Short abstract

Subject to a compressive membrane stress, an elastic film bonded on a substrate can become unstable, forming wrinkles, creases or delaminated buckles. Further increasing the compressive stress can induce advanced modes of instabilities including period-doubles, folds, localized ridges, delamination, and coexistent instabilities. While various instabilities in film-substrate systems under compression have been analyzed separately, a systematic and quantitative understanding of these instabilities is still elusive. Here we present a joint experimental and theoretical study to systematically explore the instabilities in elastic film-substrate systems under uniaxial compression. We use the Maxwell stability criterion to analyze the occurrence and evolution of instabilities analogous to phase transitions in thermodynamic systems. We show that the moduli of the film and the substrate, the film-substrate adhesion strength, the film thickness, and the prestretch in the substrate determine various modes of instabilities. Defects in the film-substrate system can facilitate it to overcome energy barriers during occurrence and evolution of instabilities. We provide a set of phase diagrams to predict both initial and advanced modes of instabilities in compressed film-substrate systems. The phase diagrams can be used to guide the design of film-substrate systems to achieve desired modes of instabilities.

1. Introduction

Thin films bonded on thick substrates appear in diverse biological and engineering systems, with examples ranging from skins on animals and fruits to coatings on various engineering objects. Compressive membrane stresses can be frequently induced in films bonded on substrates due to various reasons, such as growth and swelling of the films [1–7], thermal expansion mismatch between the films and the substrates [8–12], ion irradiation treatment [13,14], electric fields applied on the films [15–17], relaxation of prestretches in the substrates [18–23], and mechanical compression on the substrates [24–27]. As the compressive stresses in the films reach critical values, the homogeneous deformation of the film-substrate systems becomes unstable, switching into states of inhomogeneous deformation with nonflat configurations of the films.

In recent decades, extensive experimental and theoretical studies have reported various modes of instabilities in film-substrate systems, including wrinkling, creasing, delaminated buckling, period-doubling, localized ridges, folds, and hierarchical wrinkling and crumpling [14,24,26,28–33]. The coexistence and co-evolution of wrinkling and delaminated buckling have also been observed and analyzed [10,34,35]. Despite the extensive works and substantial results in this field, a systematic and quantitative understanding of various modes of instabilities in film-substrate systems is still elusive. Previous experiments usually use specific materials (e.g., metals on polymers) to construct the film-substrate systems, which restrict systematic variation of the film and substrate's mechanical properties to achieve various modes of instabilities. Similarly, previous theoretical studies rarely analyze various modes of instabilities together in systematic approaches. However, a general and quantitative understanding of various instabilities in film-substrate systems is of fundamental importance to the physics and mechanics of solids. In addition, such a systematic understanding will rationally guide the applications of instabilities in various modern technologies, such as flexible electronics [36,37] and biomedical devices [5,38]. Recently, Cao and Hutchinson theoretically analyzed wrinkling, creasing, period-doubling, folding, and localized ridges together, without considering delaminated buckling or coexistent instabilities [29].

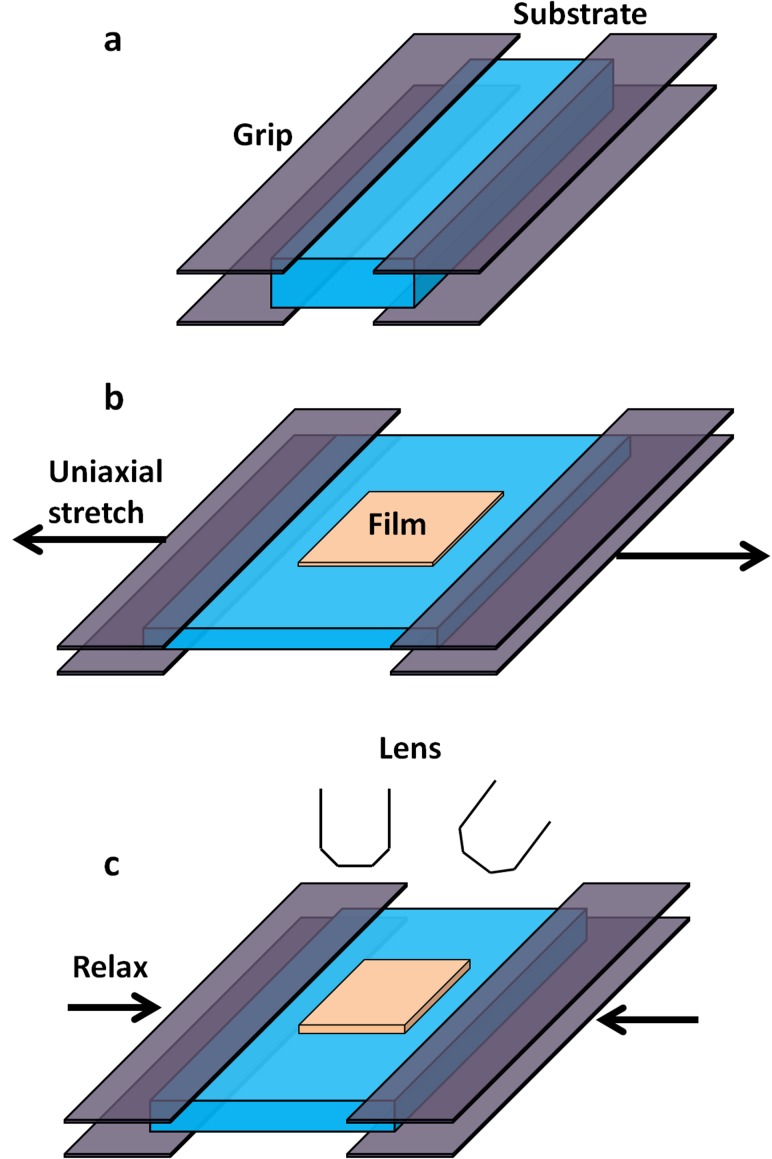

In the current paper, we present a combined experimental and theoretical study on multiple modes of instabilities in elastic film-substrate systems under uniaxial compression. In the experiment, we use polymers to construct the film and the substrate, and systematically vary moduli of the polymers, adhesion strength between film and substrate, film thickness, and prestretch in the substrate (Fig. 1). Consequently, our experiment demonstrates a systematic set of instabilities: (i) If the film is well-bonded on the substrate and much more rigid than the substrate, the system first gives the wrinkling instability. (ii) If the film is well-bonded on the substrate but has a lower or slightly higher modulus than the substrate, the creasing instability can first set in. (iii) If the bonding between the film and substrate is relatively weak, the film tends to delaminate from the substrate, giving the delaminated buckling instability. (iv) Further compressing the film-substrate system can induce advanced modes of instabilities including period-doubles, localized ridges, folds, delamination, and coexistence of instabilities.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the experimental procedure to observe various modes of instabilities in film-substrate systems under uniaxial compression

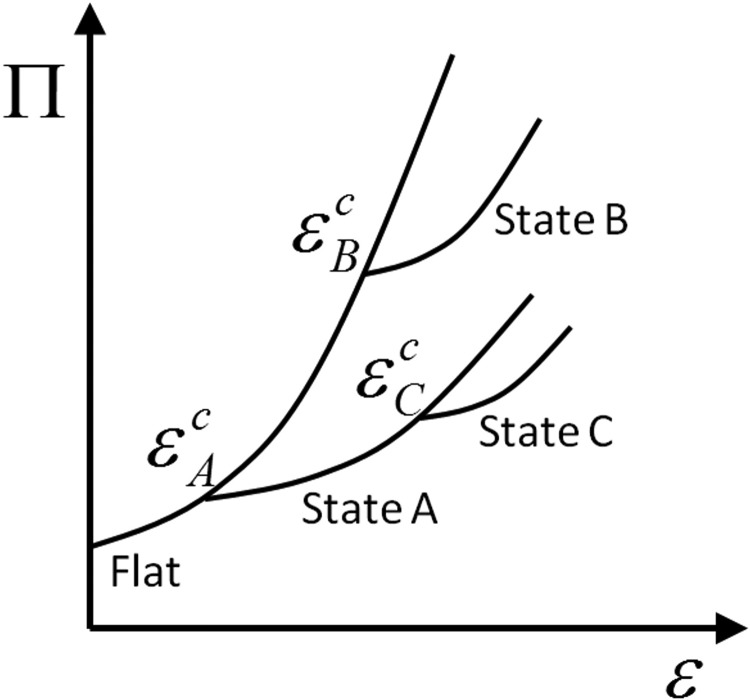

To systematically and quantitatively account for various modes of instabilities, we regard the elastic film and substrate as a thermodynamic system and calculate the potential energies of various configurations of the system observed in the experiments. The potential energies will evolve with the applied compressive strain (Fig. 2). We then adopt the Maxwell stability criterion [39–42], and regard the configuration with the global minimum of potential energy as the current state of the system under an applied compressive strain. The Maxwell stability criterion is commonly used for analyzing phase transitions in thermodynamic systems, where underlying fluctuations are assumed to be able to shake the systems out of local potential-energy minima to seek a global minimum. The same principle has also been used to analyze instabilities and co-existence of states in structures and materials [39,43–47]. In order for thermodynamic systems to switch between different states, energy barriers sometimes need to be overcome.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of the evolution of a film-substrate system's potential energy with the applied compressive strain and the transition of states

A combination of our experiment and theory shows that the moduli of the film and the substrate, the film-substrate adhesion strength, the film thickness, and the prestretch in the substrate determine occurrence and evolution of various instabilities. Defects in the film-substrate systems can facilitate them to exceed the energy barriers during state transition. We further provide quantitative phase diagrams to predict both initial and advanced modes of the instabilities.

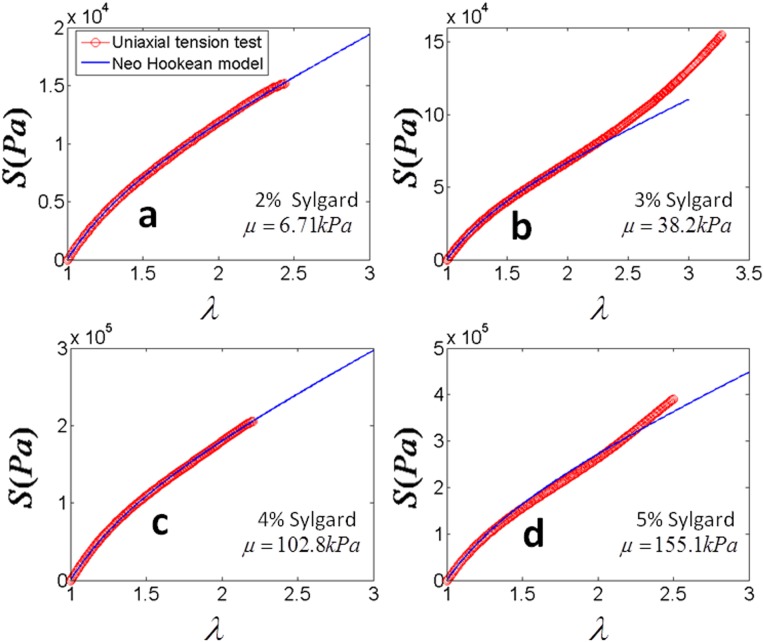

2. Experimental

Two types of silicone elastomers, Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning, USA) and Ecoflex 0010 (Smooth-on, Easton, PA), were used to construct the film and the substrate, respectively. The Sylgard was spin-casted into thin films with thickness ranging from ∼21 to ∼583 μm by varying the spinning speed from 5000 to 100 rpm. The Ecoflex was casted into thick substrates with thickness over 5 mm, so that the substrates are much thicker than the films in the experiments. The shear modulus of Ecoflex was measured to be 10.4 kPa, and the shear modulus of Sylgard was varied from 6.7 to 155 kPa by changing its crosslinker concentration (Fig. 13) [16–19]. The shear moduli of the polymers were measured by fitting stress versus strain data from uniaxial tensile tests to the neo-Hookean law.

As illustrated in Fig. 1(a), the long edges of a rectangular Ecoflex substrate were clamped on two grips of a uniaxial stretcher. The long edges of the substrate were set to be much longer than its short edges, so that the substrate can be uniaxially prestretched to a prescribed ratio, λp. The Sylgard film was then carefully attached on the prestretched substrate by uniformly pressing it on the substrate with two rigid plates (Fig. 1(b)). For relatively thick films, a very thin layer of uncured Ecoflex can also be smeared on the substrate prior to attaching the films. Once cured, the thin Ecoflex layer can enhance the adhesion between film and substrate without affecting instabilities of the system. Thereafter, the prestretched substrate was gradually relaxed with a strain rate around , while the occurrence and evolution of instabilities were observed with two microscope lenses viewing at different angles (Fig. 1(c)). For cases with unprestretched substrates, the film-substrate system was attached to another thick layer of Ecoflex that had been uniaxially prestretched. Relaxation of the prestretched bottom layer induced compression in the film-substrate system.

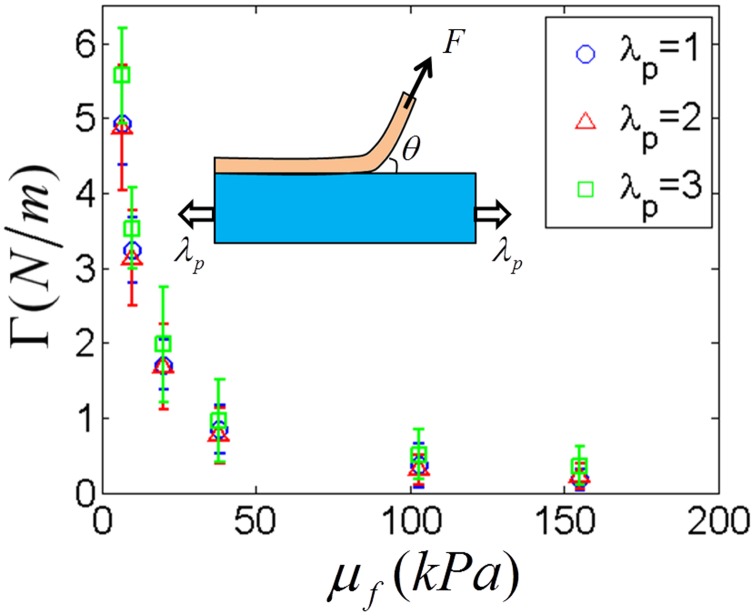

The adhesion energy between the film and the substrate was measured with the peeling test (Fig. 3) [48,49]. A strip of Sylgard film with width b was carefully attached on a prestretched Ecoflex substrate by uniformly pressing it on the substrate with two rigid plates. After 30 min at room temperature, a force F was applied to the Sylgard film to peel off the substrate along the prestretch direction with an angle at a low peeling rate . The adhesion energy was calculated by , where is the strain in the detached section of the Sylgard film [48]. The adhesion energy between Sylgard film and Ecoflex substrate decreases with the increase of film modulus, but only slightly varies with the prestretch in the substrate. In practical experiments, the adhesion strength between the film and the substrate can be controlled by varying moduli of the film and substrate (e.g., Fig. 3) or by applying adhesives between them.

Fig. 3.

The adhesion energy between Sylgard films and prestretched Ecoflex substrates

3. Potential Energy and Maxwell Stability Criterion

Both the film and the substrate are taken to be incompressible neo-Hookean materials with shear moduli, and , respectively. The neo-Hookean law applies to the Ecoflex substrate under uniaxial stretch up to 2.5 [15,50], and also applies to Sylgard films under uniaxial stretch up to 2.2 (Fig. 13 in the Appendix). At undeformed states, the film has a length L and thickness , and the substrate has a length and thickness , where (Fig. 4(a)). The substrate is prestretched uniaxially by a stretch of along the length direction, and then bonded to the film. We take the prestretched-bonded state (Fig. 4(b)) to be the reference state of the system. Thereafter, a uniaxial compressive strain is applied to the film-substrate system, which reduces the length of system by , so that the applied compressive strain is (Fig. 4(c)). Throughout the whole process, the width of the film and the substrate is maintained to be unit to give plane-strain deformation. Therefore, the potential energy of the film-substrate system at the current state can be expressed as

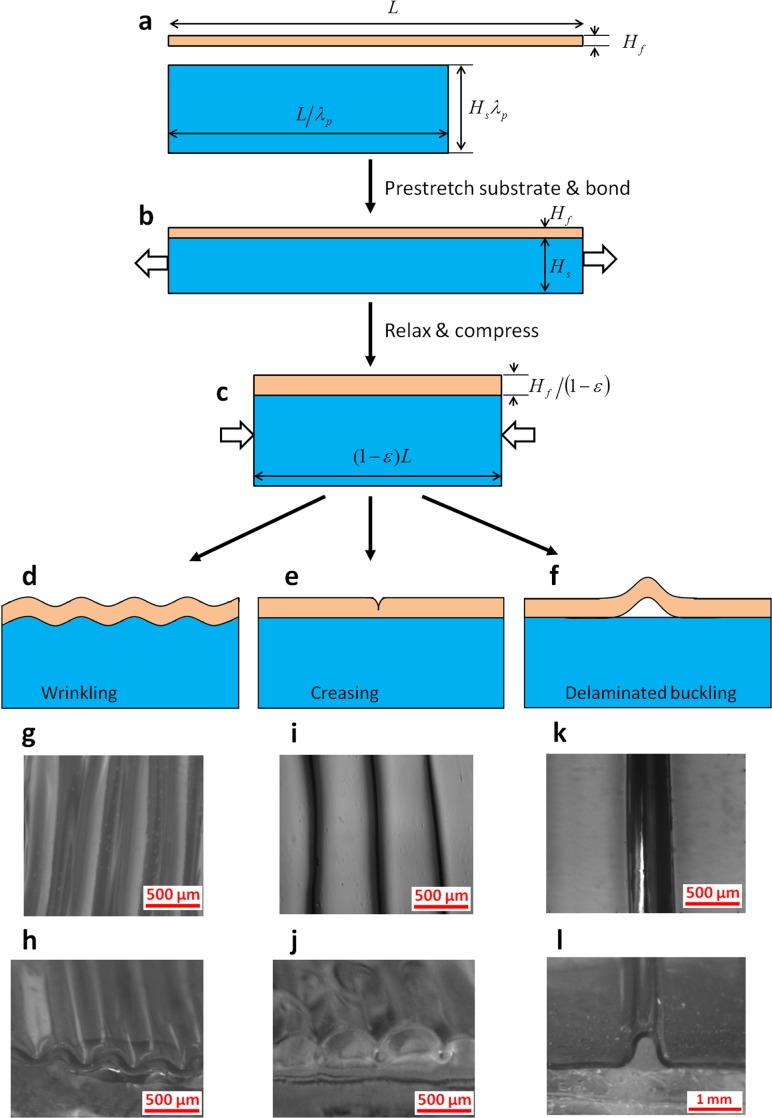

Fig. 4.

Schematic illustration of a film-substrate system under plane-strain deformation (a-c), and the three initial modes of instabilities (d-f). Optical microscopic images of the wrinkling (g, top view; h, side view), creasing (i, top view; j, side view), and delaminated buckling (k, top view; l, side view) instabilities.

| (1) |

where and are the elastic energies of the film and the substrate, respectively, the film-substrate adhesion energy per unit area at the reference state, and is the length of the current delaminated region at the reference state. Since our experiments are carried out in air, the surface energies of the polymers have been neglected due to their small values and negligible effect in the current system [19].

We denote the potential energy of the system at an initial equilibrium state as (e.g., the homogenous state). As the applied compressive strain reaches a critical value , the system transits into a new state, i, with potential energy . Both and can be calculated with Eq. (1) numerically or analytically, and the potential energy difference is

| (2) |

According to the Maxwell stability criterion, transition between the two states requires (i) represents a global minimum of potential energy of the system at , (ii) the new state, i, satisfies equilibrium conditions, (iii) , and (iv) , where is an infinitesimal increment of the applied strain.

Depending on the prestretch in the substrate, a film-substrate system's potential energy may decrease or increase with the applied compressive strain. Without loss of generality, Fig. 2 schematically illustrates the evolution of a film-substrate system's potential energy with applied strain and the transition of states. When the applied strain is relatively low, the flat state of the film-substrate system gives the global minimum of potential energy. As the applied strain reaches a critical value , the potential energy of a new state A becomes equal to that of the flat state, and the system transits into state A. We define the new states switched from the flat state as the initial modes of instabilities. It is noted that, at a higher applied strain , the potential energies of state B and the flat state are also equal to each other. However, since the potential energy of the flat state is no longer a global minimum at , the system will have transited into state A before is reached.

After the system transits into state A, the applied compressive strain can be further increased (Fig. 2). As the applied strain reaches another critical value , the potential energy of a new state C becomes equal to that of state A, so that the system transits into state C. We define the new states switched from a nonflat state as the advanced modes of instabilities. During the transition of states, the system sometimes needs to exceed certain energy barriers, which will also be discussed in the following sections.

4. Initial Modes of Instabilities

Our experiments have shown that the homogeneous deformation of flat film-substrate systems can transit into at least three initial modes of instabilities: wrinkling, creasing, and delaminated buckling (Fig. 4). The potential energy of the film-substrate system at the flat state is

| (3) |

The potential energy of the flat state will be compared to those of various initial modes of instabilities (Fig. 4) to determine the occurrence of these instabilities. Considering Eqs. (1) and (3) and , we can express the critical strains for various modes of instabilities by dimensional arguments as

| (4) |

Based on the Maxwell stability criterion, the critical strains for various modes of instabilities can be calculated together with other characters of the instabilities, such as wavelengths of wrinkles and delaminated lengths of buckles.

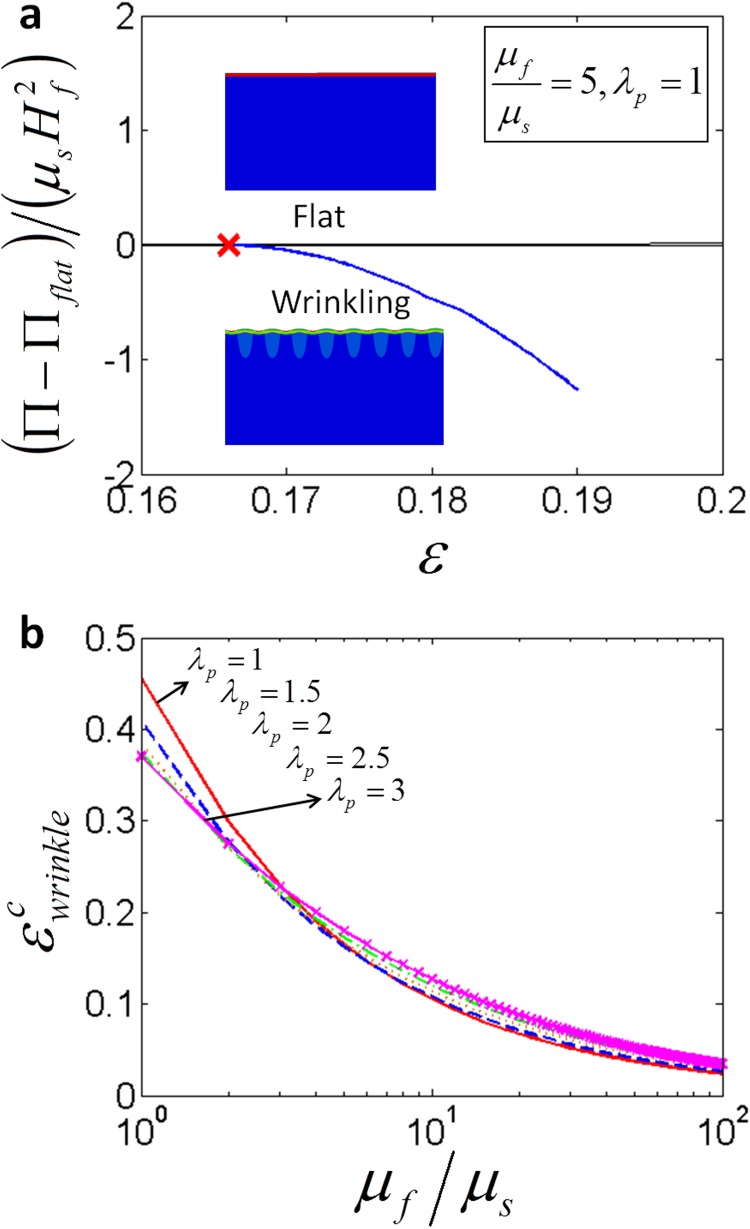

Wrinkling.

Following Cao and Hutchinson [29], we perform linear stability analysis on a film-substrate system with a prestretched substrate to calculate the critical strain for wrinkling, . The linear stability analysis guarantees that the wrinkled state satisfies equilibrium condition. Since the amplitude of wrinkles is infinitesimal at , the potential energies of flat and wrinkled states are the same during state transition, i.e., . This is validated by the finite element calculation as shown in Fig. 14(a) in the Appendix. The theoretical predictions of [29] for various values of and are plotted in Fig. 14(b) in the Appendix. It can be seen that is a monotonic decreasing function of . The maximum value of is around 0.465 for and , consistent with Biot's [51] and recently Cao and Hutchinson's [29] analyses. In addition, for large values of moduli ratio (e.g., ), the critical strain can be approximated as [29,52]

| (5) |

where accounts for the effect of the uniaxial prestretch in the substrate.

The above analysis for wrinkling instability, however, does not guarantee that the flat state has a global minimum of potential energy at . Since the system may have transited into other modes of instabilities before is reached, we need to compare with the critical strains of other initial modes of instabilities (Fig. 2).

Creasing.

While the creasing instability occurs at localized locations on the surface of the film, the strain around the crease is nevertheless finite [53–55]. Therefore, the linear stability analysis which assumes small deformation is not adequate to analyze the critical strain for creasing instability. By using finite element method, Hong et al. [55] and Wong et al. [56] predeformed a crease of size a on the surface of the film by applying a perpendicular line force F. At the initiation of the crease, , and thus the homogeneous deformation of the substrate is not perturbed. At a critical strain , both potential energy difference and F reach zero, indicating the creased state has the same potential energy as the flat state and the creased state satisfies the equilibrium condition. In addition, since the crease size a can be set to be infinitesimal in the above analysis, there is no energy barrier for the transition between flat and creased states, given that the surface energy of the film is negligible. In cases where the surface energy of the film is significant, the system needs to overcome an energy barrier for crease initiation [19,57]. As a result, the critical strain for creasing instability may be sensitive to imperfections on the surface of the film due to surface-energy effect of the film [19,57].

Delaminated Buckling.

The transition from flat to delaminated buckled states reduces the film-substrate system's elastic energy, but increases its adhesion energy. The potential energy difference between the delaminated buckled and flat states can be expressed as

| (6) |

where is the elastic energy difference between the delaminated buckled and flat states, and D is the length of the delaminated region at the reference state. According to the Maxwell stability criterion, the transition between flat and delaminated buckled states requires

| (7) |

| (8) |

Solving Eqs. (7) and (8) give the critical strain and the corresponding delaminated length . As illustrated in Fig. 5(a), we construct a finite-element model to calculate the elastic energy of the delaminated buckled state under various compressive strain and delaminated length D. The length of the film-substrate system L is set to be much larger than D. Due to symmetry, only a half of the system needs to be calculated (Fig. 5(a)). A small force perturbation is introduced at the topmost node of the buckling region to trigger the buckling without affecting the potential energy of the system [18,34]. It is noticed that the finite-element model sometimes can give other instabilities under certain applied strain, which indicates delaminated buckling is not the current mode of instability. In order to calculate the potential energies of delaminated buckled states under various applied strains, we deliberately suppress other modes of instabilities in the model. However, if the deliberate suppression is required for any critical strain , our theory predicts that other modes of instabilities will occur before delaminated buckling.

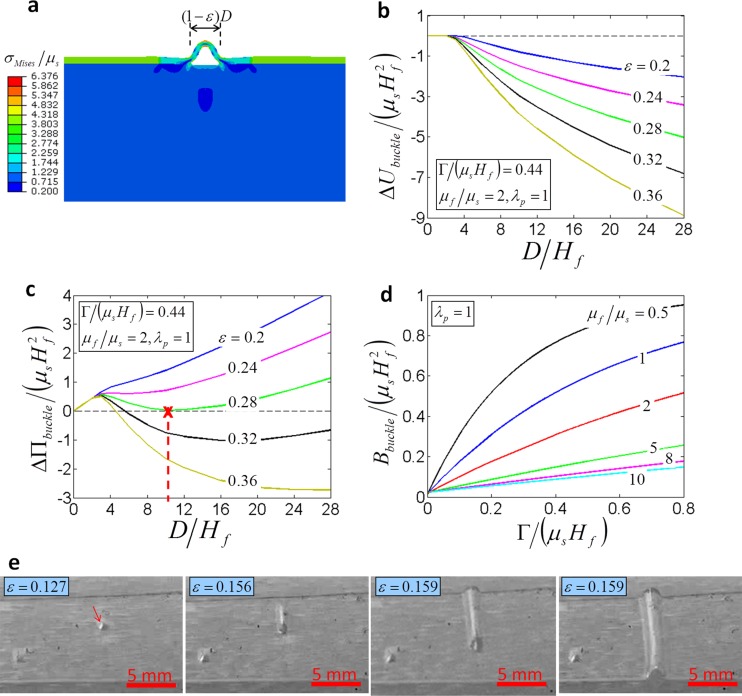

Fig. 5.

A finite-element model for calculating the elastic energy of a film-substrate system at the delaminated buckled state (a). The calculated elastic (b) and potential (c) energy difference between the delaminated buckled and flat states as functions of the applied compressive strain and delaminated length. The calculated energy barrier for the transition from flat to delaminated buckled states (d). Optical microscopic images of the initiation and propagation of a delaminated buckle in a film-substrate system under compression (e). The delaminated buckle initiates at defects on the film-substrate interface as indicated by an arrow.

From Fig. 5(b), it can be seen that is zero at relatively low values of , where the film delaminates but cannot buckle out [58,59]. At relatively large values of , the delaminated film buckles out, significantly reducing the system's elastic energy. In Fig. 5(c), we plot as functions of for various values of the applied compressive strain. For instance, when , , and , Eqs. (7) and (8) are satisfied at with corresponding .

As shown in Fig. 5(c), the film-substrate system indeed needs to overcome an energy barrier for the transition from flat to delaminated buckled states. The energy barrier has been calculated for various values of and (Fig. 5(d)). It can be seen that the energy barriers are mostly lower than . As shown in Fig. 5(e), defects on the film-substrate interface (e.g., air bubble and initial delamination) can greatly facilitate the system to overcome the energy barriers. Once a delaminated-buckled region is initiated, it will propagate throughout the sample with a constant delaminated length . The transition is analogous to the coexistence of states in structures and materials [39,43,44,47].

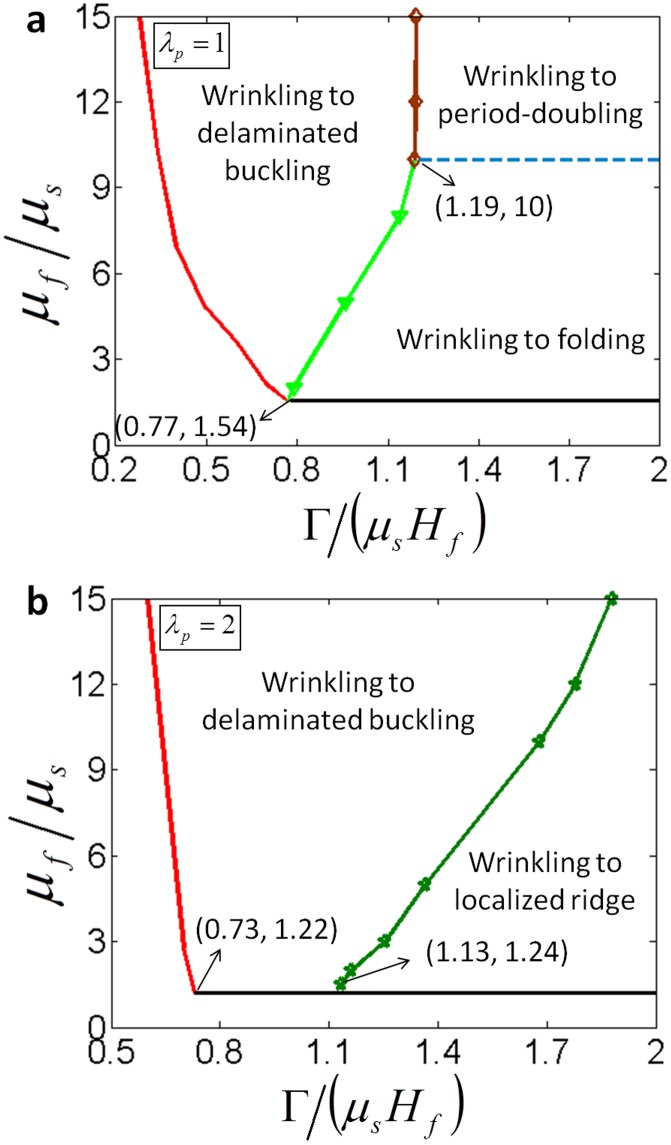

Phase Diagram of Initial Modes of Instabilities.

The flat state of the film-substrate system can bifurcate into a mode of wrinkling, creasing or delaminated buckling instability, depending on which mode has the lowest critical strain (Fig. 2). Based on above analyses, we construct a phase diagram for the initial modes of instabilities using , , and as variables that characterize the film-substrate system.

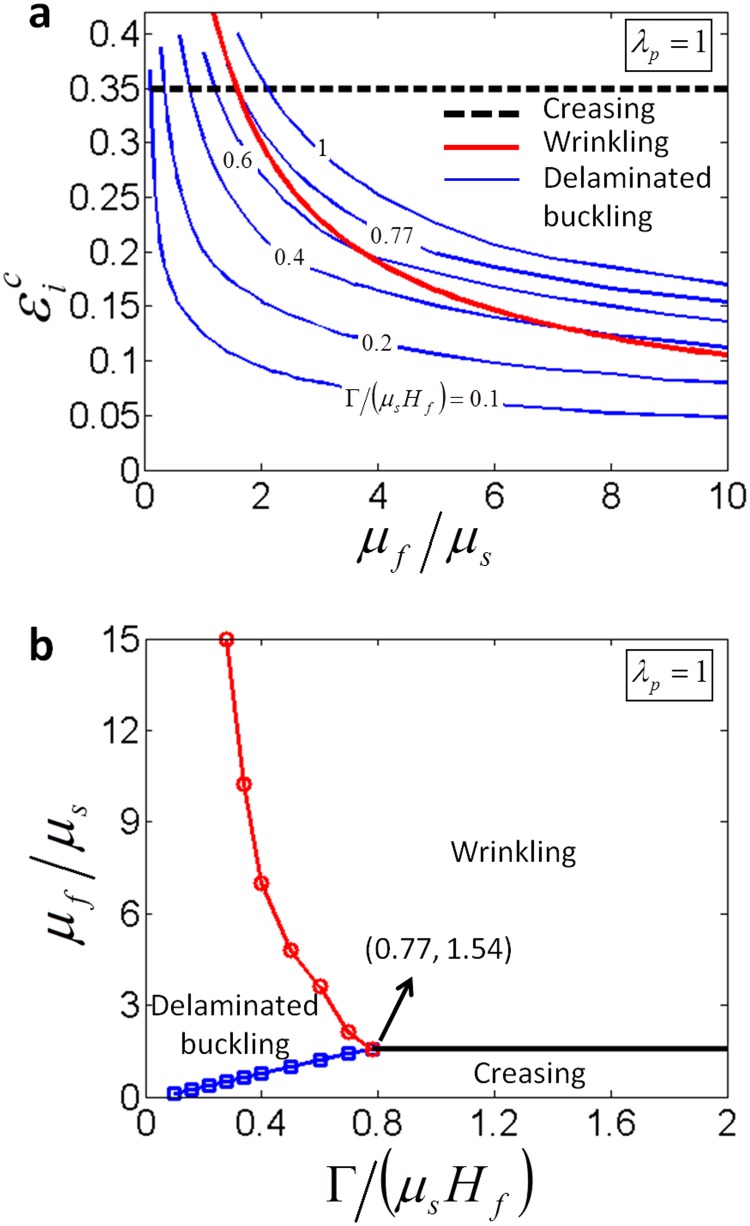

In Fig. 6(a), we plot the calculated critical strains of various initial modes of instabilities in film-substrate systems with . It can be seen that both and are decreasing functions of , but is a constant, 0.35. Furthermore, for the same value of , the function increases with . The intersections of curves in Fig. 6(a) provide the phase boundaries for the initial modes of instabilities in film-substrate systems with . From the phase diagram (Fig. 6(b)), it is obvious that relatively high values of and give wrinkling, high but low induces creasing, and low leads to delaminated buckling. This trend is consistent with our experimental observations (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the triple-point for the three modes of initial instabilities lies at and .

Fig. 6.

The calculated critical strains (a) and phase diagram (b) of the initial modes of instabilities in film-substrate systems with

In Figs. 7(a) and 7(b), we further plot the calculated phase diagrams for initial modes of instabilities in film-substrate systems with and 3, respectively. It can be seen that the prestretch in the substrate does not change the qualitative structure of the phase diagram, but varies the values of phase boundaries. For example, the critical value of that separates wrinkling and creasing instabilities reduces from 1.54 for to 1.22 for and 1.14 for . In addition, we have performed a systematic set of experiments on film-substrate systems with , by varying the film thickness, the modulus ratio of film and substrate, and the adhesion energy. From Fig. 7(a), it can be seen that the experimental results are mostly consistent with the prediction of the phase diagram. It is also noted that the phase diagram tends to underestimate the critical between wrinkling and creasing instabilities, possibly due to defects on the film surface or thickness effect of the substrate in the experiment, which may give the creasing instability at higher values of than the theoretical prediction.

Fig. 7.

The calculated phase diagrams of the initial modes of instabilities in film-substrate systems with (a) and (b), respectively. Comparison of the experimentally observed instabilities and the calculated phase diagram of instabilities in a film-substrate system with is plotted in (a).

5. Advanced Modes of Instabilities

After the flat state of the film-substrate system switches into an initial mode of instability, the applied compressive strain can be further increased. As the strain reaches another critical value, an advanced mode of instability sets in. By dimensional arguments, the advanced modes of instabilities are also determined by nondimensional parameters , , and . In the current study, we will focus on advanced modes of instabilities switched from the initial mode of wrinkling instability. We will briefly summarize the period-doubling, folding, and localized-ridge instabilities theoretically analyzed by Cao and Hutchinson [29]. Thereafter, we will discuss the transition from wrinkling to delamination and the phase diagrams for advanced modes of instabilities.

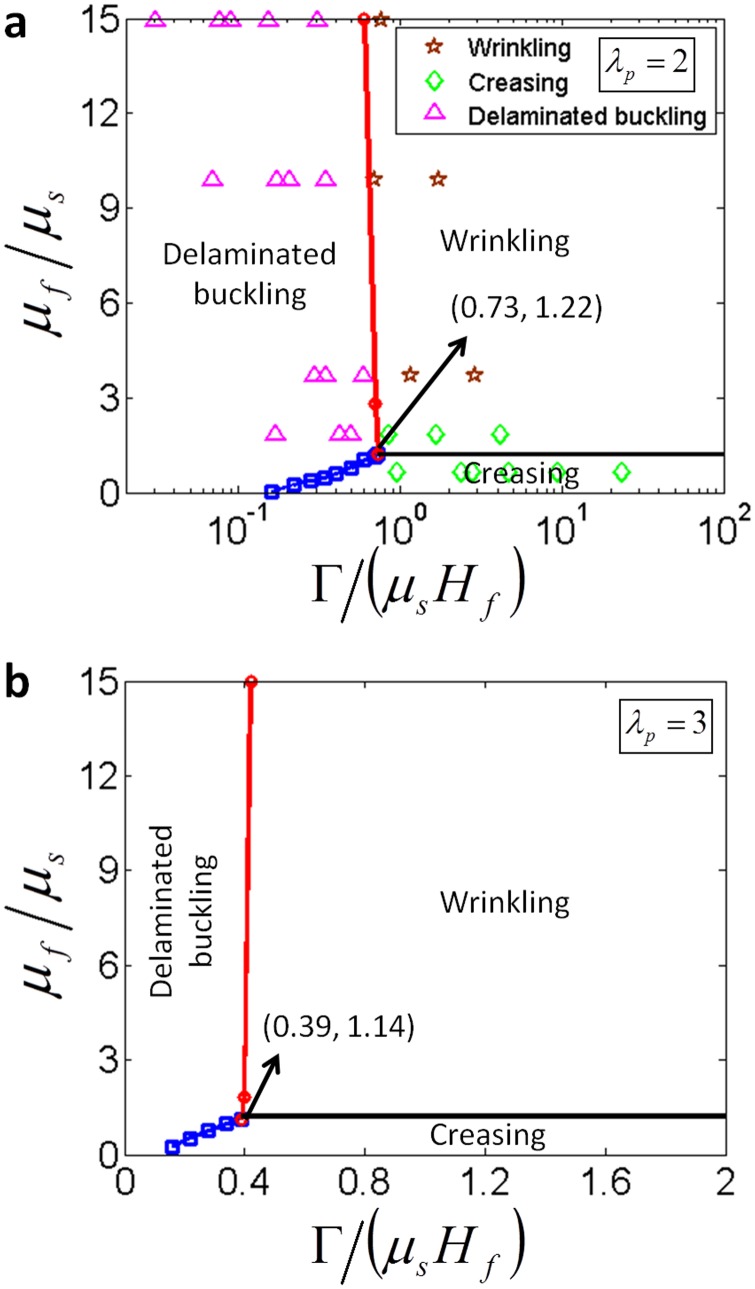

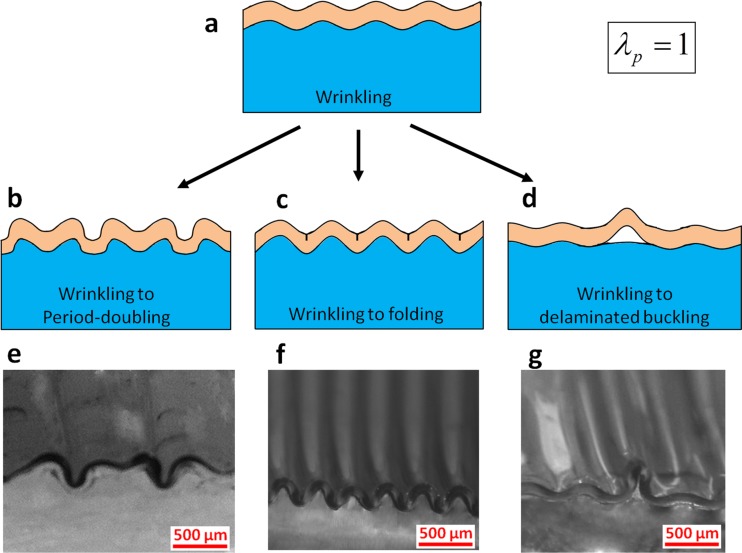

Wrinkling to Period-Doubling.

A flat film-substrate system with and appropriate values of and can develop wrinkles at . If the values of and are relatively large, as the applied compressive strain increases to another critical value , the sinusoidal wrinkles can transit into an advanced mode of instability, the so-called the period-doubling instability, as show in Figs. 8(b) and 8(e) [26,28,29,60]. The period double bifurcates from wrinkles by varying the height of adjacent valleys, leading to a wavelength twice of the corresponding wrinkles. Cao and Hutchinson [29] have carried out finite-element simulation for the period-doubling instability in film-substrate systems, and found it requires for film-substrate systems with to transit from wrinkling to period-doubling instability.

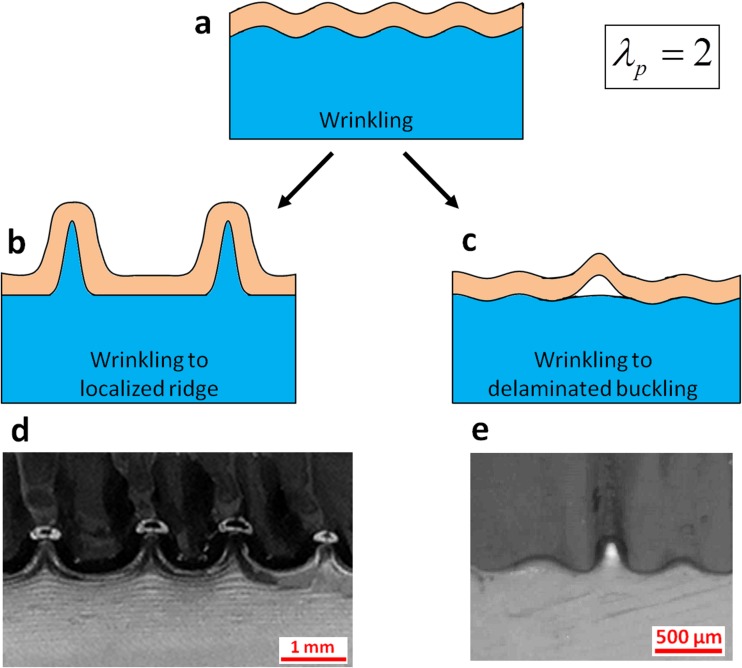

Fig. 8.

Schematic illustration of advanced modes of instabilities transited from the wrinkling instability in a film-substrate system with (a-d). Optical microscopic images of the double-doubling (e), folding (f), and delaminated buckling (g) instabilities in film-substrate systems with .

Wrinkling to Folding.

If and is relatively high, the wrinkled film-substrate system with can develop folds at some valleys of the wrinkles, when the applied compressive strain reaches a critical value . Thereafter, the folds quickly initiate creases in the film under a slight increment of compression (Figs. 8(c) and 8(f)), giving coexistence of wrinkling and creasing. Similar transition has been numerically simulated by Kang and Huang [61] and Wu et al. [62] in swelling of bilayer hydrogels with different properties. Following Cao and Hutchinson [29], we calculate the critical strain using finite-element models with imperfections on the surface of the films.

Wrinkling to the Localized Ridge.

If the value of is relatively high and the prestretch in the substrate is also high (e.g., ), the wrinkled film-substrate system will transit into another advanced mode of instability, so-called localized ridges, at a critical strain as illustrated in Fig. 9(b) [29,31,35]. Compared to the sinusoidal shape of wrinkles, the ridge is relatively narrow at its upper part and relatively wide at its bottom part (Fig. 9(b)). The formation of the localized ridge is due to high anisotropy of the effective substrate moduli induced by the prestretch, and it reduces the amplitude of wrinkles at adjacent regions of the ridge. As the applied compressive strain further increases, more ridges appear in between the initial ones, leading to a pattern of ridges as shown in Fig. 9(d). Following Cao and Hutchinson [29], we calculate the critical strain , using finite-element models with imperfections.

Fig. 9.

Schematic illustration of advanced modes of instabilities transited from the wrinkling instability in a film-substrate system with (a-c). Optical microscopic images of the localized ridge (d) and delaminated buckling instabilities (e) in film-substrate systems with .

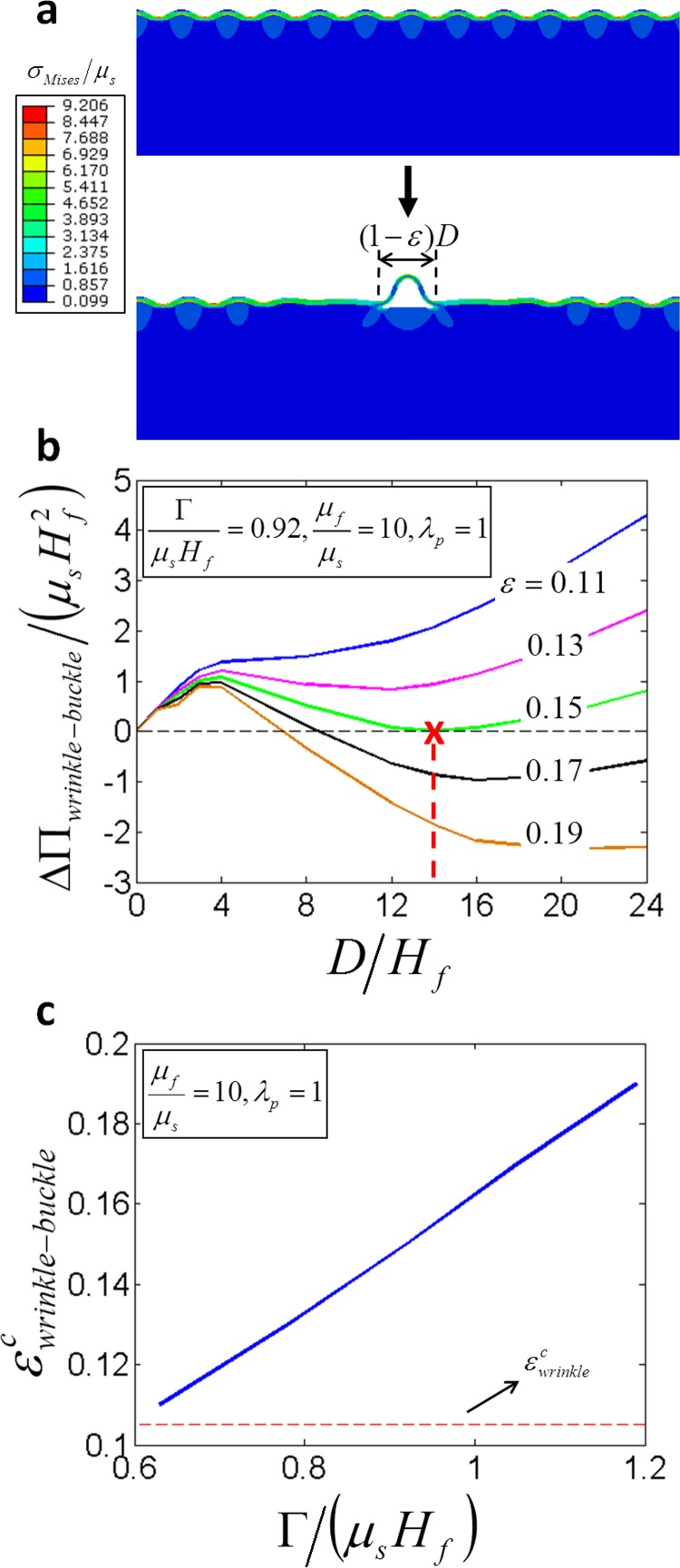

Wrinkling to Delaminated Buckling.

The occurrence of advanced modes of instabilities discussed above requires relatively strong adhesion between films and substrates. On the other hand, if the value of is relatively low, the wrinkled film-substrate system can develop delaminated buckles at a critical strain , leading to the coexistence of wrinkles and delaminated buckles [34,63]. As shown in Figs. 8(d) and 8(g) for and Figs. 9(c) and 9(e) for , the delaminated buckles reduce the amplitude of adjacent wrinkles and therefore reduce the elastic energy of the film-substrate system.

Following a similar procedure described in Sec. 4, we calculate the difference between potential energies of the delaminated-buckled state and the corresponding wrinkled state with finite-element models (Fig. 10). By solving Eqs. (7) and (8), we obtain the critical strain and the corresponding delaminated length (Fig. 10(b)). As expected, the critical strain increases with the normalized adhesion energy (Fig. 10(c)). In addition, an energy barrier also exists for the transition from wrinkling to delaminated buckling instabilities (Fig. 10(b)). The delamination can initiate at defects on the film-substrate interface and propagate throughout the system. The normal and shear stresses on the interfaces at wrinkled state can also facilitate the system to exceed the energy barrier [34,63].

Fig. 10.

A finite-element model for calculating the elastic energy of the delaminated buckled state transited from the wrinkled state (a). The calculated potential energy difference between the delaminated buckled and the corresponding wrinkled states as functions of the applied compressive strain and delaminated length (b). The calculated critical strain for the delaminated buckling instability transited from the wrinkling instability (c). It is higher than the critical strain for wrinkling instability.

In Fig. 11, we further plot the evolution of potential energies of film-substrate systems from wrinkling to various advanced modes of instabilities calculated by finite-element models. It can be seen, at sufficiently low values of , the delaminated buckling can precede other advanced modes of instabilities.

Fig. 11.

The evolution of potential energies of film-substrate systems from wrinkling to various advanced modes of instabilities calculated by finite element models: from wrinkling to delaminated buckling and period-doubling at (a), from wrinkling to delaminated buckling and folding at (b), and from wrinkling to delaminated buckling and localized ridge at (c). At sufficiently low values of , the delaminated buckling can precede other advanced modes of instabilities.

A Phase Diagram of Advanced Modes of Instabilities Transited From Wrinkling.

In Figs. 12(a) and 12(b), we provide two phase diagrams of advanced modes of instabilities switched from the wrinkling instability for and , respectively. For the unprestretched substrate (i.e., ), relatively high values of and transit the wrinkling instability into period-doubling, high but low gives folding, and low leads to delaminated buckling. For highly prestretched substrates (i.e., ), relatively high value of transit wrinkling into localized ridge, and low gives delaminated buckling. While the phase diagrams for other values of prestretches will be explored in future studies, it is expected that Figs. 12(a) and 12(b) are representative for film-substrate systems with unprestretched (or slightly prestretched) and highly prestretched substrates, respectively.

Fig. 12.

The calculated phase diagrams of advanced modes of instabilities transited from the wrinkling instability in film-substrate systems with (a) and (b)

Fig. 13.

The nominal stress versus stretch curve of the Sylgard films used in the current study under uniaxial tension. When the stretch is lower than 2.2, the Sylgard films follow the neo-Hookean law.

Fig. 14.

The evolution of potential energies of film-substrate systems from flat state to wrinkled state calculated by the finite-element model as shown in the inset (a). The critical strain for wrinkling for various modulus ratio and prestretch (b). The calculated critical strain for wrinkling in (a) matches the prediction in (b). In the finite element calculation, the thickness of the substrate and width of the model are much larger than the film thickness. A small force perturbation is applied to the film under compression to trigger the wrinkling.

6. Concluding Remarks

In summary, we present a joint experimental and theoretical study on instabilities of elastic film-substrate systems under uniaxial compression. The experiment demonstrates both initial modes of instabilities including wrinkling, creasing, and delaminated buckling and advanced modes of instabilities including period-doubles, folds, localized ridges, delamination, and coexistence of instabilities. An approach based on the Maxwell stability criterion is developed to predict the occurrence and evolution of various modes of instabilities. We find that the moduli of the film and the substrate , the film-substrate adhesion energy , the film thickness , and the prestretch in the substrate determine various instabilities. In particular, the occurrence of delaminated buckling requires the film-substrate system to overcome an energy barrier, which can be facilitated by defects on film-substrate interface. We provide a set of phase diagrams for both initial and advanced modes of instabilities using , , and as variables that characterize the film-substrate system. The phase diagrams can be used to guide the design of film-substrate systems to achieve desired modes of instabilities.

A number of future research directions to explore instabilities in film-substrate systems become possible. For example, similar phase diagrams can be constructed for advanced modes of instabilities transited from the initial creasing [18,53,64] and delaminated buckling [27,58,59] instabilities, and for more complicated instabilities transited from an advanced mode of instability. Similarly, various instabilities in film-substrate systems under biaxial compression have also been analyzed individually but still require a systematic understanding [6,7,9,11,13,14,30,65–71]. Furthermore, it is expected that the systematic understanding and phase diagrams of instabilities can guide future design of new materials and structures for practical applications [2,5,21,36,38,72].

Acknowledgment

The work was supported by NSF CAREER Award (CMMI-1253495), NSF grants (DMR-1121107, CMMI-1200515), and ONR grant (N000141310828). Q.M.W. acknowledges the support of a fellowship from Duke Center for Bimolecular and Tissue Engineering (Grant No. NIH-2032422).

Appendix

References

- [1]. Jin, L. , Cai, S. , and Suo, Z. , 2011, “Creases in Soft Tissues Generated by Growth,” EPL (Europhys. Lett.), 95(6), p. 64002.10.1209/0295-5075/95/64002 [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Chan, E. P. , Smith, E. J. , Hayward, R. C. , and Crosby, A. J. , 2008, “Surface Wrinkles for Smart Adhesion,” Adv. Mater., 20(4), pp. 711–71610.1002/adma.200701530 [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Guvendiren, M. , Burdick, J. A. , and Yang, S. , 2010, “Solvent Induced Transition From Wrinkles to Creases in Thin Film Gels With Depth-Wise Crosslinking Gradients,” Soft Matter, 6(22), pp. 5795–580110.1039/c0sm00317d [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Tanaka, T. , Sun, S. T. , Hirokawa, Y. , Katayama, S. , Kucera, J. , Hirose, Y. , and Amiya, T. , 1987, “Mechanical Instability of Gels at the Phase Transition,” Nature, 325(6107), pp. 796–79810.1038/325796a0 [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Kim, J. , Yoon, J. , and Hayward, R. C. , 2009, “Dynamic Display of Biomolecular Patterns Through an Elastic Creasing Instability of Stimuli-Responsive Hydrogels,” Nature Mater., 9(2), pp. 159–16410.1038/nmat2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Yin, J. , Cao, Z. , Li, C. , Sheinman, I . , and Chen, X. , 2008, “Stress-Driven Buckling Patterns in Spheroidal Core/Shell Structures,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 105(49), pp. 19132–1913510.1073/pnas.0810443105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Li, B. , Jia, F. , Cao, Y.-P. , Feng, X.-Q. , and Gao, H. , 2011, “Surface Wrinkling Patterns on a Core-Shell Soft Sphere,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 106(23), pp. 234301.10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.234301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Bowden, N. , Brittain, S. , Evans, A. G. , Hutchinson, J. W. , and Whitesides, G. M. , 1998, “Spontaneous Formation of Ordered Structures in Thin Films of Metals Supported on an Elastomeric Polymer,” Nature, 393(6681), pp. 146–14910.1038/30193 [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Chen, X. , and Hutchinson, J. W. , 2004, “Herringbone Buckling Patterns of Compressed Thin Films on Compliant Substrates,” ASME J. Appl. Mech., 71(5), pp. 597–60310.1115/1.1751186 [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Mei, H. , Huang, R. , Chung, J. Y. , Stafford, C. M. , and Yu, H. H. , 2007, “Buckling Modes of Elastic Thin Films on Elastic Substrates,” Appl. Phys. Lett., 90(15), p. 151902.10.1063/1.2720759 [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Cai, S. , Breid, D. , Crosby, A. , Suo, Z. , and Hutchinson, J. , 2011, “Periodic Patterns and Energy States of Buckled Films on Compliant Substrates,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 59(5), pp. 1094–111410.1016/j.jmps.2011.02.001 [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Gioia, G. , and Ortiz, M. , 1997, “Delamination of Compressed Thin Films,” Adv. Appl. Mech., 33, pp. 119–19210.1016/S0065-2156(08)70386-7 [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Moon, M.-W. , Lee, S. H. , Sun, J.-Y. , Oh, K. H. , Vaziri, A. , and Hutchinson, J. W. , 2007, “Wrinkled Hard Skins on Polymers Created by Focused Ion Beam,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 104(4), pp. 1130–113310.1073/pnas.0610654104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Kim, P. , Abkarian, M. , and Stone, H. A. , 2011, “Hierarchical Folding of Elastic Membranes Under Biaxial Compressive Stress,” Nature Mater., 10(12), pp. 952–95710.1038/nmat3144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Wang, Q. , Tahir, M. , Zang, J. , and Zhao, X. , 2012, “Dynamic Electrostatic Lithography: Multiscale On-Demand Patterning on Large-Area Curved Surfaces,” Adv. Mater., 24(15), pp. 1947–195110.1002/adma.201200272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Wang, Q. , Zhang, L. , and Zhao, X. , 2011, “Creasing to Cratering Instability in Polymers Under Ultrahigh Electric Fields,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 106(11), pp. 118301.10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.118301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Wang, Q. , Tahir, M. , Zhang, L. , and Zhao, X. , 2011, “Electro-Creasing Instability in Deformed Polymers: Experiment and Theory,” Soft Matter, 7(14), pp. 6583–658910.1039/c1sm05645j [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Cai, S. , Chen, D. , Suo, Z. , and Hayward, R. C. , 2012, “Creasing Instability of Elastomer Films,” Soft Matter, 8(5), pp. 1301–130410.1039/c2sm06844c [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Chen, D. , Cai, S. , Suo, Z. , and Hayward, R. C. , 2012, “Surface Energy as a Barrier to Creasing of Elastomer Films: An Elastic Analogy to Classical Nucleation,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 109(3), pp. 38001.10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.038001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Khang, D. Y. , Jiang, H. , Huang, Y. , and Rogers, J. A. , 2006, “A Stretchable Form of Single-Crystal Silicon for High-Performance Electronics on Rubber Substrates,” Science, 311(5758), pp. 208–21210.1126/science.1121401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Yang, S. , Khare, K. , and Lin, P. C. , 2010, “Harnessing Surface Wrinkle Patterns in Soft Matter,” Adv. Funct. Mater., 20(16), pp. 2550–256410.1002/adfm.201000034 [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Sun, Y. , Choi, W. M. , Jiang, H. , Huang, Y. Y. , and Rogers, J. A. , 2006, “Controlled Buckling of Semiconductor Nanoribbons for Stretchable Electronics,” Nature Nanotechnol., 1(3), pp. 201–20710.1038/nnano.2006.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Jiang, H. , Khang, D. Y. , Song, J. , Sun, Y. , Huang, Y. , and Rogers, J. A. , 2007, “Finite Deformation Mechanics in Buckled Thin Films on Compliant Supports,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 104(40), pp. 15607–1561210.1073/pnas.0702927104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Efimenko, K. , Rackaitis, M. , Manias, E. , Vaziri, A. , Mahadevan, L. , and Genzer, J. , 2005, “Nested Self-Similar Wrinkling Patterns in Skins,” Nature Mater., 4(4), pp. 293–29710.1038/nmat1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Stafford, C. M. , Harrison, C. , Beers, K. L. , Karim, A. , Amis, E. J. , Vanlandingham, M. R. , Kim, H. C. , Volksen, W. , Miller, R. D. , and Simonyi, E. E. , 2004, “A Buckling-Based Metrology for Measuring the Elastic Moduli of Polymeric Thin Films,” Nature Mater., 3(8), pp. 545–55010.1038/nmat1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Brau, F. , Vandeparre, H. , Sabbah, A. , Poulard, C. , Boudaoud, A. , and Damman, P. , 2010, “Multiple-Length-Scale Elastic Instability Mimics Parametric Resonance of Nonlinear Oscillators,” Nature Phys., 7(1), pp. 56–6010.1038/nphys1806 [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Vella, D. , Bico, J. , Boudaoud, A. , Roman, B. , and Reis, P. M. , 2009, “The Macroscopic Delamination of Thin Films From Elastic Substrates,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 106(27), pp. 10901–1090610.1073/pnas.0902160106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Sun, J. Y. , Xia, S. , Moon, M. W. , Oh, K. H. , and Kim, K. S. , 2012, “Folding Wrinkles of a Thin Stiff Layer on a Soft Substrate,” Proc. R. Soc. A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Science, 468(2140), pp. 932–95310.1098/rspa.2011.0567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Cao, Y. , and Hutchinson, J. W. , 2012, “Wrinkling Phenomena in Neo-Hookean Film/Substrate Bilayers,” ASME J. Appl. Mech., 79(3), pp. 1019.10.1115/1.4005960 [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Zang, J. , Ryu, S. , Pugno, N. , Wang, Q. , Tu, Q. , Buehler, M. J. , and Zhao, X. , 2013, “Multifunctionality and Control of the Crumpling and Unfolding of Large-Area Graphene,” Nature Mater., 12(4), pp. 321–32510.1038/nmat3542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Zang, J. , Zhao, X. , Cao, Y. , and Hutchinson, J. W. , 2012, “Localized Ridge Wrinkling of Stiff Films on Compliant Substrates,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 60(7), pp. 1265–127910.1016/j.jmps.2012.03.009 [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Diab, M. , Zhang, T. , Zhao, R. , Gao, H. , and Kim, K.-S. , 2013, “Ruga Mechanics of Creasing: From Instantaneous to Setback Creases,” Proc. R. Soc. A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Science, 469(2157), p. 20120753.10.1098/rspa.2012.0753 [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Hutchinson, J. W. , 2013, “The Role of Nonlinear Substrate Elasticity in the Wrinkling of Thin Films,” Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 371(1993), p. 20120422.10.1098/rsta.2012.0422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Mei, H. , Landis, C. M. , and Huang, R. , 2011, “Concomitant Wrinkling and Buckle-Delamination of Elastic Thin Films on Compliant Substrates,” Mech. Mater., 43(11), pp. 627–64210.1016/j.mechmat.2011.08.003 [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Ebata, Y. , Croll, A. B. , and Crosby, A. J. , 2012, “Wrinkling and Strain Localizations in Polymer Thin Films,” Soft Matter, 8(35), pp. 9086–909110.1039/c2sm25859e [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Rogers, J. A. , Someya, T. , and Huang, Y. , 2010, “Materials and Mechanics for Stretchable Electronics,” Science, 327(5973), pp. 1603–160710.1126/science.1182383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Jiang, H. , Khang, D. Y. , Fei, H. , Kim, H. , Huang, Y. , Xiao, J. , and Rogers, J. A. , 2008, “Finite Width Effect of Thin-Films Buckling on Compliant Substrate: Experimental and Theoretical Studies,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 56(8), pp. 2585–259810.1016/j.jmps.2008.03.005 [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Shivapooja, P. , Wang, Q. , Orihuela, B. , Rittschof, D. , López, G. P. , and Zhao, X. , 2013, “Bioinspired Surfaces With Dynamic Topography for Active Control of Biofouling,” Adv. Mater., 25(10), pp. 1430–143410.1002/adma.201203374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Hunt, G. W. , Peletier, M. A. , and Wadee, M. A. , 2000, “The Maxwell Stability Criterion in Pseudo-Energy Models of Kink Banding,” J. Struct. Geol., 22(5), pp. 669–68110.1016/S0191-8141(99)00182-0 [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Thompson, J. M. T. , and Hunt, G. W. , 1984, Elastic Instability Phenomena, Wiley, Chichester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Zeeman, E. C. , 1977, “Catastrophe Theory: Selected Papers, 1972–1977,” Addison-Wesley, London.

- [42]. Biot, M. A. , 1965, Mechanics of Incremental Deformations: Theory of Elasticity and Viscoelasticity of Initially Stressed Solids and Fluids, Including Thermodynamic Foundations and Applications to Finite Strain, Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Chater, E. , and Hutchinson, J. , 1984, “On the Propagation of Bulges and Buckles,” ASME J. Appl. Mech., 51(2), pp. 269–27710.1115/1.3167611 [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Zhao, X. , Hong, W. , and Suo, Z. , 2007, “Electromechanical Hysteresis and Coexistent States in Dielectric Elastomers,” Phys. Rev. B, 76(13), p. 134113.10.1103/PhysRevB.76.134113 [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Huang, R. , and Suo, Z. , 2012, “Electromechanical Phase Transition in Dielectric Elastomers,” Proc. R. Soc. A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Science, 468(2140), pp. 1014–104010.1098/rspa.2011.0452 [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Hunt, G. W. , Peletier, M. A. , Champneys, A. R. , Woods, P. D. , Ahmer Wadee, M. , Budd, C. J. , and Lord, G. , 2000, “Cellular Buckling in Long Structures,” Nonlinear Dyn., 21(1), pp. 3–2910.1023/A:1008398006403 [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Zhao, X. , 2012, “A Theory for Large Deformation and Damage of Interpenetrating Polymer Networks,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 60(2), pp. 319–33210.1016/j.jmps.2011.10.005 [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Williams, J. , 1997, “Energy Release Rates for the Peeling of Flexible Membranes and the Analysis of Blister Tests,” Int. J. Fracture, 87(3), pp. 265–28810.1023/A:1007314720152 [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Kendall, K. , 1971, “The Adhesion and Surface Energy of Elastic Solids,” J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 4(8), pp. 1186.10.1088/0022-3727/4/8/320 [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Wang, Q. , Suo, Z. , and Zhao, X. , 2012, “Bursting Drops in Solid Dielectrics Caused by High Voltages,” Nature Commun., 3, pp. 1157.10.1038/ncomms2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Biot, M. , 1963, “Surface Instability of Rubber in Compression,” Appl. Sci. Res., 12(2), pp. 168–18210.1007/BF03184638 [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Allen, H. G. , 1969, Analysis and Design of Structural Sandwich Panels, Pergamon, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Hohlfeld, E. , and Mahadevan, L. , 2011, “Unfolding the Sulcus,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 106(10), pp. 105702.10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.105702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Hohlfeld, E. , and Mahadevan, L. , 2012, “Scale and Nature of Sulcification Patterns,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 109(2), pp. 25701.10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.025701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55]. Hong, W. , Zhao, X. , and Suo, Z. , 2009, “Formation of Creases on the Surfaces of Elastomers and Gels,” Appl. Phys. Lett., 95(11), p. 111901.10.1063/1.3211917 [Google Scholar]

- [56]. Wong, W. , Guo, T. , Zhang, Y. , and Cheng, L. , 2010, “Surface Instability Maps for Soft Materials,” Soft Matter, 6(22), pp. 5743–575010.1039/c0sm00351d [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Wang, Q. , and Zhao, X. , 2013, “Creasing-Wrinkling Transition in Elastomer Films Under Electric Fields,” Phys. Rev. E, 88(4), p. 042403.10.1103/PhysRevE.88.042403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58]. Hutchinson, J. , and Suo, Z. , 1992, “Mixed Mode Cracking in Layered Materials,” Adv. Appl. Mech., 29, pp. 63–19110.1016/S0065-2156(08)70164-9 [Google Scholar]

- [59]. Yu, H. H. , and Hutchinson, J. W. , 2002, “Influence of Substrate Compliance on Buckling Delamination of Thin Films,” Int. J. Fracture, 113(1), pp. 39–5510.1023/A:1013790232359 [Google Scholar]

- [60]. Li, B. , Cao, Y.-P. , Feng, X.-Q. , and Gao, H. , 2012, “Mechanics of Morphological Instabilities and Surface Wrinkling in Soft Materials: A Review,” Soft Matter, 8(21), pp. 5728–574510.1039/c2sm00011c [Google Scholar]

- [61]. Kang, M. K. , and Huang, R. , 2010, “Swell-Induced Surface Instability of Confined Hydrogel Layers on Substrates,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 58(10), pp. 1582–159810.1016/j.jmps.2010.07.008 [Google Scholar]

- [62]. Wu, Z. , Bouklas, N. , and Huang, R. , 2013, “Swell-Induced Surface Instability of Hydrogel Layers with Material Properties Varying in Thickness Direction,” Int. J. Solids Struct., 50(3–4), pp. 578–58710.1016/j.ijsolstr.2012.10.022 [Google Scholar]

- [63]. Hutchinson, J. , He, M. , and Evans, A. , 2000, “The Influence of Imperfections on the Nucleation and Propagation of Buckling Driven Delaminations,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 48(4), pp. 709–73410.1016/S0022-5096(99)00050-2 [Google Scholar]

- [64]. Tallinen, T. , Biggins, J. , and Mahadevan, L. , 2013, “Surface Sulci in Squeezed Soft Solids,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 110(2), pp. 024302.10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.024302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65]. Huang, Z. , Hong, W. , and Suo, Z. , 2005, “Nonlinear Analyses of Wrinkles in a Film Bonded to a Compliant Substrate,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 53(9), pp. 2101–211810.1016/j.jmps.2005.03.007 [Google Scholar]

- [66]. Breid, D. , and Crosby, A. J. , 2011, “Effect of Stress State on Wrinkle Morphology,” Soft Matter, 7(9), pp. 4490–449610.1039/c1sm05152k [Google Scholar]

- [67]. Lin, P.-C. , and Yang, S. , 2007, “Spontaneous Formation of One-Dimensional Ripples in Transit to Highly Ordered Two-Dimensional Herringbone Structures Through Sequential and Unequal Biaxial Mechanical Stretching,” Appl. Phys. Lett., 90(24), p. 241903.10.1063/1.2743939 [Google Scholar]

- [68]. Audoly, B. , and Boudaoud, A. , 2008, “Buckling of a Stiff Film Bound to a Compliant Substrate—Part I: Formulation, Linear Stability of Cylindrical Patterns, Secondary Bifurcations,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 56(7), pp. 2401–242110.1016/j.jmps.2008.03.003 [Google Scholar]

- [69]. Audoly, B. , and Boudaoud, A. , 2008, “Buckling of a Stiff Film Bound to a Compliant Substrate—Part II: A Global Scenario for the Formation of Herringbone Pattern,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 56(7), pp. 2422–244310.1016/j.jmps.2008.03.002 [Google Scholar]

- [70]. Audoly, B. , and Boudaoud, A. , 2008, “Buckling of a Stiff Film Bound to a Compliant Substrate—Part III: Herringbone Solutions at Large Buckling Parameter,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids, 56(7), pp. 2444–245810.1016/j.jmps.2008.03.001 [Google Scholar]

- [71]. Song, J. , Jiang, H. , Choi, W. , Khang, D. , Huang, Y. , and Rogers, J. , 2008, “An Analytical Study of Two-Dimensional Buckling of Thin Films on Compliant Substrates,” J. Appl. Phys., 103(1), p. 014303.10.1063/1.2828050 [Google Scholar]

- [72]. Genzer, J. , and Groenewold, J. , 2006, “Soft Matter with Hard Skin: From Skin Wrinkles to Templating and Material Characterization,” Soft Matter, 2(4), pp. 310–32310.1039/b516741h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]