Abstract

Regulatory mechanisms that govern lineage specification of the mesodermal progenitors to become endothelial and hematopoietic cells remain an area of intense interest. Both Ets and Gata factors have been shown to have important roles in the transcriptional regulation in endothelial and hematopoietic cells. We previously reported Etv2 as an essential regulator of vasculogenesis and hematopoiesis. In the present study, we demonstrate that Gata2 is co-expressed and interacts with Etv2 in the endothelial and hematopoietic cells in the early stages of embryogenesis. Our studies reveal that Etv2 interacts with Gata2 in vitro and in vivo. The protein-protein interaction between Etv2 and Gata2 is mediated by the Ets and Gata domains. Using the embryoid body differentiation system, we demonstrate that co-expression of Gata2 augments the activity of Etv2 in promoting endothelial and hematopoietic lineage differentiation. We also identify Spi1 as a common downstream target gene of Etv2 and Gata2. We provide evidence that Etv2 and Gata2 bind to the Spi1 promoter in vitro and in vivo. In summary, we propose that Gata2 functions as a cofactor of Etv2 in the transcriptional regulation of mesodermal progenitors during embryogenesis.

Keywords: Etv2, Gata2, endothelial cell, hematopoietic cell

Introduction

Mesodermal progenitors daughter a variety of cell lineages, including cardiac, skeletal muscle, endothelial, and hematopoietic lineages. The mesodermal progenitors that parent endothelial and hematopoietic lineages appear first in the blood islands of the yolk sac (Keller et al., 1999) and then are found in the lateral plate mesoderm of the embryo proper. Regulation of the endothelial and hematopoietic lineage specification has stimulated intense interest (Chen et al., 2009; Eilken et al., 2009; Hirschi, 2012; Lancrin et al., 2009). A number of transcription factors and signaling pathways have been reported to play important roles in the regulation of endothelial and hematopoietic mesodermal progenitors (Zape and Zovein, 2011).

GATA transcription factors are characterized as having a conserved dual zinc finger domain. This family of transcription factors have the ability to bind to the consensus DNA motif [5′-(A/T)GATA(A/G)-3′] (Ko and Engel, 1993; Merika and Orkin, 1993). GATA factors are expressed in a tissue-specific manner. The hematopoietic Gata factors, Gata1, Gata2, and Gata3, are primarily expressed in the hematopoietic lineage (Shimizu and Yamamoto, 2005; Suzuki et al., 2011; Weiss and Orkin, 1995), whereas the nonhematopoietic Gata factors, Gata4, Gata5, and Gata6, are expressed in cardiac, liver, and intestinal tissues (Molkentin, 2000; Morrisey et al., 1996; Peterkin et al., 2005; Schachterle et al., 2012). Gata2 is abundantly expressed during embryogenesis and plays an important role in the specification of the hematopoietic lineage during embryogenesis (Vicente et al., 2012). Overxpression of Gata2 results in the induction of the hematopoietic lineage in Xenopus embryos (Maeno et al., 1996). Global deletion of Gata2 results in embryonic lethality at embryonic day (E)11.5, in part, due to anemia (Tsai et al., 1994). Both the primitive and the definitive hematopoietic programs are perturbed in Gata2 null mice. Although the endothelium in the Gata2 null embryo appears to be unaffected, recent studies have demonstrated that Gata2 may also have an important role in the transcriptional regulation of the endothelial lineage during development (Lugus et al., 2007). Gata2 regulates a number of endothelial genes, including PPet1, eNOS, Vecam1, and Endomucin (Dorfman et al., 1992; German et al., 2000; Gumina et al., 1997; Kanki et al., 2011).

Ets (E-twenty six) proteins are characterized by an evolutionarily conserved DNA-binding ETS domain. The Ets domain adapts a winged helix-turn-helix structure and binds to the G-G-A-A/T core DNA sequence (Hollenhorst et al., 2011). The members of this family play important roles in cell migration, cellular proliferation, differentiation, and oncogenic transformation (Hollenhorst et al., 2011). The Ets transcription factor family members are key regulators of endothelial and hematopoietic lineages as revealed using genetic mouse models (Lammerts van Bueren and Black, 2012; Meadows et al., 2011). For example, mice lacking Ets1 are viable and have normal development due to its redundant role with Ets2 (Bories et al., 1995; Muthusamy et al., 1995). This redundancy is further evident as the Ets1 and Ets2 double knockout embryos have perturbed angiogenesis and are lethal by E13.0 (Wei et al., 2009). Erg plays an essential role in multiple hematopoietic lineages and mutation of the Erg gene results perturbation of definitive hematopoiesis and adult hematopoietic stem cell function (Loughran et al., 2008). Etv6 null mice are lethal between E10.5–E11.5 due to a yolk sac angiogenesis defect although vasculogenesis in the embryo proper develops normally (Wang et al., 1997). Conditional knockout studies revealed that Etv6 is also essential for adult hematopoietic stem cell survival (Hock et al., 2004). In addition, Fli1 mutant embryos are lethal by E12.5 due to perturbed vascular integrity and evidence of hemorrhage (Spyropoulos et al., 2000).

Spi1 is a key Ets factor in the development of the myeloid and lymphoid lineages (Gangenahalli et al., 2005). The development of monocytes/macrophages and B lymphoid cells have been blocked in Spi1 null embryos (Scott et al., 1994). Transgenic studies have revealed that the transcriptional regulatory region of murine Spi1 spans a 91-kb genomic region (Li et al., 2001). DNase I hypersensitive site (DHS) mapping defined several regulatory modules in the 91-kb region, including the −14kb upstream distal enhancer and the proximal promoter (Hoogenkamp et al., 2007).

These studies support the conclusion that both Ets and Gata factors play important roles in hematopoietic and endothelial development. Investigation of the transcriptional regulation of Tal1 gene expression has revealed the cooperative interaction between Gata2, Fli1 and Elf1 in transactivation of Tal1 gene expression and hematopoietic development (Gottgens et al., 2002). Similar studies using the Gata2, Fli1 and Tal1 enhancers have shown that Gata factor (Gata2), Ets factor (Fli1), and Scl form a regulatory circuit during early hematopoietic development (Pimanda et al., 2007). Utilizing a ChIP-Seq technique, the same group has identified the genome-wide binding sites of Gata1/2, Fli1 and additional factors in primary megakaryocytes, demonstrating the co-occupancy between Gata1 and Fli1 (Tijssen et al., 2011).

We have previously reported that Nkx2-5 is one of the direct upstream regulators of Etv2 (Ferdous et al., 2009). Our laboratory and others have demonstrated that Etv2 mutant embryos are nonviable due to the absence of the endothelial and hematopoietic lineages (Ferdous et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2008). Kataoka et al. have reported that Etv2 plays an indispensible role in the progression of the Flk1+/Pdgfra+ primitive mesoderm to Flk1+/Pdgfra− vascular mesoderm through the regulation of a group of critical downstream target genes that govern vasculogenesis and hematopoiesis, including Tal1, Fli1, and Gata2 (Kataoka et al., 2011). Utilizing lineage tracing mouse models, we have shown that Etv2 is essential for endothelial and hematopoietic lineage specification and represses the cardiac lineage during embryogenesis (Rasmussen et al., 2011). We demonstrated that Etv2 is a downstream target of Flk1-p38-Creb signaling cascade and overexpression of Etv2 could rescue the defect of endothelial and hematopoietic development in Flk1 null embryoid bodies (Rasmussen et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2012). Elegant studies have demonstrated that Etv2 interacts with FoxC2 and regulates the endothelial molecular program through a composite Fox:Ets motif, which consists of a noncanonical forkhead site and an Ets site (De Val et al., 2008). The Fox:Ets motif has been identified in a number of endothelial genes, such as Flk1, Tal1, Notch 4, and Cdh5 (De Val et al., 2008). Recent studies have also revealed the functional role of Etv2 in hemato-endothelial development. The defect of hematopoietic development in Etv2 null cells can be rescued through overexpression of its downstream target gene, Scl/Tal1 (Wareing et al., 2012). Moreover, the conditional knockout of Etv2 by Hoxb6 Cre perturbs the vitelline plexus formation and intra-aortic hematopoiesis (Kataoka et al., 2013). Etv2 has also been shown to regulate the remodeling of the cranial and yolk sac vasculature at E9.5 (Kobayashi et al., 2013). The functional role of Etv2 orthologs in zebrafish (Etsrp) and Xenopus (Er71) have been well characterized. In contrast to the requirement of Etv2 for both hematopotic and endothelial lineages during murine embryogenesis, Xenopus Er71 is only essential for vasculogenesis, but not for hematopoiesis, during embryogenesis, and zebrafish Etsrp is required for vasculogenesis and myeloid development, not erythroid development (Neuhaus et al., 2010; Sumanas et al., 2008; Sumanas and Lin, 2006).

Involvement of Ets and Gata family proteins in hematopoietic and endothelial development led us to hypothesize that Ets and Gata proteins act in the same pathway or function as a protein complex to regulate downstream genes. In the present study, we focused on the interaction of Etv2 and Gata2 and we hypothesized that Etv2 and Gata2 may physically interact with each other to regulate a subset of target genes. In this study, we determined that Gata2 is co-expressed with Etv2 during embryogenesis and could serve as a cofactor with Etv2 as a complex regulating both endothelial and hematopoietic lineages. Furthermore, we have identified Spi1 as a downstream target of Etv2 and Gata2.

Material and Methods

DNA, RNA, RNAseq, cDNA synthesis and qPCR techniques

All of the plasmid subcloning and DNA mutagenesis were performed with standard PCR techniques and verified by DNA sequencing. RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and treated with DNase I (Qiagen). For RNAseq, the raw RNAseq data were mapped to the mouse genome (mm09) by Bowtie (version 0.12.9) with default parameters (Langmead et al., 2009), yielding an average of approximately 30 million mappable reads per sample. The expected counts (EC) of each gene were estimated by RSEM (Li and Dewey, 2011) and median-normalized by EBseq (Leng et al., 2013) across samples. cDNA was synthesized with SuperScript VILO reagent (Invitrogen). qPCR was utilized to examine the gene expression profile using ABI Taqman probes as previously described (Rasmussen et al., 2011).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation assay

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) were performed as described previously (Shi and Garry, 2010). For EMSA, the double stranded oligonucleotide (5′ GCCCTTCGATAAAATCAGGAACTTGTGCT 3′) within the Spi1 proximal promoter was labeled with 32P using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The labeled probe was then incubated with the in vitro synthesized Etv2 or Gata2 protein and analyzed using a 4% non-denaturing TBE gel. For the supershift, rabbit IgG, anti-HA (Y11) or anti-Myc (A14) sera were added to the reaction prior to running the gel. For the ChIP assay, ES cell lines expressing HA-tagged Etv2 were utilized due to the lack of antibodies for the endogenous Etv2 protein. The chromatin complex from embryoid bodies was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA (Y-11) or Gata2 (H-116) sera. The eluate DNA was analyzed by qPCR with specific primers flanking the Ets and Gata motifs in the proximal promoter (forward: 5′ CGGCCAGAGACTTCCTGTAG 3′ and reverse: 5′ GCCAGCACAAGTTCCTGATT 3′). Gapdh primers were utilized as a negative control of nonspecific binding as described previously (Rasmussen et al., 2012).

Cell culture, cell transfection and transcriptional assays

C2C12 and 293T cells were maintained in growth medium (DMEM supplied with 10% FBS) and transfected using Lipofectamine/Plus reagent (Invitrogen) and Fugene HD reagent (Promega), respectively. Transcriptional assays were performed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega). The firefly luciferase activity was normalized to the Renilla luciferase (pRL-CMV reporter) and expressed as RLU (relative luciferase unit).

Western blot, co-immunoprecipitation, GST pulldown and immunohistochemical techniques

Western blot, co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) were performed as described in our previous study (Shi et al., 2012). Primary antibodies used in the Western blot and immunoprecipitation analyses included: mouse anti-Flag (M2; Sigma), rabbit anti-Gata2 (H-116; Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-HA (Y-11; Santa Cruz), and rat anti-HA (3F10; Roche) sera. Primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry included: chicken anti-green fluorescent protein (1:500; Abcam, ab13970), goat anti-CD31/Pecam1 (1:500; R&D, AF3628), rat anti-Gata1 (1:1000; Santa Cruz, sc-265 X), rabbit anti-Gata2 (1:500; Novus Biologicals, NBP1-82581), goat anti-Gata4 (1:500; R&D, AF2606), and rabbit anti-Flk1 (1:500; Cell Signaling, 55B11) sera. Secondary antibodies include: Alexa488-donkey anti-chicken, Cy3-donkey anti-rabbit, Cy3-donkey anti-goat, Cy5-donkey anti-rabbit, and Cy5-donkey anti-rat sera, which were diluted 1:800 (all from Jackson Immunoresearch). Results were imaged on a Zeiss Axio Imager M1 upright microscope. Merged images of color overlay were digitally generated after photographing images in separate channels. For the GST pulldown assay, the full length Etv2 gene, its deletional constructs or the GATA domain of Gata2 were subcloned into the pGEX-4T vector. GST fusion proteins were purified using the B-PER protein extraction reagent (Pierce). Ets and Gata factor constructs were utilized for in vitro protein synthesis in the presence of 35S-Methionine. GST-Etv2 or GST-GATA fusion proteins were incubated with 35S-labelled Gata or Ets proteins, respectively, followed by washing with the GST pulldown buffer, analyzed in the SDS-PAGE gel and exposed using the PhosphorImager (GE healthcare). The PhosphorImager was scanned using the Typhoon Imager and processed using ImageQuantTL software (GE healthcare).

ES cell culture, Embryoid body differentiation and FACS analysis

HA-tagged Etv2 overexpression embryonic stem cell (ESC) lines were generated in our laboratory and have been described previously (Koyano-Nakagawa et al., 2012). Murine Gata2 coding region was subcloned into the p2Lox vector and then electroporated into A2Lox Cre mES cells to generate the Gata2 overexpressing ES cell line (Iacovino et al., 2011). The murine Etv2 gene and the murine Gata2 gene were linked through the viral 2A peptide sequence to engineer the Etv2-Gata2 construct, which was utilized to establish the Etv2-Gata2 overexpression ES cell line. ES cell maintenance, embryoid body (EB) differentiation and immunostaining of EBs were performed as described previously (Chan et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2013). FACS analysis was performed on a BD FACSAria (BD Biosciences). The antibodies used for FACS include: c-Kit-APC (eBiosciences 12-5986), CD31-PE (BD Pharmingen 553373), CD41-PE (BD Pharmingen 558040), Flk1-APC (eBiosciences 17-5821) and Tie2-PE (eBiosciences 12-5987).

Animals

Etv2-EYFP transgenic mice were engineered in our laboratory as described previously (Rasmussen et al., 2011). Animals were maintained at the University of Minnesota using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Research Animal Resources at the University of Minnesota.

Statistical analysis

All results were repeated at least three times and presented as means ± S.D. Student t-test (two groups) or Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple-comparison test (more than two groups) were performed to identify the significant differences (p < 0.05) using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

Results

Gata2 is co-expressed with Etv2-EYFP at early stages of endothelial and hematopoietic development

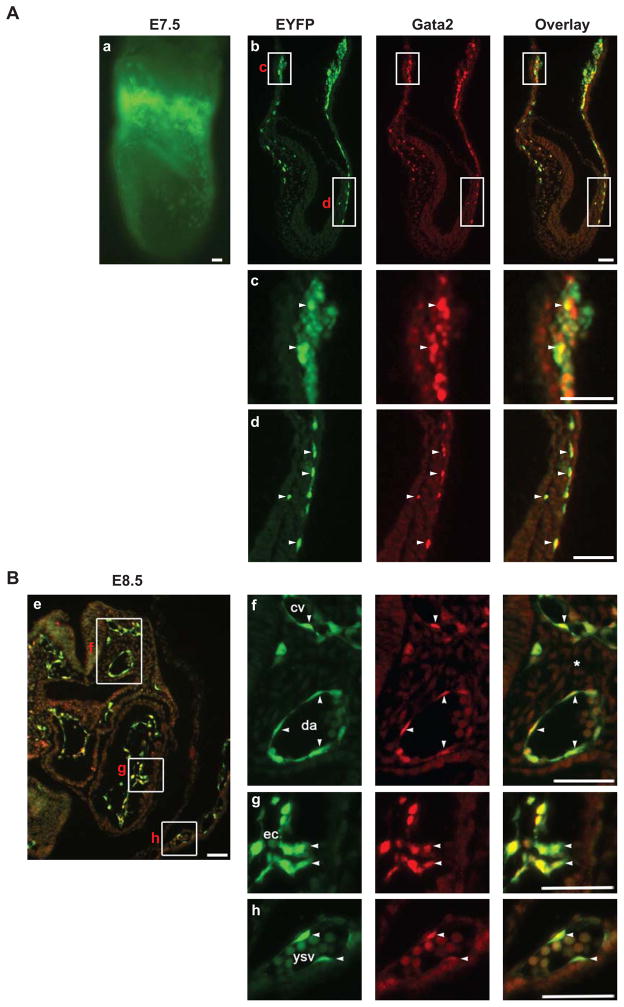

We hypothesized that Etv2 and Gata2 function in parallel or in conjunction with each other to specify the hemato-endothelial lineage. To determine whether Gata2 and Etv2 are co-expressed during embryogenesis, we examined Etv2-EYFP transgenic embryos at E7.5 (headfold stage) and E8.5 (Figure 1). First, we confirmed the specificity of the Gata2 antibody used in these studies (Supplemental Figure S1). Western blot analysis of 293T cell extracts overexpressing Flag-Gata1, Flag-Gata2 or Gata4 proteins with antibodies raised against each protein demonstrated no detectable crossreactivity of the antibodies (Supplemental Figure S1). Epifluorescence analysis of an E7.5 Etv2-EYFP transgenic embryo showed a strong EYFP signal in the extraembryonic blood island area and scattered EYFP positive cells in the embryonic portion as described previously (Figure 1Aa) (Rasmussen et al., 2011). Parasagittal sections demonstrated that EYFP positive cells in the blood island and the lateral plate mesoderm co-expressed Gata2 (Figure 1A, boxed areas c, d). In the yolk sac blood island, Gata2 expression overlapped with EYFP, however the intensity of Gata2 staining varied from cell to cell, likely reflecting the specific stage of erythroid maturation (Figure 1Ac, arrowheads) (Kaneko et al., 2010). In the embryo proper, isolated EYFP positive cells in the lateral plate mesoderm co-labeled with the Gata2 antibody (Figure 1Ad, arrowheads). Further immunohistochemical analysis revealed that these cells also expressed endothelial markers, Flk1 and CD31/Pecam1 (Supplemental Figure S2). At E8.5, extensive overlap of EYFP and Gata2 expression was observed in endothelial cells, including those in the dorsal aortae and cardinal veins (Figure 1Be,f), endocardium (Figure 1Be,g) and yolk sac vessels (Figure 1Be,h).

Fig. 1.

Gata2 and Etv2-EYFP are co-expressed during early embryogenesis. (A and B), headfold stage (E7.5) (A), and E8.5 (B) embryos were analyzed by epifluorescence (a) and immunohistochemistry (b–h). Whole mount expression pattern of EYFP protein at E7.5 is shown in panel a. A parasagittal section (b) of an E7.5 embryo and a transverse section of an E8.5 embryo at the heart level (e) were stained with antibodies to GFP (green) and Gata2 (red). Yellow indicates overlap of green and red channels. The boxed areas indicated in panels b and e are enlarged in panels c, d, f–h, in separate and overlayed channels. Arrowheads mark cells that co-express Gata2 and EYFP. Co-expression of Gata2 and EYFP is observed in blood islands (c) and lateral plate mesoderm (d) at E7.5, and dorsal aorta (f), cardinal veins (f), endocardium (g), and yolk sac endothelium (h) at E8.5. Abbreviations are as follows: cv, cardinal vein: da, doral aorta: ec, endocardium: ysv, yolk sac vessel. Bars: 50 μm.

Since another member of the Gata family proteins, Gata1, is also known to be expressed in the yolk sac blood island (Silver and Palis, 1997; Yokomizo et al., 2007), we examined whether Gata1 is co-expressed with Etv2-EYFP (Supplemental Figure S3). At E7.0 (late streak to early bud stage), we observed cells that express Gata1, Gata2, and EYFP (Supplemental Figure S3B, arrows), as well as those that co-express Gata2 and EYFP, but not Gata1 (Supplemental Figure S3B, arrowheads). At E8.5, only Gata2 was detected in Etv2-EYFPbright endothelial cells (Supplemental Figure S3C, arrowheads) and Etv2-EYFPdim blood cells weakly expressed Gata2 while robustly expressing Gata1 (Supplemental Figure S3C, asterisk). We also examined whether the cardiac Gata family member, Gata4, is co-expressed with Etv2-EYFP in embryonic vessels (Supplemental Figure S4). Cross sectional analysis revealed that Gata1 and Gata4 are not expressed at a detectable level in endothelial cells lining dorsal aortae and cardinal veins (Supplemental Figure S4).

In summary, the analysis of E7.5–8.5 embryos revealed an extensive overlap of EYFP and Gata2 expression in yolk sac blood islands, endothelial cells, and hematopoietic cells, while Gata1 was co-expressed with Etv2-EYFP only in the hematopoietic lineage. In endothelial cells lining major vessels, Gata2 was co-expressed with Etv2-EYFP, but Gata1 and Gata4 were not detected. This expression pattern is consistent with the hypothesis that Etv2 and Gata2 function together in these lineages.

Gata2 physically binds Etv2

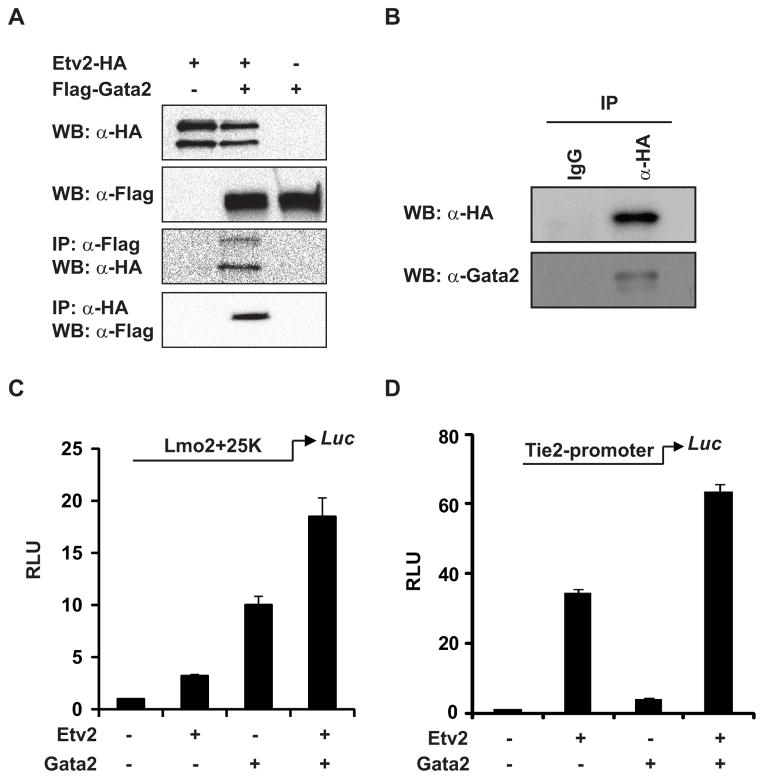

Co-expression of Etv2 and Gata2 during embryogenesis prompted us to hypothesize that Etv2 and Gata2 could function together through a protein-protein interaction in these lineages. We initially examined this hypothesis by overexpressing HA-tagged Etv2 and Flag-tagged Gata2 in C2C12 cells, a non-endothelial, non-hematopoietic cell line. As shown in Figure 2A, both proteins were successfully overexpressed in the C2C12 cells. Etv2 was detected in the Gata2 immunoprecipitation complex (IP: anti-Flag, WB: anti-HA) and Gata2 was also co-immunprecipiated with Etv2 (IP: anti-HA, WB: anti-Flag). Next, we examined the interaction of Etv2 with the endogenous Gata2 protein in differentiated EBs. Since there were no antibodies available to detect the endogenous Etv2, we utilized the HA-tagged Etv2 ES cell line and induced the mRNA encoding the HA-tagged Etv2 protein to a similar level as the endogenous Etv2 as detected by qPCR (data not shown). As shown in Figure 2B, we successfully immunoprecipitated the HA-tagged Etv2 using anti-HA serum and detected the signal by Western blot analysis. We observed that the immunoprecipitation complex contained the endogenous Gata2 protein (WB: anti-Gata2).

Fig. 2.

Gata2 and Etv2 functionally interact with each other. (A) Protein-protein interaction between overexpressed Etv2 and Gata2. HA-tagged Etv2 and Flag-tagged Gata2 are overexpressed in C2C12 cells as shown using Western blot analysis. Etv2 could be co-immunoprecipitated with the Gata2 complex. Gata2 is also detected in the immunoprecipitation complex of Etv2. (B) The ES/EB system, in which HA-tagged Etv2 is engineered to be expressed at a similar level as endogenous Etv2. The endogenous Gata2 can be immunoprecipitated with the HA-tagged Etv2. (C) Transcriptional assays in C2C12 cells demonstrate that Etv2 transactivates the Lmo2 upstream 25K enhancer reporter (Lmo2+25K-Luc) modestly (3-fold), and Gata2 transactivates the reporter approximately 8-fold. Etv2 and Gata2 synergistcally transactivate the reporter up to 18-fold. (D) Tie2 promoter reporter (Tie2 promoter-Luc) can be transactivated by both Etv2 (34-fold) and Gata2 (4-fold). Co-expression of Etv2 and Gata2 results in a synergistic 64-fold transactivation.

We have previously reported that Lmo2 is a direct downstream target gene of Etv2, and Etv2 interacted with multiple enhancers that govern Lmo2 gene expression (Koyano-Nakagawa et al., 2012). One of the enhancers located upstream (25K region) harbors both Ets and Gata motifs. Using transcriptional assays, we examined whether Etv2 and Gata2 cooperatively activated the Lmo2 gene. As shown in Figure 2C, Etv2 and Gata2 transactivated the enhancer-reporter 3-fold and 8-fold above the baseline, respectively. The co-expression of Etv2 and Gata2 resulted in an 18-fold transactivation of the reporter. To further examine the cooperativity of Etv2 and Gata2 coactivation of endothelial genes, we employed the Tie2 promoter. We have previously shown that an endothelial gene, Tie2, is a direct downstream target gene of Etv2 (Ferdous et al., 2009). While we observed synergistic Etv2-Gata2 coactivation of the Lmo2 gene, we observed transactivation of the Tie2 reporter by Etv2 (34-fold) and Gata2 (4-fold), and synergistic activation of the reporter up to 64-fold (Figure 2D). This synergistic transactivation further supports the hypothesis that there is protein-protein interaction between Etv2 and Gata2.

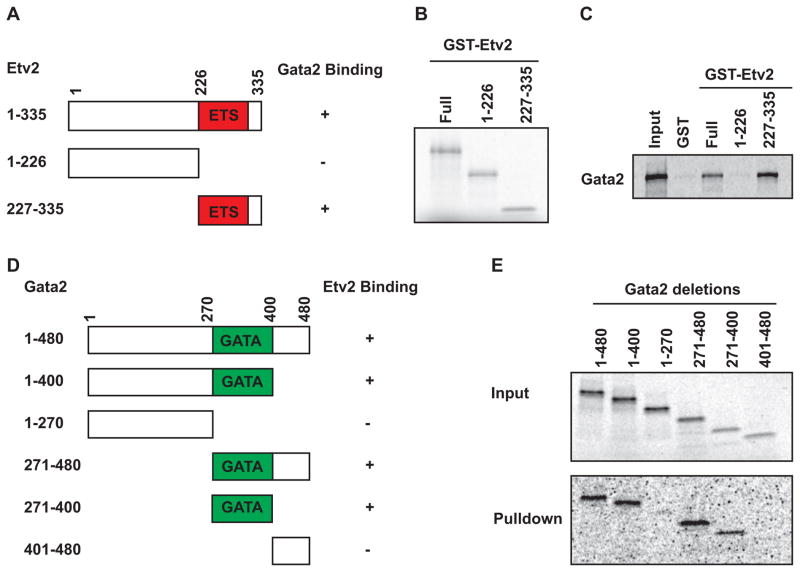

To further characterize the nature of the protein-protein interaction between Etv2 and Gata2, we performed an in vitro GST pulldown assay. Full length or deletional mutants of Etv2 cDNA were fused to the GST tag and expressed in BL21 cells (Figure 3A). These fusion proteins were purified for the GST pulldown assay as shown in Figure 3B. Radiolabeled Gata2 was pulled down with the full length or C-terminal Etv2 (Ets domain) constructs, but not the N-terminal construct (Figure 3C) as summarized in Figure 3A. Using a similar strategy, full length Gata2 or deletional mutants were constructed for in vitro translation and translated in the presence of 35S-Methionine (Figure 3D, E, upper panel). Interestingly, all of the deletional constructs harboring the GATA domain were pulled down by Etv2, but not the constructs lacking the GATA domain (Figure 3E, lower panel), as summarized in Figure 3D. To examine the specificity of the protein-protein interaction between Ets and Gata factors, we performed GST pulldown assays with additional Gata factors and Ets factors. As shown in Supplemental Figure S5A, Gata1 as well as Gata2 were pulled down by Etv2. However, we did not observe a specific interaction between Etv2 and Gata4 (Supplemental Figure S5A). In a reciprocal experiment, the Gata domain of Gata2 interacted with both Etv2 and Erg, while its interaction with Ets2 or Fli1 was much less efficient in our hands (Supplemental Figure S5B).

Fig. 3.

Definition of the protein-protein interaction domain between Etv2 and Gata2. (A) Schematic illustration of Etv2 deletional constructs and their interaction with Gata2. The Ets domain of Etv2, but not the N-terminal domain could bind to Gata2. (B) Coomassie brilliant blue staining of the purified GST-Etv2 deletion fusion proteins. (C) Gata2 protein is synthesized in vitro in the presence of 35S-Methionine. Gata2 could be pulled down by the GST fusion protein harboring the Ets domain, such as the full length and C-terminal proteins, but not the N-terminal protein. (D) Schematic outline of Gata2 deletional constructs and their interaction with Etv2. All of the deletions retaining the GATA domain could interact with Etv2, but not those that lack the GATA domain, such as the N-terminal or C-terminal region. (E) GATA2 deletional proteins are synthesized in vitro and labeled with 35S-Methionine, shown as input (upper lane). These Gata2 deletional proteins were utilized for the pulldown assay with purified GST-Etv2 fusion protein (lower lane).

Regulation of endothelial and hematopoietic lineages by Etv2 and Gata2

Previously, we reported that the overexpression of Etv2 resulted in the induction of the endothelial and hematopoietic lineages (Koyano-Nakagawa et al., 2012). Here, we utilized the ES/EB system to overexpress Etv2 and Gata2 together. Etv2 and Gata2 were linked in tandem through the 2A peptide sequence (Szymczak et al., 2004; Trichas et al., 2008). Upon induction by Dox treatment, the Etv2-Gata2 fusion mRNA were translated into two separate proteins, Etv2 and Gata2, during translation through a ribosomal skip mechanism mediated by the 2A peptide (Figure 4A). Overexpression of Etv2 resulted in upregulation of both the hematopoietic (c-Kit+/CD41+ cells) and the endothelial lineages (Flk1+/CD31+ or Flk1+/Tie2+). We have not observed any significant effect upon overexpression of Gata2 alone. Interestingly, overexpression of Etv2-Gata2 resulted in an enhanced upregulation of endothelial and hematopoietic lineages, compared with the overexpression of Etv2 alone (Figure 4B–4G). These results establish that Gata2 could augment the function of Etv2 in the hematopoietic and endothelial lineages in the ES/EB system.

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of Etv2 and Gata2 during ES/EB differentiation. (A) Schematic illustration of the Etv2-Gata2 construct. Etv2 and Gata2 are linked through the 2A peptide sequence. The fusion construct was translated into two proteins, Etv2 and Gata2, through the ribosome skipping mechanism. (B–D) Co-expression of Etv2 and Gata2 in EBs results in enhanced hematopoietic and endothelial lineage differentiation. The EBs were treated with doxycycline (+ Dox) or left untreated (−Dox) from EB day 3 to day 4 and harvested for FACS analysis on Day 6. The hematopoietic lineage is identified as the c-Kit+/CD41+ cell population (B), and the endothelial lineage is represented as the Flk1+/CD31+ (C) and the Flk1+/Tie2+ cell population (D). (E–G) Quantitative summary of the lineage analysis in B–D, respectively.

Etv2 and Gata2 synergistically transactivate Spi1 gene expression

To explore the underlying mechanism of the synergistic regulation of endothelial and hematopoietic lineages by Etv2 and Gata2, we examined the gene expression profile of ES cells overexpressing Etv2, Gata2 or both using RNAseq analysis. We observed upregulation of both endothelial and hematopoietic genes upon Etv2 or Etv2-Gata2 overexpression (Supplemental Figure S6). To verify the RNAseq data, we performed qPCR analysis for selected endothelial and hematopoietic genes. We observed that the endothelial lineage markers, Cdh5, Flk1/Vegfr2/Kdr, CD31/Pecam1 and Tie2/Tek, were upregulated following Etv2 overexpression and CD31 and Tie2 were upregulated upon Gata2 overexpression. The induction of Tie2 was enhanced following Etv2-Gata2 overexpression compared with that of Etv2 or Gata2 overexpression alone (Figure 5A). Moreover, we further observed that overexpression of Etv2 resulted in upregulation of well-known hematopoietic genes including: CD34, Eng, Fli1, Lmo2, Spi1 and Tal1. Gata2 overexpression also increased hematopoietic genes including: CD41, Fli1, Runx1, Spi1 and Tal1 (Figure 5A). Overexpression of Etv2-Gata2 resulted in the enhanced upregulation of Lmo2, Spi1 and Tal1 compared to Etv2 or Gata2 overexpression alone (Figure 5A).

Fig. 5.

Spi1 is a common target gene of Etv2 and Gata2. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression upon induction of Etv2, Gata2 or Etv2-Gata2 in ES cells. (B) ChIP assay of the Spi1 promoter using anti-HA and anit-Gata2 sera. Primers detecting the Gapdh promoter was used as a control of nonspecific binding. (C–D) EMSA assay of the Spi1 promoter with Etv2 (C) or Gata2 (D), respectively. The specific binding and supershift signals are marked at the left. wt, wildtype competitor, mut, mutated competitor. The ctrl (control) antibody is a rabbit IgG. The ctrl (control) in the protein lysate is the translation lysate with the empty vector plasmid. (E) Schematic illustration of Spi1 promoter constructs. The 0.2 kb proximal promoter of Spi1 harbors 4 Ets motifs and 2 Gata motifs (Ets-m, all of the four Ets motifs mutated; Gata-m, both Gata motifs mutated). (F) Transcriptional assays of the Spi1 promoter-reporter by Etv2 and Gata2. Etv2 can transactivate the Spi1 promoter reporter up to 5-fold. This transactivation is attenuated to a basal level upon mutation of the Ets motifs (Ets-m). Gata2 transactives the Spi1 promoter reporter to approximately 5-fold. Gata2 transactivation is completely abolished when both Gata motifs are mutated (Gata-m). Co-expression of Etv2 and Gata2 synergistically transactivates the reporter up to 20-fold. Mutation of the Ets motifs or the Gata motifs resulted in approximately 6-fold reduction of the synergistic transactivation.

We have previously reported that Spi1 was downregulated in the yolk sac of Etv2 mutant mice and upregulated upon Etv2 overexpression in the ES/EB system (Koyano-Nakagawa et al., 2012). To further examine whether Spi1 is a direct target gene of Etv2 and Gata2, we utilized ChIP and EMSA techniques. As shown in Figure 5B, both Etv2 and Gata2 was specifically bound to the Spi1 promoter in vivo using the ChIP assay. The interaction between the Spi1 promoter and Etv2 or Gata2 was also confirmed in vitro using EMSA (Figure 5C and 5D). To examine the transcriptional regulation of Spi1 by Etv2 and Gata2, we subcloned the Spi1 0.2 kb proximal promoter, which harbors 4 Ets motifs and 2 Gata motifs, into the luciferase reporter vector (Figure 5E). As shown in Figure 5F, both Etv2 and Gata2 transactivated the wildtype reporter in a dose-dependent fashion. The transactivation by Etv2 or Gata2 was reduced in reporters with the Ets site mutatated (Ets-m) or the Gata binding site mutated (Gata-m), respectively. Co-expression of Etv2 and Gata2 transactivated the wildtype reporter up to 20-fold, which was significantly higher than that Etv2 or Gata2 alone. These data further support the notion that Etv2 and Gata2 cooperate to synergistically transactivate gene expression. To examine the effect of the protein-DNA interaction on the synergistic transactivation, the Ets motifs or Gata motifs were mutated. As shown in Figure 5F, this synergistic transactivation was perturbed in both the Ets-m and Gata-m reporters.

Discussion

The functional role of Etv2/Er71/Etsrp in the specification of the mesodermal lineage has been well characterized (Kataoka et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2008; Neuhaus et al., 2010; Rasmussen et al., 2011; Sumanas and Lin, 2006). The endothelial and hematopoietic lineages were completely absent in the Etv2 mutant embryos (Ferdous et al., 2009; Koyano-Nakagawa et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2008). We have also deciphered the signaling cascade between Flk1, p38, Creb1, Etv2, Tie2, and Lmo2 during embryogenesis (Koyano-Nakagawa et al., 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2012). In the present report, we identified Gata2 as a cofactor of Etv2 using an array of biochemical techniques. We have also demonstrated that Gata2 augmented the functional role of Etv2 in the development of endothelial and hematopoietic lineages. Our studies have further revealed that Spi1 was a common downstream target gene of Etv2 and Gata2 during embryogenesis.

Identification of Gata2 as an Etv2-interacting transcription factor

Recent studies have revealed functional roles for Etv2 in mesodermal lineage specification, although the underlying molecular mechanisms were incompletely understood. The Foxc2-Etv2 protein complex regulates transcription of endothelial genes, and the Fox:Ets consensus motif is found in approximately 33% of the endothelial genes (De Val et al., 2008). Etv2 is also essential for the development of the hematopoietic lineage although the Fox:Ets motif is only mildly enriched in the hematopoietic genes. Therefore, it is likely that Etv2 may interact with additional factors to regulate the endothelial and/or hematopoietic lineages. Previous studies have reported a number of Gata2-interacting factors including AP1 (Kawana et al., 1995; Yamashita et al., 2001) and Hdac3 (Ozawa et al., 2001). Gata factors have also been demonstrated to cooperatively bind DNA and regulate transcription with other transcription factors, such as Tal1, Lmo2 and Ets proteins (Landry et al., 2005; Pimanda et al., 2008; Pimanda et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2010). These studies revealed that Gata2 transactivates or represses its target genes depending on its interacting protein(s).

In the present study, we have identified Gata2 as a transcriptional regulatory cofactor of Etv2. The domain mapping studies revealed that the Ets domain of Etv2 interacts with the Gata domain of Gata2. The GST pull down assay revealed that Gata1 binds to the Ets domain of Etv2 as well as Gata2. Similarly, Erg, an Ets family member, binds to the Gata domain of Gata2 as efficiently as Etv2. These in vitro protein-protein interactions may reflect the homology of the Ets or Gata domains in the Ets or Gata factors, respectively. However, in vivo studies demonstrate that distinct expression and function of Ets and Gata family members (De Val and Black, 2009; Kaneko et al., 2010; Remy and Baltzinger, 2000). Thus, we propose that that the specificity of their interaction is conferred by the spatial and temporal expression pattern of the specific factor. Our expression analysis demonstrates that among the Gata factors examined, Gata2 expression best correlates with that of Etv2, and makes it a likely interacting Gata factor during endothelial development. We noted that Gata1 is co-expressed with Etv2 and Gata2 in the developing yolk sac blood islands at E7.0, but segregates to a distinct population from Gata2 by E8.5. We reason the co-expression is due to the transcriptional activation of Gata1 gene expression by Gata2.

Transcriptional assays with the Spi1 promoter-reporter demonstrated that Gata2 cooperates with Etv2 and augments the transcriptional activity of Etv2. This synergy was attenuated when the Ets and Gata motifs in the reporter were mutated. Thus, the synergistic transactivation between Etv2 and Gata2 was DNA binding dependent. However, the minimal promoter of Spi1, containing the 4 Ets motifs and 2 Gata motifs, was not sufficient to direct the reporter gene expression to the hematopoietic lineage (Hoogenkamp et al., 2007; Li et al., 2001). Therefore, these Ets and Gata motifs may not be sufficient to drive lineage specific gene expression in contrast to the Fox:Ets composite motifs. One plausible hypothesis is that additional motifs are required to increase the specificity for the lineage-restricted expression of the Ets-Gata motifs. Another possibility is that the specificity of transcriptional cooperation is regulated by tissue specific expression of the factors as discussed above. Further analysis of the transcriptional mechanisms will distinguish between these possibilities.

The functional role of Etv2 is influenced by its association with Gata2

Genetic studies have revealed the essential role of Gata2 in the development of the hematopoietic lineage. Further studies have shown that Gata2 promotes the multiple lineage specification during mesodermal differentiation, including hematopoietic, endothelial, skeletal muscle, and cardiac lineages (Lugus et al., 2007). Loss of Etv2 leads to the absence of the development of endothelial and hematopoietic lineages, and overexpression of Etv2 results in the enhanced development of endothelial and hematopoietic lineages (Ferdous et al., 2009; Koyano-Nakagawa et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2011). Co-expression of Etv2 and Foxc2 induces the endothelial lineage, and upregulates a number of endothelial genes. The effect of the association between Etv2 and Foxc2 seems minimal with respect to the hematopoietic lineage (De Val et al., 2008). In our present studies, functional assays using the ES/EB system revealed that the co-expression of Etv2 and Gata2 resulted in the enhanced differentiation of both endothelial and hematopoietic lineages. Overexpression studies of Etv2 and Gata2 in Xenopus laevis embryos produced similar results (our unpublished observation). Thus, our data indicate that Gata2 plays a role as a general coactivator of Etv2 in the mesodermal lineage development.

Our results using the ES/EB system differs from the study by Lugus et al., where they observed that Gata2 is sufficient to specify hemangioblasts and promote the endothelial lineage from the Bry+ mesoderm (Lugus et al., 2007). We reason that the discrepancy between our studies and that of Lugus et al. is due to the differences in the EB differentiation conditions including the time of induction and the media components. Lugus et al. treated EBs with Dox for 4 days, from day 2 to day 6 (including the stages of hemangioblast specification), whereas we stimulated the EBs transiently, from day 3 to day 4 (a time period following specification of the hemangioblast). One possibility is that the early stimulation undertaken by Lugus et al. emphasized the hemangioblast specification role of Gata2, whereas our induction scheme mimicked the functional role of Gata2 after hematopoietic and endothelial lineage specification. Moreover, media components utilized in these respective studies were also different as Lugus et al. used serum free (i.e. serum-replacement) medium, whereas we used a medium containing serum. Although these different observations raise an interesting possibility that Gata2 may play different roles in multiple stages of hemato-endothelial development (specification of hemangioblast and differentiation of each lineage), the results of these overexpression studies should be interpreted with caution as we have shown that the Gata domain of Gata2 also interacts with additional Ets factors. Further studies including detailed expression analysis in hemangioblasts in vivo will be required to provide further definition.

Spi1 is cooperatively regulated by Etv2 and Gata2

Spi1 is a key Ets factor in myeloid lineage specification. Loss- and gain-of-function studies in zebrafish (Wong et al., 2009) and mouse (Koyano-Nakagawa et al., 2012) suggested that Spi1 is regulated by Etv2. In the present study, we provide evidence that Spi1 is a downstream target gene of Etv2 through an array of techniques, including qPCR, ChIP, EMSA, and transcriptional assays. These data suggest that the Etv2/Etsrp-Spi1 cascade is conserved among different species, underscoring the critical role of Etv2 in the development of the myeloid lineage. However, the mechanism of regulation may be context dependent. Previous studies have revealed that Gata2 represses the transcriptional activity of Spi1 through the inhibition of the interaction between Spi1 and its cofactor, c-Jun (Zhang et al., 1999). Gata2 also represses Spi1 gene expression through the Gata motif in the proximal promoter (Chou et al., 2009). In contrast, our studies have demonstrated that Gata2 transactivates Spi1 gene expression during early embryogenesis and that this transactivation is mediated through the Gata motifs in the proximal Spi1 promoter. Taken together, evidence suggests that regulation of Spi1 gene expression by Gata2 changes according to the developmental stages of the mesodermal lineage. In the early embryonic stages, Gata2 and Ets2 synergistically transactivate Spi1 gene expression. During the later stages, such as myeloid differentiation, Spi1 could autoactivate its expression through interaction with c-Jun. At this stage, overexpression of Gata2 could result in the repression of the activity of Spi1 protein and its transcriptional gene expression. In the present study, we utilized the whole EBs in the RNAseq studies, and we recognize the possibility that some common downstream target genes may have not been detected using this strategy due to the heterogeneity of the EB cells. Additional common target genes of Etv2 and Gata2 may be identified using RNAseq of FACS sorted cell populations from EBs, which will be a future initiative.

In summary, our studies have demonstrated the cooperative interaction between Etv2 and Gata2 and this interaction could enhance the activity of Etv2 in the regulation of endothelial and hematopoietic cellular development as well as in the transcriptional regulation of its downstream target genes. Further studies identifying additional Etv2 cofactors and its downstream targets will enhance our understanding of the underlying mechanism of Etv2 function during mesodermal lineage specification.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Etv2 and Gata2 are co-expressed during embryogenesis.

Etv2 interacts with Gata2 through the conserved Ets and Gata domains, respectively.

Overexpression of Etv2 and Gata2 promotes the endothelial and hematopoietic lineages.

Spi13 is a common target gene of Etv23 and Gata2.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of Michael J Przybilla and Rachel Gohla for the animal care, Yi Ren for FACS analysis, and Tongbin Li, Scott Swanson and Ron Stewart for assistance with the RNAseq analysis. This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (U01 HL100407 and R01 HL085729) and American Heart Association (Jon Holden DeHaan Foundation, 0970499N).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bories JC, Willerford DM, Grevin D, Davidson L, Camus A, Martin P, Stehelin D, Alt FW. Increased T-cell apoptosis and terminal B-cell differentiation induced by inactivation of the Ets-1 proto-oncogene. Nature. 1995;377:635–638. doi: 10.1038/377635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SS, Shi X, Toyama A, Arpke RW, Dandapat A, Iacovino M, Kang J, Le G, Hagen HR, Garry DJ, Kyba M. Mesp1 patterns mesoderm into cardiac, hematopoietic, or skeletal myogenic progenitors in a context-dependent manner. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:587–601. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MJ, Yokomizo T, Zeigler BM, Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature. 2009;457:887–891. doi: 10.1038/nature07619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou ST, Khandros E, Bailey LC, Nichols KE, Vakoc CR, Yao Y, Huang Z, Crispino JD, Hardison RC, Blobel GA, Weiss MJ. Graded repression of PU.1/Sfpi1 gene transcription by GATA factors regulates hematopoietic cell fate. Blood. 2009;114:983–994. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-207944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Val S, Black BL. Transcriptional control of endothelial cell development. Dev Cell. 2009;16:180–195. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Val S, Chi NC, Meadows SM, Minovitsky S, Anderson JP, Harris IS, Ehlers ML, Agarwal P, Visel A, Xu SM, Pennacchio LA, Dubchak I, Krieg PA, Stainier DY, Black BL. Combinatorial regulation of endothelial gene expression by ets and forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2008;135:1053–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman DM, Wilson DB, Bruns GA, Orkin SH. Human transcription factor GATA-2. Evidence for regulation of preproendothelin-1 gene expression in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1279–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilken HM, Nishikawa S, Schroeder T. Continuous single-cell imaging of blood generation from haemogenic endothelium. Nature. 2009;457:896–900. doi: 10.1038/nature07760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdous A, Caprioli A, Iacovino M, Martin CM, Morris J, Richardson JA, Latif S, Hammer RE, Harvey RP, Olson EN, Kyba M, Garry DJ. Nkx2-5 transactivates the Ets-related protein 71 gene and specifies an endothelial/endocardial fate in the developing embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:814–819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807583106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangenahalli GU, Gupta P, Saluja D, Verma YK, Kishore V, Chandra R, Sharma RK, Ravindranath T. Stem cell fate specification: role of master regulatory switch transcription factor PU.1 in differential hematopoiesis. Stem Cells Dev. 2005;14:140–152. doi: 10.1089/scd.2005.14.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German Z, Chambliss KL, Pace MC, Arnet UA, Lowenstein CJ, Shaul PW. Molecular basis of cell-specific endothelial nitric-oxide synthase expression in airway epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8183–8189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottgens B, Nastos A, Kinston S, Piltz S, Delabesse EC, Stanley M, Sanchez MJ, Ciau-Uitz A, Patient R, Green AR. Establishing the transcriptional programme for blood: the SCL stem cell enhancer is regulated by a multiprotein complex containing Ets and GATA factors. EMBO J. 2002;21:3039–3050. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumina RJ, Kirschbaum NE, Piotrowski K, Newman PJ. Characterization of the human platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 promoter: identification of a GATA-2 binding element required for optimal transcriptional activity. Blood. 1997;89:1260–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi KK. Hemogenic endothelium during development and beyond. Blood. 2012;119:4823–4827. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-353466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock H, Meade E, Medeiros S, Schindler JW, Valk PJ, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH. Tel/Etv6 is an essential and selective regulator of adult hematopoietic stem cell survival. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2336–2341. doi: 10.1101/gad.1239604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenhorst PC, McIntosh LP, Graves BJ. Genomic and biochemical insights into the specificity of ETS transcription factors. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:437–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.79.081507.103945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenkamp M, Krysinska H, Ingram R, Huang G, Barlow R, Clarke D, Ebralidze A, Zhang P, Tagoh H, Cockerill PN, Tenen DG, Bonifer C. The Pu.1 locus is differentially regulated at the level of chromatin structure and noncoding transcription by alternate mechanisms at distinct developmental stages of hematopoiesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7425–7438. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00905-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovino M, Bosnakovski D, Fey H, Rux D, Bajwa G, Mahen E, Mitanoska A, Xu Z, Kyba M. Inducible cassette exchange: a rapid and efficient system enabling conditional gene expression in embryonic stem and primary cells. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1580–1588. doi: 10.1002/stem.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko H, Shimizu R, Yamamoto M. GATA factor switching during erythroid differentiation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2010;17:163–168. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32833800b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki Y, Kohro T, Jiang S, Tsutsumi S, Mimura I, Suehiro J, Wada Y, Ohta Y, Ihara S, Iwanari H, Naito M, Hamakubo T, Aburatani H, Kodama T, Minami T. Epigenetically coordinated GATA2 binding is necessary for endothelium-specific endomucin expression. EMBO J. 2011;30:2582–2595. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka H, Hayashi M, Kobayashi K, Ding G, Tanaka Y, Nishikawa S. Region-specific Etv2 ablation revealed the critical origin of hemogenic capacity from Hox6-positive caudal-lateral primitive mesoderm. Exp Hematol. 2013;41:567–581. e569. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka H, Hayashi M, Nakagawa R, Tanaka Y, Izumi N, Nishikawa S, Jakt ML, Tarui H. Etv2/ER71 induces vascular mesoderm from Flk1+PDGFRalpha+ primitive mesoderm. Blood. 2011;118:6975–6986. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawana M, Lee ME, Quertermous EE, Quertermous T. Cooperative interaction of GATA-2 and AP1 regulates transcription of the endothelin-1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4225–4231. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller G, Lacaud G, Robertson S. Development of the hematopoietic system in the mouse. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:777–787. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko LJ, Engel JD. DNA-binding specificities of the GATA transcription factor family. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4011–4022. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Ding G, Nishikawa SI, Kataoka H. Role of Etv2-positive cells in the remodeling morphogenesis during vascular development. Genes Cells. 2013 doi: 10.1111/gtc.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyano-Nakagawa N, Kweon J, Iacovino M, Shi X, Rasmussen TL, Borges L, Zirbes KM, Li T, Perlingeiro RC, Kyba M, Garry DJ. Etv2 is expressed in the yolk sac hematopoietic and endothelial progenitors and regulates Lmo2 gene expression. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1611–1623. doi: 10.1002/stem.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammerts van Bueren K, Black BL. Regulation of endothelial and hematopoietic development by the ETS transcription factor Etv2. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19:199–205. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283523e07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancrin C, Sroczynska P, Stephenson C, Allen T, Kouskoff V, Lacaud G. The haemangioblast generates haematopoietic cells through a haemogenic endothelium stage. Nature. 2009;457:892–895. doi: 10.1038/nature07679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry JR, Kinston S, Knezevic K, Donaldson IJ, Green AR, Gottgens B. Fli1, Elf1, and Ets1 regulate the proximal promoter of the LMO2 gene in endothelial cells. Blood. 2005;106:2680–2687. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Kim T, Lim DS. The Er71 is an important regulator of hematopoietic stem cells in adult mice. Stem Cells. 2011;29:539–548. doi: 10.1002/stem.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Park C, Lee H, Lugus JJ, Kim SH, Arentson E, Chung YS, Gomez G, Kyba M, Lin S, Janknecht R, Lim DS, Choi K. ER71 acts downstream of BMP, Notch, and Wnt signaling in blood and vessel progenitor specification. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:497–507. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng N, Dawson JA, Thomson JA, Ruotti V, Rissman AI, Smits BM, Haag JD, Gould MN, Stewart RM, Kendziorski C. EBSeq: an empirical Bayes hierarchical model for inference in RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1035–1043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Okuno Y, Zhang P, Radomska HS, Chen H, Iwasaki H, Akashi K, Klemsz MJ, McKercher SR, Maki RA, Tenen DG. Regulation of the PU.1 gene by distal elements. Blood. 2001;98:2958–2965. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughran SJ, Kruse EA, Hacking DF, de Graaf CA, Hyland CD, Willson TA, Henley KJ, Ellis S, Voss AK, Metcalf D, Hilton DJ, Alexander WS, Kile BT. The transcription factor Erg is essential for definitive hematopoiesis and the function of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:810–819. doi: 10.1038/ni.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugus JJ, Chung YS, Mills JC, Kim SI, Grass J, Kyba M, Doherty JM, Bresnick EH, Choi K. GATA2 functions at multiple steps in hemangioblast development and differentiation. Development. 2007;134:393–405. doi: 10.1242/dev.02731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeno M, Mead PE, Kelley C, Xu RH, Kung HF, Suzuki A, Ueno N, Zon LI. The role of BMP-4 and GATA-2 in the induction and differentiation of hematopoietic mesoderm in Xenopus laevis. Blood. 1996;88:1965–1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows SM, Myers CT, Krieg PA. Regulation of endothelial cell development by ETS transcription factors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merika M, Orkin SH. DNA-binding specificity of GATA family transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:3999–4010. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD. The zinc finger-containing transcription factors GATA-4, -5, and -6. Ubiquitously expressed regulators of tissue-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38949–38952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrisey EE, Ip HS, Lu MM, Parmacek MS. GATA-6: a zinc finger transcription factor that is expressed in multiple cell lineages derived from lateral mesoderm. Dev Biol. 1996;177:309–322. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthusamy N, Barton K, Leiden JM. Defective activation and survival of T cells lacking the Ets-1 transcription factor. Nature. 1995;377:639–642. doi: 10.1038/377639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus H, Muller F, Hollemann T. Xenopus er71 is involved in vascular development. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:3436–3445. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa Y, Towatari M, Tsuzuki S, Hayakawa F, Maeda T, Miyata Y, Tanimoto M, Saito H. Histone deacetylase 3 associates with and represses the transcription factor GATA-2. Blood. 2001;98:2116–2123. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterkin T, Gibson A, Loose M, Patient R. The roles of GATA-4, -5 and -6 in vertebrate heart development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimanda JE, Chan WY, Wilson NK, Smith AM, Kinston S, Knezevic K, Janes ME, Landry JR, Kolb-Kokocinski A, Frampton J, Tannahill D, Ottersbach K, Follows GA, Lacaud G, Kouskoff V, Gottgens B. Endoglin expression in blood and endothelium is differentially regulated by modular assembly of the Ets/Gata hemangioblast code. Blood. 2008;112:4512–4522. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-157560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimanda JE, Ottersbach K, Knezevic K, Kinston S, Chan WY, Wilson NK, Landry JR, Wood AD, Kolb-Kokocinski A, Green AR, Tannahill D, Lacaud G, Kouskoff V, Gottgens B. Gata2, Fli1, and Scl form a recursively wired gene-regulatory circuit during early hematopoietic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17692–17697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707045104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen TL, Kweon J, Diekmann MA, Belema-Bedada F, Song Q, Bowlin K, Shi X, Ferdous A, Li T, Kyba M, Metzger JM, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Garry DJ. ER71 directs mesodermal fate decisions during embryogenesis. Development. 2011;138:4801–4812. doi: 10.1242/dev.070912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen TL, Martin CM, Walter CA, Shi X, Perlingeiro R, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Garry DJ. Etv2 rescues Flk1 mutant embryoid bodies. Genesis. 2013;51:471–480. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen TL, Shi X, Wallis A, Kweon J, Zirbes KM, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Garry DJ. VEGF/Flk1 Signaling Cascade Transactivates Etv2 Gene Expression. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remy P, Baltzinger M. The Ets-transcription factor family in embryonic development: lessons from the amphibian and bird. Oncogene. 2000;19:6417–6431. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachterle W, Rojas A, Xu SM, Black BL. ETS-dependent regulation of a distal Gata4 cardiac enhancer. Dev Biol. 2012;361:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott EW, Simon MC, Anastasi J, Singh H. Requirement of transcription factor PU.1 in the development of multiple hematopoietic lineages. Science. 1994;265:1573–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.8079170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Garry DJ. Myogenic regulatory factors transactivate the Tceal7 gene and modulate muscle differentiation. Biochem J. 2010;428:213–221. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Seldin DC, Garry DJ. Foxk1 recruits the Sds3 complex and represses gene expression in myogenic progenitors. Biochem J. 2012;446:349–357. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu R, Yamamoto M. Gene expression regulation and domain function of hematopoietic GATA factors. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver L, Palis J. Initiation of murine embryonic erythropoiesis: a spatial analysis. Blood. 1997;89:1154–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyropoulos DD, Pharr PN, Lavenburg KR, Jackers P, Papas TS, Ogawa M, Watson DK. Hemorrhage, impaired hematopoiesis, and lethality in mouse embryos carrying a targeted disruption of the Fli1 transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5643–5652. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5643-5652.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumanas S, Gomez G, Zhao Y, Park C, Choi K, Lin S. Interplay among Etsrp/ER71, Scl, and Alk8 signaling controls endothelial and myeloid cell formation. Blood. 2008;111:4500–4510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumanas S, Lin S. Ets1-related protein is a key regulator of vasculogenesis in zebrafish. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Shimizu R, Yamamoto M. Transcriptional regulation by GATA1 and GATA2 during erythropoiesis. Int J Hematol. 2011;93:150–155. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Dilioglou S, Vanin EF, Vignali DA. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijssen MR, Cvejic A, Joshi A, Hannah RL, Ferreira R, Forrai A, Bellissimo DC, Oram SH, Smethurst PA, Wilson NK, Wang X, Ottersbach K, Stemple DL, Green AR, Ouwehand WH, Gottgens B. Genome-wide analysis of simultaneous GATA1/2, RUNX1, FLI1, and SCL binding in megakaryocytes identifies hematopoietic regulators. Dev Cell. 2011;20:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trichas G, Begbie J, Srinivas S. Use of the viral 2A peptide for bicistronic expression in transgenic mice. BMC Biol. 2008;6:40. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-6-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai FY, Keller G, Kuo FC, Weiss M, Chen J, Rosenblatt M, Alt FW, Orkin SH. An early haematopoietic defect in mice lacking the transcription factor GATA-2. Nature. 1994;371:221–226. doi: 10.1038/371221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente C, Conchillo A, Garcia-Sanchez MA, Odero MD. The role of the GATA2 transcription factor in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;82:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LC, Kuo F, Fujiwara Y, Gilliland DG, Golub TR, Orkin SH. Yolk sac angiogenic defect and intra-embryonic apoptosis in mice lacking the Ets-related factor TEL. EMBO J. 1997;16:4374–4383. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wareing S, Mazan A, Pearson S, Gottgens B, Lacaud G, Kouskoff V. The Flk1-Cre-mediated deletion of ETV2 defines its narrow temporal requirement during embryonic hematopoietic development. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1521–1531. doi: 10.1002/stem.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G, Srinivasan R, Cantemir-Stone CZ, Sharma SM, Santhanam R, Weinstein M, Muthusamy N, Man AK, Oshima RG, Leone G, Ostrowski MC. Ets1 and Ets2 are required for endothelial cell survival during embryonic angiogenesis. Blood. 2009;114:1123–1130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MJ, Orkin SH. GATA transcription factors: key regulators of hematopoiesis. Exp Hematol. 1995;23:99–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson NK, Timms RT, Kinston SJ, Cheng YH, Oram SH, Landry JR, Mullender J, Ottersbach K, Gottgens B. Gfi1 expression is controlled by five distinct regulatory regions spread over 100 kilobases, with Scl/Tal1, Gata2, PU.1, Erg, Meis1, and Runx1 acting as upstream regulators in early hematopoietic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3853–3863. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00032-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong KS, Proulx K, Rost MS, Sumanas S. Identification of vasculature-specific genes by microarray analysis of Etsrp/Etv2 overexpressing zebrafish embryos. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1836–1850. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K, Discher DJ, Hu J, Bishopric NH, Webster KA. Molecular regulation of the endothelin-1 gene by hypoxia. Contributions of hypoxia-inducible factor-1, activator protein-1, GATA-2, AND p300/CBP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12645–12653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokomizo T, Takahashi S, Mochizuki N, Kuroha T, Ema M, Wakamatsu A, Shimizu R, Ohneda O, Osato M, Okada H, Komori T, Ogawa M, Nishikawa S, Ito Y, Yamamoto M. Characterization of GATA-1(+) hemangioblastic cells in the mouse embryo. EMBO J. 2007;26:184–196. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zape JP, Zovein AC. Hemogenic endothelium: origins, regulation, and implications for vascular biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:1036–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Behre G, Pan J, Iwama A, Wara-Aswapati N, Radomska HS, Auron PE, Tenen DG, Sun Z. Negative cross-talk between hematopoietic regulators: GATA proteins repress PU.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:8705–8710. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.