Abstract

Noonan syndrome is a common genetic disorder that causes multiple congenital abnormalities and a large number of potential health conditions. Most affected individuals have characteristic facial features that evolve with age; a broad, webbed neck; increased bleeding tendency; and a high incidence of congenital heart disease, failure to thrive, short stature, feeding difficulties, sternal deformity, renal malformation, pubertal delay, cryptorchidism, developmental or behavioral problems, vision problems, hearing loss, and lymphedema. Familial recurrence is consistent with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance, but most cases are due to de novo mutations. Diagnosis can be made on the basis of clinical features, but may be missed in mildly affected patients. Molecular genetic testing can confirm diagnosis in 70% of cases and has important implications for genetic counseling and management. Most patients with Noonan syndrome are intellectually normal as adults, but some may require multidisciplinary evaluation and regular follow-up care. Age-based Noonan syndrome–specific growth charts and treatment guidelines are available.

Noonan syndrome is a common genetic disorder with multiple congenital abnormalities. It is characterized by congenital heart disease, short stature, a broad and webbed neck, sternal deformity, variable degree of developmental delay, cryptor-chidism, increased bleeding tendency, and characteristic facial features that evolve with age. Molecular genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis in most cases, which has important implications for genetic counseling and management. Physicians should know how to diagnose Noonan syndrome because patients who have it require monitoring for a large number of potential health conditions. Age-appropriate guidelines for the management of Noonan syndrome are available.1

Epidemiology

Noonan syndrome is characterized by marked variable expressivity, which makes it difficult to identify mildly affected individuals. The incidence is one in 1,000 to 2,500 live births for severe phenotype, but mild cases may be as common as one in 100 live births.2 Familial recurrence is consistent with an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance, but de novo mutations are more common, accounting for 60% of cases.3 There is no known predilection by race or sex.

Clinical Presentation

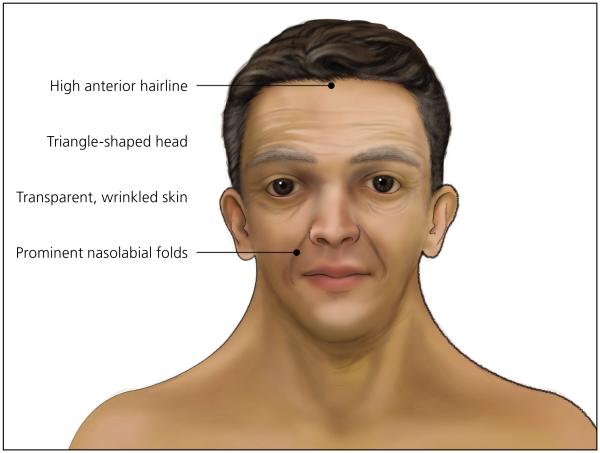

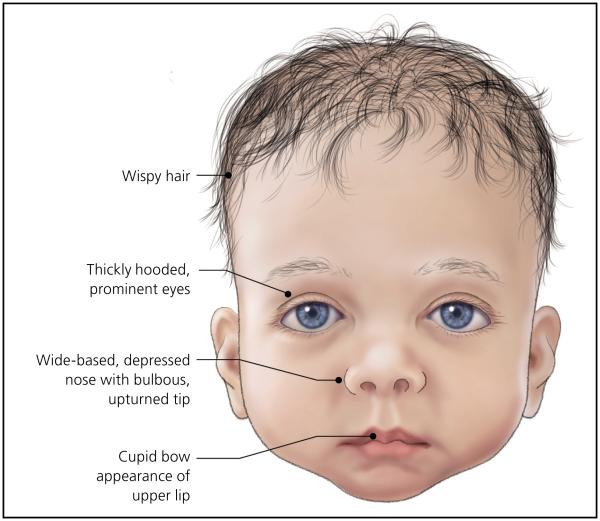

The diagnosis of Noonan syndrome depends primarily on the identification of characteristic clinical features (Table 11-11). The clinical spectrum in children is well described, but few studies have examined medical complications in adults.3 Figures 1 through 4 show the cardinal phenotypic features of Noonan syndrome based on patient age.6-8

Table 1.

Clinical Features of Noonan Syndrome

|

Cardiovascular4,5

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Pulmonary stenosis, often with a dysplastic valve Dental/oral1,2 Articulation difficulty High arched palate Malocclusion Micrognathia Dysmorphic facial features6,7 See Figures 1 through 4 Ears8 Hearing loss Eyes2,9 Anterior segment problems (prominent corneal nerves, cataract, anterior stromal dystrophy) Nystagmus Ptosis, hypertelorism, and epicanthal folds Refractive error Strabismus Gastrointestinal3,4 Feeding difficulties (poor sucking function, prolonged feeding time, recurrent vomiting and reflux) |

Genitourinary2,8

Cryptorchidism Female fertility is normal Males can have fertility issues (e.g., defective spermatogenesis caused by cryptorchidism, gonadal dysfunction due to impaired Sertoli cell function) Malformations (renal pelvis dilation, solitary kidney, duplex collecting system) Puberty can be delayed in both sexes Growth2,4,8 Birth weight and length are normal Failure to thrive and short stature (50% to 70% of patients with Noonan syndrome) Mean final adult height is 63 to 66 inches (160 to 168 cm) in males and 59 to 61 inches (150 to 155 cm) in females Hematologic 1,3,4,10,11 Increased bleeding tendency (due to factor deficiency, quantitative or qualitative platelet defect) Leukemia Myeloproliferative disorder Lymphatic8 Lymphedema |

Neurologic1,8

Behavioral conditions (stubbornness, irritability, body image problems, poor self-esteem) Central nervous system malformation Early motor milestones delay (hypotonia and joint laxity) Learning difficulties Mild intellectual disability (33% of patients with Noonan syndrome) Most individuals have normal intelligence Speech disorders Skeletal2,4 Cubitus valgus Spinal abnormality (scoliosis, talipes equinovarus) Sternal deformities (pectus carinatum superiorly, pectus excavatum inferiorly) Skin conditions2,4 Dystrophic nails Extra prominence on pads of fingers and toes Follicular keratosis Hyperelastic skin Moles Multiple lentigines Nevi Thick curly hair or thin sparse hair |

Information from references 1 through 11.

Figure 1.

Newborn with Noonan syndrome.

Figure 4.

Adult with Noonan syndrome.

Nonspecific prenatal anomalies common among patients with Noonan syndrome include increased nuchal translucency, polyhydramnios, and abnormal maternal serum triple screen (α-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, and unconjugated estriol). The most common morphologic fetal anomaly is hydrothorax. Diagnosis of cardiac anomalies is rarely made prenatally. The diagnosis of Noonan syndrome should be considered in all fetuses with a normal karyotype and increased nuchal translucency, especially when cardiac anomaly, polyhydramnios, and/or multiple effusions are observed.12

Patients who have Noonan syndrome display clinical similarities to patients who have Turner syndrome (editor’s note: see http://www.aafp.org/afp/2007/0801/p405.html). However, patients can be easily differentiated because with Turner syndrome, only females are affected (because of the loss of the X chromosome), left-side heart defects are common, developmental delay occurs less often, renal anomalies are more common, and primary hypogonadism causes amenorrhea and sterility.8,13 A number of other partially overlapping syndromes, such as cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome, Watson syndrome, Costello syndrome, neurofibromatosis 1, and LEOPARD syndrome (lentigines, electrocardiogram conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormal genitalia, retardation of growth, and sensorineural deafness), also can be differentiated from Noonan syndrome based on clinical features.8,14

Diagnosis

Early, accurate diagnosis of Noonan syndrome is important because each patient requires an individual treatment regimen and has a different prognosis and recurrence risk. A scoring system has been devised to help diagnose patients with the condition (Table 215).

Table 2.

Diagnostic Criteria for Noonan Syndrome

| Feature | A = Major | B = Minor |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Facial | Typical facial dysmorphology (facial features vary with age and are described in Figures 1 through 4) |

Suggestive facial dysmorphology |

| 2. Cardiac | Pulmonary valve stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and/or electrocardiographic results typical of Noonan syndrome |

Other defect |

| 3. Height | < 3rd percentile | < 10th percentile |

| 4. Chest wall | Pectus carinatum/excavatum | Broad thorax |

| 5. Family history |

First-degree relative with definite Noonan syndrome |

First-degree relative with suggestive Noonan syndrome |

| 6. Other features |

All of the following: intellectual disability, cryptorchidism, and lymphatic vessel dysplasia |

One of the following: intellectual disability, cryptorchidism, or lymphatic vessel dysplasia |

note: Noonan syndrome is considered present if the patient has typical facial dysmorphology plus one feature from categories 2A through 6A or two categories from features 2B through 6B, or has suggestive facial dysmorphology plus two features from categories 2A through 6A or three features from categories 2B through 6B.

Adapted with permission from van der Burgt I, Berends E, Lommen E, van Beersum S, Hamel B, Mariman E. Clinical and molecular studies in a large Dutch family with Noonan syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1994;53(2):190.

Until recently, diagnosis was made solely on the basis of clinical features, but molecular genetic testing can provide confirmation in 70% of cases.8 Noonan syndrome is caused by mutations in the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which is essential for cell cycle differentiation, growth, and senescence.14 Approximately one-half of the known mutations are in the protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor, type 11 (PTPN 11) gene.8

Genetic Counseling

Most cases are sporadic. In familial cases, autosomal dominant inheritance is confirmed. The risk of Noonan syndrome developing in the sibling of an affected person is 50% if the parent is affected, but is less than 1% if the parent is unaffected. Risk of transmission to the offspring of an affected individual is 50%.8 Preimplantation genetic diagnosis can be offered in familial cases with known mutations.8

Management

Intellectual and physical abilities are normal in most adults with Noonan syndrome, but some may require multidisciplinary evaluation and regular follow-up care.16 Recently, management guidelines were developed by American and European consortia, and management is optimized by adherence to age-specific guidelines that emphasize screening and testing for common health issues.1,17 Referral to a clinical geneticist for assistance in the diagnosis and management of Noonan syndrome, including determining the appropriateness and sequence of genetic testing, may be helpful.1,8 Clinical growth charts are also available via a European network at http://www.dyscerne.org. Table 3 lists system-based management guidelines to assist physicians caring for patients with Noonan syndrome and their families.1,8,17 Table 4 describes when Noonan syndrome should be suspected.

Table 3.

Guidelines for Management of Noonan Syndrome

| System-based intervention |

Clinical issue | Timing of intervention | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auditory | Hearing loss | Hearing tests in infancy and/or at diagnosis |

— |

| Annual hearing test throughout childhood |

|||

| Cardiovascular | Congenital heart defects | At the time of diagnosis and regular follow-up with cardiologist |

Cardiac consultation, echocardiography, and electrocardiography |

| Children and adults without heart disease on initial evaluation should have cardiac reevaluation every five years |

|||

| Dental | Dental malocclusion | Oral examination by primary care physician at each visit |

— |

| Dental referral between one and two years of age, with annual dentist visits thereafter |

|||

| Dermatologic | See Table 1 for common skin findings |

Referral as indicated | — |

| Developmental | Behavioral disorders Developmental delay Learning difficulties Mild intellectual disability Speech disorders |

Development assessment annually (beginning in second half of first year of the patient′s life or at diagnosis) |

If screening results are abnormal, consider appropriate intervention |

| Baseline neuropsychologic assessment at primary school entry |

|||

| Endocrine | Delayed puberty Hypothyroidism Short stature |

Referral as indicated | Endocrine evaluation for growth hormone therapy to treat short stature and hormone therapy for delayed puberty |

| Thyroid function tests if patient shows signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism |

|||

| Gastroenterologic | Feeding difficulties | Referral as indicated | Appropriate therapeutic intervention as needed (e.g., swallowing study, speech therapy, reflux studies) |

| Genetic | To confirm diagnosis, genetic counseling and genotype– phenotype correlation |

Referral as indicated | — |

| Growth | Failure to thrive Short stature Slow growth |

At the time of diagnosis, three times a year for the first three years, then annually |

Monitor and plot growth on Noonan syndrome age-based growth charts |

| Hematologic | Increased bleeding tendencies (factor deficiency, quantitative or qualitative platelet defect) |

Baseline coagulation screen at diagnosis or after six to 12 months of age if screening was initially performed during infancy or whenever diagnosis is made |

If bleeding symptoms: First-tier: Baseline coagulation screen (complete blood count, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) |

| Second-tier (in consultation with hematologist): Specific factor assay and platelet function studies |

|||

| Lymphatic | Lymphatic vessel dysplasia, hypoplasia, or aplasia |

Referral as indicated | Refer patients with lymphedema to lymphedema clinic (contact National Lymphedema Network; www.lymphnet.org) |

| Metabolic | Failure to thrive Inadequate weight gain |

Referral as indicated | Dietary assessment and nutrition intervention |

| Neurologic | Arnold-Chiari malformation | Referral as indicated | Physician should have a low threshold for investigating neurologic symptoms (electroencephalography, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain) |

| Craniosynostosis | |||

| Headaches | |||

| Hydrocephalus | |||

| Seizures | |||

| Ocular | Dysmorphic findings Vision problems |

Detailed eye examination in infancy and/or at diagnosis |

— |

| Eye reevaluation as indicated if abnormal or every two years thereafter |

|||

| Pregnancy | Congenital heart defects | Per obstetrician′s recommendation |

Chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis for diagnosis if indicated |

| Effusion | |||

| Hydrops fetalis | Fetal ultrasonography and echocardiography | ||

| Increased nuchal translucency | |||

| Polyhydramnios | |||

| Renal anomalies | |||

| Renal | Renal anomalies (e.g., pyeloureteral stenosis, hydronephrosis) |

Renal ultrasonography at the time of diagnosis |

Increased risk of urinary tract infection if structural anomaly found, consider antibiotic prophylaxis and evaluation by nephrologist |

| Reproductive | Female fertility normal8 | Orchiopexy if testes undescended by one year of age |

Fertility clinic evaluation in males |

| Male fertility problems related to defective spermatogenesis caused by cryptorchidism or gonadal dysfunction due to impaired Sertoli cell function |

|||

| Skeletal | Pectus deformity of sternum Spinal abnormality |

Annual examination of chest and back |

If screening abnormal, consider radiography of the spine |

| Surgical and anesthesia risk |

Increased risk of complications due to a cardiac disorder, increased bleeding tendency, or craniofacial and/or vertebral anomalies |

Referral as indicated | See cardiovascular, hematology, and skeletal management recommendations |

Information from references 1, 8, and 17.

Table 4.

When to Suspect Noonan Syndrome

|

Noonan syndrome should be considered in anyone who presents with

two or more of the following: | |

| Characteristic facial features (Figures 1 through 4) Developmental delay and/or learning disability Heart defect Pubertal delay and/or infertility |

Short stature Typical chest deformity Undescended testes First-degree relative who has Noonan syndrome or any of the above features |

Resources

The following education, support, referral, and research websites are useful for physicians and for their patients who have Noonan syndrome:

GeneTests (www.genetests.org)

Genetics Home Reference (http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/noonan-syndrome)

Genomics Glossary.

Cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome: Characterized by cardiac abnormalities, distinctive craniofacial appearance, and cutaneous abnormalities.

Costello syndrome: Characterized by growth problems, developmental delay or intellectual disability, coarse facial features, curly or sparse fine hair, soft skin with deep palmar and plantar creases, papillomata of the face and perianal region, diffuse hypotonia, joint laxity, and cardiac disease.

LEOPARD syndrome: An acronym for the cardinal features of lentigines, electrocardiogram conduction abnormalities, ocular hypertelorism, pulmonary stenosis, abnormal genitalia, retardation of growth, and sensorineural deafness.

Neurofibromatosis 1: Characterized by multiple café au lait spots, axillary and inguinal freckling, neurofibromas, Lisch nodules, gliomas, and osseous lesions.

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis: A procedure used to decrease the chance of a particular genetic condition for which the fetus is specifically at risk by testing one cell removed from early embryos conceived by in vitro fertilization and transferring to the mother’s uterus only those embryos determined not to have inherited the mutation in question.

RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway: Essential in the regulation of the cell cycle, differentiation, growth, and cell senescence, all of which are critical to normal development. Mutations in the genes that encode for the pathway have profound effects on development.

Turner syndrome: A chromosomal abnormality in which one X chromosome is absent; 45,X karyotype.

Variable expressivity: The range of signs and symptoms that can occur in different persons with the same genetic condition.

Watson syndrome: An autosomal dominant disorder characterized by pulmonary stenosis, café au lait spots, decreased intellectual ability, and short stature. Most affected individuals have a large head, Lisch nodules, and neurofibromas.

This article is one in a series coordinated by the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. A glossry of genomics terms is available at http://www.aafp.org/afp/genglossary.

This clinical content conforms to AAFP criteria for continuing medical education (CME). See CME Quiz Questions on page 6.

Patient information: A handout on this topic, written by the authors of this article, is available at http://www.aafp.org/afp/2014/0101/p37-s1.html. Access to this handout is free and unrestricted.

Figure 2.

Infant with Noonan syndrome.

Figure 3.

Child/adolescent with Noonan syndrome.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Judith E. Allanson, MD, and Darryl Leja for their assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Romano AA, Allanson JE, Dahlgren J, et al. Noonan syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, and management guidelines. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):746–759. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendez HM, Opitz JM. Noonan syndrome: a review. Am J Med Genet. 1985;21(3):493–506. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320210312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw AC, Kalidas K, Crosby AH, Jeffery S, Patton MA. The natural history of Noonan syndrome: a long-term follow-up study. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(2):128–132. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.104547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharland M, Burch M, McKenna WM, Paton MA. A clinical study of Noonan syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1992;67(2):178–183. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raaijmakers R, Noordam C, Noonan JA, Croonen EA, van der Burgt CJ, Draaisma JM. Are ECG abnormalities in Noonan syndrome characteristic for the syndrome? Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167(12):1363–1367. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0670-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allanson JE, Hall JG, Hughes HE, Preus M, Witt RD. Noonan syndrome: the changing phenotype. Am J Med Genet. 1985;21(3):507–514. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320210313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allanson JE. Noonan syndrome. J Med Genet. 1987;24(1):9–13. doi: 10.1136/jmg.24.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allanson JE, Roberts AE. Noonan syndrome. Gene-Tests: Reviews. National Center for Biotechnology Information. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1124. Accessed May 23, 2013.

- 9.Lee NB, Kelly L, Sharland M. Ocular manifestations of Noonan syndrome. Eye (Lond) 1992;6:328–334. doi: 10.1038/eye.1992.66. pt 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kratz CP, Niemeyer CM, Castleberry RP, et al. The mutational spectrum of PTPN11 in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia and Noonan syndrome/myeloproliferative disease. Blood. 2005;106(6):2183–2185. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jongmans MC, van der Burgt I, Hoogerbrugge PM, et al. Cancer risk in patients with Noonan syndrome carrying a PTPN11 mutation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(8):870–874. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baldassarre G, Mussa A, Dotta A, et al. Prenatal features of Noonan syndrome: prevalence and prognostic value. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31(10):949–954. doi: 10.1002/pd.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan T. Turner syndrome: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(3):405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. The RASopathies: developmental syndromes of Ras/MAPK pathway dysregulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19(3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Burgt I, Berends E, Lommen E, van Beersum S, Hamel B, Mariman E. Clinical and molecular studies in a large Dutch family with Noonan syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1994;53(2):187–191. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320530213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Burgt I. Noonan syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2(4) doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noonan Syndrome Guideline Development Group Management of Noonan syndrome. A clinical guideline. http://www2.dyscerne.org. Accessed May 23, 2013.