cycle: first during the late follicular phase prior to ovulation and then again during the luteal phase [8]. Estrone is a weaker estrogen produced and stored in adipose tissue [15], rather than the ovary, that mirrors the biphasic dynamics of estradiol, the most potent estrogen. Unlike progesterone, estrogens decrease core body temperature in the absence of progesterone [16], which may protect against sleep disruption. However, data bearing on the effect of estrogens on sleep quality are mixed, with estrogen therapy shown to improve sleep quality in postmenopausal women with hot flashes [13, 17–21], but also to disrupt sleep by decreasing REM and NREM sleep in ovariectomized rodents [22].

The primary aim of this study was to examine the association of objective measures of sleep fragmentation during the luteal phase in healthy premenopausal women in relation to concurrent levels of progesterone and the rate of change in progesterone from the follicular to mid-luteal phase. We hypothesized that higher progesterone levels as well as a steeper increase in progesterone would be associated with more sleep fragmentation. Our second, exploratory aim was to examine associations of sleep measures with concurrent levels of estrogens (estradiol and estrone), given the inconsistencies in the literature on estrogens’ effects on sleep and the gap of knowledge about the impact of physiologic levels of estradiol and estrone on sleep in premenopausal women.

Methods

Participants

Healthy premenopausal women ages 18–45 with monthly menstrual cycles (defined as every 23−35 days for the past 6 months) were recruited from the community to an experimental study using leuprolide to induce hot flashes and to study changes in sleep and mood occurring secondary to hot flashes (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00455689 [23]). The current analysis is based on the PSG and serum hormone data obtained at baseline before leuprolide was administered.

Women were excluded if they were pregnant; had a sleep disorder diagnosis confirmed with in-laboratory screening PSG (n=1 excluded for obstructive sleep apnea, n=1 for periodic limb movement disorder); worked a night shift job; reported experiencing hot flashes; had a current or prior history of psychiatric illness or substance-use disorders confirmed on structured psychiatric assessment; had abnormal screening blood tests (hemoglobin, thyroid-stimulating hormone, prolactin, renal or liver function); or had BMI > 35 kg/m2. A Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS] score < 10 was required to exclude those with depressive symptoms. Women taking or recently using prescription or over-the-counter centrally active medications (antidepressants, anxiolytics, hypnotics, or the anticonvulsant gabapentin) or systemic hormone medications (e.g., birth control pills) were excluded. All participants provided written informed consent and this study was approved by the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Boards.

Sleep Measures

Prior to mid-luteal administration of leuprolide, participants completed 2 nights of home PSG scheduled between the peri-ovulatory and mid-luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. Data from the second home PSG were used in the present analyses because hormone levels were obtained concurrent with the second PSG. PSG studies were not obtained during the follicular phase.

PSGs were conducted with the Compumedics Safiro (Charlotte, NC) using standard procedures to define sleep staging, including electroencephalogram (EEG), bilateral electro-oculogram, and bilateral submentalis electromyogram [24]. Respiratory and ECG signals were not measured. Concurrent with PSG, participants wore a time-synched actigraph with an event marker to record lights-out and lights-on time.

All records were visually scored in 30-second epochs by the Harvard Polysomnography Core using AASM criteria [24]. The primary measures of sleep fragmentation were: 1) WASO as a percent of sleep period time, and 2) the number of awakenings per hour of sleep. Awakenings were defined as alpha EEG activity comprising >15 seconds of a 30-second epoch. Stage N1 percent, Stage N2 percent, Stage N3 percent, REM percent, and sleep efficiency were also obtained.

Hormone Measurements

Participants were followed closely across one menstrual cycle, from the first day of menstrual bleeding until the mid-luteal phase. Leuprolide was administered approximately 7 days after ovulation, which was determined by an increase in basal body temperature and urinary luteinizing hormone. Blood was drawn first in the follicular phase (“follicular”) and then concurrent with the PSG (“concurrent”), which was obtained between the peri-ovulatory and mid-luteal phase before the leuprolide injection based on logistic considerations. As a result, the interval between the blood draw at the PSG and the preceding follicular phase draw varied.

Blood samples were assayed for serum progesterone (PROG), estradiol (E2), and estrone (E1) at both time points. We calculated the rate of change in progesterone between the 2 blood draws over the intervening time interval (PROGslope) to determine the rate of increase in progesterone leading up to the PSG. Slope was not calculated for E2 or E1 because estrogens are biphasic between the two time points that were measured.

Hormone Assays

Serum progesterone was measured by automated immunoassay (ARCHITECT®, Abbott Diagnostics, Chicago, IL) [25]. The minimum reportable concentration of this test is 0.1 ng/mL. The inter-assay CVs are 5.2%, 3.8% and 3.5% for quality control sera containing 0.7, 6.9, and 16.7 ng/mL, respectively. The reference ranges for women with regular menstrual cycles are follicular phase < 0.1 to 0.3 ng/mL and luteal phase 1.2 to 15.9 ng/mL.

Estradiol and estrone were measured using liquid chromatography, tandem mass spectrometry (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, NY) [26, 27]. The interassay coefficient of variation (CV) ranges for estradiol and estrone in the low range studied was 8.6% and 8.7%, respectively [26].

Statistical Analyses

We used SPSS Version 19 (IBM, Chicago, IL) for data analysis. Shapiro-Wilk tests were used to evaluate the normality of the distributions of our dependent variables. Neither WASO% (Shapiro-Wilk =0.191, p=0.013) nor Wake-Index (Shapiro-Wilk =0.174, p=0.035) was normally distributed, so these measures were transformed using the natural log function. Differences in sleep measures between women who did and did not have a luteal rise in progesterone at the time of the PSG were examined with Mann-Whitney U tests. Simple linear regressions examined associations of sleep fragmentation (lnWASO% and lnWake-Index) from the PSG with concurrent PROG, E1, and E2 levels as well as with PROGslope leading up to the PSG. Given the concomitant changes in reproductive hormones during the luteal phase, multiple linear regression models were developed to determine the relative impact of hormones associated with sleep fragmentation in adjusted analyses (i.e., concurrent E1 and PROGslope) on PSG sleep. Model fit was assessed, including checks for normally distributed residuals and absence of outliers or highly influential observations [28]. Alpha<.05 was considered statistically significant. A similar approach was used for secondary exploratory analyses of other standard PSG sleep measures (N1%, N2%, N3%, REM%, Sleep Efficiency, Sleep Onset Latency).

Results

Subject Demographics, Sleep Characteristics, and Hormone Levels

Of 29 women who completed the parent protocol, data for the current analysis were available in 27 subjects who had hormone data concurrent with the PSG. Participants had a mean ± SD age of 26.9 ± 6.6 years, and were racially diverse (17 white, 5 black, and 5 other race or multiracial women). Average body mass index was 25.8 ± 4.9 kg/m2; 5 women had a BMI between 25–30 kg/m2 (overweight), and 6 women were obese with a BMI > 30 kg/m2. Age, race and BMI were not associated with Wake Index or WASO.

Overall, we observed minimal sleep disturbance in this sample of young healthy women (Table 1) with high sleep efficiencies and expected sleep stage distributions consistent with normative values reported for young adults [29]. The median WASO was 11.5 minutes (interquartile range [IQR] 7–21) and the median number of awakenings was 15 (IQR 9–22) overall, translating into a median WASO% of 2.7% (IQR 1.7–4.7%) as a proportion of sleep period time and median Wake-Index of 1.9 (IQR 1.3–2.9) wakes per hour.

Table 1.

Summary of Polysomnographic Sleep Measures from one night of home polysomnography in 27 premenopausal women with regular menses.

| Measure | Mean | Standard Deviation |

Median | Interquartile Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Sleep Time (min) | 434 | 91 | 438 | 345–496 |

| Sleep Latency (min) | 18 | 21 | 11 | 7–22 |

| Sleep Efficiency (%) | 91.6% | 5% | 92.0% | 91–95% |

| Stage N1 % | 5% | 3% | 4% | 3–6% |

| Stage N2 % | 48.9% | 8.9% | 49.0% | 43–56% |

| Stage N3 % | 18.1% | 6.9% | 18.0% | 14–23% |

| Stage REM % | 25.2% | 6.0% | 24.0% | 22–28% |

| WASO % | 3.5% | 2.9% | 2.7% | 1.7–4.6% |

| # of Awakenings/hr of sleep | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.3–2.9 |

WASO%= minutes of wakefulness/sleep period time

The PSG and concurrent blood draw were obtained on a median menstrual cycle day of 18 (IQR 15–20). The follicular draw was obtained on a median menstrual cycle day of 5 (IQR 3–6). The time interval between the follicular draw and the PSG/concurrent draw was therefore a median of 13 days (IQR 10–15). PROG levels were ≤ 1ng/dL in all participants during the follicular draw and >3ng/dL in 16 (59.3%) participants (mean (SD) = 10.5 (6.2) ng/dL) at the time of the PSG, reflecting the mid-luteal phase of an ovulatory cycle. The remaining 11 (40.7%) participants completed their PSG peri-ovulatory and therefore their concurrent PROG level was <1 ng/dL because it had not yet risen. Among those with an increase in PROG between time points, the PROGslope showed a mean (SD) increase of 0.70 (0.40) ng/dL per day. Sleep measures for the groups of women who did and did not have a luteal rise in progesterone at the time of the PSG are shown in Table 2. Compared to women whose progesterone had not increased, women whose progesterone levels had risen had significantly higher N2% (p=.045) and a tendency (p=.068) for shorter total sleep times.

Table 2.

Home Polysomnographic Sleep Measures in Participants With and Without Progesterone Elevation

| Participants with an increase in progesterone, midluteal (n=16) |

Participants without an increase in progesterone, peri-ovulatory (n=11) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Mean (SD) |

Median | IQR | Mean (SD) |

Median | IQR |

| Total Sleep Time (min)* | 403(75) | 394 | 342–478 | 478(96) | 472 | 428–577 |

| Sleep Latency (min) | 22 (26) | 13 | 6–21 | 14(10) | 10 | 8–22 |

| Sleep Efficiency (%) | 90.6 (5.9) | 92.0 | 90.3–94.8 | 92.9(4.1) | 93 | 92–96 |

| Stage N1 % | 4.8 (2.7) | 4.0 | 3.0–5.8 | 5.5(3.0) | 5.0 | 3.0–6.0 |

| Stage N2 %** | 51.3 (9.8) | 52.5 | 48.3–56.8 | 45.5(6.4) | 44.0 | 40.0–50.0 |

| Stage N3 % | 16.5 (6.9) | 18.0 | 13.3–19.8 | 20.4(6.5) | 18.0 | 15.0–27.0 |

| Stage REM % | 24.4 (6.9) | 23.0 | 20.3–27.8 | 26.4(4.5) | 25.0 | 23.0–29.0 |

| WASO % | 3.5 (2.1) | 2.8 | 2.1–4.8 | 3.5(3.9) | 1.8 | 1.2–4.5 |

| Wake Index | 2.4 (1.1) | 2.3 | 1.5–3.2 | 2.2(1.5) | 1.8 | 1.1–2.8 |

WASO% = minutes of wakefulness/sleep period time

Wake Index = number of awakenings per hour of sleep

=Independent Samples Mann-Whitney U Test p <0.10

=Independent Samples Mann-Whitney U Test p <0.05

Mean (SD) estradiol and estrone levels concurrent with the PSG were 112.1 (61.0) pg/ml and 80.7 (40.7) pg/ml, respectively.

Associations of Concurrent Progesterone Levels and Progesterone Slope with Sleep Fragmentation

Concurrent PROG was not associated significantly with WASO% or Wake-Index (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations between hormone levels and polysomnographic sleep fragmentation

| ln WASO% | lnWake-Index | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone Measure |

n | β | 95% CI | p | R2 | β | 95% CI | p | R2 |

| Concurrent Progesterone (ng/dL) | 27 | .019 | −.025−.062 | .38 | .031 | .013 | −.020−.047 | .42 | .027 |

| Progesterone Slope (ng/dL per day) | 23 | .635 | 0.13–1.1 | .02 | .248 | .364 | −.06−.78 | .08 | .134 |

| Concurrent Estradiol (pg/ml) | 27 | .002 | −.002−.006 | .27 | .070 | .002 | −.002−.005 | .33 | .057 |

| Concurrent Estrone (pg/ml) | 27 | .008 | .001−.015 | .03 | .180 | .007 | .002−.012 | .01 | .223 |

lnWASO% = natural log transformation of WASO as a percent of sleep period time

lnWake-Index = natural log transformation of the number of awakenings per hour of sleep

Progesterone slope = change in progesterone level subtracting follicular draw from concurrent/PSG2 divided by number of days between blood draws

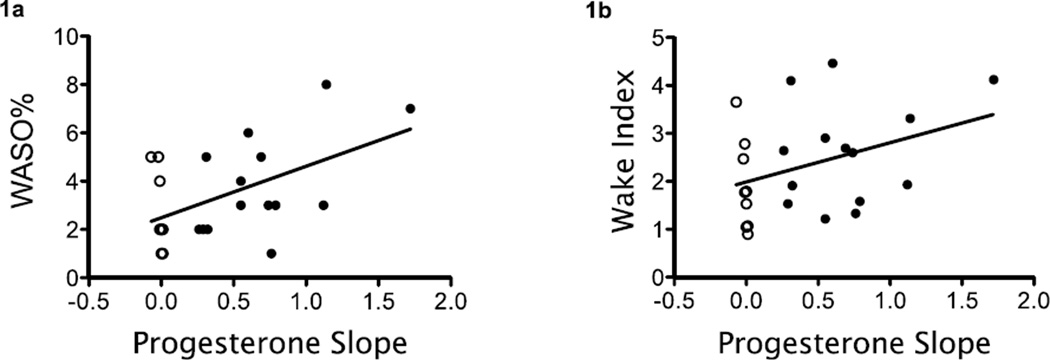

A steeper increase in PROG leading up to the PSG was associated with higher WASO% (lnWASO% vs. PROGslope: β=0.64, 95% CI 0.1 to 1.1, p=0.016; see Figure 1a). Results were consistent in a subgroup analysis (n=16) restricted to women whose PROG increased between the time points (lnWASO% vs. PROGslope: β=0.63, 95% CI -0.09 to 1.3, p=0.08). There was a statistical trend for an association between a steeper increase in the PROGslope and a higher Wake-Index (lnWake-Index vs. PROGslope: β=0.36, 95% CI -0.06 to 0.78, p=0.08; see Figure 1b). Thus, for each 0.1 ng/dL increase in the progesterone slope, the proportion of sleep time comprised of WASO increased by 8.9% and the number of wake episodes increased by 4.3 awakenings per hour.

Figure 1.

A steeper increase in progesterone slope was associated with more wakefulness after sleep onset (1a, p=0.016) and more awakenings per hour of sleep (1b, p=0.08). Dark circles indicate women with an elevated serum progesterone level at the time of PSG and open circles indicate women whose serum progesterone level had not yet risen. WASO% = minutes of wake after sleep onset ÷ sleep period time X 100. n=23 (slope could not be calculated in 4 women because of missing progesterone levels at blood draw 1)

Because the PROGslope calculation included a variable number of follicular phase days during which the progesterone levels were low (median = 10 days, IQR = 7–13), we conducted a sensitivity analysis of PROGslope in relation to lnWASO% and lnWake-Index after adjusting for number of follicular days. Results were consistent with the overall findings for WASO (lnWASO% vs. PROGslope: β=0.64, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.15, p=0.02) and Wake-Index (lnWake-Index vs. PROGslope: β=0.37, 95% CI -0.06 to 0.80, p=0.09).

There was no association between concurrent PROG or PROGslope with the other PSG measures listed in Table 1, including sleep-onset latency (data not shown).

Associations of Concurrent Levels of Estradiol and Estrone with Sleep Fragmentation

Concurrent E2 levels were not associated significantly with WASO% or Wake-Index (see Table 3) or with the other PSG measures listed in Table 1, including sleep-onset latency (data not shown).

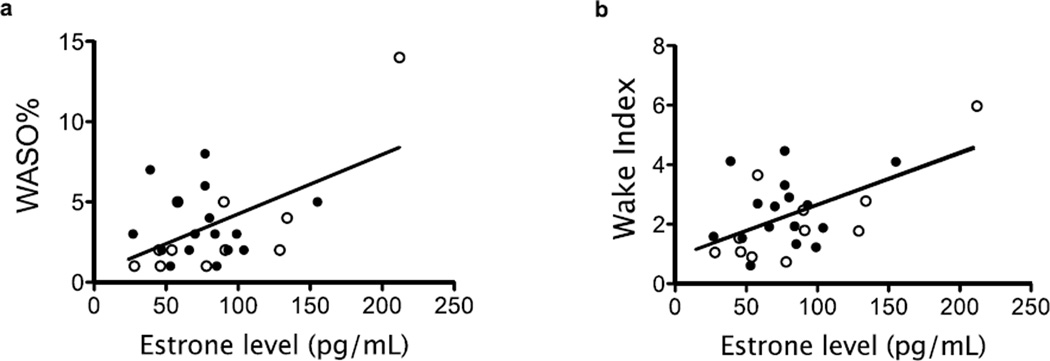

Higher E1 concurrent with the PSG was associated with higher WASO% (lnWASO% vs. E1: β=0.008, 95% CI 0.001 to 0.015, p=0.03, see Figure 2a) and higher Wake Indices (lnWake-Indexvs. E1: β=0.007, 95% CI 0.002 to 0.012, p=0.01, see Figure 2b). Thus, for each 1 pg/ml increase in the concurrent E1 level, the proportion of sleep time comprised of WASO increased by 0.8% and the number of wake episodes increased by 0.7 awakenings per hour. Because E1was correlated with higher BMI (r=0.41, p=0.03) and is produced and stored in adipose tissue [15], we examined whether BMI was driving the association of E1with WASO% and Wake Index. BMI correlated weakly with WASO% (r=0.31, p=0.12) and Wake Index (r=0.23, p=0.25). Adjustment for BMI did not attenuate the significant associations between these sleep measures and concurrent E1 (WASO%: β=0.008, 95% CI 0.000 to 0.015, p=0.05; Wake Index: β=0.007, 95% CI 0.001 to 0.013, p=0.02).

Figure 2.

A higher estrone level was associated with higher WASO% (2a, p=0.03) and more awakenings per hour of sleep (2b, p=0.01). Dark circles indicate women with an elevated serum progesterone level at the time of PSG and open circles indicate women whose serum progesterone level had not yet risen. n=27

Adjusted Analyses of Progesterone Slope and Concurrent Estrone in Relation to Sleep Fragmentation

A multiple linear regression model that included PROGslope and E1 showed significant independent effects of PROGslope (β=0.44, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.83, p=0.03) and E1 (β=0.006, 95% CI 0.000 to 0.012, p=0.04) on Wake-Index. For WASO%, the association with a steeper PROGslope remained strong after adjustment for E1 (β=0.704, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.20, p=0.008), but the contribution of E1 was attenuated (β=0.005, 95% CI -0.002 to 0.013, p=0.13).

Discussion

These results demonstrate that objective sleep interruption during the peri-ovulatory through mid-luteal phase of the menstrual cycle is proportionate to the preceding rate of rise in progesterone levels. These findings provide important biological evidence that changing levels of progesterone in cycling women are associated with objective sleep disturbance. Consistent with prior studies of PSG sleep quality in the follicular and luteal phases [3–6], we found no differences in sleep disruption when we examined our sample solely based on whether participants had or had not yet experienced a luteal-phase increase in progesterone. However, none of the previous studies measured hormone levels across the menstrual cycle, whereas our study results show specifically that the rate of rise in progesterone predicts the amount of mid-luteal phase sleep fragmentation. Variability in the rate of rise in progesterone between women may explain why some women experience sleep interruption during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle while others do not.

Our approach represents a first attempt to link sleep disturbance occurring during the mid- through late-luteal phase [1, 2, 7] with fluctuating levels of progesterone. Our findings are consistent with data showing worsening of sleep quality in response to a rise in core body temperature, which occurs in cycling women when progesterone levels begin to increase after ovulation [30]. This temperature rise occurs despite the co-occurring luteal-phase increase in estrogens, which have a weaker suppressive effect on core temperature [31]. Thus, we speculate that the thermal response to increasing levels of progesterone may explain the observed deleterious effect of increasing progesterone on sleep continuity. As we did not observe an association between sleep fragmentation and concurrent progesterone levels, it is possible that accommodation to progesterone exposure and sustained temperature elevation ultimately may occur by the mid-luteal phase. In order to investigate the specific contribution of declining levels of progesterone to sleep disturbance reported during the mid- to late-luteal phase [1, 2], future studies should examine changes in sleep and sleep disturbance in relation to the downward slope of progesterone levels at this time-point of the menstrual cycle. It is notable that progesterone can have hypnotic properties when administered to postmenopausal women [13, 32] and premenopausal women during the early-follicular phase [33], both of which are low estrogen states. In contrast, we observed a fragmenting effect of rising progesterone levels in the context of higher estrogen levels, a finding that emphasizes the importance of considering the overall hormonal milieu. Moreover, our findings related specifically to the rate of progesterone increase highlight the importance of examining sleep in relation to the changing hormone dynamics across the menstrual cycle and suggest that more static cross-sectional analyses of menstrual cycle phase may not capture the contribution of hormones to sleep quality.

Neither concurrent progesterone nor rate of increase in progesterone was related to other PSG measures (sleep stages, sleep efficiency, sleep latency, or REM latency) in exploratory analyses. However, we observed a higher percentage of N2 sleep among participants who had experienced an increase in progesterone levels at the time of the PSG relative to those with low progesterone levels, consistent with previous findings of elevated N2 sleep [4, 5] and sleep spindle activity [4] in the luteal phase. Our findings provide additional evidence that the EEG is sensitive to neuro-hormonal changes that occur across the menstrual cycle. While the absence of an association between progesterone levels and REM sleep may appear inconsistent with studies showing decreased REM sleep in the luteal phase [34–36], direct comparison cannot be made because progesterone levels were not reported in prior studies.

Our results show that higher serum estrone, but not estradiol, levels at the time of the PSG are associated with more wakefulness in healthy premenopausal women, although this association was lost for WASO% after adjustment for the progesterone slope, suggesting that luteal-phase sleep disruption is driven primarily by the rate of change in progesterone. The basis for a selective association with estrone is unclear, although some animal studies suggest differential effects of estrone versus estradiol on neurocognitive and other neural functions [37]. Comparisons with human studies showing therapeutic effects of conjugated estrogens on sleep after menopause [17–20], or with animal studies showing increased activity levels [22] and decreased NREM sleep [38] when ovariectomized rodents receive estradiol or 17 beta-estradiol, respectively, are limited because of the different underlying hormonal milieu and type of estrogen administered in each study.

A major strength of our study is the prospective documentation of menstrual cycle timing when hormone levels were drawn and PSG was completed. Future studies may further advance our understanding of the hormone associations with PSG sleep by standardizing the timing of PSG studies according to specific hormone profiles or experimentally controlling the hormonal milieu to isolate the effect of changing levels of each hormone on sleep quality. A limitation of the current study is that we were unable to determine the contribution of the rate of rise of estrogens to premenstrual sleep quality because the interval of time between our two menstrual time points encompassed two distinct increases and decreases in levels of estradiol and estrone. In addition, while use of home PSG is advantageous for eliminating sensitivities to sleeping in the laboratory, it can introduce variability in the home sleeping environment as well as the sleep period time, which we accounted for in our analysis. Finally, because our participants had minimal sleep disturbance and no sleep complaints, our results may underestimate the effect of reproductive hormone dynamics on sleep quality for a sleep-disordered population, to whom our findings may not be generalizable.

In conclusion, a more rapid rate of increase in progesterone levels during the mid-luteal phase may explain why some women report sleep disruption during the mid- through late-luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, particularly during the late luteal phase when they may be sensitive to declining levels of progesterone. Variability in the rate of rise and fall of progesterone between women and between cycles within an individual woman may account for the absence of a universal experience of sleep disturbance during the luteal phase in all premenopausal women across all menstrual cycles. Our findings establish a link between reproductive hormone dynamics and sleep fragmentation in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, and suggest that the progesterone rise occurring in the context of elevated estrogens contributes to premenstrual sleep disruption.

Acknowledgements and Disclosures

The authors thank Susan Regan, PhD for her valuable contributions to this study. This work was supported by 5 R01 MH082922 (HJ) and K23 MH086689 (KMS). HJ receives research funding from NIH and Cephalon/Teva, serves on a consultant for Noven and as an unpaid consultant to Sunovion.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

KMS, SK, and SC have no conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Manber R, Bootzin RR. Sleep and the menstrual cycle. Health Psychol. 1997;16:209–214. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker FC, Driver HS. Self-reported sleep across the menstrual cycle in young, healthy women. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:239–243. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker FC, Waner JI, Vieira EF, Taylor SR, Driver HS, Mitchell D. Sleep and 24 hour body temperatures: a comparison in young men, naturally cycling women and women taking hormonal contraceptives. J Physiol. 2001;530:565–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0565k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Driver HS, Dijk DJ, Werth E, Biedermann K, Borbely AA. Sleep and the sleep electroencephalogram across the menstrual cycle in young healthy women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:728–735. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shechter A, Lesperance P, Ng Ying Kin NM, Boivin DB. Nocturnal polysomnographic sleep across the menstrual cycle in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Sleep medicine. 2012;13:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Driver H, Werth E, Dijk D-J, Borbely A. The menstrual cycle effects on sleep. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2008;3:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker FC, Kahan TL, Trinder J, Colrain IM. Sleep quality and the sleep electroencephalogram in women with severe premenstrual syndrome. Sleep. 2007;30:1283–1291. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farage MA, Neill S, MacLean AB. Physiological changes associated with the menstrual cycle: a review. Obstetrical & gynecological survey. 2009;64:58–72. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181932a37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakayama T, Suzuki M, Ishizuka N. Action of progesterone on preoptic thermosensitive neurones. Nature. 1975;258:80. doi: 10.1038/258080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Someren EJ. More than a marker: interaction between the circadian regulation of temperature and sleep, age-related changes, and treatment possibilities. Chronobiology international. 2000;17:313–354. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100101050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friess E, Tagaya H, Trachsel L, Holsboer F, Rupprecht R. Progesterone-induced changes in sleep in male subjects. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E885–E891. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.5.E885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schussler P, Kluge M, Yassouridis A, Dresler M, Held K, Zihl J, et al. Progesterone reduces wakefulness in sleep EEG and has no effect on cognition in healthy postmenopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:1124–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manber R, Armitage R. Sex, steroids, and sleep: a review. Sleep. 1999;22:540–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deslypere JP, Verdonck L, Vermeulen A. Fat tissue: a steroid reservoir and site of steroid metabolism. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1985;61:564–570. doi: 10.1210/jcem-61-3-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tankersley CG, Nicholas WC, Deaver DR, Mikita D, Kenney WL. Estrogen replacement in middle-aged women: thermoregulatory responses to exercise in the heat. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:1238–1245. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.4.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiff I, Regestein Q, Tulchinsky D, Ryan KJ. Effects of estrogens on sleep and psychological state of hypogonadal women. JAMA. 1979;242:2405–2404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schiff I, Regestein Q, Schinfeld J, Ryan KJ. Interactions of oestrogens and hours of sleep on cortisol, FSH, LH, and prolactin in hypogonadal women. Maturitas. 1980;2:179–183. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(80)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hachul H, Bittencourt LR, Andersen ML, Haidar MA, Baracat EC, Tufik S. Effects of hormone therapy with estrogen and/or progesterone on sleep pattern in postmenopausal women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montplaisir J, Lorrain J, Denesle R, Petit D. Sleep in menopause: differential effects of two forms of hormone replacement therapy. Menopause. 2001;8:10–16. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200101000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polo-Kantola P, Erkkola R, Helenius H, Irjala K, Polo O. When does estrogen replacement therapy improve sleep quality? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70539-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribeiro AC, Pfaff DW, Devidze N. Estradiol modulates behavioral arousal and induces changes in gene expression profiles in brain regions involved in the control of vigilance. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:795–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joffe H, Crawford S, Economou N, Kim S, Regan S, Hall JE, et al. A gonadotropinreleasing hormone agonist model demonstrates that nocturnal hot flashes interrupt objective sleep. Sleep. 2013;36:1977–1985. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stricker R, Eberhart R, Chevailler MC, Quinn FA, Bischof P, Stricker R. Establishment of detailed reference values for luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, estradiol, and progesterone during different phases of the menstrual cycle on the Abbott ARCHITECT analyzer. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine : CCLM / FESCC. 2006;44:883–887. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson RE, Grebe SK, DJ OK, Singh RJ. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay for simultaneous measurement of estradiol and estrone in human plasma. Clinical chemistry. 2004;50:373–384. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.025478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siekmann L. Determination of oestradiol-17 beta in human serum by isotope dilution-mass spectrometry. Definitive methods in clinical chemistry, II. Journal of clinical chemistry and clinical biochemistry Zeitschrift fur klinische Chemie und klinische Biochemie. 1984;22:551–557. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1984.22.8.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weisberg S. Applied Linear Regression. 3rd Edition. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27:1255–1273. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Israel S, Schneller O. The thermogenic property of progesterone. Fertil Steril. 1950;1:53–65. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stachenfeld NS, Silva C, Keefe DL. Estrogen modifies the temperature effects of progesterone. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1643–1649. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.5.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caufriez A, Leproult R, L'Hermite-Baleriaux M, Kerkhofs M, Copinschi G. Progesterone prevents sleep disturbances and modulates GH, TSH, and melatonin secretion in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E614–E623. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soderpalm AH, Lindsey S, Purdy RH, Hauger R, Wit de H. Administration of progesterone produces mild sedative-like effects in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:339–354. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker FC, Driver HS, Rogers GG, Paiker J, Mitchell D. High nocturnal body temperatures and disturbed sleep in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E1013–E1021. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.6.E1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parry BL, Mostofi N, LeVeau B, Nahum HC, Golshan S, Laughlin GA, et al. Sleep EEG studies during early and late partial sleep deprivation in premenstrual dysphoric disorder and normal control subjects. Psychiatry research. 1999;85:127–143. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee KA, Shaver JF, Giblin EC, Woods NF. Sleep patterns related to menstrual cycle phase and premenstrual affective symptoms. Sleep. 1990;13:403–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McClure RE, Barha CK, Galea LA. 17beta-Estradiol, but not estrone, increases the survival and activation of new neurons in the hippocampus in response to spatial memory in adult female rats. Hormones and behavior. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deurveilher S, Rusak B, Semba K. Female reproductive hormones alter sleep architecture in ovariectomized rats. Sleep. 2011;34:519–530. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]