Abstract

Lenalidomide is an effective therapeutic agent for multiple myeloma that exhibits immunomodulatory properties including the activation of T and NK cells. The use of lenalidomide to reverse tumor-mediated immune suppression and amplify myeloma-specific immunity is currently being explored. In the present study, we examined the effect of lenalidomide on T-cell activation and its ability to amplify responses to a dendritic cell-based myeloma vaccine. We demonstrate that exposure to lenalidomide in the context of T-cell expansion with direct ligation of CD3/CD28 complex results in polarization toward a Th1 phenotype characterized by increased IFN-γ, but not IL-10 expression. In vitro exposure to lenalidomide resulted in decreased levels of regulatory T cells and a decrease in T-cell expression of the inhibitory marker, PD-1. Lenalidomide also enhanced T-cell proliferative responses to allogeneic DCs. Most significantly, lenalidomide treatment potentiated responses to the dendritic cell/myeloma fusion vaccine, which were characterized by increased production of inflammatory cytokines and increased cytotoxic lymphocyte-mediated lysis of autologous myeloma targets. These findings indicate that lenalidomide enhances the immunologic milieu in patients with myeloma by promoting T-cell proliferation and suppressing inhibitory factors, and thereby augmenting responses to a myeloma-specific tumor vaccine.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00262-012-1308-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Lenalidomide, Multiple myeloma, Dendritic cell vaccine, PD-1

Introduction

Patients with multiple myeloma (MM) exhibit immunosuppressive features that result in tumor anergy, immune escape, and disease growth. The immunologic environment is characterized by loss of antigen presenting and effector cell function due to tumor-derived soluble factors and increased levels of regulatory T cells (reviewed by Pratt [1]). Another critical factor that promotes tumor tolerance and immune evasion is the PD-1/PDL-1 pathway that inhibits T-cell activation by antigen-presenting cells, resulting in an “exhausted T-cell phenotype” [2]. We have previously demonstrated that PD-1 expression is upregulated on T cells isolated from patients with MM, suggesting that this pathway is of importance in mediating the immunosuppressive state in this patient population [3]. Reversing tumor-mediated immune suppression in myeloma is thus a therapeutic goal that is critical for the development of myeloma-specific immunotherapy.

Lenalidomide is a second-generation thalidomide analog that exhibits potent anti-myeloma activity. Treatment of MM patients with lenalidomide-based regimens results in higher response rates and improved outcomes as compared to those achieved with standard chemotherapeutic regimens [4–7]. Recent studies have shown that lenalidomide maintenance following autologous transplantation is associated with the significant prolongation of time to disease progression [8, 9]. Lenalidomide’s mechanism of action is multifactorial and is thought to relate to its direct anti-tumor activity [10], anti-angiogenetic properties [11], effects on bone marrow microenvironment [12, 13], and immunomodulatory activity.

The precise effect of lenalidomide on immune function has not been fully elucidated but is thought to be due to the enhanced activation of T and NK cells. Lenalidomide induces tyrosine phosphorylation of CD28 and activation of NF-κB in T cells [14] and promotes nuclear translocation of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NF-AT)-2 and activator protein (AP)-1 via activation of the PI3 K/Akt pathway [15]. A recent study has shown that exposure of T cells to lenalidomide also leads to an increase in STAT1 phosphorylation and a decrease in suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) protein 1, ultimately leading to increased IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion [16]. Lenalidomide also enhances NK-mediated antibody-dependent T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity [15, 17] and inhibits the proliferation and suppressor function of regulatory T cells in vitro and in vivo [18, 19]. In addition, lenalidomide may augment the efficacy of the graft versus myeloma effect following allogeneic transplantation through the stimulation of alloreactive lymphocyte [20, 21]. However, the ability of lenalidomide to elicit myeloma-specific immunity or augment the activity of myeloma directed tumor vaccines has not been fully explored.

In this report, we demonstrate that in vitro exposure to lenalidomide induces Th1 polarization in response to antigen-independent stimulation via CD3/CD28 ligation. Consistent with its role in promoting T-cell activation, lenalidomide treatment was associated with decreased levels of regulatory T cells and a decrease in expression of the inhibitory marker, PD-1. Lenalidomide enhanced T-cell proliferation in response to allogeneic dendritic cells (DCs) but did not directly affect DC maturation or activation. Lenalidomide also augmented responses to the myeloma-specific vaccine generated by the fusion of MM cells with DCs.

Methods

Cell source

Patient-derived bone marrow aspirates and peripheral blood samples were obtained from MM patients in accordance with a protocol approved by the institutional review board allowing for harvesting of peripheral blood and tumor cells in patients undergoing procedures for independent diagnostic purposes. Alternatively, cell populations were isolated from leukopak collections obtained from normal donors. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and MM preparations were subjected to ficoll density centrifugation (Histopaque-1077, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), cultured at 37 °C in a humidified 5 % CO2 incubator and maintained in a complete culture media consisting of RPMI 1640 culture media (Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA) supplemented with heat-inactivated 10 % human serum albumin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA).

Reagents

Lenalidomide (Celgene, Summit, NJ, USA) was dissolved in DMSO (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) to obtain a stock concentration of 40 mM that was further diluted at the time of addition to the culture media to achieve the final concentration used in experiments. Human pharmacokinetic studies show that peak lenalidomide levels in plasma after a therapeutic dose of 25 mg are in the range of 1–2 μM and the trough levels 24 h after a 25 mg dose are in the range of 0.1–0.5 μM [22–24]. We performed preliminary experiments with lenalidomide concentration ranging from 0.1 to 10 μM showing no further advantage of increasing the dose above 1 μM, and we decided to use the physiologically relevant concentration of 1 μM in all further experiments. DMSO at the corresponding concentration of 0.0025 % was used as a control.

Generation of T-cell-rich portion of PBMCs and monocyte-derived DCs

PBMCs were plated in tissue culture flasks in complete media and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The T-cell-rich non-adherent fraction was cultured in complete media supplemented with 10 U/mL IL-2 (Roche diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). As described [25], DCs were generated from the adherent PBMC fraction cultured in the presence of 1000 U/mL GM-CSF (Berlex, Wayne/Montville, NJ, USA) and 12.5 ng/mL IL-4 (Cellgenix, Freiburg, Germany) for 5 days and 25 ng/mL TNF-α (Cellgenix, Freiburg, Germany) was added on day 5 for additional 2 days to induce maturation.

DC/MM fusion generation

DC/MM fusions were created as previously described using polyethylene glycol (PEG, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) [25]. Briefly, MM tumor cells and DCs were mixed at ratio of 1:3, centrifuged at low speed, and the resulting cell pellets were re-suspended in warm (37 °C) PEG. After 1–5 min, the PEG was progressively diluted by the slow addition of RPMI 1640 culture media. The cells were then washed and cultured with GM-CSF (500 U/mL) and IL-4 (6.25 ng/mL).

Phenotypical characterization of DCs

To evaluate the effect of lenalidomide on DC maturation, lenalidomide (1 μM) was added on day 2 of the DC maturation culture. On day 7, immunophenotyping of DCs was done by flow cytometry to assess expression of co-stimulatory (HLA-DR, CD80, CD86), and maturation (CD83) markers in each group. DCs were incubated with primary mouse mAbs directed against human HLA-DR, CD11c, CD14, CD80, CD86, and CD83 or matching isotype controls (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), washed, and incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG/IgM (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). Cells were fixed in 2 % paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and analyzed by flow cytometry. All flow cytometric analyses were performed using FACScan (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and cellquest pro software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

T-cell stimulation with allogeneic DCs

The effect of lenalidomide on T-cell proliferation in response to allogeneic antigens was studied using the mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR). In order to clarify whether lenalidomide affects the antigen-presenting cells, effector cells, or both, the experiment was done using 4 different conditions: (A) T cells and allo-DCs were co-cultured in a standard MLR without lenalidomide. (B) 1 μM lenalidomide was added to the co-culture of T cells and allo-DCs. (C) T cells alone were “pretreated” by 1 μM of lenalidomide in culture for 5–7 days, washed, and co-cultured with allo-DCs in a lenalidomide-free media. (D) DCs were matured in media containing 1 μM of lenalidomide for 7 days, harvested, washed, and used to stimulate allogeneic T cells in a lenalidomide-free media. T-cell proliferation was assessed by incorporation of [3H]thymidine (1 μCi/well; 37 kBq; NEN-Du-Pont, Boston, MA, USA) added to each well 18 h before the end of the 7 day culture period. Thereafter, the cells were harvested onto glass fiber filter paper (Wallac, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) using an automated TOMTEC harvester (Mach II), dried, and sealed in BetaPlate sample bag (Wallac, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) with 10 mL of ScintiVerse (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Cell bound radioactivity was counted in a liquid scintillation counter (Wallac; 1205 Betaplate, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Polyclonal T-cell stimulation by direct ligation of the CD3/CD28 complex

Stimulation of T cells with anti-CD3/CD28 was accomplished by coating 24-well non-tissue culture-treated plates (Falcon, Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) with anti-CD3 (clone-UCHT1; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) and anti-CD28 (clone-CD28.2; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) at the concentration of 1 μg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 0.3 mL/well overnight at 4 °C. The plates were washed in 1 × PBS, and T-cell preparations were added at a density of 2x106 cells/well and cultured for 4 days in the presence or absence of lenalidomide (1 μM).

Assessment of T-cell polarization

Expression of inflammatory (IFN-γ) and inhibitory (IL-10) cytokines by T cells was assessed by intracellular flow cytometry. T cells were pulsed with GolgiStop (1 μg/mL; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) for 4–6 h at 37 °C prior to analysis. Cells were next harvested and labeled with murine anti-human TRI-COLOR-conjugated CD4 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, USA) and FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) antibodies. Cells were then permeabilized by incubation in Cytofix/Cytoperm plus™ (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) containing formaldehyde and saponin for 45 min at 4 °C, washed twice in Perm/Wash™ solution (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), and incubated with PE-conjugated IFN-γ (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, USA), IL-10 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), or a matched isotype control antibody for 45 min. Cells were washed in 1 × Perm/Wash™ solution and fixed in 2 % paraformaldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Labeled cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Quantification of regulatory T cells and T-cell subsets expressing PD-1

T cells were labeled with TRI-COLOR-conjugated anti-CD4 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, USA), FITC-conjugated anti-CD8 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), PE-conjugated anti-PD-1 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), and TRI-COLOR-conjugated anti-CD25 (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA, USA). The cells were permeabilized and labeled with intracellular FOXP3 stain (PE anti-human FOXP3 staining set, eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). The relative percentage of regulatory T cells was assessed as the CD4 +/CD25 +/FOXP3 + phenotype.

Antigen-specific T-cell stimulation by DC/MM fusions

T cells were co-cultured with DC/MM fusions at a ratio of 1:10 in a 96-well plate in the presence or absence of 1 μM lenalidomide. After 5–7 days of stimulation, the expression of inflammatory and inhibitory cytokines was assessed by intracellular flow cytometry as described above. In addition, the relative percentage of regulatory T cells and T-cell subsets expressing PD-1 were quantified using flow cytometry as described above.

Assessment of signal transduction pathway phosphorylation by phospho-flow analysis and immunoblotting

T cells were stimulated with DC/MM fusions as described above in the presence and absence of lenalidomide and purified by magnetic bead separation using CD3 microbeads (Miltenyibiotec, Auburn, CA, USA). For Phospho-Flow analysis, stimulated T-cell populations were fixed with 2 % paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and pelleted by centrifugation. Cells were resuspended in 90 % methanol (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), incubated on ice for 30 min, washed, and resuspended in 75 μL Stain Buffer containing Dulbecco’s PBS, 2 % FBS, 0.09 % Sodium Azide (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA). Cells were incubated with 1 μg/mL anti-pSTAT3, anti-pSTAT5 (BD Biosciences), and matched isotype controls conjugated to PE for 30 min. Stained cells were analyzed by multichannel FACs analysis. Alternatively, for immunoblot analysis, cells were lysed as described and soluble proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting [26] with anti-p-STAT5 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Immunoreactivity was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Evaluation of cytolytic capacity against autologous tumor targets

To evaluate the expansion of T cells targeting myeloma cells, T cells were stimulated with autologous DC/MM fusions in the presence or absence of lenalidomide (1 μM) for 7 days and cell-mediated cellular cytotoxicity was quantified using the GranToxiLux cell-based fluorogenic cytotoxicity assay (OncoImmunin, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Autologous myeloma cells were used as target cells. Target cells were incubated in PE labeled Medium T (1 μL of reconstituted TFL2 in PBS at 1:3,000 ratio) at 2 × 106 cells/mL for 45 min at 37 °C, and washed in PBS. T cells stimulated by DC/MM fusions were washed twice in PBS and co-incubated at a 1:5 ratio with labeled target cells in the presence of a fluorogenic granzyme B substrate for 1–2 h at 37 °C. Cells were washed and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Students t test was used for comparison, and values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

Lenalidomide promotes the Th1 phenotype

We examined the effects of lenalidomide on T-cell polarization following ligation of the costimulatory complex with antibodies directed against CD3 and CD28. The addition of lenalidomide to anti-CD3/CD28 stimulated T cells obtained from normal donors resulted in a twofold increase in the percentage of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells expressing IFN-γ as compared to T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 alone (n = 5, p = 0.06 and p = 0.02 for CD4 + and CD8 + , respectively). Exposure to lenalidomide resulted in a similar increase in the percentage of T cells expressing IFN-γ in CD8 + cells derived from patients with multiple myeloma (n = 5, p = 0.01, Fig. 1). In contrast, intracellular production of the Th2 cytokine, IL-10, remained at baseline low levels after exposure to lenalidomide (data not shown). These studies demonstrate that lenalidomide induces polarization of T cells derived from myeloma patients toward the inflammatory Th1 phenotype.

Fig. 1.

Lenalidomide induces T-cell polarization toward a Th1 phenotype in T cells obtained from MM patients. a Proportion of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells expressing intracellular IFN-γ after ligation of the co-stimulatory complex with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies for 4 days in the absence (dark grey) and presence (light grey) of 1 μM of lenalidomide (n = 5, p = 0.01). b Representative plot showing intracellular expression of IFN-γ in CD4 + and CD8 + T cells obtained from MM patient blood sample stimulated for 4 days with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies in the absence and presence of lenalidomide

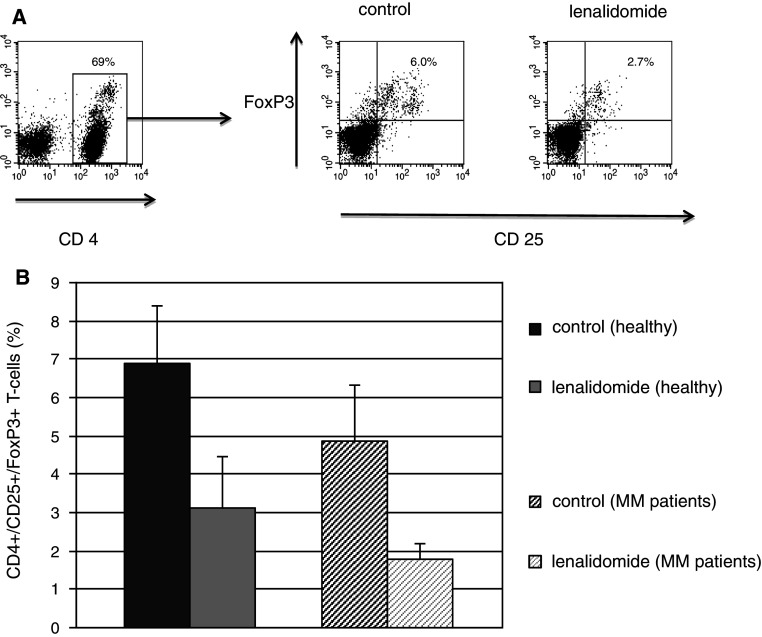

Lenalidomide blunts regulatory T-cell expansion

Regulatory T cells undergo expansion in response to stimuli, such as anti-CD3/CD28, that promote T-cell activation to maintain immunologic equilibrium and protect against auto-immunity. However, exposure to lenalidomide during the period of anti-CD3/CD28-mediated stimulation of T cells from normal donors resulted in a decrease in the percentage of regulatory T cells from 6.88 to 3.13 (n = 8, p = 0.05). Similarly, the percentage of regulatory T cells isolated from patients with MM also decreased in the presence of lenalidomide (1.8 as compared to 4.85, n = 5, p = 0.04, Fig. 2), indicating that lenalidomide attenuates regulatory T-cell expansion.

Fig. 2.

Lenalidomide blunts regulatory T-cell expansion. a Representative plot showing a decrease of the CD25 +/FoxP3 + population in the CD4 + gate after 4 day culture in media containing 1 μM lenalidomide compared with a control media, a MM patient blood sample. b Proportion of regulatory T cells (defined by the CD4 +/CD25 +/FoxP3 + phenotype) when PBMCs were cultured and stimulated by direct ligation of the CD3/CD28 complex in the absence (dark grey) and presence of 1 μM lenalidomide (light grey) for 4 days, samples obtained from healthy controls (n = 8, p = 0.05) and MM patients (n = 5, p = 0.04)

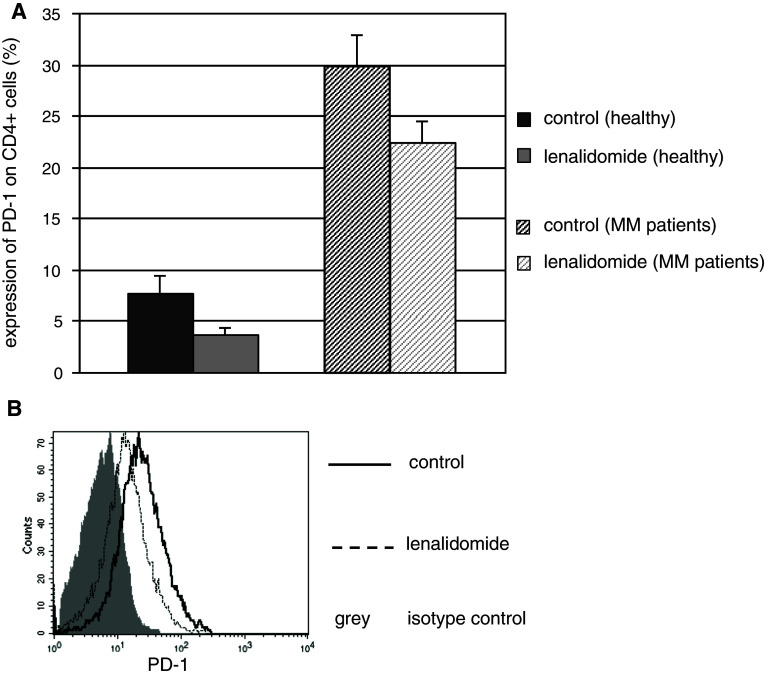

Lenalidomide suppresses T-cell expression of PD-1

The PD-1/PDL-1 pathway is upregulated in the setting of malignancy and chronic infection where it has been shown to promote an “exhausted T-cell phenotype” facilitating tumor tolerance and immunologic escape. In the present studies, PD-1 expression was significantly increased on T cells obtained from MM patients compared to healthy controls (30 % as opposed to 7.6 %, p = 0.001, Fig. 3a). Notably, exposure to lenalidomide decreased PD-1 expression on CD4 + T cells from both healthy volunteers (from 7.62 to 3.75 %, n = 7, p = 0.03) and MM patients (from 29.8 to 22.3 %, n = 5, p = 0.05, Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

PD-1 expression is increased on T cells in patients with MM and is downregulated by lenalidomide. a Mean expression of PD-1 on resting CD4 + T cells in patients with MM and healthy controls after 4 day exposure to 1 μM lenalidomide compared to control media. Lenalidomide (1 μM) decreases PD-1 exposure in samples obtained from healthy controls (n = 7, p = 0.03) and MM patients (n = 5, p = 0.05), as also depicted in the representative histogram (b)

Lenalidomide augments T-cell proliferation in response to stimulation with allogeneic DCs

We next examined the effect of lenalidomide on the in vitro response of T cells to stimulation with allogeneic DCs. T cells were co-cultured with allogeneic DCs in a standard MLR in control media (Supplemental Fig. 1, condition A) and in media with lenalidomide (Supplemental Fig. 1, condition B). DC-mediated stimulation of T cells in the presence of lenalidomide resulted in a twofold increase in proliferation as compared to T cells co-cultured with allogeneic DCs in control media (n = 3, p = 0.015).

To determine whether this increase in proliferation is mediated by lenalidomide effects on T cells or DCs, the populations of T cells and the antigen-presenting DCs, respectively, were preincubated with lenalidomide for 5–7 days prior to their co-culture, which was done in a lenalidomide-free media. Preincubation of T cells with lenalidomide resulted in a twofold increase in T-cell proliferative response to allogeneic DCs (Supplemental Fig. 1, condition C) as compared to control. In contrast, exposure of DCs to lenalidomide during the maturation period had no effect on expression of the costimulatory markers, CD80 and CD86, and the maturation marker, CD83 (data not shown). Consistent with these findings, preincubation of DCs with lenalidomide did not result in increased proliferation of allogeneic T cells (Supplemental Fig. 1 condition D) as compared to control. These data support the conclusion that the lenalidomide-induced increase in T-cell proliferation by allogeneic DC stimulation is mediated through its direct effect on T cells.

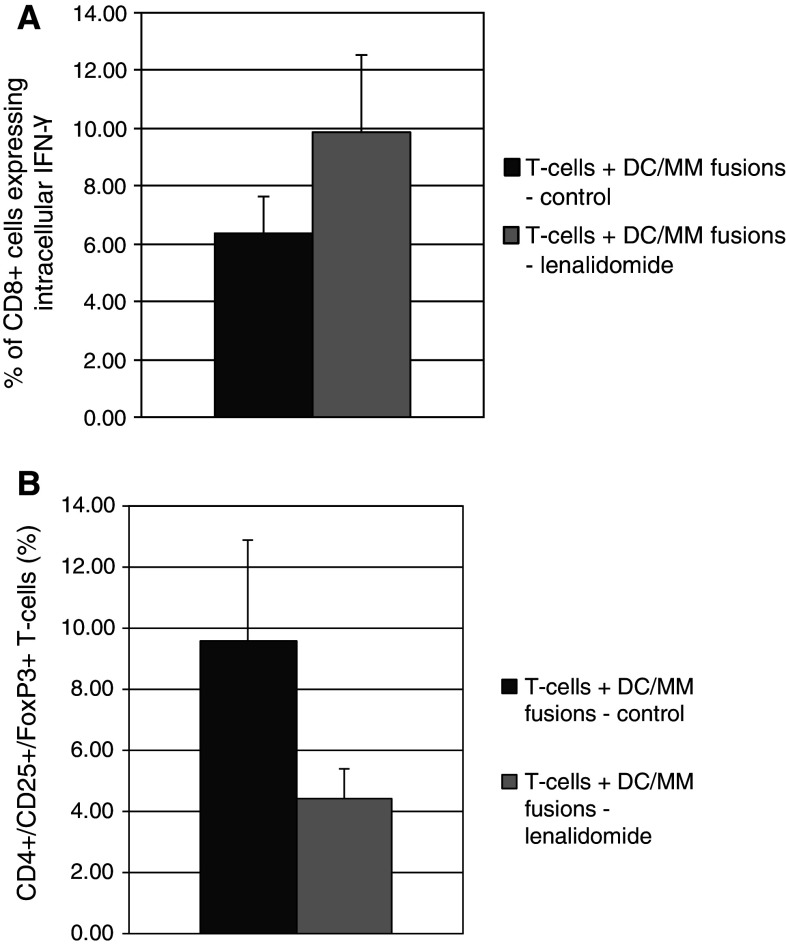

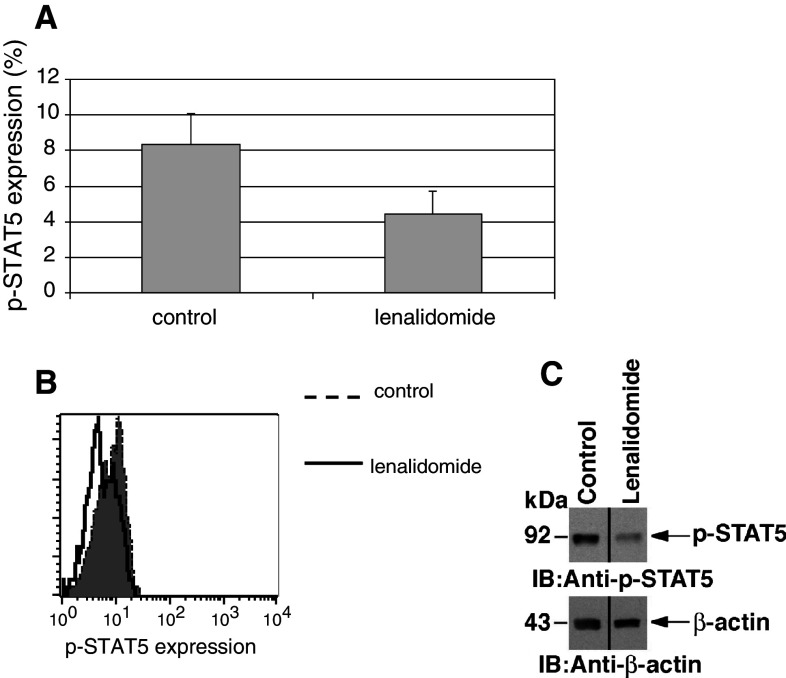

Lenalidomide augments the T-cell response to the DC/MM fusion vaccine in vitro

We subsequently examined the effect of lenalidomide on the capacity of a DC/MM vaccine to induce anti-tumor immune responses in vitro. T cells were stimulated in vitro with DC/MM fusions in the absence and presence of lenalidomide. After 5–7 days of stimulation by the vaccine, the percentage of CD8 + T cells expressing IFN-γ in response to DC/MM fusion stimulation was significantly increased in the presence of lenalidomide (from 6.37 to 9.9 %; n = 7, p = 0.03, Fig. 4a). A concomitant statistically significant decrease in the proportion of regulatory T cells was also observed (4.4 % in the lenalidomide group as opposed to 9.6 % in the control group; n = 3, p = 0.02, Fig. 4b). To elucidate the mechanism responsible for suppression of regulatory T-cell expansion, we examined the effect of lenalidomide exposure on the STAT pathways that are critical for mediating the balance between T-cell activation and inhibition (reviewed by Wei [27]). In particular, activation of STAT5 promotes regulatory T-cell expansion [28–30]. Our results demonstrate that lenalidomide inhibits phosphorylation of STAT5 in T cells stimulated by DC/MM fusions as evidenced by a 50 % decrease in the amount of phosphorylated STAT5 by Phospho-Flow analysis (n = 4, p = 0.04, Fig. 5a,b). The decrease in STAT5 phosphorylation was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 5c). By contrast, exposure to lenalidomide had no apparent effect on levels of activated STAT3 (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Lenalidomide augments the immune response to the DC/MM vaccine. DC/MM fusion vaccine was created as described. Autologous T cells were aliquoted in a 1:10 ratio and stimulated by the DC/MM fusion vaccine for 5–7 days in the absence and presence of 1 μM lenalidomide. (A) Proportion of CD8 + T cells expressing intracellular IFN-γ after DC/MM vaccine stimulation in the absence (dark grey) and presence (light grey) of lenalidomide (n = 7, p = 0.03). (B) Proportion of regulatory T cells as assessed by flow cytometry after DC/MM vaccine stimulation in the absence (dark grey) and presence (light grey) of lenalidomide (n = 3, p = 0.02)

Fig. 5.

Decrease in STAT5 phosphorylation after exposure to lenalidomide. T cells were stimulated by DC/MM vaccine for 5–7 days in the absence and presence of 1 μM lenalidomide, and purified by magnetic bead separation. (a) Proportion of T cells expressing p-STAT5 when stimulated in the absence and presence of 1 μM lenalidomide as assessed using phospshoflow analysis (n = 4, p = 0.04), with a representative histogram (b). Decrease in p-STAT5 was confirmed using immunoblot analysis (c)

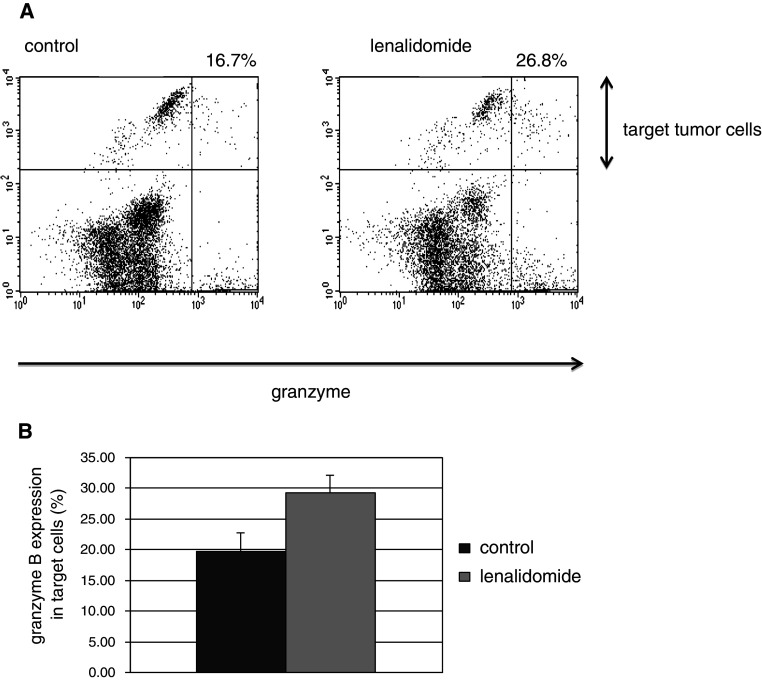

Our results further demonstrate that lenalidomide enhances the vaccine induced cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) response targeting MM cells. As determined by a fluorochrome assay measuring granzyme B release in target cells, CTL-mediated lysis of autologous MM tumor targets was increased by 50 % when T cells were stimulated by DC/MM fusions in the presence of lenalidomide as compared to those cultured with fusions alone (mean 29.2 vs. 19.7 %; n = 3, p = 0.004; Fig. 6a, b). These results indicate that lenalidomide potentiates a targeted T-cell response to the DC/MM vaccine.

Fig. 6.

Myeloma-specific immune response to a DC/MM vaccine is increased by lenalidomide. T cells obtained from the peripheral blood of MM patients were stimulated by an autologous DC/MM vaccine for 7 days in the absence and presence of 1 μM lenalidomide. T cells were subsequently washed free of media, and used to target autologous tumor cells in a cell-based fluorogenic cytotoxicity assay: Tumor targets were labeled by a fluorescent dye projecting in the FL-2 channel. T cells and labeled tumor targets were co-incubated in a 5:1 ration in the presence of a fluorogenic granzyme B substrate. a Cell-mediated cytotoxicity results in the uptake of granzyme B by target cells and is detected by the presence of the fluorogenic granzyme B substrate in the FL-1 channel, as shown in this representative plot. The proportion of tumor cells targeted by autologous CTLs is calculated as the number of cells in the upper right quadrant divided by the sum of upper left and upper right quadrants. b The mean proportion of tumor cells targeted by autologous T cells that were previously stimulated by a DC/MM vaccine in the absence (dark grey) and presence (light grey) of lenalidomide (n = 3, p = 0.004)

Discussion

Patients with MM exhibit immunosuppressive features that compromise their capacity to develop anti-tumor immunity and promote disease growth. Tumor cells induce tolerance by exploiting native immune pathways that are responsible for preventing autoimmunity and maintaining immunologic equilibrium (reviewed by Disis [31].) Critical aspects of tumor-mediated immune suppression include the ineffective presentation of tumor antigens due to the absence of costimulation and inflammatory signals, loss of effector cell function, increased presence of regulatory T cells that blunt T-cell activation, and the upregulation of inhibitory pathways such as PD-1/PDL-1 that promote an “exhausted T-cell phenotype.”

A major area of investigation is the development immunomodulatory strategies to reverse myeloma-mediated immune suppression and promote the development of anti-tumor immunity. Lenalidomide is a potent anti-myeloma agent that exhibits anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory features. Previous studies have demonstrated that lenalidomide suppresses regulatory T-cell function and enhances NK cell function, but its precise impact on the immunologic milieu and the immune-mediated targeting of myeloma remains to be elucidated. A recent paper evaluated in vitro effect of lenalidomide on the T-cell response to dendritic cells pulsed with a single peptide, MART-1. Incubation of T cells with MART-1 loaded DCs in the presence of lenalidomide lead to expansion of MART-1 tetramer +CD8 cells and downregulation of CD45RA, suggesting an enhancement of antigen-specific T-cell response and a more mature T-cell immunophenotype [32]. In our study, we sought to better define the effect of lenalidomide on the immune inhibitory mechanisms, the interaction between DCs and T cells, and the ability of a whole cell-based tumor vaccine to stimulate the expansion of tumor reactive lymphocytes with cytolytic capacity against autologous primary tumor cells.

Our results demonstrate that lenalidomide polarizes T-cell responses toward a Th1 phenotype. Ligation of the costimulatory complex with anti-CD3/CD28 in the presence of lenalidomide resulted in an increase in the percentage of T cells expressing IFN-γ but not IL-10. In addition, lenalidomide prevented the expansion of regulatory T cells in response to both antigen-independent and antigenic stimulation. In concert with these findings, we demonstrate that exposure to lenalidomide is associated with decreased expression of activated STAT5, a critical pathway supporting the development of regulatory T cells. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown that exposure of PBMCs from healthy volunteers to lenalidomide in vitro leads to a decrease in CD4 +/CD25high/FOXP3 + regulatory cells [18]. Reports outlining the in vivo effect of lenalidomide on regulatory T cells are, however, conflicting. Some studies showed that, in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, treatment with lenalidomide leads to a decrease in regulatory T cells [19, 33]. In contrast, lenalidomide therapy in patients who had a relapse of their MM after an allogeneic stem cell transplant lead to an increase in CD4 + Foxp3 + T cells [34].

Our studies have investigated the effect of lenalidomide on DC-mediated stimulation of alloreactive T cells. We found that lenalidomide increases the proliferation of alloreactive lymphocytes in response to DC-mediated stimulation. These findings are consistent with the observation that lenalidomide may induce disease response in patients experiencing relapse following allogeneic transplantation. This response to lenalidomide may be due to enhanced alloreactive T-cell and NK-cell activity mediating a graft versus disease effect. Similarly, lenalidomide may induce graft versus host disease [35]. Of note, the effect of lenalidomide was restricted to the T-cell compartment, as preincubation of DCs during the period of maturation did not increase expression of costimulatory or maturation markers and did not result in increased T-cell proliferation. In contrast, preincubation of the T-cell compartment with lenalidomide preserved the increased proliferative response. This has important clinical implications, as one may expect increased T-cell responsiveness to antigenic stimuli in a patient recently treated with lenalidomide even in the absence of lenalidomide exposure at the time of antigen presentation.

PD-1 is a member of the B7 receptor family and is expressed by immune effector cells including T cells, B cells, and NK cells. Ligation of this receptor results in T-cell inactivation and apoptosis. The PD-1/PDL-1 pathway is being evaluated as a central mechanism by which tumors escape host immunity [36–38]. Tumor expression of PDL-1 has been demonstrated in several malignancies, and PDL-1/PD-1 interactions are thought to suppress T-cell capacity to secrete stimulatory cytokines and thus lead to peripheral tolerance [2]. In addition, tumor expression of PDL-1 has been shown to directly inhibit T-cell-mediated lysis by the inactivation of tumor reactive CTLs [39]. Recent work confirmed high PDL-1 expression on MM cell lines and on plasma cells obtained from bone marrows of MM patients. Interestingly, in vitro treatment with lenalidomide lead to a significant decrease of PDL-1 expression on these malignant plasma cells [40]. Our results demonstrate a high percentage of circulating T cells expressing PD-1 in patients with myeloma. To our knowledge, this is the first report documenting that PD-1 expression on T cells is decreased after exposure to lenalidomide, suggesting that modulation of the PD-1/PDL-1 pathway may be a critical factor in mediating the anti-tumor immunomodulatory properties of this agent.

Finally, we examined the effect of lenalidomide on the response to a MM tumor vaccine. Our group has developed a cancer vaccine involving the fusion of tumor cells with autologous DCs such that a broad array of tumor antigens are presented in the context of DC-mediated costimulation. DC/tumor fusions have been shown to eradicate metastatic disease in animal models and induce CD4 and CD8-mediated anti-tumor immunity in preclinical human studies [41–43]. In a clinical study, we have demonstrated that vaccination with DC/MM fusions results in the expansion of tumor reactive lymphocytes and disease stabilization in a majority of patients with advanced myeloma [44]. Of note, immunosuppressive features prevalent in MM patients including the increased presence of regulatory T cells, activation of the PD-1/PDL-1 pathway, and polarization of the native T-cell populations toward an inhibitory phenotype likely interfere with vaccine efficacy. In addition, tumor vaccines further induce the expansion of both activated and inhibitory cells, the latter of which blunt vaccine response [45]. In the present study, we demonstrate that stimulation with DC/MM fusions in the presence of lenalidomide results in enhanced expansion of T cells expressing IFN-γ, decreased levels of regulatory T cells, and, most significantly, an increased capacity of vaccine stimulated T cells to lyse autologous MM cells. While our experiments did not examine the effects of T-cell exposure to lenalidomide in vitro beyond 7 days, the in vivo effect of lenalidomide on T cells subsets after a 21 days on/7 days off schedule was previously studied and demonstrated a preserved number of CD8 + and CD56 + cells and a mild increase in CD4 + cells at the conclusion of the first cycle of therapy [23]. Taken together with our in vitro data, we suggest the DC/tumor vaccine administration should be both preceded and followed by lenalidomide therapy for 7–21 days in order to promote a more effective anti-tumor response.

In summary, we have demonstrated that exposure to lenalidomide results in T-cell polarization toward an activated phenotype, decreased presence of regulatory T cells, and downregulation of the PD-1/PDL-1 pathway that is critical for tumor-mediated tolerance. In concert with these results, lenalidomide augments the efficacy of a myeloma tumor vaccine. These findings suggest that lenalidomide may create an ideal platform for myeloma-specific immunotherapy by enhancing immune function and potentially acting synergistically with approaches to induce myeloma-specific immunity. A clinical trial examining the potential synergy effect of lenalidomide and DC/MM fusions on the development of anti-myeloma immunity and disease response is currently being planned.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research funding from Celgene to J.R.

Conflict of interest

J.R. has received research funding from Celgene. K.C.A. is on the advisory board of Celgene. The remaining authors declare no competing conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pratt G, Goodyear O, Moss P. Immunodeficiency and immunotherapy in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:563–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, et al. Tumor-associated B7–H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenblatt J, Glotzbecker B, Mills H, et al. PD-1 blockade by CT-011, anti-PD-1 antibody, enhances ex vivo T-cell responses to autologous dendritic cell/myeloma fusion vaccine. J Immunother. 2011;34:409–418. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31821ca6ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2123–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2133–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gay F, Hayman SR, Lacy MQ, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone versus thalidomide plus dexamethasone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a comparative analysis of 411 patients. Blood. 2010;115:1343–1350. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zonder JA, Crowley J, Hussein MA, et al. Lenalidomide and high-dose dexamethasone compared with dexamethasone as initial therapy for multiple myeloma: a randomized Southwest oncology group trial (S0232) Blood. 2010;116:5838–5841. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attal M, Cances Lauwers V, Marit G, et al. Maintenance treatment with lenalidomide after transplantation for MYELOMA: final analysis of the IFM 2005–02 [abstract 310] Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2010;116:310. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy PL, Owzar K, Anderson KC, et al. Phase III intergroup study of lenalidomide versus placebo maintenance therapy following single autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (AHSCT) for multiple myeloma: CALGB 100104 [abstract 37] Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2010;116:37. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Shima Y, et al. Thalidomide and its analogs overcome drug resistance of human multiple myeloma cells to conventional therapy. Blood. 2000;96:2943–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J. Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4082–4085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Breitkreutz I, Raab MS, Vallet S, et al. Lenalidomide inhibits osteoclastogenesis, survival factors and bone-remodeling markers in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:1925–1932. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geitz H, Handt S, Zwingenberger K. Thalidomide selectively modulates the density of cell surface molecules involved in the adhesion cascade. Immunopharmacology. 1996;31:213–221. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00050-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeBlanc R, Hideshima T, Catley LP, et al. Immunomodulatory drug costimulates T cells via the B7-CD28 pathway. Blood. 2004;103:1787–1790. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi T, Hideshima T, Akiyama M, et al. Molecular mechanisms whereby immunomodulatory drugs activate natural killer cells: clinical application. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Görgün G, Calabrese E, Soydan E, et al. Immunomodulatory effects of lenalidomide and pomalidomide on interaction of tumor and bone marrow accessory cells in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116:3227–3237. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies FE, Raje N, Hideshima T, et al. Thalidomide and immunomodulatory derivatives augment natural killer cell cytotoxicity in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2001;98:210–216. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galustian C, Meyer B, Labarthe MC, et al. The anti-cancer agents lenalidomide and pomalidomide inhibit the proliferation and function of T regulatory cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:1033–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0620-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Idler I, Giannopoulos K, Zenz T, et al. Lenalidomide treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients reduces regulatory T cells and induces Th17 T helper cells. Br J Haematol. 2010;148:948–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lioznov M, El-Cheikh J, Jr, Hoffmann F, et al. Lenalidomide as salvage therapy after allo-SCT for multiple myeloma is effective and leads to an increase of activated NK (NKp44(+)) and T (HLA-DR(+)) cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:349–353. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spina F, Montefusco V, Crippa C, et al. Lenalidomide can induce long-term responses in patients with multiple myeloma relapsing after multiple chemotherapy lines, in particular after allogeneic transplant. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2011;52:1262–1270. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.564695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tohnya TM, Hwang K, Lepper ER, et al. Determination of CC-5013, an analogue of thalidomide, in human plasma by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr, B: Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;811:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3458–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blum W, Klisovic RB, Becker H, et al. Dose escalation of lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory acute leukemias. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4919–4925. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasir B, Borges V, Wu Z, et al. Fusion of dendritic cells with multiple myeloma cells results in maturation and enhanced antigen presentation. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:687–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin L, Li Y, Ren J, Kuwahara H, Kufe D. Human MUC1 carcinoma antigen regulates intracellular oxidant levels and the apoptotic response to oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35458–35464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei L, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. New insights into the roles of Stat5a/b and Stat3 in T cell development and differentiation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao Z, Kanno Y, Kerenyi M, et al. Nonredundant roles for Stat5a/b in directly regulating Foxp3. Blood. 2007;109:4368–4375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-055756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen AC, Nadeau KC, Tu W, et al. Cutting edge: decreased accumulation and regulatory function of CD4 + CD25(high) T cells in human STAT5b deficiency. J Immunol. 2006;177:2770–2774. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murawski MR, Litherland SA, Clare-Salzler MJ, Davoodi-Semiromi A. Upregulation of foxp3 expression in mouse and human Treg is IL-2/STAT5 dependent: implications for the NOD STAT5B mutation in diabetes pathogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1079:198–204. doi: 10.1196/annals.1375.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Disis ML. Immune regulation of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4531–4538. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neuber B, Herth I, Tolliver C, et al. Lenalidomide enhances antigen-specific activity and decreases CD45RA expression of T-cells from patients with multiple myeloma. J Immunol. 2011;187:1047–1056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee BN, Gao H, Cohen EN, et al. Treatment with lenalidomide modulates T-cell immunophenotype and cytokine production in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2011;117:3999–4008. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minnema MC, van der Veer MS, Aarts T, Emmelot M, Mutis T, Lokhorst HM. Lenalidomide alone or in combination with dexamethasone is highly effective in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma following allogeneic stem cell transplantation and increases the frequency of CD4 + Foxp3 + T-cells. Leukemia. 2009;23:605–607. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kneppers E, van der Holt B, Kersten MJ, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance following non-myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma is not feasible: results of the HOVON 76 trial. Blood. 2011;118:2413–2419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konishi J, Yamazaki K, Azuma M, Kinoshita I, Dosaka-Akita H, Nishimura M. B7–H1 expression on non-small cell lung cancer cells and its relationship with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and their PD-1 expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5094–5100. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang L, Gajewski TF, Kline J. PD-1/PD-L1 interactions inhibit antitumor immune responses in a murine acute myeloid leukemia model. Blood. 2009;114:1545–1552. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-206672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mumprecht S, Schürch C, Schwaller J, Solenthaler M, Ochsenbein AF. Programmed death 1 signaling on chronic myeloid leukemia-specific T cells results in T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Blood. 2009;114:1528–1536. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwai Y, Ishida M, Tanaka Y, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Minato N. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12293–12297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192461099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benson DM, Jr, Bakan CE, Mishra A, et al. The PD-1/PD-L1 axis modulates the natural killer cell versus multiple myeloma effect: a therapeutic target for CT-011, a novel, monoclonal anti-PD-1 antibody. Blood. 2010;116:2286–2294. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-271874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gong J, Chen D, Kashiwaba M, Kufe D. Induction of antitumor activity by immunization with fusions of dendritic and carcinoma cells. Nat Med. 1997;3:558–561. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gong J, Nikrui N, Chen D, et al. Fusions of human ovarian carcinoma cells with autologous or allogeneic dendritic cells induce antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2000;165:1705–1711. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parkhurst MR, DePan C, Riley JP, Rosenberg SA, Shu S. Hybrids of dendritic cells and tumor cells generated by electrofusion simultaneously present immunodominant epitopes from multiple human tumor-associated antigens in the context of MHC class I and class II molecules. J Immunol. 2003;170:5317–5325. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenblatt J, Vasir B, Uhl L, et al. Vaccination with dendritic cell/tumor fusion cells results in cellular and humoral antitumor immune responses in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;117:393–402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vasir B, Wu Z, Crawford K, et al. Fusions of dendritic cells with breast carcinoma stimulate the expansion of regulatory T cells while concomitant exposure to IL-12, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides, and anti-CD3/CD28 promotes the expansion of activated tumor reactive cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:808–821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.