Abstract

Background

Cognitive impairment, including dementia, is a major health concern with the increasing aging population. Preventive measures to delay cognitive decline are of utmost importance. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most frequent cause of dementia, increasing in prevalence from <1% below the age of 60 years to >40% above 85 years of age.

Methods

We systematically reviewed selected modifiable factors such as education, smoking, alcohol, physical activity, caffeine, antioxidants, homocysteine (Hcy), n-3 fatty acids that were studied in relation to various cognitive health outcomes, including incident AD. We searched MEDLINE for published literature (January 1990 through October 2012), including cross-sectional and cohort studies (sample sizes > 300). Analyses compared study finding consistency across factors, study designs and study-level characteristics. Selecting studies of incident AD, our meta-analysis estimated pooled risk ratios (RR), population attributable risk percent (PAR%) and assessed publication bias.

Results

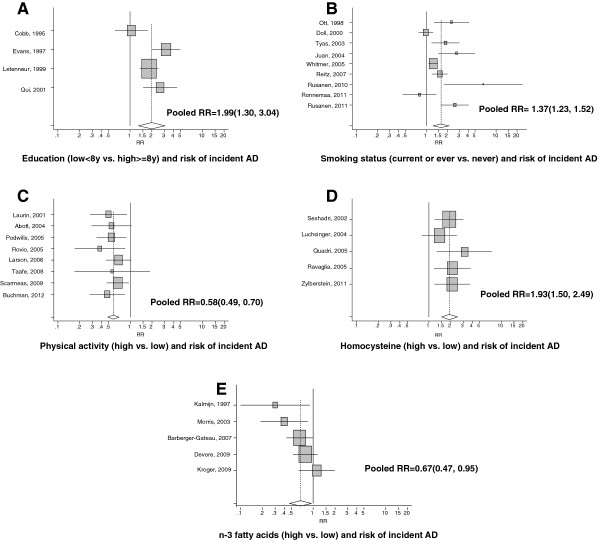

In total, 247 studies were retrieved for systematic review. Consistency analysis for each risk factor suggested positive findings ranging from ~38.9% for caffeine to ~89% for physical activity. Education also had a significantly higher propensity for “a positive finding” compared to caffeine, smoking and antioxidant-related studies. Meta-analysis of 31 studies with incident AD yielded pooled RR for low education (RR = 1.99; 95% CI: 1.30-3.04), high Hcy (RR = 1.93; 95% CI: 1.50-2.49), and current/ever smoking status (RR = 1.37; 95% CI: 1.23-1.52) while indicating protective effects of higher physical activity and n-3 fatty acids. Estimated PAR% were particularly high for physical activity (PAR% = 31.9; 95% CI: 22.7-41.2) and smoking (PAR%=31.09%; 95% CI: 17.9-44.3). Overall, no significant publication bias was found.

Conclusions

Higher Hcy levels, lower educational attainment, and decreased physical activity were particularly strong predictors of incident AD. Further studies are needed to support other potential modifiable protective factors, such as caffeine.

Keywords: Cognition, Dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Risk factor, Nutrition, Meta-analysis

Background

Cognitive function refers to those mental processes that are crucial for the conduct of the activities of daily living. Such mental processes include attention, short-term and long-term memory, reasoning, coordination of movement and planning of tasks [1]. The prevalence of brain disorders affecting cognition (such as stroke and dementia) increases steadily in a linear fashion with age [2]. Cognitive impairment is a major health concern affecting loss of independence in daily activities in old age. Thus, special attention should be devoted to its prevention [3].

Dementia is relatively frequent in the elderly population and was shown to affect about 6.4% of European subjects over the age of 65 years [4]. A review of 50 original articles published between 1989 and 2002 using international data showed that prevalence of dementia for the very old group (85 years and over) varied from 16.7% in China [5] to 43% in Germany [6]. This variability was also reflected within separate age groups among the very old, ranging from 9.6% to 32% for the 85–89 age category and from 41% to 58% for the 95+ age group. Incidence varied between 47 and 116.6 per 1000 and a separate meta-analytic study estimated the incidence in that age group (i.e. 85+) to be around 104 per 1000 [7,8].

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most frequent cause of dementia, increasing in prevalence from less than 1% below the age of 60 years to more than 40% above 85 years of age. The initial phase is generally marked by a progressive deterioration of episodic memory. Other impairments may be entirely absent in the beginning or consist of mild disturbances in naming and executive function. When the process advances, impairment spreads to other aspects of memory and other domains of cognition. Despite lack of curative treatment, epidemiological evidence reveals important risk factors for sporadic AD, many of which are non-modifiable (e.g. ApoE ϵ4, age and sex). This highlights the importance for further evaluation of modifiable risk and preventive factors in that these potential factors may not only delay the onset of cognitive decline, but also can be easily treated. Aside from AD, less frequently occurring forms of dementia include vascular dementia (VaD), mixed dementia, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease with dementia (PD-D), diagnostic criteria for which are described in Table 1. The relative prevalence of AD and VaD and the mixed version of both remain debatable. Ott and colleagues [9] estimated that for the very old, the prevalence of AD was 26.8% while that of VaD was 4.4%. However, VaD appears to be more frequent than AD in certain Japanese and Chinese populations [10].

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Vascular Dementia (VaD), Mixed dementia (MD) and other dementias

| Diagnosis | Criteria |

|---|---|

|

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (NINCDS-ADRDA) Source[11,12]: |

Development of multiple cognitive deficits, with both memory impairment and one (or more) of the following cognitive disturbances: |

| Aphasia (language disturbance) | |

| Apraxia (learned motor skills disturbance) | |

| Agnosia (visuospatial/sensory disturbance) | |

| Executive functioning (foresight, planning, insight anticipation) | |

| Significant impairment in social or occupational functioning, representing a significant decline from a previous level of functioning | |

| |

Other diagnostic criteria: Hachinski Ischemic Score, ICD-10; DSM-IV; ADDTC; updated NINCDS-ADRDA |

|

Vascular Dementia (VaD) (NINDS-AIREN) Source[13]: |

Cognitive decline from previous higher level of function in three areas of function including memory. |

| Evidence of cerebrovascular disease by examination | |

| Evidence of cerebrovascular disease by neuroimaging | |

| Onset either abrupt or within three months of a recognized stroke. | |

|

Vascular Dementia (VaD) (Modified Hachinski Ischemia Score: ≥4) Source[14]: |

Two-point items |

| Abrupt onset | |

| History of stroke | |

| Focal neurologic symptoms | |

| One-point items | |

| Stepwise deterioration | |

| Somatic complaints | |

| History of hypertension | |

| Emotional incontinence | |

| |

Other diagnostic criteria: ICD-10; DSM-IV |

|

Mixed Dementias (MDs) |

|

| Hachinski Ischemic score |

Score based on clinical features: ≤4 = AD; ≥7 = VaD; intermediate score of 5 or 6 = MD. |

| ICD-10 |

Cases that met criteria for VaD and AD |

| DSM-IV |

Cases with criteria for primary degenerative dementia of the Alzheimer type and clinical or neuroimagery feature of VaD. |

| ADDTC |

Presence of ischemic vascular disease and a second systemic or brain disorder. |

| NINDS-AIREN |

Typical AD associated with clinical and radiological evidence of stroke. |

|

Other Dementias |

|

|

Fronto-Parietal Dementia (FTD) Source[15]: |

Behavioral or cognitive deficits manifested by either (1) or (2): |

|

(1) Early and progressive personality change, with problems in modulating behavior; inappropriate responses/activities. | |

|

(2) Early and progressive language changes, with problems in language expression, word meaning, severe dysnomia. | |

| Deficits represent a decline from baseline and cause significant impairment in social and occupational functioning. | |

| Course characterized by gradual onset and continuing decline in function. | |

| Other causes (eg, stroke, delirium) are excluded | |

| Gradual onset and progressive cognitive decline. | |

|

Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) (Consensus Guidelines for the Clinical Diagnosis for Dementia with Lewy Bodies) Source[16]: |

Fluctuating in cognitive performance: Marked variation in cognition or function, or episodic confusion/decreased responsiveness. |

| |

Visual hallucinations: Usually well formed, unprovoked, benign. |

| |

Parkinsonism: Can be identical to Parkinson’s Disease (PD), milder or symmetric. |

|

Parkinson’s Disease with Dementia (PD-D) Source[17]: |

Bradyphrenia (slowness of thought) |

| |

Executive impairment |

| |

Neuropsychiatric symptoms |

| Dysphonia |

Abbreviations: ADDTC: Alzheimer's Disease Diagnostic and Treatment Centers; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th edition; ICD-10: International Classification of Disease, 10th edition; NINCDS-ADRDA: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke -- the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association; NINDS-AIREN: National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke--Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences; PD-D: Parkinson’s disease with dementia.

The present review focuses on selected modifiable risk and protective factors of cognitive impairment, cognitive decline and dementia (including AD), given that they are commonly studied and provide reliable and comparable data. In particular, we focused on the risk and protective factors that could be grouped under three broad categories, namely socioeconomic, behavioral, and nutritional. Consequently, other known risk factors that are modifiable but did not fall under these categories were excluded (e.g. obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, depression, traumatic head injury etc.). In addition, the latter risk factors are potential mediating factors in the causal pathway between our selected factors and cognitive outcomes (e.g. obesity, depression, type 2 diabetes and hypertension may be on the causal pathway between physical activity and cognition; the same for diet→depression, obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension→cognition) and thus are more appropriately studied together rather than with their antecedent putative causes. This is the first study to systematically review those selected modifiable risk and protective factors for cognitive health outcomes in cross-sectional and cohort studies while comparing the consistency of association between those factors and across study-level characteristics. It is also among few recent studies to compare the strength of association across those factors in relation to incident AD using a similar approach [19,20]. Our findings could help guide future research and interventions.

Methods

Literature search

Using MEDLINE, we conducted a systematic review of the literature on cognitive function, decline and dementia focusing on specific risk factors. We considered both original research published between January 1990 and October 2012. We did not include titles prior to 1990 to ensure that diagnostic criteria for dementia and AD were comparable across studies. After an initial search using MESH keywords for risk factors (i.e. education, smoking, physical activity, caffeine/coffee/tea, alcohol, antioxidant/vitamin E, homocysteine and fatty acid) and a title containing the words (cognitive, dementia and Alzheimer), we assessed the retrieved papers for relevance by reading the titles and abstracts. Among those that were selected for review, information was retrieved including study design, contextual setting, sample size, main outcome and key findings.

Final inclusion criteria were: (1) Study sample size > 300. Although this number is arbitrary, it was based on the fact that some study outcomes were relatively rare (e.g. incident AD: <10%) and thus a smaller sample size for a cohort study for example might yield an underpowered study, depending on the distribution of the risk factor. (2) Study design is either cross-sectional or cohort study (thus case-control studies, review articles, commentaries, and basic science papers were excluded); (3) Outcomes include dementia, AD, cognitive function, cognitive decline or cognitive impairment (including MCI)). Although all types of dementia were presented in our description of selected studies, focus was on the more prevalent sub-types including AD and VaD (4) Baseline sample includes general healthy population rather than special groups at risk (e.g. coronary heart disease patients). For the “cognitive decline” and “cognitive function” outcomes, we searched risk factors in the title to expand the range of studies selected beyond those based just on MESH keywords (i.e. “caffeine,” “alcohol” and all other risk factors were also searched in titles when the outcome was “cognitive”). Both cohort and cross-sectional studies that were selected are presented in Table 2. The MEDLINE search and the studies excluded are laid out in Figure 1, showing main reasons for exclusion and final number of studies included for each risk factor. After inclusion of a study, we did not examine cross-references in order to ensure the comparability of the search strategy between risk factors.

Table 2.

Summary of epidemiologic studies of risk and protective factors for cognitive outcomes included in the review

| Study | Age/gender | Year | Country | Study design | Sample size | Outcomes | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(1) Education |

Hypothesis: Lower education is associated with lower cognitive function or higher rate of cognitive decline or increased risk of dementia(including AD) |

||||||

| [21] |

65+/B |

1990 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 5,055 |

Prevalent AD and dementia |

+ |

| [22] |

Mean:58.5/B |

1991 |

Nigeria |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,350 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [23] |

65+/B |

1992 |

France |

Cross-sectional |

N = 2,792 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [24] |

68-77/B |

1992 |

Finland |

Cross-sectional |

N = 403 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [25] |

65+/B |

1993 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 4,485 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [26] |

75+/B |

1994 |

England |

Cohort |

N = 1,195 |

Indicent dementia |

0 |

| [27] |

65+/B |

1994 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 10,294 |

Incident cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [28] |

55+/B |

1995 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 3,330 |

Incident AD and VaD |

+(VaD) |

| [29] |

18+/B |

1995 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 14,883 |

Indicent dementia |

+ |

| [9] |

55-106/B |

1995 |

The Netherlands |

Cross-sectional |

N = 7,528 |

Prevalent dementia, AD and VaD |

+ |

| [30] |

65+/B |

1996 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 2,212 |

Prevalent dementia and cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [31] |

68-78/B |

1996 |

Finland |

Cross-sectional |

N = 403 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [32] |

70+/B |

1997 |

Australia |

Cohort |

N = 652 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [33] |

65+/B |

1997 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 642 |

Incident AD |

+ |

| [34] |

50-80/B |

1997 |

Austria |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,927 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [35] |

Mean:75/M |

1997 |

The Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 528 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [36] |

69-74/M |

1997 |

Sweden |

Cross-sectional |

N = 504 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [37] |

55-84/B |

1997 |

The Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 5,825 |

Cognitive function, decline and incident/prevalent dementia |

+ |

| [38] |

65-84/B |

1997 |

The Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 2,063 |

Incident dementia |

+(IQ better predcitor) |

| [39] |

47-68/B |

1998 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 14,000 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [40] |

60+/B |

1998 |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

N = 495 |

Prevalent dementia |

0 |

| [41] |

65+/B |

1998 |

Taiwan |

Cross-sectional |

N = 2,915 |

Prevalent dementia, AD and VaD |

+(AD) |

| [42] |

18+/B |

1999 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,488 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [43] |

65+/B |

1999 |

France |

Cohort |

N = 3,675 |

Incident AD |

+ |

| [44] |

55-106/B |

1999 |

The Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 6,827 |

Incident dementia |

+(women) |

| [45] |

85+/B |

2000 |

Sweden |

Cohort |

N = 494 |

Cognitive decline and function |

+ |

| [46] |

75+/B |

2001 |

Sweden |

Cohort |

N = 1,296 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [47] |

65+/B |

2002 |

Spain |

Cohort |

N = 557 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [48] |

70+/B |

2002 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 6,577 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [49] |

65+/B |

2002 |

Brazil |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,656 |

Prevalent dementia and AD |

+ |

| [50] |

65+/B |

2002 |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,016 |

Prevalent AD and VaD |

+ |

| [51] |

45-59/M |

2002 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,839 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [52] |

70-79/W |

2003 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 19,319 |

Cognitive function and decline |

+ |

| [53] |

70-79/B |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 4,030 |

Cognitive decline |

+(ApoE-) |

| [54] |

66+/W |

2006 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 6,314 |

Cognitive function and decline |

+ |

| [55] |

Mean age: ~75/B |

2006 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2,786 |

Incident dementia |

+(both whites and blacks) |

| [56] |

55+/B |

2006 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 34,807 |

Prevalent AD and VaD |

+(AD) |

| [57] |

50+/B |

2006 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 16,095 |

Prevalent dementia and AD |

+ |

| [58] |

65+/B |

2007 |

Guam |

Cross-sectional |

N = 2,789 |

Prevalent dementia and AD |

+ |

| [59] |

64-81/B |

2007 |

The Netherlands |

Cross-sectional |

N = 578 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [60] |

60-64/B |

2009 |

Australia |

Cohort |

N = 416 |

Cognitive decline |

0 |

| [61] |

30-64/B |

2009 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,345 |

Cognitive function |

+(literacy better predictor) |

| [62] |

65-96/B |

2009 |

Spain |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,074 |

Prevalent dementia |

+ |

| [63] |

80+/B |

2009 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 3,336 |

Incident dementia |

+ |

| [64] |

Mean:72/B |

2009 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 6,000 |

Cognitive function and decline |

+(cognitive function) 0(cognitive decline) |

| [65] |

60+/B |

2010 |

Malaysa |

Cross-sectional |

N = 2,980 |

Prevalent dementia |

+ |

| [66] |

55+/B |

2010 |

India |

Cross-sectional |

N = 2,466 |

Prevalent dementia and AD |

+ |

| [67] |

65+/B |

2010 |

Brazil |

Cross-sectional |

N = 2,003 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [68] |

60+/B |

2011 |

Brazil |

Cohort |

N = 1,461 |

Cognitive decline |

- |

| [69] |

60-98/B |

2011 |

Italy |

Cohort |

N = 1,270 |

Incident cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [70] |

60+/B |

2011 |

Mexico |

Cohort |

N = 7,000 |

Prevalent and incident dementia |

+ |

| [71] |

54-95/B |

2011 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,014 |

Cognitive decline |

0 |

| Study |

Age/gender |

Year |

Country |

Design |

Sample size |

Outcome |

Finding |

|

(2) Behavioral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2.1.) Smoking |

Hypothesis: Current or ever smoking status is associated with lower cognitive function or higher rate of cognitive decline or increased risk of dementia(including AD) |

||||||

| [72] |

65+/B |

1993 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,201 |

Cognitive decline |

0 |

| [73] |

65+/B |

1994 |

France |

Cross-sectional |

N = 3,770 |

Prevalent AD, cognitive impairment |

0 |

| [74] |

74+/B |

1996 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 647 |

Cognitive function |

0 |

| [75] |

Mean:58.6/M |

1997 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 3,429 |

Cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [36] |

69-74/M |

1997 |

Sweden |

cross-sectional |

N = 504 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [76] |

75+/B |

1998 |

Australia |

Cohort |

N = 327 |

Incident dementia and AD |

0 |

| [77] |

adults/B |

1998 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,469 |

Cognitive function |

0 |

| [78] |

55+/B |

1998 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 6,870 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+(ApoE4−) |

| [79] |

56-69/M |

1999 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 569 |

Cognitive impairment |

+(ApoE4−) |

| [80] |

45-59/M |

1999 |

UK |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,870 |

Cognitive function |

0 |

| [81] |

65+/B |

2000 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 889 |

Cognitive Impairment |

+ |

| [82] |

Mean: 81/M |

2000 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 34,439 |

Definite or probable AD |

0 |

| [83] |

45-70/B |

2002 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 1,927 |

Cognitive change |

+ |

| [84] |

65+/B |

2003 |

Taiwan |

Cohort |

N = 798 |

Cognitive decline |

0 |

| [85] |

43-53/B |

2003 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 3,035 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [86] |

Mean:78/M |

2003 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 3,734 |

Incident AD |

+ |

| [87] |

60+/B |

2003 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 3,012 |

Cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [88] |

60+/B |

2004 |

China |

Cohort |

N = 2,820 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [89] |

65+/B |

2004 |

European cohorts |

Cohort |

N = 17,610 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [90] |

65-84/B |

2004 |

Italy |

Cohort |

N = 5,632 |

Mild cognitive impairment |

0 |

| [91] |

40-80/M |

2004 |

The Netherlands |

Cross-sectional |

N = 900 |

Cognitive function |

0 |

| [92] |

Mean:75/B |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 791 |

Cognitive function and decline |

+(75 + and ApoE4−) |

| [93] |

40-44/B |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 8,845 |

Incident dementia |

+ |

| [94] |

50+/B |

2006 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 2,000 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [95] |

55+/B |

2007 |

The Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 6,868 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [96] |

43-70/B |

2008 |

The Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 1,964 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [97] |

35-55/B |

2008 |

France |

Cohort |

N = 4,659 |

Cognitive function |

+(memory) |

| [98] |

46-70/B |

2009 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 11,151 |

Incident dementia |

+ |

| [99] |

65+/B |

2009 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,557 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [100] |

90-108/B |

2009 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 681 |

Cognitive impairment |

+(men) |

| [63] |

Mean:83.5/B |

2009 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 3,336 |

Incident dementia |

0 |

| [101] |

65-79/B |

2010 |

Finland |

Cohort |

N = 1,449 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [102] |

Mean:71.8/B |

2010 |

Taiwan |

Cohort |

N = 1,436 |

Incident cognitive impairment |

- |

| [103] |

50y/M |

2011 |

Sweden |

Cohort |

N = 2,268 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+(non-AD) |

| [104] |

Mean:60.1/B |

2011 |

Finland |

Cohort |

N = 21,123 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [105] |

44-69/B |

2012 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 7,236 |

Cognitive decline |

+(men) |

| Study |

Age/gender |

Year |

Country |

Design |

Sample size |

Outcome |

Finding |

|

(2.2.) Alcohol |

Hypothesis: Moderate alcohol consumption is protective against poorer cognitive function, higher rate of cognitive decline and dementia |

||||||

| [106] |

65+/B |

1996 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 2,040 |

Cognitive function |

+(J-shaped) |

| [107] |

59-71/B |

1997 |

France |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,389 |

Cognitive function |

+ (women) |

| [76] |

75+/B |

1998 |

Australia |

Cohort |

N = 327 |

Incident dementia and AD |

0 |

| [77] |

40-80/B |

1998 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1469 |

Cognitive function |

0 |

| [108] |

55-88/B |

1999 |

USA |

Cohort |

N = 1786 |

Cognitive function |

+(U-shaped) |

| [109] |

65+/B |

2001 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,836 |

Cognitive function |

+(U-shaped for men, linear for women) |

| [110] |

Mean:70/B |

2001 |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

N = 15,807 |

Cognitive impairment |

+(U-shaped) |

| [83] |

45-70/B |

2002 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 1,927 |

Cognitive change |

+(women > men) (J-shaped) |

| [111] |

18+/B |

2000 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,448 |

Cognitive decline |

+(women > men) (U-shaped) |

| [112] |

53/B |

2003 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 10,317 |

Cognitive function |

0 |

| [87] |

60+/B |

2003 |

China |

Cohort |

N = 3,012 |

Cognitive impairment |

- |

| [113] |

65-79/B |

2004 |

Finland |

Cohort |

N = 1,464 |

Cognitive function |

+(U-shaped) - (ApoE4+) |

| [114] |

65+/B |

2004 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 4,417 |

Cognitive function |

+(current drinker vs. former or abstainer) |

| [115] |

35-55/B |

2004 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 10,308 |

Cognitive function |

+(linear, some cognitive domains) |

| [116] |

65+/B |

2005 |

US |

cohort |

N = 1,624 |

Cognitive function |

+(current drinker vs. former or abstainer) |

| [117] |

Mean:74/B |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,098 |

Cognitive function and decline |

+(J-shaped) |

| [118] |

43-53/B |

2005 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 1,764 |

Cognitive decline |

Linear + (slower memory decline: men) -(faster psychomotor speed decline: women) |

| [119] |

20-24,40-44,60-64/B |

|

Australia |

Cross-sectional |

N = 7,485 |

Cognitive function |

J-shaped + (light drinkers vs. abstainers) |

| [120] |

70-81/W |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 11,102 |

Cognitive function and decline |

+(J-shaped) (cognitive decline) |

| [121] |

65-89/M |

2006 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 760 |

Cognitive function |

+(linear, J-shaped) |

| [122] |

40+/B |

2006 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,428 |

Cognitive decline |

+(linear) |

| [123] |

65-79/B |

2006 |

Finland |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,341 |

Cognitive function |

+(linear) |

| [124] |

65-84/B |

2007 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,445 |

Incident MCI and MCI→ dementia |

+(U-shaped) |

| [125] |

50+/B |

2010 |

China |

Cohort |

N = 30,499 |

MCI→ dementia |

+(J-shaped) |

| [126] |

50+/B |

2010 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 9,571-28,537 |

Cognitive function |

+(occasional alcohol use vs. none) |

| [127] |

65+/B |

2009 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 314 |

Cognitive impairment |

+(U-shaped) |

| [128] |

70/B |

2011 |

UK |

Cross-sectional |

N = 922 |

Cognitive function |

+(linear, verbal memory) |

| [129] |

55+/B |

2011 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,337 |

Cognitive function |

0 -(executive function) |

| [130] |

55+/B |

2011 |

France |

Cross-sectional |

N = 4,073 |

Cognitive function |

-(high alcohol use, Low SES) |

| [131] |

45+/B |

2012 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 571 |

Cognitive decline |

+(heavy drinking) |

| Study |

Age/gender |

Year |

Country |

Design |

Sample size |

Outcome |

Finding |

|

(2.3.) Physical activity |

Hypothesis: Physical activity is protective against poorer cognitive function, higher rate of cognitive decline and dementia(including AD) |

||||||

| [132] |

70+/B |

2001 |

Hong Kong |

Cohort |

N = 2030 |

Cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [133] |

65+/B |

2001 |

Canada |

Cohort |

N = 4615 |

Incident cognitive impairment and AD |

+ |

| [134] |

65-84/M |

2001 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 347 |

Cognitive decline |

+(ApoE4+) |

| [135] |

65+/F |

2001 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 5,925 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [136] |

75+/B |

2003 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 469 |

Incident dementias (AD, VaD and others) |

+ |

| [137] |

71-93/M |

2004 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2257 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [138] |

65+/B |

2004 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1146 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [139] |

80+/M |

2004 |

European countries |

Cohort |

N = 295 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [140] |

70-81/W |

2004 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 18766 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [141] |

65+/M |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 3375 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+(ApoE4-) |

| [142] |

65-79/B |

2005 |

Sweden |

Cohort |

N = 1449 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [143] |

65+/B |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 4055 |

Cognitive decline |

- |

| [144] |

75+/B |

2006 |

Sweden |

Cohort |

N = 776 |

Incident dementia |

+ |

| [145] |

65+/B |

2006 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1740 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [146] |

65+/W |

2010 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 9344 |

Cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [147] |

60+/B |

2008 |

Greece |

Cohort |

N = 732 |

Cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [148] |

71-92/M |

2008 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2263 |

Dementia |

+ |

| [149] |

70+/B |

2009 |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

N = 668 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [100] |

90-108/B |

2009 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 681 |

Cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [150] |

65+/B |

2009 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1880 |

Incident AD |

+ |

| [151] |

70-79/B |

2009 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2509 |

Cognitive function and decline |

+ |

| [152] |

Mean:51y/B |

2010 |

Iceland |

Cohort |

N = 4945 |

Cognitive function and dementia |

+ |

| [153] |

55+/B |

2010 |

Germany |

Cohort |

N = 3903 |

Incident cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [154] |

60+/B |

2010 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 5903 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [155] |

65+/W |

2010 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 9344 |

Cognitive function and impairment |

+ |

| [156] |

Mean:82/B |

2012 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 716 |

AD Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [157] |

40-84/B |

2012 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 405 (40–59 years) N = 342 (60–84 years) |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [158] |

65+/B |

2012 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2491 |

Incident dementia & AD |

+ |

| Study |

Age/gender |

Year |

Country |

Design |

Sample size |

Outcome |

Finding |

|

(3) Nutritional |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(3.1) Caffeine(coffee or tea) |

Hypothesis: Caffeine consumption is protective against poorer cognitive function, higher rate of cognitive decline and dementia |

||||||

| [159] |

18+/B |

1993 |

UK |

Cross-sectional |

N = 9,003 |

Cognitive function |

+(caffeine) |

| [160] |

Mean: 73/B |

2002 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,528 |

Cognitive function |

0(coffee) |

| [161] |

24-81/B |

2003 |

The Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 1,376 |

Cognitive change |

0(caffeine) |

| [162] |

70+/B |

2006 |

Japan |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,003 |

Cognitive impairment |

+(green tea) |

| [163] |

Mean ~ 75/M |

2007 |

Finland, the Netherlands and Italy |

Cohort |

N = 667 |

Cognitive decline |

+(coffee, J-shaped) |

| [164] |

55+/B |

2008 |

Singapore |

Cohort |

N = 1,438 |

Cognitive impairment and decline |

+(tea) |

| [165] |

65-79/B |

2009 |

Finland |

Cohort |

N = 1,409 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+(coffee), 0(tea) |

| [100] |

90+/B |

2009 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 681 |

Cognitive impairment |

+(tea, men) |

| [166] |

65+/B |

2009 |

Finland |

Cohort |

N = 2,606 |

Cognitive function, incident dementia and MCI |

0(coffee) |

| [167] |

70-74/B |

2009 |

Norway |

Cross-sectiona |

N = 2,031 |

Cognitive impairment |

+(tea) |

| [168] |

17-92/B |

2009 |

UK |

Cross-sectional |

N = 3,223 |

Cognitive function |

0(caffeine) |

| [169] |

70/B |

2010 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 923 |

Cognitive function |

+(coffee); −(tea) |

| [170] |

55+/B |

2010 |

Singapore |

Cross-sectional |

N = 716 |

Cognitive function |

+(tea) |

| [171] |

65+/B |

2010 |

France |

Cohort |

N = 641 |

Cognitive decline |

+(caffeine, women) |

| [172] |

65+/B |

2010 |

Portugal |

Cohort |

N = 648 |

Cognitive decline |

+(caffeine, women) |

| [173] |

65+/B |

2011 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 4,809 |

Cognitive decline |

+(caffeine, women) |

| [174] |

Mean:54/M |

2011 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 3,494 |

Incident dementia and cognitive impairment |

0(caffeine) |

| [175] |

Mean:91.4/B |

2012 |

Singapore |

Cohort |

N = 7,139 |

Cognitive change |

+(tea) |

| Study |

Age/gender |

Year |

Country |

Design |

Sample size |

Outcome |

Finding |

|

(3.2) Antioxidants/Vitamin E |

Hypothesis: Antioxidants, including vitamin E, are protective against poorer cognitive function, higher rate of cognitive decline and dementia(including AD) |

||||||

| [176] |

55-95/B |

1996 |

Netherlands |

cohort |

N = 5,182 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [177] |

66-97/B |

1998 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,059 |

Cognitive function |

0 |

| [178] |

65+/B |

1998 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 633 |

Incident AD |

+ |

| [179] |

5075/B |

1998 |

Austria |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,769 |

Cognitive performance |

+(Vit. E) |

| [180] |

71-93/M |

2000 |

Hawaii |

Cohort |

N = 3,385 |

Incident AD, VaD, MD and OD |

+(VaD) |

| [181] |

48-67/B |

2000 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 12,187 |

Cognitive performance |

0 |

| [182] |

55+/B |

2002 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 5,395 |

Incident AD |

+ |

| [183] |

65+/B |

2002 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 815 |

Incident AD |

+(Vit. E, ApoE4−) |

| [184] |

65-102/B |

2002 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2,889 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [185] |

65+/B |

2003 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2,969 |

Incident dementia Incident AD |

0 |

| [186] |

70-79/W |

2003 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 14,968 |

Cognitive function |

+(Vit. E) |

| [187] |

65+/B |

2003 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 980 |

Incident AD |

0 |

| [188] |

45-68/M |

2004 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2,459 |

Incident dementia and AD |

0 |

| [189] |

65+/B |

2004 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 4,740 |

Incident and prevalent AD |

+ |

| [190] |

65+/B |

2005 |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,033 |

Prevalent dementia and cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [191] |

55+/B |

2005 |

Netherlands |

Cross-sectional |

N = 3,717 |

Prevalent AD |

0 |

| [192] |

65-105/B |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 616 |

Incident Dementia Incident AD |

0 |

| [193] |

65+/B |

2005 |

Canada |

Cohort |

N = 894 |

Cognitive decline Dementia |

+ |

| [194] |

65+/B |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 3,718 |

Incident AD Cognitive function |

+ |

| [195] |

Mean:73.5/B |

2007 |

France |

Cross-sectional |

N = 589 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [196] |

60+/W |

2007 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 526 |

Cognitive impairment |

+(Vit. E) |

| [197] |

65+/B |

2007 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 3,831 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [198] |

65+/B |

2008 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 3,376 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [199] |

65+/B |

2008 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2,969 |

Incident Dementia Incident AD |

0 |

| [200] |

65+/B |

2008 |

Italy |

Cohort |

N = 761 |

Cognitive impairment |

+(Vit. E Sub-type) |

| [201] |

70+/W |

2010 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 16,010 |

Cognitive function & decline |

+(cognitive function) |

| [202] |

70/B |

2011 |

UK |

Cross-sectional |

N = 882 |

Cognitive function |

0 |

| Study |

Age/gender |

Year |

Country |

Design |

Sample size |

Outcome |

Finding |

|

(3.3) Homocysteine |

Hypothesis: Homocysteine is a risk factor for poorer cognitive function, higher rate of cognitive decline and dementia (including AD) |

||||||

| [203] |

55+/B |

1999 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 702 |

Cognitive function and decline |

0 |

| [204] |

60+/B |

2002 |

UK |

Cross-sectional |

N = 391 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [205] |

55+/B |

2002 |

The Netherlands |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,077 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [206] |

Mean:76/B |

2002 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,092 |

Incident AD |

+ |

| [207] |

60+/B |

2003 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,789 |

Global cognitive function |

+ |

| [208] |

Mean:73/B |

2003 |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

N = 650 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [209] |

65+/B |

2004 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 679 |

Incident and prevalent AD |

0 |

| [210] |

Mean:72/B |

2005 |

Turkey |

Cohort |

N = 1,249 |

Incident dementia, AD, MCI |

0 |

| [211] |

60+/B |

2005 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,789 |

Cognitive impairment and dementia |

0 |

| [212] |

40-82/B |

2005 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 2,096 |

Cognitive function |

+(60 + y) |

| [213] |

70-79/B |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 499 |

Cognitive function and decline |

+(cognitive function) |

| [214] |

85+/B |

2005 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 599 |

Cognitive impairment and decline |

+(with impairment) |

| [215] |

65+/B |

2005 |

Switzerland |

Cohort |

N = 623 |

Incident MCI, dementia, AD and VaD |

+ |

| [216] |

60+/B |

2005 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,789 |

Cognitive impairment and dementia |

+ |

| [217] |

Mean:74/B |

2005 |

Italy |

Cohort |

N = 816 |

Incident AD |

+ |

| [218] |

50-70/B |

2005 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,140 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [219] |

50-85/M |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 321 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [220] |

Mean:62/B |

2006 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 812 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [221] |

55+/B |

2006 |

China |

Cross-sectional |

N = 451 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [222] |

Mean:59/B |

2006 |

The Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 345 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [223] |

65+/B |

2007 |

UK |

Cohort |

N = 1,648 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [224] |

60-101/B |

2007 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 1,779 |

Incident dementia and MCI |

+ |

| [225] |

60-85/B |

2007 |

South Korea |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,215 |

Prevalent MCI |

+ |

| [226] |

26-98/B |

2008 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 911 |

Cognitive function |

+(ApoE4+) |

| [227] |

65+/B |

2008 |

Korea |

Cross-sectional |

N = 607 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [228] |

Mean:72/B |

2008 |

Korea |

Cohort |

N = 518 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [229] |

Mean:77/B |

2009 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 516 |

Prevalent and incident MCI |

0 |

| [230] |

38-85/B |

2010 |

Sweden |

Cohort |

N = 488 |

Incident dementia |

0 |

| [231] |

65+/B |

2010 |

The Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 1,076 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [232] |

Mean:78/W |

2011 |

Germany |

Cross-sectional |

N = 420 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [233] |

38-60/W |

2011 |

Sweden |

Cohort |

N = 1,368 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [234] |

70-89/M |

2012 |

Australia |

Cohort |

N = 4,227 |

Incident dementia |

+ |

| [235] |

70-89/M |

2012 |

Australia |

Cohort |

N = 1,778 |

Incident cognitive impairment |

+ |

| Study |

Age/gender |

Year |

Country |

Design |

Sample size |

Outcome |

Finding |

|

(3.4) n-3 fatty acids |

Hypothesis: n-3 fatty acids are protective against poorer cognitive function, higher rate of cognitive decline and dementia(including AD) |

||||||

| [236] |

69-89/M |

1997 |

Netherlands |

cohort |

N = 476 |

Cognitive impairment & decline |

0 |

| [237] |

55+/B |

1997 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 5,386 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+ |

| [238] |

55+/B |

2002 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 5,395 |

Incident dementia and AD |

0 |

| [239] |

65-94/B |

2003 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 815 |

Incident AD |

+ |

| [240] |

45-70/B |

2004 |

Netherlands |

Cross-sectional |

N = 1,613 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [241] |

65+/B |

2005 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 3,718 |

Cognitive decline |

0 |

| [242] |

65+/B |

2007 |

France |

Cohort |

N = 8,085 |

Incident dementia and AD |

+(ApoE4-) |

| [243] |

50+/B |

2007 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2,251 |

Cognitive decline |

+(hypertensive, Dyslipidemic) |

| [244] |

Mean:76/B |

2007 |

Italy |

Cross-sectional |

N = 935 |

Prevalent dementia |

+ |

| [245] |

50-70/B |

2007 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 404-807 |

Cognitive function and change |

+(change) |

| [246] |

50+/B |

2008 |

US |

Cohort |

N = 2,251-7,814 |

Cognitive decline |

+(hypertensives) |

| [247] |

65-80/B |

2008 |

Finland |

Cohort |

N = 1,449 |

MCI and cognitive function |

+ |

| [248] |

Mean:78/B |

2008 |

France |

Cohort |

N = 1,214 |

Incident dementia |

+ |

| [249] |

65+/B |

2009 |

Multi-national |

Cross-sectional |

N = 14,960 |

Prevalent dementia |

+ |

| [250] |

55+/B |

2009 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 5,395 |

Incident dementia and AD |

0 |

| [251] |

65+/B |

2009 |

Canada |

Cohort |

N = 663 |

Incident dementia or AD |

0 |

| [252] |

Mean:68/M |

2009 |

Netherlands |

Cohort |

N = 1,025 |

Cognitive function |

0 |

| [253] |

76-82/W |

2009 |

France |

Cohort |

N = 4,809 |

Cognitive decline |

+ |

| [254] |

Mean:75/B |

2010 |

Spain |

Cross-sectional |

N = 304 |

Cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [255] |

35-54/B |

2010 |

US |

Cross-sectional |

N = 280 |

Cognitive function |

+ |

| [256] |

55+/B |

2011 |

Singapore |

Cohort |

N = 1,475 |

Cognitive function and decline |

+(supplements) |

| [257] |

Mean:~64/B |

2011 |

France |

Cohort |

N = 3,294 |

Cognitive impairment |

+ |

| [258] | 65+/B | 2011 | France | Cohort | N = 1,228 | Cognitive decline | +(ApoE4+; depressed) |

+Hypothesized association; − Association against hypothesis; 0: No association.

Abbreviations: AD: Alzheimer’s Disease; ApoE: Apolipoprotein E; B: Both; M: Men; MCI: Mild Cognitive Impairment; MD = Mixed Dementia; OD = Other dementia; UK: United Kingdom; US: United States; VaD: Vascular Dementia; W: Women.

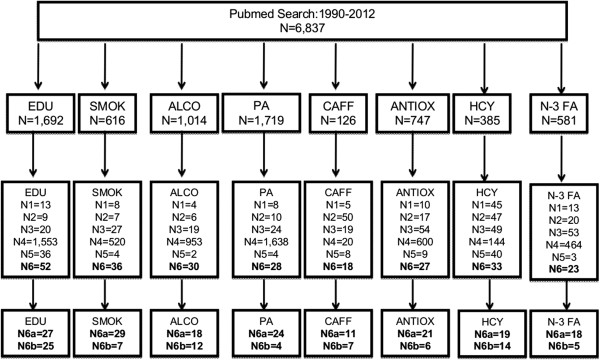

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection for systematic review and meta-analysis. Notes: MEDLINE searches (1990–2012) included the following: (1) “Risk factor” as MESH term AND “Dementia” in title; (2) “Risk factor” as MESH term AND “Alzheimer” in title; (3) “Risk factor” as MESH term AND “Alzheimer” in title; (4) “Risk factor” as MESH term AND “cognitive” in title; (5) “Risk factor” in title and “cognitive” in title. Given that each search is not mutually exclusive of other searches, there were duplicates which were deleted from the final number of included studies. The following notations are defined follows: N1 = Studies excluded from all searches combined due to small sample size; N2 = Studies excluded from all searches combined due to design being neither cross-sectional nor cohort; N3 = Studies excluded from all searches combined due to being a review or a letter to the editor; N4 = Studies excluded from all searches combined due to lack of relevance to topic or hypothesis; N5 = Studies excluded from all searches combined for other reasons (e.g. special group of people); N6 = Final included studies; N6a = Final included cohort studies; N6b = Final included cross-sectional studies.

Out of a total search of 6,837 titles and abstracts between 1990 and 2012 (range:126 for caffeine to 1,692 for education), 247 published original epidemiologic studies (167 cohort-, 80 cross-sectional studies) were included in our review. A database was built accordingly using Endnote ver. X3 [259]. Each study was summarized in Table 2 by listing the sample characteristics (age, gender, country), study design, sample size and type of outcome. Given the diversity of types of outcomes, a quantitative meta-analysis for all studies with all outcomes was not possible. Thus, a qualitative method to assess overall consistency was conducted. This analysis was mainly based on the hypothesized direction of association and the final conclusion of the study. Thus, main findings based on the pre-set hypothesis was coded (+: supports the hypothesis; 0: no significant finding; −: against the hypothesis). In addition, within +, we coded studies as partially supporting the hypothesis for three main reasons: “some outcomes but not others”, “some exposures but not others”, “some sub-group(s) but not others”. These papers are sorted by risk factor, year of publication and first author’s last name.

Descriptive analysis

In the descriptive part of the analysis, a data point consisted of a study finding within a design/risk factor dyad (e.g. cohort/education). Using the data points, we conducted an analysis to assess consistency of positive findings across risk factors and study designs (cohort vs. cross-sectional). In particular, we estimated the % of positive findings for all participants and most outcomes; % of positive findings for some outcomes or exposures but not others; % of positive findings for sub-groups; % null findings; % of findings against hypothesized direction. In addition, study-level characteristics (e.g. year and country of publication, study design, type of cognitive outcome, sample size, age group, sex) were described in detail and compared across risk factors, using χ2 test, independent samples t-test and one-way ANOVA.

Consistency analysis: all data points

In this part of the analysis, we modeled study finding as a binary outcome coded as 0=”null finding or finding against hypothesized direction” (referent category), 1=”positive or partially positive finding”, as a function of study-level characteristics using a logistic regression model. The study-level characteristics were entered as main effects as follows: (1) Year of publication; (2) Country of publication (1 = US, 2 = European country, 3 = Others), (3) risk factor (1 = education, 2 = smoking, 3 = alcohol, 4 = physical activity, 5 = caffeine, 6 = antioxidants, 7 = homocysteine, 8 = n-3 fatty acids); (4) sample size (when a range was provided, the average was taken), (5) Study participant age group: 1 = contains ages <65y, 0 = does not contain ages <65y; (6) Participant gender composition: 1 = Men only; 2 = Women only; 3 = Both; (7) Study design: 1 = cross-sectional; 2 = cohort; (8) Number of cognitive outcomes included in the study (e.g. 1 if only incident AD was the outcome; 2 if it is both incident AD and incident dementia); (9) General category of cognitive outcome(s): 1 = dementia/AD/impairment; 2 = cognitive function/decline; 3 = both.

Meta-analysis: data points with incident AD and selected risk or protective factors

Focusing on data points with incident AD as an outcome, we conducted further meta-analysis to assess the strength of the association between selected risk or protective factors and this outcome. This analysis was thus restricted to prospective cohort studies with available data points that had comparable measurements for each risk/protective factor, thus allowing to estimate a pooled measure of association across those data points and studies. The original reported odd ratios (ORs), relative risks (RRs) or Hazard Ratios (HRs) were combined into a pooled value with 95% confidence interval (CI). The RRs were then pooled using random effects models when included study data points were deemed heterogeneous based on the Q-test for homogeneity (p < 0.05) or fixed effect when study data points were homogenous (p > 0.05), which are also presented among results. As such, a summary or pooled RR was provided using forest plots and computed by computing the weighted average of the natural logarithm of each relative measure of interest weighting by the inverse of each RR’s respective variance [260]. Random effects models that further incorporated between-study variability were conducted using DerSimonian and Laird’s methodology.

Considering estimates of exposure prevalence from the largest study with available data on each exposure, we also computed a population attributable risk percentage (PAR%) by pooling data points from all studies together.

| (1.1) |

| (1.2) |

| (1.3) |

As shown in Equations 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3, RR (point estimates per study and data point; 95% CI) was applied to the formula and Prexp was the estimated prevalence of each exposure. The estimation of SE for PAR% was obtained using the delta method [261].

Finally, in order to examine publication bias, we used Begg’s funnel plots; each RR point estimate was plotted against their corresponding standard errors (SE) for each study on a logarithmic scale [262,263], for all exposures combined. This type of bias was also formally tested using the Begg-adjusted rank correlation tests [264] and the Egger’s regression asymmetry test [265]. All analyses were conducted with STATA 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) [266]. Type I error was set at 0.05 for all measures of association.

Results and discussion

Socio-economic Status (SES) as indicated by education

Early life conditions are related to cognitive development and abilities in childhood and cognitive function in adulthood. Low educational attainment and other markers of low socio-economic position (SEP) were associated with poorer cognitive function in adulthood and age-related cognitive decline and impairment, as well as greater risk or prevalence of dementia and AD in the elderly. In this study, we focused our attention on education as a maker of SES, given that it is the most commonly studied protective factor.

Several possible mechanisms support the finding that less education is related to cognitive decline: First, education may exert direct effects on brain structure early in life by increasing synapse number or vascularization and creating cognitive reserve. This was named the “reserve capacity” hypothesis. Thus, this hypothesis states that early life conditions affect the pace of cognitive decline in later life [38]. Education in early life may have effects in later life if persons with more education continue searching for mental stimulation (“the use it or lose it” hypothesis), which may lead to beneficial neurochemical or structural alterations in the brain [267]. Indeed, in one study, recent mental stimulation was associated with improved cognitive functioning [268]. Alternatively, education may act through several “behavioral mediators” to improve health in general, and cognitive functioning in particular [267]. This hypothesis was confirmed by a study using the Framingham cohort which suggested that education was uniquely protective against VaD and not associated with AD [28]. This finding was explained by mediating effects of other risk factors of cognitive decline, including smoking and hypertension, which in turn can initiate cerebrovascular damage. However, Lee and colleagues [52] found evidence contrary to this hypothesis by showing a sustained strong association between education and cognitive functioning after adjustment for behavioral and health-related factors.

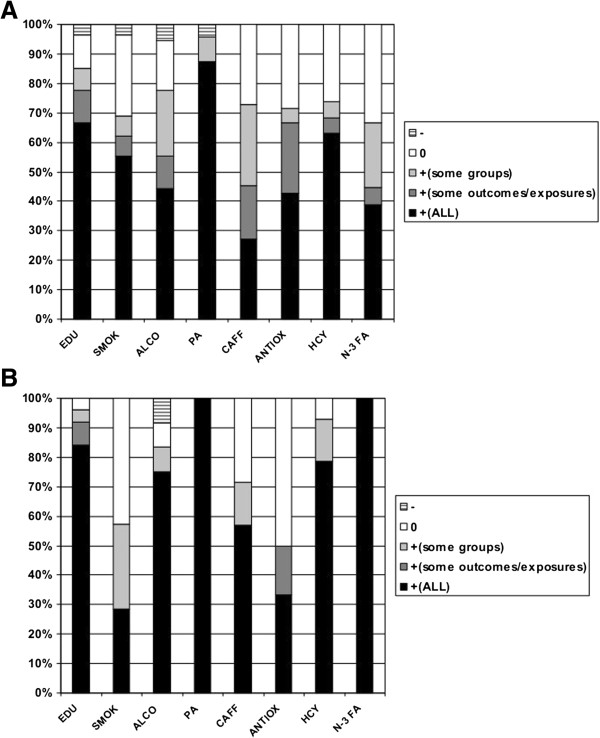

Based on our findings (Table 2 and Figure 2A), 18 (66.7%) of the 27 cohort studies that met our selection criteria found that lower education was linked to a worse cognitive outcome in the overall population and for all studied outcomes, 1 found this relationship with incident VaD but not AD [28], 1 found the relationship with cognitive function but not decline [64], 1 concluded that IQ was a better predictor than education [38], and 2 detected a significant association in the hypothesized direction only in women [44] and in ApoE4- individuals [53]. The remaining four cohort studies did not find an association in the hypothesized direction [26,60,68,71].

Figure 2.

Main findings (%) of selected studies, given hypothesis: (A) Cohort Studies (B) Cross-sectional studies.

Note: +(ALL) = positive finding, given hypothesis, for all subjects and most outcomes of interest; +(some outcomes) = positive finding, given hypothesis, for all subjects and some outcomes of interest but not others; +(some groups) = positive finding, given hypothesis, for some groups and most outcomes of interest; 0 = null finding, given hypothesis; − = finding against hypothesized direction. *P-value based on χ2 test for independence between risk factor and finding.

The association between education and the studied cognitive outcomes was in the hypothesized direction, with higher education being protective, for the majority of the selected cross-sectional studies (21 out of 25, 84%), while 2 found an association with prevalent AD but not VaD [41,56], 1 found that literacy was a better predictor than education [61], and 1 failed to detect a significant association [40] (See Table 2 and Figure 2B).

Behavioral factors

Several behavioral factors were selected, including smoking, alcohol drinking,and physical activity.

Smoking

Smoking is a risk factor for several chronic diseases, but its long-term relationship with dementia of various sub-types is still controversial. In fact, smoking is well known to increase the risk of stroke [269] and thus subsequent vascular types of dementia (VaD). However, many studies have concluded that smoking status influenced risk of VaD independently of stroke status and thus may have an effect beyond cerebrovascular disease. In addition, studies that have shown a direct impact of smoking on AD, suggest that smoking might in fact influence neurodegeneration. A vast amount of literature points to a role of smoking in oxidative stress and inflammation, both mechanisms believed to play a key role in AD [270].

However, it is also biologically plausible that smoking might protect against cognitive decline and AD, given that nicotine, a key active component of tobacco, may enhance the release of acetylcholine, increase the density of nicotnic receptors, therefore improving attention and information processing [271]. It is now known that AD is characterized by cholinergic system deficits which may be delayed through tobacco consumption [271,272].

Population-based evidence of an effect of smoking on cognitive outcomes was inconclusive, with most longitudinal studies reporting weak or null associations [63,72,74,76,77,82,84,90]. However, a number of other cohort studies have found a positive association between smoking and risk of incident dementia and AD [78,86,88,93,95,98,101,103,104] as well as incident cognitive impairment [75,81,90] and age-related cognitive decline [83,85,89,96,99,105].

For instance, the British 1946 birth cohort study pointed to the difficulty of finding an association between smoking and cognitive impairment given the differential high mortality of smokers especially among the elderly population [85]. After controlling for a range of socioeconomic and health status indicators (both physical and mental), they found that smokers who survive into later life may be at risk of clinically significant cognitive decline. However, these effects were accounted for largely by heavy smokers, i.e. those who smoked 20 cigarettes per day or more. Earlier research on middle aged adults suggested that current smoking and number of pack-years of smoking were related to reduced performance on tests of psychomotor speed and cognitive flexibility assessed approximately five years later [83]. Similar results were shown for cognitive decline in a large cohort study (Rotterdam study) conducted in multiple European countries [89] and in another more recent study conducted in the United States [92].

Among studies that examined incidence of AD in relation to smoking status, two of the largest European cohort studies reported conflicting results. While one found no relationship between smoking status and incident AD among a large sample of 34,439 older UK men (mean age: 81) [82], the recent 2011 study found that heavy smoking increased the risk of dementia and AD in a younger sample of 21,123 older Finnish adults (Mean age:60.1) that comprised both men and women [104].

In sum, 16 (55.2%) out of the 29 selected cohort studies linking smoking to the various cognitive outcomes found the relationship to be in the hypothesized direction in the entire population that was studied and for most outcomes of interest [75,81,83,85,86,88,89,92-96,98,99,101,104], while 2 found this relationship for some outcomes but not others [97,103] and 2 detected it for a sub-group of the total population [78,105], while the remaining 9 studies did not find an association [63,72,74,76,77,82,84,90] or found an association in the opposite direction [102]. (See Table 2 and Figure 2A).

Only 2 (28.6%) of the 7 cross-sectional studies found an association in the hypothesized direction [36,87], while 2 detected it for a sub-group of the total population [79,100], and the remaining 3 did not detect a significant association [73,80,91], (See Table 2 and Figure 2B).

Alcohol

Alcohol consumption in moderation was hypothesized to be protective against cognitive decline and impairment in old age. Several mechanisms may be involved in explaining the potential protective effect of moderate alcohol consumption on various cognitive outcomes. First, this effect might be mediated through cardiovascular risk factor reduction, partly through a dampening effect of ethanol on platelet aggregation, or through a modification of the serum lipid profile. Second, another potential mechanism in which alcohol can have a direct effect on cognitive function is through acetylcholine release in the hippocampus, which in turn enhances learning and memory [273].

The Rotterdam study [83] also examined the effect of alcohol use on cognition. They found that past alcohol consumption’s effect on speed and flexibility appeared to be slightly U-shaped, with the best performance observed among those who drank 1–4 glasses of alcohol per day, although this association was stronger among women than among men. Other studies also detected sex differences [106,107,111]. Light to moderate alcohol consumption was also found beneficial based on findings of other cohort and cross-sectional studies with a U- or J-shaped pattern observed [108-110,113,114,116,117,119-121,124-127]. However, in other studies, a linear dose–response relationship between alcohol use and improved cognition was noted, though the authors cautioned that these should not encourage increased alcohol consumption without an upper bound to this consumption [114,115,122,131].

In one cross-sectional study, a linear relationship between alcohol consumption and cognitive function was found in women but a U-shaped pattern was found in men [109]. One cohort study found that overall, moderate consumption was protective against poor cognitive function, but had an opposite relationship with cognitive function among ApoE4+ individuals [113], while another found that alcohol use in general was related to better cognition without effect modification by ApoE4 status [123]. Slower memory decline with increased alcohol consumption in men was found in one study, though the opposite relationship was found in the case of psychomotor speed among women [118]. The positive association between alcohol intake and memory was also noted in at least one other cross-sectional study for both men and women combined [128]. Moreover, heavy alcohol use was linked to poorer cognitive outcomes in a few studies [87,127,129,130]. Finally, only a few studies among those that were selected found no associations between alcohol consumption and cognitive outcomes [76,77,112].

In fact, 8 out of the 18 selected cohort studies (44%) linking alcohol consumption to the various cognitive outcomes, found the relationship to be in the hypothesized direction (but were U-shaped, J-shaped or linear) in the entire population that was studied and for most outcomes of interest [108,114,116,117,122,124,125,131], while 2 found this relationship for some outcomes but not others [115,120] and 4 detected it for a sub-group of the total population [83,111,113,118]. Moreover, 1 cohort studies have indicated that alcohol use was generally linked to poor cognitive outcomes for the total population [87]. Finally, 3 did not find any significant associations between alcohol consumption and the various cognitive outcomes that were under study [76,77,129]. (See Table 2 and Figure 2A).

9 of the 12 cross-sectional studies (75%) found an association in the hypothesized direction for the entire study population and for most outcomes of interest [106,109,110,119,121,123,126-128]. The remaining 3 studies either found this U-shaped or J-shaped association in a sub-group [107], and either failed to detect any association [112] or detected one that was not in line with the hypothesis, whereby alcohol use was generally found to result in poor cognitive outcomes [130]. (See Table 2 and Figure 2B).

Physical activity

Physical activity has many well-known benefits for preventing a number of chronic disorders, including coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus and osteoporosis. However, its impact on cognitive functioning has not been studied extensively. Several mechanisms may underlie the potentially protective effects of physical activity on cognitive function, including sustained cerebral blood flow [274], improved aerobic capacity and cerebral nutrient supply [275,276] as well as growth factors, specifically the brain-derived neurotropic factor, which is a molecule that increases neuronal survival, enhances learning, and protects against cognitive decline [277,278].

Currently, 24 cohort and 4 cross-sectional studies have examined the hypothesized relationship. For instance, a recent cohort study of 716 dementia-free older adults from the Rush Memory and Aging Project who were followed-up for an average of 4 years found an inverse relationship between total daily physical activity and incident AD after controlling for age, sex, education, self-report physical, social, and cognitive activities, as well as current level of motor function, depressive symptoms, chronic health conditions, and ApoE4 allele status [156]. Furthermore, a recent cross-sectional study of 9344 women, 65 years and older, found a lower prevalence of cognitive impairment among those who reported being physically active versus those who reported being physically inactive at different stages of their lives [155].

These findings suggested that physical activity could represent an important and potent protective factor for cognitive decline and dementia in elderly persons. Significant findings were obtained by other recent cohort [132-145,147,148,150-154,156-158] and cross-sectional studies [100,146,149]. Only one cohort study resulted in non-significant findings [143].

In sum, of the 24 selected cohort studies linking physical activity to the various cognitive outcomes, 21(87.5%) found the relationship in the hypothesized direction in the entire population that was studied and for most outcomes of interest [132,133,135-140,142,144,145,147,148,150-154,156-158,279], while 1 found this relationship in ApoE4 carriers [134] and 1 in non-carriers [141]. In one cohort study, the association was against its hypothesized direction [143]. (See Table 2 and Figure 2A).

In addition, all 4 of the selected cross-sectional studies (100%) found an association in the hypothesized direction for the entire study population and for most outcomes of interest (See Table 2 and Figure 2B).

Nutritional factors

Nutritional factors being studied in relation to cognitive outcomes included caffeine consumpion, antioxidant nutrients and Hcy. In addition, special attention was devoted recently to one class of essential fatty acids, namely n-3 fatty acids.

Caffeine

Caffeine is known to be the most widely used psychoactive drug worldwide. Its main source is coffee particularly in Western diets. Acting as a stimulant of the central nervous system, caffeine causes heightened alertness and arousal [280]. Previous literature yielded inconsistent findings about the effects of caffeine consumption on cognitive processes. In fact, caffeine improved perceptual speed and vigilance, as well as more complex functions such as memory [281]. Caffeine is one type of compound known as methylxanthines whose effects are mainly to block adenosine receptors in the brain, resulting in cholinergic stimulation. It was hypothesized that such stimulation would lead to improved memory [282]. The earliest large cross-sectional study conducted by Jarvis and colleagues found that caffeine improved cognitive performance [159]. Later on, other cross-sectional studies focusing on tea consumption found similar results [100,162,167,170]. Others, however, did not show evidence of a significant protective effect [160,168]. In sum, 4 of 7 selected cross-sectional studies linking caffeine consumption to various cognitive outcomes found the relationship to be in the hypothesized direction in the study population and for most outcomes of interest (57.1%), one found this association in men [100] and two failed to find a significant association [160,168]. (See Table 2 and Figure 2B).

Of 11 cohort studies, positive findings pertained to 3 (27.3%) [163,164,175], though this was found only for coffee intake in two studies [165,169], while 5 recent studies detected this association only among women or for specific exposures [165,169,171-173]. The remaining cohort studies (3 of 11, 27%) did not find an association between caffeine intake and cognitive change [161] or incident dementia [166,174]. Given the paucity of large cohort studies, more research is needed to establish causality (See Table 2 and Figure 2A).

Antioxidants: focus on vitamin E

Several findings suggest that oxidative stress may play an important role in the pathogenesis of AD. First, the brains of AD patients have lesions that are associated with exposure to free radicals. Moreover, oxidative stress among these patients is also marked by an increased level of antioxidants in the brain that act as free radical scavengers. Finally, in vitro studies suggest that exogenous antioxidants may reduce the toxicity of β-amyloids in the brains of AD patients [283-285]. Based on these findings, it may be hypothesized that dietary antioxidants may help reduce the risk of AD.

Those epidemiologic studies examined the longitudinal relationship between supplemental antioxidants and risk of AD and other dementias found conflicting results: While vitamin C supplement use was related to lower AD risk in one cohort study [178], combined supplementation of vitamin E and vitamin C was associated with reduced prevalence and incidence of AD and cognitive decline in three other cohort studies [189,193,198], whereas another study found this effect to be specific to Vitamin E supplements [186]. These findings of a protective effect of supplemental antioxidant use against cognitive impairment and decline was replicated in a large cohort study [185]. However, there were only borderline or little evidence of a cognitive benefit from use of antioxidant supplements, particularly vitamins C and E, according to at least five independent cohort studies [177,180,187,192,199].

There are several prospective cohort studies on the effect of dietary antioxidants on the risk of dementia. One study found that high dietary intake of vitamins C and E may reduce the risk of AD [182] with the relationship most pronounced among smokers. Morris and colleagues [183] found that dietary intake of vitamin E, but not other antioxidants, was associated with a reduced risk of incident AD, although this association was restricted to individuals without the Apolipoprotein E ϵ4 genotype. Similar findings were reported with cognitive decline as an outcome [184]. In a later study when both outcomes were considered it was concluded that certain forms of tocopherols not found in dietary supplements but found only in foods may be at play [194]. This observation was corroborated by at least one recent study [197]. Another study, however, suggested that dietary antioxidants were not able to reduce AD risk [187]. Similarly, Laurin and colleagues [188] found no association between midlife dietary intake of vitamins E and C and dementia incidence. At least five other cohort studies came to a similar conclusion [176,181,201,202]. In addition to examining associations of cognition with vitamins C and E, other studies found that carotenoids, particularly β-carotene intake, may be have beneficial effects of various cognitive outcomes [176], though others were not able to detect such an association [184,201,202].

Irrespective of the source of antioxidants, plasma concentration may be a good biomarker for oxidative stress status. In particular, an inverse association between plasma vitamin E among others and poor cognitive outcomes was found in at least two cross-sectional studies [179,190] and two cohort studies [196,200]. Another cross-sectional study, however, did not find evidence of an association between plasma antioxidants, including vitamin E and prevalent AD [191]. In addition, among studies that examined the influence of plasma carotenoids [179,195], only one detected a significant potential protective effect against cognitive impairment [195]. While these results are mixed, they suggest that at least one antioxidant has a protective effect against adverse cognitive outcomes.