Abstract

Purpose

To demonstrate feasibility of exploiting the spatial distribution of off-resonance surrounding metallic implants for accelerating multispectral imaging techniques.

Theory

Multispectral imaging (MSI) techniques perform time-consuming independent 3D acquisitions with varying RF frequency offsets to address the extreme off-resonance from metallic implants. Each off-resonance bin provides a unique spatial sensitivity that is analogous to the sensitivity of a receiver coil, and therefore provides a unique opportunity for acceleration.

Methods

Fully sampled MSI was performed to demonstrate retrospective acceleration. A uniform sampling pattern across off-resonance bins was compared to several adaptive sampling strategies using a total hip replacement phantom. Monte Carlo simulations were performed to compare noise propagation of two of these strategies. With a total knee replacement phantom, positive and negative off-resonance bins were strategically sampled with respect to the B0 field to minimize aliasing. Reconstructions were performed with a parallel imaging framework to demonstrate retrospective acceleration.

Results

An adaptive sampling scheme dramatically improved reconstruction quality, which was supported by the noise propagation analysis. Independent acceleration of negative and positive off-resonance bins demonstrated reduced overlapping of aliased signal to improve the reconstruction.

Conclusion

This work presents the feasibility of acceleration in the presence of metal by exploiting the spatial sensitivities of off-resonance bins.

Keywords: multispectral imaging, imaging near metal, acceleration, off-resonance

Introduction

Joint replacement (arthroplasty) has been established as a safe and effective procedure to alleviate chronic joint pain and to improve the functional status of patients. The prevalence of arthroplasty procedures has dramatically increased over the past decade due to the aging of the population, improvements in surgical techniques, and advances in joint implant design (1-3). Further, the demographic of joint replacement recipients has become younger, contributing to the increasing incidence of arthroplasty procedures (2).

Radiological imaging of metallic implants is necessary for clinical evaluation. Complications associated with metallic implants include infection, fractures around the implant, adverse reactions to metal debris, and necrotic caseous material (3-5). In the cases requiring surgical revision, imaging can also provide anatomical mapping of the metallic implant and evaluation of the surrounding tissue.

MRI has shown clinical value in diagnosing musculoskeletal complications in the context of arthroplasty procedures (6-8). The extreme off-resonance around metallic implants prevents complete excitation with conventional RF pulses. This occurs because modern MRI scanners cannot generate sufficiently narrow RF pulses, with sufficient B1 amplitudes, to excite such wide bandwidths. In addition, the severe off-resonance produces large image distortions with imaging sequences that use frequency encoding even with an extremely high readout bandwidth. Several multispectral imaging (MSI) techniques have improved the performance of MRI in the presence of metallic implants by combining independent 3D acquisitions of varying RF frequency offsets in order to reconstruct the signal around metallic implants. In particular, slice-encoding for metal artifact correction (SEMAC) (9), multiacquisition variable-resonance image combination (MAVRIC) (10), and hybrid approaches (MAVRIC-SL) (11) have all greatly reduced image distortions surrounding metallic implants and were described in detail in a recent review (12).

To address artifacts near metal due to frequency encoding, which occur even in MAVRIC/SEMAC methods (13), fully phase-encoded techniques (FPE) have been developed (14-17). These methods perform phase-encoding in all three spatial dimensions to completely avoid frequency encoding artifacts near metal. However, long scan times have prohibited clinical adoption. A spectrally-resolved fully phase-encoded (SR-FPE) 3D fast spin-echo (FSE) implementation was recently developed that utilized 3D Cartesian parallel imaging (PI) to demonstrate the potential for large reductions in scan time (17). While FPE techniques appear promising, they are also subject to the RF bandwidth limitation previously described. Therefore multiple FPE acquisitions at varying radiofrequency offsets are necessary to visualize distortion-free signal around metallic implants.

Whether using MAVRIC/SEMAC or FPE methods, acquiring multiple independent acquisitions, or off-resonance bins, is necessary to provide adequate excitation. This results in substantial increases in scan times that require significant acceleration for clinical use. Fortunately, a unique opportunity for acceleration exists when multiple off-resonance bins are acquired in the presence of metal. Each off-resonance bin contains spatially unique signal. These unique spatial sensitivities are analogous to the spatial sensitivities of multi-channel receiver coils and provide some redundancy to conventional spatial encoding mechanisms. The purpose of this work is to demonstrate the feasibility of this novel approach to reduce scan time for imaging methods in the presence of metal by exploiting the spatial distribution of off-resonance surrounding metallic implants.

Theory

Multispectral Imaging (MSI) of Off-Resonance

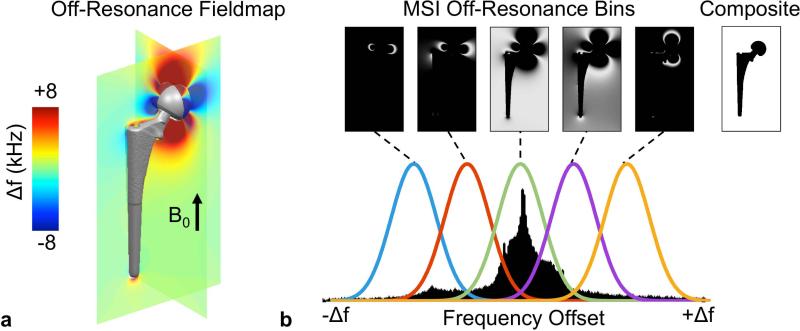

The large implant-induced B0 field perturbations depend on the position, size, shape, orientation, and susceptibility of the metallic implant (18). Figure 1a displays a 3D digital model of a total hip replacement prosthesis (titanium stem, cobalt-chromium-molybdenum ball) obtained with optical laser scanning. The off-resonance fieldmap was calculated with a Fourier based k-space filtering (19) and demonstrates the characteristic dipole pattern and extreme magnitude of off-resonance. Although the colormap was chosen to visualize the dipole effect, spins near the implant precess at frequency offsets > 15 kHz.

Figure 1.

The large susceptibility difference of metal induces spatially dependent off-resonance in adjacent tissue. (a) A digital model was generated with a 3D laser scanner of a hip implant (CoCr/Mo head, Ti femoral stem). The off-resonance fieldmap is calculated with a Fourier based k-space filtering (19) and demonstrates the characteristic dipole pattern and extreme off-resonance. Frequency offsets adjacent to the implant exceed 20 kHz, although the colormap was chosen to visualize the dipole effect. (b) Multispectral imaging (MSI) techniques acquire multiple 3D acquisitions of varying frequency offsets. These off-resonance bins represent spatially unique portions of the composite image.

As previously described, MSI techniques perform multiple independent 3D acquisitions with varying RF frequency offsets (9,10). Each of the independent acquisitions, or off-resonance bins, represents signal from a specific frequency range, as shown in Figure 1b. The off-resonance bins are reconstructed individually and then combined to form a composite image that includes signal from all bins.

Although this approach improves the ability to reconstruct signal near metallic implants, it results in substantial increases in scan time. Despite considerable acceleration factors from techniques like parallel imaging, compressed sensing, and data subsampling (20-24), additional scan time reductions would improve scan performance and clinical implementation through improved spatial resolution, increased volumetric coverage, reduced scan time, or combinations of the above.

Spatial Distribution of Off-Resonance Bins

The spatial distribution of off-resonance highlighted in Figure 1 illustrates that unique frequency bins will contain spatially unique signal. The exact spatial pattern and extent of off-resonance is dependent on the implant material, geometry, and its orientation with respect to the B0 field (18). However, in the absence of an applied magnetic field gradient and neglecting background B0 field inhomogeneities unrelated to the presence of metal, the following properties apply to all implant-induced perturbations. First, the central off-resonance bin (on-resonance) contains spins least affected by the B0 field perturbation caused by the metallic implant and subsequently contains the most signal assuming the field-of-view (FOV) is large relative to the implant. Second, with increasing frequency offset, the off-resonance bins contain signal with increasing proximity to the metal. Images from the most extreme off-resonance bins show sparse signal directly adjacent to the implant. Finally, the general directionality of the off-resonance distribution with respect to the B0 field is well understood: positive frequency offsets appear in the directions perpendicular to B0 while negative frequency offsets appear in the direction parallel to B0. This spatial separation of the positive and negative off-resonance components in relation to the B0 field is well seen in Figure 1.

Acceleration Using Spatial Sensitivities

Conventional parallel imaging (PI) techniques exploit the spatial sensitivities of multiple independent receiver coils to accelerate acquisitions (25-27). The signal from each coil represents a unique spatial subset of the full FOV image. The spatial sensitivities complement conventional spatial encoding and allow a reduced number of phase-encoding steps during acquisition, thereby accelerating the experiment.

In this work, we recognize that each off-resonance bin provides a unique spatial sensitivity. This spatial sensitivity is analogous to the sensitivity of a receiver coil, and a unique spatial subset of a full FOV image (Figure 1b). Effectively, a metallic implant creates a non-linear and multidimensional frequency encoding of the surrounding spins because of its inherent susceptibility. Although this encoding concept is a novel concept in metal imaging, non-metal work has shown that non-linear and multi-dimensional gradient fields can be used for spatial encoding (28-31). In this work, we propose to exploit these spatial sensitivities using an “off-resonance encoding” (ORE) strategy to accelerate acquisitions in the presence of metal.

Sampling Flexibility

Conventional PI techniques use multiple independent receiver coils to image subsets of the volume. Although they each have unique spatial sensitivities, the receiver coils inherently have identical sampling patterns and acceleration. This sampling constraint will be referred to as ‘uniform’ in this work. A uniform sampling of off-resonance bins implies identical sampling patterns across the bins.

Importantly, MSI techniques are not subject to the same sampling constraints as PI, which use multiple independent acquisitions to image subsets of the off-resonance. The sampling independence across off-resonance bins offers a unique k-space sampling opportunity, permitting different sampling schemes and difference reduction factors for different off-resonance bins.

Before describing the opportunities offered by this flexibility, clarification of terminology used to describe undersampling with this presented method is necessary. Each off-resonance bin can have an independent reduction factor, denoted R, which is the factor by which the data sampling is reduced. The undersampling can be characterized in a direction parallel to ( R∥ ) and perpendicular to ( R⊥ ) the B0 field. In addition, undersampling is independent for negative ( R-) and positive ( R+) off-resonance bins. For example, accelerating the negative off-resonance bins by a factor 3 parallel to B0 and the positive off-resonance bins by a factor of 2 perpendicular to B0 would be denoted R-∥ = 3 and R+⊥ = 2 respectively.

This sampling flexibility is a distinct and unique advantage of ORE. Acceleration can be optimized based on characteristic properties of off-resonance. The far off-resonance bins are inherently sparse, enabling higher reduction factors without aliasing.

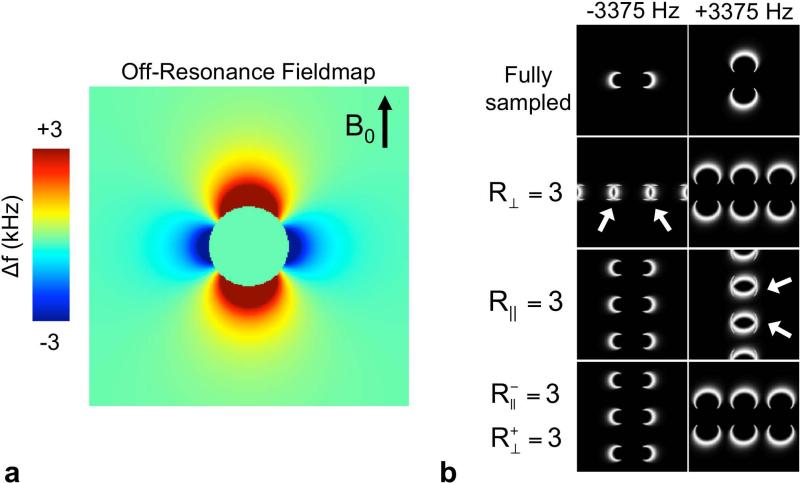

As previously described, the spatial constraints of the signed components of the off-resonance signal can be exploited as illustrated by Figure 2. Figure 2a illustrates the calculated off-resonance from a titanium sphere with a characteristic dipole pattern. Figure 2b shows simulated signal from off-resonance bins centered at -3375 Hz and +3375 Hz with a full-width at half max of 1125 Hz. Undersampling with a reduction factor of 3 in a dimension perpendicular to B0 ( R⊥ = 3) causes expected aliasing. Overlap of aliased signal only appears in the negative off-resonance bin (arrows Figure 2b). If the undersampling is instead applied to a phase-encoded dimension parallel to B0 ( R∥ = 3), overlap of the aliased signal only appears in the positive off-resonance bin. Finally, overlap of the aliased signal is avoided if undersampling is performed in directions parallel to ( R-∥ = 3) and perpendicular to ( R+⊥ = 2) B0 for negative and positive off-resonance bins respectively. This simplified example demonstrates the sampling flexibility of ORE to enable independent acceleration of the negative ( R-) and positive ( R+) off-resonance components of the signal in order to minimize signal aliasing for optimization in reconstruction.

Figure 2.

A metallic object provides unique opportunities for acceleration of MR imaging. (a) The calculated fieldmap from a titanium sphere illustrates the dipole effect and spatial constraints of the positive and negative components of off-resonance. These signed components are dependent on the geometry of the object in relation to the direction of the B0 field. (b) Sampling strategies can exploit this knowledge to minimize overlapping aliased signal. Simulated signal from off-resonance bins centered at -3375 Hz and +3375 Hz and a full-width at half max of 1125 Hz are shown with several undersampling strategies. Undersampling with a reduction factor of 3 in a direction perpendicular to B0 ( R⊥ = 3) causes overlap of aliased signal only in the negative off-resonance bin (white arrows). If the undersampling is instead applied in a direction parallel to B0 ( R∥ = 3), overlap of the aliased signal only appears in the positive off-resonance bin. The sampling flexibility of ORE enables independent acceleration of the negative ( R-) and positive ( R+) off-resonance components of the signal in order to minimize signal aliasing.

Note that for a given off-resonance bin, undersampling in multiple directions can be combined to increase acceleration. In this study, only a single direction for each bin was chosen for acceleration to demonstrate both the advantage of the sampling flexibility as well as the ability to exploit the known directional behavior of off-resonance.

Reconstruction Framework

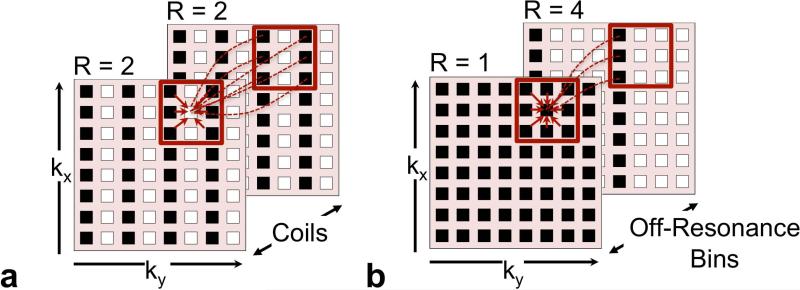

Parallel imaging (PI) reconstruction algorithms have been developed to use the spatial sensitivity patterns of receiver coils to reconstruct undersampled acquisitions. Figure 3a shows a k-space based (GRAPPA) PI implementation using multiple receiver coils (27). The ORE reconstruction of this study uses this exact framework, where the coil data is substituted with off-resonance bins. The ORE implementation consists of a k-space kernel-based approach to estimate the missing k-space points for each off-resonance bin (Figure 3b). The kernel weights determine the contribution of surrounding sampled points of each off-resonance bin to estimate each missing k-space point. This kernel is trained on fully sampled data at the center of k-space, known as the auto-calibration signal (ACS). One distinct feature of the ORE reconstruction is the opportunity for independent sampling patterns across off-resonance bins as described earlier. For optimal use of the available signal when reconstructing missing k-space points, a unique kernel is calibrated for each unique composite sampling pattern. Each off-resonance bin is reconstructed before performing a sum-of-squares combination.

Figure 3.

Optimal kernel calibration will account for unique sampling patterns in the off-resonance dimension. (a) Conventional k-space-based parallel imaging reconstruction algorithms optimize kernel calibration with each unique sampling pattern. (b) ORE reconstruction accounts for the independent sampling pattern of each off-resonance bin.

Methods

Image reconstruction was performed offline in MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) using the Parallel Computing Toolbox on a Mac workstation (2.5 GHz Intel Core i5, 8 GB RAM).

All stated reduction factors refer to the acceleration outside of the fully sampled ACS region except the overall effective reduction factor, Reff , which will be defined as the factor by which the total number of phase-encodes over all bins is reduced and will include acquisition of the ACS data. Use of the fully sampled ACS data for kernel calibration is reflected in the overall effective reduction factor, Reff . However, the ACS data was not included in the final reconstructed images to identify the effect of ORE reconstruction compared to a zero-filled reconstruction. All experiments used a 5 x 5 GRAPPA kernel.

Hip Prosthesis

A cobalt-chromium/titanium total hip replacement prosthesis was embedded in a cylindrical aqueous phantom (radius 9 cm, length 30 cm) and fitted with an acrylic grid (1 cm grid spacing) perpendicular to the cylinder's long axis. This phantom was placed parallel to the B0 field to simulate its typical anatomic orientation. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed at 1.5T (Optima MR450W, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) using a single channel transmit/receive quadrature head coil.

Due to the size of the hip phantom in the z dimension, a slab-select gradient was used to reduce the FOV in the z dimension a MAVRIC/SEMAC hybrid (11) (product name MAVRICSL) was used to reduce the FOV in the z dimension. A fully-sampled coronal dataset was acquired using the following imaging parameters: TE = 20 ms; TR = 1800 ms; matrix = 256 × 164; field of view (FOV) = 27 × 18.9 cm; slice thickness = 4 mm; slices = 30; echo train length = 16; RF bandwidth = 2.25 kHz; frequency bin separation = 1 kHz; frequency bins = 22; readout bandwidth = ±125 kHz; acquisition time 15 min 36 seconds. The goal of this study was to determine feasibility of ORE using off-resonance induced by the metal alone. For this reason, only the central slice was chosen for analysis, where off-resonance due to the slab-select gradient was negligible.

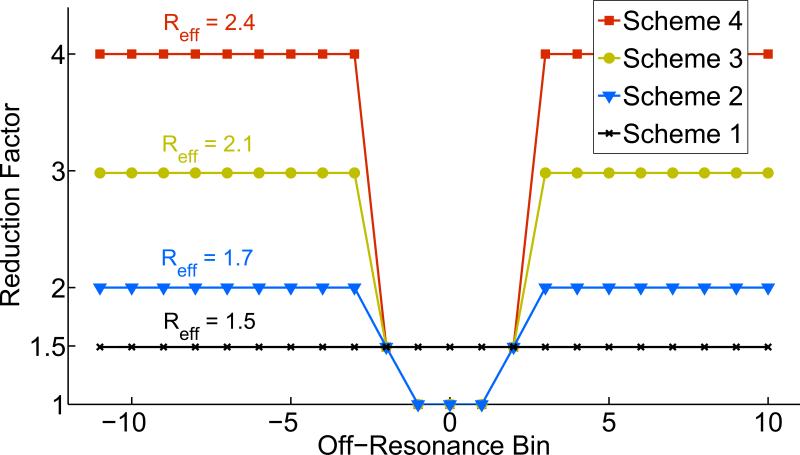

A bin-dependent undersampling scheme was designed according to the off-resonance histogram (Figure 1b). The reduction factor for each bin is adapted to reflect the amount of signal it contains. The majority of the spins within the FOV have relatively little frequency offset caused by the metal and are localized to the central bins. These central bins are subsequently fully sampled and contribute high SNR to the composite image. Conversely, the far-off-resonance bins contain sparse signal and are therefore undersampled. The transition bins between the sparse bins and the central bins are moderately undersampled.

Each bin of the central slice was retrospectively undersampled along the phase-encoding direction (ky) according to several acceleration schemes (Figure 4). Scheme 1 was a uniform sampling pattern where each off-resonance bin was sampled with the same pattern ( R = 1.5). Schemes 2-4 utilized an adaptive reduction factor according to the frequency distribution or off-resonance histogram for the central slice (Figure 1b). All sampling patterns in this retrospective study fully sampled ( R = 1) the three central off-resonance bins (-1, 0, +1) that contained the majority of the signal and moderately accelerated ( R = 1.5) the next two off-resonance bins (-2, +2). The remaining far-off-resonance frequency bins were more aggressively accelerated with increasing reduction factors ( R = 2, R = 3, R = 4) that correspond to schemes 2-4. The ACS region included 40 ky lines of each off-resonance bin for kernel calibration.

Figure 4.

The independent acquisitions of MSI methods enable an adaptive off-resonance reduction factor that can be exploited to preserve SNR, exploit the sparsity of the far-off-resonance bins, and optimize reconstruction accuracy. Scheme 1 uses a uniform undersampling pattern ( R = 1.5) across all off-resonance bins. Adaptive schemes 2-4 fully sample the three central bins and have increasing accelerations for far off-resonance bins. The y-axis corresponds to the outer k-space acceleration. The effective reduction factor, Reff , includes acquisition of the ACS region (40 kx lines).

A Monte Carlo simulation was performed to investigate the noise propagation throughout the reconstruction process for two sampling patterns, analogous to the noise map calculations used in conventional parallel imaging (26,32). To estimate the noise propagation, Gaussian noise was added in 500 independent noise realizations to both the fully sampled k-space and the undersampled data. The noise was estimated by measuring the standard deviation along the 500 noise realizations pixel-by-pixel and was normalized by the noise estimation of the fully sampled reconstruction. The final pixel-by-pixel map was a measure of the noise resulting from the sampling patterns and reconstruction. A noise map was created for sampling scheme 1 and 2 (Figure 4) using the coronal hip dataset to compare differences between a uniform and an adaptive undersampling pattern.

Knee Prosthesis

A custom-made model of the postoperative knee was placed in a cylinder (diameter 12 cm, length 15 cm) and filled with water doped with copper sulfate to simulate tissue adjacent to the knee as described by Chen et al. (33). The model consisted of plastic femoral and tibial bones (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) filled with oil to simulate subchondral fat and fitted to standard TKR components (Zimmer NexGen LPS-Flex cobalt-chrome femoral component, polyethylene spacer, and Zimmer NexGen MIS Mini-Keel titanium tibial component). This phantom was placed in the B0 field to simulate its typical orientation when implanted in a patient. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed at 1.5T (HDxt, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). A single channel transmit/receive head coil was used to avoid effects from multi-channel receiver coil sensitivities.

A fully sampled, MSI acquisition of the implant was then performed without slab-selection. This acquisition scheme is known as the original MAVRIC technique, as presented in reference (10). An axial dataset was acquired with the following imaging parameters: TE = 35 ms; TR = 1617 ms; matrix = 192 × 192; field of view (FOV) = 21 × 21 cm; slice thickness = 1.1 mm; slices = 152; echo train length = 16; RF bandwidth = 2.25 kHz; frequency bin separation = 1 kHz; frequency bins = 22; readout bandwidth = 1300 Hz/pixel; acquisition time 54 min 2 seconds.

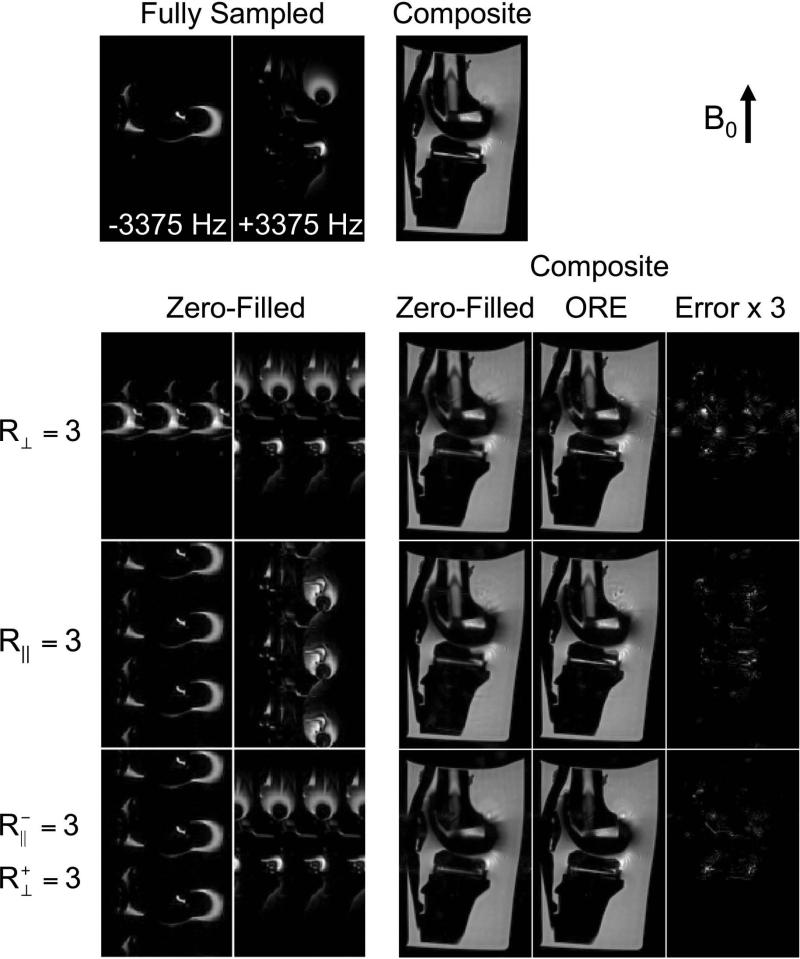

Three retrospective sampling schemes were used to demonstrate how the sampling flexibility of MSI can be exploited to optimize ORE reconstruction. The fully sampled axial data was Fourier-transformed along the frequency-encoding direction (kx) to demonstrate 2D acceleration using ORE along two phase-encoding dimensions (ky and kz). First, all off-resonance bins were undersampled in the phase-encoded dimension perpendicular to B0 with far-off-resonance acceleration of R⊥ = 3 (Figure 4, scheme 3). Second, this pattern was applied to the phase-encoded dimension parallel to B0 ( R∥ = 3). Third, the negative off-resonance bins were undersampled in the phase-encoded dimension parallel to B0 ( R-∥ = 3) and the positive off-resonance bins were undersampled in the phase-encoded dimension perpendicular to B0 ( R+⊥ = 3). The ACS region consisted of a region of size 40x40 for each off-resonance bin for kernel calibration.

Results

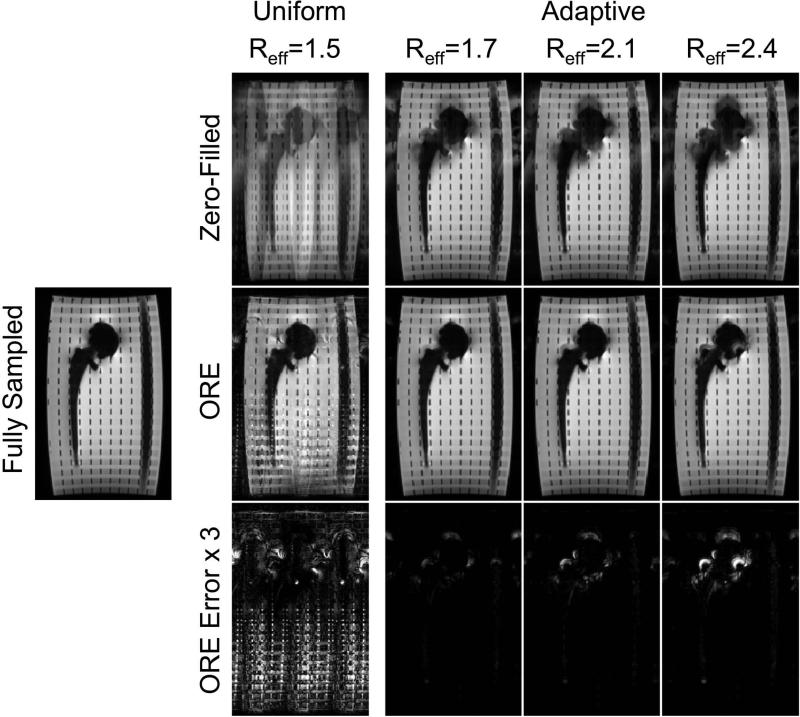

Figure 5 shows the reconstructed coronal image containing the hip implant for the sampling schemes of Figure 4. The error images show the absolute difference between the fully sampled image and the reconstructed images multiplied by a factor of 3 for emphasis. Residual aliasing is apparent for the uniform sampling scheme in which each off-resonance bin was sampled with an identical sampling pattern ( R = 1.5). Adaptive undersampling (scheme 2-4) with ORE reconstruction yields composite images with low error at reduction factors that exceed the uniform sampling. These errors appear localized to the areas of significantly far off-resonance.

Figure 5.

An adaptive sampling pattern across off-resonance bins dramatically improves reconstruction compared to a zero-filled reconstruction. ORE reconstruction of a uniform sampling pattern across off-resonance bins contains residual aliasing emphasized in the error map. An adaptive sampling pattern fully samples the central off-resonance bins and accelerates the sparse far-off-resonance bins. Aliasing of far-off-resonance is visible in the zero-filled images using adaptive sampling. This approach results in highly accurate reconstructions compared to uniform sampling. The ACS data used for calibration was not included in final reconstruction.

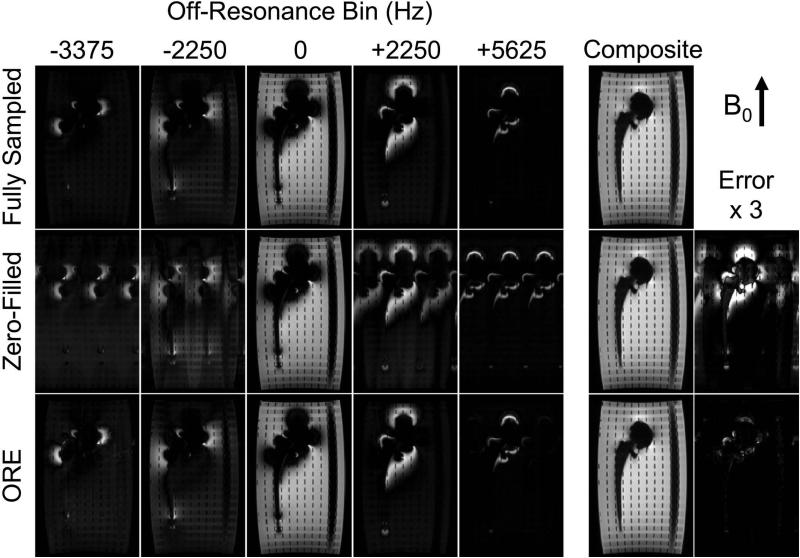

Figure 6 illustrates a subset of fully sampled off-resonance bins (top row), the aliasing patterns using the adaptive undersampling of scheme 3 (middle row), and the ORE reconstruction (bottom row). The on-resonance bin is fully sampled and therefore exhibits neither aliasing nor errors in reconstruction (not shown). The remaining off-resonance bins exhibit the expected aliasing along the direction perpendicular to B0 using a factor of R⊥ = 3. These results demonstrate the ability of ORE reconstruction to recover not only the individual off-resonance bins but also the spectral composite with a high degree of accuracy.

Figure 6.

ORE reconstruction effectively removes signal aliasing. The adaptive sampling scheme 3 from Figure 4 accelerates all but the central three bins, causing aliasing in the direction perpendicular to B0 seen in the zero-filled images. The aliased signal from each off-resonance bin is removed using ORE reconstruction. Only small residual aliasing from ORE is present in the error map from the far off-resonance bins that contain signal directly adjacent to the implant. The ACS data used for calibration was not included in this reconstruction.

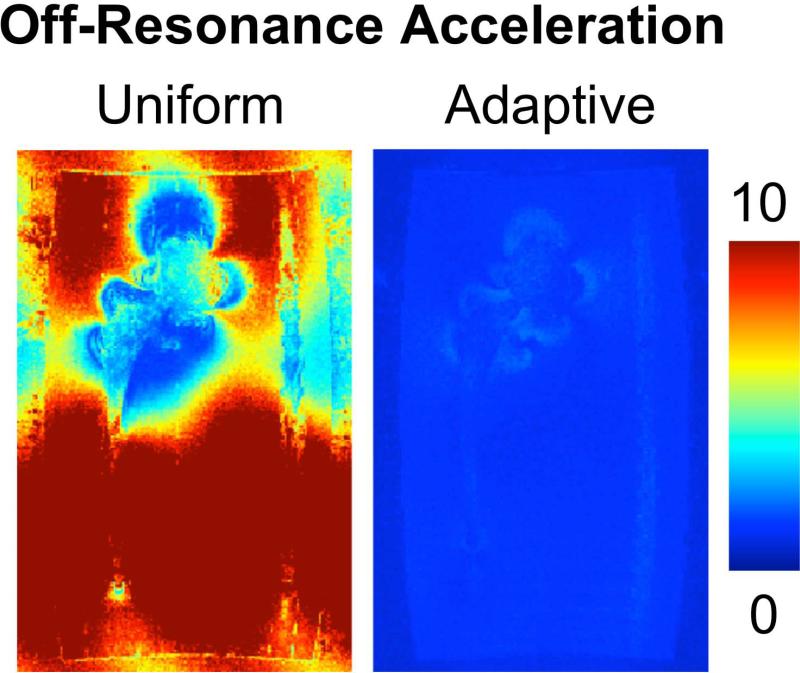

Figure 7 shows the noise maps of a uniform (left) and an adaptive (right) undersampling pattern. A high degree of noise amplification is evident in areas far from the metal implant, ie: close to on-resonance, when using a uniform sampling pattern across all bins. The adaptive sampling pattern produces significantly lower noise enhancement in regions close to on-resonance because they were fully sampled in sampling scheme 3. The area of far off-resonance has a slightly higher noise-amplification due to the larger acceleration factor of those bins compare to uniform sampling.

Figure 7.

Noise maps highlight the noise enhancement in undersampled areas without adequate spatial sensitivity variation using a uniform sampling pattern. An adaptive off-resonance acceleration scheme has relatively little noise enhancement and is contained to regions of far off-resonance that were undersampled.

Figure 8 presents the results of ORE reconstruction using a total knee replacement phantom and several undersampling schemes ( R = 3) in different directions. Overlap of aliased signal is evident in the negative off-resonance bin with undersampling in the direction perpendicular to B0 and in the positive off-resonance bin with undersampling in the direction parallel to B0. The errors in the ORE composite images are visible. Undersampling the negative off-resonance bins in a direction parallel to B0 ( R-∥ = 3) and the positive off-resonance bins in a direction perpendicular to B0 ( R+⊥ = 3) provides the least amount of aliased signal overlap and displays an ORE reconstruction with the least error.

Figure 8.

Multidimensional ORE acceleration can control the aliasing to improve reconstruction. Sampling can exploit the known dipole nature of the off-resonance. Undersampling the negative off-resonance bins in a direction parallel to B0 ( R-∥ = 3) and the positive off-resonance bins in a direction perpendicular to B0 ( R+⊥ = 3) provides the least amount of aliased signal overlap and displays an ORE reconstruction with the least error. The ACS was not included in the zero-filled images but was included in the composite images.

Discussion

In this work we have demonstrated the feasibility of using the spatial sensitivities of the off-resonance to accelerate spatial encoding. This provides an independent method of acceleration that could be combined with current methods like parallel imaging. Although combination of acceleration methods is beyond the scope of this study, ORE may provide the additional acceleration needed for in-vivo imaging with FPE techniques.

Other PI reconstruction algorithms such as SPIRIT (34) could be applied to ORE reconstruction. Image based techniques (eg. SENSE (26) and mSENSE (35)) would likely work as well, so long as the sensitivity patterns of the off-resonance bins could be properly estimated .

This work also investigated the unique opportunity to independently accelerate the signed components of off-resonance relative to the B0 field direction. The different magnitudes of the positive and negative components of the dipole (18,19) facilitates acceleration not only in different directions with respect to B0, but by different magnitudes. For example, a sampling strategy can accelerate negative off-resonance bins more aggressively in the direction parallel to B0 and positive off-resonance bins more aggressively in the direction perpendicular to B0.

The artifacts associated with the undersampling pattern will manifest at the off-resonance bin level as would be expected. When an independent and unique sampling pattern is used for each off-resonance bin, the artifacts combine incoherently in the spectral composite. This is different from PI techniques, in which all receiver channels have the same sampling pattern and therefore aliasing pattern.

This method of acceleration is insensitive to the position and extent of the off-resonance within the FOV. The off-resonance from a total hip prosthesis, for example, spans the majority of the superior/inferior prescribed dimension and offers little opportunity for reduced field of view methods. Therefore, ORE has a distinct advantage compared to reduced field of view methods of acceleration that require the off-resonance needs to be centered in the FOV (10).

The ability of ORE to provide adequate spatial encoding for acceleration depends on the spatial sensitivity offered by each MSI off-resonance bin. For a given RF pulse bandwidth and spacing, a large metallic implant or one with very high susceptibility, like stainless-steel, provides many off-resonance bins with spatial sensitivities useful for acceleration. Conversely, in the case of minimal off-resonance, only the central on-resonance bin will contain signal. The adaptive undersampling schemes implemented in this study preserve the signal in bins close to on-resonance and exploit the sparse far-off-resonance signal. Because the three central bins are fully sampled in our implementation of ORE, the situation with little to no off-resonance will be reconstructed without error. This important advantage of the sampling flexibility eliminates the risk of suboptimal spatial sensitivity variation when off-resonance is minimal.

The retrospective sampling schemes used in this study were set based on a priori knowledge of the off-resonance of implants at 1.5 T. Higher field strengths and/or susceptibility values will lead to increased off-resonance, effectively spreading the off-resonance across bins. The optimal degree of acceleration will depend on the field strength, RF pulse bandwidth, and field of view as well as the size, geometry, and susceptibility of the implant. If a priori knowledge of the implant is not know, a pre-scan could be used to investigate the extent of off-resonance as previously shown by Hargreaves et al. (36) to adapt the sampling scheme.

The SNR penalty of ORE acceleration is not fully understood. An adaptive off-resonance reduction factor effectively creates a SNR penalty that is a function of off-resonance. The highly accelerated off-resonance bins contain a relatively small fraction of the composite signal. Therefore, SNR of the spectral composite image is dominated by the SNR of the central frequency bins that are fully sampled. The SNR penalty of ORE acceleration was minimized in this study by preserving the majority of SNR from the central frequency bins.

The g-factor metric in PI reconstruction arises as a result of coil sensitivities being too similar in a given location, which ill-conditions the matrix inversion core to parallel imaging reconstruction. The noise propagation results in this study showed high noise amplification resulting from a uniform sampling pattern across frequency bins. Although not shown, the sensitivity patterns that contributed to signal in the regions of high noise amplification are indeed similar. This experiment in this study underscores the ability to utilize the developments of PI for the analysis of ORE performance.

The sampling flexibility of MSI methods enables an adaptive off-resonance sampling scheme across off-resonance bins. We demonstrated that ORE is feasible when most signal content is contained in the central frequency bins, which will always be the case for non-selective MSI. However, for slab-selective methods, the signal content would be in the central frequency bins for only the central slice. Signal content from non-central slices would be shifted into peripheral frequency bins. For that reason, the adaptive sampling pattern used in this study would be unsuitable for selective MSI. While it might be possible to reduce scan time using the spatial distribution of off-resonance from both metal and a superimposed selective gradient, it is not readily apparent at this time. As an alternative to superimposing a slab-selection gradient, spatial selection can be achieved with non-selective refocusing (37) or with multichannel receiver coils.

Future work will extend this method to all three dimensions for non-selective MSI and investigate several opportunities for optimization including an independent ACS size for each off-resonance bin. For example, a larger ACS size could be used on far off-resonance bins that contain signal dominated by high spatial frequencies.

In summary, we have shown the feasibility of accelerating acquisitions using the spatial distribution of off-resonance in the presence of metal. The method is straightforward to implement, avoids the hardware constraints of conventional PI, and is insensitive to the position of off-resonance within the FOV. ORE could potentially be used to reduce scan time for MAVRIC/SEMAC methods and may prove to be critical for enabling in-vivo imaging near metal with FPE methods.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Gary Gold for use of the knee phantom, Miki Lustig for sharing his GRAPPA code, and Jeremy Gordon for helpful discussions. We gratefully acknowledge the NIH (R01 DK083380, R01 DK088925, R01 NS065034) and GE Healthcare for their support.

References

- 1.Wolf BR, Lu X, Li Y, Callaghan JJ, Cram P. Adverse outcomes in hip arthroplasty: long-term trends. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:e103. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ravi B, Croxford R, Reichmann WM, Losina E, Katz JN, Hawker GA. The changing demographics of total joint arthroplasty recipients in the United States and Ontario from 2001 to 2007. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010. JAMA. 2012;308:1227–1236. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolland BJ, Culliford DJ, Langton DJ, Millington JP, Arden NK, Latham JM. High failure rates with a large-diameter hybrid metal-on-metal total hip replacement: clinical, radiological and retrieval analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:608–615. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B5.26309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D ale H, Fenstad AM, Hallan G, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen AB, Kärrholm J, Garellick G, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Mäkelä K, Engesæter LB. Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop. 2012;83:449–458. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.733918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White LM, Kim JK, Mehta M, Merchant N, Schweitzer ME, Morrison WB, Hutchison CR, Gross AE. Complications of total hip arthroplasty: MR imaging-initial experience. Radiology. 2000;215:254–262. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.1.r00ap11254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potter HG, Nestor BJ, Sofka CM, Ho ST, Peters LE, Salvati EA. Magnetic resonance imaging after total hip arthroplasty: evaluation of periprosthetic soft tissue. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1947–1954. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toms AP, Marshall TJ, Cahir J, Darrah C, Nolan J, Donell ST, Barker T, Tucker JK. MRI of early symptomatic metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective review of radiological findings in 20 hips. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu W, Pauly KB, Gold GE, Pauly JM, Hargreaves BA. SEMAC: Slice Encoding for Metal Artifact Correction in MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:66–76. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch KM, Lorbiecki JE, Hinks RS, King KF. A multispectral three-dimensional acquisition technique for imaging near metal implants. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:381–390. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koch KM, Brau AC, Chen W, Gold GE, Hargreaves BA, Koff M, McKinnon GC, Potter HG, King KF. Imaging near metal with a MAVRIC-SEMAC hybrid. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:71–82. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch KM, Hargreaves BA, Pauly KB, Chen W, Gold GE, King KF. Magnetic resonance imaging near metal implants. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32:773–787. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koch KM, King KF, Carl M, Hargreaves BA. Imaging near metal: The impact of extreme static local field gradients on frequency encoding processes. Magn Reson Med. JUL 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1002/mrm.24862. DOI: 10.1002/mrm.24862. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balcom BJ, Macgregor RP, Beyea SD, Green DP, Armstrong RL, Bremner TW. Single-Point Ramped Imaging with T1 Enhancement (SPRITE). J Magn Reson A. 1996;123:131–134. doi: 10.1006/jmra.1996.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grodzki DM, Jakob PM, Heismann B. Ultrashort echo time imaging using pointwise encoding time reduction with radial acquisition (PETRA). Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:510–518. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han H, Green D, Ouellette M, MacGregor R, Balcom BJ. Non-Cartesian sampled centric scan SPRITE imaging with magnetic field gradient and B0(t) field measurements for MRI in the vicinity of metal structures. J Magn Reson. 2010;206:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Artz NS, Hernando D, Taviani V, Samsonov A, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Spectrally resolved fully phase-encoded three-dimensional fast spin-echo imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2013 Mar 11; doi: 10.1002/mrm.24704. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24704. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schenck JF. The role of magnetic susceptibility in magnetic resonance imaging: MRI magnetic compatibility of the first and second kinds. Med Phys. 1996;23:815–850. doi: 10.1118/1.597854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch KM, Papademetris X, Rothman DL, de Graaf RA. Rapid calculations of susceptibility-induced magnetostatic field perturbations for in vivo magnetic resonance. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:6381–6402. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/24/007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Worters PW, Sung K, Stevens KJ, Koch KM, Hargreaves BA. Compressed-Sensing multispectral imaging of the postoperative spine. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37:243–248. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sveinsson B, Worters PW, Gold GE, Hargreaves BA. Fast Imaging of Metallic Implants by Data Subsampling.. Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of the ISMRM; Salt Lake City, UT. 2013.p. 0557. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nittka M, Otazo R, Rybak LD, Block KT, Geppert C, Sodickson DK, Recht MP. Highly Accelerated SEMAC Metal Implant Imaging Using Joint Compressed Sensing and Parallel Imaging.. Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of the ISMRM; Salt Lake City, UT. 2013.p. 2558. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch KM, King KF. Combined Parallel Imaging and Compressed Sensing on 3D Multi-Spectral Imaging Near Metal Implants.. Proceedings of the 19th Annual Meeting of the ISMRM; Montreal, Canada. 2011.p. 3172. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu W, Deng J, Lu Y, Gold G, Hargreaves B. POCS-based Compressive Slice Encoding for Metal Artifact Correction.. Proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting of the ISMRM; Montreal, Canada. 2011.p. 3174. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sodickson DK, Manning WJ. Simultaneous acquisition of spatial harmonics (SMASH): fast imaging with radiofrequency coil arrays. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:591–603. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pruessmann KP, Weiger M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P. SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:952–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, Haase A. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA). Magn Reson Med. 2002;47:1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hennig J, Welz AM, Schultz G, Korvink J, Liu Z, Speck O, Zaitsev M. Parallel imaging in non-bijective, curvilinear magnetic field gradients: a concept study. MAGMA. 2008;21:5–14. doi: 10.1007/s10334-008-0105-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stockmann JP, Ciris PA, Galiana G, Tam L, Constable RT. O-space imaging: Highly efficient parallel imaging using second-order nonlinear fields as encoding gradients with no phase encoding. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:447–456. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schultz G, Ullmann P, Lehr H, Welz AM, Hennig J, Zaitsev M. Reconstruction of MRI data encoded with arbitrarily shaped, curvilinear, nonbijective magnetic fields. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:1390–1403. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karimi H, Dominguez-Viqueira W, Cunningham CH. Spatial encoding using the nonlinear field perturbations from magnetic materials. Magn Reson Med. 2013 Sep 16; doi: 10.1002/mrm.24950. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24950. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velikina JV, Alexander AL, Samsonov A. Accelerating MR parameter mapping using sparsity-promoting regularization in parametric dimension. Magn Reson Med. 2012 Dec 4; doi: 10.1002/mrm.24577. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24577. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen CA, Chen W, Goodman SB, Hargreaves BA, Koch KM, Lu W, Brau AC, Draper CE, Delp SL, Gold GE. New MR imaging methods for metallic implants in the knee: artifact correction and clinical impact. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33:1121–1127. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lustig M, Pauly JM. SPIRiT: Iterative self-consistent parallel imaging reconstruction from arbitrary k-space. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:457–471. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J, Kluge T, Nittka M, Jellus V, Kuehn B, Kiefer B. Parallel acquisition techniques with modified SENSE reconstruction (mSENSE).. Proceedings of the 1st Wurzburg Workshop on Parallel Imaging; Wurzburg. 2001.p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hargreaves BA, Gold GE, Pauly JM, Pauly KB. Adaptive Slice Encoding for Metal Artifact Correction.. Proceedings of the 18th Annual Meeting of the ISMRM; Stockholm, Sweden. 2010.p. 3083. [Google Scholar]

- 37.den Harder C, Blume U, Bos C. MR Imaging near Metallic Implants using Selective Multi-Acquisition with Variable Resonances Image Combination.. Proceedings of the 20th Annual Meeting of the ISMRM; Melbourne, Australia. 2012.p. 2432. [Google Scholar]