Abstract

Clostridium difficile infections in children are increasing. In this cohort study, we enrolled 62 children with diarrhea and C. difficile. We performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays to detect viral agents of gastroenteritis and quantify C. difficile burden. Fifteen (24%) children diagnosed with C. difficile infection had a concomitant viral co-infection. These patients tended to be younger and had a higher C. difficile bacterial burden than children with no viral co-infections (median difference=565 957cfu/mL p=0.011), but were clinically indistinguishable. The contribution of viral co-infection to C. difficile disease in children warrants future investigation.

Keywords: C. difficile, children, viral gastroenteritis, norovirus

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium difficile is the most common cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea in adults in the United States (1), and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in adults (2, 3), and children (4, 5). Rates of C. difficile infection (CDI) in hospitalized children are increasing (6-9). However, C. difficile and its toxins can be detected in up to 70% of asymptomatic young children (10-12). Rates of positive C. difficile assays are similar in stools of asymptomatic young children and children with diarrhea (13, 14). Therefore, guidelines warn physicians that “detection of C. difficile toxin cannot be assumed to be the causative agent for diarrhea in children before adolescence, particularly young children” (15, 16). Bacterial fecal cultures are often performed in a child with diarrhea and concern for C. difficile; however, with the absence of easily available viral studies, rates of viral co-infections are still unknown and the relationship between C. difficile colonization, C. difficile infection, and viral infections is unknown. Previous case reports suggest that viral gastrointestinal infections may be common in children with CDI (17, 18), as do prospective studies assessing etiologies of diarrhea in children (13, 19). Similarly, in adults, C. difficile has been detected with increased frequency during confirmed viral gastroenteritis outbreaks (20, 21). The contribution of viral co-infections to C. difficile disease severity and outcome has not been addressed.

We conducted this cohort study to identify the rates of viral co-infections in children diagnosed with CDI, and recognize any potential differentiating clinical features or differences in outcomes between children with and without viral co-infections. We hypothesized that viral co-infections are common in children with CDI and are associated with a more severe presentation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

We conducted this prospective cohort study in St Louis Children's Hospital (SLCH), St. Louis, MO, and obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Washington University School of Medicine. We approached all children with diarrhea and a positive C. difficile polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the microbiology laboratory from 1 July 2011 to 5 July 2012, and obtained written informed consent from their caregivers.

CLINICAL DATA

We collected demographic and clinical data regarding the diarrhea at time of diagnosis (onset, number of bowel movements per day, stool consistency according to the Bristol stool chart (22), pain (on a scale of 1-10), nausea/vomiting, and laboratory findings). We also recoded outcomes including time to diarrhea resolution, diarrhea persistence at 5days of therapy, intensive care unit admissions, severe disease (defined as white blood cell count (WBC)≥15000 cells/μL or serum creatinine≥1.5 times baseline (23)), severe complicated (defined as hypotension, shock, ileus or megacolon (23)), and documented recurrence on all our patients.

STOOL COLLECTION

Laboratory personnel immediately stored stool samples from children with positive C. difficile PCR at −80°C.

LABORATORY ASSAYS performed on all samples

Nucleic Acid Extraction

We used the NucliSENS® EasyMAG™ automated system software 1.0.2 specific A protocol (bioMérieux, Marcy L'Etoile, France), to extract total nucleic acid according to the manufacturer's instructions. 200 μL of stool eluate was added to 2 mL of lysis buffer, followed by 100 μL of magnetic silica for a final volume of 110 μL of nucleic acid extract.

Polymerase Chain Reactions

All PCRs were performed using 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Viral Gastroenteritis PCR

We performed monoplex TaqMan real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reactions (RT-PCR) for: norovirus genogroups 1 and 2, sapovirus, astrovirus, adenovirus group F, and rotavirus. Primers, probes and PCR conditions were based on those published previously by Grant et al. (24) and Freeman et al. (25). Positive and negative controls were included in each run.

Quantitative tcdB DNA PCR

We performed SYBR Green-based real-time tcdB PCR as described by Wroblewski et al (26), with slight modification (27). We validated the linearity of the tcdB PCR using tcdB cloned into plasmid pHIS1525 (MoBiTec Inc., Boca Raton, FL) as a DNA standard. Linear regression allowed calculations of C. difficile concentration (cfu/mL) = 7000×10(CT-32.4)/−5.2 (data not shown).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We used non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare the two groups, and Chi-square test and, when appropriate, Fisher's exact test, for categorical data comparison. We used log rank test to compare time to diarrhea resolution in cases with viral co-infections and those without. A two-tailed p value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Of 74 patients identified with a positive C. difficile PCR, seven had no available stools and families of two were unreachable. Of the 65 patients we approached, 64 were consented and enrolled. Two children were excluded because our tcdB PCR was negative while the microbiology laboratory's C. difficile PCR was positive. Our final cohort included 62 children.

Subjects had a median age of 10.3y (IQR= 3.3-14.9). Age distribution included one (2%) infant <1y, 11 (18%) patients 1-3y, and 50 (81%) patients >3y of age 28. 28 (45%) patients were males. 37 (60%) were on immunosuppressives at the time of diagnosis (27 (43%) were on steroids, and 35 (56%) on chemotherapeutic agents). 57 (92%) had received antibiotics within the 90days prior to admission. 24 (39%) patients had a malignancy, solid organ transplantation, or a bone marrow transplantation, 8 (13%) had a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Enrollment per season was as follows: 14 children in the summer, 18 children in the fall, 17 children in the winter, and 13 children in the spring. 39 (63%) children had a concomitant fecal bacterial culture performed.

Of the 62 children with positive C. difficile testing, 55 (89%) were initially treated for CDI and 7 (11%) were not. Age did not differ between children who received CDI therapy and those who did not (median 10.2y compared to 10.7y (p=0.81)). Median time from diarrhea onset to diagnosis was 3d.

We found a virus capable of causing gastroenteritis in 15 (24%) children. Norovirus genogroup 2 was the most common virus encountered concomitantly with C. difficile (10 (16%) children), followed by sapovirus (3 (5%) children). Norovirus genogroup 1 and astrovirus were identified in one case each. We did not find any rotavirus or enteric adenovirus in our cohort. Two (29%) of the seven untreated children had a concomitant viral co-infection.

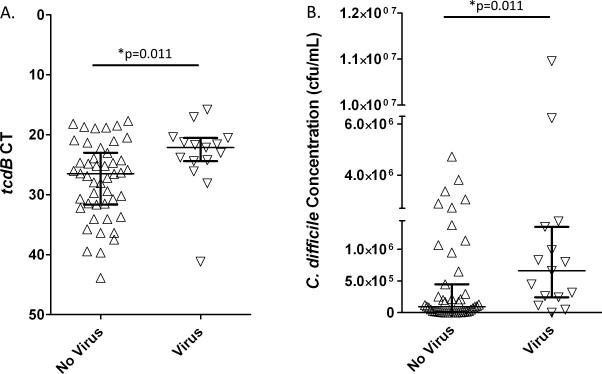

We attempted to identify clinical features differentiating children with C. difficile and viral co-infections from those without viral co-infections. The two groups of patients were clinically indistinguishable, and their median time to diarrhea resolution on CDI therapy was 3 days, regardless of the viral co-infection status (Table). We found no differences in severity or outcomes between the two groups (Table). C. difficile bacterial burden was significantly higher in patients with viral co-infections (C. difficile concentration median difference=565 957 cfu/mL, p=0.011) (Figure).

TABLE.

Characteristics of 16 patients with a positive C. difficile assay and viral co-infections compared to 49 patients with no viral co-infections.

| C. difficile +, virus + n=15 | C. difficile +, no virus n=47 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 3.9 (2.3-12.4) | 10.7 (5.5-15.7) | 0.13* |

| Male, n (%) | 4 (37) | 24 (51) | 0.14† |

| Number of stools/day,¶ median (IQR) | 6 (4-8) | 5 (3-10) | 0.75* |

| Bristol score,¶ median (IQR) | 7 (7-7) | 7 (6-7) | 0.11* |

| Pain on a scale of 1-10,¶ median (IQR) | 5 (3-7) | 5 (2-8) | 0.94* |

| Maximum temperature in °Celsius, median (IQR) | 37.2 (37-37.6) | 37.4 (37-38.2) | 0.28* |

| Nausea/ vomiting, n (%) | 11 (73) | 27 (57) | 0.36† |

| WBC in 103 cells/μL, median (IQR) | 4.3 (1.2-10.6) | 5.7 (0.7-13.9) | 0.93* |

| Serum creatinine ≥1.5 times baseline, n(%) | 1 (7) | 8 (17) | 0.43† |

| Severe (WBC ≥ 15000 cells/μL or creatinine ≥ 1.5 times premorbid level) n(%) | 2 (13) | 4 (8) | 0.65† |

| Severe complicated (hypotension, shock, ileus or megacolon) n(%) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 1.0† |

| Treated for CDI, n (%) | 13 (81) | 42 (86) | 0.7† |

| Treated with vancomycin, n (%) | 4/13 (31) | 19/42 (45) | 0.52† |

| Time to diarrhea resolution in days, median (IQR) | 3 (3-6) | 3 (2-9) | 0.56‡ |

| Diarrhea persistence at 5days of therapy, n (%) | 6/12 (50) | 16/42 (38) | 0.52† |

| Intensive care unit admission, n (%) | 1 (7) | 8 (17) | 0.43† |

| Documented recurrence, n (%) | 1 (7) | 8 (17) | 0.43† |

| C. difficile concentration (cfu/mL), median (IQR) | 661291 (243223-1352208) | 95334 (9775,448486) | 0.011* |

IQR= interquartile range; CDI= Clostridium difficile infection; cfu= colony forming unit; WBC= white blood cell count

p value of a two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test

p value of Fisher's exact test

p value of the log rank test

On the day of diagnosis

FIGURE. Bacterial burden in 15 children with C. difficile and viral co-infections compared to 47 children with C. difficile and no viral co-infections.

A. Children with C. difficile and no viral co-infection (upward triangle) had a higher tcdB cycle threshold (CT) value than those with viral co-infections (downward triangle).

B. Children with C. difficile and no viral co-infection (upward triangle) had a lower C. difficile concentration than those with viral co-infections (downward triangle).

Each triangle represents an individual patient's value. Bars represent medians and interquartile ranges. *p value of the two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Although patients with C. difficile and viral co-infectious tended to be younger (median 3.9y compared to 10.7y, p=0.13), the high rate of viral co-infections was not specific to the younger age-group. When we excluded children <3y of age, traditionally described to have high levels of C. difficile colonization, 11 (22%) of 50 older children had a viral co-infection. Treating physicians were unlikely to differentiate between the two groups: 13 (87%) cases with viral co-infections were treated for CDI, compared to 42 (89%) cases with no viral co-infections. When patients who did not receive therapy were excluded, 13 (24%) of the 55 patients diagnosed and treated for CDI had a viral co-infection.

DISCUSSION

Though concomitant C. difficile and viral infections has been described previously (18, 19), no study has systematically investigated the rate of viral co-infections in CDI or compared their clinical presentation to children without viral co-infections. In our cohort, we found that 24% of children diagnosed with CDI have a concomitant viral gastroenteritis. This finding raises questions regarding the pathogenicity of C. difficile in children and the role viruses play in this setting. Viruses may predispose children to develop CDI or vice-versa, or there may be features of the host, such as state of the mucosal immune response or the intestinal microbiome, that predispose to both infections.

The current study confirms our previous findings that C. difficile bacterial burden does not correlate with clinical presentations or outcome measures in CDI (27). Children with viral co-infections had higher fecal C. difficile concentrations than those without co-infections; however, their clinical illnesses were similar. It has been postulated that viral gastroenteritis exacerbates the effects of C. difficile because of alteration of intestinal epithelial homeostasis (18). The observation of higher C. difficile fecal bacterial burden in children with viral co-infection suggests that viruses may create favorable conditions for C. difficile to multiply and potentially cause disease, possibly through perturbation of the intestinal microbiota or innate host defenses. Indeed, viral gastroenteritis is associated with decreased intestinal microbial diversity and a shift in relative abundance of bacterial phyla, similar to that seen with antibiotic exposure, the major risk factor for C. difficile infection (28). Alternatively, virus-induced changes in stool composition may occur affecting the tcdB PCR results, thus increasing the rate of C. difficile detection, and leading to an increased diagnosis of CDI in children with viral gastroenteritis.

Nosocomial outbreaks of norovirus originally attributed to C. difficile raised the possibility that C. difficile may be a colonizer or an innocent bystander (20, 21). It is possible that children with viral gastroenteritis are misdiagnosed with CDI and do not in fact require CDI therapy. An association between viral agents of gastroenteritis and CDI rather than a misdiagnosis of CDI in the setting of viral gastroenteritis may also be possible. An alternate possibility is that asymptomatic C. difficile carriers are more likely to develop viral gastroenteritis. A longitudinal case control study following children colonized with C. difficile for acquisition of viral gastroenteritis may address this question.

A limitation of our study is the lack of a longitudinal study design. Such a study following children prior to C. difficile acquisition would allow delineation of the timing of C. difficile and viral acquisition in relation to symptom onset. We cannot therefore generate a clear cause-and-effect hypothesis. It is possible that viral gastroenteritis leads to a misdiagnosis and overtreatment of CDI. It is also possible that viral gastroenteritis may predispose children colonized with C. difficile toward the development of symptomatic C. difficile infection.

In summary, we found that rates of viral co-infections in stools of children diagnosed and treated for C. difficile infections are high, and are associated with an elevated C. difficile fecal bacterial burden, suggesting an interaction between viral agents of gastroenteritis and C. difficile. With the development of new multiplexed nucleic acid-based technologies for diagnosis of gastroenteritis, dual identification of C. difficile and a viral pathogen is likely to be a common finding. Management of these children will be challenging. Identification of host-derived biomarkers that are specific for C. difficile may help clarify which of these children are likely to benefit from C. difficile targeted therapy. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the role of viral infection on the progression from asymptomatic colonization to C. difficile-associated disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Lindsay Grant Ph.D. MPH and Jan Vinje Ph.D. for sharing detailed PCR conditions for the viral agents of gastroenteritis, and Carey-Ann Burnham Ph.D. for providing advice on tcdB PCR methods. We also thank the St Louis Children's Hospital Microbiology laboratory for the help with stool samples collection, and children participating in our study and their families.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a Washington University-Pfizer Biomedical Agreement and the Midwest Regional Centers for Excellence for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Disease Research (U54-AI057160) for D.B.H. P.I.T. is supported by the Melvin E. Carnahan Professorship in Pediatrics, Washington University Digestive Diseases Research Core Center, and Biobank grant number 5P30 DK052574.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sammons JS, Toltzis P, Zaoutis TE. Clostridium difficile Infection in Children. JAMA Pediatr. 2013:1–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubberke ER, Reske KA, Yan Y, et al. Clostridium difficile--associated disease in a setting of endemicity: identification of novel risk factors. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;45(12):1543–9. doi: 10.1086/523582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DuPont HL, Garey K, Caeiro JP, et al. New advances in Clostridium difficile infection: changing epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment and control. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21(5):500–7. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32830f9397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nylund CM, Goudie A, Garza JM, et al. Clostridium difficile infection in hospitalized children in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(5):451–7. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MB. Clostridium difficile infections: emerging epidemiology and new treatments. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48(Suppl 2):S63–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181a118c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sammons JS, Toltzis P. Recent trends in the epidemiology and treatment of C. difficile infection in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25(1):116–21. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32835bf6c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khanna S, Baddour LM, Huskins WC, et al. The Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile Infection in Children: A Population-Based Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1093/cid/cit075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson L, Song X, Campos J, et al. Changing epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated disease in children. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2007;28(11):1233–5. doi: 10.1086/520732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zilberberg MD, Tillotson GS, McDonald C. Clostridium difficile infections among hospitalized children, United States, 1997-2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(4):604–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1604.090680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Jumaili IJ, Shibley M, Lishman AH, et al. Incidence and origin of Clostridium difficile in neonates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1984;19(1):77–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.1.77-78.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant K, McDonald LC. Clostridium difficile infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(2):145–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318198c984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuki S, Ozaki E, Shozu M, et al. Colonization by Clostridium difficile of neonates in a hospital, and infants and children in three day-care facilities of Kanazawa, Japan. Int Microbiol. 2005;8(1):43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denno DM, Shaikh N, Stapp JR, et al. Diarrhea etiology in a pediatric emergency department: a case control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(7):897–904. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernacchio L, Vezina RM, Mitchell AA, et al. Diarrhea in American infants and young children in the community setting: incidence, clinical presentation and microbiology. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2006;25(1):2–7. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000195623.57945.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubberke ER, Gerding DN, Classen D, et al. Strategies to prevent Clostridium difficile infections in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(Suppl 1):S81–92. doi: 10.1086/591065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schutze GE, Willoughby RE, Committee on Infectious D et al. Clostridium difficile infection in infants and children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):196–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bignardi GE, Staples K, Majmudar N. A case of norovirus and Clostridium difficile infection: casual or causal relationship? J Hosp Infect. 2007;67(2):198–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lukkarinen H, Eerola E, Ruohola A, et al. Clostridium difficile ribotype 027-associated disease in children with norovirus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(9):847–8. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819d1cd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pokorn M, Radsel A, Cizman M, et al. Severe Clostridium difficile-associated disease in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(10):944–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181723d32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koo HL, Ajami NJ, Jiang ZD, et al. A nosocomial outbreak of norovirus infection masquerading as Clostridium difficile infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(7):e75–7. doi: 10.1086/597299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrett SP, Holmes AH, Newsholme WA, et al. Increased detection of Clostridium difficile during a norovirus outbreak. J Hosp Infect. 2007;66(4):394–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1997;32(9):920–4. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 2010;31(5):431–55. doi: 10.1086/651706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant L, Vinje J, Parashar U, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical features of other enteric viruses associated with acute gastroenteritis in american Indian infants. J Pediatr. 2012;161(1):110–15. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman MM, Kerin T, Hull J, et al. Enhancement of detection and quantification of rotavirus in stool using a modified real-time RT-PCR assay. J Med Virol. 2008;80(8):1489–96. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wroblewski D, Hannett GE, Bopp DJ, et al. Rapid molecular characterization of Clostridium difficile and assessment of populations of C. difficile in stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(7):2142–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02498-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El Feghaly RE, Stauber JL, Deych E, et al. Markers of Intestinal Inflammation, not Bacterial Burden, Correlate with Clinical Outcomes in Clostridium difficile Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(12):1713–21. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma C, Wu X, Nawaz M, et al. Molecular characterization of fecal microbiota in patients with viral diarrhea. Curr Microbiol. 2011;63(3):259–66. doi: 10.1007/s00284-011-9972-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]