SUMMARY

Malaria parasite transmission requires the successful development of Plasmodium gametocytes into flagellated microgametes upon mosquito blood ingestion, and the subsequent fertilization of microgametes and macrogametes for the development of motile zygotes, called ookinetes, which invade and transverse the Anopheles vector mosquito midgut at around 18-36 h after blood ingestion. Within the mosquito midgut, the malaria parasite has to withstand the mosquito's innate immune response and the detrimental effect of its commensal bacterial flora. We have assessed the midgut colonization capacity of 5 gut bacterial isolates from field-derived, and 2 from laboratory colony, mosquitoes and their effect on Plasmodium development in vivo and in vitro, along with their impact on mosquito survival. Some bacterial isolates activated the mosquito's immune system, affected the mosquito's life span, and were capable of blocking Plasmodium development. We have also shown that the ability of these bacteria to inhibit the parasites is likely to involve different mechanisms and factors. A Serratia marcescens isolate was particularly efficient in colonizing the mosquitoes’ gut, compromising mosquito survival, and inhibiting both sexual- and asexual-stage Plasmodium through secreted factors, thereby rendering it a potential candidate for the development of a malaria transmission intervention strategy.

INTRODUCTION

Because of the lack of an effective vaccine and the increasing resistance of mosquitoes to insecticides and Plasmodium parasites to drugs, malaria continues to be extensively distributed worldwide, causing nearly one million deaths per year (WHO, 2012). For successful malaria transmission, the parasite has to complete a complex life cycle within the vector that comprises several developmental transitions. A major bottleneck in malaria parasite development within the vector mosquito is the insect's midgut, where the majority of ingested parasites are killed (Sinden, 1999; Ghosh et al., 2000; Pradel, 2007). Within the midgut, Plasmodium gametocytes develop into the motile ookinete stage during the first 18 h after blood ingestion. During this period, the Plasmodium parasite interacts with human blood factors (such as nutrients, growth factors and immune factors), the mosquito peritrophic matrix and immune effectors, and the natural midgut microbial flora (Cirimotich et al., 2011a).

Several studies have shown that the mosquito microbiota can influence (mainly negatively) the parasite's development, and hence the efficacy of infection and transmission (Pumpuni et al., 1993; Pumpuni et al., 1996; Gonzalez-Ceron et al., 2003; Dong et al., 2009; Moreira et al., 2009; Cirimotich et al., 2011c). Boissiere et al. (2012) found using a metagenomic approach a median of 120 operational taxonomic units in the mosquito A. gambiae midgut, and Wang et al. (2011) showed that the microbiota composition and load fluctuates during the mosquito's life span. Removal of a large proportion of the microbial flora through treatment with antibiotics enhances the success of parasites in infecting the midgut epithelium, while enrichment of the microbiota through provision of bacteria via the blood meal has the opposite effect (Dong et al., 2009). A recent study with field mosquitoes showed a correlation between the presence of certain bacteria in the mosquito gut and infection status, suggesting that the composition of the midgut microbial flora plays an important role in determining vector competence and malaria transmission in the field (Boissiere et al., 2012). Another study by Bando et al. (2013) has also shown that Serratia marcescens from field caught Anopheles mosquitoes inhibit rodent Plasmodium ookinete infection of the midgut epithelium. Rani et al. (2009) showed that S. marcescens was a dominant isolate in field-caught female and larvae of A. stephensi mosquitoes in India, and that both S. marcescens and Elizabethkingia meningoseptica were dominant species in lab-reared mosquitoes. A recent study from Ngwa et al. (2013) also showed that E. meningoseptica was the dominant species in the midgut of lab-reared male and female mosquitoes and that it possessed anti-Plasmodium activity. An Elizabethkingia anopheles isolate from midguts of field-caught A. gambiae mosquitoes has shown 98.6% identity to E. meningoseptica (Kampfer et al., 2011). Others and we have shown that the mosquito's innate immune system is not only activated upon infection with the parasite but also as a result of exposure to the midgut microbiota (Dong et al., 2009; Meister et al., 2009, Kumar et al., 2010, Cirimotich et al., 2011a, Blumberg et al., 2013). The bacteria-induced basal immunity also results in the production of anti-Plasmodium effectors that limit infection.

An overlap between the mosquito's antibacterial and anti-Plasmodium defense activities exists; most anti-Plasmodium immune effectors have also been linked with antibacterial effects, while some antibacterial effectors have no impact on Plasmodium development (Dong et al., 2006; Garver et al., 2009; Blumberg et al., 2013; Cirimotich et al., 2010). While basal immune activation by the mosquito midgut microbiota provides a certain degree of protection against parasite infection, bacterial isolates that exert direct anti-Plasmodium activity, independently of the mosquito, have also been identified and studied (Dong et al., 2009; Meister et al., 2009). One of the best characterized natural anti-Plasmodium microbes is an Enterobacter isolate, Esp_Z, isolated from the midgut of wild field-caught mosquitoes in southern Zambia. Esp_Z inhibits Plasmodium development from gametocyte to ookinete through the production of reactive oxygen species both in vivo and in vitro (Cirimotich et al., 2011c). The ability of some bacterial isolates to block Plasmodium development and in some cases also shorten the mosquito lifespan renders them potential candidates for the development of new ways to control malaria, since they could be developed and deployed as a low-cost and logistically simple malaria control strategy based on exposure to mosquitoes through artificial nectar feeding (Cirimotich et al., 2011b).

Here we present a survey of selected likely natural mosquito microbiota isolates, specific bacterial isolates derived from field-caught and laboratory colony Anopheles mosquito midguts, and assess their midgut colonization capacity, in vivo (mosquito infection) and in vitro (parasite culture) anti-Plasmodium activity, and possible mechanism of action through the activation of mosquito immunity or secretion of anti-parasitic factors. We have also studied the impact of these bacteria on mosquito mortality as a result of systemic infection and midgut colonization. The specific bacterial isolates were selected based on their higher prevalence in field-caught and laboratory-reared mosquitoes (Dong et al., 2009; Cirimotich et al., 2011c). In vitro and in vivo experiments showed that Pseudomonas putida (P.pu), Pantoea sp (P.sp) and S. marcescens (S.ma) bacterial isolates were able to block Plasmodium development in vivo when the bacteria were introduced via a sugar meal, while Comamonas sp. (C.sp), Acinetobacter sp. (A.sp), P.pu, P.sp, P. rhodesiae (P.rh), S.ma, and Elizabethkindgia anophelis (E.an) also showed in vitro Plasmodium blocking activity. S.ma isolates influenced mosquito fitness when introduced into the midgut. The parasite blocking mechanism did not appear to be the same for all the tested isolates and was attributed to either direct interaction with the parasite, the production of anti-parasitic secondary metabolites, and/or an activation of the mosquito's immune system.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Colonization and persistence of bacterial isolates in the A. gambiae midgut

A major aim of our study was to assess the possibility that bacterial isolates from field-caught and laboratory colony mosquitoes (Table 1) could interfere with the preinvasive- and pre-oocyst-stage sporogonic development of Plasmodium in vivo and to probe the possible parasite-blocking mechanisms involved. The inhibition of parasite development in the mosquito midgut by a bacterium could potentially be mediated by a bacterium-produced inhibitory metabolite, a direct interaction between the bacterium and the parasite, or the induction of anti-Plasmodium immune responses. Regardless of the mechanism, a Plasmodium-inhibitory activity would depend on the bacterium's ability to colonize the midgut of a large proportion of the mosquito cohort and persist over time (Cirimotich et al., 2011b). To assess these parameters, we introduced single bacterial isolates via the sugar meal for 2 days into mosquitoes after effectively removal of microbial flora as a result of antibiotic treatment prior to exposure to the experimental isolates (Dong et al., 2009; Blumberg et al., 2013).

Table 1.

Bacterial isolates, their origin, growth medium, previous publication and genbank ID.

| Bacterial Species | Acronym | Source of Isolation | Tissue of Isolation | Gram Staining | Original Medium Selection | GenBank accession # | Previous report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comamonas sp. | C.sp | Wild-caught A. arabiensis from Macha, Zambia | Midgut | - | LB Agar | JF690938 | Cirimotich et al., 2011c |

| Acinetobacter sp. | A.sp | Wild-caught A. arabiensis from Macha, Zambia | Midgut | - | LB Agar | JF690925 | Cirimotich et al., 2011c |

| P. putida | P.pu | Wild-caught A. arabiensis from Macha, Zambia | Midgut | - | LB Agar | JF690929 | Cirimotich et al., 2011c |

| Pantoea sp. | P.sp | Wild-caught A. arabiensis from Macha, Zambia | Midgut | - | LB Agar | JF690934 | Cirimotich et al., 2011c |

| Pseudomonas rhodesiae | P.rh | Wild-caught A. arabiensis from Macha, Zambia | Midgut | - | LB Agar | JF690935 | Cirimotich et al., 2011c |

| Serratia marcescens | S.ma | A. gambiae from insectary colony* | Midgut | - | LB Agar | KF591600 | Dong et al., 2009 |

| Elizabethkindgia anophelis | E.an | A. gambiae from insectary colony* | Midgut | - | LB Agar | KF591599 | Dong et al., 2009 |

Insectary of Johns Hopkins School of Public Health

We then assayed the colonization of the midgut by these bacteria at 3, 6, and 9 days after introduction, while the mosquitoes were reared on a sterile sucrose solution. In nature, the mosquitoes would not have been sterile, and the tested bacteria would also have to compete with other species of the microbiota that could influence these parameters. However, we used antibiotic treated aseptic mosquitoes for these assays to avoid interference from the natural microbiota, which can vary in terms of load and species composition between individual mosquitoes from the same generation and cage and would therefore complicate the interpretation of our data (Dong et al., 2009). It would also be difficult to discriminate between the colonies of the various bacterial species through visual inspection of bacterial colony morphology and color. The assayed colonization parameters differed among the tested bacterial isolates and showed dynamic fluctuations over the 9-day period (Fig. 1). S.ma showed the greatest prevalence in the mosquito cohort throughout the 9-day (three time-points: 3-, 6-, 9-day) period, starting at 85% on day 3 and reaching 100% on days 6 and 9. S.ma proliferated to approximately 2x105 bacteria per midgut on days 6 and 9. A.sp and P.pu showed relatively low prevalence, remaining at under 20% throughout the assayed time period, but they fluctuated dynamically in terms of numbers of bacteria per midgut, reaching high numbers only on days 3 and 9. C.sp and P.sp also showed a low prevalence throughout the 9-day period, only reaching high numbers in individual midguts on days 3 and 9 and diminishing by day 9. P.rh and E.an showed low-to-average prevalence, with E.an reaching approximately 45% on day 9. Both bacteria displayed low or undetectable numbers in individual midguts on day 3 but proliferated to approximately 2x105 – 1.5×106 on days 6 and 9. Overall, the recolonization of the tested bacteria was low, except S.ma that showed the highest colonization capacity. The observed fluctuations in prevalence and colonization intensity are likely to reflect a bacterium's ability to colonize and persist in a mosquito midgut devoid of other bacteria and are likely to depend on multiple factors, such as the ability to utilize available nutrients, resist mosquito immune responses and digestive enzymes, and survive in the biochemical environment of the gut, which is likely to change over the lifetime of the mosquito. Ingestion of a blood meal is also likely to change the bacterial colonization dynamics of the midgut, with a profound increase in bacteria being present in the blood bolus, likely as the result of an abundance of nutrients and a decrease in reactive oxygen species (Kumar et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2011). While the presence of other bacterial isolates would probably dramatically change the colonization capacity of our tested bacteria, these assays provide baseline information on the adaptation of these bacteria to the mosquito midgut environment.

Figure 1. Colonization and persistence of bacteria in mosquito midguts.

Midgut bacterial prevalence (A, C, E) in the mosquito cohort and bacterial load (B, D, F) in individual mosquitoes at 3 (A, B), 6 (C, D), and 9 (E, F) days post-microbiota acquisition via a sugar meal containing 1×105 bacteria/μL. This experiment was performed three times and the microbiota of five to six mosquitoes were evaluated in each time point. The breaks in the Fig. 1D were made in order to show the bacterial load in all groups of mosquitoes challenged with the different midgut bacterial isolates. C.sp, Comamonas sp.; A.sp, Acinetobacter sp; P.pu, P. putida; P.sp, Pantoea sp.; P.rh, P. rhodesiae; S.ma, S. marcescens; and E.an, E. anophelis. Bars indicate the standard deviation.

In vivo inhibition of sporogonic-stage P. falciparum by bacterial isolates

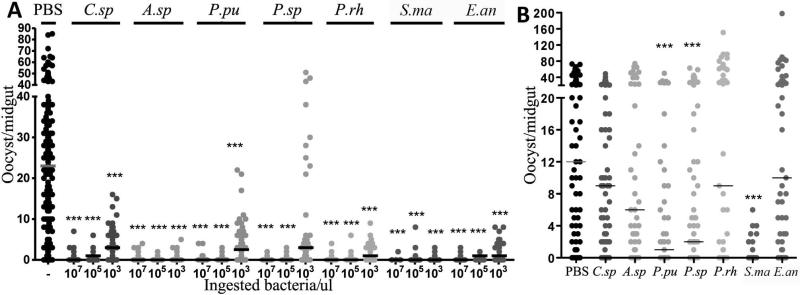

Once the colonization capacity had been determined, we performed experiments to investigate whether the bacterial isolates could inhibit the sporogonic development of Plasmodium in vivo prior to the oocyst stage. We co-introduced different concentrations of bacteria into the mosquitoes with the Plasmodium gametocytes through the blood meal and then quantified parasite infections, as a measure of oocyst development, at 7 days after feeding. Co-introduction of bacteria with the parasite would ensure an equal number of each tested isolate and a 100% prevalence of each isolate during the early developmental stages of Plasmodium in the midgut lumen. All the bacterial isolates tested had a prominent effect on parasite development when introduced at approximately 105 or 107 bacteria per midgut, reducing the median oocyst load to approximately zero at the higher exposure concentration (Fig. 2A, Table S1). All the bacterial isolates except of P.sp also interfered with infection at a dose of 103 bacteria per midgut, but the C.sp., P.pu, and P.sp. isolates did not exert a complete blocking, suggesting that the mechanism of Plasmodium inhibition could be different and/or require a larger number of introduced bacteria for these isolates.

Figure 2. In vivo Plasmodium inhibition by bacterial isolates.

(A) P. falciparum oocyst infection intensity 7 days after feeding on blood containing the parasite and 107, 105 or 103 bacteria/μL. (B) P. falciparum oocyst infection intensity 7 days after feeding on a parasite gametocyte culture. Mosquitoes had been exposed to a sugar solution (1.5% sugar) containing 105 bacteria/μL prior to Plasmodium infection. Dots represent the number of oocysts from each individual mosquito, and horizontal lines indicate the median number of oocysts. C.sp, Comamonas sp.; A.sp, Acinetobacter sp.; P.pu, P. putida; P.sp, Pantoea sp.; P.rh, P. rhodesiae; S.ma, S. marcescens; and E.an, E. anophelis. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks above each column. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons were used to analyze the data where PBS treated groups served as controls; * p<0.05, ** 0.03>p>0.01, *** p<0.01. Detailed statistical analyses are presented in Tables S1 (for Fig. 2A) and S2 (for Fig. 2B).

Since a natural route of bacterial introduction would most likely occur through nectar feeding rather than the host blood, we also tested the parasite-blocking effect of our bacterial isolates after colonization of the mosquito midgut through introduction by sugar feeding. In these experiments, we exposed aseptic antibiotic-treated mosquitoes to sucrose solutions supplemented with 105 bacteria/μL for 2 days prior to feeding on a P. falciparum gametocyte culture. Sugar feeding–mediated introduction of P.pu, P.sp, and S.ma into the mosquito midgut resulted in a significant inhibition of P. falciparum infection (p<0.01), with S.ma and P.pu exerting the strongest parasite-blocking activity (Fig. 2B, Table S2). Bacteria introduced with the blood meal rapidly proliferate to high numbers during the time-period when parasite inhibition occurs (Fig. S1). The generally lesser parasite-inhibitory effect of sugar meal-introduced bacteria was most likely due to the greater exposure of the Plasmodium to bacteria that had been introduced through blood feeding, while the parasite's exposure to bacteria introduced through sugar feeding depend on the bacteria's ability to colonize the gut (with only sugar feeding) and then proliferate after ingestion of Plasmodium infected blood.

In vitro inhibition of sporogonic-stage Plasmodium by bacterial isolates and culture supernatants

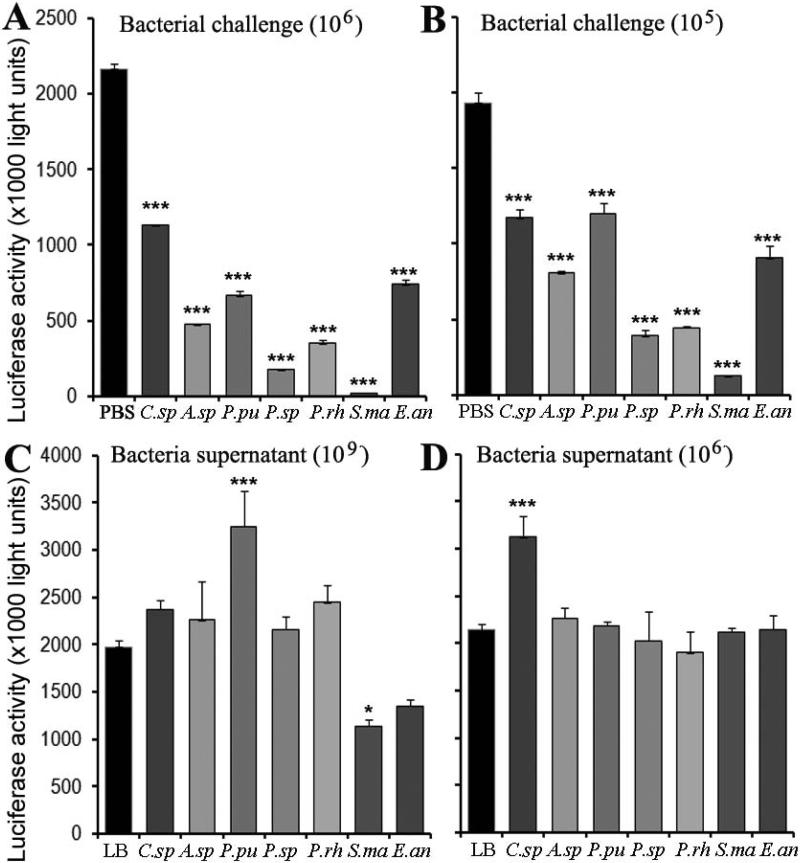

We next proceeded with experiments to obtain a more detailed understanding of the specific Plasmodium developmental stage that is inhibited by these bacterial isolates, and to assess whether the inhibition involves a mosquito-mediated process, or a direct inhibitory action by the bacteria. We performed in vitro exposure experiments using a the more robust rodent parasite ookinete culture with a transgenic P. berghei strain that expresses an ookinete stage–specific luciferase gene (Cirimotich et al., 2011c; G. Mlambo and G. Dimopoulos, unpublished). In these assays, we exposed a P. berghei ookinete culture to 106 or 105 bacteria per well (of 24-well plate) and then assayed the number of developed ookinetes 24 h later, based on their luciferase activity. These experiments were performed in an ookinete culture medium with blood. The results indicated that all the bacterial isolates could affect the development of ookinetes at both bacterial loads tested here (106 and 105 CFU per well). The bacterial isolates P.sp, P.rh, and S.ma exerted the strongest parasite-inhibitory activity in a dosage-dependent manner at the tested concentrations, while C.sp and P.pu showed the weakest parasite-inhibitory activity (Fig. 3A, B). These results of our in vitro inhibition assays suggested that several bacterial isolates can inhibit parasite development, either through a direct interaction with the parasites or through the production of inhibitory factors, as we have previously demonstrated for an Enterobacter isolate, Esp_Z. We can however not exclude the possibility that some bacteria isolates differ in their ability to inhibit either P. berghei or P. falciparum in vitro cultures (Cirimotich et al., 2011c).

Figure 3. In vitro sexual-stage Plasmodium inhibition by bacterial isolates and bacterial culture supernatants.

(A, B) In vitro inhibition of ookinete development as a measure of P. berghei luciferase activity after incubation of an ookinete culture with 106 (A) or 105/mL (B) bacterial isolates, or PBS as control, for 24 h. (C, D) In vitro inhibition of ookinete development as a measure of P. berghei luciferase activity after a 24 h incubation of an ookinete culture with supernatants from a 109 (bacteria/mL (C) or 106 bacteria/mL (D). C.sp, Comamonas sp.; A.sp, Acinetobacter sp.; P.pu, P. putida; P.sp, Pantoea sp.; P.rh, P. rhodesiae; S.ma, S. marcescens; and E.an, E. anophelis. Bars indicate the standard deviation. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks above each column by using PBS (A,B) or LB (C,D) as control. Unpaired t-test; * p<0.05, ** 0.03>p>0.01, *** p<0.01.

To assess whether the in vitro Plasmodium inhibitory effects of the bacterial isolates are mediated by bacteria-produced secreted factors or require a direct interaction with the bacteria, we tested the influence of fresh bacteria-free culture supernatants on the in vitro P. berghei development up to the ookinete stage. Exposure of P. berghei to 109 or 106 CFU-equivalent LB culture supernatants for 24 h showed that only S.ma culture supernatant had inhibitory effect on ookinete development, while P.pu and C.sp culture supernatants enhanced ookinete development (Fig. 3C, D). These results suggest that anti-parasitic action of S.ma is mediated by a secreted soluble factor that interferes with Plasmodium development prior to the ookinete stages, while P.pu and C.sp produce factors that facilitate ookinete development. Other studies have shown that S. marcescens can mediate inhibition of parasites such as Leishmania and Trypanosoma (Castro et al., 2007; Moraes et al., 2008). The inhibition of in vitro parasite development by direct exposure to all the bacterial isolates, including P.pu and C.sp bacteria, suggests that this inhibitory mechanism may involve interaction of ookinetes with the peritrophic matrix or midgut epithelium by the bacteria or cell wall components. Alternatively, inhibition of the parasite when co-cultured with the bacteria may be a result of resource competition (reviewed in (Cirimotich et al., 2011a)).

Bacterial isolates elicit mosquito immune responses that contribute towards the anti-Plasmodium activity

We and others have shown that the mosquito midgut microbiota stimulates the mosquito's innate immune system, which, in turn, acts against the malaria parasite. In particular, the mosquito IMD immune signaling pathway that controls the Rel2 NFkB transcription factor has been implicated in this process and represents the major anti-P. falciparum defense system in Anopheles mosquitoes (Frolet et al., 2006; Dong et al., 2009; Mitri et al., 2009; Dong et al., 2011). Previous studies have shown that mosquito defense mechanisms against Plasmodium and bacteria overlap significantly, and the majority of the anti-P. falciparum genes also influence the mosquito's resistance to bacterial infection (Meister et al., 2005; Dong et al., 2006, 2009; Garver et al., 2009; Ramirez et al., 2012).

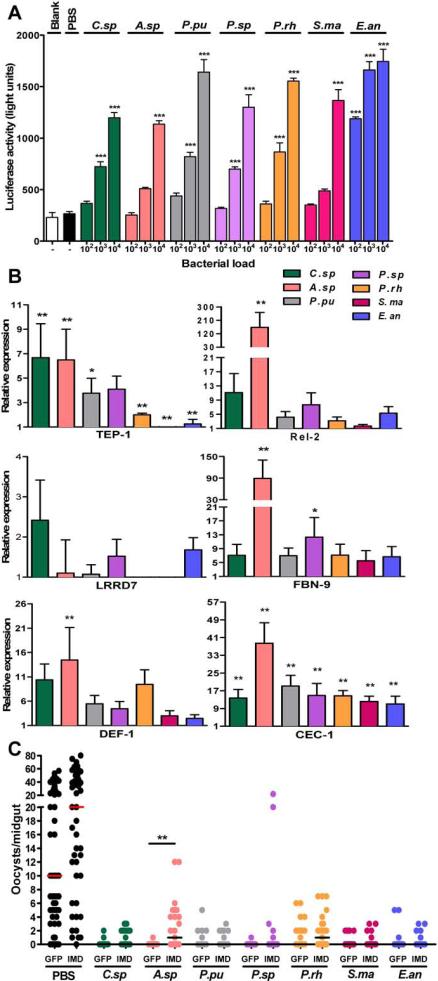

We performed a series of experiments to investigate whether our bacterial isolates were able to stimulate the activation of the immune system in an immune-competent cell line and mosquito midgut, and whether the activation of the IMD pathway was contributing to their parasite-inhibitory activity in the midgut tissue. We first performed in vitro assays to test whether a 16-h exposure of the cell line Sua5b to our bacterial isolates would activate a cecropin 1 promoter that drives a luciferase marker gene (Meister et al., 2005; Luna et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2012). All the bacterial isolates activated the cecropin 1 promoter in a dosage-dependent manner, with E.an being the most potent immune elicitor (Fig. 4A). Then we assessed the transcript abundance of six different IMD pathway-regulated or -related immune genes (TEP1, REL2, LRRD7, FBN9, defensin 1, and cecropin 1) in the mosquito's midgut at 8 h after the introduction of 105 bacteria via a non-parasite infected blood meal (Levashina et al., 2001; Meister et al., 2005; Dong et al., 2006; Dong and Dimopoulos, 2009; Garver et al., 2009, 2012). This time-point was selected since it likely overlaps with the time when parasite development is inhibited by some bacteria. TEP1, LRRD7, and FBN9 are potent anti-P. falciparum factors that are regulated by the IMD pathway transcription factor Rel2. Defensin 1 and cecropin 1 have not been associated with inhibition activity against this parasite species but are also regulated by the IMD pathway-controlled Rel2 transcription factor. The results showed that transcripts of all the assayed immune genes were enriched to different degrees in midgut epithelium after exposure to at least one of the tested bacteria (Fig. 4B). Independent exposure to all seven bacteria increased the mRNA abundance of at least three of the analyzed genes (cecropin 1, defensin 1, and FBN9) (Fig. 4B). The unresponsiveness of some of the immune genes after exposure to some of the bacteria isolates could reflect a different time-kinetic of transcriptional infection response, since we only assayed one time point after exposure. Almost all the immune genes responded with increased transcript abundance after exposure to C.sp, A.sp, and P.rh (Fig. 4B). These results suggested that the modulation of the immune system caused by the introduction of our bacterial isolates could be at least partly responsible for the inhibition of Plasmodium development in vivo.

Figure 4. Immune-eliciting capacity of bacterial isolates and involvement of a bacteria-induced Imd pathway-mediated immune response in anti-P. falciparum activity.

(A) Activation of cecropin 1 (cec-1) promoter-driven luciferase upon bacterial challenge of the Sua5B cell line with 102, 103, or 104 bacteria/well for 16 h, as compared to PBS-treated control cells. (B) Fold change in transcript levels of the immune marker genes thioester-containing protein 1 (TEP1), Rel2, leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 7 (LRRD7), fibrinogen immunolectin 9 (FBN9), defensin 1 (DEF-1) and cecropin 1 (CEC-1) in A. gambiae midguts 8 h after ingestion of blood containing 105 bacteria/μL, compared to mosquitoes fed on sterile blood. Quantifications were normalized based upon the expression levels of the S7 housekeeping gene. Each column and error bar represents the -fold change in mRNA abundance, and standard deviations are indicated. (C) The impact of bacteria-elicited IMD pathway activation on in vivo parasite infection. P. falciparum oocyst numbers in mosquitoes that had been treated with either the control GFP dsRNA or Imd dsRNA gene prior to feeding on a blood-meal containing P. falciparum and 105 bacteria/μL or PBS as a control. C.sp, Comamonas sp.; A.sp, Acinetobacter sp.; P.pu, P. putida; P.sp, Pantoea sp.; P.rh, P. rhodesiae; S.ma, S. marcescens; and E.an, E. anophelis. Statistical significance is represented by asterisks. p<0.05; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-test for (A), Mann-Whitney test or oneway ANOVA with Dunnett's post-test for (B); Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons for (C) where GFP dsRNA injected control mosquitoes served as control; * p<0.05, ** 0.01<p<0.03, *** p<0.01. Detailed statistical analyses of the Fig. 4C are presented in Table S3.

We finally tested whether the anti-P. falciparum IMD pathway was mediating the parasite-inhibitory activity of some of our studied bacterial isolates. We compared the permissiveness to parasite infection of cohorts of mosquitoes fed on a bacteria (105 CFU/μL)-supplemented P. falciparum gametocyte culture that had either been treated with a control GFP dsRNA or a dsRNA that targets the Imd receptor protein and thereby inactivates the pathway. Inhibition of the IMD pathway did result in an increased P. falciparum infection of mosquitoes exposed to A.sp. and P.rh, suggesting that these bacterial isolates, exert their in vivo anti-parasitic activity at least in part through the activation of the IMD immune signaling pathway (Fig. 4C, Table S3). Plasmodium-inhibitory bacterial isolates that blocked parasite development despite IMD pathway activation could still be stimulating other anti-Plasmodium mechanisms of the mosquito innate immune system.

The influence of systemic infection and midgut colonization by bacterial isolates on mosquito longevity

The implementation of anti-Plasmodium-based malaria control approach could be based on the ability of selected bacteria to either block the parasite or significantly shorten the life span of the mosquito. To investigate this question with regard to our bacterial isolates, we assessed their influence on mosquito survival during a 7-day period after different routes and concentrations of exposure.

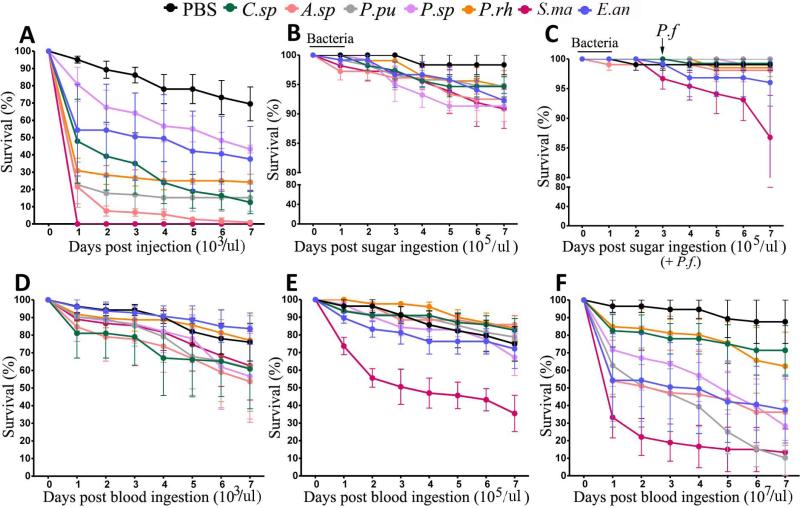

We first tested the effect of systemic bacterial infection on mosquito longevity. Direct injection of 103 bacteria into the mosquito hemolymph resulted in a moderate mortality ranging from 45% to 100% over the 7-day period for all the tested bacteria, with S.ma and A.sp causing the strongest mortality; infection with C.sp. and both Pseudomonas (P.pu and P.rh) isolates also caused moderate mortality (Figs. 5A and S2 and Table S4). Introduction of bacteria into the mosquito's midgut through the blood meal resulted in a greater rate of mortality when compared to the mortality produced when they were introduced through a sugar meal at same bacterial loads (105/μL). The survival rates ranged from 90-100% in the sugar-fed group, as compared to 30-90% in the blood-fed group at this level of bacterial exposure (Figs. 5B, E, and S2 and Table S4). The mosquito survival was influenced by the bacteria loads administered to the mosquitoes through a blood meal (Figs. 5D-F and S2 and Table S4). The greater mortality of the mosquitoes exposed to the highest bacterial load (107) through a blood meal is most likely a result of the overall larger number of bacteria introduced through the blood meal due to the proliferation of bacteria in the blood bolus. Interestingly, some bacteria caused a greater or more rapid mosquito mortality when introduced at the lowest 103/mosquito load, compared to 105/mosquito. This could possibly imply that some bacteria can more rapidly proliferate to higher numbers when introduced at a lower initial concentration through the blood meal. We also investigated the impact of P. falciparum infection on the mortality of mosquitoes that had been exposed to 105/μL bacteria through a sugar meal 3 days prior to feeding on a gametocyte culture. P. falciparum infection enhanced the mortality of the mosquitoes exposed to S.ma but resulted in a slightly lesser mortality of the mosquitoes exposed to the other bacterial isolates (Fig. 5B, C). This difference could be explained by a transient activation of the mosquito immune system in response to parasite infection. Overall, our bacterial challenge experiments using different bacterial exposure routes showed that S.ma caused the strongest mortality (Figs. 5A-F and S2 and Table S4).

Figure 5. Impact of bacterial challenge on mosquito mortality.

(A) Survival rates of A. gambiae mosquitoes over a 7-day period after injection of 103 bacteria into the hemolymph through the thorax. (B) Survival rates of mosquitoes over a 7-day period after feeding on a 1.5% sucrose solution containing 105 bacteria/μL. (C) Survival rates of mosquitoes over a 7-day period after feeding on a 1.5% sucrose solution containing 105 bacteria/μL, followed by feeding on a P. falciparum gametocyte culture for 3 days after bacteria acquisition. (D - F) Survival rates of mosquitoes over a 7-day period after feeding on a blood-meal containing P. falciparum gametocytes plus 103, 105, or 107 bacteria/μL, respectively. Curves represent the median of mosquito survival. At least 35 mosquitoes were used in each replicate, and three replicates were included with standard errors shown. C.sp, Comamonas sp.; A.sp, Acinetobacter sp.; P.pu, P. putida; P.sp, Pantoea sp.; P.rh, P. rhodesiae; S.ma, S. marcescens; and E.an, E. anophelis. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank test was used to determine the p-values. Detailed Kaplan-Meier survival curves of three biological replicates are presented in Fig. S2 and statistical analyses are presented in Table S4.

Bacterial isolates produce factors that inhibit the asexual P. falciparum stages

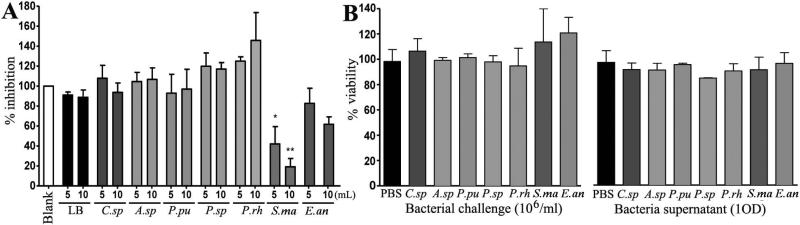

Since one of the bacterial isolates, S.ma, produced factors in the culture supernatant that directly inhibited P. berghei ookinete development in vitro and therefore may me relevant for potential drug lead compounds, we also tested the inhibitory activity of bacterial culture supernatants against the human asexual blood stage of P. falciparum. We exposed 100 μL (1% HCT and 1% parasitemia) of asexual P. falciparum cultures to 5 μL and 10 μL of a 105 bacteria/mL supernatant and assayed parasite viability according to standard methods (Smilkstein et al., 2004). The results showed that S.ma produced one or several factors that effectively inhibited this parasite stage by 20-40% (Fig. 6A). Since the S.ma culture supernatant also inhibited P. falciparum ookinete development, it is likely that the same putative anti-parasitic factor inhibits both the sexual and asexual parasite stages. We have shown that the culture supernatant of an Enterobacter species, Esp_Z, inhibit Plasmodium development though a mechanism that involves reactive oxygen species (Cirimotich et al., 2011c). To provide baseline information on whether the parasite inhibitory activity of the S.ma isolate was attributed to a similar mechanism we assayed H2O2 production by this bacterium. In contrast to Esp_Z, S.ma did not produce H2O2 suggesting that it likely inhibit Plasmodium through a different mechanism (see methods section for details). One important qualifier for a natural product to serve as a lead compound for transmission blocking of therapeutic drug development is a low (or no) toxicity to humans. To provide some preliminary indications concerning the potential toxicity of the bacteria-produced putative anti-parasitic factors, we looked at the toxicity of culture supernatants using an established hamster kidney (BHK) cell viability assay. Exposure of the cells to 10 μL of 106 or 109 bacteria/mL culture supernatants for 1 h did not affect their viability, suggesting a low toxicity for mammalian cells (Fig. 6B). However, more extensive studied are required to assess the safe use of natural bacterial isolates for field-based malaria control. For example, an E. anophelis strain has been shown to cause meningitis and some Serratia strains can also cause human infections (Frank et al., 2013; Martins et al., 2013).

Figure 6. Effect of bacterial culture supernatant on in vitro asexual-stage P. falciparum and cytotoxic effect of bacteria on mammalian cells.

(A) The viability of blood-stage P. falciparum in in vitro culture was assayed after a 24-h exposure to 5 or 10 μL of overnight bacteria-cultured supernatants or LB medium and compared to a parasite culture exposed to water. The bars represent the means and standard deviation of the percentage of trophozoite inhibition by the bacterial supernatant. (B) Baby hamster kidney (BHK) cell viability after treatment with 106 bacteria/well and filtered supernatant equivalent to 109 bacteria/well (1 OD660), or PBS as a control for 1 h. The bars represent the means and standard deviation of the BHK cell viability after challenge with bacteria. C.sp, Comamonas sp.; A.sp, Acinetobacter sp.; P.pu, P. putida; P.sp, Pantoea sp.; P.rh, P. rhodesiae; S.ma, S. marcescens; and E.an, E. anophelis. The statistical significance is represented by asterisks. Unpaired t-test; * p<0.05, ** 0.03>p>0.01, *** p<0.01.

CONCLUSIONS

Several studies, along with the present study, have shown a profound influence of the mosquito's midgut bacteria on attributes that influence vectorial capacity, such as susceptibility to human pathogens and mosquito longevity. It is therefore plausible to consider the application of natural bacteria of the mosquito microbiota as a means of preventing vector-borne diseases (Cirimotich et al., 2011b). Here we have characterized the properties of seven gram-negative bacteria isolates from field-caught and laboratory colony mosquitoes that are relevant for Anopheles vector competence: their capacity to colonize and persist in the midgut, their in vivo and in vitro anti-Plasmodium activities, and their impact on mosquito longevity. While several bacterial isolates only displayed a modest effect on parasite development with our laboratory infection system it is quite likely that this level of exposure could result in complete refractoriness in the field where infection intensities are much lower, rarely exceeding 2-3 oocysts per midgut (Sinden et al., 2004). Several studies have shown that the mosquito intestinal microbiota impair Plasmodium and dengue virus infection (Pumpuni et al., 1993; Pumpuni et al., 1996; Xi et al., 2008; Dong et al., 2009; Ramirez et al., 2012; Blumberg et al., 2013). Conversely, the observed low parasite infection levels in the field are likely to, at least partly, be a result of blocking by the mosquito midgut microbiota. While our experimental system involved co-infections of mosquitoes with the parasite and single bacterial isolates, to reduce the complexity of the system, in nature these bacteria co-exist with numerous other species and the effect on parasite development will depend on the synergistic action of the entire microbiota. A Serratia isolate S.ma displayed the strongest in vivo and in vitro anti-Plasmodium activity, along with a prominent entomopathogenic activity and the ability to colonize and persist in the mosquito midgut. These properties, together with the 100% prevalence of this bacterium in the exposed mosquito cage population, render it potentially interesting for further detailed characterization towards development of a malaria control strategy based on mosquito exposure to bacteria. The in vitro anti-Plasmodium activity of the S.ma culture supernatant suggests that it is likely mediated by a secreted soluble factor. A previous study has also shown that S. marcescens from field caught Anopheles mosquitoes inhibit rodent Plasmodium ookinete infection of the midgut epithelium, but did not test whether it produced secreted factors that factors could inhibit sexual and asexual parasite stages (Bando et al., 2013). While two of the tested bacterial isolates mediated in vivo anti-Plasmodium activity at least partly though the mosquito's anti-Plasmodium IMD immune signaling pathway, all the bacteria except for S.ma required direct interaction with the parasite for in vitro inhibition. The mechanism of inhibition is likely to differ for the tested isolates and depend on the interaction between the parasite and bacterial surface molecules. In summary, a large proportion of the mosquito midgut-associated bacteria have the ability to interfere with parasite infection and development in the mosquito, suggesting that they play an important role in modulating malaria transmission in the field.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Rearing A. gambiae mosquitoes

A. gambiae mosquitoes (Keele strain) were reared in the Insectary core facility of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. Mosquito cages were maintained in controlled chambers with 12-h light/dark cycles at 27°C and 70% humidity. Sugar solution (10%) was offered to the mosquitoes for normal feeding. When necessary, mosquitoes were placed in small sterile cups with sterile cotton, filter paper, and nets. Antibiotics in 10% sugar solution (10 μg/mL penicillin-streptomycin and 15 μg/mL gentamicin; Gaithersburg, MD, USA) (Dong et al., 2009) were given to mosquitoes in some experiments in order to reduce the native midgut bacteria. For each replica, six midguts of mosquitoes treated with antibiotics were dissected, homogenized, and plated (with serial dilution) on LB agar plates to confirm bacteria removal.

Bacterial isolates

The bacteria used in this study were isolated from: a) the midguts of wild-caught Anopheles arabiensis mosquitoes from Macha (Zambia), Comamonas sp. (C.sp), Acinetobacter sp. (A.sp), P. putida (P.pu), Pantoea sp. (P.sp), and P. rhodesiae (P.rh) (Cirimotich et al., 2011c) (Table 1); and b) laboratory-colonized A. gambiae mosquitoes from the insectary of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, S. marcescens (S.ma) and E. anophelis (E.an) (Dong et al., 2009) (Table 1). Re-sequencing of the full length 16s rRNA gene of a Serratia sp. and a Chryseobacterium sp., initially described in Dong et al. (2009), showed 99% identity to Serratia marcescens subsp and Elizabethkingia anophelis strain 5.20, therefore they were here renamed to S.ma and E.an respectively. And GenBank accession numbers for S.ma and E.an are KF591600 and KF591599, respectively (Table 1).

Infection of A. gambiae with midgut bacteria

One OD600 of bacterial culture growth overnight (approximately 109 bacteria/mL) was washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended to the final concentration used in the experiments. Different concentrations of bacteria (103 - 107 bacteria/μL) were introduced into the mosquitoes via blood meal, sugar meal, or thoracic injection. In some experiments, P. falciparum gametocyte culture was added to blood containing bacteria, which was given to the insects by artificial membrane feeder (Dong et al., 2006). Female mosquitoes were starved for at least 8 h prior to a blood meal to ensure engorgement. For the P. falciparum inhibition experiments, firstly 2-3 days after emergence the mosquitoes were maintained free of bacteria (aseptic) as a result of supplement of antibiotic in 10% sucrose. Secondly, regular sterile 10% sucrose solution was given to the mosquitoes for 1 day, and they were starved for 14 h before the introduction of the bacteria in the sugar meal. Finally, bacteria were introduced into the mosquitoes in a 1.5% sucrose solution for 1 day. The sucrose solution was provided in a manner allows mosquitoes to feed similarly to nectar feeding in nature (Muller et al., 2010). For the preparation of bacteria in sugar, one OD600 of bacteria (109 bacteria/mL) was washed with PBS and diluted into the 1.5% sugar solution to a final concentration of 105 bacteria/μL. At 3, 6, and 9 days after feeding with sugar containing isolated bacterium, A. gambiae midguts were dissected and plated on LB agar plates in serial dilutions. This experiment was performed three times and the microbiota of five to six mosquitoes were evaluated in each time point based on colony forming units (CFU).

Infection of A. gambiae with P. falciparum

A. gambiae mosquitoes, 3-4 days old, were fed on membrane feeders for 30 min with blood containing P. falciparum gametocytes (NF54). For some experiments, P. falciparum were added to blood containing the midgut microbiota at concentrations of 103, 105, or 107/μL. In addition, other experiments were performed with 105 bacteria/μL administered by sugar meal 3 to 4 days prior the mosquitoes were infected with P. falciparum by artificial feeding (Dong et al., 2006; Garver et al., 2009). The gametocytemia and exflagellation events were assessed after 18 days of P. falciparum culture. The gametocyte culture was centrifuged and diluted in a mixture of red blood cells supplemented with serum. On the same day, mosquitoes were sorted, and the unfed mosquitoes were removed. At 7 to 8 days after blood feeding, the fed mosquitoes were dissected, and their midguts were stained with 0.1% mercurochrome. The number of oocysts per midgut was determined with a light-contrast microscope, and the median for the control and each experimental condition was calculated. More than three independent replicates were used per group. Replicates were pooled and a Chi-square test was performed to determine the differences in the infection prevalence. To determine the significance of differences in oocyst intensity (p<0.05), the Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests with Dunn's multiple comparisons tests were used as described in previous studies (Lowenberger et al., 1999; Dong et al., 2009; Mitri et al., 2009; Povelones et al., 2009; Rodrigues et al., 2010; Dong et al., 2011). Dunn's test was performed by comparing the specified treatment group versus the PBS control group. The detailed information and statistical analyses are presented in Tables S1, S2, S3.

Double-strand RNA (dsRNA) synthesis, RNAi gene-silencing assays, and mosquito infection with P. falciparum

GFP and IMD dsRNA were amplified by PCR reaction at 94°C for 5 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 7 min. The primer sequences used are listed in Table S5. Amplicons were purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). PCR-purified products were used to synthesize specific dsRNAs using the HiScribe T7 In Vitro Transcription Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). For RNAi silencing experiments, at least 60 mosquitoes were each injected with 69 nL of 3 μg/μL GFP dsRNA (control) or IMD gene dsRNA (experimental) into their thoraxes using a nanojector (Drummond). Three independent experiments were performed. At 3 days after injection, mosquitoes were allowed to feed on blood containing P. falciparum and field-isolated bacteria (105/μL) or PBS (control). Three days after the mosquito injections, the efficiency of mosquito IMD silencing was calculated using quantitative PCR (qPCR, see below).

RNA extraction and qPCR

The RNA of A. gambiae submitted to different experimental conditions (fed on blood containing field-isolated bacteria, injected with dsRNA) was extracted using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). After extraction, the RNA was treated with Turbo DNase (Ambion Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) to remove any potential DNA contamination. cDNA was synthesized with the MMLV Reverse Transcriptase 1st-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Three biological replicates and two experimental replicates were used for qPCR, which was normalized with the constitutive S7 ribosomal protein gene. qPCR assays were performed using the Syber Green Master Mix Kit (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) in a 20 μL reaction volume. We used 40 reaction cycles of 95°C for 10 min, 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the relative expression in the samples as compared to the control. Primer sequences are listed in Table S5. Mann-Whitney U-tests and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-test were used when appropriate (p<0.05).

A. gambiae survival assays after bacterial challenge

For mortality assays, at least 35 3- 4days old A. gambiae females were kept in a wax-lined cardboard cup at 27° C with 70% humidity and maintained with a sterile 10% sucrose solution. Four different bacteria challenges were made prior to the survival assays: a) injection of bacteria into the female mosquito thorax; b) sugar feeding with sugar-containing bacteria; c) feeding with sugar-containing bacteria and then infection with P. falciparum; and d) feeding with blood containing both bacteria and P. falciparum. After each challenge, mosquitoes were daily monitored for survival. Three independent experiments were performed. Survival percentages represent the mean survival percentage for all three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with GraphPad Prism5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), and p-values were determined by the Wilcoxon test as described in (Corby-Harris et al., 2010; Dong et al., 2011).

Activity of luciferase in Sua-5b cells under the control of the cecropin1 promoter

Sua-5B cells containing the luciferase gene under the control of the A. gambiae cecropin1 gene (Cec1) promoter were used for this experiment. Cells transfections with Cec1 DNA constructs were performed as described in (Meister et al., 2005; Luna et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2012). Cells were maintained in Schneider's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. On the day before the challenge, cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104/well in 96-well plates. Isolated microbiota was then added to each well at a concentration of 102, 103 and 104/well and co-incubated for a period of 16 h at room temperature. The cells were then harvested and subjected to the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Relative light units per sec were measured in a Tecan Safire2™ plate reader (530 nm excitation; 590 nm emission). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-test with a confidence value of p<0.05.

Detection of microbiota-produced hydrogen peroxide

The supernatant of bacteria overnight cultures were collected and the hydrogen peroxide of the samples were measured using the Amplex® Red hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay kit (Invitrogen, Inc.) according the manufacturer's recommended protocols. Following a 30 minutes incubation of supernatant with the assay reagents, fluorescence units were determined using a Tecan Safire2™ plate reader (530 nm excitation; 590 nm emission). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test with confidence value of p<0.05.

In vitro luciferase–based P. berghei ookinete inhibition assays

Female Swiss Webster mice (6-8 weeks old) were infected with a transgenic P. berghei strain (PbwRL) that expresses the Renilla luciferase gene under the ookinete-specific WARP gene promoter. Ookinete cultures using PbwRL were set up as described above. To assay the ookinete-inhibitory effect of the bacteria and their culture supernatants, 10-fold serial dilutions (104-108 CFU/mL) were added to each well in triplicate, with PBS used as a control. To control for background expression of Renilla luciferase, cultures were maintained in ookinete medium adjusted to pH 7.0 (ookinete development requires a pH of 8.3). Ookinete cultures were incubated at 19°C for 26-28 h with 105 or 106 bacteria, or supernatant from 109 or 105 bacteria/mL, and the culture material in each well was transferred to a 1.5 mLEppendorf tube. The culture material was centrifuged at 1,800 rpm for 4 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The luciferase assay was performed using the Renilla luciferase assay system (E2810, Promega USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions (G. Mlambo and G. Dimopoulos, unpublished). In brief, 100 μl of 1X lysis buffer was added to the pellet and gently vortexed, then incubated at RT for 15 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 2 min, and the supernatant was transferred to a clean 1.5 mL Epperndorf tube and placed on ice. Supernatant (20 μl) was added to 100 μl of luciferase assay buffer, mixed by pipetting, and the sample read immediately on a 20/20n Luminometer (Turner Biosystems, USA) over a 10-sec integration period. The percentage inhibition of ookinete development was calculated by subtracting the blank and expressing the luciferase units as a percentage of the control value (no bacteria). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test, with a confidence value of p<0.05.

Anti-P. falciparum assays with asexual stages

The activity of the bacterial culture supernatants against P. falciparum asexual blood stages was tested using a standard SYBR green I-based fluorescence assay that measures parasite DNA (Smilkstein et al., 2004). The parasites were synchronized using 5% sorbitol (Lambros and Vanderberg, 1979) and added to 96-well plates at 1% hematocrit and 1% ring-stage parasitemia after addition of various concentrations of filtered bacterial culture supernatants. Three experimental replicates were performed, and 250nM chloroquine was used as a positive control and 0.5% DMSO and/or 5% LB medium as negative controls. Plasmodium parasites and bacterial supernatants were incubated in a candle jar at 37°C for 72 h. Equal volumes of a SYBR green I solution in lysis buffer (Tris [20 mM; pH 7.5], EDTA [5 mM], saponin [0.008%; w/v] and Triton X-100 [0.08%; v/v]) was then added to each well and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1 to 2 h. Plates were read on a HTS 7000 fluorescence plate reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at 485 nm for excitation and 535 nm for emission. The percentage of inhibition was calculated relative to the negative (100% inhibition) and positive control (0% inhibition) values. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test, with a confidence value of p<0.05.

Mammalian cell viability assays

One hundred microliters of 1×105 baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells in DMEM medium were split into 96-well plates. For this assay, isolated bacteria were added to cells at a concentration of 105 and 106/well or to PBS (control) and incubated for 1 h; 10 μl of the overnight growth-isolated bacterial supernatant or LB medium (control) was added to the cells and incubated for 4 h. The viability of the cells was measured with the CellTiter-Fluor™ Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to manufacturer's protocol. After a 30 min incubation, fluorescence units were determined using a Tecan Safire2™ plate reader (380 nm excitation; 505 nm emission; Tecan, Durham, NC, USA). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test, with a confidence value of p<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Temporal bacterial growth dynamics in mosquito midguts after introduction through blood meal feeding at approximately 105 bacteria per mosquito. C.sp, Comamonas sp.; A.sp, Acinetobacter sp.; P.pu, P. putida; P.sp, Pantoea sp.; P.rh, P. rhodesiae; S.ma, S. marcescens; and E.an, E. anophelis. Bars represent the mean +/− the standard error. 6 mosquitoes were included in each assayed point of 3 biological replicates.

Figure S2. Kaplan-Meier survivorship curve comparing insects infected with bacteria by thorax injection (A), sugar feeding (B), sugar feeding plus P. falciparum infection (C), and co-infection with 103 (D), 105 (E), or 107 (F) bacteria and P. falciparum. Mosquitoes were raised under similar conditions after bacterial challenge. Three biological replicates were done and are shown here. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used together with the log-rank test to determine the p-values, and p<0.05 indicates significance (Table S4).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the members of the Dimopoulos lab; the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute Insectary and Parasitology core facilities; and the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health Genomic Analysis and Sequencing core facility. We would also like to thank Dr. Deborah McClellan for editorial assistance. This work has been supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease grant R01AI061576 and the Bloomberg Family Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- Bando H, Okado K, Guelbeogo WM, Badolo A, Aonuma H, Nelson B, et al. Intra-specific diversity of Serratia marcescens in Anopheles mosquito midgut defines Plasmodium transmission capacity. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1641. doi: 10.1038/srep01641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg BJ, Trop S, Das S, Dimopoulos G. Bacteria- and IMD pathway-independent immune defenses against Plasmodium falciparum in Anopheles gambiae. PloS One. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072130. 10.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissiere A, Tchioffo MT, Bachar D, Abate L, Marie A, Nsango SE, et al. Midgut microbiota of the malaria mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae and interactions with Plasmodium falciparum infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002742. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro DP, Seabra SH, Garcia ES, de Souza W, Azambuja P. Trypanosoma cruzi: ultrastructural studies of adhesion, lysis and biofilm formation by Serratia marcescens. Exp Parasitol. 2007;117:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirimotich CM, Dong Y, Garver LS, Sim S, Dimopoulos G. Mosquito immune defenses against Plasmodium infection. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirimotich CM, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. Native microbiota shape insect vector competence for human pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2011a;10:307–310. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirimotich CM, Clayton AM, Dimopoulos G. Low- and high-tech approaches to control Plasmodium parasite transmission by anopheles mosquitoes. J Trop Med. 2011b;2011:891342. doi: 10.1155/2011/891342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirimotich CM, Dong Y, Clayton AM, Sandiford SL, Souza-Neto JA, Mulenga M, Dimopoulos G. Natural microbe-mediated refractoriness to Plasmodium infection in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2011c;332:855–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1201618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corby-Harris V, Drexler A, Watkins de Jong L, Antonova Y, Pakpour N, Ziegler R, et al. Activation of Akt signaling reduces the prevalence and intensity of malaria parasite infection and lifespan in Anopheles stephensi mosquitoes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001003. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Dimopoulos G. Anopheles fibrinogen-related proteins provide expanded pattern recognition capacity against bacteria and malaria parasites. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9835–9844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807084200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Manfredini F, Dimopoulos G. Implication of the mosquito midgut microbiota in the defense against malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000423. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Aguilar R, Xi Z, Warr E, Mongin E, Dimopoulos G. Anopheles gambiae immune responses to human and rodent Plasmodium parasite species. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e52. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Das S, Cirimotich C, Souza-Neto JA, McLean KJ, Dimopoulos G. Engineered anopheles immunity to Plasmodium infection. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002458. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank T, Gody JC, Nguyen LB, Berthet N, Le Fleche-Mateos A, Bata P, et al. First case of Elizabethkingia anophelis meningitis in the Central African Republic. Lancet. 2013;381:1876. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frolet C, Thoma M, Blandin S, Hoffmann JA, Levashina EA. Boosting NF-kappaB-dependent basal immunity of Anopheles gambiae aborts development of Plasmodium berghei. Immunity. 2006;25:677–685. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garver LS, Dong Y, Dimopoulos G. Caspar controls resistance to Plasmodium falciparum in diverse anopheline species. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000335. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garver LS, Bahia AC, Das S, Souza-Neto JA, Shiao J, Dong Y, Dimopoulos G. Anopheles imd pathway factors and effectors in infection intensity-dependent anti-Plasmodium action. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002737. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Edwards MJ, Jacobs-Lorena M. The journey of the malaria parasite in the mosquito: hopes for the new century. Parasitol Today. 2000;16:196–201. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01626-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Ceron L, Santillan F, Rodriguez MH, Mendez D, Hernandez-Avila JE. Bacteria in midguts of field-collected Anopheles albimanus block Plasmodium vivax sporogonic development. J Med Entomol. 2003;40:371–374. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-40.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampfer P, Matthews H, Glaeser SP, Martin K, Lodders N, Faye I. Elizabethkingia anophelis sp. nov., isolated from the midgut of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;61:2670–2675. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.026393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Molina-Cruz A, Gupta L, Rodrigues J, Barillas-Mury C. A peroxidase/dual oxidase system modulates midgut epithelial immunity in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2010;327:1644–1648. doi: 10.1126/science.1184008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levashina EA, Moita LF, Blandin S, Vriend G, Lagueux M, Kafatos FC. Conserved role of a complement-like protein in phagocytosis revealed by dsRNA knockout in cultured cells of the mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Cell. 2001;104:709–718. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00267-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenberger CA, Kamal S, Chiles J, Paskewitz S, Bulet P, Hoffmann JA, Christensen BM. Mosquito-Plasmodium interactions in response to immune activation of the vector. Exp Parasitol. 1999;91:59–69. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna C, Hoa NT, Lin H, Zhang L, Nguyen HL, Kanzok SM, Zheng L. Expression of immune responsive genes in cell lines from two different Anopheline species. Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15:721–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins P, Cleary DF, Pires AC, Rodrigues AM, Quintino V, Calado R, Gomes NC. Molecular analysis of bacterial communities and detection of potential pathogens in a recirculating aquaculture system for scophthalmus maximus and solea senegalensis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister S, Agianian B, Turlure F, Relogio A, Morlais I, Kafatos FC, Christophides GK. Anopheles gambiae PGRPLC-mediated defense against bacteria modulates infections with malaria parasites. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000542. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister S, Kanzok SM, Zheng XL, Luna C, Li TR, Hoa NT, et al. Immune signaling pathways regulating bacterial and malaria parasite infection of the mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:11420–11425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitri C, Jacques JC, Thiery I, Riehle MM, Xu J, Bischoff E, et al. Fine pathogen discrimination within the APL1 gene family protects Anopheles gambiae against human and rodent malaria species. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000576. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes CS, Seabra SH, Castro DP, Brazil RP, de Souza W, Garcia ES, Azambuja P. Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi interactions with Serratia marcescens: ultrastructural studies, lysis and carbohydrate effects. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118:561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009;139:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller GC, Beier JC, Traore SF, Toure MB, Traore MM, Bah S, et al. Field experiments of Anopheles gambiae attraction to local fruits/seedpods and flowering plants in Mali to optimize strategies for malaria vector control in Africa using attractive toxic sugar bait methods. Malar J. 2010;9:262. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwa CJ, Glockner V, Abdelmohsen UR, Scheuermayer M, Fischer R, Hentschel U, Pradel G. 16S rRNA gene-based identification of Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (Flavobacteriales: Flavobacteriaceae) as a dominant midgut bacterium of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi (Dipteria: Culicidae) with antimicrobial activities. J Med Entomol. 2013;50:404–414. doi: 10.1603/me12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira JH, Goncalves RL, Lara FA, Dias FA, Gandara AC, Menna-Barreto RF, et al. Blood meal-derived heme decreases ROS levels in the midgut of Aedes aegypti and allows proliferation of intestinal microbiota. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001320. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povelones M, Waterhouse RM, Kafatos FC, Christophides GK. Leucine-rich repeat protein complex activates mosquito complement in defense against Plasmodium parasites. Science. 2009;324:258–261. doi: 10.1126/science.1171400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradel G. Proteins of the malaria parasite sexual stages: expression, function and potential for transmission blocking strategies. Parasitology. 2007;134:1911–1929. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007003381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumpuni CB, Beier MS, Nataro JP, Guers LD, Davis JR. Plasmodium falciparum: inhibition of sporogonic development in Anopheles stephensi by gram-negative bacteria. Exp Parasitol. 1993;77:195–199. doi: 10.1006/expr.1993.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumpuni CB, Demaio J, Kent M, Davis JR, Beier JC. Bacterial population dynamics in three anopheline species: the impact on Plasmodium sporogonic development. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:214–218. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JL, Souza-Neto J, Torres Cosme R, Rovira J, Ortiz A, Pascale JM, Dimopoulos G. Reciprocal tripartite interactions between the Aedes aegypti midgut microbiota, innate immune system and dengue virus influences vector competence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani A, Sharma A, Rajagopal R, Adak T, Bhatnagar RK. Bacterial diversity analysis of larvae and adult midgut microflora using culture-dependent and culture-independent methods in lab-reared and field-collected Anopheles stephensian Asian malarial vector. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues J, Brayner FA, Alves LC, Dixit R, Barillas-Mury C. Hemocyte differentiation mediates innate immune memory in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Science. 2010;329:1353–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1190689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinden RE. Plasmodium differentiation in the mosquito. Parassitologia. 1999;41:139–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinden RE, Alavi Y, Raine JD. Mosquito-malaria interactions: a reappraisal of the concepts of susceptibility and refractoriness. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;34:625–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilkstein M, Sriwilaijaroen N, Kelly JX, Wilairat P, Riscoe M. Simple and inexpensive fluorescence-based technique for high-throughput antimalarial drug screening. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1803–1806. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1803-1806.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Gilbreath TM, 3rd, Kukutla P, Yan G, Xu J. Dynamic gut microbiome across life history of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae in Kenya. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Aedes aegypti toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000098. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Temporal bacterial growth dynamics in mosquito midguts after introduction through blood meal feeding at approximately 105 bacteria per mosquito. C.sp, Comamonas sp.; A.sp, Acinetobacter sp.; P.pu, P. putida; P.sp, Pantoea sp.; P.rh, P. rhodesiae; S.ma, S. marcescens; and E.an, E. anophelis. Bars represent the mean +/− the standard error. 6 mosquitoes were included in each assayed point of 3 biological replicates.

Figure S2. Kaplan-Meier survivorship curve comparing insects infected with bacteria by thorax injection (A), sugar feeding (B), sugar feeding plus P. falciparum infection (C), and co-infection with 103 (D), 105 (E), or 107 (F) bacteria and P. falciparum. Mosquitoes were raised under similar conditions after bacterial challenge. Three biological replicates were done and are shown here. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was used together with the log-rank test to determine the p-values, and p<0.05 indicates significance (Table S4).