Abstract

Objective

To estimate the risk of stillbirth among pregnancies complicated by a major isolated congenital anomaly detected by antenatal ultrasound, and the influence of incidental growth restriction.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study of all consecutive singleton pregnancies undergoing routine anatomic survey between 1990 and 2009 was performed. Stillbirth rates among fetuses with an ultrasound-detected isolated major congenital anomaly were compared to fetuses without major anomalies. Stillbirth rates were calculated per 1,000 ongoing pregnancies. Exclusion criteria included delivery prior to 24 weeks of gestation, multiple fetal anomalies, minor anomalies and chromosomal abnormalities. Analyses were stratified by gestational age at delivery (prior to 32 weeks vs. 32 weeks of gestation or after) and birth weight less than the 10th percentile. We adjusted for confounders using logistic regression.

Results

Among 65,308 singleton pregnancies delivered at 24 weeks of gestation or after, 873 pregnancies with an isolated major congenital anomaly (1.3%) were identified. The overall stillbirth rate among fetuses with a major anomaly was 55/1,000 compared to 4/1,000 in nonanomalous fetuses (aOR 15.17, 95% CI 11.03–20.86). Stillbirth risk in anomalous fetuses was similar prior to 32 weeks of gestation (26/1,000) and 32 weeks of gestation or after (31/1,000). Among growth-restricted fetuses, the stillbirth rate increased among anomalous (127/1,000) and nonanomalous fetuses (18/1,000), and congenital anomalies remained associated with higher rates of stillbirth (aOR 8.20, 95% CI 5.27–12.74).

Conclusion

The stillbirth rate is increased in anomalous fetuses regardless of incidental growth restriction. These risks can assist practitioners designing care plans for anomalous fetuses who have elevated and competing risks of stillbirth and neonatal death.

Introduction

In the evaluation that ensues after a stillbirth, congenital anomalies are one of the most commonly identifiable causes (1). However, with the routine use of ultrasound, the diagnosis of a major anomaly often precedes the loss (2, 3). There is minimal data with which to counsel patients regarding the ongoing rate of stillbirth among anomalous fetuses after ultrasound diagnosis, especially if the anomaly is isolated and not associated with a genetic syndrome.

Unlike other risk factors for stillbirth (4–6), guidelines for the antenatal management of pregnancies complicated by isolated fetal anomalies are limited. In addition to the risk of stillbirth, fetuses with congenital anomalies are at risk for growth restriction (7–9), and frequently pregnancy management is based on this subsequent diagnosis rather than the anomaly itself. While fetal growth restriction is a known independent risk factor for stillbirth (10, 11), the interaction between growth restriction and fetal anomalies and its impact on stillbirth is largely undefined.

In this study, we sought to estimate the risk of stillbirth in fetuses with isolated congenital anomalies diagnosed during routine prenatal ultrasound evaluation and examine the influence of the incidental finding of growth restriction on the stillbirth risk using a large ultrasound database at a single institution.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of all consecutive singleton pregnancies presenting for routine anatomic ultrasound examination at Washington University between 1990 and 2009. The study was conducted using an institutional perinatal database that includes ultrasonographic findings, as well as demographic information, maternal medical history, pregnancy, and neonatal outcomes (12). Approval for the study was granted by the Washington University School of Medicine human studies review board.

Pregnancies complicated by an isolated major fetal anomaly diagnosed prenatally were compared to pregnancies in which a major fetal anomaly was absent. Major congenital anomalies were defined as structural abnormalities likely to result in significant functional impairment or need for medical or surgical intervention. Decisions regarding which anomalies were considered “major” were guided by criteria utilized in the European Surveillance of Congenital Anomalies (EUROCAT) network (13).Anomalies included in the study were classified by the organ system affected and are listed in Box 1. Pregnancies were excluded if the fetus had more than one major anomaly or a chromosomal abnormality. Absence of other structural abnormalities was based on prenatal ultrasound findings only, while chromosomal abnormalities may have been diagnosed by either prenatal or postnatal genetic testing. Additionally, pregnancies complicated by minor anomalies, which included any structural abnormality not listed in Table 1, were excluded. Examples of minor anomalies that were excluded include minor markers for aneuploidy, polydactyly, and mild pyelectasis. Pregnancies resulting in delivery prior to 24 weeks of gestation were also not included in this analysis, because documentation regarding elective termination of pregnancy was not well captured within the database and local regulations do not permit elective termination after this gestational age.

Box 1. Major Structural Anomalies Included in the Study by Organ System.

Cardiac (n=119)

Coarctation of the aorta

Tetralogy of Fallot

Transposition of the great vessels

Truncus arteriosus

Double outlet/double inlet ventricle

Hypoplastic left/right heart

Tricuspid atresia

Pulmonary atresia

Aortic stenosis

Ebstein anomaly

Thoracic/respiratory (n=63)

Congenital pulmonary adenomatoid malformation

Pulmonary sequestration

Neurologic (n=153)

Caudal regression

Dandy-Walker malformation

Encephalocele

Holoprosencephaly

Hydranencephaly

Hydrocephalus

Iniencephaly

Meningocele

Ventriculomegaly

Gastrointestinal (n=140)

Anorectal atresia/ imperforate anus

Duodenal atresia

Esophageal atresia

Gastroschisis

Omphalocele

Large bowel obstruction

Small bowel obstruction

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

Genitourinary (n=301)

Absent bladder

Bladder outlet obstruction/ urethral atresia or stenosis

Cloacal persistence/cloacal or bladder extrophy

Hydroureter

Hydronephrosis

Renal dysplasia

Renal hypoplasia

Posterior urethral valves

Renal duplication

Musculoskeletal (n=97)

Clubfoot

Limb reduction

Sirenomelia

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Pregnancies Complicated by a Fetus With an Isolated Major Structural Anomaly Compared to a Pregnancies Without Major Fetal Anomalies

| Isolated Major Anomaly Present (n=873) |

Major Anomaly Absent (n=64,165) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age | |||

| AMA (>34 yrs) | 177 (20.3) | 18,516 (28.9) | <0.01 |

| Race | |||

| Black | 176 (20.2) | 14,732 (22.9) | <0.01 |

| White | 598 (68.5) | 39,305 (61.3) | |

| Other | 99 (11.3) | 10,128 (15.8) | |

| Nulliparous | 369 (42.3) | 24,742 (38.6) | 0.03 |

| BMI | |||

| BMI ≥30 | 142 (16.3) | 12,695 (19.8) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | |||

| Pregestational DM | 24 (2.7) | 1189 (1.9) | 0.05 |

| Gestational DMa | 25 (2.9) | 3250 (5.2) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | |||

| Chronic hypertension | 12 (1.4) | 1558 (2.4) | 0.04 |

| Preeclampsia or gestationalb hypertension | 67 (7.9) | 5085 (8.1) | 0.77 |

| Amniocentesis performed during the pregnancy | 192 (22.0) | 7311 (11.4) | <0.01 |

| Median gestational age at delivery in weeks (IQR) | 38.1 (36.1–39.3) | 39.1 (38.1–40.0) | <0.01 |

| Median birthweight in grams (IQR) | 2931 (2260–3433) | 3348 (2951–3689) | <0.01 |

| Birthweight <10%ile | 213 (24.4) | 7376 (11.5) | <0.01 |

| History of prior stillbirth | 14 (1.6) | 1454 (2.3) | 0.19 |

IQR, interquartile range

Denominators for anomalies group (n=852) and non-anomolous group (n=62,449) due to missing data

Denominators for anomalies group (n=852) and nonanomolous group (n=62,446) due to missing data.

Characteristics of pregnancies complicated by a major congenital anomaly and non-anomalous pregnancies were compared. Data including maternal medical and obstetric history, age, parity, race, and body mass index (kg/m2) were recorded at the time of routine anatomic ultrasound and stored in the perinatal database. Pregnancy outcome data included in the database such as gestational age at delivery, infant birthweight, and diagnosis of complications such as gestational diabetes or preeclampsia were collected by a dedicated pregnancy outcome coordinator in an on-going manner after delivery from the medical record for women delivering within our hospital system or with use of a questionnaire administered to women who delivered elsewhere. If the questionnaire was not returned, the patient or referring provider was contacted by telephone. Pregnancies were considered complicated by growth restriction if the birthweight was less than the 10th percentile using the Alexander chart (14). Statistical comparisons were performed using the Chi-square test for categorical variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare gestational age at delivery and birthweight since these continuous variables were not normally distributed.

The stillbirth rate per 1,000 ongoing pregnancies beyond 23 6/7 weeks of gestation was calculated for pregnancies complicated by isolated major congenital anomaly and those pregnancies without major anomalies. To compare the stillbirth rates in anomalous and non-anomalous pregnancies, we calculated the relative risk of stillbirth with the 95% confidence interval. To determine whether stillbirths occurred early or late in gestation, we performed a stratified analysis based on gestational age at delivery prior to 32 weeks and 32 weeks or after. Stillbirth rates were calculated per ongoing pregnancies, thus the denominator in the prior to 32 weeks stillbirth analysis included all women in the study, while the denominator in the 32 weeks or after strata only included women who were still pregnant at 32 0/7 weeks of gestation. The effect of incidental growth restriction was also investigated using stratified analysis. Multivariable logistic regression was used to adjust for relevant confounders. All characteristics associated with isolated major congenital anomaly in univariable analysis were included in the initial model. A backward, stepwise approach using the likelihood ratio test to assess the effect of the removal of covariates was used to create the final model which included black race, maternal obesity (body mass index >30 kg/m2), and pregestational diabetes. Additionally, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding universally lethal anomalies including anencephaly or acrania and bilateral renal agenesis. We then calculated the rate of stillbirth per 1,000 ongoing pregnancies in each of the six organ system categories and compared these rates to the stillbirth rate in the non-anomalous control group by calculating relative risks and 95% confidence intervals. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 10.0 (special edition, Stata-Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

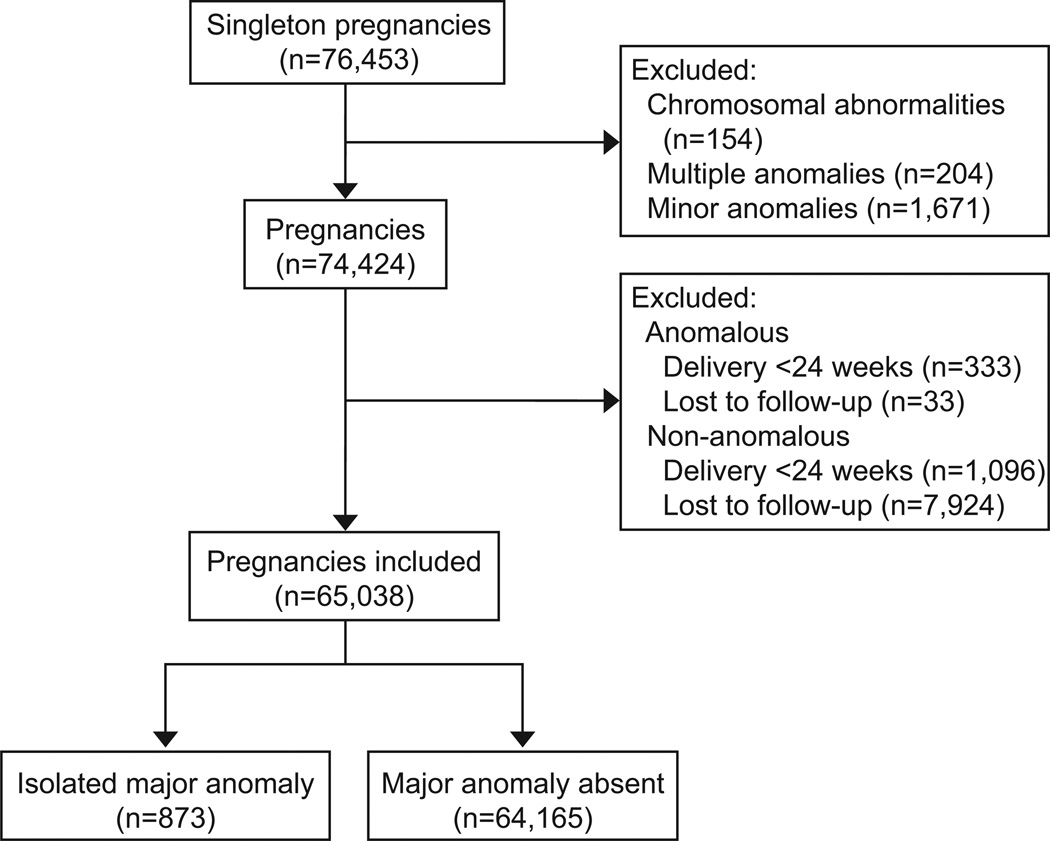

Within the perinatal ultrasound database, 76,453 singleton pregnancies were identified. After excluding pregnancies complicated by chromosomal abnormalities, minor anomalies, or multiple major anomalies in the same fetus, 74,424 pregnancies remained. Delivery prior to 24 weeks of gestation occurred in 1,429 pregnancies (1.9%), of which 333 were among pregnancies complicated by an isolated major congenital anomaly and 1,096 were in nonanomalous pregnancies. In addition, 7,957 pregnancies were lost to follow-up (10.7%); 33 pregnancies were in the anomalous group and 7,924 in the nonanomalous group. The final cohort included 65,308 pregnancies which was comprised of 873 pregnancies with an isolated major congenital anomaly (1.3%) and 64,165 non-anomalous pregnancies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram

Pregnancies complicated by an isolated major congenital anomaly were more likely to occur in women who were white, nulliparous, and advanced maternal age. Maternal obesity, gestational diabetes, and chronic hypertension were more common in non-anomalous pregnancies. Median gestational age at delivery was earlier in pregnancies with an isolated anomaly. Overall median birthweight was lower in pregnancies with an isolated congenital anomaly; additionally 24.4% of anomalous fetuses were also growth restricted at birth, while only 11.5% of non-anomalous pregnancies were complicated by growth restriction (Table 1). The proportion of isolated congenital anomalies detected by ultrasound was similar from 1990–1999 and 2000–2009 (1.29% vs. 1.39%, p=0.27).

Fetuses with an isolated congenital anomaly had a 15-fold increased risk of stillbirth after adjusting for maternal obesity, pregestational diabetes, and black race. The stillbirth rate was highest (127/1000 pregnancies) among pregnancies complicated by both a congenital anomaly and growth restriction. However, because of the relatively high rate of stillbirth in non-anomalous growth restricted pregnancies (18/1000 pregnancies), the risk of stillbirth associated with a major congenital anomaly in growth restricted pregnancies (aOR 8.20, 95% CI 5.27–12.74) is lower than risk associated with a major congenital anomaly in non-growth restricted pregnancies (aOR 15.01, 95% CI 9.34–24.12). Among pregnancies complicated by an isolated anomaly, growth restriction was associated with a greater risk of stillbirth (aOR 4.88, 95% CI 2.65–8.98). In pregnancies complicated by isolated major congenital anomaly as well as incidental growth restriction, the stillbirth rate was higher at ≥32 weeks of gestation than prior to 32 weeks of gestation. Conversely, a higher rate of stillbirth was found prior to 32 weeks’ rather than ≥32 weeks of gestation in anomalous pregnancies that were not growth restricted (Table 2).

Table 2.

Stillbirth Rate Among Fetuses With Isolated Major Structural Anomalies Compared to Fetuses Without Major Structural Anomalies

| Isolated Major Anomaly Present (n=873) |

Major Anomaly Absent (n=64,165) |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

aOR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of stillbirths/ number of pregnancies |

Stillbirth rate/1000 ongoing pregnancies (95% CI) |

Number of stillbirths/ number of pregnancies |

Stillbirth rate/1000 ongoing pregnancies (95% CI) |

|||

| All* | 48/873 | 55 (41–72) | 254/64,165 | 4 (3–4) | 13.89 (10.28–18.77) | 15.17 (11.03–20.86) |

| Stillbirth rate at <32 weeks* | 23/873 | 26 (17–39) | 116/64,165 | 2 (1–2) | 14.57 (9.36–22.68) | 15.78 (10.01–24.89) |

| Stillbirth rate at ≥32 weeks* | 25/795 | 31 (20–46) | 138/63,054 | 2 (1–2) | 14.37 (9.44–21.87) | 15.06 (9.76–23.25) |

| Birthweight <10%ile^ | 27/213 | 127 (85–179) | 133/7,376 | 18 (15–21) | 7.03 (4.76–10.39) | 8.20 (5.27–12.74) |

| Stillbirth rate at <32 weeks^ | 9/213 | 41 (20–79) | 70/7,376 | 9 (7–12) | 4.45 (2.25–8.79) | 4.79 (2.35–9.75) |

| Stillbirth rate at ≥32 weeks^ | 18/191 | 94 (57–145) | 63/7,150 | 9 (7–11) | 10.70 (6.46–17.70) | 12.01 (6.96–20.76) |

| Birthweight >10%ile† | 21/660 | 32 (20–48) | 121/56,789 | 2 (2–3) | 14.93 (9.46–23.58) | 15.01 (9.34–24.12) |

| Stillbirth rate at <32 weeks± | 14/660 | 21 (12–35) | 46/56,789 | 1 (0.6–1) | 26.19 (14.47–47.40) | 27.70 (15.12–50.72) |

| Stillbirth rate at ≥32 weeks± | 7/604 | 12 (5–24) | 75/55,904 | 1 (1–2) | 8.64 (4.00–18.67) | 8.92 (4.09–19.44) |

Adjusted for black race, obesity, and pregestational diabetes

Adjusted for obesity

Adjusted for black race and pregestational diabetes

Adjusted for black race

Twenty-eight pregnancies were complicated by an anomaly considered always lethal, including anencephaly, acrania, and bilateral renal agenesis. A sensitivity analysis excluding these anomalies from the isolated major congenital anomaly group did not significantly affect the results of the primary analysis. Isolated major anomaly remained significantly associated with an increased risk of stillbirth compared to non-anomalous pregnancies (47/1000 pregnancies (n=40) vs. 4/1000 pregnancies (n=254), aOR 12.95, 95% CI 9.18–18.23). The stillbirth rate was also higher in pregnancies complicated an isolated congenital anomaly compared to non-anomalous pregnancies whether the pregnancy was also complicated by growth restriction (111/1000 (n=21) versus 18/1000 (n=133) pregnancies; aOR 7.17, 95 % CI 4.40–11.70) or not (29/1000 (n=19) versus 2/1000 (n=121) pregnancies; aOR 14.49, 95% CI 8.87–23.70). Furthermore, in anomalous pregnancies, growth restriction was associated with an increased risk of stillbirth (111/1000 (n=21) versus 29/1000 (n=19) pregnancies; aOR 4.42; 95% CI 2.29–8.52).

Pregnancies complicated by isolated major congenital anomalies in each of the organ system categories considered were at an increased risk of stillbirth relative to non-anomalous pregnancies. The highest stillbirth rate was found among fetuses with congenital heart disease (143/1000 pregnancies) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Stillbirth Rate Among Fetuses With Isolated Major Structural Anomalies Compared to Fetuses Without Major Structural Anomaliesby Organ System

| Major Anomaly Absent (n=64,165) |

Major Anomaly Present | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cardiac (n=119) |

Thoracic (n=63) |

Neurologic (n=153) |

GI (n=140) |

Urinary (n=301) |

MS (n=97) |

||

| Stillbirth rate (95% CI) | 4 (3–4) | 143 (85–219) | 32 (4–110) | 92 (51–149) | 36 (12–81) | 20 (7–43) | 41 (11–102) |

| RR (95% CI) | ref | 36.09 (22.85–56.99) | 8.02 (2.04–31.54) | 23.12 (13.82–38.65) | 9.02 (3.78–21.52) | 5.04 (2.26–11.22) | 10.42 (3.96–27.41) |

GI= gastrointestinal; MS= musculoskeletal

Stillbirth rate per 1000 ongoing pregnancies

Discussion

We found that pregnancies complicated by isolated major congenital anomalies are associated with a 15-fold increased risk of stillbirth. Overall, 1 in every 18 pregnancies complicated by an isolated major anomaly will result in fetal death. Incidental growth restriction was associated with an even higher rate of stillbirth; occurring in approximately 1 in every 8 pregnancies complicated by growth restriction and isolated congenital anomaly.

The results of this study can be used to counsel patients regarding the increased risk of stillbirth associated with isolated major congenital anomalies and develop antepartum management plans. While growth restriction is a known risk factor for stillbirth (10, 11), our data confirms that stillbirth rates are highest in fetuses that are both anomalous and growth-restricted. Further, rates of stillbirth in nongrowth-restricted anomalous fetuses were higher than the stillbirth rate among nonanomalous, growth-restricted pregnancies. Increased fetal surveillance is often instituted for pregnancies complicated by a wide variety of conditions that are associated with increased stillbirth risk (4). However, fetal anomaly, with perhaps the exception of gastroschisis (15), is not considered an indication for testing unless the fetus is also growth restricted. This management strategy may be misguided given the high risk of stillbirth in anomalous fetuses independent of growth restriction. Nevertheless, initiating antenatal surveillance in pregnancies complicated by an isolated fetal anomaly is a complex decision as the competing risk of neonatal demise increases with decreasing gestational age, particularly in anomalous fetuses (16–19). For specific anomalies, there may be a gestational age at which the risk of stillbirth exceeds the postnatal mortality risk and thus the initiation of antenatal surveillance with its incumbent false positive rate (20) warrants consideration. Unfortunately, we did not collect specific data about fetal surveillance in this study, thus further research is needed to better define the time point in gestation when the stillbirth rate approximates the neonatal death rate for individual anomalies.

Our finding that there is an association between fetal abnormality and stillbirth is consistent with prior studies (1, 13, 21, 22). However our study design allowed us to explore the relationship from a different perspective, with the goal of obtaining information with which to counsel women and families who have received the diagnosis of an isolated major fetal anomaly at the time of routine anatomic ultrasound and who elect to continue the pregnancy and reach a gestational age at which most non-anomalous fetuses are considered viable. Most other studies that have examined the association between stillbirth and fetal anomalies have done so from the perspective of evaluating causes of stillbirth (1, 21, 22), which does not provide data regarding the ongoing risk of stillbirth in an anomalous fetus. The EUROCAT study, a large international registry in Europe that has been in existence for over 30 years, has provided much of the available information regarding risks associated with fetal anomalies (23). However, multiple data sources are used for case ascertainment, which include registries of infants that are diagnosed postnatally up to age one year of life. The stillbirth risk calculated using data that includes postnatal diagnosis would be expected to be lower than the stillbirth risk associated with fetal anomalies that are detected by ultrasound prenatally. While ultrasound detects between 40–64% of fetal structural abnormalities (2, 3, 24), those that are detected by ultrasound are more likely to be severe (3) and thus may be associated with a higher risk of intrauterine death.

Most other studies evaluating the association between stillbirth and anomalies have included fetuses with multiple anomalies (13). It is difficult to attribute the risk of stillbirth associated with a single structural abnormality if fetuses with multiple anomalies are included. Additionally, it is more likely that a fetus with multiple anomalies has a genetic syndrome, which itself might be associated with increased mortality (25, 26). Our utilization of only prenatal ultrasound findings to define the absence of other structural malformations but both prenatal and postnatal genetic testing to exclude pregnancies complicated by chromosomal abnormalities may seem incongruent. However, this reflects the stillbirth risk utilizing prenatally available information. While ultrasound may not detect all structural abnormalities, prenatal genetic testing is available and offered to all women. Ultimately data from our study could be used to counsel women about risk of stillbirth if the fetus does not have a chromosomal abnormality and only has a single anomaly detected by ultrasound; albeit there may be additional ultrasound findings not detectable prenatally.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists defines stillbirth as fetal death at 20 weeks or greater or a fetal weight ≥350 grams if the gestational age is unknown (4). We chose to exclude women who delivered prior to 24 weeks of gestation based on local regulations regarding termination of pregnancy. We acknowledge that there is a selection bias introduced by this approach because we surmise that pregnancies that are terminated are more likely to have had a more severe congenital anomaly. Our approach, however, would likely bias the results towards the null as the more severe congenital anomalies may be associated with higher stillbirth risk.

Overall, both isolated congenital anomaly and stillbirth are rare events. The large size of our single center ultrasound database gave us the ability to perform this analysis. However, there was less precision of the risk estimates in some of the subgroup analyses due to the small numbers. The ultrasound and patient follow-up information in the database is more detailed than is typically recorded in larger national and international registries (27). A limitation of this is that data collected at a single referral center could decrease the generalizability of our findings. And while there was follow-up available on 89.6% of women who underwent ultrasound evaluation at our center, some pregnancies were excluded because of incomplete data. Further investigation found that these women were more likely to be younger in age, African American race, obese, and multiparous compared to women included in the study. It is unclear how the exclusion of these pregnancies would have impacted our results. Additionally, chromosomal analysis was only performed in 73.9% of cases of isolated anomalies, thus some cases of genetically abnormal fetuses could have been misclassified.

The study was conducted over an almost 20 year time period. Changes in ultrasound detection rates over this time period were likely minimal as a similar proportion of all pregnancies were found to be complicated by an isolated congenital anomaly. However, the availability and efficacy of postnatal care of fetuses with congenital anomalies over this time period may have impacted our results. Some may argue that defining growth restriction using birth weight is another limitation as obstetric management is based on prenatal diagnosis of growth restriction. However, ultrasound assessment of fetal weight is largely inaccurate (28), thus the use of birth weight provides a more direct approach to examining the true relationship between growth restriction and stillbirth. Furthermore, our finding that the stillbirth risk is high in pregnancies complicated by an isolated congenital anomaly regardless of incidental growth restriction in anomalous fetuses means that reliance on prenatal assessment of fetal growth to guide management is unnecessary.

In summary, we found that pregnancies complicated by an isolated congenital fetal anomaly are at high risk of stillbirth regardless of the incidental diagnosis of growth restriction. Our data could be used to help obstetric care providers counsel patients receiving an antenatal diagnosis of an isolated anomaly. While antenatal surveillance is frequently initiated in pregnancies at high risk for stillbirth, practitioners caring for these patients should weigh the competing risks of postnatal mortality with antenatal death. Critical evaluation of these competing risks, specific to individual anomalies, should be the focus of future studies.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Frey is supported by a training grant from the NICHD T32 grant (5 T32 HD055172-05) and this publication was supported by the Washington University CTSA grant (UL1 TR000448).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented as a poster at the 33rd Annual Meeting of the Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine, February 15, 2013, San Francisco, California.

References

- 1.Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network. Causes of death among stillbirths. JAMA. 2011;306(22):2459–2468. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romosan G, Henriksson E, Rylander A, Valentin L. Diagnostic performance of routine ultrasound screening for fetal abnormalities in an unselected Swedish population in 2000–2005. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34(5):526–533. doi: 10.1002/uog.6446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grandjean H, Larroque D, Levi S. The performance of routine ultrasonographic screening of pregnancies in the Eurofetus Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(2):446–454. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70577-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 102: management of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(3):748–761. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819e9ee2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ACOG Practice bulletin no. 134: fetal growth restriction. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):1122–1133. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000429658.85846.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 37, August 2002. Thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(2):387–396. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallenstein MB, Harper LM, Odibo AO, Roehl KA, Longman RE, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Fetal congenital heart disease and intrauterine growth restriction: a retrospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(6):662–665. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.597900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raynor BD, Richards D. Growth retardation in fetuses with gastroschisis. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16(1):13–16. doi: 10.7863/jum.1997.16.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoury MJ, Erickson JD, Cordero JF, McCarthy BJ. Congenital malformations and intrauterine growth retardation: a population study. Pediatrics. 1988;82(1):83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardosi J, Madurasinghe V, Williams M, Malik A, Francis A. Maternal and fetal risk factors for stillbirth: population based study. BMJ. 2013;346:f108. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, Froen JF, Smith GC, Gibbons K, Coory M, Gordon A, Ellwood D, McIntyre HD, Fretts R, Ezzati M. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1331–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goetzinger KR, Cahill AG, Macones GA, Odibo AO. Echogenic bowel on second-trimester ultrasonography: evaluating the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(6):1341–1348. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821aa739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolk H, Loane M, Garne E. The prevalence of congenital anomalies in Europe. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;686:349–364. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9485-8_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(2):163–168. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00386-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brantberg A, Blaas HG, Salvesen KA, Haugen SE, Eik-Nes SH. Surveillance and outcome of fetuses with gastroschisis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23(1):4–13. doi: 10.1002/uog.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costello JM, Polito A, Brown DW, McElrath TF, Graham DA, Thiagarajan RR, Bacha EA, Allan CK, Cohen JN, Laussen PC. Birth before 39 weeks' gestation is associated with worse outcomes in neonates with heart disease. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):277–284. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cnota JF, Gupta R, Michelfelder EC, Ittenbach RF. Congenital heart disease infant death rates decrease as gestational age advances from 34 to 40 weeks. J Pediatr. 2011;159(5):761–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colvin J, Bower C, Dickinson JE, Sokol J. Outcomes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a population-based study in Western Australia. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):e356–e363. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porter A, Benson CB, Hawley P, Wilkins-Haug L. Outcome of fetuses with a prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of isolated omphalocele. Prenat Diagn. 2009;29(7):668–673. doi: 10.1002/pd.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evertson LR, Gauthier RJ, Schifrin BS, Paul RH. Antepartum fetal heart rate testing. I. Evolution of the nonstress test. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;133(1):29–33. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90406-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Getahun D, Ananth CV, Kinzler WL. Risk factors for antepartum and intrapartum stillbirth: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Facchinetti F, Alberico S, Benedetto C, Cetin I, Cozzolino S, Di Renzo GC, Del Giovane C, Ferrari F, Mecacci F, Menato G, Tranquilli AL, Baronciani D. A multicenter, case-control study on risk factors for antepartum stillbirth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(3):407–410. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.496880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyd PA, Haeusler M, Barisic I, Loane M, Garne E, Dolk H. Paper 1: The EUROCAT network--organization and processes. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91(Suppl 1):S2–S15. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levi S. Ultrasound in prenatal diagnosis: polemics around routine ultrasound screening for second trimester fetal malformations. Prenat Diagn. 2002;22(4):285–295. doi: 10.1002/pd.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wapner RJ. Genetics of stillbirth. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(3):628–634. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181ee2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Korteweg FJ, Bouman K, Erwich JJ, Timmer A, Veeger NJ, Ravise JM, Nijman TH, Holm JP. Cytogenetic analysis after evaluation of 750 fetal deaths: proposal for diagnostic workup. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):865–874. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816a4ee3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Odibo AO, Francis A, Cahill AG, Macones GA, Crane JP, Gardosi J. Association between pregnancy complications and small-for-gestational-age birth weight defined by customized fetal growth standard versus a population-based standard. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(3):411–417. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.506566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudley NJ. A systematic review of the ultrasound estimation of fetal weight. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25(1):80–89. doi: 10.1002/uog.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]