Abstract

Approximately 8.3% of the United States (U.S.) population have either diagnosed or undiagnosed diabetes mellitus. Out of all the cases of diabetes mellitus, approximately 90–95% of these cases are type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D). Although the exact cause of T2D remains elusive, predisposing factors include age, weight, poor diet, and a sedentary lifestyle. Until recently the association between exposure to environmental contaminants and the occurrence of diabetes had been unexplored. However, recent epidemiological studies have revealed that elevated serum concentrations of certain persistent organic pollutants (POPs), especially organochlorine pesticides, are positively associated with increased prevalence of T2D and insulin resistance. The current study seeks to investigate if this association is causative or coincidental. Male C57BL/6H mice were exposed to DDE (2.0 mg/kg or 0.4 mg/kg) or vehicle (corn oil; 1 ml/kg) for five days via oral gavage; fasting blood glucose, glucose tolerance, and insulin challenge tests were performed following a seven day resting period. Exposure to DDE caused significant hyperglycemia compared to vehicle and this hyperglycemic effect persisted for up to 21 days following cessation of DDE administration. Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests and phosphorylation of Akt in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue following insulin challenge were comparable between vehicle and DDE treated animals. To determine the direct effect of exposure to DDE on glucose uptake, in vitro glucose uptake assays following DDE exposure were performed in L6 myotubules and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. In summary, subacute exposure to DDE does produce fasting hyperglycemia, but this fasting hyperglycemia does not appear to be mediated by insulin resistance. Thus, the current study reveals that subacute exposure to DDE does alter systemic glucose homeostasis and may be a contributing factor to the development of hyperglycemia associated with diabetes.

Keywords: persistent organic pollutants, organochlorine compounds, DDE, glucose, diabetes, C57BL/6 mice

2. Introduction

The prevalence of obesity (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) has increased at a staggering rate in the U.S. and is approaching epidemic proportions. Analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted during 2009–2010 revealed that 35.7% of U.S. adults over the age of 20 years were classified as being obese and 16.9% of U.S. children and adolescents were obese (Flegal et al. 2012; Ogden et al. 2012). These statistics are particularly alarming given that childhood obesity greatly increases the likelihood of being obese as an adult (Biro and Wien 2010; Whitaker et al. 1997). These data are of vital consequence to the healthcare system in the U.S. given that being obese or even overweight is intimately associated with other disease processes including dyslipidemias, hypertension, and T2D. Indeed, in 2011, 25.8 million people in the U.S. or 8.3% of the population were reported to have either diagnosed or undiagnosed diabetes (CDC 2011). Out of these cases of diabetes, it is estimated that 90–95% will be T2D (CDC 2011). The primary pathophysiological alteration in T2D is the development of insulin resistance in the liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue which leads to hyperinsulinemia and eventual hyperglycemia (DeFronzo 1997, 2004).

While the exact etiology of insulin resistance and the resulting T2D remains an enigma, it is most likely the result of a multifactorial process including several well established components such as genetic predisposition, diet, and sedentary lifestyle. However, these processes are most likely not sufficient to explain the ever increasing prevalence of T2D. Until recently, an environmental exposures component had not been proposed as a risk factor for the development of T2D. A major classification of chemicals that has recently been implicated as a possible causative factor in the development of T2D is the persistent organic pollutants (POPs). Common properties of these chemicals include long half-lives, bioaccumulation, and biomagnification up the food chain. One of the first POPs to be implicated through epidemiological associations with T2D was 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). Exposure to TCDD as a contaminant of Agent Orange has been positively associated with the development of T2D in veterans of the Vietnam Conflict (Kern et al. 2004; Michalek and Pavuk 2008). Empirical studies have shown that exposure to TCDD causes insulin resistance and subsequent T2D in experimental animals (Liu and Matsumura 1995). While TCDD is a POP, it is not as prevalent as some of the organochlorine insecticides or their bioaccumulative metabolites based on prevalence of detection in the general U.S. population. TCDD was detected in the serum of 7% of subjects in the 1999–2002 NHANES study whereas organochlorine pesticide compounds (OCs) such as DDE, trans-nonachlor, and oxychlordane were detected in the serum of 99.7%, 92.6%, and 82.9% of subjects in the 2003–2004 NHANES study, respectively (Lee et al. 2006; Patterson et al. 2009).

Like TCDD, these OCs have been positively associated with the occurrence of insulin resistance and diabetes through epidemiological studies. Recent studies have demonstrated through retrospective analysis of the 1999 to 2002 NHANES data that increasing serum concentrations of trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane are positively associated with insulin resistance (Lee et al. 2007). In addition, increasing serum concentrations of these OCs, including DDE, are positively associated with increased prevalence of diabetes and/or the metabolic syndrome (Lee et al. 2006). Interestingly, in this study, there was no association between obesity and diabetes in subjects with non-detectable levels of POPs (when all six categories of POPs were taken collectively). This observation suggests that the elevated serum concentration of POPs and not obesity promotes diabetes in these subjects. The possibility that background exposure to DDE may promote diabetes has been further substantiated by studies in non-diabetics where increased serum DDE concentrations predicted elevated homeostasis model assessment value for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) values as well as dyslipidemias (Lee et al. 2011). More recent studies by Kim et al. (2014) have revealed that elevated adipose concentrations of DDE are positively associated with diabetes and systemic insulin resistance indicated by increased HOMA-IR values. In studies examining the prevalence of diabetes in Swedish men and women, there was a significant correlation between serum DDE and prevalence of diabetes (Rignell-Hydbom et al. 2009; Rignell-Hydbom et al. 2007; Rylander et al. 2005). In addition to these studies of the Swedish population, Turyk et al. (2009a) determined in a cohort of Great Lakes sport fish consumers who were followed from a healthy, non-diabetic state to development of diabetes that DDE exposure was significantly associated with the incidence of diabetes. Taken together, these epidemiological studies provide a strong line of evidence suggesting elevated serum concentrations of POPs, especially the organochlorine pesticides or their metabolites, may play a role in the pathogenesis of T2D and metabolic dysfunction.

While the currently growing body of epidemiological evidence suggests a role of environmental exposures, especially OC exposures, in the pathogenesis of T2D, there is a lack of empirical evidence showing causality. Ruzzin et al. (2010) recently demonstrated that consumption of a diet contaminated with a mixture of POPs, including OCs, in conjunction with high fat feeding promoted increased weight gain, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in a rodent model. In addition to these studies, Ibrahim et al. (2011) also demonstrated that consumption of diets contaminated with POPs promoted insulin resistance and other pathophysiological alterations associated with the metabolic syndrome. A common feature of these two studies is that they both utilized a mixture of POPs and did not seek to delineate the role of individual OC compounds in these phenomena. Given the lack of empirical data to determine if exposure to POPs, especially the OCs alone and in combination, results in insulin resistance and altered glucose homeostasis, the current study was designed to determine if exposure to a highly prevalent organochlorine compound, DDE, alone can cause hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in a murine model and in vitro models of insulin sensitive tissues.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1 Chemicals

DDE (98% purity; Chem Service) was dissolved in corn oil (Sigma Aldrich) at concentrations of 0.4 mg/ml or 2.0 mg/ml for in vivo administration. For in vitro glucose uptake assays, DDE was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma Aldrich). D-glucose and solvents used for DDE extraction were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Human insulin (25 U/ml) used for intraperitoneal insulin challenge and glucose uptake assays was obtained from Gibco. [H3] 2-deoxy-D-glucose used for glucose uptake assays was obtained from Perkin Elmer.

3.2 Animal care

Male C57BL/6H mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories at six weeks of age. Animals were housed individually in polycarbonate cages in an AAALAC-approved animal facility under a twelve hour light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum unless they were subjected to fasting prior to glucose measurements or insulin challenge. All animal use protocols were approved by the Mississippi State University Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were allowed a four to five day acclimation period prior to administration of experimental compounds.

3.3 Experimental design

To determine the effect of exposure to DDE on fasting blood glucose concentrations, male C57BL/6H mice (n=10/group) were administered vehicle (corn oil; 1 ml/kg) or DDE (0.4 or 2.0 mg/kg) via oral gavage daily for five consecutive days which represent a subacute exposure. The 2.0 mg/kg dose was chosen as the high dose for the repeated administration paradigm currently utilized because previous studies revealed behavioral alterations (slight lethargy vs. 2.0 mg/kg) with a 10.0 mg/kg dose for 5 days. Administration of DDE over the span of 5 days was utilized to provide a low amount of DDE over a period of time rather than a single, large bolus of DDE to elevate systemic DDE concentrations. Following cessation of DDE or vehicle administration, animals were allowed to rest for seven days prior to fasting blood glucose measurements. Seven days following the last administration of DDE or vehicle, animals were fasted for six hours and blood glucose concentrations were measured with a handheld glucometer (AlphaTrak; Bayer Animal Health) via a tail nick (Ayala et al. 2010). Following blood glucose measurement, blood samples were obtained via cardiac puncture and tissues (liver, epididymal fat pads, and gastrocnemius muscle) were harvested and immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Whole blood samples were allowed to clot for thirty minutes on ice and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate the serum and cellular components. Serum samples were stored at −80°C until further analysis.

3.4 Time course of DDE-induced hyperglycemia

Analysis of fasting blood glucose levels seven days following the cessation of DDE administration revealed significant hyperglycemia compared to vehicle. To determine the duration of this hyperglycemic effect of DDE, male C57BL/6H mice (n=12–13/group) were administered either vehicle (corn oil; 1 ml/kg) or DDE (2.0 mg/kg) via oral gavage for five consecutive days as described above. Following DDE exposure, fasting blood glucose concentrations were measured at seven, fourteen, twenty one, and twenty eight days following the cessation of DDE administration. After the final fasting blood glucose measurement on the twenty eighth day following DDE administration, serum and tissue samples were obtained as described above.

3.5 Measurement of DDE concentrations in serum and tissue samples

Analysis of DDE in mouse serum, liver, and adipose tissue was performed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) following organic solvent extraction. The method, developed in our laboratories for extraction of organochlorine pesticides from human serum, was modified for mouse serum. An internal standard (50 μL) containing [C13] p,p′-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) at 0.01 μg/mL in hexane was added to 0.5 mL of mouse serum pooled from 3 mice (equal volumes) of the same treatment group. The sample was vortexed for 30 seconds and was allowed to sit for 60 sec. For mouse liver and adipose tissue, a 0.5 g sample of pooled liver or adipose tissue was homogenized and spiked with an internal standard (50 μL) containing [C13] p,p′-DDT at 0.01 μg/mL in hexane, mixed with 0.5 g of Hydromatrix (Agilent Technologies), and placed in the bottom of an Accelerated Solvent Extractor (ACE) cell (Dionex Corporation). The remainder of the cell was filled with Hydromatrix (10 g). Samples were extracted using a modification of EPA method 3545 using the ACE with a 50:50 mixture of acetone and hexane (USEPA 1998). The ACE method was as follows: a 2 minute static phase after a 5 minute pre-heat equilibrium, followed by an additional 2 minute static phase after the flush phase, a nitrogen purge for 150 seconds, and a final nitrogen purge for 60 seconds. The extracts (approximately 60 mL) were concentrated to 0.5 mL under a gentle stream of nitrogen in a TurboVap (Zymark Corporation), vortexed for 30 sec and transferred to graduated, solvent rinsed, conical vials.

For serum, liver, and adipose extracts, acetonitrile (2 mL) was added to the sample and vortexed for 10 seconds. The mixture was vortexed for 1 minute and centrifuged at 2500g for 10 min with the resultant supernatant decanted. Deionized water (2 mL) was added to the supernatant and the sample was vortexed for 30 seconds. The resultant mixture was aspirated into a DPX disposable pipette solid phase extraction column (DPX Labs) for 30 seconds. Using a 10 mL syringe the aqueous portion was then forced out of the column and discarded. The sorbent was aspirated with a wash solution (0.5 mL, 33%:67% acetonitrile:H2O) and DDE was eluted from the sorbent matrix by aspirating 10 sec with 1 mL of 1:1 (v/v) ethyl acetate/hexane (EtAc/hex) twice and the eluent was collected in a glass conical tube. Eluents were dried under a gentle stream of N2 and resuspended with 100 μL of EtAc/hex (1:1, v/v) to optimize recovery and was dried. The sample was resuspended in a final volume of 50 μL in EtAc/hex (1:1, v/v) and was transferred to a GC auto sampler vial for analysis.

DDE concentrations were determined by isotope dilution GC/MS using a modification of CDC method 6015.01. Samples were analyzed using an Agilent Technologies 6890N gas chromatograph connected to a 5975C triple-axis mass spectrometer. Two microliters of the concentrated extract were injected into the GC by splitless injection. Chromatographic separation of the individual compounds was achieved using a 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. DB-5MS ([5%-phenyl]-methylpolysiloxane, 0.25 m film thickness) capillary column (J&W Scientific) with helium as a carrier gas at a constant flow of 1 mL/min. The injector and transfer line temperatures were set at 275°C and 270°C, respectively. The initial column temperature, 100°C, was held for 1 min, increased to 220°C at 18°C/min, held for 1 min, increased to 300°C at 25°C/min, held for 5 min and finally increased to 320°C at 25°C/min and held for 5 min.

A targeted mass analysis was performed in electron ionization (EI+) mode using single ion monitoring (SIM) for DDE and the internal standard. Mass spectral ions monitored were 246.00 and 247.99, [M-Cl2];[M + 2-Cl2] for p,p′-DDE and 247.04 and 249.04, [L-CCl3];[L + 2-CCl3] for the internal standard, [C13] p,p′-DDT. The MS parameters included an ion source temperature of 230°C and electron energy of 40 eV. Analyte peaks acquired by SIM were quantified using Agilent ChemStation software. Limits of quantitation were 100 pg/L p,p′-DDE. Mean percent recoveries for DDE were greater than 85%. Areas under the curve were converted to ng/mL for serum and ng/g for liver and adipose tissue utilizing a standard curve generated from serum, liver, or adipose tissue spiked with five concentrations of DDE.

3.6 Measurement of adipokines and hormones

Serum concentrations of insulin, leptin, resistin, adiponectin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), monocyte/macrophage chemotractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and glucagon were measured by multiplex immunoassay (Millipore xMAP) per the manufacturer’s instructions in fasting serum samples obtained as described above.

3.7 Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT)

To determine the effect of DDE exposure on systemic glucose metabolism, male C57BL/6H mice (n=10/group) were administered vehicle (corn oil; 1 ml/kg) or DDE (2.0 mg/kg) via gavage for five consecutive days as described above. Seven days following cessation of DDE (2.0 mg/kg) administration, animals were fasted for 6 hours prior to intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing. Following a 6 hour fast, a baseline blood glucose measurement reading was taken with a handheld glucometer (AlphaTrak; Bayer Animal Health) via a tail nick (Ayala et al. 2010). Following baseline glucose measurement, animals were injected intraperitoneally with 1 g/kg of glucose. Following glucose injection, blood glucose was measured at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes to track circulating glucose concentrations.

3.8 Acute insulin stimulation

To assess the patency of the insulin signaling pathway following DDE exposure, male C57BL/6H mice (n=10/group) were administered vehicle (corn oil; 1 ml/kg) or DDE (2.0 mg/kg) via gavage for five consecutive days as described above. Seven days following the cessation of DDE exposure, animals were fasted for 6 hours then subjected to an intraperitoneal insulin challenge to assess the effect of DDE exposure on the insulin signaling pathway in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. Briefly, vehicle or DDE (2.0 mg/kg) exposed animals were injected intraperitoneally with insulin (10 U/kg; n=5/group) or vehicle (0.9% NaCl; n=5/group) ten minutes prior to sacrifice. Upon sacrifice, liver, gastrocnemius muscle, and epididymal adipose tissues were harvested from each animal, immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis via SDS-PAGE and Western blot.

3.9 SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis

Gastrocnemius muscle, liver, and adipose tissue samples (~50 mg each; n=5) from vehicle (1 ml/kg) or DDE (2.0 mg/kg) treated animals were lysed with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, and protease/phosphatase inhibitors). Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad). Lysates (50 μg protein per well) were subjected to SDS-PAGE using a 10% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane membrane, blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in tris buffered saline (TBS; pH 7.4) with 0.1% tween 20 (TBS-T), and then incubated with either mouse anti-phosphoAkt (Ser473, Santa Cruz Biotech) or rabbit anti-Akt (Santa Cruz Biotech) primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Mouse anti-β-actin immunoreactivity was used as a loading control for each lane. Following incubation with primary antibodies, blots were washed three times in TBS-T and incubated with secondary antibody (anti-mouse or anti-rabbit HRP; Santa Cruz Biotech) for 45 minutes at room temperature. Proteins were visualized with Immobilon chemiluminescent reagent (Millipore) and digital images captured with the ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad). The integrated density of each band was determined using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) image analysis software. The mean integrated densities were compared to determine statistically significant differences between treatment groups.

3.10 In vitro glucose uptake assays

3T3-L1 preadipocytes and L6glut4myc myoblasts (generous gift from Dr. Amira Klip) were seeded in 12 well plates and induced to differentiate as previously described (Howell and Mangum 2011; Ueyama et al. 1999). Following differentiation into mature adipocytes or myotubules, individual wells (n=8/group) were treated for 24 hours with vehicle (DMSO; 0.025%) or DDE (0.2, 1, 5, or 20 μM) in normal growth media then glucose uptake was assessed as previously described with minor modifications (Kozma et al. 1993). Three hours prior to insulin (100 nM) stimulation, normal growth media was removed from the plates, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and serum-free media (1% bovine serum albumin) containing vehicle or DDE was added. Serum free media was then removed and cells were stimulated with insulin (100 nM) in PBS for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated in 1 ml per well of PBS containing 0.1 mM 2-deoxyglucose and 1 μCi/ml [H3] 2-deoxy-D-glucose for 5 minutes at 37°C. Following glucose exposure, cells were washed three times with ice cold PBS then solubilized with 0.4 ml of 1% SDS. The cell lysate was added to 4 ml of scintillation fluid and radioactivity measured using a Packard 2900 liquid scintillation counter (Perkin Elmer). [H3] glucose uptake is expressed as counts per minute.

3.11 Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for each treatment group or biochemical measurement time point. For comparisons with multiple groups or time points, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons was used to determine statistically significant differences for parametric data. To determine statistically significant differences for nonparametric data, one way ANOVA on ranks with a Tukey’s or Dunn’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons was utilized. When comparing vehicle versus DDE treatment in experiments with time matched vehicle controls, a Student’s t-test was utilized. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was used to indicate a statistically significant difference between groups.

4. Results

4.1 Effects of DDE exposure on body weight, fasting glucose, adipokines, and metabolic hormones

As illustrated in Table 1, administration of DDE for 5 days followed by a 7 day resting period significantly increased raw body weight in both DDE treatment groups compared to vehicle, however, when body weights were normalized to weight at the beginning of dosing there was no statistically significant increase in weight gain. With regards to systemic glucose concentrations, DDE exposure resulted in a dose dependent increase in fasting blood glucose concentrations. Administration of DDE (0.4 mg/kg) did not significantly elevate fasting blood glucose levels when compared to the vehicle group (171.8 ± 7.4 vs. 173.8 ± 4.4 mg/dL, respectively). However, administration of DDE (2.0 mg/kg) significantly elevated fasting blood glucose concentrations when compared to vehicle (195.1 ± 5.5 vs. 173.8 ± 4.4 mg/dL, respectively), a 12.3% change from vehicle.

Table 1.

Effect of DDE administration on body weight, serum hormones, and adipokines. Animals were administered either vehicle or DDE (0.4 mg/kg or 2.0 mg/kg) then allowed to rest for 7 days prior to fasting blood glucose measurements. Data represent the mean with SEM in parenthesis of each treatment group (n=7–10/group). Statistically significant differences were determined with a one-way ANOVA using a Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons.

| Analyte | Vehicle (1 ml/kg) | DDE (0.4 mg/kg) | DDE (2.0 mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 24.7 (0.4) | 27.0 (0.7)* | 27.3 (0.4)* |

| % change in weight | 3.3 (1.3) | 5.8 (1.8) | 7.9 (0.8) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 173.8 (4.4) | 171.8 (7.4) | 195.1 (5.5)*# |

| Insulin (uU/mL) | 31.6 (3.3) | 30.9 (7.0) | 37.5 (8.1) |

| Glucagon (pg/mL) | 8.4 (0.4) | 8.9 (2.0) | 8.0 (1.2) |

| Leptin (pg/mL) | 1747.7 (231.9) | 3108.6 (1373.6) | 2826.8 (634.0) |

| Resistin (pg/mL) | 2837.8 (430.9) | 3148.1 (541.0) | 3220.6 (190.7) |

P ≤ 0.05 vs. vehicle.

P ≤ 0.05 vs. DDE (0.4 mg/kg)

To determine if the increase in fasting blood glucose following DDE (2.0 mg/kg) administration was due to altered levels of other metabolic hormones or adipokines, serum concentrations of insulin, glucagon, leptin, IL-6, TNFα, MCP-1, or resistin in the DDE or vehicle treated groups 7 days following cessation of DDE administration were measured. Administration of DDE (2.0 mg/kg) resulted in slight, but non-statistically significant elevations in fasting insulin, leptin, and resistin concentrations when compared to vehicle. There were no appreciable changes in serum concentrations of glucagon. Serum concentrations of the inflammatory adipokines IL-6, TNFα, and MCP-1 were below the limit of detection of the assay (data not shown).

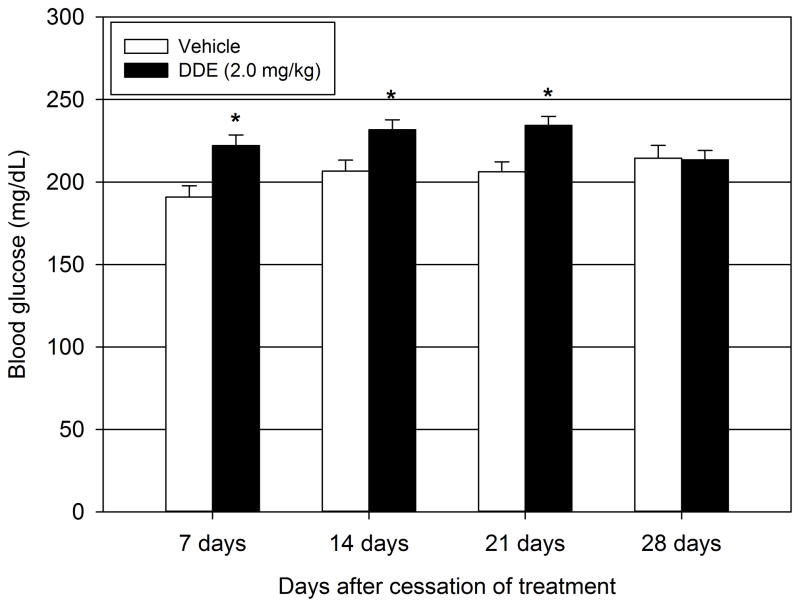

4.2 Duration of DDE-induced hyperglycemia

In order to assess the duration of the observed DDE-induced hyperglycemia, fasting blood glucose concentrations of DDE (2.0 mg/kg) exposed animals were measured every 7 days following cessation of DDE administration for a total of 28 days (Figure 1) and compared to time matched vehicle animals. At 7, 14, and 21 days following DDE cessation, the fasting blood glucose concentrations of DDE treated animals were significantly elevated when compared to corresponding vehicle treated animals (222.2 ± 6.5 vs. 190.9 ± 6.8 mg/dL, ~16.4% change vs. vehicle; 231.7 ± 6.0 vs. 206.6 ± 6.7 mg/dL, ~12.2% change vs. vehicle; and 234.3 ± 5.7 vs. 206.2 ± 6.1 mg/dL, ~13.6% change vs. vehicle respectively). At 28 days following the cessation of DDE administration, DDE treated animals had mean fasting blood glucose levels of 213.5 ± 5.8 mg/dL compared to 214.5 ± 7.7 mg/dL in the corresponding vehicle treated animals. Thus, at 28 days, there was no significant effect of DDE treatment compared to the corresponding time matched vehicle treated animals.

Figure 1.

Duration of DDE-induced fasting hyperglycemia. Animals were administered either vehicle or DDE (2.0 mg/kg) for 5 consecutive days then fasting blood glucose measurements were taken at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days following DDE administration. Data represent the mean ± SEM of each group (n=12–13/group). Statistically significant differences between DDE and the corresponding time-matched vehicle controls were determined with a Student’s t-test. *P ≤ 0.05 vs. vehicle.

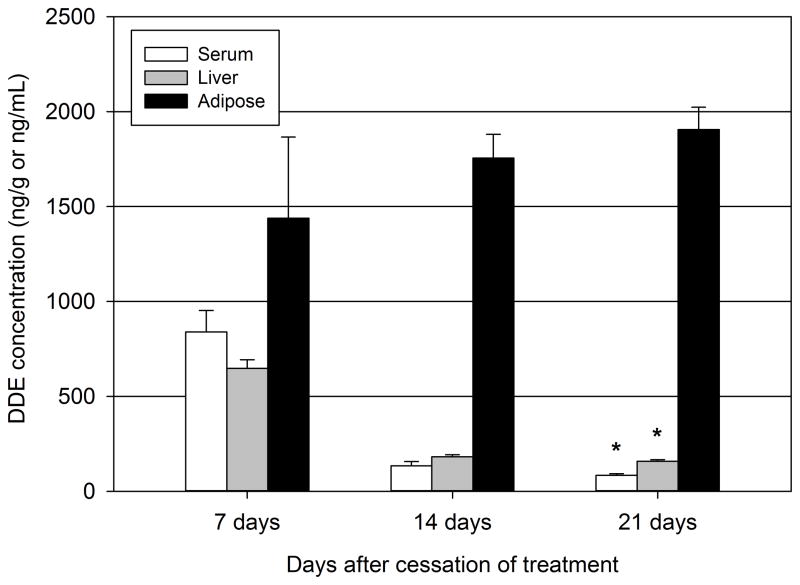

4.3 Time course of serum and tissue DDE concentrations

Following exposure to DDE, it has been reported that DDE bioaccumulates in lipid rich tissues, including the adipose tissue and liver. As to be expected, the adipose tissue concentrations of DDE rose steadily from day 7 through day 21 (Figure 2). The adipose concentrations were 1438.7 ± 427.7 ng/g at day 7, 1755.4 ± 125.5 ng/g at day 14, and 1906.2 ± 117.1 at day 21. In contrast to rising adipose tissue concentrations following DDE administration, the concentrations of DDE decreased in both serum and liver from day 7 to day 21. The liver concentrations of DDE were 647.6 ± 45.3 ng/g at day 7, 182.2 ± 10.3 ng/g at day 14, and 158.2 ± 9.9 at day 21. In the serum, DDE concentrations decreased from 839.3 ± 113.2 ng/ml at day 7 to 135.0 ± 22.0 ng/ml at day 14 and 83.8 ± 8.5 ng/ml at day 21. Twenty one days following cessation of DDE administration, both hepatic and serum concentrations of DDE decreased significantly compared to 7 days following cessation of DDE administration. It should be noted that DDE concentrations in vehicle treated animals were below the limit of detection in serum, liver, and adipose samples.

Figure 2.

Serum and tissue concentrations of DDE following dosing. Animals were administered either vehicle of DDE (2.0 mg/kg) for 5 consecutive days then serum, adipose tissue, and liver concentrations of DDE were measured via GC/MS 7, 14, or 21 days following DDE administration. Data represent 3–4 pooled samples of serum, adipose, or liver per group. Statistically significant differences between time points were determined with a one-way ANOVA on Ranks using a Dunn’s post hoc test with pairwise comparisons. * P ≤ 0.05 vs. 7 day group.

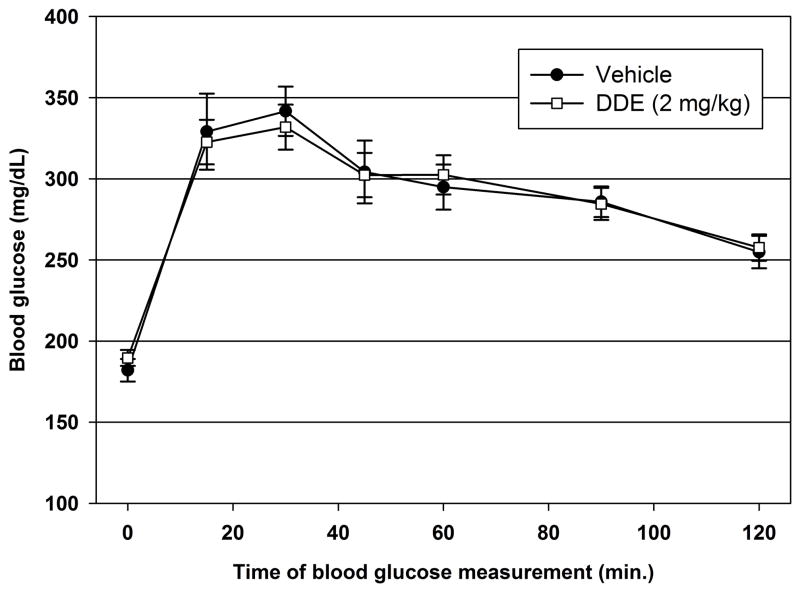

4.4 IPGTT following DDE exposure

To assess the effect of DDE administration on systemic glucose disposal, an IPGTT was performed on DDE (2.0 mg/kg) and vehicle treated animals 7 days following cessation of DDE administration. As illustrated in Figure 3, blood glucose concentrations rose to maximum concentrations 30 minutes following glucose administration and decreased steadily through the last blood glucose measurement at 120 minutes following glucose administration. There was no statistically significant difference in blood glucose concentrations between DDE and vehicle treated animals at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, or 120 minutes following glucose administration.

Figure 3.

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance testing 7 days following DDE administration. Seven days following vehicle or DDE (2.0 mg/kg) administration, animals (n=14–15/group) were fasted then subjected to an IPGTT. Data represent the mean ± SEM of each group at the indicated time point. Vehicle vs. DDE treatment comparisons for each time point were made using a Student’s t-test.

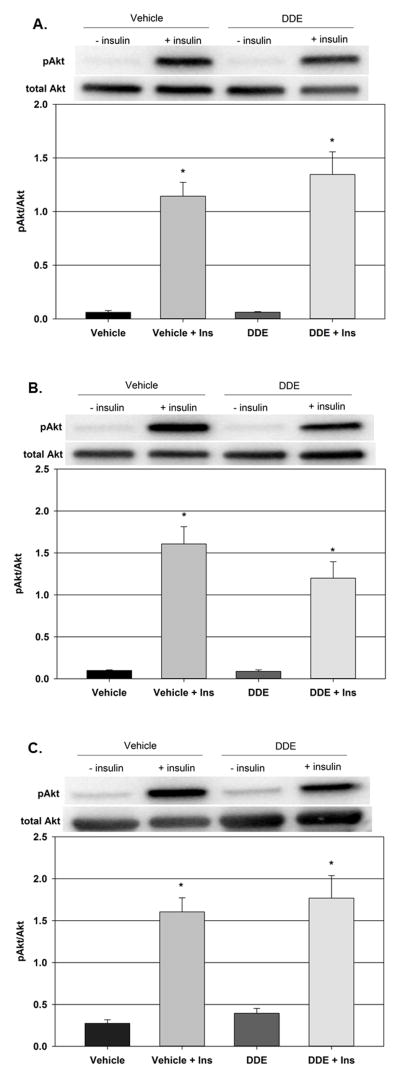

4.5 Akt phosphorylation in liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose following DDE exposure

The effect of DDE exposure on the insulin signaling pathway in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue was explored 7 days following cessation of DDE exposure. Administration of insulin to vehicle treated animals resulted in a significant increase in the hepatic pAkt/Akt ratio from 0.061 ± 0.02 in the vehicle only group to 1.144 ± 0.13 in the vehicle plus insulin group (Figure 4A). A similar effect was observed following insulin administration to DDE treated animals. Following insulin stimulation, the hepatic pAkt/Akt ratio increased significantly from 0.062 ± 0.01 in the DDE only group to 1.346 ± 0.21 in the DDE plus insulin group. There was no statistically significant difference in the pAkt/Akt ratios between the vehicle plus insulin and the DDE plus insulin groups.

Figure 4.

Effect of DDE administration on insulin signaling in liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. Animals were administered either vehicle or DDE (2.0 mg/kg) then allowed to rest for 7 days prior to fasting and intraperitoneal administration of insulin (10 U/kg) or saline vehicle. Phospho-Akt and total Akt were determined in the liver (Fig. 4A), gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 4B), and adipose tissue (Fig. 4C) and expressed as the pAkt/Akt ratio. Representative western blots are shown above each graph. Data represent the mean ± SEM of each group (n=5/group). Statistically significant differences were determined with a one-way ANOVA using a Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons. * P ≤ 0.05 vs. vehicle plus saline.

As with the hepatic pAkt/Akt ratio following insulin stimulation in vehicle and DDE treated animals, the pAkt/Akt ratios in the tissues primarily responsible for insulin induced glucose disposal, the skeletal muscle (Figure 4B) and adipose tissue (Figure 4C), were not significantly altered by DDE exposure. Administration of insulin to vehicle treated animals significantly increased the gastrocnemius pAkt/Akt ratio from 0.098 ± 0.01 in the vehicle only group to 1.607 ± 0.21 in the vehicle plus insulin group and the adipose pAkt/Akt ratio from 0.275 ± 0.04 in the vehicle only group to 1.604 ± 0.17 in the vehicle plus insulin group. Following insulin stimulation in the DDE treated animals, the gastrocnemius pAkt/Akt ratio went from 0.088 ± 0.02 in the DDE only group to 1.199 ± 0.20 in the DDE plus insulin group and the adipose pAkt/Akt ratio from 0.394 ± 0.06 in the DDE only group to 1.770 ± 0.27 in the DDE plus insulin group. There was no statistically significant difference in the pAkt/Akt ratios between the vehicle or DDE plus insulin groups. It should be noted that β-actin was used as a loading control for each group in liver, gastrocnemius, and adipose immunoblots. There were no significant differences in β-actin immunoreactivity between groups (data not shown).

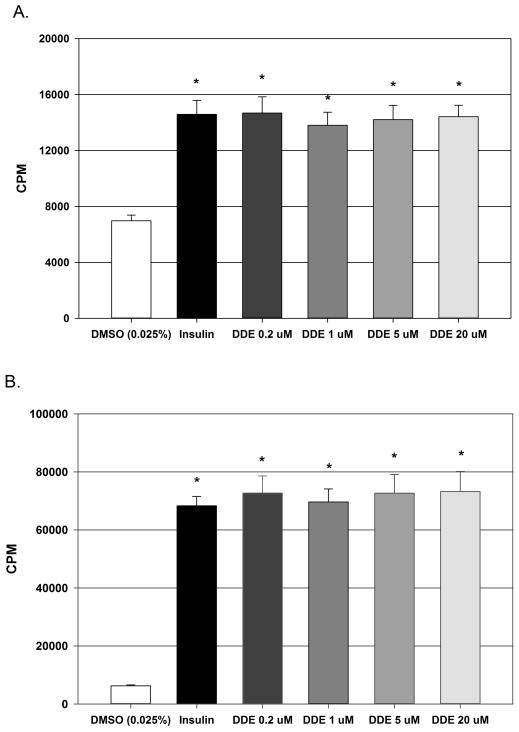

4.6 Effect of DDE exposure on insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in vitro

The effect of DDE exposure on glucose uptake in L6 myotubules and 3T3-L1 adipocytes to determine if direct exposure decreases responsiveness in the two main cell types responsible for insulin stimulated glucose uptake. As anticipated, insulin (100 nM) stimulation resulted in a robust and significant increase in [H3] 2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake in both cell types. In L6 myotubules (Figure 5A), radiolabelled glucose uptake increased approximately 2.1 fold from 6985.0 ± 401.6 CPM in vehicle controls to 14581.5 ± 1008.8 CPM following insulin stimulation. In 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Figure 5B), radiolabelled glucose uptake increased approximately 10.9 fold from 6247.6 ± 315.0 CPM in vehicle controls to 68289.8 ± 3244.0 CPM following insulin stimulation. Exposure to DDE (0.2, 1.0, 5.0, 20.0 μM) for 24 hours prior to insulin exposure had no significant effect on insulin stimulated glucose uptake in either L6 myotubules or 3T3-L1 adipocytes when compared to the insulin stimulated, vehicle treated cells.

Figure 5.

Effect of DDE exposure on insulin stimulated glucose uptake in L6 myotubules and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. The direct effect of DDE exposure on insulin stimulated glucose uptake in L6 myotubules (Fig. 5A) and in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (Fig. 5B). Data are expressed as counts of radiolabeled glucose per minute and represent the mean ± SEM of each group (n=8/group). Statistically significant differences were determined with a one-way ANOVA using a Dunnett’s post hoc test for comparisons vs. vehicle (DMSO). * P ≤ 0.05 vs. vehicle.

5. Discussion

In the present study we determined the effect of subacute exposure to DDE on glucose homeostasis using both in vivo and in vitro models. Exposure to DDE (2.0 mg/kg) induced mild to moderate yet statistically significant fasting hyperglycemia in male C57BL/JH mice that lasted between 21 and 28 days following the termination of DDE exposure. The degree of fasting hyperglycemia produced in the current studies is reminiscent of a prediabetic state in humans (≤ 25% change in fasting glucose) which is usually associated with marked fasting hyperinsulinemia (DeFronzo 1997, 2004). Interestingly, the current fasting hyperglycemia was not accompanied by a significant fasting hyperinsulinemia and did not appear to be caused by altered glucose disposal or by disruption of insulin signaling in key tissues involved in the pathogenesis of T2D, the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. These in vivo data are corroborated by our in vitro data examining the effect of DDE exposure on radiolabeled glucose uptake in the two cell types responsible for systemic glucose disposal, the skeletal muscle myotubule and the mature adipocyte.

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the role of exposure to environmental contaminants in the pathogenesis of T2D. Although the organochlorine compounds have been positively associated with increased incidence of diabetes and insulin resistance, these associations have primarily been based on retrospective epidemiological studies and do not represent a cause and effect relationship as previously mentioned. For our current studies, we choose to use DDE as a representative organochlorine compound due to the positive associations with diabetes, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome from analysis of NHANES data as well as increased diabetes incidence in Great Lakes sports fish consumers (Lee et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2006; Turyk et al. 2009a; Turyk et al. 2009b). In addition, our previous in vitro studies examining the effect of DDE on adipocyte function suggest that DDE may promote adipocyte dysfunction that may lead to insulin resistance and T2D (Howell and Mangum 2011).

Our current in vivo data demonstrate that subacute exposure to DDE for 5 days does indeed cause fasting hyperglycemia that persists for 21 days following discontinuation of DDE exposure. Interestingly, the DDE-induced hyperglycemia was consistently in the range of a 12–16% increase from vehicle control values over the 21 day period. Although this change represents a mild/moderate percentage increase, it is comparable to the percentage increases previously reported following high fat feeding, a well-documented method to induce insulin resistance in C57Bl/6 mice (Andrikopoulos et al. 2008; Gregoire et al. 2002; Rossmeisl et al. 2003). Andrikopoulous et al. (2008) demonstrated a 15.5% increase in fasting glucose coupled with a 77.8% increase in fasting insulin and an elevated glucose tolerance test following 8 weeks of high fat feeding while Gregoire et al. (2002) demonstrated a 14.5% and Rossmeil et al. (2003) observed a 12.8% increase in fasting glucose in conjunction with 390% and 156% changes in fasting insulin levels, respectively. Taken together, the hyperglycemia produced in these studies following high fat feeding are mild to moderate and are comparable to those achieved following DDE exposure in the present study. However, the hyperglycemia produced by high fat feeding as well as genetically induced hyperglycemia as observed in db/db animals is typically preceded by insulin resistance as indicated by significantly elevated fasting insulin levels and/or elevated IPGTT testing (Gregoire et al. 2002; Kodama et al. 1994). This is illustrated by the studies by Gregoire et al. (2002) where fasting insulin levels are 124% higher than baseline following 11 days of high fat feeding while blood glucose levels are unchanged. It should be noted that basal fasting glucose readings in the present studies did fluctuate, however the animals in the present study were only fasted for 6 hours and not overnight (12–16 hour fast). This relatively short duration of fasting is less likely to deplete liver glycogen content and will thus result in a higher baseline and inevitably more variability in basal levels due to possible liberation of glycogen stores (Ayala et al. 2010). While the fasting hyperglycemia may be moderate, these studies are the first to demonstrate that subacute exposure to DDE alone is sufficient to induce significant fasting hyperglycemia in an experimental setting.

Recent studies by others have demonstrated that a diet supplemented with salmon oil containing a mixture of POPs, including DDE, resulted in hyperglycemia associated with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia in rodent models of T2D (Ibrahim et al. 2011; Ruzzin et al. 2010). Ruzzin et al. (2010) demonstrated that treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes with a mixture of DDT like compounds promoted insulin resistance characterized by decreased insulin stimulated glucose uptake and Ibrahim et al. (2011) demonstrated that treatment of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes with low concentrations of DDE promoted adipogenesis when used in conjunction with a suboptimal differentiation cocktail. These studies by Ibrahim et al. (2011) are some of the first examining the effect of DDE alone. Our current studies examining the effect of DDE alone on glucose uptake in both mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes and L6 myotubules utilize comparable concentrations of DDE to those used by Ibrahim et al. However, we did not observe an effect of DDE on glucose uptake in either cell line tested. Given that adipogenesis and glucose uptake are two independent cellular processes, this discrepancy is not unexpected. With regards to the observed differences of DDE exposure on glucose uptake in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes, Ruzzin et al. observed decreases in insulin stimulated glucose uptake following 48 hours of exposure of 3T3-L1 adipocytes to a mixture of DDTs in the nanomolar range. Our studies utilized the primary metabolite of DDT, DDE, alone and we did not see an effect from exposure to 0.2 – 20 μM for 24 hours. Therefore, the observed differences between the two studies may arise from a mixtures effect or an effect of exposure duration.

In addition to examining the duration of DDE induced hyperglycemia, we measured the concentrations of DDE in the serum, liver, and adipose tissue at 7, 14, and 21 days following cessation of DDE administration. DDE has an approximate 400–450:1 adipose to blood partition coefficient in the rodent, thus we anticipated that the primary depot of DDE would be the adipose tissue (Muhlebach et al. 1991; You et al. 1999). The current data do indeed indicate that adipose tissue concentrations increase from 1438.7 ng/g at 7 days to 1906.2 ng/g at 21 days following DDE administration and these data support the role of adipose as the primary storage depot of DDE. While the adipose tissue is the primary storage depot of DDE and other OC compounds, the liver has a reported 6–7:1 liver to blood partition coefficient in the rodent (Muhlebach et al. 1991; You et al. 1999). Therefore, we anticipated that the liver concentrations of DDE may fall slightly following discontinuation of administration but would level off prior to those in the serum. Indeed, hepatic DDE concentrations fell from 647.6 ng/g at 7 days to 158.2 ng/g at 21 days following DDE administration, a change of approximately 4.1 fold. Serum concentrations of DDE fell from 839.3 ng/ml at 7 days to 83.8 ng/ml at 21 days following DDE administration, a change of approximately 7.6 fold. These data illustrate that the decrease in serum DDE was greater than the decrease in hepatic DDE content. It is likely that the increase in adipose tissue DDE is, in part, a product of redistribution of DDE from the liver, serum, and other potential depots into the adipose tissue. However, it should be noted that excretion of DDE was not measured in the present studies so the contribution of excretion to systemic DDE flux cannot be determined based on the current data.

While it is difficult to determine the relationship of the observed adipose concentrations to those in humans due to the limited number of studies analyzing human adipose tissue levels in the U.S., we can compare serum concentrations of DDE from the present study to a large, human study population in the U.S. In the present study, serum concentrations of DDE were 83.8 ppb (whole serum) at 21 days following cessation of DDE administration. This value is roughly 6.9 fold higher than 12.1 ppb (whole serum), the 95th percentile of total subjects in the 2003–2004 NHANES study, and roughly 3.7 fold higher than 22.9 ppb (whole serum), the 95th percentile of the Mexican American group in the same study (CDC 2009). Thus, at a time point where fasting hyperglycemia is observed in the present model, the serum DDE concentrations are approximately 6.9 fold greater or less than those observed in the high exposure, human population of the U.S. A notable difference between serum levels obtained in the NHANES studies compared to the present study is that we utilized a subacute, 5 day exposure to achieve these serum concentrations of DDE where the measurements obtained in the NHANES study represent a chronic, low level exposure over time that results in the measured serum concentrations.

To determine if the observed DDE-induced hyperglycemia was a product of decreased glucose disposal due to insulin resistance, we performed glucose tolerance testing and assessed the patency of the insulin signaling pathway following an insulin challenge in addition to using in vitro models of both skeletal muscle myotubules and adipocytes to determine the effect of DDE exposure on insulin stimulated glucose uptake. Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests and insulin challenge experiments were performed 7 days following the termination of DDE exposure. These studies were conducted at the 7 day time point because at this time serum and liver DDE levels were elevated compared to 14 and 21 days following DDE cessation and fasting glucose levels were comparable to those at 14 and 21 days. Thus, if DDE was causing insulin resistance in liver and skeletal muscle, it should be evident at this time point due to elevated serum concentrations. A potential limitation to the current time point measurements is the possibility that hyperglycemia and/or insulin defects may have been greater immediately following cessation of DDE administration. However, the stress of repeated handling and gavage dosing may promote hyperglycemia due to catecholamine release and confound possible DDE effects. Therefore, a 7 day waiting period was utilized and when compared to vehicle controls, DDE treated animals did not display an increase in systemic glucose concentrations following i.p. glucose administration at any measured time point. Thus, based on our IPGTT results, there was no apparent DDE-induced defect in systemic glucose disposal that would promote the observed fasting hyperglycemia at 7 days following DDE exposure.

While our results from the IPGTT suggested that the insulin signaling pathway was intact and that insulin stimulated glucose uptake was unaffected by DDE exposure, these parameters were not directly measured by the IPGTT. Therefore, insulin challenge experiments were performed at the same time point as the IPGTT to determine if DDE exposure may alter insulin signaling in insulin sensitive tissues. The liver was chosen for analysis because the DDE induced fasting hyperglycemia may be a product of insulin resistant hepatic glucose production resulting from gluconeogenesis or glycogenolysis (DeFronzo 2004). The skeletal muscle and adipose tissue were chosen due to the fact that the skeletal muscle accounts for 80–85% and the adipose accounts for 10–15% of systemic insulin-induced glucose uptake (DeFronzo 2004). Serine phosphorylation of Akt and subsequent activation of Akt has been shown to be a key signaling intermediate in the insulin signaling cascade governing insulin induced decreases in hepatic gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis as well as insulin induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle (Cartee and Wojtaszewski 2007; Davis et al. 2010; Hajduch et al. 2001; Klip 2009; Rowland et al. 2011; Taniguchi et al. 2006). Western blot analysis of Akt phosphorylation in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue revealed that DDE exposure did not significantly alter insulin induced Akt phosphorylation at 7 days following DDE exposure. Given that insulin induced phosphorylation of Akt is a major upstream event prior to insertion of Glut4 into the plasma membrane and subsequent glucose uptake, these data indicate that insulin induced glucose uptake in the skeletal muscle and adipose should be intact. In contrast to the current data, Ibrahim et al. (2011) demonstrated that decreased insulin induced phosphorylation of Akt (~50% reduction in pAkt/Akt) is associated with decreased glucose uptake following POPs exposure and that this decreased Akt phosphorylation is associated with hyperinsulinemia and an elevated IPGTT which taken together are indicative of insulin resistance (Ibrahim et al. 2011). The studies by Ibrahim et al. (2011) coincide with the role of Akt in insulin signaling and diminished Akt function following the formation of insulin resistance. Decreased Akt activity and Akt phosphorylation by at least 30% in muscle has been noted in both human subjects and db/db mice while Akt phosphorylation decreased by ~69% in the adipose of db/db mice (Krook et al. 1998; Shao et al. 2000). Although phosphorylation of Akt in skeletal muscle was diminished by approximately 25% in the current studies, this was not statistically different compared to insulin stimulated controls. Given the lack of a DDE effect on fasting serum insulin and IPGTT, this decrease in Akt phosphorylation does not appear to be great enough to decrease Akt activity, result in insulin insensitivity, and decrease glucose uptake.

To determine if DDE exposure could directly decrease insulin stimulated glucose uptake in the two tissues that mediate the majority of systemic glucose disposal, the skeletal muscle myotubule and the mature adipocyte, we performed in vitro glucose uptake assays. Exposure to a DDE at concentrations that we previously determined to have an effect on fatty acid uptake and adipokine production in 3T3-L1 adipocytes had no significant effect on insulin stimulated glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 adipocytes or in L6 skeletal muscle myotubules (Howell and Mangum 2011). Taken together, our IPGTT, insulin challenge, and in vitro glucose uptake assay data suggest that the observed DDE induced hyperglycemia is not due to systemic insulin resistance.

In conclusion, the present data demonstrate that subacute exposure to DDE does promote a transient dysregulation of glucose homeostasis as indicated by prolonged mild to moderate fasting hyperglycemia following a 5 day exposure. The degree of fasting hyperglycemia produced in the current studies is reminiscent of a prediabetic state in humans but a prediabetic state is usually a chronic condition characterized by a mild to moderate hyperglycemia associated with marked fasting hyperinsulinemia as observed in both human and rodent studies. While the current studies did utilize a 5 day dosing paradigm and not a chronic repeated exposure, these data indicate that exposure to and resulting elevated serum concentrations of DDE may contribute to the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus. The present data suggest that the hyperglycemic effect of subacute DDE exposure is not a product of systemic insulin resistance 7 days following cessation of DDE exposure. However, further studies are needed to determine if chronic exposure to DDE, resulting in a steady state elevation of systemic DDE levels, alone will continue to produce defects in glucose homeostasis. In addition, given that exposure to DDE is likely to be concurrent with other OCs, studies examining if chronic exposure to DDE in combination with other OCs will exacerbate either diet or genetically induced diabetes are needed to substantiate exposure to this compound as a risk factor in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus.

DDE exposure produced hyperglycemia for up to 21 days in C57BL/6H mice

DDE did not alter IPGTT or insulin signaling in liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose

Serum levels of insulin, glucagon, and adipokines were unaltered following exposure

Insulin stimulated glucose uptake was not altered by DDE in vitro

Hepatic and serum DDE levels dropped significantly following exposure

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Shane Bennett, Mr. Alper Coban, and Mrs. Lauren Mangum for their assistance in performing the presently described animal experiments and routine animal monitoring. In addition, the authors would like to thank Dr. Amira Klip from The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada for the L6glut4myc myoblasts. The present work was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R15ES019742.

Abbreviations

- DDE

p,p′-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene

- DDT

p,p′-dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

- T2D

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- POPs

persistent organic pollutants

- OC

organochlorine compound

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- AAALAC

Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- ACE

accelerated solvent extractor

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

- HOMA-IR

homeostasis model assessment value for insulin resistance

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor alpha

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- MCP-1

monocyte/macrophage chemotractant protein 1

- i.p

intraperitoneal

- IPGTT

intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

- GC/MS

gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

7. Conflict of interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest by any authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature cited

- Andrikopoulos S, Blair AR, Deluca N, Fam BC, Proietto J. Evaluating the glucose tolerance test in mice. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;295:E1323–1332. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90617.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala JE, Samuel VT, Morton GJ, Obici S, Croniger CM, Shulman GI, Wasserman DH, McGuinness OP. Standard operating procedures for describing and performing metabolic tests of glucose homeostasis in mice. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:525–534. doi: 10.1242/dmm.006239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biro FM, Wien M. Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1499S–1505S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28701B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartee GD, Wojtaszewski JF. Role of Akt substrate of 160 kDa in insulin-stimulated and contraction-stimulated glucose transport. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32:557–566. doi: 10.1139/H07-026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC; C.f.D.C.a.P. Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. Atlanta: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CDC; C.f.D.C.a.P. Department of Health and Human Services, editor. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RC, Castellani LW, Hosseini M, Ben-Zeev O, Mao HZ, Weinstein MM, Jung DY, Jun JY, Kim JK, Lusis AJ, Peterfy M. Early hepatic insulin resistance precedes the onset of diabetes in obese C57BLKS-db/db mice. Diabetes. 2010;59:1616–1625. doi: 10.2337/db09-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance: a multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and atherosclerosis. Neth J Med. 1997;50:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(97)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFronzo RA. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med Clin North Am. 2004;88:787–835. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. Jama. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregoire FM, Zhang Q, Smith SJ, Tong C, Ross D, Lopez H, West DB. Diet-induced obesity and hepatic gene expression alterations in C57BL/6J and ICAM-1-deficient mice. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2002;282:E703–713. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00072.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajduch E, Litherland GJ, Hundal HS. Protein kinase B (PKB/Akt)--a key regulator of glucose transport? FEBS Lett. 2001;492:199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell G, 3rd, Mangum L. Exposure to bioaccumulative organochlorine compounds alters adipogenesis, fatty acid uptake, and adipokine production in NIH3T3-L1 cells. Toxicology in vitro: an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2011;25:394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MM, Fjaere E, Lock EJ, Naville D, Amlund H, Meugnier E, Le Magueresse Battistoni B, Froyland L, Madsen L, Jessen N, Lund S, Vidal H, Ruzzin J. Chronic consumption of farmed salmon containing persistent organic pollutants causes insulin resistance and obesity in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern PA, Said S, Jackson WG, Jr, Michalek JE. Insulin sensitivity following agent orange exposure in Vietnam veterans with high blood levels of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4665–4672. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klip A. The many ways to regulate glucose transporter 4. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2009;34:481–487. doi: 10.1139/H09-047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama H, Fujita M, Yamaguchi I. Development of hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance in conscious genetically diabetic (C57BL/KsJ-db/db) mice. Diabetologia. 1994;37:739–744. doi: 10.1007/BF00404329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozma L, Baltensperger K, Klarlund J, Porras A, Santos E, Czech MP. The ras signaling pathway mimics insulin action on glucose transporter translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:4460–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krook A, Roth RA, Jiang XJ, Zierath JR, Wallberg-Henriksson H. Insulin-stimulated Akt kinase activity is reduced in skeletal muscle from NIDDM subjects. Diabetes. 1998;47:1281–1286. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Lee IK, Jin SH, Steffes M, Jacobs DR., Jr Association between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and insulin resistance among nondiabetic adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:622–628. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Lee IK, Song K, Steffes M, Toscano W, Baker BA, Jacobs DR., Jr A strong dose-response relation between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and diabetes: results from the National Health and Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1638–1644. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Steffes MW, Sjodin A, Jones RS, Needham LL, Jacobs DR., Jr Low dose organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls predict obesity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance among people free of diabetes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PC, Matsumura F. Differential effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on the “adipose- type” and “brain-type” glucose transporters in mice. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalek JE, Pavuk M. Diabetes and cancer in veterans of Operation Ranch Hand after adjustment for calendar period, days of spraying, and time spent in Southeast Asia. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:330–340. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31815f889b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlebach S, Moor MJ, Wyss PA, Bickel MH. Kinetics of distribution and elimination of DDE in rats. Xenobiotica. 1991;21:111–120. doi: 10.3109/00498259109039455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DG, Jr, Wong LY, Turner WE, Caudill SP, Dipietro ES, McClure PC, Cash TP, Osterloh JD, Pirkle JL, Sampson EJ, Needham LL. Levels in the U.S. population of those persistent organic pollutants (2003–2004) included in the Stockholm Convention or in other long range transboundary air pollution agreements. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:1211–1218. doi: 10.1021/es801966w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rignell-Hydbom A, Lidfeldt J, Kiviranta H, Rantakokko P, Samsioe G, Agardh CD, Rylander L. Exposure to p,p′-DDE: a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7503. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rignell-Hydbom A, Rylander L, Hagmar L. Exposure to persistent organochlorine pollutants and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2007;26:447–452. doi: 10.1177/0960327107076886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossmeisl M, Rim JS, Koza RA, Kozak LP. Variation in type 2 diabetes--related traits in mouse strains susceptible to diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2003;52:1958–1966. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.8.1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland AF, Fazakerley DJ, James DE. Mapping insulin/GLUT4 circuitry. Traffic. 2011;12:672–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzzin J, Petersen R, Meugnier E, Madsen L, Lock EJ, Lillefosse H, Ma T, Pesenti S, Sonne SB, Marstrand TT, Malde MK, Du ZY, Chavey C, Fajas L, Lundebye AK, Brand CL, Vidal H, Kristiansen K, Froyland L. Persistent organic pollutant exposure leads to insulin resistance syndrome. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:465–471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rylander L, Rignell-Hydbom A, Hagmar L. A cross-sectional study of the association between persistent organochlorine pollutants and diabetes. Environ Health. 2005;4:28. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-4-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Yamashita H, Qiao L, Friedman JE. Decreased Akt kinase activity and insulin resistance in C57BL/KsJ-Leprdb/db mice. The Journal of endocrinology. 2000;167:107–115. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1670107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi CM, Kondo T, Sajan M, Luo J, Bronson R, Asano T, Farese R, Cantley LC, Kahn CR. Divergent regulation of hepatic glucose and lipid metabolism by phosphoinositide 3-kinase via Akt and PKClambda/zeta. Cell Metab. 2006;3:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turyk M, Anderson H, Knobeloch L, Imm P, Persky V. Organochlorine exposure and incidence of diabetes in a cohort of Great Lakes sport fish consumers. Environ Health Perspect. 2009a;117:1076–1082. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turyk M, Anderson HA, Knobeloch L, Imm P, Persky VW. Prevalence of diabetes and body burdens of polychlorinated biphenyls, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and p,p′-diphenyldichloroethene in Great Lakes sport fish consumers. Chemosphere. 2009b;75:674–679. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueyama A, Yaworsky KL, Wang Q, Ebina Y, Klip A. GLUT-4myc ectopic expression in L6 myoblasts generates a GLUT-4-specific pool conferring insulin sensitivity. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:E572–578. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.277.3.E572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Method 3545A: Pressurized Fluid Extraction (PFE) United States Environmental Protection Agency; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You L, Gazi E, Archibeque-Engle S, Casanova M, Conolly RB, Heck HA. Transplacental and lactational transfer of p,p′-DDE in Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;157:134–144. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]