Abstract

A single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) method has been developed to observe the activation of the small G protein Ras at the level of individual molecules. KB cells expressing H- or K-Ras fused with YFP (donor) were microinjected with the fluorescent GTP analogue BodipyTR-GTP (acceptor), and the epidermal growth factor-induced binding of BodipyTR-GTP to YFP-(H or K)-Ras was monitored by single-molecule FRET. On activation, Ras diffusion was greatly suppressed/immobilized, suggesting the formation of large, activated Ras-signaling complexes. These complexes may work as platforms for transducing the Ras signal to effector molecules, further suggesting that Ras signal transduction requires more than simple collisions with effector molecules. GAP334-GFP recruited to the membrane was also stationary, suggesting its binding to the signaling complex. The single-molecules FRET method developed here provides a powerful technique to study the signal-transduction mechanisms of various G proteins.

The small G protein Ras, an oncogene product, works as a binary switch in many important intracellular signaling pathways (1, 2) and, therefore, has been one of the focal targets of signal-transduction investigations and drug development. However, the mechanism by which Ras transduces the signal to the downstream effector molecules has remained elusive. For example, the effector molecule Raf-1 kinase is activated by Ras, but how this activation occurs is unknown, although a dimerization mechanism through Ras dimers and other protein factors has been proposed (3). Caveolae/rafts (4-8) and scaffolding proteins for activated Ras, such as SUR-8 (9), Spred (10), and Galectin-1 (8), may be involved in signal transduction. Regarding Raf activation, the further involvement of Raf-scaffolding proteins, such as KSR and 14-3-3, has been suspected (11, 12). Despite these intensive efforts to understand the signal-transduction mechanism from Ras to its effector molecules, the means by which these scaffolding proteins, specialized membrane domains, and oligomerization processes are involved, selected, and orchestrated for the activation of the Ras effector molecules have remained unknown.

To facilitate approaches to this difficult but important problem, in this research, we have developed a method to visualize the activation of single individual molecules of Ras and the behavior of activated Ras molecules at video rate. Such a single-molecule method would allow direct investigations of the interaction of activated Ras with its effector and scaffolding proteins and its localization in specialized domains, which would provide valuable information for understanding the signal-transduction mechanism after Ras becomes activated. The activation of single Ras molecules was visualized by using single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) (13-15). This method enabled us to detect the slowing and immobilization of activated Ras, which suggests the cooperative formation of large, activated Ras-signaling complexes for signal transduction, rather than simple collisional mechanisms. Previously, Mochizuki et al. (16) developed a method to detect Ras activation by using CFP and YFP, but because single molecules of CFP are not detectable by the available technology (A.K., unpublished observations), this FRET probe cannot be used for single-molecule studies.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Transfection. Plasmid preparations are described in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. KB cells were transfected by using LipofectAMINE Plus (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) with each expression plasmid. The cells stably expressing YFPH-Ras molecules were selected with 0.3 mg/ml G418, and positive clones were picked up with micropipettes. Cells cultured without FBS for at least 12 h before epidermal growth factor (EGF) stimulation were microinjected with 2 mM BodipyTRGTP, with an Eppendorf Microinjection System. About 3 min after the microinjection, the single-molecule fluorescence observation was initiated. Cells were then stimulated with 20 nM EGF. The pull-down assay for Ras activation (17, 18) and evaluation of EGF receptor phosphorylation (19) were carried out as described. Treatment of the cells with 1 μM latrunculin B was carried out under the microscope at 37°C, and the single-molecule observation was started 2 min after the addition of latrunculin B and completed within 5 min.

Single-Molecule Fluorescence and FRET Observations. An objective-lens-type total internal reflection fluorescence microscope were built on an Olympus inverted microscope (IX-70) as described (20). The fluorescence images of YFP and BodipyTR were separated by a dichroic mirror (600 nm), and projected into two detection arms with bandpass filters (500-570 nm for YFP and 605-700 nm for BodipyTR, Chroma Technology, Brattleboro, VT). A microchannel plate intensifier (VS4-1845, VideoScope, Sterling, VA), and a silicon-intensified target tube camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan) were used in each arm. Bulk fluorimetric detection of FRET from YFP-HRas to BodipyTR-GTP is described in Supporting Text.

Results and Discussion

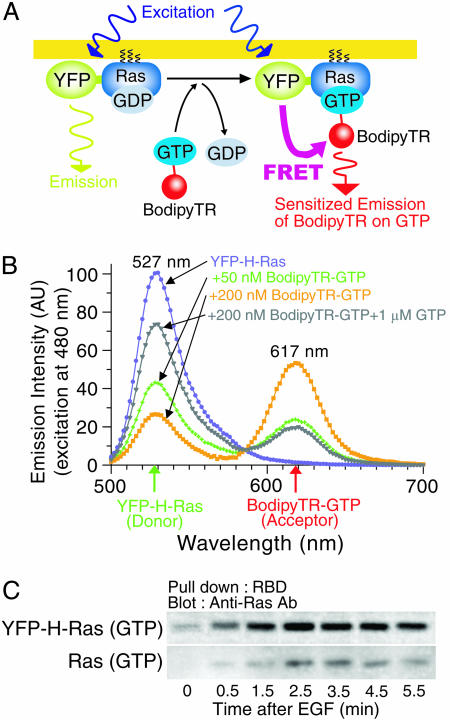

FRET Strategy for Detecting the Activation of Single Molecules of H-Ras. To visualize the instances of activation of single individual Ras molecules, we observed GTP binding to Ras by using a single-molecule FRET technique (Fig. 1A). First, KB (human epidermoid mouth carcinoma) cells stably expressing YFP-HRas were microinjected with the GTP conjugated with a fluorescent tag, BodipyTR (BodipyTR-GTP) (21, 22). We then stimulated these cells with 20 nM EGF, which should lead to the release of prebound GDP from Ras and the binding of BodipyTR-GTP to the Ras molecule. This binding may induce FRET from the YFP on Ras to the BodipyTR conjugated to GTP; that is, when YFP is excited with a 488-nm line from an argon ion laser, the sensitized emission of BodipyTR, because of energy transfer from YFP, may be observed. Thus Ras activation, i.e., GTP binding, may be detected as the appearance of a sensitized emission spot of BodipyTR-GTP at the place superimposable with the YFP-H-Ras spot, which would be dimmed on the appearance of the BodipyTR spot.

Fig. 1.

Strategy for detecting activation of individual single Ras molecules by GTP binding by using a single-molecule FRET technique. (A) Schematic drawing of the experimental design. See the text for details. (B) FRET from purified YFP-H-Ras (expressed in E. coli, 100 nM, fixed concentration for all experiments) to BodipyTR-GTP can be detected in vitro by bulk spectrofluorimetry. YFP-H-Ras was loaded with various concentrations of BodipyTR-GTP (0, 50, and 200 nM), and the emission spectra were recorded with excitation at 480 nm. The addition of 1 μM nonlabeled GTP decreased the FRET efficiency, indicating that BodipyTR-GTP binds to the GTP site on YFP-H-Ras. The spectra were corrected for direct excitation of the BodipyTR fluorophore by acquiring its spectra in the absence of YFP-H-Ras (in 200 nM BodipyTR-GTP, 5-10% of the signal came from directly activated YFP-H-Ras). The distance between the YFP chromophore and BodipyTR on YFP-H-Ras was estimated to be ≈3-5 nm, based on crystallographic data (32, 33). (C) YFP-H-Ras expressed in KB cells can be activated in the same time course as endogenous Ras after EGF stimulation, as shown by a biochemical pull-down assay.

In Vitro FRET Observations. This in vivo single-molecule experimental design was first tested in vitro by using bulk spectrofluorimetry. YFP-H-Ras (donor) expressed in Escherichia coli was purified and mixed with various concentrations of BodipyTRGTP (acceptor), and the occurrence of FRET was examined (Fig. 1B). With an increase in the BodipyTR-GTP concentration, the sensitized emission of BodipyTR due to FRET from YFP increased, indicating that FRET is a sensitive way to detect BodipyTR-GTP binding to YFP-H-Ras. This result also suggests that H-Ras could be activated even after YFP fusion. This finding was further confirmed by a pull-down assay, with use of the Ras-binding domain of Raf-1 kinase. The YFP-H-Ras activation after EGF stimulation took place in a time course very similar to that of endogenous Ras, suggesting that the fusion protein is activated in living KB cells.

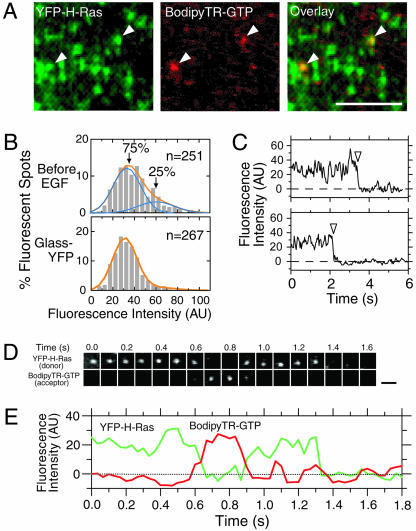

Observation of Single YFP-H-Ras Molecules on the Plasma Membrane. Single fluorescent molecules were observed by an objective lens-type total internal reflection fluorescence microscope at video rate (33-ms resolution) (20). Both YFP and BodipyTR were observed simultaneously, with two video cameras working synchronously on the two observation arms of the fluorescence microscope (at video rate, 33 ms/frame). YFP-H-Ras expressed in KB cells (Fig. 2A Left) exhibited a fluorescence intensity distribution with two peaks (Fig. 2B); 75% of the spots exhibited the distribution similar to single molecules of purified YFP (YFP was expressed in E. coli and then purified) nonspecifically adsorbed on the coverslip, whereas the remaining 25% of the YFP-H-Ras spots had higher intensities. The latter spots may represent YFP-H-Ras in clusters, microdomains (8), or an incidental proximity. The majority of the YFP-H-Ras spots with single YFP intensities were photobleached in a single step (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Activation of single H-Ras molecules, monitored by single-molecule FRET from YFP-H-Ras to BodipyTR-GTP on their binding. (A) Single-molecule FRET observations with simultaneous imaging in the YFP (Left) and BodipyTR (Center) channels. Single frames (33 ms) in the video-rate recordings are shown. Excitation was at 488 nm with an Ar+ laser beam. The fluorescent spots shown in the BodipyTR channel appeared as a result of FRET from YFP on Ras to BodipyTR on GTP (arrows). (Scale bar = 5 μm.) The 488-nm beam could also directly excite the BodipyTR-GTP acceptor, but the efficiency of direct excitation was so low that the signal from individual molecules could not form identifiable spots in the presence of the background noise (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The fluorescent spots in the figure may look aggregated in some areas, but their separations are rather clear in the original tape (see Movie 2). BodipyTR-GTP, despite its low concentration (≈40 nM), became bound to YFP-H-Ras, competing with ≈1 mM endogenous GTP (34). This finding suggests that BodipyTR-GTP may be locally concentrated near the membrane, perhaps because of the hydrophobic BodipyTR group. (B) Distributions of fluorescence intensities of YFP-H-Ras expressed in KB cells before EGF addition (Upper) and purified YFP adsorbed on the coverslip (Lower). Signal intensities of 800 × 800 nm areas (8-bit images in an area of 8 × 8 pixels) containing a single spot were measured. The background intensity of the spot estimated in adjacent areas was always subtracted. The distribution for YFP on the glass (bottom) could be fitted well with a single Gaussian function (orange line), whereas that for YFP-H-Ras expressed in the plasma membrane of KB cells could be fitted with the sum of two Gaussian functions. (C) Typical examples of single-step photobleaching of YFP-H-Ras spots (arrows), suggesting that these spots included a single YFPH-Ras molecule. (D) Images of single molecules of YFP-H-Ras (donor) and BodipyTR-GTP (acceptor) undergoing FRET. Note that the timescales for D and E are the same. (Scale bar = 0.5 μm.) The original video data for this figure is shown in Movie 1. For another type of the FRET sequence, see Fig. 8 and Movie 3.(E) Fluorescence intensities of the spots displayed in D plotted as a function of time: a representative example of the anticorrelation between the donor and the acceptor fluorescence intensities.

Visualizing the Activation of Single Molecules of H-Ras in Living Cells. The occurrence of FRET from YFP-H-Ras to BodipyTR-GTP in live cells was examined by exciting YFP by using a 488-nm laser line (Fig. 2 A). Within ≈30 s after stimulation with 20 nM EGF, BodipyTR-GTP spots undergoing sensitized emission started appearing on the plasma membrane, exactly at the places where the YFP-H-Ras spots had been observed, and they remained superimposable as long as the BodipyTR signal was visible (Fig. 2 A and D; see Movie 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Fig. 2E shows the time-dependent changes in the fluorescence intensities of the YFPH-Ras (energy donor) spot and the BodipyTR-GTP (acceptor) spot excited by FRET from YFP-H-Ras (the images shown in Fig. 2D). In the time code shown in Fig. 2 D and E, at 0.6 s, a BodipyTR-GTP spot started appearing at the place superimposable with the preexisting YFP-H-Ras spot, and, as the YFP-H-Ras spot dimmed, the sensitized fluorescence spot of BodipyTR-GTP became brighter. At ≈0.9 s, the BodipyTRGTP molecule was photobleached or released from the YFPH-Ras with the concomitant recovery of the fluorescent intensity of the YFP-H-Ras donor molecule, until it also was photobleached at ≈1.3 s (for another type of sequence of event, see Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The single-molecule FRET results for YFP-K-Ras were very similar to those for YFP-H-Ras.

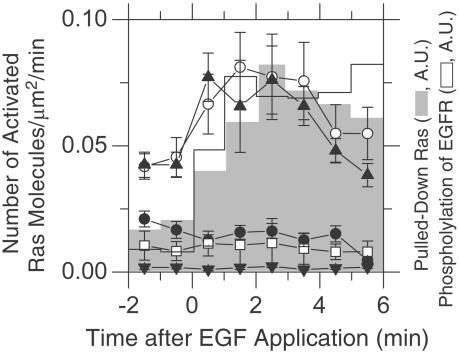

Time-Dependent Changes in the Number of Activated Ras Molecules. The number of YFP-(H or K)-Ras/BodipyTR-GTP molecular pairs undergoing single-molecule FRET begins to increase at 0.5 min after EGF stimulation, peaks at 1.5-3.5 min, and then decreases (Fig. 3, the scale on the left). In general, this time course agrees with the bulk biochemical pull-down assay results by using the Ras-binding domain of Raf-1 kinase (Fig. 3, the scale on the right; also see Fig. 1C), whereas the phosphorylation level of EGF receptor rises and peaks slightly earlier. Basal activation of YFP-Ras before EGF stimulation may reflect the nucleotide exchange occurring at the steady state. The dominant negative YFP-H-Ras-N17 molecules (23, 24) expressed in KB cells hardly exhibited FRET, as expected (Fig. 3). Furthermore, FRET was hardly detectable with the constitutively active YFP-H-Ras-V12, probably because the nucleotide exchange on V12-Ras may be very slow because of its impaired GTPase activity (25).

Fig. 3.

Time courses of Ras activation: comparison between the single-molecule assay and the bulk biochemical assay, and among different Ras mutants. The number density of single-molecule pairs of YFP-H-Ras and BodipyTR-GTP undergoing FRET (μm2/min) plotted as a function of time after EGF stimulation (open circles, average of 27 cells in four independent experiments; the error bars represent standard errors). The number of activated YFP-H-Ras molecules already started increasing at 30 s after EGF stimulation, peaked between 1.5 and 3.5 min, and then decreased. The activation time course of YFP-K-Ras (closed triangles, average of six cells) is similar to that of YFP-H-Ras. The time course of single-molecule activation of YFP-(H or K)-Ras, as determined by single-molecule FRET, is similar to that of the activation of endogenous Ras, as determined by the bulk pull-down assay (gray bars, the scale on the right). The level of EGF receptor phosphorylation increases slightly earlier than Ras activation (open bars, the scale on the right). The N17 dominant negative YFP-H-Ras exhibited no increase in the FRET frequency after EGF stimulation (closed circles, average of 16 cells in three independent experiments). The V12 constitutively active YFP-H-Ras did not show significant levels of FRET occurrences both before and after EGF stimulation (open boxes, average of eight cells in two independent experiments), probably because the exchange rate of bound GTP with BodipyTR-GTP is slow. As a control, KB cells expressing YFP-H-Ras were microinjected with BodipyTR (without GTP), and they hardly exhibited any occurrences of FRET, providing the baseline in these single-molecule FRET experiments (closed inverse triangles, average of seven cells).

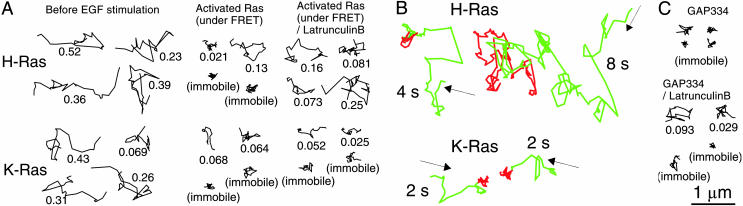

Ras Diffusion Slows on Activation. Fig. 4A shows typical trajectories of YFP-H-Ras on the cell membrane (see Supporting Text for the definition of “typical” trajectories). Before EGF stimulation, a large majority of the H-Ras molecules diffuse rapidly (Fig. 4A Left; see Movie 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) (17, 26), as fast as phospholipids. In contrast, the activated Ras molecules, which could be tracked by following both the donor and the FRET signals, exhibited trajectories indicating that their diffusion is substantially slowed or blocked (Fig. 4 A Center and B; also see Movie 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 4.

Representative Ras and p120RasGAP trajectories, indicating that Ras molecules become largely immobile on activation. (A) Typical 1-s trajectories of single YFP-(H and K)-Ras molecules (Upper and Lower, respectively) on the cell membrane recorded at video rate (for the definition of “typical” trajectories, see Supporting Text). The numbers represent D100ms. (Left) Before EGF stimulation (inactive YFP-Ras). (Center) Typical trajectories of activated Ras molecules, i.e., those of single-molecule pairs of YFP-(H or K)-Ras and BodipyTR-GTP undergoing FRET. (Right) Typical trajectories of single FRET pairs after partial depolymerization of actin filaments with 1 μM latrunculin B for 2-5 min, which blocked the immobilization of activated YFP-H-Ras but not activated YFP-K-Ras. (B) Representative trajectories of single YFP-Ras (donor, green) molecules, which later became activated by the binding of BodipyTR-GTP, as detected by the FRET signal (red). During the occurrence of FRET, the donor signal became very weak, and therefore the YFP-(H or K)-Ras trajectory shown in green is connected with the red trajectory of the sensitized emission spot of BodipyTR-GTP. YFP-Ras diffusion is substantially blocked or slowed during FRET periods. (C) Typical 1-s trajectories of single GAP334-GFP molecules recruited to the cell membrane, recorded at video rate. In a time course similar to H- and K-Ras activation (Fig. 3; also see Fig. 6C), GAP334-GFP molecules were recruited to the cell membrane, where they hardly exhibited diffusion. In contrast, mild treatment with 1 μM latrunculin B for 2-5 min decreased the immobile fraction of GAP334-GFP.

For a quantitative analysis of the mode and the rate of diffusion, we first classified the trajectories into mobile and immobile modes, based on the mean-square displacement of the fluorescent spot for 200 ms (MSD200ms) obtained from a 330-ms trajectory [the spots exhibiting MSD200ms < 0.018 μm2 were classified into the “immobile” mode, which was determined as the 95 percentile point by Gaussian fitting of MSD200ms of YFP nonspecifically adsorbed on the coverslip; see Fig. 5, fifth box (27)], and then for the spots exhibiting MSD200ms over 0.018 μm2 (including all noises, “mobile” mode) (see Fig. 5, fifth box), we evaluated their diffusion coefficients in a time window of 100 ms, D100ms (27). These mobile molecules all undergo (apparent) simple Brownian diffusion in this time window (28), and it is characterized by D100ms.

Fig. 5.

Quantitative analysis showed slowing/immobilization of activated Ras diffusion. Histograms show the distributions of the MSD200ms obtained from a 330-ms trajectory. Activated H-Ras and GAP334 were observed 2-3 min after EGF stimulation. The spots exhibiting MSD200ms <0.018 μm2 were classified into the immobilized component [indicated by the yellow region determined from the Gaussian fitting to the data on YFP on glass (immobile YFP) as a 95 percentile point]. For the fluorescent spots exhibiting MSD200ms over 0.018 μm2 (mobile spots), the distribution of the diffusion coefficient in the time window of 100 ms (D100ms) is shown. Because single fluorophores yield only dim signals, the determination of D100ms for a single trajectory requires sufficient averaging over that trajectory. However, single fluorescent molecules are photobleached quickly under the conditions of single-molecule detection, causing insufficient averaging. This problem becomes more serious as diffusion is slowed, because discriminating diffusion from noise becomes increasingly more difficult (see Supporting Text). Therefore, as a convenient measure for the diffusion rate and immobilization, we used MSD200ms. Most single YFP molecules fixed on coverslips showed MSD200ms values distributed in the range between 5.5 × 10-4 to 3.1 × 10-2 μm2, with a median value of 4.8 × 10-3 μm2 (left fifth box). For K-Ras data, see Fig. 9.

In the cells at the resting (steady) state before EGF stimulation, the distribution of MSD200ms (Fig. 5, first box) indicates that only ≈9 (16)% of the YFP-H-Ras (K-Ras) molecules are immobile (see Fig. 9. which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, for K-Ras data). Among the mobile YFP-H-Ras molecules, >90% exhibited rapid diffusion similar to that of a non-raft phospholipid DOPE (28). This result suggests that the H-Ras molecules may make only temporary (perhaps <100 ms, which is our time window here) interactions with caveolae or large and stable rafts (4-8), if they interact with these structures at all in the steady-state resting cells. This finding is consistent with the discussion advanced by Prior et al. (7, 8), who argued that the partitioning of Ras molecules into rafts may be very dynamic, with Ras entering and exiting the rafts rapidly. Partial depolymerization of actin filaments by mild latrunculin B treatment did not affect the amount of the immobile fraction of YFP-(H and K)-Ras, as shown in Fig. 5 (first box). However, the D100ms for the mobile component was either increased (H-Ras) or decreased (K-Ras). The interpretation of these results is complicated, as described in Supporting Text (higher affinity of K-Ras to actin and actin aggregates).

Activated H- and K-Ras molecules undergoing FRET after EGF application exhibited substantial slowing/immobilization (Fig. 5, second boxes). About half of the activated Ras molecules (observed between 1 and 3 min after EGF stimulation) became immobilized. The remaining half of activated Ras molecules were classified into the mobile mode, but their diffusion rates were decreased by a factor of 3 to 4 from those before EGF application (Fig. 5, compare the first and second boxes on the right).

Partial depolymerization of actin filaments by latrunculin B treatment substantially inhibited the activation-induced immobilization (MSD200ms) and slowing of YFP-H-Ras (D100ms), as shown in Fig. 4A Right and Fig. 5 (second boxes), suggesting the involvement of filamentous actin in the immobilization of YFPH-Ras. However, in the case of YFP-K-Ras, the slowing and immobilization were not blocked by the same latrunculin B treatment. What causes this difference between H- and K-Ras is unknown. (Our hypothesis to explain the results with K-Ras is that K-Ras has a tendency to transiently associates with actin and/or actin aggregates. See Supporting Text.). It is possible that K-Ras molecules tend to be trapped in the microaggregates of actin after latrunculin B treatment (29). Actin depolymerization under the conditions used here did not affect Ras activation, as observed by a pull-down assay with the Ras-binding domain of Raf-1 (data not shown). Cholesterol depletion with MβCD did not block the immobilization of either YFP-(H or K)-Ras (Fig. 5, third boxes), suggesting that the cholesterol-enriched raft domains (30) may not be involved in slowing the diffusion of activated H- and K-Ras.

Under the FRET observation conditions, the lifetime (t1/e) of YFP due to photobleaching was ≈1 s, and, therefore, the majority of YFP-H-Ras that exhibited FRET (activation) and immobilization became photobleached during the FRET period (Fig. 4B). Therefore, these results cannot predict what may happen several seconds after the FRET (Ras activation) was initiated. However, because the constitutively active V12Ras molecules (both H and K) exhibited alternating immobile (≈20%) and mobile (≈80%) periods, each lasting mostly 1 s or less (data not shown), we expect that the immobilized (activated, wild-type) Ras molecules would soon resume rapid diffusion. This expectation is consistent with the report by Niv et al. (17), who found that the diffusion coefficient for the constitutively active V12Ras was only slightly reduced from that for the wild-type Ras, for observation periods typically >10 s (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments).

A Model for the Formation of the Active Ras Signal-Transduction Complex. Based on these observations, we propose a model in which activated Ras molecules may be bound by activated Ras-specific scaffolding proteins, like SUR-8 (9), spred (10), and galectin-1 (8), which might initiate the cooperative formation of transient signaling complexes including the effector molecules, like Raf-1, and deactivating proteins for Ras, like RasGAP (Fig. 6A). The formation of such a large signaling complex on the plasma membrane would induce its trapping in and/or binding to the actin-based membrane skeleton mesh, as proposed (20, 28, 31); binding enhanced by the avidity effect of molecular complexes, and corralling enhanced by the increased size on the formation of molecular complexes. [The “fence” effect of the membrane skeleton on the cytoplasmic proteins (31) and the “picket” effect of various transmembrane proteins anchored to the membrane skeleton on the lipid part of Ras (28) would contribute to corralling.]

Fig. 6.

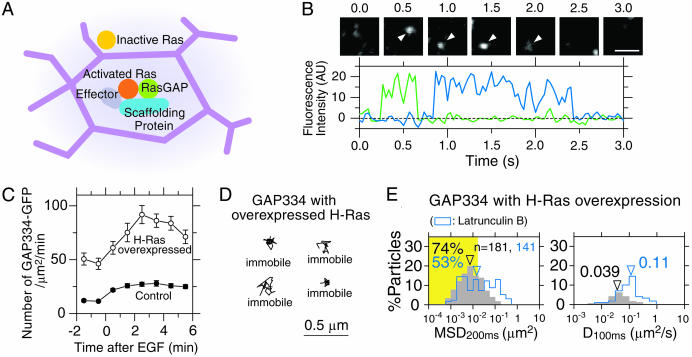

GAP334 molecules recruited to the membrane after EGF stimulation were stationary, consistent with a model for the formation of the transient signaling complex of activated Ras on the plasma membrane corralled by or bound to the actin-based membrane skeleton (MSK) mesh. (A) A model for the formation of the activated Ras-signaling complex. Right after a Ras molecule is activated in the compartment where the receptor is located (the pink compartment), a signaling complex of activated Ras may be formed by the interaction with a scaffolding protein, downstream effector molecules, and RasGAP. When an H-Ras-signaling complex is formed, it may be anchored to the MSK or confined in the MSK mesh, becoming temporarily immobilized. Thus, the signal transfer to a downstream molecule may take place during the temporary immobilization in the same compartment that received the extracellular signal, maintaining the spatial information. (B) Images of single molecules of GAP334-GFP and their fluorescence intensities. GAP334-GFP molecules are recruited to the plasma membrane at ≈0.25 s (green line) and 0.9 s (blue line) after EGF stimulation, and most of them are immobile (arrowheads). At ≈0.6 s (green line) and 2.4 s (blue line), the GAP334-GFP molecules were either photobleached or dissociated from the membrane. (Scale bar = 1 μm.) (C) The number density of GAP334-GFP (μm2/min) recruited to the plasma membrane plotted as a function of time after EGF stimulation (closed circles, average of five cells; the error bars represent the standard errors). Overexpression of (myc-) H-Ras (four times more than endogenous Ras) greatly increased the number of recruited RasGAP-YFP molecules (open circles, average of five cells; the error bars represent standard errors). (D) Even after H-Ras was overexpressed by a factor of ≈4, the p120RasGAP-YFP molecules were still stationary. (E) The histograms of MSD200ms and D100ms for GAP334-GFP 2-3 min after EGF stimulation when H-Ras was overexpressed. Although the number of recruited GAP334-GFP molecules was increased by a factor of ≈4, most of the recruited GAP334-GFP molecules were still stationary, suggesting that activated Ras is stationary and responsible for the immobilization of p120RasGAP.

Recruitment of GAP334, the Ras-Binding, Catalytic Domain of p120RasGAP, on the Cell Membrane. To test the model for the formation of the transient signaling complex of activated Ras and the subsequent confinement within and/or binding to the membrane-skeleton mesh, the recruitment and movement of GAP334 [the catalytic domain of p120RasGAP that binds to activated Ras (see Supporting Text)] on the plasma membrane was examined. GAP334, which is normally in the cytoplasm, binds to activated Ras on the plasma membrane and greatly accelerates the hydrolysis of the GTP molecule bound to Ras for its deactivation. As expected, individual GAP334-GFP molecules suddenly appear on the membrane from the cytoplasm after EGF stimulation (Fig. 6B and see Movie 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The number of GAP334-GFP molecules recruited to the cell membrane increases 0.5-2 min after EGF stimulation (Fig. 6C). The recruitment of GAP334-GFP was also detectable before EGF stimulation, probably because of the existence of Ras-GTP (activated Ras) even at the steady state (Figs. 1D and 3; note that these GAP334-GFP molecules are also immobile, consistent with the binding to activated Ras present before EGF stimulation). Representative trajectories of GAP334-GFP on the membrane (Fig. 4C and Movie 4) and a quantitative analysis (Fig. 5, the fourth boxes) indicated that the majority of GAP334-GFP recruited to the plasma membrane is rather stationary, consistent with activated Ras being corralled or bound by the membrane skeleton mesh. Latrunculin treatment mobilized GAP334-GFP without affecting the recruitment of GAP334-GFP to the cell membrane. These results are consistent with the model in which the activated, Ras-induced signaling complex is confined in and/or bound to the membrane-skeleton mesh.

Overexpression of H-Ras (≈4-fold more than endogenous Ras) increased the number of recruited GAP334-GFP molecules to the plasma membrane by a factor of ≈4 (Fig. 6C), and the majority of the recruited GAP334-GFP molecules were stationary (Fig. 6 D and E). These results indicate that Ras is indeed responsible for the immobilization of RasGAP on the plasma membrane.

In summary, we succeeded in observing the activation of single Ras molecules by using single-molecule FRET and found that the activated Ras molecules (perhaps temporarily) become immobile in the plasma membrane. Such immobilization may be induced by the formation of a signaling complex, including activated Ras. RasGAP may further be recruited to this complex, thus deactivating the activated Ras and leading to the disintegration of the complex. Furthermore, such a complex might include more than one Ras molecule (3).

The single-molecule FRET method to detect the binding of BodipyTR-GTP to a G protein fused with YFP in real time is a useful technique to study the activation and dynamics of activated G proteins, and it can be applied to many other G proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Kusumi laboratory for their helpful discussions.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviationas: FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; MSD200ms, mean-square displacement of the fluorescent spot for 200 ms; EGF, epidermal growth factor.

References

- 1.Satoh, T., Nakafuku, M. & Kaziro, Y. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 24149-24152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rebollo, A. & Martinez, A. C. (1999) Blood 94, 2971-2980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inouye, K., Mizutani, S., Koide, H. & Kaziro, Y. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 3737-3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mineo, C., James, G. L., Smart, E. J. & Anderson, R. G. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 11930-11935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu, C., Butz, S., Ying, Y. & Anderson, R. G. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 3554-3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roy, S., Luetterforst, R., Harding, A., Apolloni, A., Etheridge, M., Stang, E., Rolls, B., Hancock, J. F. & Parton, R. G. (1999) Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 98-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prior, I. A., Harding, A., Yan, J., Sluimer, J., Parton, R. G. & Hancock, J. F. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 368-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prior, I. A., Muncke, C., Parton, R. G. & Hancock, J. F. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 160, 165-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li, W., Han, M. & Guan, K. L. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 895-900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakioka, T., Sasaki, A., Kato, R., Shouda, T., Matsumoto, A., Miyoshi, K., Tsuneoka, M., Komiya, S., Baron, R. & Yoshimura, A. (2001) Nature 412, 647-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matheny, S. A., Chen, C., Kortum, R. L., Razidlo, G. L., Lewis, R. E. & White, M. A. (2004) Nature 427, 256-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzivion, G., Luo, Z. & Avruch, J. (1998) Nature 394, 88-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ha, T., Enderle, T., Ogletree, D. F., Chemla, D. S., Selvin, P. R. & Weiss, S. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 6264-6268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sako, Y., Minoghchi, S. & Yanagida, T. (2000) Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 168-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deniz, A. A., Laurence, T. A., Dahan, M., Chemla, D. S., Schultz, P. G. & Weiss, S. (2001) Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 52, 233-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mochizuki, N., Yamashita, S., Kurokawa, K., Ohba, Y., Nagai, T., Miyawaki, A. & Matsuda, M. (2001) Nature 411, 1065-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niv, H., Gutman, O., Kloog, Y. & Henis, Y. I. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 157, 865-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Rooij, J. & Bos, J. L. (1997) Oncogene 14, 623-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riese, D. J., II, Bermingham, Y., van Raaij, T. M., Buckley, S., Plowman, G. D. & Stern, D. F. (1996) Oncogene 12, 345-353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iino, R., Koyama, I. & Kusumi, A. (2001) Biophys. J. 80, 2667-2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Draganescu, A., Hodawadekar, S. C., Gee, K. R. & Brenner, C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4555-4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McEwen, D., Gee, K., Kang, H. & Neubig, R. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 291, 109-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.John, J., Rensland, H., Schlichting, I., Vetter, I., Borasio, G. D., Goody, R. S. & Wittinghofer, A. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 923-929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feig, L. A. & Cooper, G. M. (1988) Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 3235-3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.John, J., Frech, M. & Wittinghofer, A. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 11792-11799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niv, H., Gutman, O., Henis, Y. I. & Kloog, Y. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 1606-1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakada, C., Ritchie, K., Oba, Y., Nakamura, M., Hotta, Y., Iino, R., Kasai, R., Yamaguchi, K., Fujiwara, T. & Kusumi, A. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 626-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujiwara, T., Ritchie, K., Murakoshi, H., Jacobson, K. & Kusumi, A. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 157, 1071-1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sako, Y. & Kusumi, A. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 125, 1251-1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simons, K. & Ikonen, E. (1997) Nature 387, 569-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kusumi, A. & Sako, Y. (1996) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 8, 566-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ormo, M., Cubitt, A. B., Kallio, K., Gross, L. A., Tsien, R. Y. & Remington, S. J. (1996) Science 273, 1392-1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krengel, U., Schlichting, L., Scherer, A., Schumann, R., Frech, M., John, J., Kabsch, W., Pai, E. F. & Wittinghofer, A. (1990) Cell 62, 539-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gamberucci, A., Innocenti, B., Fulceri, R., Banhegyi, G., Giunti, R., Pozzan, T. & Benedetti, A. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 23597-23602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.