Abstract

Purpose

To estimate the prevalence of emotional distress in a large cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer and evaluate the interrelationship of risk factors including cancer-related late effects.

Methods

1,863 adult survivors of childhood cancer, median age of 32 years at follow-up, completed comprehensive medical evaluations. Clinically relevant emotional distress was assessed using the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 and was defined as T-scores ≥63. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using multivariable logistic regression models to identify risk factors for distress. Path analysis was used to examine associations among identified risk factors.

Results

Elevated global distress was reported by 15.1% of survivors. Cancer-related pain was associated with elevated distress (OR 8.72; 95% CI, 5.32 – 14.31). Survivors who reported moderate learning or memory problems were more likely to have elevated distress than survivors who reported no learning or memory problems (OR 3.27; 95% CI, 2.17 – 4.93). Path analysis implied that cancer-related pain has a direct effect on distress symptoms and an indirect effect through socioeconomic status and learning or memory problems. Similar results were observed for learning or memory problems.

Conclusions

Childhood cancer-related morbidities including pain and learning or memory problems appear to be directly and indirectly associated with elevated distress symptoms decades after treatment. Understanding these associations may help inform intervention targets for survivors of childhood cancer experiencing symptoms of distress.

Implications for cancer survivors

A subset of long-term childhood cancer survivors experience significant emotional distress. Physical and cognitive late effects may contribute to these symptoms.

Keywords: emotional distress, childhood cancer, survivorship, late effects

Introduction

Improvements in treatment regimens and care delivery over the past four decades have dramatically increased survival rates among children diagnosed with cancer [1]. The National Cancer Institute estimates that in the United States there were 363,000 survivors of childhood cancer in 2009 [2]. With the success of treatment there is a growing body of evidence from large cohort studies [3-6] that childhood cancer survivors may experience myriad physical and psychosocial late effects including chronic health conditions [7-10], physical impairment and disability [11-14], neurocognitive dysfunction [15-17] and symptoms of emotional distress [18-23].

Although, in general, survivors have not reported substantially different frequencies of emotional problems than have comparison groups without a cancer history, there are subgroups of survivors who appear vulnerable to increased risk of emotional distress [22]. Emotional distress in childhood cancer survivors may result in impaired quality of life [21, 24] and suicide ideation [25, 26]. Some of the risk factors associated with emotional distress in survivors are consistent with those observed in the general population, such as female sex, older age at evaluation, unemployment, lack of health insurance, low educational attainment and limitations in physical ability [27, 28, 21, 13, 11, 24, 23]. Previous studies have shown that cancer diagnosis [18, 11, 24] and cancer treatment [20, 21, 29] are also associated with emotional distress. However, the mechanisms underlying emotional distress still present many years after treatment completion are not clearly understood.

It is possible that the presence of adverse late-effects, rather than the remote cancer diagnosis or treatment history, influence survivors’ emotional well-being. Two plausible and potentially modifiable late effects that may be relevant are cancer-related pain [30, 7, 25] and learning or memory problems [31, 32]. Because there is limited literature investigating the direct association of these two cancer-related late-effects with emotional distress in survivors of childhood cancer and there are interventions available to remediate both cancer-related pain and learning or memory problems [33-37], an investigation of these associations is important. In addition, previous studies have generally focused only on the individual contribution of various risk factors to emotional distress and have not considered potential interrelations among them.

The purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence of emotional distress in a large cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer and to evaluate potential risk factors for emotional distress, such as cancer-related pain and learning or memory problems, and investigate their interrelations in a large cohort of adults treated for cancer during childhood.

Methods

Participants and procedure

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) has established a clinical cohort of survivors of childhood cancer, the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE), who were treated at SJCRH, survived at least 10 years after diagnosis and are 18 years of age or older at enrollment [38]. Clinical assessment in SJLIFE includes a risk-based screening evaluation consistent with the Children’s Oncology Group Long Term Follow-up Guidelines [39, 40]. Participants undergo various evaluations including ascertainment of health history, physical examinations, laboratory assessments, and physical performance assessment including aerobic capacity, sensation, flexibility, balance, muscle strength, mobility, and gross and fine motor function. Protocol enrollment started in December 2007 and is ongoing. The current study included all eligible SJLIFE participants enrolled as of April 30, 2012 who completed surveys assessing interval medical events and emotional distress, as well as a clinical visit and functional evaluation (n=1,863).

Primary outcome

Emotional distress was assessed using the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18) [41], which asks respondents to rate their level of distress within the previous 7 days. The BSI-18 is a self-report symptom checklist that has been widely used as a screening tool for emotional distress in the general medical population, and in the context of cancer patients and cancer survivors [42-45]. The BSI-18 includes three subscales, anxiety, depression and somatization, and a summary score, the Global Severity Index (GSI). The GSI and subscale scores were converted to T-scores using sex-specific normative data [41]. T-scores ≥ 63 were considered to represent clinically relevant emotional distress. This cut-off point has been widely used to define elevated emotional distress in childhood cancer survivors [22, 17]. The values of GSI and the subscale scores were coded in the analyses as 1 for elevated distress and 0 for non-elevated distress.

Independent variables

Cancer-related variables included self-reported cancer-related pain quantified on a 5-point scale (1 = very bad, excruciating pain and 5 = no pain) and self-reported learning or memory problems quantified on a 4-point scale (1 = severe or disabling problem and 4 = no problem). The survey questionnaire completed by participants combined learning and memory problems into a single question, making it not possible to distinguish the two from each other.

Sex, race, age at the time of SJLIFE evaluation and socioeconomic status (SES) were also considered as independent variables in the models. Factorial validity of SES as a latent variable was determined through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Socioeconomic factors used to construct this variable included educational attainment quantified on a 4-point scale (1 = did not graduate from high school and 4 = college graduate or post-graduate level); employment status quantified on a 3-point scale (1 = unable to work due to illness or disability and 3 = caring for home or family (not seeking paid work), or student, or retired, or working part or full time); and health insurance quantified on a 3-point scale (1 = none and 3 = Canadian resident, or through spouse’s or parent’s policy, or through place of employment, or through self-purchased policy).

Physical ability factors included functional mobility, balance, and hand grip strength, and were measured by a trained exercise physiologist. Functional mobility was evaluated by the 6-minute walk test (6MW) [46]. The distance walked was recorded in meters and analyzed as a continuous variable. Balance was measured by the sensory organization test (SOT) [47, 48], and grip strength (in kilograms) was measured using a Jamar hand grip dynamometer [49]. For hand grip strength, each participant completed three trials and the maximum value between left and right hands was computed for this analysis.

Statistical analysis

Bivariable logistic regression models were used to identify variables associated with a GSI ≥ 63 as an indicator of elevated emotional distress. Factors significant at the p < 0.1 level in bivariable analyses were selected for inclusion in the multivariable logistic regression models, to calculate odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Sequential regression imputation was used with ten replications [50, 51] for missing data on five potential risk factors: cancer-related pain (1.56% missing), learning or memory problems (2.04% missing), education (2.58% missing), employment (0.38% missing) and health insurance (0.27% missing). For bivariable and multivariable logistic regression, the jackknife repeated replication method was applied to estimate variances [52]. Both direct and indirect effects were examined using path analysis to evaluate the predictors of global distress. A two-step procedure [53] was used to first find an acceptable model fit in confirmatory factor analysis and then to modify and alter the model to assure the best representation of the theoretical model of interest. The maximum likelihood estimation method was used to evaluate models and to estimate the parameters of the individual independent variables. The best fitting model was based on established structural equation modeling (SEM) fit criteria: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMSR), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted GFI (AGFI), Bentler Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Bentler-Bonett Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI). Values of GFI, AGFI, CFI and NNFI ≥ 0.9 indicate an adequate adjustment, values of RMSEA ≤ 0.07 and SRMSR ≤ 0.05 suggest a good model fit [54-58]. All of the statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.2. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Study sample

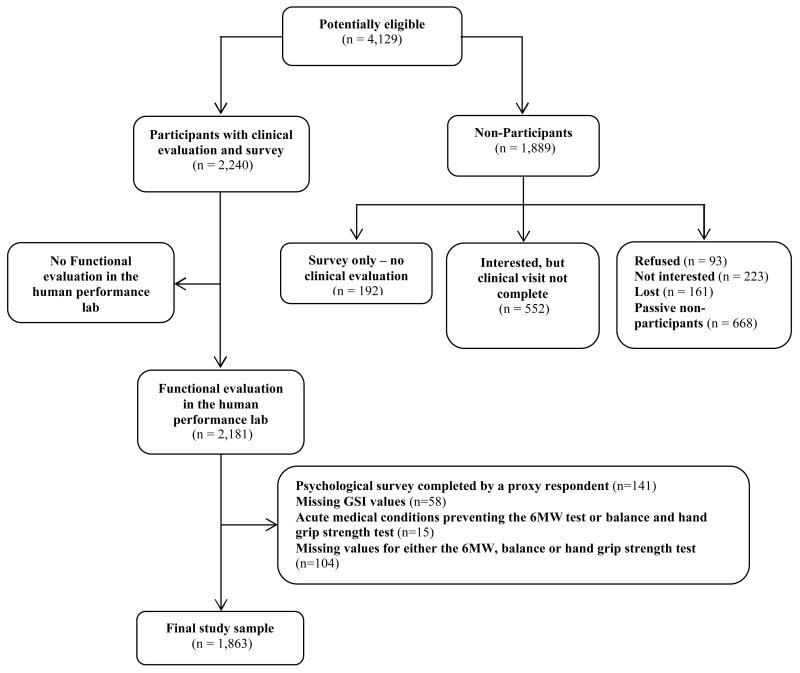

Of the 4,129 potentially eligible survivors for this study (Figure 1), 2,240 completed the surveys and a clinical SJLIFE visit. SJLIFE participants with a clinical visit were largely similar compared to non-participants on key demographic variables including sex (51% vs. 58% males, respectively), race (86% vs. 82% white, respectively) and age at primary cancer diagnosis (median age 7 years for participants and non-participants). The distribution of childhood cancer diagnoses was also similar between the two groups, with a slightly larger percentage of leukemia diagnoses among participants (41% vs. 34%). Of the 2,240 SJLIFE participants, 59 (3%) did not complete a functional evaluation, 58 (3%) had missing GSI values, 141 (6%) had the BSI-18 completed by a proxy respondent, 15 (1%) had acute medical conditions which would not allow them to perform the 6MW, balance and hand grip strength tests, and 104 (5%) had missing values for either the 6MW, balance or hand grip strength. Therefore the final study sample size was 1863 (83.2% of SJLIFE participants with a clinical visit). The characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Analysis-specific consort diagram of study participation from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Sample (n=1863)

| Characteristic | Median | Interquartile Range |

|---|---|---|

| Global severity index (T-score) | 48 | 42 - 58 |

| Anxiety (T-score) | 47 | 39 - 57 |

| Depression (T-score) | 45 | 42 - 59 |

| Somatization (T-score) | 48 | 42 - 59 |

| Age at clinical evaluation (years) | 32 | 26 - 38 |

| 6 minute walk test distance (meters) | 575 | 511 - 645 |

| Balance a (percentage) | 80 | 74 - 84 |

| Maximum hand grip strength (Kg) | 38 | 29 - 50 |

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 935 | 50.2 |

| Male | 928 | 49.8 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1617 | 86.8 |

| Non-white | 246 | 13.2 |

| Education | ||

| Did not graduate from high school | 162 | 8.7 |

| Completed high school/GED or received training after high school | 419 | 22.5 |

| Some college | 526 | 28.2 |

| College graduate or post-graduate level | 708 | 38.0 |

| Number missing | 48 | 2.6 |

| Employment | ||

| Unable to work due to illness or disability | 78 | 4.2 |

| Never had a job, or not currently working or unemployed and looking for work |

338 | 18.1 |

| Caring for home or family (not seeking paid work), or student, or retired, or working part or full time |

1440 | 77.3 |

| Number missing | 7 | 0.4 |

| Health insurance | ||

| None | 401 | 21.5 |

| Through Medicare or Medicaid or other public assistance program, or military dependent/veteran’s benefits (CHAMPUS) |

235 | 12.6 |

| Canadian resident, or through spouse’s or parent’s policy, or through place of employment, or through self-purchased policy |

1222 | 65.6 |

| Number missing | 5 | 0.3 |

| Cancer-related pain | ||

| Very bad, excruciating pain | 25 | 1.3 |

| A lot of pain | 98 | 5.3 |

| Medium amount of pain | 175 | 9.4 |

| Small amount of pain | 300 | 16.1 |

| No pain | 1236 | 66.3 |

| Number missing | 29 | 1.6 |

| Learning or memory problems | ||

| Severe or disabling problem | 22 | 1.2 |

| Moderate problem | 181 | 9.7 |

| Mild problem | 214 | 11.5 |

| No problem | 1408 | 75.6 |

| Number missing | 38 | 2.0 |

| Global emotional distress | 281 | 15.1 |

| Anxiety | 218 | 11.7 |

| Depression | 279 | 15.0 |

| Somatization | 331 | 17.8 |

Balance was measured via sensory organization test (SOT). A difference score was computed from the normal range of anterior-posterior sway, and the maximum range of sway from three trials was averaged and expressed as a percentage.

Prevalence of distress

The percentage of survivors reporting an elevated level of global emotional distress (GSI) was 15.1%. Elevated levels on the individual anxiety, depression and somatization subscales were reported by 11.7%, 15.0% and 17.8% of survivors, respectively.

Bivariable regression analyses

The results of the bivariable logistic regression models are presented in Table 2. Factors associated with an increase of the relative odds of global emotional distress included survivor report of any degree of cancer-related pain and at least mild learning or memory problems. For each incremental unit increase of the 6 minute walk test, balance test and maximum hand grip strength test, there was a decrease in the relative odds of global emotional distress.

Table 2.

Bivariable associations between risk factors and emotional distress

| Total N = 1863 |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | GSIb | Anxietyb | Depressionb | Somatizationb | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Cases | OR | 95% CI | Cases | OR | 95% CI | Cases | OR | 95% CI | Cases | OR | 95% CI | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 136 | 1.00 | 101 | 1.00 | 119 | 1.00 | 183 | 1.00 | ||||

| Male | 145 | 1.09 | 0.84 - 1.40 | 117 | 1.19 | 0.90 - 1.58 | 160 | 1.43 | 1.11 - 1.85 | 148 | 0.78 | 0.61 - 0.99 |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White | 236 | 1.00 | 187 | 1.00 | 244 | 1.00 | 282 | 1.00 | ||||

| Non-white | 45 | 1.31 | 0.92 - 1.86 | 31 | 1.10 | 0.74 - 1.66 | 35 | 0.93 | 0.64 - 1.37 | 49 | 1.18 | 0.84 - 1.65 |

| Educationa | ||||||||||||

| Did not graduate from high school | 43 | 3.62 | 2.36 - 5.55 | 33 | 3.08 | 1.92 - 4.93 | 36 | 2.71 | 1.73 - 4.23 | 56 | 4.48 | 3.00 - 6.69 |

| Completed high school/GED or received training after high school |

84 | 2.49 | 1.76 - 3.53 | 62 | 2.09 | 1.42 - 3.07 | 85 | 2.38 | 1.69 - 3.35 | 99 | 2.65 | 1.89 - 3.70 |

| Some college | 76 | 1.73 | 1.22 - 2.45 | 60 | 1.57 | 1.07 - 2.30 | 78 | 1.67 | 1.18 - 2.35 | 90 | 1.80 | 1.30 - 2.51 |

| College graduate or post-graduate level | 65 | 1.00 | 54 | 1.00 | 69 | 1.00 | 74 | 1.00 | ||||

| Employment a | ||||||||||||

| Unable to work due to illness or disability | 36 | 6.64 | 4.13 - 10.67 | 28 | 5.82 | 3.54 - 9.58 | 28 | 4.21 | 2.58 - 6.87 | 40 | 6.87 | 4.30 - 11.00 |

| Never had a job, or not currently working or unemployed and looking for work |

79 | 2.35 | 1.74 - 3.18 | 62 | 2.32 | 1.67 - 3.23 | 80 | 2.31 | 1.72 - 3.12 | 96 | 2.58 | 1.95 - 3.42 |

| Caring for home or family (not seeking paid work), or student, or retired, or working part or full time |

165 | 1.00 | 127 | 1.00 | 170 | 1.00 | 193 | 1.00 | ||||

| Health insurance a | ||||||||||||

| None | 88 | 2.26 | 1.68 - 3.04 | 70 | 2.18 | 1.58 - 3.02 | 83 | 1.97 | 1.46 - 2.65 | 93 | 2.09 | 1.57 - 2.79 |

| Through Medicare or Medicaid or other public assistance program, or military dependent/veteran’s benefits (CHAMPUS) |

58 | 2.64 | 1.87 - 3.73 | 40 | 2.12 | 1.43 - 3.14 | 53 | 2.20 | 1.55 - 3.13 | 84 | 3.86 | 2.81 - 5.29 |

| Canadian resident, or through spouse’s or parent’s policy, or through place of employment, or through self-purchased policy |

135 | 1.00 | 108 | 1.00 | 143 | 1.00 | 154 | 1.00 | ||||

| Cancer-related pain a | ||||||||||||

| Very bad, excruciating pain | 15 | 16.56 | 7.22 – 38.00 | 13 | 15.97 | 7.04 - 36.23 | 13 | 9.27 | 4.17 - 20.61 | 20 | 45.27 | 16.62 - 123.34 |

| A lot of pain | 56 | 14.60 | 9.34 - 22.80 | 38 | 9.41 | 5.91 - 14.96 | 45 | 7.53 | 4.87 - 11.64 | 68 | 25.68 | 15.91 - 41.42 |

| Medium amount of pain | 42 | 3.51 | 2.35 - 5.24 | 33 | 3.47 | 2.23 - 5.39 | 33 | 2.07 | 1.36 - 3.14 | 67 | 7.16 | 4.94 - 10.39 |

| Small amount of pain | 54 | 2.43 | 1.69 - 3.49 | 45 | 2.62 | 1.76 - 3.90 | 56 | 2.02 | 1.43 - 2.86 | 65 | 3.13 | 2.22 - 4.42 |

| No pain | 103 | 1.00 | 79 | 1.00 | 126 | 1.00 | 99 | 1.00 | ||||

| Learning or memory problems a | ||||||||||||

| Severe or disabling problem | 12 | 10.03 | 4.26 - 23.58 | 8 | 5.71 | 2.37 - 13.74 | 14 | 14.46 | 5.97 - 35.02 | 14 | 11.75 | 4.85 - 28.46 |

| Moderate problem | 59 | 4.02 | 2.82 - 5.73 | 42 | 3.03 | 2.05 - 4.48 | 64 | 4.56 | 3.22 - 6.47 | 57 | 3.04 | 2.15 - 4.30 |

| Mild problem | 50 | 2.50 | 1.75 - 3.57 | 33 | 1.80 | 1.19 - 2.71 | 41 | 1.96 | 1.35 - 2.86 | 65 | 2.92 | 2.1 - 4.05 |

| No problem | 153 | 1.00 | 130 | 1.00 | 152 | 1.00 | 185 | 1.00 | ||||

| Age at clinical evaluation | 281 | 1.030 | 1.014 - 1.045 | 218 | 1.020 | 1.003 - 1.038 | 279 | 1.019 | 1.003 - 1.035 | 331 | 1.029 | 1.014 - 1.044 |

| 6 minute walk test distance | 281 | 0.996 | 0.995 - 0.997 | 218 | 0.998 | 0.996 - 0.999 | 279 | 0.997 | 0.996 - 0.998 | 331 | 0.996 | 0.995 - 0.997 |

| Balance | 281 | 0.973 | 0.961 - 0.984 | 218 | 0.977 | 0.964 - 0.990 | 279 | 0.975 | 0.964 - 0.987 | 331 | 0.963 | 0.952 - 0.974 |

| Maximum hand grip strength | 281 | 0.991 | 0.981 - 1.001 | 218 | 1.000 | 0.989 - 1.01 | 279 | 0.999 | 0.989 - 1.009 | 331 | 0.982 | 0.972 - 0.991 |

Number of cases equals those with no missing variable values. Results include multiple imputation with ten replications for missing data.

T-scores ≥ 63 were defined as elevated distress. OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval. ORs greater than 1 indicate a greater likelihood of reporting emotional distress. Bold font indicates statistically significant association (p<0.05).

Multivariable analyses

Factors significantly associated with global distress in the multivariable models are presented in Table 3. Survivors who completed high school/GED or received training after high school other than college were more likely to have an elevated global distress compared to survivors who completed college or post-graduate education (OR 1.65; 95% CI, 1.10 – 2.48). Survivors unable to work due to illness or disability were more likely to have an elevated global emotional distress than survivors who were not seeking paid work, a current student or retired, or working at least part time (OR 1.83; 95% CI, 1.01 – 3.34). Survivors not having any type of medical insurance were more likely to have an elevated level of global emotional distress compared to those having medical insurance other than Medicare, Medicaid, military dependent/veteran’s benefits (CHAMPUS) or other public assistance program (OR 1.60; 95% CI, 1.11 – 2.32).

Table 3.

Multivariable associations between risk factors and emotional distress

| Total N = 1863 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | GSIa | Anxietya | Depressiona | Somatizationa | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | — — | — — — — | — — | — — — — | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Male | — — | — — — — | — — | — — — — | 1.56 | 1.17 - 2.09 | 0.91 | 0.57 - 1.43 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Did not graduate high school | 1.58 | 0.93 - 2.69 | 1.44 | 0.82 - 2.55 | 1.16 | 0.68 - 1.97 | 2.21 | 1.30 - 3.74 |

| Completed high school/GED or received training after high school |

1.65 | 1.10 - 2.48 | 1.43 | 0.92 - 2.21 | 1.52 | 1.03 - 2.24 | 1.90 | 1.26 - 2.86 |

| Some college | 1.45 | 0.97 - 2.16 | 1.29 | 0.85 - 1.98 | 1.37 | 0.94 - 2.01 | 1.56 | 1.05 - 2.32 |

| College graduate or post-graduate level | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Unable to work due to illness or disability | 1.83 | 1.01 - 3.34 | 2.17 | 1.18 - 4.01 | 1.37 | 0.74 - 2.52 | 1.26 | 0.68 - 2.34 |

| Never had a job, or not currently working or unemployed and looking for work |

1.20 | 0.82 - 1.77 | 1.41 | 0.94 - 2.11 | 1.39 | 0.96 - 2.02 | 1.10 | 0.75 - 1.61 |

| Caring for home or family (not seeking paid work), or student, or retired, or working part or full time |

1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Health insurance | ||||||||

| None | 1.60 | 1.11 - 2.32 | 1.47 | 0.99 - 2.19 | 1.32 | 0.92 - 1.89 | 1.43 | 0.98 - 2.09 |

| Through Medicare or Medicaid or other public assistance program, or military dependent/veteran’s benefits (CHAMPUS) |

1.07 | 0.67 - 1.71 | 0.85 | 0.52 - 1.42 | 1.01 | 0.64 - 1.60 | 1.56 | 1.02 - 2.44 |

| Canadian resident, or through spouse’s or parent’s policy, or through place of employment, or through self- purchased policy |

1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Cancer-related pain | ||||||||

| Very bad, excruciating pain | 10.83 | 4.42 - 26.50 | 11.11 | 4.60 - 26.82 | 6.63 | 2.76 - 15.90 | 27.67 | 9.49 - 80.65 |

| A lot of pain | 8.72 | 5.32 - 14.31 | 5.84 | 3.49 - 9.76 | 4.50 | 2.75 - 7.36 | 16.91 | 9.94 - 28.79 |

| Medium amount of pain | 2.38 | 1.53 - 3.71 | 2.69 | 1.68 - 4.33 | 1.41 | 0.89 - 2.23 | 5.13 | 3.41 - 7.69 |

| Small amount of pain | 1.97 | 1.34 - 2.90 | 2.30 | 1.51 - 3.49 | 1.71 | 1.18 - 2.47 | 2.57 | 1.78 - 3.71 |

| No pain | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Learning or memory problems | ||||||||

| Severe or disabling problem | 5.79 | 2.14 - 15.72 | 2.78 | 1.01 - 7.70 | 9.73 | 3.71 - 25.56 | 6.29 | 2.14 - 18.53 |

| Moderate problem | 3.27 | 2.17 - 4.93 | 2.29 | 1.48 - 3.54 | 4.00 | 2.71 - 5.91 | 2.07 | 1.35 - 3.17 |

| Mild problem | 2.26 | 1.52 - 3.36 | 1.49 | 0.96 - 2.33 | 1.86 | 1.24 - 2.78 | 2.57 | 1.75 - 3.77 |

| No problem | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Age at clinical evaluation | 1.036 | 1.017 - 1.055 | 1.021 | 1.001 - 1.041 | 1.027 | 1.008 - 1.045 | 1.032 | 1.014 - 1.051 |

T-scores ≥ 63 were defined as elevated distress. OR = Odds Ratio, CI = Confidence Interval. ORs greater than 1 indicate a greater likelihood of reporting emotional distress.

Bold font indicates statistically significant association (p<0.05).

Cancer-related pain, learning or memory problems and age at evaluation were all associated with global emotional distress. The relative odds of emotional distress increased with increasing level of pain. Those who self-reported a lot of cancer-related pain were more likely to have elevated global emotional distress than survivors reporting no cancer-related pain (OR 8.72; 95% CI, 5.32 – 14.31). Similarly, the relative odds of emotional distress increased with increasing level of learning or memory problems. Survivors who self-reported moderate learning or memory problems were more likely to have elevated global emotional distress than survivors reporting no learning or memory problems (OR 3.27; 95% CI, 2.17 – 4.93). Each one year increase in survivor age at evaluation was associated with a 4% increase in the predicted odds of global distress. Conversely, after accounting for age at evaluation, socioeconomic and cancer-related factors, none of the physical ability factors (6MW, balance and maximum hand grip strength) were significantly associated with global distress. For this reason none of the physical ability variables were included in the path analysis for global distress.

Path analysis

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis showed that three indicator variables, education, health insurance and employment, can be grouped into one latent construct representing SES. Standardized factor loadings for the three indicators were 0.54, 0.56 and 0.58 respectively and support the convergent validity of the indicators [53]. Path analysis was performed for the global emotional distress as the outcome variable and also individually for each subscale (anxiety, depression and somatization). Since no substantive differences were observed among the four path analyses, only the results obtained for the global emotional distress are presented. The path analysis with one latent variable and the best fitting model are presented in Figure 2. The corresponding performance indices for this model showed a good fit: RMSEA=0.07; SRMSR=0.04; GFI=0.99; AGFI=0.95; CFI=0.93; NNFI=0.82. The standardized path coefficients are presented in Figure 2. Variables loading into the SES, cancer-related pain and learning or memory problems were defined with values increasing from the worst possible outcome to the best possible outcome (e.g. very bad, excruciating pain to no pain at all). Therefore, an increase in age (β=0.10), lower levels of learning or memory problems (β=0.20) and less cancer-related pain (β=0.34) were associated with higher SES. Higher SES (β = −0.19), less cancer-related pain (β = −0.25) and lower levels of learning or memory problems (β = −0.16) were associated with lower global emotional distress.

Fig. 2.

Path analysis for associations with emotional distress as measured by the Global Severity Index (GSI)

Note: The directly observed variables are illustrated as rectangles. Socioeconomic status represents a latent variable. GSI T-scores ≥ 63 were considered elevated.

Discussion

This study examined factors and pathways leading to emotional distress in a large cohort of adult survivors of childhood cancer. Overall, 15% of the study sample reported elevated emotional distress. Cancer-related pain and learning or memory problems were also risk factors for emotional distress. These results highlight the potential influence of cancer-related late-effects on emotional functioning in long-term survivors of childhood cancer.

Consistent with previous reports, the majority of survivors in our sample did not report elevated symptoms of emotional distress, suggesting largely positive emotional adjustment several decades following diagnosis and treatment for childhood cancer. However, compared to previous estimates from the US Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (US CCSS) [21] there was a slightly larger proportion of survivors reporting elevated symptoms of global emotional distress (GSI 15% vs. 12%). A recent study from the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (Swiss CCSS) also reported higher levels of distress compared to the US CCSS (GSI 14.4% vs. 12%) [23]. The percentage of survivors in our study reporting elevated global distress was slightly higher than expected compared to published normative data (15% vs. 10%, respectively) [41]. However, this direct comparison may not be appropriate as the BSI-18 normative data are derived from a community sample of employed adults whereas a sizeable proportion of our sample was unemployed. A comparison of distress among employed survivors and normative data (GSI 9% vs. 10%, respectively) reveals more consistent levels of distress across groups. Notably in our study, mean levels of emotional distress across all subscales (depression: 49.99; anxiety: 48.75; somatization: 51.21) were similar to the US population norms (valued at 50 for all three subscales). This parallels the patterns observed in both the US and Swiss CCSS cohorts.

Self-report of very bad or excruciating cancer-related pain was associated with a 10.8 fold increased likelihood of elevated emotional distress compared to report of no pain, while report of severe or disabling learning or memory problems was associated with a 5.8 increased likelihood of elevated distress compared to report of no learning or memory problems. Past studies have also suggested an association between cancer-related pain and emotional distress in survivors of adult cancer onset [59-61]; however, only a limited number of studies have assessed this association in survivors of childhood cancer. Others have observed an association of symptoms of depression [26] and cancer-related pain [25] and suicide ideation. Additionally, limited data exist to support the direct association between learning or memory problems and emotional distress in survivors of childhood cancer. A significant proportion of childhood cancer survivors may experience neurocognitive impairment in domains such as attention, memory and processing speed [31, 32]. Survivors of a brain tumor diagnosed at a young age (<6 years old) and survivors of leukemia, especially those who received cranial radiation, are at increased risk of neurocognitive impairment [15, 17, 62], reduced mental quality of life [21] and emotional distress [19].

Results from the path analysis suggest that cancer-related pain has a direct effect on symptoms of distress, yet may also operate indirectly through SES and learning or memory problems. Similarly, learning or memory problems evidenced a direct effect on emotional distress as well as an indirect effect through SES. This is not surprising given what is known from the extant literature. Specifically, cancer-related pain [7, 30, 63] and learning or memory problems [17, 15] have been previously associated with low SES in survivors of childhood cancer. Moreover, low SES has been associated with increased risk for emotional distress in cancer survivors [22, 19, 18].

Importantly, both cancer-related pain and learning or memory problems are potentially amenable to intervention. Cognitive remediation approaches have shown promise in treating cognitive late effects of childhood cancer treatment [33-35], while pharmacologic, cognitive-behavioral, and complementary medicine approaches have been used for the management of cancer-related pain [36, 37]. Intervening on factors that contribute to emotional distress may have the potential to reduce the burden of distress symptoms in survivors, though future research will need to explore such associations. However, it will be important for primary health care providers to inquire about symptoms of pain in this at-risk group as early identification of symptoms may lead to timely pain management. The Pain Thermometer is an example of a single-dimension screening measure that could be incorporated into regular follow-up care for survivors of childhood cancer [64]. Similarly, health care providers could incorporate the Distress Thermometer [65], a brief screening tool for emotional symptoms [66]. The feasibility and reliability of brief neurocognitive screenings for cancer survivors has also been demonstrated [67]. These screening methods provide means of possible identification of survivors at-risk for adverse psychological and cognitive outcomes who may benefit from referral to more specialized and/or comprehensive care.

The present findings should be considered in the context of certain limitations. First, differences in those who participated in this study versus those who did not participate may be a source of selection bias. Although not directly assessable, SJLIFE participants with a clinical visit in this analysis were similar on key demographic variables than were non-participants presumed to be eligible for participation. This finding is consistent with previously reported results from a comprehensive evaluation of potential participation bias from the SJLIFE cohort [68], which somewhat reduces concern about possible differential participation. Another potential limitation centers on the measurement of emotional distress. The BSI-18 assesses acute symptoms of distress over the previous 7 days. This narrow reporting window may result in an underestimation of survivors who experience distress, since distress symptoms may fluctuate over time. In addition, cancer-related pain and learning or memory problems were each assessed using a single item. If learning and memory problems reflect different constructs, one cannot differentiate the contributions of each, given the structure of the single question in the survey. It should also be noted that because of the cross-sectional nature of this study one cannot be certain of the temporal association between the identified risk factors and symptoms of emotional distress.

In summary, this study extends previous findings by reporting on cancer-related late-effects that may directly and indirectly result in elevated symptoms of emotional distress many years after cancer treatment. Understanding the contribution of cancer-related risk factors to emotional distress, as well as the interplay between these and established risk factors, may help inform intervention targets for survivors of childhood cancer experiencing significant distress symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the Cancer Center Support (CORE) grant CA 21765 from the National Cancer Institute and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Nothing to report

References

- 1.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, Stein K, Mariotto A, Smith T, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, Breslow NE, Donaldson SS, Green DM, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38(4):229–39. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw AK, Morrison HI, Speechley KN, Maunsell E, Barrera M, Schanzer D, et al. The late effects study: design and subject representativeness of a Canadian, multi-centre study of late effects of childhood cancer. Chronic Dis Can. 2004;25(3-4):119–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkins MM, Lancashire ER, Winter DL, Frobisher C, Reulen RC, Taylor AJ, et al. The British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: Objectives, methods, population structure, response rates and initial descriptive information. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(5):1018–25. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuehni CE, Rueegg CS, Michel G, Rebholz CE, Strippoli MP, Niggli FK, et al. Cohort profile: the swiss childhood cancer survivor study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(6):1553–64. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Hobbie W, Chen H, Gurney JG, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(12):1583–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diller L, Chow EJ, Gurney JG, Hudson MM, Kadin-Lottick NS, Kawashima TI, et al. Chronic disease in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort: a review of published findings. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2339–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, Mulrooney DA, Chemaitilly W, Krull KR, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(22):2371–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ness KK, Gurney JG, Zeltzer LK, Leisenring W, Mulrooney DA, Nathan PC, et al. The impact of limitations in physical, executive, and emotional function on health-related quality of life among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(1):128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ness KK, Mertens AC, Hudson MM, Wall MM, Leisenring WM, Oeffinger KC, et al. Limitations on physical performance and daily activities among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(9):639–47. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-9-200511010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ness KK, Baker KS, Dengel DR, Youngren N, Sibley S, Mertens AC, et al. Body composition, muscle strength deficits and mobility limitations in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(7):975–81. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ness KK, Gurney JG. Adverse late effects of childhood cancer and its treatment on health and performance. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:279–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellenberg L, Liu Q, Gioia G, Yasui Y, Packer RJ, Mertens A, et al. Neurocognitive status in long-term survivors of childhood CNS malignancies: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(6):705–17. doi: 10.1037/a0016674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edelstein K, Spiegler BJ, Fung S, Panzarella T, Mabbott DJ, Jewitt N, et al. Early aging in adult survivors of childhood medulloblastoma: long-term neurocognitive, functional, and physical outcomes. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(5):536–45. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadan-Lottick NS, Zeltzer LK, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Ellenberg L, Gioia G, et al. Neurocognitive functioning in adult survivors of childhood non-central nervous system cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(12):881–93. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zebrack BJ, Gurney JG, Oeffinger K, Whitton J, Packer RJ, Mertens A, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood brain cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(6):999–1006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zebrack BJ, Zeltzer LK, Whitton J, Mertens AC, Odom L, Berkow R, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1):42–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zebrack BJ, Zevon MA, Turk N, Nagarajan R, Whitton J, Robison LL, et al. Psychological distress in long-term survivors of solid tumors diagnosed in childhood: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(1):47–51. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeltzer LK, Lu Q, Leisenring W, Tsao JC, Recklitis C, Armstrong G, et al. Psychosocial outcomes and health-related quality of life in adult childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(2):435–46. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, Zebrack B, Casillas J, Tsao JC, et al. Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2396–404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michel G, Rebholz CE, von der Weid NX, Bergstraesser E, Kuehni CE. Psychological distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer: the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(10):1740–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nathan PC, Ness KK, Greenberg ML, Hudson M, Wolden S, Davidoff A, et al. Health-related quality of life in adult survivors of childhood Wilms tumor or neuroblastoma: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(5):704–15. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Recklitis CJ, Diller LR, Li X, Najita J, Robison LL, Zeltzer L. Suicide ideation in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):655–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.8635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brinkman TM, Liptak CC, Delaney BL, Chordas CA, Muriel AC, Manley PE. Suicide ideation in pediatric and adult survivors of childhood brain tumors. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miech RA, Power C, Eaton WW. Disparities in psychological distress across education and sex: a longitudinal analysis of their persistence within a cohort over 19 years. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(4):289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miech RA, Shanahan MJ. Socioeconomic status and depression over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(2):162–76. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Recklitis CJ, O’Leary T, Diller L. Utility of routine psychological screening in the childhood cancer survivor clinic. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(5):787–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu Q, Krull KR, Leisenring W, Owen JE, Kawashima T, Tsao JC, et al. Pain in long-term adult survivors of childhood cancers and their siblings: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pain. 2011;152(11):2616–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moleski M. Neuropsychological, neuroanatomical, and neurophysiological consequences of CNS chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2000;15(7):603–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulhern RK, Fairclough D, Ochs J. A prospective comparison of neuropsychologic performance of children surviving leukemia who received 18-Gy, 24-Gy, or no cranial irradiation. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9(8):1348–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.8.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou P, Li Y, Conklin HM, Mulhern RK, Butler RW, Ogg RJ. Evidence of change in brain activity among childhood cancer survivors participating in a cognitive remediation program. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;27(8):915–29. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acs095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butler RW, Copeland DR, Fairclough DL, Mulhern RK, Katz ER, Kazak AE, et al. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial of a cognitive remediation program for childhood survivors of a pediatric malignancy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(3):367–78. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuurs A, Green HJ. A feasibility study of group cognitive rehabilitation for cancer survivors: enhancing cognitive function and quality of life. Psycho-oncology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/pon.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwekkeboom KL, Cherwin CH, Lee JW, Wanta B. Mind-body treatments for the pain-fatigue-sleep disturbance symptom cluster in persons with cancer. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2010;39(1):126–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moryl N, Coyle N, Essandoh S, Glare P. Chronic pain management in cancer survivors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(9):1104–10. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Nolan VG, Armstrong GT, Green DM, Morris EB, et al. Prospective medical assessment of adults surviving childhood cancer: study design, cohort characteristics, and feasibility of the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56(5):825–36. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, Forte KJ, Sweeney T, Hester AL, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children’s Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(24):4979–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.COG . Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers. Children’s Oncology Group; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. NCS Pearson; Minneapolis, MN: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zabora JR, Smith-Wilson R, Fetting JH, Enterline JP. An efficient method for psychosocial screening of cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(2):192–6. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(90)72194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Jacobsen P, Curbow B, Piantadosi S, Hooker C, et al. A new psychosocial screening instrument for use with cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(3):241–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, Fleishman SB, Zabora J, Baker F, et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1494–502. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Recklitis CJ, Parsons SK, Shih MC, Mertens A, Robison LL, Zeltzer L. Factor structure of the brief symptom inventory--18 in adult survivors of childhood cancer: results from the childhood cancer survivor study. Psychol Assess. 2006;18(1):22–32. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crapo RO, Casaburi R, Coates AL, Enright P, MacIntyre N, McKay R, et al. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(1):111–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.NeuroCom . NeuroCom International Inc. SOT Norms. Neurocom International Inc.; Clackamas, OR: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.NeuroCom . Setting the standard in balance and mobility: SMART Equitest. NeuroCom; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Volland G, Kashman N. Reliability and validity of grip and pinch strength evaluations. The Journal of Hand Surgery. 1984;9(2):222–6. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80146-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Survey methodology. 2001;27(1):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kish L, Frankel MR. Inference from complex samples. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1974;36(1):1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modelling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103(3):411–23. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marsh HW, Hau K, Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11(3):320–41. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weston R, Gore PA. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist. 2006;34(5):719–51. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steiger JH. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42(5):893–8. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maunsell E, Brisson J, Deschenes L. Arm problems and psychological distress after surgery for breast cancer. Can J Surg. 1993;36(4):315–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keefe FJ, Abernethy AP, Campbell LC. Psychological approaches to understanding and treating disease-related pain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:601–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burton AW, Fanciullo GJ, Beasley RD, Fisch MJ. Chronic pain in the cancer survivor: a new frontier. Pain Med. 2007;8(2):189–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krull KR, Gioia G, Ness KK, Ellenberg L, Recklitis C, Leisenring W, et al. Reliability and validity of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Neurocognitive Questionnaire. Cancer. 2008;113(8):2188–97. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Punyko JA, Gurney JG, Scott Baker K, Hayashi RJ, Hudson MM, Liu Y, et al. Physical impairment and social adaptation in adult survivors of childhood and adolescent rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivors Study. Psycho-oncology. 2007;16(1):26–37. doi: 10.1002/pon.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Butt Z, Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, Paice JA, Peterman AH, Shevrin D, et al. Use of a single-item screening tool to detect clinically significant fatigue, pain, distress, and anorexia in ambulatory cancer practice. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2008;35(1):20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, Peabody E, Scher HI, Holland JC. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82(10):1904–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980515)82:10<1904::aid-cncr13>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Recklitis CJ, Licht I, Ford J, Oeffinger K, Diller L. Screening adult survivors of childhood cancer with the distress thermometer: a comparison with the SCL-90-R. Psycho-oncology. 2007;16(11):1046–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krull KR, Okcu MF, Potter B, Jain N, Dreyer Z, Kamdar K, et al. Screening for neurocognitive impairment in pediatric cancer long-term survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4138–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.8864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ojha RP, Oancea SC, Ness KK, Lanctot JQ, Srivastava DK, Robison LL, et al. Assessment of potential bias from non-participation in a dynamic clinical cohort of long-term childhood cancer survivors: Results from the St. Jude lifetime cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(5):856–64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]