Abstract

Objective:

We sought to determine the range and extent of neurologic complications due to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 infection (pH1N1′09) in children hospitalized with influenza.

Methods:

Active hospital-based surveillance in 6 Australian tertiary pediatric referral centers between June 1 and September 30, 2009, for children aged <15 years with laboratory-confirmed pH1N1′09.

Results:

A total of 506 children with pH1N1′09 were hospitalized, of whom 49 (9.7%) had neurologic complications; median age 4.8 years (range 0.5–12.6 years) compared with 3.7 years (0.01–14.9 years) in those without complications. Approximately one-half (55.1%) of the children with neurologic complications had preexisting medical conditions, and 42.8% had preexisting neurologic conditions. On presentation, only 36.7% had the triad of cough, fever, and coryza/runny nose, whereas 38.7% had only 1 or no respiratory symptoms. Seizure was the most common neurologic complication (7.5%). Others included encephalitis/encephalopathy (1.4%), confusion/disorientation (1.0%), loss of consciousness (1.0%), and paralysis/Guillain-Barré syndrome (0.4%). A total of 30.6% needed intensive care unit (ICU) admission, 24.5% required mechanical ventilation, and 2 (4.1%) died. The mean length of stay in hospital was 6.5 days (median 3 days) and mean ICU stay was 4.4 days (median 1.5 days).

Conclusions:

Neurologic complications are relatively common among children admitted with influenza, and can be life-threatening. The lack of specific treatment for influenza-related neurologic complications underlines the importance of early diagnosis, use of antivirals, and universal influenza vaccination in children. Clinicians should consider influenza in children with neurologic symptoms even with a paucity of respiratory symptoms.

Influenza is known to be associated with various neurologic complications including Reye syndrome, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), transverse myelitis, and seizures.1 Influenza-related encephalopathy has also been reported, mainly in pediatric populations, and may be fatal.2 Since the WHO declared the first influenza pandemic of the 21st century in June 2009, there have been almost 18,449 deaths reported, although this is, without doubt, a gross underestimate.3

Historically, pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection has been associated with heightened neurologic complications and the 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic may have been associated with encephalitis lethargica (EL), an atypical form of encephalitis.4 Research on neurologic complications of 2009 pandemic influenza is important in order to support better diagnosis and treatment, advocate for prevention, and also to determine the degree of clinical similarity with the 1918 and 1976 H1N1 influenza viruses.5 So far there have been few studies (mostly case reports and small series) on the neurologic complications associated with the 2009 pandemic influenza and comprehensive epidemiologic data on the neurologic complications of the 2009 pandemic influenza are lacking.

In this study we present prospectively collected surveillance data on the neurologic complications of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 from 6 major pediatric hospitals across Australia. The purpose of our study was to determine epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, including outcomes of neurologic complications, due to pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 infection in children. We also compare this with published data on neurologic complications of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009.

METHODS

This study was part of the Pediatric Active Enhanced Disease Surveillance (PAEDS) system, a collaborative project between the Australian Pediatric Surveillance Unit (APSU) and the National Centre for Immunization Research and Surveillance (NCIRS) that is funded by the Federal Department of Health and Ageing. It involved 4 tertiary pediatric referral centers in Australia: the Children's Hospital at Westmead (CHW), Sydney, Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne (RCH), Women's and Children's Hospital Adelaide (WCH), and Princes Margaret Hospital Perth (PMH).

In 2009, funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia enabled the study of influenza admissions in the 4 PAEDS hospitals and additional funding from NSW Health supported PAEDS surveillance for pandemic influenza in 2 additional children's hospitals in NSW (Sydney Children's Hospital [SCH] and John Hunter Children's Hospital [JHCH]).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent.

Surveillance in the 3 hospitals in NSW began immediately under provisions of the Health Records and Information Privacy Act 2002 (New South Wales State Government).6

Subsequently, ethics approval for this study was obtained from relevant Human Research Ethics Committees in each center. Informed consent was obtained from parents/carers of the participants prior to information being collected in each participating hospital.

Participants.

All children aged <15 years who were admitted to the participating hospitals with laboratory-confirmed influenza between June 1, 2009, and September 30, 2009, were included. The PAEDS database included age, gender, medical and vaccination history, clinical presentation, diagnostic test results, treatment, clinical course, and outcome.

Clinical definition of neurologic complications.

Neurologic complications were defined as symptoms or signs associated with laboratory-confirmed pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 infection that affected the central or peripheral nervous system including seizures, encephalopathy, encephalitis, or any focal neurologic symptom. Seizures were classified according to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification.7 A diagnosis of encephalitis was made either clinically or pathologically (or both) as per standard definitions.8 Encephalopathy was defined as altered level of consciousness for more than 24 hours, including lethargy, irritability, or change in personality and behavior.9 Significant confusion or disorientation that did not fulfill criteria for encephalopathy was reported separately. Likewise, “loss of consciousness” that did not fulfill criteria for encephalopathy and was not associated with a seizure was reported separately.

Laboratory diagnosis of influenza.

Children admitted to participating hospitals with signs and symptoms of influenza routinely had either a nasopharyngeal aspirate or combined nose and throat swab for influenza testing (immunofluorescence, culture, or PCR). Many also had a rapid antigen test for influenza A and B as part of their routine care. In 2009, specimens positive for influenza A were referred for virologic characterization to one of the following: National Influenza Laboratory at Westmead Hospital, Sydney; the Hunter Area Pathology Service (HAPS); South Eastern Area Laboratory Service (SEALS); Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory (VIDRL); South Australia Pathology; or PathWest Laboratory Medicine Western Australia.

Literature review.

We conducted a systematic search to identify the published literature on pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 neurologic complications. Searches were undertaken in Ovid Medline, Ovid EMBASE, and PubMed in April 2011. Searches were entry-date limited to include items from April 1, 2009, to April 30, 2011. Searches were limited to humans only. Only studies reporting primary data on the laboratory confirmed pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 and its neurologic complications were included.

Statistical analysis.

Data analysis was done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics 19 Inc., Somers, NY). Comparison was made between groups using the χ2 test (with Yeats correction) or Fisher exact test where appropriate. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality was performed and when data were normally distributed the mean differences between groups were calculated using the independent-sample t test. The relative risk and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were also calculated. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

In total, 506 children with laboratory-confirmed pandemic influenza A (H1N1) were admitted to the participating hospitals during the 2009 southern hemisphere winter. Investigation on admission showed 204 (40.3%) were rapid antigen test positive, 20 (3.9%) were direct immunofluorescence positive, 422 (83.4%) were PCR positive, and 12 (2.4%) were culture positive for influenza. Subsequently, 433 unsubtyped specimens were further subtyped and confirmed by the state reference laboratories.

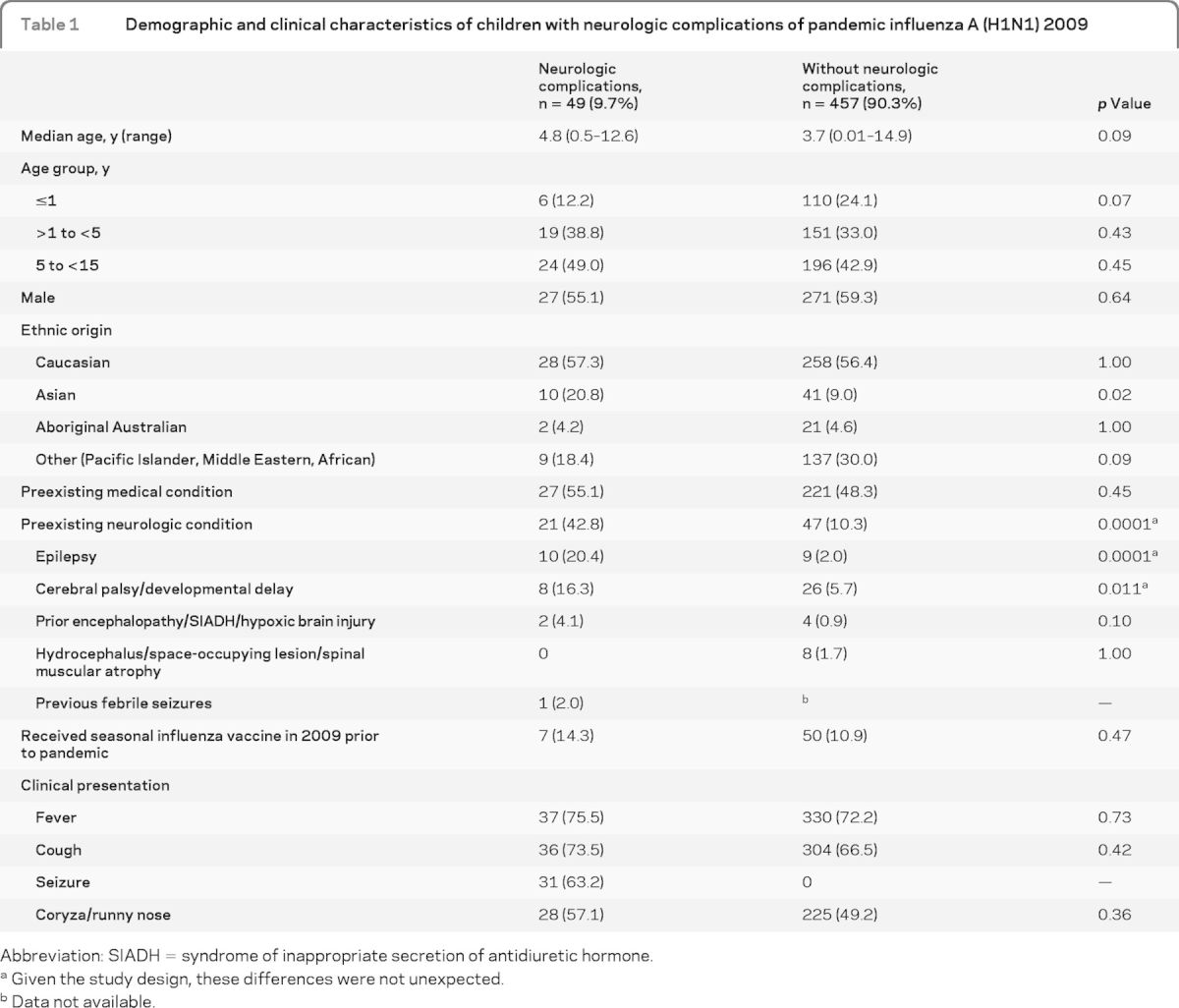

Among these, 49 (9.7%) either presented with neurologic symptoms or developed neurologic complications shortly after admission. Twenty-seven (55.1%) were male. The median age was 4.8 years (range 0.5–12.6 years). Almost half (22, 44.9%) had no prior medical conditions, and of the remainder 21 (42.8%) had preexisting neurologic conditions (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of children with neurologic complications of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009

Abbreviation: SIADH = syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone.

Given the study design, these differences were not unexpected.

Data not available.

Clinical presentation of children with neurologic complications.

Among children with neurologic complications, the most common presenting symptoms were fever (75.5%), cough (73.5%), seizure (63.2%), and coryza/runny nose (57.1%). Only 36.7% had the triad of cough, fever, and coryza/runny nose considered as influenza-like illness (ILI) on presentation, whereas 61.3% had 2 or more respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough, runny nose/coryza, sore throat, and dyspnea) and 38.7% had 1 or less (26.5% 1 and 12.2% none) respiratory symptoms. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the children with or without neurologic complications are presented in table 1.

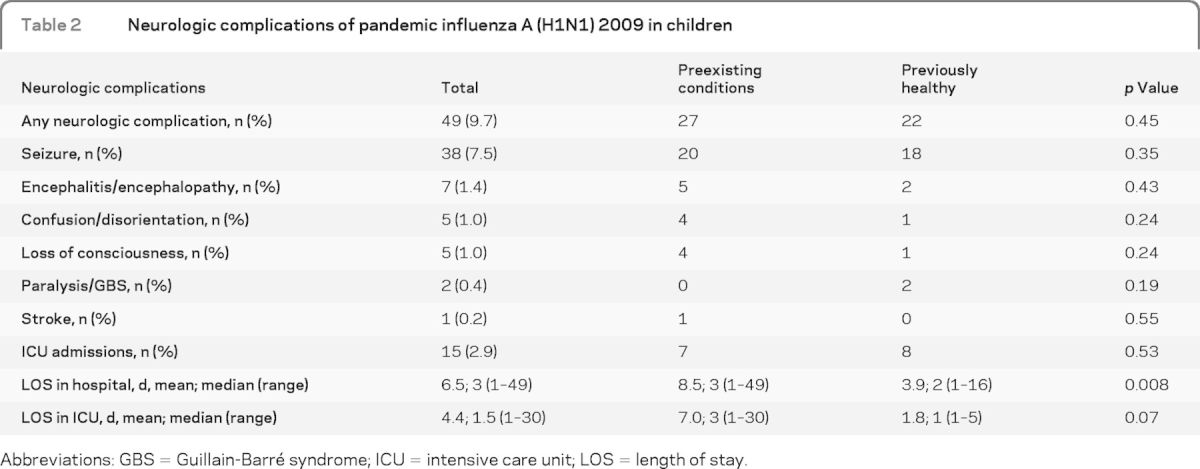

Two-thirds of children with neurologic complications (n = 31, 63.2%) presented with seizure and another 7 (14.3%) developed seizure following admission. Of those who had seizure (n = 38), 23 had fever-associated seizure (predominantly generalized febrile convulsion, n = 16) and 15 had afebrile seizure (12 with afebrile generalized tonic clonic seizure and 3 with afebrile focal seizure). Other neurologic complications included encephalitis/encephalopathy, confusion/disorientation, loss of consciousness, paralysis/GBS, and stroke (table 2).

Table 2.

Neurologic complications of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 in children

Abbreviations: GBS = Guillain-Barré syndrome; ICU = intensive care unit; LOS = length of stay.

Seven children (14.3%) with neurologic complications developed encephalitis/encephalopathy; 5 of them had preexisting health conditions. Of the 2 patients who were previously well, 1 developed pneumonia with empyema and had an asystolic arrest secondary to tension pneumothorax but survived with hypoxic encephalopathy. Another presented with a focal seizure and later developed generalized seizures and encephalopathy. Five (71.4%) of the 7 encephalitis/encephalopathy cases needed intensive care unit (ICU) admission, 1 of whom died (14.3%). All except 1 were aged at least 5 years. Five children with encephalitis/encephalopathy had a lumbar puncture. Influenza virus was not isolated from any sample. One had low CSF protein (0.13 g/L) and the rest did not have any CSF abnormalities. Clinical details of those children are given in table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org.

Clinical course, treatment, and outcome.

The median interval between onset of influenza symptoms (whether ILI or neurologic) and presentation to hospital was 1 day. Almost one-third (15 of 49) of children with neurologic complications needed ICU admission, the majority of which required mechanical ventilation (12 of 15) and 2 (4.1%) died. The mean length of stay (LOS) in hospital was 6.5 days (median 3 days, range 1–49 days) and mean LOS in ICU was 4.4 days (median 1.5 days, range 1–30 days). Four children (8.1%) had nosocomial influenza infection (initial hospital admission for another reason) and later developed neurologic complications.

We have calculated the odds of having neurologic complications among those with preexisting neurologic conditions admitted with influenza compared to the odds of having neurologic complications among those without preexisting neurologic conditions and admitted with influenza. Children with underlying neurologic conditions were 6.5 times more likely to have had neurologic complications from pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 (95% CI 3.4–12.4, p = 0.0001). We have also compared neurologic complications in children with and without preexisting health conditions (table 2). Mean LOS in hospital was shorter in those without preexisting health conditions (p = 0.008). Mean length of intensive care treatment also tended to be shorter in this group (p = 0.07). There were no differences between the 2 groups in types of neurologic complications, but the numbers were too small to make reliable comparisons for each complication.

About three-fifths (61.2%) of the children with neurologic complications were treated with oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu, Roche Products Pty Ltd., Dee Why, NSW, Australia) during admission. There was no relationship between use of oseltamivir phosphate and development of seizures (RR 1, 95% CI 0.5–1.8, p = 0.65), any neurologic complications (p = 0.62), or death (p = 0.51) but numbers were small. Just over half of the children (55.1%) with neurologic complications were treated with antibiotics and 16.3% had laboratory proven bacterial coinfection. Two children died from neurologic complications of pandemic influenza; both had preexisting health conditions.

Literature review of neurologic complications of 2009 pandemic influenza.

We identified 23 published articles presenting original data on 87 cases with 2009 pandemic influenza neurologic complications in children from 12 countries (table e-2).10–32 Unlike our series, most reports were focused only on more severe complications such as encephalitis. The median age of these published cases was 7 years (range 0.25–17 years), with 61.6% male. The most common neurologic complications identified were seizure (30, 34.5%), encephalopathy (25, 28.7%), encephalitis (9, 10.3%), seizure with encephalopathy (8, 9.2%), and acute necrotizing encephalitis (5, 5.7%). We were able to calculate the proportion of neurologic complications in children hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed pandemic influenza in 2009 from 3 studies, 2 in the United States (5.9% and 7.5%) and 1 in the United Kingdom (6.0%).15,19,29 The proportion of encephalopathy in children hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed pandemic influenza was 1.7% in another study.12 The presenting symptoms, neurologic complications, CSF and neuroimaging findings, treatment, and outcome of the 87 children are summarized in table e-2.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the largest prospective cohorts (n = 49) of pediatric neurologic complications associated with pandemic influenza to be presented in a single study generated from a large-scale collaboration between researchers from 6 major pediatric hospitals in 4 different states in Australia.

In our study, we found that neurologic complications (9.7%) were quite frequently reported among children hospitalized with 2009 pandemic influenza. A retrospective cohort study from the United States found that 8.5% of laboratory-confirmed seasonal influenza hospitalized cases had neurologic complications.1 Another recent retrospective study comparing seasonal and pandemic influenza found 5.9% of 303 laboratory-confirmed hospitalized pandemic influenza cases had neurologic complications compared with 6.8% in seasonal influenza cases. However, the authors stated that compared to seasonal influenza, patients with pandemic 2009 influenza were more likely to have encephalopathy, focal neurologic findings, aphasia, and abnormal electroencephalographic findings.15 Another study from Australia in 2007 (of influenza hospitalization in one of our surveillance hospitals) found 1.6% (2 of 122) of hospitalized children with laboratory-confirmed seasonal influenza had encephalitis.33 Our findings, from influenza surveillance and literature review, suggest that the proportion of neurologic complications associated with the 2009 pandemic influenza admissions is comparable to that from published studies of seasonal influenza complications. They also highlight that both seasonal and pandemic influenza are associated with a significant burden of neurologic complications.

Half the children who developed neurologic complications were younger than 5 years and more than half had preexisting medical conditions. There were 2 fatal cases (4.1%) in this study, both with preexisting health conditions. Our observations are consistent with the previous finding from the United States that children with chronic medical conditions (mostly neurodevelopmental conditions) are at increased risk of severe complications of influenza and death.34,35 Moreover, our study shows that children admitted with influenza to hospital who had underlying neurologic conditions are particularly more likely to have neurologic complications from influenza. Through our literature review, we have identified another 7 fatal cases from neurologic complications of pandemic influenza. Encephalitis/encephalopathy was also a relatively common complication of pandemic influenza. Of the 7 encephalitis/encephalopathy cases in our study, 1 died. However, among the survivors all but 1 (i.e., 5 of 6) appeared to recover without obvious sequelae. The long-term outcome of this group is poorly understood and it is important to follow up survivors of neurologic complications from influenza.

In our study, the diagnosis of influenza was not considered until late in some children presenting with neurologic complications (e.g., stroke), probably because respiratory symptoms were atypical or absent. Over 60% did not have the triad of cough, coryza/runny nose, and fever and 12.2% had no respiratory symptoms. It is important that clinicians consider the diagnosis of influenza in children presenting with neurologic symptoms during seasonal epidemics or pandemics of influenza.

An apparent disproportionately high number of children with neurologic complications during the 2009 pandemic were from ethnic minorities (table 1). Our finding is also consistent with the findings from the United Kingdom and United States that ethnic minority groups were disproportionately affected by severe illness.36 In our study, only 14.8% of children with preexisting health conditions had received seasonal influenza vaccine in 2009. This low influenza vaccine uptake among high-risk groups occurred even though vaccination is recommended and government funded in Australia for those with predisposing medical conditions. Despite widespread fear early in the 2009 pandemic, when pandemic vaccine became available, its uptake was low in Australian children (aged <15 years); by February 2010 only 6.8%.37 There is no specific treatment for influenza neurologic complications. Our data inform a better understanding of the clinical and epidemiologic characteristics of neurologic complications of influenza in children, and add to the evidence to support universal influenza vaccination of children.

There has been some recent concern regarding the use of oseltamivir phosphate and neurologic side effects in children.38 In our cohort 61.2% of the children were treated with oseltamivir phosphate after admission. However, within the constraints of small numbers, there was no relationship between use of oseltamivir phosphate and development of seizures (p = 0.65) or any neurologic complications (p = 0.62) or death (p = 0.51). The 1976 H1N1 influenza vaccination campaign was terminated because of a suspected neurologic complication (GBS) associated with the influenza vaccine.39 Interestingly, in our cohort we found 2 previously healthy children who developed paralysis/GBS as a complication of pandemic influenza. All forms of GBS are probably due to an immune response to foreign antigens and in this case probably to the highly immunogenic pandemic virus infection. Recent pandemic (H1N1) 2009 vaccine studies have shown that the 2009 hemagglutinin antigen is so immunogenic that even a single and small dose of unadjuvanted vaccine is sufficient to produce an impressive immune response.40 The pathophysiology of influenza-associated encephalopathy is poorly understood and may involve viral invasion of the CNS, proinflammatory cytokines, metabolic disorders, or genetic susceptibility. In our study, absence of CSF pleocytosis and detectable virus by PCR/culture in the CSF supports an immune-mediated or autoimmune mechanism of influenza-associated encephalopathy, as opposed to direct viral invasion of the CNS.

Our study has some limitations. We have only included admissions to major children's hospitals and not to district general hospitals and thus severe neurologic complications may well have been over-represented. We have only reported laboratory-confirmed cases of pandemic influenza. Later in the pandemic some of the surveillance hospitals did not do routine influenza diagnostic tests due to the overwhelming workload associated with the unprecedented influx of admissions, and thus the number of reported cases was possibly lower than the actual number for those hospitals. We have not performed detailed follow-up of surviving patients to detect potential long-term sequelae.

Our study suggests that neurologic complications of influenza are common and can be potentially life-threatening. Children with preexisting conditions as well as healthy children are at risk of influenza neurologic complications. The rate of influenza vaccination, even among those with high-risk conditions, is very low in children in this study. The specific treatment for influenza-related neurologic complications is uncertain, underlining the importance of early diagnosis, use of antivirals, and the potential for universal influenza vaccination in children. The burden and long-term outcome of neurologic complications associated with influenza need further attention.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the members of SWINet: Margaret Bruce, Kerry Chant (Chief Medical Officer, NSW Health), Dominic Dwyer, Mark Ferson, David Isaacs, Alison Kesson, David Lester-Smith, Jeremy McAnulty, Peter McIntyre, Elizabeth Notaras, Vikki Sheppheard, Nicholas Wood, Leanne Vidler, Melissa Irwin. PAEDS Investigators: Ms. Nicole McKay (developed the PAEDS Influenza database). Centre for Infectious Diseases & Microbiology: Prof. Lyn Gilbert, Linda Hueston (serosurvey), Brian O'Toole (analysis of serosurvey results); South East Sydney Area Laboratory Service (SEALS): Professor Bill Rawlinson and staff; Sydney Children's Clinical Trials Centre. PHREDSS staff (Public Health Real-Time Emergency Department Surveillance System), Centre for Epidemiology and Research, NSW Department of Health.

GLOSSARY

- APSU

Australian Pediatric Surveillance Unit

- CHW

Children's Hospital at Westmead

- CI

confidence interval

- EL

encephalitis lethargica

- GBS

Guillain-Barré syndrome

- HAPS

Hunter Area Pathology Service

- ICU

intensive care unit

- ILAE

International League Against Epilepsy

- ILI

influenza-like illness

- JHCH

John Hunter Children's Hospital

- LOS

length of stay

- NCIRS

National Centre for Immunization Research and Surveillance

- PAEDS

Pediatric Active Enhanced Disease Surveillance

- PMH

Princes Margaret Hospital Perth

- RCH

Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne

- SCH

Sydney Children's Hospital

- SEALS

South Eastern Area Laboratory Service

- VIDRL

Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory

- WCH

Women's and Children's Hospital Adelaide.

Footnotes

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed significantly to the study. R.B., E.J.E., and Y.Z. contributed to development of initial concept, protocols, and data collection forms, data analysis, and critical review of the manuscript. R.B. and G.K. were involved in analytical study design, data analysis, and preparing the first and subsequent drafts of the manuscript. R.C.D., C.J., K.M., L.H., and M.M. contributed to the manuscript. J.B., H.M., P.C.R., J.R., M.G., T.S., and B.W. contributed to surveillance, data collection and cleaning, study analysis, and drafts of the manuscripts.

STUDY FUNDING

This project was funded in part by the NSW Department of Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) H1N1 grant no: 633028. Activities of the APSU and NCIRS are supported by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. APSU is supported by the NHMRC (enabling grant no.: 402784 and practitioner fellowship no.: 457084, E. Elliott); the Creswick Foundation (fellowship: Y. Zurynski); NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (no. 1016272: H. Marshall); the Discipline of Paediatrics and Child Health and Faculty of Medicine, University of Sydney; the Children's Hospital at Westmead; and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians.

DISCLOSURE

G. Khandaker is an investigator in studies supported by Roche and National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Y. Zurynski reports no disclosures. J. Buttery has served on advisory and/or data safety monitoring committees for CSL Vaccines and GSK for which the Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) receives payments into an educational fund. MCRI has received travel support for J.B. to present scientific data at international meetings and he is an investigator in industry-sponsored vaccine trials. H. Marshall has participated as a board member of Global Advisory Boards for Merck, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline, has received travel support to present scientific data at international meetings, and is an Investigator in industry-sponsored clinical vaccine trials. P.C. Richmond is a member of the Vaccine Trials Group. The Vaccine Trials Group has received institutional funding for research from vaccine providers including CSL Biotherapies, Sanofi Pasteur, Baxter, and GlaxoSmithKline. Peter Richmond has also previously been a member of a CSL Limited vaccine advisory board and received travel support from Baxter and Pfizer to present scientific data at international meetings. R.C. Dale, J. Royle, M. Gold, T. Snelling, B. Whitehead, and C. Jones report no disclosures. L. Heron has performed consultancy work for Novartis for which payment was made to the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance. He has had travel expenses covered by GSK and has conducted sponsored research and investigator-driven research with funding from GSK, Wyeth, Merck, CSL, Roche, and Sanofi Pasteur. M. McCaskill, K. Macartney, and E.J. Elliott report no disclosures. R. Booy has received financial support from CSL, Sanofi, GSK, Roche, Novartis, and Wyeth, to conduct research and present at scientific meetings. Any funding received is directed to an NCIRS research account at The Children's Hospital at Westmead and is not personally accepted by Professor Booy. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newland JG, Laurich VM, Rosenquist AW, et al. Neurologic complications in children hospitalized with influenza: characteristics, incidence, and risk factors. J Pediatr 2007;150:306–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizuguchi M, Yamanouchi H, Ichiyama T, Shiomi M. Acute encephalopathy associated with influenza and other viral infections. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 2007;186: 45–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: update 112. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2010_08_06/en/index.html Accessed September 2010

- 4.Foley PB. Encephalitis lethargica and influenza: I: the role of the influenza virus in the influenza pandemic of 1918/1919. J Neural Transm 2009;116:143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garten RJ, Davis CT, Russell CA, et al. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science 2009;325:197–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Records and Information Privacy Act, 2002. Available at: http://www.lawlink.nsw.gov.au/lawlink/privacynsw/ll_pnsw.nsf/pages/PNSW_03_hripact Accessed November 2010

- 7.Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia 2010;51:676–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granerod J, Cunningham R, Zuckerman M, et al. Causality in acute encephalitis: defining aetiologies. Epidemiol Infect 2010;138:783–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glaser CA, Gilliam S, Schnurr D, et al. In search of encephalitis etiologies: diagnostic challenges in the California Encephalitis Project, 1998–2000. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:731–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Augarten A, Aderka D. Alice in Wonderland syndrome in H1N1 influenza: case report. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011;27:120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Baghli F, Al-Ateeqi W. Encephalitis-associated pandemic A (H1N1) 2009 in a Kuwaiti girl. Med Princ Pract 2011;20:191–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baltagi SA, Shoykhet M, Felmet K, Kochanek PM, Bell MJ. Neurological sequelae of 2009 influenza A (H1N1) in children: a case series observed during a pandemic. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010;11:179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Neurologic complications associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in children: Dallas, Texas, May 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:773–778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi SY, Jang SH, Kim JO, Ihm CH, Lee MS, Yoon SJ. Novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viral encephalitis. Yonsei Med J 2010;51:291–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ekstrand JJ, Herbener A, Rawlings J, et al. Heightened neurologic complications in children with pandemic H1N1 influenza. Ann Neurol 2010;68:762–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.German-Diaz M, Pavo-Garcia R, Diaz-Diaz J, Giangaspro-Corradi E, Negreira-Cepeda S. Adolescent with neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010;29:570–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haktanir A. MR imaging in novel influenza A(H1N1)-associated meningoencephalitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010;31:394–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwata A, Matsubara K, Nigami H, et al. Reversible splenial lesion associated with novel influenza A (H1N1) viral infection. Pediatr Neurol 2010;42:447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kedia S, Stroud B, Parsons J, et al. Pediatric neurological complications of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1). Arch Neurol 2011;68:455–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lister P, Reynolds F, Parslow R, et al. Swine-origin influenza virus H1N1, seasonal influenza virus, and critical illness in children. Lancet 2009;374:605–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyon JB, Remigio C, Milligan T, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy in a child with H1N1 influenza infection. Pediatr Radiol 2010;40:200–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariotti P, Iorio R, Frisullo G, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy during novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Ann Neurol 2010;68:111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin A, Reade EP. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy progressing to brain death in a pediatric patient with novel influenza A (H1N1) infection. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:e50–e52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Leary MF, Chappell JD, Stratton CW, Cronin RM, Taylor MB, Tang YW. Complex febrile seizures followed by complete recovery in an infant with high-titer 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:3803–3805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omari I, Breuer O, Kerem E, Berger I. Neurological complications and pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. Acta Paediatr 2011;100:e12–e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ormitti F, Ventura E, Summa A, Picetti E, Crisi G. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy in a child during the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemia: MR imaging in diagnosis and follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2010;31:396–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rellosa N, Bloch KC, Shane AL, Debiasi RL. Neurologic manifestations of pediatric novel H1N1 influenza infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2011;30:165–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sánchez-Torrent L, Triviño-Rodriguez M, Suero-Toledano P, et al. Novel influenza A (H1N1) encephalitis in a 3-month-old infant. Infection 2010;38:227–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Surana P, Tang S, McDougall M, Tong CY, Menson E, Lim M. Neurological complications of pandemic influenza A H1N1 2009 infection: European case series and review. Eur J Pediatr 2011;170:1007–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thampi N, Bitnun A, Banner D, et al. Influenza-associated encephalopathy with elevated antibody titers to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza. J Child Neurol 2011;26:501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Webster RI, Hazelton B, Suleiman J, Macartney K, Kesson A, Dale RC. Severe encephalopathy with swine origin influenza A H1N1 infection in childhood: case reports. Neurology 2010;74:1077–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yıldızdaş D, Kendirli T, Arslanköylü AE, et al. Neurological complications of pandemic influenza (H1N1) in children. Eur J Pediatr 2010;170:779–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lester-Smith D, Zurynski YA, Booy R, Festa MS, Kesson AM, Elliott EJ. The burden of childhood influenza in a tertiary paediatric setting. Commun Dis Intel 2009;33:209–215 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Surveillance for pediatric deaths associated with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection: United States, April–August 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:941–947 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhat N, Wright JG, Broder KR, et al. Influenza-associated deaths among children in the United States, 2003–2004. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2559–2567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sachedina N, Donaldson LJ. Paediatric mortality related to pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in England: an observational population-based study. Lancet 2010;376:1846–1852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2010. 2010 Pandemic Vaccination Survey: Summary Results. Cat. no. PHE 128. Canberra: AIHW; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimberlin DW, Shalabi M, Abzug MJ, et al. Safety of oseltamivir compared with the adamantanes in children less than 12 months of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010;29:195–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schonberger LB, Bregman DJ, Sullivan-Bolyai JZ, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome following vaccination in the National Influenza Immunization Program, United States, 1976–1977. Am J Epidemiol 1979;110:105–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin JK, Khandaker G, Rashid H, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccine: systematic review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respi Viruses 2011;5:299–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.