Abstract

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the leading cause of cancer mortality among women worldwide. The life-threatening infection caused by HPV demands the need for designing anticancerous drugs. In the recent years, different compounds from natural origins, such as carrageenan, curcumin, epigallocatechin gallate, indole-3-carbinol, jaceosidin, and withaferin, have been used as a hopeful source of anticancer therapy. These compounds have been shown to suppress HPV infection by different researchers. In the present study, we explored these natural inhibitors against E6 oncoprotein of high-risk HPV-16, which is known to inactivate the p53 tumor suppressor protein. A robust homology model of HPV-16 E6 was built to anticipate the interaction mechanism of E6 oncoprotein with natural inhibitory molecules using a structure-based drug designing approach. Docking analysis showed the interaction of these natural compounds with the p53-binding site of E6 protein residues 113-122 (CQKPLCPEEK) and helped the restoration of p53 functioning. Docking analysis, besides helping in silico validation of natural compounds, also helps understand molecular mechanisms of protein-ligand interactions.

Keywords: DNA probes HPV, molecular docking, neoplasms, plant products

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV), a virus from the papillomavirus family, accounts for 5.2% of all cancers worldwide and is also the causative agent of a subset of anogenital, head and neck cancers, and cervical cancer [1, 2]. Amongst these, cervical cancer contributes the most to cancer mortality in women worldwide, with an estimated 49,300 diagnoses and 274,000 deaths annually [3]. Although there are more than 200 types of HPV identified, the most commonly associated with cervical cancer are 'high-risk' HPV-16 and HPV-18, responsible for about 62.6% and 15.7% of cervical cancers, respectively [4]. Besides, among all the HPV-associated cancers, the proportion attributable to HPV types 16 and 18 is 63-80% of penile cancers, 80-86% of vulva/vaginal cancers, 93% of anal cancers, and 89-95% of oropharyngeal cancers [5]. HPV-16 and HPV-18 remain the primary targets for anticancer drug development.

The E6 and E7 onco-proteins have been shown to interact specifically with the p53 and pRb tumor suppressor proteins, respectively [6]. Both pRb and p53 negatively regulate the cell cycle and also appear to inhibit G0-G1 and G1-S phase transitions. These interactions apparently play important roles in the induction of cell immortality. The importance of p53-mediated apoptosis has been recognized in terms of the maintenance of homeostasis, as well as the prevention of neoplastic transformation. E6 forms a ternary complex with p53 and E6AP (E6 associated protein), resulting in the degradation of p53 via the ubiquitination pathway [7].

HPV has been known as a causative agent for cervical cancer for 3 decades, but effective treatment against HPV infection is still unavailable [8]. Natural products have been identified as promising sources of drugs for treatment and prevention of cancer in recent years [9].

Carrageenan is known to prevent the binding of HPV virions to cells. It can also block HPV infection through a second, post attachment heparan sulfate-independent effect [10].

Bava et al. [11] demonstrated that curcumin sensitizes cervical cancer cells to the therapeutic effect of taxol, acting in the down-regulation of both nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and the threonine/serine kinase AKT pathway. Curcumin is cytotoxic to cervical cancer cells in a concentration-dependent and time-dependent manner, and the cytotoxicity is higher in HPV-infected cells. The authors confirmed the inhibitory action of curcumin on NF-κB activation, through the degradation of IκB, and on AP-1 binding, which results in the downregulation of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) and increased tumor cell apoptosis [11]. Moreover, it was shown that curcumin downregulates the expression of E6 and E7 proteins of HPV-16, resulting in loss of the transforming phenotype and the cessation of cellular growth. Singh and Singh [12] explored other molecular mechanisms exerted by curcumin in cervical cancer cells, showing that it inhibits telomerase activity, the RAS and ERK signaling pathway, cyclin D1, COX-2, and inducible nitric oxide synthase activity.

Withaferin A (WA) is the major active component of the Indian medicinal plant Withania somnifera, with antitumor, antiangiogenic, and radiosensitizing activity [13, 14]. An in vitro and in vivo study conducted by Munagala et al. [15] showed the inhibitory effect of WA against the proliferation of cervical cancer cells. WA was shown to downregulate the expression of HPV E6 oncoprotein and restore the p53 pathway, resulting in apoptosis of cervical cancer cells [15].

(-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), the most abundant and active tea catechin, has antiviral and antitumor properties. According to a clinical study, EGCG was effective in patients with HPV-infected cervical lesions when delivered in the form of ointment or capsule [16]. A study conducted by Qiao et al. [17] showed the inhibition effect of EGCG on the growth of CaSki (HPV-16 positive) and HeLa (HPV-18 positive) cells in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. Their results also observed that EGCG could inhibit the expression of HPV E6/E7. Lee et al. [18] isolated jaceosidin from the methanol (MeOH) extract of Artemisia argyi and reported its inhibitory effects on binding between oncoproteins and tumor suppressor p53. Indole-3-carbinol (I3C), found in cruciferous vegetables, such as cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, and brussel sprouts,was demonstrated to have anti-estrogenic activities in cervical cells [19].

The purpose of this in silico study was to observe the interaction between active compounds obtained from natural products used for the treatment against HPV. In this study, a three-dimensional structure of E6 protein of HPV type 16 was modeled using the Phyre 2 server, and structural refinement and energy minimization were performed by the YASARA Energy Minimization Server. In order to reveal the interaction between E6 oncoprotein with natural ligands, docking analysis was performed using the AutoDock tool.

Methods

Hardware and software

The study was carried out on a Dell Workstation with a 2.26 GHz processor, 6 GB RAM, and 500 GB hard drive running in the Windows operating system. Bioinformatics software, such as AutoDock4.0 and online resources, were used in this study.

E6 of HPV-16

E6 protein of HPV-16 was selected as the drug target. The HPV-16 E6 (GenBank ID: AAD33252.1) protein sequence was retrieved from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Protein structure prediction and validation of drug target

For modeling of the three-dimensional structure of the E6 protein, Phyre 2 server [20] was used. Structural refinement and energy minimization of the predicted model were carried out using the YASARA Energy Minimization Server [21]. The refined model reliability was assessed through Procheck [22], ProSA-web [23], ProQ [24], and Verify-3D [25]. The refined model was further verified by the ERRAT server [26].

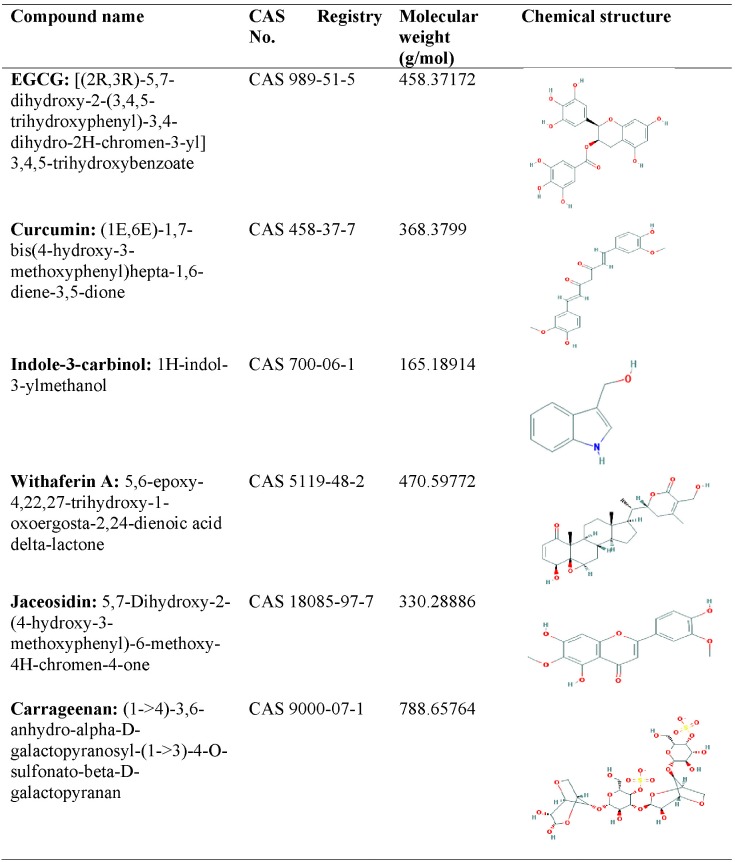

Ligand preparation

Chemical structures of natural compounds (carrageenan, curcumin, EGCG, I3C, jaceosidin, WA), along with CAS (Chemical Abstracts Service) registry numbers, reported in the literature were retrieved from the PubChem database (Fig. 1) [27].

Fig. 1.

Natural compounds reported to use against human papillomavirus infection.

Protein-ligand docking

Protein-ligand docking studies were performed using the AutoDock 4.2 program [28]. It is one of the most widely used methods for protein-ligand docking. All the pre-processing steps for ligand and protein files were performed using AutoDock Tools 1.5.4 (ADT), which has been released as an extension suite to the Python Molecular Viewer [28]. ADT was used to prepare the receptor molecule (HPV-16 E6) by adding all hydrogen atoms into carbon atoms of the receptor, and Kollman charges were also assigned. For docked ligands, non-polar hydrogens were also added. Gasteiger charges were assigned and torsions degrees of freedom were allocated by ADT.

The Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) was applied to model the interaction pattern between the E6 oncogenic protein and selected inhibitors. The grid maps representing the receptor proteins in the docking process were calculated using AutoGrid (part of the AutoDock package). A grid of 50, 50, and 50 points in the x, y, and z directions was centered on the p53-binding sites of E6 proteins. For all docking procedures, 10 independent genetic algorithm runs with a population size of 150 were considered for each molecule under study. A maximum number of 25 × 105 energy evaluations, 27,000 maximum generations, a gene mutation rate of 0.02, and a crossover rate of 0.8 were used for the LGA. Autodock was run in order to prepare corresponding docking log file (DLG) files for further analysis.

Visualization

The visualization of structure files was done using the graphical interface of the ADT tool and the PyMol molecular graphics system (http://www.pymol.org).

Results and Discussion

Tertiary structure modeling and validation

E6 protein of HPV type 16 has 158 amino acids in its protein sequence. Since the three-dimensional structure of E6 was not available, its structure model was predicted using the Phyre 2 server by taking chain C of the crystal structure of full-length HPV oncoprotein e62 in complex with the lxxll peptide of ubiquitin ligase e6ap (PDB ID: 4GIZ) as a structural template. The query coverage of the target-template alignment was 90% with 96% identity. The predicted structure was then subjected to the Yet Another Scientific Artificial Reality Application (YASARA) Energy Minimization Server for structural refinement. The total energy for the refined structure obtained from the YASARA Energy Minimization Server was -48,054.9 kcal/mol (score, -2.55), whereas prior to energy minimization, it was 81,463,636,897 kcal/mol (score, -4.21).

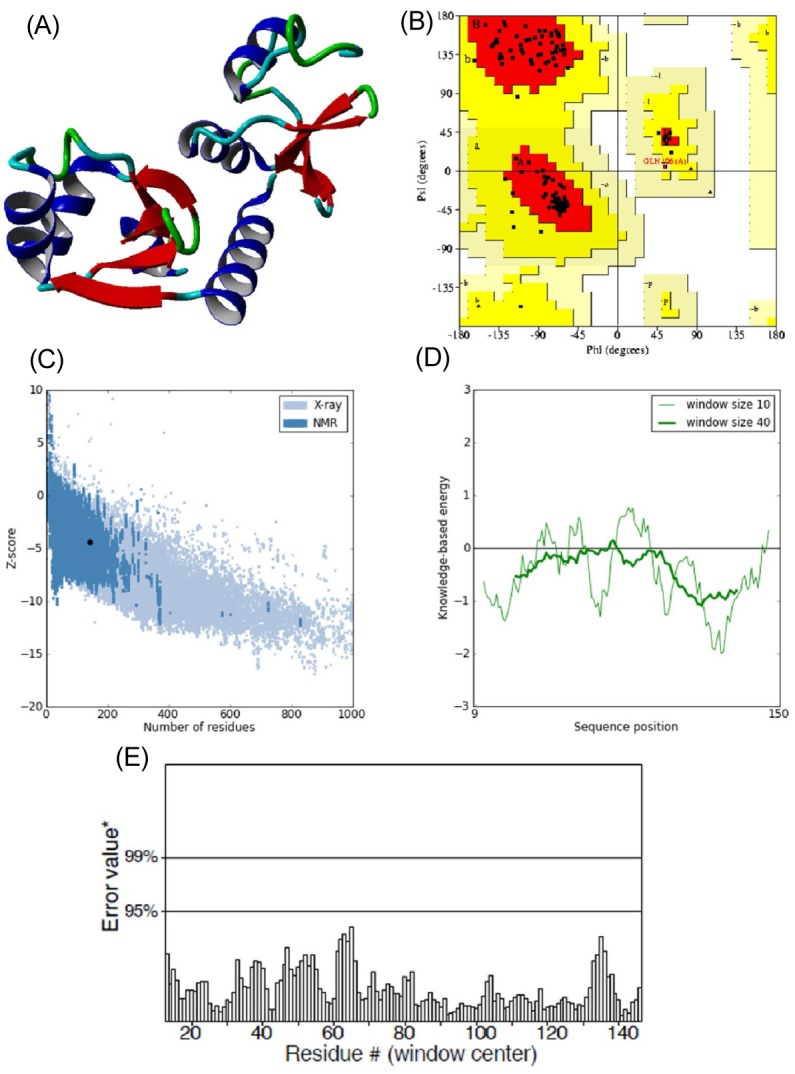

The stereochemistry of the refined model (Procheck analysis) (Fig. 2A) revealed that 99.2% of residues were situated in the most favorable region and additional allowed regions, and 0.8% (Gln106) of residues were in the generously allowed region, whereas none of the residues fell in the disallowed region of the Ramachandran plot (Fig. 2B). ProSA-web evaluation revealed a compatible Z score (Fig. 2C) value of -4.34, which is well within the range of native conformations of crystal structures [23]. The overall residue energies of the E6 3D model were largely negative except for one peak (Fig. 2D). The 3D model of HPV-16 E6 protein showed an LG score of 2.531 by Protein Quality Predictor (ProQ) tool, implying a high accuracy level of the predicted structure. A ProQ LG score >2.5 is necessary for suggesting that a model is of very good quality [24].

Fig. 2.

(A) 3D structure of predicted human papillomavirus 16 (HPV-16) E6 model. (B) Ramachandran plot of predicted E6 model (the red, dark yellow, and light yellow regions represent the most favored, allowed, and generously allowed regions). (C) ProSA-web Z-scores of all protein chains in PDB determined by X-ray crystallography (light blue) and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with respect to their length. The Z-score of E6 was present in the range represented in black dot (D) Energy plot for the predicted E6 of HPV-16. (E) ERRAT plot for residue-wise analysis of homology model.

Similar assumptions were achieved using the ERRAT plot (Fig. 2E), where the overall quality factor was 91%. All of these outcomes recommended the reliability of the proposed model.

Docking analysis of HPV-16 E6 with natural ligands

As all natural ligands (inhibitors) were found to be docked in various conformations and with varying binding energies, the lowest energy conformation was selected. Upon docking, the high-ranked binding energies of modeled structures of E6 oncoprotein with natural ligands were obtained (Table 1). HPV E6 degrades the p53 tumor suppressor protein. To accomplish the process of degradation, E6 proteins bind and modify the target specificity of the ubiquitin ligase E6AP. Based on the resolved structure of HPV-16 E6 by Zanier et al. [29], Cherry et al. [30] revealed in their docking analysis study that few flavonoid compounds bind in the hydrophobic pocket of the E6 and E6AP interface and mimic the leucines in the conserved α-helical motif of E6AP. Another study also showed that the biological activities of E6 are mediated by the interaction of E6 with the LXXLL motif of E6AP [31]. In our study, the E6 protein of HPV-16 showed one LXXLL motif (103LCDLL107). Out of six natural compounds included in our study, three (carrageenan, EGCG, and I3C) were found to interact with the LXXLL motif of HPV-16 E6 by forming a hydrogen bond with Leu106. According to Crook et al. [32], the p53-binding site is around amino acid residues 113-122 (CQKPLCPEEK) of HPV-16 E6 protein. The active site of the model was then analyzed based on the docking interaction of E6 with the p53-binding site with all 6 natural ligands.

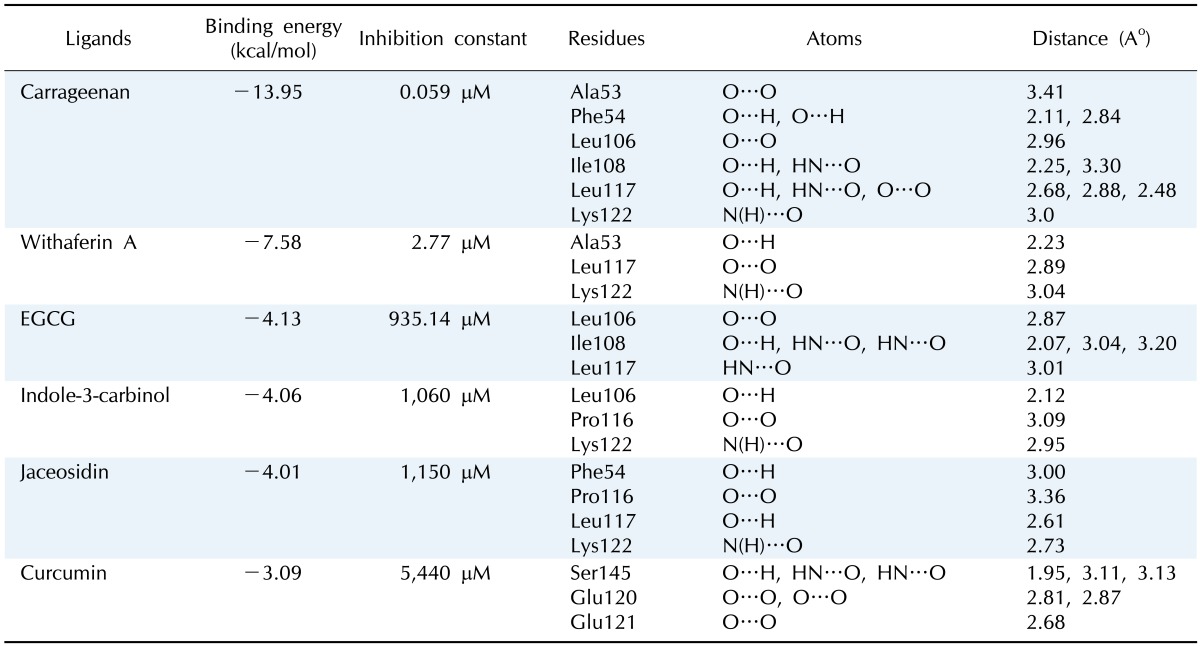

Table 1.

Polar contact information from docking calculations between ligands and protein

EGCG, epigallocatechin gallate.

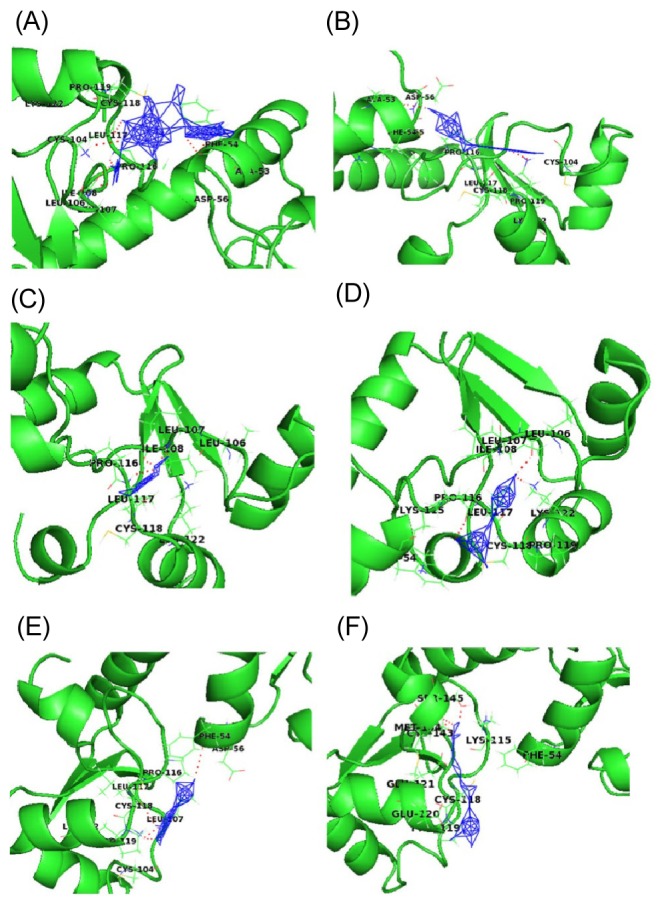

Fig. 3 shows a docked pose of six ligand molecules with E6 protein, which showed almost similar docking results. The detailed interactions are given in Table 1. Each ligand interacts with the receptor at the p53-binding site. Among the 6 different ligands, carrageenan showed the lowest binding energy (-13.95 kcal/mol) and inhibition constant (0.059 µM) for the protein-ligand complex. Carrageenan was found to interact with the E6 residues Ala53, Phe54, Leu106, Ile108, Leu117, and Lys122 by forming hydrogen bonds. As mentioned in the introduction, carrageenan blocks HPV infection [10]; from our docking study, it might be revealed that the block of HPV infection might be due the high binding affinity of carrageenan towards the p53-binding site of E6 protein.

Fig. 3.

Interaction profile of E6 with natural ligands carrageenan (A), withaferin A (B), epigallocatechin gallate (C), indole-3-carbinol (D), jaceosidin (E), and curcumin (F) showing interaction of ligands with active site residues of E6 by forming hydrogen bonds, shown in dotted lines.

WA showed the second lowest binding energy of -7.58 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 2.77 µM. During docking with the receptor hydrogen bond, interactions were found with three residues (Ala53, Leu117, and Lys122) of E6.The other three compounds-EGCG, I3C and jaceosidin-were also found to interact with E6 protein with binding energies of -4.13, -4.06, and -4.01 kcal/mol, respectively. Leu106, Ile108, and Leu117 were the interacting residues of the receptor proteins with EGCG, whereas I3C interacted with Leu106, Pro116, and Lys122; Jaceosidin interacted with Phe54, Pro116, Leu117, and Lys122.

Curcumin was found to interact with E6 protein with less affinity (binding energy of -3.09 kcal/mol). All natural ligands were reported to inhibit HPV infection; our docking study also revealed the in silico validation of the inhibition. HPV-16 is known for causing high-risk cervical cancer. All ligands were found to interact with E6 oncoprotein of HPV-16 with significant binding energy and with amino acid residues known for p53 binding. This interaction might prevent E6 protein from interacting with host p53 protein, which may correlate with why these natural compounds are used to treat HPV infections.

Conclusion

Different natural products have been identified and used as promising drug sources against cancer caused by HPV. Advancement in bioinformatics and computational biology are proficient invalidating those natural drugs through in silico approaches. E6 proteins of high-risk HPV 16 inactivate p53 by inducing its degradation, a process that requires a ternary complex between E6, E6AP, and p53. Low-risk HPVs, such as HPV-6 and HPV-11, do not have the ability to degrade p53. Thus, E6 of HPV-16 is of considerable interest for designing novel inhibitors to overcome the challenges of cervical cancer. A high-quality 3D model of E6 obtained through a computational approach and docking analysis employing AutoDock 4.2 in this study provided high-throughput validation. This in silico approach may be of interest in designing new drugs from natural sources against cervical cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to the Department of Biotechnology, MoS&T, Government of India, for their financial support to the Bioinformatics Centre, where this study was carried out. Grateful thanks to Shri D.S. Mehta, President, Kasturba Health Society; Dr. (Mrs.) P. Narang, Secretary, Kasturba Health Society; Dr. B.S. Garg, Dean, MGIMS; Dr. S.P. Kalantri, Medical Superintendent, Kasturba Hospital, MGIMS, Sevagram, and Dr. B.C. Harinath, Director, JBTDRC & Coordinator, Bioinformatics Centre for their encouragement and support.

References

- 1.Hoory T, Monie A, Gravitt P, Wu TC. Molecular epidemiology of human papillomavirus. J Formos Med Assoc. 2008;107:198–217. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(08)60138-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607–615. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parkin DM, Bray F. Chapter 2: The burden of HPV-related cancers. Vaccine. 2006;24(Suppl 3):S11–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan P, Howell-Jones R, Li N, Bruni L, de Sanjosé S, Franceschi S, et al. Human papillomavirus types in 115,789 HPV-positive women: a meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:2349–2359. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaturvedi AK. Beyond cervical cancer: burden of other HPV-related cancers among men and women. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(4 Suppl):S20–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheffner M, Munger K, Byrne JC, Howley PM. The state of the p53 and retinoblastoma genes in human cervical carcinoma cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5523–5527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hubbert NL, Sedman SA, Schiller JT. Human papillomavirus type 16 E6 increases the degradation rate of p53 in human keratinocytes. J Virol. 1992;66:6237–6241. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.6237-6241.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bharti AC, Shukla S, Mahata S, Hedau S, Das BC. Anti-human papillomavirus therapeutics: facts & future. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:296–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordaliza M. Natural products as leads to anticancer drugs. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:767–776. doi: 10.1007/s12094-007-0138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buck CB, Thompson CD, Roberts JN, Müller M, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Carrageenan is a potent inhibitor of papillomavirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e69. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bava SV, Puliappadamba VT, Deepti A, Nair A, Karunagaran D, Anto RJ. Sensitization of taxol-induced apoptosis by curcumin involves down-regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB and the serine/threonine kinase Akt and is independent of tubulin polymerization. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6301–6308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410647200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh M, Singh N. Molecular mechanism of curcumin induced cytotoxicity in human cervical carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;325:107–119. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharada AC, Solomon FE, Devi PU, Udupa N, Srinivasan KK. Antitumor and radiosensitizing effects of withaferin A on mouse Ehrlich ascites carcinoma in vivo. Acta Oncol. 1996;35:95–100. doi: 10.3109/02841869609098486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bargagna-Mohan P, Hamza A, Kim YE, Khuan Abby Ho Y, Mor-Vaknin N, Wendschlag N, et al. The tumor inhibitor and antiangiogenic agent withaferin A targets the intermediate filament protein vimentin. Chem Biol. 2007;14:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munagala R, Kausar H, Munjal C, Gupta RC. Withaferin A induces p53-dependent apoptosis by repression of HPV oncogenes and upregulation of tumor suppressor proteins in human cervical cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1697–1705. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn WS, Yoo J, Huh SW, Kim CK, Lee JM, Namkoong SE, et al. Protective effects of green tea extracts (polyphenon E and EGCG) on human cervical lesions. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:383–390. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiao Y, Cao J, Xie L, Shi X. Cell growth inhibition and gene expression regulation by (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate in human cervical cancer cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2009;32:1309–1315. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1917-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HG, Yu KA, Oh WK, Baeg TW, Oh HC, Ahn JS, et al. Inhibitory effect of jaceosidin isolated from Artemisiaargyi on the function of E6 and E7 oncoproteins of HPV 16. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;98:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan F, Chen DZ, Liu K, Sepkovic DW, Bradlow HL, Auborn K. Anti-estrogenic activities of indole-3-carbinol in cervical cells: implication for prevention of cervical cancer. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:1673–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieger E, Joo K, Lee J, Raman S, Thompson J, Tyka M, et al. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins. 2009;77(Suppl 9):114–122. doi: 10.1002/prot.22570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallner B, Elofsson A. Can correct protein models be identified? Protein Sci. 2003;12:1073–1086. doi: 10.1110/ps.0236803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisenberg D, Lüthy R, Bowie JU. VERIFY3D: assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:396–404. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colovos C, Yeates TO. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1511–1519. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Xiao J, Suzek TO, Zhang J, Wang J, Bryant SH. PubChem: a public information system for analyzing bioactivities of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W623–W633. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zanier K, Charbonnier S, Sidi AO, McEwen AG, Ferrario MG, Poussin-Courmontagne P, et al. Structural basis for hijacking of cellular LxxLL motifs by papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins. Science. 2013;339:694–698. doi: 10.1126/science.1229934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cherry JJ, Rietz A, Malinkevich A, Liu Y, Xie M, Bartolowits M, et al. Structure based identification and characterization of flavonoids that disrupt human papillomavirus-16 E6 function. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vande Pol SB, Klingelhutz AJ. Papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins. Virology. 2013;445:115–137. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crook T, Tidy JA, Vousden KH. Degradation of p53 can be targeted by HPV E6 sequences distinct from those required for p53 binding and trans-activation. Cell. 1991;67:547–556. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]