Abstract

Young adults experience problematic responses to loss more often than is commonly recognized. Few empirical studies have examined the contribution of intra- and interpersonal characteristics to grief and depression in bereaved young adults. This study investigated the association of dependency and quality of the relationship with the deceased (i.e., depth and conflict) with complicated grief (CG) and depression. Participants were 157 young adults aged 17–29 who experienced loss of a family member or close friend within the past three years (M = 1.74 years). Participants completed the Inventory of Complicated Grief, Beck Depression Inventory, Depth and Conflict subscales of the Quality of Relationships Inventory, and the Dependency subscale of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire. Relationships among dependency and interpersonal depth and conflict and CG and depression were examined through analyses of covariance. Sixteen percent of participants met criteria for CG and 34% had mild to severe depression. Dependency and depth were independently related to CG and dependency was related to depression, but the pattern of associations was somewhat different for each outcome. Greater depth was associated with CG, at both high and low levels of dependency. High levels of dependency were related to more depressive symptoms. Interpretation of the findings is limited by the relatively small sample size and cross-sectional design. CG and depression are related but distinct responses to loss. Although dependency is associated with both CG and depression following loss, relationships between the bereaved and deceased that are characterized by high levels of depth are particularly related to the development of CG symptoms.

Keywords: grief, bereavement, young adults, relationship quality, dependency

Introduction

Most individuals have experienced the death of a loved one by the time they reach college age (U.S. Department of Education, 2007),with 81.3% of college students having experienced a loss within their extended family and 60% having experienced the loss of a friend (Balk, 1997).Approximately 3.5% of young adults have lost a parent prior to age 18 (Social Security Administration, 2000),and nearly 8% of those under age 25 report having lost a sibling (Fletcher et al., 2012).In this age group (i.e., 18–25 year olds), grief is associated with academic difficulties, and may interfere with the developmental, occupational, and social tasks associated with young adulthood (Balk & Vesta, 1998; Hardison et al., 2005; Janowiak et al., 1995).In fact, young adult bereaved often experience intense and prolonged grief, decrement in health, increased physician visits for both physical and emotional problems, and increased drug, alcohol, and tobacco use following loss (Brent et al., 2009; Melhem et al., 2004; Parkes, 1987; Stroebe & Stroebe, 1987). However, despite the prevalence of loss experiences in young adults, and the potential for problematic grief responses, this age group has received relatively limited empirical attention.

Psychological responses to loss of a family member or friend are complex, and vary in intensity and types of symptoms (Zisook & Shear, 2009). Although many bereaved individuals experience a transient period of grief and mild to moderate depression (Bonanno et al., 2002, 2007; Shear et al., 2011), a subset of approximately 10–20% has a more chronic and intense response, and may experience complicated grief reactions (Bonanno & Kaltman, 2001; DeVaul & Zisook, 1976; Shear et al., 2011; Prigerson et al, 2009; Middleton et al., 1998; Zisook et al., 2010). Although the symptoms of complicated grief and depression can overlap, there is strong support to conceptualize and classify complicated grief as distinct from a major depressive episode (Boelen & Van den Bout, 2005; Shear et al., 2011; Prigerson et al., 2009; Zisook & Shear, 2009).

The relationship of interpersonal and personality characteristics to complicated grief and depression following loss has been infrequently examined. There has been little investigation of whether personality variables (i.e., dependency) or the quality of the relationship between the bereaved and deceased (i.e., depth, conflict) may play a role in the development of complicated grief or depression, particularly among young adults. Previous research has suggested an association between personality variables (i.e., dependency) and depression (Blatt, 1974; Blatt et al., 1976). The concept of dependency has traditionally focused on issues of interpersonal relatedness, including concerns regarding potential abandonment and/or social rejection, loneliness, and loss (Blatt, 1974). Those who are identified as dependent have a tendency to be motivated by hopes of obtaining and maintaining nurturance, support, and guidance from others (Denckla, Mancini, Bornstein, & Bonanno, 2011; Bornstein, 2011). Dependency has been associated with chronic or unresolved grief following loss of a loved one (Bonanno et al., 2002; Parkes & Weiss, 1983; Prigerson et al., 2000; Shuchter & Zisook, 1993). High levels of dependency in combination with interpersonal conflict or loss are also associated with depression (Johnson et al., 2002; Johnson et al., 2007; Nietzel & Harris, 1990).

Closeness and conflict between the bereaved and deceased prior to loss are aspects of the quality of a relationship that appear to be important to the grief response (Holland & Neimeyer, 2011; Packman et al., 2006; Servaty-Seib & Pistole, 2006). In one of the only studies specifically focused on relationship closeness with the deceased in young adults, high level of closeness was associated with negative social changes and academic consequences and mental health problems in bereaved college students (Walker, Hathcoat, & Noppe, 2011). However, the few studies specifically examining both closeness and conflict between the bereaved and deceased have focused on marital relationships and resulted in discrepant findings (Abakoumkin et al., 2010; Bonanno et al., 1998; Carr et al., 2000; Futterman et al., 1990; Prigerson et al., 2000). The degree of closeness or depth of a relationship, which identifies the extent to which an individual positively values and is committed to a relationship, is considered security-enhancing, and after loss may contribute to the development of complicated grief or depression (Van Doorn et al., 1998).Positive relationships characterized by high levels of satisfaction have been related to the core grief symptom of ‘yearning’ (Bowlby, 1980; Parkes, 1996; Prigerson et al., 2009; Stroebe et al., 2010).

Interpersonal conflict, or a troubled, ambivalent significant relationship, has been theorized to result in a particularly difficult grief response. Such relationships with the bereaved are characterized by an initial absence of expressed grief, followed by severe grief symptoms, guilt, self-reproach, and persistent negative feelings about past experiences (Hobfoll & London, 1986; Parkes, 1983; Rando, 1993; Gamino et al., 1998).

Despite the prevalence of loss in young adults, few studies have examined the predictors for particular grief responses. Specifically, risk factors for the development of complicated grief as compared to depression need to be identified in young adults who have experienced loss. Our study examined grief and depression in young adults who lost a family member or close friend within the past three years. We investigated the influence of the quality of the relationship (i.e., the level of depth and conflict within the preloss relationship) and the bereaved individual’s degree of dependency on the development of depression and complicated grief. Specifically, we explored whether these particular inter- and intrapersonal characteristics have a differential effect on the development of depression and complicated grief following loss among young adults.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

The study protocol and all consent and study procedures were initially approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pittsburgh, and approval was received to collect data at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Full-time and part-time undergraduate students enrolled in Psychology courses at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst were recruited for participation in the study. The primary inclusion criterion was to have either experienced a significant loss of a family member or close friend within the past three years. Prospective participants who had experienced a loss longer than three years prior to the study were excluded from the study.

Participants were informed that they would be asked about whether they had experienced a recent loss, their relationship to the deceased, the length of time since the death, and their reactions to the loss. They completed questionnaires to assess current and past thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and physical symptoms. Participants were notified that they could withdraw at any point in their study involvement without penalty or loss of course credit. The researcher was available to answer any of the participants’ questions regarding the measures or study participation. Following completion of the questionnaires, the participants were debriefed, given a course credit slip for their involvement in the study, and thanked for their time. Participation in the study lasted approximately 1 hour.

Participants were bereaved young adults (n = 157) who had lost an immediate family member (15.3%; n = 17), other relative (38.9%; n = 61), or close friend (43.2%; n = 68) within the past three years. Twenty-seven percent reported the loss occurred 0–6 months prior to the study, 17% experienced the loss in the previous 6–12 months, 24% in the previous 1–2 years, and 32% in the previous 2–3 years (M = 1.74 years; median = 2 years). Cause of death was due to: medical reasons (58%; n = 90); accident (26.3%; n = 41); suicide (10.3%; n = 16); or homicide (3.8%; n = 6). Participants ranged in age from 17 to 29 (M = 20.2 years; SD = 2.02), and the majority were female (82%; n = 129), unmarried (99%; n = 155), and full-time students (94%; n = 147). Most participants were white (87.2%; n = 136), and the remaining were African-American (5.1%), Asian-American (1.9%), Latino (1.9%), or Other (3.8%). The majority reported being religious (75.8%). Type of loss (i.e., loss of a family member, friend, or other relative) was not associated with any demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, time since loss, and cause of death). Cause of death and time since loss were also not associated with our predictor or outcome variables.

Measures

Complicated Grief

The Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG; Prigerson et al., 1995) is a 19-item self-report measure of traumatic grief symptoms, and distinguishes between uncomplicated and complicated bereavement. Participants reported the frequency (0 = never to 4 = always) of current emotional, behavioral, and cognitive states related to their loss. Previous studies have determined that scores of 30 or greater (Shear et al., 2005)are generally considered indicative of complicated grief. A cut-off of 30 or greater was categorized in this study as a high level of complicated grief. The ICG has good reliability and high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .94) and convergent and criterion validity (Prigerson et al., 1995, 1999).

Depression

Depression was assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1961; Beck, 1967). The BDI consists of 21 items that measure the number and severity of depressive symptoms within the past week on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. Depression was categorized using clinical cut-off scores determined by Beck et al. (1961) into minimal (scores 0–9), mild (scores 10–18), moderate (scores 19–29), and severe (30–63) depression groups. The BDI has high internal consistency (split-half reliability= .93), test-retest reliability, and strong concurrent, discriminant, and construct validity (Beck, 1967).

Quality of the Relationship

The Quality of Relationship Inventory (QRI; Pierce et al., 1991) was used to assess depth and conflict of the relationship with the deceased in bereaved participants. The QRI is a 39-item scale that assesses perceptions of interpersonal depth and conflict, and availability of social support within relationships. This study specifically focused on the 17 items included in the depth and conflict subscales. The 5-item depth subscale measures the extent to which an individual is committed to a specific relationship and positively values it (e.g., How significant was this person in your life?; How positive a role did this person play in your life?). The 12-item conflict subscale assesses the extent to which the relationship is a source of conflict and ambivalence (e.g., How often did you have to work hard to avoid conflict?; How much did you argue with this person?; How angry did this person make you feel?). For this study, participants were asked to think about their relationship with their family member or friend, when he or she was alive, and to rate the frequency and intensity of their experiences and feelings on a scale ranging from 0 (never or not at all) to 4 (always or extremely). In the current study, depth scores ranged from 1–20 and conflict scores ranged from 0–37. Based on this distribution of scores, values of 15 or greater on the depth subscale and 13 or greater on the conflict subscale represented the top 25% of scores and were categorized as high levels of depth and conflict. Discriminant validity of the QRI is strong, and internal reliability is high, with alpha coefficients of .83 and .88 (mother), .86 and .88 (father), and .84 and .91 (friend) for the depth and conflict subscales, respectively (Pierce et al, 1991).

Dependency

The Dependency subscale of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (DEQ; Blatt et al., 1976) was used to measure qualities of dependency in interpersonal relationships in general, and did not specifically address the loss relationship. The DEQ Dependency subscale includes 26 items that assess feelings of helplessness, fears and apprehensions about separation, abandonment, and rejection, and concerns about potential loss, and responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Based on the distribution of scores in the current study (range 43 – 155), a value of 121 or greater represented the top 25% of scores and indicated high dependency. Evidence for the construct validity of the DEQ subscales has been observed in clinical and college populations (Beck et al., 1979; Zuroff & Mongrain, 1987; Zuroff et al., 1990; Zuroff et al., 1983), and test-retest reliabilities were found to be high at 5 and 13 weeks (r = .89 and r = .81, respectively).

Approach to Statistical Analyses

Chi-squares, analyses of variance, and correlation analyses were initially conducted to assess whether there were significant demographic differences associated with the Dependency, Depth, and Conflict groups (categorized as high versus low), or relationships with the outcome variables, complicated grief and depression. In cases in which differences were found, these background variables were included in further analyses as covariates.

Differences among Dependency, Depth, and Conflict groups and the subsequent two-way interaction between Dependency and Depth groups in CG and depression were evaluated using one-way analyses of variance and covariance. In order to correct for multiple comparisons associated with studying two outcomes, the p value was set at 0.025 (0.05/2). Post hoc analyses (Tukey’s HSD) were performed to identify specific differences following the finding of significant Dependency and Depth interaction effects. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 19 (IBM Corp., 2010).

Results

Complicated Grief and Depression

Sixteen percent of the bereaved participants (n = 25) met criteria for complicated grief. Twenty-nine percent of the sample (n = 45) reported mild depression, and 6% were classified with moderate (4%; n = 6) or severe (2%; n = 3) depression. Twenty percent of those with complicated grief had moderate to severe depression. Among those with moderate and severe depression, 50% and 66.7%, respectively, had complicated grief. Those who reported no religious preference reported more complicated grief symptoms, F(1,155) = 5.81, p = .017, and depression, F(1,154) = 11.07, p = .001, than those with a religious preference. No additional demographic characteristics, including gender, age, ethnicity, and marital status were associated with complicated grief and depression. We also examined the relationship of our predictor variables, dependency, depth, and conflict, with participants’ demographic characteristics. There were differences in levels of dependency based on gender, F(1,153) = 6.46, p = .012, with females reporting more dependency than males. There were no additional relationships between demographic characteristics and the variables of interest that attained significance. Religion and gender were included in analyses as covariates as appropriate. Bivariate pairwise correlations indicated mild collinearity between predictor variables depth and conflict (r = .165, p = .039), and dependency and conflict (r = .197, p = .015), and a nonsignificant relationship between depth and dependency (r = .038).

Complicated Grief: Dependency, Depth, and Conflict

The associations of each of the personality and quality of relationship variables to complicated grief were examined categorically, classifying participants into high (top 25%) and low (75%) categories based on their depth, conflict, and dependency scores (Table 1). Religion was included in a covariate in analyses examining depth and conflict groups and complicated grief, and religion and gender were included as covariates in the ANCOVA examining dependency groups and CG. A significant positive association was found between depth and complicated grief, F(1,155) = 35.04, p ≤ .001, with bereaved participants who reported greater depth within the relationship experiencing higher levels of complicated grief. A similar relationship was found between dependency and complicated grief, F(1,152) = 5.79, p = .017, with those who experienced higher levels of dependency also reporting more complicated grief. The relationship between conflict and CG. although not significant at the 0.025 level, F(1,154) = 4.99, p = .027, suggests a trend for those who experienced more conflict to report higher levels of complicated grief.

Table 1.

Relationship of the Depth, Conflict, and Dependency groups and complicated grief and depression scores

| Complicated Grief M (SD) |

Depression M (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Depth | ||

| Low | 16.52 (10.44) | 7.51 (5.99) |

| Higha | 28.68 (11.14)*** | 9.91 (8.55) |

| Conflict | ||

| Low | 18.39 (11.82) | 7.32 (6.21) |

| Higha | 23.60 (11.16) | 10.26 (7.98) |

| Dependency | ||

| Low | 18.45 (11.28) | 6.60 (5.86) |

| Higha | 24.33 (12.91)* | 13.03 (7.62)*** |

High level Depth, Conflict, and Dependency groups are represented by participants with scores in the top quartile.

p ≤ .025;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001.

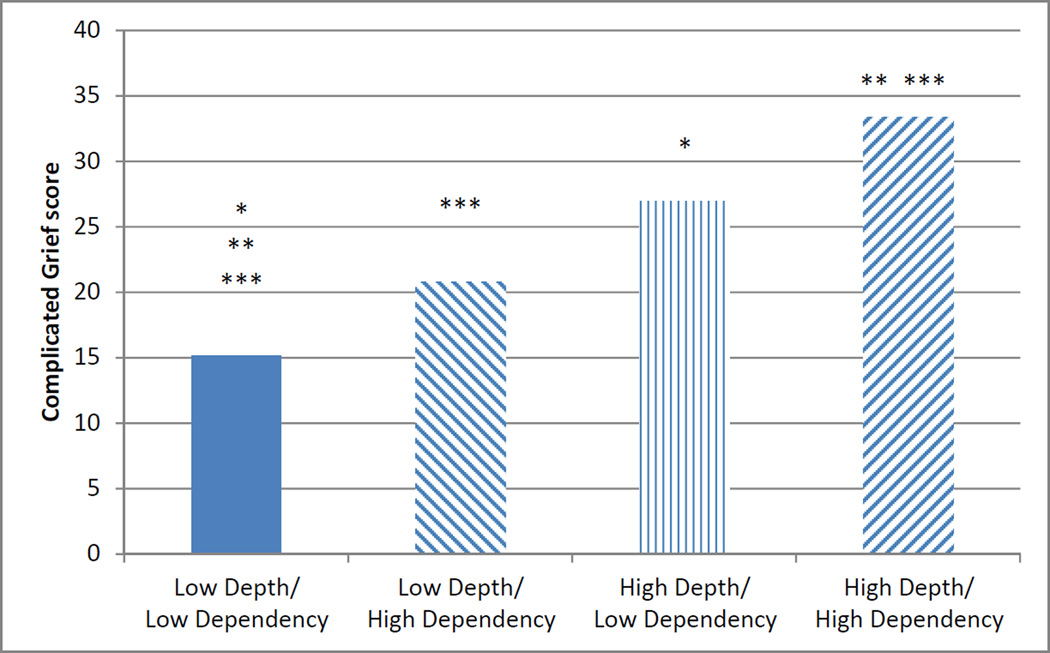

We further explored the two-way interaction of depth and dependency by comparing the mean complicated grief scores for the low (75%) and high (top 25%) categories of the predictor variable interaction groups. We again found differences in levels of complicated grief based on Depth and Dependency, F(3,152) = 13.75, p < .001 (Figure 1). Post hoc analyses indicated that High Depth × Low Dependency and High Depth × High Dependency groups reported more complicated grief symptoms (M = 26.94, SD = 10.86; and M = 33.36, SD = 11.49) than the Low Depth×Low Dependency group (M = 15.13, SD = 9.62). The High Depth × High Dependency group also reported more complicated grief than the Low Depth × High Dependency group (M = 20.79, SD = 11.81). Again, greater depth in the relationship was strongly related to CG, regardless of whether it is associated with low or high levels of dependency.

Figure 1.

Relationship of Complicated Griefa to Dependencyb and Depthc in the Relationship to the Deceased

Note.

aInventory of Complicated grief score.

bDepressive Experiences Questionnaire Dependency subscale score.

cQuality of Relationships Inventory Depth subscale score.

*, **, and *** identify mean group scores that are significantly different.

Depression: Dependency, Depth, and Conflict

The relationships between each of the personality and quality of relationship variables and depression were also examined categorically, with religion and gender included as covariates (Table 1). When groups of participants with low and high levels of dependency were compared, a significant relationship was found between Dependency groups and depression, F(1,151) = 22.74, p ≤ .001, with bereaved participants who experienced higher levels of dependency also reporting more depression. A significant relationship was not found between Depth or Conflict groups and depression; therefore, further two-way interaction analyses were not performed for these variables.

Discussion

Young adults experience problematic reactions following the loss of a family member or close friend with more frequency than is typically recognized. Our results indicate that at approximately 1–2 years after loss of a significant friend or relative, 16% of bereaved young adults met criteria for complicated grief and 34% had mild to severe depression. The level of depth in the relationship prior to loss and the specific personality trait of dependency appear to play different roles in the development of complicated grief compared to depression.

In our study, dependency and depth were independently associated with complicated grief. Closer examination of the relationship between dependency and depth revealed that each variable operated differently in influencing complicated grief responses. Specifically, the effect of dependency on complicated grief was moderated by the level of depth of the relationship. Higher depth in the relationship was associated with more complicated grief at both high and low levels of dependency (Figure 1). The degree of depression reported by the bereaved participants was influenced only by their level of dependency, independent of depth or conflict within the relationship. These results suggest that a complicated grief response in young adults is more related to interpersonal characteristics (i.e., depth) and dependency, and a depressive response to loss is more related to the personality trait of dependency. We found no significant association of conflict to either complicated grief or depression. There was a suggestive finding, however, which should be examined in future studies of a larger sample of young adults. Similarly, a larger sample would allow for analysis of complicated grief and depression, adjusting for each other, and aid in interpretation and further understanding of the comorbidity between complicated grief and depression.

Similar to our findings related to the role of depth, previous research has found that feelings of trust, security, intimacy, and mutual support in a relationship are associated with increased grief following loss (Mancini et al., 2009; van Doorn et al., 1998). However, it is important to note that these findings were specific to older adults. Further research on these factors in young adults is suggested for a more comprehensive understanding of the role of relationship quality in response to loss in this specific age group. Although dependency is often found to have an important role in the development of depression, few studies have examined the relationship between dependency and depression specifically in bereaved individuals. However, high dependency has been associated with chronic grief, characterized by symptoms of persistent, intense yearning and distress (Bonanno et al., 2002; Vanderwerker et al., 2006; van Doorn et al., 1998).

The findings of this study are limited by the relatively small sample size and cross-sectional design. In addition, qualities of the preloss relationship were assessed retrospectively, which may result in recall bias. The severity of grief may influence bereaved individuals’ reports of preloss ambivalence or conflict (Bonanno et al., 1998). Individuals’ reluctance to report ambivalent feelings about their deceased friend or family member can affect reliability of assessment (Bonanno & Kaltman, 1999; Thompson & Zanna, 1995).

By incorporating a longitudinal prospective study design and multiple methods of assessment, including clinical interview, in future studies, additional risk factors and the trajectory of grief responses over time can be further identified. Future studies would also benefit from the prospective assessment of perception of quality of the relationship, which may be influenced by the loss and could change over time, specifically from the period before the loss to after the loss.

It is important for studies to reference a specific period of time when asking about relationship quality. This study asked participants to think about their relationship with their family member or friend, when he or she was alive, to minimize the possibility that the bereaved are responding with respect to their current relationship to the deceased. However, there may still have been variability in response, based on whether the participants interpreted the question more generally or were thinking of a specific time period prior to the death. This may be a particular issue for losses following a chronic terminal illness.

Our results suggest that effective treatment for depression may benefit from an emphasis on strengthening internal resources, whereas treatment for complicated grief may need to address the characteristics of the relationship, in particular, the presence of depth. Further study of the roles of personality and interpersonal characteristics on the development of complicated grief and depression is needed. Research that focuses on styles of adult attachment, such as secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent styles (Hazan & Shaver, 1987), may also inform our understanding of depression and grief after loss of a friend or family member.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest or financial support, including direct or indirect financial or personal relationships, interests, and affiliations relevant to the subject matter of the manuscript, to disclose.

References

- Abakoumkin G, Stroebe W, Stroebe M. Does relationship quality moderate the impact of martial bereavement on depressive symptoms? J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2010;29:510–526. [Google Scholar]

- Balk DE. Death, bereavement and college students: A descriptive analysis. Mortality. 1997;2:207. [Google Scholar]

- Balk DE, Vesta LC. Psychological development during the four years of bereavement: a longitudinal case study. Death Stud. 1998;22:23–41. doi: 10.1080/074811898201713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression: Causes and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive Theory of Depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ. Levels of object representation in anaclitic and introjective depression. Psychoanal. Study Child. 1974;29:107–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, D’Affliti JP, Quinlan DM. Experiences of depression in normal young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1976;85:383–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Zohar AH, Quinlan DM, Zuroff DC, Mongrain M. Subscales within the dependency factor of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire. J. Pers. Assess. 1995;64(2):319–339. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6402_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, van der Bout J. Complicated grief, depression, and anxiety as distinct postloss syndromes: A confirmatory factor analysis study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2175–2177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Kaltman S. An integrative perspective on bereavement. Psychol. Bull. 1999;125(6):760–776. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Kaltman S. The varieties of grief experience. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001;20:1–30. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Neria Y, Mancini A, Coifman KG, Litz B, Insel B. Is there more to complicated grief than depression and posttraumatic stress disorder? A test of incremental validity. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2007;116(2):342–351. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Notarius CI, Gunzerath L, Keltner D, Horowitz MJ. Interpersonal ambivalence, perceived dyadic adjustment, and conjugal loss. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998;66:1012–1022. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Lehman DR, Tweed RG, Haring M, Sonnega J, Carr D, Neese RM. Resilience to loss and chronic grief: A prospective study from preloss to 18-months postloss. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002;83(5):1150–1164. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.5.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Vol. II: Separation: Anxiety and anger. New York/London: Basic Books/Hogarth; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss, Volume III: Loss, sadness, and depression. New York: Penguin Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Brent D, Melhem N, Donohoe MB, Walker M. The incidence and course of depression in bereaved youth 21 months after the loss of a parent to suicide, accident, or sudden natural death. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009;166:786–794. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08081244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D, House JS, Kessler RC, Nesse RM, Sonnega J, Wortman C. Marital quality and psychological adjustment to widowhood among older adults: A longitudinal analysis. J. Gerontol. Soc. Sci. 2000;55B:S197–S207. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.s197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles DR, Charles M. Sibling loss and attachment style: An exploratory study. Psychoanal. Psychol. 2006;23:72–90. [Google Scholar]

- DeVaul RA, Zisook S. Unresolved grief: Clinical considerations. Postgrad. Med. 1976;59(5):267–271. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1976.11714374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher J, Mailick M, Song J, Wolfe B. A sibling death in the family: Common and consequential. Demogr. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0162-4. Epub ahead of print, no pagination specified. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futterman A, Gallagher D, Thompson LW, Lovett S. Retrospective assessment of marital adjustment and depression during the first 2 years of spousal bereavement. Psychol. Aging. 1990;5:277–283. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamino LA, Sewell KW, Easterling LW. Scott & White grief study: An empirical test of predictors of intensified mourning. Death Stud. 1998;22:333–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hardison HG, Neimeyer RA, Lichstein KL. Insomnia and complicated grief symptoms in bereaved college students. Behav. Sleep Med. 2005;3:99–111. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987;52(3):511–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, London P. The relationship of self-concept and social support to emotional distress among women during war. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986;4:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan NS, DeSantis L. In: Adolescent sibling bereavement: Toward a new theory. Corr CA, Balk DE, editors. Springer, New York: Handbook of Adolescent Death and Bereavement; 1996. pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Holland JM, Neimeyer RA. Separation and traumatic distress in prolonged grief: The role of cause of death and relationship to the deceased. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2011;33:254–263. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation. IBM Corporation. NY: Armonk; 2010. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version, 19.0. [Google Scholar]

- Janowiak SW, Meital LR, Drapkin RG. Living with loss: A group for bereaved college students. Death Stud. 1995;19:55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes EM, Bernstein DP. Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1999;56:600–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Gould MS, Kasen S, Brown J, Brook JS. Childhood adversities, interpersonal difficulties, and risk for suicide attempts during late adolescence and early adulthood. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:741–749. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Zhang B, Prigerson HG. Investigation of a developmental model of risk for depression and suicidality following spousal bereavement. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2007;38(1):1–12. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini AD, Robinaugh D, Shear K, Bonanno GA. Does attachment avoidance help people cope with loss? The moderating effects of relationship quality. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009;65:1127–1136. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem NM, Day N, Shear MK, Day R, Reynolds CF, III, Brent D. Traumatic grief among adolescents exposed to a peer’s suicide. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:1411–1416. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton W, Raphael B, Burnett P, Martinek N. A longitudinal study comparing bereavement phenomena in recently bereaved spouses, adult children and parents. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 1998;32:235–241. doi: 10.3109/00048679809062734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, van den Berg S. Internalizing and externalizing problems as correlates of self-reported attachment style and perceived parental rearing in normal adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2003;12:171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzel MT, Harris MJ. Relationship of dependency and achievement/autonomy to depression. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1990;10:279–297. [Google Scholar]

- Packman W, Horsley H, Davies B, Kramer B. Sibling bereavement and continuing bonds. Death Stud. 2006;30:817–841. doi: 10.1080/07481180600886603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes CM. Research: Bereavement. Omega. 1987;1987;18:365–377. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes CM. Bereavement: Studies of Grief in Adult Life. 3rd ed. London: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes CM, Weiss RS. Recovery from Bereavement. New York: Basic Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce GR, Sarason IG, Sarason BR. General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: Are two constructs better than one? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991;61:1028–1039. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Bridge J, Maciejewski PK, Beery LC, Rosenheck RA, Jacobs SC, Bierhals AJ, Kupfer DJ, Brent DA. Influence of traumatic grief on suicidal ideation among young adults. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:1994–1995. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, Raphael B, Marwit SJ, Wortman C, Neimeyer RA, Bonanno G, Block SD, Kissane D, Boelen P, Maercker A, Litz BT, Johnson JG, First MB, Maciejewski PK. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS. Med. 2009:6e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, III, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, Frank E, Doman J, Miller M. The inventory of complicated grief: A scale to measure certain maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosenheck RA. Preliminary explorations of the harmful interactive effects of widowhood and marital harmony on health, health service use, health care costs. Gerontologist. 2000;40:349–357. doi: 10.1093/geront/40.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando TA. Treatment of Complicated Mourning. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Servaty-Seib HL, Pistole MC. Adolescent grief: Relationship category and emotional closeness. Omega. 2006;54:147–167. doi: 10.2190/m002-1541-jp28-4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF., III Treatment of complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2601–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Simon N, Wall M, Zisook S, Neimeyer R, Duan N, Reynolds C, Lebowitz B, Sung S, Ghesquiere A, Gorscak B, Clayton P, Ito M, Nakajima S, Konishi T, Melhem N, Meert K, Schiff M, O’Connor M-F, First M, Sareen J, Bolton J, Skritskaya N, Mancini AD, Keshaviah A. Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depress. Anxiety. 2011;28:103–117. doi: 10.1002/da.20780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuchter SR, Zisook S. In: The course of normal grief. Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO, editors. Cambridge University Press, New York: Handbook of Bereavement: Theory, Research, and Intervention; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Social Security Administration. Intermediate Assumptions of the 2000 Trustees Report. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W, Abakoumkin G, Stroebe M. Beyond depression: Yearning for the loss of a loved one. Omega. 2010;61:85–101. doi: 10.2190/OM.61.2.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W, Stroebe MS. Bereavement and Health: The Psychological and Physical Consequences of Partner Loss. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MM, Zanna MP. The conflicted individual: Personality-based and domain-specific antecedents of ambivalent social attitudes. J. Pers. 1995;63:269–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education, Emergency Response & Crisis Management (ERCM) Technical Assistance Center. Coping with the death of a student or staff member. ERCM Express. 2007;3:1–12. Retrieved from http://rems.edu.gov/docs/CopingW_Death_StudentOrStaff.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwerker LC, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Prigerson HG. An exploration of associations between separation anxiety in childhood and complicated grief in later life. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2006;194:121–123. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000198146.28182.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorn C, Kasl SV, Beery LC. The influence of marital quality and attachment styles on traumatic grief and depressive symptoms. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1998;186:566–573. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199809000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker AC, Hathcoat JD, Noppe IC. College student bereavement experience in a Christian university. Omega. 2011–2012;64(3):241–259. doi: 10.2190/om.64.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisook S, Shear K. Grief and bereavement: What psychiatrists need to know. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:67–74. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zisook S, Simon NM, Reynolds CF, III, Pies R, Lebowitz B, Young IT, Madowitz J, Shear MK. Bereavement, complicated grief, and DSM, Part 2: Complicated grief. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2010;71:1097–1098. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10ac06391blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Moskowitz DS, Wielgus MS, Powers TA, Franko DL. Construct validation of the Dependency and Self-Criticism scales of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire. J. Res. Pers. 1983;17:226–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Mongrain M. Dependency and self-criticism: Vulnerability factors for depressive affective states. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1987;96:14–22. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Quinlan DM, Blatt SJ. Psychometric properties of the Depressive Experiences Questionnaire in a college population. J. Pers. Assess. 1990;55:65–72. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]