Abstract

Background

Children and adolescents exposed to armed conflict are at high risk of developing mental health problems. To date, a range of psychosocial approaches and clinical/psychiatric interventions has been used to address mental health needs in these groups.

Aims

To provide an overview of peer-reviewed psychosocial and mental health interventions designed to address mental health needs of conflict-affected children, and to highlight areas in which policy and research need strengthening.

Methods

We used standard review methodology to identify interventions aimed at improving or treating mental health problems in conflict-affected youth. An ecological lens was used to organize studies according to the individual, family, peer/school, and community factors targeted by each intervention. Interventions were also evaluated for their orientation toward prevention, treatment, or maintenance, and for the strength of the scientific evidence of reported effects.

Results

Of 2305 studies returned from online searches of the literature and 21 sources identified through bibliography mining, 58 qualified for full review, with 40 peer-reviewed studies included in the final narrative synthesis. Overall, the peer-reviewed literature focused largely on school-based interventions. Very few family and community-based interventions have been empirically evaluated. Only two studies assessed multilevel or stepped-care packages.

Conclusions

The evidence base on effective and efficacious interventions for conflict-affected youth requires strengthening. Postconflict development agendas must be retooled to target the vulnerabilities characterizing conflict-affected youth, and these approaches must be collaborative across bodies responsible for the care of youth and families.

Keywords: ecological, interventions, mental health, psychosocial, war-affected youth

Introduction

In the midst of war, images of children and families caught in the crossfire disturb and motivate action. However, as conflicts subside and media attention turns to the latest breaking emergency, little attention is paid to the longer-term mental health and psychosocial sequelae plaguing conflict-affected children and families. In general, mental health receives limited attention from policymakers and funding agencies, and it is rare for countries under conflict to emerge with a post-conflict development agenda that includes robust attention to mental health services.

Evidence-based intervention principles are vital to adequately address the needs of populations affected by disasters and mass violence.1,2 Experts have pinpointed the following five intervention principles as “essential elements” of immediate and midterm mass trauma interventions, which need to promote (1) a sense of safety, (2) calming, (3) a sense of self-and-community efficacy, (4) connectedness, and (5) hope. Inadequate responsiveness to these issues is especially concerning in view of the body of research documenting increased risk of mental health problems in war-affected children and families.1,3–8

An ecological framework is useful for considering how multilevel interventions can improve long-term mental health and psychosocial well-being. Often cited in this context is the work of Uri Bronfenbrenner. Although he later revised the emphasis of his work, his most cited publication9 emphasizes the importance of the environment in which children grow up, and conceptualizes environmental influences at different nested levels—for example, the individual (ontogenic system), the meso-system, exo-system, and macro-system—depending, for instance, on the amount of direct interaction that a child has with these social systems. Current applications of this theoretical framework with children in adversity have focused on transactions taking place between risk and protective factors at different socio-ecological levels—that is, the family, peer, school, and wider-community levels.10,11 When resources at any level are compromised, the risk of poor developmental outcomes and poor mental health adjustment increases; for example, among children and youth exposed to conflict, adverse mental health outcomes triggered by exposure to horrific events are compounded by war-related damage to the extended support systems (family, social, economic, political) that usually foster healthy child development.3,10,12–17 When resources across the social ecology are more robust (e.g., family and community acceptance, access to school), children can achieve more positive outcomes, even in the face of extreme hardship.18,19 It follows that layers of comprehensive supports, coupled with interventions aimed at rebuilding or strengthening such resources, have the potential to improve children's capacity for resilience and to mitigate the effects of conflict experiences.5,10,18–20

Despite consensus from the Inter-agency Standing Committee Reference Group on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings1 on the importance of a protective environment, this model of holistic intervention is often challenged. Debate continues in both the research and programmatic communities about the prioritization of clinical interventions—that is, psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatments for people suffering from identified mental disorders and associated impairment20—over psychosocial programming—that is, preventive interventions and programming to strengthen protective factors and bolster social contributors to well-being.21,22 Although guidelines commonly argue that the integration of these paradigms can provide services better suited to a continuum of mental health adjustment, a false dichotomy between the two domains persists.20,23 In truth, combined intervention strategies that attend to both prevention/mental health promotion and clinical approaches (targeting individuals with identified mental disorders with evidence-based practices) have consensus support.5

In this article we review the peer-reviewed literature on psychosocial and mental health interventions targeting children and adolescents affected by conflict. To address service gaps resulting from the clinical-psychosocial dichotomy, it is useful to examine the range of existing interventions using an ecological lens. By organizing interventions according to each ecological level's focus, we can gain insight into the similarities and inconsistencies between same-level programs, as well as into the complementarity of interventions across levels. Where available, we refer to research or evaluation efforts that provide an evidence base for intervention effectiveness. Furthermore, we organize interventions according to their orientation toward prevention (i.e., upstream intervention to address risk and protective factors prior to onset of problems), treatment, or maintenance (i.e., interventions to reduce either distress and symptoms or the chance of relapse, respectively).24,25 By organizing the literature according to this framework, we offer a snapshot of current knowledge while highlighting existing gaps.

Methods

Using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses criteria (http://www.prisma-statement.org), we searched PubMed, PsycINFO, and EMBASE for all peer-reviewed publications from 1990 to 2011 that pertain to mental health and psychosocial interventions for conflict- and war-affected children and adolescents. Returns were limited to those that contained keywords within a matrix of relevant terminology identified in the study title or abstract. To this end, the following search terms were utilized: (child(ren) or youth(s) or adolescent(s)) and (war or conflict) and (intervention or program or therapy or treatment) and (mental health or psychosocial or depression or anxiety or posttraumatic stress). Sensitivity of searches was refined by using keywords and the bibliographies of eligible studies identified in the early stages of the search. In addition, we complemented our searches with results from related reviews.

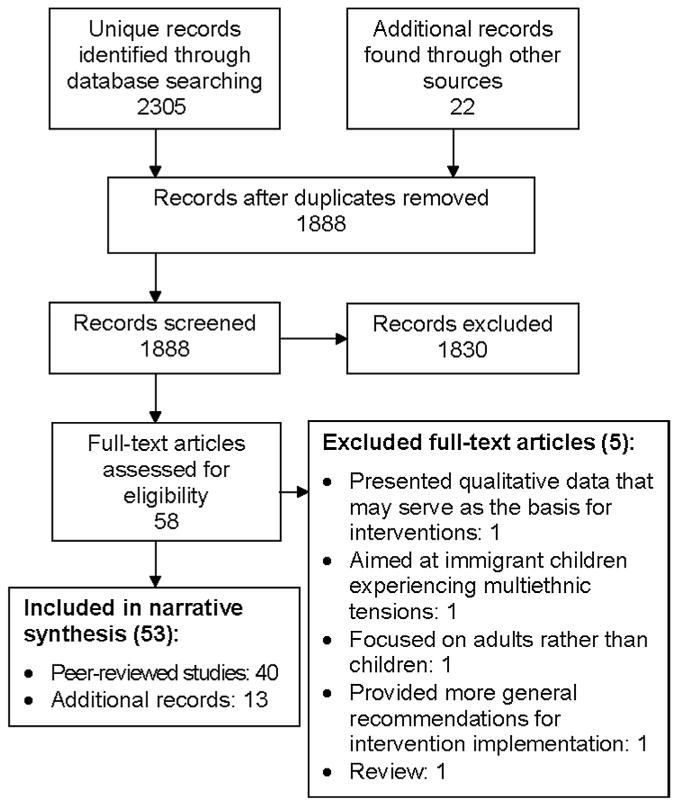

Articles subject to full review were those that adhered to the following criteria: (1) the publication described a psychosocial or mental health intervention (preventive, treatment, or maintenance), (2) children or adolescents were specified as primary recipients of the intervention, (3) mental health and psychosocial outcomes served as the primary outcomes of interest, and (4) the intervention was administered in a postconflict setting or a setting with protracted political violence. Database queries returned a total of 2305 unique studies. Three team members working independently screened each of the abstracts for relevance and excluded those not meeting inclusion criteria (with 95% concordance between team members). Additional records were identified through bibliography mining. Full-text articles were then assessed for eligibility, and a final sample of 40 peer-reviewed studies was identified (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Systematic review following PRISMA standards.

Given large gaps in the peer-reviewed literature—on community-based interventions, in particular—a selection of reviews and reports was also included to provide background information on promising, but untested, interventions of interest. Some programs were also found to have multiple aims (e.g., prevention and treatment) and were therefore listed in different sections of Table 1.

Table 1. Interventions Organized According to Ecological Level and Aim.

| Level | Aims | Program | References | Design | Sample size (boys/girls/total) |

Control group |

Region | Additional comments & notes on cultural adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Prevention | Huggy-puppy intervention | Sadeh et al. (2008)26 | RCT | 106/85/191 | Yes | Israel | Brief intervention for young children (ages 2-7) living in midst of active conflict Intended to facilitate active coping with stress & war experiences & to prevent onset of symptoms Minimal time required on part of physicians/clinicians |

| Psychological first aid | Aulagnier et al. (2004)27 | Descriptive | n/a | n/a | n/a | Modular approach to strengthening mental health in immediate aftermath of disaster or conflict | ||

| Treatment | Trauma-focused CBT | Task Force on Community Preventive Services (2008)28 | Descriptive | n/a | n/a | n/a | CBT trauma-focused treatments are rare, given limited resources for one-on-one treatment | |

| Narrative exposure therapy | Neuner et al. (2008)29 Catani et al. (2010)30 |

Pilot | 14/12/26 | Yes | Rwandan & Somali refugees in Uganda | Primarily focused on traumatic stress reactions Short number of sessions & delivery by laypersons recommended for sustainability Intervention components originally developed for violence-affected populations in Chile |

||

| Onyut et al. (2005)31 | Pilot | 3/3/6 | No | Rwandan & Somali refugees in Uganda | ||||

| Testimonial psychotherapy | Lustig et al. (2004)32 | Descriptive | 3 boys | No | Sudanese refugees in Boston | Feasibility of intervention explored with focus groups prior to implementation; feedback was incorporated into intervention protocol | ||

| Maintenance | Narrative exposure therapy | Neuner et al. (2008)29 | Pilot | 14/12/26 | Yes | Rwandan & Somali refugees in Uganda | Investigations of program's long-term effectiveness show encouraging results | |

| Onyut et al. (2005)31 | Pilot | 3/3/6 | No | Rwandan & Somali refugees in Uganda | ||||

| Family | Prevention | Child tracing | Hepburn (2006)33 Machel (2000)34 |

Descriptive | n/a | n/a | n/a | Family reunification & child tracing help to prevent vulnerability to risks such as hunger, exploitation, & violence Use of traditional cleansing ceremonies & strong integration with local services contribute to successful reintegration of youth Involvement of local staff & community leaders critical in reintegration efforts |

| Verhey (2001)35 Verhey (2002)36 |

Report | n/a | n/a | Angola & El Salvador | ||||

| Williamson (2005)37 | Descriptive | n/a | n/a | Sierra Leone | ||||

| Treatment | Dyad psychosocial support/treatment | Dybdahl (2001)38 | Pre/post | 39/48/97 | Yes | Bosnia | Intervention components were derived from (1) successful techniques used previously in this population & (2) theory-driven treatments used cross-culturally in diverse settings | |

| Multiple-family group intervention | Weine et al. (2005)39 | Pre/post | 30 families | No | Kosovo | Leveraged the traditional Kosovar family structure to build on strengths Strong local collaborations improved cultural acceptability/relevance of intervention Collaborations strengthened local service capacities |

||

| Maintenance | None | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Peer/school | Prevention | Structured activities at NGO sites | Loughry et al. (2006)40 | Pre/post | 150/150/400 | Yes | Palestine | Employed local, young volunteers as providers Emphasis given to cultural & recreational activities |

| Universal school-based interventions | Ager et al. (2011)41 | Cross-sectional follow-up | 210/202/403 | Yes | Uganda | Administered by teachers in a classroom setting to increase feasibility & affordability, & to reduce stigma Universal interventions may be used to identify children in need of more targeted interventions Examination of long-term effectiveness is warranted Further integration in multisectoral interventions & addressing multiple layers of the social ecology may increase effectiveness (see Ager et al. 2011)41 |

||

| Berger (2007)42 | Quasi-RCT | 77/65/142 | Yes | Israel | ||||

| Gelkopf et al. (2009)43 | Pre/post | 114/0/114 | Yes | Israel | ||||

| Slone & Shoshani (2008)44 | Pre/post | 84/97/181 | Yes | Israel | ||||

| Selective or indicated school-based programs | Constandinides et al. (2011)45 | Cross-sectional follow-up | 476/401/877 | Yes | Palestine | Selective or indicated school-based prevention programs are aimed at specific at-risk groups & often have overlapping aims with treatment interventions | ||

| Hasanovic et al. (2009)46 | Cross-sectional follow-up | 141/276/408 | Yes | Bosnia | ||||

| Karam et al. (2008)47 | Cross-sectional follow-up | 99/95/194 | Yes | Lebanon | ||||

| Youth clubs | Ispanovic-Radojkovic et al. (2004)48 | Pre/post | 813/293/1,106 | Yes | Serbia | Youth clubs may contribute to the healing process, but additional intervention may be needed in some individual cases | ||

| Treatment | Group interpersonal psychotherapy & creative play | Bolton et al. (2007)49 | RCT | 134/180/314 | Yes | Uganda | Innovative in its use of locally developed measures for assessing mental health outcomes Interpersonal psychotherapy treatment manual adapted for local use; creative play originally developed for use with war-affected youth |

|

| Dance & movement therapy | Harris (2007)50 | Pre/post | 12/0/12 | No | S. Sudanese & Sierra Leonean diaspora in the United States | Provides a useful therapy for settings where verbal emotional expression is not emphasized | ||

| Mind-body techniques | Staples et al. (2011)51 | Pre/post | 81/48/129 | No | Palestine | Didactic course focused on mediation, biofeedback, drawings, autogenic training, guided imagery, genograms, movement, breathing techniques Administration by nonspecialist teachers recommended feasibility in a pilot study (Gordon et al., 2004)53 and used in RCT |

||

| Gordon et al. (2008)52 | RCT | 20/62/82 | Yes | Kosovo | ||||

| School-based programs for children exhibiting distress | Entholdt et al. (2005)54 | Pilot | 17/9/26 | Yes | United Kingdom | Classroom-based format & delivery by paraprofessionals may be more cost-effective, feasible, & easily integrated within the social-ecological context | ||

| Tol et al. (2008)14 Tol et al. (2010)55 Tol et al. (2012)56 |

RCT | In treatment: 545 Control: 607 |

Yes | Burundi, Indonesia, Sri Lanka | ||||

| Jordans et al. (2010)57 | Cluster RCT | 167/158/325 | Yes | Nepal | ||||

| Skills + psychotherapeutic intervention | Cox et al. (2007)58 | Qualitative | n/a | No | Bosnia | Attended to peer, family, & community-level interactions through sensitization work Collaborated with local counterparts to revise & adapt program to local needs Qualitative analysis provided iterative feedback on program acceptability & sustainability Successfully scaled up in many schools |

||

| Layne et al. (2001)59 Layne et al. (2008)60 |

RCT | 43/84/127 | Yes | Bosnia | ||||

| Vocational training + psychosocial support | Bannink-Mbazzi & Lorschiedter (2009)61 | Descriptive | 51/39/90 | No | Uganda | Provides psychosocial support as needed to any youth enrolled in livelihood training Represents a more integrated approach that avoids singling out specific categories of conflict-affected youth |

||

| Readiness via group therapy + education | Betancourt et al.62 | RCT | Pilot sample: 16/16/32 | No | Sierra Leone | Intervention development entailed use of an exploratory, sequential, mixed-methods study design Group-based intervention linking youth to educational & employment opportunities was recommended The YRI is a feasible & acceptable intervention for war-affected youth; larger RCTs are needed to examine effectiveness and impact on emotion regulation, pro-social skills, & daily functioning |

||

| Teacher-led trauma/grief psychotherapy | Woodside et al. (1999)63 | RCT | 126/125/151 | Yes | Croatia | Close collaboration with local agencies led to development of a culturally relevant training program & manual Feedback from teachers applied to intervention revisions & refinements |

||

| Nonformal education & trauma healing | Gupta & Zimmer (2008)64 | Pre/post | 167/148/315 | No | Sierra Leone | A thorough, multistage translation process attended to cultural sensitivity Locally produced literacy & numeracy modules ensured cultural appropriateness Participant feedback provided further information on intervention acceptability |

||

| Short-term group crisis intervention | Thabet et al. (2005)65 | Pre/post | 60/51/111 | Yes | Palestine | Innovative attempt to treat trauma reactions during ongoing conflict Further adaptation of treatment techniques to increase cultural relevance may be warranted Integration of more cognitive or active tasks recommended by authors |

||

| Maintenance | Universal school-based interventions | Constandinides et al. (2011)45 | Cross-sectional follow-up | 476/401/877 | Yes | Palestine | Preliminary results indicate at least four years durability of effects in Palestine study | |

| Community | Sensitization campaigns | Barenbaum et al. (2004)3 | Descriptive | n/a | n/a | n/a | Community outreach may help prevent stigma & improve community acceptance of conflict-affected children | |

| Mass media | Lamberg (2004)66 Wessells (1996)67 Bonati (1997)68 Tam-Baryoh (2009)69 |

Descriptive/report | n/a | n/a | n/a | Media programs/radio used broadly to deliver psychoeducation to communities New research should investigate effects of these interventions on psychosocial well-being |

||

| Purification rituals & addressing evil spirits | Stark (2006)70 Reynolds (1996)71 Honwana (1998)72 |

Descriptive/report | n/a | n/a | n/a | Collaboration with religious & traditional healers may help bridge the gap between cultural norms & Western-derived treatments | ||

| Social dialogue | Wessells (2004)73 Wessells (2007)23 |

Report | n/a | n/a | n/a | Used participatory methods to encourage dialogue about traditional healing Worked with participants to blend Western & traditional approaches to trauma healing |

||

| Reconciliation committees | Swartz & Drennan (2000)74 Richters et al. (2005)75 Pouligny et al. (2007)76 |

Descriptive/report | n/a | n/a | n/a | Further research is needed to investigate the preventive effects of reconciliation committees on youth | ||

| Community-based rehabilitation | International Labour Organisation et al. (2004)77 | Report | n/a | n/a | n/a | Engages communities, families, & organizations in attending to the physical & mental capacities of disabled community members May serve as a useful model for future research |

||

| Multilevel | Stepped care | Care package | Jordans et al. (2011)78 | Monitoring & evaluation | CBI: 24,690 Counseling: 1 705 Referrals: 571 |

No | Burundi, Sudan, Sri Lanka, Indonesia | Five levels: Mental health promotion for population at large Preventive, resilience-focused group activities Classroom-based intervention for subgroups Counseling of subgroups by paraprofessionals Specialized individual psychiatric treatment |

| Multilevel intervention | Mohlen et al. (2005)79 | Pre/post | 6/4/10 | No | Kosovan & Roma refugees in Germany | Unique blend of individual, group, & family-level activities Delivery by laypersons should be investigated |

CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; NGO, nongovernmental organization; RCT, randomized, controlled trial; YRI, Youth Readiness Intervention.

Results

Of the 1888 unique abstracts identified in the initial search, 58 were agreed upon by team members as meriting full review. Of these, 5 were excluded for failing to meet the study criteria. The remaining studies are reviewed and summarized in Table 1.

Overall, we found diverse forms of psychosocial intervention for conflict-affected children, youth, and families, ranging from individualized narrative exposure therapy to broad-based community-sensitization campaigns. Below, we discuss each intervention in further detail. A discussion of trends and gaps in the literature, along with recommendations for directions in future research, follows.

Individual-Level Interventions: Prevention

Huggy-puppy intervention

This review identified only one intervention in the peer-reviewed literature aimed at preventing mental health symptoms in war-affected children. In Israel, researchers investigated the effects of the huggy-puppy intervention among young children (ages 2–7) living in refugee camps during active conflict.26 In this brief intervention derived from theories on child development and psychopathological processes, children are presented with a stuffed puppy doll that is “far away from his home and does not have any friends … He likes to be hugged but has no one to take care of him.” Participating children who agree to befriend the puppy are taught how to hug the doll and encouraged to focus on being a responsible caretaker.

In randomized trials of the huggy-puppy intervention in Israel, pre/post-intervention parent-report assessments indicated that it had strong positive effects on symptoms of traumatic stress reactions.26 Significant correlations between child adherence to the intervention, child attachment to the doll, and improvements in well-being were observed. Additional research is needed to examine intervention mechanisms, but initial results suggest that the intervention may be implemented early on during conflict as a preventive measure.

Psychological first aid

Recently, growing attention has been given to individual psychological first aid, which is an intervention aimed at strengthening mental health outcomes in the immediate aftermath of a disaster or conflict. Recently, the World Health Organization has published guidelines on psychological first aid. In essence, this guide focuses on the intervention as a supportive, nonintrusive form of interaction that aims to provide practical assistance where possible, connect people with existing supports, and identify those in need for more specialized services. Although psychological first aid is recommended by international consensus-based humanitarian guidelines,80 no rigorous (i.e., systematically evaluated) evidence is available concerning this form of psychological support for use among children and adolescents affected by war.81 Importantly, this intervention is separate from the trauma-focused practice of psychological debriefing, which has been demonstrated to be ineffective and, in adults, even harmful in some cases.27,28

Individual-Level Interventions: Treatment

Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy

In high-income settings, individual trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy is one of the interventions with a sufficient evidence base to be a recommended practice.28 In war zones, however, such individualized treatment approaches are not commonly implemented, given the resources required, the lack of specialized mental health professionals, the low prioritization of mental health, and the stigma that is associated with mental health problems.

Narrative exposure therapy

Narrative exposure therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is typically delivered as a short-term individual treatment by experienced mental health clinicians. This form of therapy is an intervention based on cognitive-behavioral exposure therapy for treating PTSD symptoms. It adapts the classical form of exposure therapy to meet the needs of traumatized survivors of war and torture. Instead of defining a single event as a target in therapy, the patient constructs a narration about his whole life from birth up to the present situation while focusing on the detailed exploration of the traumatic experiences and traumatic memories. Narrative exposure therapy has been adapted for war-affected adolescents and children aged 12 to 17 years (KidNET) presenting with multiple war trauma exposures and meeting moderate to severe criteria for PTSD.82 In a study in Germany, significant improvements in PTSD symptoms were demonstrated among eastern European refugee children enrolled in KidNET.30 Lasting and strong effects of KidNET have been observed in research with war-affected youth orphaned in the Rwandan genocide; in this trial, KidNET performed as well as flexible trauma counseling administered at the discretion of lay counselors.29 Significant reductions in PTSD symptoms and improvements in functioning were also observed in a small trial of KidNET with war-affected children in Sri Lanka (KidNET performed similarly to meditation therapy).30

Few studies have investigated the maintenance of individual treatment gains over time. In a small pilot study of KidNET, participants demonstrated sustained treatment effects at a nine-month follow-up,31 but further research is needed on the efficacy of KidNET in treating PTSD; in other settings, long-term results of narrative exposure therapy with adults have been mixed.83 Further, while KidNET may have long-term effects in alleviating PTSD symptoms, more research is needed on maintenance interventions that involve ongoing treatment rather than on the potentially sustained benefits of prior interventions.

Testimonial psychotherapy

In testimonial psychotherapy, patient narratives of past traumatic events are recorded and then reviewed by the patient and a clinician for links between personal experiences and the social and political aspects of trauma. Case studies of the intervention as used with Sudanese refugees indicate that testimonials may serve as a useful alternative to traditional psychotherapy approaches, which may be stigmatizing, uncommon, or culturally irrelevant among some populations.32 Evidence of intervention efficacy or effectiveness with war-affected children has not been published.

Family-Level Interventions: Prevention

A strong evidence base supports the claim that secure and consistent caregiving relationships are critical in order for children to weather the extreme stressors of war and conflict.84–91 As a result, a number of psychosocial interventions are oriented toward the family, with the aim of strengthening parent-child relationships and connection.

For some children, war may impose prolonged separations from, and loss of, loved ones.92,93 Although few child-tracing interventions have been formally evaluated for effectiveness in improving mental health outcomes, reunification of separated families is often an important first step in promoting mental health in war zones.94,95 A number of interventions are available for preventing separation (e.g., universal registration at birth, registration during movements, computer-assisted databases), providing interim and durable care options (e.g., foster care, peer-group care),33,34 and reunifying families (e.g., tracing separated children, reintegrating child soldiers).35–37,96,97 To date, however, studies demonstrating significant associations between child tracing, family reunification, and psychosocial adjustment have not been published in the peer-reviewed literature.

Family-Level Interventions: Treatment

Dyad psychosocial support

A five-month trial in Bosnia compared effects of a short-term, group-based psychosocial treatment for mother-child dyads to a control condition comprising free medical care only.38 The intervention, designed by the International Child Development Programme,98 included treatment components derived from successful techniques used previously in the Bosnian population as well as theory-driven treatments used in a number of other settings. Pre/post-intervention results suggested modest positive effects on maternal mental health, children's weight gain, and children's psychosocial functioning and mental health. Study limitations included lack of involvement of male care-givers, a small intervention sample size (n = 87 dyads), and difficult environmental conditions that posed challenges for intervention delivery.

Multiple-family group intervention

A multiple-family group intervention that also included individual home visits was piloted with 30 families living with severe mental illness in postwar Kosovo.39 Families participated in seven sessions of psychoeducation about chronic mental illness—led by a local psychiatrist and nurse and supervised by trained local services teams and American study consultants. The therapy aimed to increase compliance with psychiatric medication among war-affected individuals in treatment and to improve mental health service use among families. Discussions in group sessions addressed the following topics: psychoeducation; medication use and side effects; psychosocial causes and effects of relapse; problem solving in response to symptoms; responding to crises; accessing professional mental health services; and building resilience. Findings indicated positive effects on both outcomes, although additional information related to child mental health outcomes would have strengthened the study design. This study used a collaborative approach to delivery, including close work with Kosovar partners.

Family-Level Interventions: Maintenance

None of the research on family-based interventions for conflict- and war-affected populations has investigated the maintenance of effects over the longer term. This topic remains an important target for future research efforts.

Peer- and School-Based Interventions: Prevention

Although many schools in high-resource settings have implemented programs with the primary aim of prevention, few such interventions have been implemented and evaluated in low-and middle-income settings affected by armed conflict.99 Within the school setting, interventions can be aimed at preventing mental health problems in all children in the school (i.e., a universal approach) or aimed at specific at-risk groups (i.e., selective and indicated prevention, which often have overlapping aims with treatment interventions). Our search identified only a handful of prevention-oriented studies.

Structured activities at nongovernmental organization sites

In a yearlong, nonrandomized trial involving a sample from the Palestinian Territories, researchers assessed the effects that structured activities at nongovernmental organization sites had on child mental health (internalizing and externalizing), child hopefulness, and parental support.40 Structured activities included traditional dance, art, sports, drama, and puppetry. This combination of activities was hypothesized to (1) assist emotional adjustment in hostile environments by providing routine, constructive engagement and opportunities for attachment and expression, (2) positively affect parent-child relations by providing safe, shared outdoor activities, and (3) increase children's future orientation. Special emphasis was placed on ensuring a culturally appropriate community focus, which entailed the translation of all materials to the local language, the employment of local volunteers as providers, the implementation of cultural activities, and the use of the community center as the focal location for all activities. Child participants demonstrated improved internalizing/externalizing outcomes when compared to a small control arm; improvements in hopefulness were not observed; improvements in parental support were reported at one of the sites involved.

Universal school-based programs

Universal school-based programs for war-affected children have been piloted in several contexts, although intervention effects have been largely evaluated through cross-sectional follow-up studies.

In Uganda, researchers investigated effects of a school-based intervention that progresses through 15 structured sessions, incorporating play therapy, drama, art, and movement to increase feelings of stability and to improve emotional outcomes.41 Notably, psychosocial structured activities are integrated with community service opportunities and parental engagement in order to attend to multiple levels of ecological needs. In a cross-sectional follow-up study of intervention participants versus community controls, researchers observed that improvements in child well-being were significant among those assigned to the intervention arm, with group assignment and age reported as significant predictors of child-reported well-being. Parent and teacher reports suggested that girls may benefit more from the intervention than boys.

A similar school-based intervention (named Overshadowing the Threat of Terrorism) to reduce PTSD, functional impairment, somatic complaints, and anxiety was tested among children whose schools had sustained repeated terror attacks in Israel.42 This universal intervention involves cognitive-behavioral components, art therapy techniques, body-oriented strategies, and narrative approaches to document children's experiences. The quasi-randomized design assigned 70 students to the intervention and 72 to a waitlisted control, and was implemented by trained teachers over eight 90-minute sessions. Parents and families participated via homework assignments and during two psychoeducation sessions. Positive treatment effects were found on all outcomes of interest.

Finally, we identified two preventive school-based interventions (both piloted in Israel) that focused on developing resiliency as a mechanism for addressing mental health. The first (named ERASE-Stress) uses psychoeducation and skill training with meditative and narrative practices to re-process traumatic experiences and boost self-esteem and access to social supports.43 The second is a primary prevention intervention that focuses on amplifying three factors—social support, self-efficacy, and meaning attribution—to moderate psychological distress.44 In research trials, both interventions were implemented as universal, classroom-based programs. Significant intervention effects in moderating psychological distress were observed as compared to control groups in both studies.

Selective or indicated school-based programs

Cross-sectional analyses of a school-based psychosocial intervention implemented with children in Gaza during an active conflict period focused on positive aspects of well-being, such as good family and community relationships, trust, problem solving, and hope.45 Results from this study indicated significant positive effects of the intervention, with durability of at least four years (despite lower effectiveness in one subgroup assessed two years post-intervention).

In Bosnia, a cross-sectional follow-up study found that symptom severity and cluster symptoms—especially in reexperiencing and avoidance—were significantly reduced among students who participated in a schoolwide trauma-reduction project, as compared to controls.46

By contrast, in a cross-sectional follow-up study comparing intervention participants to community controls in Lebanon, no positive effects were observed among children who received a school-based intervention combining cognitive-behavioral treatment strategies with activities like drawing, creative play, and group discussion.47

Youth clubs

In Serbia, youth clubs have been widely implemented in boarding schools and youth hostels, and include a wide range of participant-directed activities, including communal games, poetry, guest speakers, drama, and group debate. In one study of youth from a boarding high school where youth clubs are active, researchers evaluated the impact of clubs on psychological symptoms in 128 youth club participants as compared to 978 controls.48 Significant increases in self-respect were registered in youth club participants, as were decreases in withdrawal and anxiety in boys and withdrawal and social problems in girls. Non-refugees reported improvements in traumatic stress (this effect was not observed among refugees).

Peer- and School-Based Interventions: Treatment

Group interpersonal psychotherapy and creative play

In a three-arm, randomized, controlled trial (RCT) to reduce depression symptoms in war-affected youth from northern Uganda, researchers compared outcomes among adolescents enrolled in (1) an adapted group interpersonal psychotherapy, (2) a creative play intervention, and (3) a wait-list control group.49 All participants were screened for high depression scores and some impairment at baseline using locally derived and validated mental health assessments. Results from this randomized design indicated that the adapted group interpersonal psychotherapy had positive effects on locally relevant mood disorders, particularly among young women. Creative play was not associated with improvements in mental health or functioning, although the authors indicated that the timing of the assessments may have limited the ability to see longer-term improvements in functioning. Though not part of the study, an assessment of broader psychosocial outcomes such as interpersonal skills, self-esteem, or problem solving may have been better aligned with the goals of the creative condition.

School-based programs for children exhibiting distress

School-based cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for children exhibiting mental health symptoms has been used in trials with groups of war-affected refugees and asylum seekers in the United Kingdom.54 When compared to controls, children enrolled in CBT showed significant improvements in PTSD, behavioral problems, and emotional symptoms, although gains were not retained at two months post-intervention.

Positive effects of a classroom-based intervention have been observed in several rigorous cluster, randomized trials with war-affected children aged 8 to 12 years.14 Implemented by trained community paraprofessionals, this intervention is delivered in 15 manualized, school-based sessions over five weeks. Sessions included trauma-processing activities, cooperative play, and creative expressive elements. In Indonesia, a promising level of effectiveness was demonstrated among participants screened for PTSD and anxiety. Female participants exhibited improved PTSD symptoms and reduced functional impairment. Both males and females maintained their levels of hope. No effects on anxiety, depression, or PTSD-like symptoms were observed among male or female participants.14 Larger improvements in play social support (social support for emotional problems through playing with others) were associated with smaller improvements in PTSD symptoms.55

In Nepal, the same classroom-based intervention was not associated with any main effects, but girls receiving the intervention improved on pro-social behavior, boys improved on psychological difficulties and aggression, and older children displayed an increased sense of hope compared to those in a wait-list control group.57 In Burundi and Sri Lanka, treatment effects were less robust.12,56

Dance and movement therapy

The effects of dance and movement therapy have been studied in war-torn Sierra Leone among males aged 15 to 18 years.50,100 In this therapy, sixteen 2–3 hour sessions of therapy combined with improvisational dance to Sierra Leonean pop music aimed to build self-confidence and improve emotional regulation in participants. The therapy culminated in a public, 25-minute role-play in which the capture, perpetration, and suffering of children and their communities during the war were reenacted. Assessments of traumatic histories, posttraumatic psychosocial problems (aggressive behavior, depression, anxiety, intrusive recollections, and elevated arousal) were conducted at the time of enrollment and at four points thereafter (one, three, six, and twelve months). Data on sustained effects of dance and movement therapy on the outcomes investigated have yet to be published, but qualitative reports have indicated good feasibility in this postwar context.

Mind-body techniques

Positive effects of mind-body techniques for reducing PTSD were investigated among children and adolescent Kosovar refugees in Gaza51 and in high-school students in postwar Kosovo.52 In this treatment, a six-week (three hours weekly) intervention is administered by trained, nonspecialist teachers. Treatment components include meditation, biofeedback, drawing, autogenic training (a self-relaxation technique to produce a psychophysiologically determined relaxation response), guided imagery, genograms, movement, and breathing techniques as tactics for reducing PTSD symptoms. In an RCT of the intervention, 82 adolescents meeting criteria for PTSD were randomly assigned to an immediate-intervention group or a delayed-intervention (wait-list control) group. Significant decreases in PTSD symptoms were found across the sample at post-test, with those students in the immediate-intervention group reporting more dramatic positive effects. While the RCT conducted among high-school students in postwar Kosovo did have a wait-list control group, a significant limitation of the study conducted among children and adolescent Kosovo refugees in Gaza was the lack of a control group.

Skills + psychoeducation intervention

A structured, 17- session psychoeducation and skills program was piloted with promising effects among war-traumatized Bosnian adolescents.58–60 In an RCT, this school-based psycho-therapeutic group intervention was implemented by local school counselors. One hundred twenty-seven war-exposed secondary school students participated in the study. Significant reductions in PTSD and depressive symptoms, as well as improvements in maladaptive grief, were perceived among intervention participants as compared to an active-treatment comparison group that did not participate in the intervention. Results from the study suggest that classroom-based programs that combine psychoeducation, skills building, and supportive counselor contact may be adequate to reduce distress in war-exposed youths living in low-resource settings.

Vocational training + psychosocial support intervention

In northern Uganda, an educational intervention to provide vocational training and as-needed psychosocial support has been evaluated through qualitative inquiry.61 In this program, psychosocial support is provided to youth who score above threshold on an assessment of psychosocial distress. The psychosocial support includes counseling in coping strategies and in cognitive and behavioral methods, as well as facilitating referrals for youth who require additional follow-up. The intervention aims to provide an integrated approach for all war-affected youth desiring livelihood opportunities, including youth with increased need for mental health support. Findings from the intervention showed that most psychological distress for youth—including sleeping problems, psychosomatic symptoms, and worries about family, future, and income—can be ameliorated by providing psychosocial support for students and teachers, in this case by counselors with a wide range of training backgrounds, from short-term certificate training from local organizations to full university master's degrees. Mental health support, such as counseling vulnerable youth and training teachers to provide psychosocial support to students, should be incorporated into general health services and programs.

Readiness via group therapy + education

In Sierra Leone, an RCT is presently taking place to assess the ability of a Youth Readiness Intervention to decrease problems with emotion regulation/anger and general psychological distress and to improve pro-social/adaptive skills and daily functioning among war-affected male and female youth (ages 15–24, per the UN definition of youth). The intervention integrates common practice elements derived mainly from CBT (i.e., psychoeducation, behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, and sequential problem solving) and group interpersonal psychotherapy (i.e., addressing interpersonal deficits and building social support). Initial results of an open trial indicate reliable change across all outcomes investigated.62 Limitations of the study include the lack of a control group; however, a larger RCT that includes a wait-list control group is currently under way. Future iterations of this research also plan to investigate the degree to which the intervention facilitates successful transitions to educational and employment programs for troubled youth in postconflict settings.

Teacher-led trauma/grief psychotherapy

A school-based curriculum to reduce psychosocial trauma and promote social healing in war-affected children from Croatia also demonstrated positive results.63 In this study, teachers received training in the form of trauma/grief-focused psychotherapy developed in partnership with local social workers and psychologists. Weekly group sessions were conducted with the intervention group over a four-month period. Pre/post-assessments, including a one-year follow-up, examined levels of PTSD, self-worth, conflict resolution, social skills, psychosocial well-being, ethnic bias, and academic achievement. Results revealed a small, but significant, reduction in ethnic bias and a reduction of stress symptoms in the intervention group as compared to two control groups, with more positive effects on self-esteem observed among girls. Participants exhibited an increased positive perception of Serbs. No significant correlations were found between trauma exposure, trauma symptoms, and social distance (also called ethnic bias: the degree of one's acceptance of the actions of other ethnic groups). Investigators proposed that future studies account for measures of parental attitudes. They also suggested that ethnic reconciliation may begin in school but is likely tempered by the degree of community buy-in. Potential confounding variables such as participant maturation, exposure to media, parental attitudes toward reconciliation, and the gender of trainers (all of whom were female) were cited as study limitations. These limitations suggest that the study could be improved by clear delineation and planning of variables to be controlled for in this context.

Nonformal education + trauma healing

Rapid-Ed is a four-week intervention targeting both educational needs and trauma healing. It was used in a trial of Sierra Leonean war-affected youth, aged 8 to 18 years, 9–12 months after the 1999 invasion of the capital city by the Revolutionary United Front rebel group. A total of 315 displaced children from two camps for internally displaced persons participated in Rapid-Ed. The intervention includes non-formal educational activities such as literacy and numeracy modules and a trauma-healing module that includes group sharing about past war experiences, psychoeducation regarding responses to trauma, discussion of positive memories before the war, and recreational activities.64 A noncontrolled pilot study of Rapid-Ed was conducted in Sierra Leone over four weeks with biweekly, hourlong sessions. The treatment, designed in close consultation with Sierra Leone's Ministry of Education, was implemented by camp teachers who received six hours of training in the program. At post-test, participants displayed decreased intrusion and arousal symptoms, but increased avoidance symptoms. Study investigators hypothesized that this increase could be attributed to a temporary defense mechanism for dealing with daily stressors in an acute postconflict situation. However, the lack of a control group remains an important limitation of the study.

Short-term group crisis intervention

In a trial using a robust design among children affected by conflict in the Gaza Strip, participants aged 9 to 15 years presenting with PTSD symptoms were assigned without randomization to one of three study arms: (1) a seven-session group intervention that included drawing, free play, storytelling, and expression of feelings, (2) a four-session education intervention, and (3) a control group.65 At a three-month follow-up, neither intervention was found to have significant effects on children's PTSD or depression symptoms. Study limitations included a small sample size (total n = 147), the lack of randomization, an absence of parental involvement in the interventions, and failure to account for war events experienced during the intervention period. Investigators hypothesized that the lack of significant effects could also partially be explained by the intervention's use of “non-active” components, which do not necessarily help children explore and come to terms with difficult experiences or emotions.

Peer- and School-Based Interventions: Maintenance

We did not identify any studies that sought to reduce relapses or recurrences of conflict- or war-related psychosocial and mental health problems in a peer- or school-based setting. One study of a school-based psychosocial intervention in Gaza observed long-term positive effects at up to four years post-intervention, but study authors identified a need for more research on the intervention's longitudinal effects beyond this point of follow-up.45

Community-Level Interventions

A number of studies suggest that the degree to which community support increases over time plays an important ameliorative role for conflict- and war-affected children.16,97,101,102 This review did not identify any evaluations of community-level interventions whose primary goal was to reduce psychological distress and prevent or treat mental disorders in children. However, given the importance of community support, we describe here several processes that activate and strengthen social networks, bolster traditional supports, and create child-friendly spaces, as such interventions may help to promote individual well-being and may prevent, or even provide some elements of effective treatment for, mental disorders in children.

Sensitization campaigns and programming

Sensitization campaigns about war-related mental health difficulties and community outreach to advocate good preventive practices have been incorporated into some psychosocial programs for children.3 These interventions have the potential to raise awareness of mental health at the community level and to reduce stigma around mental health problems in youth.103 In Angola, researchers have piloted a grassroots program to restore social structures and practices in the communities affected by war.73 The intervention included sensitization dialogues with community groups around children's problems, training seminars for community leaders who subsequently advocated for children's needs, activities to encourage emotional expression in a supportive group context, and physical reconstruction of village buildings (e.g., schools, community huts). Participating adults felt that the project helped strengthen the community's local protective processes, but no systematic, quantitative evaluation was conducted.

Mass media

Mass media, including radio and television, have been innovatively applied to deliver messages of healing and reconciliation to large numbers of people.66 In Angola and Mozambique, radio programs have been used to deliver psychoeducation to the public through narrating, in a series of chapters, the stories and experiences of war-affected children.67,68 In other countries, media programs have been developed and broadcast by young people. For instance, in postconflict Sierra Leone, the “Talking Drum Studio” prepares weekly, youth-led radio broadcasts that contain music, news stories, and other information of interest to youth listeners. They are intended to model positive youth leadership and to help guide youth struggling to navigate the difficult postconflict environment.69

As social media networks expand in low-and middle-income countries, many opportunities will develop for examining the psychosocial impact of online programming.

Community-level efforts to address healing

In many settings, traditional healing practices make critical contributions to social healing in the context of war.70,104–106 For instance, in Zimbabwe, Zezuru healers are known to engage family and community members in groups, draw out concerns over children's problems, facilitate reconciliation in and between families, and create a restorative climate.71 Similarly, in Angola, researchers have observed how traditional cleansing rituals facilitate the reintegration of war-affected youth through forgiveness of past transgressions.72 Such research emphasizes the importance of interventions already in use within affected communities.13,104–107 To date, however, most research on traditional healing/cleansing ceremonies has been descriptive. No systematic evaluations have examined the degree to which communities and traditional healing interventions are associated with improvements in mental health in war-affected children and adolescents.

Reconciliation committees

Modern warfare goes hand in hand with mass human rights violations within civilian populations.108,109 Consequently, increased attention is being placed on reconciliation efforts that can address damaged social relations and human rights violations through judicial processes, and thus promote psychological healing at a macro level.74 Truth and reconciliation commissions have been a part of national reconciliation efforts in a number of settings, including East Timor, Peru, Sierra Leone, and South Africa. In Rwanda, a state-orchestrated attempt at reconciliation between ethnic groups employed traditional gacaca justice mechanisms.75

Unfortunately, the meager evidence available suggests that reconciliation processes are not necessarily associated with improved mental health status.110–112 In addition, such approaches have been critiqued for their lack of engagement with social change at the grassroots level.76 Further research that attempts to address the possible preventive effects of transitional justice mechanisms on social relationships and population mental health is clearly needed.

Community-based rehabilitation

Although our review found no community interventions aimed at maintaining well-being or preventing relapse in war-affected children, community-based rehabilitation—a consensus strategy supported by the International Labour Organization, World Health Organization, and the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization—may serve as a useful model for future research. This broad intervention is intended to promote teamwork between families, organizations, and communities to ensure that people with disabilities can maximize their physical and mental capacities and contribute to community life.77 Because disability can serve as a unifying force among opposing factions, community-based rehabilitation has particular relevance to peace building in conflicts characterized by entrenched divisions based on racial, ethnic, and religious differences.113 For example, in Sri Lanka, this approach was used to bring together warring Sinhalese military and Tamil groups in educational workshops on child developmental disabilities such as polio, blindness, and stroke. These programs exposed both groups to the commonalities of the disability experience and promoted mutual assistance between them. Such community-level interventions aimed at raising awareness, building empathy, and combating stigma about mental and cognitive disabilities have significant potential to benefit war-affected children, families, and communities, and merit much more effort in program evaluation.

Multilevel Interventions

In this review, only two multilevel interventions were identified in the peer-reviewed literature. The first used a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation framework to assess a multilevel, stepped-care package in four war-affected countries (Burundi, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Sudan).78 The community-based package included interventions ranging from population-level psychoeducation to specialized referrals for children in need of psychiatric services. Primary prevention activities included building social support through group activities; a secondary preventive, classroom-based intervention was aimed at children with distress; individual psycho-social counseling was offered to those with more severe problems; and available psychiatric services were mapped to facilitate referrals. Across all settings, almost 30,000 child beneficiaries expressed high levels of satisfaction; the authors recommended that reducing costs and the burdens upon therapists may help to increase sustainability.

In a pilot study with child and adolescent Kosovan refugees in Germany, researchers evaluated effects of a treatment that blended individual sessions, group sessions, family sessions, and parent-only sessions.79 Both past traumatic experiences and current daily hardships were addressed. Creative techniques and psychoeducation were also incorporated. Post-intervention results showed significant declines in PTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms among participants; nine out of ten scored higher on psychosocial functioning measures. Although no control group was used in this small trial, preliminary results are promising and should provoke further analysis of blended, multilevel interventions and more use of robust evaluation designs, including the use of control groups.

Discussion

From our review, it is clear that—despite promising progress in the rigorous evaluation of programs—large gaps exist in our knowledge regarding the effectiveness of psychosocial and mental health interventions for war-affected children, adolescents, and youth. Here, we discuss a number of key themes characterizing the existing evidence base and provide recommendations for future research.

Research on Prevention and Maintenance Is Lacking

Across the different levels of children's social ecology—from the individual to the family, peer, and community levels—insufficient evidence is available to guide interventionists in designing preventive and maintenance interventions. Preventive interventions have a high potential for increasing the productivity of countries emerging from conflict and have received increased attention for use in high-risk groups such as children of depressed caregivers or those living in extreme poverty.25,114–116 That said, the interventions highlighted in this review—psychological first aid, family reunification, and structured recreational activities with peers—represent a mere fraction of the possible preventive efforts that may be implemented in war-affected settings. In such settings, although individual approaches to prevention may be limited because of their resource-intensive nature, interventions that leverage existing protective constructs related to social support, coping, supporting healthy parenting, and other resources hold promise.117 In particular, growing attention is being given to early childhood development programs for young children in adversity. Such investments have demonstrated the capacity, in the long run, to improve productivity and reduce social problems among at-risk groups.118

Similarly, the available research is characterized by a lack of attention to the preservation, over time, of treatment effects. Although many studies have focused on reducing distress—for example, in the forms of symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety—little is known about the longer-term effectiveness of psychotherapeutic approaches. Longitudinal research on children affected by war indicates that recovery from the trauma of ecological disruption, loss, and exposure to violence is a developmental process and that interventions initiated at one time point may need to be revisited as the children grow older.16,119–121 However, although the Inter-agency Standing Committee guidelines prescribe sustained care for individuals with mental health issues,5 the degree to which initial benefits are retained and to which relapses occur in war-affected, low-resource settings is not known. For instance, in one study of a school-based group intervention based on CBT, intervention effects were not maintained in the absence of treatment, even two months post-intervention.54

These realities have implications for partnerships and entail the development of medium- and long-term plans for providing care outside of short-term humanitarian interventions.81 In higher-resource settings, researchers have observed positive effects of phased approaches for disaster-affected children; for example, in Hawaii, treatment “non-responders” (defined as children demonstrating sustained, clinical levels of PTSD in the year following their completion of a brief psychosocial intervention) were enrolled in additional sessions of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, with significant positive improvements in PTSD, depression, and anxiety following treatment.122 Studies like this one highlight the potential of approaches that begin with broad-based stabilizing interventions for all war-affected children but that move toward increasingly specialized treatments for those children who do not respond to general treatment approaches (i.e., a stepped-care model; see Table 1). An additional promising element of interventions to maintain improvements over time is that they provide an ongoing opportunity to build capacity and strengthen systems. Depending on how emergency interventions are delivered, these programs can help to build or augment sustainable systems of care and to establish mechanisms for training, supervision, and sustained employment of mental health workers serving war-affected youth. When systems used are ad hoc and incapable of being sustained beyond the emergency period, an opportunity is lost.81,123,124

Few Treatments Integrate Individual, Family, Peer, and Community Components

Promising evidence of intervention efficacy is emerging with regard to treatment, especially in school-based interventions and peer-to-peer processes. These findings reflect trends in high- and middle-income settings, where school-based interventions (specifically, group-based cognitive-behavioral programs) have become increasingly popular.28,125 It is important to recognize, however, that school-based interventions alone might not be sufficient to address the full range of psychological and social problems associated with continued political instability, poverty, and limited access to school in conflict settings.14,49,121 Since the gains made to psychosocial well-being in a short, school-based program may not be sustainable without additional changes in familial, peer, and community supports, further integration of these interventions within family- and community-based models is well warranted, as are strategies to reduce poverty and social/political conflict and to improve employment opportunities and educational access.12,13,126

PTSD Interventions May Not Sufficiently Address Comorbidity

The reality of polyvictimization and the resultant comorbidity of mental health problems among war-affected children must be recognized. Because war brings with it a host of stressors—resulting from direct injury, exposure to loss, and even active involvement in perpetuating violence—the presentation of emotional, behavioral, and social consequences can be complex.127 Treatments focused on single disorders may therefore have limited application; what is likely needed, instead, is a stepped-care model that entails treatment components for multiple types of psychological problems,59,88,128 including acute psychiatric problems.

Epidemiological work on child mental health in conflict- and war-affected settings can provide a deeper understanding not only of equifinality—the processes by which different war exposures may manifest in a similar set of symptoms and impairments—but of key outcome mediators (e.g., social supports, coping skills, emotion-regulation skills) and treatment moderators (e.g., age, gender, ongoing insecurity). A better understanding of these factors can help to guide future intervention research and also to create better-targeted interventions, including the selection of treatment or prevention components with cross-cutting applicability to common symptoms (e.g., traumatic stress reactions, hopelessness, and social deficits).129

Sustainability and Cost-Effectiveness Are Important Considerations

The findings of this review imply that task-shifting and cost-saving innovations can be applied at multiple levels of intervention for war-affected children, youth, and families. Such models, if carefully crafted with high-quality training and supervision, may go a long way in overcoming some of the human-resources problems that characterize low-income and conflict-affected settings. In the reviewed studies, group-based interventions demonstrated better cost-effectiveness and potential for sustainability in school and community settings.130 In Kosovo, even multiple-family groups were shown to be feasible, which has tremendous promise for future cost-effective interventions that may be made across the social ecology.39

Highly trained mental health professionals, where available, can play an important role in developing a continuum of care by providing training and supervision, and by managing the more complex and acute cases. In many war-affected countries, however, this professional workforce alone is insufficient for addressing mental health needs. Several of the studies reviewed here highlight how paraprofessionals and lay facilitators may be successfully mobilized to deliver mental health and psychosocial interventions.29,50–53,58,59,63 Additional research to examine how families and communities can be trained to address the mental health consequences of war would be useful for extending the continuum of care beyond clinical or school settings to ensure more community-based resources. More research is also needed to assess how locally developed models of healing and spiritual guidance may provide a natural base for building robust, culturally resonant, locally delivered interventions.70

Differential Effects of Interventions Are Under-studied

A number of studies in our review have demonstrated stronger intervention effects in girls than in boys.14,49,131 Few studies to date, however, are of sufficient power to explain such gender effects. In future research, much more attention is needed to understand these differential effects by gender.

Treatment-intervention research will also benefit from a more detailed (and at the same time, broader) examination of how intervention effects are achieved and maintained—and not simply in terms of the efficacy of specified treatments in reducing a defined range of disorder-specific symptoms over a specified time. The need for this paradigm shift is exemplified by findings from cross-cultural applications of the classroom-based intervention that was associated with varying degrees of efficacy in Burundi, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka.12,56,126 Researchers from the study hypothesized that results reflect the varying degree of contextual stressors facing children and youth; for instance, in Indonesia, the higher rates of cohesiveness within families and communities (increasingly segregated by religion following the conflict) were hypothesized to have positively influenced child outcomes.126 In Burundi and Sri Lanka, children exposed to ongoing challenges related to armed conflict and social disruption (e.g., poverty and violence in the home and neighborhood) did not benefit as strongly from intervention.132 Holistic research to investigate how individual, family, and community strengths work in tandem with interventions to support children has the potential to (1) identify active ingredients, which may help strengthen the size of treatment effects, and (2) provide interventionists with a toolbox of naturally occurring processes that can be flexibly targeted and optimized to address context-specific needs.

Measurement Tools for Cross-cultural Use Are Lacking

In the studies reviewed here, very few used locally validated mental health assessments to perform pre/post-intervention evaluations.49,133 Since symptom expression can vary widely between social and cultural contexts,121,127,134,135 evaluating intervention effects based on culturally insensitive measures may produce inaccurate or meaningless results. Integrated qualitative and quantitative (“mixed-methods”) research on context- or culture-specific mental health problems and resources can contribute to refining the suite of assessment and monitoring tools available for cross-cultural use.121 The use of improved measurement tools with strong psychometric properties and cultural acceptability may help to improve future longitudinal research and also research on maintenance interventions.

Mental Health Systems Strengthening and Sustainability Are Critical

From our review, it is evident that interventions to prevent relapse in children needing mental health services due to war-related exposures are currently limited. Humanitarian organizations supporting psychosocial and mental health programs in conflict- and war-affected countries need to systematically integrate a longer-term perspective into their work. Budgetary support, technical assistance, and incentives from the international community can deliver immediate and emergency psychosocial support and mental health care, but political will is needed to galvanize the actual reforms that would build and strengthen systems at the local level. Overall, a dramatic paradigm shift must occur from the deployment of short-term “Band-Aids” to lasting investments, staffing, and technical support. Concurrently, interdisciplinary strategies should be culled from the health, business, and management sectors to guide future policy analyses and implementation research in global mental health, thereby enabling children, adolescents, and their families to be more effectively targeted.

The evidence base for mental health and psychosocial-support interventions for children and adolescents in areas of armed conflict is increasing, and promising intervention effects have been identified through rigorous research (as detailed in this article). Still, considerable gaps in knowledge remain. Our hope is that the overview provided here can serve as a foundation for motivating a shift in attention and for positioning mental health and psychosocial issues squarely at the heart of global humanitarian and postcon-flict development agendas.

Footnotes

The Inter-agency Standing Committee, http://www.humanitarianinfo.org/IASC/, was established by the United Nations in 1992 as “the primary mechanism for inter-agency coordination of humanitarian assistance,” including between “key UN and non-UN humanitarian partners.”

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Contributor Information

Dr. Theresa S. Betancourt, Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard School of Public Health; François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, Harvard University.

Ms. Sarah E. Meyers-Ohki, François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, Harvard University.

Ms. Alexandra P. Charrow, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Wietse A. Tol, Global Health Initiative, Yale University; Department of Mental Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; HealthNet TPO, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

References

- 1.Shibley HL, Stoddard FJ., Jr . Child and adolescent psychiatry interventions. In: Stoddard FJ Jr, Pandya A, Katz CL, editors. Disaster psychiatry: readiness, evaluation, and treatment. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2011. pp. 287–312. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brymer M, Jacobs A, Layne C, et al. Psychological first aid: field operations guide. National Child Traumatic Stress Network, National Center for PTSD. 2006 https://www.medicalreservecorpsgov/File/Promising_Practices_Toolkit/Guidance_Documents/Emergency_Preparedness_Response/MRC_PFA_04-02-08.pdf.

- 3.Barenbaum J, Ruchkin V, Schwab-Stone M. The psychological aspects of children exposed to war: practice and policy initiatives. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:41–62. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attanayake V, McKay R, Joffres M, Singh S, Burkle F, Mills E. Prevalence of mental disorders among children exposed to war: a systematic review of 7,920 children. Med Confl Surviv. 2009;25:19. doi: 10.1080/13623690802568913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inter-agency Standing Committee. IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. Geneva: IASC; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations Children's Fund. The state of the world's children: adolescence, an age of opportunity. New York: UNICEF; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw JA, Espinel Z, Shultz JM. Care of children exposed to the traumatic effects of disaster. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoddard FJ, Saxe G. Ten-year research review of physical injuries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1128–45. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Betancourt TS, Khan KT. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20:317–28. doi: 10.1080/09540260802090363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tol WA, Jordans MJ, Kohrt BA, Betancourt TS, Komproe IH. Promoting mental health and psychosocial wellbeing in children affected by political violence: current evidence for an ecological resilience approach. In: Fernando C, Ferrari M, editors. The handbook on resilience in children of war. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tol WA, Jordans MJ, Komproe IH, De Jong JT. Interventions for children affected by war: synthesis of cluster randomized trials in four countries. Paper presented to International Congress for Transcultural Psychiatry; Florence, Italy. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tol WA, Jordans MJ, Reis C, De Jong JT. Ecological resilience: working with child-related psychosocial resources in war-affected communities. In: Brom D, Pat-Horenczyk R, Ford J, editors. Treating traumatized children: risk, resilience, and recovery. New York: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tol WA, Komproe IH, Susanty D, Jordans MJ, Macy RD, De Jong JT. School-based mental health intervention for children affected by political violence in indonesia. JAMA. 2008;300:8. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panter-Brick C, Eggerman M, Mojadidi A, McDade TW. Social stressors, mental health, and physiological stress in an urban elite of young Afghans in Kabul. Am J Hum Biol. 2008;20:627–41. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betancourt TS, Brennan RT, Rubin-Smith J, Fitzmaurice GM, Gilman SE. Sierra Leone's former child soldiers: a longitudinal study of risk, protective factors, and mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:606–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis BH, Fogler J, Hansen S, Forbes P, Navalta CP, Saxe G. Trauma systems therapy: 15-month outcomes and the importance of effecting environmental change. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4:624–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity: protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masten AS. Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56:227–38. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betancourt TS, Williams T. Building an evidence base on mental health interventions for children affected by armed conflict. Intervention (Amstelveen) 2008;6:39–56. doi: 10.1097/WTF.0b013e3282f761ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bracken PJ, Giller JE, Summerfield D. Psychological responses to war and atrocity: the limitations of current concepts. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:1073–82. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00181-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Summerfield D. A critique of seven assumptions behind psychological trauma programmes in war-affected areas. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1449–62. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00450-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wessells M. Trauma, culture, and community: getting beyond dichotomies. London: Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Jong JT. Public mental health, traumatic stress and human rights violations in low-income countries: a culturally appropriate model in times of conflict, disaster and peace. In: de Jong JT, editor. Trauma, war, and violence: public mental health in socio-cultural context. New York: Plenum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ, editors. Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington DC: National Academy; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]